↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current Large Language Model (LLM) evaluation relies heavily on static benchmarks, which have limitations like vulnerability to data contamination and inability to adapt to LLMs’ evolving capabilities. These static datasets lack flexibility and can’t reflect LLMs’ ever-increasing abilities. This makes it hard to fully understand LLM performance and potential biases.

To address this, the researchers introduce DARG (Dynamic Evaluation of LLMs via Adaptive Reasoning Graph). DARG dynamically extends current benchmarks by creating new test data with controlled complexity and diversity. It does this by modifying existing benchmarks’ reasoning graphs and using a code-augmented LLM to verify the new data’s labels. Testing 15 state-of-the-art LLMs across diverse tasks shows that most experienced performance drops with higher complexity. DARG also uncovered increased model bias at higher complexity levels, providing valuable insights for improved LLM evaluation and development.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the limitations of static benchmarks in evaluating LLMs by proposing a dynamic evaluation method. This directly impacts the field by enabling more robust and adaptive evaluations that better reflect LLM capabilities in diverse, evolving scenarios. The findings on model bias and sensitivity to complexity also offer valuable insights for future LLM development and responsible AI practices.

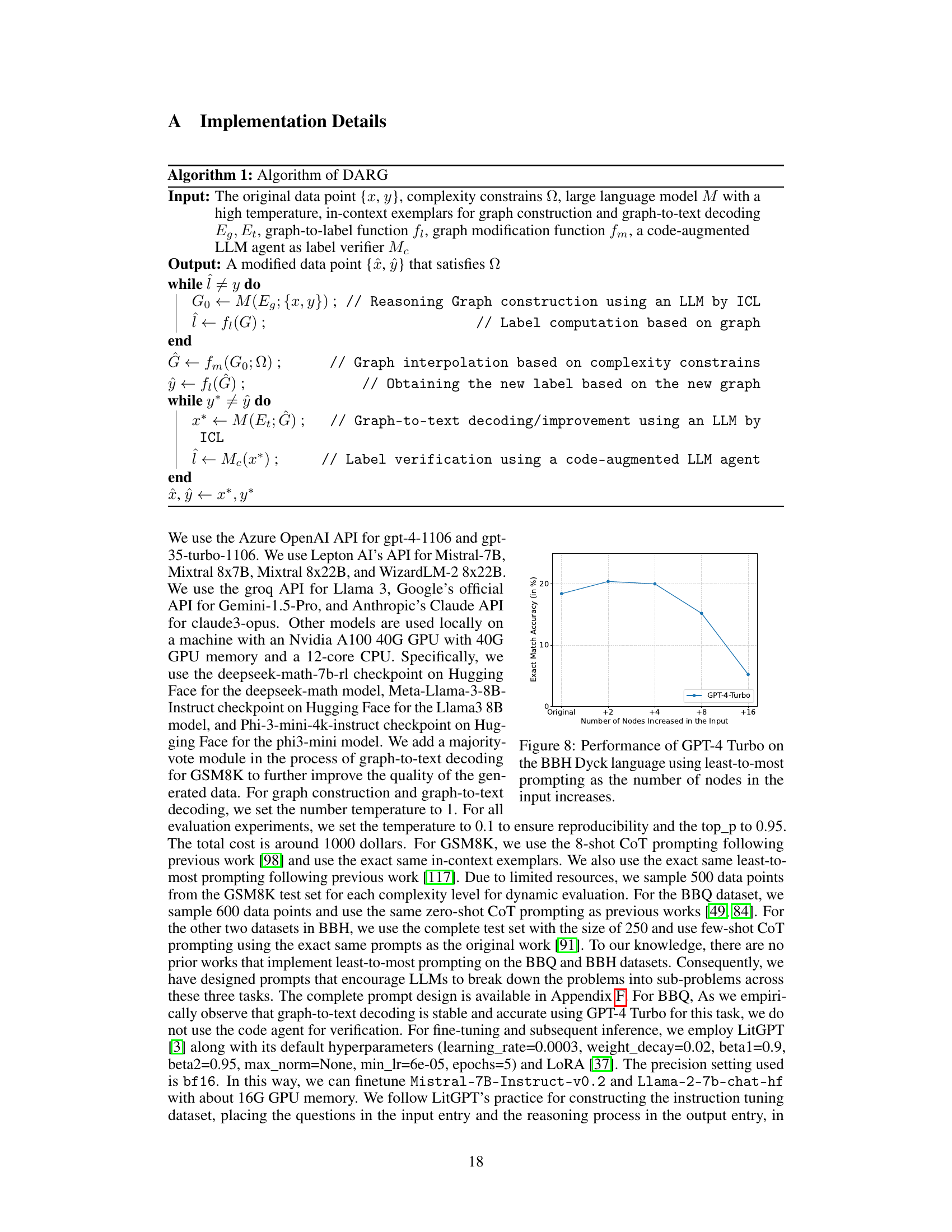

Visual Insights#

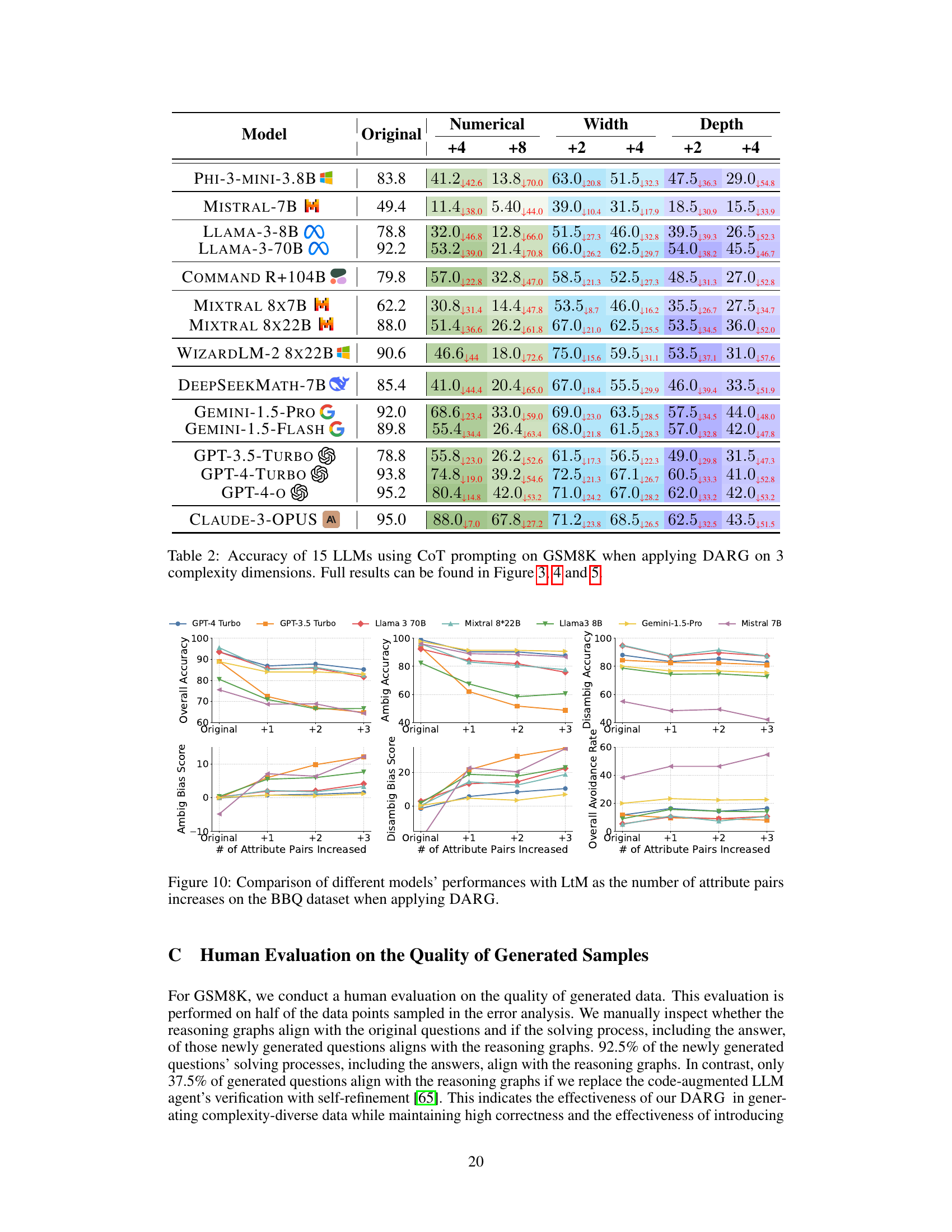

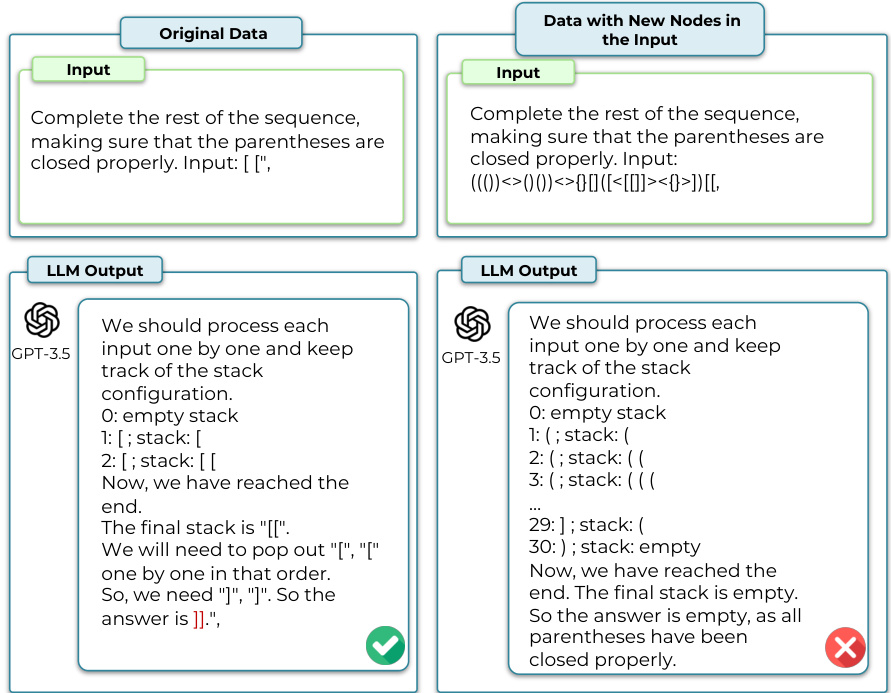

This figure illustrates the DARG framework, a dynamic evaluation method for LLMs. It begins by constructing reasoning graphs from existing benchmarks using an LLM. These graphs are then perturbed to create new data points with varying complexity levels. A code-augmented LLM verifies the accuracy of the generated data. The process involves three main stages: reasoning graph construction, graph interpolation to increase complexity, and new data point verification. The framework allows for the adaptive and dynamic evaluation of LLMs by continually creating new challenges.

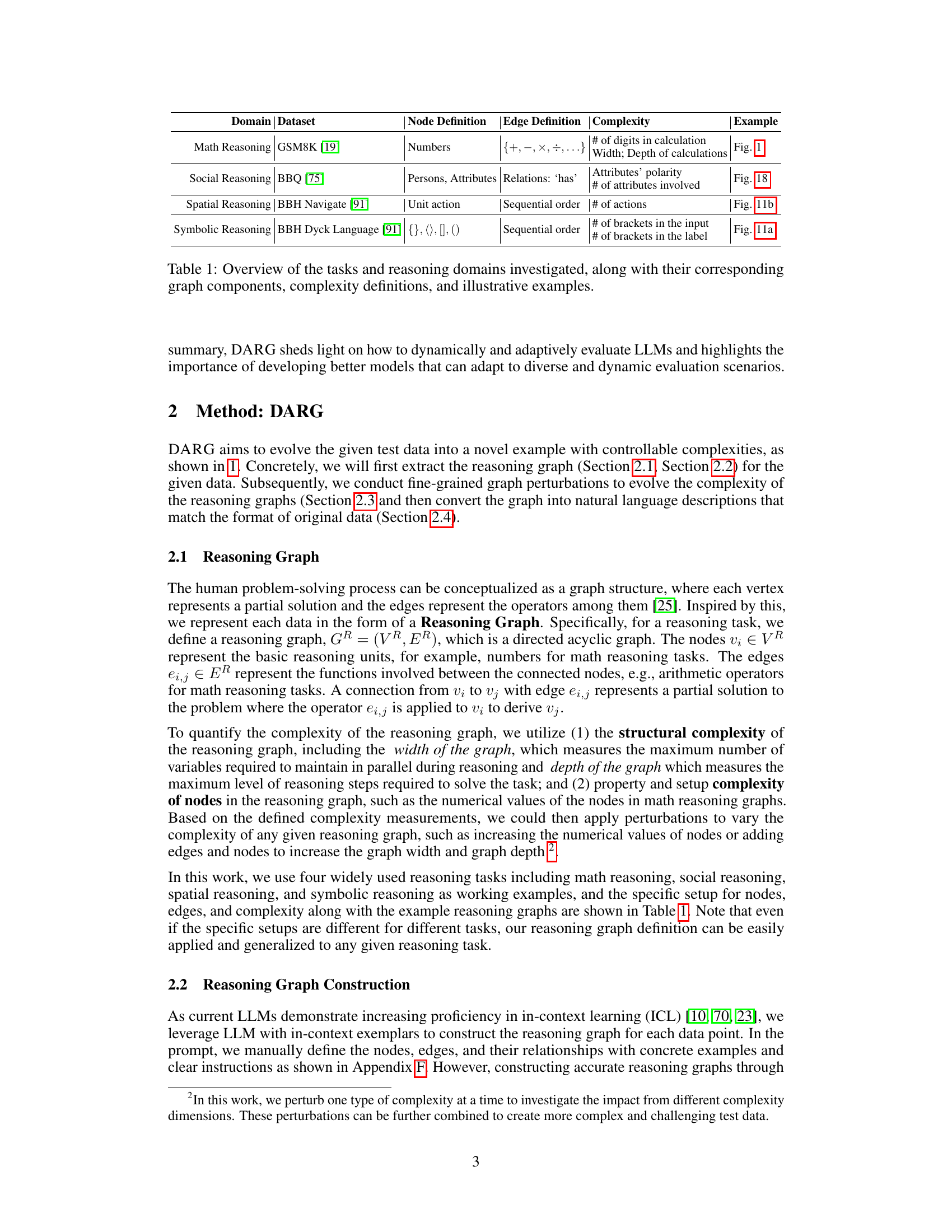

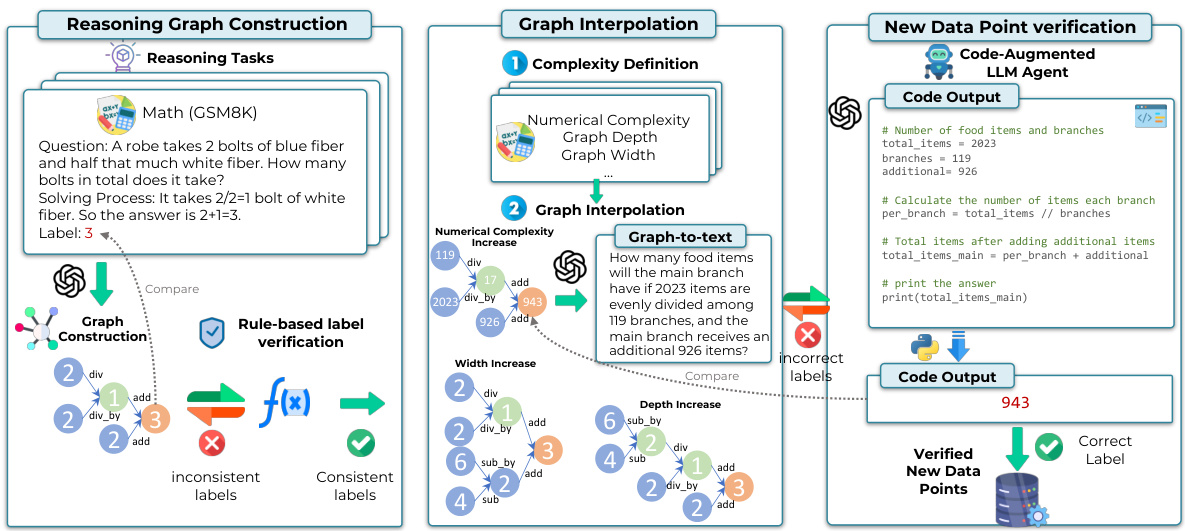

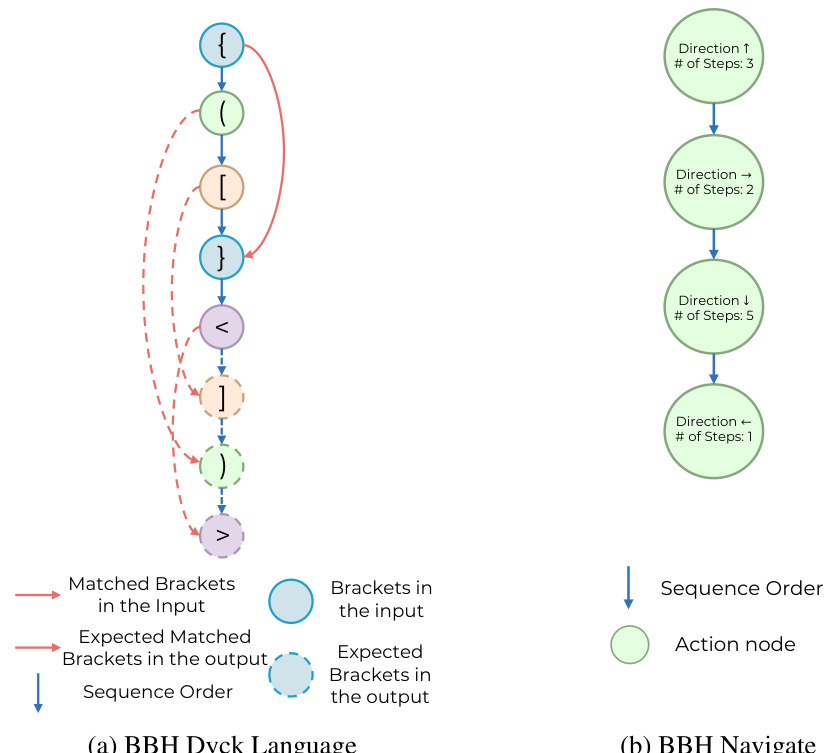

This table provides a comprehensive overview of the four reasoning tasks (Math, Social, Spatial, and Symbolic Reasoning) used in the DARG evaluation framework. For each task, it lists the specific dataset used, defines the structure of the reasoning graph (node and edge definitions), explains how complexity is measured for that task, and references a figure in the paper that illustrates an example of the reasoning graph for that task. The table serves to clarify the different types of reasoning tasks and how their complexity was manipulated within the DARG framework.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive Reasoning#

Adaptive reasoning, in the context of large language models (LLMs), signifies the ability of a system to dynamically adjust its reasoning strategies based on the specific characteristics of the input and the ongoing reasoning process. This contrasts with traditional LLMs that use a fixed approach for every input, regardless of its complexity or nuances. Effective adaptive reasoning requires the LLM to not only process information but also understand its context, identify any complexities or ambiguities, and select appropriate strategies for problem-solving. This might involve switching between different reasoning methods, dynamically incorporating external knowledge, or adjusting the level of detail in its reasoning steps. The development of adaptive reasoning in LLMs is a crucial step toward achieving more robust and versatile AI systems capable of handling a wider range of tasks with greater accuracy and efficiency. Key challenges in developing adaptive reasoning capabilities include the need for sophisticated mechanisms to identify and manage different reasoning strategies, to integrate these strategies seamlessly, and to ensure the correctness and reliability of the adaptive process. Furthermore, evaluating and comparing adaptive reasoning approaches is non-trivial. Benchmark datasets and evaluation metrics must be carefully designed to reflect the dynamic nature of adaptive reasoning and to avoid biases that may favor certain approaches over others. Therefore, future research must focus on developing robust and generalizable adaptive reasoning techniques and creating more appropriate evaluation methodologies.

Dynamic Benchmarks#

Dynamic benchmarks represent a significant advancement in evaluating large language models (LLMs). Unlike static benchmarks, which offer a fixed snapshot of LLM capabilities, dynamic benchmarks adapt and evolve, reflecting the continuous progress in LLM development. This adaptability is crucial because LLMs are constantly improving, and static evaluations may not accurately capture their current performance or potential biases. Dynamic benchmarks address this limitation by generating new, more complex, or diverse evaluation data, ensuring that LLMs are consistently challenged. This approach also allows researchers to explore the LLM’s generalization capabilities and robustness across a broader range of tasks and complexities. However, the design and implementation of dynamic benchmarks present several challenges. Ensuring data quality and avoiding bias are paramount. The methods used to generate new evaluation data must be carefully designed to prevent unintended biases and maintain linguistic diversity. Furthermore, the computational cost of generating and evaluating data dynamically can be high. Therefore, efficient algorithms and appropriate computational resources are crucial for the successful implementation of dynamic benchmarks.

Bias & Complexity#

The interplay between bias and complexity in large language models (LLMs) is a crucial area of investigation. Bias, often reflecting societal prejudices present in training data, can be amplified by increasing model complexity. More complex models, while potentially more capable, might not only perpetuate existing biases but also uncover and exacerbate latent ones previously unseen in simpler architectures. This is because increased complexity allows the model to discover and exploit more intricate patterns and relationships within the data, including those that reinforce harmful stereotypes. Conversely, simpler models may exhibit less bias due to their limited capacity to learn and represent complex, nuanced relationships, although they would inherently lack the same overall capabilities. Therefore, understanding and mitigating bias in LLMs necessitate not only careful data curation but also a balanced approach to model design. Striking a balance between complexity and bias is critical for creating robust and ethical LLMs that can effectively serve various applications without amplifying societal harm.

LLM Evaluation#

Large language model (LLM) evaluation is a complex and rapidly evolving field. Traditional static benchmarks, while offering a baseline, suffer from limitations like data contamination and an inability to adapt to the increasing capabilities of LLMs. This necessitates dynamic evaluation methods that can generate diverse test sets with controlled complexity, thus better assessing generalization and robustness. Adaptive reasoning graphs offer a promising approach, enabling the creation of novel test examples by strategically perturbing existing benchmarks at various levels, ensuring both linguistic diversity and controlled complexity. Code-augmented LLMs play a crucial role in verifying label correctness of these newly generated data points, increasing evaluation reliability. Evaluation should consider not only accuracy but also biases, exploring how LLMs respond to increasing complexity across different domains and task types. Bias detection and mitigation should be a central focus. Future research should explore ways to integrate diverse evaluation methods and further enhance the dynamic and adaptive nature of LLM evaluation.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore more sophisticated graph perturbation techniques to generate even more diverse and challenging test samples. This might involve incorporating different types of graph operations, exploring higher-order graph structures, or even developing methods for dynamically adapting the complexity of the graph based on the model’s performance. Furthermore, investigating the relationship between graph complexity and specific LLM biases is crucial. A more detailed analysis of why certain models struggle with specific types of graph perturbations could provide insights into architectural vulnerabilities or limitations in training data. Exploring alternative graph representations (e.g., knowledge graphs or Bayesian networks) is also warranted to determine if different representations would provide additional value or uncover new weaknesses in LLMs. Finally, research could focus on improving the efficiency and scalability of the DARG framework, particularly for very large language models and datasets, which may involve optimizing graph construction and perturbation algorithms or developing parallel implementations.

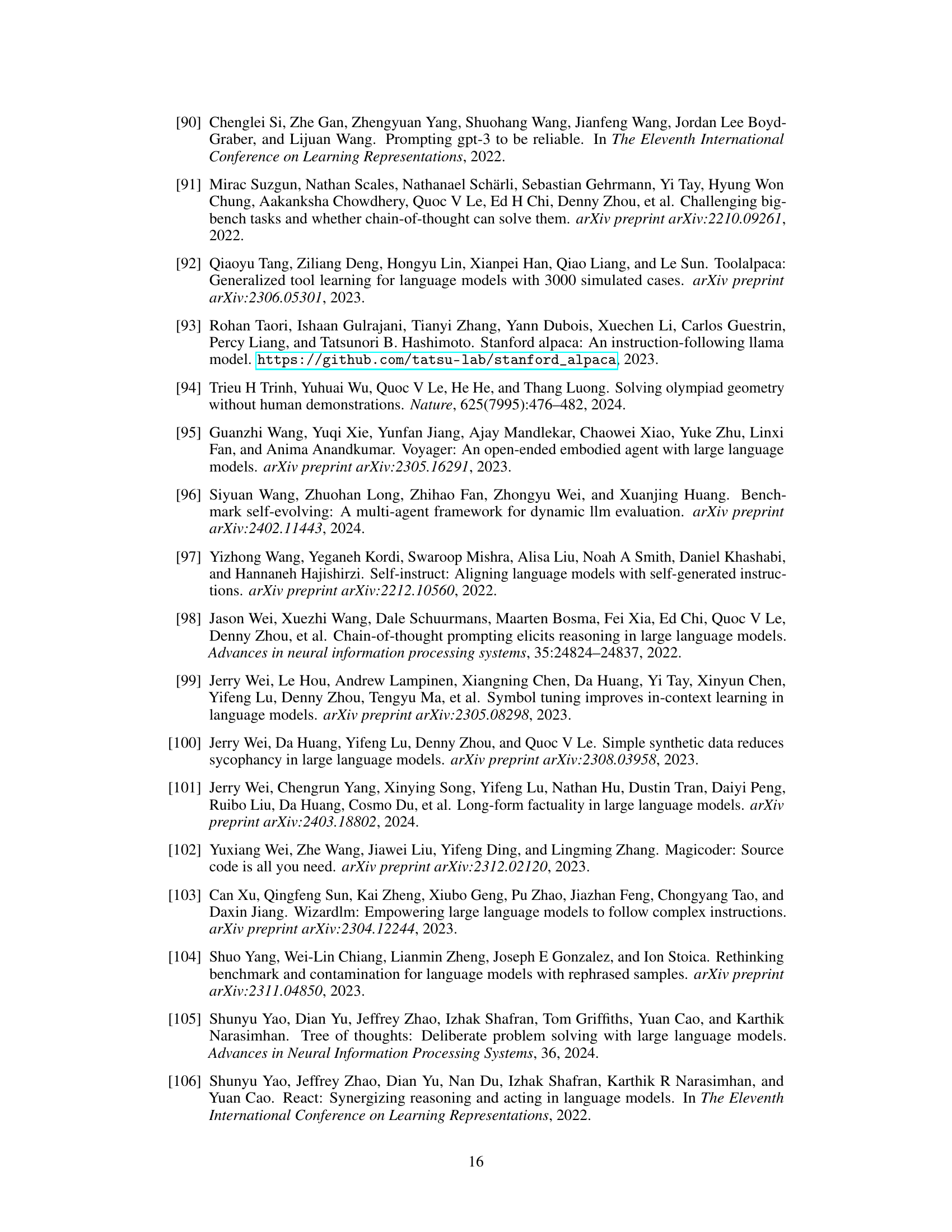

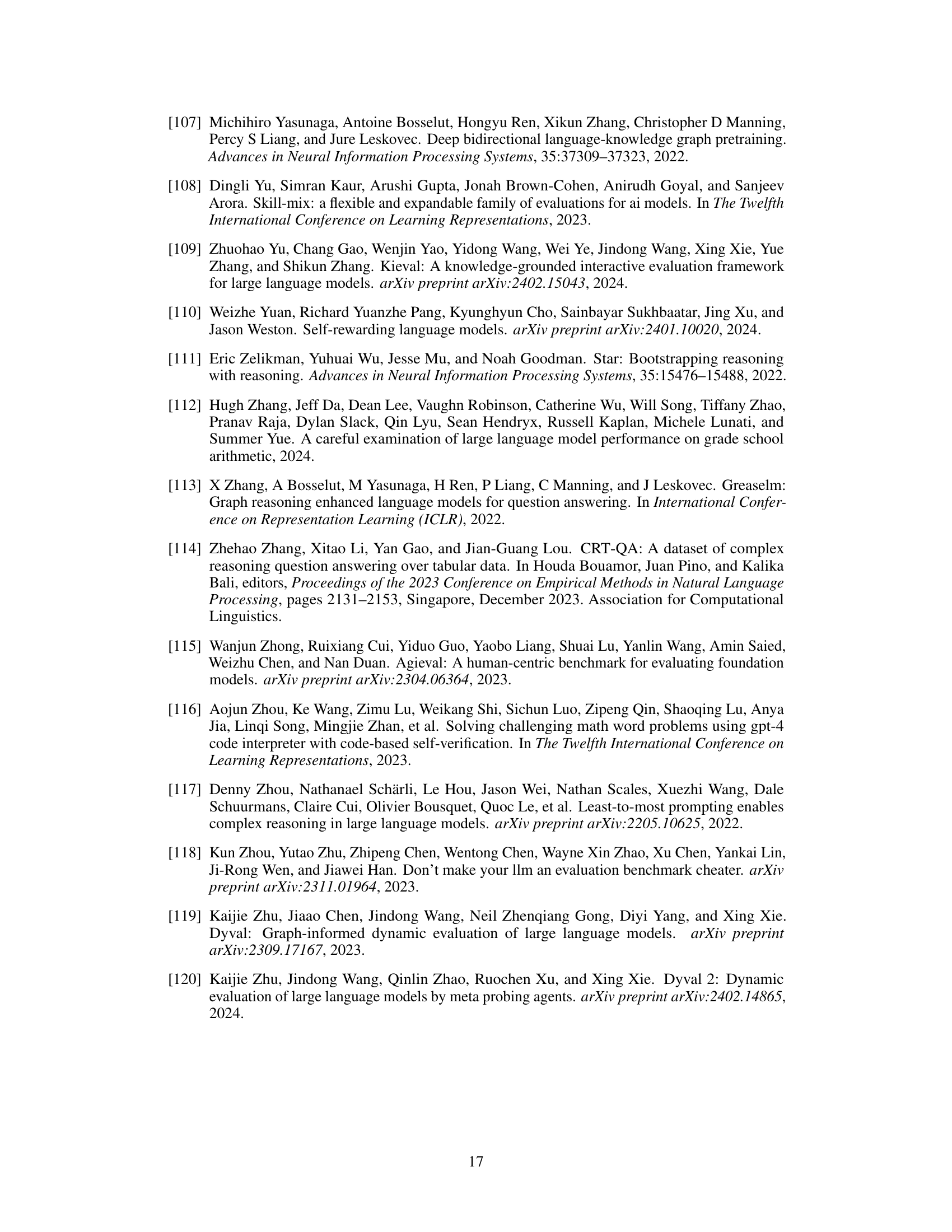

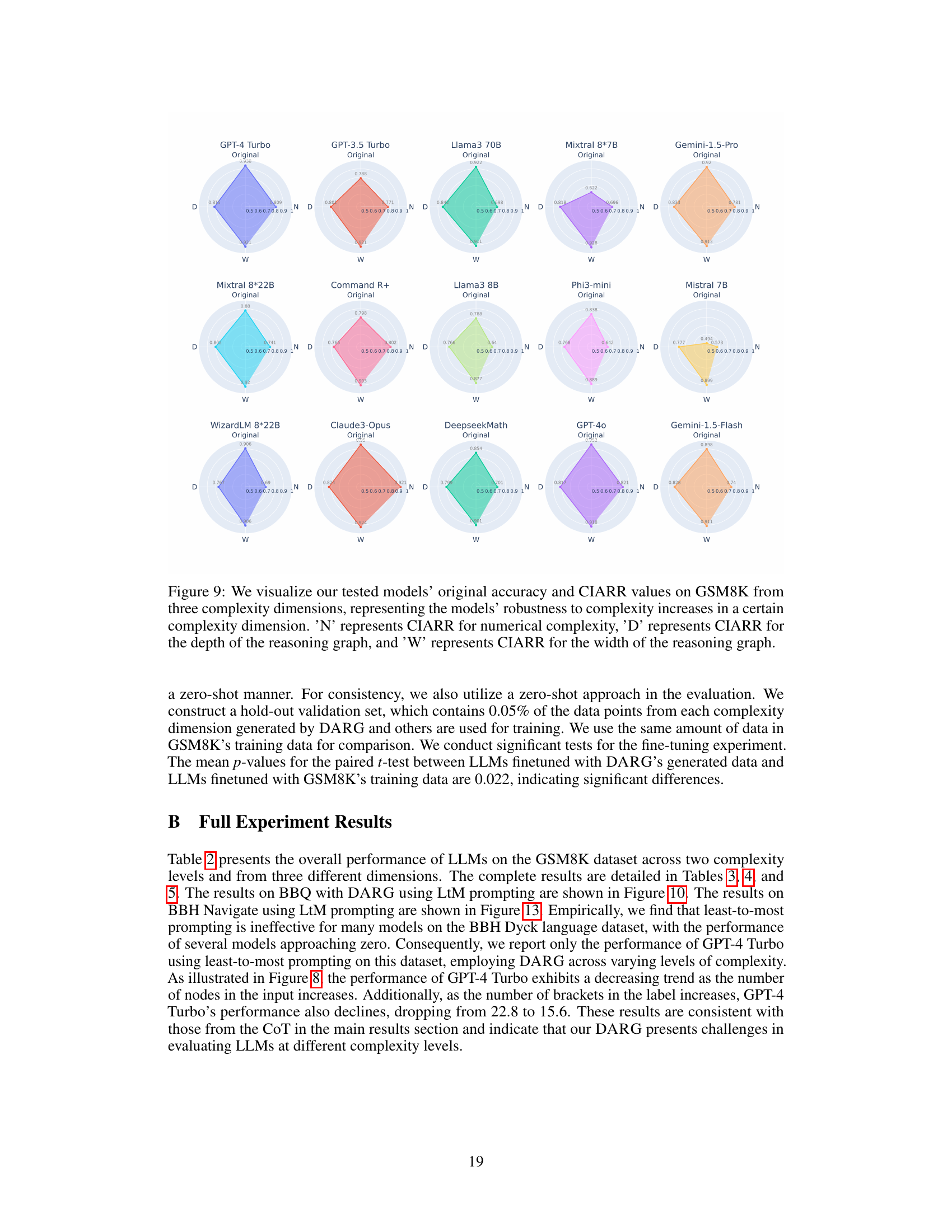

More visual insights#

More on figures

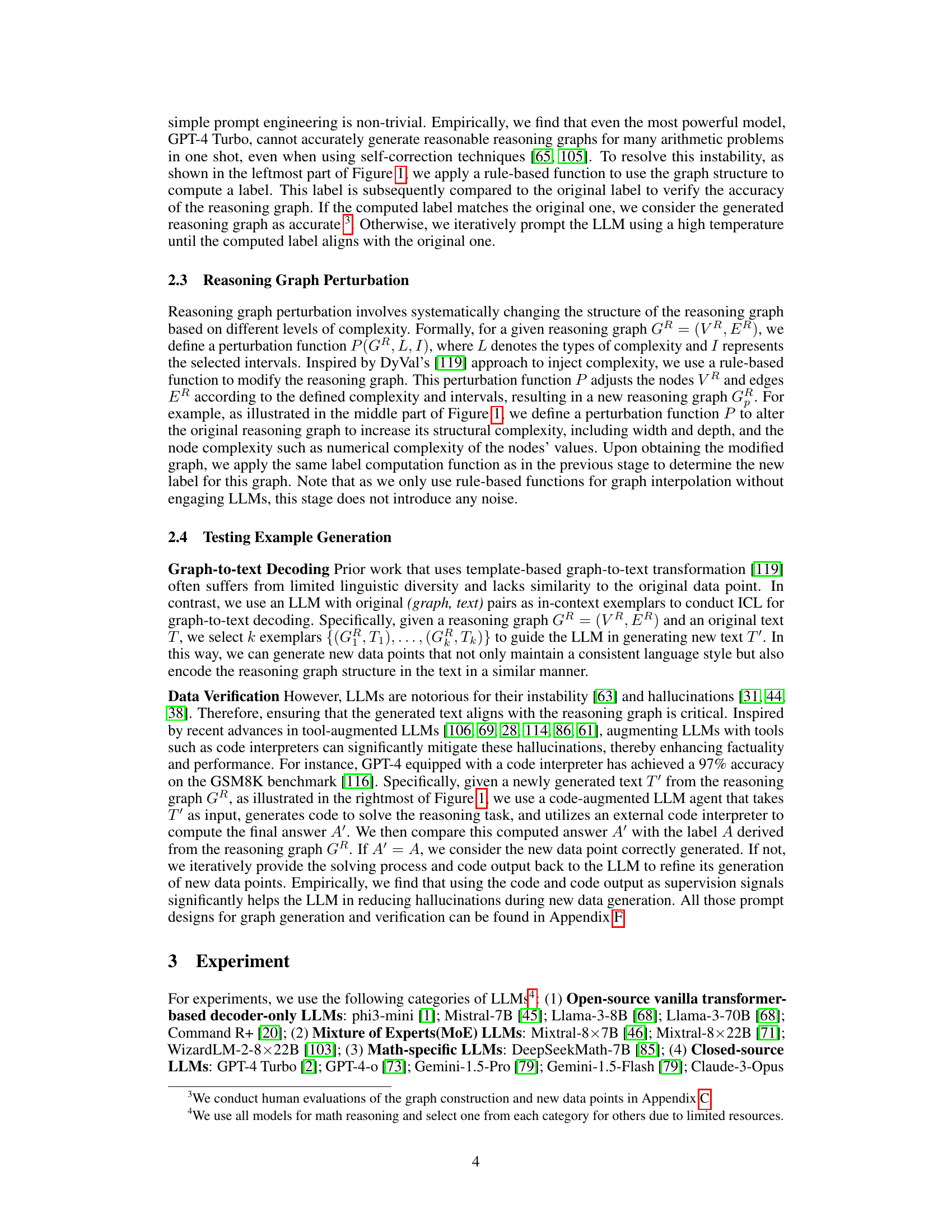

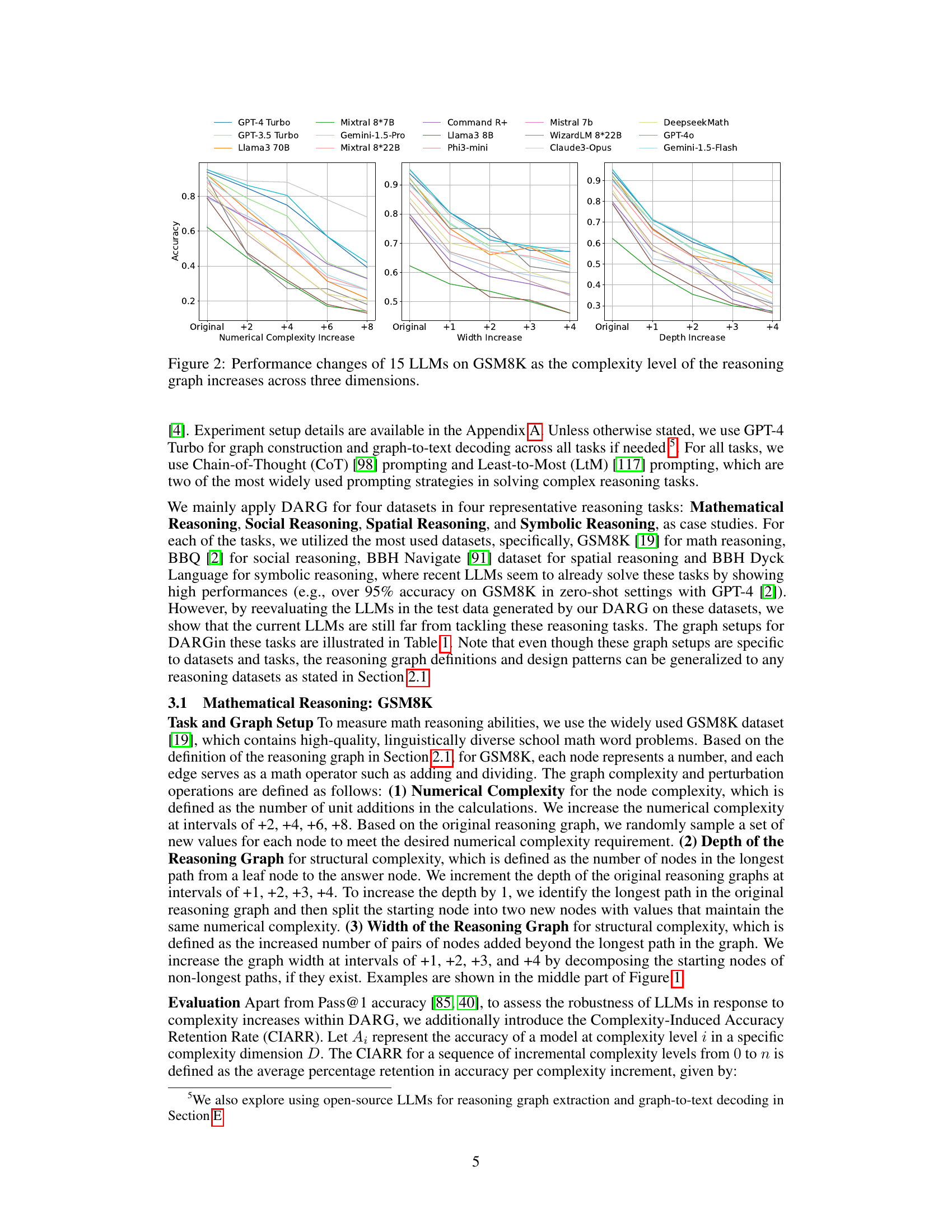

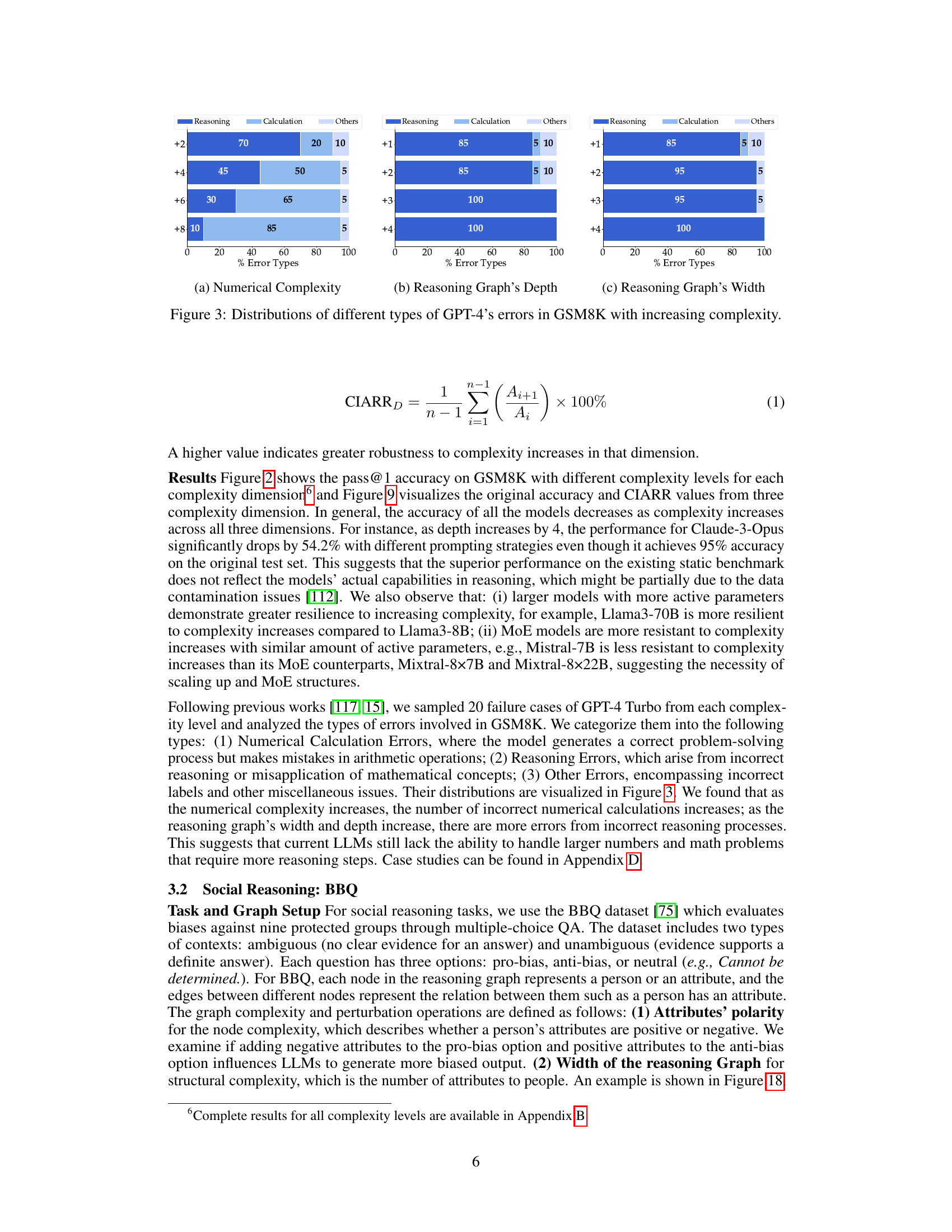

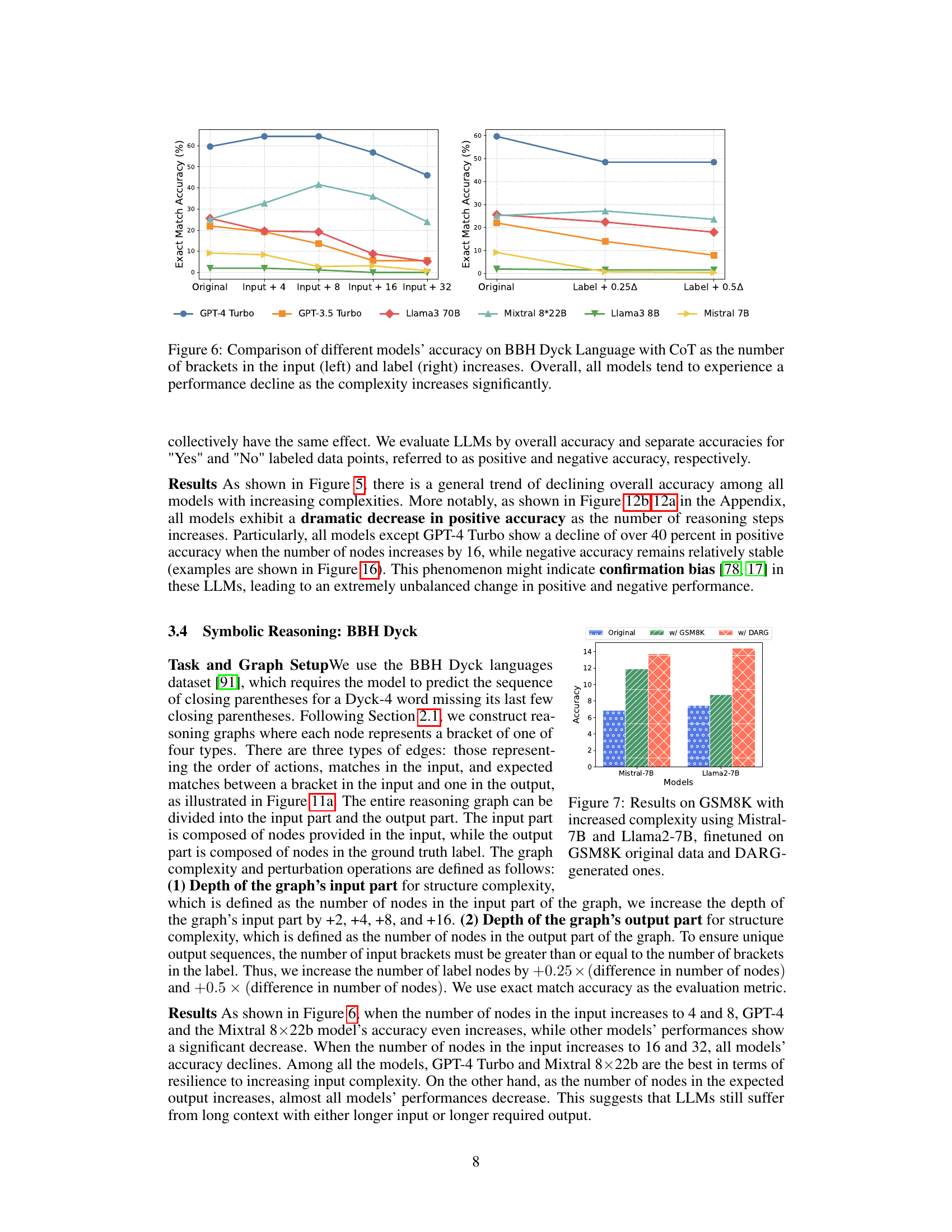

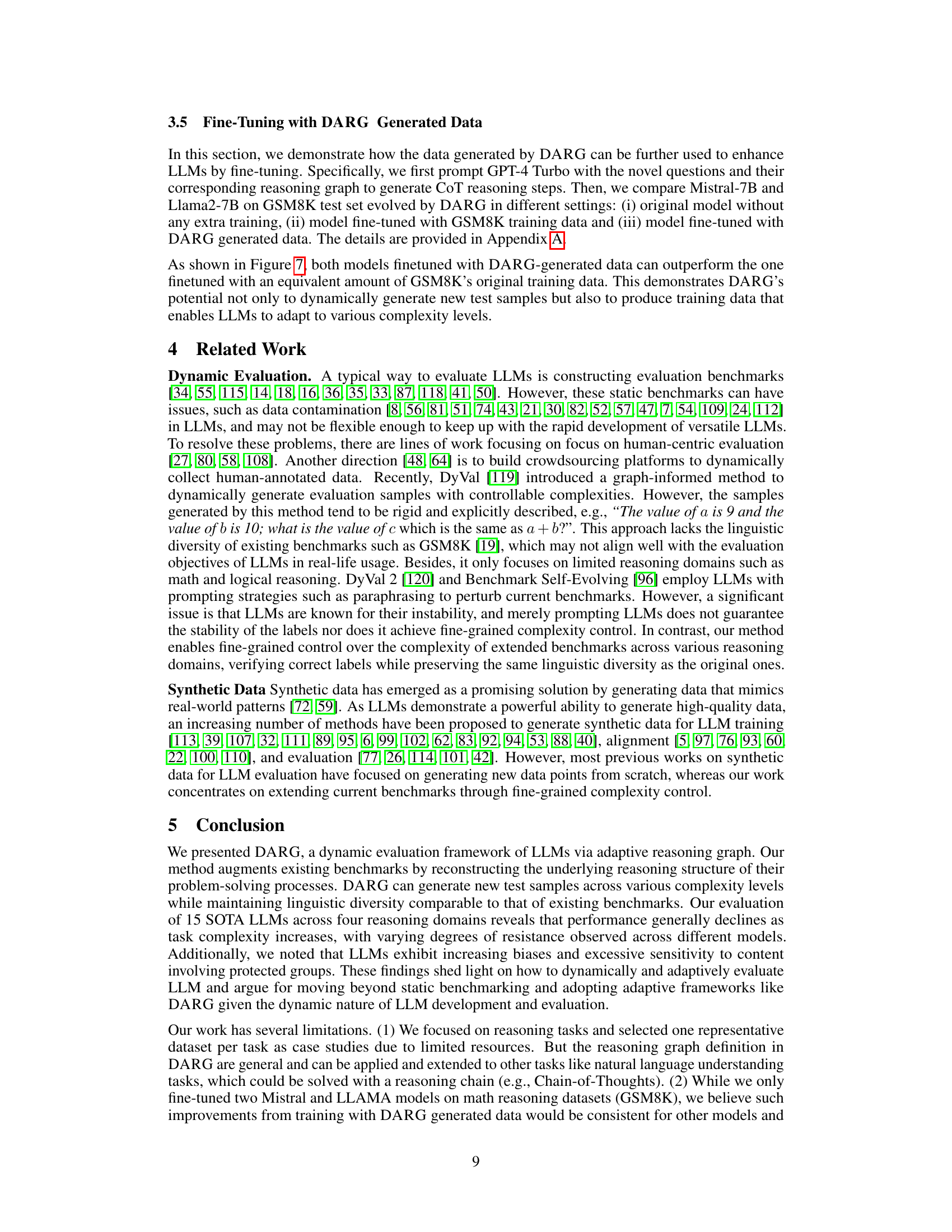

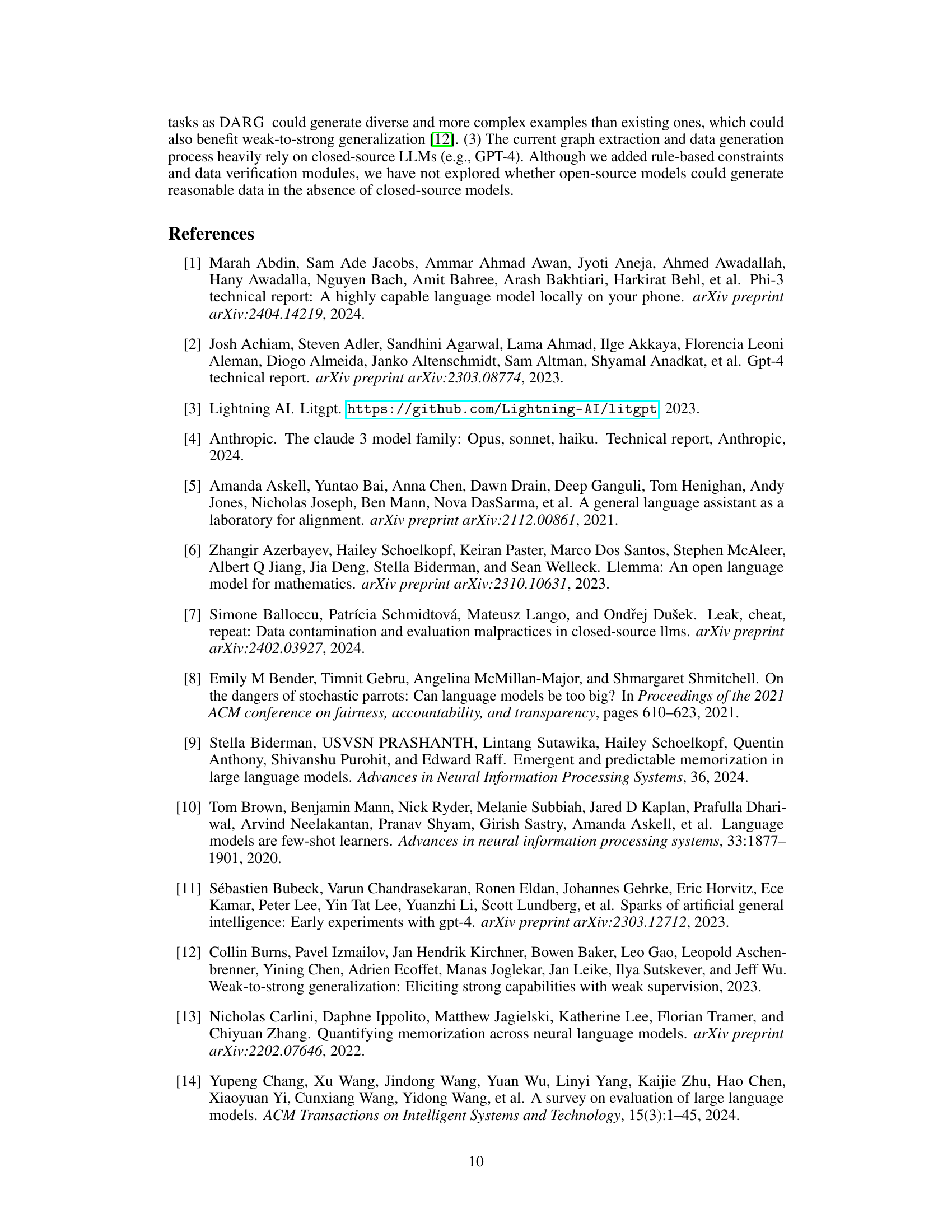

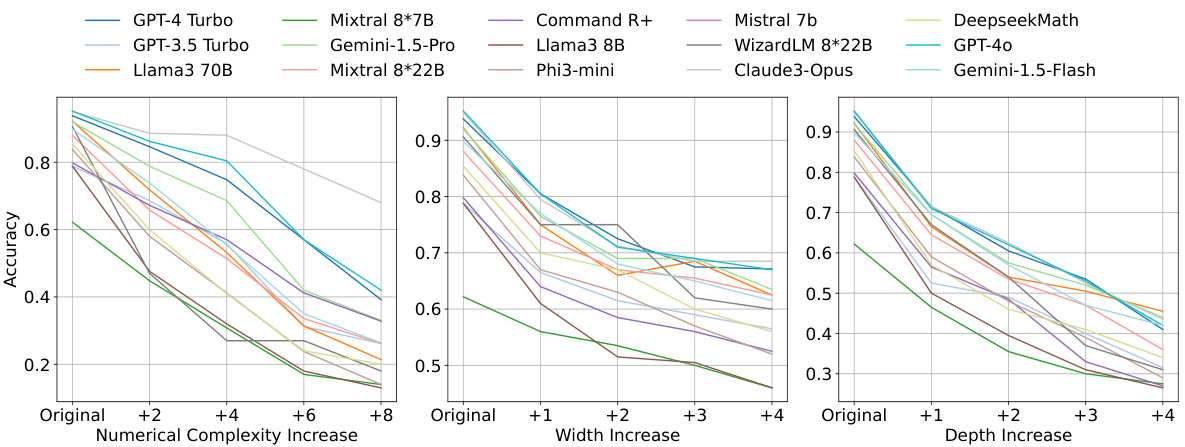

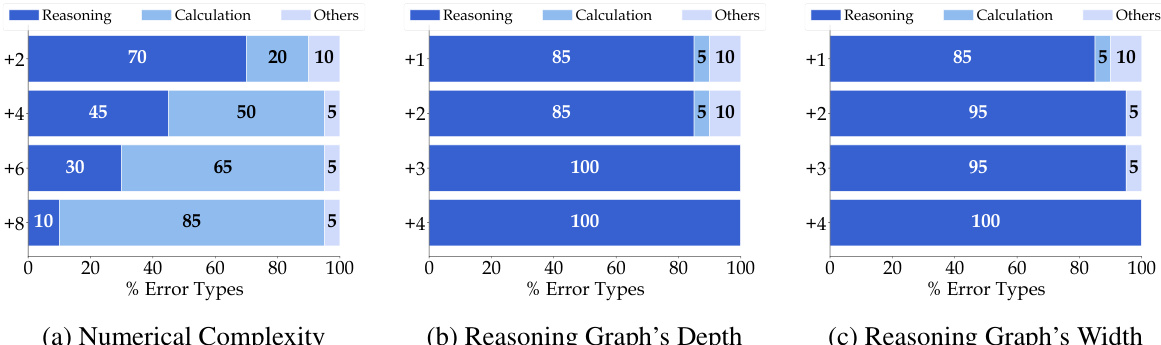

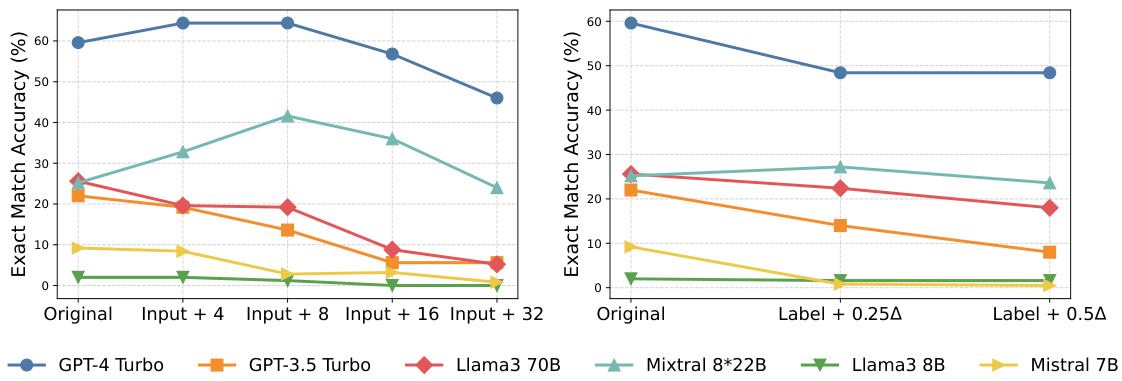

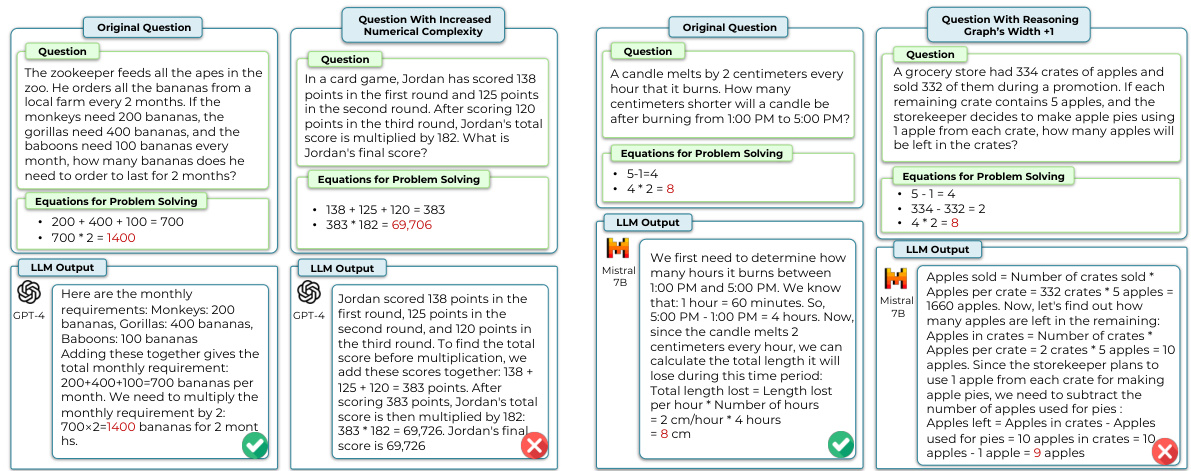

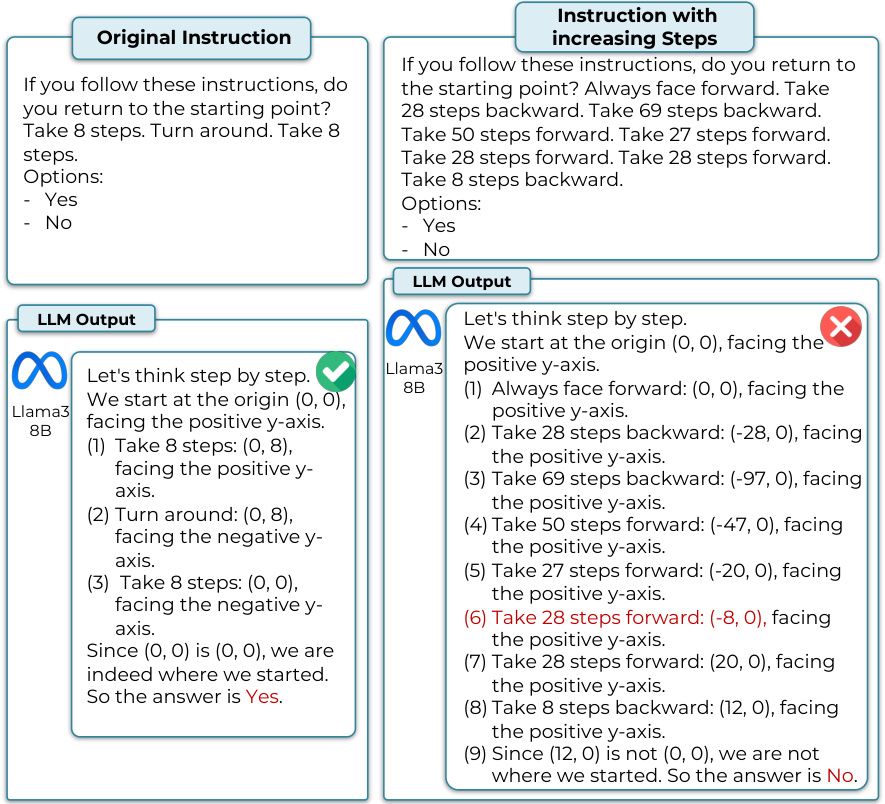

This figure displays the performance of fifteen different Large Language Models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark dataset as the complexity of the reasoning graph increases along three dimensions: numerical complexity, graph width, and graph depth. Each dimension’s complexity is increased incrementally, showing how the accuracy of each LLM changes as the complexity of the tasks increases. This illustrates the impact of increasing task complexity on the models’ performance.

This figure shows how the accuracy of 15 different Large Language Models (LLMs) changes as the complexity of the GSM8K benchmark dataset increases. The complexity is increased along three dimensions: numerical complexity (increased difficulty of the calculations), width (more parallel reasoning steps required), and depth (more sequential steps). The graph demonstrates that in nearly all cases, accuracy decreases as the complexity increases across all three dimensions. The extent of the accuracy drop varies across different LLMs, highlighting the varying robustness of different models to increased complexity.

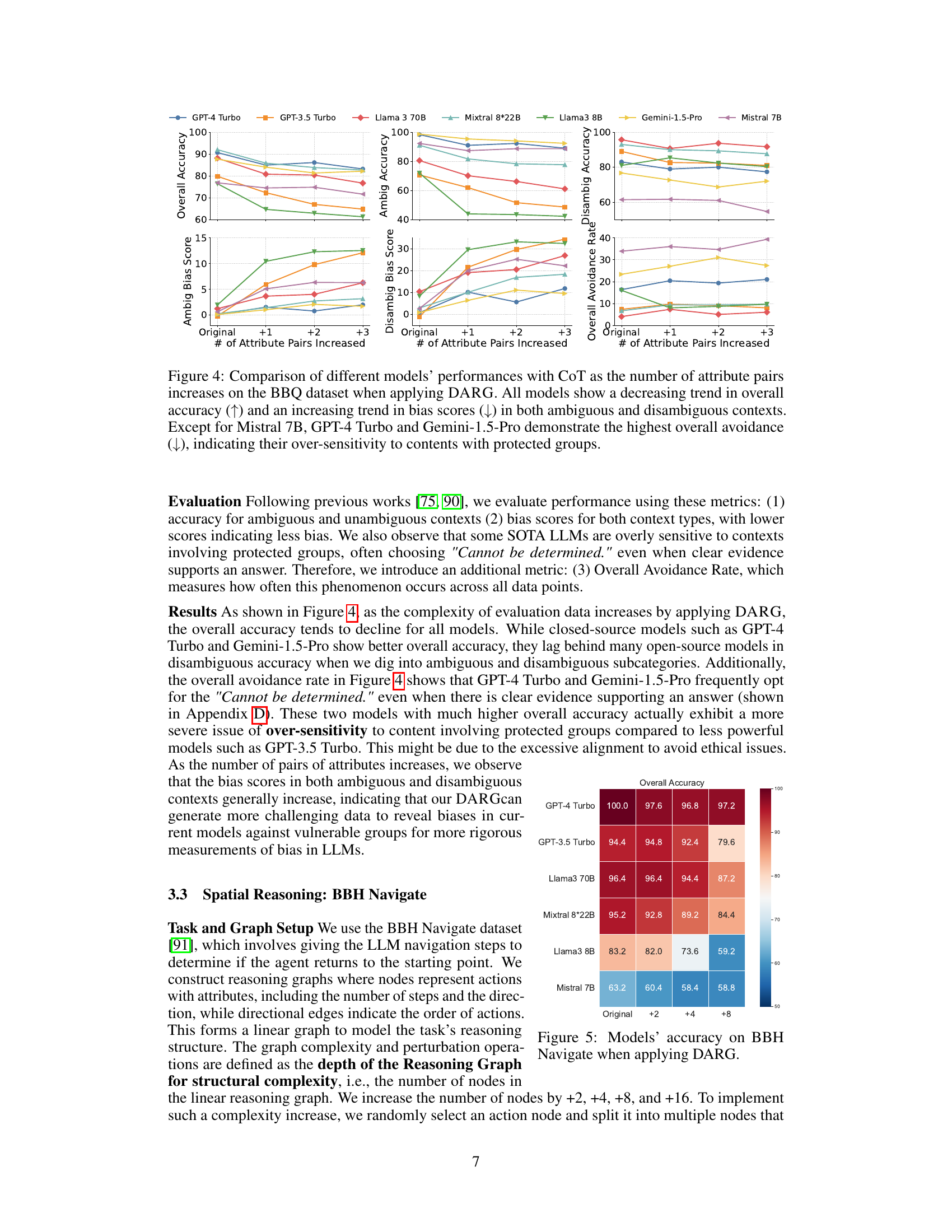

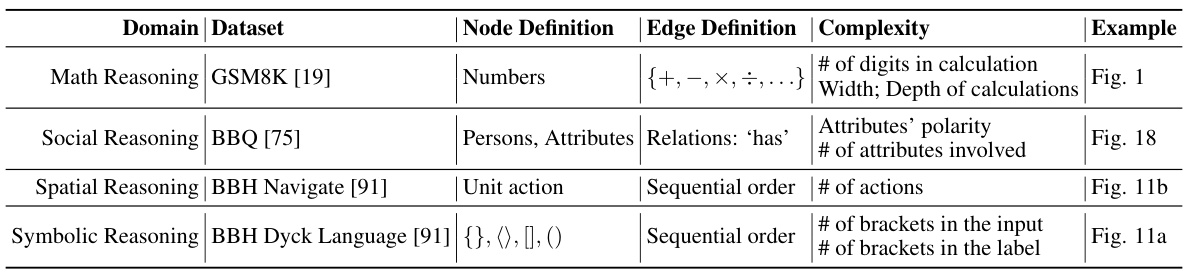

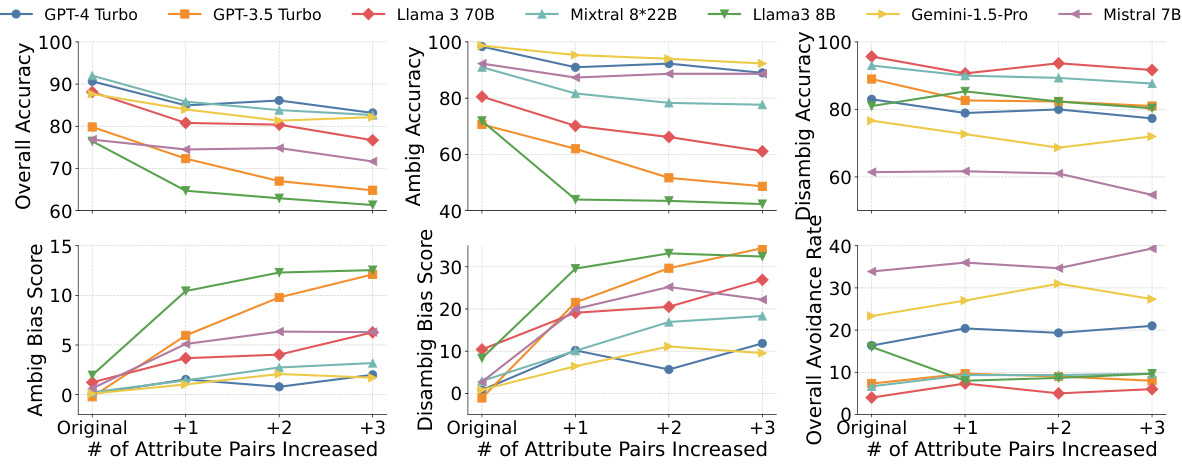

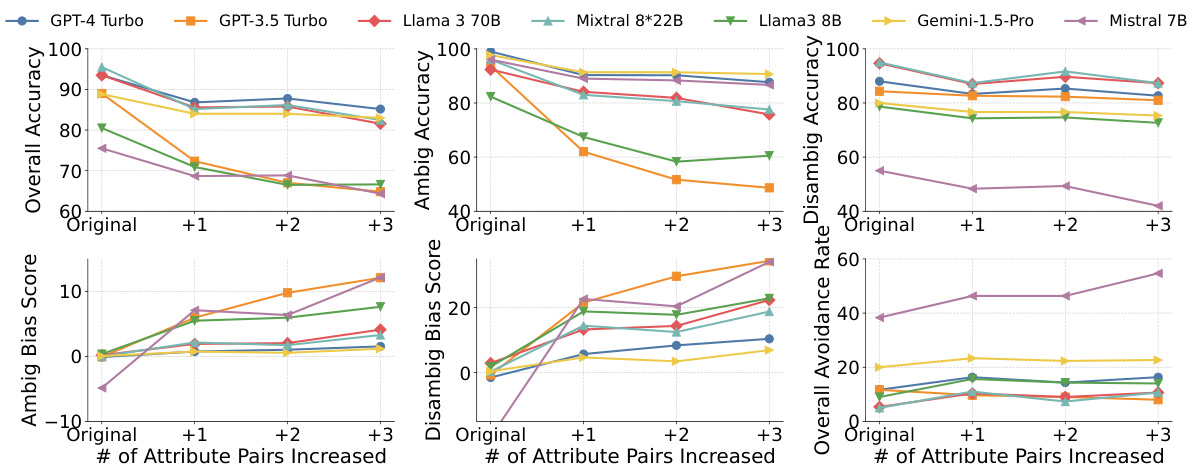

This figure displays the performance of various LLMs on the Bias Benchmark for QA (BBQ) dataset as the number of attribute pairs increases, using Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting and the DARG framework. The results demonstrate a consistent decrease in overall accuracy and an increase in bias scores across all models as complexity grows. LLMs with higher overall avoidance rates (indicating a tendency to avoid answering when unsure) also show higher oversensitivity to content involving protected groups.

This figure displays the performance changes of fifteen different Large Language Models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark dataset as the complexity of the reasoning graph increases along three dimensions: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. Each bar represents the accuracy of a specific LLM on the GSM8K dataset under a specific complexity level. The x-axis shows the increase in complexity level, while the y-axis shows the accuracy. The figure allows for a comparison of how different LLMs handle increasing complexity and the relative impact of each complexity dimension on model performance.

This figure shows the performance change of 15 different Large Language Models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark dataset as the complexity of the reasoning graph increases. The complexity is increased along three dimensions: numerical complexity, width increase, and depth increase. The graph illustrates how the accuracy of each LLM changes as the complexity increases for each of the three dimensions. It helps to visualize the impact of increased complexity on the performance of various LLMs and allows for a comparison of their robustness to increasing complexity.

This figure displays the performance changes of fifteen Large Language Models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark dataset as the complexity of the reasoning graph increases across three dimensions: numerical complexity, graph width, and graph depth. Each bar represents an LLM’s accuracy on the task. The x-axis shows the level of complexity increase (e.g., ‘Original’, ‘+2’, ‘+4’ etc. indicating an increase in the complexity parameter). The y-axis shows the accuracy scores. The figure demonstrates how the performance of different LLMs varies with respect to increased complexity levels across different dimensions, highlighting LLMs’ robustness to the growing complexity of reasoning tasks.

This figure displays the performance of fifteen different Large Language Models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark dataset as the complexity of the reasoning graph increases. The complexity is manipulated along three different dimensions: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. Each dimension is varied incrementally, allowing observation of how LLM performance changes as complexity rises. The x-axis represents the increased complexity level for each dimension, and the y-axis shows the accuracy of the LLMs. The figure allows for a comparison of the performance of various LLMs across different complexity levels and dimensions, helping to understand the models’ robustness and limitations under different types of reasoning challenges.

This figure displays the performance of fifteen different large language models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark dataset as the complexity of the reasoning graphs increases across three dimensions: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. Each dimension’s complexity is incrementally increased, allowing for observation of how the LLMs’ accuracy changes. The graph provides insights into the robustness and limitations of various LLMs when confronted with increasingly complex reasoning tasks. It helps understand how different models perform in relation to the increasing complexity, shedding light on model capabilities and potential biases.

This figure shows the performance of several LLMs on the BBQ dataset under different complexity levels. The x-axis represents the number of attribute pairs increased when applying the DARG method. The y-axis displays the overall accuracy, bias scores, and overall avoidance rates for both ambiguous and unambiguous contexts. The results indicate that most models show decreasing accuracy and increasing bias scores as complexity increases. GPT-4 Turbo and Gemini-1.5-Pro exhibit a higher avoidance rate, suggesting potential oversensitivity to content involving protected groups.

This figure illustrates the DARG framework’s workflow. It starts by constructing reasoning graphs from existing benchmark data using an LLM. These graphs are then perturbed to increase complexity (depth, width, numerical complexity) and transformed back into text format. A code-augmented LLM verifies the label correctness of the new data points, ensuring the accuracy of the newly generated, more complex data.

This figure shows the performance change of 15 different LLMs on the GSM8K benchmark as the complexity of the reasoning graph increases. The complexity is increased along three dimensions: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. Each bar in the chart represents the accuracy of a given LLM on the GSM8K dataset at a specific complexity level. The figure demonstrates that, as complexity increases along any of these dimensions, almost all of the evaluated LLMs experience a performance decrease. This suggests that the current performance of LLMs on static benchmarks may not accurately reflect their capabilities in complex reasoning tasks.

This figure shows the performance change of fifteen large language models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark dataset as the complexity of the reasoning graphs increases across three dimensions: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. Each bar represents the accuracy of a specific LLM on the GSM8K dataset for a given complexity level. The x-axis represents the increase in complexity level for each dimension, while the y-axis represents the accuracy. The figure helps to visualize how the performance of different LLMs varies with increasing complexity in different aspects of reasoning.

This figure presents the performance changes of fifteen large language models (LLMs) on the GSM8K dataset as the complexity of the reasoning graph increases along three dimensions: numerical complexity, graph width, and graph depth. Each dimension represents a different way of increasing the difficulty of the problem. The x-axis represents the level of complexity increase for each dimension, and the y-axis represents the accuracy of the LLMs. The figure helps to illustrate how increases in complexity, across various dimensions, affect the performance of different LLMs, revealing varying degrees of robustness.

This figure shows how the performance of 15 different large language models (LLMs) changes on the GSM8K benchmark dataset as the complexity of the reasoning graph increases along three different dimensions: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. Each dimension’s complexity is increased incrementally, showing the performance drop in each LLM as the task becomes more challenging. The figure provides insights into the robustness and limitations of various LLMs when faced with increasingly complex reasoning tasks.

This figure illustrates the DARG framework’s three main stages. First, it shows how an LLM constructs internal reasoning graphs for benchmark data points, using rule-based methods to ensure label consistency. Second, it details how these graphs are manipulated through fine-grained interpolation to introduce controlled complexity variations. Finally, it explains how the modified graphs are converted back into a usable format and then verified using a code-augmented LLM agent to guarantee label accuracy.

This figure illustrates the DARG framework’s three main steps. First, it uses an LLM to generate internal reasoning graphs for the benchmark’s data points. Second, it perturbs these graphs to introduce controlled complexity variations. Finally, it uses a code-augmented LLM to validate the labels of the newly generated data points. This process dynamically extends the benchmark dataset with varied complexities while maintaining linguistic diversity.

This figure presents a schematic overview of the DARG framework, illustrating its three main stages: reasoning graph construction, graph interpolation, and new data point verification. In the first stage, an LLM constructs an internal reasoning graph, which is checked for label consistency via rule-based verification. The second stage involves augmenting the benchmarks through graph interpolation, modifying the graph’s structure to control complexity. The third stage decodes the modified graph back to the original format and uses a code-augmented LLM agent to verify its correctness. Each stage is visually represented, detailing the input, processing steps, and output.

More on tables

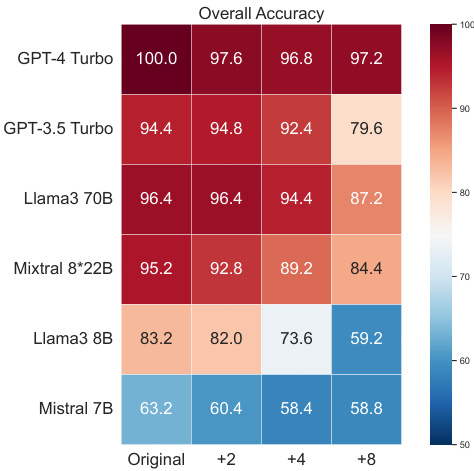

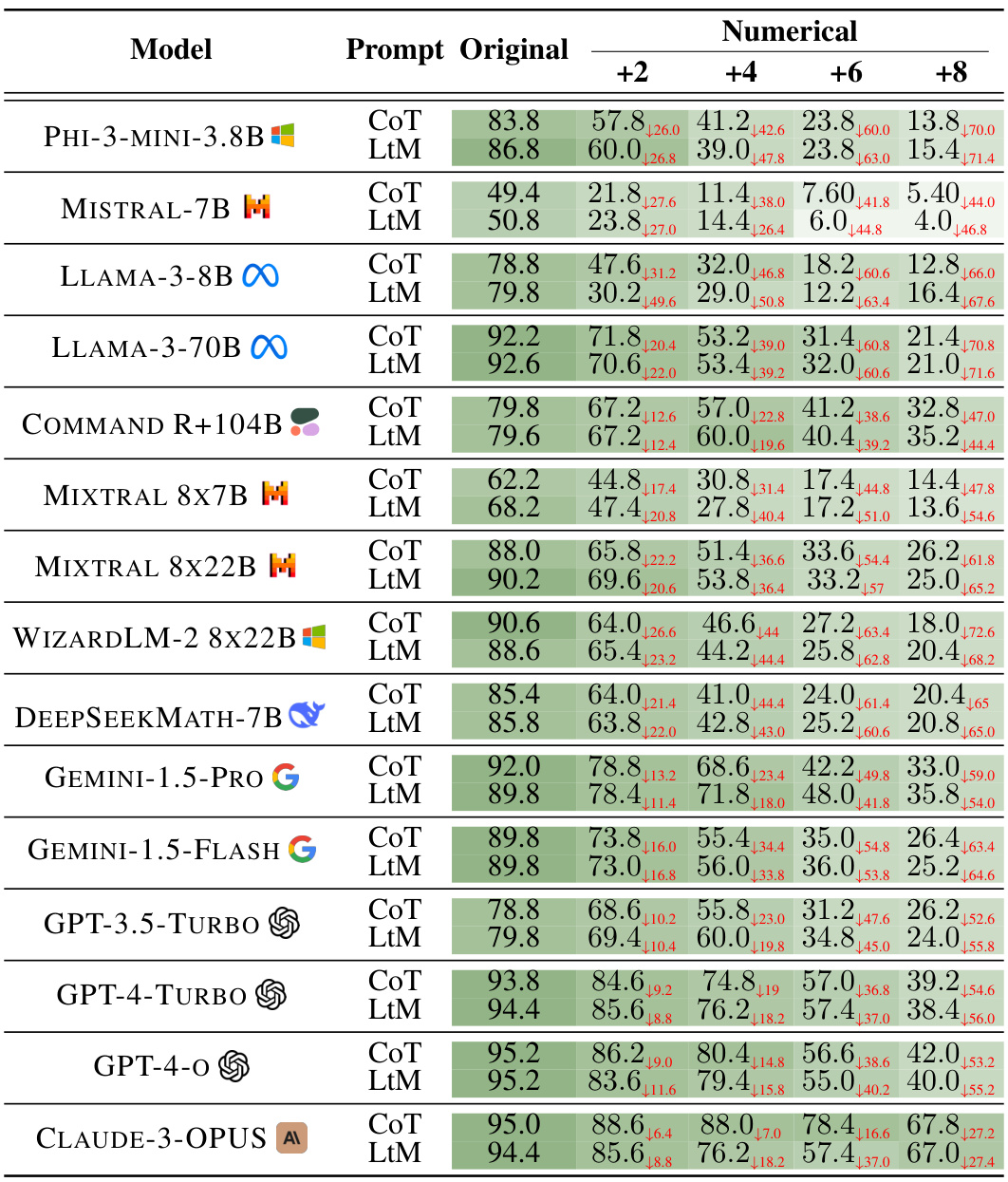

This table presents the overall accuracy of 15 Large Language Models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark when using Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting. The accuracy is measured across three different complexity dimensions manipulated by the DARG framework: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. Each complexity dimension has four levels, starting from the original complexity of the dataset. The table shows how the accuracy of each LLM changes across these complexity levels for each of the dimensions. For full results including the detailed breakdown of accuracy changes across each complexity level, it refers the reader to Figures 3, 4 and 5.

This table presents the overall accuracy scores achieved by 15 different Large Language Models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark when evaluated using Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting. The models’ performance is assessed under three different complexity dimensions manipulated by the DARG framework: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. Each dimension is tested at four levels, including the original complexity and three increased complexity levels (+2, +4, +8 for numerical complexity, and +1, +2, +3, +4 for graph width and depth). The full results for each of the three complexity dimensions are shown in Figures 3, 4, and 5 of the paper.

This table shows the accuracy of 15 different Large Language Models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark when using Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting. The accuracy is measured across three different complexity dimensions manipulated by the DARG framework: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. Each dimension has four levels of increasing complexity. The full results for each LLM and complexity level can be found in Figures 3, 4, and 5 of the paper.

This table shows the accuracy of 15 different large language models (LLMs) on the GSM8K benchmark when evaluated using Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting and the DARG method. DARG introduces controlled complexity variations in three dimensions: numerical complexity, graph depth, and graph width. The table presents the accuracy of each LLM on the original GSM8K dataset and at different complexity levels for each dimension. Full results (including CIARR and error breakdowns) are shown in Figures 3, 4, and 5 of the paper.

This table shows the accuracy of 15 different large language models (LLMs) on the GSM8K dataset when using Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting. The models are evaluated under three different complexity dimensions modified by the DARG framework. The table presents the accuracy for the original GSM8K dataset and three levels of increased complexity for each dimension. More detailed results for each LLM and complexity level can be found in Figures 3, 4, and 5 of the paper.

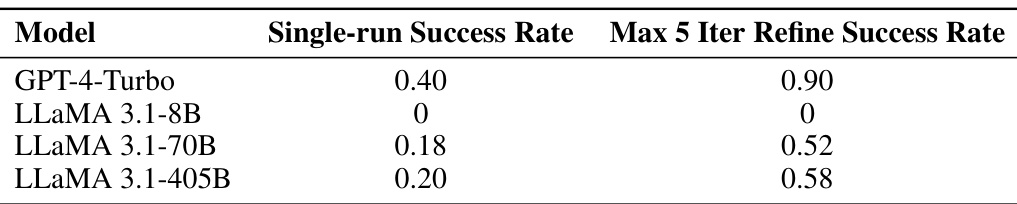

This table presents the success rates achieved by four different language models in the task of extracting reasoning graphs from a dataset. The models are GPT-4-Turbo, LLaMA 3.1-8B, LLaMA 3.1-70B, and LLaMA 3.1-405B. The success rate represents the proportion of times the model successfully extracted a reasoning graph. The table shows that GPT-4-Turbo has a high success rate (0.91), while the smaller LLaMA model (LLaMA 3.1-8B) has a success rate of 0. The larger LLaMA models have moderate success rates (0.83 and 0.85).

This table presents the success rates of graph-to-text decoding for four different language models. The models are evaluated under two conditions: a single run, and a maximum of 5 iterative refinement steps. The table shows that the success rate increases significantly with the iterative refinement. GPT-4-Turbo shows the best results, while LLaMA 3.1-8B struggles to produce any successful decodings.

Full paper#