TL;DR#

Many real-world applications involve massive datasets with rare events, demanding efficient computational methods. Existing optimal subsampling techniques suffer from scale-dependency issues, leading to inefficient subsamples, especially when inactive features exist. Inappropriate scaling transformations can magnify the problem, causing inaccurate variable selection and parameter estimation. This poses significant challenges for analyzing such data.

This paper introduces a novel scale-invariant optimal subsampling method that directly addresses these limitations. It uses an adaptive lasso estimator for variable selection within the context of sparse models, providing theoretical guarantees. The method also minimizes prediction error by leveraging inverse probability weighting, leading to significantly improved estimation efficiency. Numerical experiments using simulated and real-world data confirm its superior performance over existing techniques.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers dealing with massive, imbalanced datasets common in various fields. It offers a novel scale-invariant optimal subsampling method that significantly improves estimation efficiency and variable selection, particularly relevant in sparse model settings. The theoretical guarantees and practical algorithm make it highly applicable for improving the analysis of rare events data. This work opens avenues for further research in developing more efficient and robust methods for handling high-dimensional rare event data, impacting many application domains.

Visual Insights#

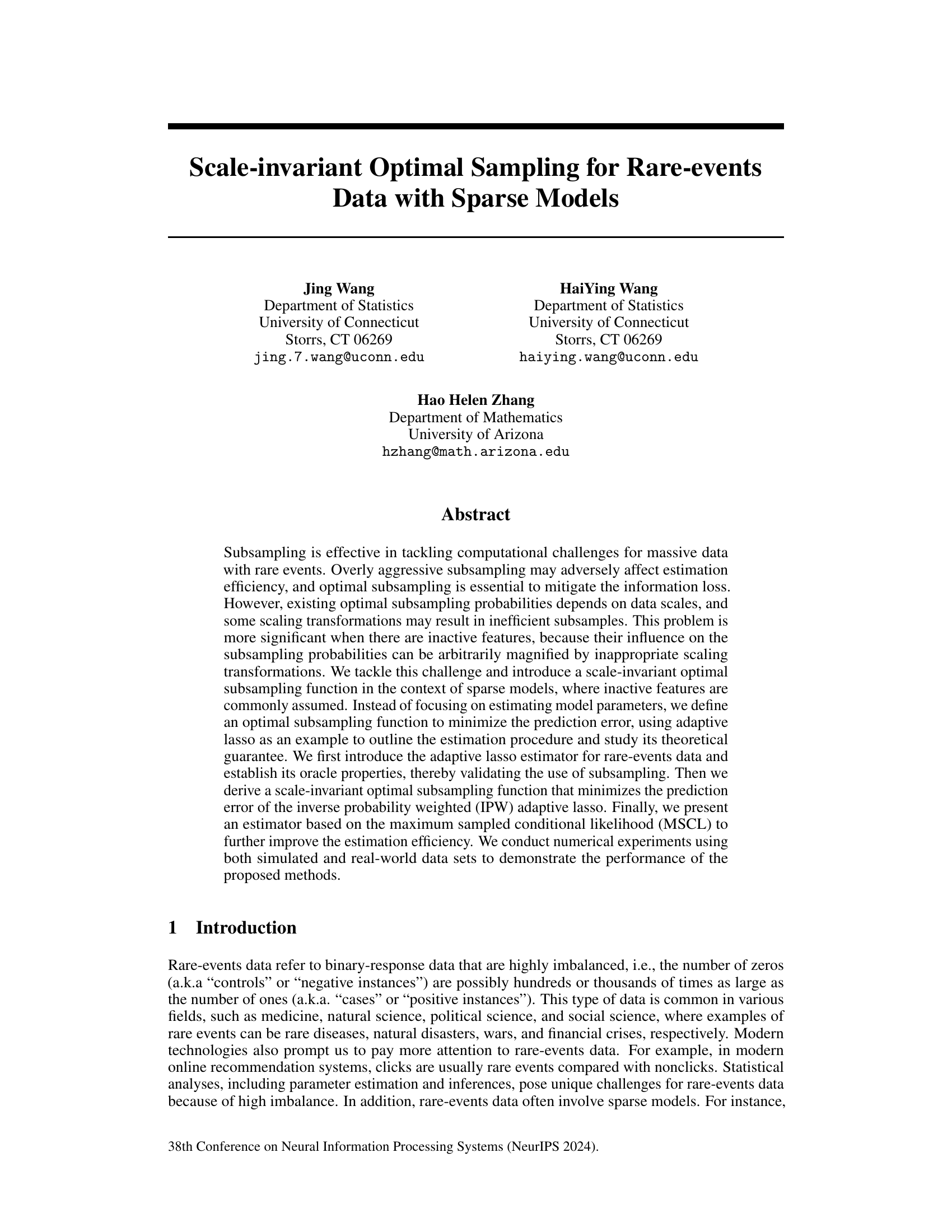

🔼 This figure shows how different scale transformations of the same model impact the prediction error of various optimal subsampling methods. It highlights the scale-dependency issue of existing methods (A-OS and L-OS), which can lead to inefficient subsamples, especially when dealing with sparse models, as in the case of (b). In contrast, the proposed scale-invariant optimal subsampling method (P-OS) remains consistent across different scales.

read the caption

Figure 1: Prediction errors with different scale transformation of the same model. (a): with non-sparse parameter (-1, -1, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01)T. (b): with sparse parameter (-1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)T.

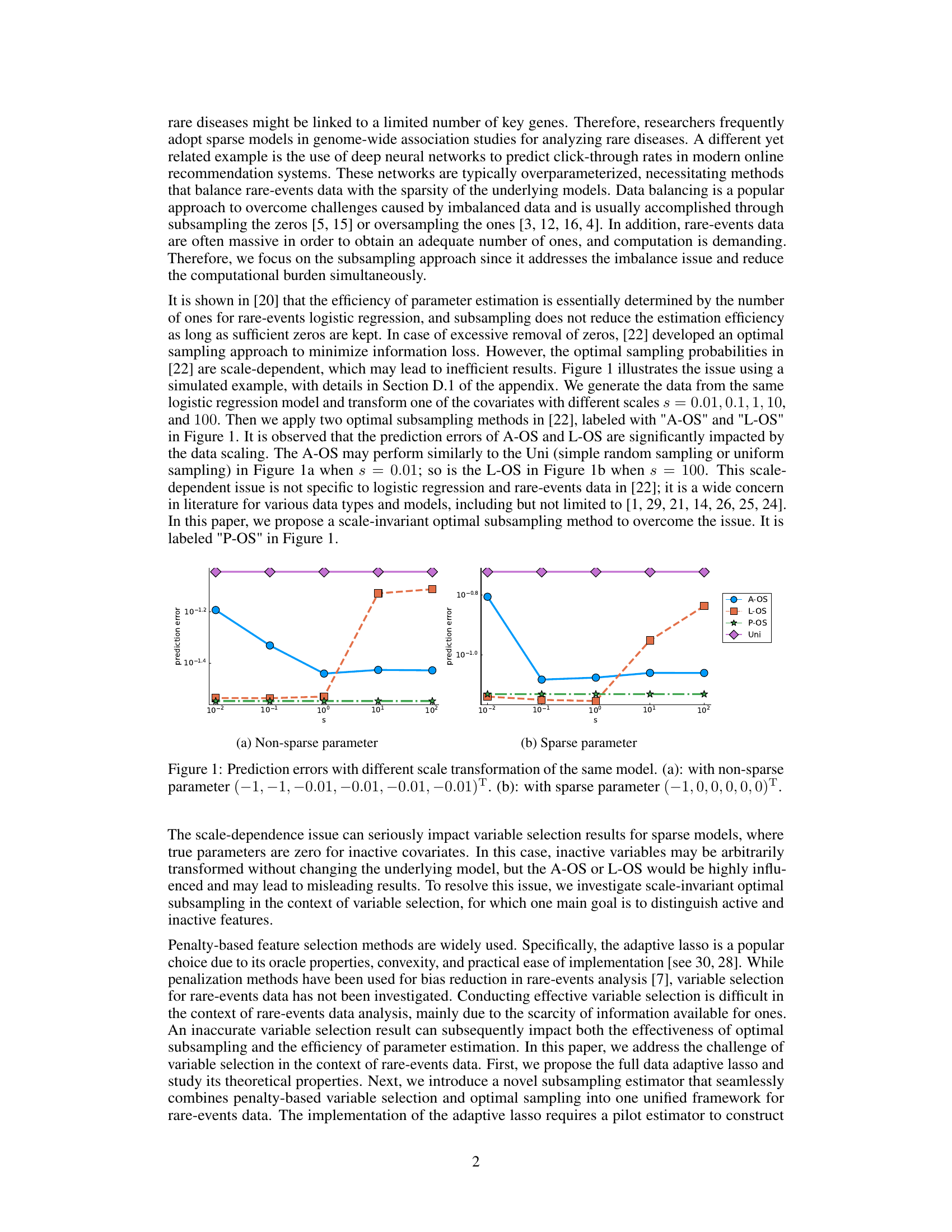

🔼 This table presents the mean numbers of selected variables for Case C of the simulation study, categorized by the sampling rate (ρ) and the method used for variable selection. The numbers in parentheses represent the corresponding standard errors. The table shows the mean number of selected variables after the first and second stages of screening, comparing uniform sampling to the three proposed optimal subsampling methods (A-OS, L-OS, and P-OS).

read the caption

Table 1: Mean number of selected variables in Case C

In-depth insights#

Scale-Invariant Sampling#

Scale-invariant sampling addresses a critical limitation in traditional subsampling methods for rare events data, where the sampling probabilities are often sensitive to data scaling. This dependence can lead to inefficient subsamples and unreliable results, particularly when inactive features are present, as their influence on sampling probabilities can be arbitrarily amplified. The core idea behind scale-invariant approaches is to devise sampling probabilities that are not affected by arbitrary scaling transformations of the covariates. This is crucial for maintaining consistency in model estimation and variable selection across different data scales. The goal is to ensure that the subsample accurately reflects the underlying data distribution regardless of how the covariates are scaled. This invariance is particularly important when dealing with sparse models, where most variables have little impact, as scale-dependent methods could unduly emphasize or ignore them based solely on their scaling. Scale-invariant sampling methods often leverage functions that only depend on the ratio of relevant quantities or relative distances between data points, thus rendering the sampling scheme robust to data scaling. Developing and evaluating these methods requires careful consideration of both the theoretical properties and empirical performance across various scales and data distributions. The practical application involves the selection of a suitable scale-invariant function and the incorporation of this into the overall subsampling strategy to guarantee a reliable and informative subsample.

Adaptive Lasso for Rare Events#

In the context of rare events, where one class significantly outnumbers the other, applying standard Lasso regression can be problematic. Adaptive Lasso offers a compelling solution by leveraging a weighted penalty term, with weights inversely proportional to initial coefficient estimates. This addresses the imbalance by focusing the penalty more on less important features. For rare events, this is particularly beneficial as it helps prevent over-penalizing potentially crucial predictors that may only appear in the minority class. The adaptive nature of the penalty allows for more accurate variable selection, leading to improved model interpretability and predictive power. However, the effectiveness of Adaptive Lasso hinges on the quality of the initial coefficient estimates; inaccurate estimates can lead to biased variable selection. Therefore, careful consideration of a suitable pilot estimator is critical, especially for high-dimensional data. This is where careful implementation and potentially alternative approaches become important to mitigate potential biases or computational challenges that may arise from rare events’ inherent data sparsity.

Penalized MSCL Estimation#

The heading ‘Penalized MSCL Estimation’ suggests a method to improve the efficiency of parameter estimation in rare events data by combining the maximum sampled conditional likelihood (MSCL) approach with a penalty term. MSCL itself addresses computational challenges of large datasets by subsampling, focusing on informative data points. The addition of a penalty, likely L1 (LASSO) or L2 (Ridge), introduces sparsity into the model, encouraging variable selection by shrinking less important coefficients towards zero. This is crucial for rare events, where many features may be irrelevant. The penalized MSCL estimator balances the benefit of MSCL’s improved efficiency and the enhanced interpretability and reduced overfitting provided by regularization. Theoretical guarantees, such as oracle properties, would likely be established to ensure the estimator’s consistency and asymptotic normality, demonstrating its effectiveness. The practical implementation might involve iterative optimization algorithms, possibly requiring a pilot estimator for the penalty weights.

Computational Efficiency#

Computational efficiency is a critical concern in handling massive datasets, especially those with rare events. The authors address this by employing subsampling techniques. Scale-invariant optimal subsampling is introduced to overcome the limitations of existing methods, which are sensitive to data scaling and can lead to inefficient subsamples, particularly when inactive features are present. The proposed method aims to minimize prediction error, rather than focusing solely on parameter estimation. Adaptive Lasso is used for variable selection, enhancing efficiency by identifying and focusing on relevant variables, which reduces computational load. A two-step algorithm is presented to combine these methods efficiently: first screening with Lasso to select active variables and then refining the estimates using the more computationally intensive adaptive Lasso on a subsampled dataset. The use of MSCL (maximum sampled conditional likelihood) further improves estimation by employing more informative data points. Overall, the paper’s approach offers a significant computational advantage over full-data methods by strategically combining subsampling with variable selection in a computationally efficient way. The efficiency gains are experimentally demonstrated with simulations and real datasets.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this scale-invariant optimal subsampling work could involve extending the theoretical analysis to non-asymptotic settings, providing finite-sample guarantees for the proposed estimators. This is crucial for practical applications, especially when dealing with high-dimensional data where asymptotic results may not be reliable. Another important avenue is exploring alternative pilot estimators beyond the adaptive lasso. Investigating the performance with other variable selection methods, such as SCAD or MCP, could reveal valuable insights into the robustness and efficiency of the proposed framework under various scenarios. Furthermore, research into the impact of model misspecification on the proposed methodology is warranted. Robustness checks against model violations and potential strategies for handling these situations are necessary to broaden the applicability of the proposed approach. Finally, developing more efficient algorithms for large-scale datasets and exploring parallel computing strategies for quicker processing would greatly enhance the practical use of these methods for real-world problems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

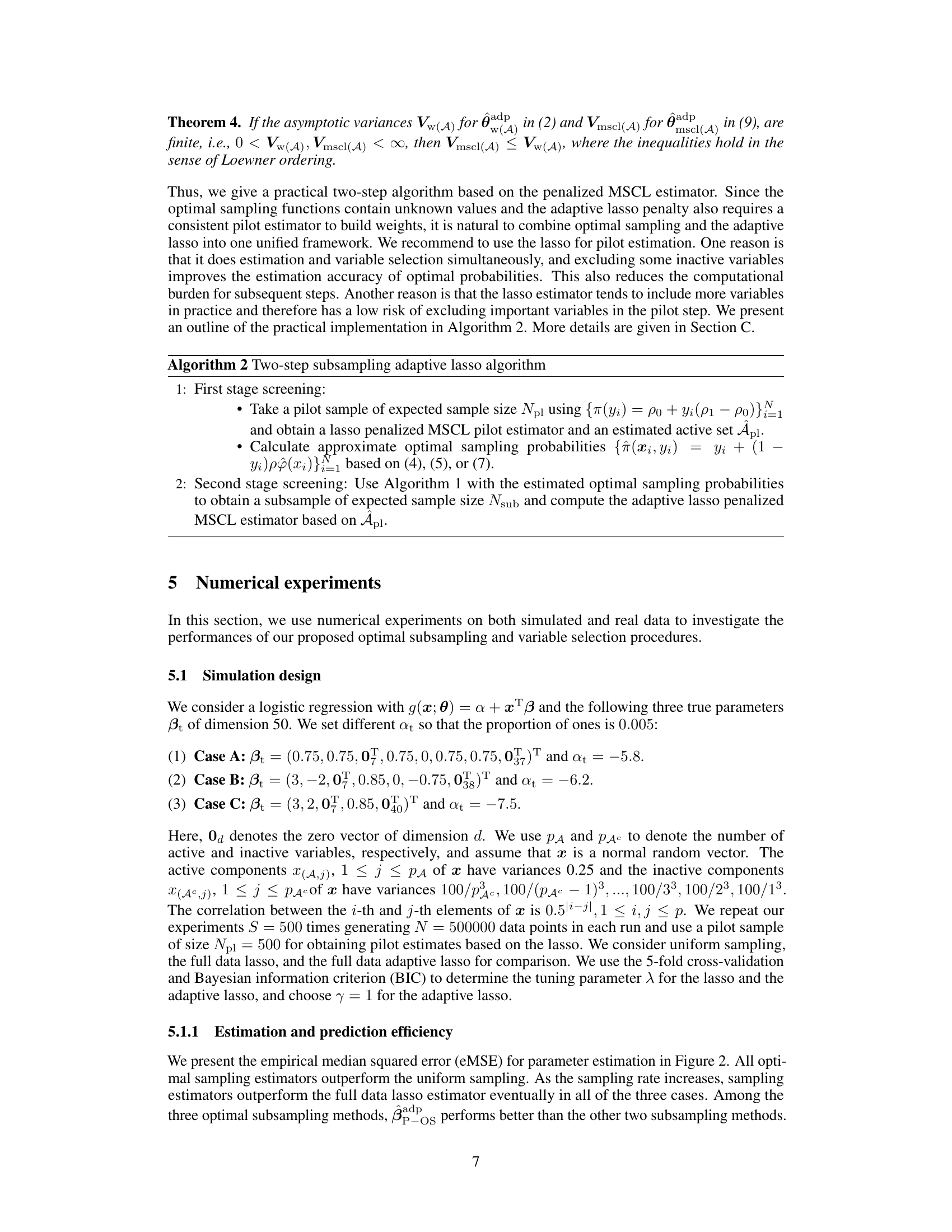

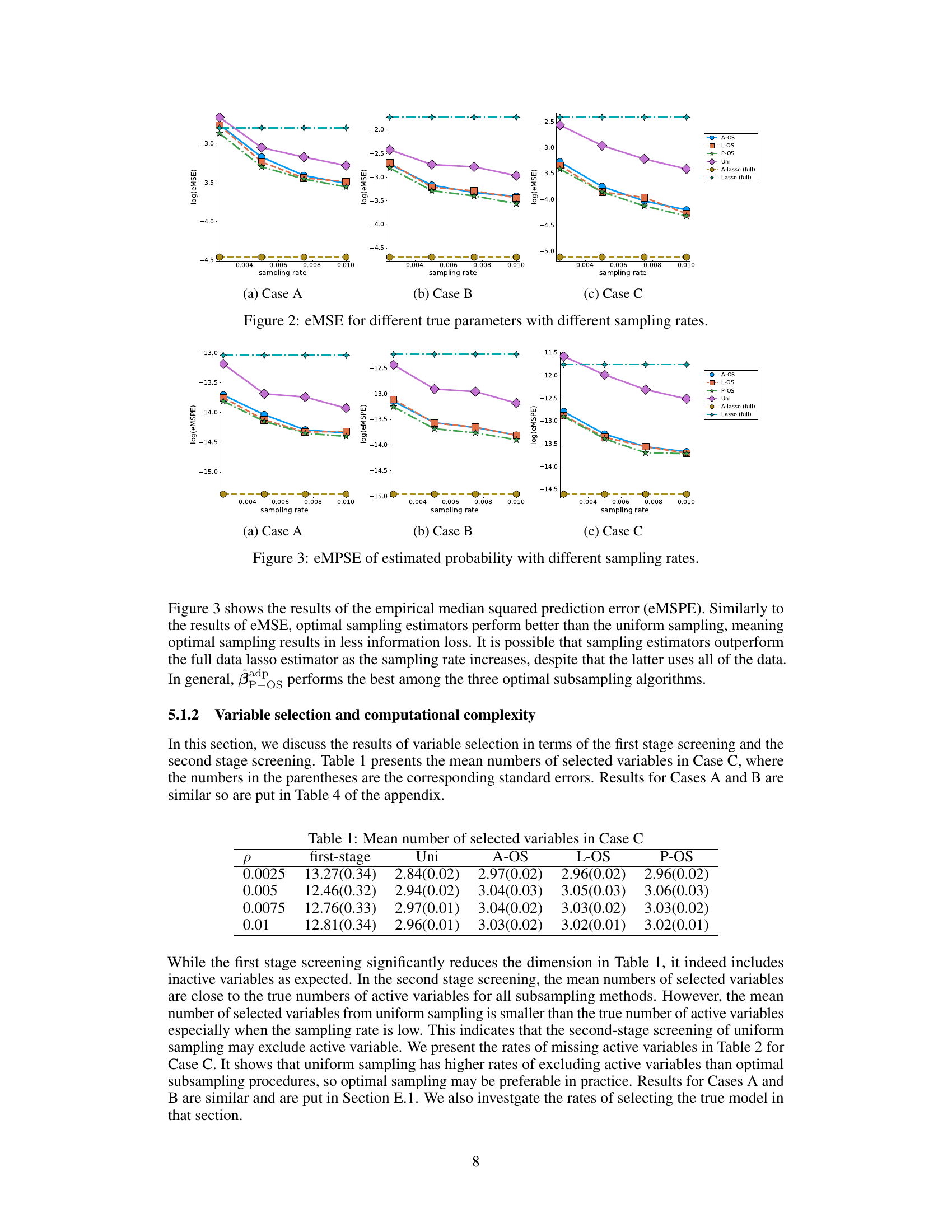

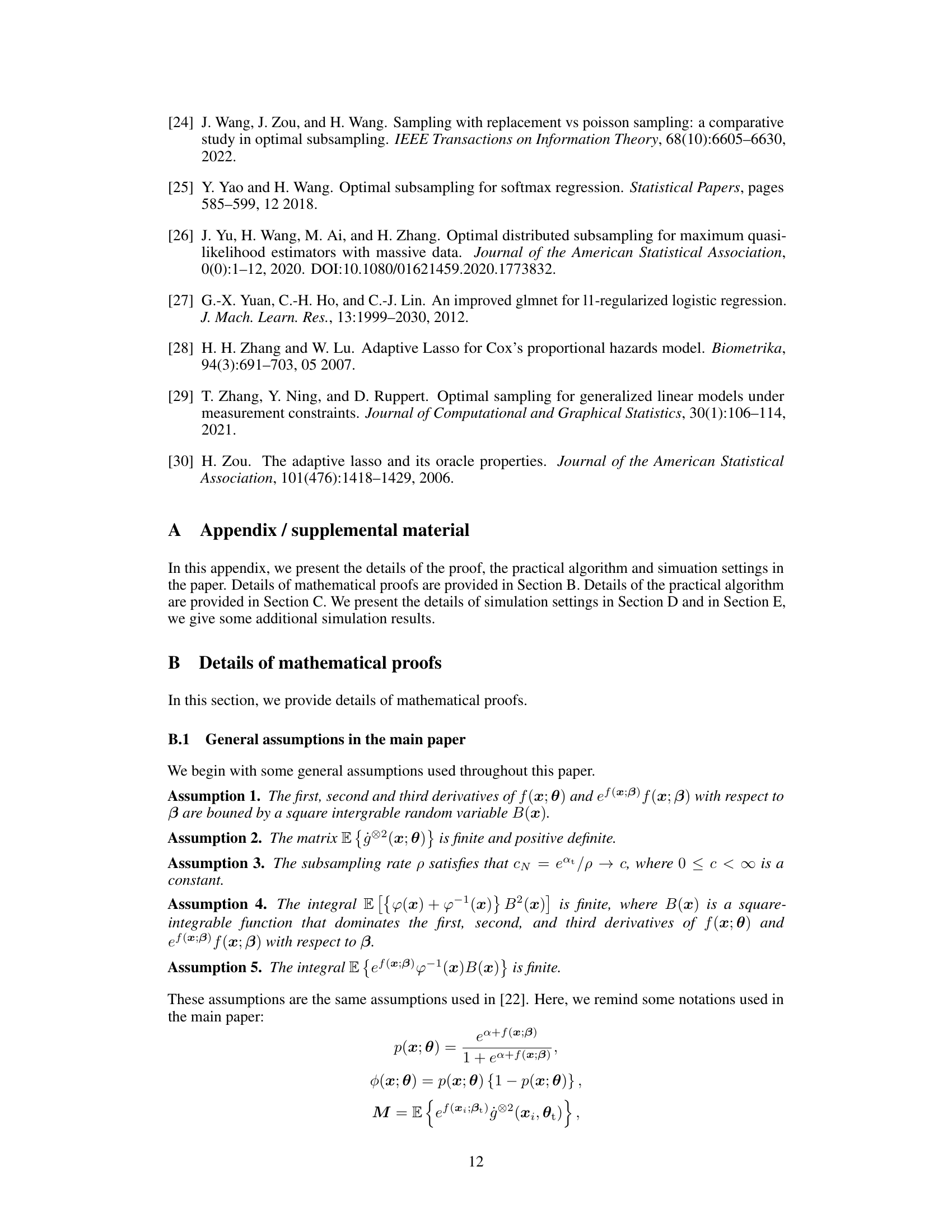

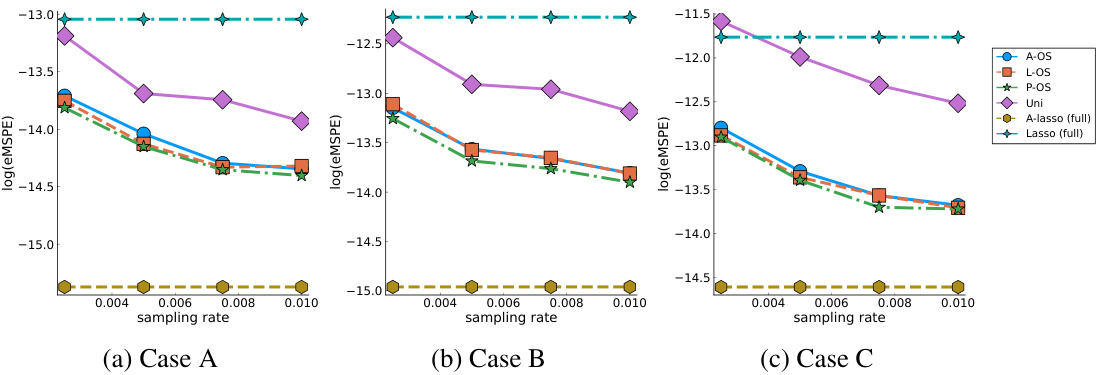

🔼 This figure compares the empirical median squared error (eMSE) of parameter estimation for three different parameter settings (Cases A, B, and C) across various sampling rates. Each case represents a different sparsity pattern of the true parameters. The x-axis shows the sampling rate, while the y-axis shows the log of eMSE. The figure shows the performance of different subsampling methods (A-OS, L-OS, P-OS, Uni, Adaptive Lasso, Lasso) across different sampling rates and parameter settings. It illustrates how different optimal subsampling methods and the full data Lasso and adaptive Lasso perform with respect to the sampling rate.

read the caption

Figure 2: eMSE for different true parameters with different sampling rates.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of data scaling on the performance of two optimal subsampling methods (A-OS and L-OS) compared to uniform sampling (Uni) and the proposed scale-invariant optimal subsampling method (P-OS). The prediction error is plotted against different data scales (s) for both a non-sparse and sparse parameter setting. The results highlight the scale-dependence issue of existing optimal subsampling methods and showcase the advantage of the proposed scale-invariant approach.

read the caption

Figure 1: Prediction errors with different scale transformation of the same model. (a): with non-sparse parameter (-1, -1, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01)Т. (b): with sparse parameter (-1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)T.

🔼 This figure illustrates the scale-dependent issue of existing optimal subsampling methods. Two optimal subsampling methods (A-OS and L-OS) and a uniform sampling method (Uni) are compared against a proposed scale-invariant method (P-OS). The x-axis represents different scales (s) applied to a covariate, showing how prediction error varies significantly across methods with scale changes, while the proposed P-OS method remains relatively stable. Two scenarios are shown: one with non-sparse parameters and another with sparse parameters, highlighting the impact of feature inactivity on the issue.

read the caption

Figure 1: Prediction errors with different scale transformation of the same model. (a): with non-sparse parameter (-1, -1, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01)Т. (b): with sparse parameter (-1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)T.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of data scaling on the performance of two optimal subsampling methods (A-OS and L-OS) from the literature, compared to uniform sampling (Uni). It shows that the prediction error varies significantly depending on the scale transformation applied to the data, highlighting the scale-dependent nature of these methods. The proposed scale-invariant method (P-OS) is shown to be robust to scaling transformations, demonstrating its advantage over existing techniques, especially in scenarios with sparse models.

read the caption

Figure 1: Prediction errors with different scale transformation of the same model. (a): with non-sparse parameter (-1, -1, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01)T. (b): with sparse parameter (-1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)T.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of data scaling on the performance of two optimal subsampling methods (A-OS and L-OS) compared to uniform sampling (Uni) and the proposed scale-invariant method (P-OS). The left panel shows results with a non-sparse model, and the right panel shows results with a sparse model. The x-axis represents the scaling factor (s) applied to one of the covariates. The y-axis represents the prediction error. The figure illustrates that A-OS and L-OS are highly sensitive to data scaling, while P-OS is more robust and maintains consistent performance across different scales.

read the caption

Figure 1: Prediction errors with different scale transformation of the same model. (a): with non-sparse parameter (-1, -1, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01, -0.01)T. (b): with sparse parameter (-1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0)T.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the mean numbers of selected variables in Case C of the simulation study. The numbers in the parentheses are the corresponding standard errors. It shows the results of variable selection in terms of first-stage screening (using a pilot sample to reduce the number of variables) and second-stage screening (using the adaptive lasso with a scale-invariant optimal subsampling method) with various sampling rates (ρ). The results for Cases A and B are similar and presented in the appendix.

read the caption

Table 1: Mean number of selected variables in Case C

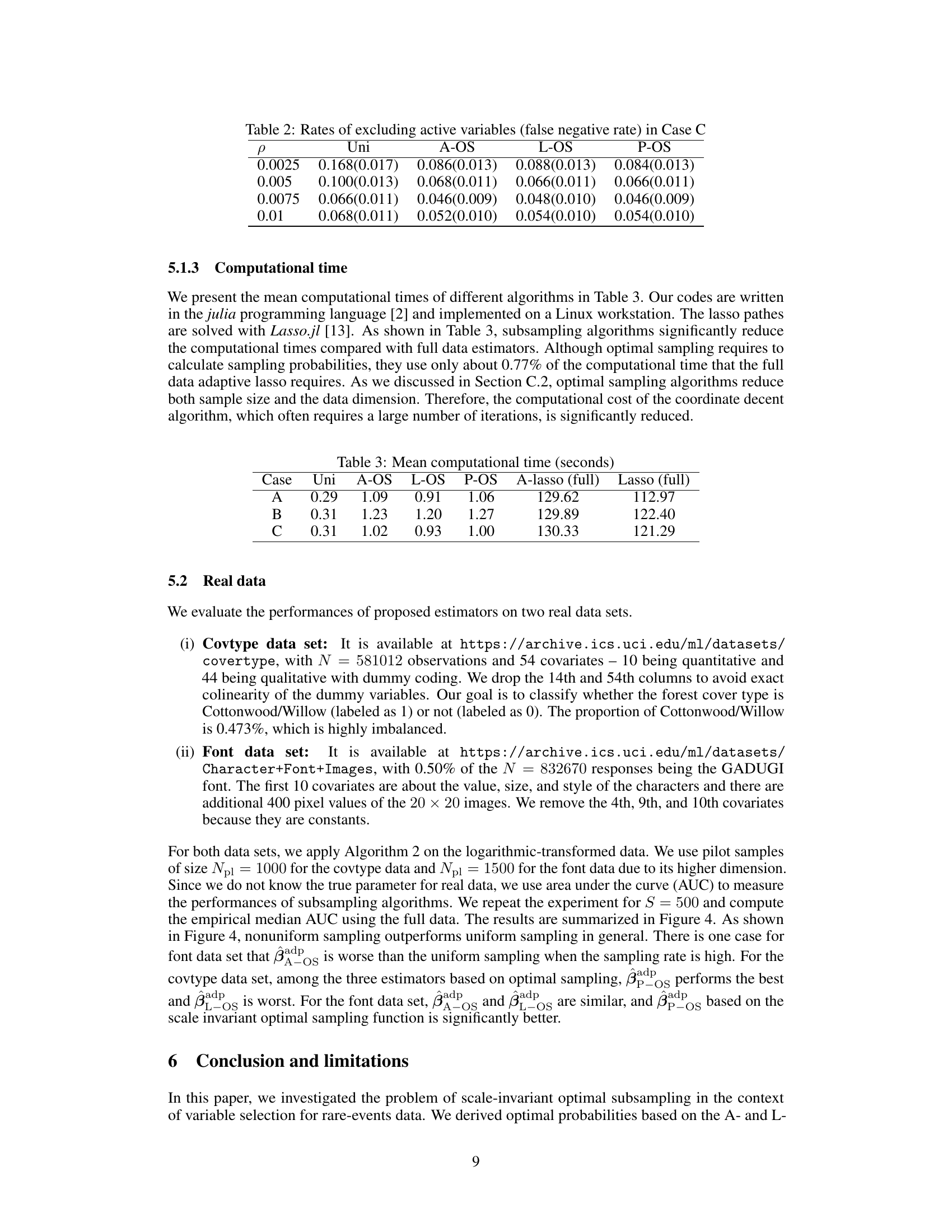

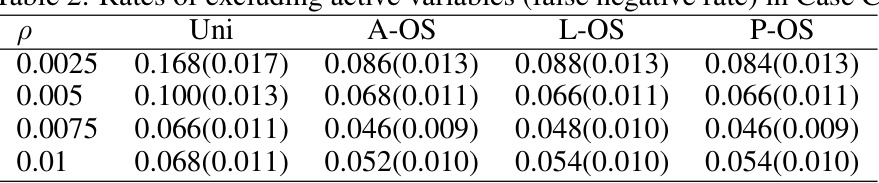

🔼 This table presents the rates of excluding active variables (false negative rates) for different sampling rates (ρ) in Case C of the simulation study. It compares the performance of uniform sampling (Uni) against three optimal subsampling methods: A-OS, L-OS, and P-OS. Lower rates indicate better performance in correctly identifying active variables.

read the caption

Table 2: Rates of excluding active variables (false negative rate) in Case C

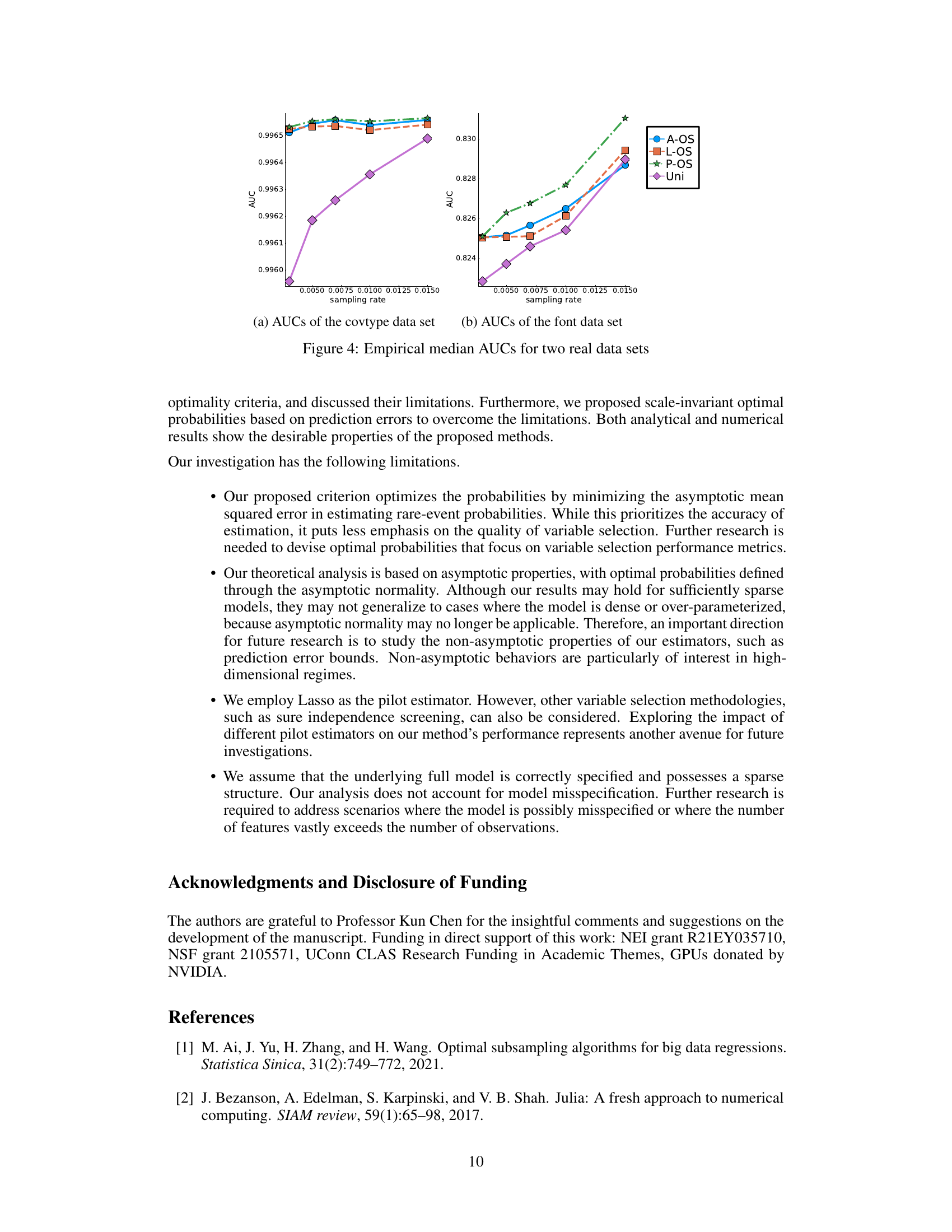

🔼 This table presents the average computation time in seconds for different methods (uniform sampling, A-OS, L-OS, P-OS, adaptive Lasso, and Lasso) across three different simulation cases (A, B, and C). The results highlight the significant reduction in computation time achieved by the proposed optimal subsampling methods compared to the full-data Lasso methods. The table showcases the efficiency gains of the proposed methods.

read the caption

Table 3: Mean computational time (seconds)

🔼 This table shows the average number of selected variables after applying different subsampling methods (Uniform, A-OS, L-OS, P-OS) and the full data Lasso and adaptive Lasso in Case C of the simulation study. The results are categorized by different sampling rates (ρ) and separated into the first and second screening stages. It demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed P-OS method in selecting variables compared to other methods and illustrates the impact of the first-stage screening in reducing dimensionality.

read the caption

Table 1: Mean number of selected variables in Case C

🔼 This table presents the false negative rates, which are the rates of excluding active variables, for different sampling methods (Uni, A-OS, L-OS, P-OS) across various sampling rates (ρ = 0.0025, 0.005, 0.0075, 0.01) and two cases (Case A and Case B) in the simulation study. Each entry shows the mean and standard deviation of the false negative rate, calculated over 500 repetitions.

read the caption

Table 5: Rates of excluding active variables (false negative rate) in Case A and Case B

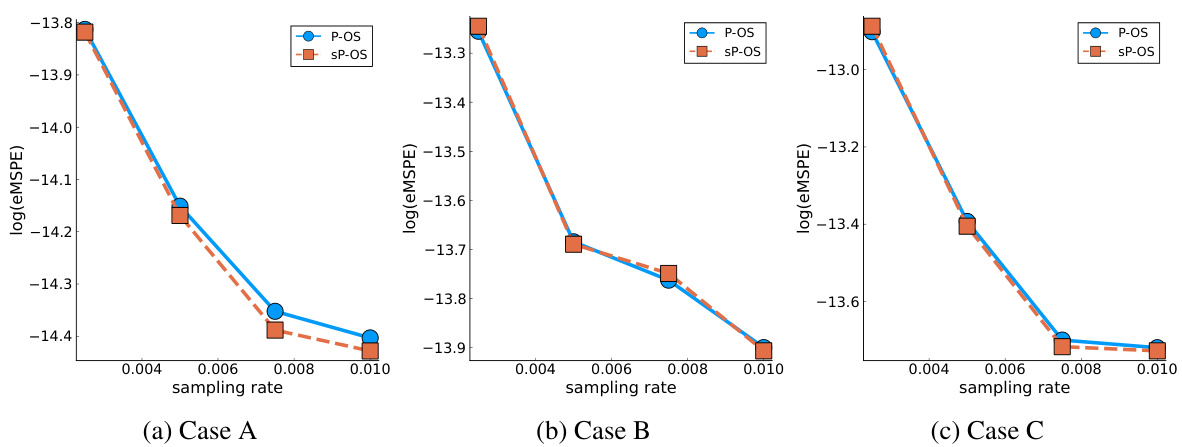

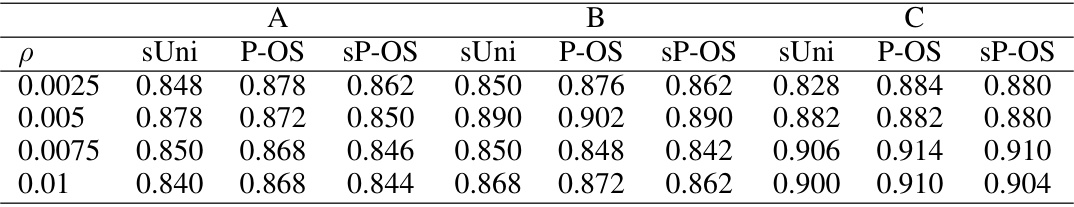

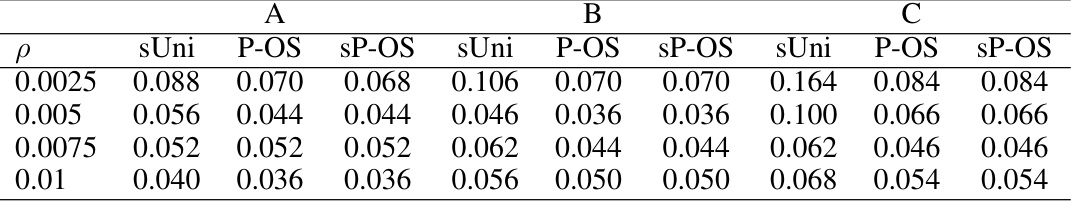

🔼 This table presents the results of the rate of selecting the true model for different sampling methods (Uni, A-OS, L-OS, P-OS) and different sampling rates (ρ) across three different cases (A, B, C). Each case represents a different true parameter setting in the simulation study. The values in the table are the mean rates of selecting the true model along with their standard errors, indicating the variability in the rate across multiple simulations.

read the caption

Table 7: Rates of selecting true models

🔼 This table presents the results of the rate of selecting true models under different sampling rates (ρ) for three different cases (A, B, C) of parameters. For each case and sampling rate, it shows the rates achieved by uniform sampling (sUni), the proposed P-optimality sampling (P-OS), and the standardized P-optimality sampling (sP-OS). The results are based on 500 Monte Carlo replications and show the performance of different sampling strategies in selecting the correct model.

read the caption

Table 7: Rates of selecting true models

🔼 This table presents the false negative rates, showing the proportion of times active variables were not selected in the variable selection process. It compares the results of uniform sampling against three different optimal subsampling methods (A-OS, L-OS, and P-OS) across different sampling rates (ρ) and three different simulation cases (A, B, and C). The results illustrate the relative performance of these methods in correctly identifying active variables.

read the caption

Table 8: Rates of excluding active variables (false negtive rate)

Full paper#