TL;DR#

Current methods for combining large language models (LLMs) either are computationally expensive (ensembling) or ineffective when multiple LLMs perform well (routing). This paper introduces RouterDC, a novel query-based routing model. RouterDC addresses these limitations by leveraging dual contrastive learning, using two contrastive losses to train an encoder and LLM embeddings.

RouterDC’s dual contrastive training strategy pulls query embeddings close to top-performing LLMs while pushing away from weaker ones. This approach, combined with a sample-sample contrastive loss to improve training stability, leads to a significant improvement over existing methods and individual top-performing LLMs in both in- and out-of-distribution tasks. The model is parameter and computationally efficient, offering a promising approach for assembling LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel method for assembling large language models (LLMs) that significantly improves performance over existing methods. RouterDC, using dual contrastive learning, effectively selects the best LLM for each query, leading to substantial gains in both in-distribution and out-of-distribution tasks. This work is highly relevant to the current trend of LLM research, offering an efficient and effective way to harness the strengths of multiple LLMs. Furthermore, it opens avenues for future research in optimizing LLM ensembles and improving the robustness and cost-effectiveness of LLM-based applications.

Visual Insights#

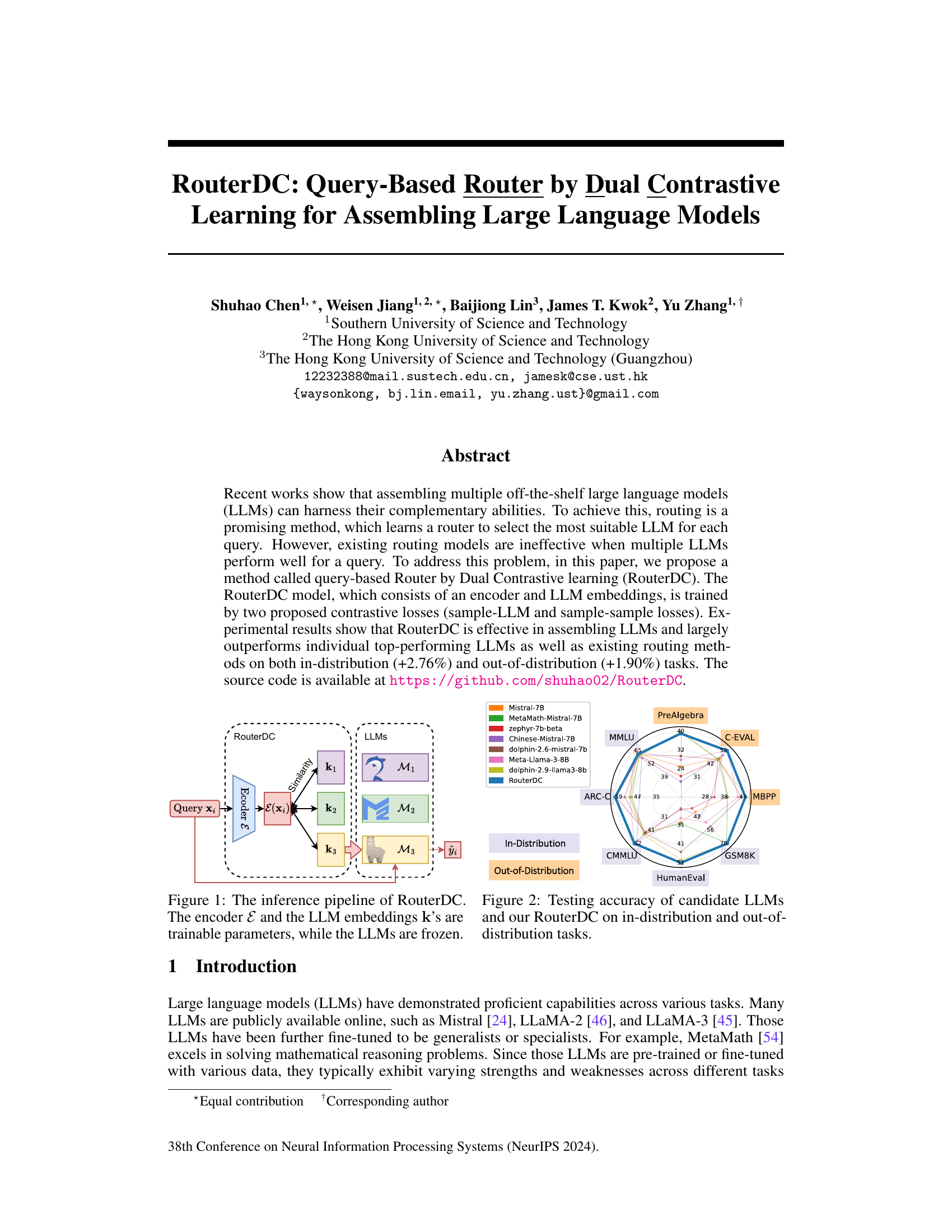

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the RouterDC model. A query (xᵢ) is fed into an encoder (E), which produces an embedding (Ɛ(xᵢ)). This embedding is then compared to learned embeddings (k₁, k₂, k₃,…) representing different Large Language Models (LLMs: M₁, M₂, M₃,…). The similarity between the query embedding and each LLM embedding determines which LLM is selected (M₃ in this example) to produce the final answer (ŷᵢ). The encoder and LLM embeddings are trainable parameters, but the LLMs themselves are kept fixed during training.

read the caption

Figure 1: The inference pipeline of RouterDC. The encoder E and the LLM embeddings k’s are trainable parameters, while the LLMs are frozen.

🔼 This table presents the performance of various LLMs and LLM assembling methods on five in-distribution tasks: MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, and HumanEval. The accuracy of each model on each task is shown, along with the total inference time. The best performing model for each task is bolded, and the second-best is underlined. This allows for a comparison of the effectiveness of different LLMs and the proposed RouterDC method in solving these in-distribution benchmark problems.

read the caption

Table 1: Testing accuracy (%) on in-distribution tasks. “Time” denotes the total inference time in minutes. The best is in bold and the second-best is underlined.

In-depth insights#

Dual Contrastive Loss#

The proposed dual contrastive loss in the RouterDC model is a crucial component for effectively assembling large language models (LLMs). It leverages two distinct contrastive learning strategies. The sample-LLM loss aims to improve the router’s ability to select the best-performing LLMs for a given query by pulling the query embedding closer to the embeddings of top-performing LLMs while pushing it away from those of poorly performing ones. This addresses limitations of existing methods which struggle when multiple LLMs perform well. However, training solely with this loss can be unstable. The sample-sample loss enhances stability by clustering similar queries and encouraging the model to produce similar representations for queries within the same cluster, ultimately boosting training robustness and generalization. The interplay between these two losses is key to RouterDC’s success, achieving superior performance compared to single LLMs and existing routing methods.

LLM Routing Methods#

LLM routing methods represent a crucial advancement in efficiently harnessing the power of multiple large language models (LLMs). Instead of querying all LLMs for every request, routing intelligently selects the most suitable LLM based on the specific input query. This approach significantly improves efficiency, reducing computational costs and latency. Effective routing relies on learning a ‘router’ model that maps input queries to the appropriate LLM. Different methods exist for training these routers, including those based on contrastive learning, which leverages similarity measures between query embeddings and LLM representations to optimize selection. Key challenges in LLM routing include robustly handling queries that are well-suited to multiple LLMs, and designing routers that generalize effectively across various query distributions and maintain high accuracy even when some LLMs are unavailable. Future work should focus on developing more sophisticated routing strategies that consider factors like task complexity, resource constraints, and potential LLM failures to ensure both efficiency and reliable performance.

RouterDC Architecture#

The RouterDC architecture centers on a dual contrastive learning approach to effectively route queries to the most suitable large language model (LLM) from a pool of candidate LLMs. It comprises two main components: an encoder and LLM embeddings. The encoder processes the input query, generating a query embedding. Simultaneously, each LLM in the pool is represented by a learned embedding vector. The key innovation lies in the dual contrastive loss function: a sample-LLM loss to pull the query embedding closer to the embeddings of top-performing LLMs for that query and push it away from poorly performing LLMs; and a sample-sample loss that encourages similar queries to have similar embeddings, improving training stability. This architecture elegantly combines query-specific routing with a robust contrastive learning framework, ensuring the selection of the optimal LLM for each query. The parameter efficiency and computational efficiency are highlighted as advantages of the system, making it a practical approach to LLM ensemble.

Experimental Results#

The ‘Experimental Results’ section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims and hypotheses presented. A strong section will meticulously detail the experimental setup, including datasets used, evaluation metrics, and baseline methods. Clear and concise presentation of results, often via tables and figures, is essential for easy understanding. Statistical significance should be reported to support claims of improvement over existing methods. The analysis should go beyond simply reporting numbers; it should discuss trends, patterns, and unexpected findings. A nuanced interpretation that acknowledges both strengths and limitations of the results is important. The discussion should directly relate the findings back to the initial research questions and hypotheses, highlighting any implications for future work. Finally, robustness analyses, such as sensitivity analysis to hyperparameter choices, can greatly strengthen the conclusions presented.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending RouterDC to handle more complex query types, such as those involving multiple sub-questions or requiring multi-modal input (text and images), would significantly broaden its applicability. Investigating the impact of different LLM architectures and sizes on RouterDC’s performance and efficiency is crucial for optimizing resource allocation and performance. Furthermore, a more thorough exploration of the interplay between different contrastive loss functions and training strategies could lead to significant improvements in routing accuracy and training stability. Research into adaptive routing strategies, that dynamically adjust the selected LLMs based on real-time feedback, could further enhance performance and robustness. Finally, developing robust methods to measure and mitigate potential biases embedded within the LLMs utilized by RouterDC is essential to ensure fairness and ethical considerations in applications.

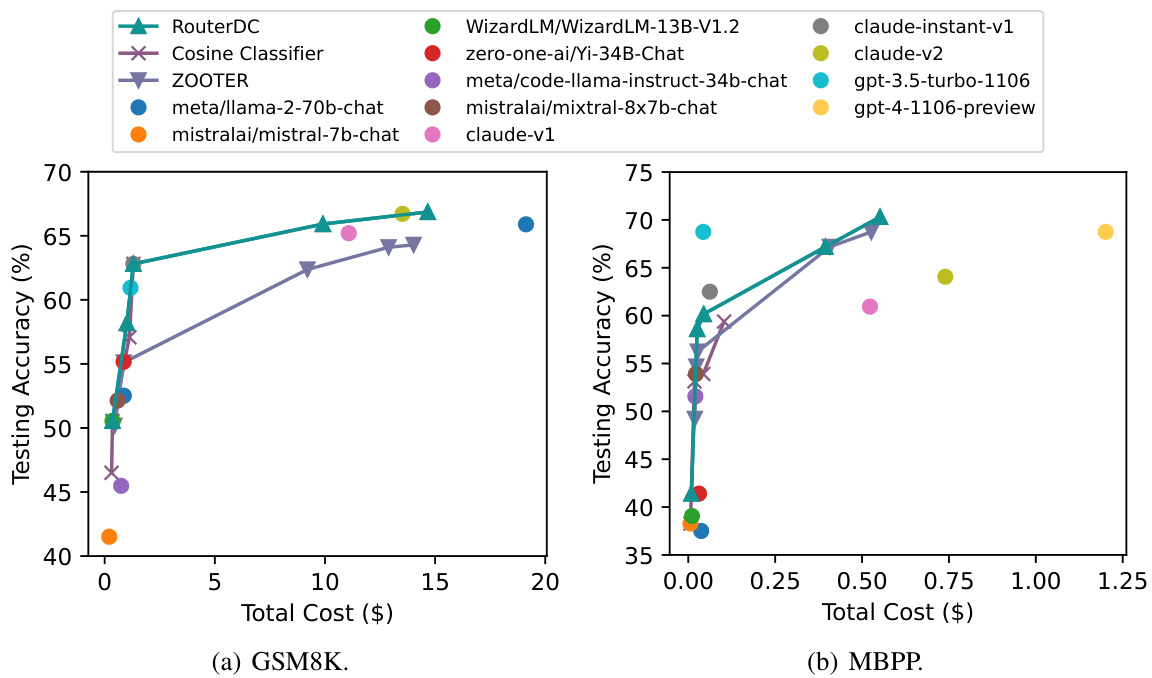

More visual insights#

More on figures

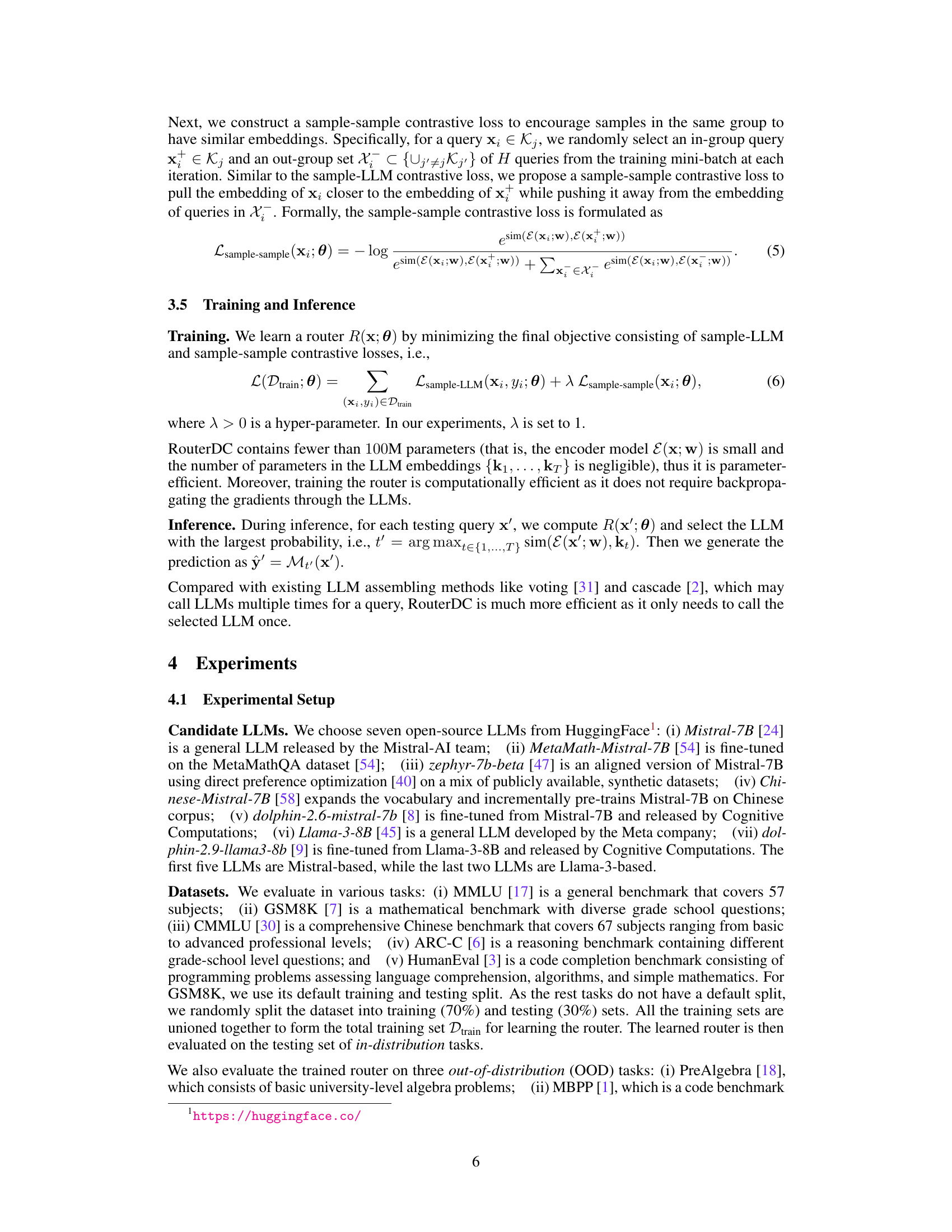

🔼 This radar chart visualizes the performance of various Large Language Models (LLMs) and the proposed RouterDC model across multiple benchmark datasets. Each axis represents a different dataset (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, HumanEval, PreAlgebra, MBPP, C-EVAL), and the values on each axis show the accuracy achieved by each model on that dataset. The in-distribution datasets are those the models were trained on, while out-of-distribution datasets are new ones. The chart allows for a direct comparison of the performance of RouterDC against individual LLMs and highlights its effectiveness in improving accuracy across multiple tasks, especially in out-of-distribution scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 2: Testing accuracy of candidate LLMs and our RouterDC on in-distribution and out-of-distribution tasks.

🔼 This figure illustrates the score distributions of multiple Large Language Models (LLMs) when responding to a sample query. The left panel shows the raw scores assigned to each LLM, revealing a significant disparity in performance, with some models achieving much higher scores than others. The right panel demonstrates the effect of softmax normalization, a common technique used to transform raw scores into probabilities. The normalization process compresses the score range, making the top performers less distinguished from the rest, which can present a challenge for selecting the most suitable LLM. The visualization helps illustrate the contrast between raw LLM performance scores and their normalized probabilities and explains the limitation of existing routing models.

read the caption

Figure 3: Score distributions of LLMs on an example query (w/ or w/o normalization).

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of the difference between the scores of the top two performing LLMs for a given query. The x-axis represents the difference in scores, and the y-axis represents the density of queries with that score difference. A large portion (64%) of the queries show a very small difference between the top two LLMs, indicating that multiple LLMs often perform similarly well for a single query. This observation highlights a limitation of existing routing methods that rely on a single best LLM for each query.

read the caption

Figure 4: Distribution of the score difference between the top two LLMs.

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of the RouterDC model. It consists of an encoder that takes a query as input and generates an embedding vector. This vector is then used to calculate similarity scores with embedding vectors representing different LLMs. The LLM with the highest similarity score is selected to answer the query. The encoder and LLM embeddings are trainable parameters, while the LLMs themselves are kept frozen during training.

read the caption

Figure 1: The inference pipeline of RouterDC. The encoder E and the LLM embeddings k's are trainable parameters, while the LLMs are frozen.

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of the RouterDC model. The model takes a query as input, which is first processed by an encoder E to generate an embedding vector. This embedding vector is then used to compute similarity scores with the embedding vectors of several different Large Language Models (LLMs). These similarity scores are used to determine which LLM is best suited to answer the query. The encoder and LLM embeddings are trainable parameters, while the LLMs themselves are kept frozen during training.

read the caption

Figure 1: The inference pipeline of RouterDC. The encoder E and the LLM embeddings k's are trainable parameters, while the LLMs are frozen.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the RouterDC model. It shows how a query (xi) is processed. First, the query is passed through an encoder (E) which produces an embedding E(xi). This embedding is then used to compute similarity scores with the embeddings of different LLMs (k1, k2, k3,…). These similarity scores are then used to select the most suitable LLM for answering the query. The encoder E and the LLM embeddings are trainable parameters, while the LLMs themselves are frozen during training. The output (ŷi) is generated from the chosen LLM.

read the caption

Figure 1: The inference pipeline of RouterDC. The encoder E and the LLM embeddings k's are trainable parameters, while the LLMs are frozen.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the RouterDC model. It shows how a query (xi) is first encoded by an encoder E to produce an embedding E(xi). This embedding is then used to compute similarity scores with the embeddings (k1, k2, k3…) of multiple Large Language Models (LLMs). The LLM with the highest similarity score is then selected to generate the final response yi. The encoder and the LLM embeddings are trainable parameters, while the LLMs themselves are kept frozen during training.

read the caption

Figure 1: The inference pipeline of RouterDC. The encoder E and the LLM embeddings k's are trainable parameters, while the LLMs are frozen.

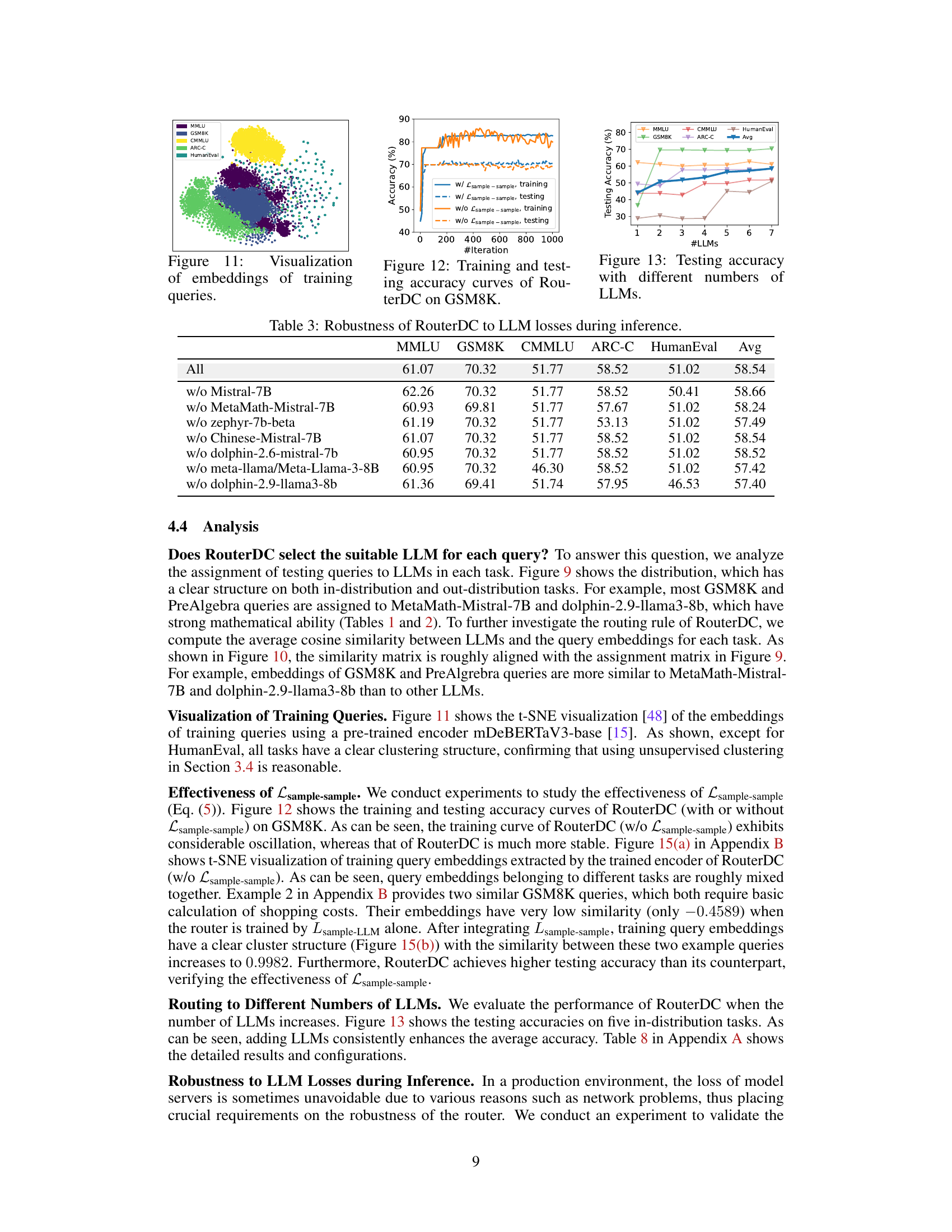

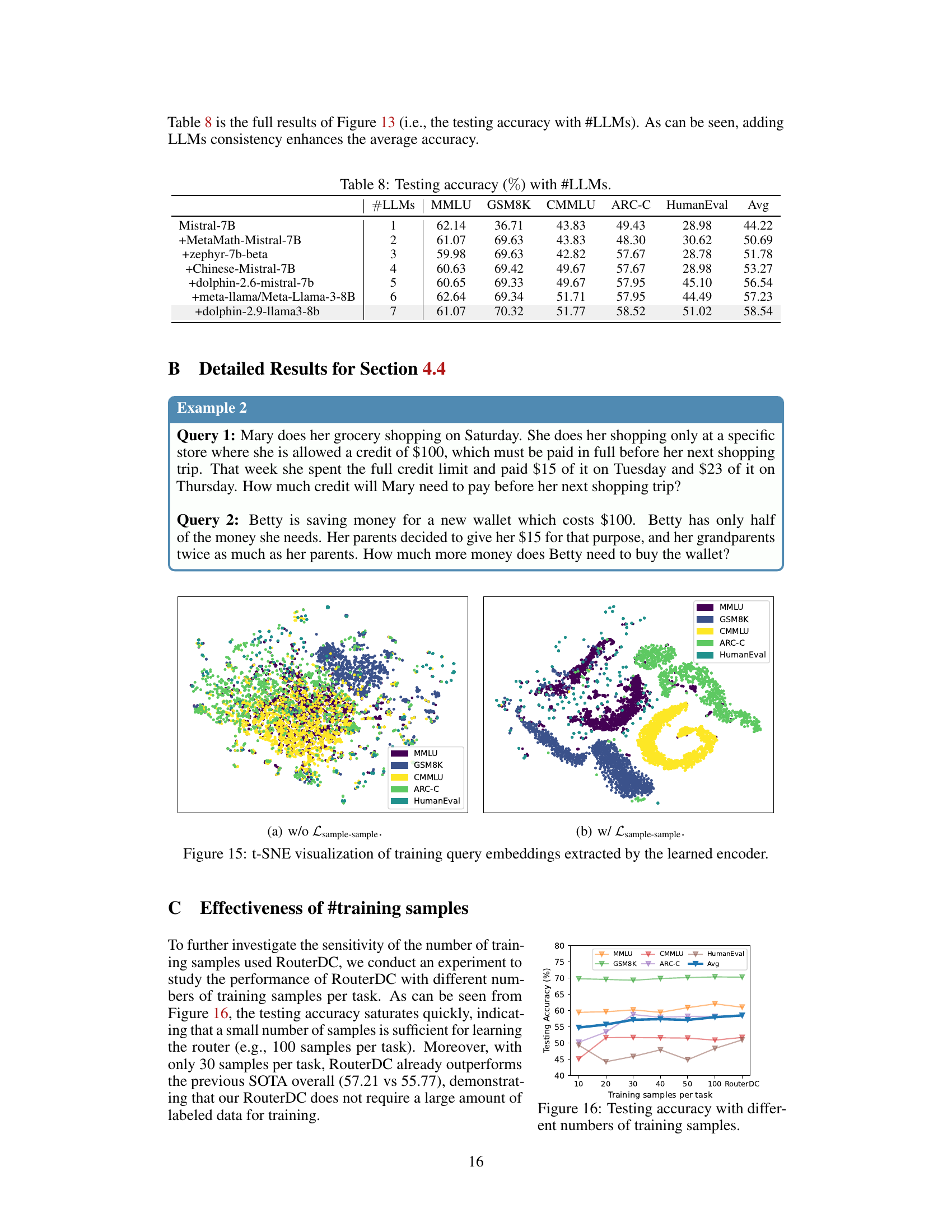

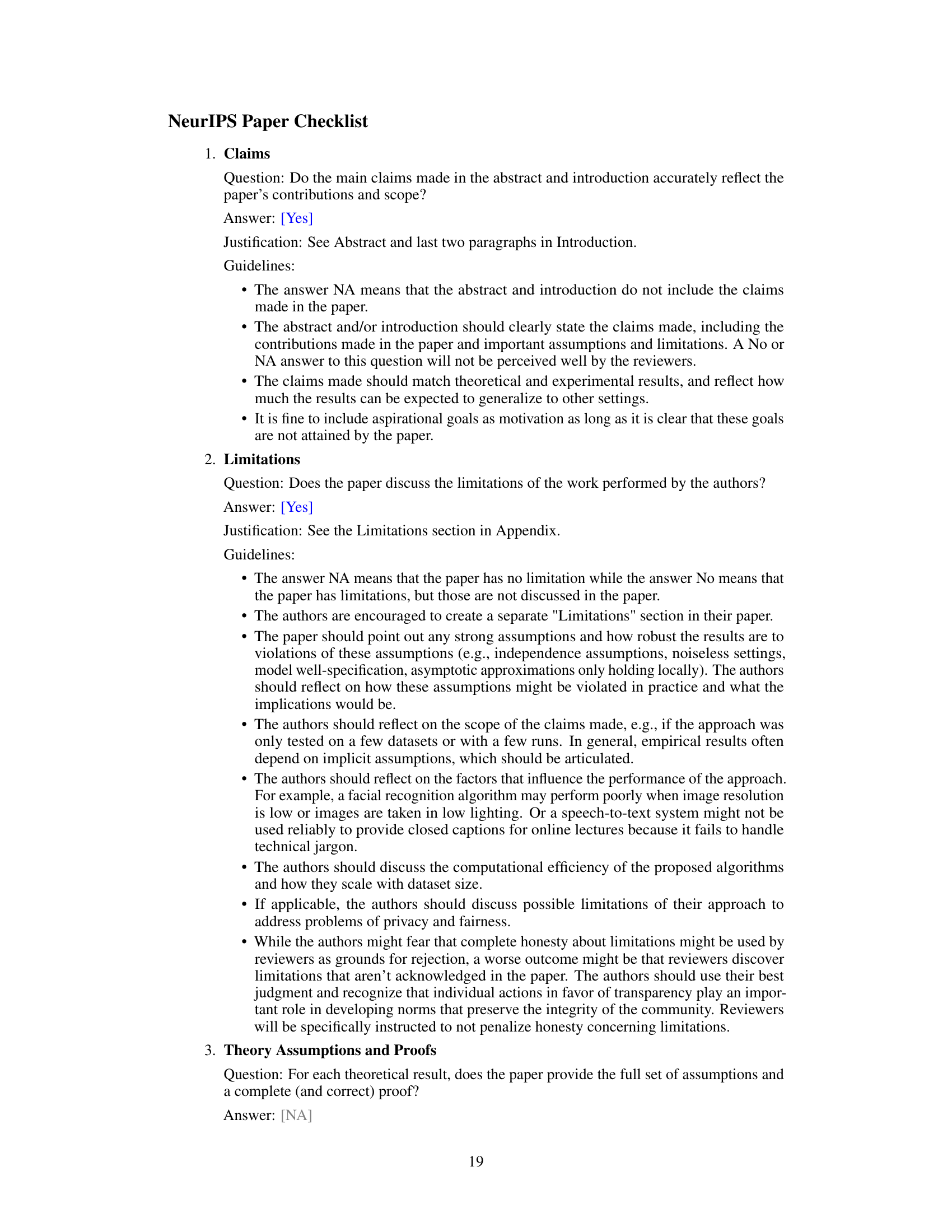

🔼 This figure visualizes the embeddings of training queries using t-SNE. Panel (a) shows the embeddings when only the sample-LLM contrastive loss is used for training, while panel (b) shows the embeddings when both sample-LLM and sample-sample contrastive losses are used. The visualization reveals the effect of the sample-sample contrastive loss in improving the clustering of similar queries.

read the caption

Figure 11: Visualization of embeddings of training queries.

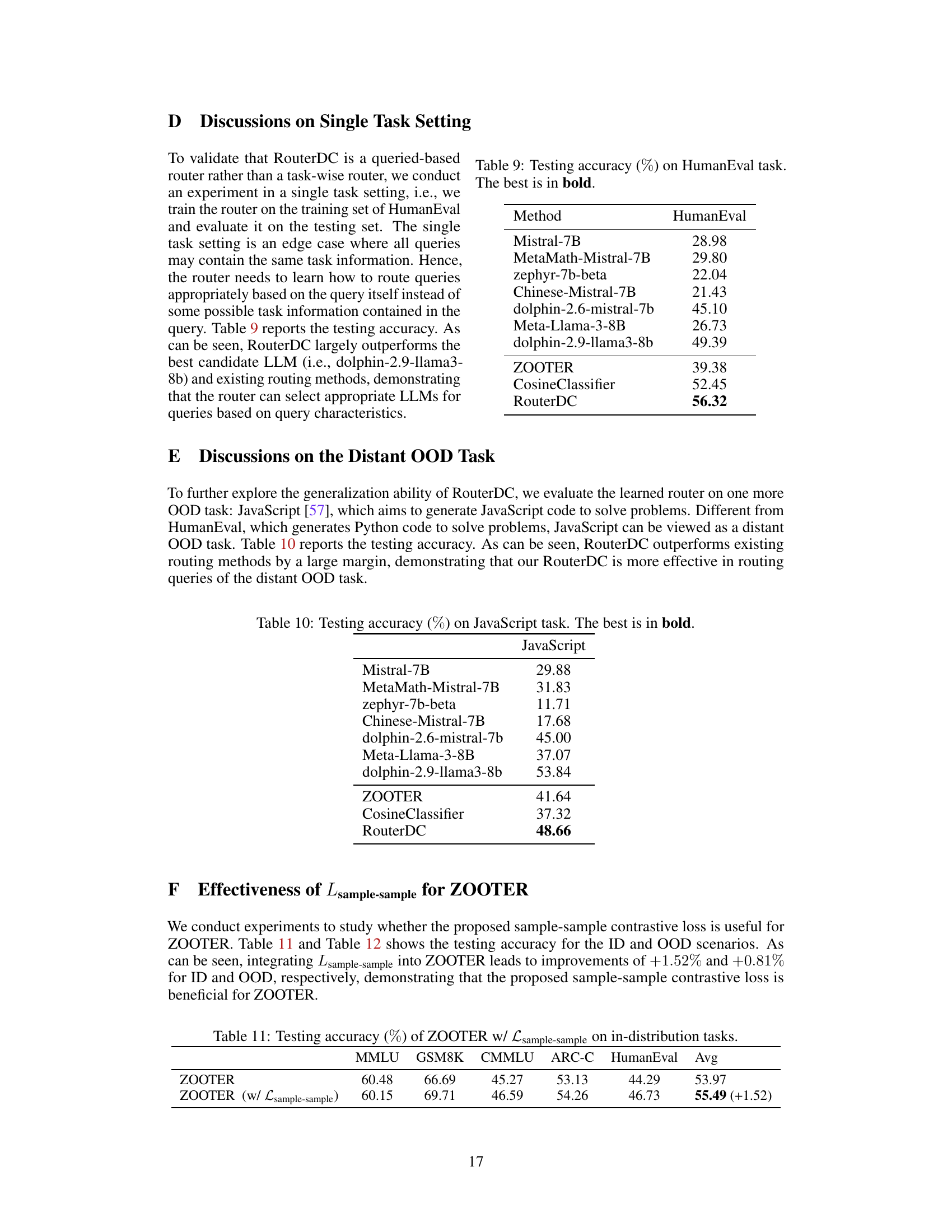

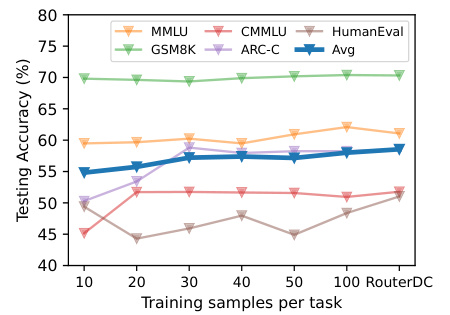

🔼 This figure shows the testing accuracy of RouterDC on five in-distribution tasks (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, and HumanEval) with varying numbers of training samples per task. The x-axis represents the number of training samples, and the y-axis represents the testing accuracy. The plot demonstrates that RouterDC’s performance improves with more training data but shows signs of saturation beyond a certain number of samples. The average accuracy across all five tasks is also shown.

read the caption

Figure 16: Testing accuracy with different numbers of training samples.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the performance of various LLMs and routing methods on three out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks: PreAlgebra, MBPP, and C-EVAL. It shows the testing accuracy and inference time for each method. The out-of-distribution tasks are different from those used in training, testing the models’ ability to generalize. The best performing method for each task and overall average is highlighted in bold, with the second-best underlined.

read the caption

Table 2: Testing accuracy (%) on out-of-distribution tasks. “Time” denotes the total inference time in minutes. The best is in bold and the second-best is underlined.

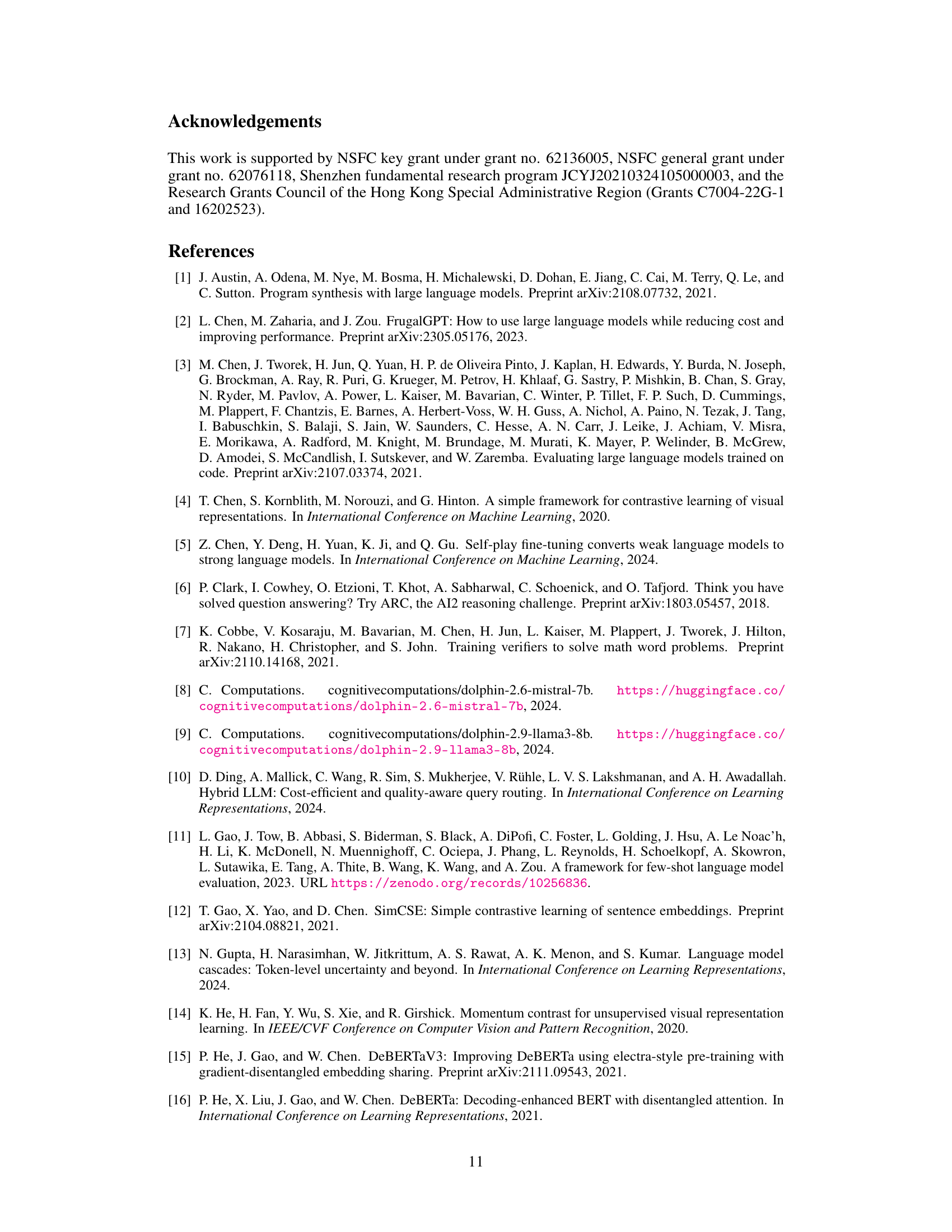

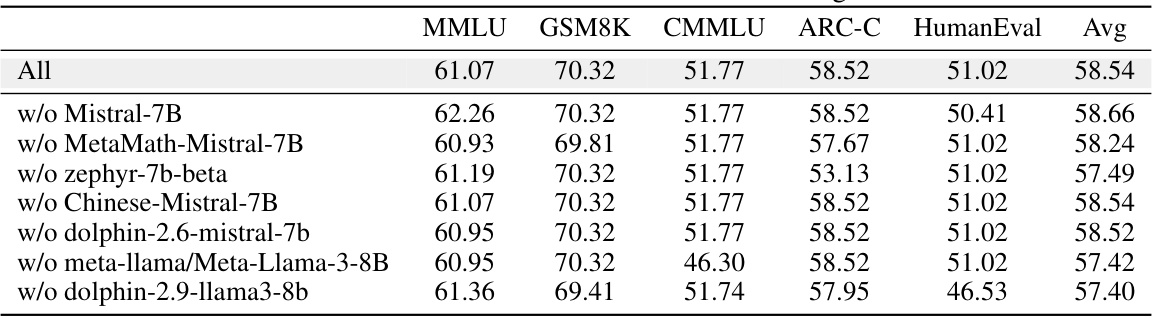

🔼 This table demonstrates the robustness of the RouterDC model by evaluating its performance when individual LLMs are removed during the inference process. It shows the testing accuracy on five in-distribution tasks (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, HumanEval) for the complete model and for versions where one of the seven LLMs is excluded. The results highlight RouterDC’s resilience to the unavailability of single LLMs during inference.

read the caption

Table 3: Robustness of RouterDC to LLM losses during inference.

🔼 This table compares the performance of RouterDC with and without using task identity information during training. It shows the testing accuracy across five different in-distribution tasks (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, HumanEval) to evaluate the impact of incorporating task identity on the model’s performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Testing accuracy(%) of RouterDC w/ or w/o task identity.

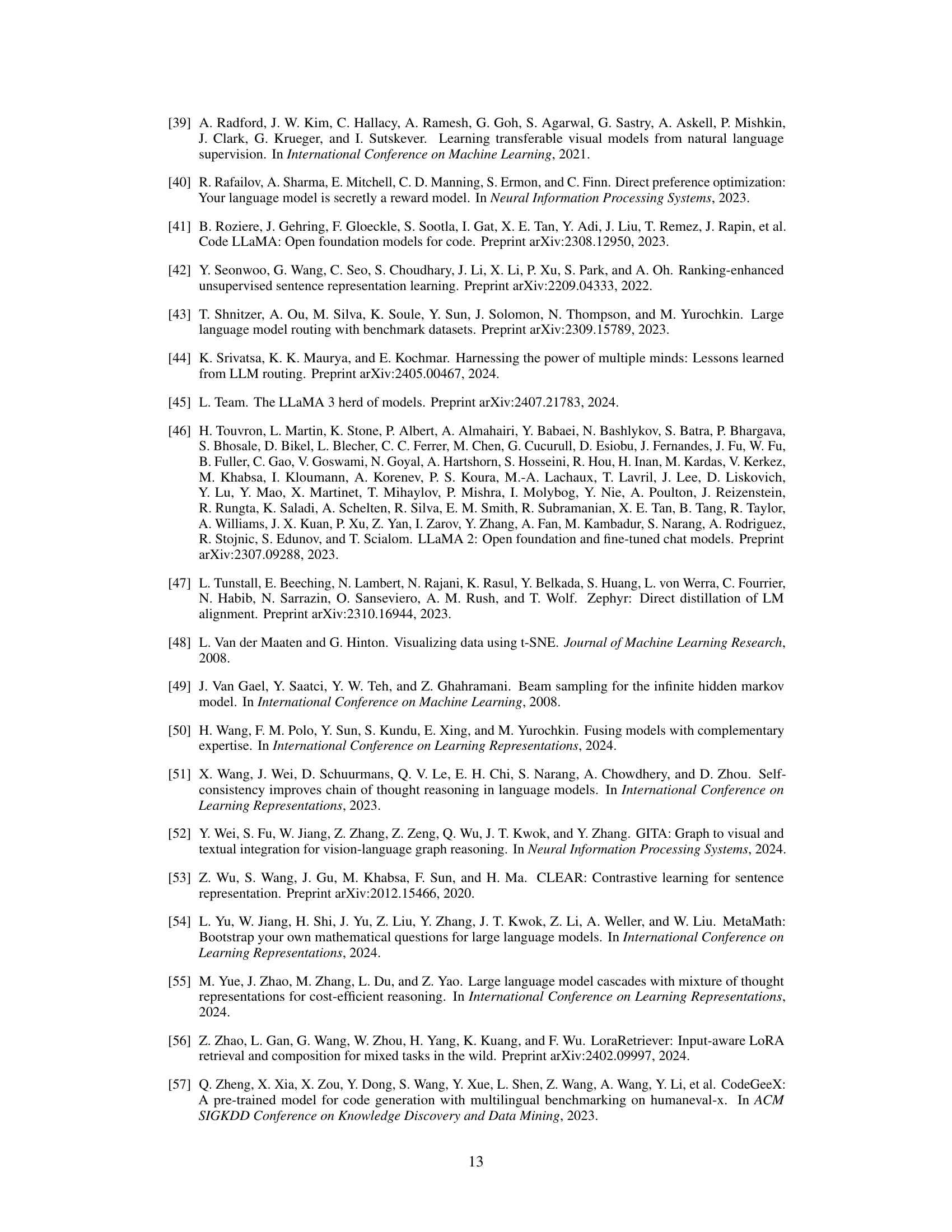

🔼 This table presents the testing accuracy achieved by the RouterDC model across five different in-distribution tasks (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, and HumanEval) with varying values of the hyperparameter λ. The hyperparameter λ balances the influence of the sample-LLM contrastive loss and the sample-sample contrastive loss in the model’s training. The table shows how the model’s performance changes across different tasks as λ is altered, demonstrating the model’s robustness to different values of this hyperparameter.

read the caption

Table 5: Testing accuracy (%) with different λ's.

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment conducted to evaluate the impact of the number of clusters (N) used in the sample-sample contrastive loss on the testing accuracy of the RouterDC model. The experiment varied the number of clusters from 2 to 30 and reported the testing accuracy for five different tasks (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, HumanEval) and the average accuracy across all tasks. The results indicate that the RouterDC model’s performance is relatively insensitive to a wide range of N values.

read the caption

Table 6: Testing accuracy (%) with different N's.

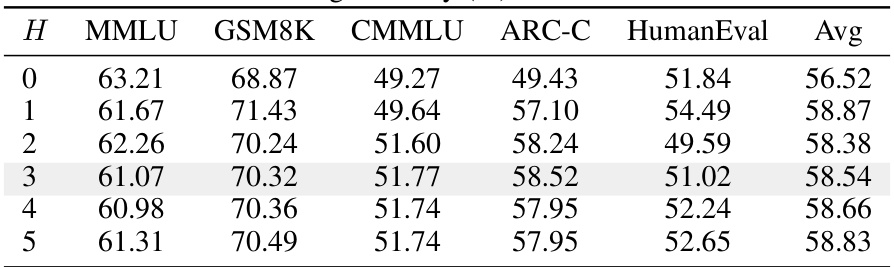

🔼 This table presents the testing accuracy results obtained from experiments using the RouterDC model with varying numbers of out-group queries (H). The results are shown for five different in-distribution tasks (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, HumanEval) along with the average accuracy across these tasks. It demonstrates how the performance of RouterDC changes when the number of out-group queries in the sample-sample contrastive loss is altered. This helps to evaluate the sensitivity of the model to this specific parameter.

read the caption

Table 7: Testing accuracy (%) with different H's.

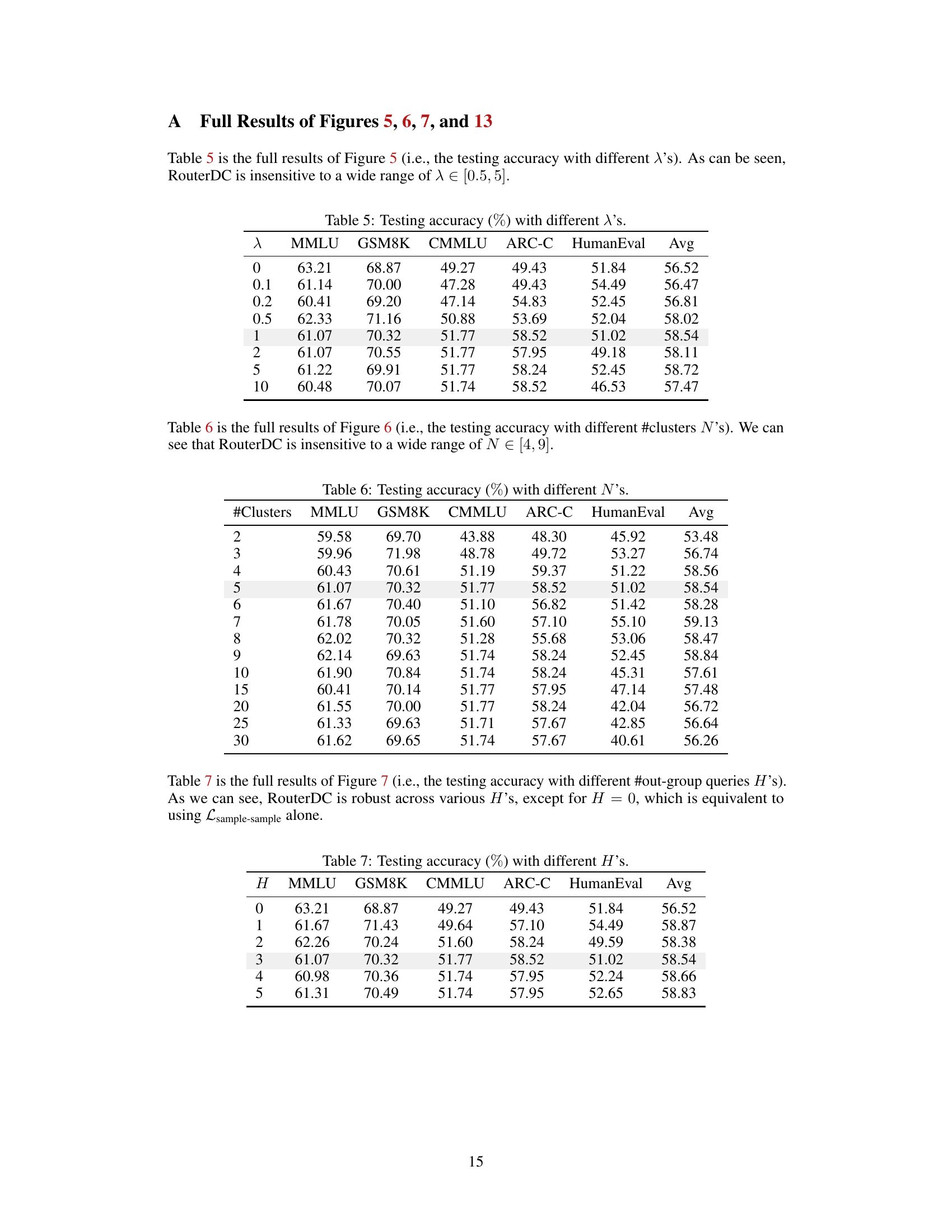

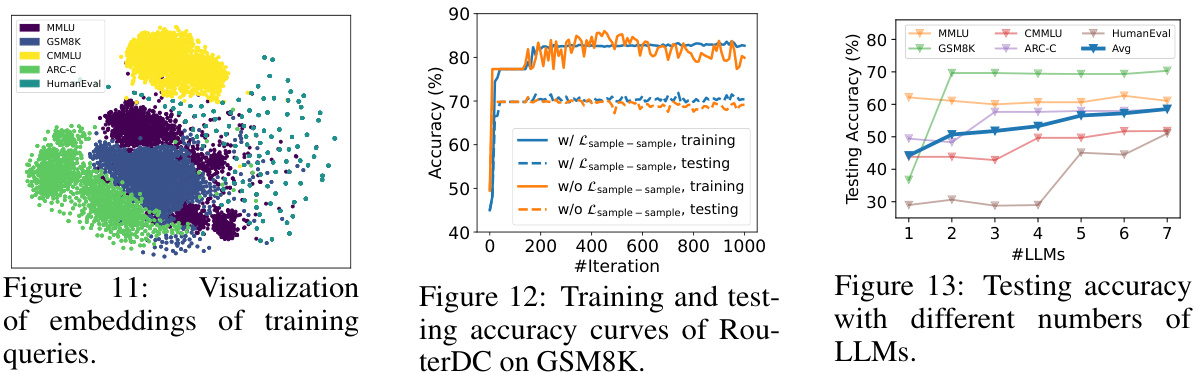

🔼 This table presents the testing accuracy results for different numbers of LLMs used in the RouterDC model. It shows how the average accuracy across five in-distribution tasks (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, HumanEval) improves as more LLMs are added to the ensemble. The table demonstrates the cumulative effect of including additional LLMs, highlighting the performance gain from using a larger ensemble of models.

read the caption

Table 8: Testing accuracy (%) with #LLMs. As can be seen, adding LLMs consistency enhances the average accuracy.

🔼 This table presents the testing accuracy achieved on the HumanEval task by different methods, including several individual LLMs and ensemble methods like ZOOTER, CosineClassifier, and the proposed RouterDC. It highlights the superior performance of RouterDC compared to other approaches, demonstrating its effectiveness in selecting the most suitable LLM for each query within this specific task.

read the caption

Table 9: Testing accuracy (%) on HumanEval task. The best is in bold.

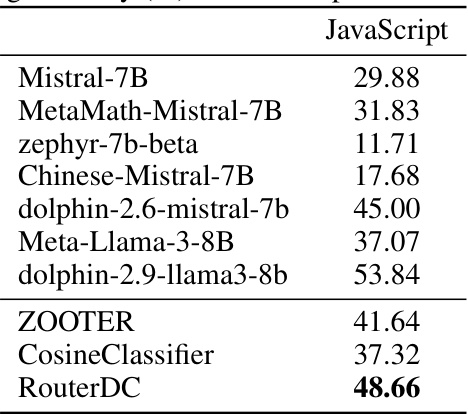

🔼 This table presents the performance of different LLMs and routing methods on a JavaScript task, which is considered an out-of-distribution task. The accuracy of each model is shown, highlighting the best-performing model in bold. This allows comparison of various models’ ability to generalize to unseen tasks, which is a key evaluation criterion for LLM routing methods.

read the caption

Table 10: Testing accuracy (%) on JavaScript task. The best is in bold.

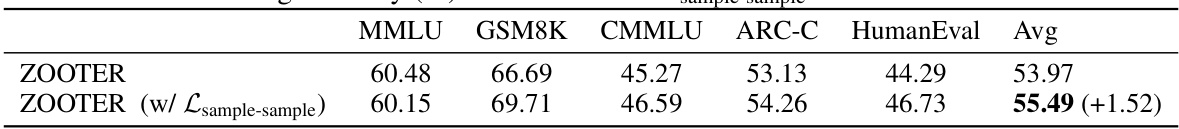

🔼 This table presents the testing accuracy of the ZOOTER model with and without the addition of the sample-sample contrastive loss, evaluated on five in-distribution tasks (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, and HumanEval). The results show a significant improvement in average accuracy when the sample-sample loss is included, highlighting its effectiveness.

read the caption

Table 11: Testing accuracy (%) of ZOOTER w/ Lsample-sample on in-distribution tasks.

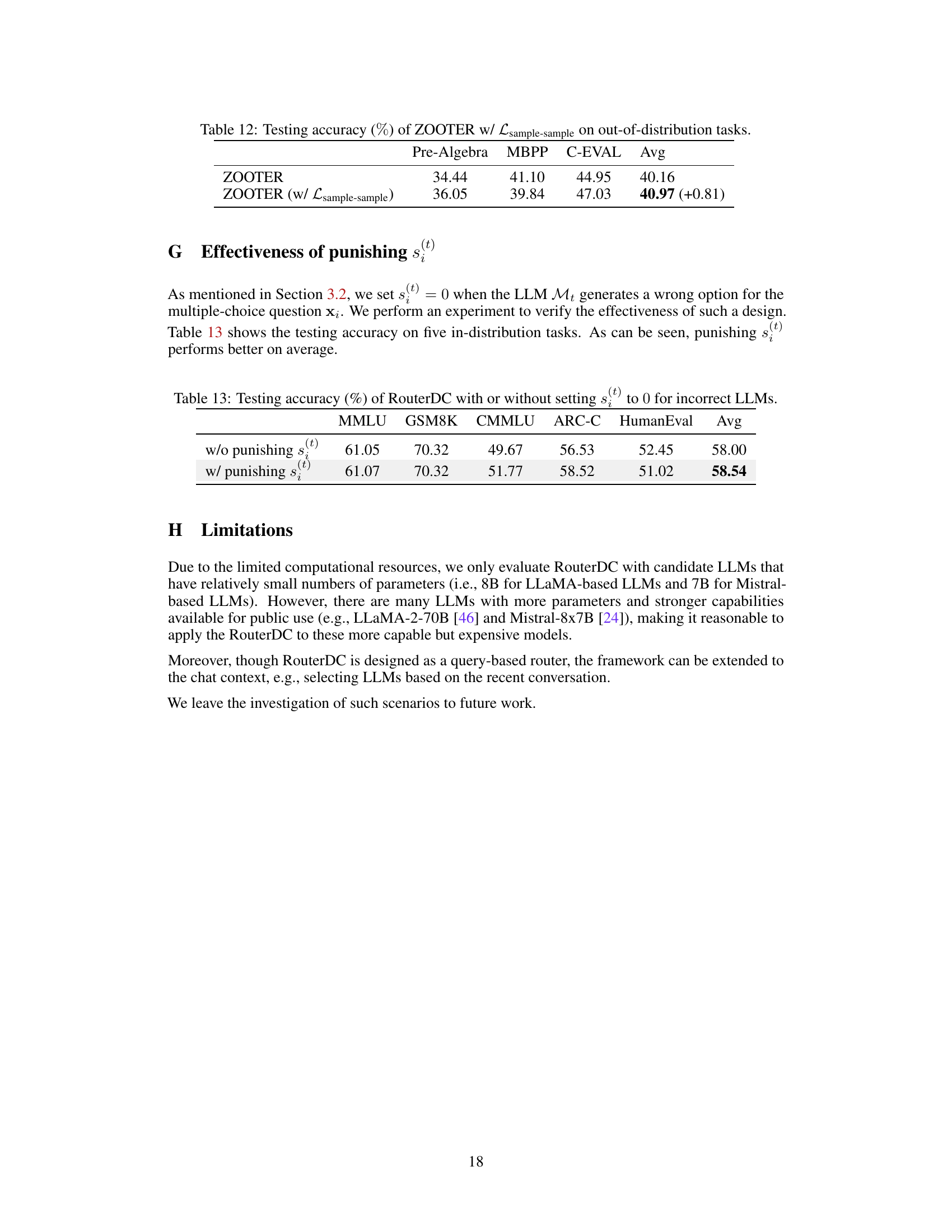

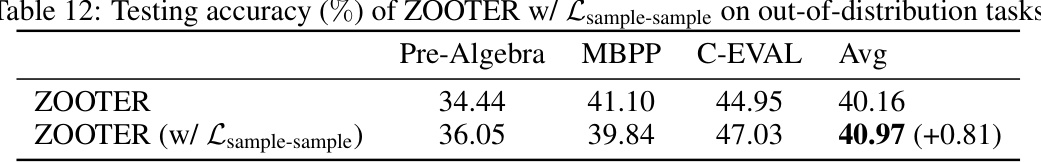

🔼 This table presents the testing accuracy achieved by the ZOOTER model, both with and without the inclusion of the sample-sample contrastive loss, across three out-of-distribution (OOD) tasks: Pre-Algebra, MBPP, and C-EVAL. The results highlight the performance improvement gained by incorporating the sample-sample loss, showcasing its effectiveness in enhancing the model’s generalization capabilities to unseen data distributions.

read the caption

Table 12: Testing accuracy (%) of ZOOTER w/ Lsample-sample on out-of-distribution tasks

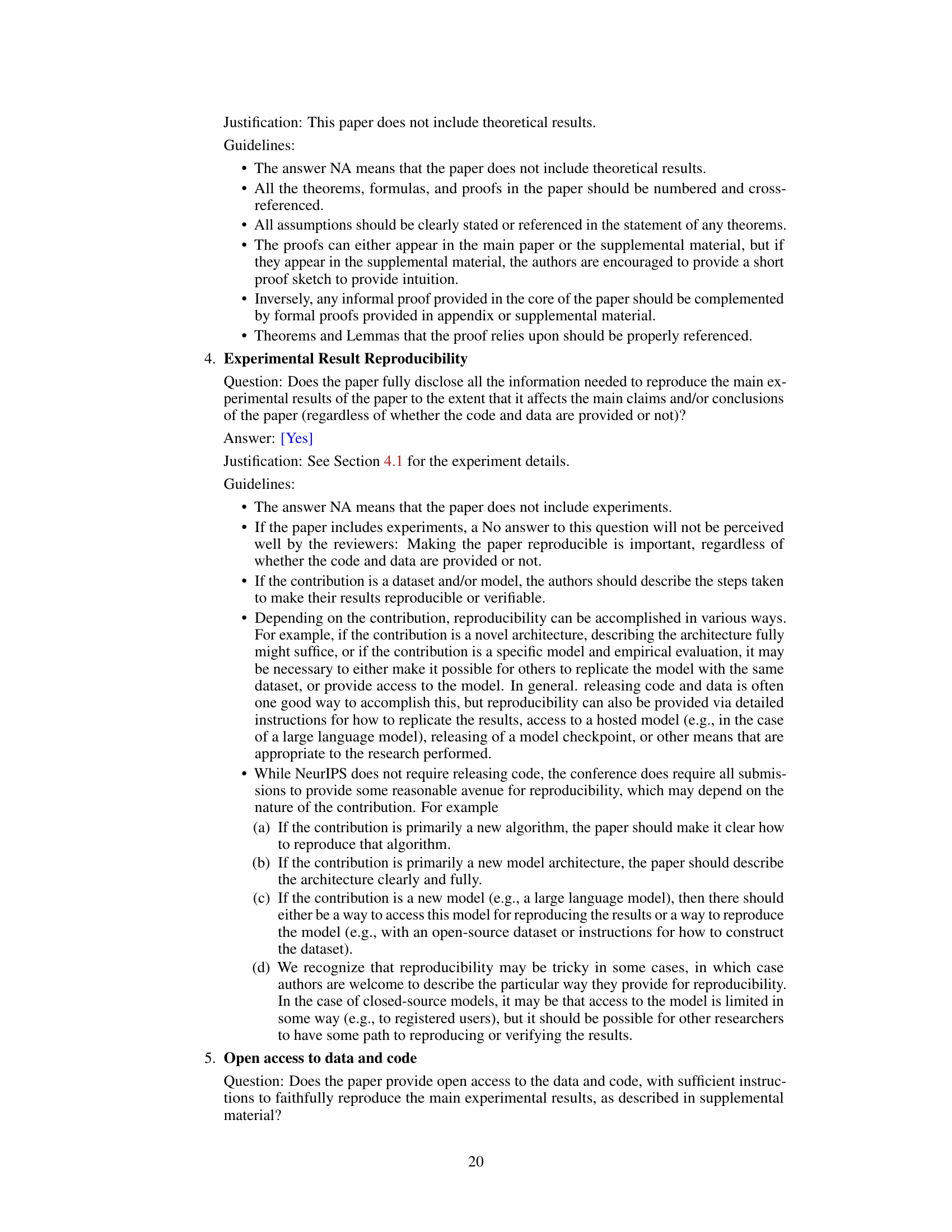

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment comparing the performance of RouterDC with and without a penalty for incorrect LLM outputs in multiple-choice questions. The experiment was conducted on five in-distribution tasks (MMLU, GSM8K, CMMLU, ARC-C, HumanEval) to evaluate the impact of the penalty on the overall accuracy. The ‘w/o punishing s(t)’ row shows the accuracy without applying the penalty, while the ‘w/ punishing s(t)’ row shows the accuracy when a penalty is applied. The results demonstrate the effect of the penalty on the model’s performance across different tasks.

read the caption

Table 13: Testing accuracy (%) of RouterDC with or without setting s(t) to 0 for incorrect LLMs.

Full paper#