TL;DR#

Unsupervised skill discovery often struggles with learning complex and safe behaviors in continuous control tasks. Existing methods may learn unsafe or undesirable behaviors, such as tripping or navigating hazardous areas. This paper introduces DoDont, a novel instruction-based approach that leverages action-free instruction videos to guide the learning process.

DoDont uses an instruction network trained on videos of desirable and undesirable behaviors to adjust the reward function of a distance-maximizing skill discovery algorithm. This ensures that the agent learns intricate movements and avoids risky actions. The results show that DoDont efficiently learns complex and desirable behaviors, outperforming existing methods in various continuous control tasks with minimal instruction videos. The method’s effectiveness highlights its potential for creating reliable and safe AI systems in complex real-world scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in reinforcement learning and robotics. It directly addresses the challenge of safe and efficient skill acquisition in complex environments, a problem hindering the real-world deployment of autonomous systems. By introducing a novel instruction-based method, it opens avenues for integrating human expertise and preferences into automated skill learning, leading to more reliable and predictable behaviors. This approach is highly relevant to current trends in self-supervised learning and foundational models. The proposed framework is easily adaptable to various domains, making it a significant contribution to the broader field.

Visual Insights#

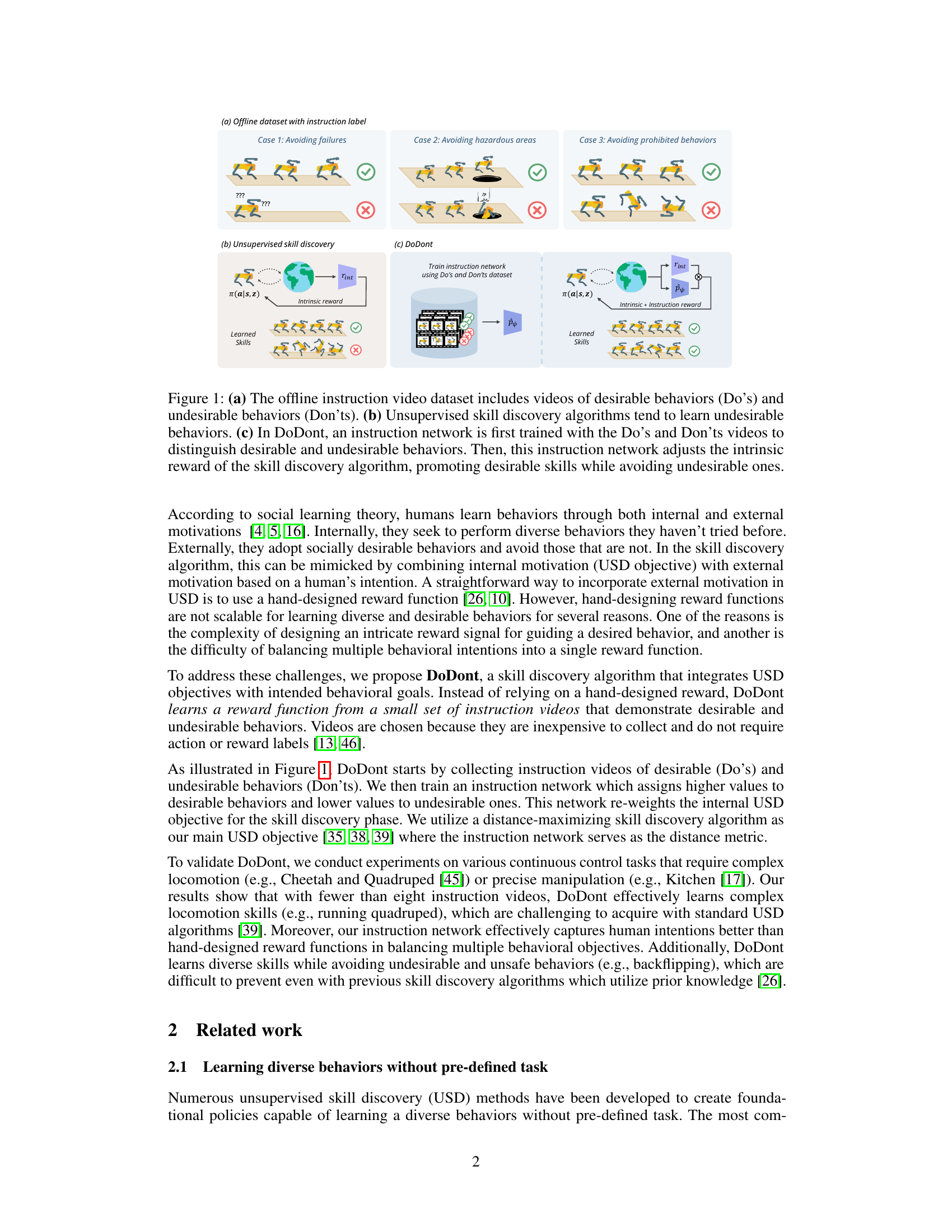

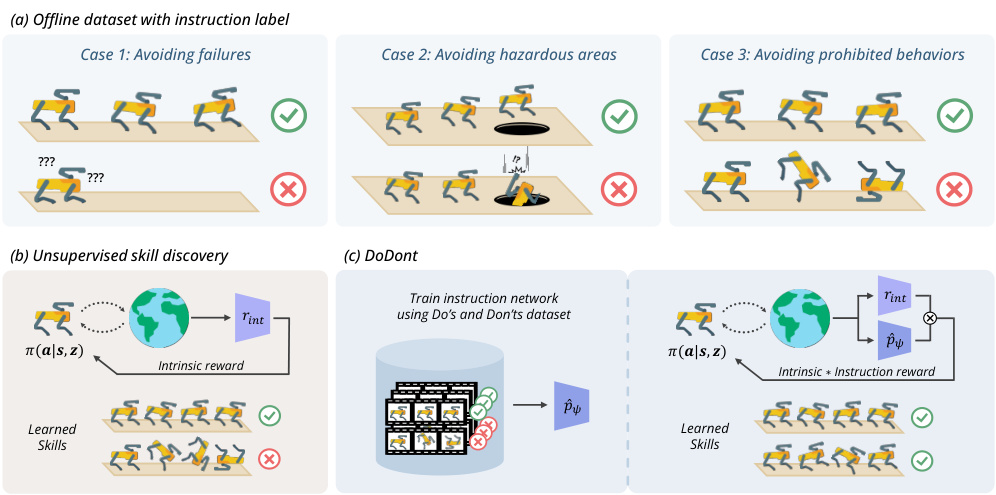

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the DoDont algorithm. Panel (a) shows an offline dataset of instruction videos, labeled as either desirable (‘Do’) or undesirable (‘Don’t’). Panel (b) depicts how unsupervised skill discovery methods often fail to learn complex and desirable skills, instead learning simpler or undesirable ones. Panel (c) demonstrates how DoDont uses an instruction network (trained on the labeled video data) to adjust the reward function of a skill discovery algorithm, guiding it towards learning desirable skills and away from undesirable behaviors.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) The offline instruction video dataset includes videos of desirable behaviors (Do's) and undesirable behaviors (Don'ts). (b) Unsupervised skill discovery algorithms tend to learn undesirable behaviors. (c) In DoDont, an instruction network is first trained with the Do's and Don'ts videos to distinguish desirable and undesirable behaviors. Then, this instruction network adjusts the intrinsic reward of the skill discovery algorithm, promoting desirable skills while avoiding undesirable ones.

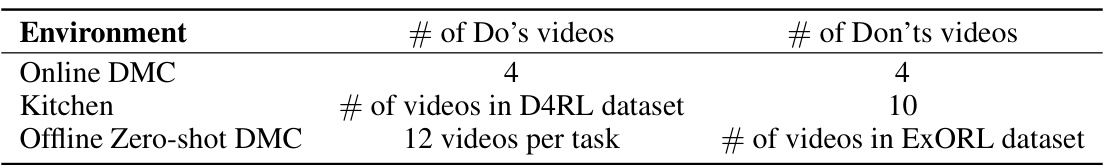

🔼 This table shows the number of Do’s videos and Don’ts videos used for each environment in the DoDont experiments. For the online DeepMind Control (DMC) suite experiments, 4 Do’s videos and 4 Don’ts videos were used. In the Kitchen environment, 10 Don’ts videos were used with the Do’s videos coming from the D4RL dataset. The offline Zero-shot DMC experiments utilized 12 videos per task from the ExORL dataset for the Don’ts, while the Do’s videos were not specified in this table.

read the caption

Table 1: The number of videos used for each environment.

In-depth insights#

Instructed Skill Learning#

Instructed skill learning represents a paradigm shift in reinforcement learning, moving beyond purely unsupervised or reward-based approaches. By incorporating human-provided instructions, often in the form of demonstrations or textual descriptions, this method aims to guide the agent towards learning specific, desirable skills while avoiding undesirable ones. This approach is particularly valuable in complex environments where designing effective reward functions is challenging or when safety is a critical concern. Instructional signals can significantly reduce the exploration time needed to acquire complex behaviors and prevent the learning of dangerous or inefficient actions. Key advantages include improved sample efficiency, enhanced safety, and the ability to leverage pre-existing human knowledge and expertise. However, challenges remain in effectively translating diverse instructional formats into usable signals for the learning agent. Furthermore, the robustness and generalizability of instructed skill learning across different environments and tasks need further exploration. The development of efficient methods to integrate varied instructional modalities with diverse learning algorithms is crucial for advancing this promising field.

DoDont Algorithm#

The core of the DoDont algorithm lies in its two-stage process: instruction learning and skill learning. First, it trains an instruction network using videos labeled as ‘Do’s’ (desirable behaviors) and ‘Don’ts’ (undesirable behaviors). This network learns to distinguish between desirable and undesirable state transitions. In the second stage, this trained network acts as a distance function within a distance-maximizing skill discovery algorithm, effectively shaping the reward function to encourage desirable behaviors and discourage undesirable ones. Key to DoDont’s success is its ability to leverage readily available instruction videos rather than relying on complex hand-designed reward functions, allowing for more efficient learning of intricate and safe behaviors in continuous control tasks. The algorithm’s effectiveness is demonstrated through empirical results showing superior performance in complex locomotion and manipulation tasks compared to existing methods, emphasizing the importance of integrating human intent into skill discovery.

USD Enhancement#

The heading ‘USD Enhancement’ suggests improvements to Unsupervised Skill Discovery (USD) methods. A thoughtful approach would explore how the paper addresses USD’s limitations, such as learning unsafe or undesirable behaviors and struggling with complex tasks. Potential enhancements might involve integrating external guidance, perhaps through demonstrations or instructions, to shape the learning process. Reward shaping, by modifying the reward function based on desired or undesired actions, is another possible avenue. The paper might introduce a novel algorithm that incorporates these enhancements or proposes a new framework for combining USD with supervised learning techniques. It’s crucial to determine if these enhancements improve sample efficiency, generalization ability, and safety, ultimately making USD more reliable and practical for real-world applications. A critical analysis should evaluate the effectiveness of these enhancements and the experimental evidence provided to support their claims. Novel metrics for evaluating USD performance should also be considered, specifically those that emphasize the safety and desired behavior of the acquired skills.

Empirical Results#

A thorough analysis of the ‘Empirical Results’ section would involve a deep dive into the methodologies used, examining whether the chosen metrics appropriately capture the core contributions of the research. It’s crucial to assess the statistical significance of the findings, checking for appropriate error bars, confidence intervals, or hypothesis tests. The reproducibility of the results is paramount, demanding a detailed description of the experimental setup, including data splits, parameters, and any specific considerations. Furthermore, a comparison to related work would solidify the novelty of the presented results. Identifying any limitations within the empirical results, such as dataset biases or potential confounding factors, is also important. Finally, visualizations of the key results should be clear and self-explanatory. A good analysis will not only summarize the findings but also critically evaluate the experimental design, ensuring the reported results support the paper’s overall claims.

Future Work#

The paper’s discussion on future work highlights several crucial areas for improvement and expansion. A key focus is on enhancing the scalability and robustness of the DoDont algorithm. This involves exploring methods to train the instruction network using more general, readily available video data rather than relying on meticulously curated, in-domain examples. Addressing the limitations of relying on video data is essential, especially considering that video data might not always be readily available or easily obtainable for a wide range of tasks. Another important direction is improving the efficiency and scalability of the algorithm, including optimization techniques and reducing computational costs. Investigating zero-shot offline reinforcement learning applications and developing more effective ways to guide the agent’s behavior through the instruction network are critical for the broader application of the approach. Finally, the paper suggests exploring ways to integrate DoDont with other skill discovery techniques or approaches that utilize more varied forms of human intention beyond videos. These aspects will enhance the applicability and impact of the proposed method in complex real-world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the DoDont algorithm. Panel (a) shows the instruction dataset with examples of desirable (‘Do’) and undesirable (‘Don’t’) behaviors. Panel (b) highlights the problem of unsupervised skill discovery methods often learning undesirable behaviors. Panel (c) shows how DoDont solves this by using an instruction network to distinguish between desirable and undesirable transitions, thereby adjusting the reward function of the skill discovery algorithm to encourage desirable behaviors and avoid undesirable ones.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) The offline instruction video dataset includes videos of desirable behaviors (Do's) and undesirable behaviors (Don'ts). (b) Unsupervised skill discovery algorithms tend to learn undesirable behaviors. (c) In DoDont, an instruction network is first trained with the Do's and Don'ts videos to distinguish desirable and undesirable behaviors. Then, this instruction network adjusts the intrinsic reward of the skill discovery algorithm, promoting desirable skills while avoiding undesirable ones.

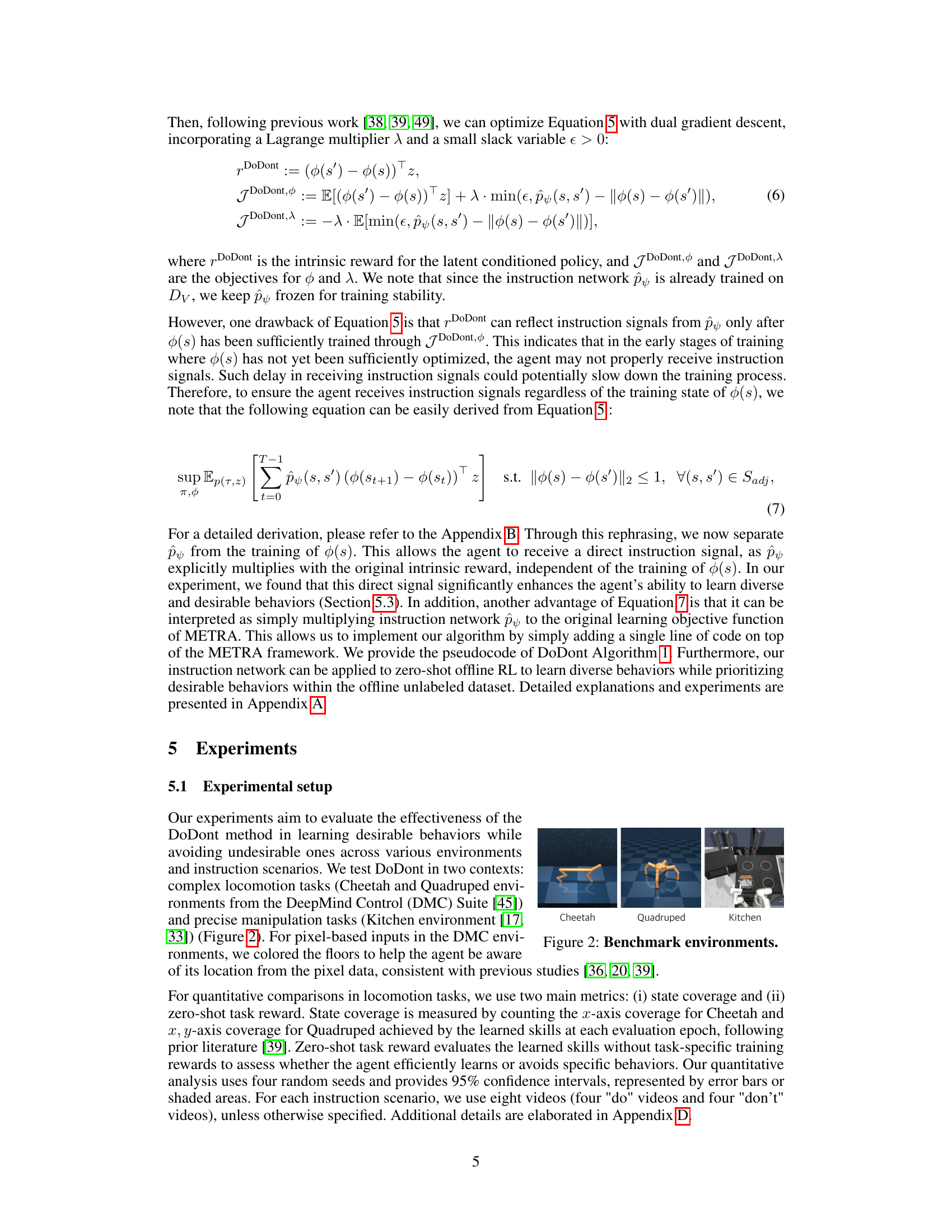

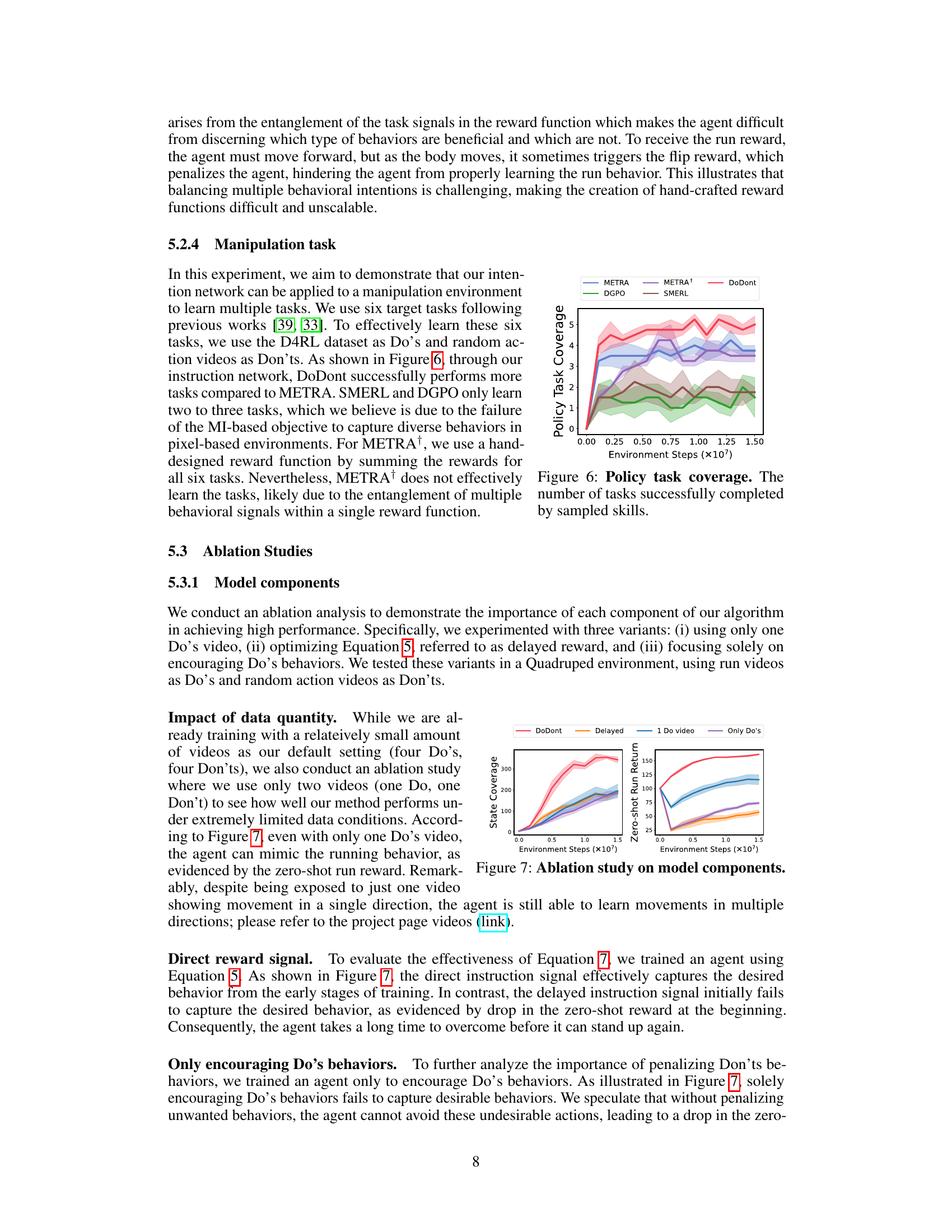

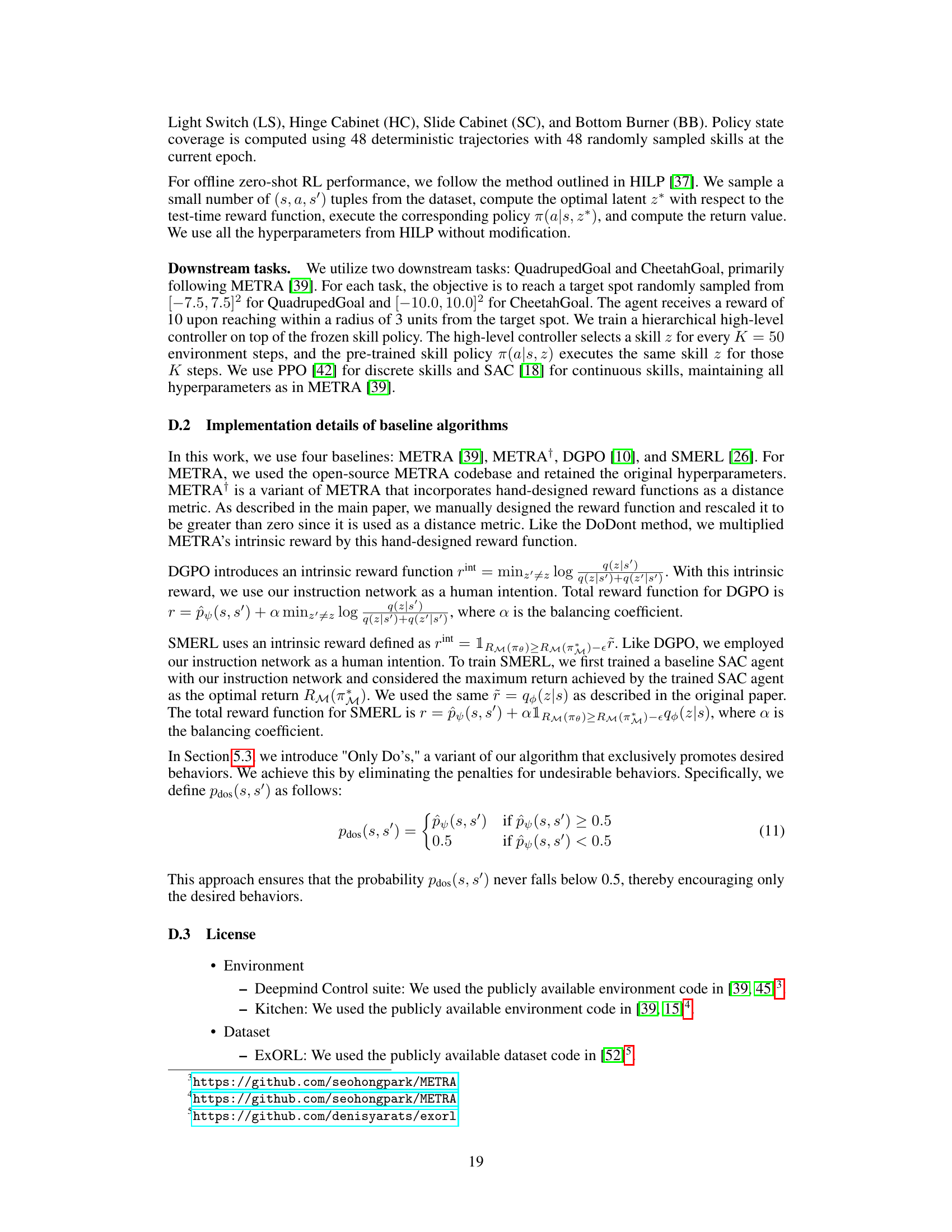

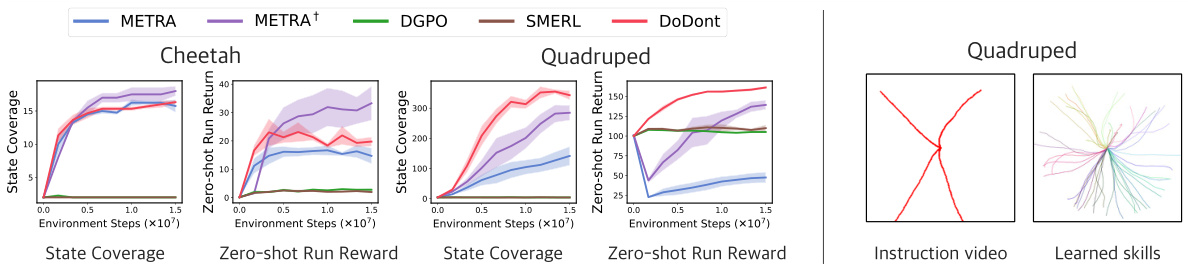

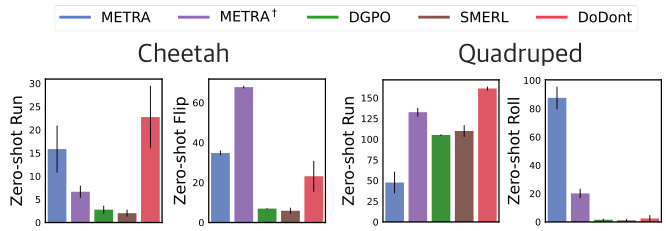

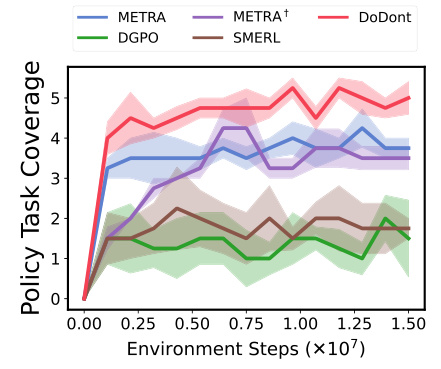

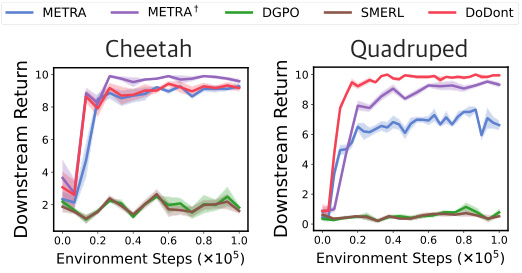

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the performance of DoDont and other baselines on Cheetah and Quadruped locomotion tasks. The left side shows the state coverage and zero-shot run reward for both environments, demonstrating DoDont’s superior ability to learn diverse and desirable skills. The right side visually compares the instruction videos used to train DoDont with the skills learned by the model. The visualization shows that DoDont successfully learns the essential characteristics of desired behaviors such as running, rather than simply imitating the instruction videos.

read the caption

Figure 3: Left: State coverage and zero-shot task reward for Cheetah and Quadruped. Right: Visualization of Do videos in our instruction video dataset and learned skills by DoDont. We are able to observe that DoDont does not simply mimic instruction videos but extracts desirable behaviors (e.g., run) from the videos and learn diverse skills.

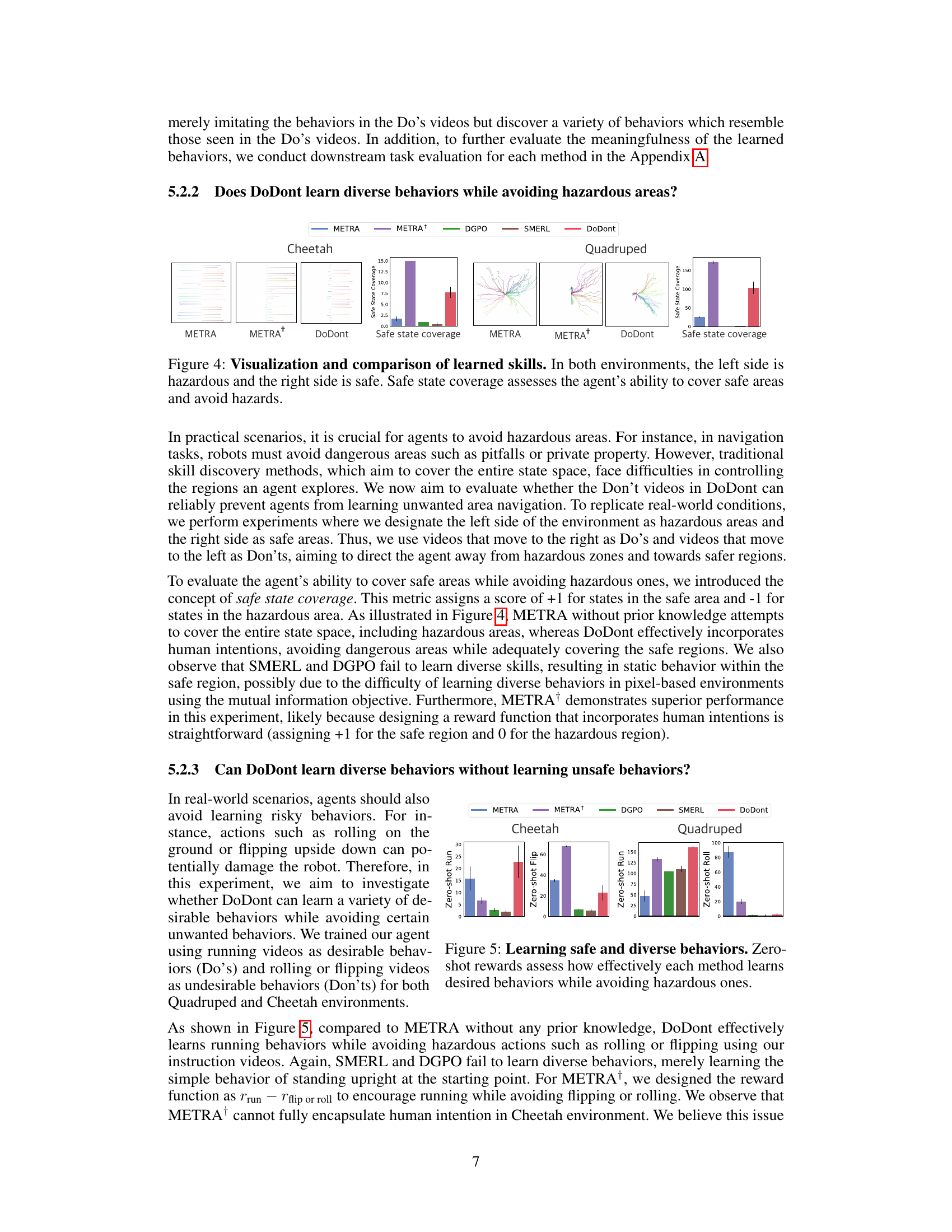

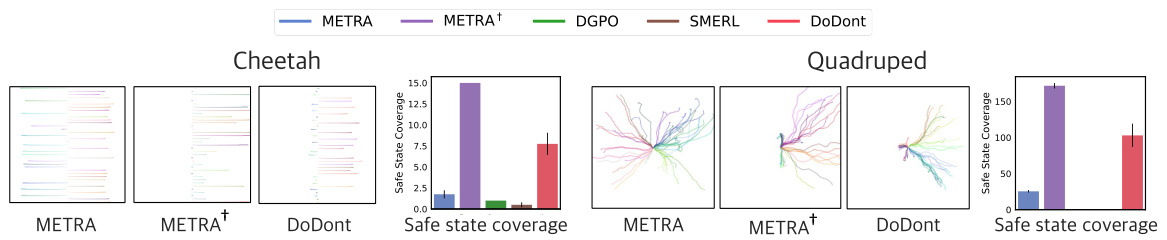

🔼 This figure visualizes and compares the learned skills of different methods in Cheetah and Quadruped environments. The environments are designed with a hazardous area on the left and a safe area on the right. The visualization shows the trajectories learned by each algorithm. The bar charts show the ‘Safe State Coverage’, which measures the extent to which each algorithm explores the safe area while avoiding the hazardous area. This metric helps evaluate the effectiveness of each algorithm in learning safe behaviors while avoiding hazardous ones.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visualization and comparison of learned skills. In both environments, the left side is hazardous and the right side is safe. Safe state coverage assesses the agent's ability to cover safe areas and avoid hazards.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of DoDont with other methods (METRA, METRA+, DGPO, SMERL) on two locomotion tasks: Cheetah and Quadruped. The left side shows state coverage and zero-shot task reward over training time, highlighting DoDont’s superior ability to learn diverse and complex skills. The right side provides a visual comparison of the instruction videos (Do’s) and the skills learned by DoDont, demonstrating its capacity to extract and generalize desirable behaviors rather than just mimicking the videos.

read the caption

Figure 3: Left: State coverage and zero-shot task reward for Cheetah and Quadruped. Right: Visualization of Do videos in our instruction video dataset and learned skills by DoDont. We are able to observe that DoDont does not simply mimic instruction videos but extracts desirable behaviors (e.g., run) from the videos and learn diverse skills.

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of the performance of DoDont against METRA, METRA+, DGPO, and SMERL across two locomotion tasks: Cheetah and Quadruped. The left panel shows the state coverage and zero-shot task reward for each algorithm over time. The right panel provides a visualization of the Do videos used to train the instruction network and the skills learned by DoDont, highlighting DoDont’s ability to learn more diverse and complex skills compared to other methods.

read the caption

Figure 3: Left: State coverage and zero-shot task reward for Cheetah and Quadruped. Right: Visualization of Do videos in our instruction video dataset and learned skills by DoDont. We are able to observe that DoDont does not simply mimic instruction videos but extracts desirable behaviors (e.g., run) from the videos and learn diverse skills.

🔼 This figure shows the results of an experiment comparing DoDont’s performance to other methods in learning locomotion skills. The left panel shows state coverage and zero-shot task reward, demonstrating DoDont’s superior performance. The right panel visualizes DoDont’s ability to learn diverse skills from a small number of instruction videos, without simply mimicking them.

read the caption

Figure 3: Left: State coverage and zero-shot task reward for Cheetah and Quadruped. Right: Visualization of Do videos in our instruction video dataset and learned skills by DoDont. We are able to observe that DoDont does not simply mimic instruction videos but extracts desirable behaviors (e.g., run) from the videos and learn diverse skills.

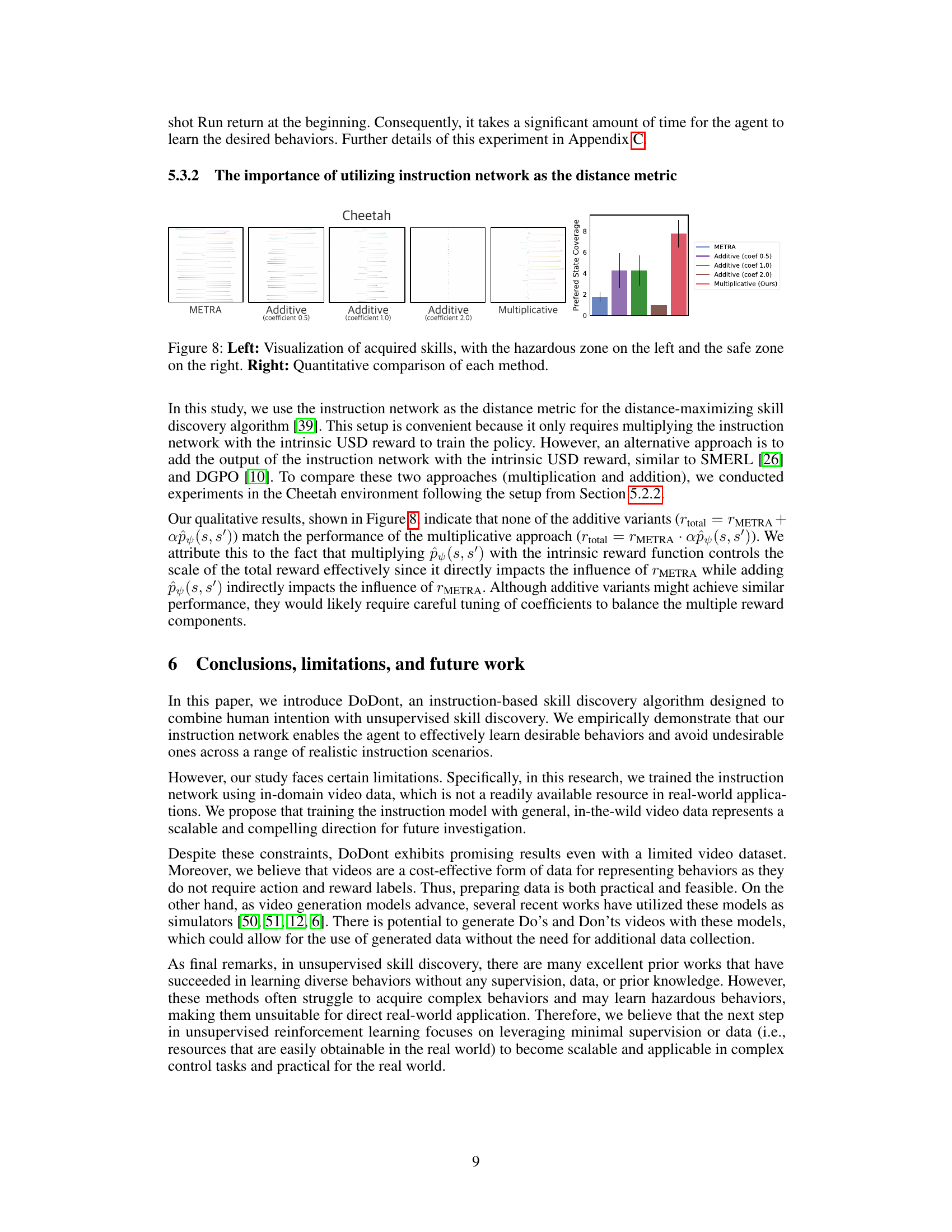

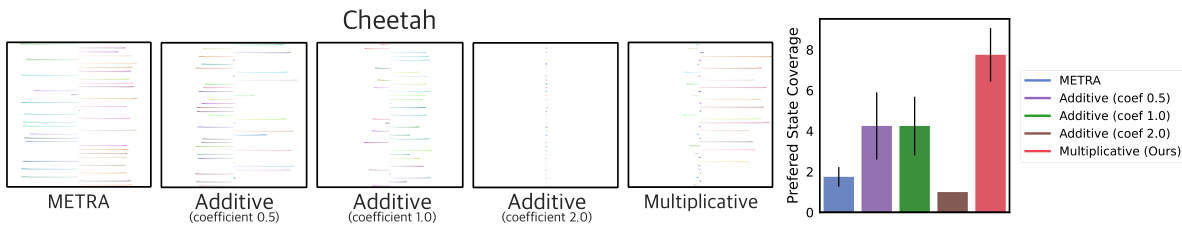

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of different methods for learning skills, specifically focusing on the ability to avoid hazardous areas while learning diverse behaviors. The left side presents visual representations of learned skills for each method (METRA, Additive methods with varying coefficients, and the proposed Multiplicative method). Each visualization shows trajectories, possibly color-coded to indicate different skills learned. The right side offers a quantitative comparison of the methods concerning ‘Preferred State Coverage’, which likely reflects the proportion of time agents spend in the safe zone versus the hazardous zone. This showcases how effectively each method uses an instruction network to guide learning toward safe and desirable behaviors.

read the caption

Figure 8: Left: Visualization of acquired skills, with the hazardous zone on the left and the safe zone on the right. Right: Quantitative comparison of each method.

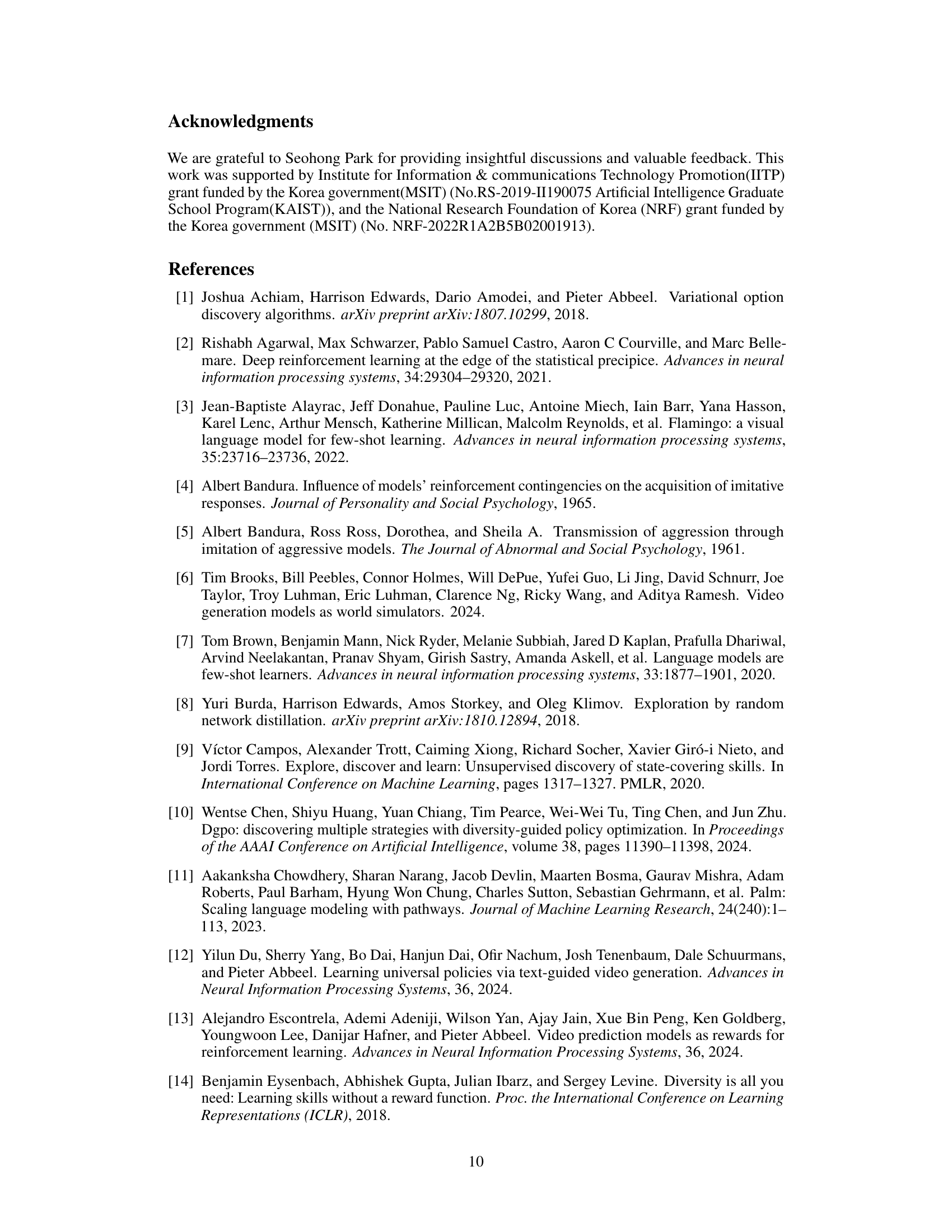

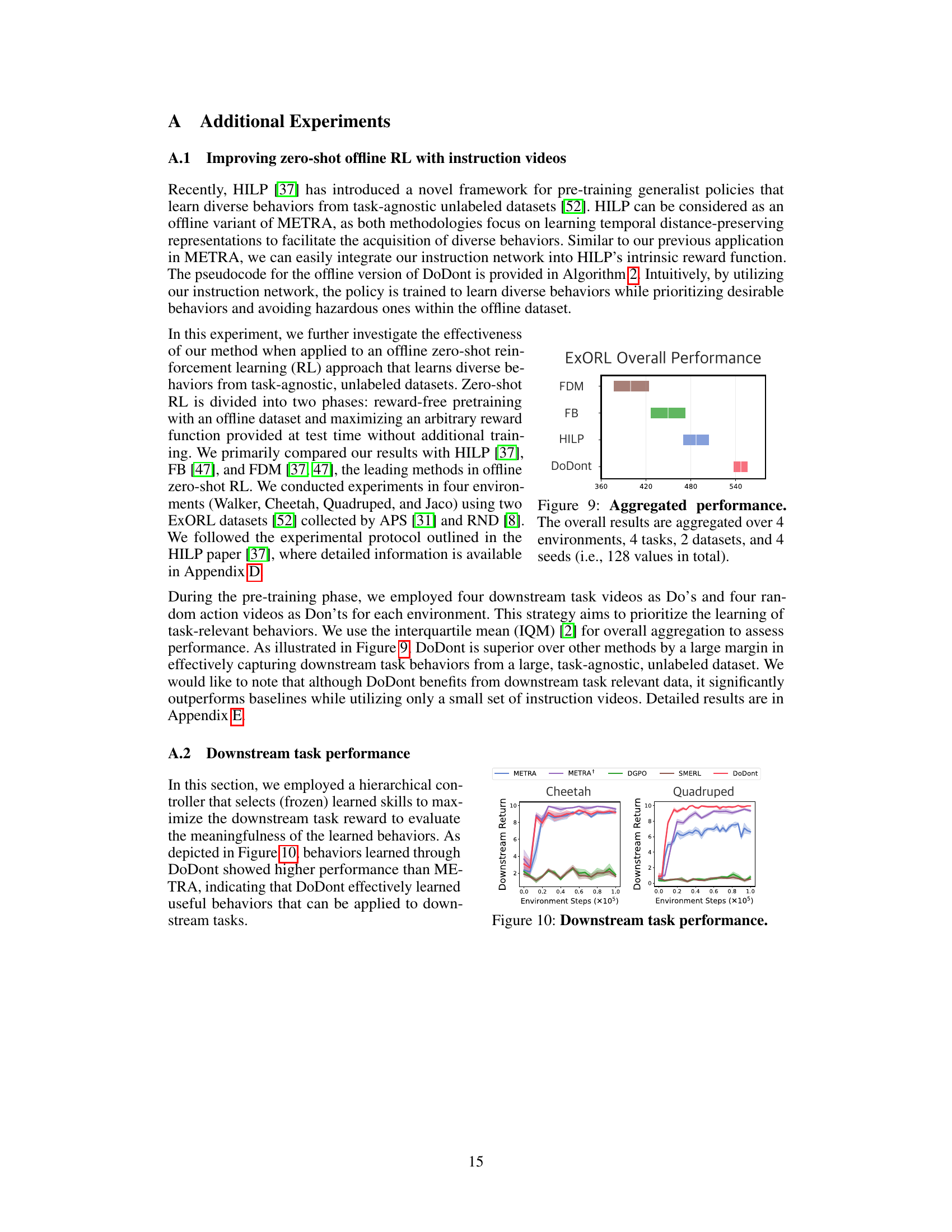

🔼 This figure shows a bar chart summarizing the overall performance of DoDont and three baseline methods (FDM, FB, HILP) across various environments, tasks, and datasets. The performance is aggregated across 128 individual trials (4 environments x 4 tasks x 2 datasets x 4 seeds). DoDont significantly outperforms the baselines.

read the caption

Figure 9: Aggregated performance. The overall results are aggregated over 4 environments, 4 tasks, 2 datasets, and 4 seeds (i.e., 128 values in total).

🔼 This figure shows the results of the DoDont algorithm on Cheetah and Quadruped locomotion tasks. The left side displays graphs comparing DoDont’s performance to other methods (METRA, METRA+, DGPO, and SMERL) in terms of state coverage and zero-shot task reward over training time. The right side provides a visual comparison between the instruction videos used to train DoDont (videos showing desirable ‘Do’ behaviors), and the types of locomotion skills the algorithm learns. This visual comparison highlights that DoDont learns diverse and complex behaviors, rather than simply mimicking the specific behaviors shown in the training videos.

read the caption

Figure 3: Left: State coverage and zero-shot task reward for Cheetah and Quadruped. Right: Visualization of Do videos in our instruction video dataset and learned skills by DoDont. We are able to observe that DoDont does not simply mimic instruction videos but extracts desirable behaviors (e.g., run) from the videos and learn diverse skills.

More on tables

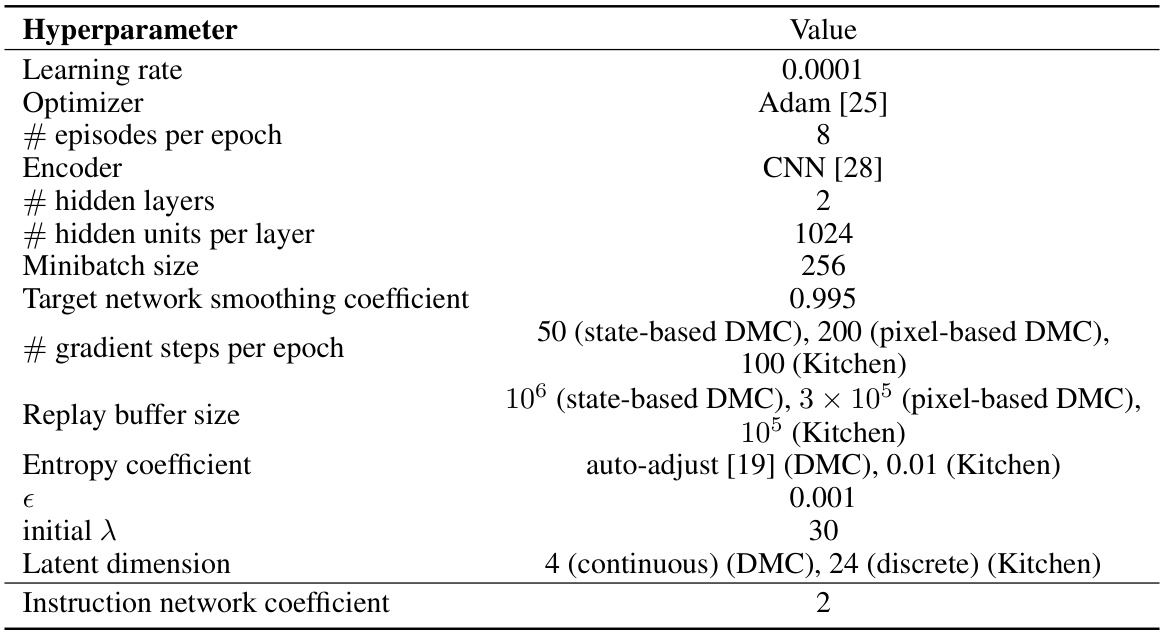

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used in the online version of the DoDont algorithm. Most values are taken directly from the METRA algorithm, with only one additional hyperparameter added for the instruction network. The table shows the hyperparameter name, and its corresponding value. Values may differ based on the environment (DMC or Kitchen) and whether the environment uses state-based or pixel-based inputs.

read the caption

Table 2: Hyperparameters used in Online DoDont. We adopt default hyperparameters from METRA [39], introducing only one additional hyperparameter.

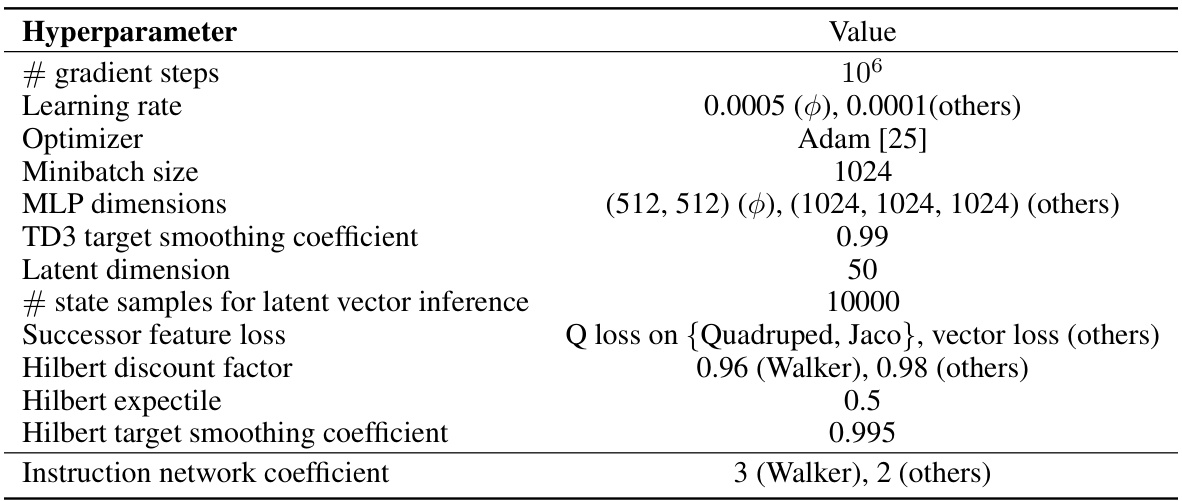

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used in the offline version of the DoDont algorithm. Most values are adopted directly from the HILP algorithm, with only one additional hyperparameter introduced by DoDont for the instruction network. The table details hyperparameters controlling learning rate, optimizer, minibatch size, network architecture, target network smoothing, latent dimensions, sampling strategy for latent vector inference, loss functions, discount and expectile values for Hilbert space calculations, target smoothing, and the instruction network coefficient.

read the caption

Table 3: Hyperparameters used in Offline DoDont. We adopt default hyperparameters from HILP [37], introducing only one additional hyperparameter.

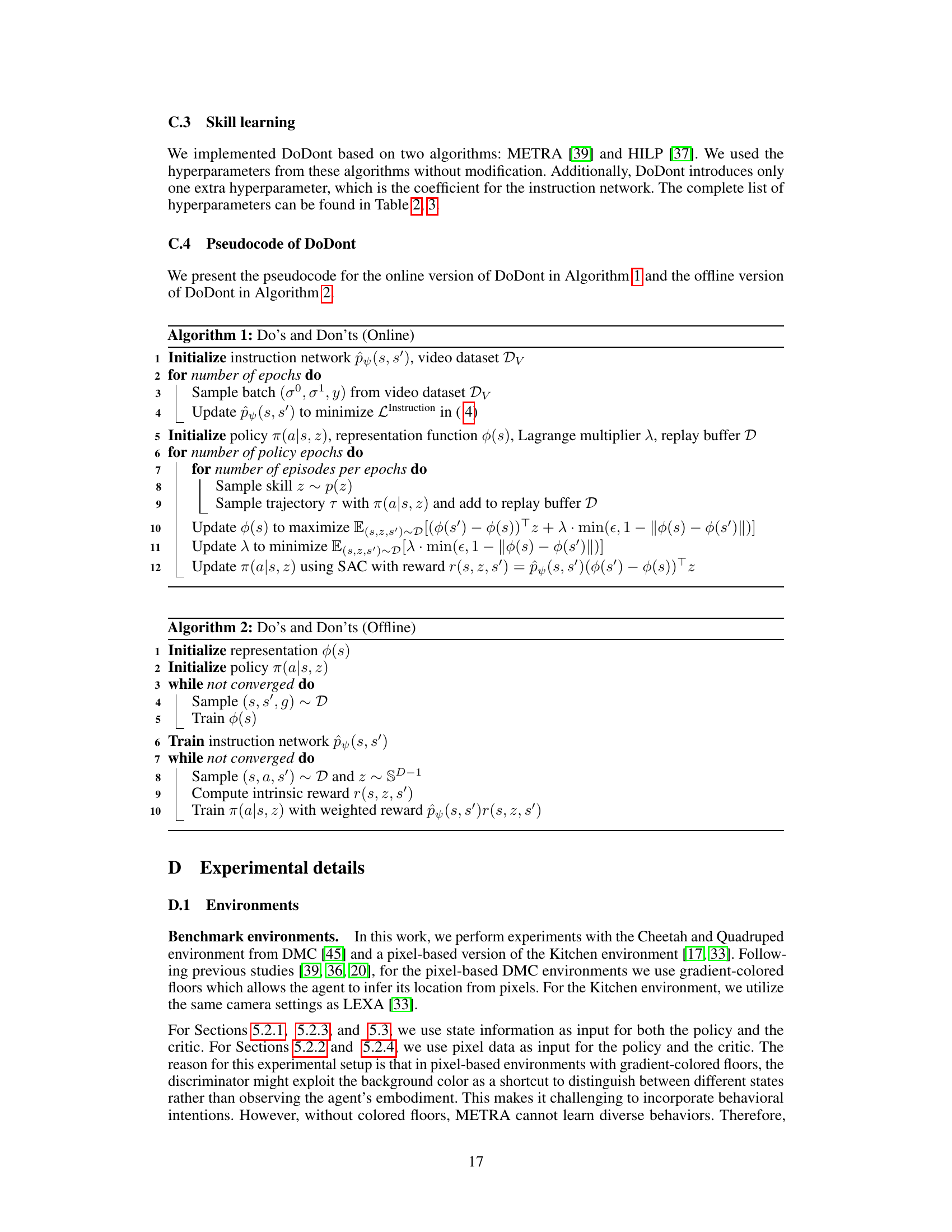

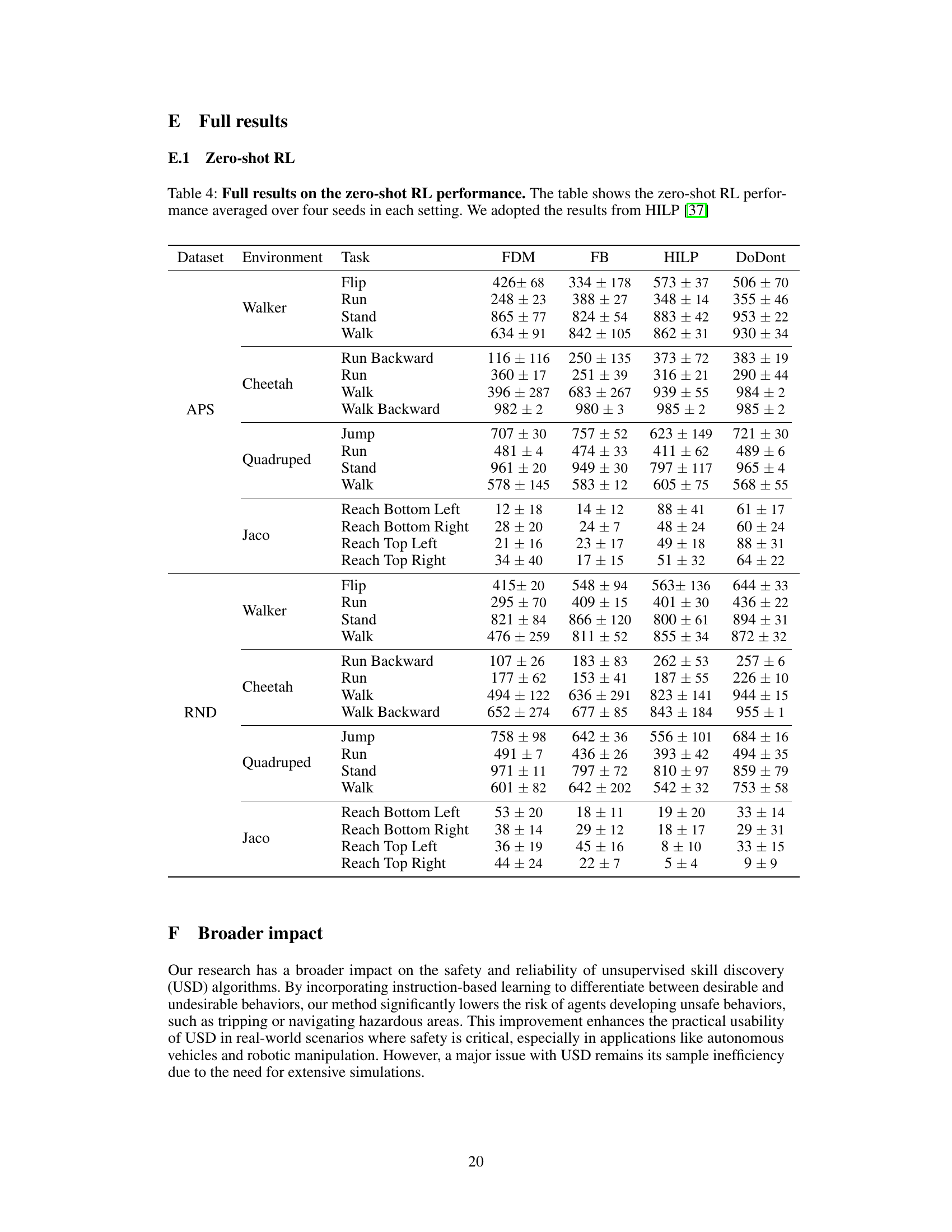

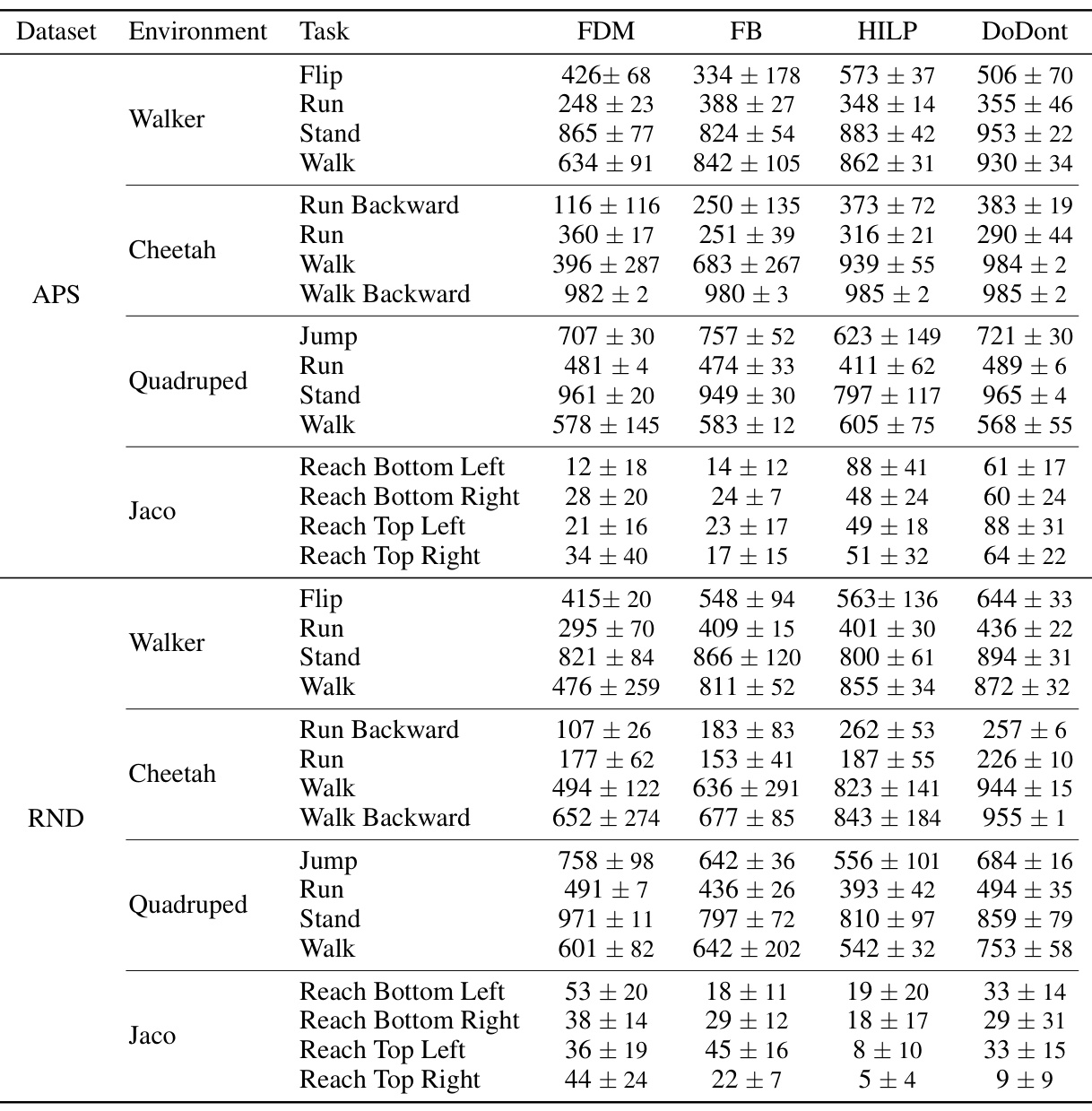

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive comparison of zero-shot reinforcement learning performance across different algorithms (FDM, FB, HILP, and DoDont) on various locomotion and manipulation tasks. The results are averaged over four random seeds for each setting, providing statistical robustness. The tasks include running, walking, standing, jumping, and reaching in different directions for both cheetah and quadruped robots, as well as reaching tasks for Jaco. The algorithms are evaluated on two datasets (APS and RND) to assess the generalization performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Full results on the zero-shot RL performance. The table shows the zero-shot RL performance averaged over four seeds in each setting. We adopted the results from HILP [37]

Full paper#