TL;DR#

Contextual bandits are online learning problems where an agent sequentially interacts with an environment, aiming to maximize rewards by choosing actions informed by context and past experiences. Thompson Sampling (TS) is a popular approach, but its efficiency is often limited by using simple Gaussian priors that can’t represent complex relationships in data. This restricts exploration and the speed of learning.

This research addresses these limitations by proposing a novel algorithm that utilizes diffusion models as priors within Thompson sampling. The key innovation is an efficient method for approximate posterior sampling leveraging the Laplace approximation at each diffusion stage. The resulting algorithm is computationally efficient, asymptotically consistent (meaning it gets more accurate with more data), and shows superior performance across various experiments, overcoming limitations of previous approaches based on likelihood scores that tend to become unstable with large datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly improves Thompson sampling, a widely used algorithm in contextual bandits, by enabling the use of more expressive diffusion model priors. This addresses limitations of Gaussian priors, paving the way for better exploration and exploitation in online learning problems. The proposed method offers theoretical guarantees and performs well empirically, opening new avenues for research in bandit algorithms and generative models.

Visual Insights#

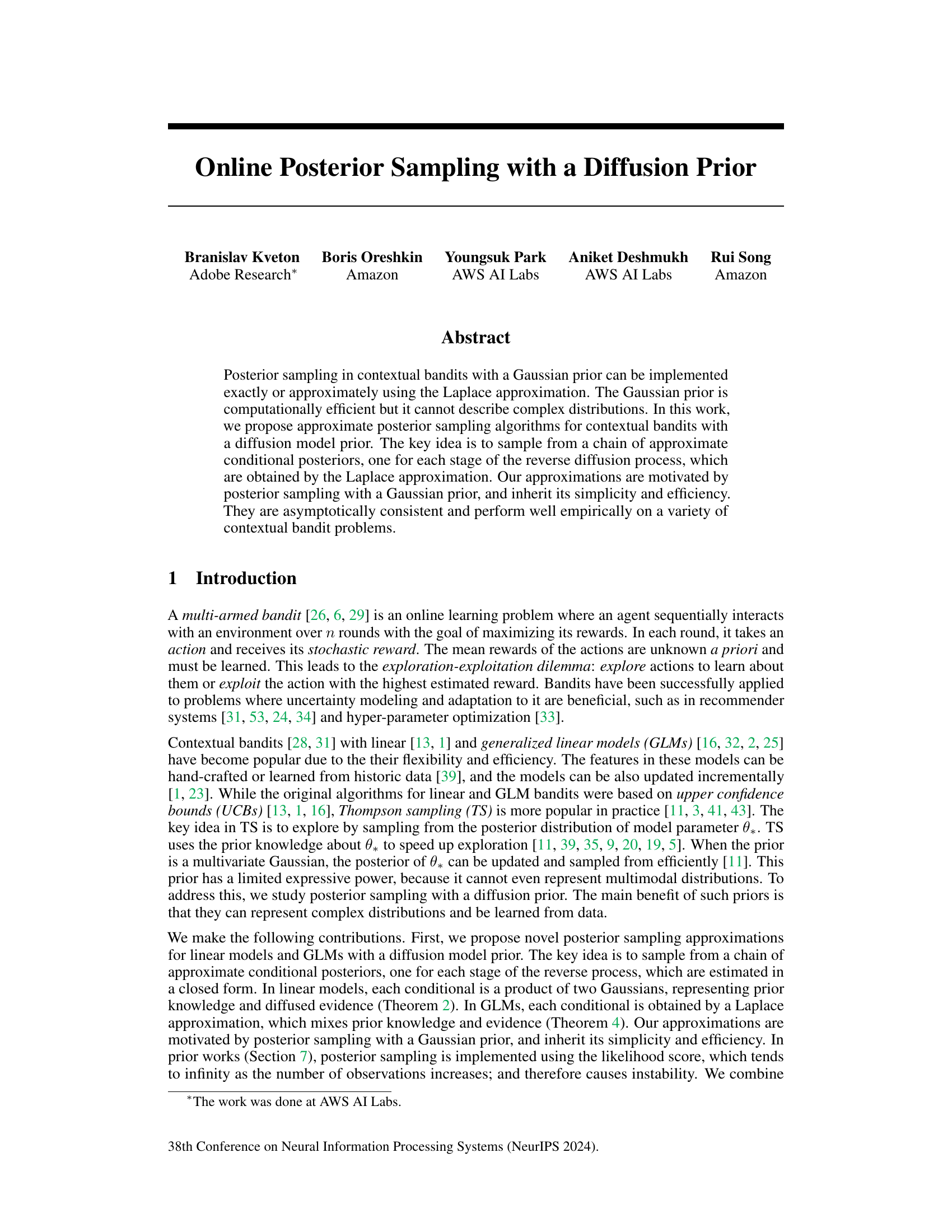

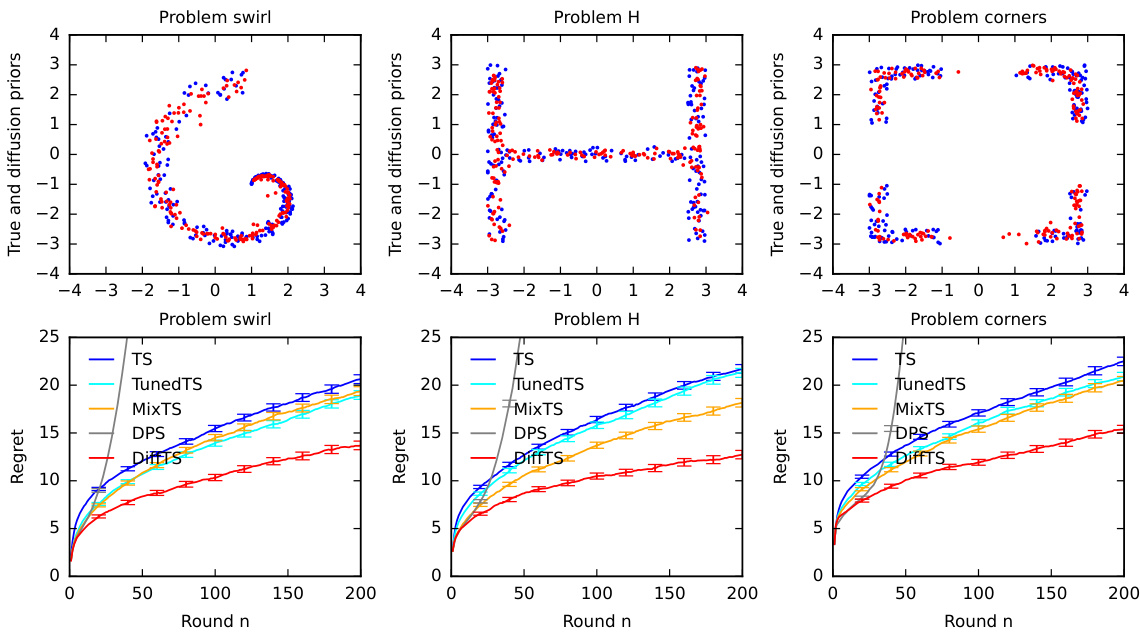

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the performance of the proposed DiffTS algorithm against several baseline algorithms on three different synthetic contextual bandit problems. The top row displays scatter plots visualizing samples drawn from the true prior distribution (blue dots) and the learned diffusion model prior (red dots) for each problem. The bottom row shows line graphs illustrating the cumulative regret (y-axis) over rounds (x-axis). The regret, a measure of the algorithm’s performance, is plotted for DiffTS and the baseline algorithms (TS, TunedTS, MixTS, DPS). This allows for a visual comparison of DiffTS’s performance against different approaches in terms of regret, illustrating its efficacy in handling various complex prior distributions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Evaluation of DiffTS on three synthetic problems. The first row shows samples from the true (blue) and diffusion model (red) priors. The second row shows the regret of DiffTS and the baselines as a function of round n.

🔼 This algorithm describes the contextual Thompson sampling method. In each round, a model parameter is sampled from the posterior distribution given the history of observations. Then, the action that maximizes the expected reward given the sampled parameter is selected, and a reward is observed. This process is repeated for n rounds.

read the caption

Algorithm 3 Contextual Thompson sampling.

In-depth insights#

Diffusion Prior Bandits#

Diffusion Prior Bandits represent a novel approach to contextual bandit problems, leveraging the power of diffusion models to represent complex, multimodal prior distributions over model parameters. This contrasts with traditional methods that often rely on simpler Gaussian priors, which have limited expressive power. By utilizing a diffusion model prior, the agent can effectively capture intricate relationships within the data, leading to improved exploration and exploitation strategies. The key challenge lies in efficiently sampling from the complex posterior distribution resulting from the combination of the diffusion prior and observed data. The authors address this by employing a Laplace approximation, a widely used technique for approximating posterior distributions. However, a crucial aspect is the asymptotic consistency of the developed approximation methods, ensuring that the approximations accurately reflect the true posterior as more data is gathered. The empirical evaluations demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm, highlighting its potential benefits in various applications. However, further investigation is warranted to thoroughly address computational costs associated with sampling from complex diffusion models, particularly in high-dimensional settings.

Laplace Posterior#

The Laplace approximation offers a computationally efficient method for approximating posterior distributions, particularly when dealing with complex models where exact computation is intractable. Its core idea is to approximate the posterior with a Gaussian distribution centered at the mode (maximum a posteriori estimate) of the true posterior. This simplification is achieved by using a second-order Taylor series expansion of the log-posterior around its mode. The resulting Gaussian approximation provides a convenient way to sample from the approximate posterior, facilitating Bayesian inference. However, the accuracy of the Laplace approximation depends heavily on the shape of the true posterior distribution. For highly non-Gaussian posteriors, the approximation can be inaccurate, potentially leading to misleading inferences. In the context of contextual bandits, where posterior distributions are dynamically updated based on observed data, the Laplace approximation’s efficiency is particularly beneficial. Yet, it’s crucial to carefully assess its validity, especially as the dimensionality of the problem increases. Alternative methods, such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), could yield more accurate results, but at significantly higher computational cost. Therefore, a careful trade-off between computational cost and accuracy is necessary when applying the Laplace approximation to real-world problems, including contextual bandit problems. The use of the Laplace approximation represents a balance between the need for efficient computation and the acceptable level of approximation error, particularly in high-dimensional spaces.

Asymptotic Consistency#

Asymptotic consistency, in the context of the provided research paper, signifies that the proposed posterior sampling approximations become increasingly accurate as the number of observations grows. This is a crucial theoretical property, ensuring the reliability of the method for real-world applications where data is abundant. The proof likely involves demonstrating that the approximated posterior distribution converges to the true posterior distribution in some appropriate metric (e.g., total variation distance) as the data size tends to infinity. This convergence is not instantaneous, but rather an asymptotic behavior. The key aspect of this analysis lies in showing the concentration of conditional posteriors around the true parameter value. The authors likely leverage the fact that with increasing data, the influence of the prior distribution diminishes and the evidence dominates, leading to the consistency of the approximation. Achieving this rigorous demonstration of asymptotic consistency significantly strengthens the paper’s claims, providing a theoretical foundation for the empirical findings presented.

Computational Cost#

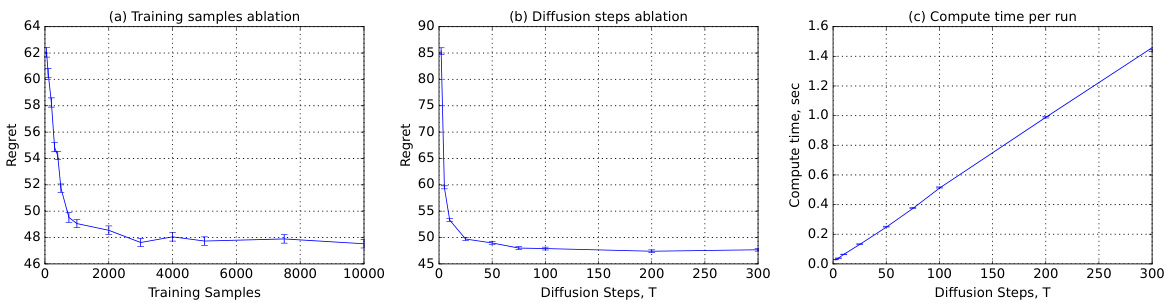

The computational cost of the proposed Laplace diffusion posterior sampling (LaplaceDPS) method is a crucial aspect of its practicality. The algorithm’s complexity scales linearly with the number of diffusion stages (T), significantly increasing computation time compared to traditional Gaussian-prior Thompson sampling. This linear scaling stems from the sequential nature of the reverse diffusion process, requiring separate computations for each stage. While efficient for relatively small T, the cost could become prohibitive for high-dimensional problems or when a large number of stages is needed for accurate posterior approximation. The authors acknowledge this limitation, highlighting the trade-off between computational cost and accuracy, and provide an ablation study to analyze this trade-off empirically. Ultimately, the scalability of LaplaceDPS hinges on managing this cost-accuracy balance through careful selection of the number of diffusion stages, informed by the problem’s specifics and computational resources available.

Future Research#

The authors acknowledge the limitations of their current approximations, particularly the computational cost which scales linearly with the number of diffusion stages. Future work should focus on developing more efficient posterior approximations, perhaps by exploring alternative sampling methods or improved variance reduction techniques. Addressing the error introduced by the approximation of clean samples with scaled diffused samples is also crucial. A rigorous regret analysis is needed to better understand the theoretical guarantees of their algorithm. Extending the framework beyond GLMs to handle a broader range of observation models is another important direction, potentially through more sophisticated likelihood approximations or alternative methods. Finally, empirical evaluation on a wider range of benchmark datasets is necessary to fully establish the generality and robustness of the proposed approach. Investigating the impact of the hyperparameters, such as the number of diffusion stages and training samples, on the performance warrants further study.

More visual insights#

More on figures

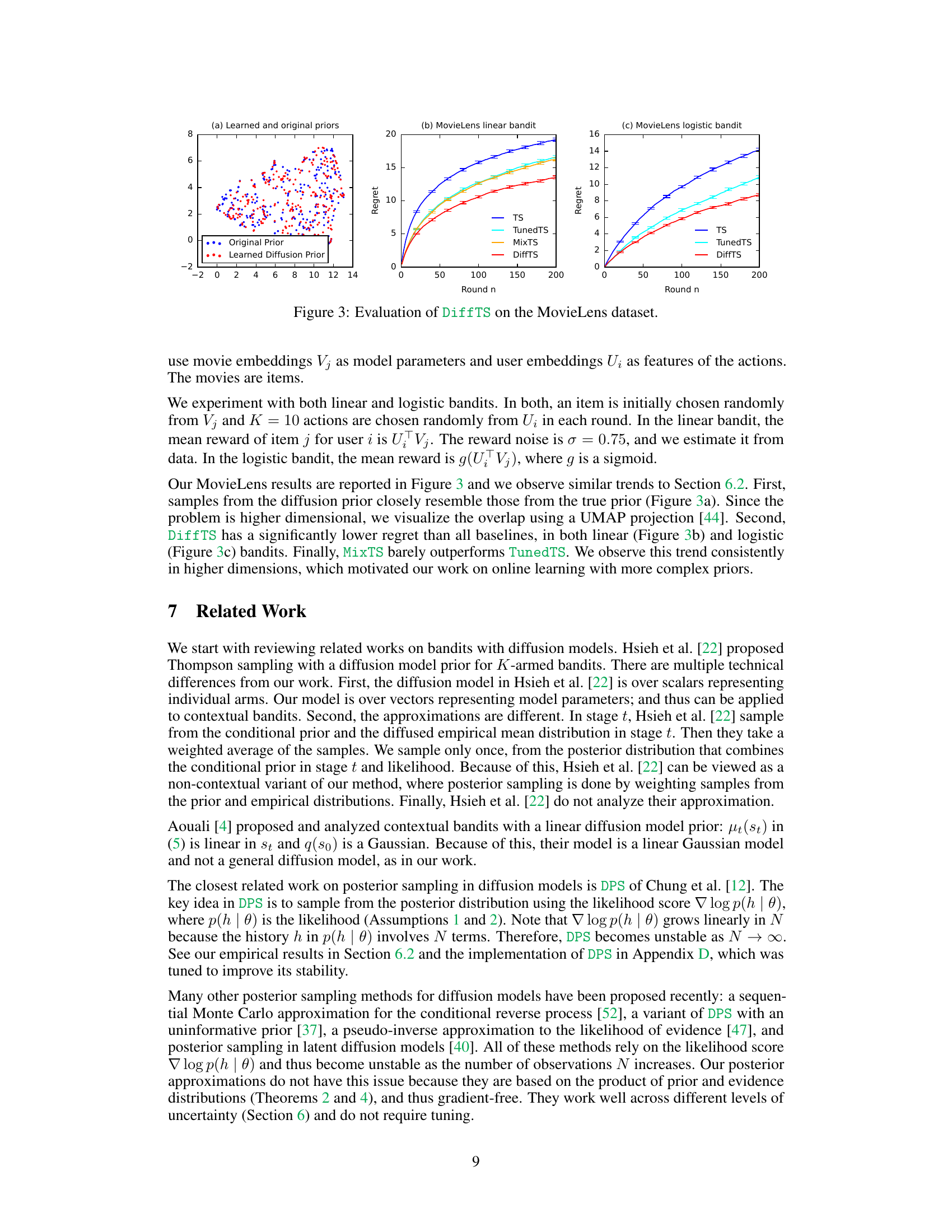

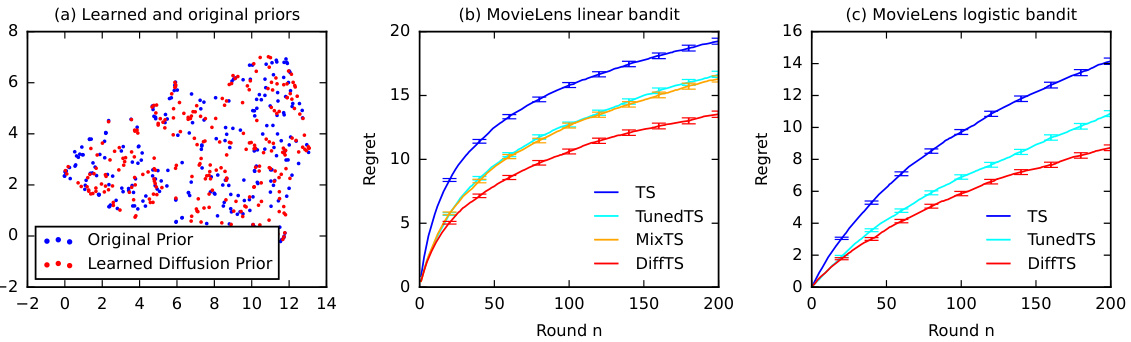

🔼 This figure shows the results of the MovieLens experiment, comparing DiffTS with other Thompson sampling baselines (TS, TunedTS, MixTS, and DPS). Subfigure (a) visualizes the learned diffusion prior against the original prior, showing their similarity. Subfigures (b) and (c) present the regret curves for linear and logistic bandit settings, respectively. DiffTS consistently outperforms the baselines, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling high-dimensional data.

read the caption

Figure 3: Evaluation of DiffTS on the MovieLens dataset.

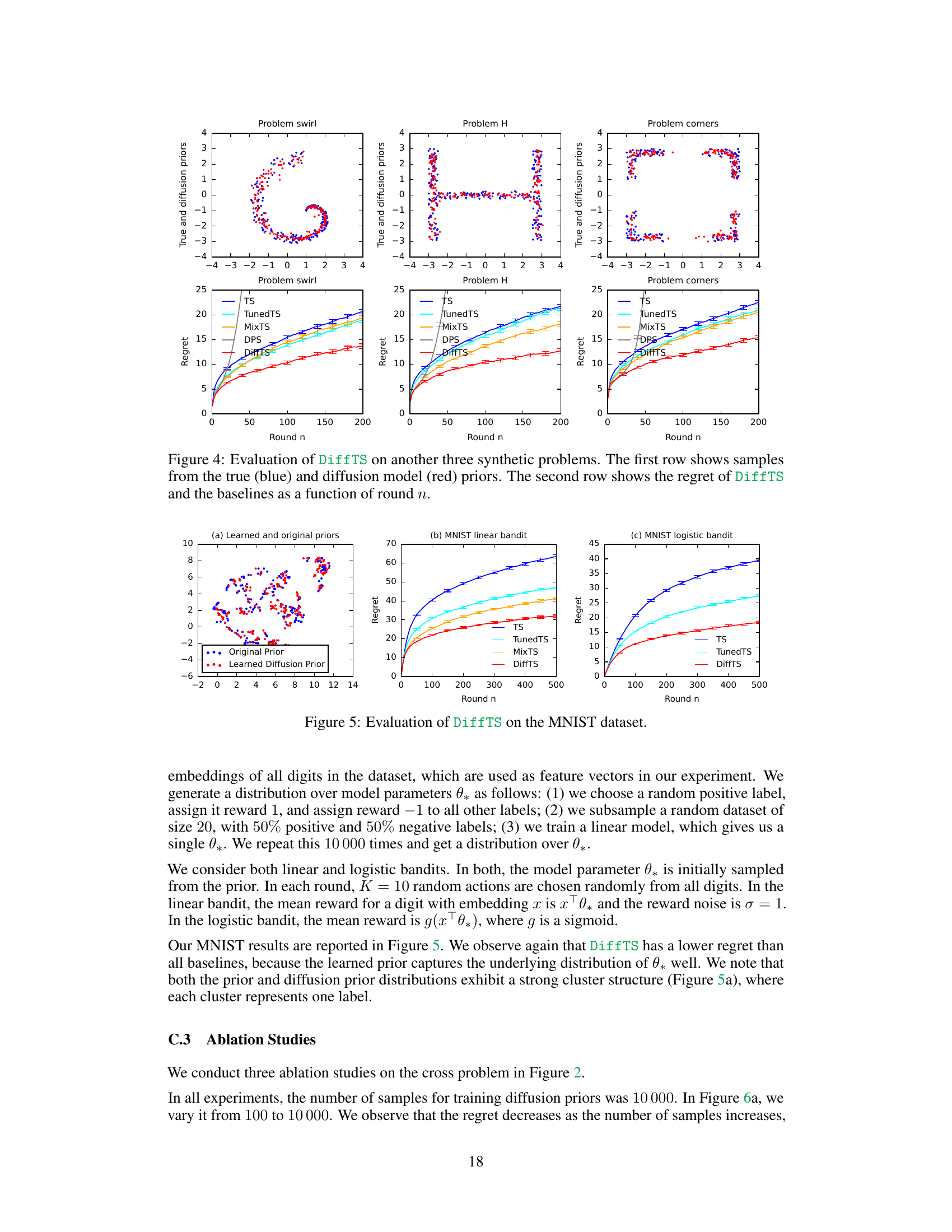

🔼 This figure presents the results of the DiffTS algorithm on three different synthetic problems, each showing a unique prior distribution. The top row displays the true and learned diffusion model priors visually, illustrating the similarity between the two. The bottom row presents a graph comparing the cumulative regret of DiffTS against several baseline algorithms (TS, TunedTS, MixTS, and DPS) over a range of rounds (n). This allows for a direct comparison of DiffTS’s performance against established methods in handling different prior distributions.

read the caption

Figure 4: Evaluation of DiffTS on another three synthetic problems. The first row shows samples from the true (blue) and diffusion model (red) priors. The second row shows the regret of DiffTS and the baselines as a function of round n.

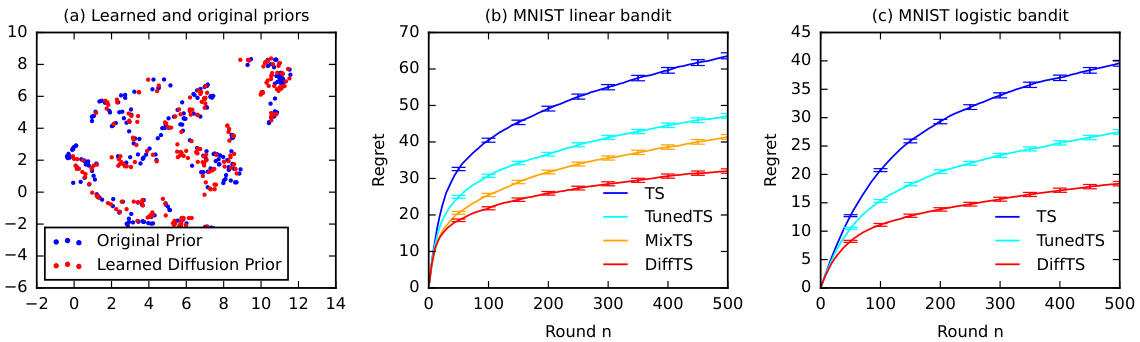

🔼 The figure shows the results of an experiment on the MNIST dataset, comparing the performance of DiffTS against other methods. Subfigure (a) displays a visualization comparing the learned diffusion prior and the original prior using UMAP projection. Subfigures (b) and (c) show the regret curves for linear and logistic bandit settings, respectively, comparing DiffTS to TS, TunedTS, MixTS baselines. DiffTS demonstrates lower regret than the others.

read the caption

Figure 5: Evaluation of DiffTS on the MNIST dataset.

🔼 This figure presents an ablation study evaluating the performance of the DiffTS algorithm across three different aspects: the number of training samples used for the diffusion prior, the number of diffusion stages (T), and the computational time required per run. The results are visualized in three separate subplots. (a) shows how the regret changes with different training sample sizes; (b) illustrates the relationship between regret and the number of diffusion steps; and (c) displays the computational cost (time) as a function of the number of diffusion steps.

read the caption

Figure 6: An ablation study of DiffTS on the cross problem: (a) regret with a varying number of samples for training the diffusion prior, (b) regret with a varying number of diffusion stages T, and (c) computation time with a varying number of diffusion stages T.

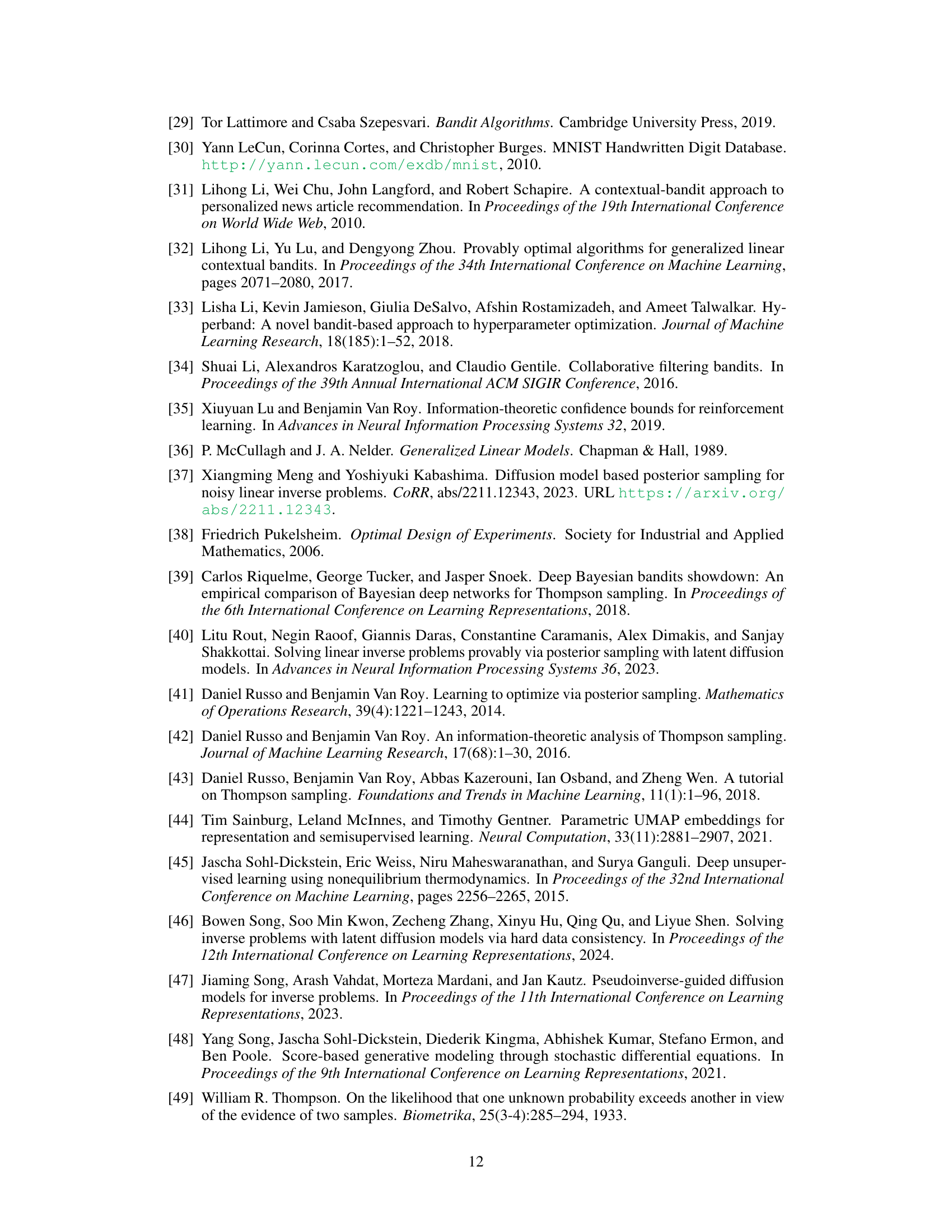

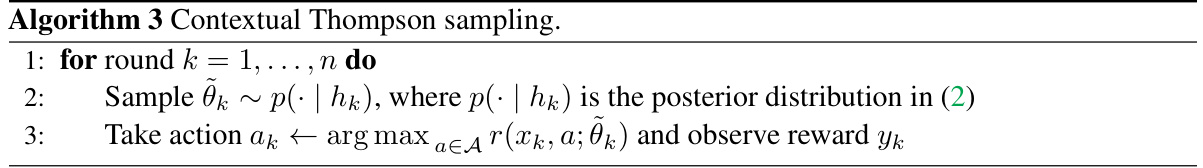

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of different Thompson Sampling algorithms on three synthetic bandit problems with Gaussian mixture priors. The top row visualizes samples from the true and learned diffusion priors for each problem, showcasing the similarity between them. The bottom row displays the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) between the posterior distributions obtained using various methods (including DiffTS, the proposed approach) and the true posterior distribution, plotted as a function of the sample size (n). This demonstrates the accuracy and stability of the proposed method, showing that its posterior approximation converges to the true posterior as the sample size increases, outperforming other methods in terms of accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 7: Evaluation on Gaussian mixture variants of the synthetic problems in Figure 2. The first row shows samples from the true (blue) and diffusion model (red) priors. The second row shows the earth mover's distance of DiffTS and baseline posterior distributions from the true posterior as a function of sample size n.

Full paper#