TL;DR#

Current methods for evaluating causal reasoning in Large Language Models (LLMs) either lack real-world grounding or are too abstract. This limits our understanding of how well LLMs truly grasp causal relationships and their ability to apply that understanding to real-world situations. Existing benchmarks are either too simple or rely on symbolic reasoning that isn’t grounded in everyday human experience.

The researchers introduce the COLD (Causal reasOning in cLosed Daily activities) framework to address these limitations. COLD uses scripts describing common daily activities to generate a massive set of causal queries (~9 million). By testing LLMs on this dataset, the researchers found that causal reasoning is more challenging than previously thought, even for tasks that are trivial to humans. This highlights the need for more sophisticated approaches to building LLMs with stronger causal reasoning capabilities.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical need for evaluating large language models’ (LLMs) causal reasoning abilities, a crucial aspect of general intelligence. The COLD framework offers a rigorous and scalable approach to testing LLMs on real-world causal understanding, moving beyond simplistic benchmarks. This methodology helps researchers better understand LLM capabilities and limitations, paving the way for more advanced causal reasoning models.

Visual Insights#

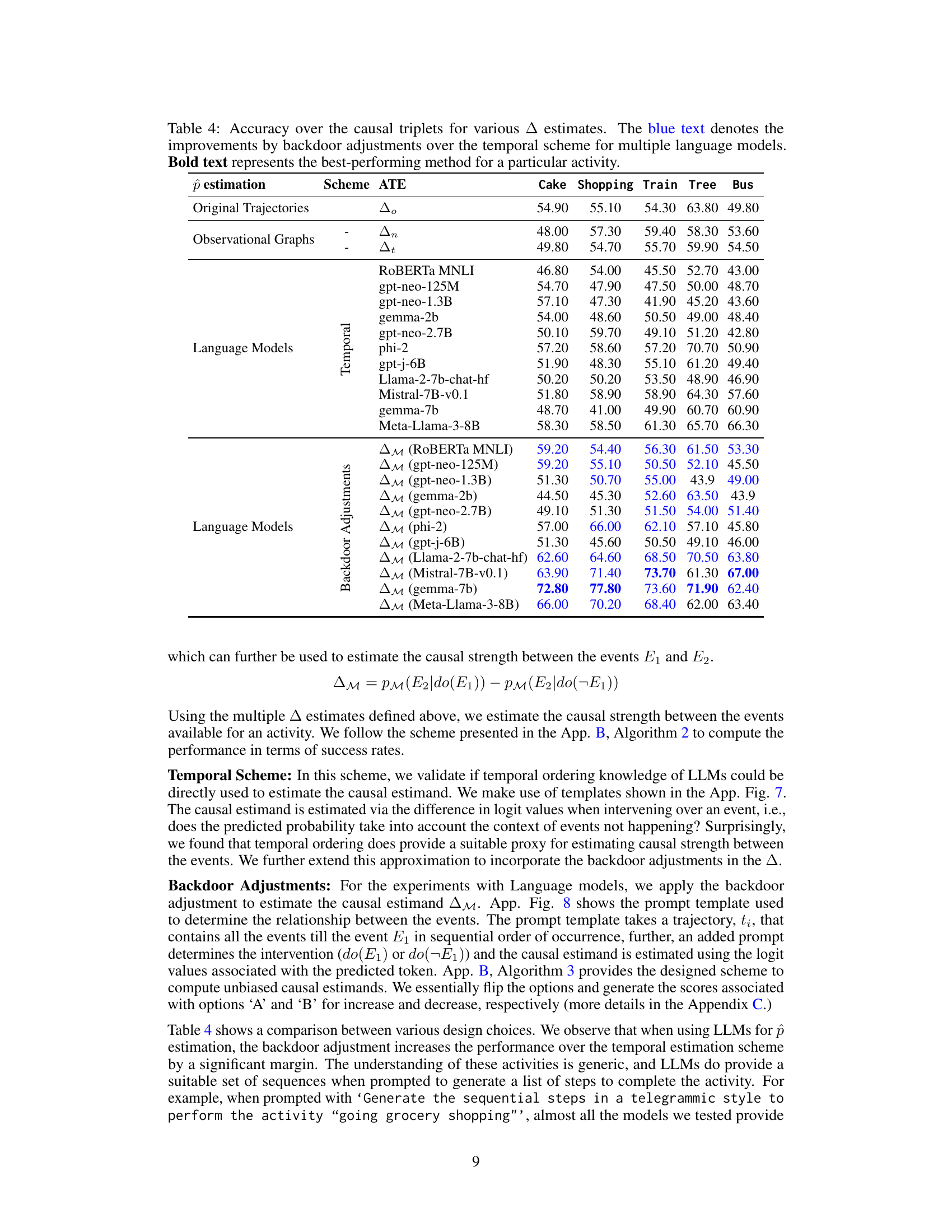

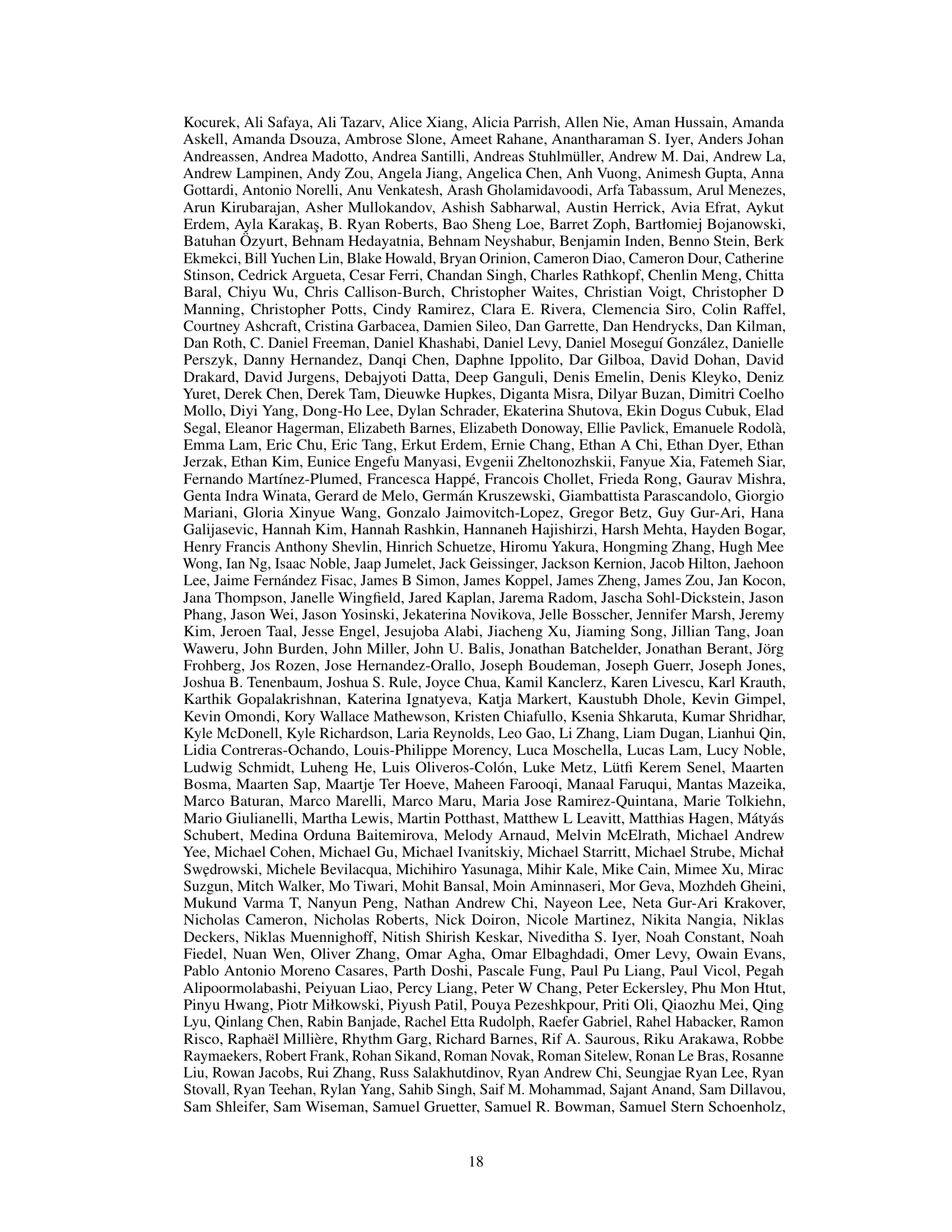

🔼 This figure illustrates the causal relationships between events in the activity of ’traveling by airplane.’ The unobserved variable U represents confounding factors affecting all events. Arrows show the causal relationships between events, indicating which events cause others to occur. Some events (like ‘finding the boarding gate’) have no causal relationship with others. This highlights the complexities of causal reasoning, even within seemingly simple everyday activities.

read the caption

Figure 1: U denotes the unobserved variables, confounding all events present in a real-world activity. In an activity, some events cause other events to happen. For example, in “traveling by an airplane”, the event of “check-in luggage” causes events like “taking back luggage.”

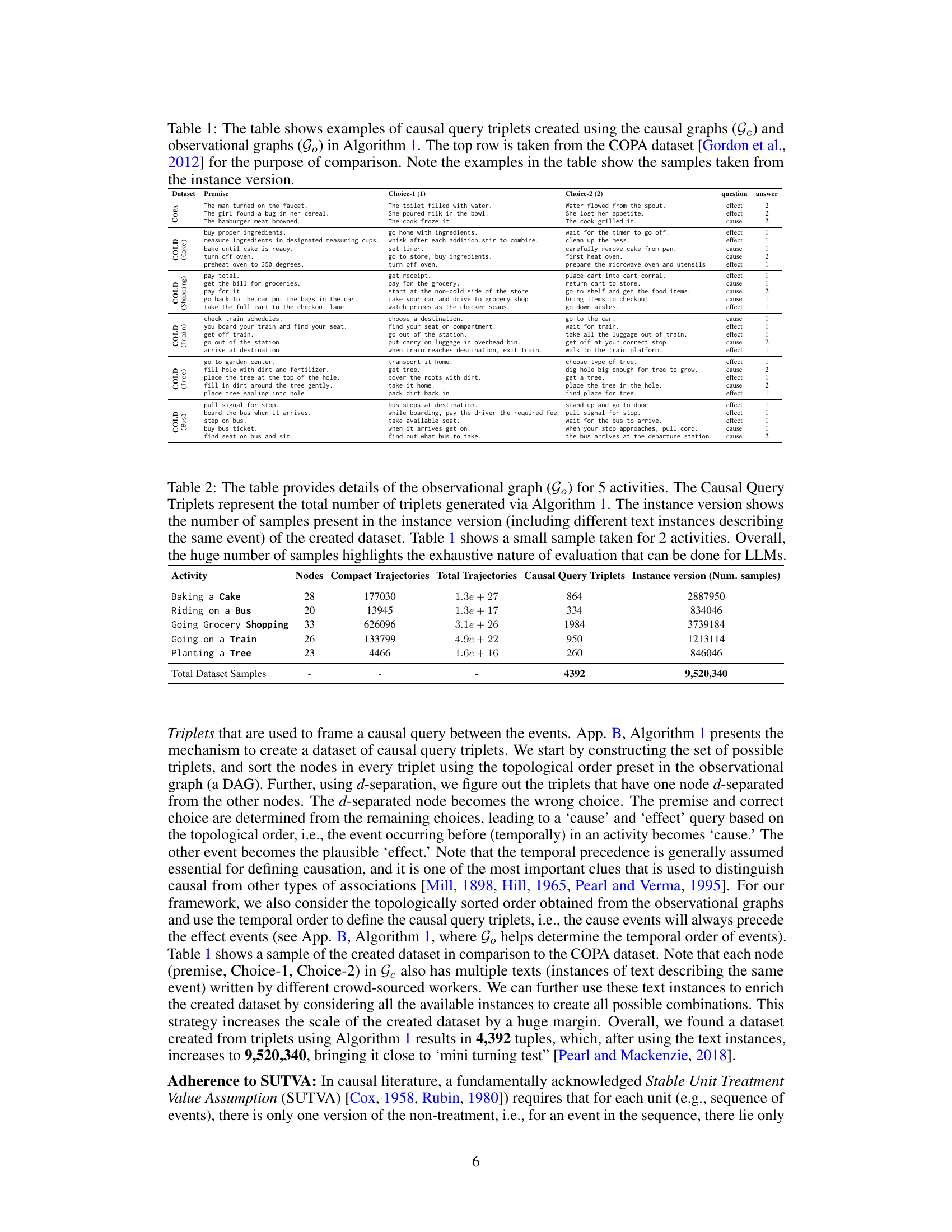

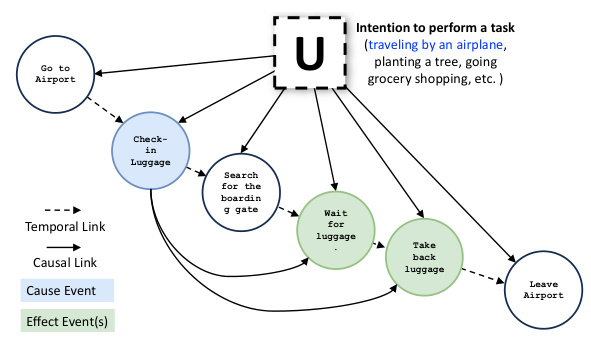

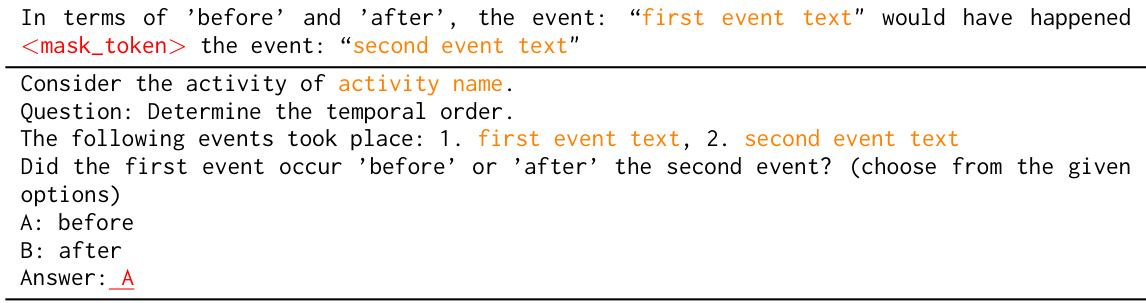

🔼 This table presents examples of causal query triplets generated using the COLD framework. Each triplet consists of a premise (an event), two choices (potential causes or effects), a question (identifying the cause or effect), and the correct answer. The first row shows a comparison example from the COPA dataset, highlighting the similar structure used in COLD for generating causal triplets. The table also indicates that examples provided are from the ‘instance version’ of the dataset, suggesting that multiple text descriptions might exist for the same event.

read the caption

Table 1: The table shows examples of causal query triplets created using the causal graphs (Ge) and observational graphs (Go) in Algorithm 1. The top row is taken from the COPA dataset [Gordon et al., 2012] for the purpose of comparison. Note the examples in the table show the samples taken from the instance version.

In-depth insights#

Causal Reasoning#

Causal reasoning, the ability to understand cause-and-effect relationships, is a crucial aspect of human intelligence and a significant challenge in artificial intelligence. The paper delves into this, exploring how large language models (LLMs) fare in causal reasoning tasks. A key limitation of current LLM approaches is their tendency to memorize patterns instead of genuinely understanding causal mechanisms. The paper proposes a novel framework, COLD, which focuses on causal reasoning in closed, everyday activities, leveraging script knowledge to create a more controlled and realistic evaluation setting. This approach helps mitigate the issue of spurious correlations and allows for a more nuanced assessment of LLM causal reasoning capabilities. The framework introduces a new benchmark dataset of causal queries, pushing the limits of LLMs’ understanding beyond superficial pattern recognition. By systematically studying LLMs’ performance on this dataset, valuable insights can be gained into the current state and future directions of causal reasoning in artificial intelligence. The results show that even for simple everyday activities, causal reasoning proves challenging for current LLMs, highlighting the need for further advancements in this critical area. The researchers provide multiple methods of evaluating this causal reasoning and include the concept of Average Treatment Effect in their analysis for a more rigorous evaluation.

COLD Framework#

The COLD (Causal reasOning in cLosed Daily activities) framework offers a novel approach to evaluating causal reasoning capabilities in Large Language Models (LLMs). Its core innovation lies in focusing on closed, everyday activities (like making coffee or boarding an airplane), creating a controlled environment that reduces the influence of extraneous world knowledge. This contrasts with open-ended causal reasoning benchmarks, where LLMs might rely on memorized patterns rather than genuine causal understanding. By using script knowledge to structure causal queries, COLD facilitates the generation of a vast number of questions, approaching a mini-Turing test in scale. This rigorous evaluation methodology allows for a deeper assessment of LLMs’ true causal reasoning abilities, moving beyond superficial pattern recognition and towards a more nuanced understanding of genuine world knowledge.

LLM Evaluation#

Evaluating Large Language Models (LLMs) is a complex process. Benchmarking LLMs requires careful consideration of various factors, including the tasks chosen, the evaluation metrics used, and the datasets employed. Robust evaluation should involve a diverse range of tasks to assess different capabilities, rather than focusing solely on narrow capabilities, or using a single metric. This ensures a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of LLM performance. Furthermore, the datasets used for evaluation should be representative of real-world scenarios to allow better generalizability of the results. Bias in datasets can significantly skew evaluation outcomes, and thus careful curation is necessary to avoid perpetuating unfair biases. Finally, interpreting the results requires an understanding of the limitations and biases involved in the evaluation process itself; it’s crucial to acknowledge and address these limitations to obtain reliable and fair conclusions.

ATE Analysis#

ATE (Average Treatment Effect) analysis, in the context of causal inference within a research paper, likely involves estimating the causal effect of an intervention on an outcome. This is done by comparing the outcome under the intervention (treatment) to the outcome without the intervention (control). The method likely involves leveraging observational data and adjusting for confounding factors, possibly using techniques like matching, weighting, or regression. A key challenge is addressing confounding variables, those that influence both the treatment and the outcome, potentially biasing the ATE estimate. The paper likely describes specific methods used to estimate ATE, such as regression-based approaches or propensity score matching, and presents the results of the analysis, including confidence intervals or p-values to assess the statistical significance of the findings. The discussion of ATE will likely include limitations of the approach, such as potential biases from unobserved confounders or violations of the assumptions underlying the chosen causal inference method. Results may reveal significant or non-significant ATE estimates, leading to conclusions about the causal effect of the intervention. The analysis would then be discussed in the context of the research question and existing literature. If multiple ATE estimates are obtained through different methodologies, a comparison and analysis of the different estimates are essential to determine any consistency and robustness.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section presents several promising avenues for research. Expanding the scope of daily activities beyond the five currently examined would significantly enhance the dataset’s generalizability and create a more comprehensive benchmark for evaluating causal reasoning capabilities. The authors also suggest developing more complex causal queries, moving beyond simple cause-effect pairs to incorporate confounders and longer causal chains. This would create a more nuanced and challenging test of an LLM’s genuine understanding of causality. Furthermore, investigating the training of language models with the generated causal queries to better understand whether causal reasoning abilities can be learned is suggested. Finally, the authors propose exploring diverse types of causal queries, extending beyond simple causal triplets to create a richer evaluation framework, which would further strengthen the capabilities of the proposed COLD framework.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure illustrates the ‘closed-world’ assumption in COLD. The left side shows how daily activities are self-contained; events before and after the activity are considered independent. The right side displays a causal graph for the ‘Going Grocery Shopping’ activity, highlighting how certain events (colliders) influence the relationships between others. The colors help to distinguish conditionally independent event clusters.

read the caption

Figure 2: Left: the figure represents the closed nature of daily real-world activities (capturing commonsense, commonly understood by humans), start and end given the context of the task, i.e., the pre-activity world and post-activity world activities marginalize out the dependence of event occurring during the activity with the rest of the world. Right: Causal Graph for “going grocery shopping.” Notice the collider (red nodes) makes the independent set of nodes (highlighted in different colors) unconditionally independent in the causal graph. In contrast, when given a condition on a collider ('put bags in cart', the two clusters (yellow and blue) become dependent (if collider is observed, both yellow and blue clusters may have been observed as well).

🔼 The figure illustrates two concepts. The left side shows how the COLD framework considers only events within a closed, well-defined daily activity, ignoring events outside that activity’s timeframe. The right side provides a causal graph example for the ‘Going Grocery Shopping’ activity, highlighting how events are causally linked and how conditional dependencies (represented by colliders) affect the independence of event clusters within the activity.

read the caption

Figure 2: Left: the figure represents the closed nature of daily real-world activities (capturing commonsense, commonly understood by humans), start and end given the context of the task, i.e., the pre-activity world and post-activity world activities marginalize out the dependence of event occurring during the activity with the rest of the world. Right: Causal Graph for “going grocery shopping.” Notice the collider (red nodes) makes the independent set of nodes (highlighted in different colors) unconditionally independent in the causal graph. In contrast, when given a condition on a collider ('put bags in cart', the two clusters (yellow and blue) become dependent (if collider is observed, both yellow and blue clusters may have been observed as well).

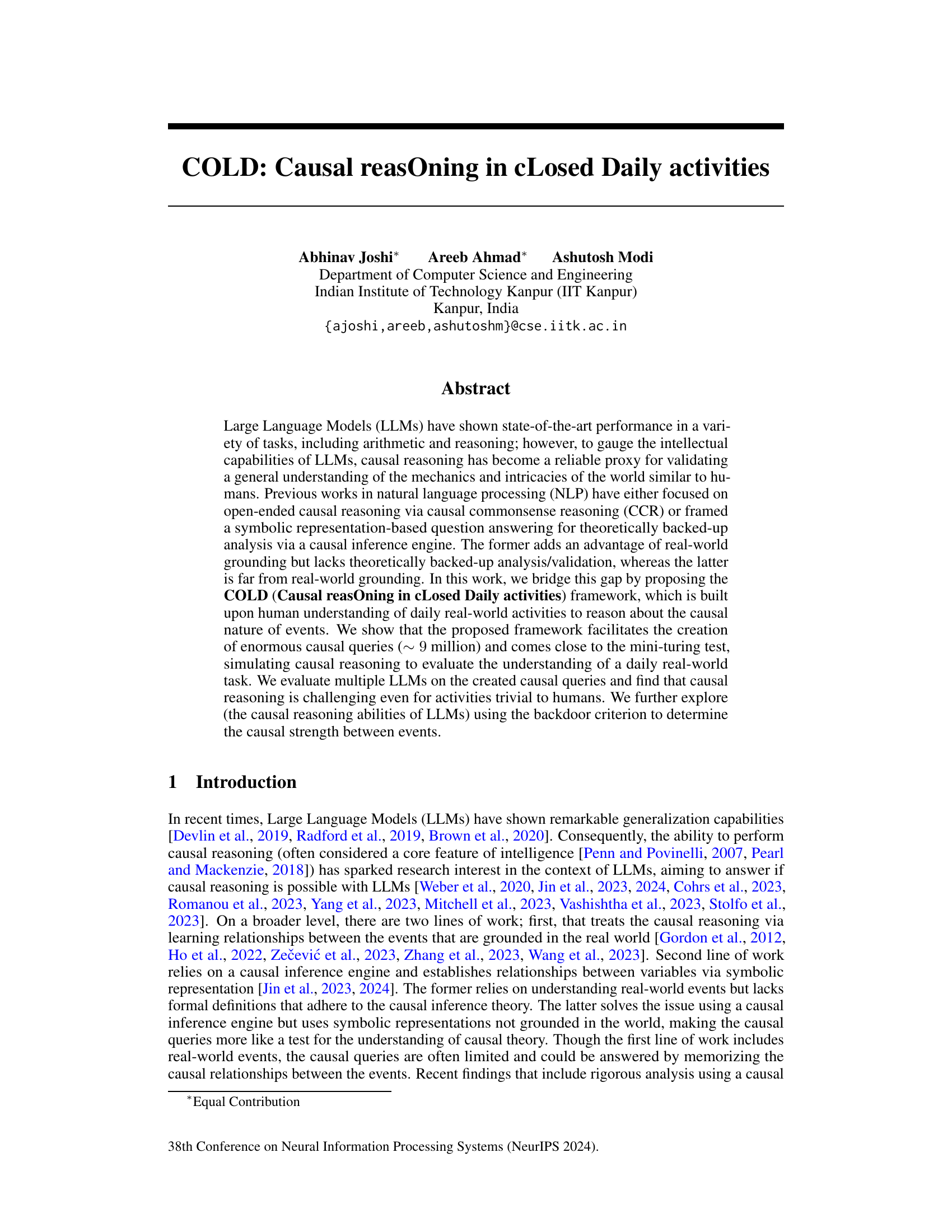

🔼 This figure illustrates the COLD framework’s process of creating causal query triplets for evaluating LLMs’ causal reasoning abilities. It starts with crowdsourced human-written event descriptions, which are used to construct observational and causal graphs. An algorithm processes these graphs to generate numerous causal query triplets, each consisting of a premise, a question, and two choices. These triplets test the LLMs’ ability to understand cause-and-effect relationships by using counterfactual reasoning to determine the most plausible outcome.

read the caption

Figure 3: The proposed COLD framework for evaluating LLMs for causal reasoning. The human-written Event Sequence Descriptions (ESDs) are obtained from crowdsource workers and include a telegrammic-style sequence of events when performing an activity. The Observational Graph and the Causal Graph for an activity are used to create causal query triplets (details in Algorithm 1), shown towards the right. Using counterfactual reasoning, “going to the kitchen” is possible without going to the market (if the ingredients are already available), making “come home with the ingredients.” a more plausible effect among the given choices. Similarly, in the second example, the event “going to market” has no direct relation with the event “heating the oven”.

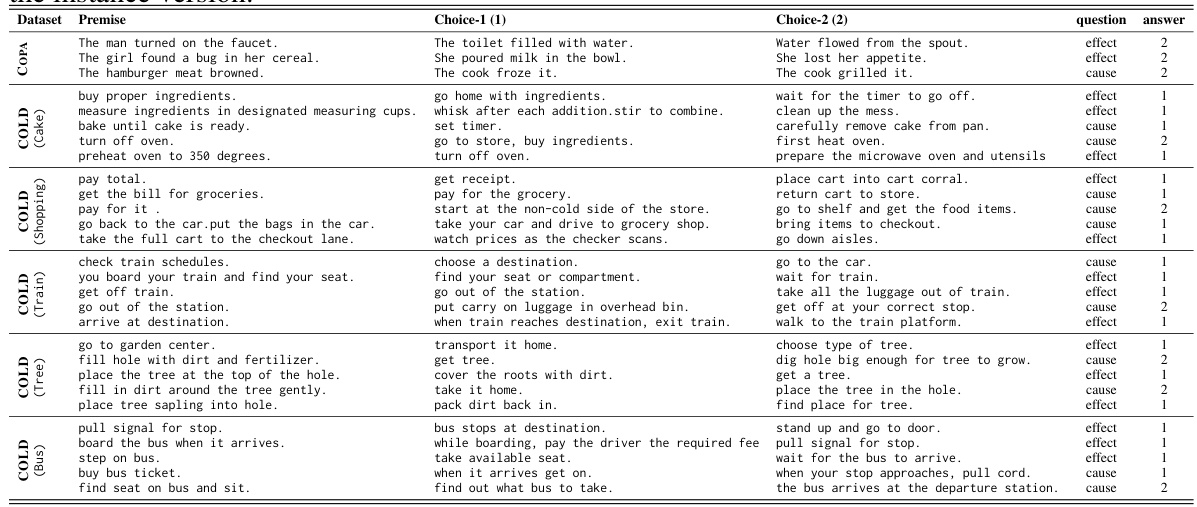

🔼 This figure shows a causal graphical model where event E₁ happens before event E₂. The variable z represents all the events that occur before E₁ in a given trajectory. The arrows indicate causal relationships, suggesting that z influences both E₁ and E₂, and E₁ causes E₂.

read the caption

Figure 4: Causal Graphical Model of Events. E₁ temporally precedes E₂, and z is trajectory variable, which assumes a values t where t ∈ All trajectories from start to E₁

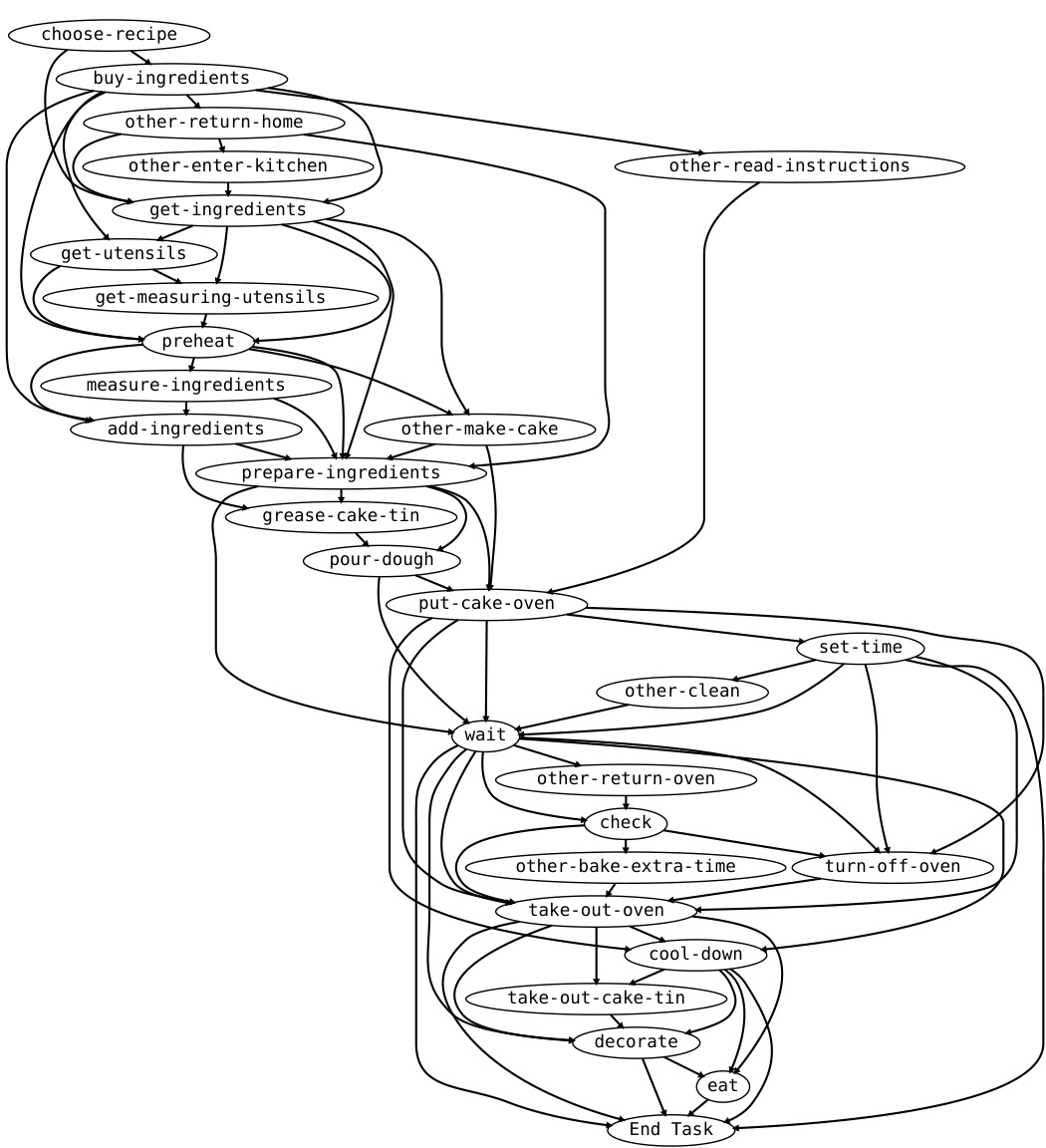

🔼 This figure is an observational graph representing the steps involved in baking a cake. The nodes represent individual actions or events in the process (e.g., ‘choose-recipe,’ ‘buy-ingredients,’ ‘preheat,’ ‘pour-dough,’ etc.). The edges show the possible transitions or sequences between these events. The graph depicts the various ways a person might bake a cake, not necessarily a strict linear progression. Some actions might be optional (indicated by the multiple edges from certain nodes), and some might occur concurrently or out of a strict order. The graph demonstrates the complexity and variability inherent in real-world activities, highlighting that even something as seemingly straightforward as baking a cake involves a multitude of choices and potential paths.

read the caption

Figure 9: The figure shows the “observational graph” for the activity Baking a Cake.

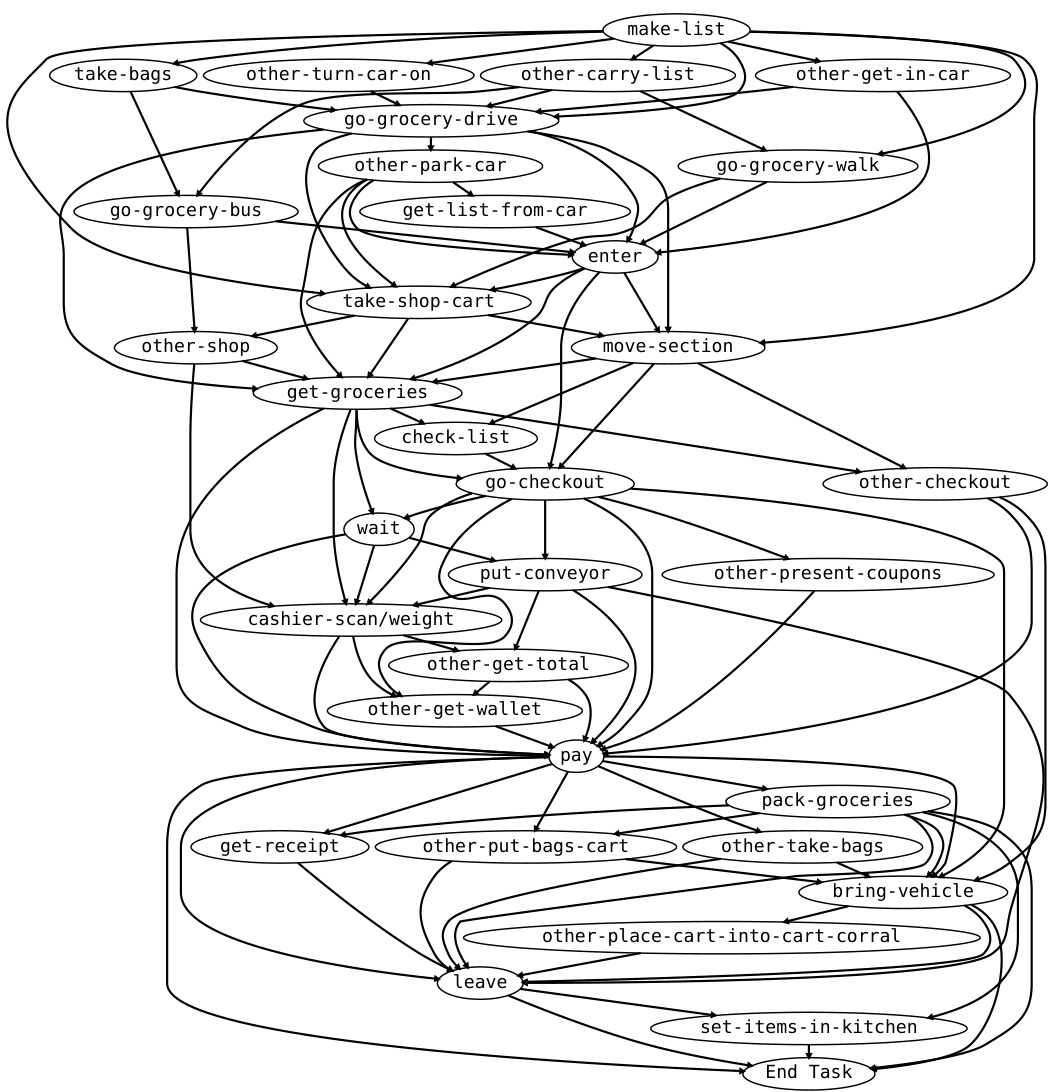

🔼 This figure is a graphical representation of the various events involved in the activity of ‘Going Grocery Shopping.’ Nodes represent events (e.g., ‘make-list,’ ’take-shop-cart,’ ‘pay’), and edges show the possible transitions or causal relationships between them. The graph captures the flow of events in a typical grocery shopping trip, illustrating different paths based on choices made (e.g., going by car, bus, or walking). The structure represents the sequence and potential order of events but doesn’t necessarily imply strict causality in all cases. The layout is organized to show clusters of related events.

read the caption

Figure 10: The figure shows the “observational graph” for the activity Going Grocery Shopping.

🔼 This figure is an observational graph depicting the various events involved in the activity of ‘Going on a Train.’ It showcases the different steps or actions (represented as nodes), and the possible transitions between them (represented as edges). The graph shows the complexity of the activity and the various ways it can unfold. Some events may lead directly to others, while some might have several alternative paths, demonstrating the flexibility of human actions within a given activity. The graph captures the non-deterministic and sequential nature of real-world event occurrences. The nodes with the prefix ‘other-’ suggest additional or alternative actions that could occur during the activity.

read the caption

Figure 11: The figure shows the “observational graph” for the activity Going on a Train.

🔼 This figure is a graph representation of the observational data for the activity of planting a tree. Nodes represent events in the process, and edges show possible transitions between them, reflecting the various ways this task might unfold. The graph does not necessarily represent causality, but rather the possible sequences of events based on observational data gathered from human subjects performing the activity. The ‘End Task’ node indicates the completion of the process.

read the caption

Figure 12: The figure shows the 'observational graph' for the activity Planting a Tree.

🔼 This figure presents a directed acyclic graph (DAG) illustrating the relationships between events during the activity of ‘Riding on a Bus.’ Each node in the graph represents an event, such as ‘check-time-table,’ ‘find-bus,’ ‘board-bus,’ etc. The edges represent the possible transitions or dependencies between events, showing how events in the activity might lead to other events. The graph provides a visual representation of the various ways that this daily activity might unfold. It is important to note that this is an observational graph capturing common human experiences; it does not reflect all possible scenarios or causal relationships between events.

read the caption

Figure 13: The figure shows the “observational graph” for the activity Riding on a Bus.

More on tables

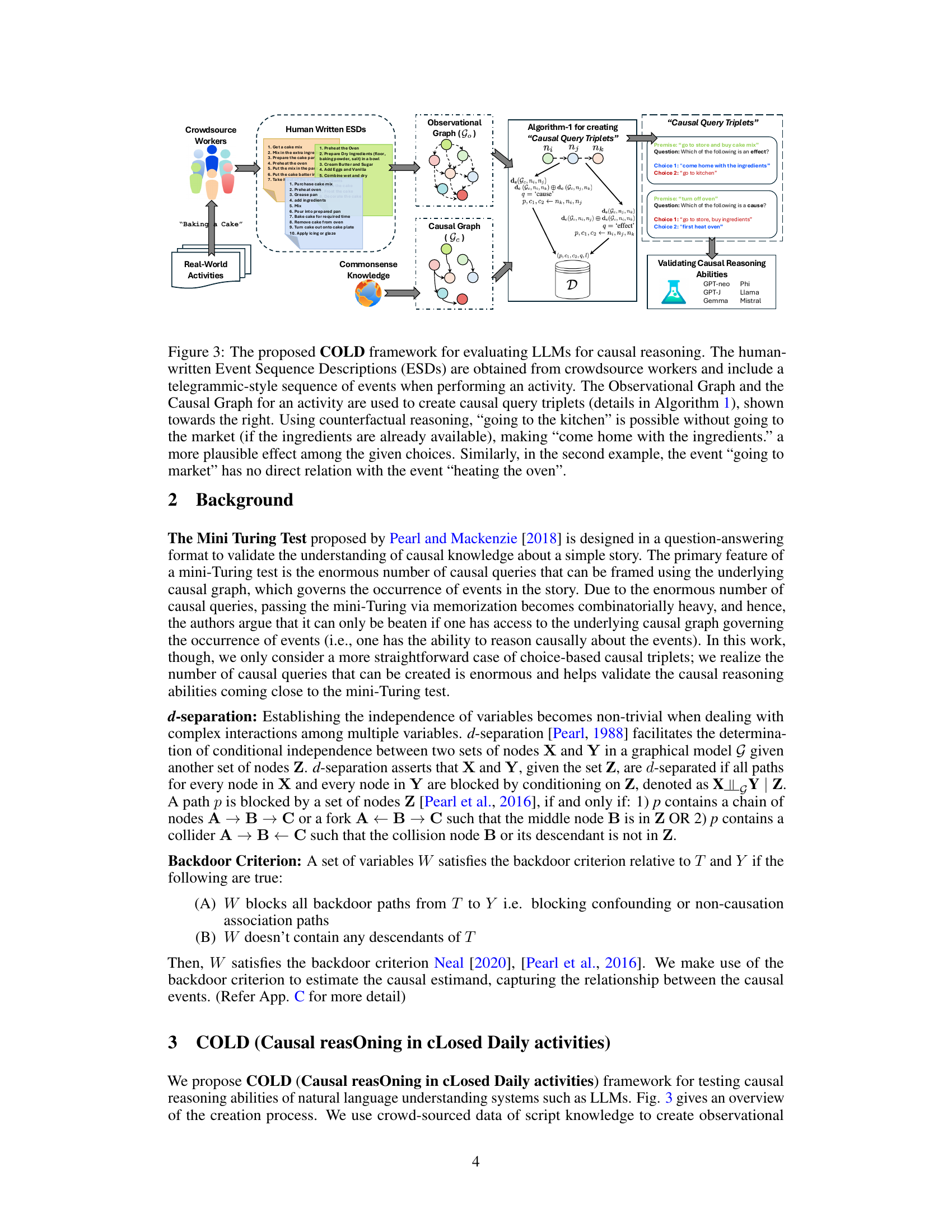

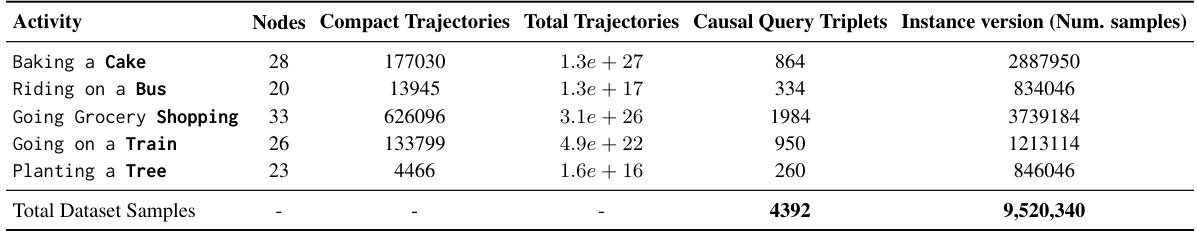

🔼 This table presents a quantitative summary of the data generated using the COLD framework for five different daily activities. It shows the number of nodes (events) in the observational graph for each activity, the number of compact trajectories (sequences of events) and the total number of trajectories possible from those compact trajectories. It also shows the number of causal query triplets generated for each activity (this is used in the evaluation) and the number of samples in the instance version of the data. The instance version includes different textual descriptions of the same event, increasing the dataset size. The last row provides the dataset total.

read the caption

Table 2: The table provides details of the observational graph (Go) for 5 activities. The Causal Query Triplets represent the total number of triplets generated via Algorithm 1. The instance version shows the number of samples present in the instance version (including different text instances describing the same event) of the created dataset. Table 1 shows a small sample taken for 2 activities. Overall, the huge number of samples highlights the exhaustive nature of evaluation that can be done for LLMs.

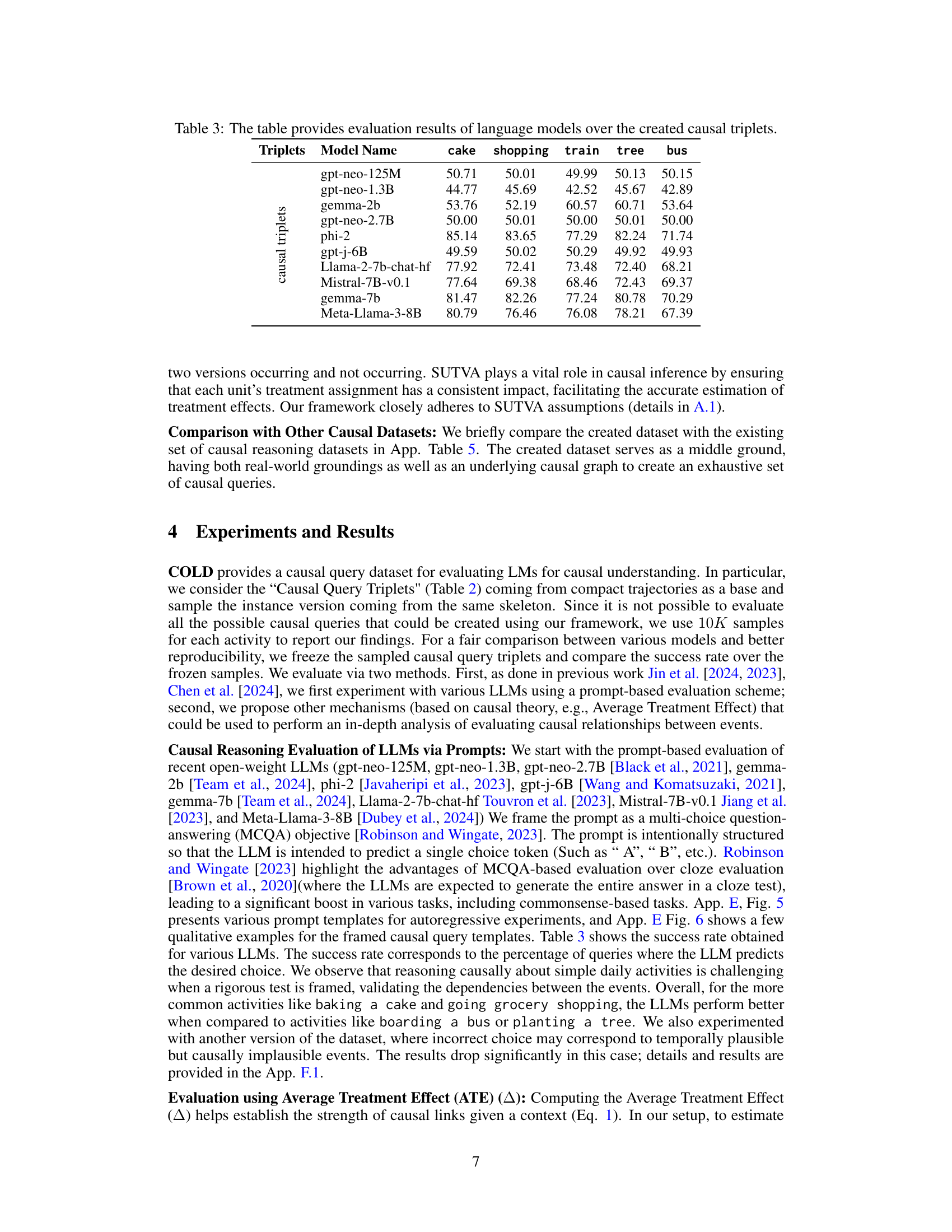

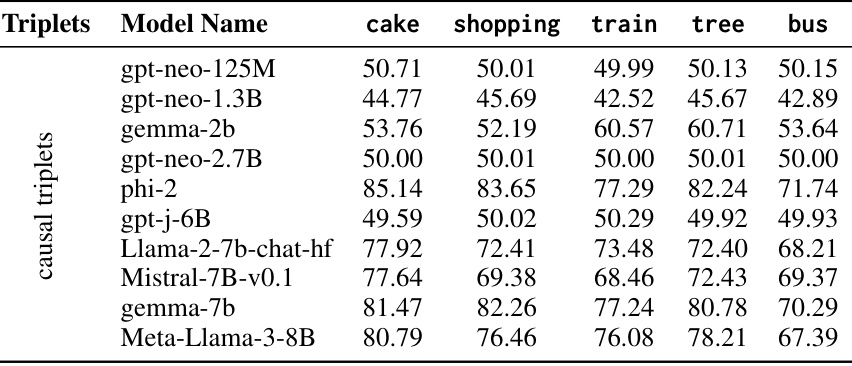

🔼 This table presents the performance of various large language models (LLMs) on a causal reasoning task. The models were evaluated on a dataset of causal triplets, which are sets of three events (premise, choice 1, choice 2) designed to test causal understanding. The table shows the accuracy of each model on five different activities: baking a cake, grocery shopping, riding a train, planting a tree, and riding a bus. The results reveal the relative strengths and weaknesses of different LLMs in performing causal reasoning tasks.

read the caption

Table 3: The table provides evaluation results of language models over the created causal triplets.

🔼 This table presents the performance of various language models on a causal reasoning task. The models were evaluated using a dataset of causal triplets generated from the COLD framework. The table shows the accuracy of each model across different daily activities (e.g., Baking a cake, Going grocery shopping). The results highlight the challenges involved in causal reasoning, even for tasks that are trivial for humans.

read the caption

Table 3: The table provides evaluation results of language models over the created causal triplets.

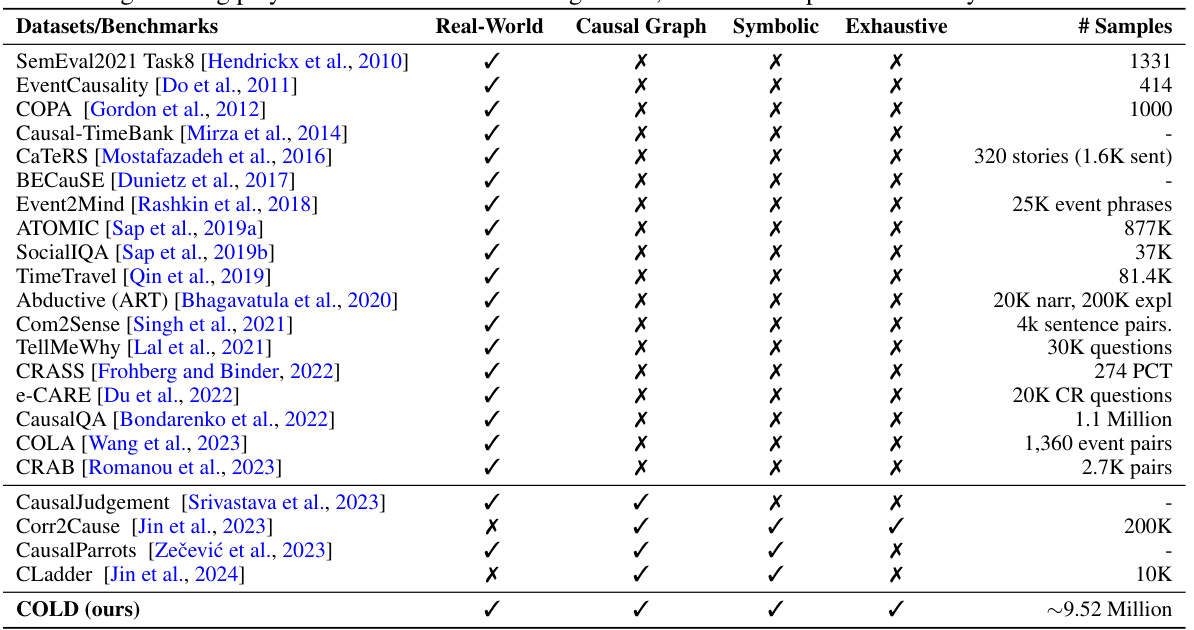

🔼 This table compares various existing causal reasoning datasets and benchmarks used to evaluate Large Language Models (LLMs). It highlights key differences in their design, specifically focusing on whether they incorporate real-world events, utilize causal graphs, employ symbolic representations, and whether they provide an exhaustive set of causal queries (meaning a very large number of queries). The table aids in understanding the strengths and weaknesses of various methods used to assess an LLM’s causal reasoning capabilities. The last column shows the number of samples available in each dataset.

read the caption

Table 5: Comparison of causal experimental settings used in prior LLM evaluation benchmarks. The real-world grounding plays a crucial role in evaluating LLMs, which is not present in the symbolic benchmarks.

🔼 This table presents the results of a human validation study conducted to assess the performance of humans on the causal reasoning task using a subset of 100 causal query triplets (20 triplets per activity). The table shows the individual performance of five human subjects across five activities: baking a cake, going grocery shopping, going on a train, planting a tree, and riding on a bus. The average human performance across all activities was 92.20%, indicating a high level of accuracy in causal reasoning for these everyday activities.

read the caption

Table 6: Human validation done for a small sample of 100 causal query triplets. Overall we find that humans do perform well in causal reasoning about these daily activities.

🔼 This table presents the performance of several large language models on a causal reasoning task. The models were evaluated on a dataset of causal query triplets, which were created using the COLD framework. The table shows the accuracy of each model on five different activities: baking a cake, grocery shopping, riding on a train, planting a tree, and riding on a bus. The results indicate the relative difficulty of these tasks for language models and highlight the strengths and weaknesses of different model architectures in performing causal reasoning.

read the caption

Table 3: The table provides evaluation results of language models over the created causal triplets.

🔼 This table presents the performance of various language models on the causal reasoning task using the COLD dataset. It shows the accuracy of each model in predicting the correct cause or effect in a causal query triplet for five different daily activities: Baking a Cake, Going Grocery Shopping, Going on a Train, Planting a Tree, and Riding on a Bus. The results highlight the challenges posed by the causal reasoning task, even for activities that are trivial for humans.

read the caption

Table 3: The table provides evaluation results of language models over the created causal triplets.

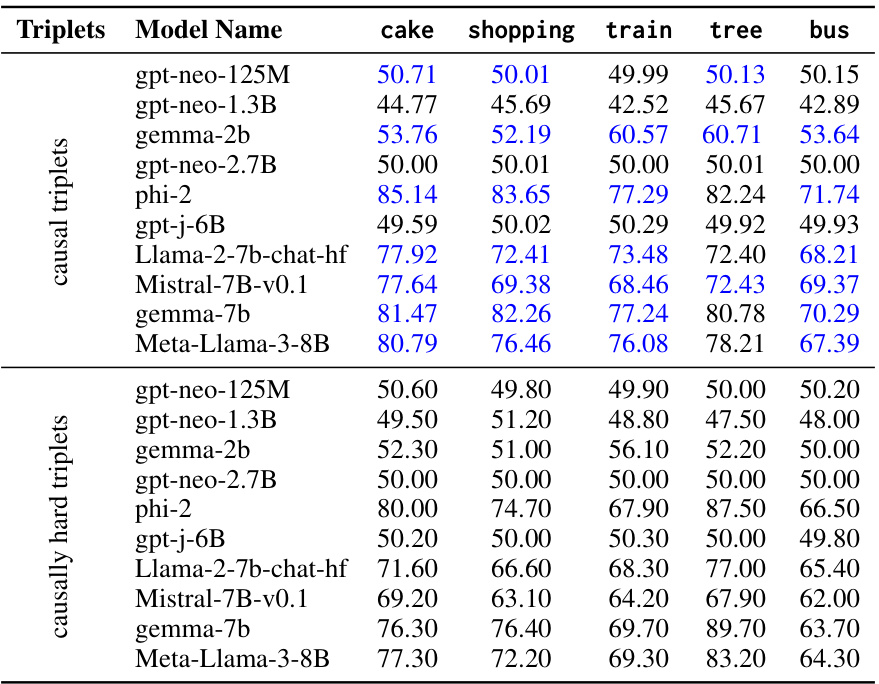

🔼 This table presents the performance of several large language models on two different sets of causal query triplets: causal triplets and causally hard triplets. Causally hard triplets are designed to be more challenging, introducing temporally close but not causally related options. The table shows the accuracy of each model on each activity (cake, shopping, train, tree, bus) for both triplet types. This allows for a comparison of model performance under varying levels of difficulty in causal reasoning.

read the caption

Table 7: The table provides evaluation results of Language models over the causal and causal temporal triplets.

Full paper#