TL;DR#

Many real-world scenarios, such as robotics and resource management, involve multiple teams competing for optimal outcomes, leading to the concept of Team-Nash Equilibrium (TNE). However, it’s unclear if self-interested agents can reach a TNE without explicit coordination. This paper explores this by focusing on Zero-Sum Potential Team Games (ZSPTGs). These games allow for the study of interactions between multiple teams where the overall payoffs are balanced. This setup presents a fundamental challenge: can individual teams, each acting in their best interest, converge to a jointly optimal strategy?

The researchers propose a novel algorithm called Team-Fictitious Play (Team-FP), a variant of fictitious play tailored to multi-team games. Team-FP incorporates crucial features like inertia in action updates and responsiveness to the actions of all team members. The paper proves that Team-FP leads to near-TNE in ZSPTGs with quantifiable error bounds. They extend Team-FP to multi-team Markov games, both with and without explicit models of the game, providing extensive simulations to show the algorithm’s effectiveness and compare it with other learning dynamics. This research significantly strengthens our understanding of team coordination and provides a valuable tool for predicting and achieving coordinated team behavior in complex, multi-agent settings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in multi-agent systems, game theory, and machine learning because it introduces a novel approach for achieving team coordination in complex scenarios. The Team-Fictitious Play algorithm offers a practical solution for decentralized teams, bridging the gap between theoretical game-theoretic concepts and practical applications. The results demonstrate its effectiveness and open up new avenues for research on team learning in dynamic environments, including Markov games.

Visual Insights#

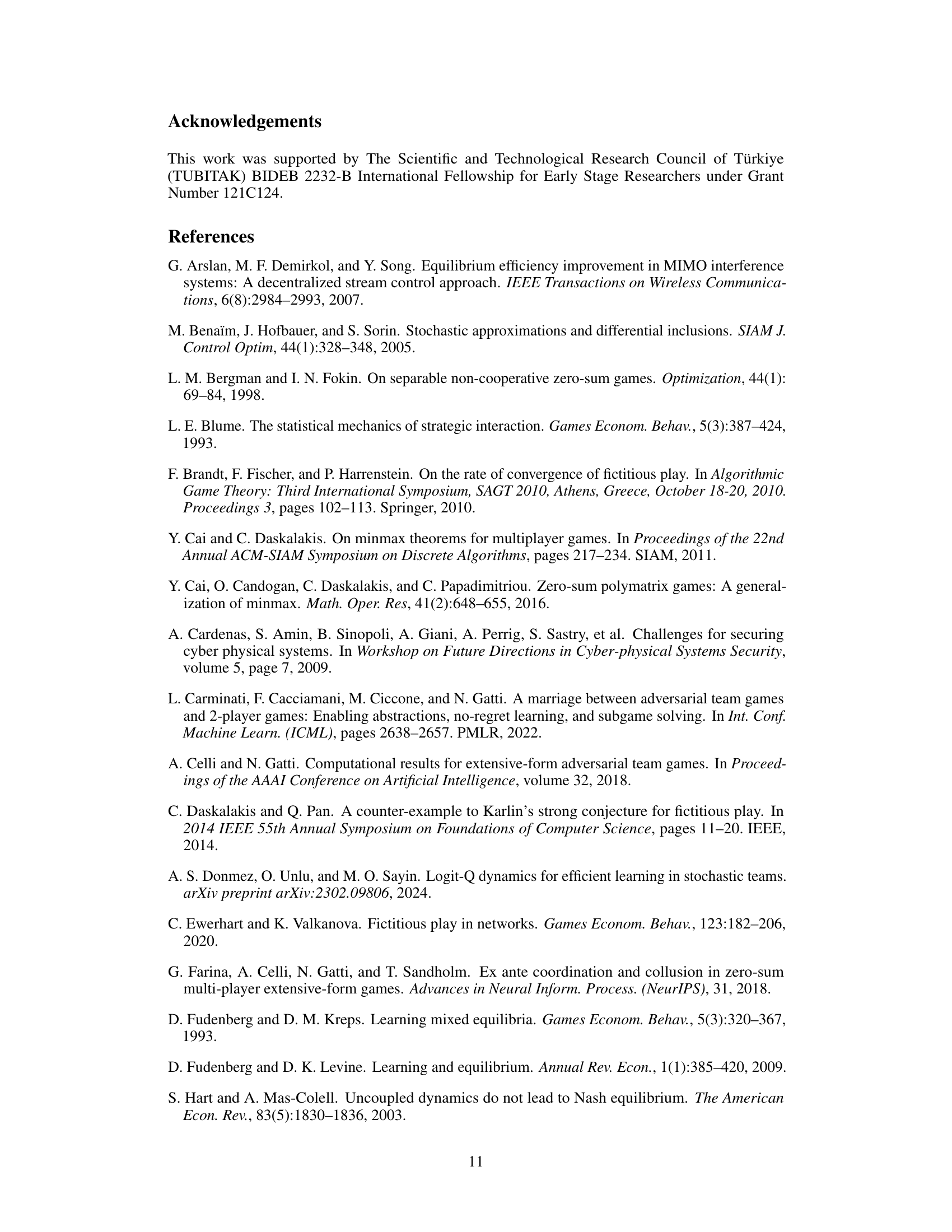

🔼 This figure illustrates the Team-Fictitious Play (Team-FP) dynamics for two-team games. The left side shows how team actions change over time based on beliefs about the other team’s actions, represented by a transition kernel and dashed lines indicating time shifts. The right side explains the core proof concept for Theorem 4.2, approximating the complex dynamics with a simpler reference scenario of stationary beliefs leading to a homogeneous Markov chain where the stationary distribution represents the best team response.

read the caption

Figure 2: An illustration of Team-FP dynamics for two-team games on the left-hand side. Team actions change according to a transition kernel depending on the beliefs formed about the other teams. Dashed lines represent the time shift. On the right-hand side, we depict the key proof idea that we approximate the evolution of the team actions with a reference scenario where beliefs are stationary such that team actions form a homogeneous Markov chain whose unique stationary distribution corresponds to the best team response.

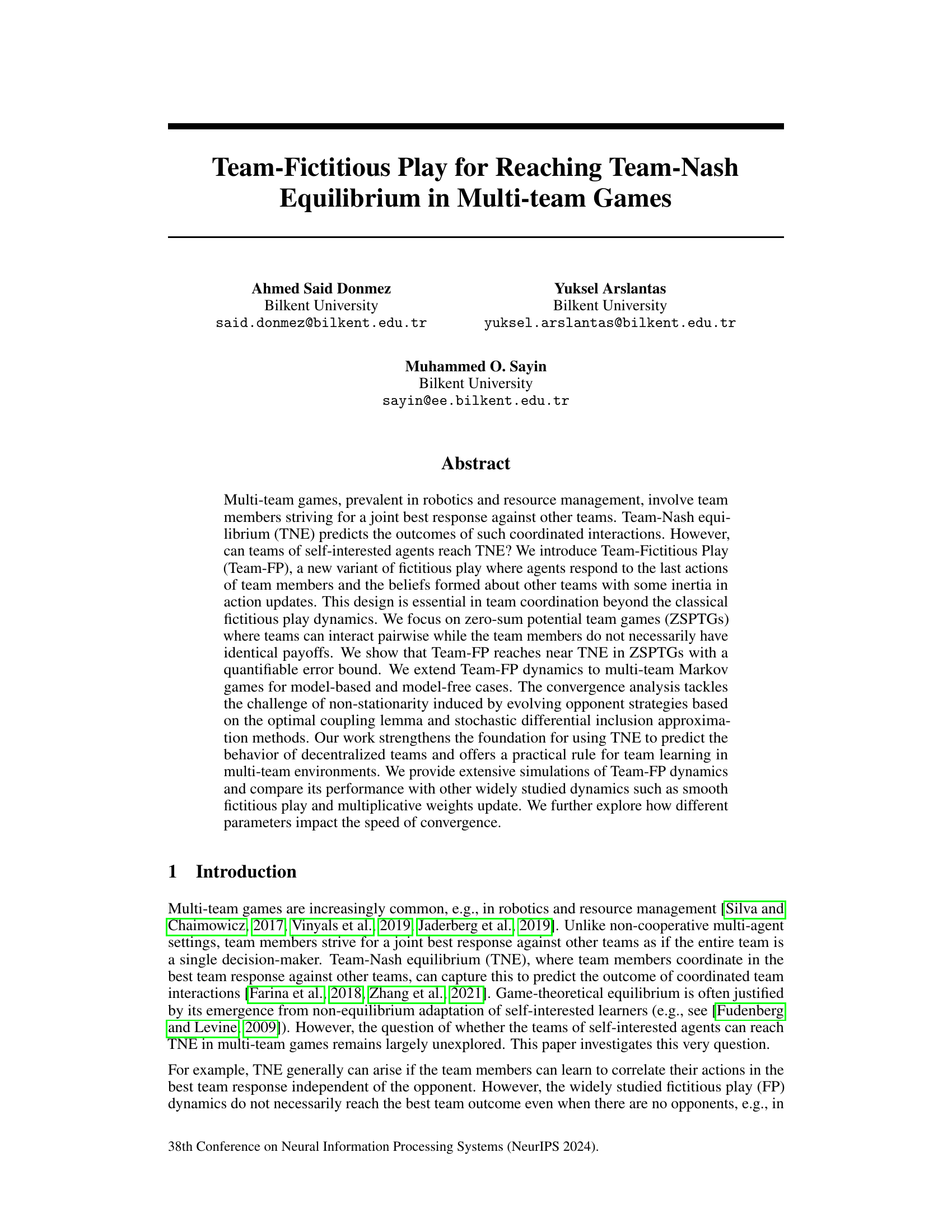

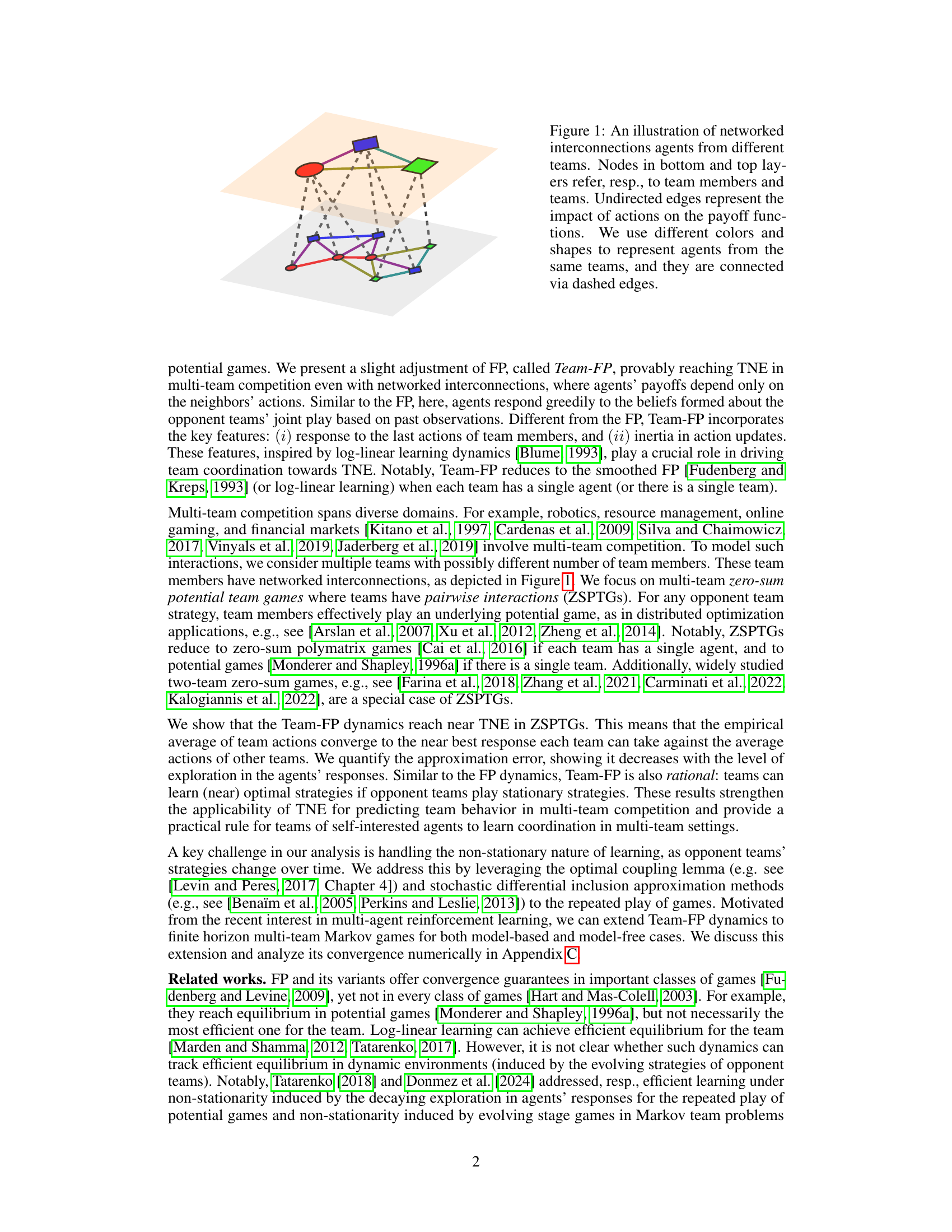

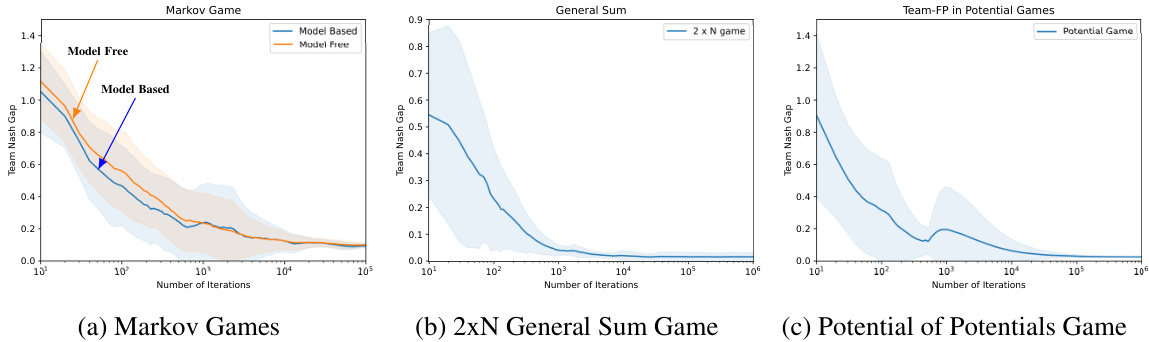

🔼 This figure shows three subfigures that illustrate the performance of the Team-Fictitious Play (Team-FP) algorithm and its comparison to other algorithms. Subfigure (a) demonstrates the impact of different levels of explicit team coordination on Team-FP’s convergence, (b) compares Team-FP and independent Team-FP with the Multiplicative Weights Update (MWU) and Smoothed Fictitious Play (SFP) algorithms, and (c) displays Team-FP’s convergence behavior against both stationary and competitive opponents.

read the caption

Figure 3: All the above figures show the variation of TNG over time. (a) Comparison of different levels of explicit coordination for Team-FP: independent agents (group size 1), pairs of cooperating agents (group size 2), and fully coordinated teams (group size 4). (b) Performance of Team-FP and Independent Team-FP compared to MWU and SFP algorithms in a 2-team ZSPTG. (c) Convergence of Team-FP against stationary and competitive opponents in a 3-team ZSPTG.

In-depth insights#

Team-Fictitious Play#

The concept of “Team-Fictitious Play” presents a novel approach to achieving coordination in multi-team games. It cleverly adapts the classic fictitious play algorithm, where agents iteratively best respond to the perceived strategies of their opponents, to a team-based setting. The key innovation lies in how teams of self-interested agents update their strategies: instead of individual agents reacting independently, the algorithm considers the team’s collective action. This is crucial in scenarios where team coordination is necessary for success. The introduction of inertia into action updates enhances the algorithm’s stability and efficiency, helping it overcome challenges posed by non-stationarity inherent in many dynamic game environments. The analysis of Team-Fictitious Play often focuses on zero-sum potential team games (ZSPTGs), where the simplicity of the game structure aids in proving convergence results. However, the algorithm’s applicability extends beyond ZSPTGs, with simulations demonstrating effectiveness in more complex scenarios. Overall, the approach provides a valuable framework for studying team learning and coordination, particularly in settings where communication is limited or impossible.

Convergence Analysis#

The convergence analysis section of a research paper is crucial for establishing the reliability and practical applicability of proposed methods. A rigorous analysis should address the non-stationarity of learning processes, especially in multi-agent settings where opponent strategies evolve dynamically. Approximation methods, such as those based on stochastic differential inclusions or optimal coupling lemmas, are often employed to handle the complexities of non-stationary dynamics. The analysis should clearly define convergence criteria and establish bounds on the approximation error, quantifying the gap between theoretical predictions and empirical observations. It’s essential to carefully consider the assumptions underlying the convergence analysis and discuss their implications for the applicability of the results. Furthermore, a strong convergence analysis should provide insights into the speed of convergence and how it is affected by key parameters, offering a deeper understanding of the algorithm’s behavior. Rationality of the method should also be addressed, demonstrating that the algorithm converges to a desirable equilibrium even against stationary opponents.

Multi-Team Markov#

In the context of multi-agent systems, Multi-Team Markov Games represent a powerful framework to model interactions where agents are grouped into teams with shared objectives. These games extend standard Markov Games by introducing the team structure, allowing for more complex strategic reasoning and cooperation within teams, and competition between them. Analyzing such games requires considering the challenges of decentralized decision-making, information asymmetry between teams, and the non-stationarity of strategies resulting from continuous learning and adaptation. Key aspects in this area include developing effective learning algorithms for teams to reach a team-Nash equilibrium (TNE), characterizing the convergence properties of these algorithms in complex scenarios, and understanding the impact of different team coordination mechanisms on outcomes. Model-based and model-free approaches have been proposed for learning in multi-team Markov games, with each offering different trade-offs in terms of sample complexity, computational cost, and ability to handle uncertainty.

Limitations and Impacts#

The section ‘Limitations and Impacts’ of a research paper should thoroughly address both the shortcomings of the study and its potential consequences. Limitations might include the scope of the experiments (e.g., specific game types, limited parameter exploration), the reliance on specific assumptions (e.g., rationality of agents, stationary strategies), or the theoretical nature of certain results without extensive empirical validation. It is crucial to discuss how these limitations could affect the generalizability or robustness of the findings and suggest avenues for future work to overcome them. Impacts, on the other hand, should assess both the positive and negative societal consequences of the research. Positive impacts could focus on the potential improvements in multi-agent system design or resource allocation, while acknowledging any possible misuse or unintended effects. A balanced discussion of limitations and impacts is essential for responsible research practice, ensuring that the study is appropriately contextualized within its broader implications.

Future Research#

The paper’s “Future Research” section could fruitfully explore extending Team-FP dynamics beyond zero-sum potential team games (ZSPTGs) and investigating its convergence properties in more general settings. A key focus could be on analyzing the impact of different learning dynamics within teams, such as exploring whether other than log-linear learning mechanisms would still lead to efficient team coordination. Another promising avenue would be investigating the robustness of Team-FP to imperfect information and communication delays, as these are prevalent in real-world multi-team scenarios. Furthermore, a comprehensive comparative analysis against other widely-used learning algorithms (beyond those mentioned) in diverse multi-team games, combined with a theoretical analysis of their convergence rates, would be valuable. Specifically, examining the trade-off between convergence speed and equilibrium efficiency would provide a deeper understanding of Team-FP’s strengths and weaknesses. Finally, applying Team-FP to practical real-world multi-team problems and providing case studies illustrating its effectiveness could significantly enhance its impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the Team-FP dynamics for a two-team game. The left side shows how each team updates its beliefs about the other team’s actions based on observations and uses a transition kernel to determine its next actions. The right side presents the core idea behind the convergence proof: approximating the actual dynamics with a reference scenario where beliefs are constant, making the team actions a homogeneous Markov chain with a stationary distribution that aligns with the best team response.

read the caption

Figure 2: An illustration of Team-FP dynamics for two-team games on the left-hand side. Team actions change according to a transition kernel depending on the beliefs formed about the other teams. Dashed lines represent the time shift. On the right-hand side, we depict the key proof idea that we approximate the evolution of the team actions with a reference scenario where beliefs are stationary such that team actions form a homogeneous Markov chain whose unique stationary distribution corresponds to the best team response.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the performance of the Team-Fictitious Play (Team-FP) algorithm in various settings and compares it against other algorithms. Specifically, (a) shows how the Team-FP’s performance changes with different levels of coordination among team members (independent agents, pairs of cooperating agents, and fully coordinated teams), (b) compares Team-FP against other algorithms like MWU and SFP, and (c) compares the convergence speed of Team-FP against stationary and competitive opponents.

read the caption

Figure 3: All the above figures show the variation of TNG over time. (a) Comparison of different levels of explicit coordination for Team-FP: independent agents (group size 1), pairs of cooperating agents (group size 2), and fully coordinated teams (group size 4). (b) Performance of Team-FP and Independent Team-FP compared to MWU and SFP algorithms in a 2-team ZSPTG. (c) Convergence of Team-FP against stationary and competitive opponents in a 3-team ZSPTG.

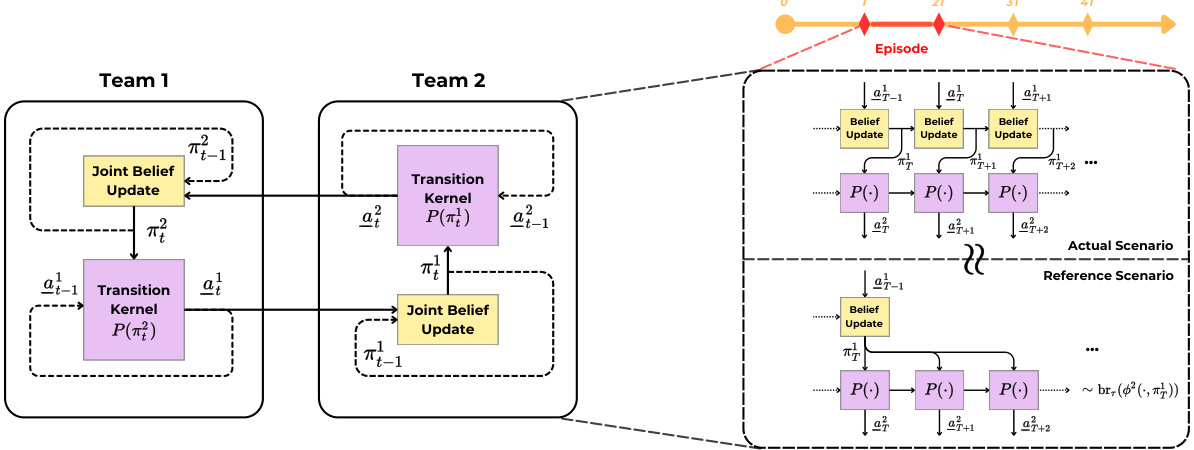

🔼 Figure 4(a) shows a schematic of an airport security game. A security chief (defender) must decide which of the six gates to defend, incurring a cost. Three intruders (attackers) independently decide whether to attack a gate or remain idle. Intruders gain rewards based on whether they attack defended or undefended gates. Figure 4(b) presents simulation results demonstrating that Team-Fictitious Play (Team-FP) dynamics reach near team-minimax equilibrium in this security game.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) The illustration of an airport security game: a security chief guarding the six gates of an airport against three different intruders making decisions autonomously. (b) The evolution of Team Nash Gap in airport security game, showing that Team-FP dynamics reach near team-minimax equilibrium.

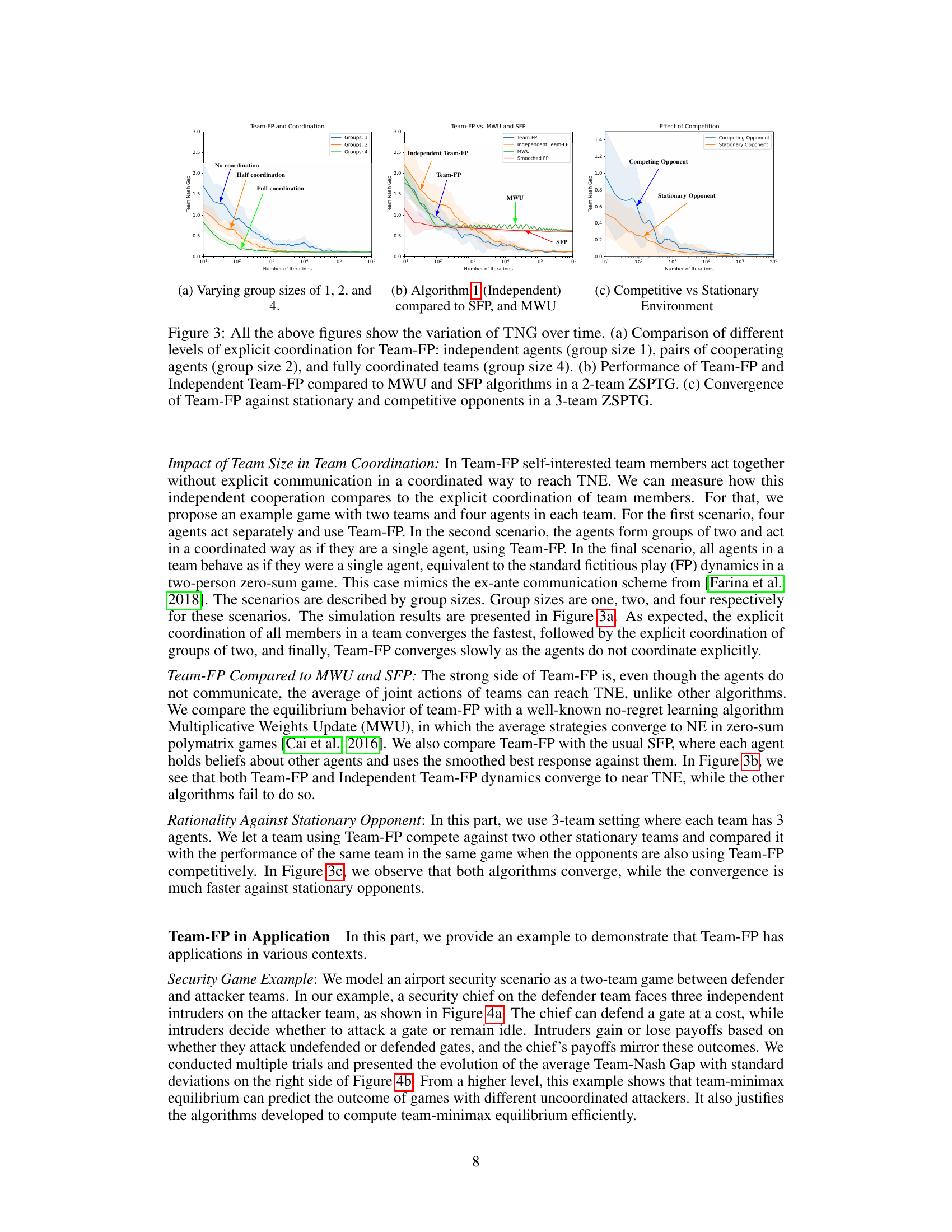

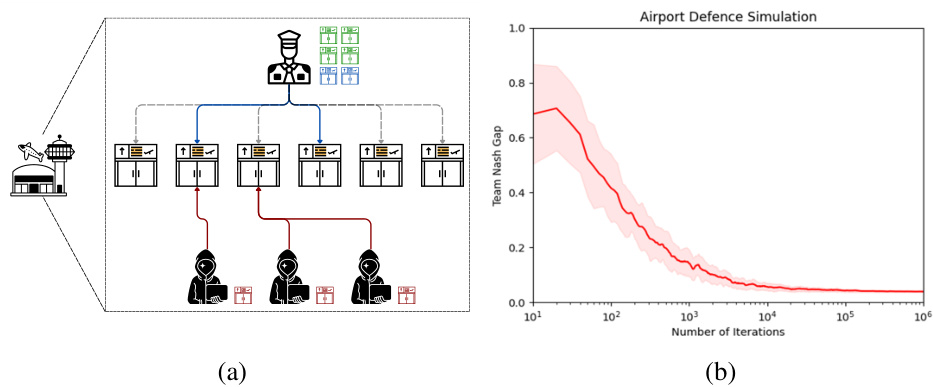

🔼 This figure shows simulation results for a 3-team game with 3 agents per team. Subfigure (a) presents the network structure used. Subfigure (b) illustrates how the Team Nash Gap (TNG) changes over iterations for different values of the temperature parameter τ (0.1, 0.15, and 0.2) in the Team-FP algorithm, demonstrating the impact of this parameter on the convergence speed and closeness to Team Nash Equilibrium (TNE). Subfigure (c) compares the Independent Team-FP algorithm’s performance for varying values of parameter δ (0.2 and 0.5), again showing the TNG over iterations, with τ fixed at 0.1. This highlights the effect of the exploration parameter δ on convergence speed.

read the caption

Figure 5: The 3-team experiments are tested on the randomly generated network structure (a). The other figures (b), and (c), shows the variation of TNG over iterations. (a) The simulation network for a multi-team ZSPTG, in which there are 3-teams with 3 agents in each team. (b) The impact of varying temperature parameter τ (0.1, 0.15, 0.2) in Algorithm 1 on the closeness to TNE. (c) The effect of different δ values (0.2, 0.5) in (Independent) Algorithm 1 on the convergence speed with τ fixed at 0.1

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Team-FP under different coordination levels in a multi-team game and compares its convergence speed against two other algorithms (MWU, SFP). The subfigures show how explicit coordination within a team improves the convergence speed to TNE and how Team-FP performs against both stationary and competitive opponents.

read the caption

Figure 3: All the above figures show the variation of TNG over time. (a) Comparison of different levels of explicit coordination for Team-FP: independent agents (group size 1), pairs of cooperating agents (group size 2), and fully coordinated teams (group size 4). (b) Performance of Team-FP and Independent Team-FP compared to MWU and SFP algorithms in a 2-team ZSPTG. (c) Convergence of Team-FP against stationary and competitive opponents in a 3-team ZSPTG.

🔼 This figure shows the results of a large-scale experiment on the scalability of Team-FP in a networked game. The game involved three teams, each with nine agents, resulting in a large joint action space. The figure demonstrates that, despite the problem’s scale and the agents’ only considering actions of their 2-hop neighbors, Team-FP dynamics converge to the Team-Nash equilibrium at a similar rate as in smaller-scale experiments. The top-right inset displays the network structure connecting the agents, visually representing the sparse network interconnections.

read the caption

Figure 7: The evolution of Team Nash Gap in the large-scale example provided in the top right, showing that Team-FP dynamics reach near team-minimax equilibrium.

Full paper#