TL;DR#

Current neural algorithmic reasoning predominantly uses supervised learning, feeding one problem instance at a time. This approach struggles with complex tasks and overlooks potential benefits from leveraging relationships between tasks. The limited access to information during reasoning hinders performance.

This paper introduces an innovative “open-book” learning framework, providing the network with access to the entire training dataset during reasoning. This allows the network to aggregate information from various instances, enhancing its reasoning capabilities. Experiments show significant improvements over traditional methods on the CLRS benchmark. The attention mechanism used further provides valuable insights into task relationships, which can lead to improved multi-task training strategies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel open-book learning framework for neural algorithmic reasoning, a significant advancement in the field. It addresses limitations of existing supervised learning approaches by allowing the network to access and utilize all training instances during both training and testing. The work demonstrates improved neural reasoning capabilities on a challenging benchmark and offers insights into inherent relationships among various algorithmic tasks, paving the way for better multi-task learning strategies and more robust and interpretable AI models.

Visual Insights#

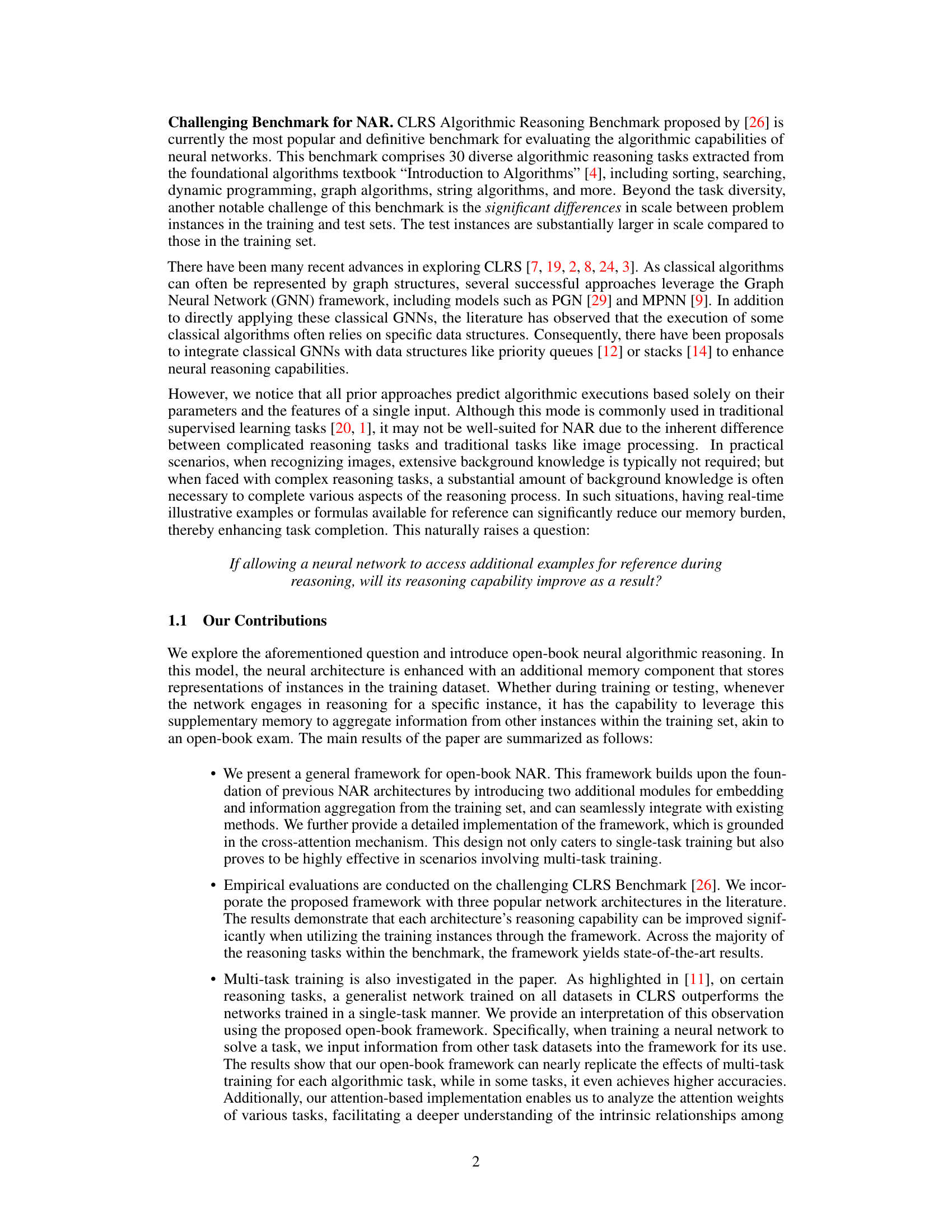

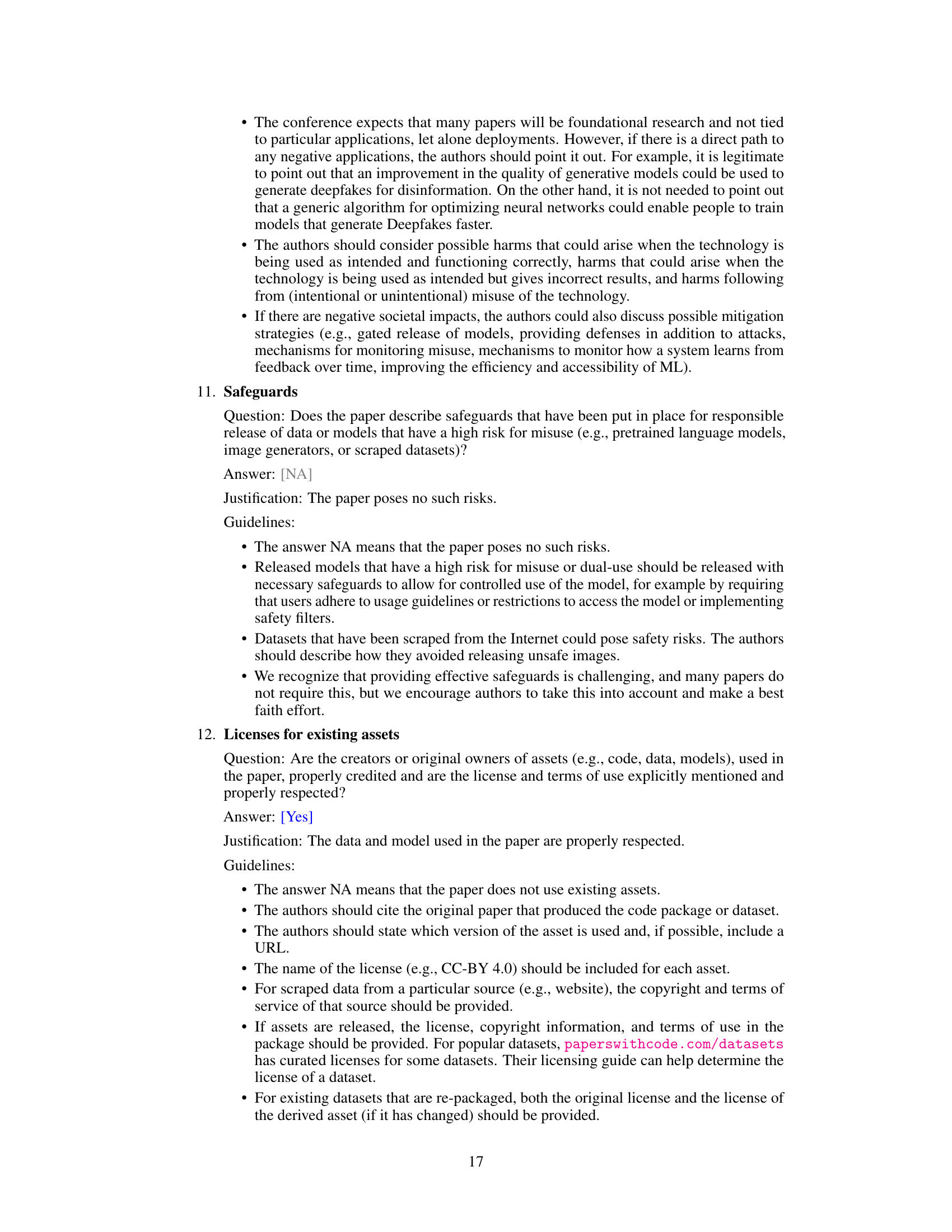

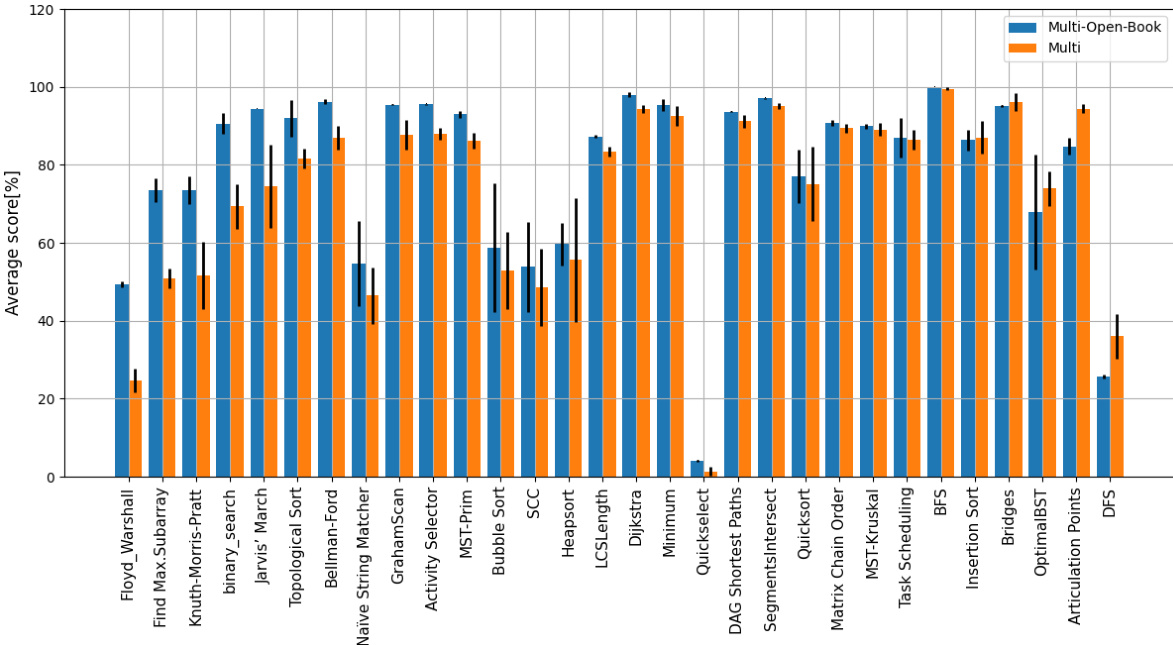

🔼 The figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed open-book neural algorithmic reasoning framework. The framework enhances standard encoder-processor-decoder models by incorporating a ‘Dataset Encoder’ and an ‘Open-Book Processor’. The Dataset Encoder creates representations (R) of the training data. During reasoning, the Open-Book Processor combines the processor’s hidden state (h^(t)) with these training data representations (R) before feeding the result (ĥ^(t)) into the decoder to predict the next step in the algorithm execution (y^(t)). This allows the model to access and utilize all training instances while reasoning for a given instance, mimicking the ability to consult examples during an open-book exam.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of the open-book framework. At each reasoning step t, we simultaneously input (x, y(t-1)) and instances from the training set T, yielding y(t).

🔼 This table summarizes the performance of the proposed open-book framework on the CLRS benchmark. It compares the best results obtained by three existing architectures (after incorporating the open-book framework) against the previous state-of-the-art results from four other methods (Memnet, PGN, MPNN, and NPQ). The results are grouped by task category within the benchmark and show significant improvements using the open-book method.

read the caption

Table 1: The summary of our results on each task category in CLRS. The best-performing results in each row are highlighted in bold. To save space, we use the column 'Prior Best' to denote the best results among four existing approaches: Memnet [26], PGN [26], MPNN [26], and NPQ [12], and the column 'Ours' to denote the best results achieved by applying the open-book framework to the three existing architectures.

In-depth insights#

Open-Book NAR#

The concept of “Open-Book NAR” (Neural Algorithmic Reasoning) presents a fascinating shift in the paradigm. Instead of relying solely on the input instance, it introduces an external knowledge base—a repository of previously seen examples from the training dataset. This allows the model to reference relevant past experiences during inference, significantly enhancing its reasoning capabilities, similar to a human having access to reference materials during an exam. The key benefit is an improved ability to handle complex reasoning tasks, where background knowledge is crucial. It challenges the limitations of traditional NAR approaches that solely rely on memorization of individual training instances. This open-book framework is particularly valuable when the test instances are significantly larger or more complex than those encountered during training, a common challenge in algorithmic reasoning benchmarks like CLRS. Furthermore, the use of attention mechanisms within this framework offers insights into the relationships between different algorithmic tasks, potentially leading to more efficient and interpretable multi-task learning strategies. The attention weights provide a valuable tool to uncover inherent connections and dependencies among diverse problems. The approach is not without limitations though; careful consideration must be given to the effective integration of information from the memory component, and how this might inadvertently harm performance in certain scenarios. Overall, Open-Book NAR represents a substantial advancement, introducing a novel approach that leverages the power of external knowledge for enhanced reasoning performance.

Attention Mechanism#

The paper uses an attention mechanism to enable the neural network to focus on relevant parts of the training dataset when reasoning about a specific task. This is achieved by allowing the network to aggregate information from training instances of other tasks in an attention-based manner. This ‘open-book’ approach, where the network can access all training data during both training and inference, allows the model to leverage previously learned knowledge and contextual information. The attention mechanism is crucial in determining which training examples are most relevant to the current task, offering interpretability by revealing the relationships between different tasks. The attention weights highlight the importance of various tasks in solving a given problem, offering valuable insights into the inherent relationships between algorithmic tasks. Further study of these weights could lead to a deeper understanding of task interdependencies and potentially improved multi-task learning strategies. The effectiveness of this attention mechanism is empirically validated on the CLRS benchmark, demonstrating improvements across diverse algorithmic tasks.

Multi-task Training#

Multi-task learning (MTL) in the context of neural algorithmic reasoning (NAR) aims to improve the model’s ability to solve diverse algorithmic tasks by training it on multiple tasks simultaneously. The core idea is that learning shared representations across tasks can help improve generalization and performance on individual tasks. This is particularly relevant for NAR, where tasks often share underlying structural similarities or require similar reasoning steps. However, MTL in NAR presents challenges, such as negative transfer (where learning one task hinders performance on another) and increased computational cost. Open-book approaches, which allow the network access to a broader knowledge base during both training and testing, can alleviate some of these challenges. By providing relevant examples from other tasks, open-book MTL can mitigate negative transfer and enhance performance. The effectiveness of MTL in NAR depends on task relatedness; similar tasks benefit more from shared learning. Advanced techniques like attention mechanisms can further refine MTL by selectively focusing on relevant information from related tasks, improving interpretability and performance.

Interpretable Results#

The concept of “Interpretable Results” in a research paper is crucial for establishing trust and facilitating understanding. It necessitates a clear presentation of findings in a way that is easily grasped by the reader, regardless of their specialized knowledge. This includes avoiding jargon, using clear and concise language, and effectively visualizing data through tables, charts, or other visual aids. Transparency is key; methods and limitations should be explicitly stated to allow for critical evaluation. Providing a thorough explanation of how results were obtained and linking them back to the research questions is also vital. Furthermore, the interpretation should highlight the significance of the findings, connecting them to existing research and outlining the potential implications for the field. Simply showing results is insufficient; a compelling narrative is needed to highlight their contribution and impact. Successful interpretability fosters collaboration, reproducibility, and broader dissemination of research outcomes.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore more effective open-book framework implementations. While the current approach improves reasoning capabilities for many tasks, some show counterproductive effects. Refining the architecture to ensure consistent performance enhancement across all tasks is crucial. Investigating alternative attention mechanisms or information aggregation strategies beyond the current attention-based method could yield significant improvements. Furthermore, exploring the integration of open-book learning with other neural algorithmic reasoning techniques, such as those incorporating specific data structures or causal regularisation, is a promising avenue for increased accuracy and interpretability. Finally, a deeper understanding of the inherent relationships between algorithmic tasks, as revealed through the attention weights, could inform the development of more efficient and robust multi-task training strategies.

More visual insights#

More on figures

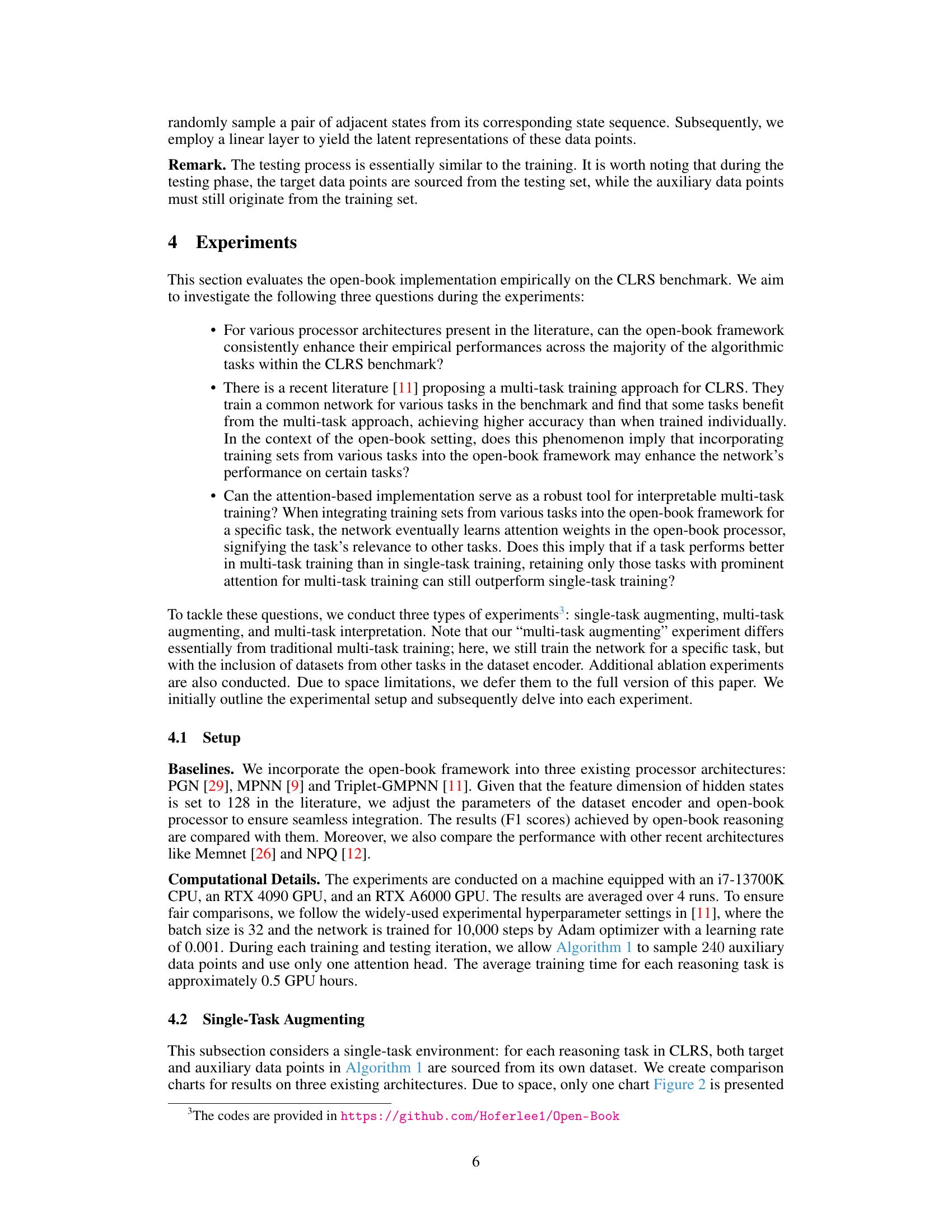

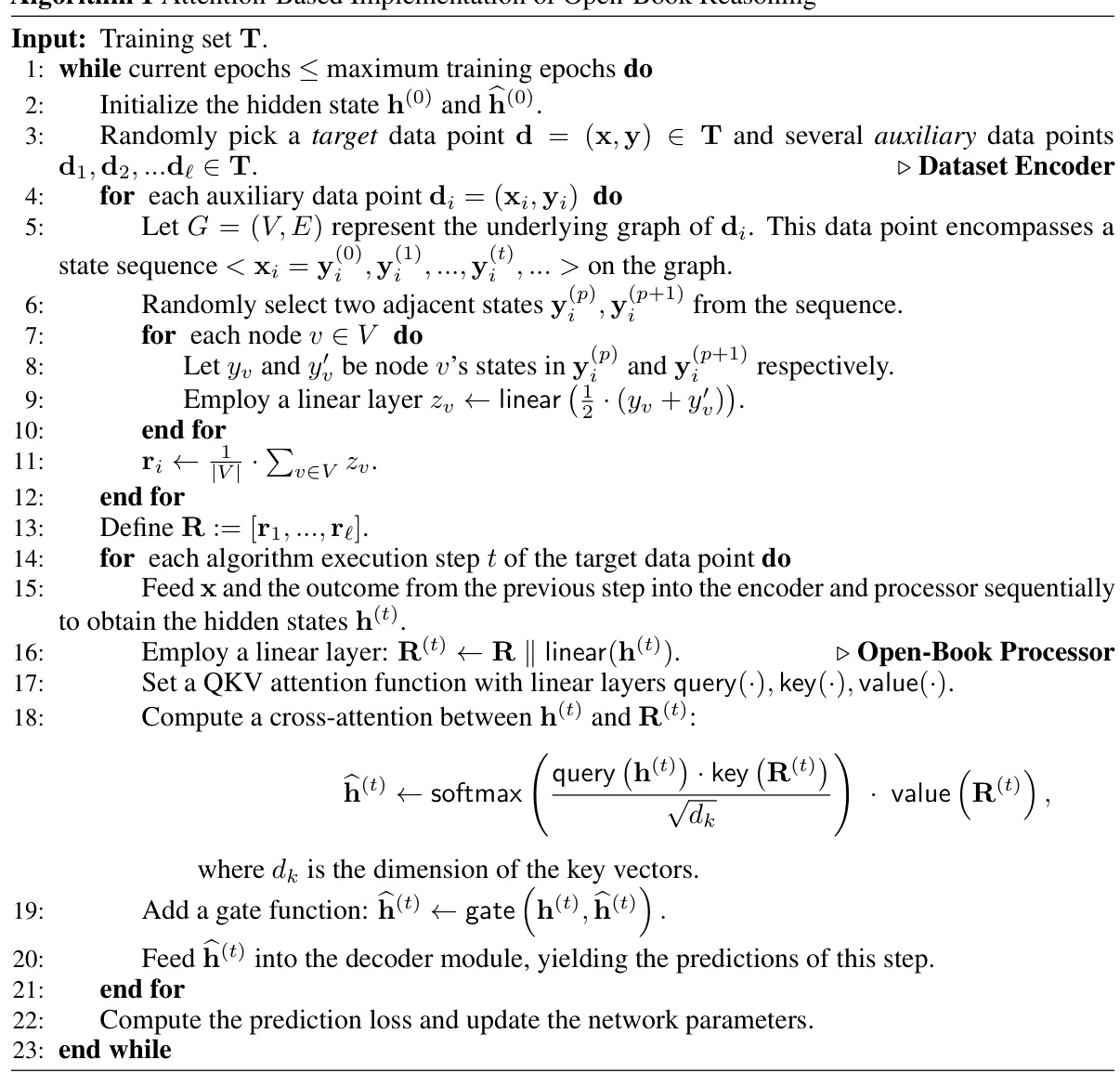

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the MPNN architecture before and after integrating the open-book framework. The x-axis lists the 30 algorithmic tasks from the CLRS benchmark, ordered from the largest to smallest improvement in performance after adding the open-book framework. The y-axis represents the average score (likely F1-score) achieved on each task. The blue bars show the performance with the open-book framework, and the orange bars represent the performance without it. Error bars are included to indicate the variability in performance across multiple runs.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of the MPNN architecture's performance before and after augmentation with the open-book framework. The 30 tasks are arranged in descending order of improvement magnitude.

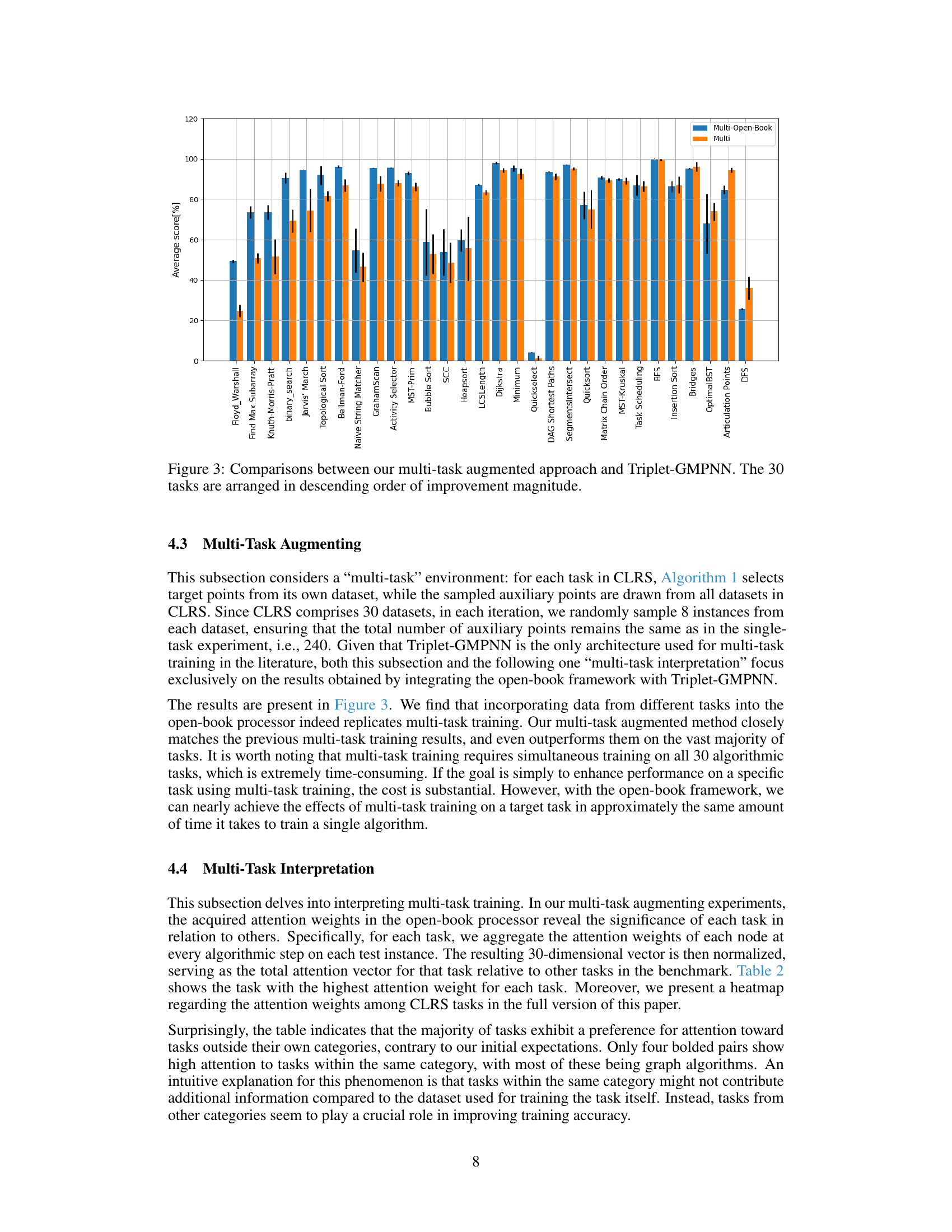

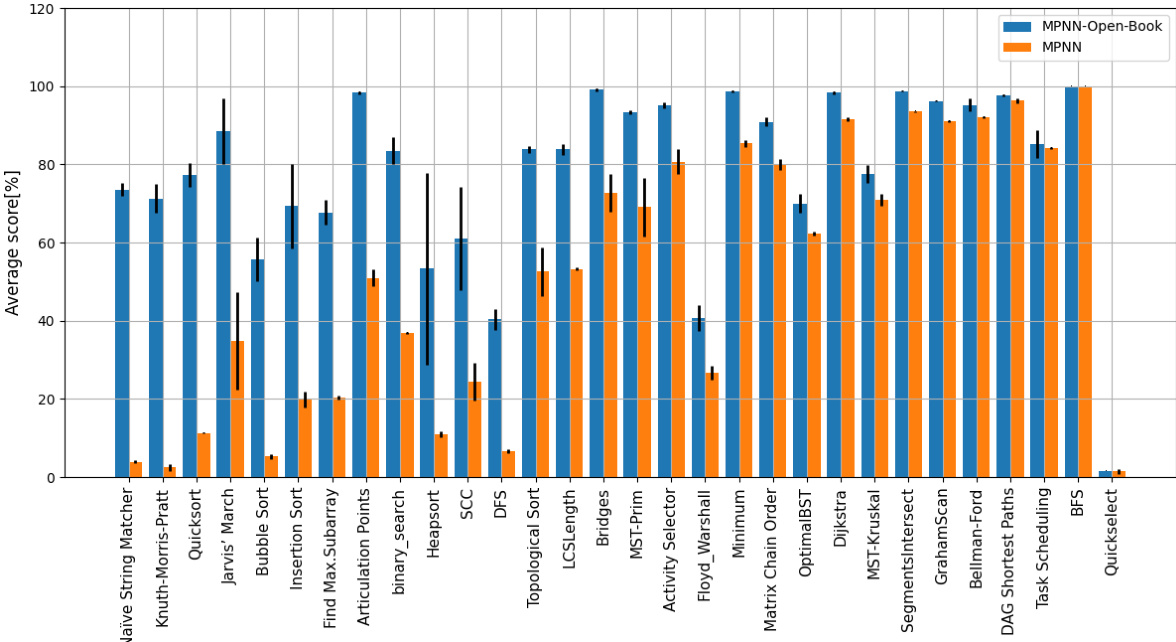

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed multi-task augmented approach with the Triplet-GMPNN baseline on 30 algorithmic reasoning tasks from the CLRS benchmark. The tasks are sorted by the magnitude of performance improvement achieved by the proposed approach, showcasing how significantly the proposed method enhances performance across a variety of tasks.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparisons between our multi-task augmented approach and Triplet-GMPNN. The 30 tasks are arranged in descending order of improvement magnitude.

More on tables

🔼 This table summarizes the performance of the proposed open-book framework on the CLRS benchmark across different task categories. It compares the best results achieved by three existing architectures (with the open-book framework applied) against the best results from four previous state-of-the-art methods (Memnet, PGN, MPNN, and NPQ). The ‘Prior Best’ column shows the best previously reported results, while the ‘Ours’ column shows the best results obtained using the open-book method.

read the caption

Table 1: The summary of our results on each task category in CLRS. The best-performing results in each row are highlighted in bold. To save space, we use the column 'Prior Best' to denote the best results among four existing approaches: Memnet [26], PGN [26], MPNN [26], and NPQ [12], and the column 'Ours' to denote the best results achieved by applying the open-book framework to the three existing architectures.

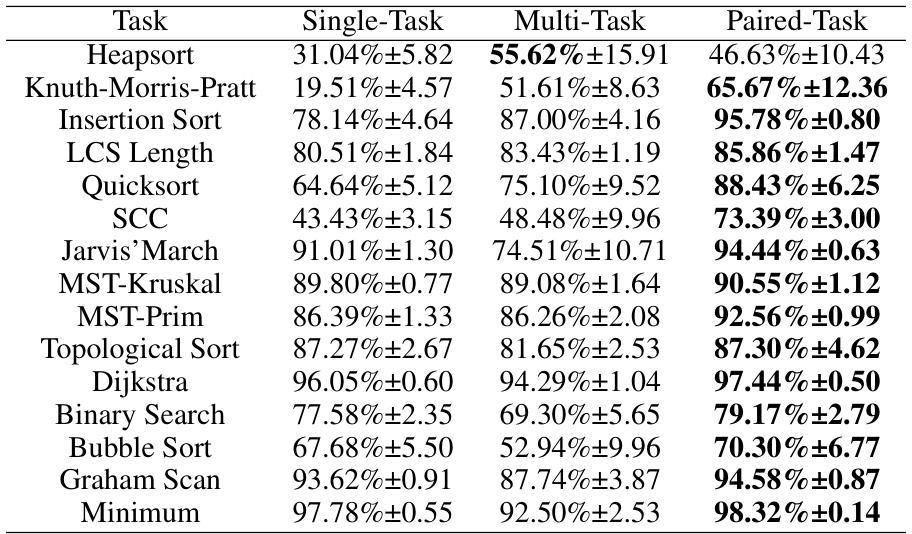

🔼 This table presents the results of a multi-task interpretation experiment. For each algorithmic task in the CLRS benchmark, the table shows the task from other categories that had the highest attention weight when solving the target task using the open-book framework. This highlights which other tasks were most influential in the open-book processor when solving each specific task. The use of bold text indicates when the most influential task belonged to the same category as the target task.

read the caption

Table 2: For each target (task), we show the task with the highest attention weight among other tasks in column “Auxiliary”. We use bold text to indicate when the paired tasks belong to the same algorithmic category.

🔼 This table summarizes the performance of the open-book framework on the CLRS benchmark, comparing it to prior state-of-the-art methods. It shows the best performance achieved by each of the three architectures used in the paper (Triplet-GMPNN, PGN, and MPNN) after incorporating the open-book framework, categorized by task type (Graphs, Geometry, Strings, Dynamic Programming, Divide and Conquer, Greedy, Search, Sorting). The results highlight the effectiveness of the open-book approach across diverse algorithmic tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: The summary of our results on each task category in CLRS. The best-performing results in each row are highlighted in bold. To save space, we use the column 'Prior Best' to denote the best results among four existing approaches: Memnet [26], PGN [26], MPNN [26], and NPQ [12], and the column 'Ours' to denote the best results achieved by applying the open-book framework to the three existing architectures.

Full paper#