TL;DR#

Current video-language models (VLMs) struggle to effectively represent video content for Large Language Models (LLMs). Existing methods often result in semantically entangled tokens, hindering efficient processing. This creates challenges in tasks like video question answering, where nuanced understanding of both visual and temporal aspects is critical.

Slot-VLM tackles this by introducing an Object-Event Slots (OE-Slots) module. OE-Slots cleverly decomposes video features into object-centric and event-centric representations, creating semantically disentangled tokens. These tokens, akin to words in text, are more easily processed by LLMs. The experimental results show that Slot-VLM significantly improves video question answering accuracy, surpassing state-of-the-art methods. This demonstrates the effectiveness of using decoupled visual tokens for enhanced video-language model performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in video-language modeling because it introduces a novel approach to efficiently represent video content for LLMs, addressing the limitations of existing methods. Its innovative Object-Event Slots module enables semantically decoupled video tokens, significantly improving video question-answering performance. This opens new avenues for creating more effective and efficient VLMs, impacting various video understanding tasks.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates different methods for aligning visual features with a large language model (LLM). (a) and (b) show existing methods using pooling or a Q-Former, resulting in tokens with mixed semantics. The proposed method (c and d) generates semantically separated object-centric and event-centric tokens, improving alignment with the LLM.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of methods for aligning visual features with LLM. Previous methods (a) and (b) leverage pooling or Q-Former to aggregate visual tokens, where each generated token contains coupled semantics. In contrast, we propose to generate semantically decoupled object-centric tokens as illustrated in (c), and event-centric tokens as illustrated in (d), to align with the LLM.

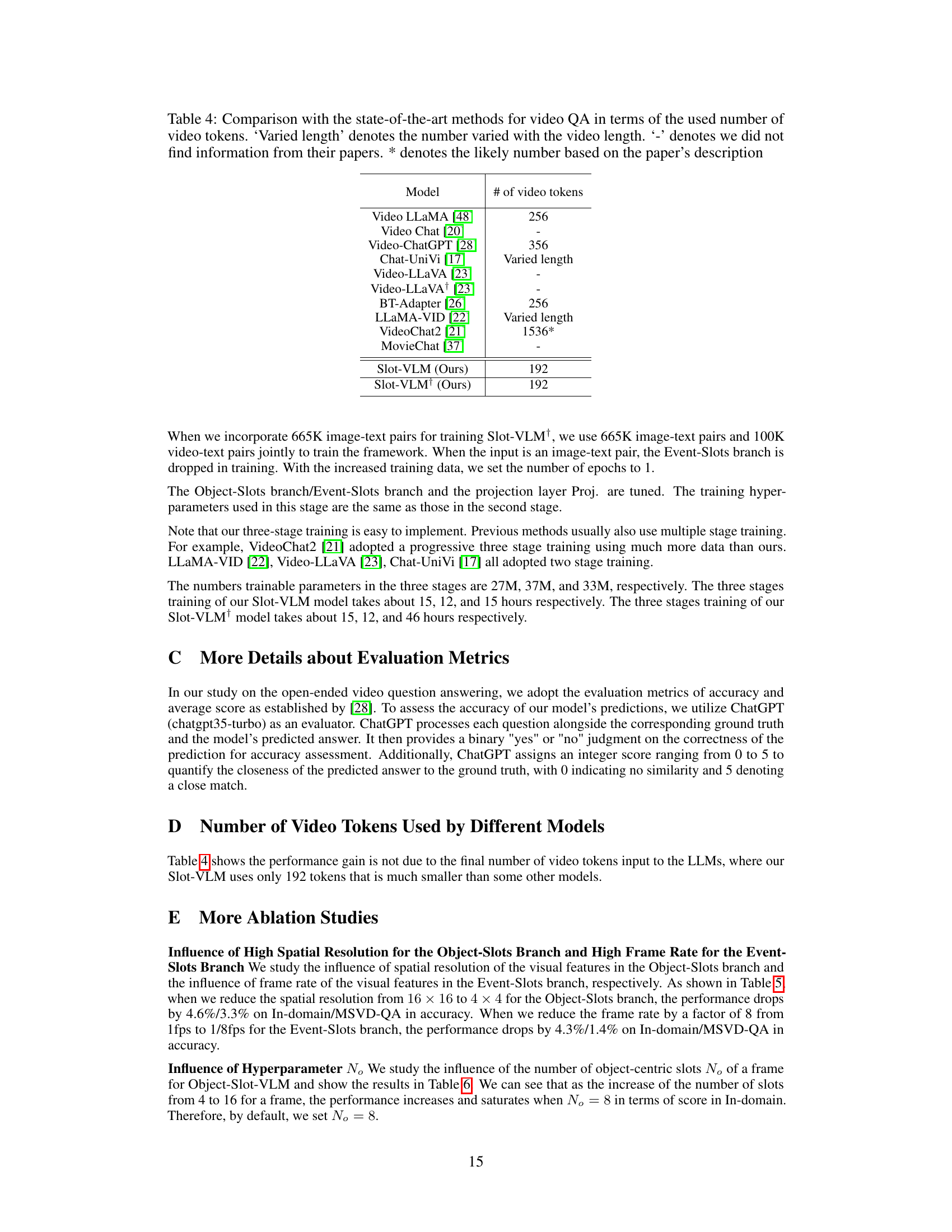

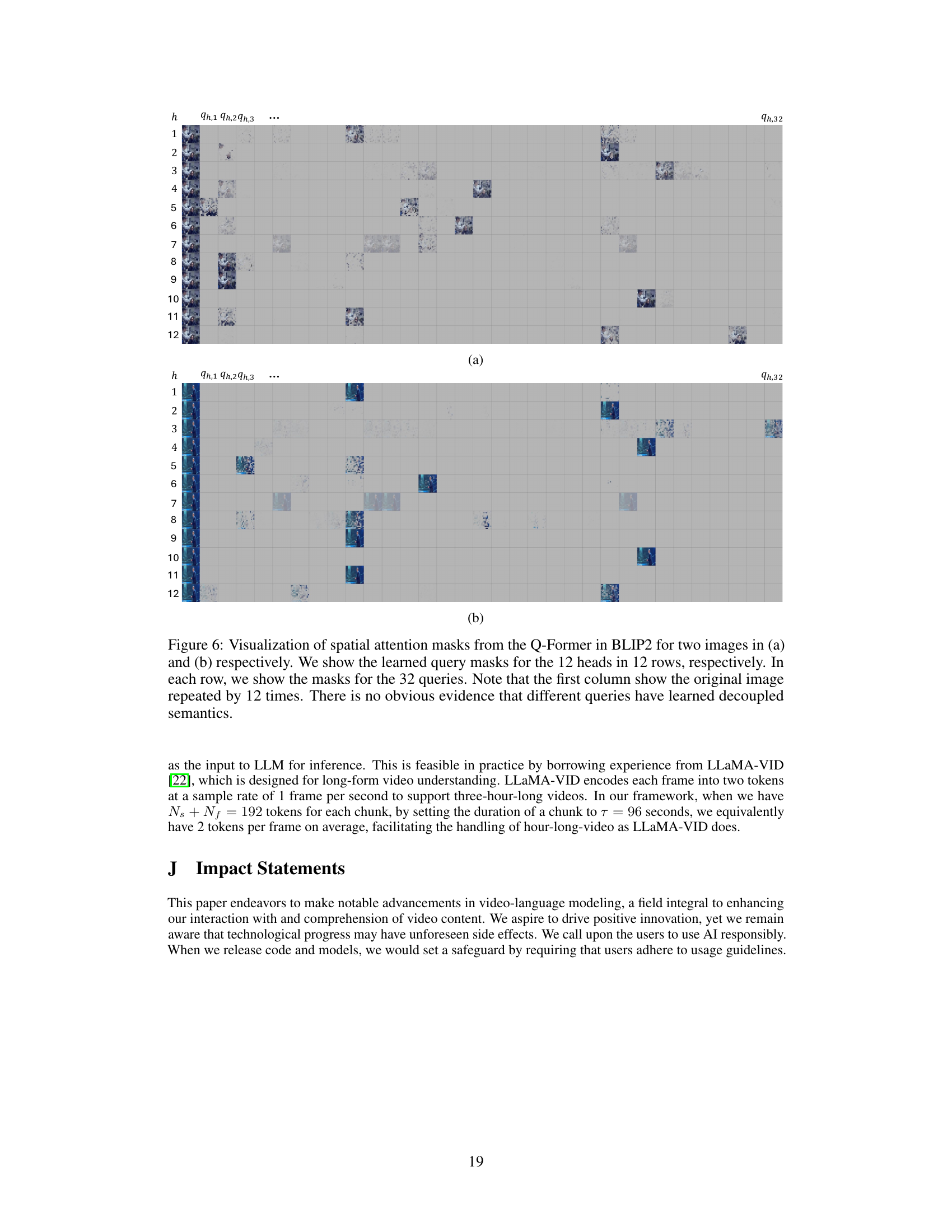

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed Slot-VLM model with other state-of-the-art video question answering (VQA) models. It shows the accuracy and average score on three benchmark datasets (MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, ActivityNet-QA). The table also indicates the instruction data used for training each model, the method used to connect vision features with the language model (LLM), and the number of video tokens used. The results highlight Slot-VLM’s superior performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

In-depth insights#

OE-Slots: Core Design#

The core design of OE-Slots revolves around adaptively aggregating dense video tokens from a vision encoder into a concise set of semantically meaningful slots. This aggregation process is not a simple pooling or transformation, but rather a two-branched architecture that captures both spatial object details and temporal event dynamics. The Object-Slots branch focuses on high spatial resolution but low temporal sampling, extracting detailed object information. Conversely, the Event-Slots branch emphasizes high temporal sampling but low spatial resolution, capturing event-centric features. The concatenation of these complementary slots forms a compact and semantically rich vision context, perfectly aligned with the input requirements of LLMs for effective video reasoning. This design is crucial in addressing the computational challenges and semantic redundancy inherent in processing large volumes of raw video data. The use of slot attention mechanisms further enhances the ability of the module to learn disentangled representations, resulting in efficient LLM inference and improved video understanding.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In this context, it would involve removing or altering parts of the Slot-VLM, such as the Object-Slots branch, Event-Slots branch, or the specific attention mechanisms used. By observing the performance changes after each ablation, researchers gain a granular understanding of each module’s impact on video question answering (VQA). The results would likely highlight the importance of both the spatial and temporal branches, demonstrating how effectively they capture object and event information respectively. A comparison of using Slot Attention vs. alternative aggregation techniques like Q-Former would also likely be included. This would demonstrate Slot-VLM’s superiority in producing semantically disentangled representations. The impact of hyperparameters, such as the number of slots or frame sampling rates, would also be investigated to reveal optimal model configurations. Ultimately, these ablation studies provide critical evidence supporting the design choices and effectiveness of Slot-VLM, showcasing the unique contribution of its modular architecture and demonstrating its advantage over existing approaches.

Visualizations#

The visualizations section of this research paper is crucial for understanding the model’s inner workings. Attention maps are effectively used to showcase the model’s focus on specific objects and events within video frames. The maps visually represent the attention weights assigned by different components of the model to different regions of the video, revealing which parts of the input are most influential in generating the output. Comparison of attention maps between the proposed model and baselines provides insights into the effectiveness of the proposed method at generating semantically-decoupled tokens. By comparing visualization across different models, we can see that the proposed Slot-VLM significantly improves the disentanglement of visual information, leading to more effective video reasoning. This visual approach to demonstrating the improved performance is compelling because it moves beyond simple quantitative results and shows the actual, qualitative differences. Clear labeling and color schemes in the figures aid in understanding and interpretation, adding to the clarity and impact of the visualization. Overall, the visualizations provide valuable insights into the functioning of the model, strengthening the paper’s argument and contributing to a more comprehensive understanding.

Long Videos#

Processing long videos presents unique challenges for video-language models (VLMs). The sheer volume of data necessitates efficient encoding to avoid computational bottlenecks. Existing methods, such as stacking frame-level features, become inefficient and may discard important temporal information. Semantic decomposition techniques, dividing the video into meaningful segments (objects and events), offer a promising solution. By focusing on key features and discarding redundancy, VLMs can better manage long videos while retaining crucial contextual information. This approach leads to more compact representations, facilitating effective interaction with large language models (LLMs) and enabling improved video question answering and other downstream tasks. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the ability to accurately segment videos into semantically meaningful units, which is an active area of research.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this Slot-VLM framework could explore several promising avenues. Improving the quality of slot attention mechanisms is crucial; current methods struggle with perfectly segmenting objects and events, impacting the semantic purity of generated tokens. Investigating alternative methods for generating semantically decoupled video tokens, beyond slot attention, could broaden the scope of the approach. Scaling Slot-VLM to handle extremely long videos presents a significant challenge. Efficiently processing hours-long videos likely requires incorporating temporal segmentation or summarization techniques. Exploring different visual encoders beyond CLIP, particularly those specialized for video, might improve overall performance. Furthermore, thorough investigation into the interaction between the design choices of object-centric and event-centric slots and LLM performance is warranted. This includes examining different numbers of slots and their impact on downstream tasks. Finally, applying this framework to other video-related tasks, such as video captioning and video retrieval, would demonstrate its generalizability and utility.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of Slot-VLM, a framework for video-language modeling. It shows how the input video is processed through an image encoder to extract video tokens. These tokens are then fed into an Object-Event Slots module which has two branches: one for object-centric slots (high spatial resolution, low frame rate) and one for event-centric slots (high frame rate, low spatial resolution). The resulting slots are then projected and combined with text input before being passed to a Large Language Model (LLM) for video reasoning.

read the caption

Figure 2: Flowchart of our proposed Slot-VLM for video understanding. Slot-VLM consists of a frozen image encoder, a learnable Object-Event Slots module (i.e., OE-Slots module), a projection layer, and a frozen LLM. The image encoder encodes the input video of T frames into a sequence of image features, resulting in extensive (H × W × T) video tokens. In order to obtain semantically decoupled and compact (reduced) video tokens as the vision context for aligning with LLM, our OE-Slots module learns to aggregate those tokens to object-centric tokens and event-centric tokens through the Object-Slots branch and the Event-Slots branch, respectively. The Object-Slots branch operates at low frame rate (t ≪T) but high spatial resolution in order to capture spatial objects through slot attention on each sampled frame. The Event-Slots branch operates at high frame rate but low spatial resolution (m = h × w, where h < H, w < W) in order to capture temporal dynamics through slot attention over each spatial position. The learned slots (tokens) from two branches are projected and inputted to LLM for video reasoning, together with the text.

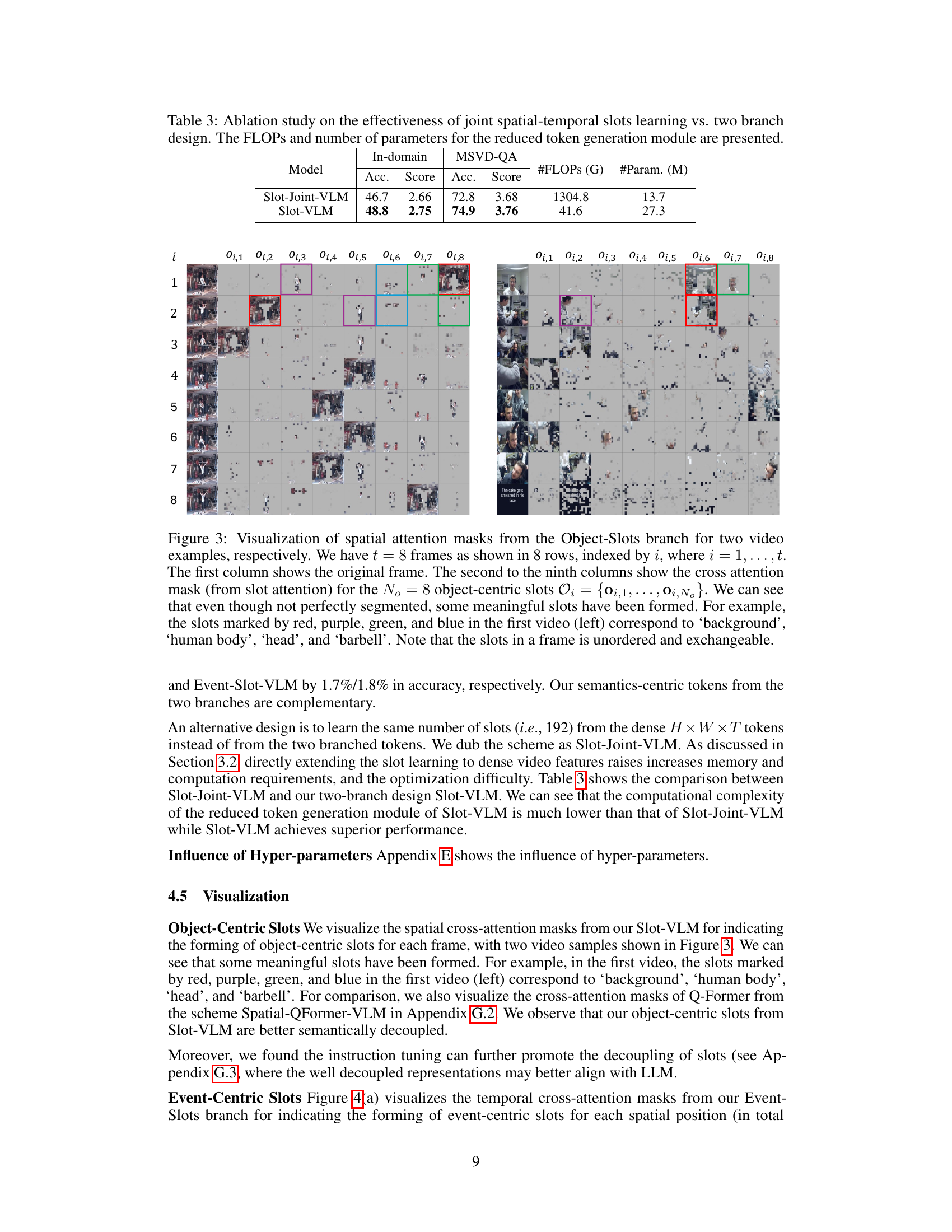

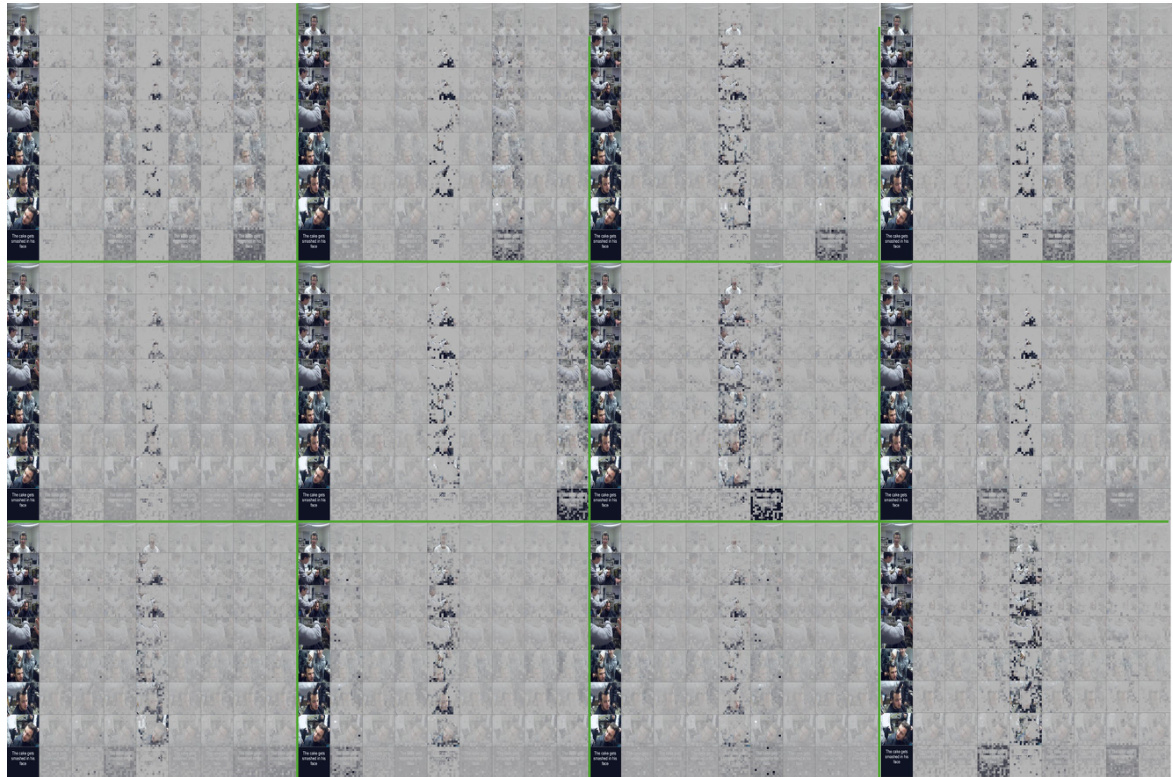

🔼 This figure visualizes the spatial attention masks from the Object-Slots branch of the Slot-VLM model. It shows how the model attends to different regions of the input frames to generate object-centric slots. Each row represents a frame, and each column represents a different slot. The color intensity of each cell indicates the attention weight. The examples provided demonstrate that the model learns to focus on semantically meaningful regions, such as background, human body parts, and objects.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visualization of spatial attention masks from the Object-Slots branch for two video examples, respectively. We have t = 8 frames as shown in 8 rows, indexed by i, where i = 1, ..., t. The first column shows the original frame. The second to the ninth columns show the cross attention mask (from slot attention) for the N° = 8 object-centric slots Oi = {0i,1,..., oi,No}. We can see that even though not perfectly segmented, some meaningful slots have been formed. For example, the slots marked by red, purple, green, and blue in the first video (left) correspond to 'background', 'human body', 'head', and 'barbell'. Note that the slots in a frame is unordered and exchangeable.

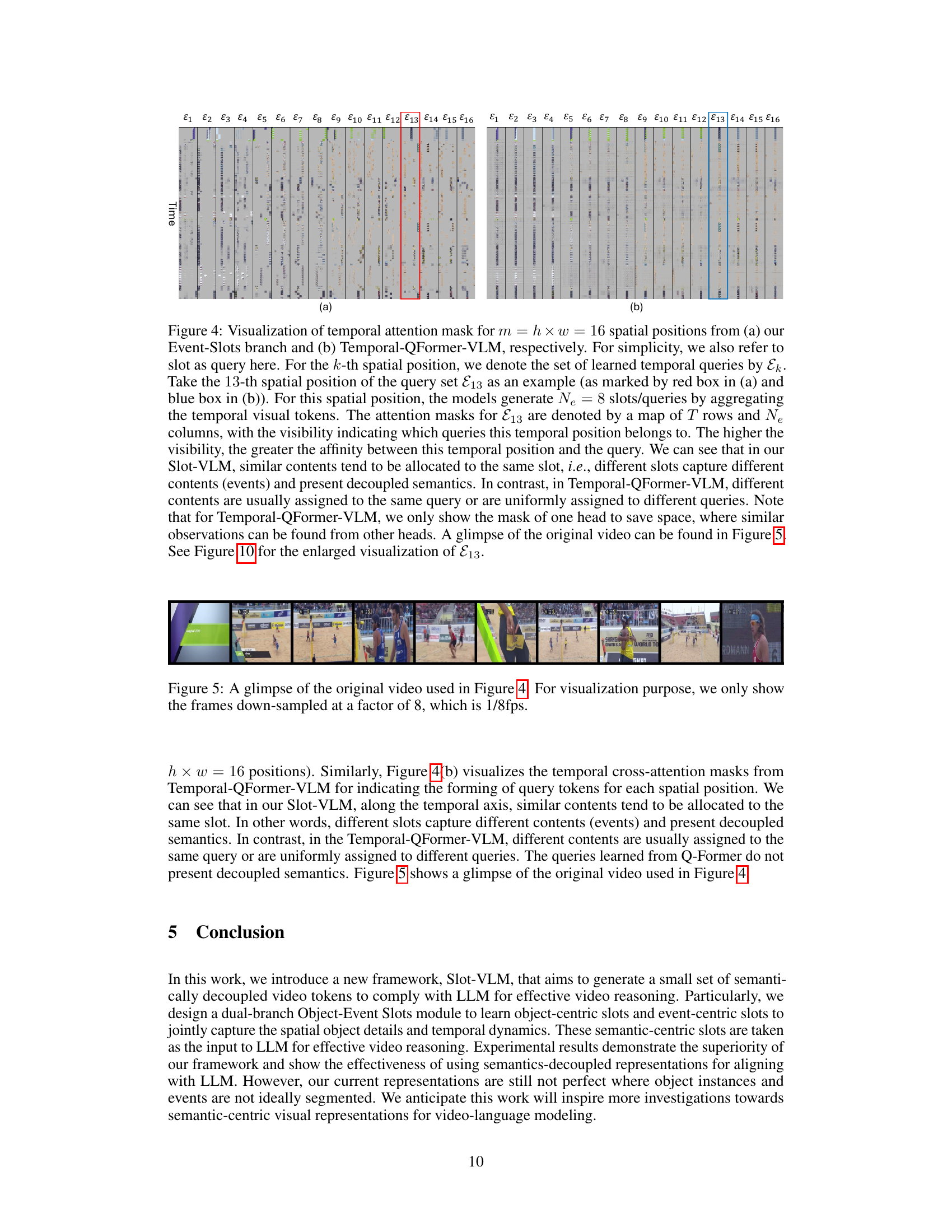

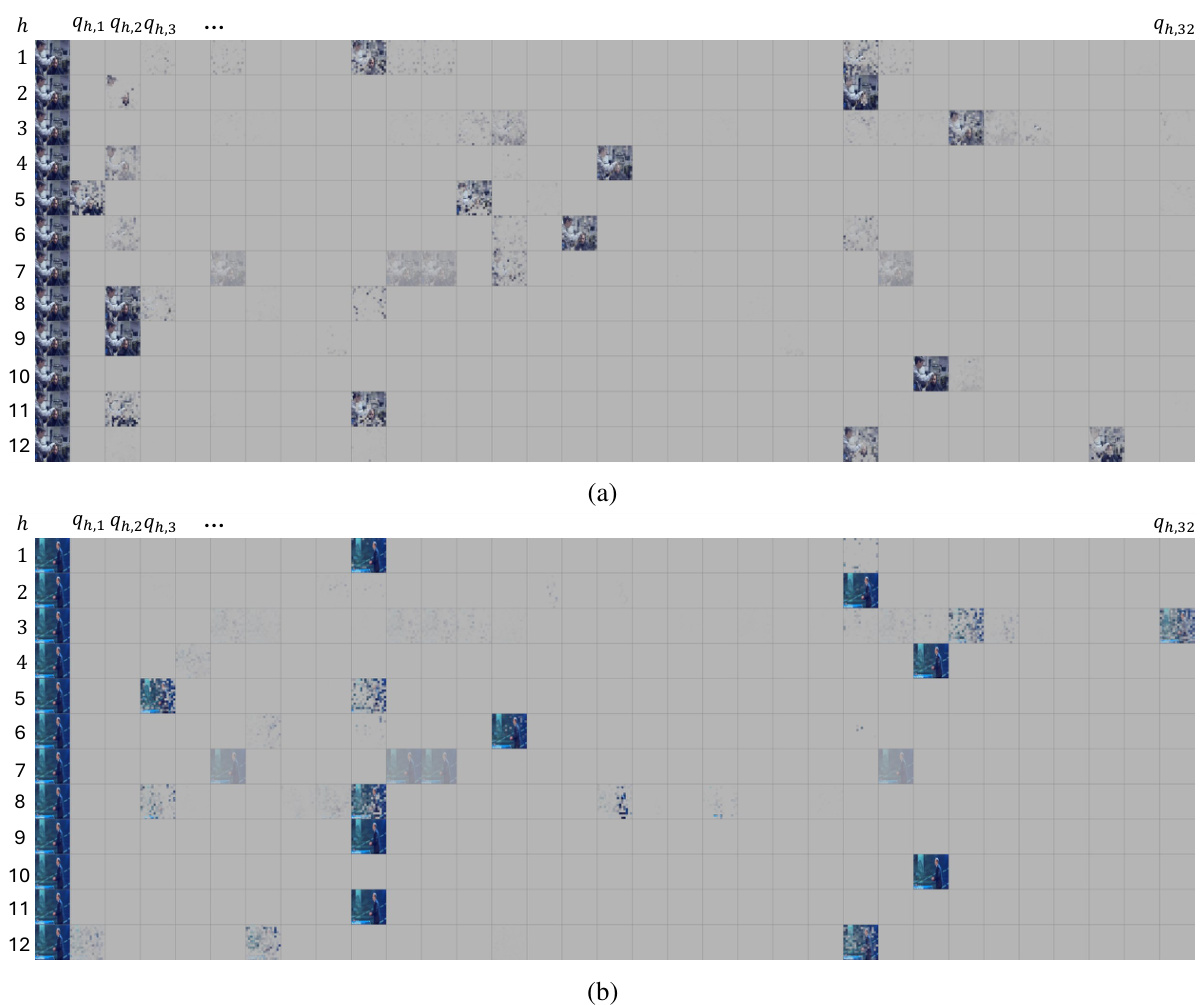

🔼 This figure visualizes the temporal attention masks from the Event-Slots branch of Slot-VLM and compares it with the Temporal-QFormer-VLM. It shows that Slot-VLM effectively groups similar temporal contents into the same slot, demonstrating disentangled semantics. In contrast, Temporal-QFormer-VLM shows less clear separation of semantics.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visualization of temporal attention mask for m = h × w = 16 spatial positions from (a) our Event-Slots branch and (b) Temporal-QFormer-VLM, respectively. For simplicity, we also refer to slot as query here. For the k-th spatial position, we denote the set of learned temporal queries by Ek. Take the 13-th spatial position of the query set E13 as an example (as marked by red box in (a) and blue box in (b)). For this spatial position, the models generate Ne = 8 slots/queries by aggregating the temporal visual tokens. The attention masks for E13 are denoted by a map of T rows and Ne columns, with the visibility indicating which queries this temporal position belongs to. The higher the visibility, the greater the affinity between this temporal position and the query. We can see that in our Slot-VLM, similar contents tend to be allocated to the same slot, i.e., different slots capture different contents (events) and present decoupled semantics. In contrast, in Temporal-QFormer-VLM, different contents are usually assigned to the same query or are uniformly assigned to different queries. Note that for Temporal-QFormer-VLM, we only show the mask of one head to save space, where similar observations can be found from other heads. A glimpse of the original video can be found in Figure 5. See Figure 10 for the enlarged visualization of E13.

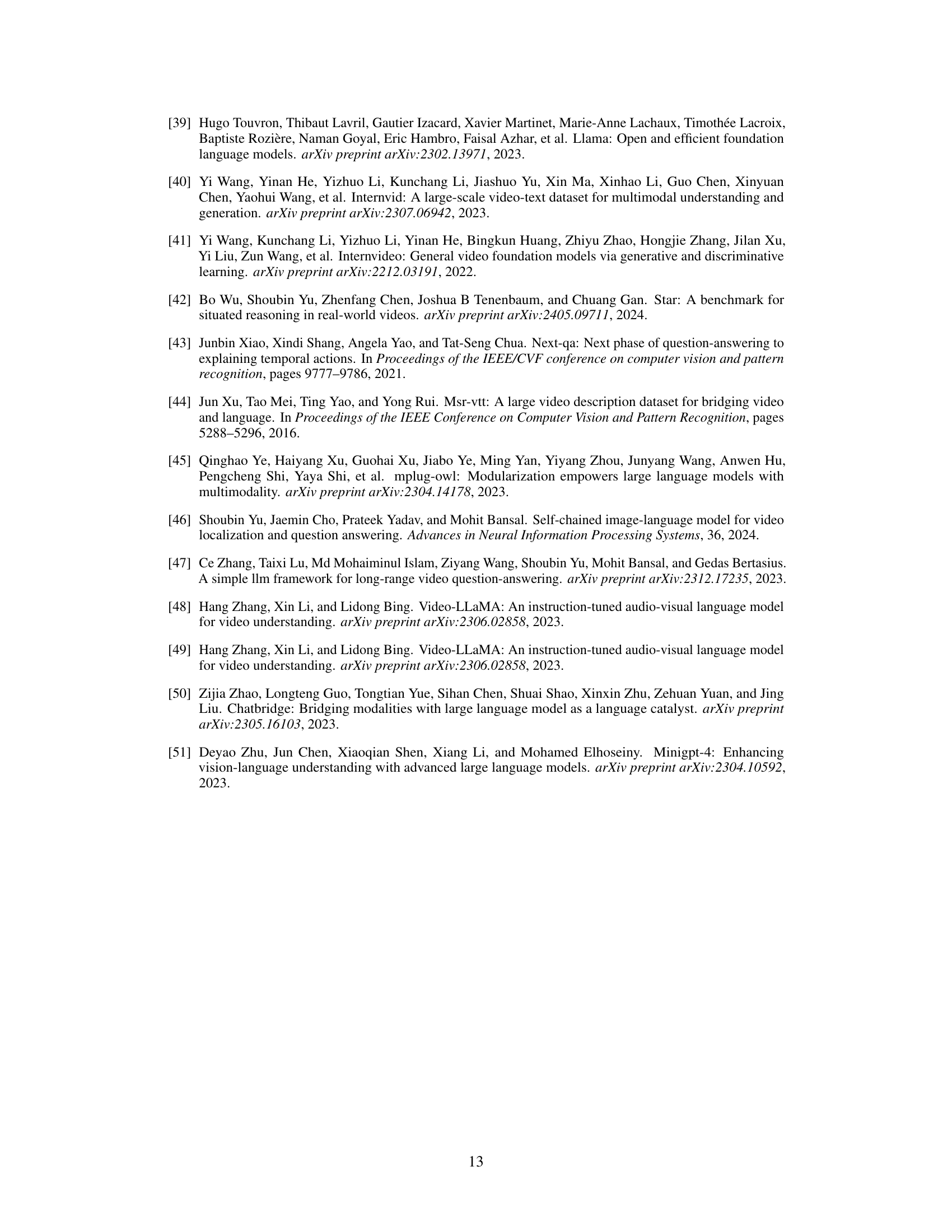

🔼 This figure shows a glimpse of the original video used to generate Figure 4, which visualizes the temporal attention masks. The frames shown here are down-sampled to 1/8th of the original frame rate for visualization purposes.

read the caption

Figure 5: A glimpse of the original video used in Figure 4. For visualization purpose, we only show the frames down-sampled at a factor of 8, which is 1/8fps.

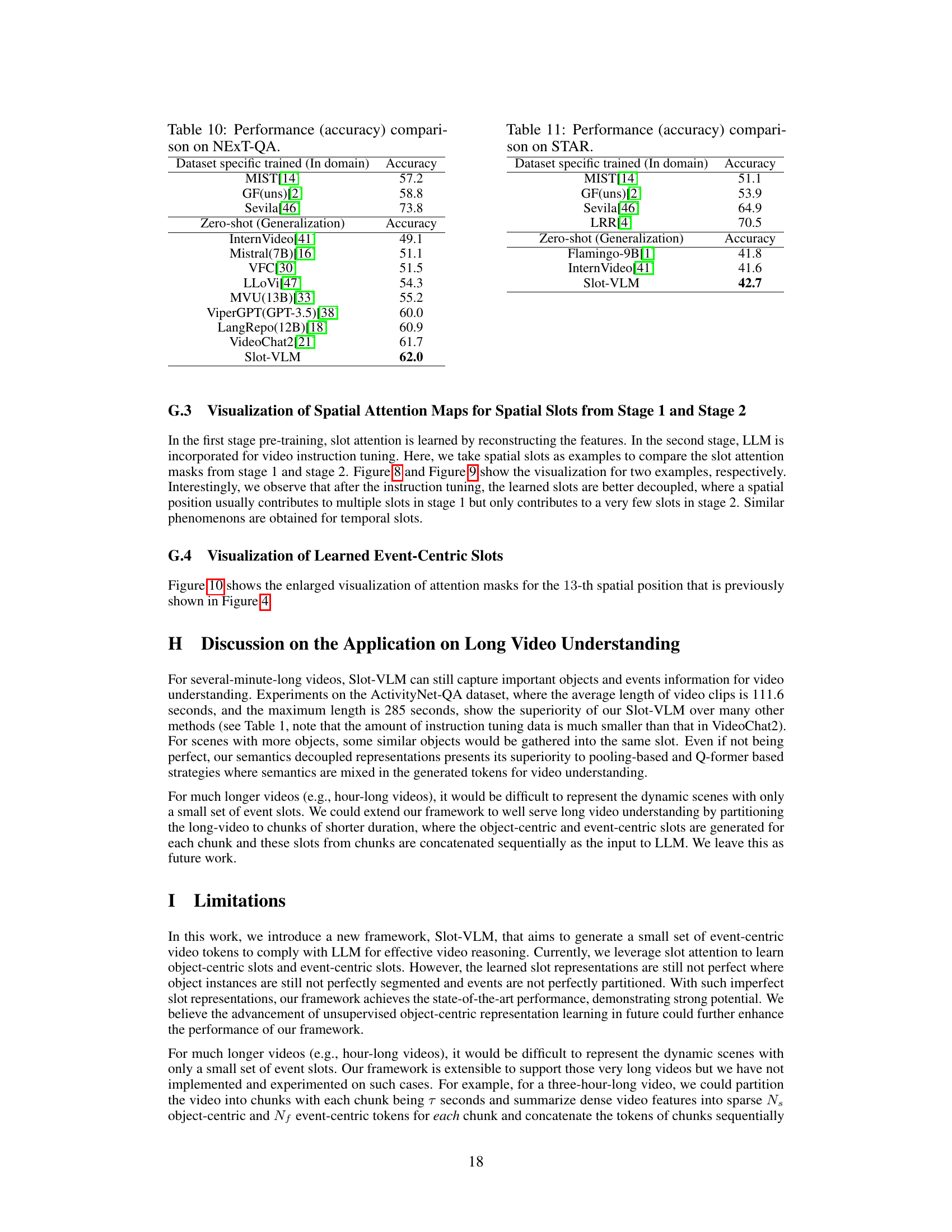

🔼 This figure visualizes spatial attention masks from the Q-Former in BLIP2, a visual language model. It shows the attention weights of 12 heads across 32 queries for two different images. The goal is to analyze if the Q-Former learns decoupled semantics for these queries, meaning if individual queries focus on distinct semantic aspects of the image. The visualization reveals that there’s no clear evidence of decoupled semantics, suggesting that queries capture mixed semantic information.

read the caption

Figure 6: Visualization of spatial attention masks from the Q-Former in BLIP2 for two images in (a) and (b) respectively. We show the learned query masks for the 12 heads in 12 rows, respectively. In each row, we show the masks for the 32 queries. Note that the first column show the original image repeated by 12 times. There is no obvious evidence that different queries have learned decoupled semantics.

🔼 This figure visualizes spatial attention masks from the Object-Slots branch of the Slot-VLM model for two video examples. Each row represents one of the 8 frames used, and each column represents one of the 8 object-centric slots. The visualization shows how the model attends to different parts of the image to form these slots, demonstrating the capacity of the model to extract semantically meaningful features from the input images.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visualization of spatial attention masks from the Object-Slots branch for two video examples, respectively. We have t = 8 frames as shown in 8 rows, indexed by i, where i = 1, ..., t. The first column shows the original frame. The second to the ninth columns show the cross attention mask (from slot attention) for the N° = 8 object-centric slots Oi = {0i,1,···, 0i,No}. We can see that even though not perfectly segmented, some meaningful slots have been formed. For example, the slots marked by red, purple, green, and blue in the first video (left) correspond to 'background', 'human body', 'head', and 'barbell'. Note that the slots in a frame is unordered and exchangeable.

🔼 This figure visualizes spatial attention masks from the Object-Slots branch at two different training stages: pre-training and instruction tuning. It shows how the attention mechanism changes after instruction tuning, resulting in more decoupled and semantically meaningful object-centric slot representations.

read the caption

Figure 8: Visualization of spatial attention masks from (a) the stage 1 pre-training, and (b) the stage 2 after instruction tuning. We have t = 8 frames as shown in 8 rows, indexed by i, where i = 1, ..., t, respectively. The first column shows the original frame. The second to the ninth columns show the cross attention mask (from slot attention) for the N° = 8 object-centric slots Oi = {0i,1,۰۰۰, Oi,No}. Interestingly, we can see that after the instruction tuning, the learned slots are much more decoupled, where a spatial position usually contributes to multiple slots in stage 1 but only contributes to a very few slots in stage 2.

🔼 This figure visualizes spatial attention masks from the Object-Slots branch, comparing stage 1 (pre-training) and stage 2 (after instruction tuning). It shows how instruction tuning leads to more decoupled slot representations, where each spatial position is less likely to contribute to multiple slots.

read the caption

Figure 9: Visualization of spatial attention masks from (a) the stage 1 pre-training, and (b) the stage 2 after instruction tuning. We have t = 8 frames as shown in 8 rows, indexed by i, where i = 1, ..., t, respectively. The first column shows the original frame. The second to the ninth columns show the cross attention mask (from slot attention) for the N° = 8 object-centric slots Oi = {0i,1,..., Oi,No}. Interestingly, we can see that after the instruction tuning, the learned slots are much more decoupled, where a spatial position usually contributes to multiple slots in stage 1 but only contributes to a very few slots in stage 2.

More on tables

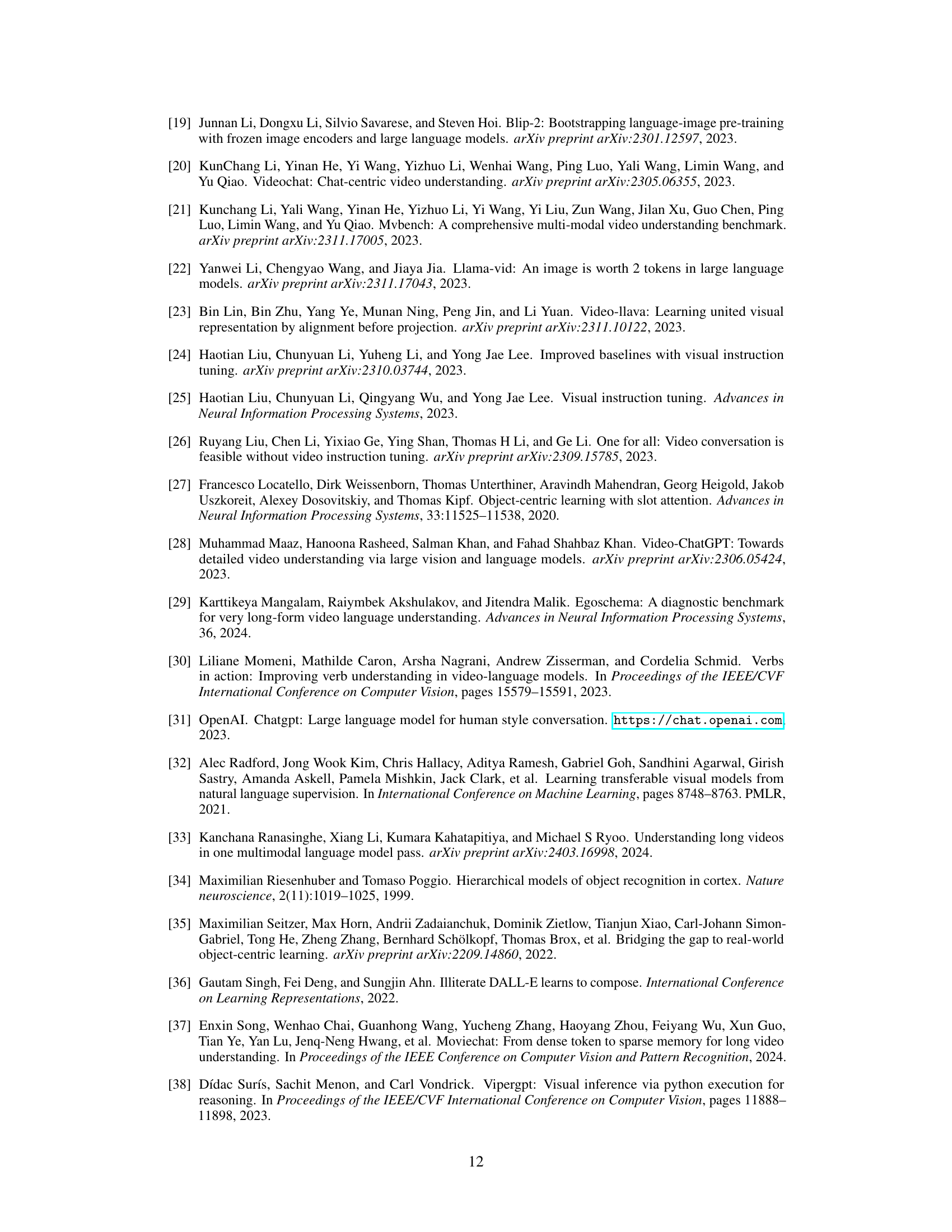

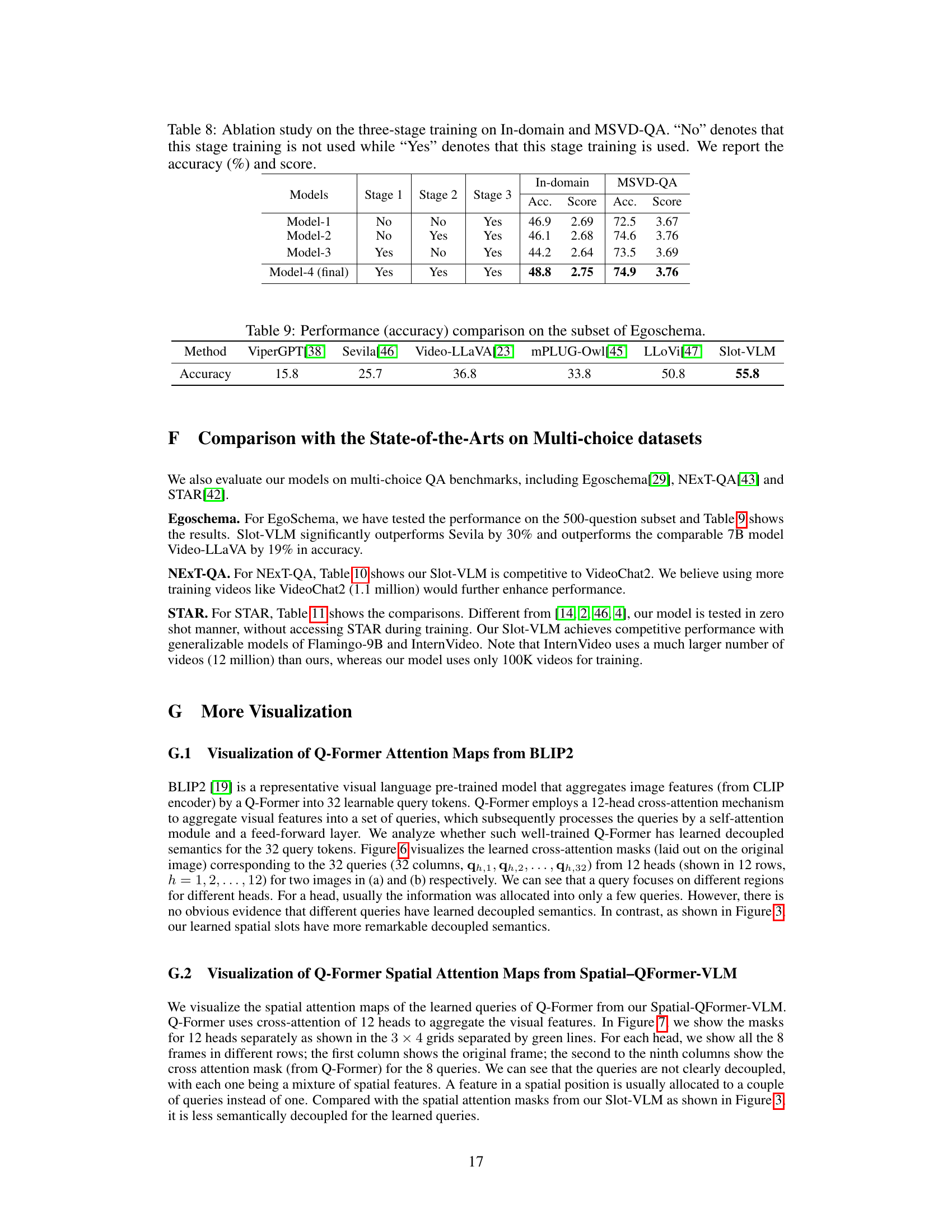

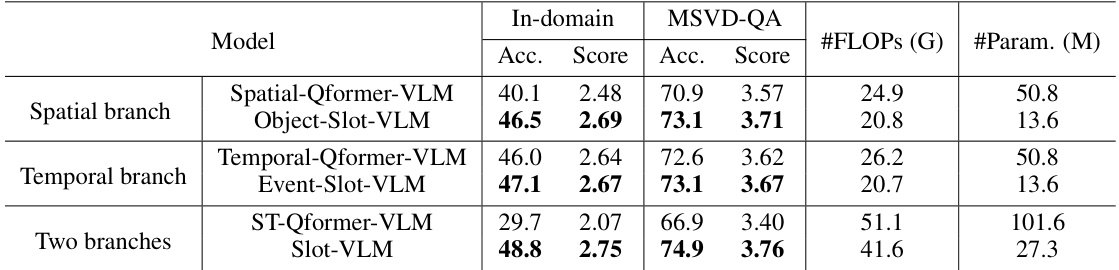

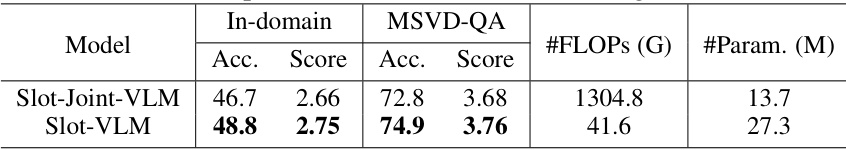

🔼 This table presents the ablation study comparing the effectiveness of Slot-VLM against other models using Q-Former. It shows the accuracy and score on two datasets (In-domain and MSVD-QA) for different model configurations: using only the spatial branch, only the temporal branch, and both branches, with each branch using either slot attention or Q-Former. The FLOPs (floating point operations) and the number of parameters are also provided for comparison.

read the caption

Table 2: Ablation studies on the effectiveness of our Slot-VLM. We compare our schemes powered by slot attention with the schemes powered by Q-Former under our framework. The FLOPs and number of parameters for the reduced token generation module are presented.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Slot-VLM with other state-of-the-art video question answering (QA) models. It shows the accuracy and average score achieved by each model on three benchmarks: MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, and ActivityNet-QA. The table also specifies the instruction data used for training each model, the method used to connect vision features and the LLM, and the number of video tokens used.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Slot-VLM against other state-of-the-art video question answering (QA) models. It highlights the different datasets and instruction tuning methods used by each model, along with their performance scores (accuracy and average score) across three QA benchmarks (MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, ActivityNet-QA). The table emphasizes that Slot-VLM achieves state-of-the-art results despite using significantly less instruction data than most comparable models.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of spatial resolution in the Object-Slots branch and frame rate in the Event-Slots branch of the proposed Slot-VLM model. It shows the performance (accuracy and average score) on the In-domain and MSVD-QA datasets when reducing either the spatial resolution or temporal sampling rate. This helps to understand the contribution of each branch to the overall model performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study on the influence of high spatial resolution for the Object-Slots branch and high frame rate for the Event-Slots branch. Object-Slot-VLM (4 × 4) denotes the spatial resolution is reduced from 16 × 16 to 4 × 4. Event-Slot-VLM (T/8) denotes the frame rate is reduced by a factor of 8.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Slot-VLM with other state-of-the-art video question answering (QA) models. It shows the accuracy and average scores on three benchmark datasets (MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, ActivityNet-QA). The table also indicates the LLM used (Vicuna-7B), the size and type of training data for each model, and the method used to connect vision features and the LLM. The performance of Slot-VLM is highlighted, showing its competitive results against other methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Slot-VLM against other state-of-the-art video question answering (QA) methods. Key aspects of the comparison include the LLM used (all use Vicuna-7B), the amount of pre-training and instruction-tuning data, the method used to connect vision features to the LLM, and the resulting accuracy scores across three benchmark datasets (MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, ActivityNet-QA). The table highlights Slot-VLM’s superior performance and efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Slot-VLM with other state-of-the-art video question answering (QA) models. It shows the accuracy and average score achieved by each model on three benchmarks: MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, and ActivityNet-QA. Key aspects compared include the instruction data used during training and the method used to connect vision features with the Language Model (LLM).

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Slot-VLM against other state-of-the-art video question answering (QA) models. It shows the accuracy and average score achieved by each model on three benchmark datasets (MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, ActivityNet-QA). The table also indicates the amount of training data used (both video and image instruction pairs) and the method employed to connect visual features with the Language Language Model (LLM).

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Slot-VLM with other state-of-the-art video question answering (VQA) models. It highlights the model’s accuracy on three benchmark datasets (MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, ActivityNet-QA), the type of LLM used (Vicuna-7B), the instruction data used for training, and the method used to connect vision features with the LLM. The table indicates that Slot-VLM achieves state-of-the-art performance, even with less instruction data compared to other models.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Slot-VLM against other state-of-the-art video question answering (QA) models. It highlights the different datasets used for pre-training and instruction tuning, the method used to connect vision features with the large language model (LLM), and the resulting accuracy scores on three benchmark datasets (MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, and ActivityNet-QA). The table shows that Slot-VLM achieves competitive or superior performance compared to other models.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Slot-VLM against other state-of-the-art video question answering (QA) models. It highlights the different datasets and instruction data used for training each model, along with the method used to connect visual features to the large language model (LLM). The table shows accuracy and average scores on three benchmark datasets: MSVD-QA, MSRVTT-QA, and ActivityNet-QA.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with the state-of-the-art methods for video QA. All these models use Vicuna-7B as the LLM. Different methods may use different datasets for pre-training. Moreover, for the instruction tuning, different methods adopt different instruction data as illustrated in the second column. For example, 11K(V)+5.1M(I) denotes the instruction data comprises about 11,000 pairs of video instructions pairs and 5.1 million pairs of image instructions. Connector denotes the method for connecting the vision features and the LLM. See Table 4 for the number of video tokens.

Full paper#