TL;DR#

Many fairness-aware machine learning methods require sensitive demographic information, raising privacy concerns. Existing methods often prioritize the utility of the worst-off group, potentially sacrificing overall model performance. The lack of fairness-aware regression methods in literature also limits the applicability of many current approaches.

This paper introduces VFair, a method that achieves harmless Rawlsian fairness without using demographic information, focusing on minimizing the variance of training losses. VFair uses a dynamic update approach to ensure fairer solutions without harming overall utility, outperforming existing methods in regression tasks. The approach is particularly relevant for situations where privacy is paramount and demographic data is unavailable or unethical to collect.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on fairness in machine learning, especially those dealing with privacy concerns. It offers a novel approach to achieving fairness without relying on sensitive demographic data, a significant challenge in real-world applications. The proposed method, VFair, opens new avenues for research in fair algorithms, particularly for regression tasks, and encourages further investigation into dynamic update approaches for fairness.

Visual Insights#

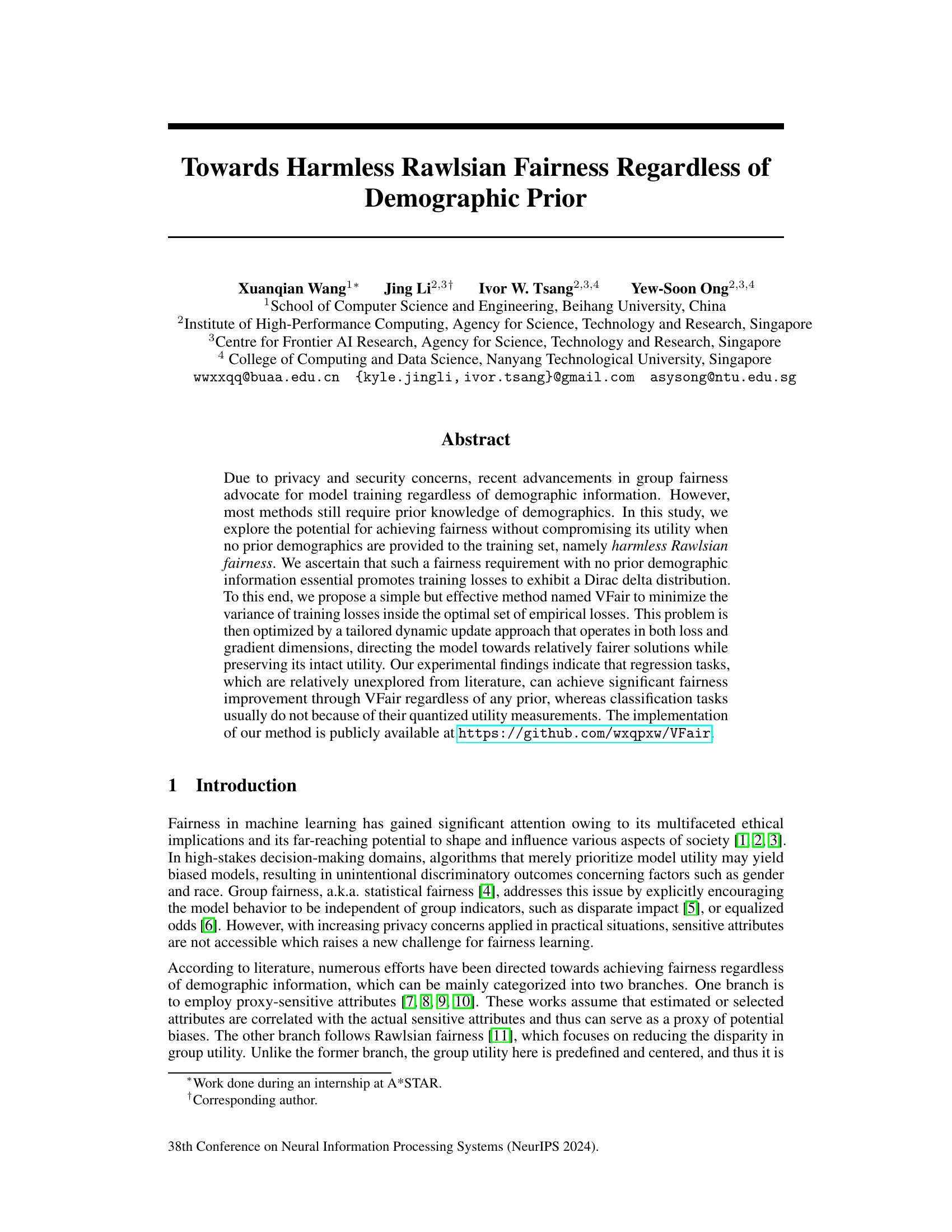

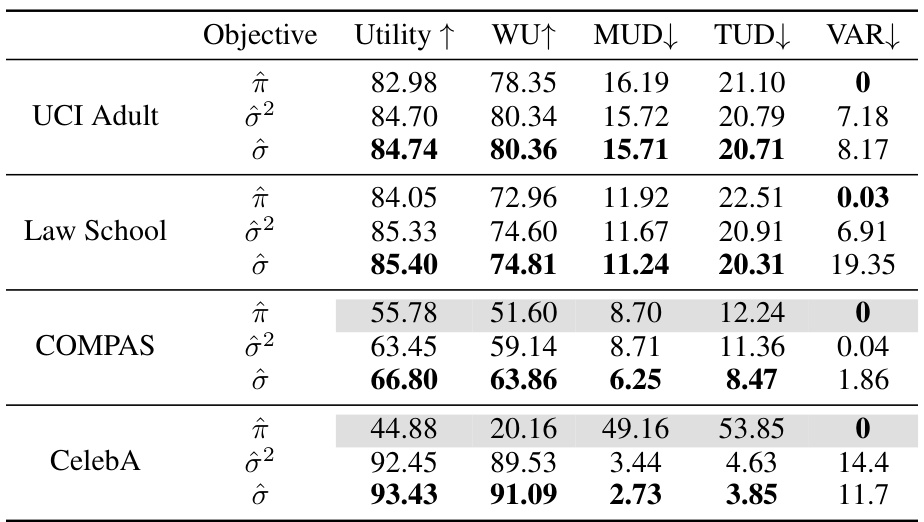

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the proposed method, VFair, which aims to minimize the variance of training losses. Panel (a) shows the probability density of losses for different methods. The ideal case is a Dirac delta distribution, where all losses are concentrated at zero. VFair aims to approximate this ideal distribution. Panel (b) displays the per-example losses sorted in ascending order for different methods. VFair shows a flattened loss curve compared to ERM (Empirical Risk Minimization) and worst-case fairness methods. This indicates that VFair achieves similar losses for each example, thus improving fairness. The figure visually represents the trade-off between fairness and utility, where VFair aims to balance the two by maintaining a low average loss while minimizing variance.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of our idea through different forms of loss curves.

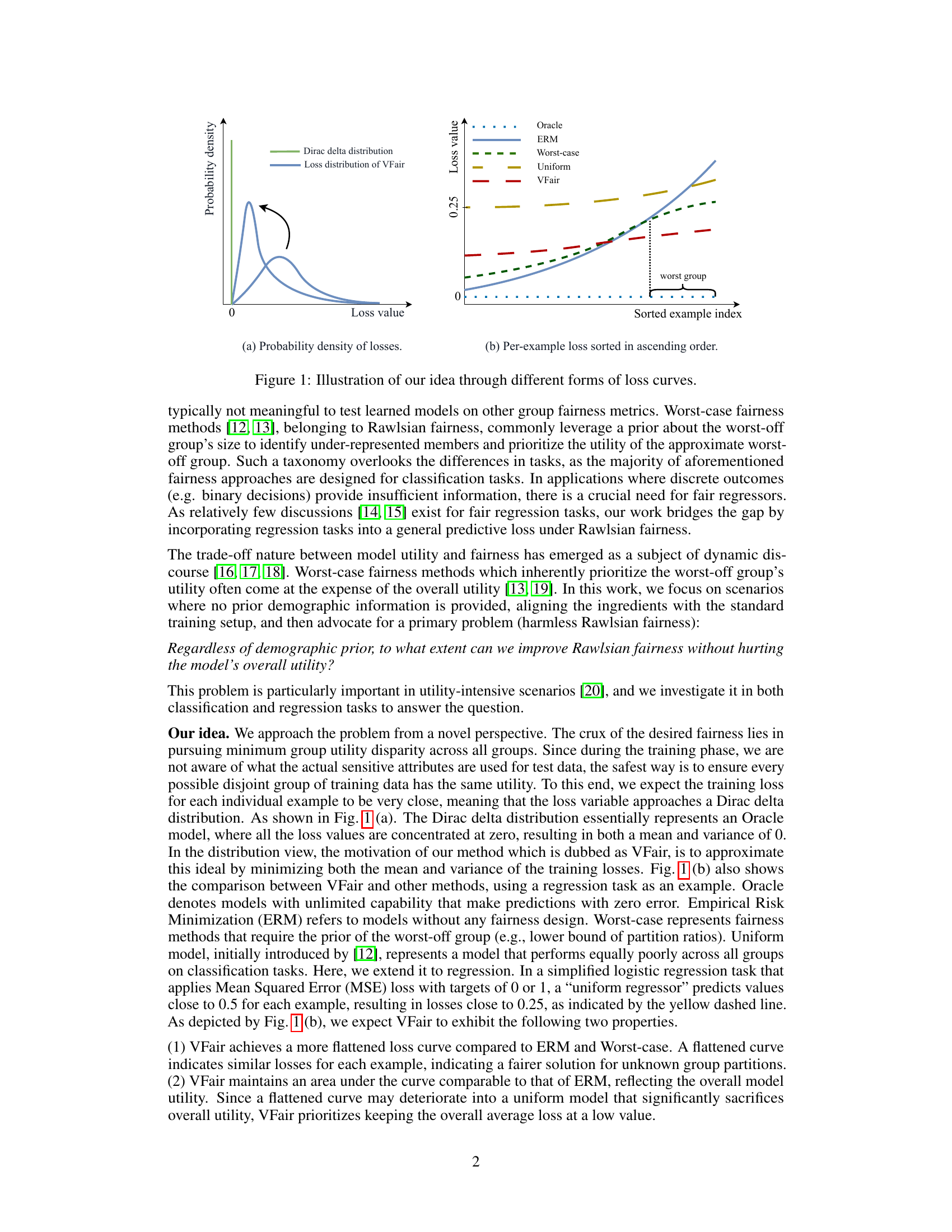

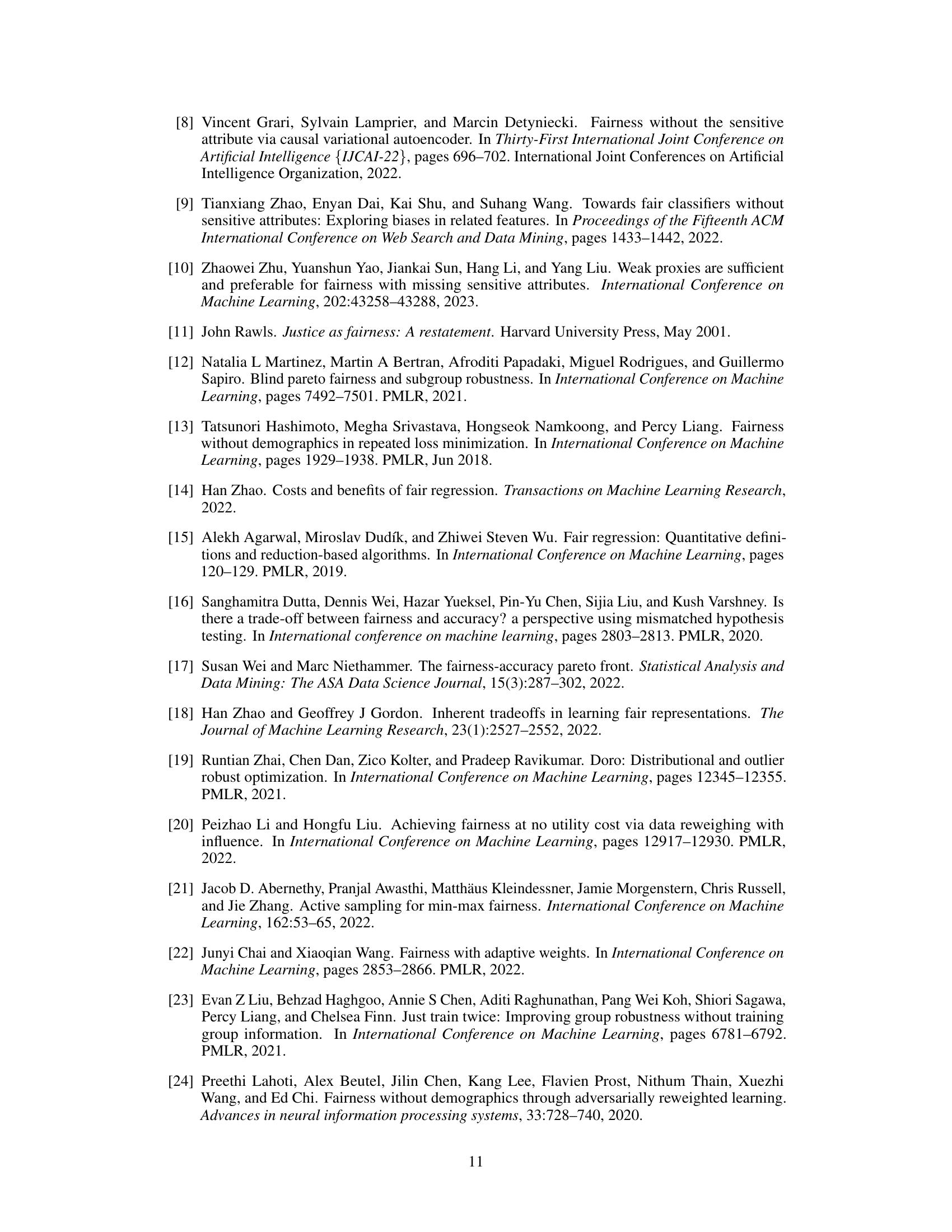

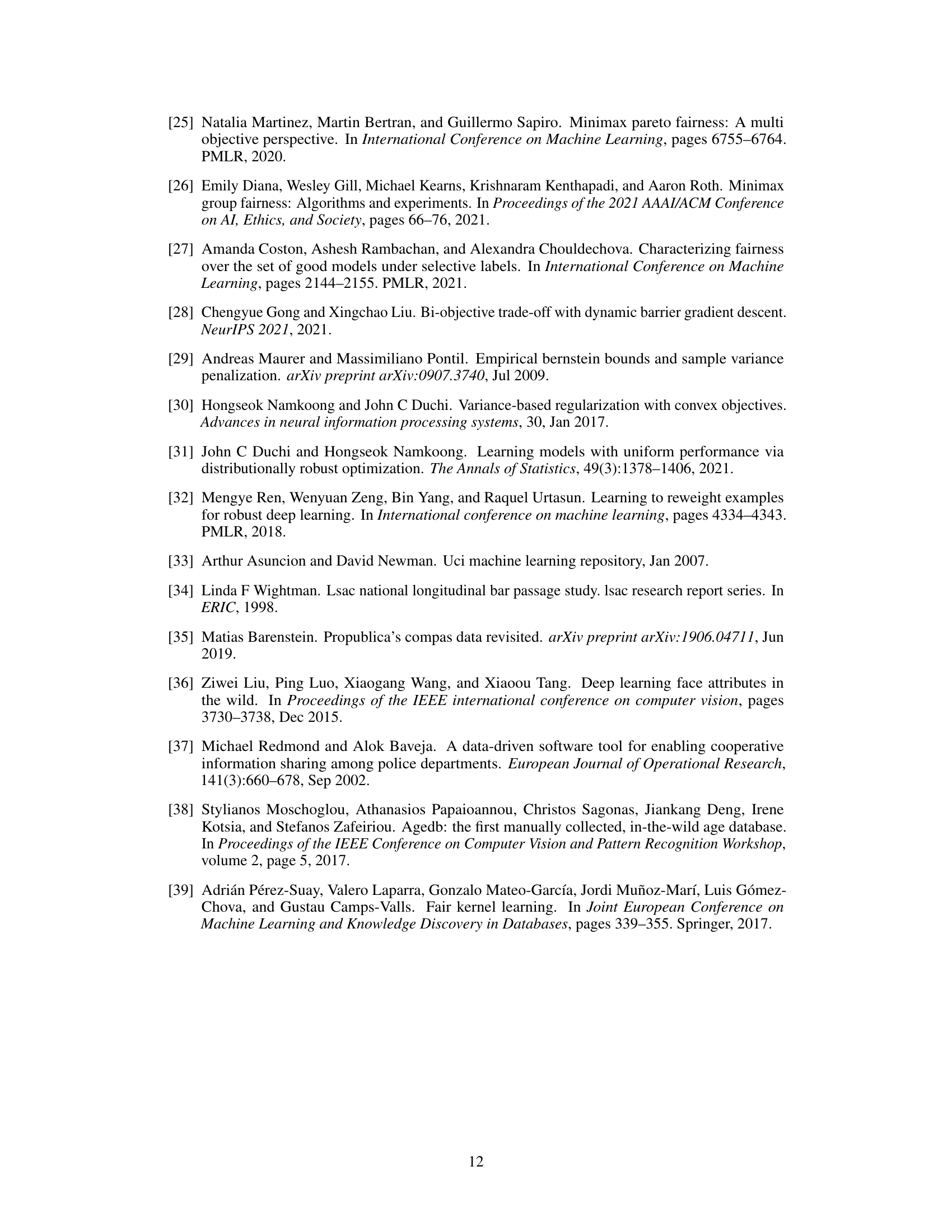

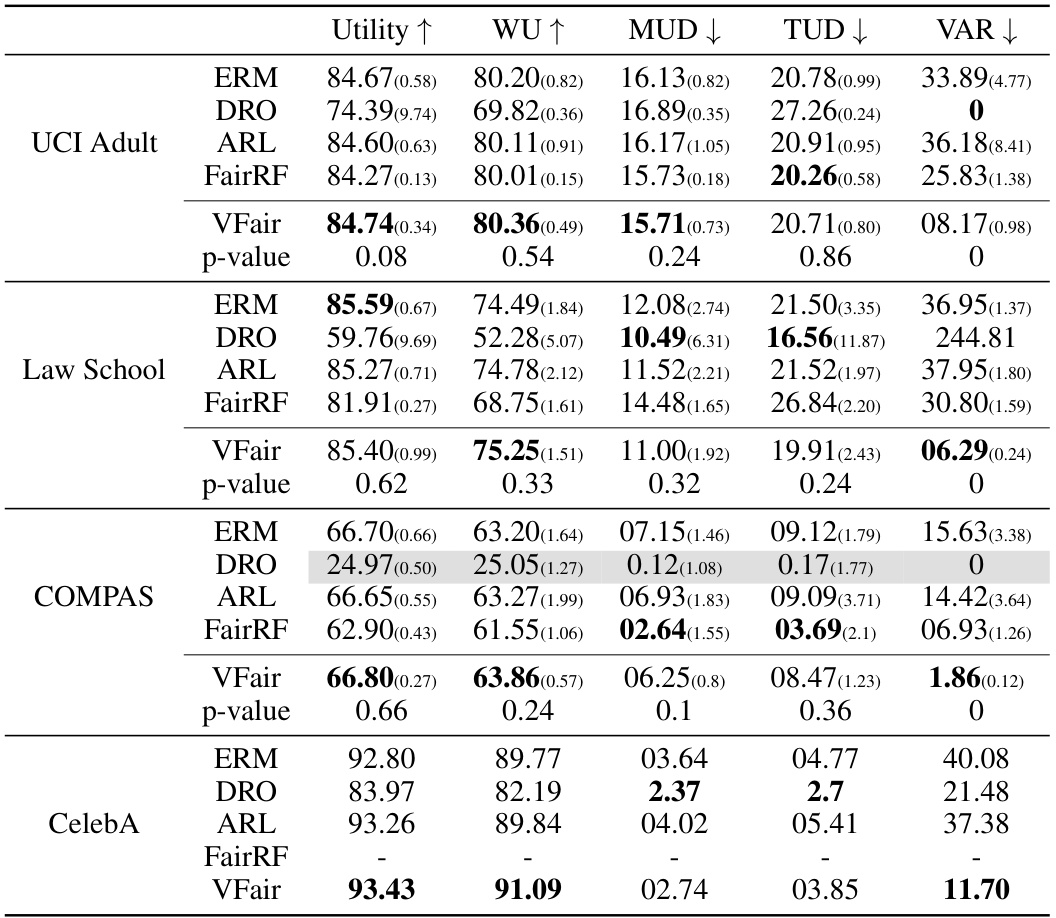

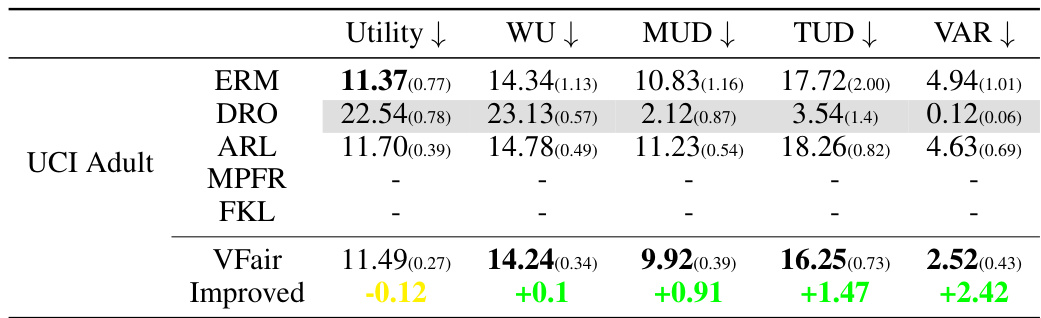

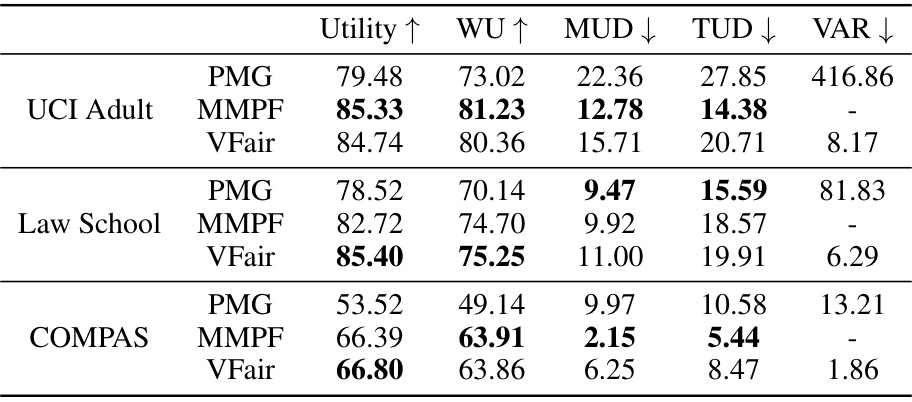

🔼 This table presents a comparison of regression results across five benchmark datasets using six different methods: ERM, DRO, ARL, BPF, MPFR, and VFair. For each dataset and method, the table shows the utility (MSE), worst-group utility (WU), maximum utility disparity (MUD), total utility disparity (TUD), and variance of prediction error (VAR). Lower values for Utility, WU, MUD, and TUD indicate better performance, while a lower VAR suggests better fairness.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

In-depth insights#

Harmless Fairness#

The concept of “Harmless Fairness” in machine learning is crucial because it addresses the ethical implications of biased algorithms. It aims to improve fairness without compromising the overall utility or performance of a model. This is a significant challenge, as many fairness-enhancing techniques prioritize fairness over utility, potentially leading to models that are less effective. Harmless fairness methods attempt to find a balance between these competing objectives. A key aspect is the consideration of demographic information; some approaches try to achieve fairness regardless of access to such data, relying instead on measures of overall model performance or loss distribution to guide the training process. The core challenge is to understand and manage the trade-off between fairness and utility, ensuring that fairness improvements don’t come at the expense of accurate predictions or decision-making. Different techniques and approaches, including both pre-processing and in-processing methods, are utilized to achieve this goal. The exploration of harmless fairness is vital for responsible and equitable development and deployment of machine learning systems. A key point is that the concept of ‘harm’ itself needs further clarity as different applications and contexts will have differing sensitivity to model performance drop-off. The concept is also critically important when handling sensitive data and privacy concerns.

Variance Minimization#

The concept of variance minimization within the context of fairness-aware machine learning is a powerful one. By minimizing the variance of prediction losses across different groups, the algorithm inherently reduces the disparity in model performance. This approach is particularly valuable when sensitive attributes are unavailable during training, as it focuses on achieving a more uniform distribution of prediction errors irrespective of group membership. This strategy elegantly sidesteps the need for explicit demographic information, a crucial aspect in privacy-preserving contexts. The effectiveness of this method rests on the assumption that a smaller variance implies a more equitable distribution of model utility. However, it’s crucial to note that solely minimizing variance could lead to a model with suboptimal overall performance. Therefore, a careful balance must be struck between minimizing variance and maintaining satisfactory prediction accuracy. A dynamic approach to adjust the balance between fairness (variance minimization) and utility during training might be needed to achieve optimal results, potentially through a tailored optimization method that integrates both objectives.

Dynamic Update#

The concept of a ‘Dynamic Update’ within the context of a fairness-focused machine learning model is crucial for achieving harmless Rawlsian fairness. It suggests an iterative process where model parameters are adjusted not just based on minimizing overall loss (utility), but also by actively managing the variance of losses across different data subgroups. This dynamic adjustment is essential because the identity of the subgroups (protected groups) is unknown during training. A static approach would risk either compromising utility by overly focusing on a single group or failing to effectively address fairness altogether. Therefore, the dynamic update method is a key innovation, enabling the algorithm to adapt to data characteristics and achieve an optimal balance between utility and fairness throughout training, approaching the ideal of near-zero loss variance for all groups.

Regression Focus#

A hypothetical ‘Regression Focus’ section in a fairness-focused machine learning paper would delve into the unique challenges and opportunities presented by regression tasks within the context of algorithmic fairness. It would likely highlight that regression problems, unlike classification, often deal with continuous outcomes, making the definition and measurement of fairness more nuanced. The section would discuss how existing fairness metrics, designed primarily for classification, might need adaptation or entirely new metrics developed for regression settings. Furthermore, it would likely explore the impact of different loss functions on fairness outcomes in regression and investigate whether techniques for achieving fairness in classification transfer effectively to the regression domain. A key aspect might involve addressing the trade-off between fairness and accuracy/utility, which is often more pronounced in regression due to the continuous nature of predictions. Finally, it would probably showcase empirical results demonstrating the efficacy of proposed methods on various regression benchmarks, comparing them against standard regression models and potentially other fairness-aware methods.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore the application of VFair to non-IID data, where the assumption of independently and identically distributed samples might not hold. Investigating the effectiveness of VFair on datasets with significant class imbalances or different group sizes is also crucial. Furthermore, a more in-depth analysis of the trade-off between utility and fairness is needed. While VFair aims for harmless fairness, quantifying and tuning this trade-off through a systematic process remains an open challenge. The dynamic update mechanism in VFair could benefit from further refinement to enhance stability and efficiency, and more efficient optimization strategies could be explored. Finally, extending VFair to other types of fairness criteria beyond Rawlsian fairness and exploring its effectiveness on other machine learning tasks, like reinforcement learning, should be considered to assess its broader applicability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates two scenarios during the gradient update process in the VFair algorithm. (a) shows a situation where the gradients of the primary and secondary objectives form an obtuse angle, resulting in a detrimental component in the primary objective’s direction. (b) depicts a scenario where the gradients form an acute angle, thus avoiding gradient conflicts. The figure helps explain how the dynamic coefficient λ is adjusted to ensure the update direction always benefits the primary objective (minimizing loss) without hindering fairness.

read the caption

Figure 2: Two situations when updating primary and secondary gradient simultaneously.

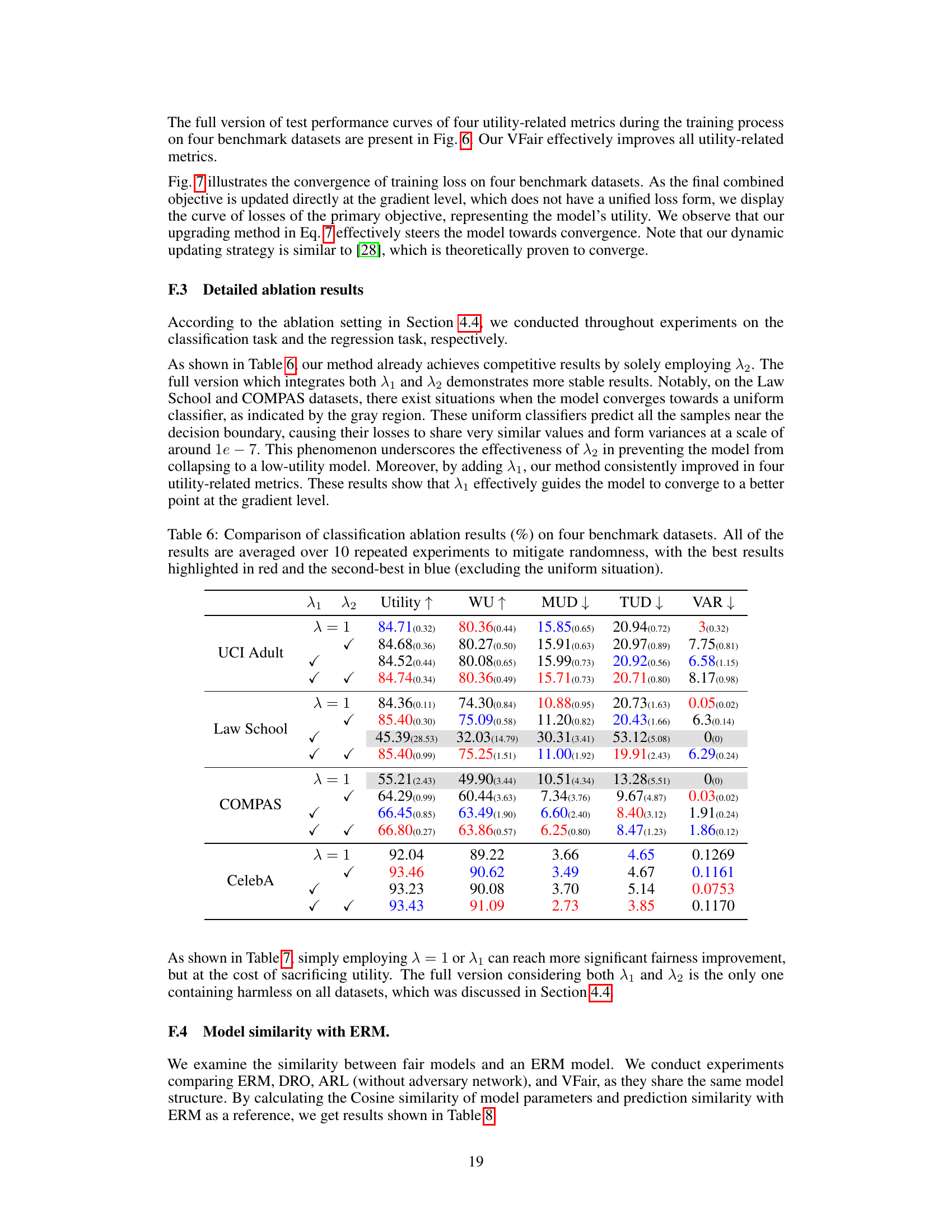

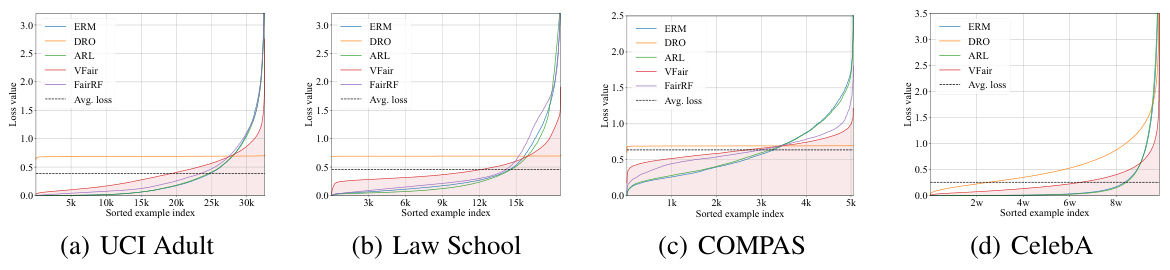

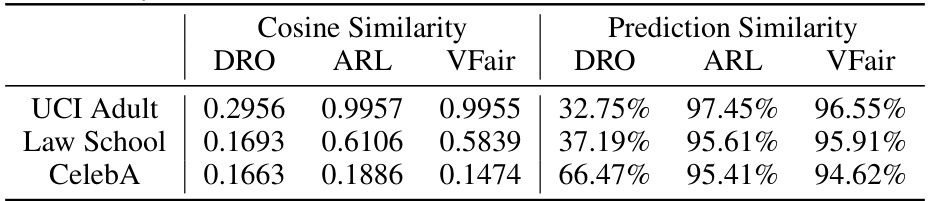

🔼 This figure shows the per-example losses for different fairness methods (ERM, DRO, ARL, VFair, FairRF) on a training dataset, sorted in ascending order. The x-axis represents the index of the training examples, and the y-axis represents the loss value. A vertical dashed cyan line separates the correctly classified examples (left) from incorrectly classified examples (right). A pink shaded area highlights the average loss for each method. The figure illustrates how the proposed method (VFair) achieves a more flattened loss curve compared to other methods, suggesting that VFair produces more consistent loss values across the training set. This is in line with the objective of minimizing the variance of the losses and achieving a better representation of the data across all groups.

read the caption

Figure 3: Per-example losses for all compared methods sorted in ascending order on train set.

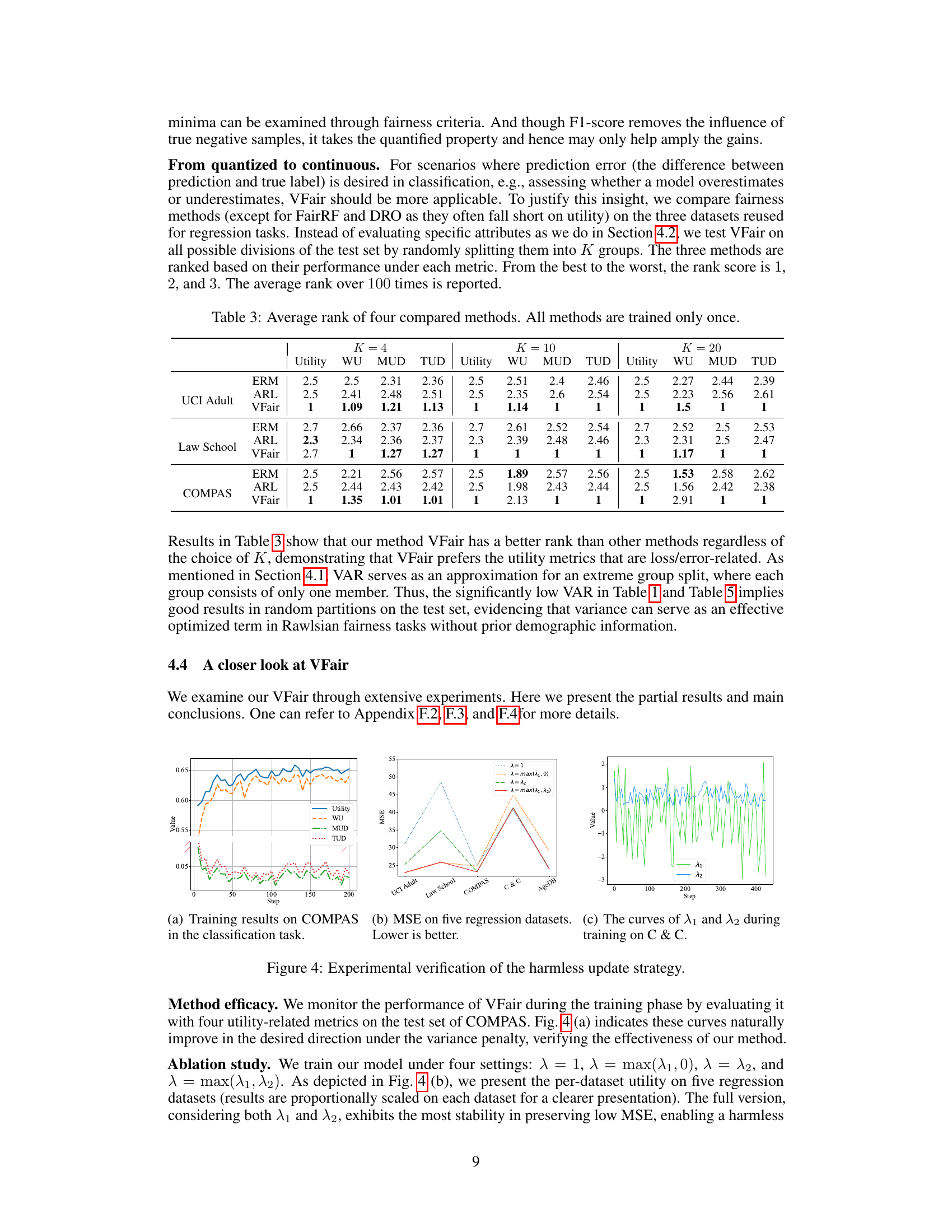

🔼 This figure presents experimental results to verify the effectiveness of the proposed harmless update strategy in VFair. Subfigure (a) shows training curves on the COMPAS dataset for various metrics (Utility, WU, MUD, TUD), demonstrating improvement across these metrics during training with the variance penalty. Subfigure (b) compares the impact of different λ strategies (λ = 1, λ = max(λ₁, 0), λ = λ₂, λ = max(λ₁, λ₂)) on MSE across five regression datasets, highlighting the stability of the full strategy (λ = max(λ₁, λ₂)). Subfigure (c) illustrates the dynamic adjustment of λ₁ and λ₂ during training on the C & C dataset.

read the caption

Figure 4: Experimental verification of the harmless update strategy.

🔼 The figure illustrates the concept of minimizing loss distribution variance to achieve fairness. Subfigure (a) shows the probability density of losses, with VFair approximating a Dirac delta distribution (ideal fairness). Subfigure (b) shows per-example loss sorted in ascending order, demonstrating VFair’s flattened loss curve compared to other methods (Oracle, ERM, Worst-case, Uniform), indicating similar losses across examples and suggesting fairer solutions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of our idea through different forms of loss curves.

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the proposed method, VFair, by showing different loss curve distributions. Panel (a) compares the probability density of losses for different approaches: Oracle (ideal, zero variance), ERM (standard training), Worst-case (prioritizing worst-off group), Uniform (evenly poor performance across groups), and VFair (the proposed method). VFair aims to minimize the variance of losses while maintaining low average loss, approximating a Dirac delta function. Panel (b) shows the per-example losses sorted in ascending order for each method, further illustrating the loss curve flattening achieved by VFair, showing relatively uniform loss across all examples.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of our idea through different forms of loss curves.

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of minimizing the variance of training losses to achieve fairness. (a) shows the probability density of losses for different methods. VFair aims to approximate a Dirac delta distribution, where all losses are concentrated near zero, indicating fairness. (b) shows per-example losses sorted in ascending order. VFair achieves a flattened loss curve, indicating similar losses for each example, which is a key characteristic of fairness. Other methods, such as ERM (Empirical Risk Minimization), Worst-case fairness, and a Uniform model, demonstrate more variance in their losses.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of our idea through different forms of loss curves.

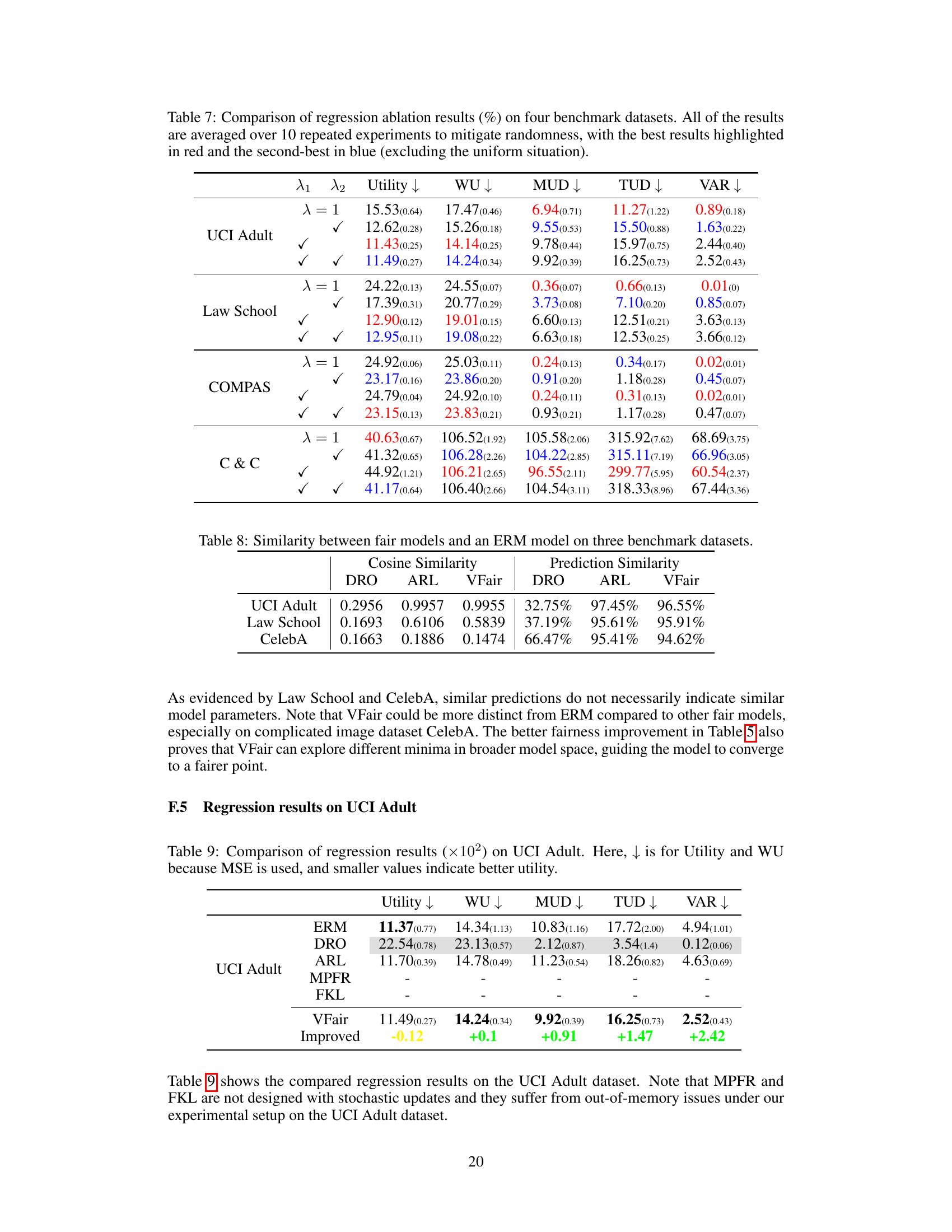

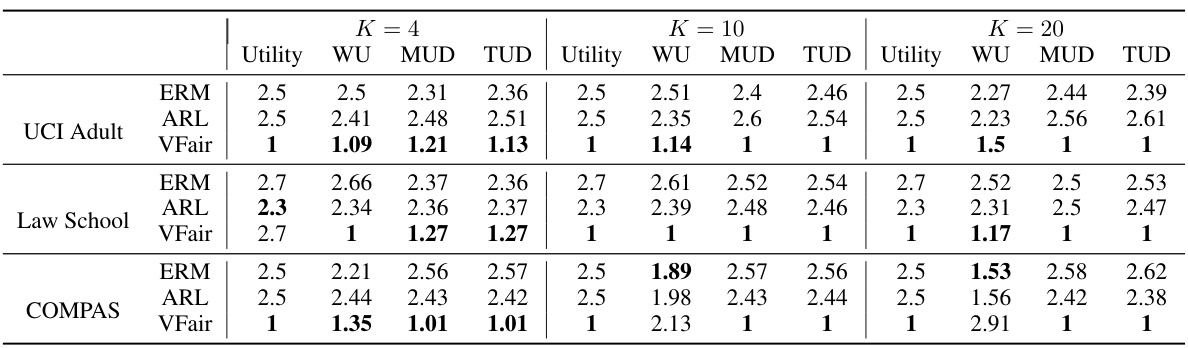

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the performance of VFair against several baseline methods on five regression datasets. The metrics used are Utility (MSE), Worst Group Utility (WU), Maximum Utility Disparity (MUD), Total Utility Disparity (TUD), and Variance of Prediction Error (VAR). Smaller values for Utility, WU, MUD, and TUD are better, indicating higher utility and fairness. The best result for each metric is shown in bold. The table also includes the improvement achieved by VFair compared to the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of regression results across five benchmark datasets using five different metrics: Utility (MSE), Worst Group Utility (WU), Maximum Utility Disparity (MUD), Total Utility Disparity (TUD), and Variance of Prediction Error (VAR). Lower values generally indicate better performance for Utility and WU, while lower values for MUD, TUD, and VAR represent better fairness. The best result for each metric across different methods (ERM, DRO, ARL, BPF, MPFR, FKL, and VFair) is highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table presents the results of regression experiments on five benchmark datasets. It compares the performance of the proposed VFair method against several baseline methods. The metrics evaluated include overall utility (lower is better, as MSE is used), worst-group utility (WU, lower is better), maximum utility disparity (MUD, lower is better), total utility disparity (TUD, lower is better), and variance of prediction errors (VAR, lower is better). The best performing method for each metric on each dataset is indicated in bold.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of regression results obtained using various methods on five benchmark datasets. The metrics used are Utility (MSE), Worst Group Utility (WU), Maximum Utility Disparity (MUD), Total Utility Disparity (TUD), and Variance of Prediction Error (VAR). Lower values for Utility and WU indicate better performance. The best result for each metric and dataset is highlighted in bold. The table includes the standard deviations of the results in parentheses.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of regression results across five benchmark datasets using five different evaluation metrics: Utility (MSE), Worst-group Utility (WU), Maximum Utility Disparity (MUD), Total Utility Disparity (TUD), and Variance of Prediction Error (VAR). The results are shown for several different methods including ERM (Empirical Risk Minimization), DRO (Distributionally Robust Optimization), ARL (Adversarial Re-weighting Learning), BPF (Blind Pareto Fairness), MPFR (Multi-group Pareto Fairness Regression), FKL (Fair Kernel Learning), and the proposed VFair method. The best result for each metric is highlighted in bold. Lower values of MSE and WU indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of regression results across five benchmark datasets using five metrics: Utility (MSE), Worst Group Utility (WU), Maximum Utility Disparity (MUD), Total Utility Disparity (TUD), and Variance of Prediction Error (VAR). The results are shown for seven different methods: ERM, DRO, ARL, BPF, MPFR, FKL, and VFair (the proposed method). Lower values for Utility and WU indicate better performance. The table highlights the best-performing method for each metric and dataset.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of regression results obtained using various methods on five benchmark datasets. The results are presented as the mean of 10 repeated experiments, with standard deviations in parentheses. The table compares the utility (measured by Mean Squared Error, MSE, lower is better), worst-group utility (WU, lower is better), maximum utility disparity (MUD, lower is better), total utility disparity (TUD, lower is better), and variance of prediction error (VAR, lower is better). The best-performing method for each metric is highlighted in bold. The table aids in understanding the relative performance of different fairness-aware and standard regression methods in terms of both utility and fairness.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table compares the performance of VFair and other regression methods across five datasets. The metrics used are Utility (MSE), Worst Group Utility (WU), Maximum Utility Disparity (MUD), Total Utility Disparity (TUD), and Variance of Prediction Error (VAR). Lower values generally indicate better performance for Utility and WU, while lower values for MUD, TUD, and VAR indicate better fairness. The best result for each metric in each dataset is bolded.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table compares the performance of various regression models on five benchmark datasets. The models are evaluated based on five metrics: Utility (MSE), Worst-group Utility (WU), Maximum Utility Disparity (MUD), Total Utility Disparity (TUD), and Variance of Prediction Error (VAR). Lower values for Utility, WU, MUD, and TUD indicate better performance. The table highlights the best-performing model for each metric in bold. It showcases the performance improvement achieved by the proposed method (VFair) compared to other methods. The (×102) indicates that values have been multiplied by 100.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table presents the results of regression experiments on five benchmark datasets. The performance of the proposed VFair method is compared against several baseline methods. The metrics used for evaluation include Utility (MSE), Worst Group Utility (WU), Maximum Utility Disparity (MUD), Total Utility Disparity (TUD), and Variance of Prediction Error (VAR). Lower values generally indicate better performance for Utility and WU, while lower values for MUD, TUD, and VAR indicate better fairness. The best result for each metric is shown in bold.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of regression results for five different benchmark datasets using five different methods: ERM, DRO, ARL, BPF, and VFair. For each dataset and method, the table shows the utility (MSE), worst-group utility (WU), maximum utility disparity (MUD), total utility disparity (TUD), and variance of prediction error (VAR). Lower values generally indicate better performance for Utility and WU, while lower values for MUD, TUD and VAR suggest better fairness. The best performing method for each metric is highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of regression results (×102) on five benchmark datasets with the best rank in bold. Here, ↓ is for Utility and WU because MSE is used, and smaller values indicate better utility.

Full paper#