TL;DR#

Linear bandit algorithms are crucial in online decision-making, aiming to minimize cumulative regret over time. Existing methods like Thompson Sampling and Perturbed-History Exploration have shown strong theoretical guarantees, but linear ensemble sampling has lagged behind with suboptimal regret bounds and an impractical linear ensemble size. This has hindered its broader adoption despite empirical success.

This paper bridges this gap by proving that linear ensemble sampling achieves a state-of-the-art regret bound of Õ(d³/²√T) with a logarithmic ensemble size, matching results for top-performing randomized methods. It introduces a generalized regret analysis framework and reveals a critical relationship between linear ensemble sampling and LinPHE, which allows for deriving a new, improved regret bound for LinPHE as well. These results significantly advance our theoretical understanding of ensemble sampling and provide a more efficient algorithm for practical applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it resolves a significant gap between the theoretical understanding and practical effectiveness of linear ensemble sampling in online learning. By providing a tighter regret bound and clarifying its relationship with other algorithms, it enhances the algorithm’s applicability and opens new avenues for theoretical advancements in bandit problems and related fields.

Visual Insights#

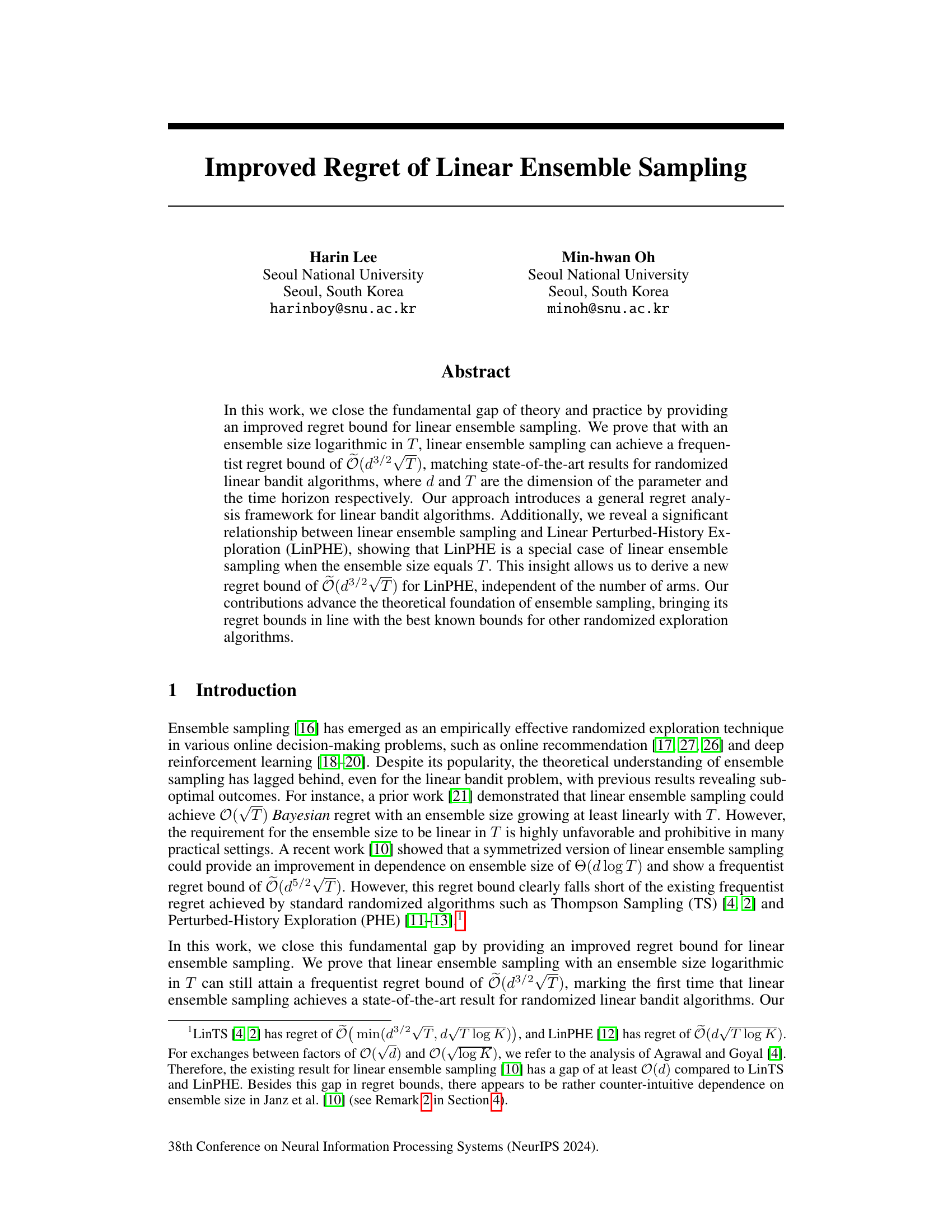

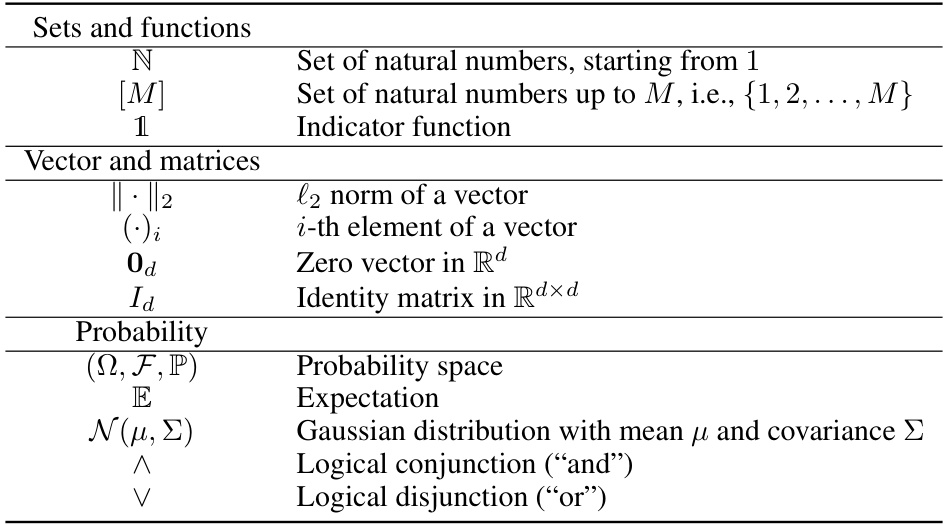

🔼 The table compares the regret bounds achieved by different linear ensemble sampling algorithms. It shows the type of regret bound (frequentist or Bayesian), the actual bound achieved, and the required ensemble size for each algorithm. The algorithms compared include Lu and Van Roy [16], Qin et al. [21], Janz et al. [10], and the current work. The table highlights the improvement in regret bound and reduction in ensemble size achieved by the current work.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regret bounds for linear ensemble sampling

In-depth insights#

Regret Bound Advance#

A regret bound advance in a machine learning context signifies a tighter, more accurate theoretical guarantee on the algorithm’s performance. It’s a crucial step because it directly reflects the algorithm’s efficiency in minimizing cumulative losses over time. Improved regret bounds often translate to better practical performance, especially in scenarios with limited data or resources. The advance might involve novel techniques to analyze the algorithm’s exploration-exploitation trade-off, sharper concentration inequalities, or a more refined understanding of the problem’s inherent complexity. A significant improvement might involve reducing the dependence on problem parameters (such as dimensionality or the number of actions) in the bound, which shows scalability. In the specific case of linear ensemble sampling, the advance could involve showing that the regret scales favorably with the ensemble size and the time horizon, even with sub-linear ensemble sizes, contrasting previous results showing suboptimal regret scaling. This demonstrates significant progress towards bridging the theory and practice of ensemble sampling methods. Ultimately, any regret bound advance is valuable as it helps researchers to develop more reliable and efficient algorithms.

LinPHE-Ensemble Link#

A hypothetical section titled ‘LinPHE-Ensemble Link’ in a research paper would likely explore the relationship between Linear Perturbed-History Exploration (LinPHE) and ensemble methods for linear bandits. It would likely establish that LinPHE is a special case of ensemble sampling under specific conditions, such as when the ensemble size equals the time horizon. This connection would provide a unifying framework, revealing how these seemingly different approaches are intrinsically related, thus enriching the theoretical understanding of both. The analysis would probably involve showing the equivalence in terms of the update rules and the resulting regret bounds, potentially highlighting that the improved regret bounds achieved for ensemble sampling also apply to LinPHE, offering a new perspective on its performance. This connection could be leveraged to derive new insights and algorithms, potentially improving the efficiency and simplifying the implementation of either technique.

General Regret Analysis#

A general regret analysis framework provides a valuable, unifying perspective on linear bandit algorithms. It transcends specific algorithm details, focusing instead on core properties like concentration and optimism. By establishing sufficient conditions for these properties, this framework delivers a regret bound applicable across diverse algorithms. This offers significant advantages: it simplifies analysis, enabling a more concise and elegant derivation of regret compared to algorithm-specific approaches. The framework’s generality allows for easier adaptation to new linear bandit algorithms or variations of existing methods, reducing redundant effort. Furthermore, this unified approach can reveal underlying relationships between seemingly disparate algorithms, highlighting connections previously obscured by algorithm-specific analyses. However, the framework’s success hinges on the ability to effectively establish the concentration and optimism conditions for a given algorithm. This requires a careful and algorithm-specific analysis, potentially limiting the extent to which the framework simplifies the overall process.

Perturbation Analysis#

Perturbation analysis, in the context of online learning algorithms, specifically linear bandits, is crucial for understanding and bounding the algorithm’s regret. The core idea is to add carefully designed noise (perturbations) to the reward signals or model parameters. This injection of randomness helps balance exploration and exploitation, enabling the algorithm to efficiently discover the optimal strategy without getting stuck in suboptimal solutions. The analysis then focuses on demonstrating that the algorithm’s performance, measured by regret, remains bounded even with the added perturbation. Different types of perturbations (e.g., Gaussian, Rademacher) lead to different analytical challenges. A key aspect is demonstrating that, despite the noise, the algorithm’s estimates converge to the true parameters at a reasonable rate and that the added noise does not excessively inflate the regret bound. Analyzing the effect of the specific perturbation distribution is paramount, particularly in establishing the algorithm’s convergence rate and establishing high-probability regret bounds. A well-executed perturbation analysis provides a strong theoretical guarantee for the algorithm’s performance and underpins the claims of optimality or near-optimality. The framework often involves concentration inequalities to manage the stochasticity introduced by the perturbations and to control the error arising from the algorithm’s estimates. Ultimately, the effectiveness of the chosen perturbation method rests on its ability to balance exploration and regret while maintaining analytical tractability.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore extending the theoretical framework beyond linear bandits to encompass more complex settings such as contextual bandits or those with non-linear reward functions. Investigating the impact of different ensemble sampling strategies and perturbation distributions, beyond those analyzed, would enhance the practical applicability of the findings. Furthermore, empirical evaluations across diverse real-world problems are crucial to validate the theoretical results and showcase the algorithm’s effectiveness in practice. A particularly promising avenue is to explore the interplay between ensemble size and regret bounds, potentially uncovering more efficient ensemble configurations. Finally, the equivalence established between linear ensemble sampling and LinPHE invites further investigation into the specific conditions under which this equivalence holds and its implications for algorithm design and analysis.

More visual insights#

More on tables

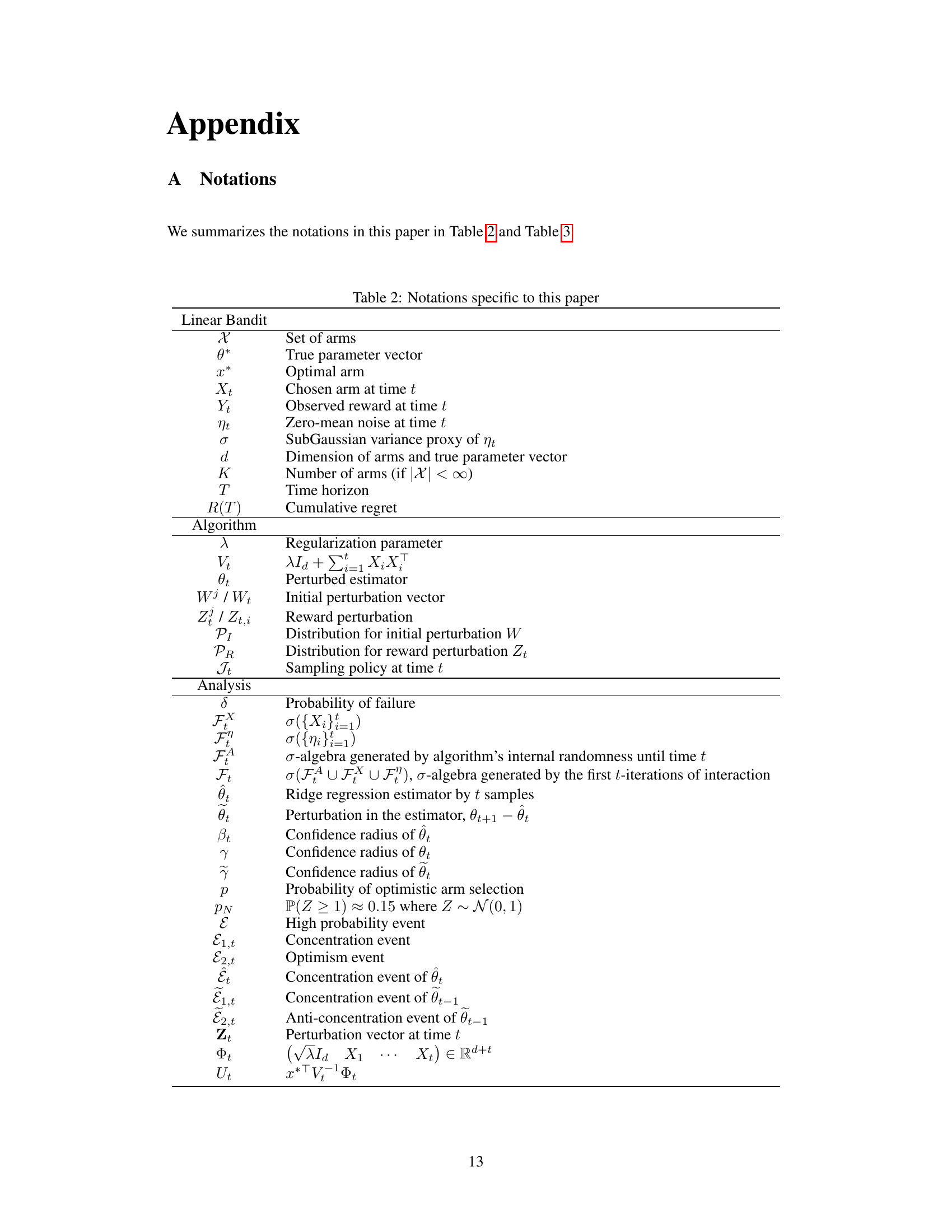

🔼 This table compares the frequentist and Bayesian regret bounds achieved by different linear ensemble sampling algorithms from the literature. It highlights the ensemble size required by each algorithm and shows how the regret bound of this work improves upon previous results by achieving a state-of-the-art regret bound of Õ(d³/²√T) with a sublinear ensemble size.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regret bounds for linear ensemble sampling

🔼 This table compares the frequentist and Bayesian regret bounds achieved by different linear ensemble sampling algorithms. It highlights the ensemble size required by each algorithm and shows how the regret bound of this paper improves upon previous results by reducing the dependence on the dimension (d) and the time horizon (T) while using a smaller ensemble size.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regret bounds for linear ensemble sampling

Full paper#