TL;DR#

Current video captioning models struggle with understanding complex scenes and providing concise, context-aware descriptions. They tend to focus on superficial details, leading to overly verbose outputs and lacking the nuanced understanding that humans possess. This is particularly problematic when dealing with movies and videos, where a deeper contextual understanding is crucial for providing comprehensive and meaningful descriptions.

CALVIN tackles this challenge using a specialized video LLM. It is trained on a suite of tasks that integrate both image-based question-answering and video captioning, followed by instruction tuning to improve its ability to generate contextual captions. The model shows remarkable performance improvements, surpassing previous state-of-the-art methods, and demonstrating the effectiveness of prompt engineering and few-shot learning for adapting to new movie contexts with minimal additional annotation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in video captioning and vision-language modeling. It introduces CALVIN, a novel model that significantly improves contextual video captioning, surpassing existing state-of-the-art methods. Its few-shot learning capabilities and use of instruction tuning offer valuable insights into enhancing video LLMs. This work also opens exciting new avenues for research in context-aware video understanding, especially for applications such as automated audio description generation for visually impaired individuals.

Visual Insights#

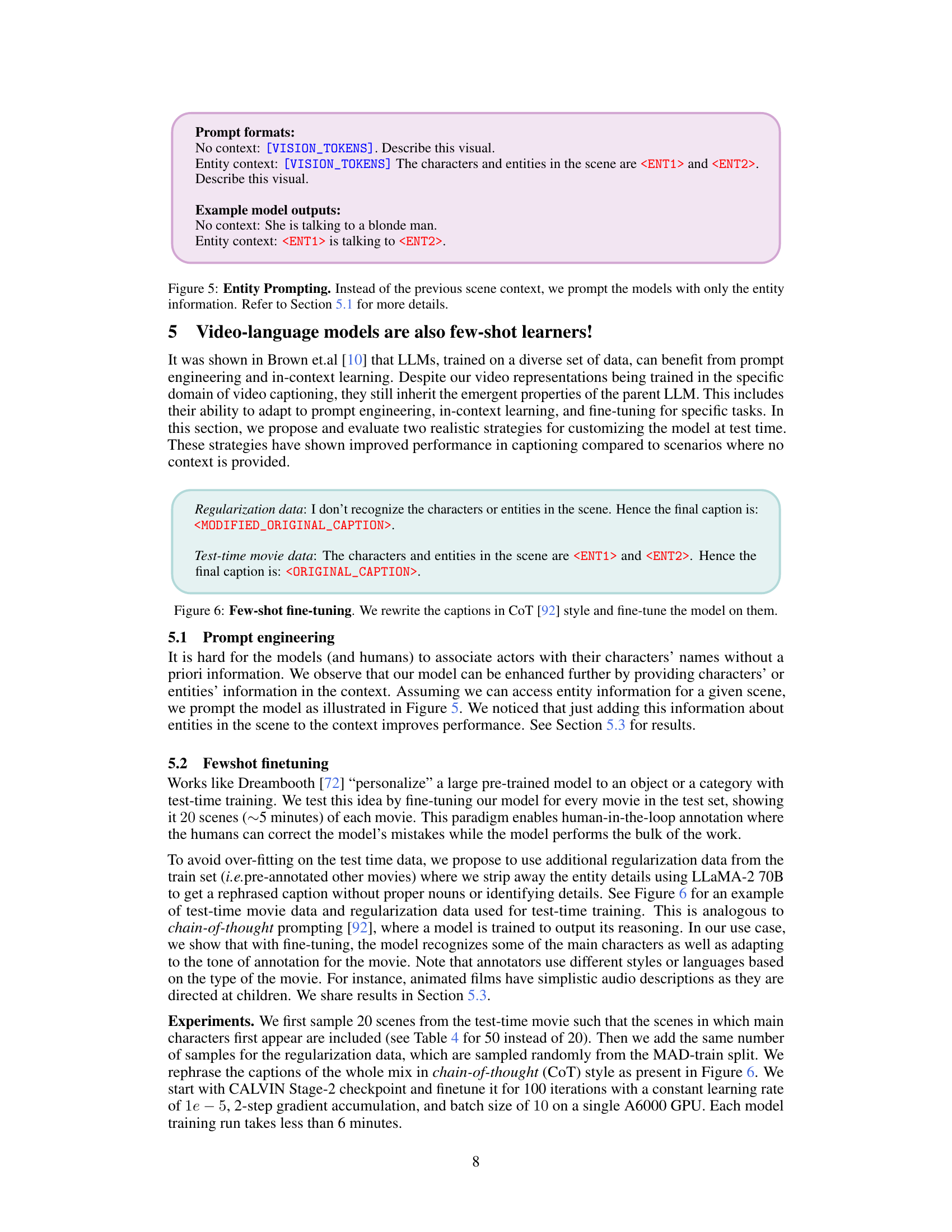

🔼 The figure shows the architecture of CALVIN, a contextual video captioning model. It consists of three main components: a frozen image embedding extractor, a non-linear projection module, and a large language model (LLM). The model is trained in two stages. In Stage 1, only the projection module is trained on image caption data. In Stage 2, higher-quality image-video data is used, and the parameters of both the projection module and the LLM are fine-tuned. Synthetic images and videos are used for illustrative purposes.

read the caption

Figure 2: CALVIN: The architecture has 3 main components. (1) A frozen image embedding extractor I, (2) Non-linear projection module Q, and (3) An LLM. We train the model in 2 stages. Stage 1, we train only the projection module Q on image caption data. Stage 2, we use instruction formatted higher quality image-video data and finetune the parameters of Q and LLM. Refer to Sec. 3 for more details. Image and video examples shown here are synthetically generated using Meta Imagine [1].

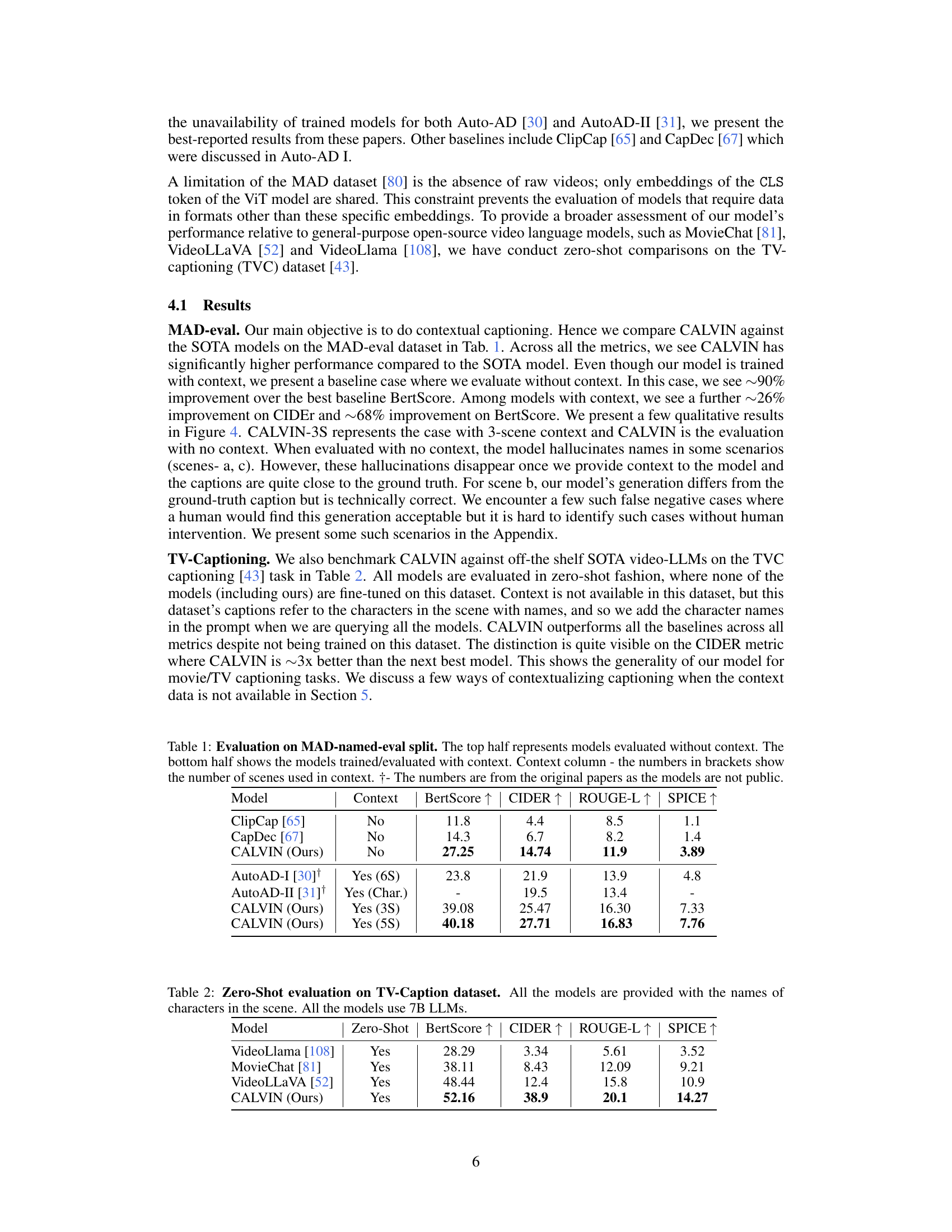

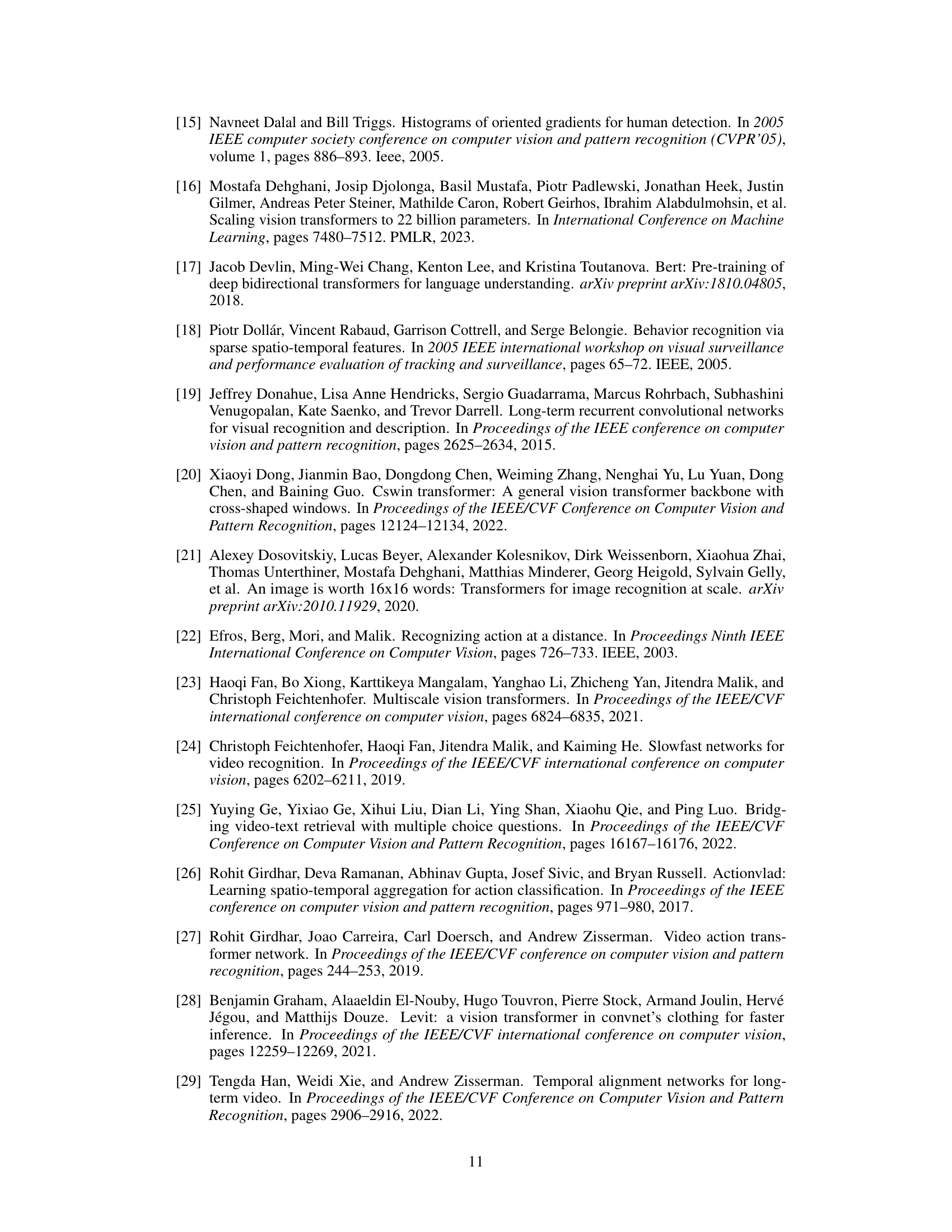

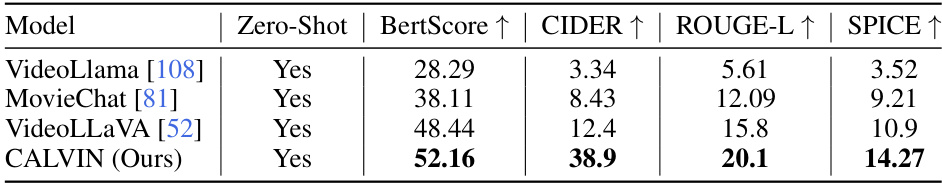

🔼 This table presents the zero-shot evaluation results on the TV-Caption dataset for several video-LLMs, including CALVIN. The models were not fine-tuned on this dataset; instead, character names were added to the prompts to provide context. The table compares the performance of different models across four metrics: BertScore, CIDEr, ROUGE-L, and SPICE, all of which are commonly used to evaluate the quality of video captions. The inclusion of character names in prompts aims to evaluate the models’ ability to generate captions that incorporate contextual information.

read the caption

Table 2: Zero-Shot evaluation on TV-Caption dataset. All the models are provided with the names of the characters in the scene. All the models use 7B LLMs.

In-depth insights#

Contextual Captioning#

Contextual captioning, as explored in the research paper, presents a significant advancement in video understanding. The core idea is to move beyond simple, object-centric descriptions and generate captions that incorporate a deeper understanding of the scene’s context, mirroring human comprehension. This involves leveraging prior events, character interactions, and narrative elements to produce more informative and engaging captions. The success of contextual captioning relies on powerful vision-language models (VLMs) trained on diverse data encompassing both image and video information, incorporating question-answering tasks to refine the model’s understanding. Prompt engineering and few-shot learning techniques further enhance the model’s adaptability, allowing it to be easily adapted to new movies with minimal additional annotation. This approach addresses the limitations of previous models that generated overly verbose descriptions or focused on superficial features, leading to more human-like and contextually rich output, thus improving accessibility for visually impaired individuals.

Instruction Tuning#

Instruction tuning, a crucial technique in the paper, refines the model’s ability to generate contextually relevant captions by training it on a set of tasks integrating image-based question-answering and video captioning. This approach moves beyond simple image captioning to encompass a deeper understanding of movie scenes, enabling the generation of more comprehensive and coherent scene descriptions. The model learns to leverage prior context effectively, thereby addressing the limitations of models that treat videos as sequences of isolated images. This method is particularly beneficial for generating audio descriptions (ADs), which require a more nuanced and contextual understanding than general-purpose video captioning. The instruction tuning stage is essential for CALVIN’s ability to provide human-like, concise, and contextually relevant descriptions, surpassing the performance of off-the-shelf LLMs.

Video-LLM#

Video LLMs represent a significant advancement in video understanding, integrating the power of large language models (LLMs) with visual data. Their key strength lies in contextual understanding, surpassing the limitations of previous methods that treated videos as sequences of independent images. This enables richer, more coherent descriptions, particularly valuable for complex scenes like those in movies. However, challenges remain. Training effective Video LLMs requires substantial data, and even then, handling long videos and generating truly contextual captions remains difficult. Prompt engineering and few-shot learning techniques offer promising avenues for adapting these models to new contexts with limited annotation. Future research should focus on addressing the data scarcity issue, improving efficiency for long-form videos, and further exploring the potential of integrating multimodal data beyond image and text to achieve more robust and nuanced video comprehension.

Few-Shot Learning#

Few-shot learning, a subfield of machine learning, addresses the challenge of training accurate models with limited data. This is particularly relevant in scenarios with high annotation costs or data scarcity, such as medical imaging or rare language identification. The core idea is to leverage prior knowledge, often from a larger dataset of related tasks, to enable the model to generalize effectively even with a small number of examples for a new task. This is achieved through various techniques, including meta-learning algorithms that learn to learn, transfer learning methods that adapt knowledge from a source task to a target task, and data augmentation strategies that artificially increase the size of the dataset. A key advantage of few-shot learning is its ability to reduce the need for extensive data annotation, which can significantly accelerate model development. However, challenges remain in ensuring that the model generalizes well to unseen data and that the learned knowledge effectively transfers to new tasks. This is an active area of research with ongoing progress in algorithm design, dataset creation, and application to various fields.

Future Directions#

The future of contextual video captioning hinges on addressing several key challenges. Improving the handling of long-form videos is crucial, as current models struggle with maintaining context across extended durations. This requires advancements in efficient memory mechanisms and potentially exploring alternative architectures beyond traditional transformers. Data scarcity remains a significant bottleneck, particularly for high-quality, contextually rich datasets. Efforts should focus on creating larger, more diverse datasets, potentially leveraging techniques like synthetic data generation or data augmentation. Addressing the issue of hallucination in generated captions is paramount. This might involve incorporating stronger grounding mechanisms, leveraging external knowledge sources, or developing more robust evaluation metrics that specifically penalize factually incorrect statements. Finally, exploring new modalities beyond visual and textual information, such as incorporating audio cues or incorporating user feedback, could drastically improve the accuracy and comprehensiveness of contextual video descriptions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of CALVIN, a contextual video captioning model. It’s a two-stage training process. Stage 1 trains only the projection module (Q) using image caption data; Stage 2 fine-tunes both the projection module and the Language Model (LLM) using higher-quality image and video data formatted as instructions. The model uses three core components: a frozen image embedding extractor, a non-linear projection module, and an LLM.

read the caption

Figure 2: CALVIN: The architecture has 3 main components. (1) A frozen image embedding extractor I, (2) Non-linear projection module Q, and (3) An LLM. We train the model in 2 stages. Stage 1, we train only the projection module Q on image caption data. Stage 2, we use instruction formatted higher quality image-video data and finetune the parameters of Q and LLM. Refer to Sec. 3 for more details. Image and video examples shown here are synthetically generated using Meta Imagine [1].

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of CALVIN, a contextual video captioning model. It consists of three main components: a frozen image embedding extractor, a non-linear projection module, and a language model (LLM). The model is trained in two stages. Stage 1 trains only the projection module using image caption data. Stage 2 fine-tunes both the projection module and the LLM using higher-quality image and video data formatted as instructions. The example images and videos in the diagram are synthetically generated.

read the caption

Figure 2: CALVIN: The architecture has 3 main components. (1) A frozen image embedding extractor I, (2) Non-linear projection module Q, and (3) An LLM. We train the model in 2 stages. Stage 1, we train only the projection module Q on image caption data. Stage 2, we use instruction formatted higher quality image-video data and finetune the parameters of Q and LLM. Refer to Sec. 3 for more details. Image and video examples shown here are synthetically generated using Meta Imagine [1].

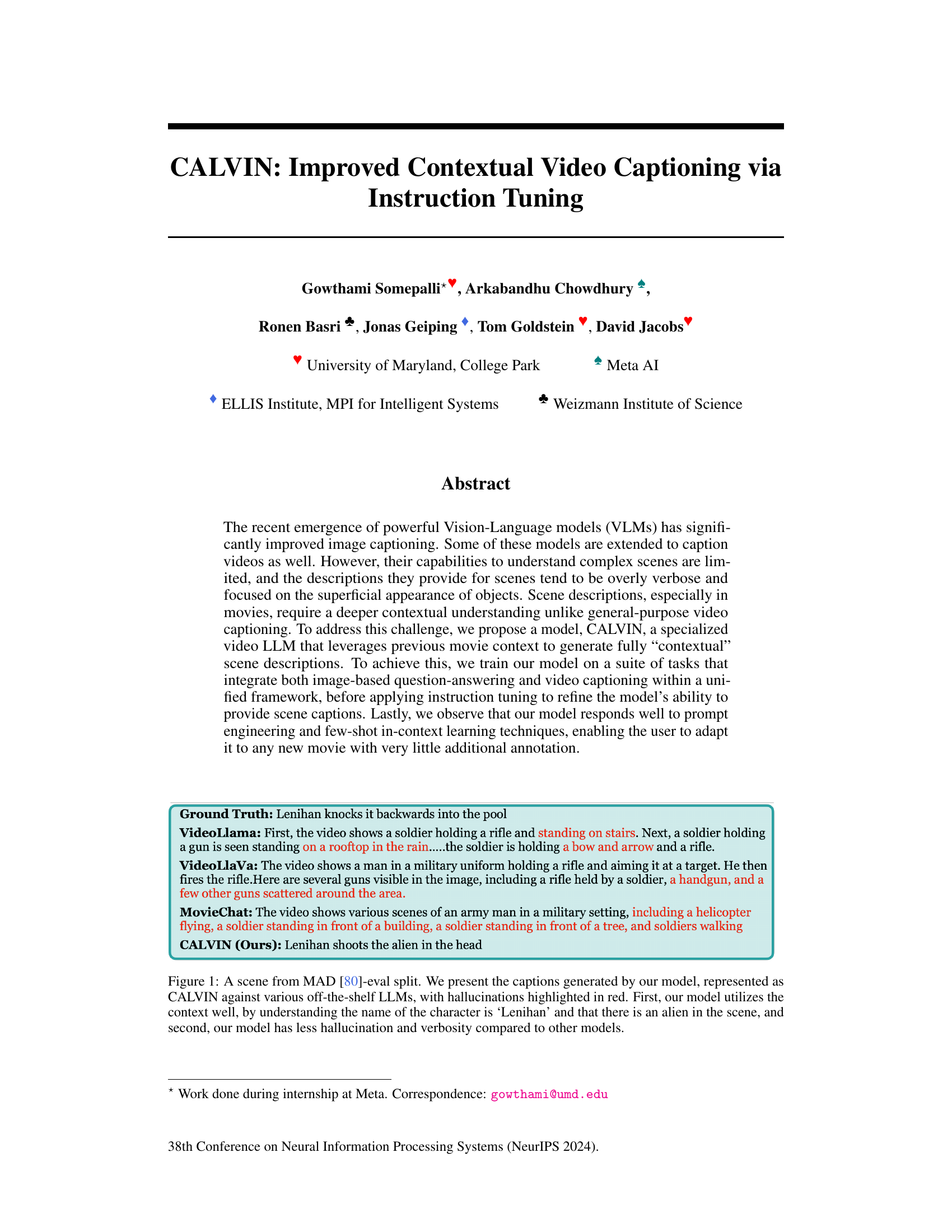

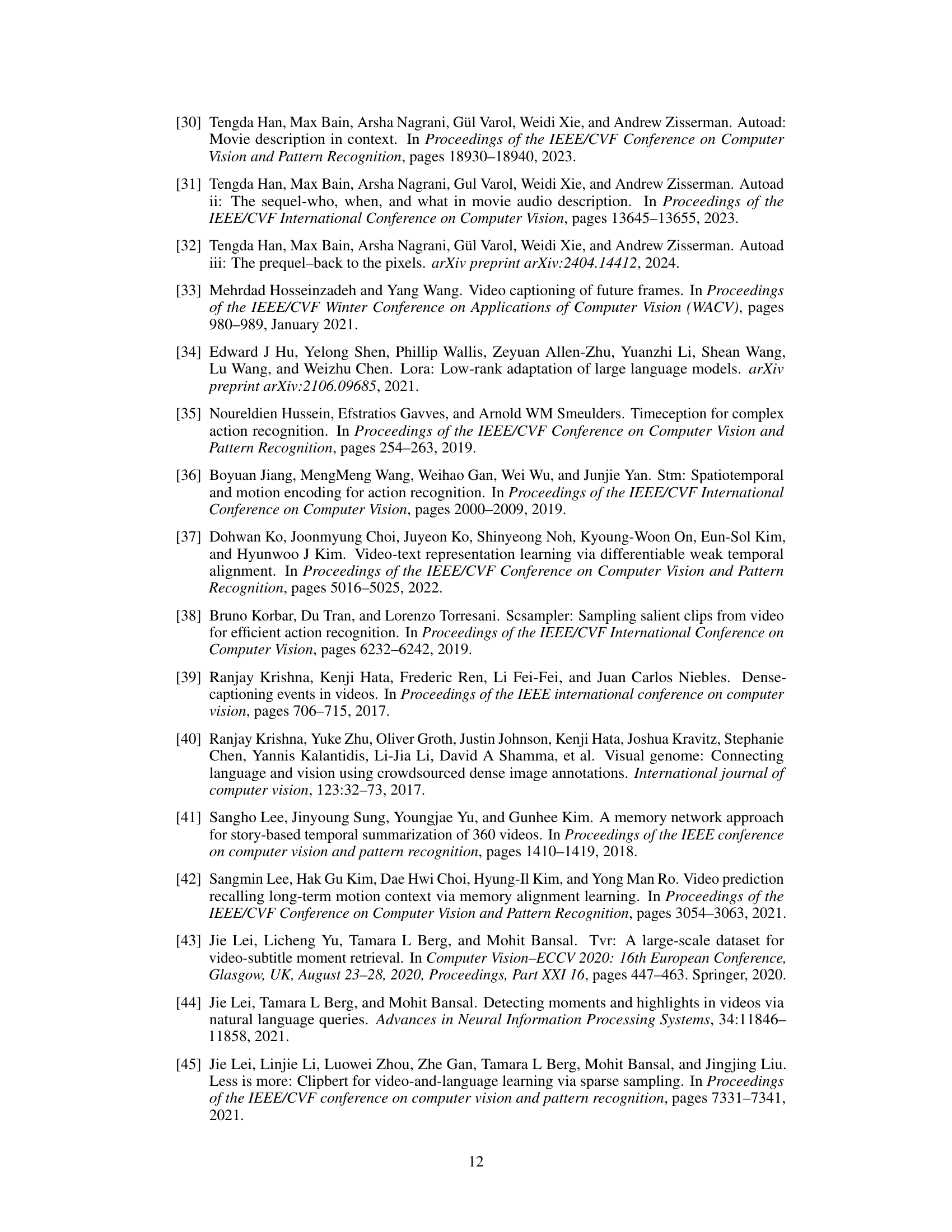

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of video captions generated by the proposed model, CALVIN, and several other existing models for a scene from the MAD dataset. The figure highlights how CALVIN leverages contextual information (the name of a character and the presence of an alien) to produce a more accurate and concise caption, compared to the other models which either hallucinate details or produce overly verbose descriptions.

read the caption

Figure 1: A scene from MAD [80]-eval split. We present the captions generated by our model, represented as CALVIN against various off-the-shelf LLMs, with hallucinations highlighted in red. First, our model utilizes the context well, by understanding the name of the character is 'Lenihan' and that there is an alien in the scene, and second, our model has less hallucination and verbosity compared to other models.

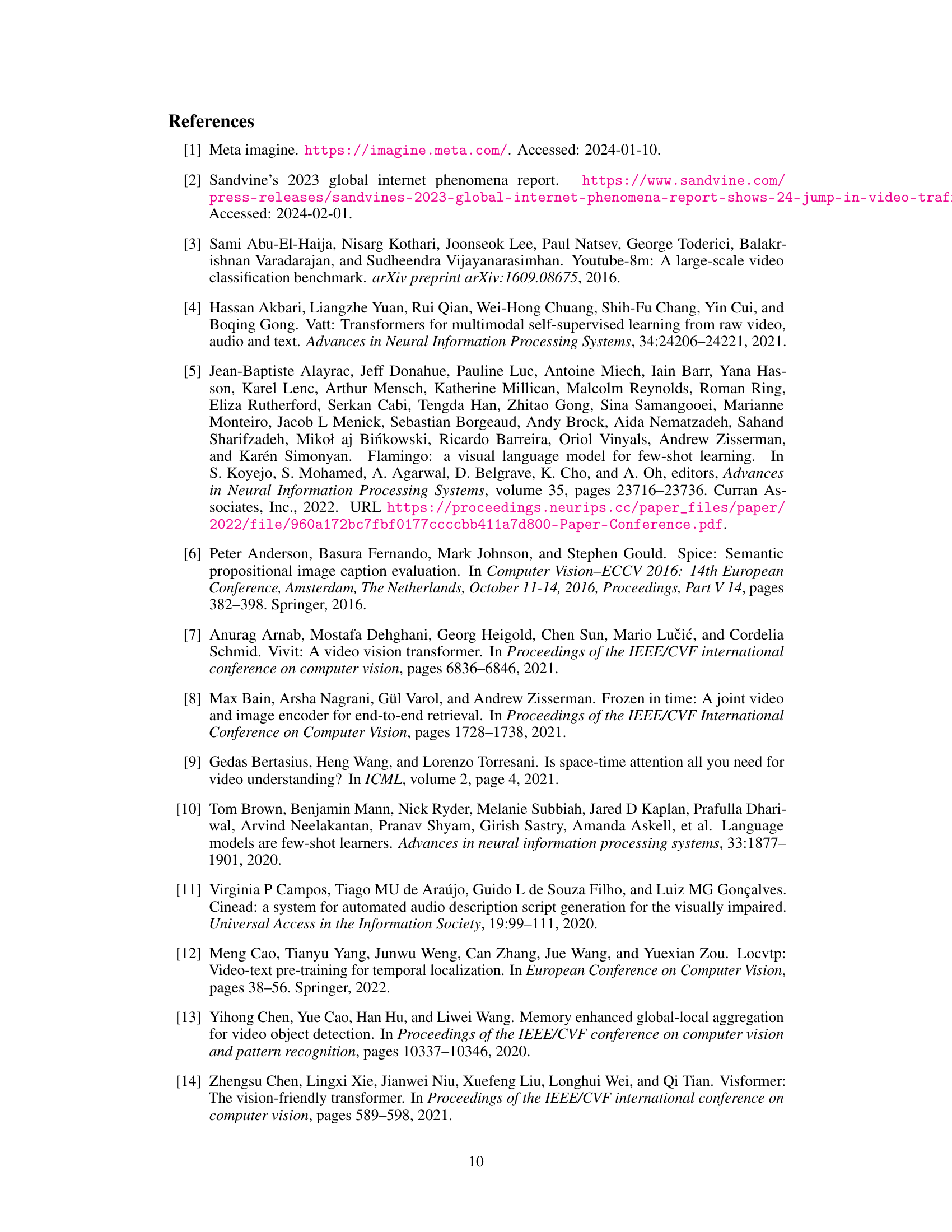

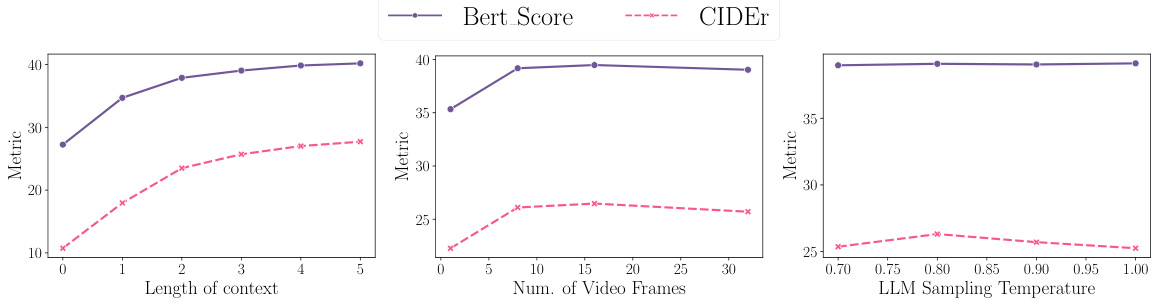

🔼 This figure shows how different metrics (BertScore, CIDEr, ROUGE-L, and SPICE) for video captioning performance change with varying numbers of ground truth samples used in few-shot fine-tuning. It demonstrates that increasing the number of training samples improves these metrics, but the gains diminish beyond around 50 samples. This suggests a point of diminishing returns in using more than a certain amount of samples for this specific adaptation task.

read the caption

Figure 10: Number of ground-truth samples vs Metrics.

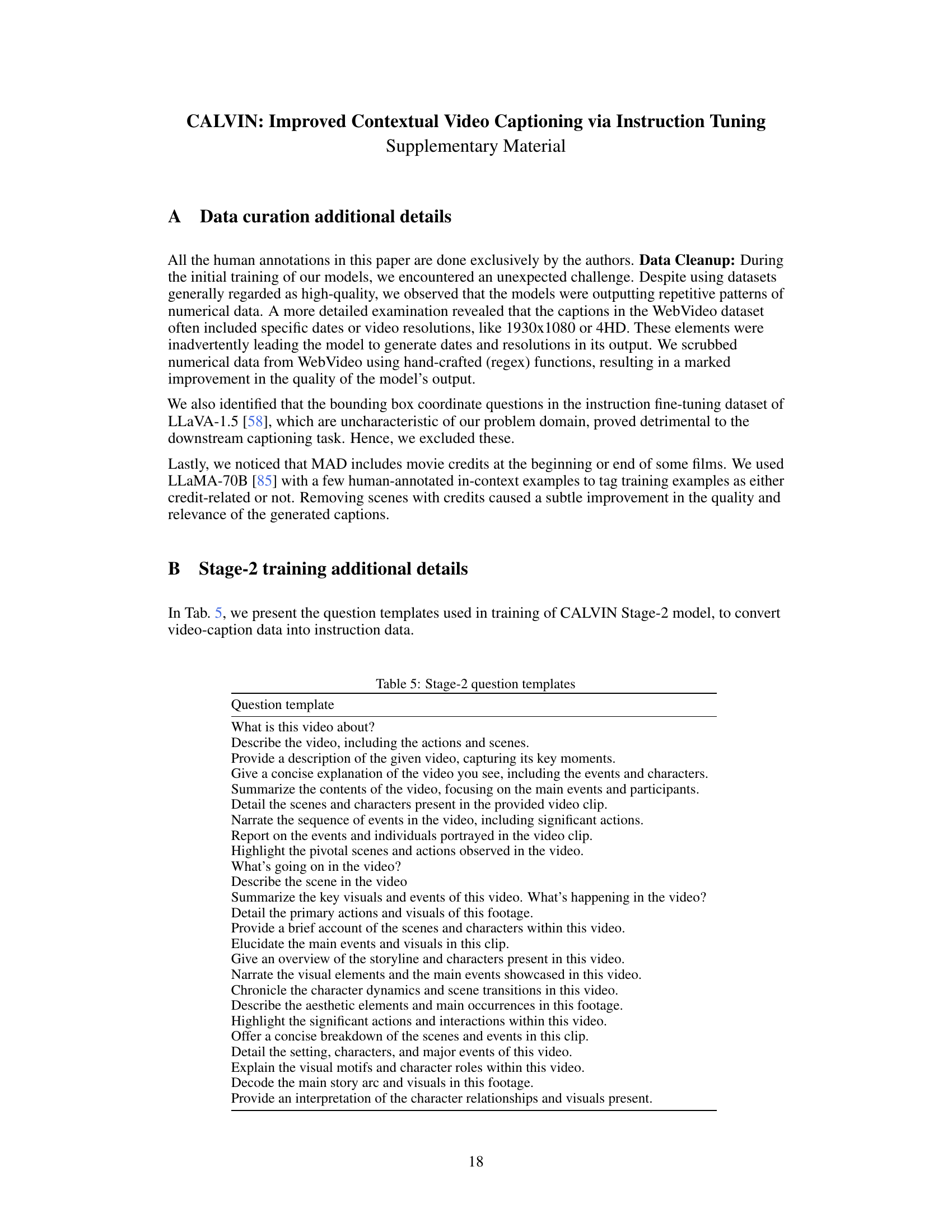

More on tables

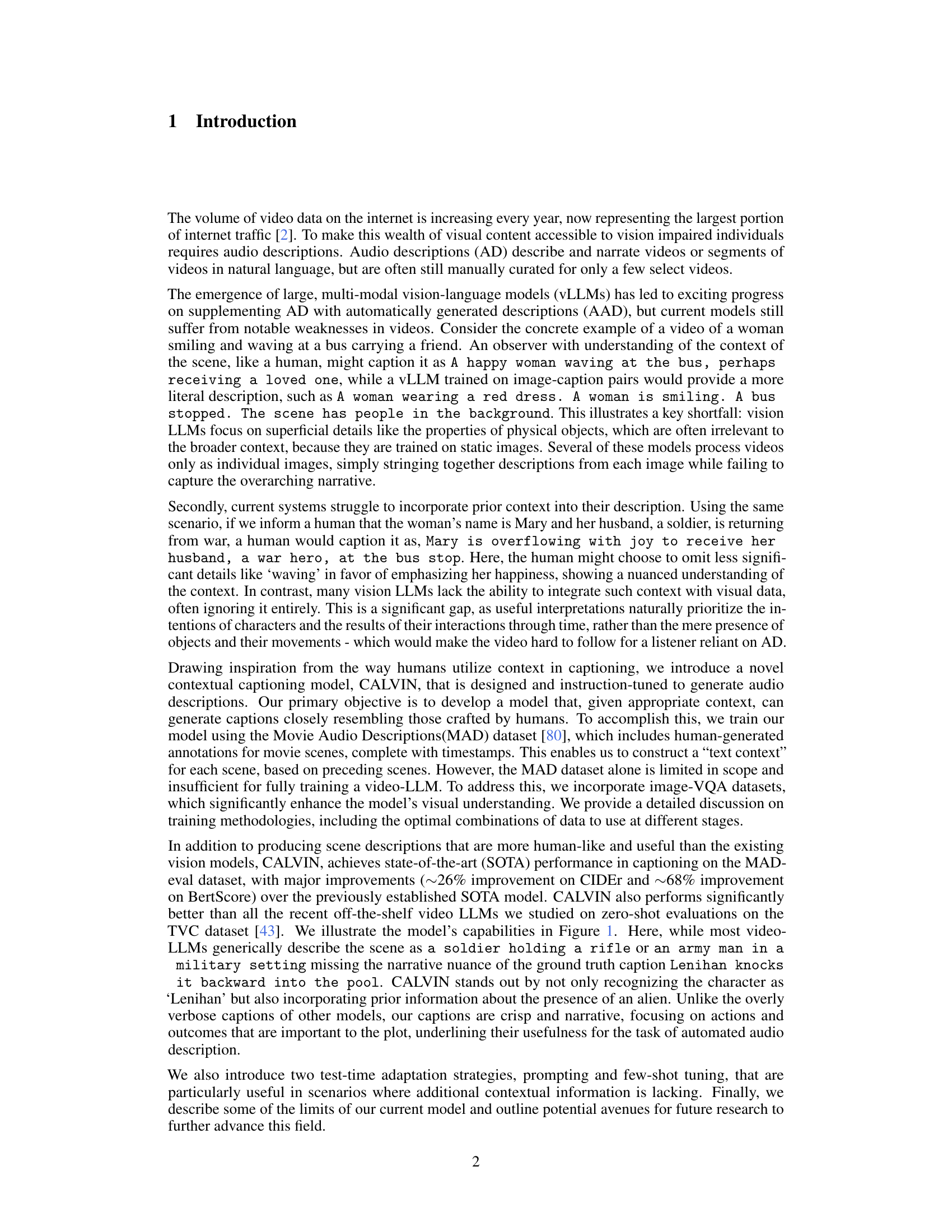

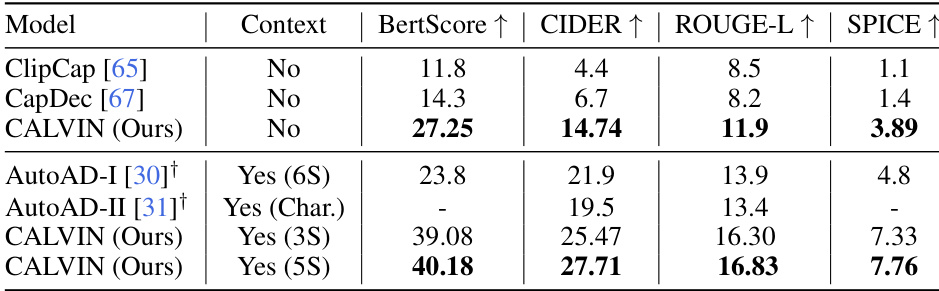

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different models on the MAD-named-eval dataset for contextual video captioning. The models are evaluated with and without context. The metrics used for evaluation are BertScore, CIDER, ROUGE-L, and SPICE. The table highlights the significant improvement achieved by CALVIN, particularly when using contextual information. Note that some SOTA results are taken from other papers, indicated by †.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation on MAD-named-eval split. The top half represents models evaluated without context. The bottom half shows the models trained/evaluated with context. Context column - the numbers in brackets show the number of scenes used in context. †- The numbers are from the original papers as the models are not public.

🔼 This table presents a zero-shot evaluation of various video-LLMs on the TV-Caption dataset. Zero-shot means the models weren’t fine-tuned on this dataset; they were evaluated using only their pre-trained weights. The models were all 7B LLMs (large language models). The results show the performance of each model on four metrics: BertScore, CIDER, ROUGE-L, and SPICE, which measure different aspects of caption quality. Note that the character names were provided as context to all models.

read the caption

Table 2: Zero-Shot evaluation on TV-Caption dataset. All the models are provided with the names of the characters in the scene. All the models use 7B LLMs.

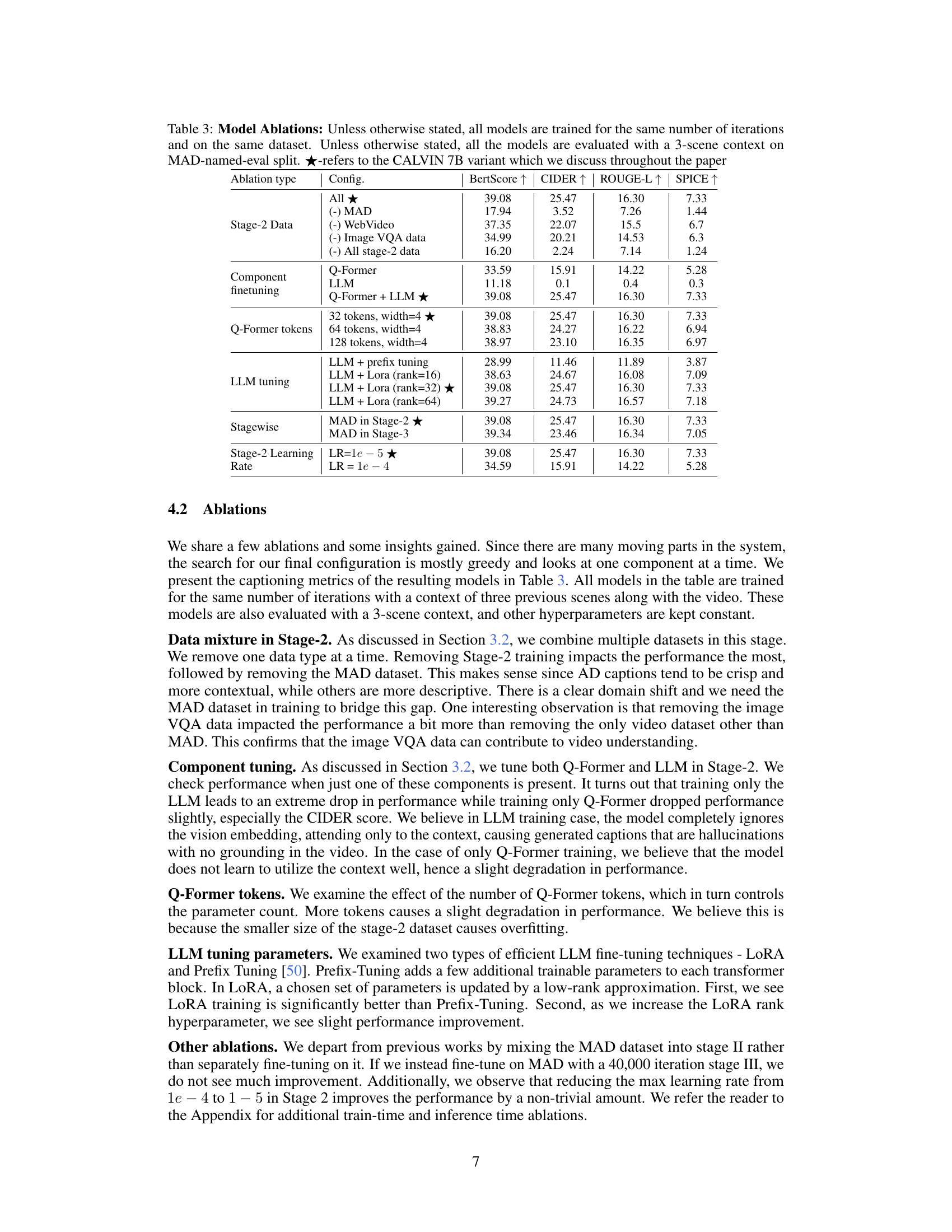

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies performed on the CALVIN model. The ablation studies systematically remove or modify different components or training parameters to assess their impact on the model’s performance. The table shows the effect on four key metrics (BertScore, CIDER, ROUGE-L, and SPICE) by varying training data (removing MAD, WebVideo, image VQA data, or all stage-2 data), finetuning components (Q-Former, LLM, or both), adjusting hyperparameters (number of Q-Former tokens and LLM tuning methods), and changing the training strategy (placing MAD in Stage 2 or 3, or adjusting learning rate). The star symbol (★) indicates the configuration of CALVIN 7B used as the baseline for comparison.

read the caption

Table 3: Model Ablations: Unless otherwise stated, all models are trained for the same number of iterations and on the same dataset. Unless otherwise stated, all the models are evaluated with a 3-scene context on MAD-named-eval split. ★-refers to the CALVIN 7B variant which we discuss throughout the paper

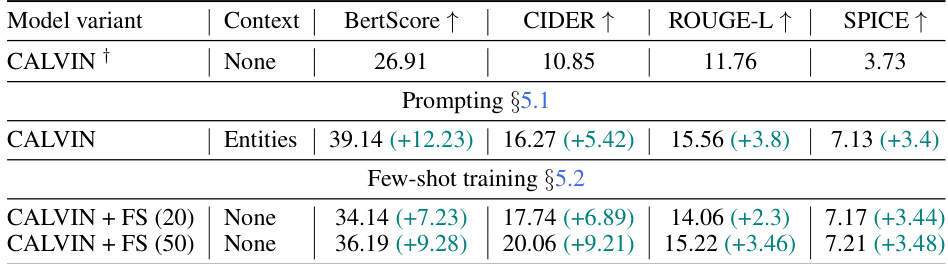

🔼 This table presents the results of different test-time adaptation strategies for the CALVIN model on the MAD-eval dataset. It compares the performance of CALVIN without any context, with only entity information in the prompt, and with few-shot finetuning on 20 or 50 samples from each movie. The results are shown for BertScore, CIDEr, ROUGE-L, and SPICE metrics. The numbers in parentheses indicate the improvement over the baseline model without context. Note that slight discrepancies from Table 1 may exist due to averaging metrics calculated per movie, affecting metrics like CIDEr based on word distribution.

read the caption

Table 4: Test-time adaptation results: (first row) CALVIN evaluation without context. (second row) 'Entities' means the context has just the list of entities in the scene as discussed in Sec. 5.1. (third and fourth rows) For few-shot training from Sec. 5.2, the number in brackets counts examples used in finetuning. Both strategies improve performance over the no-context.(† Numbers differ slightly from Tab. 1 since the numbers presented here are an average of metrics computed one movie at a time, and some metrics like CIDEr depend on the word distribution of evaluation set.)

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating different models on the MAD-named-eval dataset, which is a subset of the Movie Audio Descriptions dataset that includes character names in the captions. The top half shows the performance of models evaluated without using any context from previous scenes. The bottom half shows the results for models trained and/or evaluated using context from previous scenes (the number of scenes used as context is shown in brackets). The table compares different metrics, including BertScore, CIDEr, ROUGE-L, and SPICE, to assess the quality of the generated captions. The † symbol indicates that the numbers for some models were taken from the original papers, as the model implementations are not publicly available.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation on MAD-named-eval split. The top half represents models evaluated without context. The bottom half shows the models trained/evaluated with context. Context column - the numbers in brackets show the number of scenes used in context. †- The numbers are from the original papers as the models are not public.

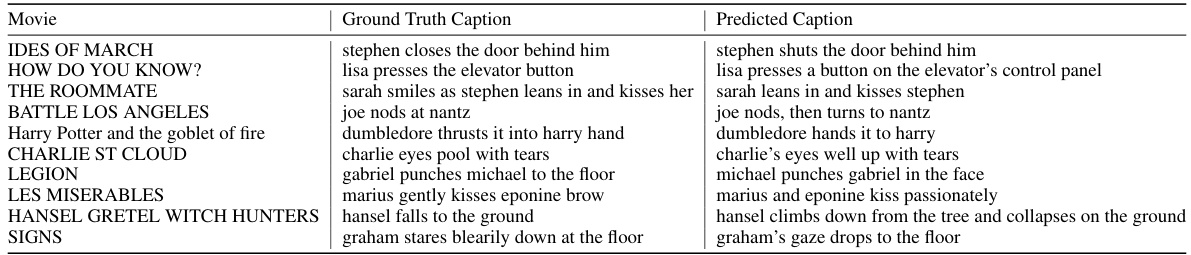

🔼 This table provides a qualitative comparison of the ground truth captions and the captions generated by the CALVIN-3S model for a subset of movies from the MAD-eval dataset. Each row represents a movie, showing the original caption written by a human and the corresponding prediction from the model. The purpose is to illustrate the model’s ability to generate captions that are similar in meaning and style to the original captions.

read the caption

Table 6: Ground truth vs Predicted captions on CALVIN-3S model: We present an example from each movie in the MAD-eval dataset.

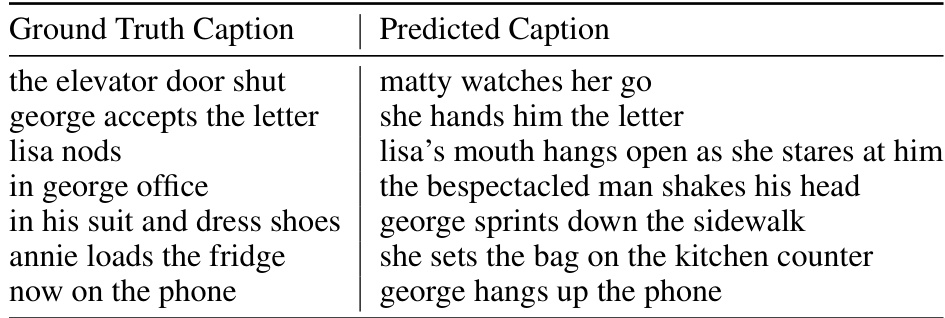

🔼 This table shows a qualitative comparison of ground truth captions and captions generated by the CALVIN-3S model. The authors selected examples where the generated captions, while differing from the ground truth, were still considered acceptable interpretations of the scene. All examples are from the ‘How Do You Know?’ movie in the MAD-eval dataset.

read the caption

Table 7: Human acceptable predictions: Some ground truth captions vs CALVIN-3S generated captions which the authors felt are acceptable despite being different from the GT. All the examples are from the MAD-eval movie, How do you know?

Full paper#