↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

High-dimensional black-box function optimization is challenging. Local Bayesian optimization methods, approximating gradients, show promise but can be inefficient. Existing methods like GIBO utilize posterior gradient distributions, potentially ignoring valuable Gaussian process information.

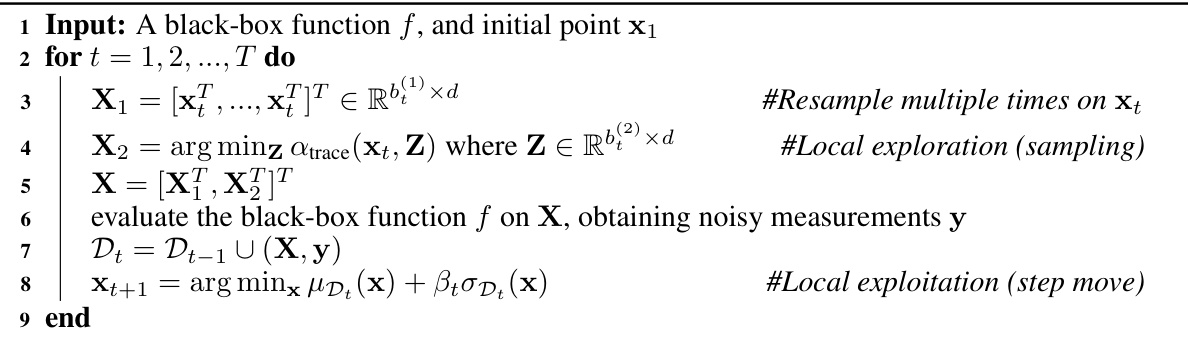

The paper proposes MinUCB and LA-MinUCB, replacing gradient descent with UCB minimization. MinUCB shows similar convergence to GIBO but with a tighter bound. LA-MinUCB incorporates a look-ahead strategy for further efficiency. Experiments demonstrate their effectiveness on various functions, surpassing existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it offers a novel approach to local Bayesian optimization by minimizing the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), showing improved efficiency compared to traditional gradient-based methods. It also provides a strong theoretical foundation and demonstrates efficacy across various synthetic and real-world functions, opening up new avenues for algorithm design in Bayesian optimization.

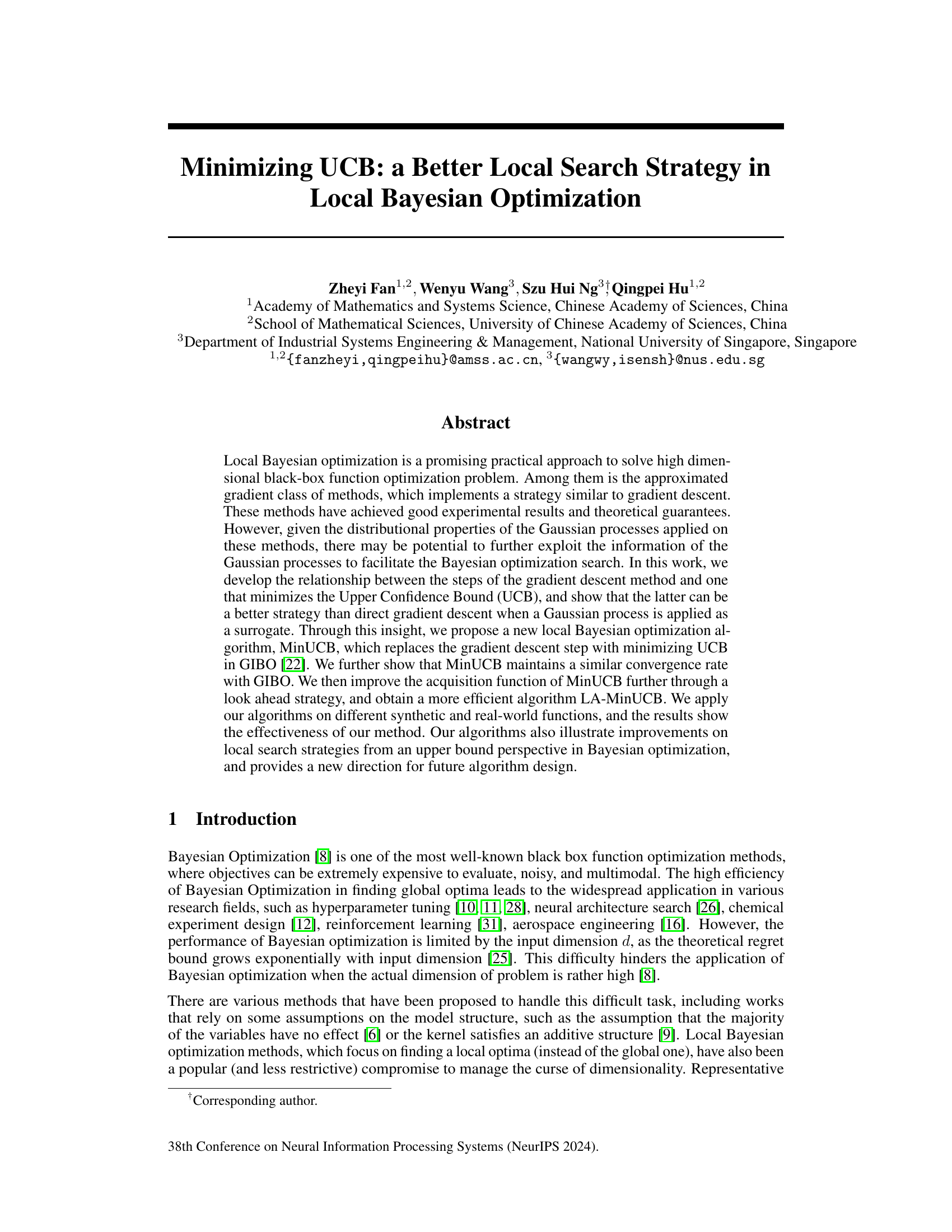

Visual Insights#

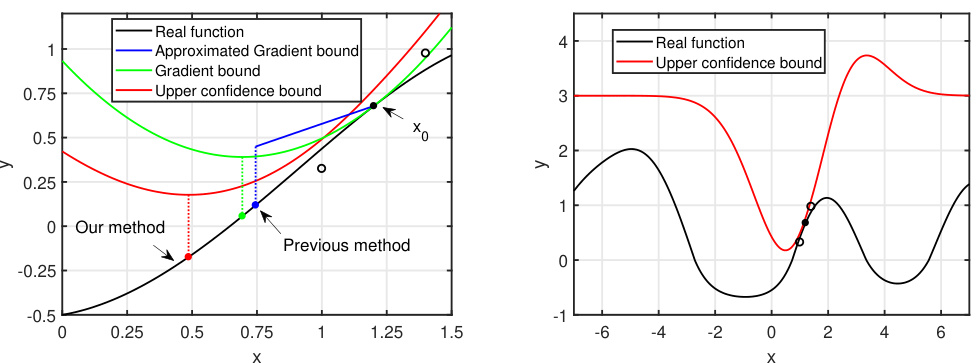

This figure shows a comparison of different acquisition functions for selecting the next point in a Bayesian optimization algorithm. The left panel shows a 1D example where the UCB (Upper Confidence Bound) is much tighter than gradient-based bounds, indicating that minimizing UCB can lead to a better point than using gradient descent. The right panel displays a UCB surface, which shows that UCB is small near the sampled points and increases as the distance from the sampled points increases, thus showing its local nature.

In-depth insights#

MinUCB: Core Idea#

The core idea behind MinUCB is to improve local Bayesian optimization by replacing the gradient descent step in existing algorithms like GIBO with a step that minimizes the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB). This is motivated by the observation that, when using a Gaussian process surrogate, minimizing UCB can often yield points with higher reward than direct gradient descent. The intuition is that UCB, by incorporating both the mean prediction and uncertainty, provides a tighter bound than the quadratic approximations employed in gradient-based methods. This tighter bound allows MinUCB to exploit more information from the Gaussian process, potentially leading to a more efficient and effective search within the local region. MinUCB maintains a similar convergence rate to GIBO, demonstrating that the improved search strategy does not compromise theoretical guarantees while offering practical advantages. The key advantage lies in its ability to leverage the full information of the Gaussian process, unlike gradient-based methods that largely focus on the gradient estimate. This makes MinUCB a potentially more robust and efficient alternative for high-dimensional black-box optimization.

LA-MinUCB: Lookahead#

The proposed LA-MinUCB algorithm integrates a lookahead strategy to enhance the efficiency of local Bayesian optimization. Unlike MinUCB, which focuses solely on minimizing the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) at the current point, LA-MinUCB incorporates a predictive element. It considers the expected minimum UCB value across future potential sample points, effectively guiding the search towards areas promising greater improvements. This lookahead approach, while computationally more intensive, is designed to circumvent potential inefficiencies arising from localized exploration by providing a more informed, forward-looking strategy. The algorithm’s effectiveness is demonstrated through experimental results, showcasing superior performance compared to existing methods in various settings. By incorporating a lookahead mechanism, LA-MinUCB significantly improves the efficiency and accuracy of local exploitation steps, demonstrating its potential as a more robust and advanced technique for local Bayesian optimization problems.

Convergence Analysis#

A rigorous convergence analysis is crucial for establishing the reliability and effectiveness of any optimization algorithm. In the context of the provided research, this analysis likely involves demonstrating that the proposed algorithm consistently approaches an optimal solution, either globally or locally, within a defined set of conditions. The key aspects to look for include the rate of convergence, specifying how quickly the algorithm approaches the optimum (e.g., linear, sublinear, superlinear), and identifying any limiting factors or assumptions that influence the convergence behavior. For instance, the analysis might explore the impact of dimensionality, noise levels, or specific properties of the objective function on the algorithm’s convergence properties. A formal proof of convergence, often based on mathematical techniques such as bounding the error terms or using probabilistic arguments, might be presented to strengthen the claims. The analysis could also compare the convergence properties of the proposed algorithm to existing methods, providing a quantitative assessment of its performance. Establishing convergence is not merely an academic exercise; it provides confidence in the algorithm’s practical utility and ensures that it will perform reliably in real-world applications.

Empirical Evaluation#

A robust empirical evaluation section is crucial for validating the claims of a research paper. It should present a comprehensive set of experiments designed to thoroughly test the proposed method’s capabilities and limitations. Careful consideration of experimental design is paramount, including the choice of datasets (synthetic and real-world), evaluation metrics, and baseline algorithms for comparison. The evaluation should not only demonstrate superior performance compared to baselines but also provide insights into the method’s behavior under various conditions. Statistical significance testing is necessary to ensure the observed results are not due to random chance. Furthermore, the evaluation section needs to address potential confounding factors and highlight limitations of the approach. A detailed description of the experimental setup is necessary for reproducibility; and well-organized tables and figures that clearly present the results, including error bars or confidence intervals, contribute significantly to the overall impact of the evaluation. Finally, a thoughtful discussion of the results in context of the paper’s broader contributions is essential for a strong evaluation section. This section should avoid over-interpreting results and clearly state if the performance does not meet expectations.

Future Work#

The paper’s conclusion points towards several promising avenues for future research. One key area is a more rigorous theoretical analysis of the proposed LA-MinUCB algorithm, particularly focusing on establishing a tighter convergence rate compared to existing methods like GIBO. Another crucial aspect is exploring alternative, potentially more efficient, local exploitation strategies within the framework of minimizing the UCB. This could involve investigating different acquisition functions or incorporating advanced techniques like look-ahead strategies further to enhance performance. Furthermore, the authors acknowledge the need for a broader empirical evaluation across a wider range of synthetic and real-world functions and higher dimensions, to better understand the generalizability and robustness of their approach. Finally, a detailed examination of the algorithm’s sensitivity to various hyperparameters is warranted to provide more practical guidance for users. Investigating alternative acquisition functions that do not rely on gradient estimation would also be a valuable area of exploration.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure compares UCB with gradient-based bounds (approximated gradient bound and gradient bound) to illustrate the advantage of minimizing UCB for finding the next point in Bayesian optimization. The left panel shows that UCB provides a tighter bound and its minimum point leads to better performance than gradient descent. The right panel shows how UCB varies across the design space, demonstrating its suitability as a local search strategy because it is small only near the sampled point and increases as the distance increases.

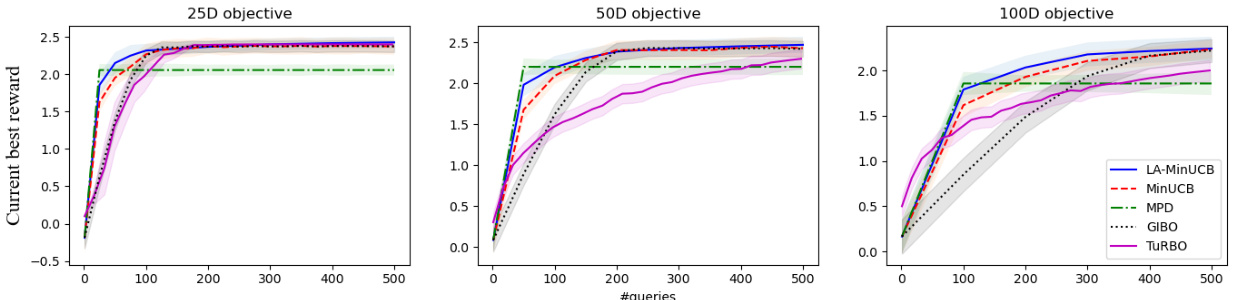

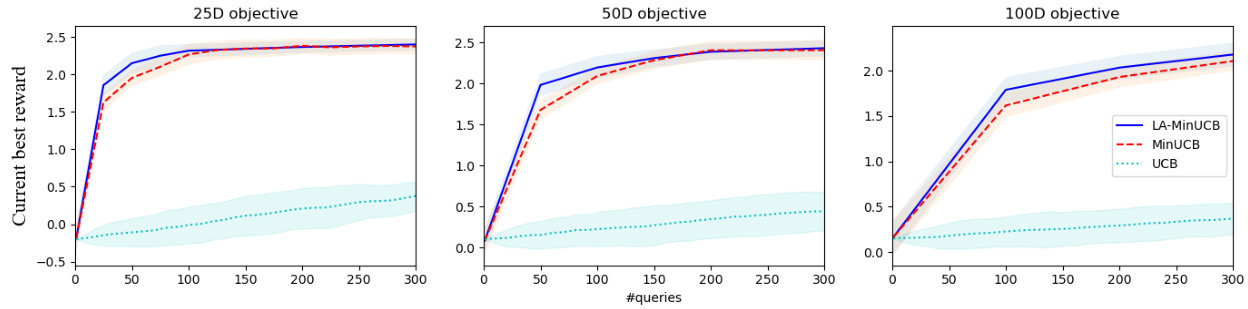

This figure compares the performance of LA-MinUCB with four other Bayesian Optimization algorithms (MinUCB, MPD, GIBO, and Turbo) on high-dimensional synthetic functions with dimensions of 25, 50, and 100. The y-axis represents the progressive optimized reward (the best objective function value found so far), and the x-axis represents the number of function evaluations (queries). The shaded regions around each line represent the standard deviation across multiple trials. The results show that LA-MinUCB consistently converges faster and achieves a higher reward than the other methods, demonstrating its superior performance in high-dimensional settings.

This figure presents the progressive optimized reward on three MuJoCo tasks (CartPole, Swimmer, and Hopper) across multiple queries. The results demonstrate the performance of LA-MinUCB against other local Bayesian optimization methods (MinUCB, MPD, GIBO, and TurBO). LA-MinUCB consistently achieves the highest reward, indicating superior performance in finding optimal solutions in these reinforcement learning tasks. Error bars representing variability are included for each algorithm.

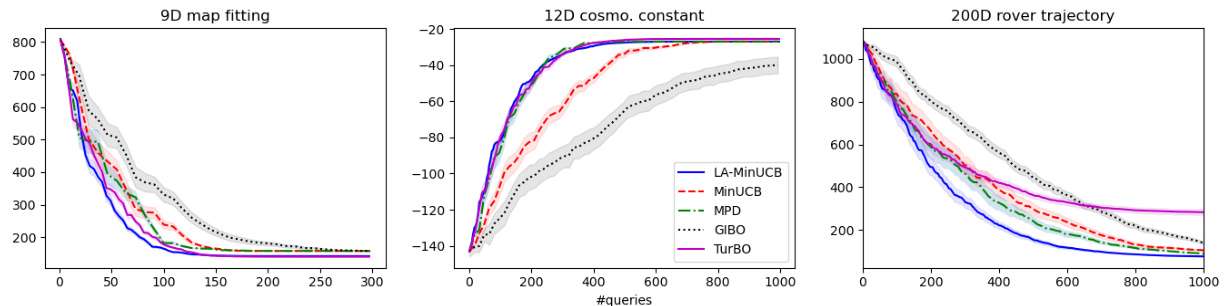

This figure presents the results of applying the LA-MinUCB algorithm and other benchmark algorithms on three real-world tasks: 9D map fitting, 12D cosmological constant, and 200D rover trajectory. The x-axis represents the number of function evaluations (queries), and the y-axis shows the progressive optimized reward (objective value) achieved by each algorithm. The shaded regions around each line represent confidence intervals. The figure demonstrates that LA-MinUCB consistently achieves competitive or superior performance compared to GIBO, MPD, and TurBO across all three tasks, highlighting its effectiveness in real-world scenarios.

This figure compares the performance of LA-MinUCB, MinUCB, and a traditional UCB method on three synthetic objective functions with 25, 50, and 100 dimensions. The y-axis represents the current best reward found, and the x-axis represents the number of queries (function evaluations). The shaded areas represent the standard deviation across multiple runs. The results show that LA-MinUCB and MinUCB significantly outperform the traditional UCB approach, particularly in higher dimensions, converging faster to better solutions.

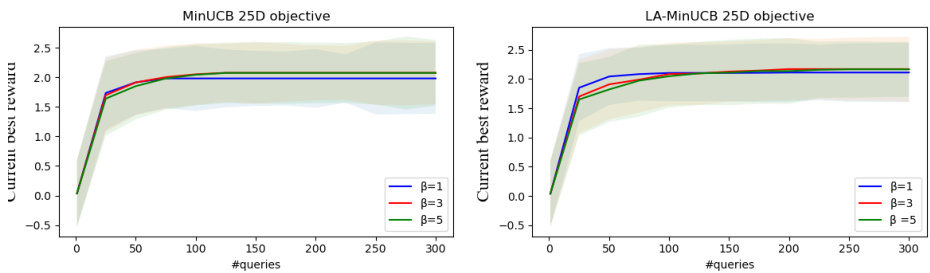

This figure displays the progressive optimized reward on a 25-dimensional synthetic function for different values of beta (β = 1, 3, and 5) in both MinUCB and LA-MinUCB algorithms. The shaded area represents the standard deviation across multiple runs. It demonstrates the performance of the algorithms with varying degrees of exploration-exploitation trade-off controlled by the beta parameter.

This figure displays the results of progressive objective values observed on a synthetic function with a dimensionality (D) of 50. The graph shows the performance of MinUCB and LA-MinUCB algorithms, each tested with different values of the beta (β) parameter (β=1, β=3, β=5). The beta parameter influences the algorithm’s exploration-exploitation balance; smaller betas prioritize exploration, while larger betas favor exploitation. The shaded regions around each line represent the standard deviation across multiple runs of the experiment, indicating the variability in performance. The x-axis represents the number of function evaluations (queries), and the y-axis displays the current best objective value found so far. This allows a visual comparison of the convergence speed and stability of the two algorithms under varying exploration-exploitation strategies.

This figure shows the progressive optimized reward on the 100-dimensional synthetic function for MinUCB and LA-MinUCB with different beta values (1, 3, and 5). The shaded area represents the standard deviation. The results illustrate how the choice of beta affects the convergence speed and final reward for both algorithms.

Full paper#