TL;DR#

Non-parametric regression using kernel methods, while powerful, suffers from high computational costs, especially when dealing with large datasets. Traditional methods like Nadaraya-Watson (NW) regression and Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) have O(n) and O(n³) time complexities respectively, where n is the number of data points. These complexities hinder their applicability to large datasets.

This work introduces the Supervised Kernel Thinning (KT) algorithm to address this issue. KT cleverly compresses data to create smaller, representative subsets (coresets) while preserving essential information for accurate regression. By integrating KT with NW and KRR, the authors achieve significant speed-ups, reducing the time complexities to O(n log³ n) for training and O(√n) for inference in NW regression, and O(n³/2) training time and O(√n) inference time for KRR. The effectiveness of KT-based estimators is validated on both simulated and real-world datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with kernel methods, as it offers significant speed improvements without sacrificing accuracy. It opens avenues for applying kernel methods to larger datasets and more complex problems, advancing research in various fields relying on non-parametric regression.

Visual Insights#

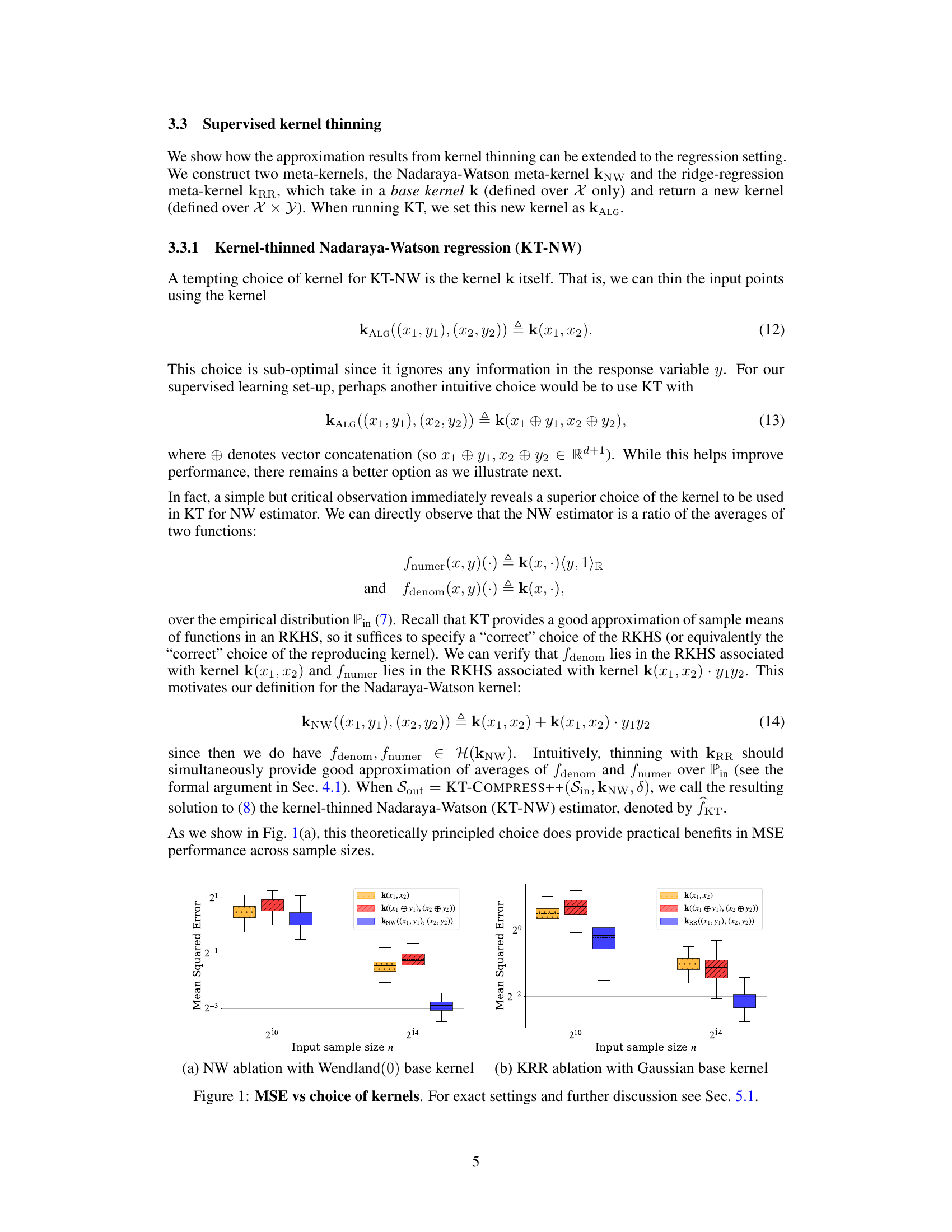

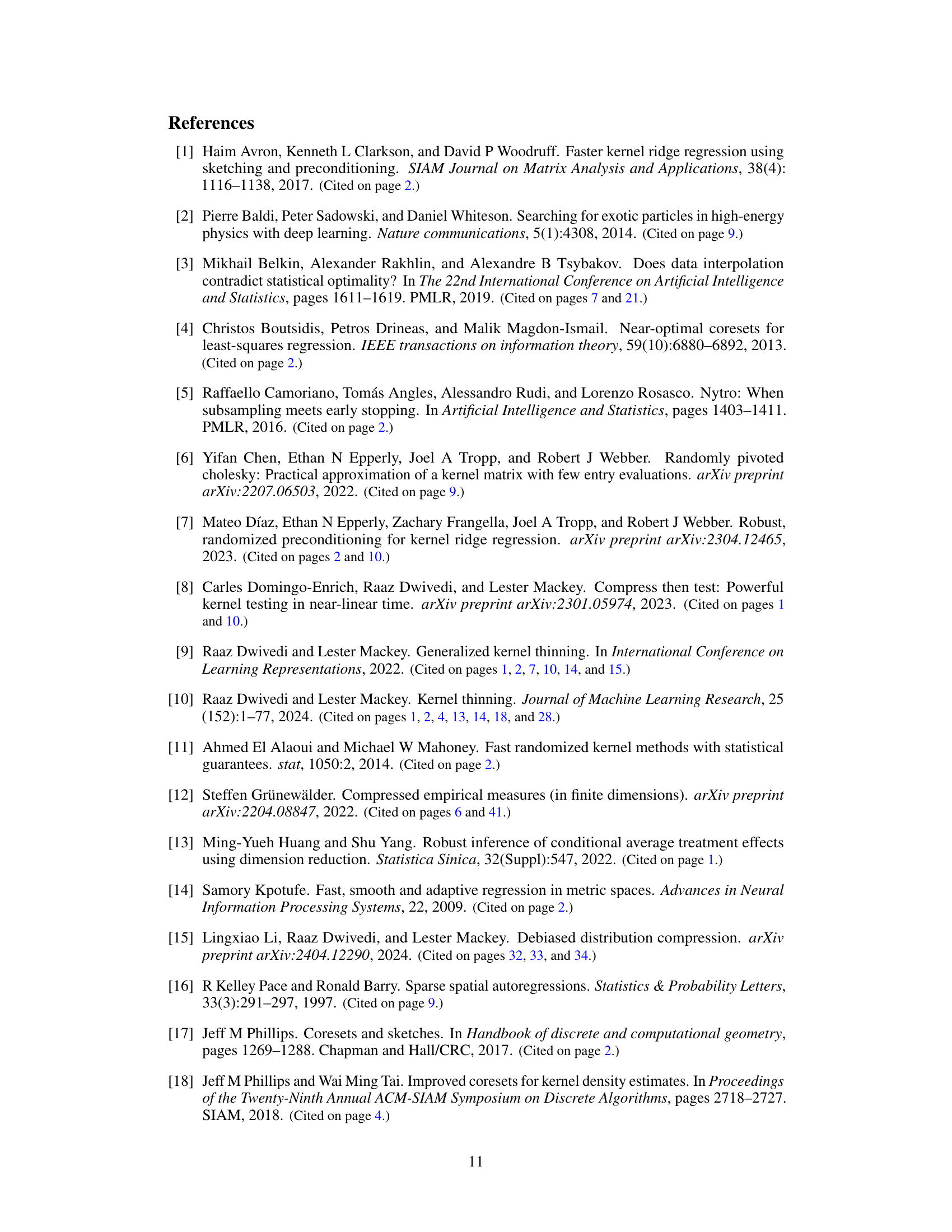

🔼 This figure compares the mean squared error (MSE) performance of Nadaraya-Watson (NW) and Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) estimators using different kernel choices for compression using Kernel Thinning. For NW, three kernels were tested:

k(x1, x2)(using only the input features),k((x1⊕y1),(x2⊕y2))(concatenating input features and response variable), andkNW((x1,y1),(x2,y2))(the proposed kernel in equation 14 combiningk(x1,x2)andk(x1,x2)y1y2). For KRR, the same three kernels were compared, except the proposed kernel is equation 15:k²(x1,x2) + k(x1,x2)y1y2. The x-axis shows the input sample size (n), while the y-axis presents the MSE. The results indicate that the proposed kernels (kNWandkRR) significantly outperform the base kernels.read the caption

Figure 1: MSE vs choice of kernels. For exact settings and further discussion see Sec. 5.1.

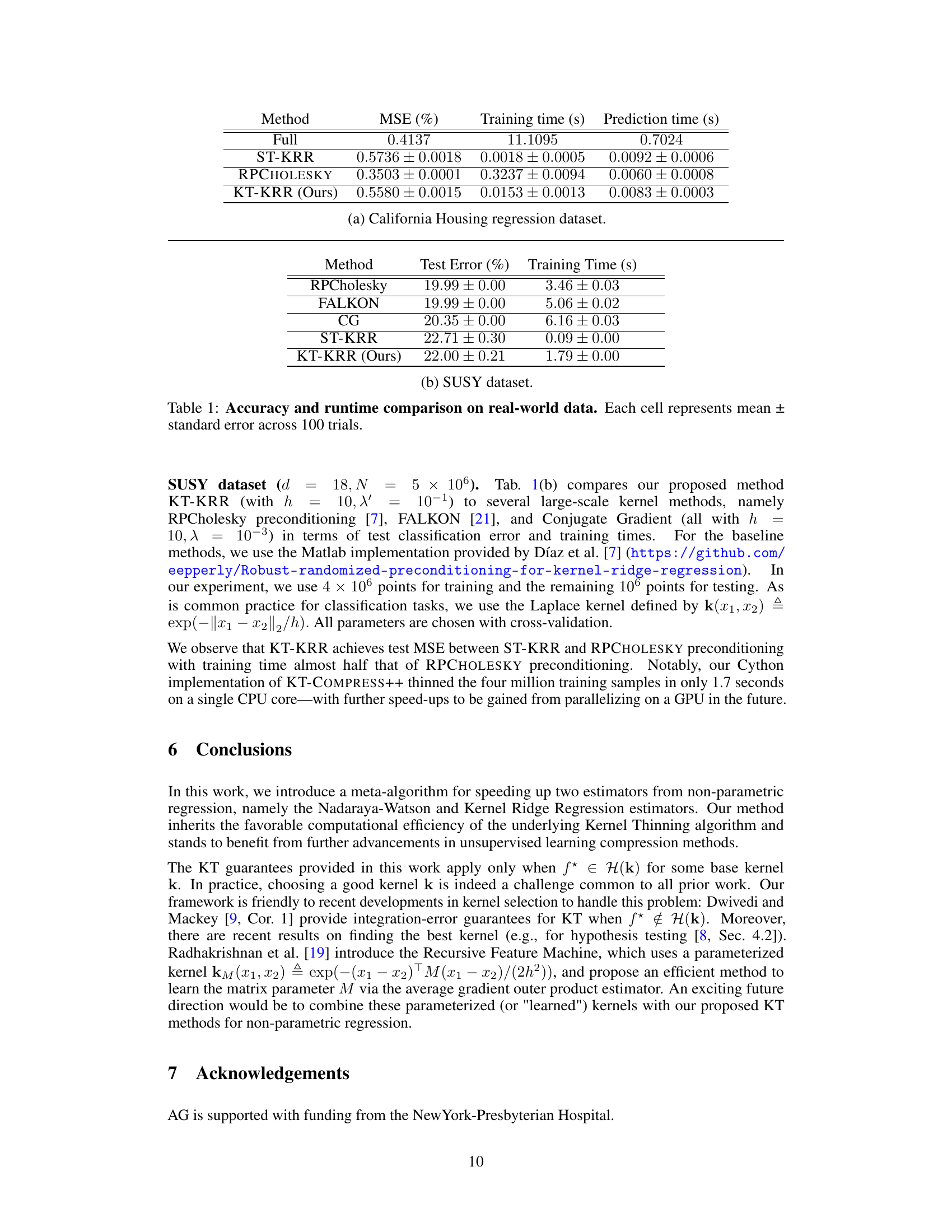

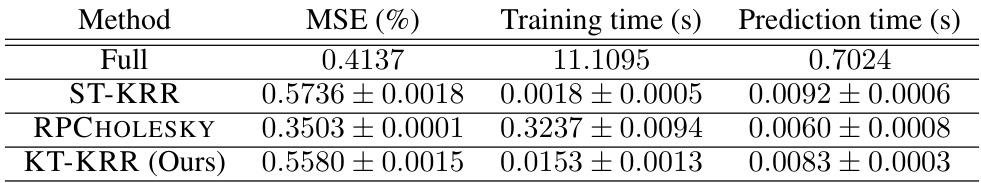

🔼 This table compares the performance of different Kernel Ridge Regression methods on two real-world datasets: California Housing and SUSY. The metrics presented are Mean Squared Error (MSE), training time, and prediction time. The methods compared include the full KRR, standard-thinned KRR, RPCHOLESKY, and the proposed KT-KRR. The results show that KT-KRR achieves a good balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy and runtime comparison on real-world data. Each cell represents mean ± standard error across 100 trials.

In-depth insights#

Supervised KT#

Supervised Kernel Thinning (KT) offers a novel approach to accelerate supervised learning with kernel methods. It extends the unsupervised KT algorithm, known for efficiently compressing data, to the supervised setting. The core idea is to leverage KT’s ability to create high-fidelity coresets (smaller representative subsets of data) to significantly reduce the computational burden of kernel regression. By cleverly designing appropriate meta-kernels for Nadaraya-Watson (NW) and Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR), the authors demonstrate a quadratic speed-up in both training and inference, without substantial loss in accuracy. Theoretical guarantees are provided for KT-NW and KT-KRR, highlighting their superior computational and statistical efficiency compared to standard thinning baselines. Empirical results showcase the efficacy of this approach on both simulated and real-world datasets, underscoring its practical utility for large-scale kernel regression problems. The use of meta-kernels is key to effectively incorporating the response variables into the compression process and achieving optimal results. Theoretical analysis includes novel multiplicative error guarantees for the compression step, showing improvements over other methods. The methodology is particularly valuable for high-dimensional data, where traditional kernel methods often prove computationally intractable.

KT-NW & KT-KRR#

The proposed KT-NW and KT-KRR estimators offer a compelling approach to non-parametric regression by integrating kernel thinning (KT). KT-NW leverages KT to speed up Nadaraya-Watson regression, achieving a quadratic speedup in training and inference while maintaining competitive statistical efficiency. KT-KRR extends the idea to kernel ridge regression, also demonstrating significant computational improvements. The theoretical analysis provides novel multiplicative error guarantees for KT, showcasing superior performance over baseline methods. This work successfully bridges the gap between unsupervised and supervised coreset techniques, delivering computationally efficient estimators for kernel methods with strong theoretical backing.

Error Guarantees#

The core of this research paper revolves around establishing rigorous error guarantees for its novel supervised kernel thinning (KT) algorithms applied to non-parametric regression. The authors don’t simply demonstrate improved empirical performance but provide theoretical bounds on the mean squared error (MSE) for both Kernel-Thinned Nadaraya-Watson (KT-NW) and Kernel-Thinned Kernel Ridge Regression (KT-KRR) estimators. These bounds highlight the superior computational efficiency of KT-based methods over full-data approaches, achieving significant speed-ups in both training and inference while maintaining competitive statistical accuracy. A key aspect of their analysis involves proving new multiplicative error guarantees for the KT compression technique itself, demonstrating that KT successfully summarizes the input data distribution. Different error bounds are derived depending on the type of kernel used (finite or infinite dimensional) and the smoothness properties of the underlying function. Ultimately, these error guarantees provide strong theoretical justification for the practical advantages observed in the experiments, solidifying the KT approach as an efficient and effective method for handling large-scale kernel regression.

Empirical Results#

The empirical results section of a research paper is crucial for validating the theoretical claims. A strong empirical results section will present results from multiple experiments, clearly showing the proposed method’s performance compared to relevant baselines. It’s important to use appropriate metrics and visualizations to effectively communicate these results. The discussion should acknowledge limitations, such as the choice of datasets or hyperparameters, highlighting the robustness and generalizability of the findings. A detailed description of experimental setup, including datasets, training procedures, and evaluation metrics, is essential for reproducibility. Finally, statistical significance testing is crucial to determine if observed differences are meaningful or due to chance. The overall goal is to provide a compelling narrative that showcases the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed approach, alongside a thoughtful analysis that considers potential biases and limitations.

Future Work#

The authors mention several promising avenues for future work. Extending the KT-KRR guarantees to infinite-dimensional kernels beyond the LOGGROWTH and POLYGROWTH classes is a significant direction, as many common kernels fall outside these categories. Improving the MSE rate for KT-KRR, potentially by developing novel techniques to leverage kernel geometry more effectively, is another key area. Investigating the practical implications of adaptive bandwidth selection for KT-NW would improve its robustness across various data distributions. Finally, combining KT with techniques for kernel selection or learning would allow the benefits of KT to be realized across even a wider range of supervised learning problems. These future research directions highlight the potential of integrating coreset methods with other advances in nonparametric statistics and machine learning to develop more computationally efficient and statistically robust models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

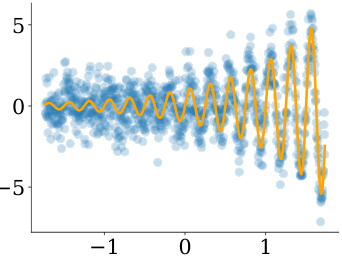

🔼 This figure displays simulated data generated for the simulation studies in Section 5.1. The x-axis represents the input variable X, drawn uniformly from [-√3, √3], while the y-axis shows the response variable Y, generated according to the equation Y = 8sin(8X)exp(X) + σw, where w ~ N(0, 1) is random noise and σ = 1 is the noise level. The blue points represent the generated data, while the orange line depicts the true regression function f*(x) = 8sin(8X)exp(X).

read the caption

Figure 2: Simulated data.

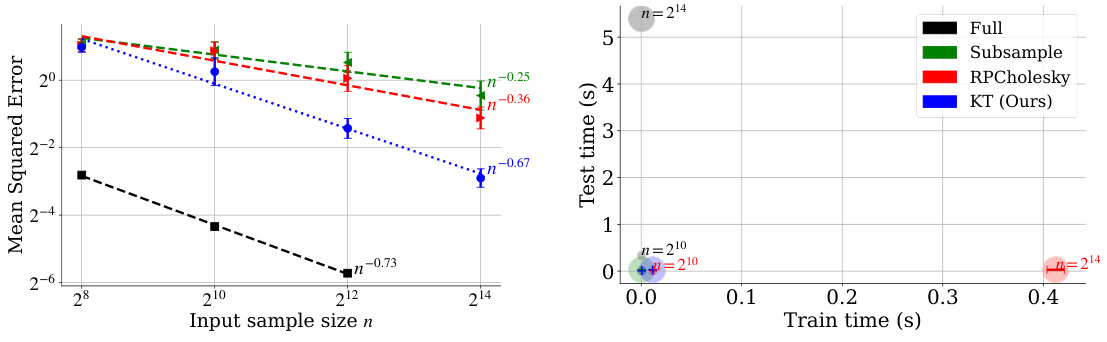

🔼 This figure compares the performance of four different methods for non-parametric regression on simulated data: Full Nadaraya-Watson (NW), Standard Thinned NW, RPCholesky NW, and KT-NW. The left panel shows the Mean Squared Error (MSE) of each method against varying input sample size (n). Error bars indicate standard deviation across 100 trials. The right panel displays a scatter plot showing the train time vs. the test time for each method at different sample sizes. The results demonstrate that KT-NW achieves a favorable balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 3: MSE and runtime comparison on simulated data. Each point plots the mean and standard deviation across 100 trials (after parameter grid search).

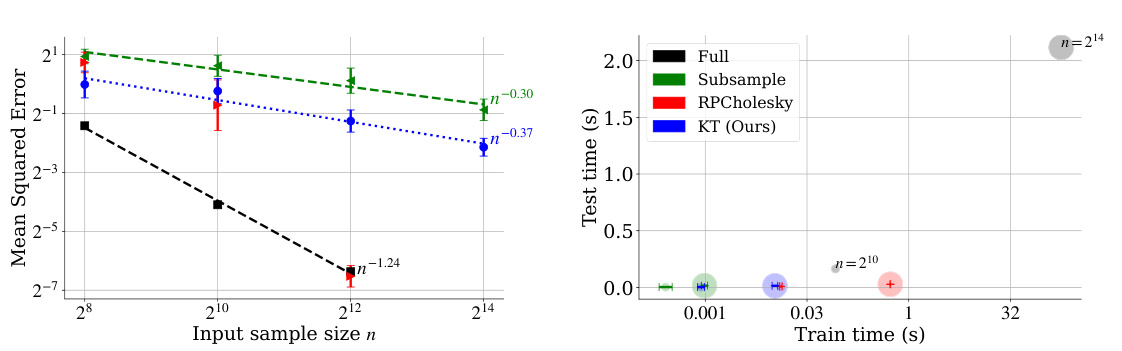

🔼 This figure compares the performance of four different methods for non-parametric regression on simulated data. The methods are FULL-NW (full Nadaraya-Watson), ST-NW (standard thinned Nadaraya-Watson), RPCHOLESKY-NW (RPC-Cholesky Nadaraya-Watson), and KT-NW (Kernel Thinned Nadaraya-Watson). The figure shows the mean squared error (MSE) and runtime for training and testing. The results demonstrate that KT-NW outperforms the other methods in terms of MSE and runtime across varying sample sizes (n).

read the caption

Figure 3: MSE and runtime comparison on simulated data. Each point plots the mean and standard deviation across 100 trials (after parameter grid search).

More on tables

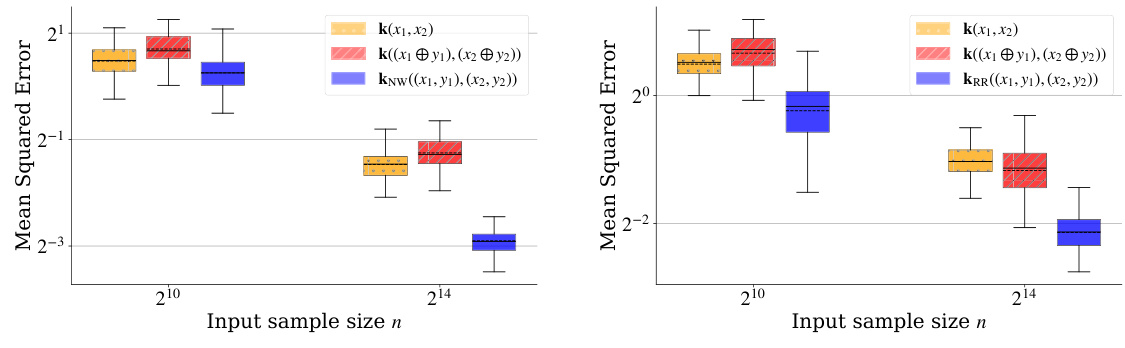

🔼 This table compares the performance of different Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR) methods on two real-world datasets: California Housing and SUSY. The methods compared include FULL-KRR (the standard KRR), ST-KRR (standard thinning), RPCHOLESKY-KRR (using the RPCHOLESKY algorithm for coreset selection), and KT-KRR (the proposed method using Kernel Thinning). The table shows the test error (in percentage) and the training time (in seconds) for each method. The results demonstrate the computational efficiency of KT-KRR compared to FULL-KRR, while maintaining competitive accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy and runtime comparison on real-world data. Each cell represents mean ± standard error across 100 trials.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different kernel ridge regression methods on two real-world datasets: California Housing and SUSY. The metrics reported are Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression and Test Error for classification, along with training and prediction times. The methods compared include the full kernel ridge regression (FULL-KRR), standard thinning based KRR (ST-KRR), RPCHOLESKY-KRR, and the proposed kernel-thinned KRR (KT-KRR). The table demonstrates the computational efficiency of KT-KRR while maintaining competitive accuracy compared to other methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy and runtime comparison on real-world data. Each cell represents mean ± standard error across 100 trials.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different kernel ridge regression methods on two real-world datasets: California Housing and SUSY. The metrics reported include Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression and Test Error for classification. Training and prediction times are also provided to illustrate the computational efficiency of each method. The results demonstrate the trade-off between accuracy and runtime for various approaches, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed KT-KRR method in balancing both.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy and runtime comparison on real-world data. Each cell represents mean ± standard error across 100 trials.

Full paper#