↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training large AI models is expensive and energy-intensive. Analog in-memory computing (AIMC) offers a promising solution but faces challenges. Current training methods like stochastic gradient descent (SGD) struggle to converge accurately due to the inherent asymmetry and noise in analog devices, resulting in significant asymptotic errors. This paper addresses this critical limitation.

This paper offers a rigorous theoretical analysis of AIMC training. It shows why standard methods fail and proposes a new discrete-time mathematical model to more precisely capture the non-ideal dynamics. The authors then introduce Tiki-Taka, a novel training algorithm that cleverly mitigates the effects of asymmetry and noise, thus eliminating asymptotic errors and showing exact convergence. This provides both a better theoretical understanding and a superior practical solution for training AI models on AIMC hardware.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in analog computing and AI hardware acceleration. It provides a much-needed theoretical foundation for gradient-based training on analog in-memory computing (AIMC) devices, addressing a critical gap in the field. The rigorous analysis of existing algorithms and the introduction of Tiki-Taka pave the way for more efficient and accurate AIMC training, impacting future AI hardware development. It also opens new avenues for investigating the convergence properties of analog algorithms and exploring novel training techniques.

Visual Insights#

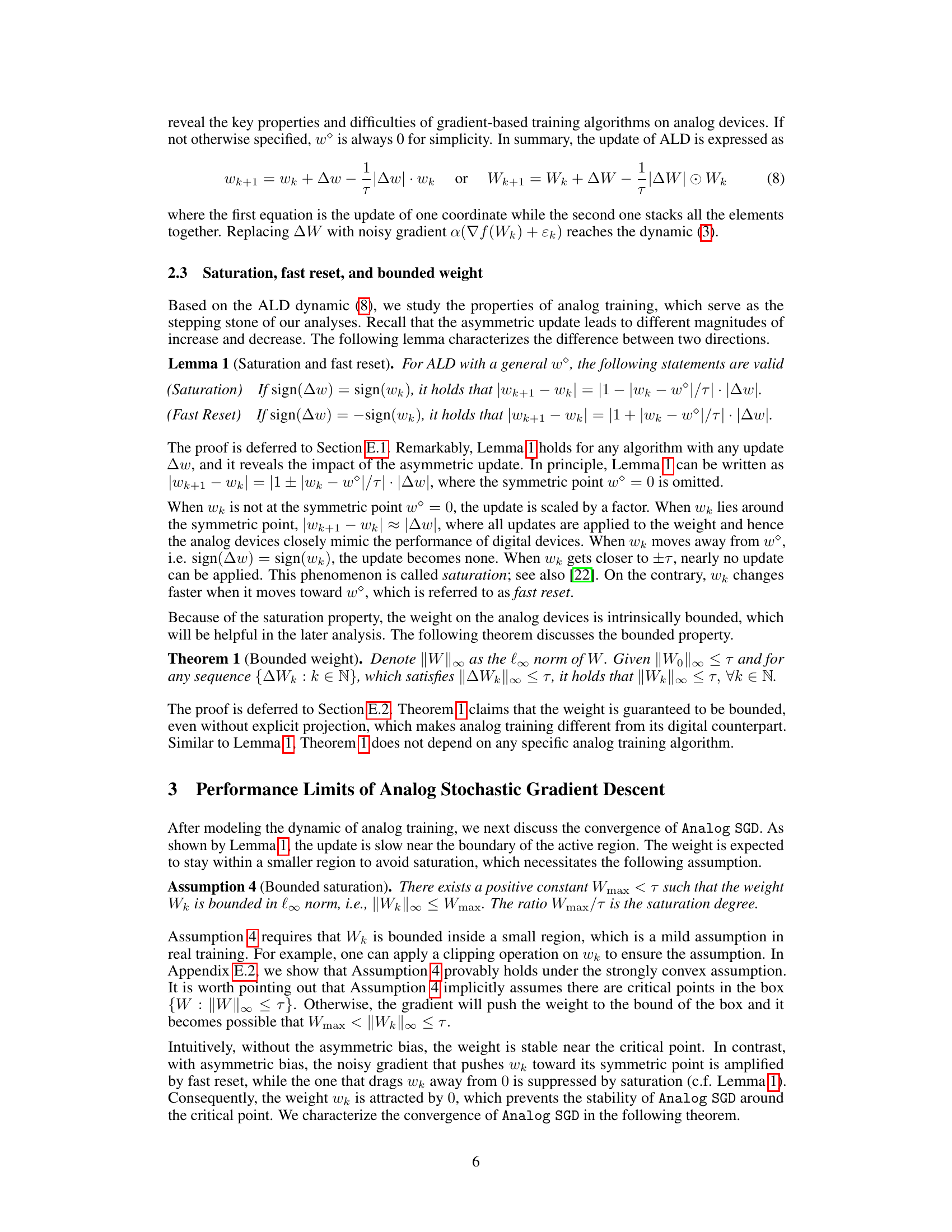

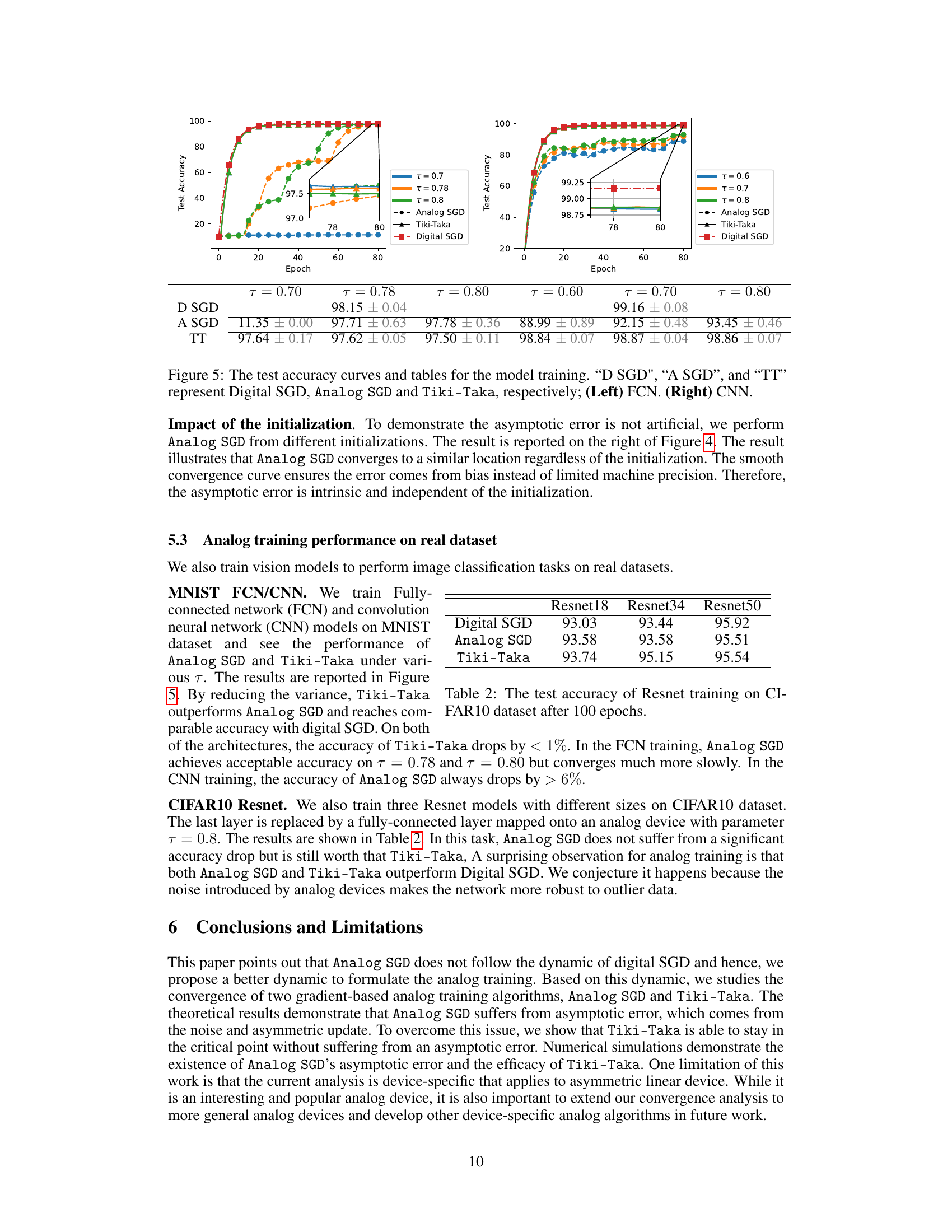

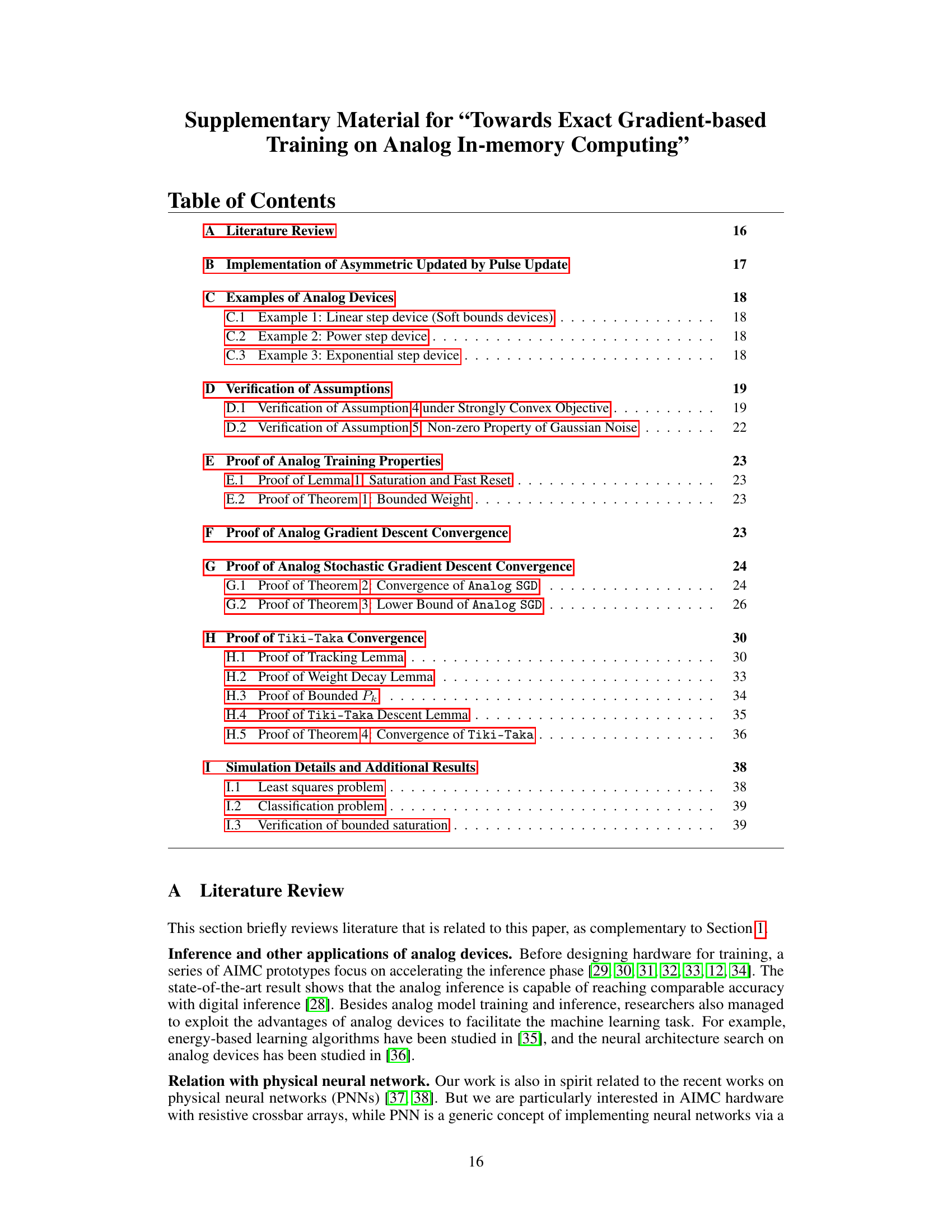

The figure shows a comparison of the convergence behavior of digital SGD and analog SGD under various learning rates (α). It demonstrates that digital SGD converges to a lower error as the learning rate decreases, while analog SGD exhibits an asymptotic error that persists even with small learning rates. This highlights a key difference in training dynamics between digital and analog devices.

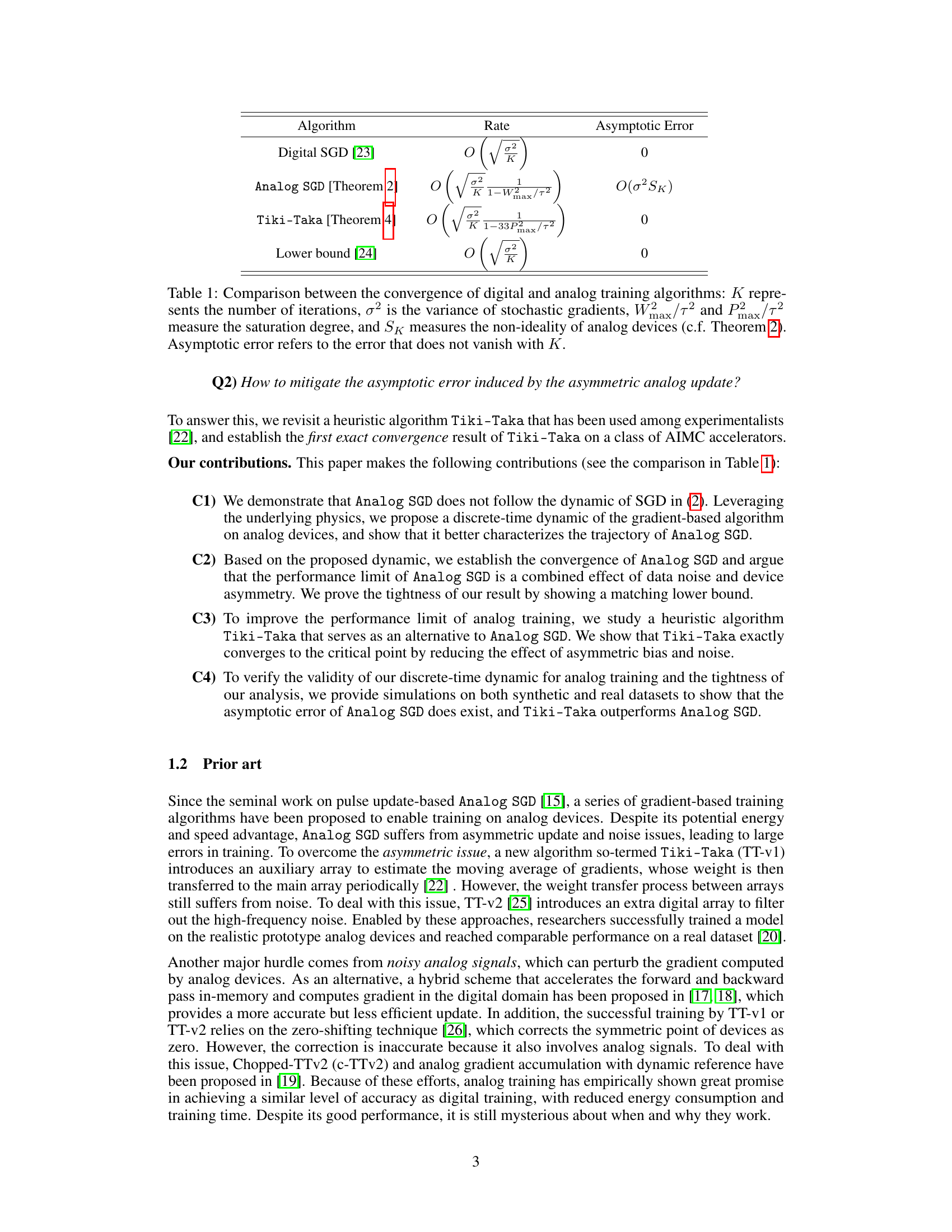

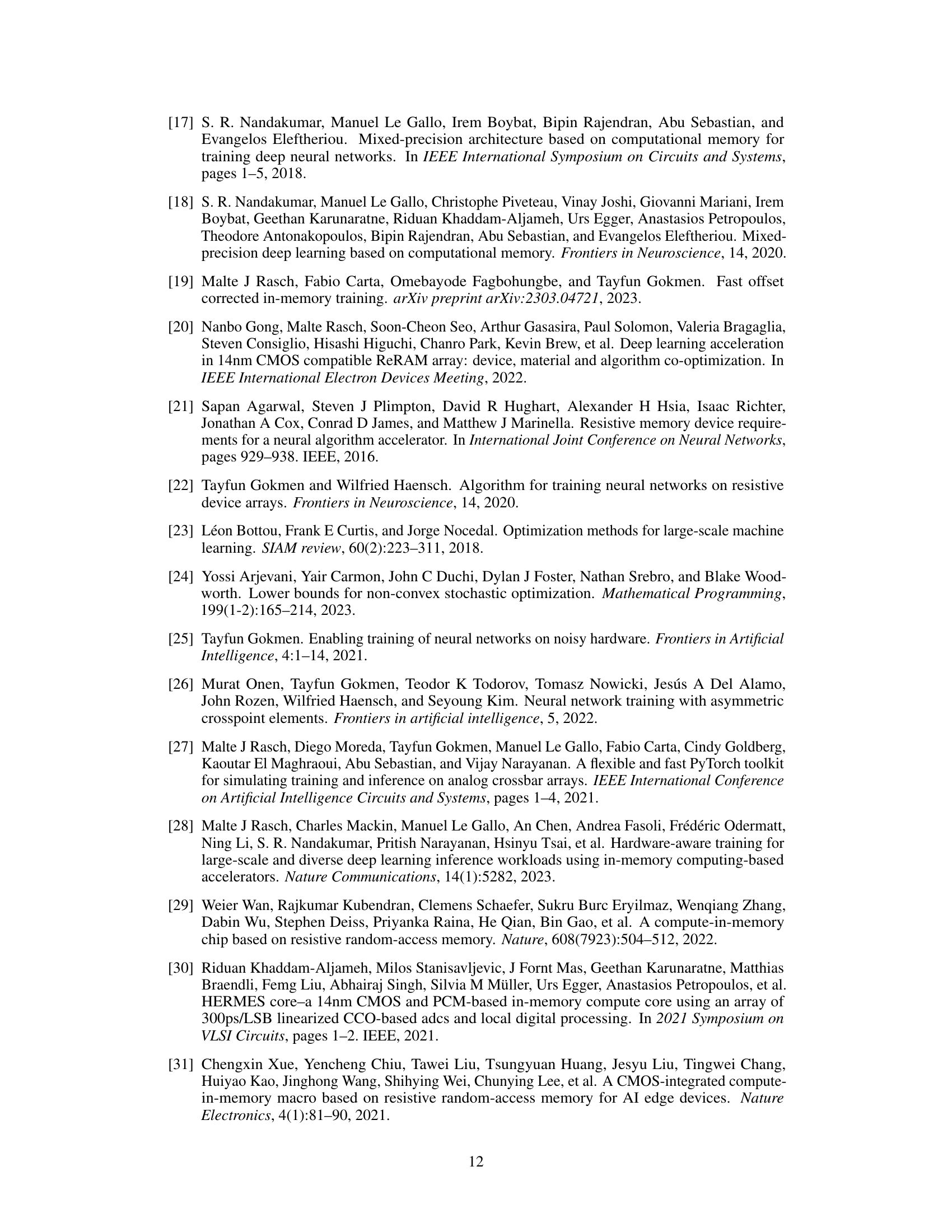

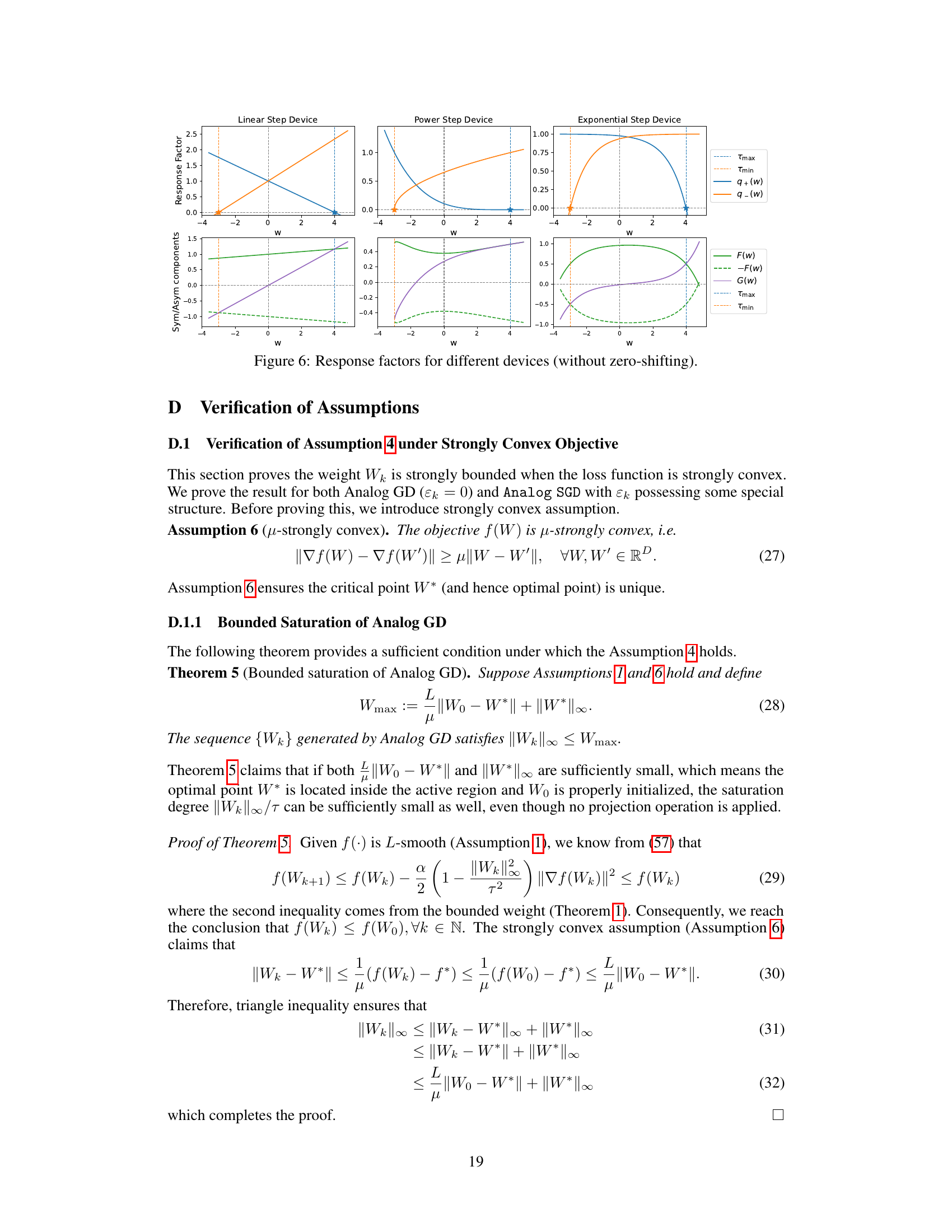

This table compares the convergence rates and asymptotic errors of four different training algorithms: Digital SGD, Analog SGD, Tiki-Taka, and a lower bound. It shows how the asymptotic error is affected by factors like the variance of stochastic gradients and device non-ideality, highlighting Tiki-Taka’s ability to eliminate this error.

In-depth insights#

Analog SGD Limits#

Analog SGD, while promising for energy-efficient AI, faces limitations when implemented on real-world analog in-memory computing (AIMC) devices. The inherent asymmetry in analog updates, unlike the symmetrical updates of digital SGD, causes the algorithm to converge to a suboptimal solution with a persistent asymptotic error. This error is not simply a consequence of noisy devices, but fundamentally arises from the device’s non-ideal characteristics. The paper rigorously demonstrates this asymptotic error by characterizing the analog training dynamics and establishing a lower bound for this inherent error. This indicates a fundamental performance limit of SGD on AIMC accelerators, highlighting the need for more sophisticated training algorithms. The exact nature of the asymptotic error is further shown to be influenced by factors such as the saturation degree and data noise. This analysis underscores the limitations of directly applying digital training methods to the analog domain and motivates the exploration of alternative algorithms, like Tiki-Taka, which demonstrates improved empirical results by addressing some of these limitations.

Tiki-Taka Analysis#

The Tiki-Taka algorithm, presented as a heuristic for mitigating the asymptotic error in Analog SGD training, warrants a thorough analysis. Its core innovation lies in employing an auxiliary array (Pk) to estimate the true gradient, reducing the impact of noise and asymmetry inherent in analog devices. A key question is whether Tiki-Taka’s empirical success stems from a fundamental advantage over Analog SGD or is merely a result of clever noise handling. Rigorous theoretical analysis is crucial to understand its convergence properties and to establish whether it provably converges to a critical point unlike the inexact convergence of Analog SGD. A key aspect of the analysis should be on comparing the convergence rates and asymptotic errors of Tiki-Taka and Analog SGD. This comparison should focus on how the algorithm handles noise and asymmetry, and if it successfully eliminates asymptotic error, achieving exact convergence to a critical point. Simulation results, possibly comparing performance on benchmark datasets and varying levels of noise, are vital to validate the theoretical findings.

AIMC Physics#

Analog In-Memory Computing (AIMC) physics centers on understanding how the physical properties of analog devices influence the training process of neural networks. This involves analyzing the non-ideal behavior of analog components, such as the asymmetric update patterns caused by variations in conductance changes. These asymmetries, coupled with noise inherent in analog signals, lead to inexact gradient updates which significantly deviate from ideal stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithms. A key focus of research in AIMC physics is on modeling this non-ideal behavior accurately, often involving creating discrete-time mathematical models which capture both the asymmetric update dynamics and the effects of noise. This modeling is crucial for predicting performance limits and developing training algorithms specifically tailored to AIMC hardware which mitigate the limitations imposed by analog device physics, improving training accuracy and efficiency. A deep understanding of AIMC physics is essential to unlock the full potential of AIMC for energy-efficient AI.

Asymmetric Update#

The concept of “Asymmetric Update” in the context of analog in-memory computing (AIMC) training unveils a critical challenge stemming from the inherent non-idealities of analog devices. Unlike digital systems where weight updates are symmetric, AIMC devices exhibit asymmetric behavior, meaning that increasing a weight’s conductance may differ significantly from decreasing it. This asymmetry arises from the physical mechanisms governing conductance changes in the memory elements. This asymmetry introduces systematic errors, hindering the convergence of standard gradient-based training algorithms like stochastic gradient descent (SGD), often leading to inexact solutions. The paper highlights how these asymmetries and noise contribute to a fundamental performance limitation, introducing an asymptotic error that prevents exact convergence to a critical point. Addressing this requires careful consideration of device physics and the development of novel training algorithms designed to mitigate the effects of asymmetric updates, such as the Tiki-Taka algorithm proposed in the paper. Understanding the asymmetric update is therefore crucial for advancing AIMC training and fully realizing the potential energy efficiency of analog computing in the domain of AI. The authors rigorously analyze the influence of asymmetry and noise, providing a theoretical foundation for understanding and overcoming this critical limitation in AIMC training.

Future of AIMC#

The future of Analog In-Memory Computing (AIMC) is promising, yet faces significant hurdles. Hardware advancements are crucial; improving the accuracy, reliability, and scalability of analog components, especially resistive RAM (RRAM) and other emerging memory technologies, is paramount. Algorithm development needs to overcome the challenges posed by noise and device variability. Hybrid approaches, combining analog computation for matrix multiplications with digital processing for other operations, may offer a near-term practical path. Addressing the energy efficiency of training remains a key concern; analog training methods must significantly outperform digital counterparts to justify their adoption. Finally, developing robust and efficient training algorithms tailored to the inherent characteristics of AIMC is essential to unlock its full potential for large-scale AI applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

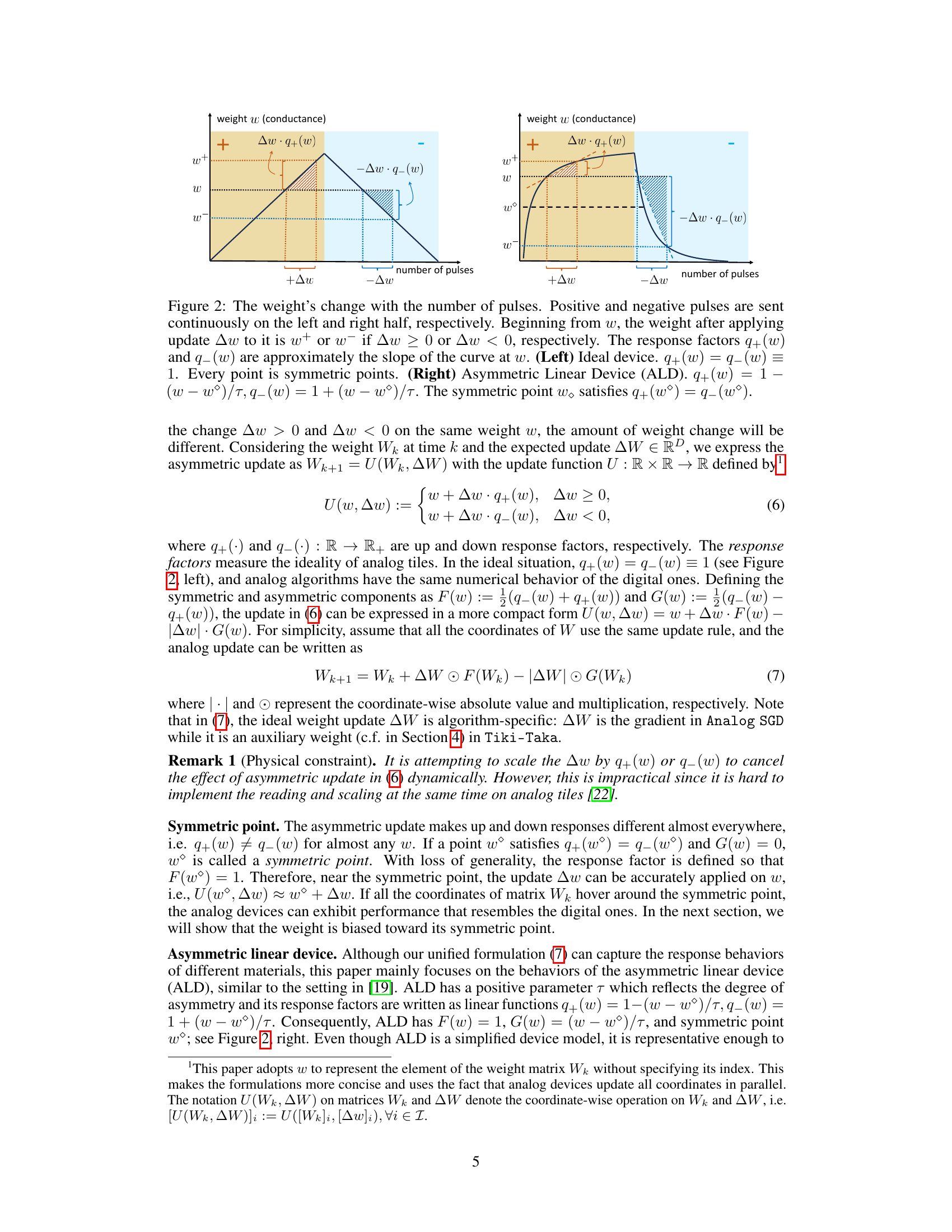

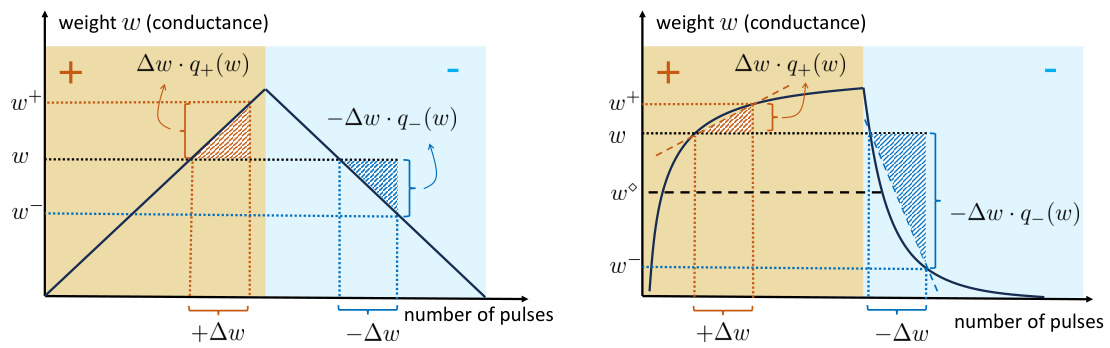

This figure illustrates the concept of asymmetric update in analog devices. The left panel shows an ideal device where positive and negative updates have the same effect. The right panel shows an asymmetric linear device (ALD), where positive and negative updates have different magnitudes due to the device’s non-ideal characteristics. The response factors q+(w) and q−(w) quantify the degree of asymmetry in the update.

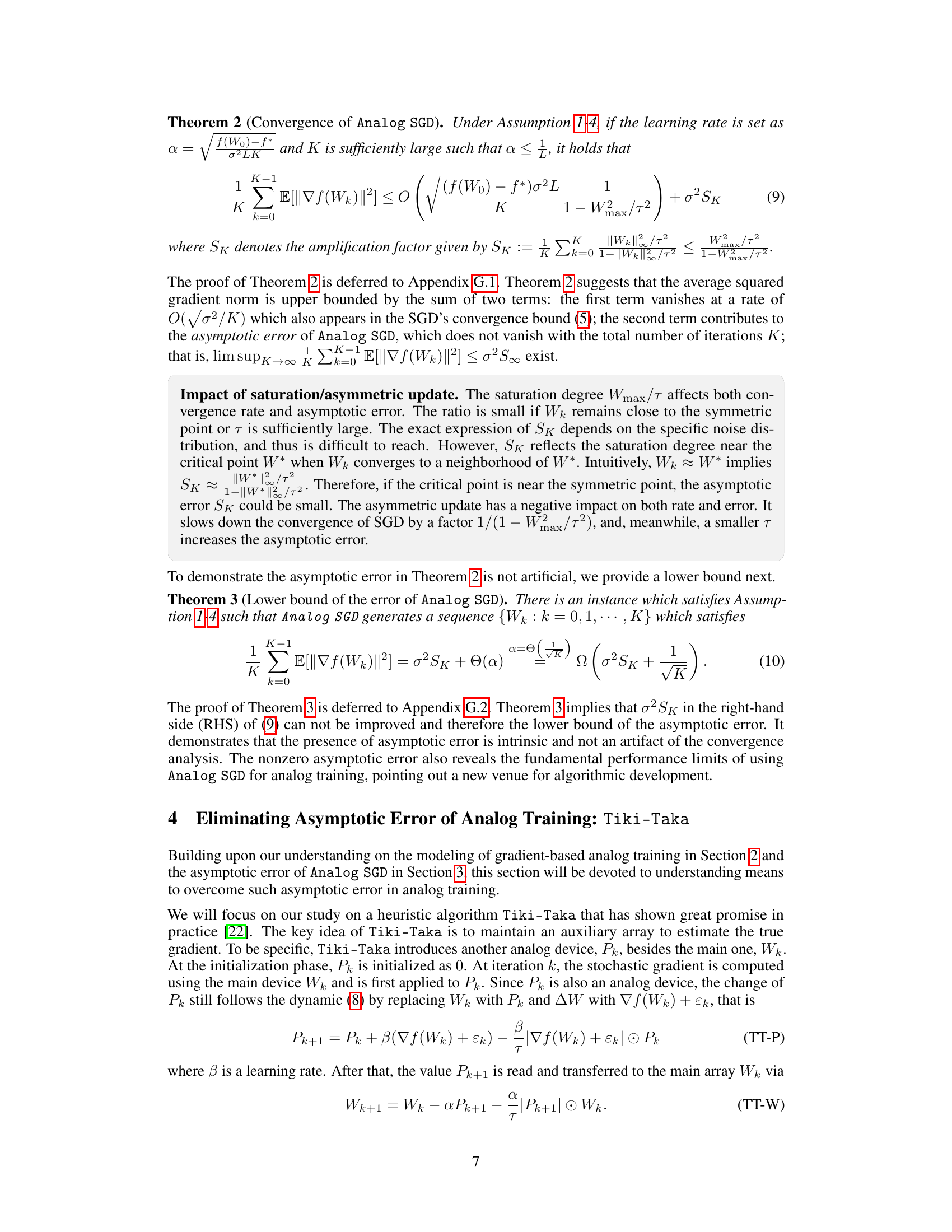

This figure compares the convergence behavior of three different methods for gradient descent: the theoretical digital SGD dynamic, the proposed analog dynamic model, and the actual results from simulations using the AIHWKIT simulator for analog devices. The comparison is performed for various values of τ (tau), a parameter that characterizes the asymmetry in the update process of analog devices. The results show the behavior of digital SGD and how the analog training deviates. The proposed analog dynamic model aligns better with the AIHWKIT simulation, especially with lower τ values.

This figure shows three subplots, each illustrating a different aspect of Analog SGD’s convergence behavior. The left subplot demonstrates how the asymptotic error decreases as τ increases. The middle subplot shows how increasing noise (σ²) affects the convergence behavior. The right subplot confirms that the asymptotic error is independent of the algorithm’s starting point (initialization).

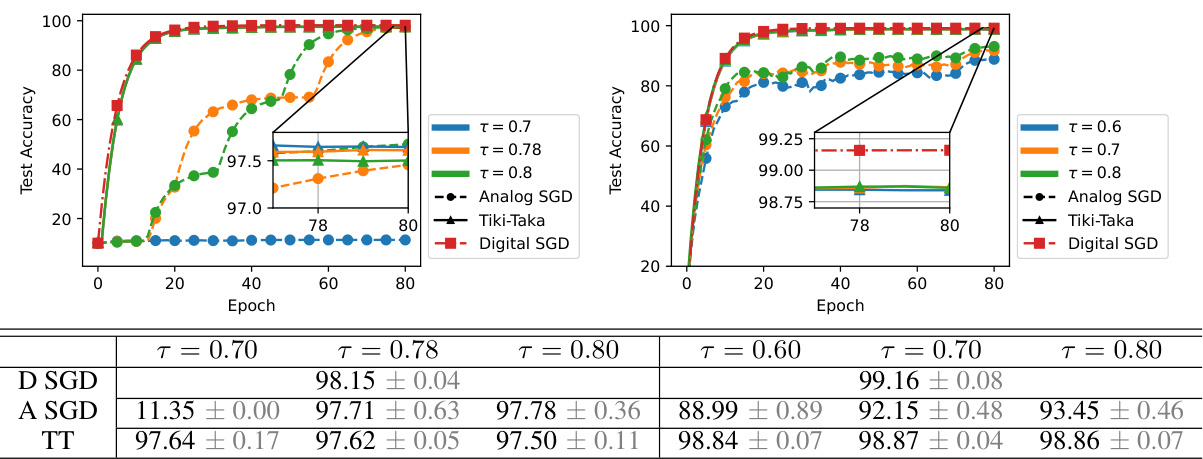

This figure shows the test accuracy results for three different training algorithms: Digital SGD, Analog SGD, and Tiki-Taka. The results are shown for two different model architectures: a Fully Connected Network (FCN) and a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). The plots illustrate the test accuracy over the number of training epochs for each algorithm and architecture. The tables provide a numerical summary of the final test accuracy achieved by each algorithm and architecture, along with standard deviation.

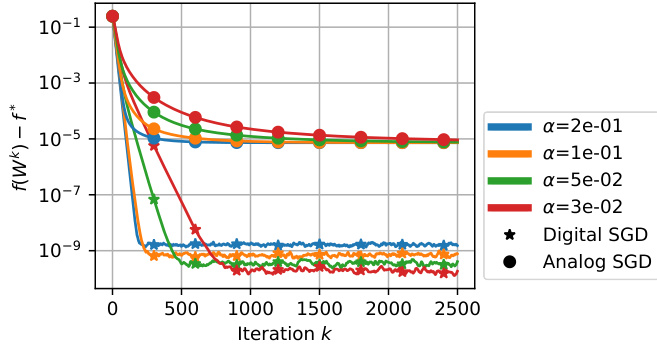

This figure shows the response factors (q+(w) and q−(w)) and their symmetric/asymmetric components (F(w) and G(w)) for three different types of analog devices: Linear Step Device, Power Step Device, and Exponential Step Device. The x-axis represents the weight (w), and the y-axis represents the response factor or component value. The plots illustrate how these factors vary with the weight, showing the different behaviors of each device type. This is particularly important for understanding the asymmetric update in analog training, as explained in the paper.

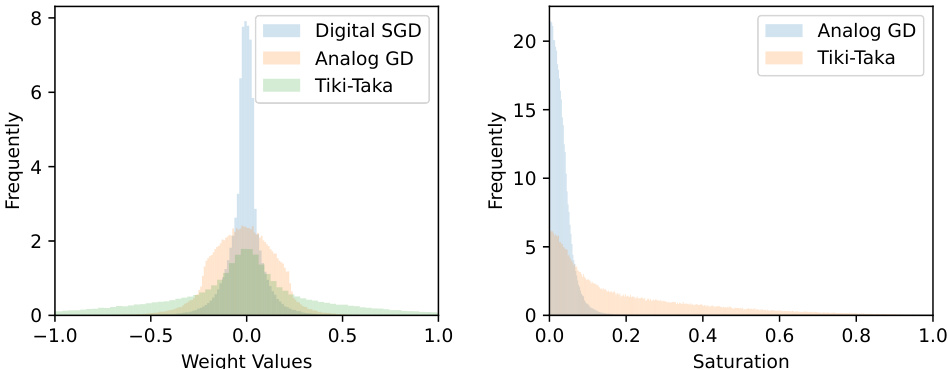

The figure shows the distribution of model weights and their saturation levels after training using three different algorithms: Digital SGD, Analog GD, and Tiki-Taka. The left panel displays the distribution of weight values for each algorithm, showing that Tiki-Taka’s weights are concentrated around zero. The right panel shows the distribution of saturation levels, which is the absolute value of the weights divided by the parameter tau (τ). This shows how close the weights are to the saturation boundary of the analog device. The distribution of Tiki-Taka’s saturation level is more spread out than the others, indicating less saturation of its weights.

Full paper#