TL;DR#

Existing HDR view synthesis methods, while excelling in image quality, suffer from long training times and inability to perform real-time rendering. The advent of 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) offers a potential solution, but directly applying it to RAW images presents challenges due to noise, limited color representation, and inaccurate scene structure. These limitations hinder downstream tasks like refocusing and tone mapping.

The proposed LE3D method addresses these issues by using Cone Scatter Initialization for improved SfM, replacing spherical harmonics with Color MLP for better RAW color representation, and employing depth distortion and near-far regularizations for enhanced scene structure. The experiments demonstrate that LE3D achieves real-time rendering speeds, up to 4000x faster than previous methods, with only 1% of the training time, while maintaining comparable image quality and enabling various downstream tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents LE3D, a novel method for HDR view synthesis that achieves real-time rendering and significantly reduces training time compared to existing approaches. This has significant implications for various applications, including AR/VR, computational photography, and cultural heritage preservation, opening up new avenues for research in real-time 3D scene reconstruction and HDR view synthesis.

Visual Insights#

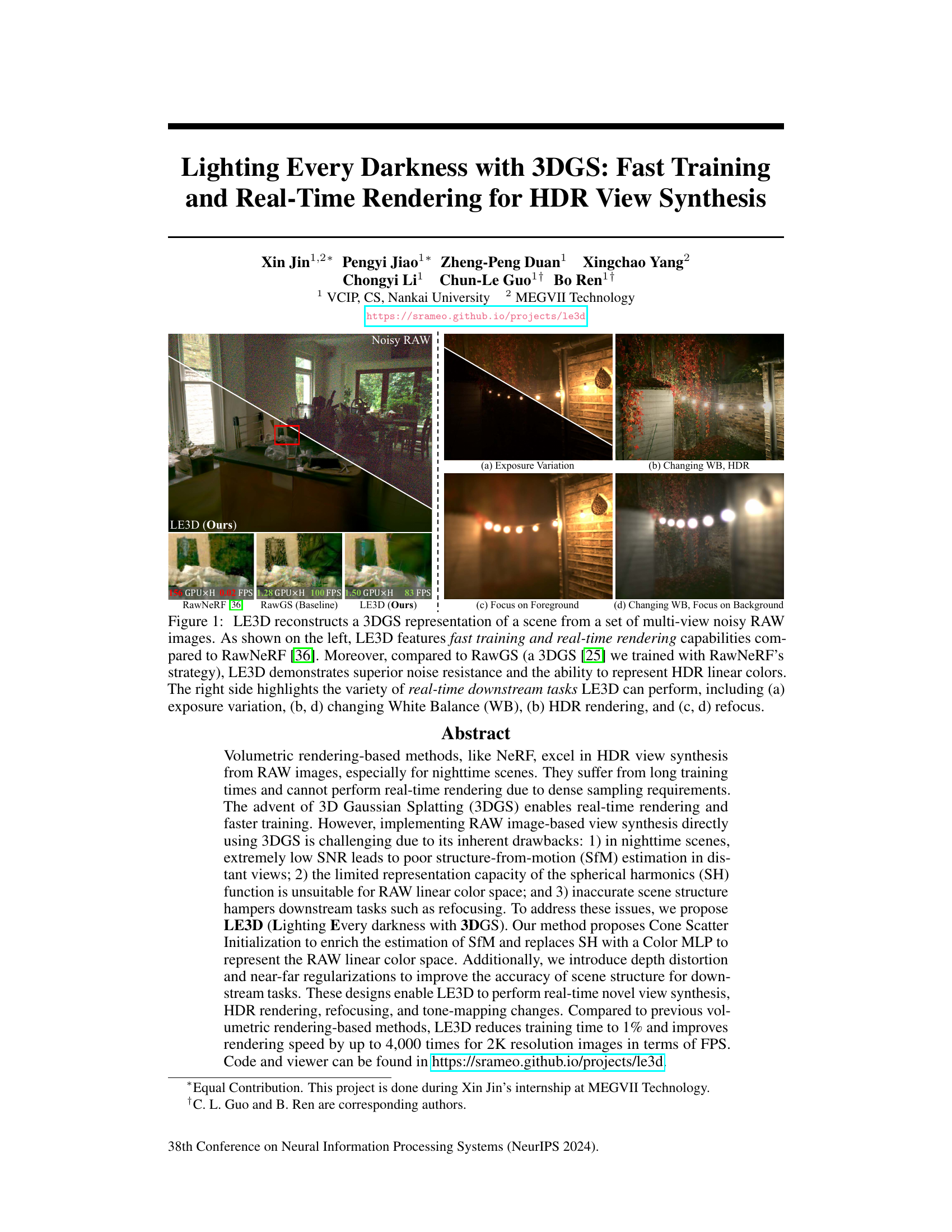

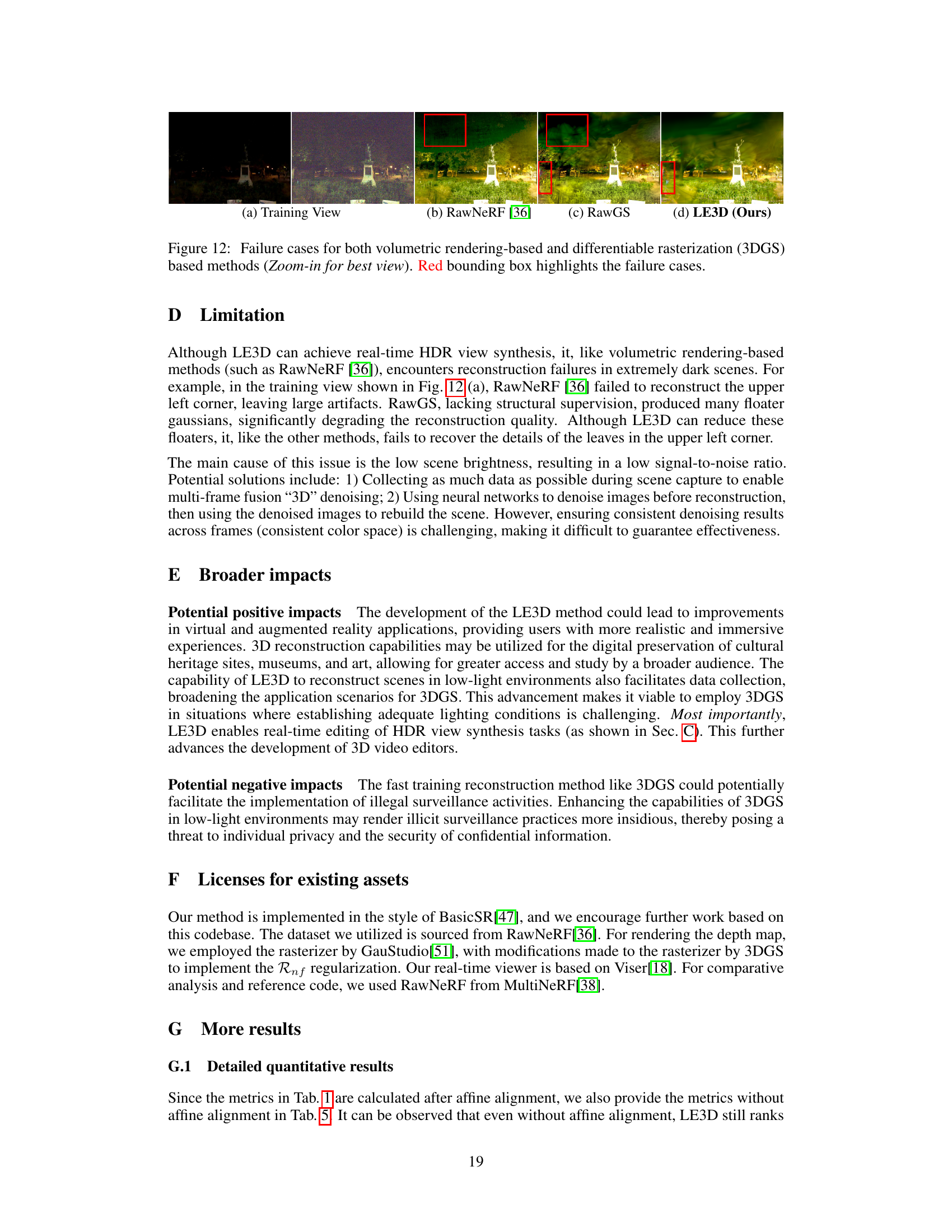

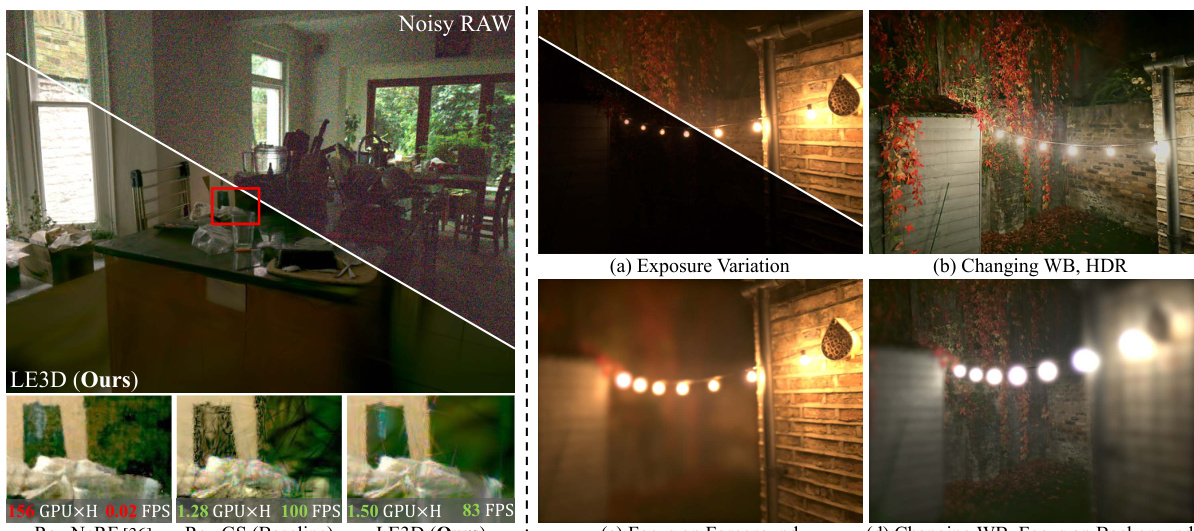

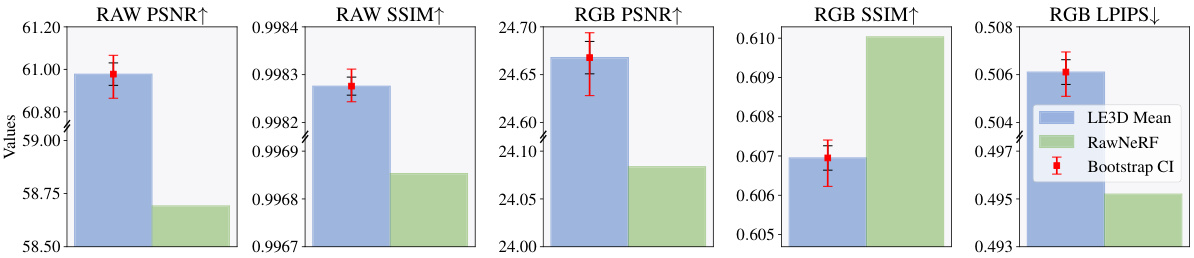

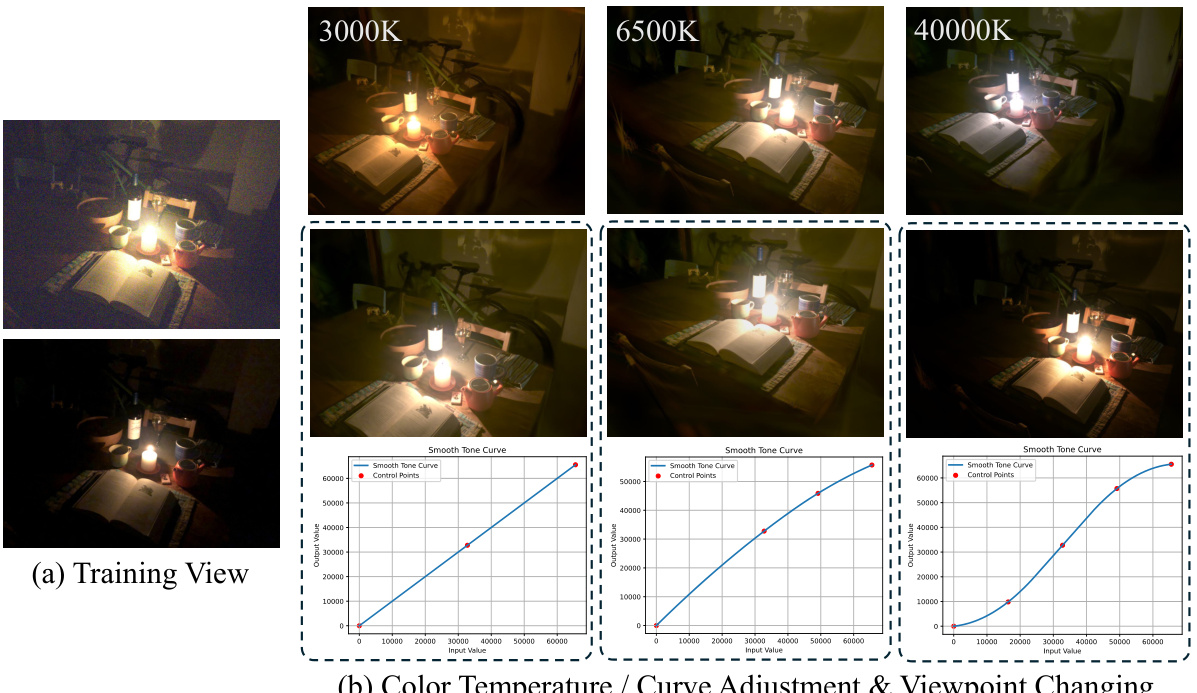

🔼 This figure showcases LE3D’s capabilities in reconstructing 3D scenes from noisy RAW images. The left side compares LE3D’s training time and rendering speed to RawNeRF, highlighting LE3D’s significant speed advantage. It also compares LE3D’s noise resistance and HDR color representation to a baseline method (RawGS). The right side demonstrates LE3D’s ability to perform real-time downstream tasks such as exposure variation, white balance adjustment, HDR rendering, and refocusing.

read the caption

Figure 1: LE3D reconstructs a 3DGS representation of a scene from a set of multi-view noisy RAW images. As shown on the left, LE3D features fast training and real-time rendering capabilities compared to RawNeRF [36]. Moreover, compared to RawGS (a 3DGS [25] we trained with RawNeRF's strategy), LE3D demonstrates superior noise resistance and the ability to represent HDR linear colors. The right side highlights the variety of real-time downstream tasks LE3D can perform, including (a) exposure variation, (b, d) changing White Balance (WB), (b) HDR rendering, and (c, d) refocus.

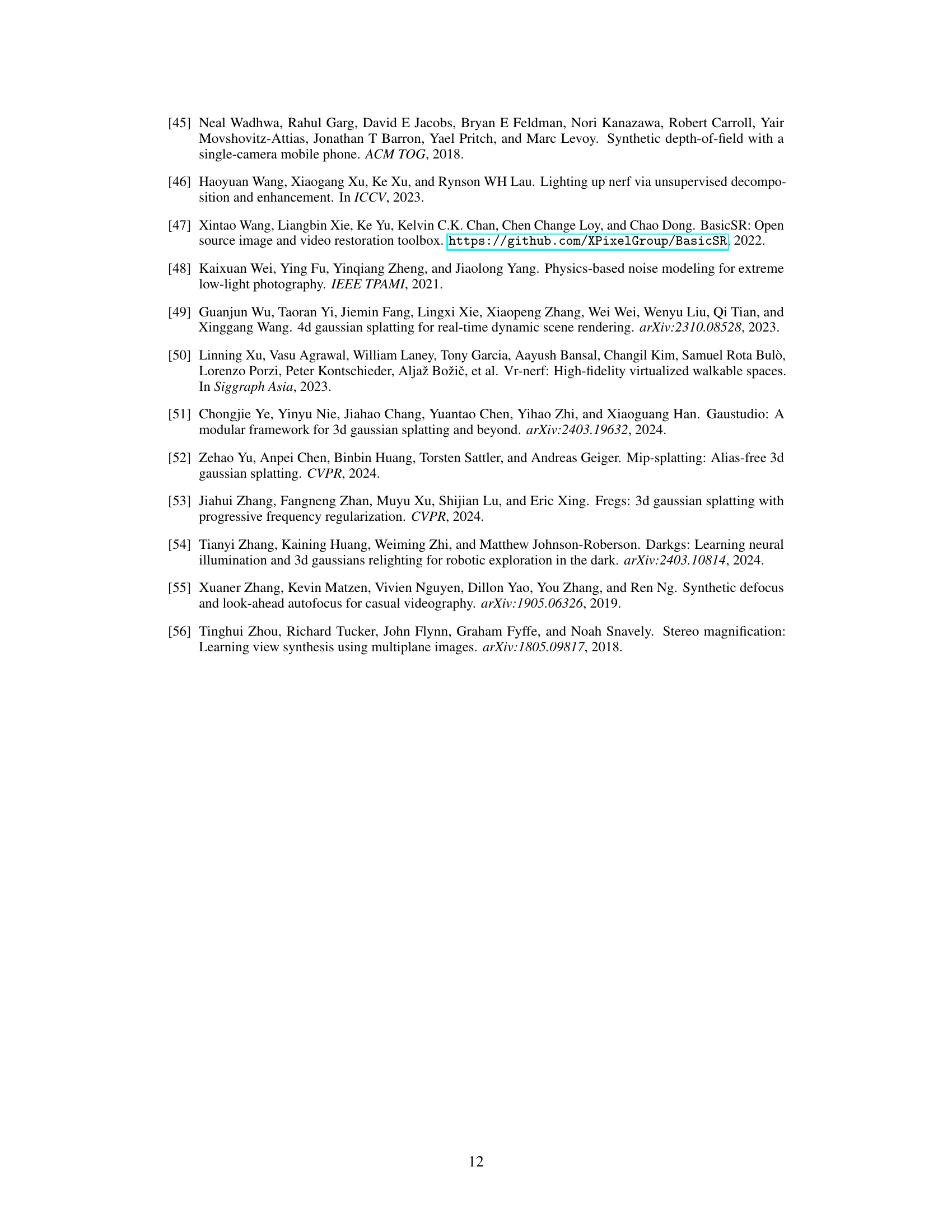

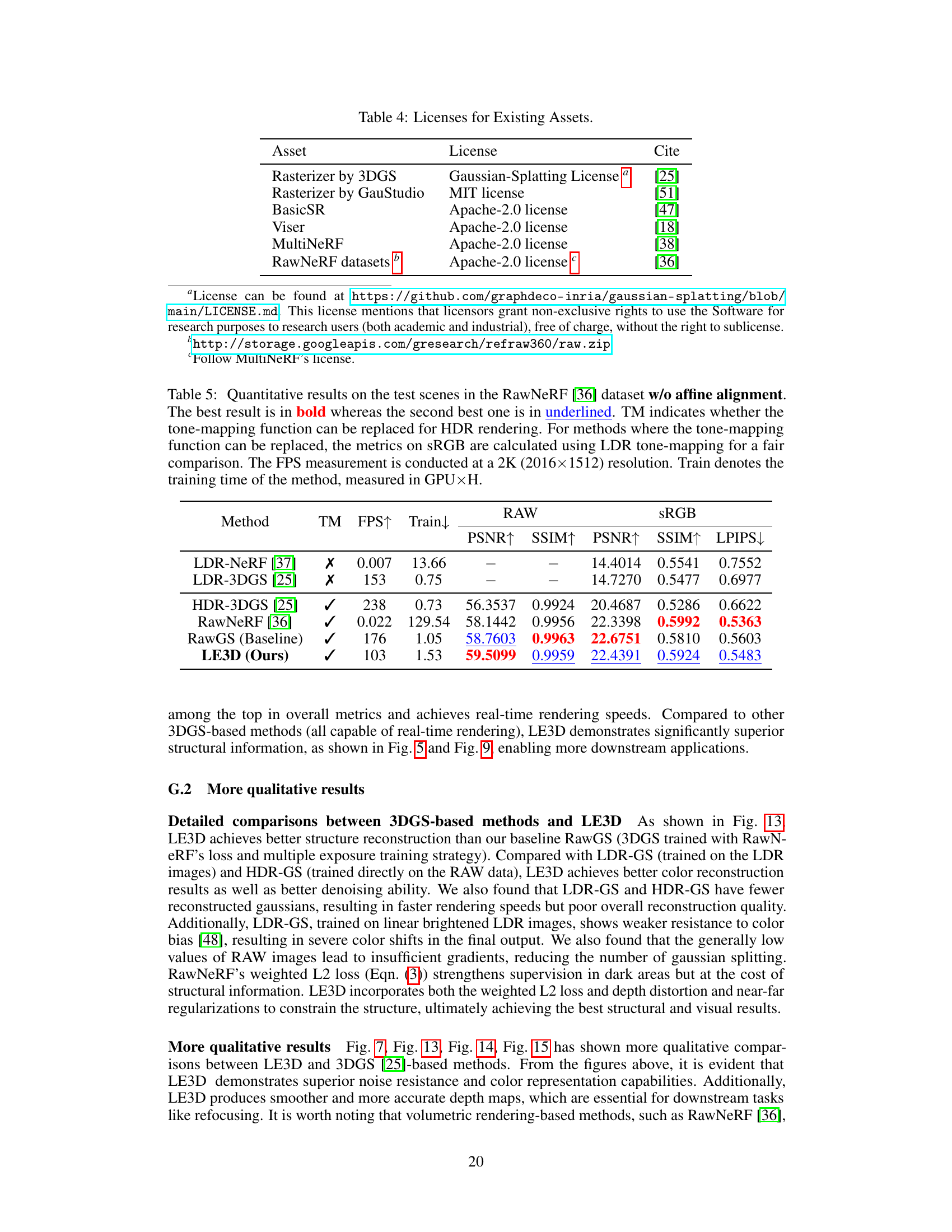

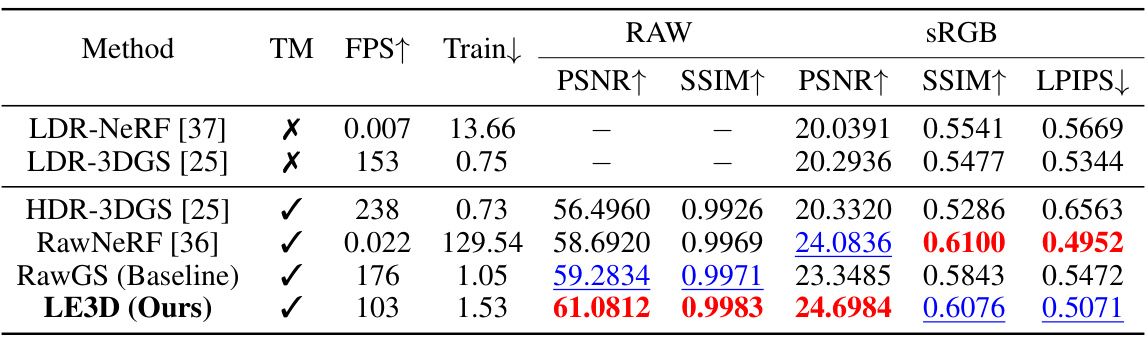

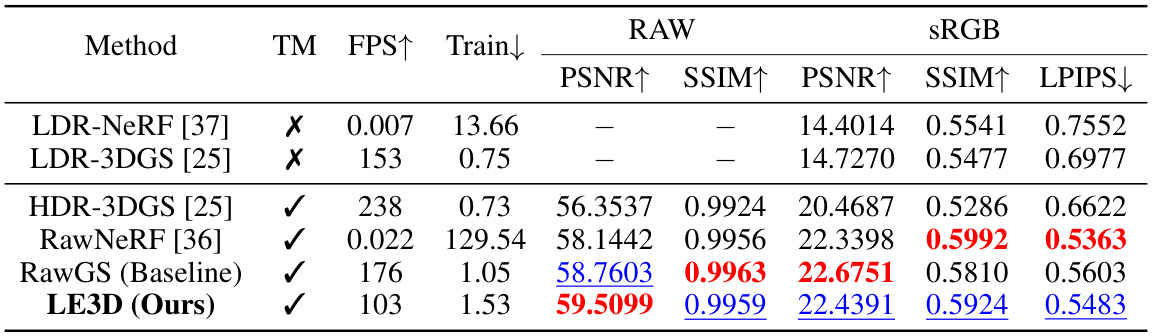

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of LE3D against other HDR view synthesis methods on the RawNeRF dataset. Metrics include PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS for both RAW and sRGB images. Training time (in GPU hours) and rendering speed (FPS) are also shown. The table highlights LE3D’s comparable performance to state-of-the-art methods but with significantly faster rendering speed and shorter training time.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the test scenes of the RawNeRF [36] dataset. The best result is in bold whereas the second best one is in underlined. TM indicates whether the tone-mapping function can be replaced for HDR rendering. For methods where the tone-mapping function can be replaced, the metrics on sRGB are calculated using LDR tone-mapping for a fair comparison. The FPS measurement is conducted at a 2K (2016×1512) resolution. Train denotes the training time of the method, measured in GPU×H. LE3D achieves comparable performance with previous volumetric rendering based methods (RawNeRF [36]), but with 4000× faster rendering speed.

In-depth insights#

3DGS for HDR#

Utilizing 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) for High Dynamic Range (HDR) image synthesis presents a compelling approach to real-time rendering and efficient training. 3DGS’s inherent speed advantages stem from its sparse scene representation using Gaussian primitives, unlike the dense sampling of traditional volumetric methods. However, directly applying 3DGS to HDR view synthesis from noisy RAW images faces challenges. Noise in low-light conditions hampers accurate structure-from-motion (SfM) estimation, and the limited expressiveness of spherical harmonics (SH) for representing RAW linear color space affects color accuracy. To address this, improvements like Cone Scatter Initialization to enrich SfM and employing Color MLPs to replace SH are crucial for successful HDR reconstruction. Furthermore, regularization techniques like depth distortion and near-far regularization are necessary to improve scene structure and enable downstream tasks such as refocusing. The combination of these improvements allows for a significant leap in rendering speed and training efficiency compared to existing NeRF-based approaches, while maintaining comparable visual quality. This ultimately makes real-time HDR view synthesis using 3DGS a practical reality, with strong implications for various applications such as AR/VR and computational photography.

Fast Training#

The concept of “Fast Training” in the context of a deep learning model for HDR view synthesis is crucial for practical applications. The paper likely highlights achieving significantly reduced training times compared to existing methods like NeRF. This is achieved through the adoption of 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS), a more efficient representation that accelerates the training process. The improvements are likely demonstrated quantitatively, showcasing a substantial reduction in training time (e.g., from days to hours, or even less). Efficient architectural designs within the 3DGS framework likely play a key role, enabling faster convergence and optimization. The paper will probably detail specific innovations, such as clever initialization strategies, optimized loss functions, or novel regularization techniques, that contribute to the speed improvements. The emphasis on “fast training” underscores the practical value of the proposed method, making real-time or near real-time HDR view synthesis feasible.

Real-time Rendering#

Real-time rendering in the context of HDR view synthesis presents a significant challenge, demanding efficient algorithms to process high-dimensional data and produce visually appealing results within strict timing constraints. The need for real-time performance is crucial for interactive applications, such as virtual and augmented reality systems. This necessitates optimizing various stages of the rendering pipeline, from scene representation and structure estimation to color space handling and ray tracing. 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) emerges as a promising approach due to its inherent speed and efficiency. However, challenges remain in applying 3DGS to raw HDR data, including noise management, efficient color representation (e.g., using MLPs instead of SH), and robust structure estimation, which the paper addresses. The success of real-time rendering hinges on the intricate interplay of these factors, impacting the overall visual quality, fidelity, and responsiveness of the system.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically evaluate the contribution of individual components within a complex model. By progressively removing or altering specific parts, researchers can isolate the impact of each element on the overall performance. This process is crucial for understanding the model’s inner workings, identifying critical components, and improving its design. In the context of a research paper, a well-executed ablation study provides strong evidence supporting the claims made about the model’s effectiveness and its individual components. It helps determine which parts are essential and which can be potentially simplified or removed to increase efficiency without sacrificing performance. A robust ablation study often involves multiple variations of the model, providing a detailed analysis of how each component affects different performance metrics. Conversely, a poorly designed ablation study can weaken the overall argument of the paper, failing to deliver convincing support for the claims and even raising doubts about the model’s overall effectiveness.

Limitations#

The limitations section of a research paper is crucial for evaluating the scope and applicability of the presented work. A thoughtful limitations section acknowledges the shortcomings and boundaries of the research, demonstrating intellectual honesty and enhancing the paper’s overall credibility. Addressing limitations directly shows the researchers’ understanding of the research’s context and its potential weaknesses. This might include discussing the generalizability of the findings to different datasets or populations, as well as mentioning any methodological constraints or assumptions made during the study. For example, simplifying assumptions in a model to enhance computational feasibility are often cited as a limitation; the performance of the method might be dependent on specific data characteristics; or the availability of certain resources may affect replicability. A well-written limitations section should not simply list problems but provide insightful analysis on their potential impact, suggesting avenues for future research. Failing to discuss limitations can undermine a paper’s scientific rigor and its overall impact.

More visual insights#

More on figures

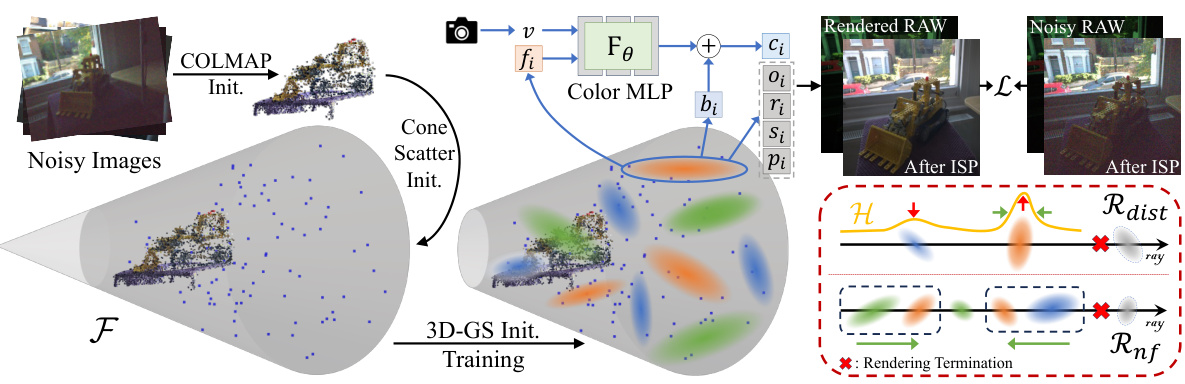

🔼 This figure illustrates the pipeline of LE3D, highlighting key stages: 1) Initial point cloud and camera pose estimation using COLMAP; 2) Enhancement of distant points via Cone Scatter Initialization; 3) 3DGS training with a Color MLP replacing spherical harmonics; 4) Loss function incorporating RawNeRF’s weighted L2 loss and novel regularizations (Rdist and Rnf) for scene structure refinement. The figure also shows the representation of individual gaussians and the rendering process.

read the caption

Figure 2: Pipeline of our proposed LE3D. 1) Using COLMAP to obtain the initial point cloud and camera poses. 2) Employing Cone Scatter Initialization to enrich the point clouds of distant scenes. 3) The standard 3DGS training, where we replace the original SH with our tiny Color MLP to represent the RAW linear color space. 4) We use RawNeRF's weighted L2 loss L (Eqn. (3)) as image-level supervision, and our proposed Rdist (Eqn. (8)) as well as Rnf (Eqn. (9)) as scene structure regularizations. In this context, fi, bi, and ci respectively represent the color feature, bias, and final rendered color of each gaussian i. Similarly, oi, ri, si, and pi denote the opacity, rotation, scale, and position of them.

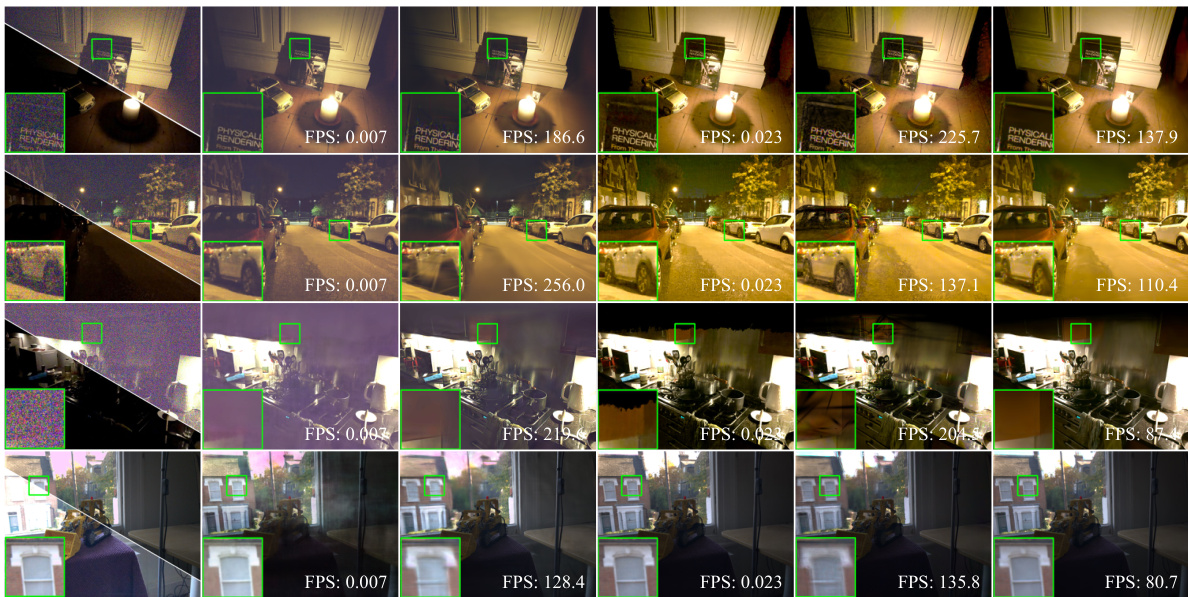

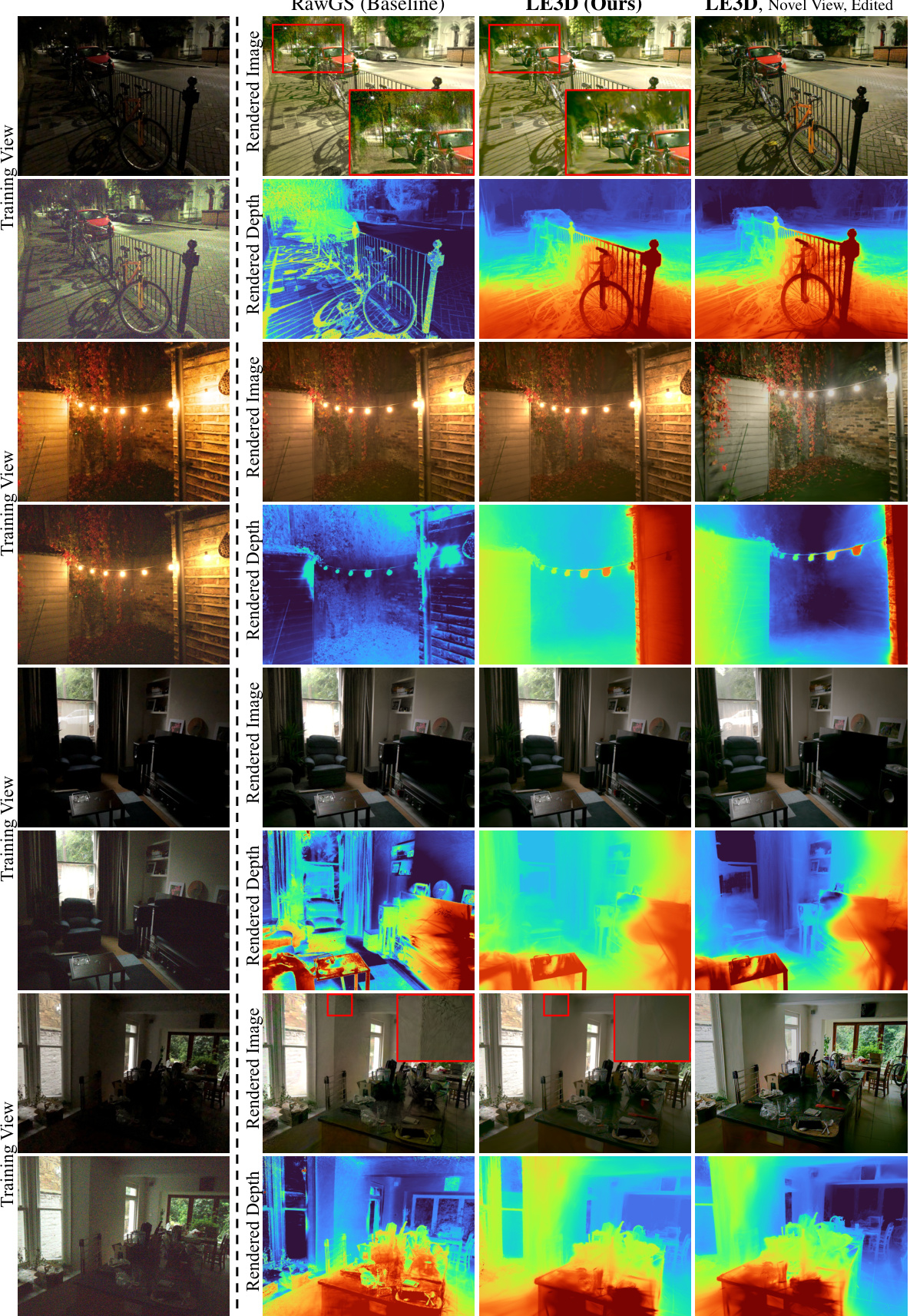

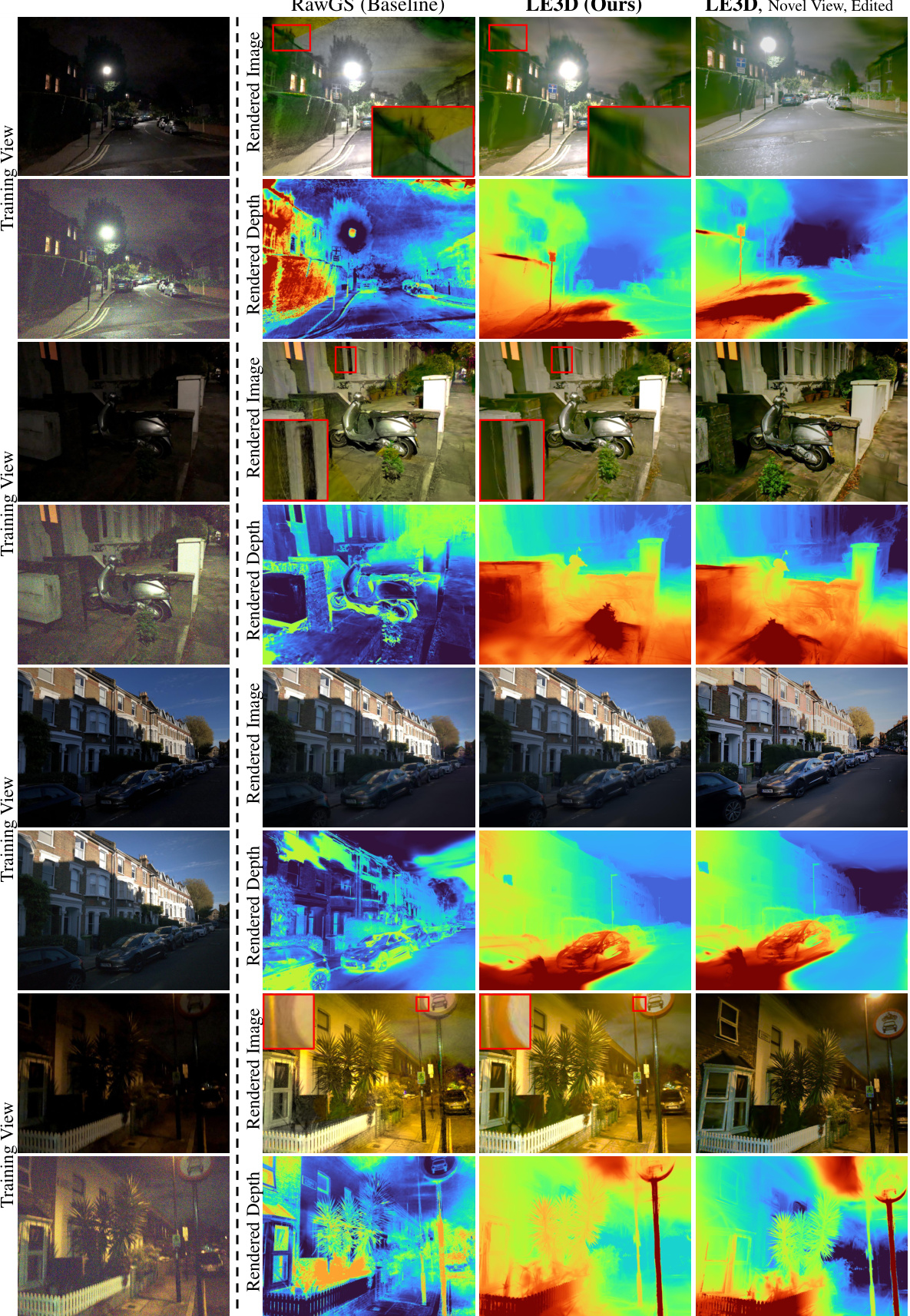

🔼 This figure compares the performance of LE3D against other reconstruction methods (LDR-NeRF, LDR-3DGS, RawNeRF, RawGS). It shows example images from four different scenes, highlighting LE3D’s superior ability to recover details, particularly in distant parts of the scene, and its noise resilience when compared to 3DGS-based methods. The comparison also demonstrates a massive speed improvement (3000-6000x) over NeRF-based methods.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visual comparison between LE3D and other reconstruction methods (Zoom-in for best view). The training view contains two parts: the post-processed RAW image with linear brightness enhancement (up) and the image directly output by the device (down). By comparison to the 3DGS-based method, LE3D recovers sharper details in the distant scene and is more resistant to noise. Additionally, compared to NeRF-based methods, LE3D achieves comparable results with 3000×-6000× improvement in rendering speed.

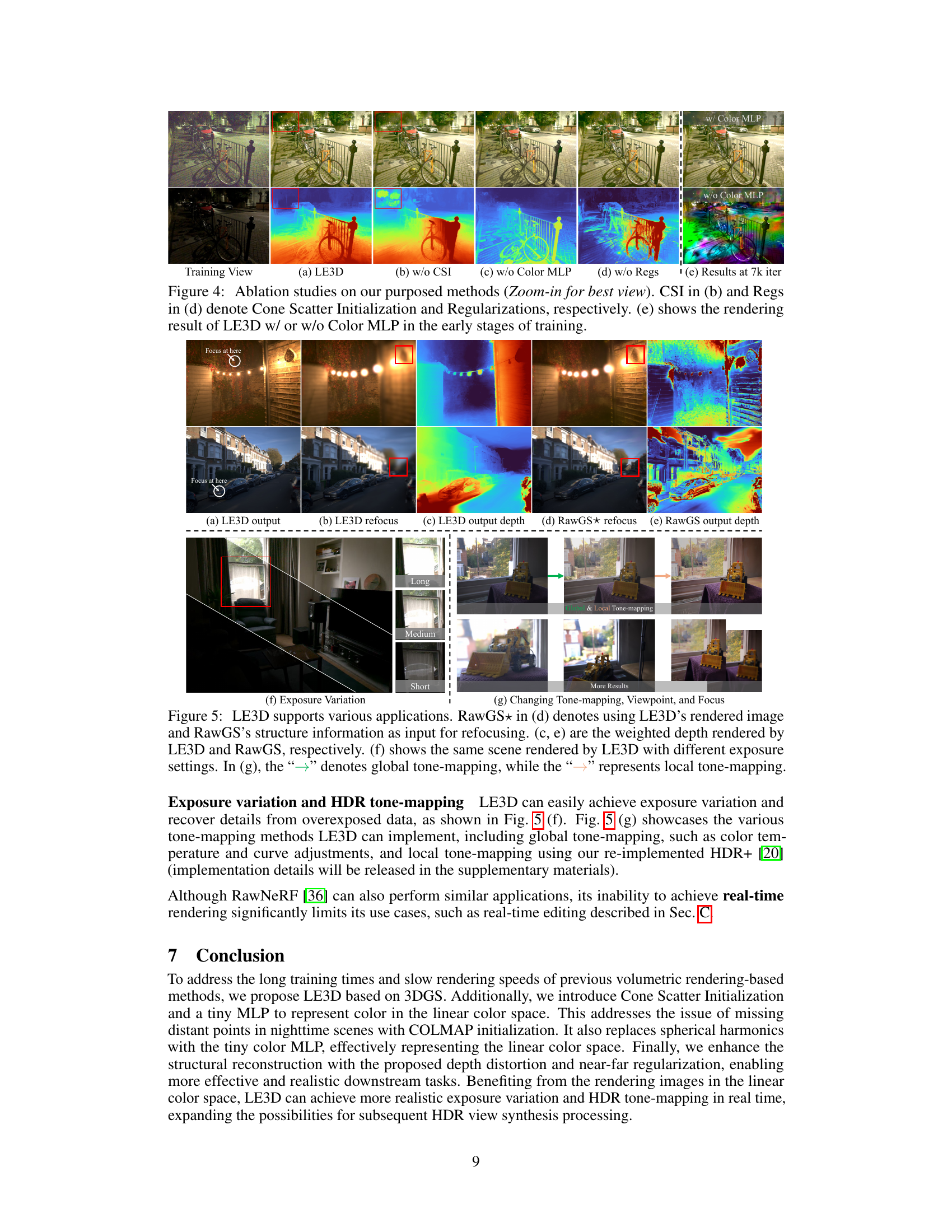

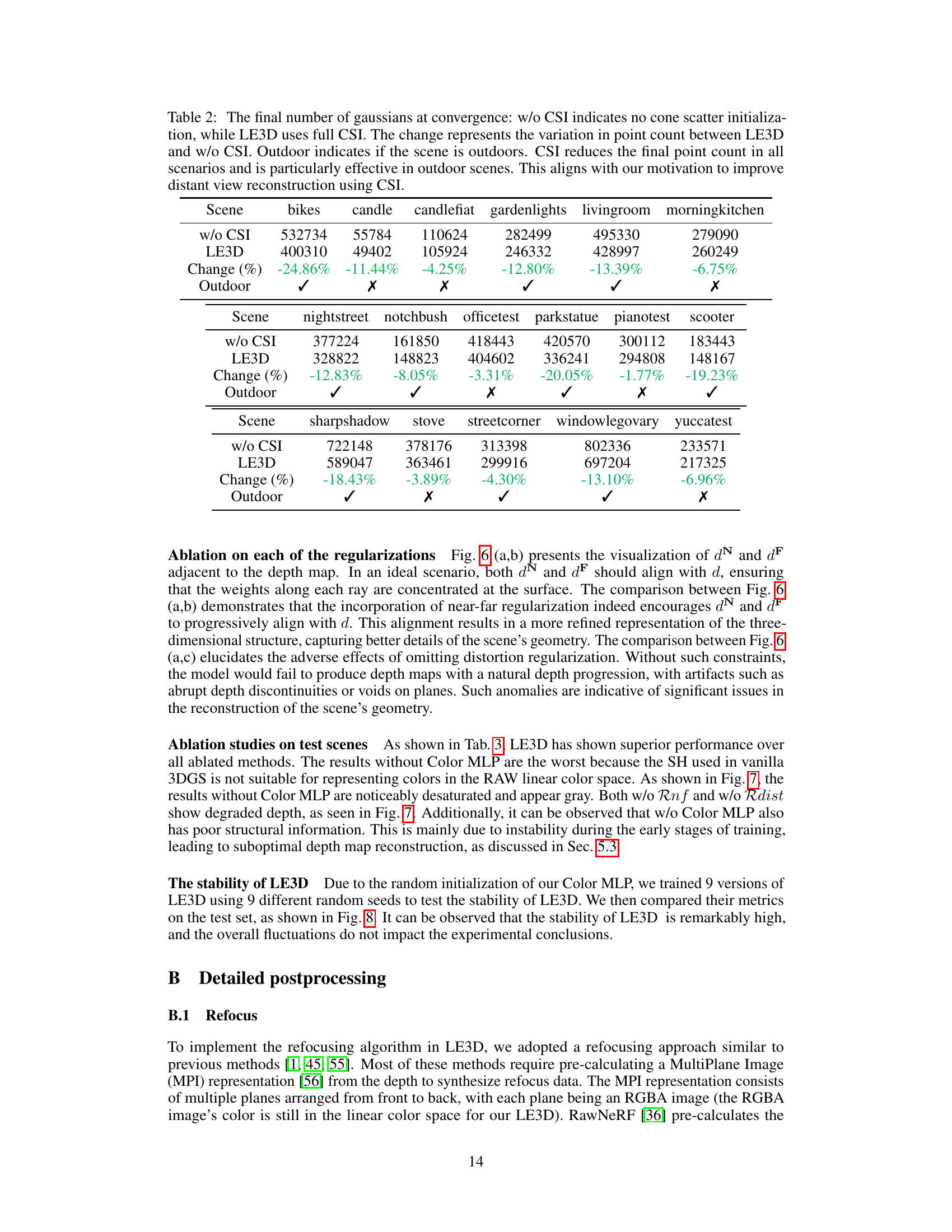

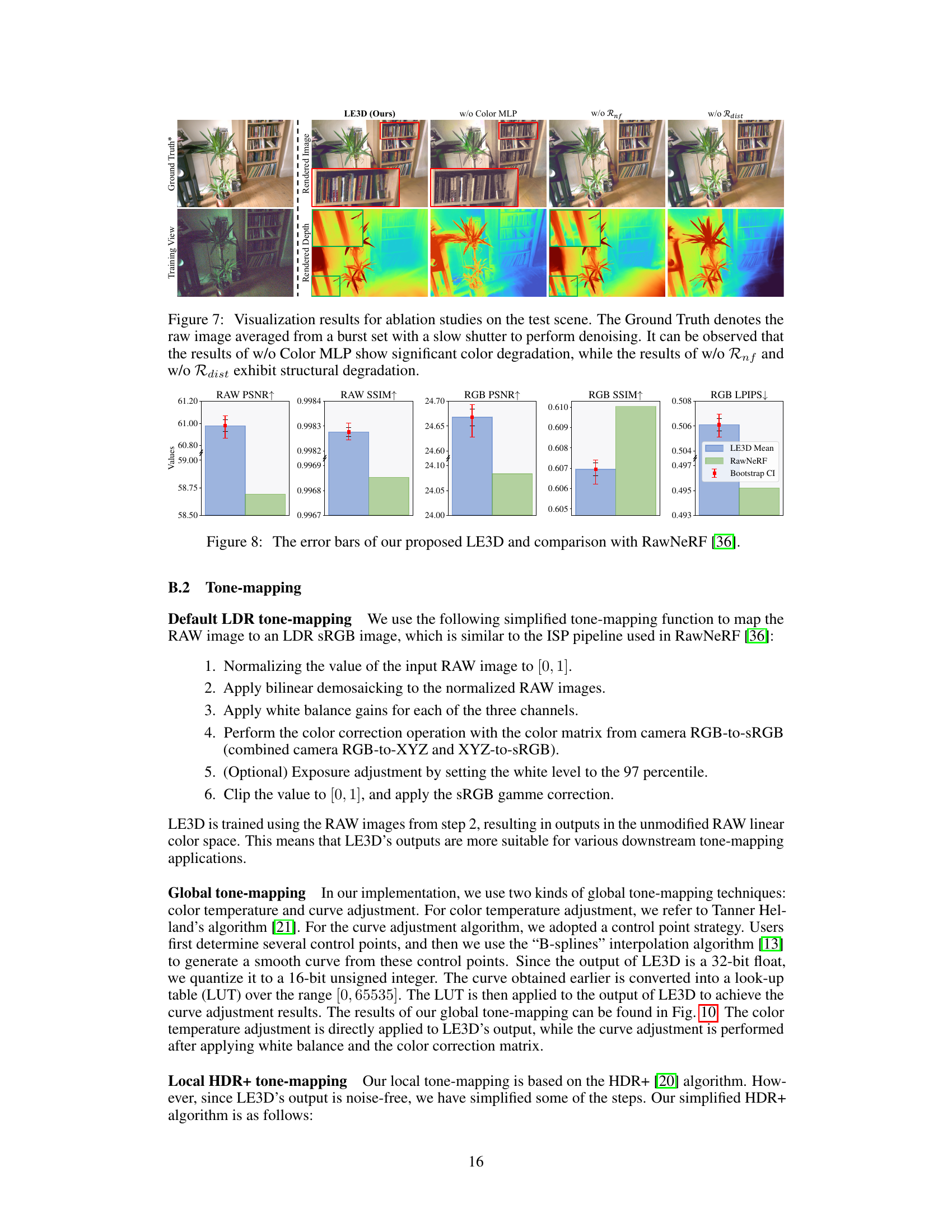

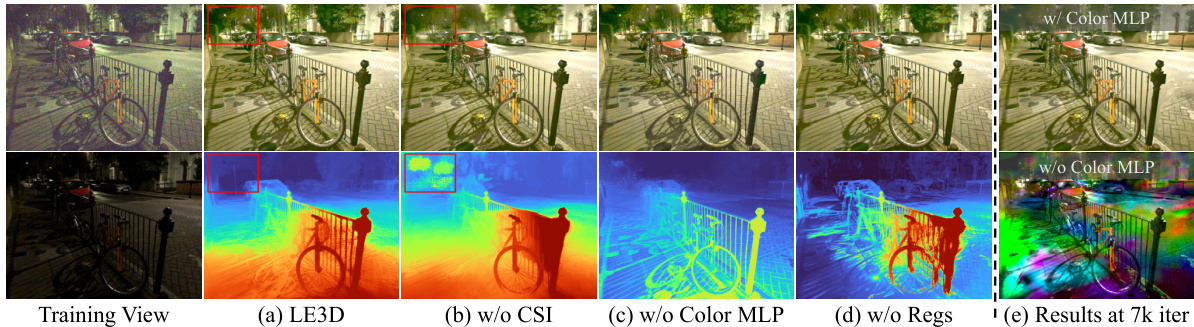

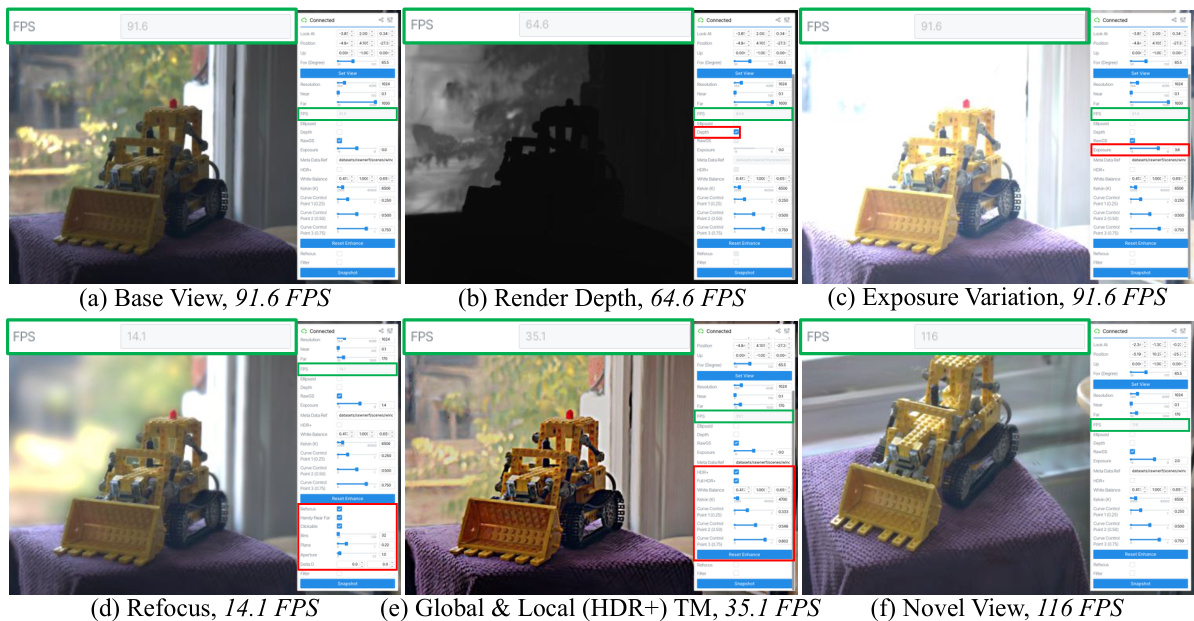

🔼 This figure demonstrates the ablation study of the proposed LE3D method. It shows the results of LE3D with and without each component of the proposed method (Cone Scatter Initialization (CSI), Color MLP, and Regularizations (Regs)). It also shows the results at an early stage (7k iterations) of training.

read the caption

Figure 4: Ablation studies on our purposed methods (Zoom-in for best view). CSI in (b) and Regs in (d) denote Cone Scatter Initialization and Regularizations, respectively. (e) shows the rendering result of LE3D w/ or w/o Color MLP in the early stages of training.

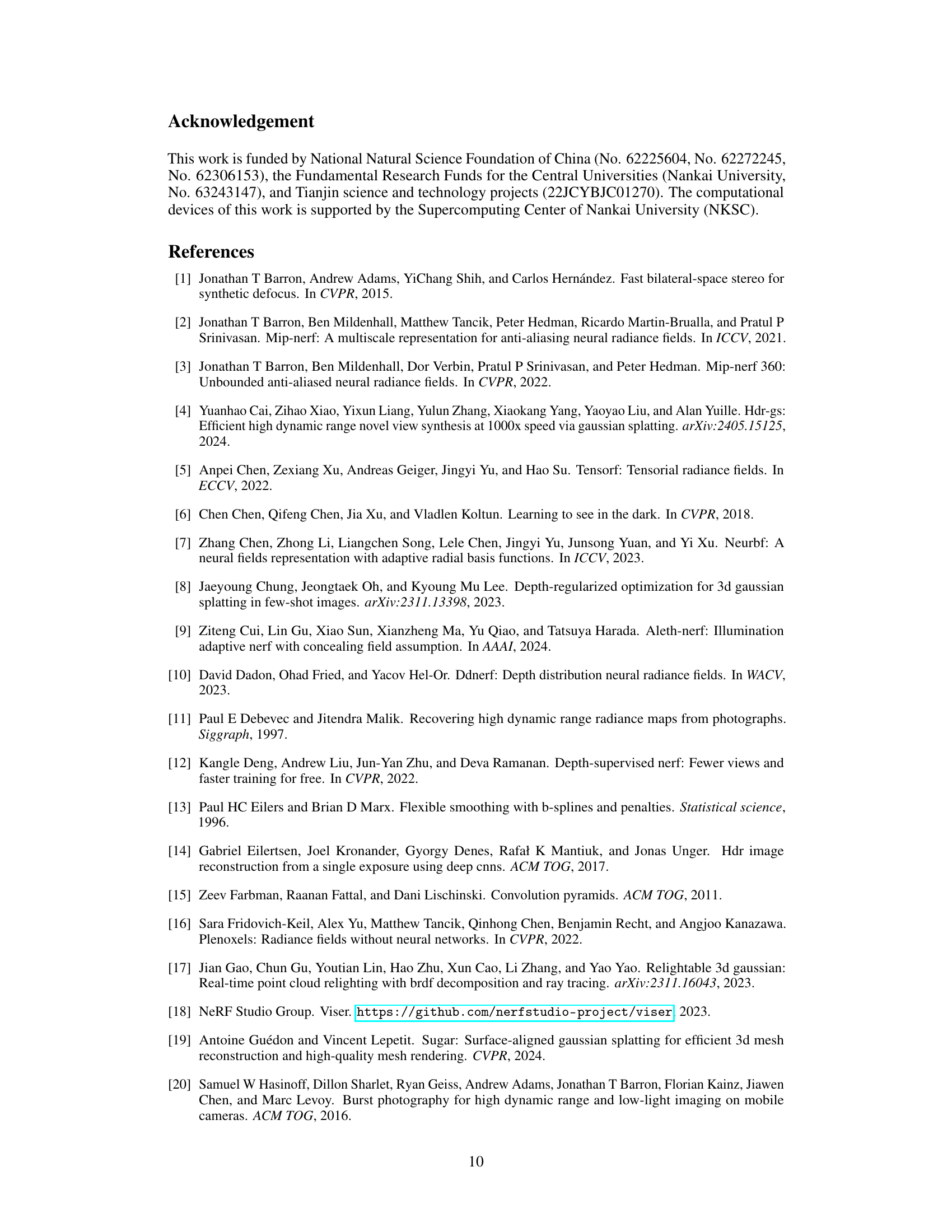

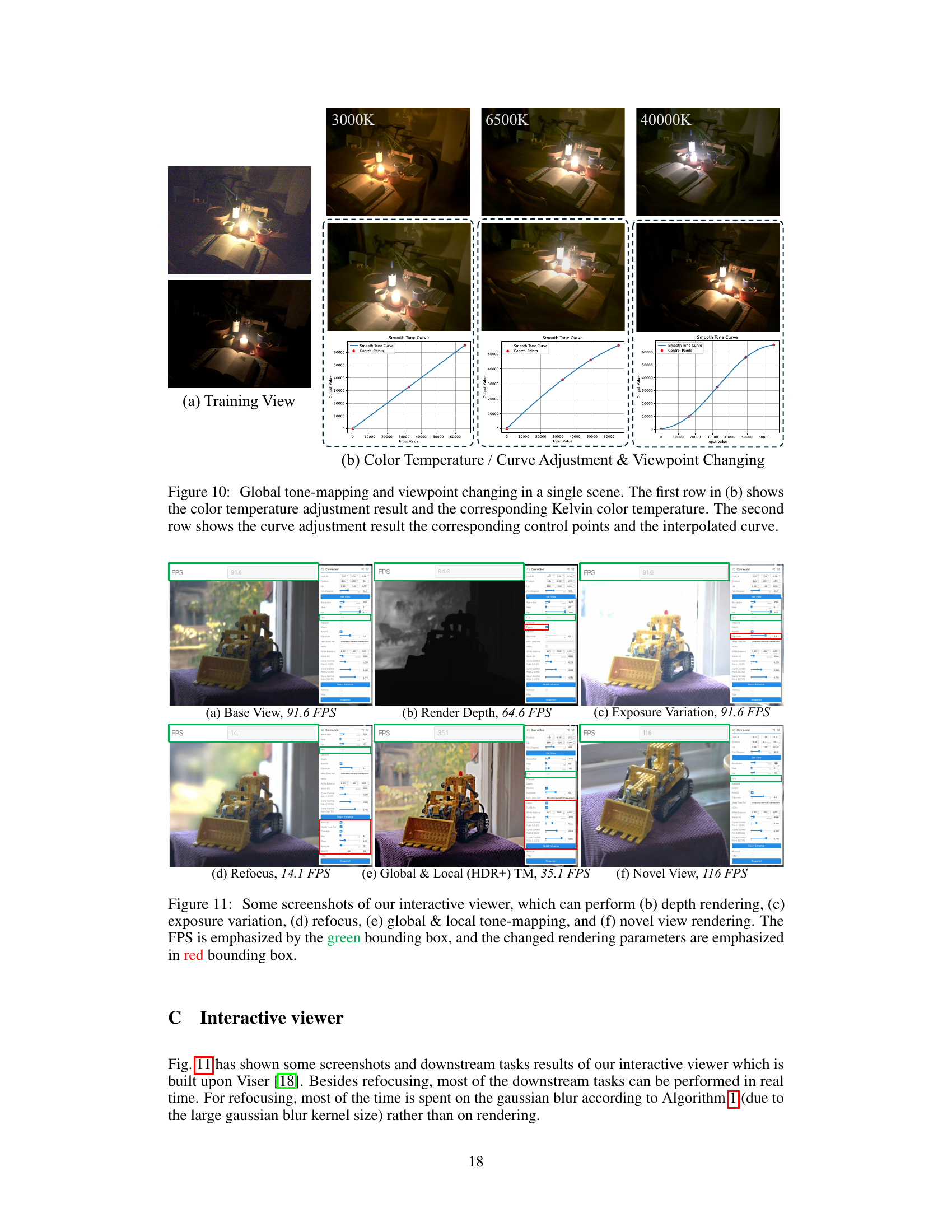

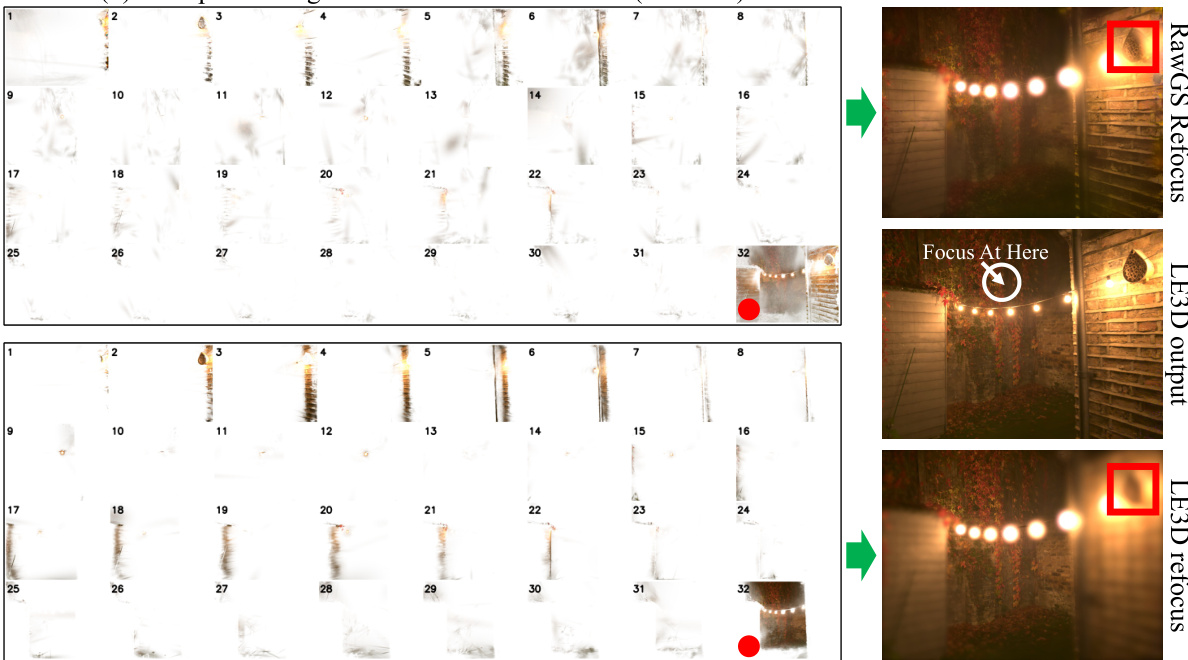

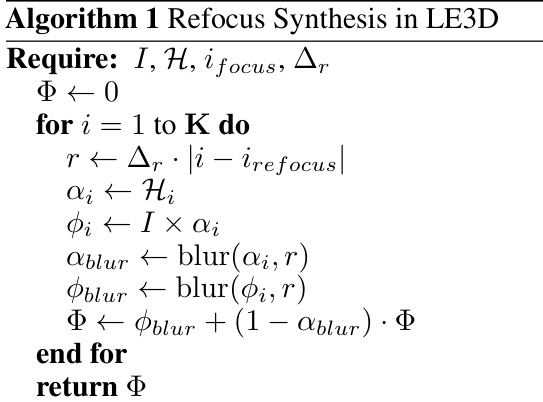

🔼 This figure demonstrates various applications of the LE3D model, showcasing its capabilities in refocusing, exposure variation, and tone mapping. Panel (a) shows the LE3D output, (b) shows the refocused image using LE3D, (c) depicts the depth map from LE3D. For comparison, panels (d) and (e) illustrate the results of using RawGS for refocusing and its corresponding depth map. Panels (f) and (g) illustrate the capabilities of LE3D for exposure variation and combined global/local tone mapping, highlighting the flexibility and real-time processing potential.

read the caption

Figure 5: LE3D supports various applications. RawGS* in (d) denotes using LE3D's rendered image and RawGS's structure information as input for refocusing. (c, e) are the weighted depth rendered by LE3D and RawGS, respectively. (f) shows the same scene rendered by LE3D with different exposure settings. In (g), the '→' denotes global tone-mapping, while the '→' represents local tone-mapping.

🔼 This figure presents an ablation study of the proposed LE3D method. It shows the impact of different components of LE3D on the final rendering result. The ablation study investigates the effect of removing the Cone Scatter Initialization (CSI), the Color MLP, and the depth distortion and near-far regularizations. The results demonstrate the importance of each component for achieving high-quality results.

read the caption

Figure 4: Ablation studies on our purposed methods (Zoom-in for best view). CSI in (b) and Regs in (d) denote Cone Scatter Initialization and Regularizations, respectively. (e) shows the rendering result of LE3D w/ or w/o Color MLP in the early stages of training.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of LE3D against other novel view synthesis methods. It showcases the superior noise resistance and detail preservation of LE3D, especially in distant scene elements. The speed improvements are highlighted, with LE3D rendering up to 6000x faster than other methods. The top row displays post-processed images for better comparison, while the bottom row shows the direct output images.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visual comparison between LE3D and other reconstruction methods (Zoom-in for best view). The training view contains two parts: the post-processed RAW image with linear brightness enhancement (up) and the image directly output by the device (down). By comparison to the 3DGS-based method, LE3D recovers sharper details in the distant scene and is more resistant to noise. Additionally, compared to NeRF-based methods, LE3D achieves comparable results with 3000×-6000× improvement in rendering speed.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of LE3D against other reconstruction methods (LDR-NeRF, LDR-3DGS, RawNeRF, and RawGS). The top row shows the training view images, including the post-processed linear brightness enhanced images and the device output images. The bottom row shows the reconstruction results from each method. LE3D outperforms other methods in terms of detail preservation in distant areas and noise resistance while achieving 3000-6000x faster rendering speed compared to NeRF-based methods.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visual comparison between LE3D and other reconstruction methods (Zoom-in for best view). The training view contains two parts: the post-processed RAW image with linear brightness enhancement (up) and the image directly output by the device (down). By comparison to the 3DGS-based method, LE3D recovers sharper details in the distant scene and is more resistant to noise. Additionally, compared to NeRF-based methods, LE3D achieves comparable results with 3000×-6000× improvement in rendering speed.

🔼 This figure compares the results of LE3D with other methods such as LDR-NeRF, LDR-3DGS, RawNeRF, and RawGS. The top row shows the training view, which is a post-processed RAW image with linear brightness enhancement and the actual image output from the device. The bottom row shows the results of novel view synthesis. LE3D shows superior detail preservation in the distant scene, better noise resistance compared to 3DGS methods, and comparable performance to NeRF-based methods but with significantly higher rendering speed (3000x-6000x).

read the caption

Figure 3: Visual comparison between LE3D and other reconstruction methods (Zoom-in for best view). The training view contains two parts: the post-processed RAW image with linear brightness enhancement (up) and the image directly output by the device (down). By comparison to the 3DGS-based method, LE3D recovers sharper details in the distant scene and is more resistant to noise. Additionally, compared to NeRF-based methods, LE3D achieves comparable results with 3000×-6000× improvement in rendering speed.

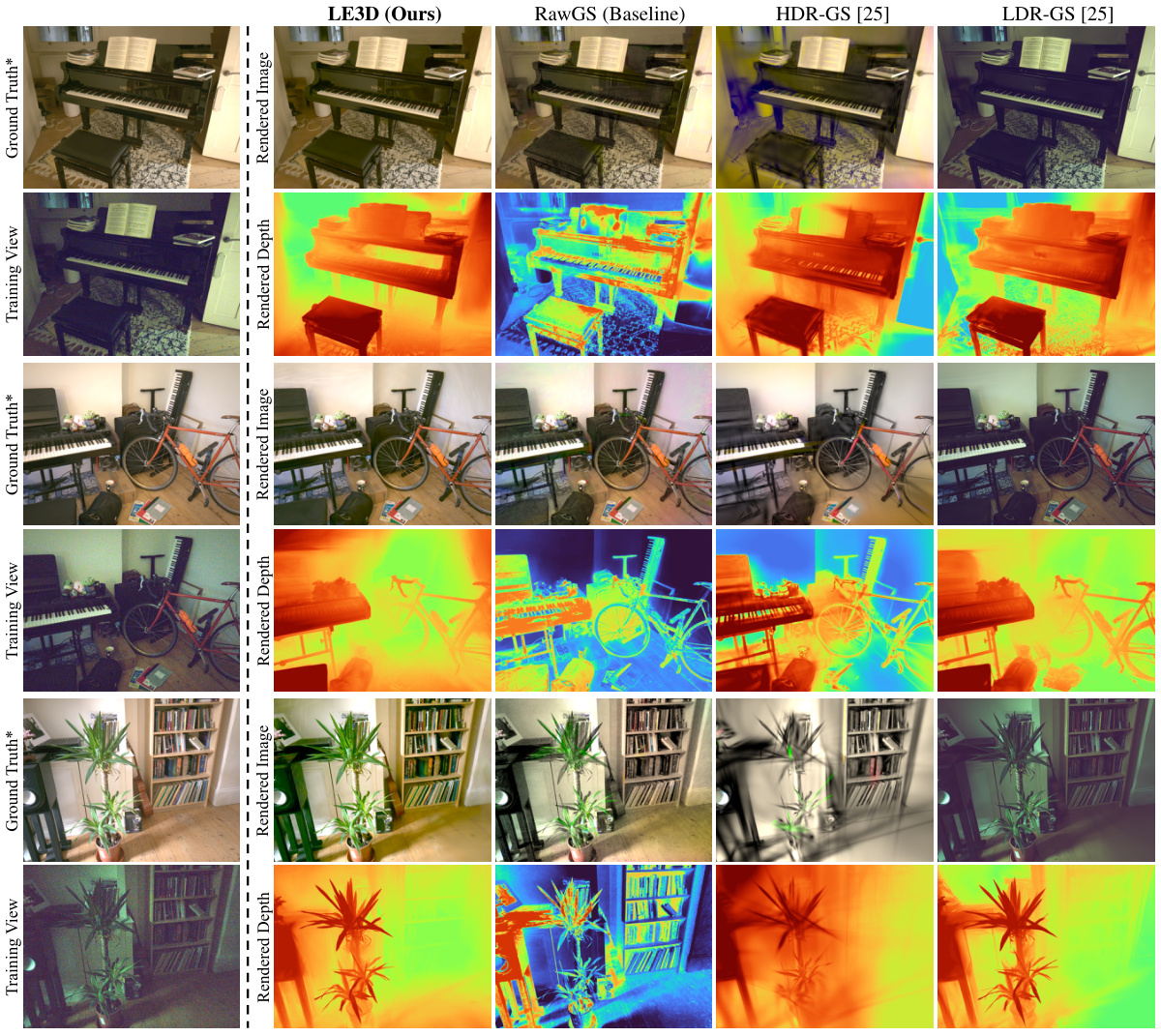

🔼 This figure compares the visual results of LE3D against other reconstruction methods like RawNeRF, LDR-GS, HDR-GS, and LDR-NeRF. It demonstrates that LE3D shows improved detail in distant scenes and better noise resistance compared to 3DGS-based methods. Furthermore, LE3D matches the performance of NeRF-based methods while achieving significantly faster rendering speeds.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visual comparison between LE3D and other reconstruction methods (Zoom-in for best view). The training view contains two parts: the post-processed RAW image with linear brightness enhancement (up) and the image directly output by the device (down). By comparison to the 3DGS-based method, LE3D recovers sharper details in the distant scene and is more resistant to noise. Additionally, compared to NeRF-based methods, LE3D achieves comparable results with 3000×-6000× improvement in rendering speed.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of LE3D with other reconstruction methods (LDR-NeRF, LDR-3DGS, RawNeRF, RawGS). The top row shows the training views, which consist of a preprocessed RAW image and the image directly output from the device. Subsequent rows compare the results from each method for the same scene, highlighting LE3D’s superior detail preservation in distant views, noise resilience, and significant speed advantage over volumetric rendering-based approaches.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visual comparison between LE3D and other reconstruction methods (Zoom-in for best view). The training view contains two parts: the post-processed RAW image with linear brightness enhancement (up) and the image directly output by the device (down). By comparison to the 3DGS-based method, LE3D recovers sharper details in the distant scene and is more resistant to noise. Additionally, compared to NeRF-based methods, LE3D achieves comparable results with 3000×-6000× improvement in rendering speed.

🔼 This figure compares the results of LE3D with other reconstruction methods (LDR-NeRF, LDR-3DGS, RawNeRF, RawGS). It showcases the training view (post-processed RAW image and directly output image from device), rendered images and rendered depth maps for each method. LE3D shows improvements over other methods in terms of detail preservation in distant scenes, noise resistance and rendering speed.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visual comparison between LE3D and other reconstruction methods (Zoom-in for best view). The training view contains two parts: the post-processed RAW image with linear brightness enhancement (up) and the image directly output by the device (down). By comparison to the 3DGS-based method, LE3D recovers sharper details in the distant scene and is more resistant to noise. Additionally, compared to NeRF-based methods, LE3D achieves comparable results with 3000×-6000× improvement in rendering speed.

🔼 This figure compares the visual results of LE3D with other reconstruction methods. The top row shows the training view, including both the preprocessed RAW images and images directly from the device. The following rows show results from LDR-NeRF, LDR-3DGS, RawNeRF, RawGS, and LE3D, demonstrating LE3D’s superior detail preservation in distant scenes and noise resistance, along with its significantly faster rendering speed compared to other methods.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visual comparison between LE3D and other reconstruction methods (Zoom-in for best view). The training view contains two parts: the post-processed RAW image with linear brightness enhancement (up) and the image directly output by the device (down). By comparison to the 3DGS-based method, LE3D recovers sharper details in the distant scene and is more resistant to noise. Additionally, compared to NeRF-based methods, LE3D achieves comparable results with 3000×-6000× improvement in rendering speed.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of LE3D against other 3DGS-based methods. The comparison shows rendered images, rendered depth maps and a ground truth image (averaged from multiple exposures to reduce noise). LE3D demonstrates superior noise resistance and color representation, especially in low-light conditions. It also provides smoother and more accurate depth map reconstruction.

read the caption

Figure 14: Comparison between LE3D and other 3DGS-based methods (Zoom-in for best view). All the results are the direct output of each model, not being applied by affine alignment. The Ground Truth denotes the raw image averaged from a burst set with a slow shutter to perform denoising.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of LE3D against several state-of-the-art methods for HDR view synthesis using the RawNeRF dataset. Metrics include PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS for both RAW and sRGB images. Training time (in GPU hours) and rendering speed (FPS) are also reported. The table highlights LE3D’s comparable performance to existing methods while achieving a significantly faster rendering speed (4000x).

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the test scenes of the RawNeRF [36] dataset. The best result is in bold whereas the second best one is in underlined. TM indicates whether the tone-mapping function can be replaced for HDR rendering. For methods where the tone-mapping function can be replaced, the metrics on sRGB are calculated using LDR tone-mapping for a fair comparison. The FPS measurement is conducted at a 2K (2016×1512) resolution. Train denotes the training time of the method, measured in GPU×H. LE3D achieves comparable performance with previous volumetric rendering based methods (RawNeRF [36]), but with 4000× faster rendering speed.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of LE3D against several state-of-the-art methods for HDR view synthesis using the RawNeRF dataset. Metrics include PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS for both RAW and sRGB images. Training time (GPU hours) and rendering speed (frames per second, FPS) are also reported. The table highlights LE3D’s comparable performance to existing methods but with significantly faster rendering speeds and shorter training times.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the test scenes of the RawNeRF [36] dataset. The best result is in bold whereas the second best one is in underlined. TM indicates whether the tone-mapping function can be replaced for HDR rendering. For methods where the tone-mapping function can be replaced, the metrics on sRGB are calculated using LDR tone-mapping for a fair comparison. The FPS measurement is conducted at a 2K (2016×1512) resolution. Train denotes the training time of the method, measured in GPU×H. LE3D achieves comparable performance with previous volumetric rendering based methods (RawNeRF [36]), but with 4000× faster rendering speed.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of LE3D against other HDR view synthesis methods on the RawNeRF dataset. Metrics include PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS for both RAW and sRGB images, along with training time (in GPU hours) and FPS at 2K resolution. It highlights LE3D’s comparable performance to state-of-the-art methods but with significantly faster rendering and training times.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the test scenes of the RawNeRF [36] dataset. The best result is in bold whereas the second best one is in underlined. TM indicates whether the tone-mapping function can be replaced for HDR rendering. For methods where the tone-mapping function can be replaced, the metrics on sRGB are calculated using LDR tone-mapping for a fair comparison. The FPS measurement is conducted at a 2K (2016×1512) resolution. Train denotes the training time of the method, measured in GPU×H. LE3D achieves comparable performance with previous volumetric rendering based methods (RawNeRF [36]), but with 4000× faster rendering speed.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of LE3D against other state-of-the-art methods for HDR view synthesis on the RawNeRF dataset. Metrics include PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS for both RAW and sRGB color spaces, frames per second (FPS), and training time (GPU hours). It highlights LE3D’s superior speed and comparable performance to existing methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the test scenes of the RawNeRF [36] dataset. The best result is in bold whereas the second best one is in underlined. TM indicates whether the tone-mapping function can be replaced for HDR rendering. For methods where the tone-mapping function can be replaced, the metrics on sRGB are calculated using LDR tone-mapping for a fair comparison. The FPS measurement is conducted at a 2K (2016×1512) resolution. Train denotes the training time of the method, measured in GPU×H. LE3D achieves comparable performance with previous volumetric rendering based methods (RawNeRF [36]), but with 4000× faster rendering speed.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of LE3D against several state-of-the-art methods for HDR view synthesis from noisy RAW images. Metrics include PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS for both RAW and sRGB color spaces. Training time (in GPU hours) and frame rate (FPS) are also shown. The table highlights LE3D’s comparable performance to existing methods, but with significantly faster rendering speed and shorter training time.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on the test scenes of the RawNeRF [36] dataset. The best result is in bold whereas the second best one is in underlined. TM indicates whether the tone-mapping function can be replaced for HDR rendering. For methods where the tone-mapping function can be replaced, the metrics on sRGB are calculated using LDR tone-mapping for a fair comparison. The FPS measurement is conducted at a 2K (2016×1512) resolution. Train denotes the training time of the method, measured in GPU×H. LE3D achieves comparable performance with previous volumetric rendering based methods (RawNeRF [36]), but with 4000× faster rendering speed.

Full paper#