TL;DR#

Program synthesis, the automatic generation of programs, faces challenges. Purely neural methods like Large Language Models (LLMs) struggle with complex problems and unfamiliar languages, while purely symbolic methods scale poorly. This research introduces HYSYNTH, a hybrid approach to bridge this gap. It leverages LLMs’ power to generate programs but addresses their shortcomings by using them to learn simpler, context-free models to guide a more efficient search for solutions. This method tackles limitations of both neural and symbolic approaches.

HYSYNTH, tested on three domains (grid-based puzzles, tensor manipulation, string manipulation), demonstrates improved performance over existing methods. It outperforms both unguided search and direct LLM sampling. The use of a context-free surrogate model makes HYSYNTH compatible with efficient bottom-up search, a key advantage over other hybrid methods. The successful generalization across diverse tasks highlights its potential for broader applications in program synthesis.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in program synthesis and machine learning. It presents a novel hybrid approach that effectively combines the strengths of large language models (LLMs) and efficient search techniques, offering a significant advancement in program synthesis. The approach’s ability to generalize across different domains and handle complex problems, overcoming the limitations of purely neural or symbolic methods, is especially impactful. By using LLMs to guide search, it shows a path to building more efficient and robust program synthesizers, which opens up exciting avenues for future research in automated programming, AI, and software engineering.

Visual Insights#

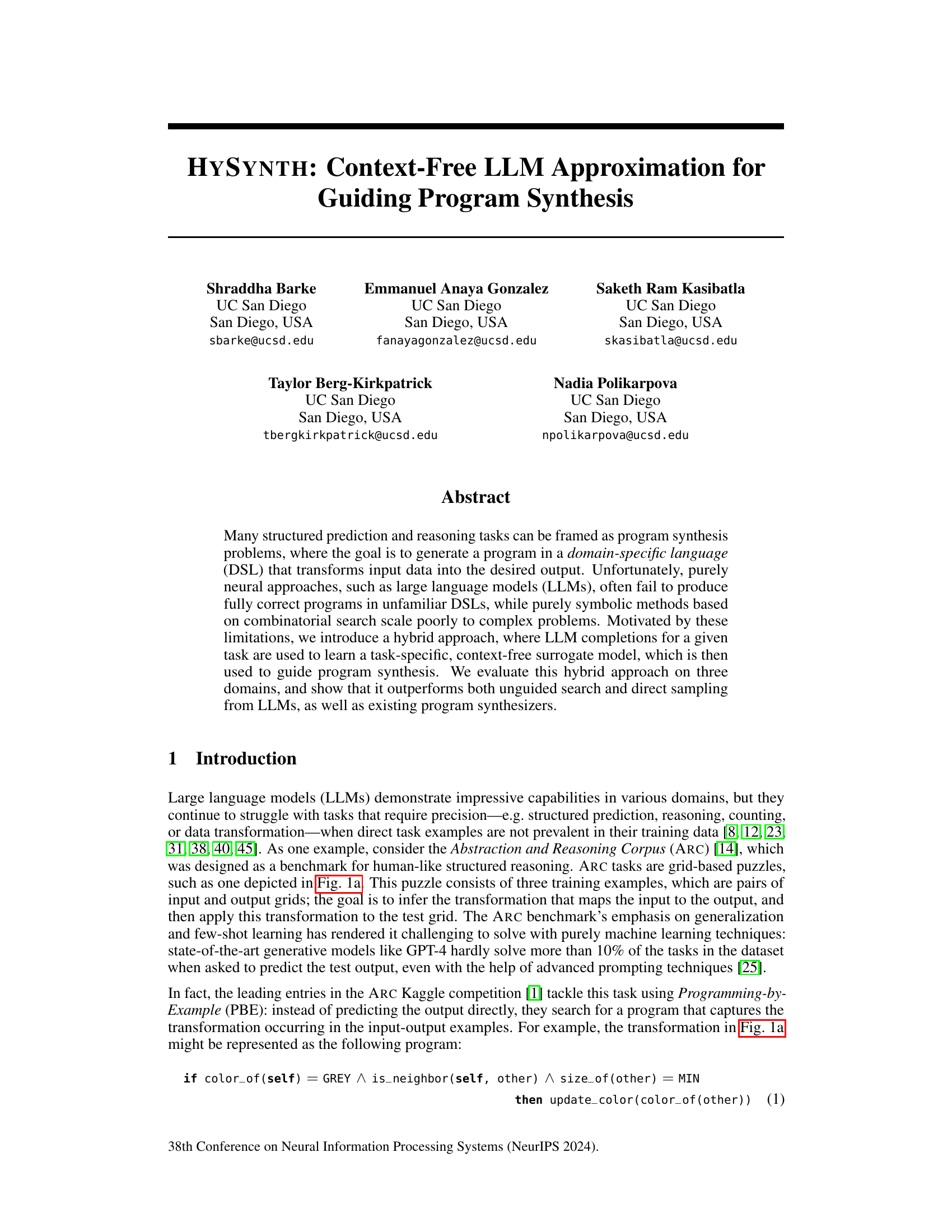

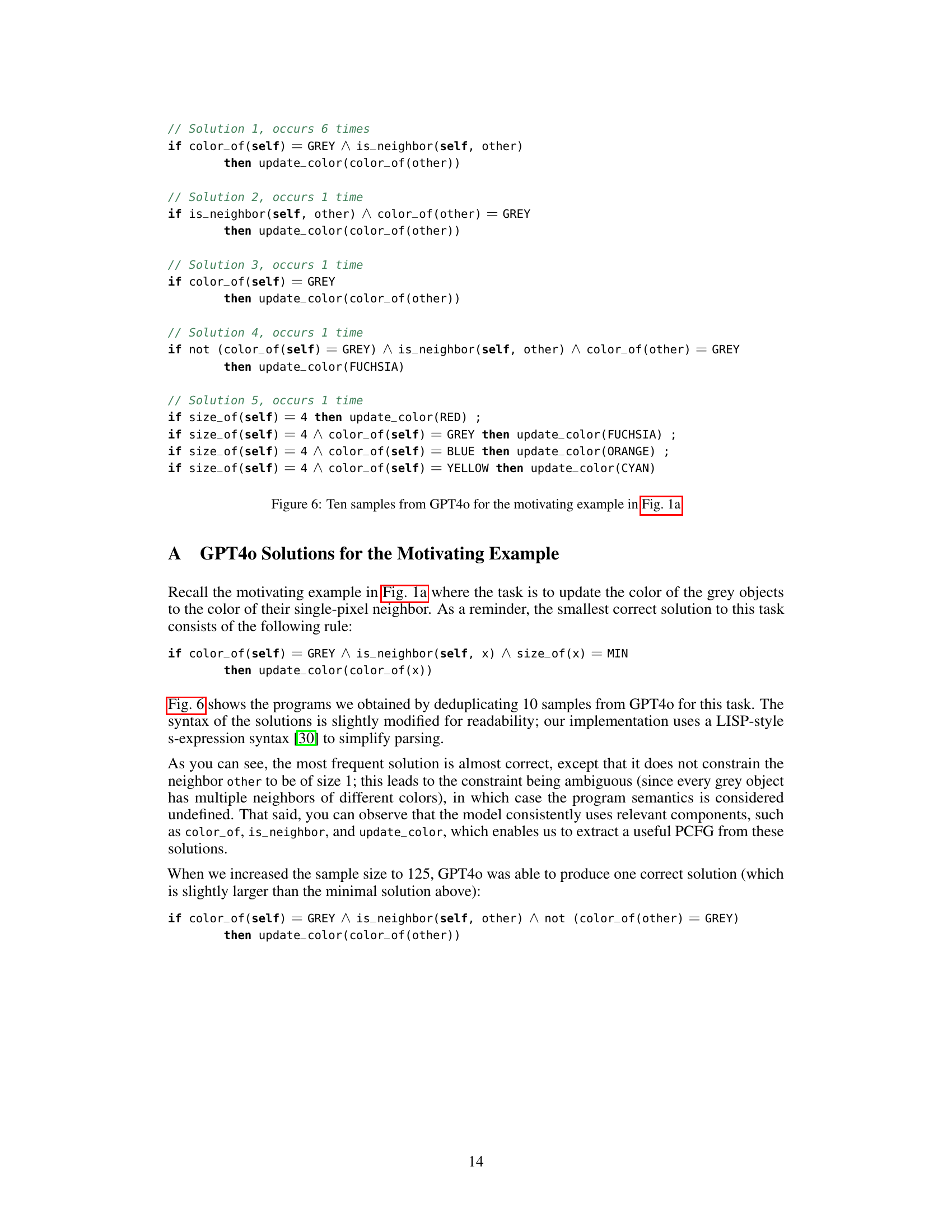

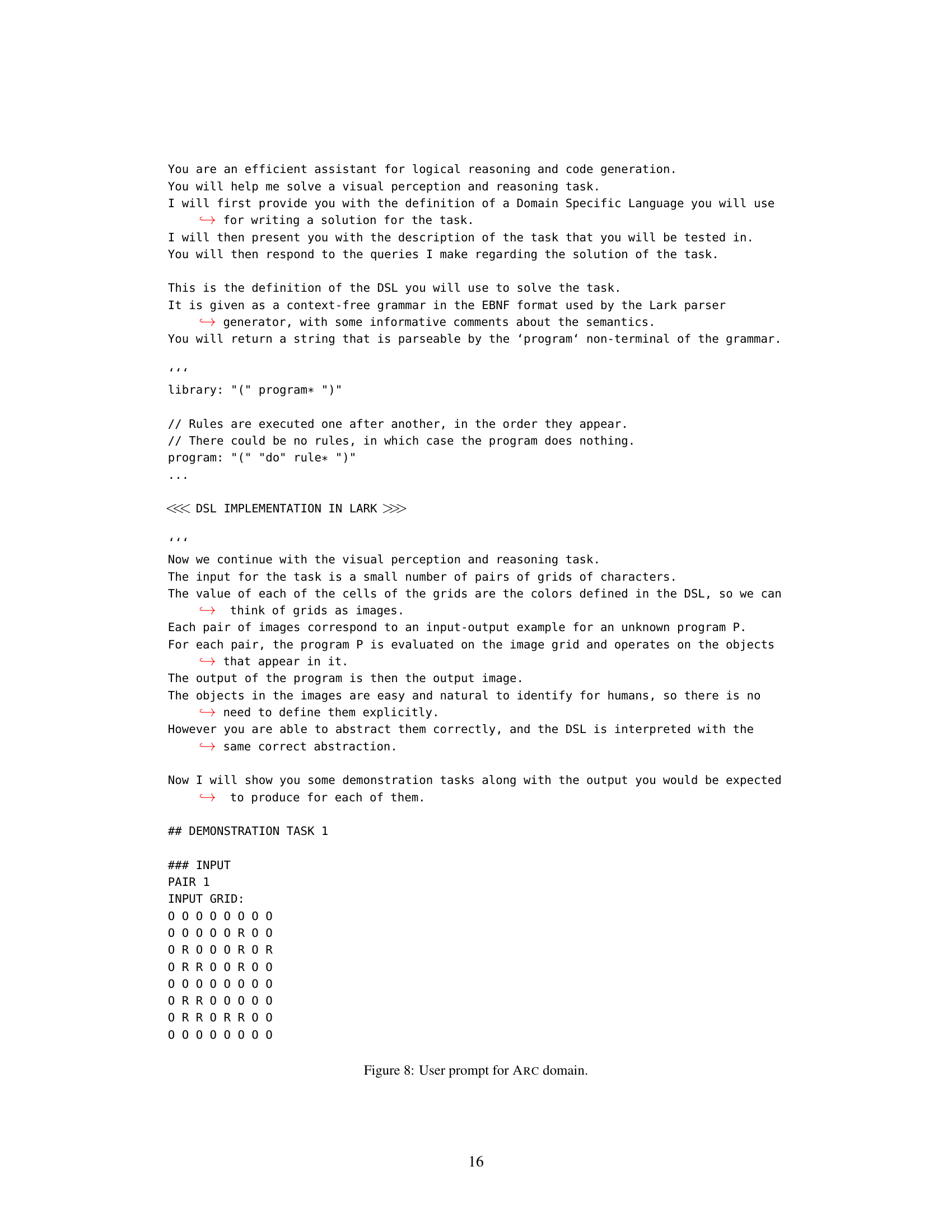

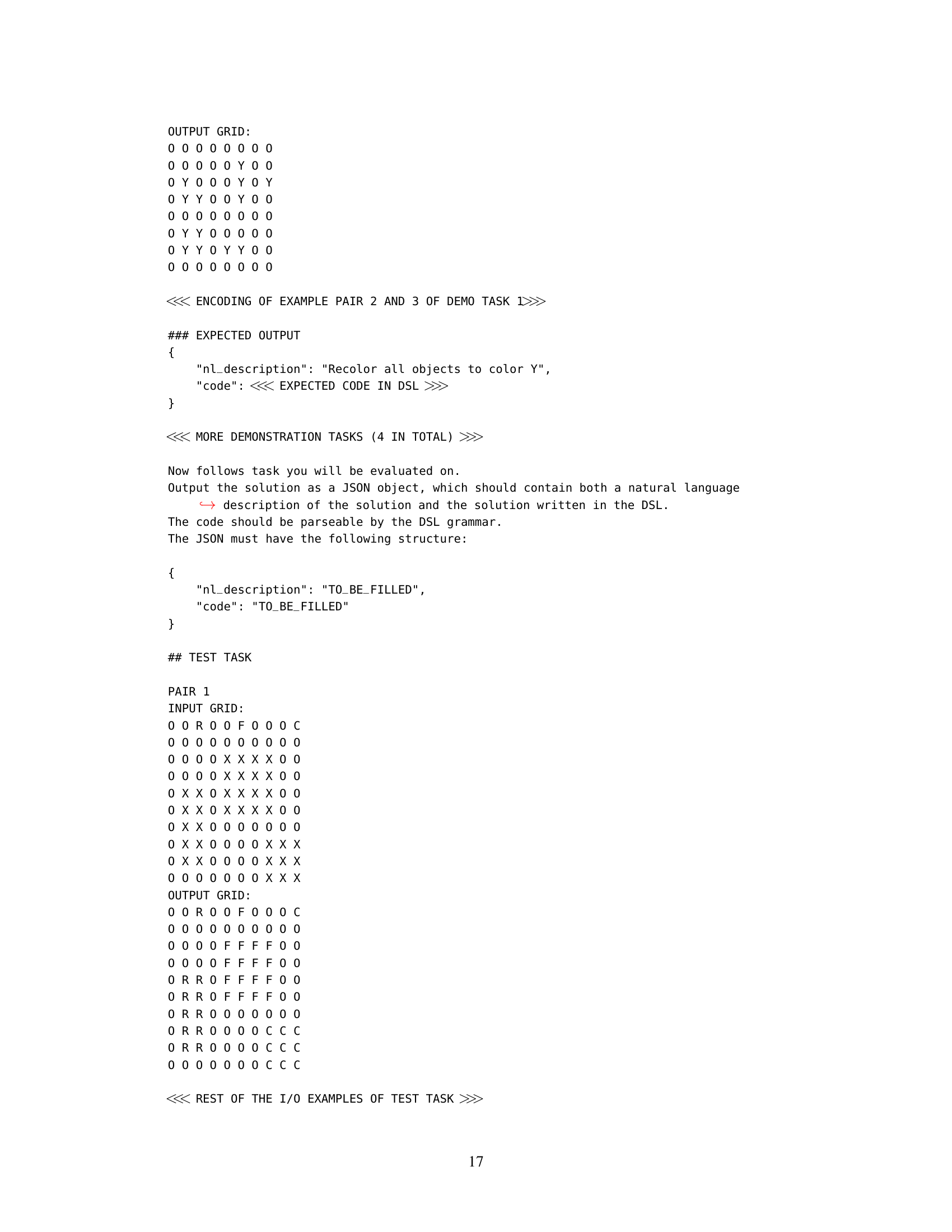

🔼 This figure shows three example problems from the three program-by-example (PBE) domains used to evaluate the HYSYNTH program synthesis approach. (a) shows an example of a grid-based puzzle from the Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC). The task is to identify the transformation rule that maps input grids to output grids and apply it to a test grid. (b) shows an example of tensor manipulation problem. The task is to generate a program that transforms input tensor into the desired output tensor using Tensorflow operators. (c) shows an example of a string manipulation problem. The task is to create a program to transform an input string into the desired output string.

read the caption

Figure 1: Example problems from the three PBE domains we evaluate HYSYNTH on: grid-based puzzles (ARC), tensor manipulation (TENSOR), and string manipulation (STRING).

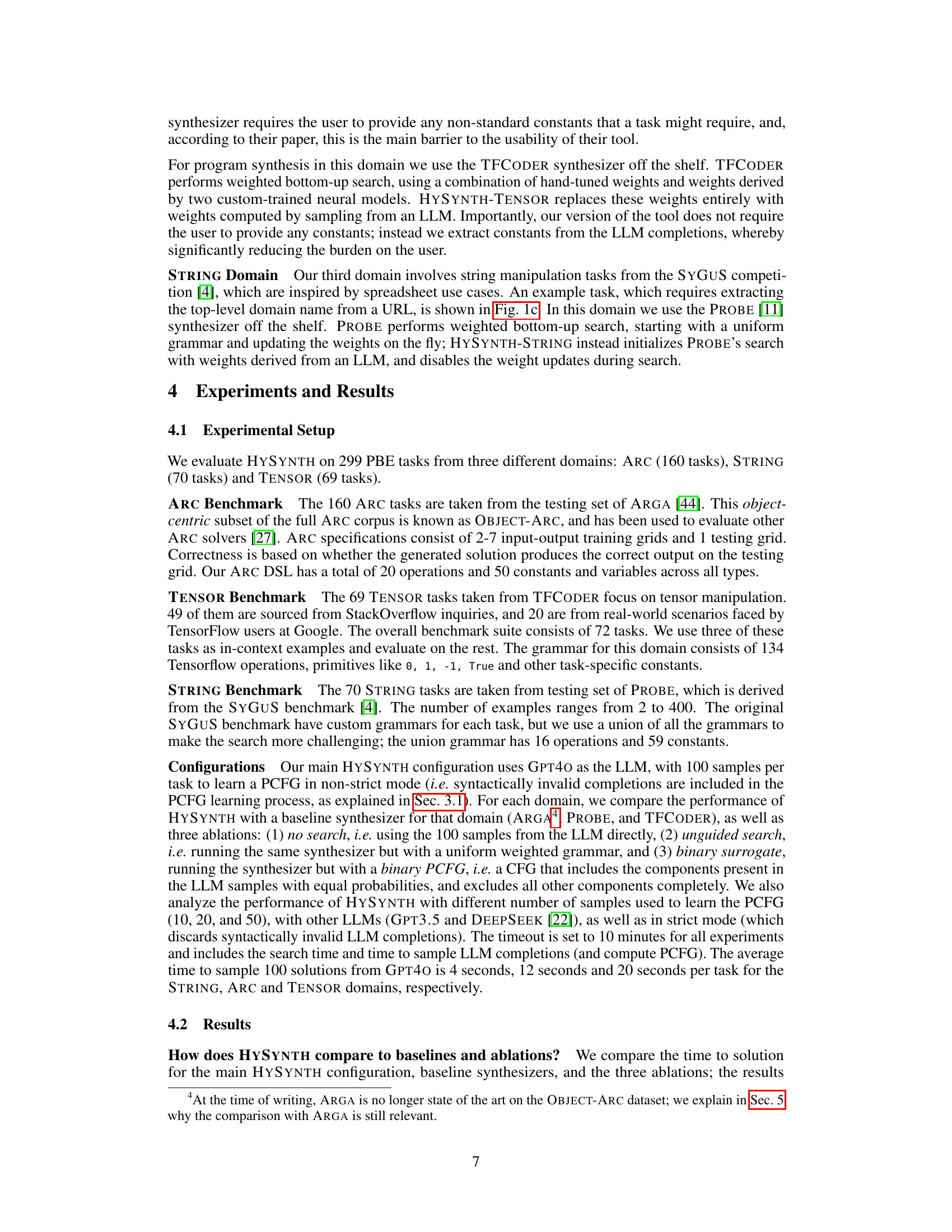

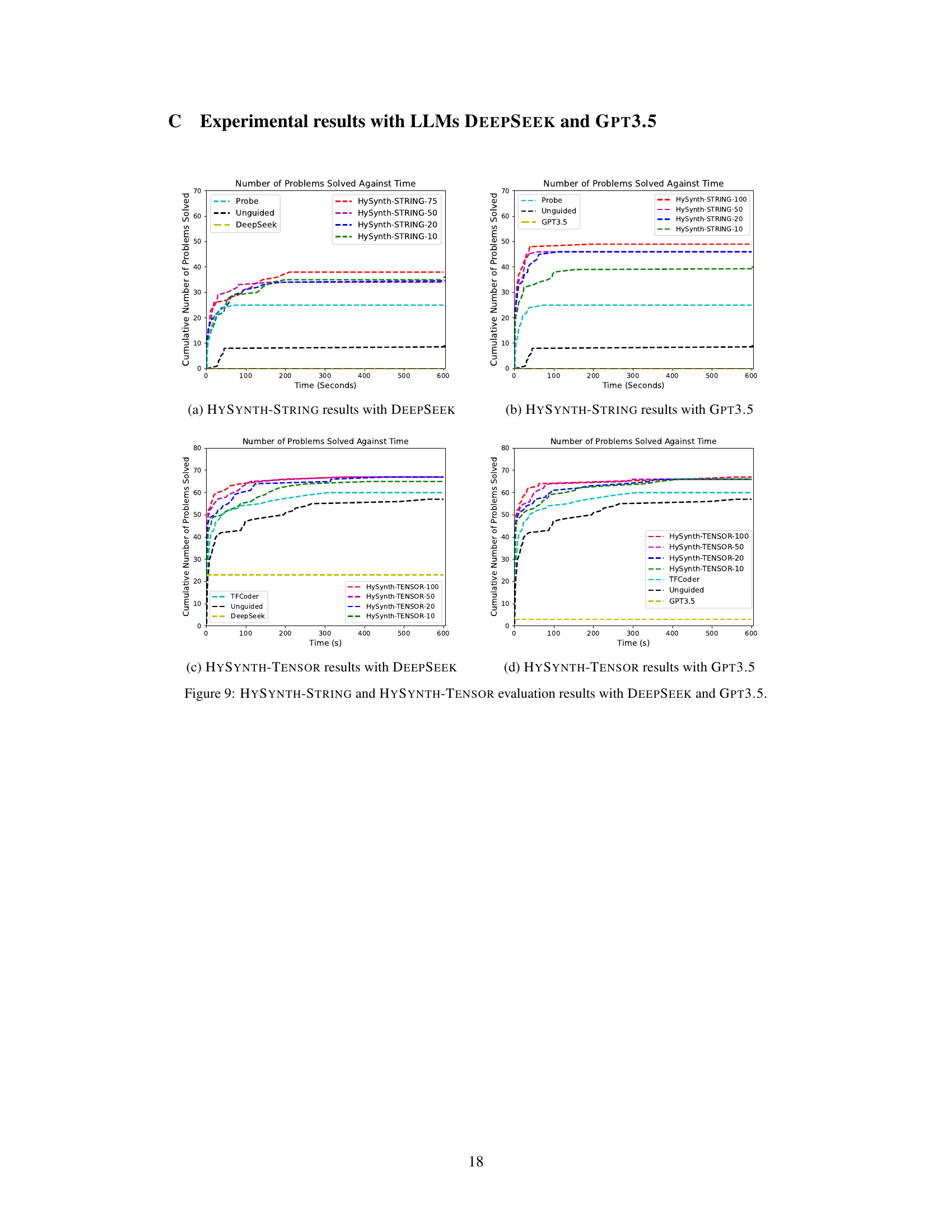

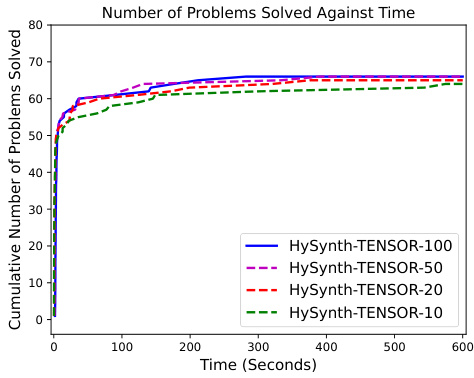

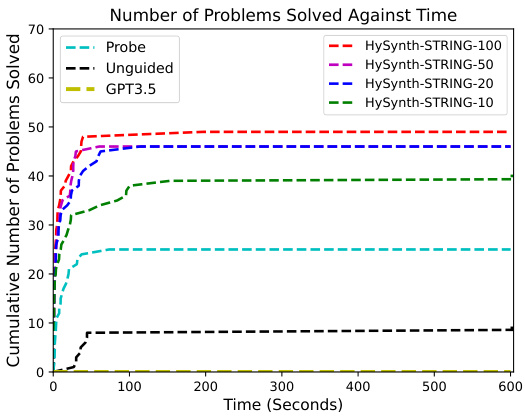

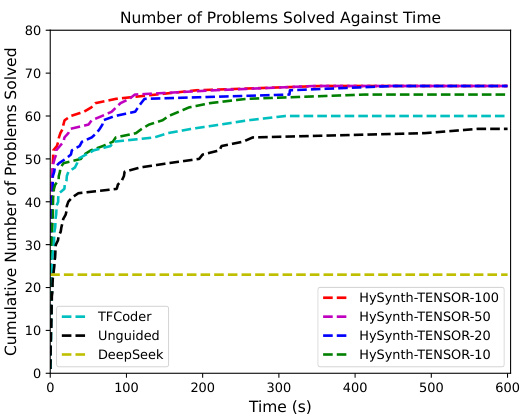

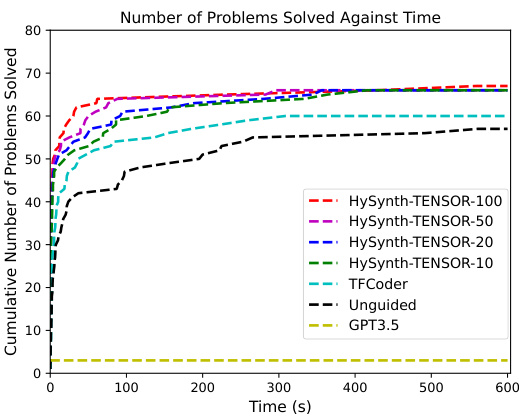

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the performance of HYSYNTH against other methods across three different domains: ARC, TENSOR, and STRING. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show cumulative problem-solving counts over time for each domain, highlighting HYSYNTH’s superior performance compared to baselines. Subfigure (d) shows the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by LLMs in each domain.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

In-depth insights#

LLM-PBE Hybrid#

LLM-PBE hybrid approaches represent a significant advancement in program synthesis, aiming to leverage the strengths of both large language models (LLMs) and the precision of program-by-example (PBE) techniques. LLMs excel at generating diverse program candidates, offering a breadth of potential solutions that traditional search-based methods may miss. However, LLMs often lack the precision required for complex DSLs, frequently producing incorrect or incomplete code. PBE methods, conversely, provide a structured approach that guarantees correctness, but can be computationally expensive and limited in their ability to explore the vast space of possible programs. A hybrid approach synergistically combines these, using the LLM to efficiently generate a set of candidate solutions and then using PBE techniques to refine and validate those candidates, optimizing for both efficiency and accuracy. The key challenge lies in effectively bridging the gap between the LLMs’ probabilistic nature and the deterministic constraints of PBE. This requires careful consideration of how to use the LLM’s outputs, such as learning a surrogate model to guide search or employing a probabilistic model to rank candidate programs, maximizing the advantages of both while minimizing their respective shortcomings.

PCFG Surrogate#

The concept of a “PCFG Surrogate” in the context of program synthesis using large language models (LLMs) is a clever approach to bridge the gap between the power of LLMs and the efficiency of traditional symbolic methods. The core idea is to approximate the complex probabilistic distribution of LLM-generated programs with a simpler, more tractable probabilistic context-free grammar (PCFG). This surrogate model, trained on LLM outputs, captures essential structural information about valid programs in a specific domain-specific language (DSL). By using this PCFG surrogate, the search for the correct program becomes computationally feasible. The context-free nature of the PCFG is particularly important, as it’s compatible with efficient bottom-up search algorithms. These algorithms leverage the inherent structure of the PCFG to effectively explore the program space, avoiding the combinatorial explosion that often plagues purely symbolic program synthesis. This hybrid approach cleverly combines the strengths of LLMs (generating diverse program candidates) with the efficiency of PCFGs and bottom-up search (finding the optimal solution within a manageable search space). However, the accuracy of this approximation depends heavily on the quality and quantity of LLM-generated programs used for training, and also its applicability might be limited to DSLs with a manageable complexity and well-defined structural properties.

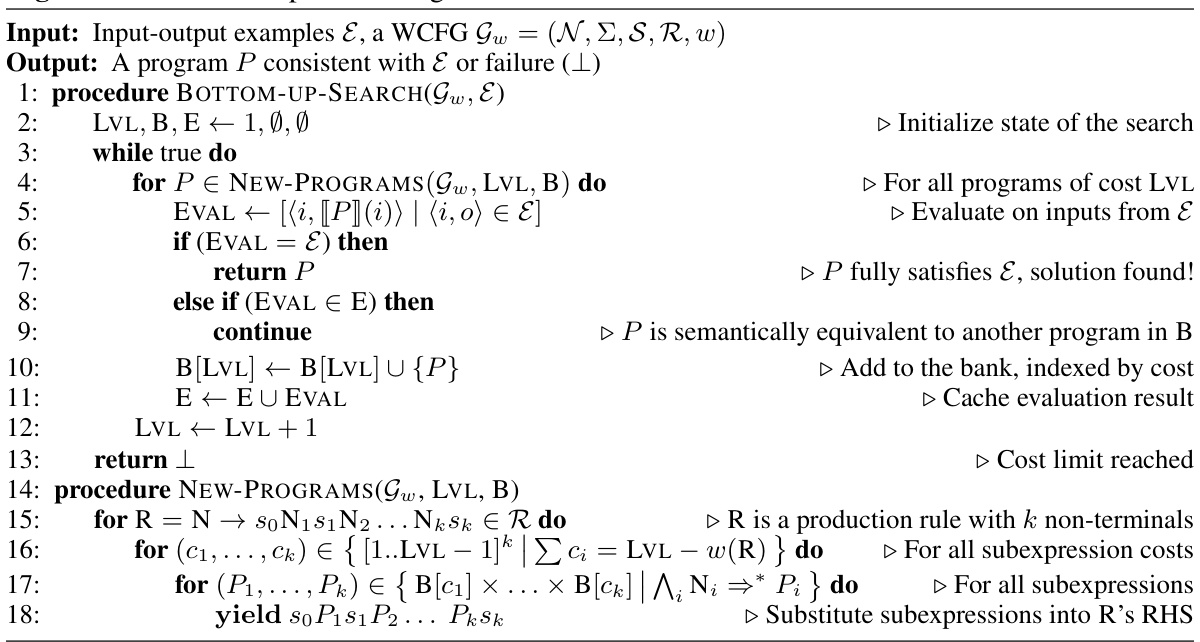

Bottom-Up Search#

Bottom-up search, a dynamic programming technique in program synthesis, constructs programs incrementally, starting with smaller sub-programs and combining them using production rules. It maintains a program bank, indexing programs by cost, to efficiently reuse and combine simpler programs. This avoids redundant computation, crucial for large search spaces. The algorithm’s efficiency hinges on cost-based enumeration and the evaluation of programs against input-output examples, discarding those observationally equivalent to existing ones. This factorization of the search space reduces redundancy and makes it suitable for use with probabilistic models, unlike top-down approaches. The efficiency of bottom-up search makes it a powerful technique when combined with LLMs. The synergy of its deterministic nature with the probabilistic guidance from the LLM model proves especially effective in handling complex program synthesis problems.

Domain Results#

A dedicated ‘Domain Results’ section would be crucial for a research paper on program synthesis using LLMs. It should present a detailed breakdown of the performance across various domains (e.g., grid-based puzzles, tensor manipulation, string manipulation). Key metrics like success rate, execution time, and the number of programs explored should be reported for each domain, comparing the proposed hybrid approach to baselines (LLMs alone and existing program synthesizers). A thorough analysis should highlight domain-specific challenges and how the proposed method addresses them. For instance, the complexity of the DSL and search space may differ significantly between domains; therefore, the results should demonstrate the hybrid approach’s adaptability and robustness. Visualizations (e.g., graphs showing success rates against time) would significantly enhance the clarity and impact of the analysis, enabling readers to quickly understand the performance differences. Furthermore, the discussion should explain any unexpected or interesting results, emphasizing aspects such as the generalization capabilities of the hybrid model across various domains. The section needs to provide sufficient details to enable reproducibility by describing the data used and the experimental setup within each domain.

Future Works#

Future work in this research could explore several promising directions. Extending the approach to more complex DSLs and problem domains is crucial. The current work focuses on relatively structured tasks; tackling unstructured or less-defined problems would significantly expand the applicability and impact of the method. Improving the efficiency of the surrogate model training is another important area. While the HMM approach provides a good balance between accuracy and efficiency, further optimization could potentially reduce training time and resource consumption, making the system more practical for larger-scale applications. Investigating alternative surrogate models beyond HMMs, such as neural networks or other probabilistic models, could lead to improved accuracy or efficiency. This involves careful consideration of the trade-offs between model complexity and computational cost. Finally, in-depth analysis of the limitations of the LLM approximations is needed. A deeper understanding of the biases and shortcomings of the surrogate model could lead to the development of improved techniques and more reliable results. Addressing these aspects will strengthen the robustness and real-world applicability of this hybrid program synthesis approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

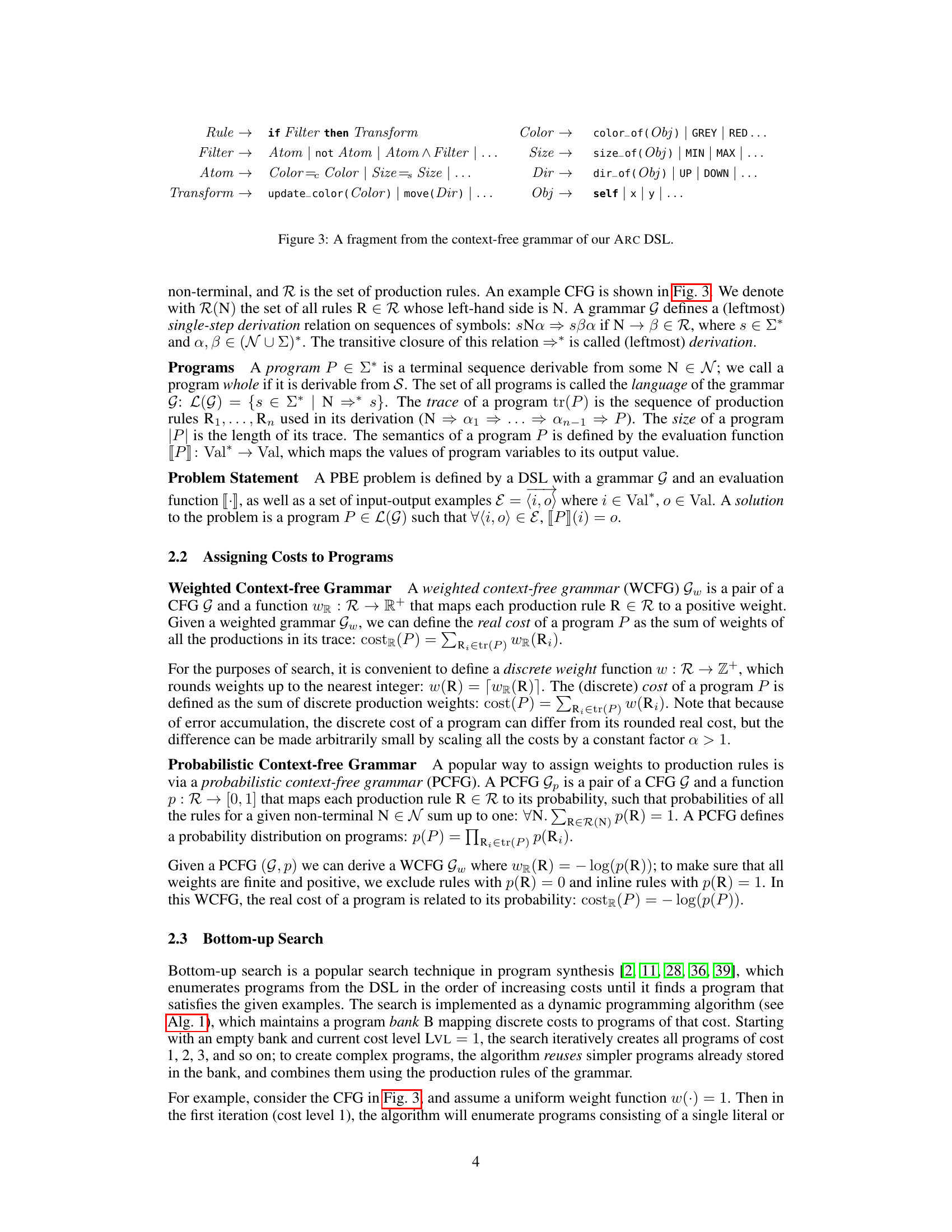

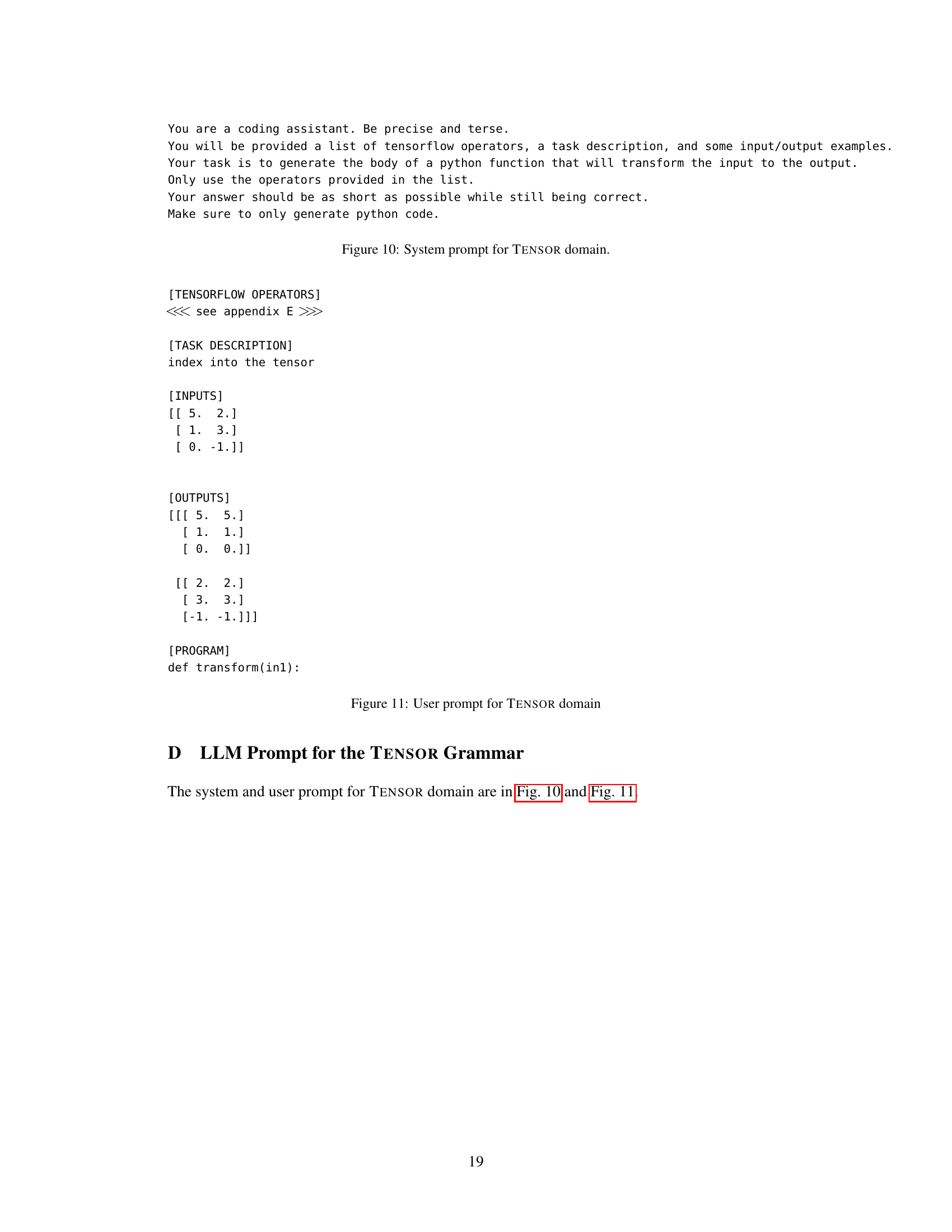

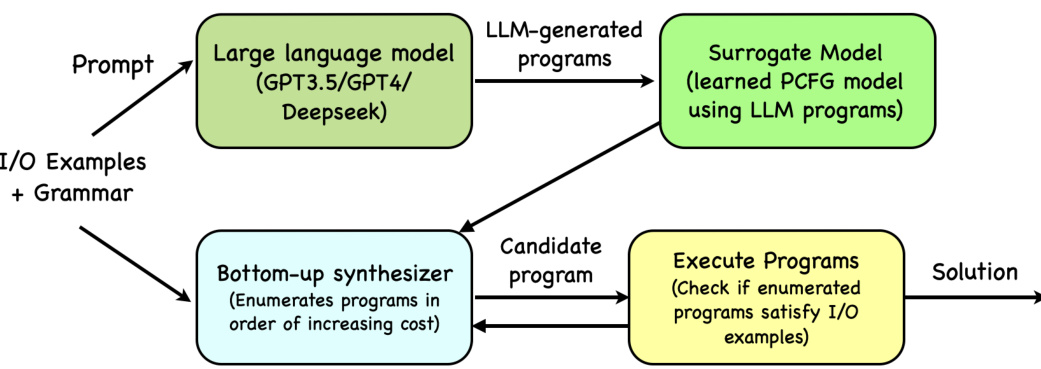

🔼 This figure illustrates the HYSYNTH program synthesis approach. It starts by using an LLM (like GPT-3.5, GPT-4, or DeepSeek) to generate programs given a prompt including input/output examples and a grammar. These LLM-generated programs are then used to train a context-free surrogate model (a probabilistic context-free grammar or PCFG). This PCFG is then used to guide a bottom-up synthesizer, which efficiently explores the program search space by considering programs in increasing cost order. The synthesizer executes candidate programs, checking if they satisfy the input/output examples, until a solution is found. This hybrid approach combines the strengths of LLMs (generating plausible programs) and efficient search techniques (systematic exploration of the program space) to improve program synthesis.

read the caption

Figure 2: An overview of the hybrid program synthesis technique that uses a context-free LLM approximation. Programs generated by an LLM are used to learn a PCFG, which guides a bottom-up synthesizer to generate programs until a solution is found.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of HYSYNTH compared to baselines and ablations across three domains: ARC, TENSOR, and STRING. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) are cumulative plots showing the number of problems solved over time for each domain. The plots illustrate that HYSYNTH outperforms baselines in solving problems faster. Subfigure (d) presents the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by the LLMs used in the experiments, highlighting the challenges posed by generating valid programs in unfamiliar DSLs.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure presents the results of the HYSYNTH program synthesis approach on three different domains: ARC (grid-based puzzles), TENSOR (tensor manipulations), and STRING (string manipulations). Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show the cumulative number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time (in seconds), comparing it to several baselines: unguided search, using only LLMs, and existing synthesizers (ARGA, TFCODER, and PROBE, respectively). Subfigure (d) shows the percentage of syntactically valid programs generated by the LLM in each domain. This demonstrates HYSYNTH’s superior performance over baselines in various domains, especially when handling complex tasks, by leveraging LLMs effectively to guide bottom-up program synthesis.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of HYSYNTH against various baselines and ablations across three different domains (ARC, TENSOR, STRING). Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show cumulative solved problems over time. The timeout for each run is set to 10 minutes. Subfigure (d) shows the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by the language model in each domain.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of HYSYNTH and other methods (baseline synthesizers, unguided search, and direct LLM sampling) on three program synthesis domains: ARC (grid-based puzzles), TENSOR (tensor manipulations), and STRING (string manipulations). Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) are cumulative plots showing the number of benchmarks solved over time. Subfigure (d) shows the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by the LLMs (GPT40 and DEEPSEEK) for each domain.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

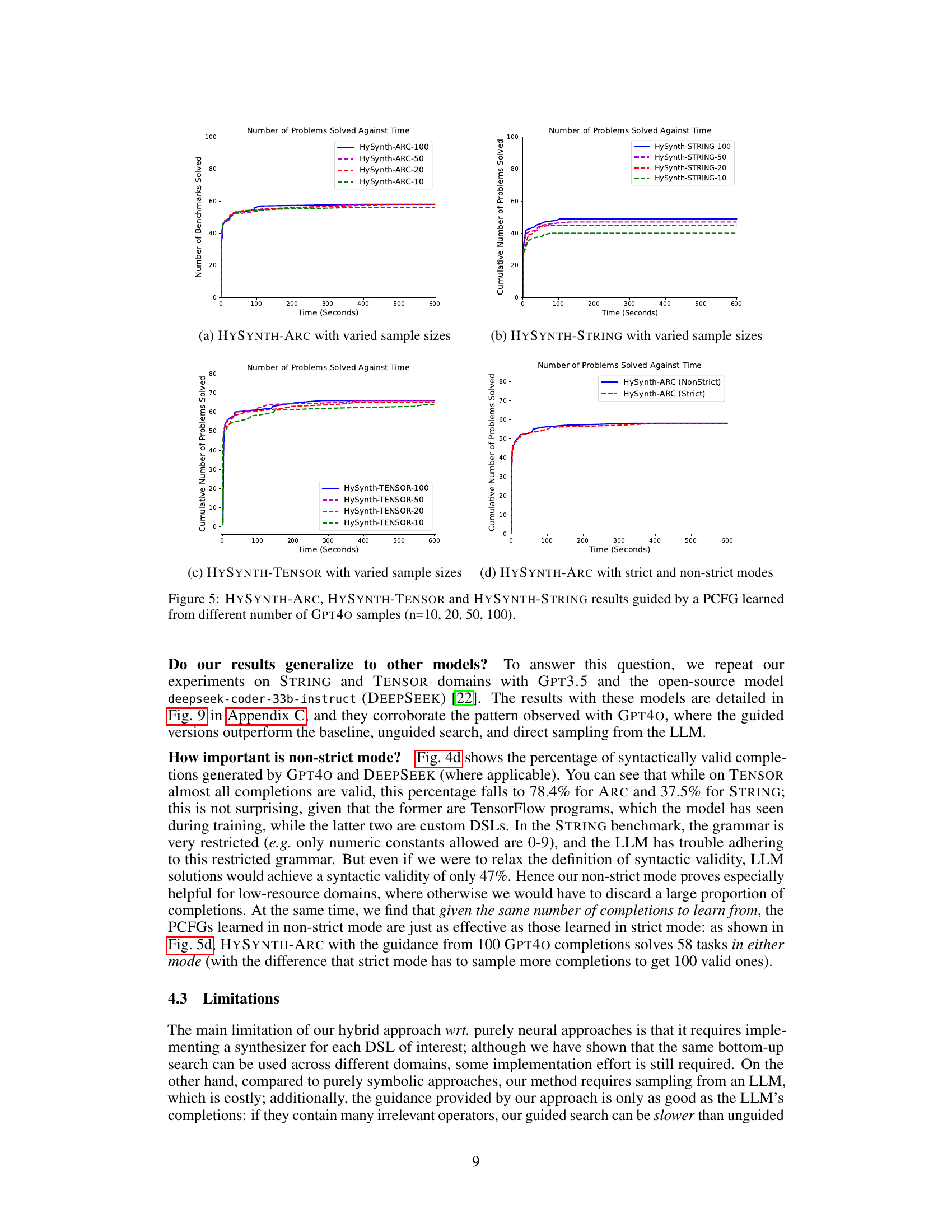

🔼 This figure shows the performance of HYSYNTH, comparing it to baselines and ablations. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) present cumulative plots showing the number of benchmarks solved over time for the ARC, STRING, and TENSOR domains, respectively. The plots illustrate that HYSYNTH outperforms baseline synthesizers and unguided search, and that direct LLM sampling performs poorly. Subfigure (d) shows the percentage of syntactically valid completions generated by the LLMs for each domain.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure displays the performance of HYSYNTH across three different domains (ARC, TENSOR, STRING) by showing the cumulative number of benchmarks solved over time. Subplots (a), (b), and (c) compare HYSYNTH’s performance to baselines (ARGA, PROBE, TFCODER) and ablations (direct LLM sampling, unguided search, binary surrogate). Different sample sizes used to learn the PCFG are also compared. Subplot (d) shows the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by the LLMs in each domain.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of HYSYNTH, comparing it to baselines and ablations across three domains: ARC, TENSOR, and STRING. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) present cumulative problem-solving counts over time, highlighting HYSYNTH’s superior speed. Subfigure (d) displays the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by the LLMs used, revealing a varying degree of grammatical correctness in the LLM outputs which impacts the performance.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of HYSYNTH against baselines and ablations across three domains (ARC, TENSOR, STRING). Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show cumulative number of problems solved over time. Subfigure (d) shows the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by the LLMs for each domain.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of HYSYNTH compared to baselines and ablations across three domains: ARC, TENSOR, and STRING. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) are cumulative plots showing the number of problems solved over time. Each subfigure shows the performance of HYSYNTH with different numbers of LLM samples used to learn the PCFG, as well as the performance of baselines (ARGA, PROBE, TFCODER) and ablations (no search, unguided search, binary surrogate). Subfigure (d) shows the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by the LLM for each domain.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of HYSYNTH’s performance against baselines and ablations across three domains (ARC, TENSOR, STRING). Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show cumulative problem-solving counts over time, highlighting HYSYNTH’s superiority in efficiently finding solutions. Subfigure (d) provides the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by the LLMs used in the experiments.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of HYSYNTH (a hybrid program synthesis approach using LLMs) against time across three different domains: ARC (grid-based puzzles), TENSOR (tensor manipulations), and STRING (string manipulations). Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) present cumulative solved problems over time, comparing HYSYNTH to baseline synthesizers and ablation studies (unguided search, LLM alone, binary surrogate). Subfigure (d) displays the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by LLMs in each domain. The results highlight HYSYNTH’s superior performance in solving PBE tasks compared to existing methods.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

🔼 This figure presents the results of the HYSYNTH experiments on three domains: ARC, TENSOR, and STRING. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) show cumulative plots of the number of benchmarks solved against time for each domain. The plots compare HYSYNTH’s performance against several baselines, including unguided search and the LLM alone. Subfigure (d) displays the percentage of syntactically valid program completions generated by the LLMs for each domain.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a,b,c) Number of benchmarks solved by HYSYNTH as a function of time for the ARC, TENSOR, and STRING domains; timeout is 10 min. (d) Percentage of syntactically valid completions per domain.

Full paper#