TL;DR#

Current LLM ranking methods often rely on pairwise comparisons, frequently obtained from another strong LLM instead of humans. This practice is problematic due to potential mismatches between LLM and human preferences, creating uncertain and unreliable rankings. This lack of uncertainty quantification hinders reliable model comparisons.

This research introduces a novel statistical framework that mitigates this problem. By combining a small set of human pairwise comparisons with a larger LLM-generated dataset, it constructs rank-sets representing possible LLM ranking positions. These sets probabilistically cover the true ranking consistent with human preferences, allowing researchers to quantify the uncertainty and improve the reliability of LLM rankings. Empirical experiments validate the effectiveness of the approach, highlighting discrepancies between human and strong LLM preferences.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on large language model (LLM) ranking and evaluation. It introduces a novel statistical framework to quantify the uncertainty inherent in LLM rankings derived from pairwise comparisons, addressing a critical limitation in current practice. This framework is particularly relevant given the increasing reliance on LLMs to perform these comparisons, which may introduce bias. The findings challenge existing assumptions and offer valuable insights for constructing more reliable and robust LLM rankings, influencing both methodological developments and practical applications.

Visual Insights#

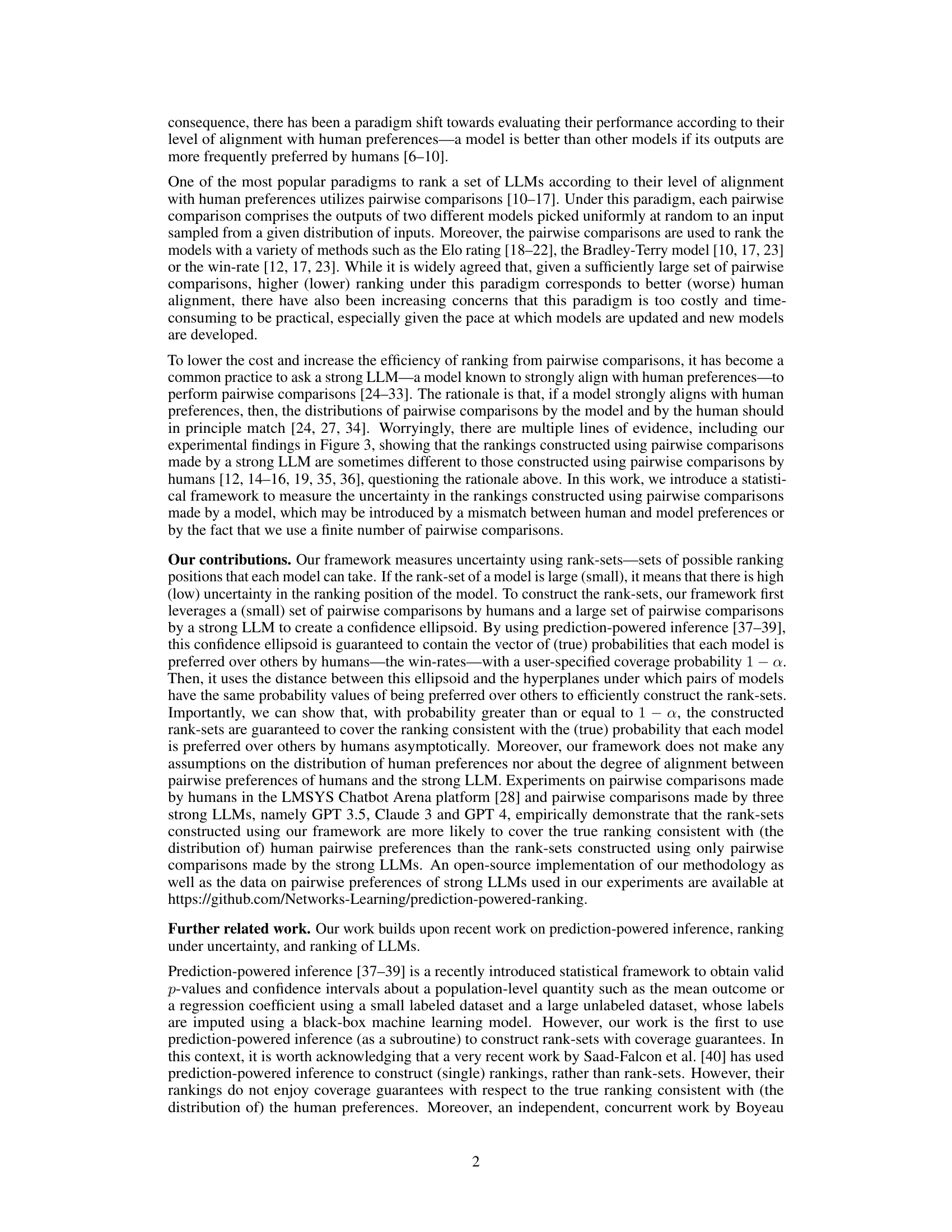

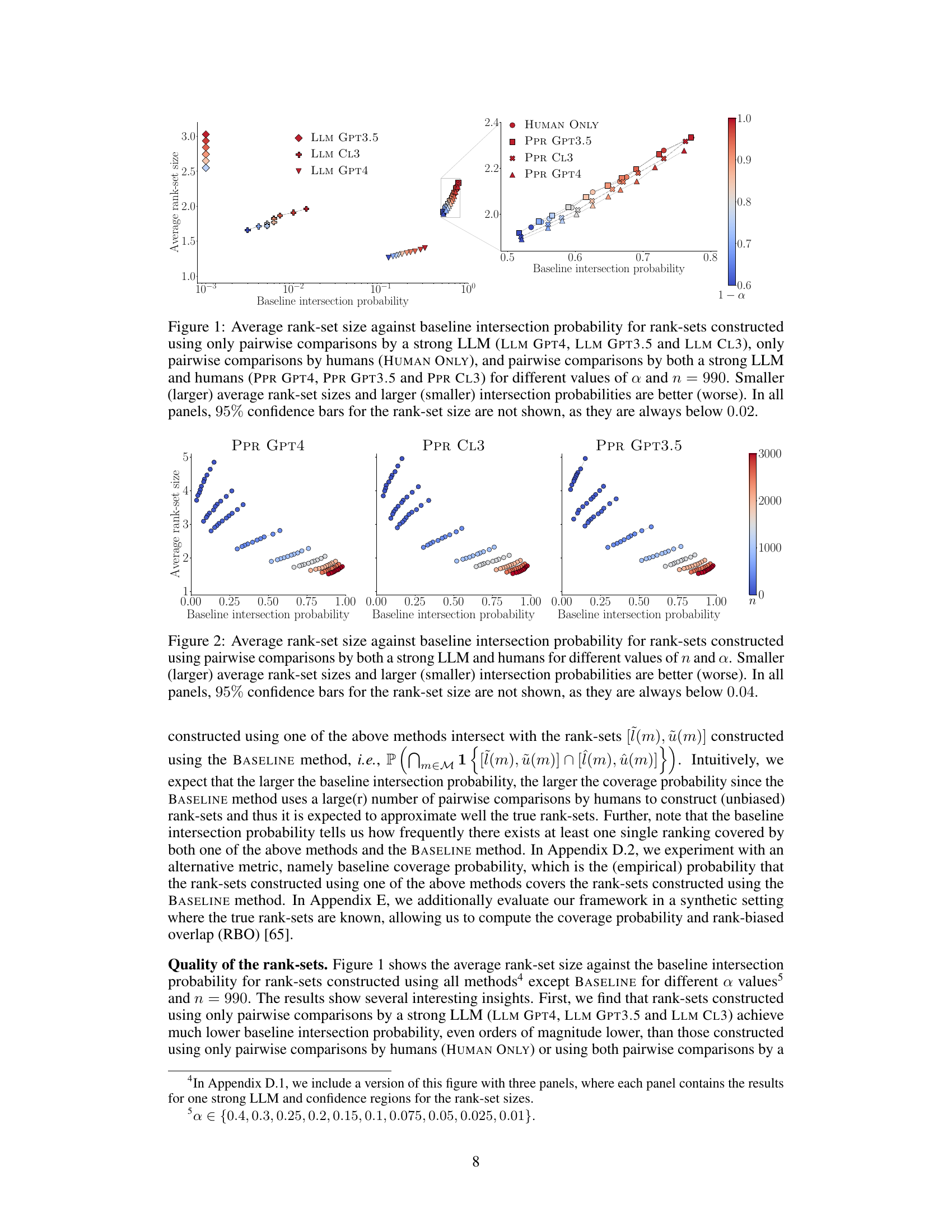

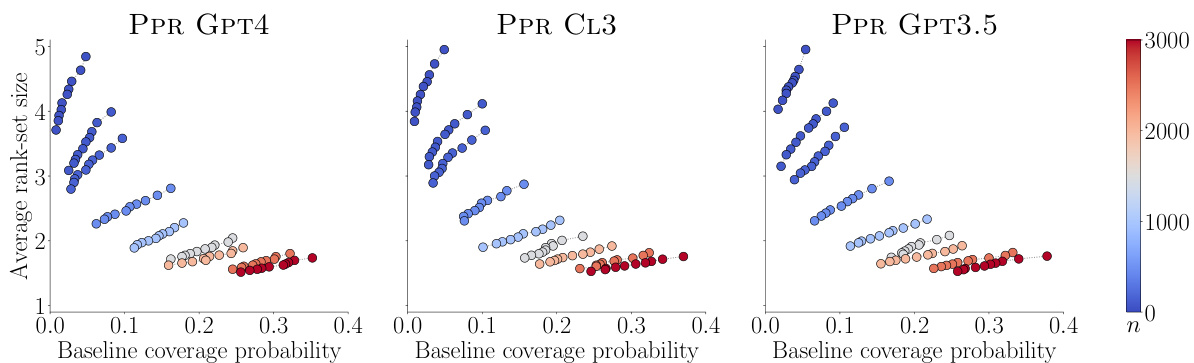

🔼 This figure compares different methods for constructing rank-sets of LLMs. The x-axis shows the baseline intersection probability (how often the rank-sets constructed by a method overlap with those constructed using human judgments alone). The y-axis represents the average size of the constructed rank-sets. Methods using only strong LLMs show lower intersection probability and larger rank-sets (more uncertainty) than methods combining strong LLMs and human judgments. The results suggest that incorporating human input, even a small amount, significantly improves the accuracy and reliability of LLM ranking.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

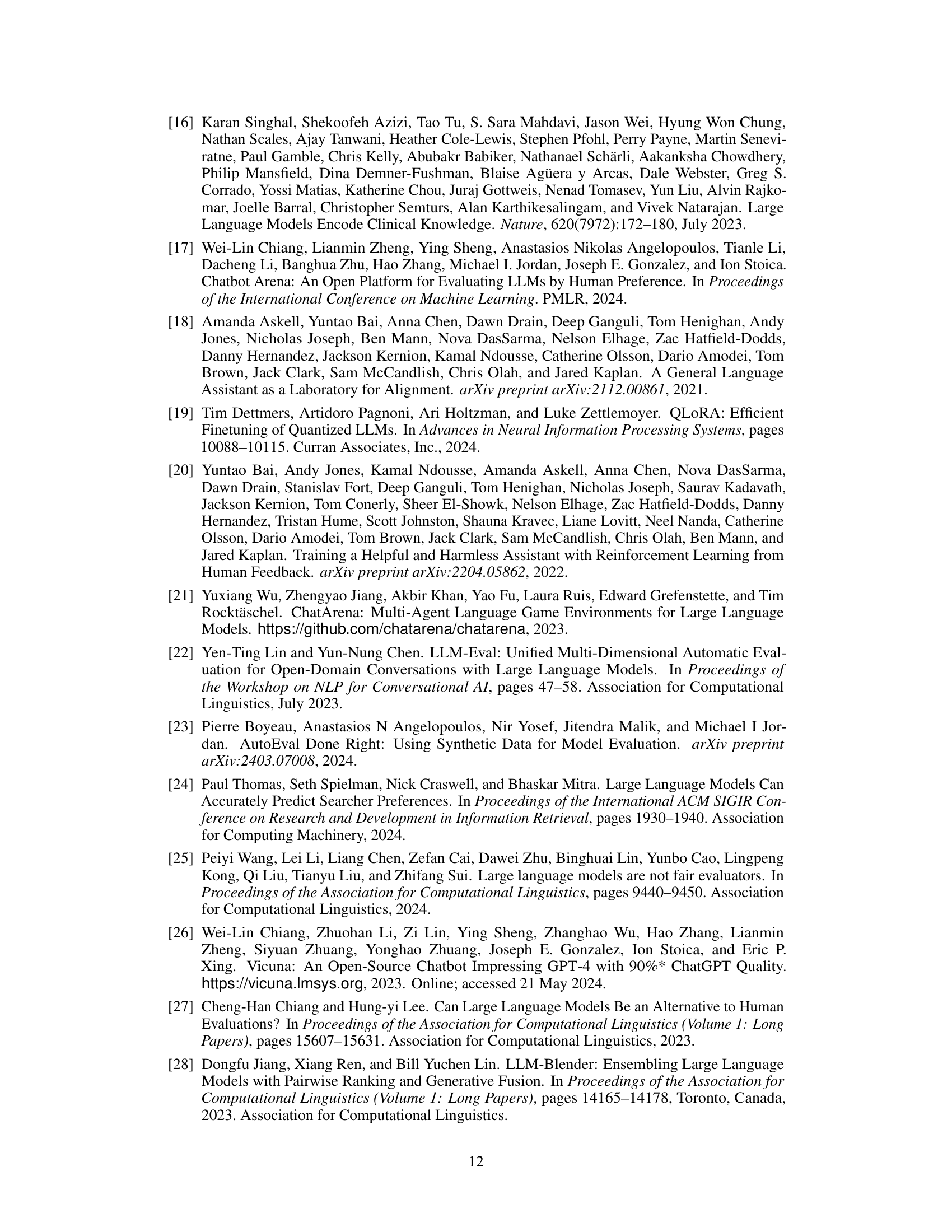

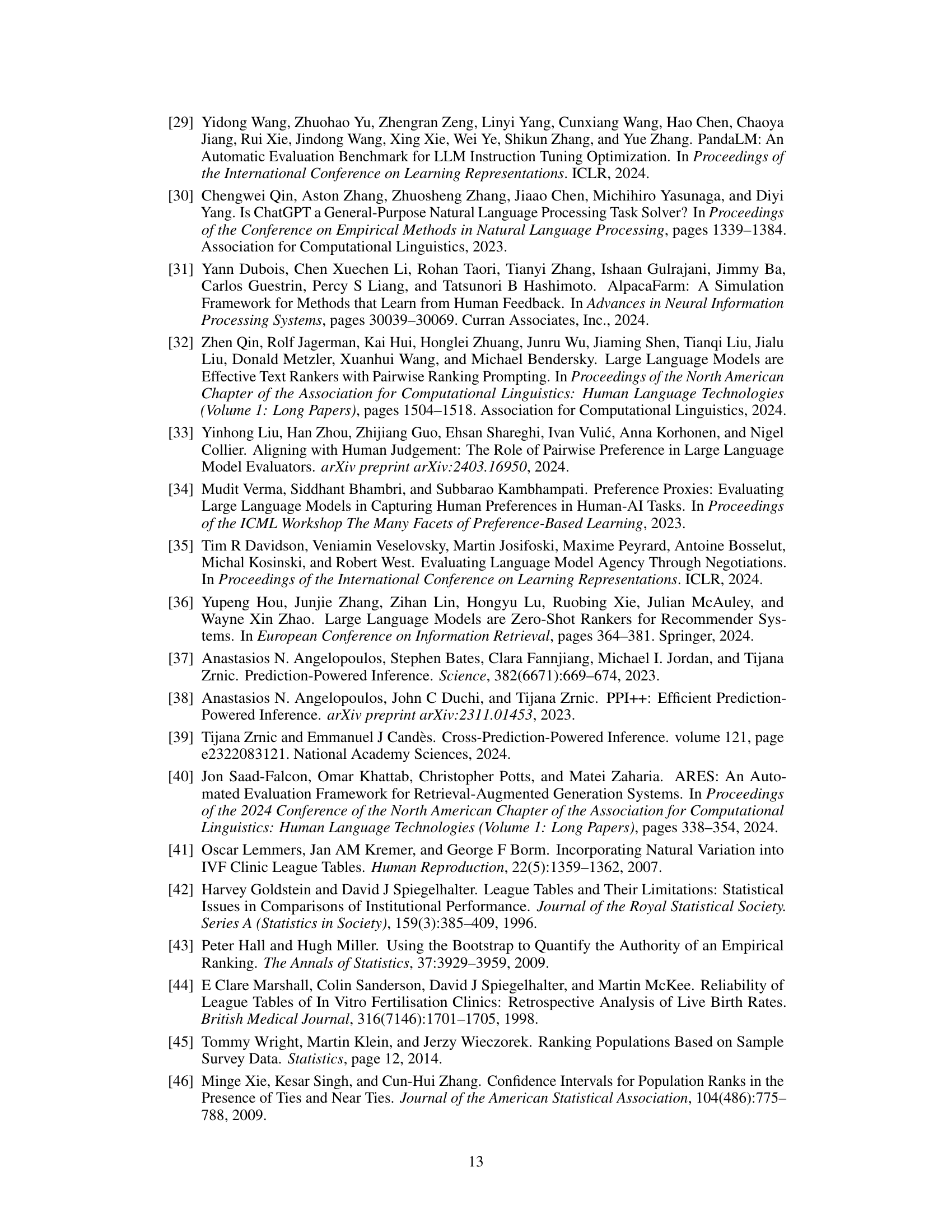

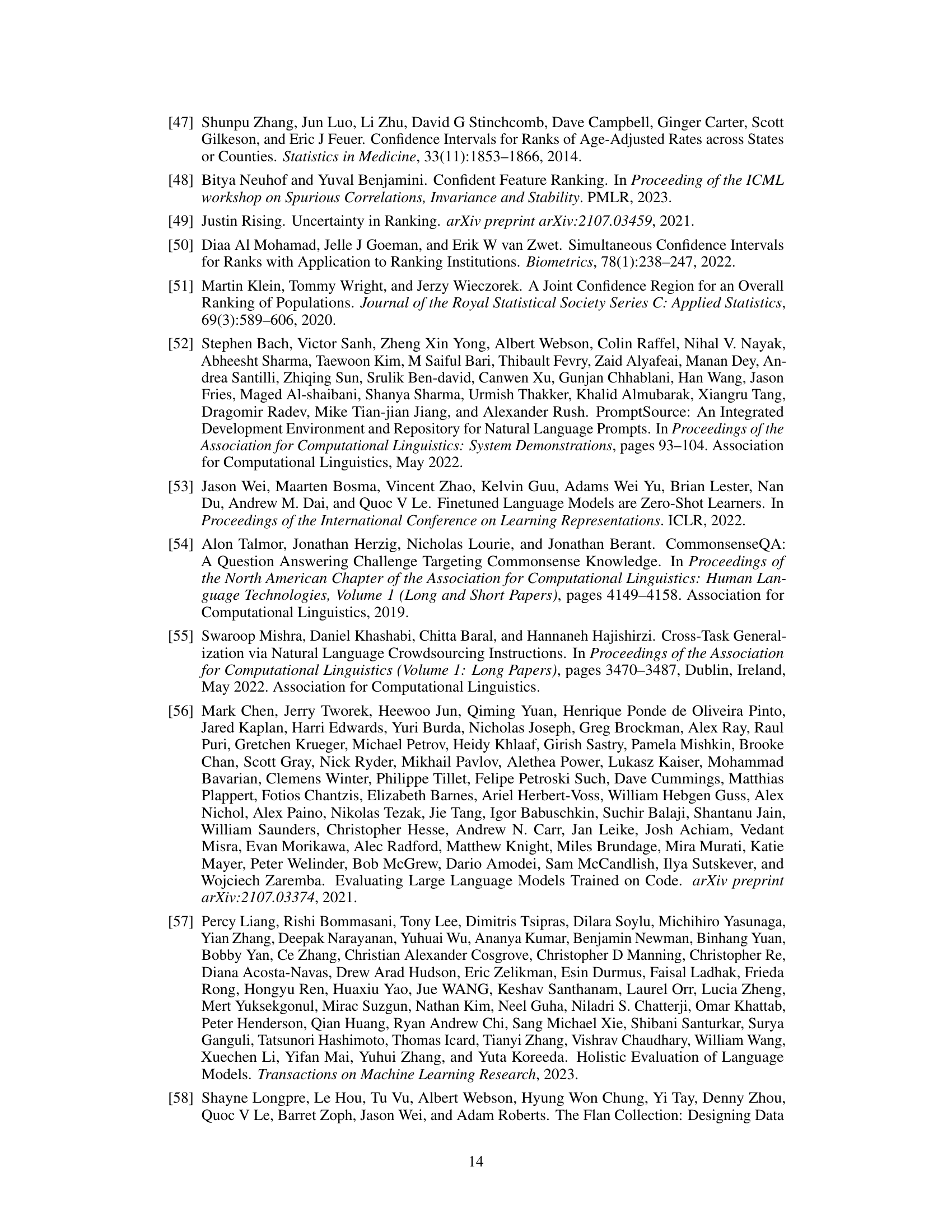

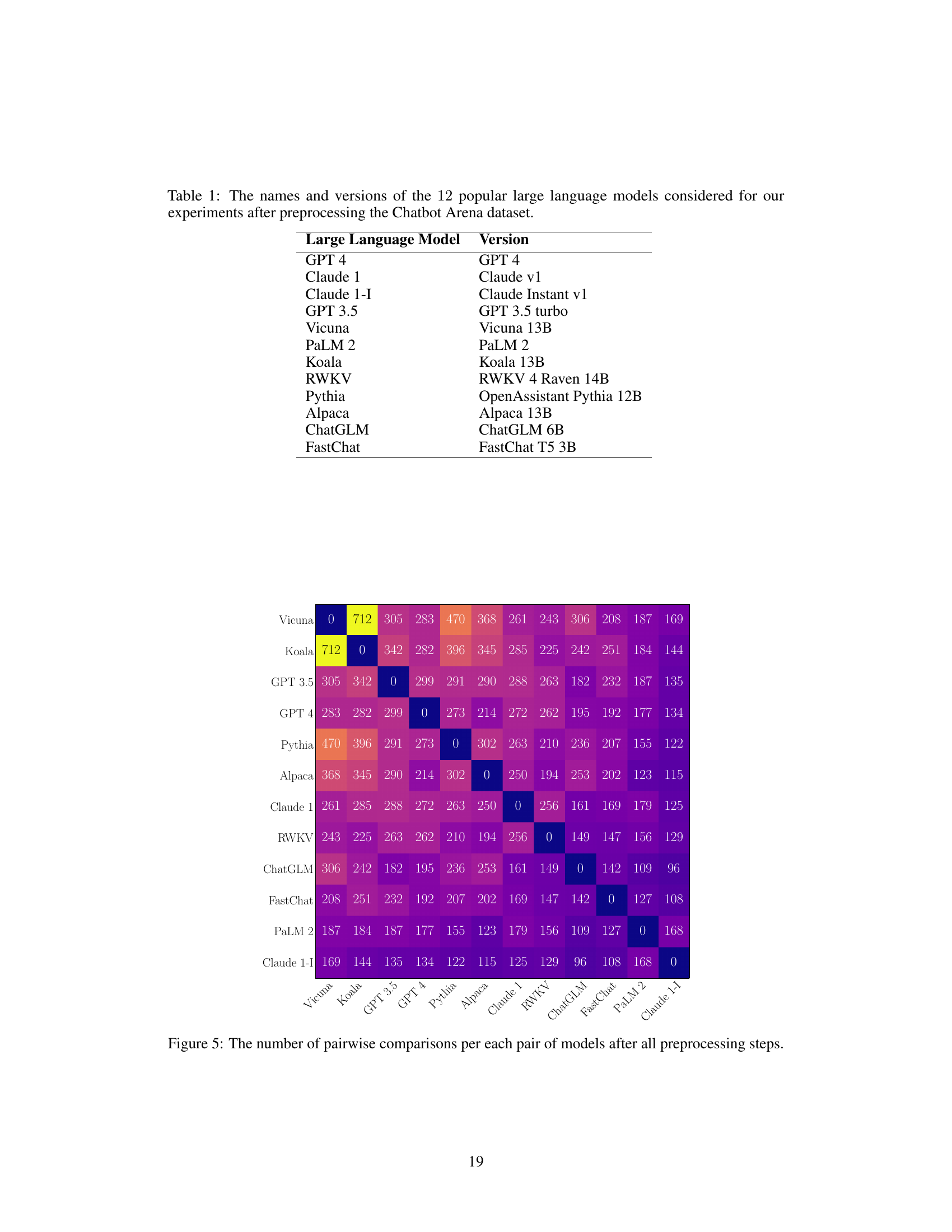

🔼 This table lists the twelve large language models used in the experiments after data preprocessing. It provides the model name and the specific version used for each model.

read the caption

Table 1: The names and versions of the 12 popular large language models considered for our experiments after preprocessing the Chatbot Arena dataset.

In-depth insights#

LLM Rank Uncertainty#

The concept of “LLM Rank Uncertainty” highlights the inherent challenges in definitively ranking Large Language Models (LLMs). Traditional ranking methods often rely on limited data (e.g., human evaluations) and may not capture the full picture of model performance across diverse tasks. This uncertainty stems from several factors: the inherent subjectivity of human preferences, the context-dependent nature of LLM capabilities, and the computational cost of extensive benchmarking. Addressing this requires sophisticated statistical frameworks, such as those employing confidence intervals or rank-sets, to quantify the uncertainty associated with any given ranking. A key takeaway is that acknowledging this uncertainty is critical for responsible development and deployment of LLMs, avoiding overreliance on seemingly definitive but potentially misleading rankings. Future research should focus on developing robust methods for quantifying and mitigating LLM rank uncertainty, leading to more transparent and reliable comparisons of models.

PPR Inference#

Prediction-Powered Ranking (PPR) inference is a novel statistical framework designed to address the challenges of ranking large language models (LLMs) based on human preferences. Traditional methods rely heavily on extensive and costly human evaluations. PPR leverages a smaller set of human-provided pairwise comparisons in conjunction with a larger set from a strong LLM, acting as a proxy for human preferences. This approach significantly reduces the reliance on human effort, making LLM ranking more efficient. A key innovation is the use of rank-sets, representing the range of possible positions for each LLM in the ranking, rather than providing a single, fixed rank. This quantification of uncertainty inherent in the LLM ranking process is crucial. The framework constructs these rank-sets to cover the true human preference ranking with a high probability, even accounting for potential mismatches between human and model preferences. The methodology’s effectiveness is empirically validated through experiments comparing rankings generated by different LLMs, highlighting the advantages of using PPR inference over solely relying on LLM-based preferences.

Rank-Set Coverage#

Rank-set coverage is a crucial concept for evaluating the reliability of model ranking in situations with inherent uncertainty. It addresses the challenge of assigning a single rank to a model when its true position within a ranking is unclear, which is common when relying on a limited amount of data or noisy comparisons. Instead of assigning a specific rank, rank-set coverage provides a range of plausible ranks, forming a set or interval that likely contains the model’s true position. The probability of a rank set covering the true rank is a key metric, indicating the confidence in the ranking process. High coverage signifies that the method is robust and less prone to misranking models due to uncertainty in the preferences. A high coverage probability gives credence to the rank-sets, while low coverage suggests that more data or more reliable preference information is necessary to improve the ranking’s reliability. The development of effective techniques for constructing rank-sets with high coverage probabilities is, therefore, vital for enhancing the accuracy and dependability of large language model ranking.

Human-Model Gap#

The concept of “Human-Model Gap” in the context of large language model (LLM) evaluation highlights the discrepancy between human judgments and model-generated rankings of LLM performance. This gap arises because models, even those trained to align with human preferences, often fail to perfectly capture human nuance, subjectivity, and biases. A key challenge is the cost and time involved in gathering human preference data, leading to reliance on model-based comparisons, which inherently introduce bias. Understanding and mitigating this gap is crucial for building more reliable and trustworthy LLMs; methods for quantifying this discrepancy and incorporating uncertainty are vital. Future work should focus on developing more sophisticated models of human preference that account for diverse perspectives and the inherent complexity of human judgment, rather than merely relying on simplified pairwise comparisons.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework to handle distribution shifts in pairwise comparisons, moving beyond the i.i.d. assumption, is crucial for real-world applicability. Addressing the potential for strategic manipulation of pairwise comparisons by adversarial actors is another key area needing attention, demanding the development of robust and tamper-proof ranking mechanisms. Developing finite-sample coverage guarantees, instead of asymptotic ones, would significantly enhance the practical utility of the statistical framework. Finally, exploring alternative measures of uncertainty beyond rank-sets and investigating the applicability of the framework to other ranking problems and datasets would broaden its impact and demonstrate its generalizability. Investigating alternative quality metrics, potentially beyond win-rates, for high-dimensional settings is also needed to increase efficiency.

More visual insights#

More on figures

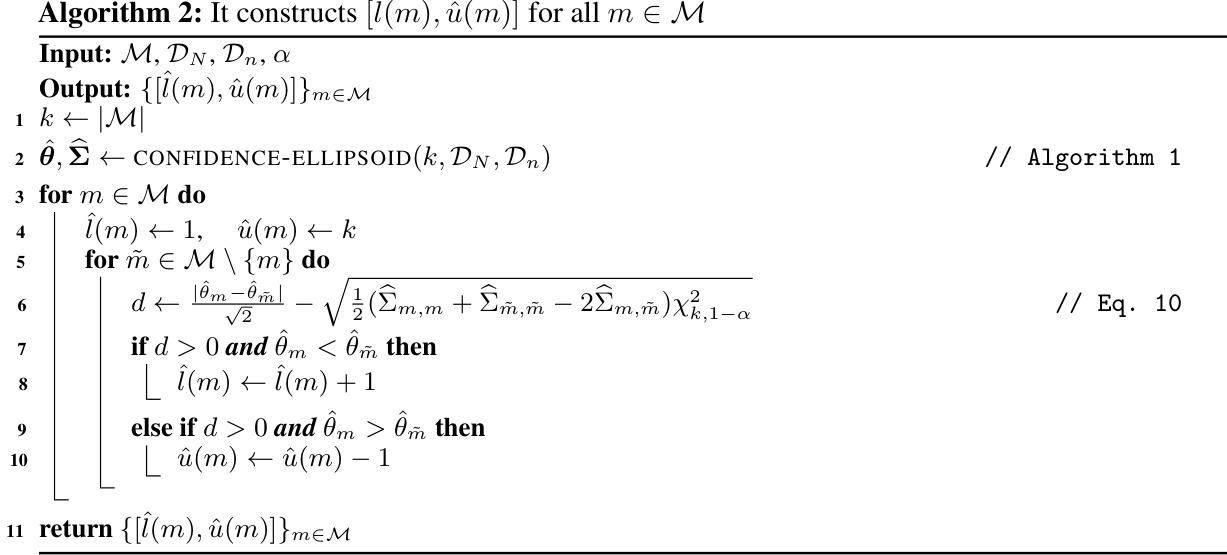

🔼 This figure displays the trade-off between the average size of the rank-sets and the baseline intersection probability for different methods of constructing rank-sets for 12 LLMs. The methods compared are using only human pairwise comparisons, only strong LLMs’ pairwise comparisons, and a combination of both. Smaller rank-sets and higher intersection probabilities indicate better results. The figure shows that combining human and strong LLM data produces more accurate rank-sets than using only strong LLM data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

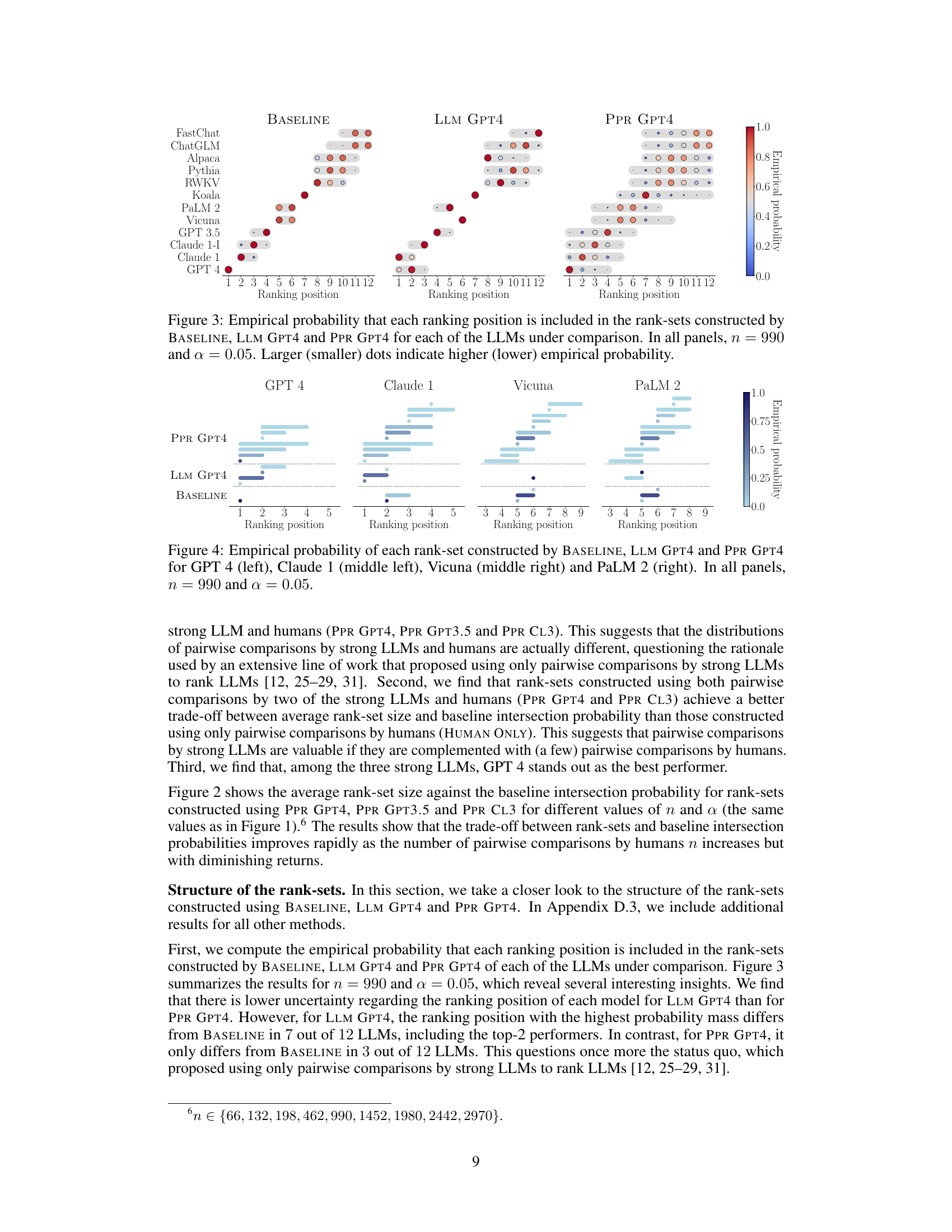

🔼 This figure compares different methods for constructing rank-sets of LLMs, using pairwise comparison data from both humans and strong LLMs. The x-axis represents the baseline intersection probability (a measure of how well the rank-set aligns with a human-only baseline), and the y-axis is the average rank-set size. Smaller rank-sets and higher baseline intersection probabilities indicate better performance. The figure demonstrates that combining human and strong LLM data yields better results (PPR methods) than using only strong LLM data (LLM methods). Human-only data (HUMAN ONLY) is also shown for comparison.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

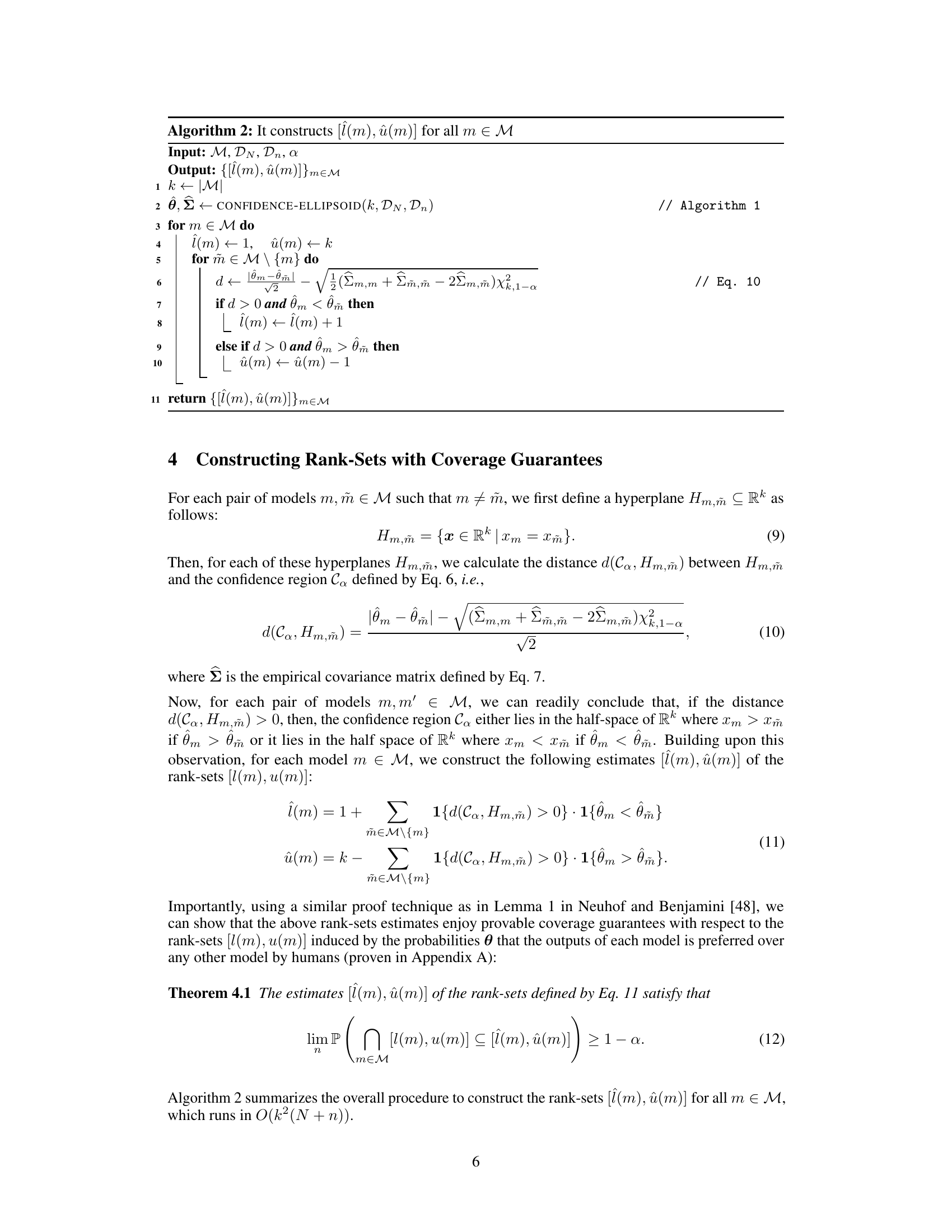

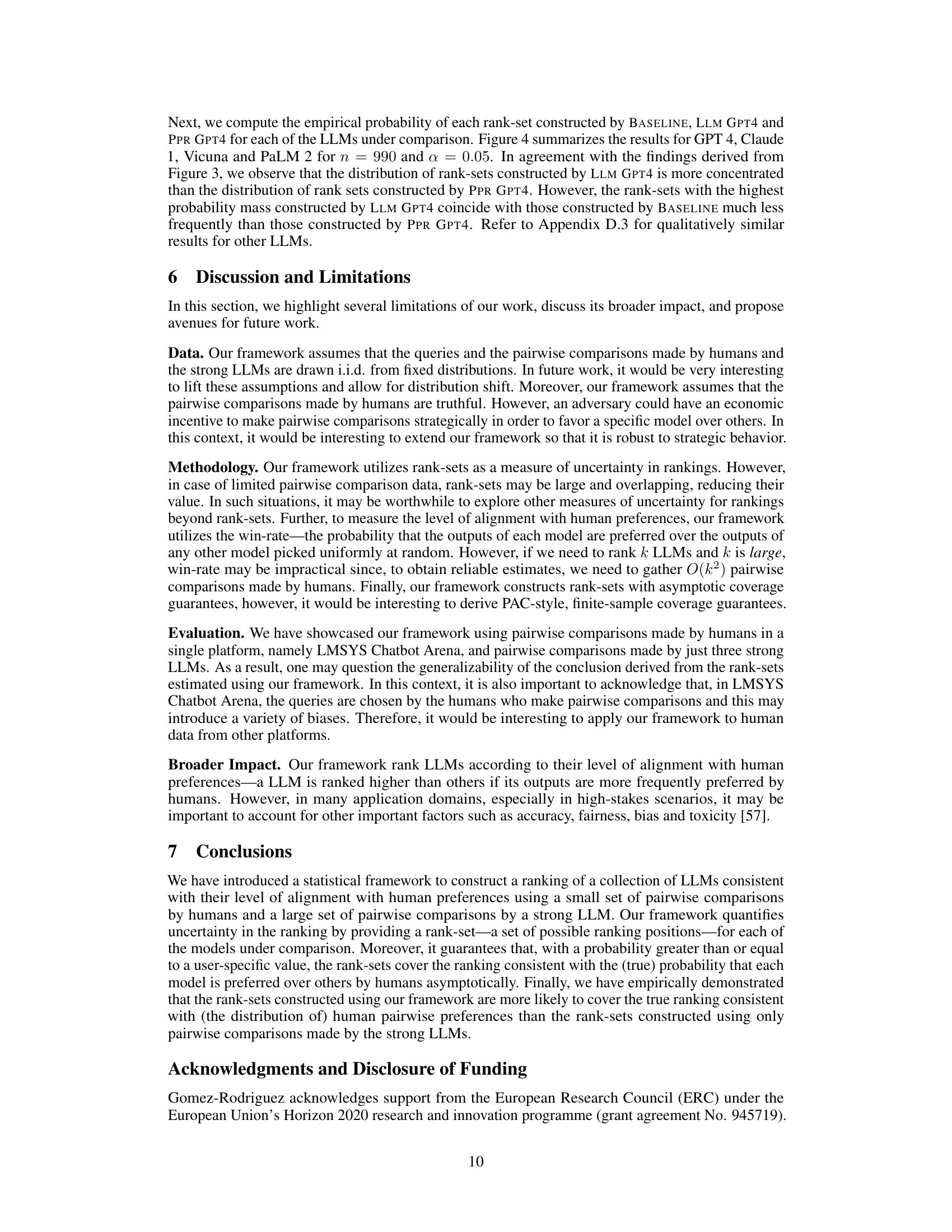

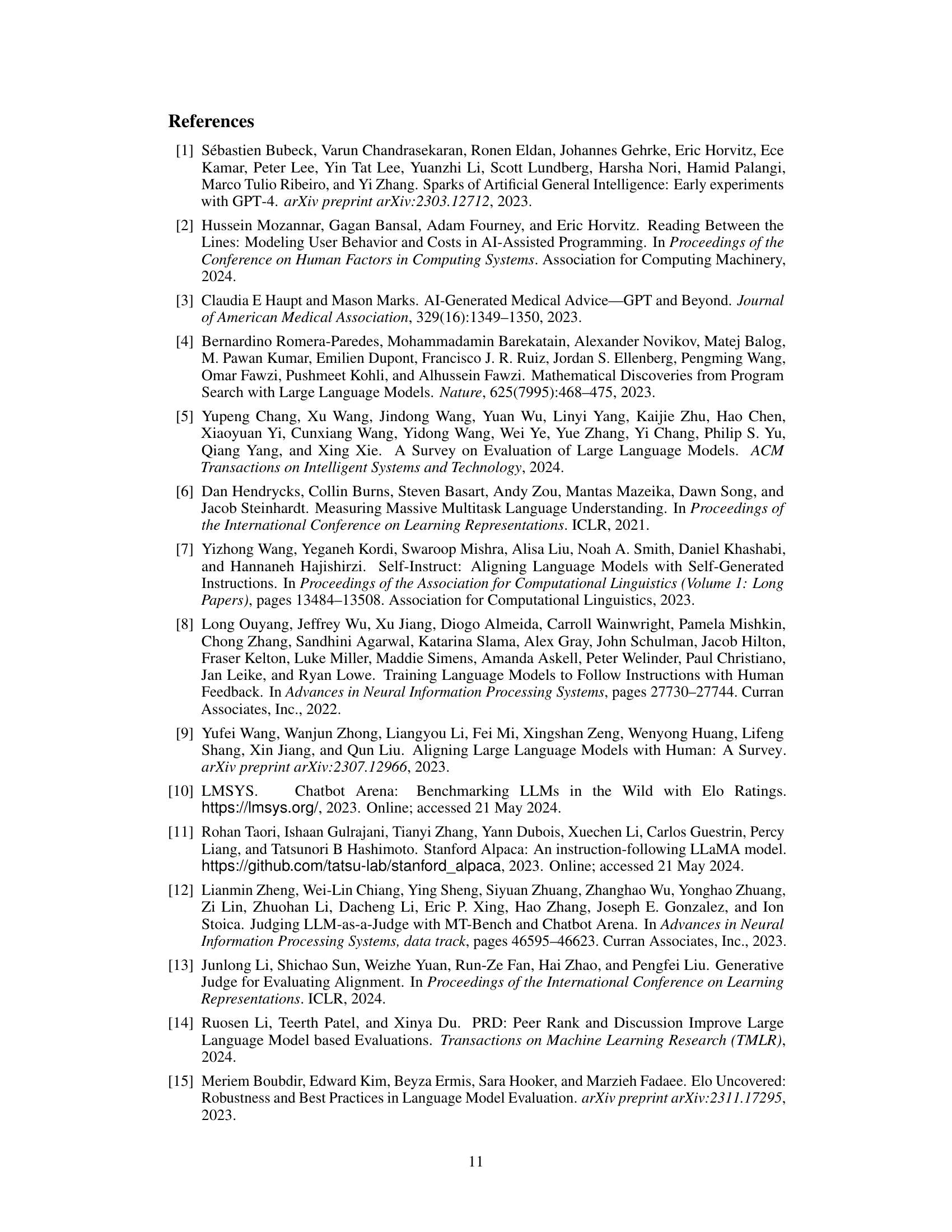

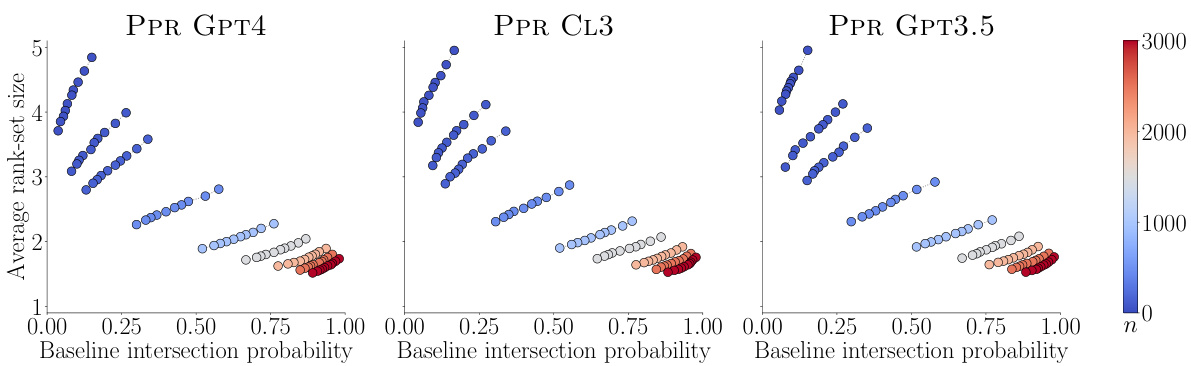

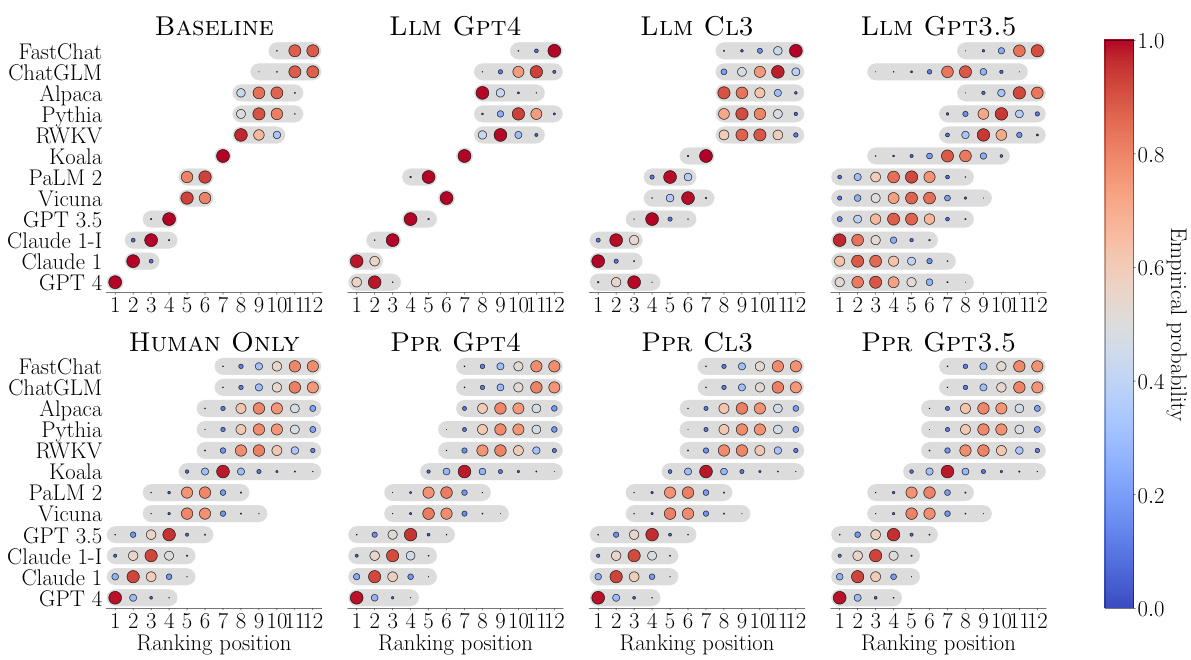

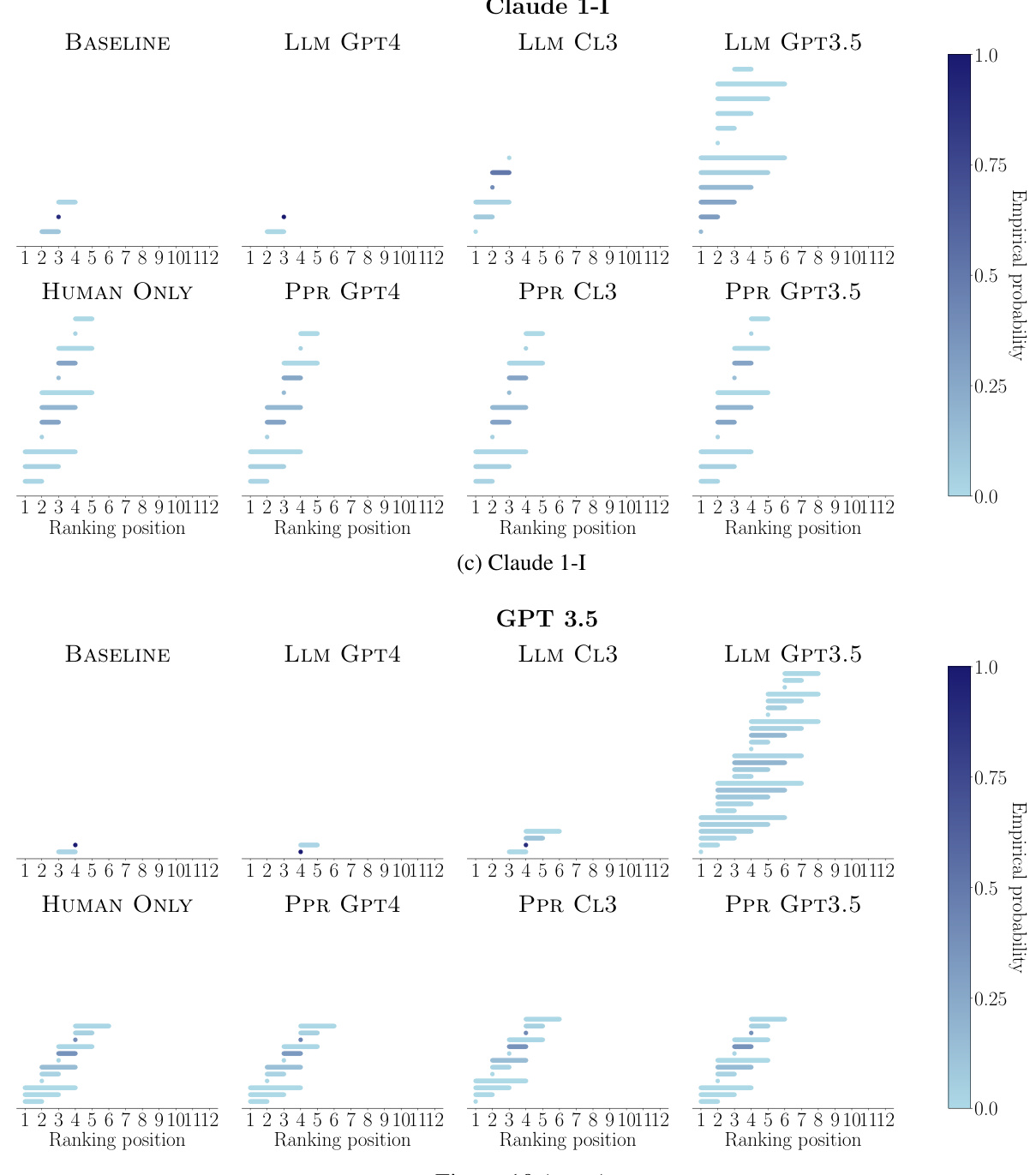

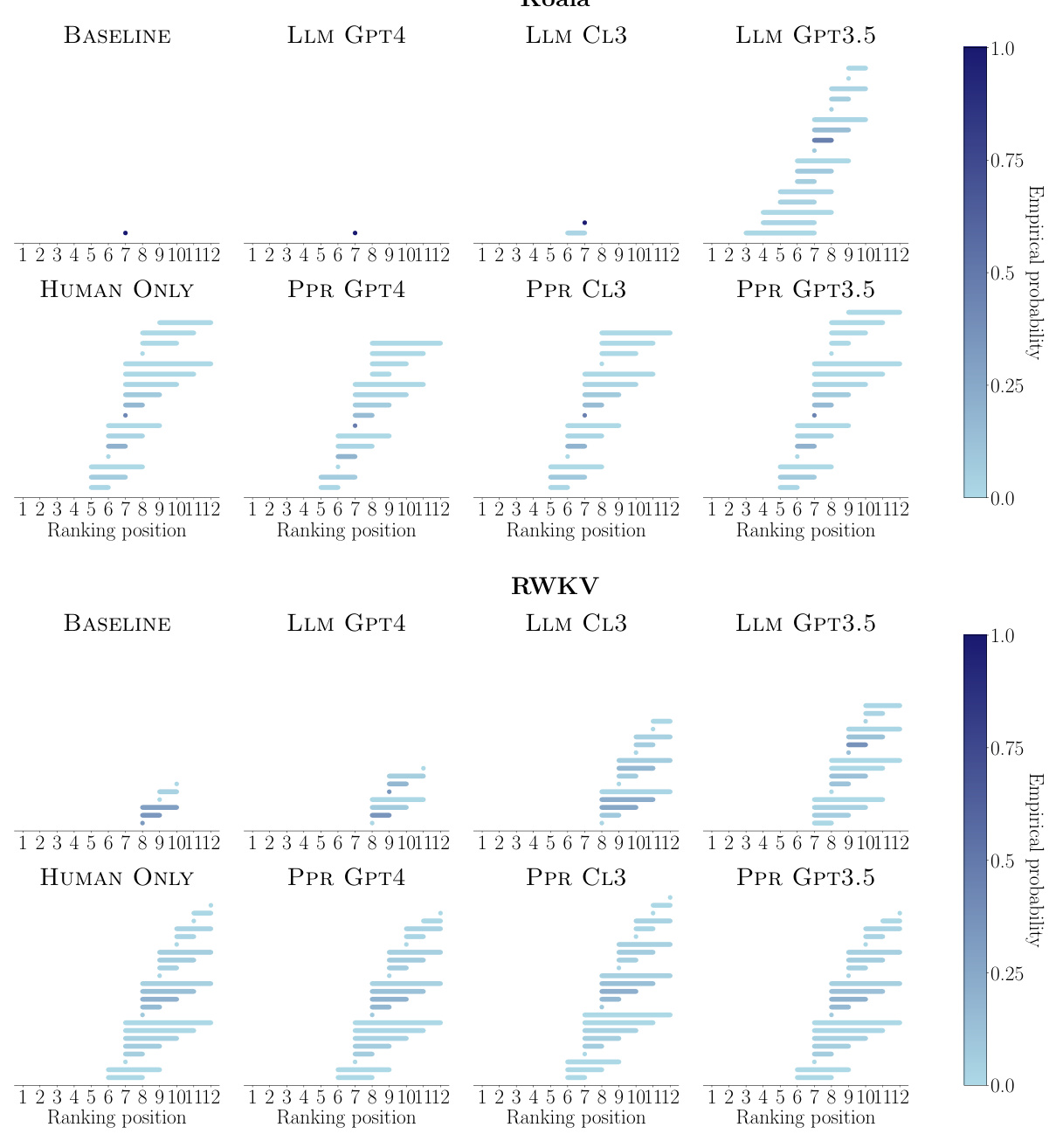

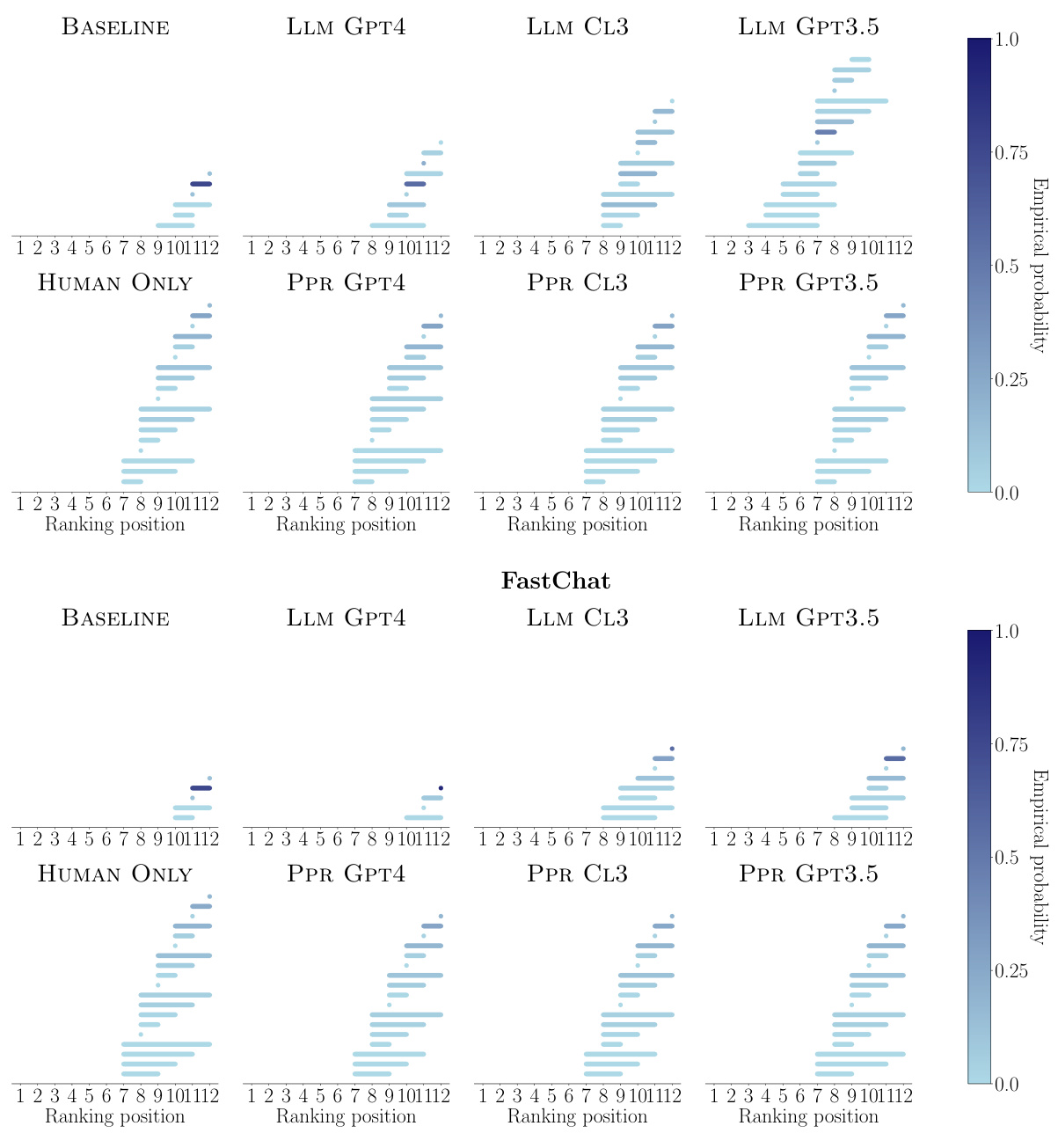

🔼 This figure compares the empirical probability of each ranking position being included in the rank-sets generated by three different methods: BASELINE (using human and strong LLM comparisons), LLM GPT4 (using only GPT-4 comparisons), and PPR GPT4 (combining human and GPT-4 comparisons). The size of each dot represents the probability, with larger dots indicating higher probability. The results are shown for each of the 12 LLMs being evaluated. The figure aims to demonstrate that the method combining human and strong LLM data produces rank-sets that more accurately represent the true human ranking than using only a strong language model.

read the caption

Figure 3: Empirical probability that each ranking position is included in the rank-sets constructed by BASELINE, LLM GPT4 and PPR GPT4 for each of the LLMs under comparison. In all panels, n = 990 and a = 0.05. Larger (smaller) dots indicate higher (lower) empirical probability.

🔼 This figure compares the empirical probability of each ranking position being included in the rank-sets generated by three different methods: BASELINE (using only human pairwise comparisons), LLM GPT4 (using only GPT-4 pairwise comparisons), and PPR GPT4 (using both human and GPT-4 pairwise comparisons). The results visualize the uncertainty in ranking positions for each LLM across the different methods, with larger dots representing higher probability. The parameters n=990 and α=0.05 were used for all methods.

read the caption

Figure 3: Empirical probability that each ranking position is included in the rank-sets constructed by BASELINE, LLM GPT4 and PPR GPT4 for each of the LLMs under comparison. In all panels, n = 990 and a = 0.05. Larger (smaller) dots indicate higher (lower) empirical probability.

🔼 This figure displays the trade-off between the average size of rank-sets and their intersection probability with a baseline. The rank-sets were generated using different methods: only strong LLMs, only human comparisons, and a combination of both. Smaller rank-sets and higher intersection probability indicate better ranking performance, with the combined human and LLM approach generally outperforming methods using only one data source.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 The figure displays the average rank-set size plotted against the baseline intersection probability for different methods of constructing rank-sets. Each method uses a different combination of human and strong LLM pairwise comparisons. Smaller rank-set sizes and higher intersection probabilities indicate better performance. The results show that combining human and strong LLM comparisons yields better results than using only strong LLM comparisons.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 This figure compares different methods for constructing rank sets of LLMs. It shows the tradeoff between average rank-set size (uncertainty) and baseline intersection probability (how often the rank set covers the true ranking). Smaller rank-sets and higher intersection probabilities are better. The methods compared include using only human pairwise comparisons, only strong LLM comparisons, and combining both. The results show that combining human and strong LLM comparisons generally performs better than using only one type of comparison.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 This figure shows the trade-off between the average size of rank-sets and the baseline intersection probability for different methods of constructing rank-sets. The methods compared include using only pairwise comparisons from a strong language model, only human comparisons, and a combination of both. Smaller rank-sets and higher baseline intersection probabilities are preferred, indicating better ranking performance.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 This figure compares different methods for constructing rank sets of LLMs. The x-axis represents the baseline intersection probability (how often the rank sets overlap with those generated using only human comparisons), and the y-axis represents the average rank-set size. Lower average sizes and higher intersection probabilities indicate better performance. The results show that using a combination of human and strong LLM pairwise comparisons produces better rank sets than using only strong LLM or only human data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of a and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

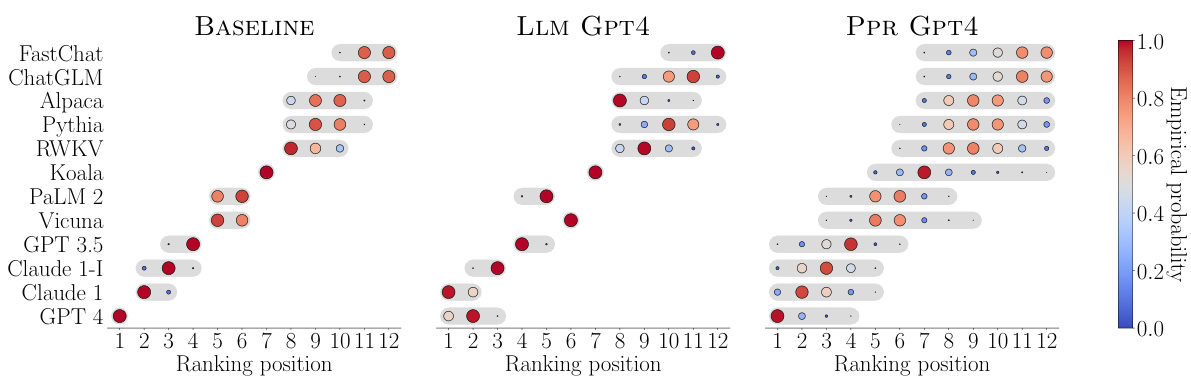

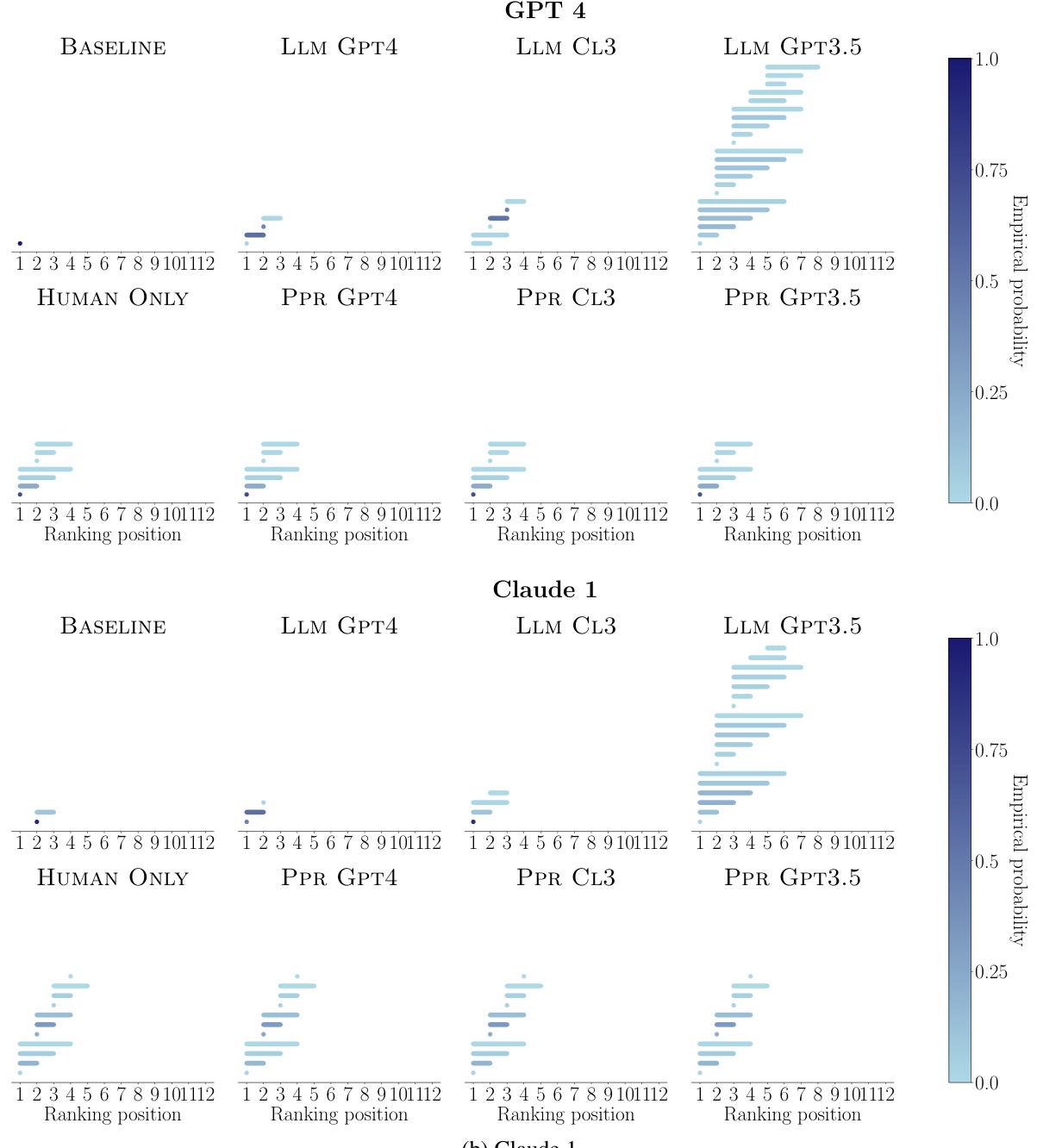

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the average size of rank-sets and their baseline intersection probability for different methods of constructing rank-sets. The methods include using pairwise comparisons from only a strong Language Model (LLM), only humans, and a combination of both. The results show that using both human and strong LLM comparisons leads to a better balance between rank-set size and intersection probability, suggesting that combining both sources of information is beneficial.

read the caption

Figure 6: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM CL3 and LLM GPT3.5), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4 top, PPR CL3 middle and PPR GPT3.5 bottom) for different a values and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 This figure compares the empirical probability of each ranking position being included in the rank-sets generated by three different methods: BASELINE (using human pairwise comparisons), LLM GPT4 (using only GPT-4’s pairwise comparisons), and PPR GPT4 (combining human and GPT-4 pairwise comparisons). The results show the uncertainty associated with each model’s ranking position across the three methods, revealing insights into how the reliability of the ranking changes depending on the data used (human judgments versus model-generated preferences). The size of the dots represents the probability, with larger dots signifying higher probability.

read the caption

Figure 3: Empirical probability that each ranking position is included in the rank-sets constructed by BASELINE, LLM GPT4 and PPR GPT4 for each of the LLMs under comparison. In all panels, n = 990 and a = 0.05. Larger (smaller) dots indicate higher (lower) empirical probability.

🔼 This figure compares different methods for constructing rank-sets of LLMs, showing the trade-off between average rank-set size and baseline intersection probability. It demonstrates that using a combination of human and strong LLM pairwise comparisons (PPR) leads to smaller rank-sets and higher intersection probabilities than using only strong LLMs or only humans. The results suggest that incorporating some human judgment improves ranking accuracy and reduces uncertainty.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 This figure compares different methods for constructing rank sets of LLMs. The x-axis represents the baseline intersection probability, indicating how often the rank sets constructed by a given method overlap with those generated using human comparisons. The y-axis shows the average size of the rank sets. Methods using only strong LLMs show smaller intersection probability and larger rank sets, while methods incorporating both human and strong LLM data demonstrate better results with smaller rank sets and higher intersection probabilities.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 This figure compares different methods for constructing rank-sets of LLMs. The x-axis represents the baseline intersection probability (how often rank sets from the method overlap with rank sets from the human-only baseline). The y-axis is the average rank-set size. Smaller rank-sets and higher baseline intersection probabilities indicate better performance. The methods include using only a strong LLM’s comparisons, only human comparisons, and a combination of both. The results show that combining human and strong LLM data generally outperforms using only strong LLM data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 This figure compares different methods for constructing rank-sets of LLMs, based on pairwise comparisons from humans and strong LLMs. It shows the trade-off between the average size of the rank-sets and their intersection probability with a baseline (human-only) ranking. Smaller rank-sets and higher intersection probabilities indicate better performance. The results highlight that combining human and strong LLM comparisons (PPR methods) generally yields better results than using only strong LLM comparisons (LLM methods), showing the benefit of incorporating human data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 This figure compares different methods for constructing rank-sets of LLMs based on pairwise comparisons from humans and strong LLMs. It plots the average rank-set size against the baseline intersection probability. Smaller rank-sets and higher intersection probabilities indicate better performance. The results show that using a combination of human and strong LLM comparisons yields better results than using strong LLMs alone.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 This figure displays the average rank-set size plotted against the baseline intersection probability for different methods of constructing rank-sets. The methods vary in how they utilize pairwise comparisons from humans and strong LLMs. Smaller rank-set sizes and higher intersection probabilities indicate better performance. The results show that combining human and strong LLM comparisons generally outperforms using strong LLM comparisons alone, particularly in terms of having smaller rank-sets and higher baseline intersection probabilities.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

🔼 The figure displays a comparison of rank-set size and baseline intersection probability across various methods of constructing rank-sets for LLMs. It evaluates the methods using only human pairwise comparisons, only strong LLMs’ pairwise comparisons, and a combination of both. Smaller rank-sets and higher baseline intersection probabilities are preferred, indicating better accuracy in ranking the LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 1: Average rank-set size against baseline intersection probability for rank-sets constructed using only pairwise comparisons by a strong LLM (LLM GPT4, LLM GPT3.5 and LLM CL3), only pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and pairwise comparisons by both a strong LLM and humans (PPR GPT4, PPR GPT3.5 and PPR CL3) for different values of α and n = 990. Smaller (larger) average rank-set sizes and larger (smaller) intersection probabilities are better (worse). In all panels, 95% confidence bars for the rank-set size are not shown, as they are always below 0.02.

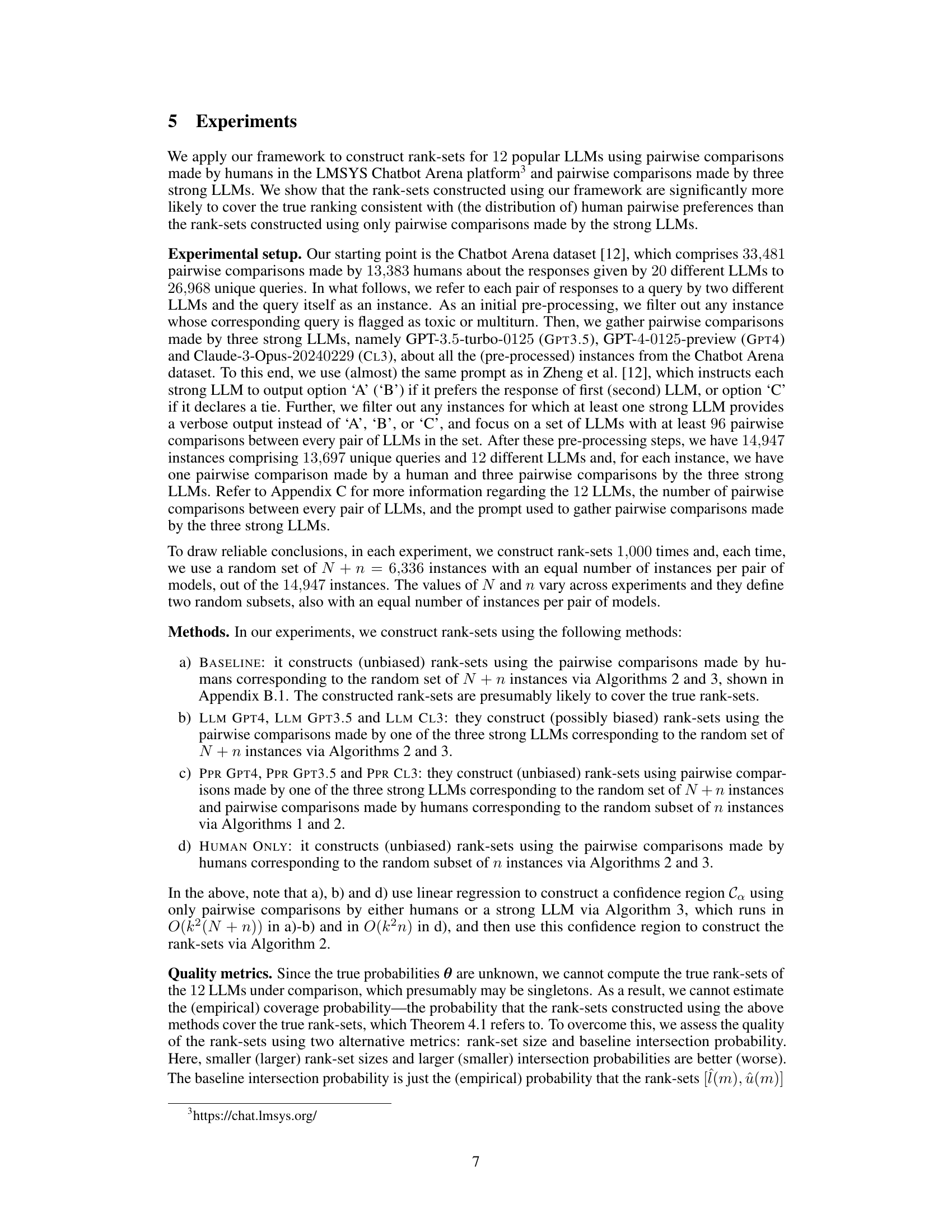

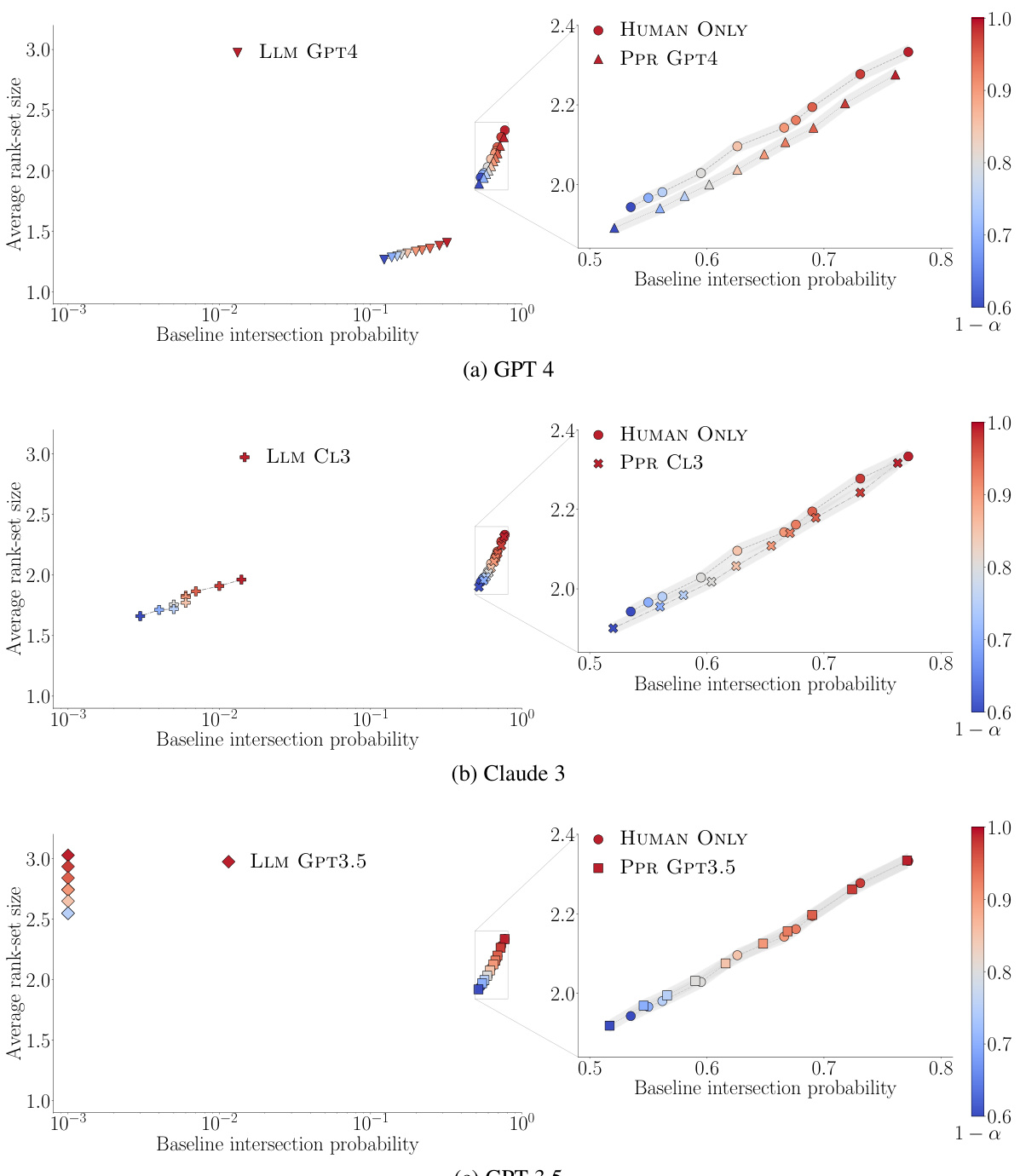

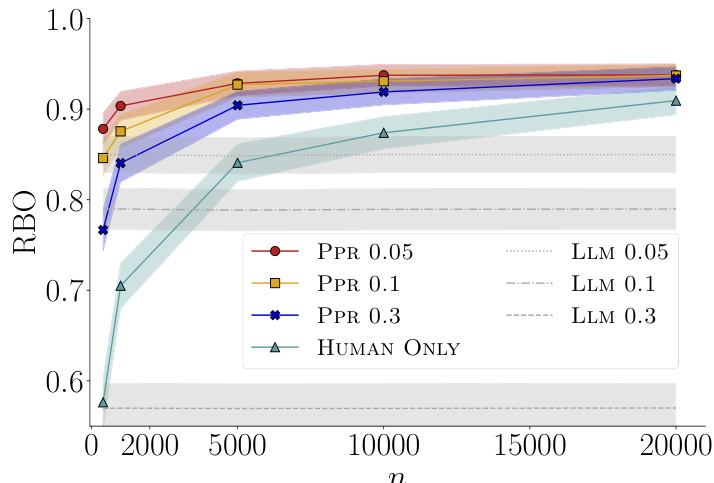

🔼 This figure compares the rank-biased overlap (RBO) values for different methods of ranking LLMs using synthetic data. The methods are using only human comparisons, only strong LLM comparisons, and combining human and strong LLM comparisons. The results show that incorporating human feedback significantly improves RBO, and better performance when strong LLMs are more closely aligned with human preferences.

read the caption

Figure 12: Average rank-biased overlap (RBO) of rankings constructed by ordering the empirical win probabilities 𝜃 estimated using only N + n synthetic pairwise comparisons by one out of three different simulated strong LLMs (LLM 0.05, LLM 0.1 and LLM 0.3), only n synthetic pairwise comparisons by humans (HUMAN ONLY), and both n synthetic pairwise comparisons by humans and N + n synthetic pairwise comparisons by one out of the same three strong LLMs (PPR 0.05, PPR 0.1 and PPR 0.3) for a = 0.1 and N + n = 50000. Each of the strong LLMs has a different level of alignment with human preferences controlled by a noise value u ∈ {0.05,0.1, 0.3}. RBO was computed with respect to the true ranking constructed by ordering the true win probabilities 𝜃, for p = 0.6. The shaded region shows a 95% confidence interval for the RBO among all 300 repetitions.

Full paper#