TL;DR#

Differentially Private Stochastic Gradient Descent (DP-SGD) is a common approach for training machine learning models while preserving data privacy. A standard technique involves shuffling the data to improve privacy analysis, assuming the privacy is equivalent to Poisson subsampling. However, prior research has only compared these methods with a single epoch, leaving the multi-epoch analysis unclear. This also creates issues with the existing privacy analysis, as shuffling and Poisson subsampling often provide different privacy guarantees, especially when scaled for multiple epochs. This lack of precise privacy accounting impacts the utility and the reliability of DP-SGD algorithms.

This research directly addresses this problem by providing a comprehensive multi-epoch privacy analysis comparing shuffling and Poisson subsampling methods. They introduce a novel, scalable approach to implement Poisson subsampling at scale, overcoming previous limitations. Their findings reveal substantial gaps in the privacy guarantees of shuffling-based DP-SGD when compared to Poisson subsampling, particularly in multiple epochs. The study provides lower bounds on shuffling privacy that show how much lower the real privacy guarantees are than previously assumed. They support these findings with extensive experiments showing Poisson subsampling outperforms shuffling-based approaches in many practical scenarios. This work contributes significantly to the field by improving the accuracy of privacy accounting for DP-SGD and suggesting better methods for training private models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the common practice of using shuffling in DP-SGD, offering a more accurate privacy analysis and a scalable solution for Poisson subsampling. This impacts the reliability and utility of differentially private machine learning models, opening avenues for improved privacy-preserving algorithms and applications.

Visual Insights#

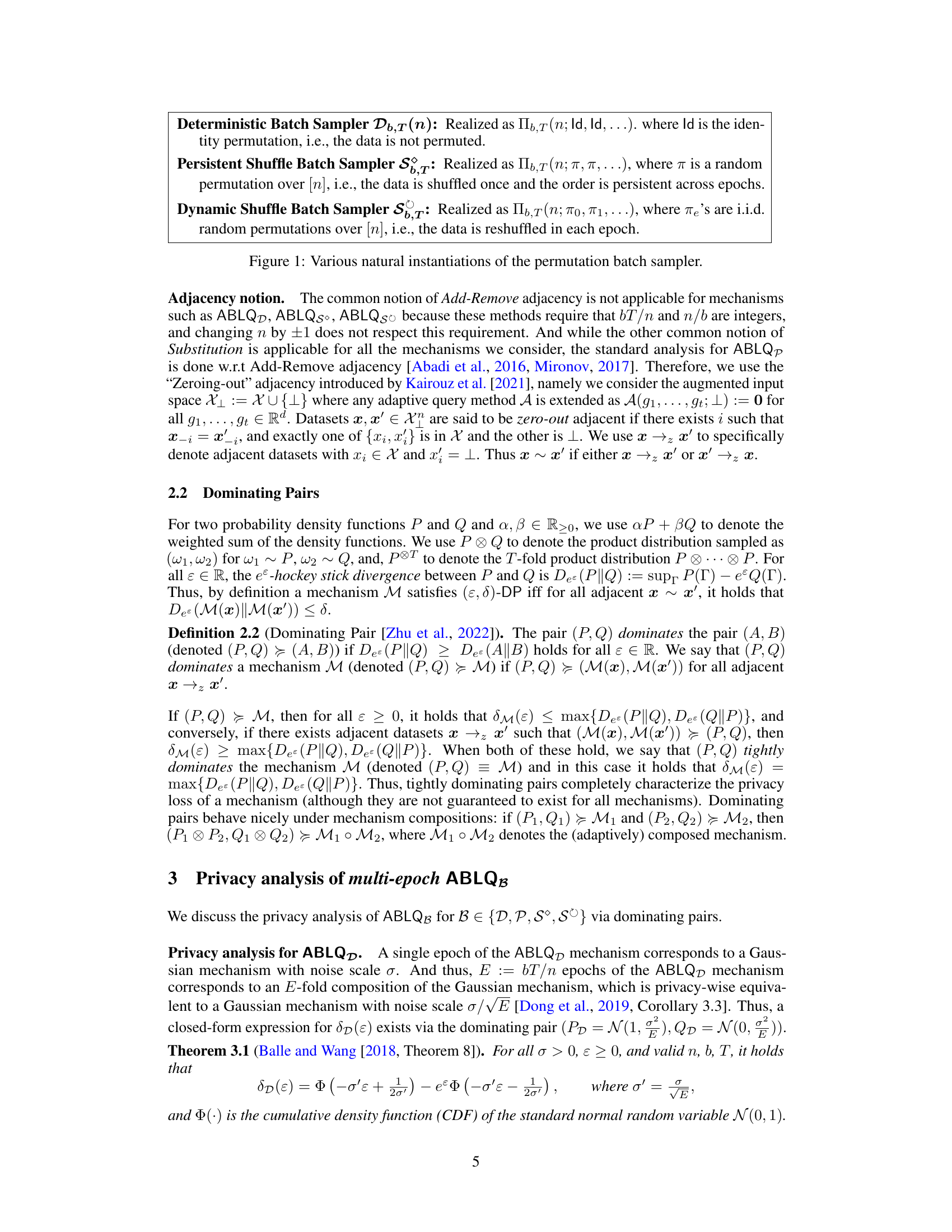

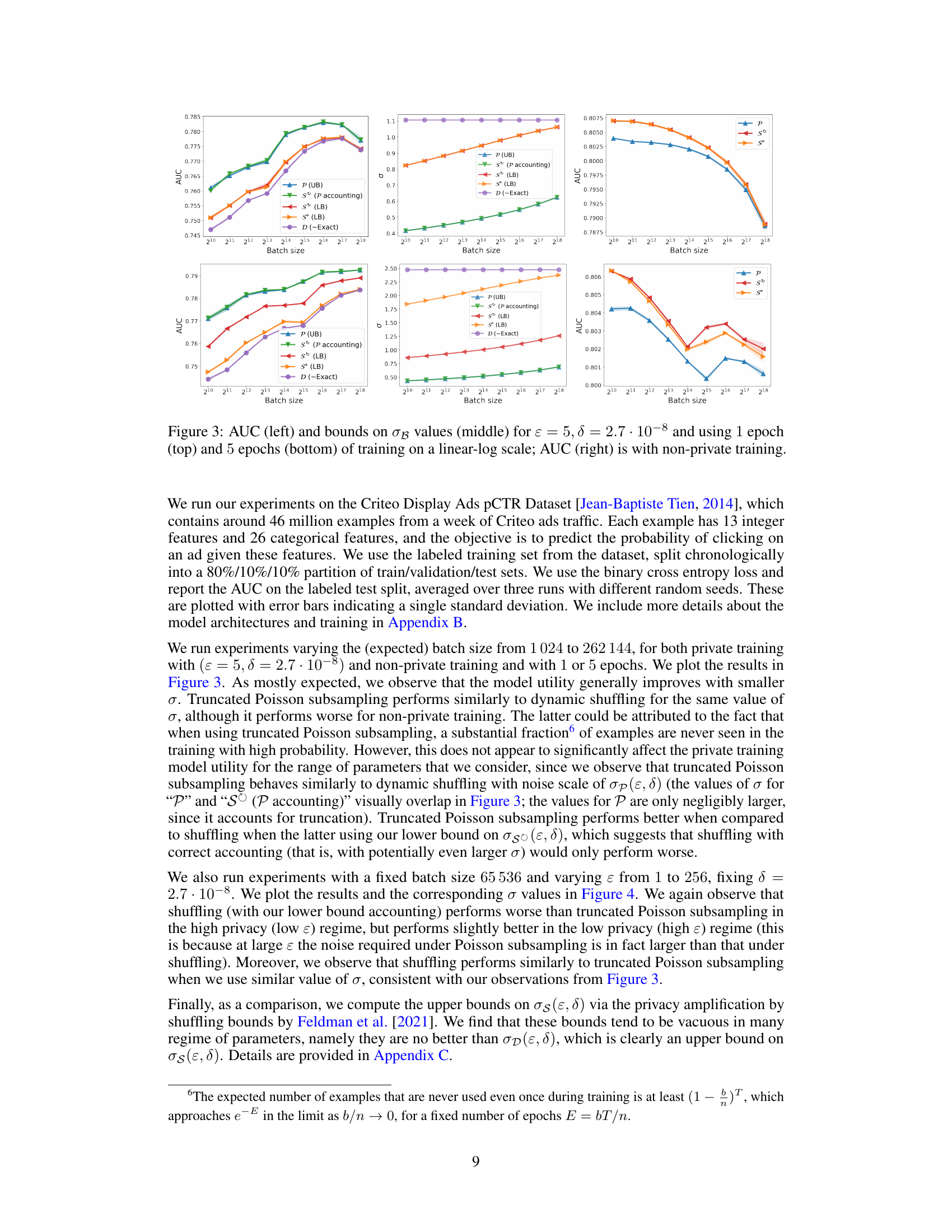

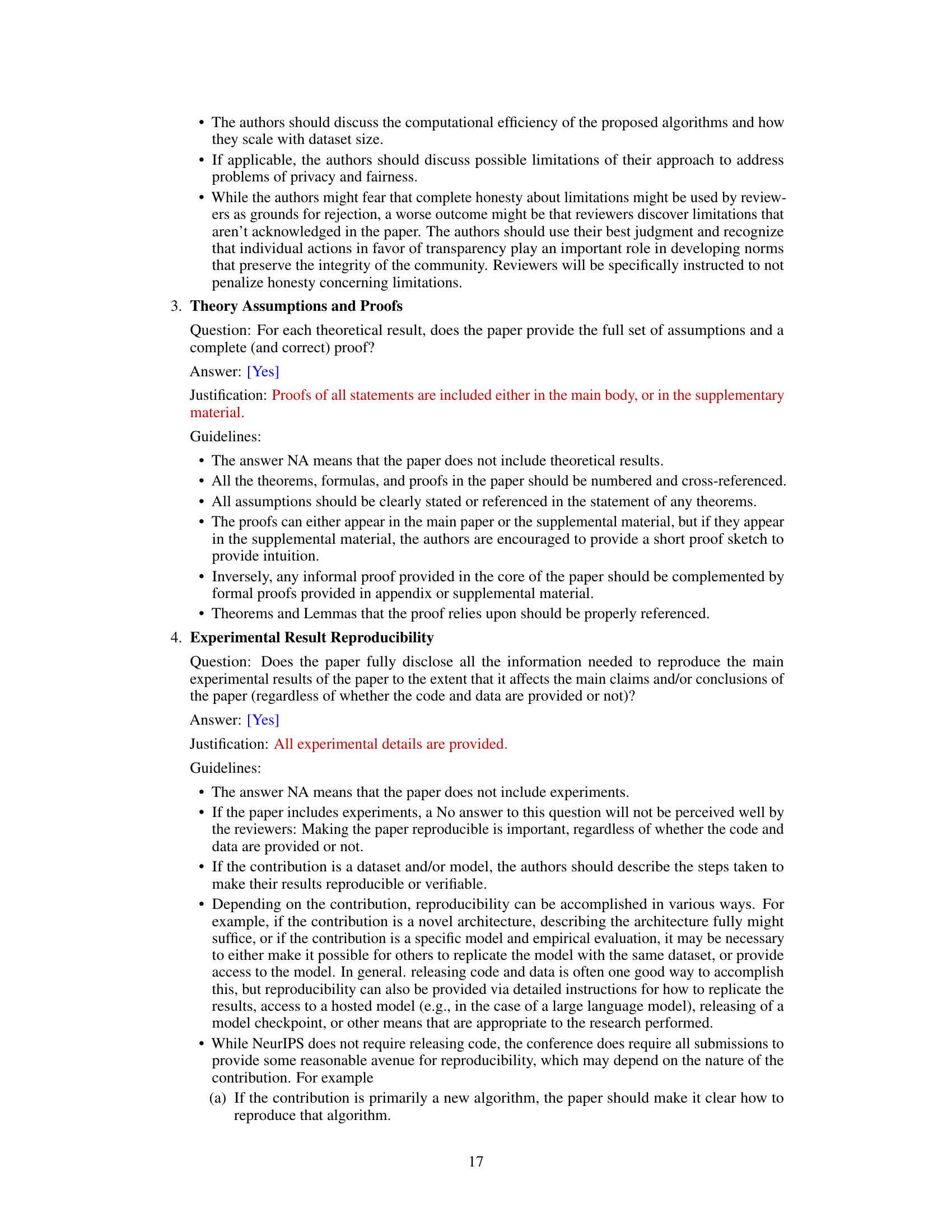

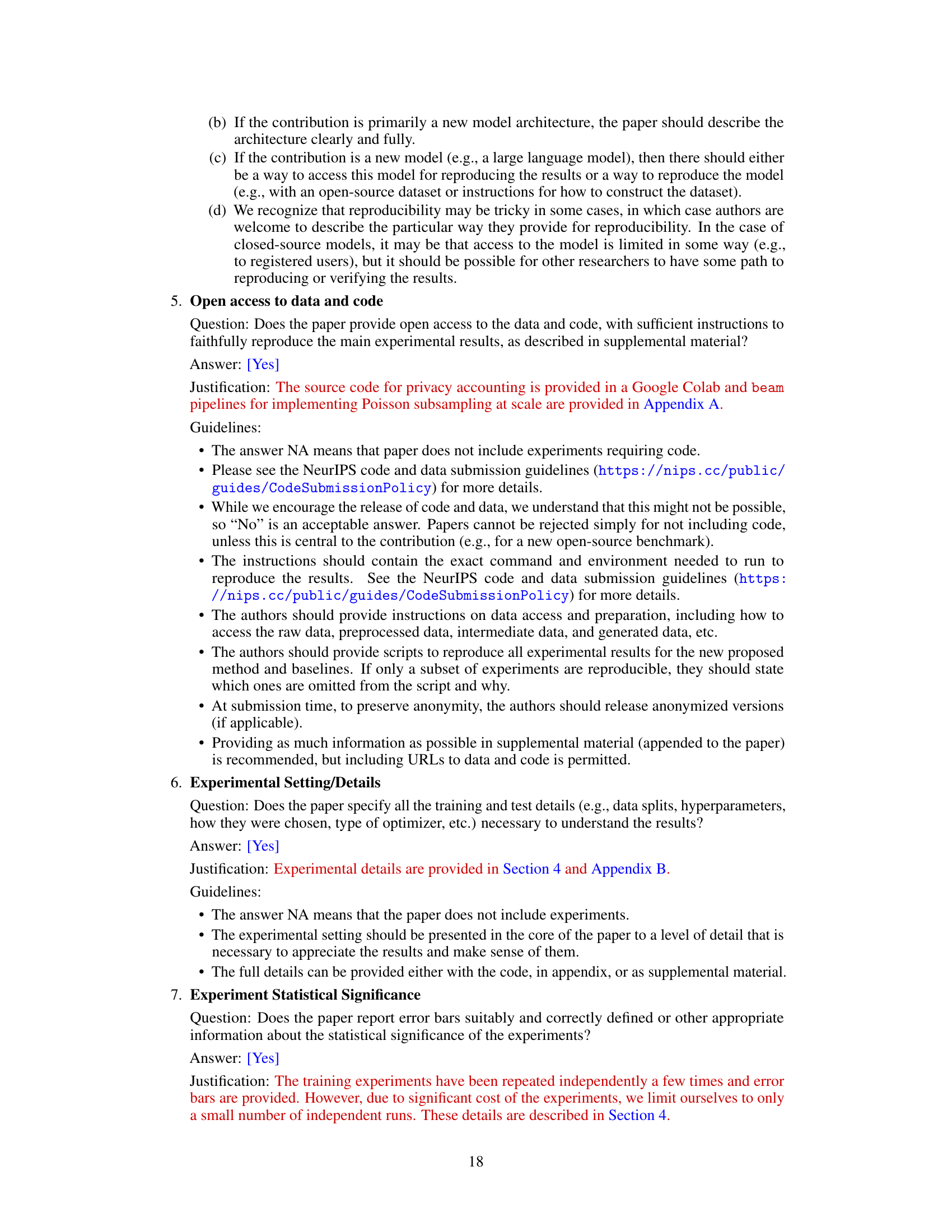

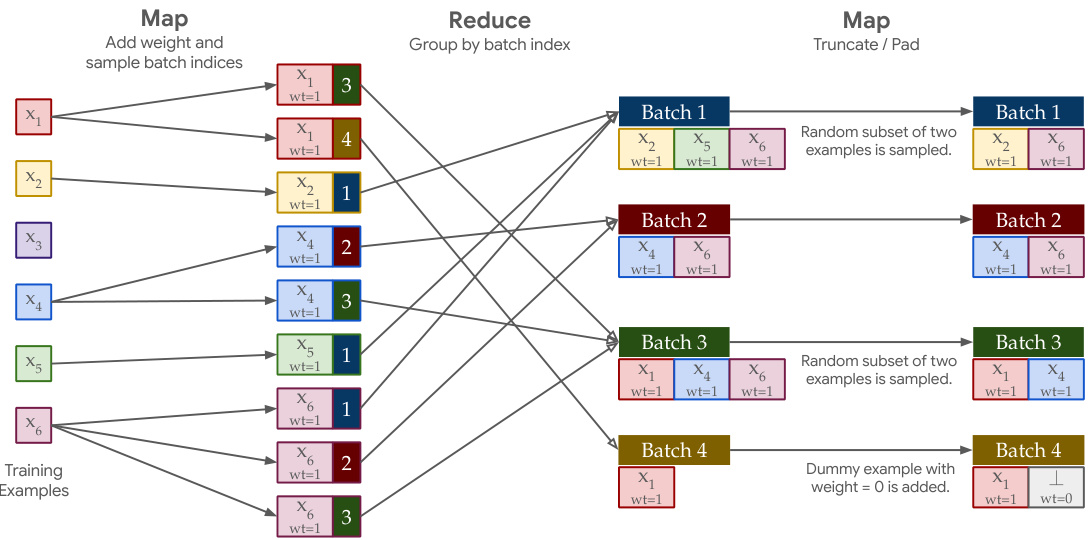

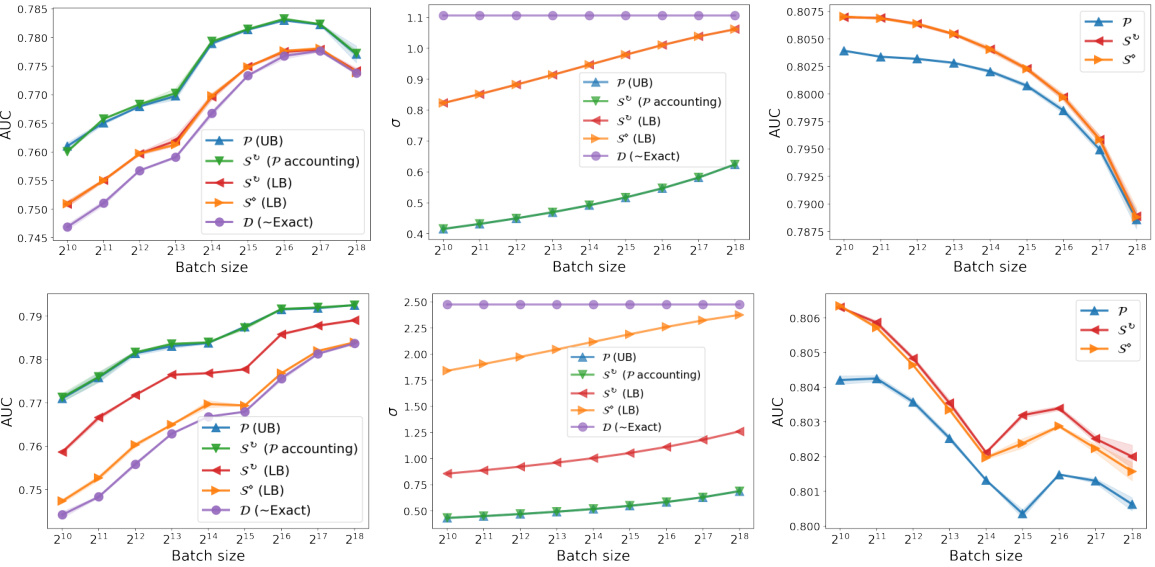

🔼 This figure compares the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and noise scale (σ) values for different batch sampling methods in differentially private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD) training. It shows results for both 1 and 5 epochs of training, across varying batch sizes. The left panel displays AUC, a measure of model performance. The middle panel shows the calculated noise scales (σ) for Deterministic, Truncated Poisson, Persistent Shuffling and Dynamic Shuffling batch samplers, using both lower bounds and (where available) optimistic estimates based on privacy analyses in the paper. The right panel shows AUC achieved with non-private training (for comparison). The linear-log scale emphasizes differences in behavior across different parameter settings.

read the caption

Figure 3: AUC (left) and bounds on σβ values (middle) for ε = 5, δ = 2.7 · 10−8 and using 1 epoch (top) and 5 epochs (bottom) of training on a linear-log scale; AUC (right) is with non-private training.

In-depth insights#

DP-SGD Scalability#

DP-SGD’s scalability is a critical challenge in applying differential privacy to large-scale machine learning. The paper investigates this issue by comparing two common mini-batch sampling strategies: shuffling and Poisson subsampling. While shuffling is widely used due to its simplicity, the authors demonstrate that it offers significantly weaker privacy guarantees than Poisson subsampling, especially over multiple epochs. This finding highlights a critical gap in the current understanding of DP-SGD’s privacy properties and challenges the common practice of using shuffling while reporting privacy parameters as if Poisson subsampling was used. To address this, the authors propose a scalable and practical approach to implementing Poisson subsampling at scale via massively parallel computation. Their experimental results show that models trained using Poisson subsampling with correct privacy accounting achieve comparable or even better utility compared to models trained using shuffling, which suggests that Poisson subsampling is a more robust and efficient method for achieving privacy-preserving scalability in DP-SGD.

Shuffle vs. Poisson#

The core of this research lies in comparing two distinct mini-batch sampling methods for differentially private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD): shuffling and Poisson subsampling. The authors demonstrate that the common practice of using shuffling while employing privacy parameters calculated for Poisson subsampling is fundamentally flawed. This is because shuffling introduces dependencies between mini-batches, leading to significantly weaker privacy guarantees than previously assumed. Poisson subsampling, on the other hand, generates independent batches, resulting in tighter privacy bounds. While shuffling is often preferred for its practical implementation simplicity, the study reveals a substantial privacy gap, highlighting the critical need for accurate privacy accounting. The paper provides new lower bounds for shuffled ABLQ, offering more realistic privacy guarantees for shuffling-based DP-SGD. Importantly, it also presents a scalable approach for implementing Poisson subsampling, thus enabling a direct comparison of utility with accurate privacy accounting. This comprehensive analysis ultimately underscores the importance of choosing the appropriate sampling method and performing accurate privacy analysis for reliable and trustworthy results in DP-SGD training.

Multi-Epoch ABLQ#

The concept of “Multi-Epoch ABLQ” extends the single-epoch analysis of Adaptive Batch Linear Queries (ABLQ) to encompass multiple training epochs. This is crucial because real-world differentially private training often involves multiple passes over the data, unlike the simplification of a single epoch. Analyzing multiple epochs reveals substantial differences in privacy guarantees between shuffling and Poisson subsampling, challenging the common practice of using shuffling in DP-SGD but reporting privacy parameters as if Poisson subsampling was used. The multi-epoch analysis provides tighter, more realistic lower bounds on the privacy offered by shuffled ABLQ, highlighting the limitations of optimistic privacy accounting methods. This improved understanding necessitates a reevaluation of shuffling-based DP-SGD implementations and the utility of models trained with it. Developing efficient methods for Poisson subsampling at scale becomes paramount, given its superior privacy properties when correctly accounted for, to enable practical adoption of a more privacy-preserving training strategy.

Privacy Amplification#

The concept of privacy amplification is central to differentially private mechanisms, particularly in the context of iterative training algorithms like DP-SGD. The core idea revolves around reducing the overall privacy loss by composing multiple differentially private steps, such as individual gradient updates in DP-SGD. This paper focuses on the discrepancy between theoretical privacy guarantees assuming Poisson subsampling and the practical use of shuffling during batch sampling. The authors highlight a significant gap, showing that shuffling may not offer the same level of privacy amplification as idealized Poisson subsampling, thereby questioning the common practice of using shuffling but reporting privacy parameters as if Poisson subsampling were used. Their analysis reveals that the privacy guarantee with shuffling can be considerably weaker than commonly believed, especially for small noise scales (σ). The paper addresses this by introducing a scalable implementation of Poisson subsampling at scale, which enables a more accurate estimation of utility when the correct privacy accounting is performed. This study emphasizes the importance of accurate privacy accounting and underscores the potential pitfalls of relying on optimistic estimates of privacy protection when employing shuffling-based techniques.

Future Work#

The paper’s findings open several avenues for future research. Improving the theoretical understanding of shuffling-based DP-SGD remains crucial; the current lower bounds highlight significant privacy gaps compared to Poisson subsampling, but tighter upper bounds are needed for a complete picture. Investigating other shuffling techniques beyond persistent and dynamic shuffling, such as those used in common deep learning libraries, is important. Developing more efficient and scalable implementations of Poisson subsampling, especially for datasets that don’t allow efficient random access, would significantly increase the practical relevance of this approach. Analyzing the impact of different batch sizes and the number of epochs on the privacy-utility trade-off is another important area. Finally, exploring the application of these findings to other private machine learning algorithms and problem domains beyond the scope of the current study would provide a broader understanding of their utility.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure compares the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and the noise scale (σ) values for different batch sampling methods in differentially private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD). The left panel shows AUC values for different batch sampling methods (Deterministic, Truncated Poisson, Persistent Shuffling, and Dynamic Shuffling) for 1 and 5 epochs of training. The middle panel displays the lower and upper bounds on the required noise scale (σ) for each method to achieve a specific privacy guarantee (ε = 5, δ = 2.7 · 10−8). The right panel presents the AUC values obtained with non-private training (no noise added) for comparison. The results show that Poisson subsampling and dynamic shuffling perform similarly for the same noise scale, but the upper bounds for shuffling are much higher in high-privacy regimes.

read the caption

Figure 3: AUC (left) and bounds on σß values (middle) for ε = 5, δ = 2.7 · 10−8 and using 1 epoch (top) and 5 epochs (bottom) of training on a linear-log scale; AUC (right) is with non-private training.

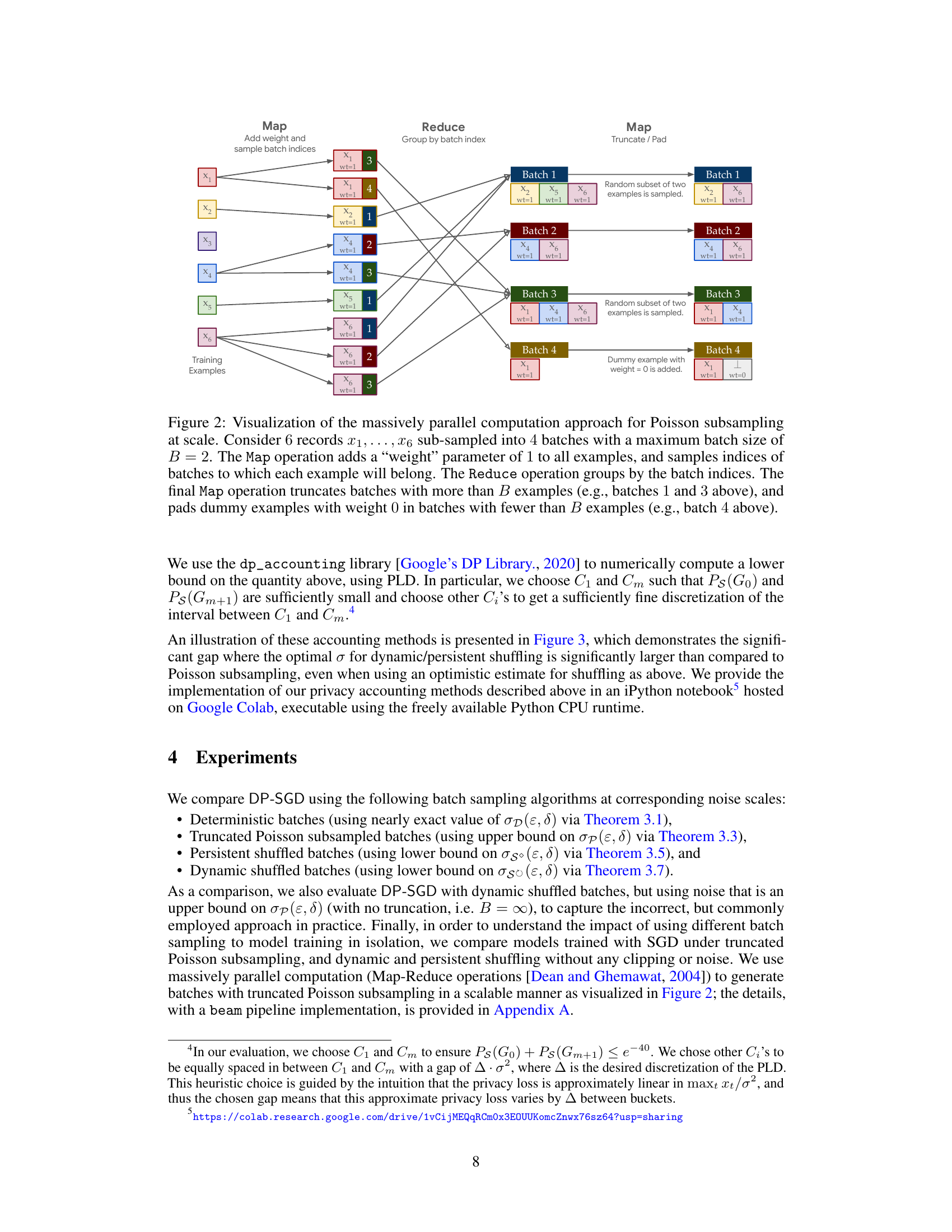

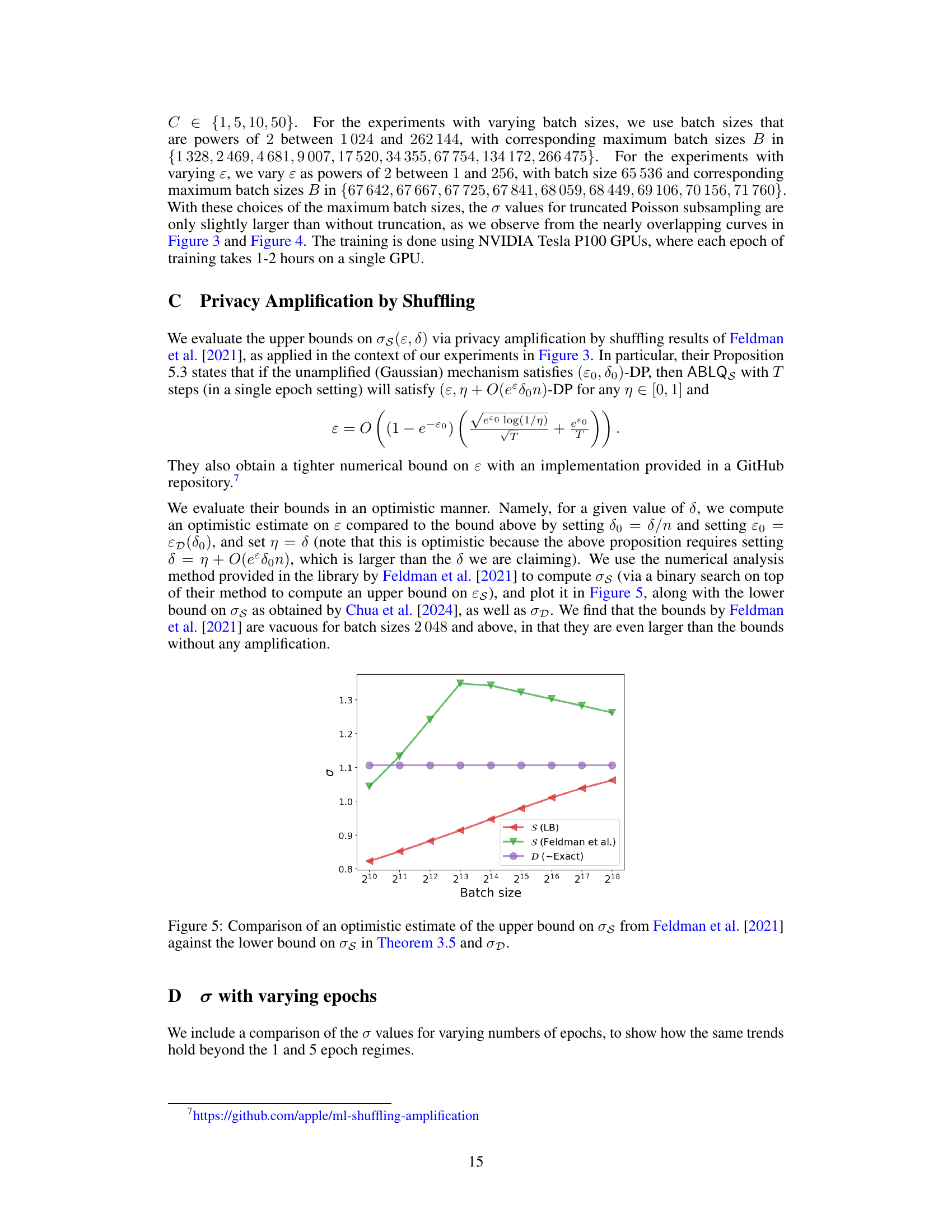

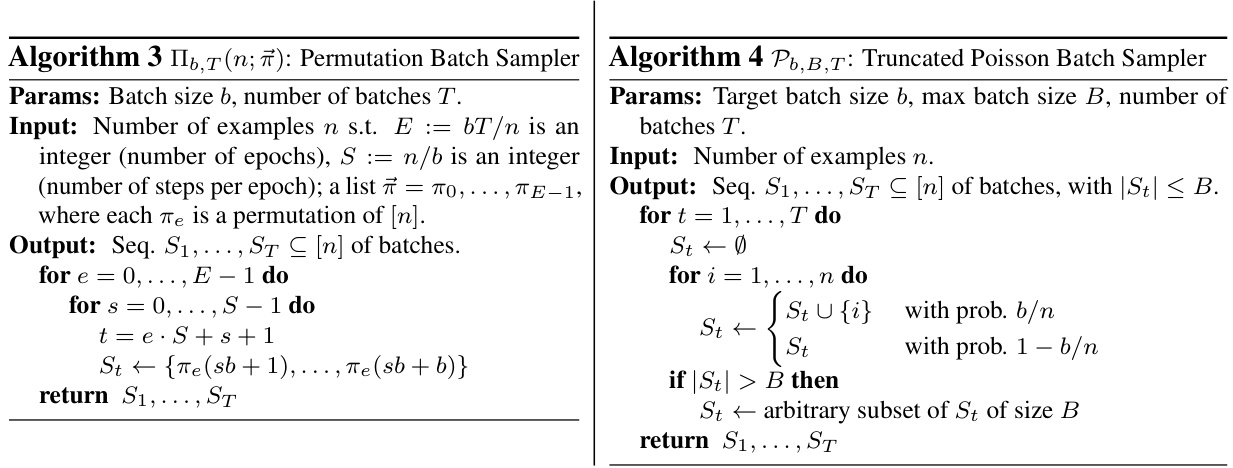

🔼 This figure illustrates the massively parallel computation approach used for implementing truncated Poisson subsampling. The process is broken down into three MapReduce steps. The first Map step adds a weight (1) to each example and samples batch indices for each example. The Reduce step groups examples by their assigned batch index. The final Map step truncates batches exceeding the maximum size (B) by randomly selecting a subset, and pads batches smaller than B with dummy examples having a weight of 0. This approach enables efficient handling of truncated Poisson subsampling at scale.

read the caption

Figure 2: Visualization of the massively parallel computation approach for Poisson subsampling at scale. Consider 6 records x1,..., x6 sub-sampled into 4 batches with a maximum batch size of B = 2. The Map operation adds a 'weight' parameter of 1 to all examples, and samples indices of batches to which each example will belong. The Reduce operation groups by the batch indices. The final Map operation truncates batches with more than B examples (e.g., batches 1 and 3 above), and pads dummy examples with weight 0 in batches with fewer than B examples (e.g., batch 4 above).

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different batch sampling methods for differentially private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD) training. The left panel shows the area under the curve (AUC) for each method. The middle panel displays the noise scale (σ) bounds for different privacy parameters. The right panel presents the AUC achieved without differential privacy for comparison. Results are shown for both 1 and 5 epochs of training, illustrating the effect of the number of epochs on performance and privacy.

read the caption

Figure 3: AUC (left) and bounds on σß values (middle) for ε = 5, δ = 2.7 · 10⁻⁸ and using 1 epoch (top) and 5 epochs (bottom) of training on a linear-log scale; AUC (right) is with non-private training.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different batch sampling methods in differentially private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD). The left panel shows the area under the curve (AUC) for different batch sampling methods, including truncated Poisson subsampling, persistent shuffling, dynamic shuffling, and deterministic batches. The middle panel displays the bounds on the noise scale (σ) required to achieve the target privacy level (ε, δ) for each method. The right panel shows the AUC for non-private training for comparison. The results are shown for both 1 and 5 epochs of training.

read the caption

Figure 3: AUC (left) and bounds on σß values (middle) for ε = 5, δ = 2.7 · 10−8 and using 1 epoch (top) and 5 epochs (bottom) of training on a linear-log scale; AUC (right) is with non-private training.

🔼 This figure compares the Area Under the Curve (AUC) and noise scales (σ) for different batch sampling methods in differentially private stochastic gradient descent (DP-SGD) with varying batch sizes and epochs. The left panel shows AUC performance, the middle panel shows the required noise scale (σ) for different methods, and the right panel shows AUC performance without differential privacy. The figure reveals that the truncated Poisson subsampling method yields better AUC performance and lower noise scales in the high privacy regime, compared to shuffled sampling approaches with even optimistic privacy accounting.

read the caption

Figure 3: AUC (left) and bounds on σβ values (middle) for ε = 5, δ = 2.7 · 10−8 and using 1 epoch (top) and 5 epochs (bottom) of training on a linear-log scale; AUC (right) is with non-private training.

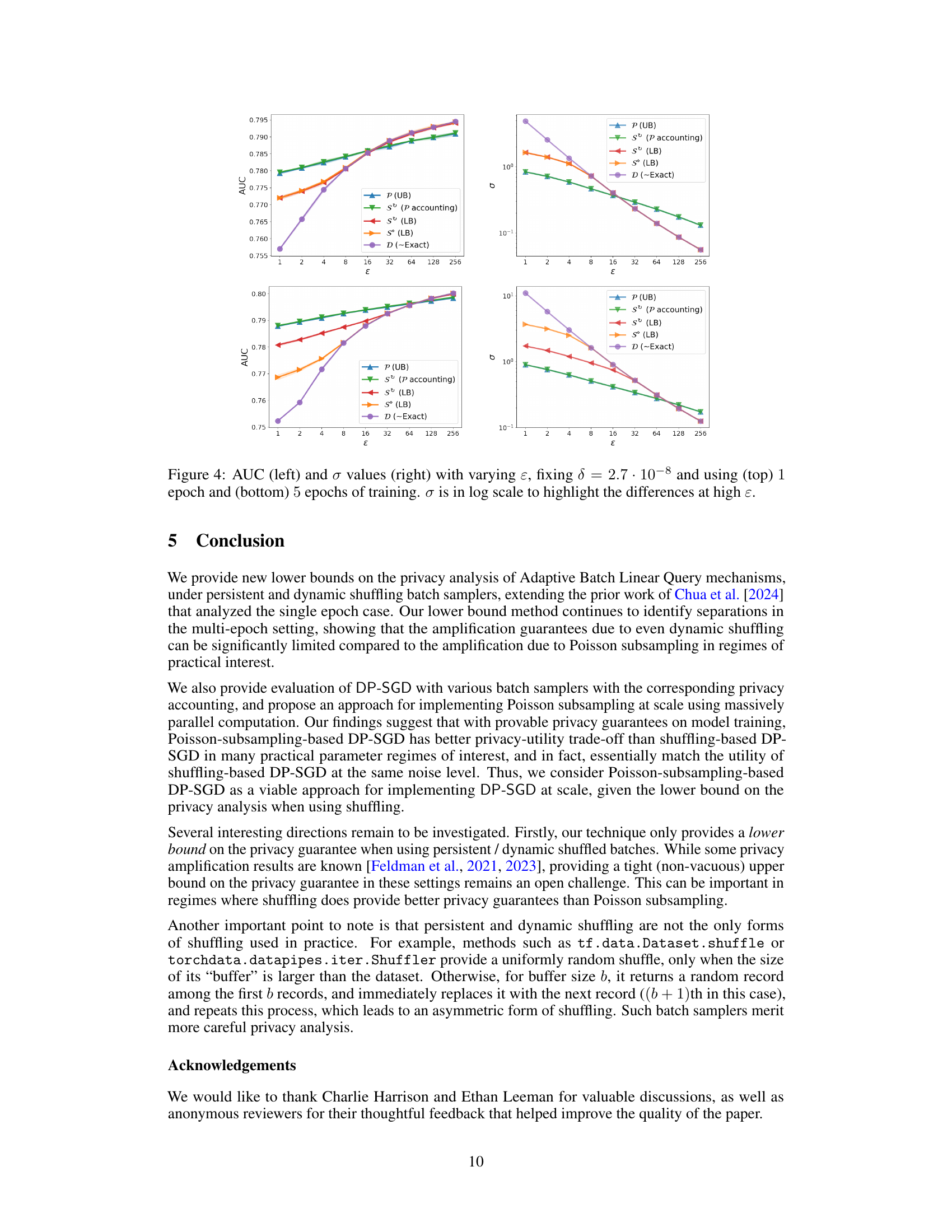

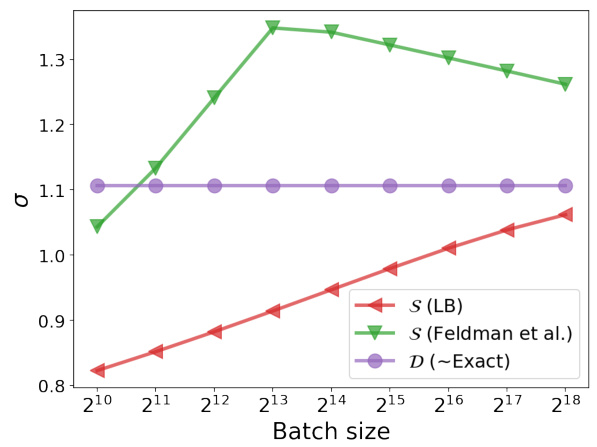

🔼 This figure shows how the noise scale (σ) required to achieve a given level of privacy (ε = 5, δ = 2.7e-8) changes with different batch sampling methods (Poisson, Dynamic Shuffling, Persistent Shuffling, Deterministic) and varying numbers of training epochs. It demonstrates that the required noise scale increases with the number of epochs for all methods, but the rate of increase differs among methods. It highlights that Poisson subsampling generally requires a lower noise scale compared to shuffling methods for achieving the same level of privacy, even when using optimistic estimates of privacy for shuffling methods.

read the caption

Figure 6: σε values with varying numbers of epochs, fixing ε = 5, δ = 2.7 · 10⁻⁸, and batch size 65536.

Full paper#