TL;DR#

Community detection, identifying groups of similar nodes in networks, is crucial across many fields. Existing methods often struggle when dealing with multiple, unaligned (i.e., correlated but not perfectly matched) network datasets representing the same underlying system. This is because it is difficult to combine information from networks with differing node labels. This paper focuses on this challenging problem.

This research uses correlated stochastic block models (SBMs), a common network model, with two balanced communities to study this issue. By using a novel algorithmic approach combining information across multiple graphs via ‘k-core matching’, the study derives the precise information-theoretic threshold for exact community recovery with a constant number of correlated graphs. It also identifies regions in the parameter space where exact community recovery is possible even though latent vertex matchings are unrecoverable using fewer graphs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper significantly advances community detection research by precisely characterizing the information-theoretic threshold for exact community recovery using multiple correlated networks. It addresses a critical open problem, extending prior work on two graphs to any constant number of graphs. This opens avenues for improved algorithms and a deeper understanding of information aggregation in complex network data, impacting various fields using network analysis.

Visual Insights#

🔼 The figure shows the generation process of K correlated stochastic block models (CSBMs). First, a parent graph G0 is generated from a standard SBM. Then, K correlated graphs G1,…,GK are created by subsampling edges from G0 with probability s, and independently permuting the vertices. This process simulates real-world scenarios where multiple networks may share underlying community structures but have different vertex labels.

read the caption

Figure 1: Schematic showing the construction of multiple correlated SBMs (see text for details).

In-depth insights#

Multi-Network Info#

The concept of “Multi-Network Info” suggests a paradigm shift in data analysis, moving beyond the limitations of single-network perspectives. Harnessing information from multiple, correlated networks offers significant advantages. This approach could significantly enhance community detection and graph matching accuracy, particularly when individual networks provide insufficient information. The core challenge lies in effectively integrating information across networks, especially when the precise correspondence between nodes is unknown. Advanced techniques like k-core matching become crucial to bridge the gap between datasets, aligning nodes and aggregating insights. Successful multi-network analysis hinges on a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between community structure and network alignment, including the intricate characterization of information thresholds needed for precise recovery. The potential for novel algorithm development within this framework is immense, especially as the subtle relationships between multiple networks are mapped. Combining information effectively could lead to breakthroughs, even in cases where single-network analysis fails to reveal latent patterns. This innovative methodology holds vast potential across many application domains.

Exact Recovery Limits#

The heading ‘Exact Recovery Limits’ in a research paper likely explores the theoretical boundaries of perfectly recovering latent variables or structures from observed data. This could involve analyzing information-theoretic thresholds, where above a certain level of noise or sparsity, perfect recovery becomes impossible, regardless of the algorithm used. The analysis might focus on specific models (e.g., stochastic block models for community detection) and explore how parameters (e.g., edge probabilities, community sizes, number of graphs) influence these limits. The key insights would be identifying sharp phase transitions, where a small change in a parameter drastically alters the possibility of exact recovery, and understanding the interplay between model parameters and recovery difficulty. The discussion might also cover the computational complexity—whether achieving exact recovery is feasible within reasonable time constraints—and compare the theoretical limits to the performance of existing algorithms, highlighting any gaps between what’s theoretically achievable and what’s practically attainable. Finally, extensions to more complex settings (e.g., multiple correlated networks, non-parametric models) are often a focus, to demonstrate the robustness or limitations of the findings.

K-Core Matching Ext#

The extension of k-core matching to more than two graphs presents a significant challenge. In the original k-core matching algorithm for two graphs, the method finds a maximum k-core subgraph in the intersection graph formed by aligning the two input graphs. Extending this to multiple graphs requires a more sophisticated approach, as the optimal alignment is no longer guaranteed to be pairwise. One might consider approaches involving iterative refinement, where initial pairwise alignments are iteratively improved using information from other graphs, potentially utilizing the sizes of intersections of k-cores across multiple pairs. However, the computational complexity and theoretical guarantees for such methods would need careful consideration. Another strategy could involve creating a unified representation of all graphs (e.g. a hypergraph), finding the k-core in that representation, and then extracting the individual node mappings from this combined structure. This technique might achieve superior accuracy but is likely to face an even greater computational hurdle. Ultimately, determining the theoretical limitations and developing efficient algorithms for extended k-core matching across numerous correlated graphs remains a crucial open problem, and there are many potential algorithmic solutions that would need to be compared on real-world networks.

Algorithmic Challenges#

The algorithmic challenges in exact community recovery from multiple correlated networks stem from the need to reconcile conflicting information across graphs. Individual graphs may provide insufficient information for recovery, necessitating sophisticated integration techniques. The problem is further complicated by the lack of alignment between graphs, demanding effective graph matching algorithms. These algorithms must be robust to noise and handle the subtle interplay between community structure and graph topology. Moreover, efficiently synthesizing data from potentially many graphs poses significant computational hurdles. The core challenge lies in developing algorithms that can efficiently combine noisy, partially matched data from multiple graphs to accurately infer latent community structures, surpassing the limitations of individual networks.

Future Research#

The paper’s open questions section points towards several promising avenues for future research. Efficient algorithms are crucial, as the current theoretical results don’t guarantee efficient computation. The challenge lies in developing polynomial-time algorithms that integrate information from multiple graph matchings effectively. General block models beyond the simple two-community setting present a significant hurdle, requiring extensions of the theoretical framework to accommodate more complex community structures. Alternative graph models and correlation structures warrant investigation, as the current model may not capture the nuances of real-world network data. Finally, the interplay between community recovery and graph matching, especially the conditions when exact recovery is possible despite imperfect matching, demands further exploration to fully characterize their relationship. Addressing these questions would significantly advance our understanding of community detection and graph matching in complex networked systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

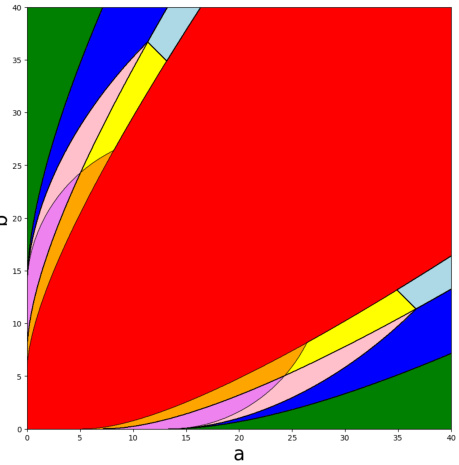

🔼 This phase diagram shows the different regions of the parameter space (a, b) for fixed s, where exact community recovery is possible or impossible with different numbers of correlated graphs (1, 2, or 3). Each region represents a different scenario regarding the possibility of exact recovery with the available graphs and graph matching results.

read the caption

Figure 2: Phase diagram for exact community recovery for three graphs with fixed s, and a ∈ [0, 40], b ∈ [0, 40] on the axes. Green region: exact community recovery is possible from G₁ alone; Cyan region: exact community recovery is impossible from G₁ alone, but exact graph matching of G₁ and G2 is possible, and subsequently exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2); Dark Blue region: exact community recovery is impossible from G₁ alone, exact graph matching is also impossible from (G1, G2), yet exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2); Pink region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2) (even though it would be possible if π₁₂ were known), yet exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Violet region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2, G3) (even though it would be possible from (G1, G2) if π₁₂ were known), yet exact graph matching is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Light Green region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2), but exact graph matching of graph pairs is possible, and subsequently exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Grey region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2), exact graph matching is also impossible from (G1, G2), but exact graph matching is possible from (G1, G2, G3), and subsequently exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Yellow region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2), exact graph matching is impossible from (G1, G2, G3), yet exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Orange region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2, G3) (even though it would be possible from (G1, G2, G3) if π* were known); Red region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2, G3) (even if π* is known).

🔼 This phase diagram shows the different regions where exact community recovery is possible or impossible for three correlated graphs, depending on the values of parameters a, b, and s. The diagram highlights the subtle interplay between exact community recovery, graph matching, and the number of graphs available. The main result of the paper is characterizing the phase transition boundaries and showing that exact community recovery can be possible using three graphs in situations where it’s impossible using only two.

read the caption

Figure 2: Phase diagram for exact community recovery for three graphs with fixed s, and a ∈ [0, 40], b ∈ [0, 40] on the axes. Green region: exact community recovery is possible from G₁ alone; Cyan region: exact community recovery is impossible from G₁ alone, but exact graph matching of G₁ and G2 is possible, and subsequently exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2); Dark Blue region: exact community recovery is impossible from G₁ alone, exact graph matching is also impossible from (G1, G2), yet exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2); Pink region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2) (even though it would be possible if π₁₂ were known), yet exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Violet region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2, G3) (even though it would be possible from (G1, G2) if π₁₂ were known), yet exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Light Green region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2), but exact graph matching of graph pairs is possible, and subsequently exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Grey region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2), exact graph matching is also impossible from (G1, G2), but exact graph matching is possible from (G1, G2, G3), and subsequently exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Yellow region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2), exact graph matching is impossible from (G1, G2, G3), yet exact community recovery is possible from (G1, G2, G3); Orange region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2, G3) (even though it would be possible from (G1, G2, G3) if π* were known); Red region: exact community recovery is impossible from (G1, G2, G3) (even if π* is known). The principal finding of this paper is the characterization of the Pink, Violet, Orange, Yellow, Grey, and Light Green regions.

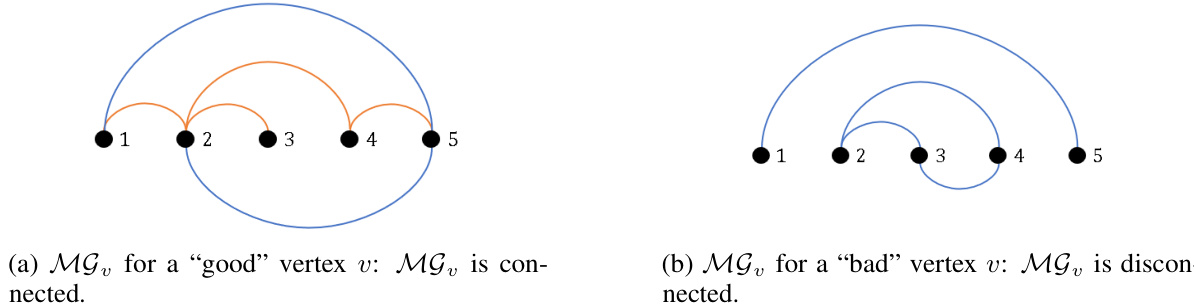

🔼 This figure shows a schematic representation of partial matchings obtained for three graphs. Panel (a) categorizes the vertices into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ vertices. Good vertices are involved in at least two matchings, while bad vertices are involved in at most one matching. Panel (b) shows a graph representation of the matchings between the three graphs, which highlights the relationship between pairwise partial matchings in the context of community recovery.

read the caption

Figure 3: Schematic landscape of partial matchings over three graphs.

🔼 This figure schematically illustrates the generation of multiple correlated stochastic block models (SBMs). It begins with a parent graph Go, which is an SBM itself. From Go, K correlated graphs (G1, …, GK) are created via independent subsampling of the edges from Go. Then, each graph Gi (where i>1) undergoes a random permutation of its vertices, represented by πij, resulting in unaligned graphs. This process mimics real-world scenarios where different network datasets might have mismatched vertex labels, despite underlying correlations.

read the caption

Figure 1: Schematic showing the construction of multiple correlated SBMs (see text for details).

🔼 The figure shows a schematic of how multiple correlated stochastic block models (SBMs) are constructed. It starts with a parent graph, G0, which is an SBM with community labels. Then, K correlated graphs (G1,…, GK) are created by independently subsampling edges from G0. Each graph Gi inherits the community labels from G0 but has its vertex labels permuted by a random permutation πi. This process simulates the scenario where multiple networks are available but their vertices are not aligned. The figure illustrates this process for K=3, showing the parent graph and the three correlated graphs, with the permutations explicitly shown. This construction helps analyze community recovery in scenarios with multiple correlated graphs.

read the caption

Figure 1: Schematic showing the construction of multiple correlated SBMs (see text for details).

Full paper#