TL;DR#

Reinforcement learning (RL) agents often struggle with adapting to new tasks quickly. Model-based RL, which learns a world model, promises transferability but suffers from compounding errors in long-horizon predictions. Successor features offer an alternative by modeling a policy’s long-term state occupancy, reducing evaluation to linear regression but their policy dependence hinders optimization. This problem limits effective generalization across various tasks.

DiSPOs, Distributional Successor Features for Zero-Shot Policy Optimization, addresses this. It learns a distribution of successor features from offline data, enabling efficient zero-shot policy optimization for new reward functions. Using diffusion models, DiSPOs avoid compounding errors and achieve superior performance across various simulated robotics tasks, demonstrating theoretical and empirical efficacy for transferable RL models. This approach significantly improves transfer efficiency and generalization in RL.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces DiSPOs, a novel approach to transfer learning in reinforcement learning that overcomes the limitations of existing methods. It offers a solution to the long-standing challenge of compounding error in model-based RL and enables zero-shot policy optimization. This opens new avenues for developing more generalizable and efficient RL agents, particularly relevant in the context of offline RL and multi-task learning.

Visual Insights#

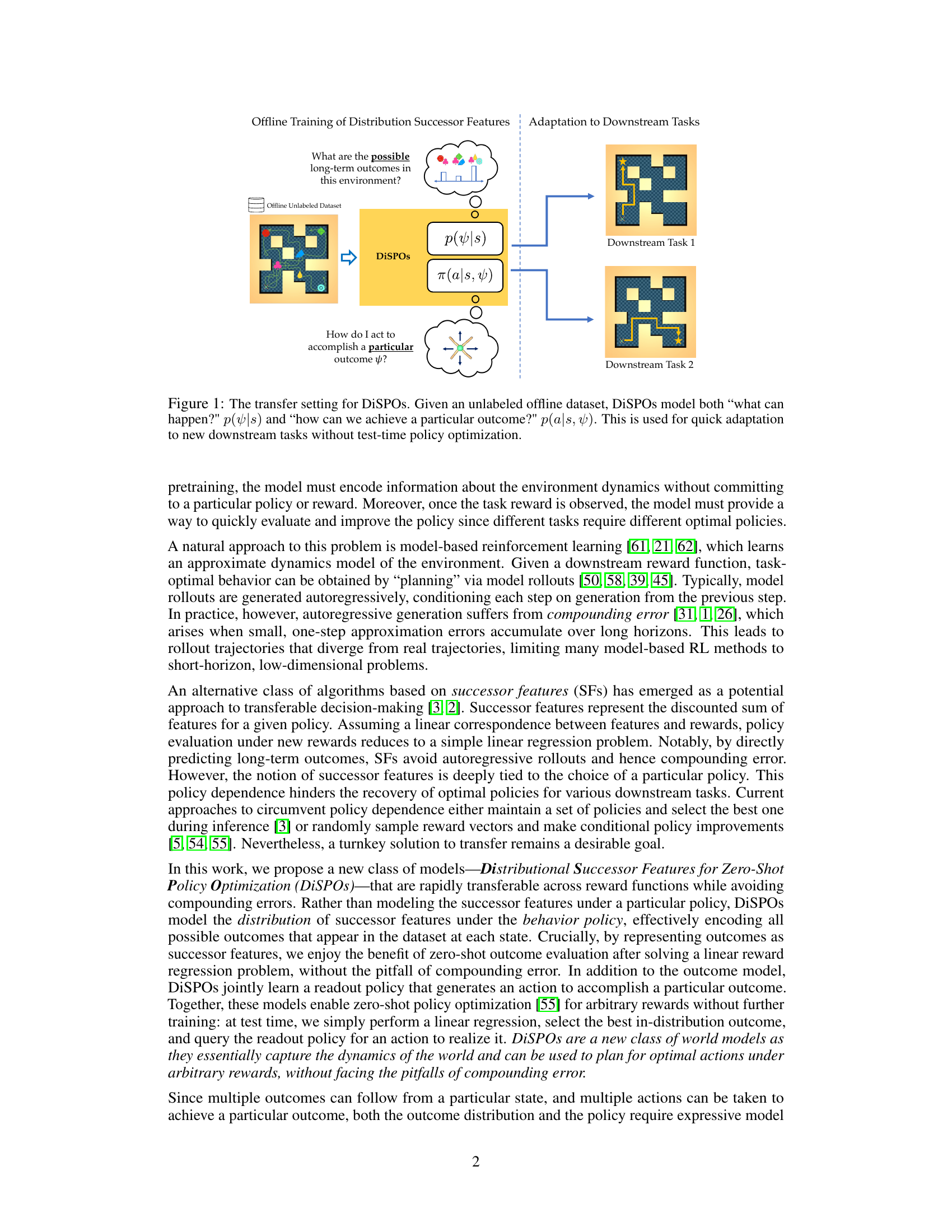

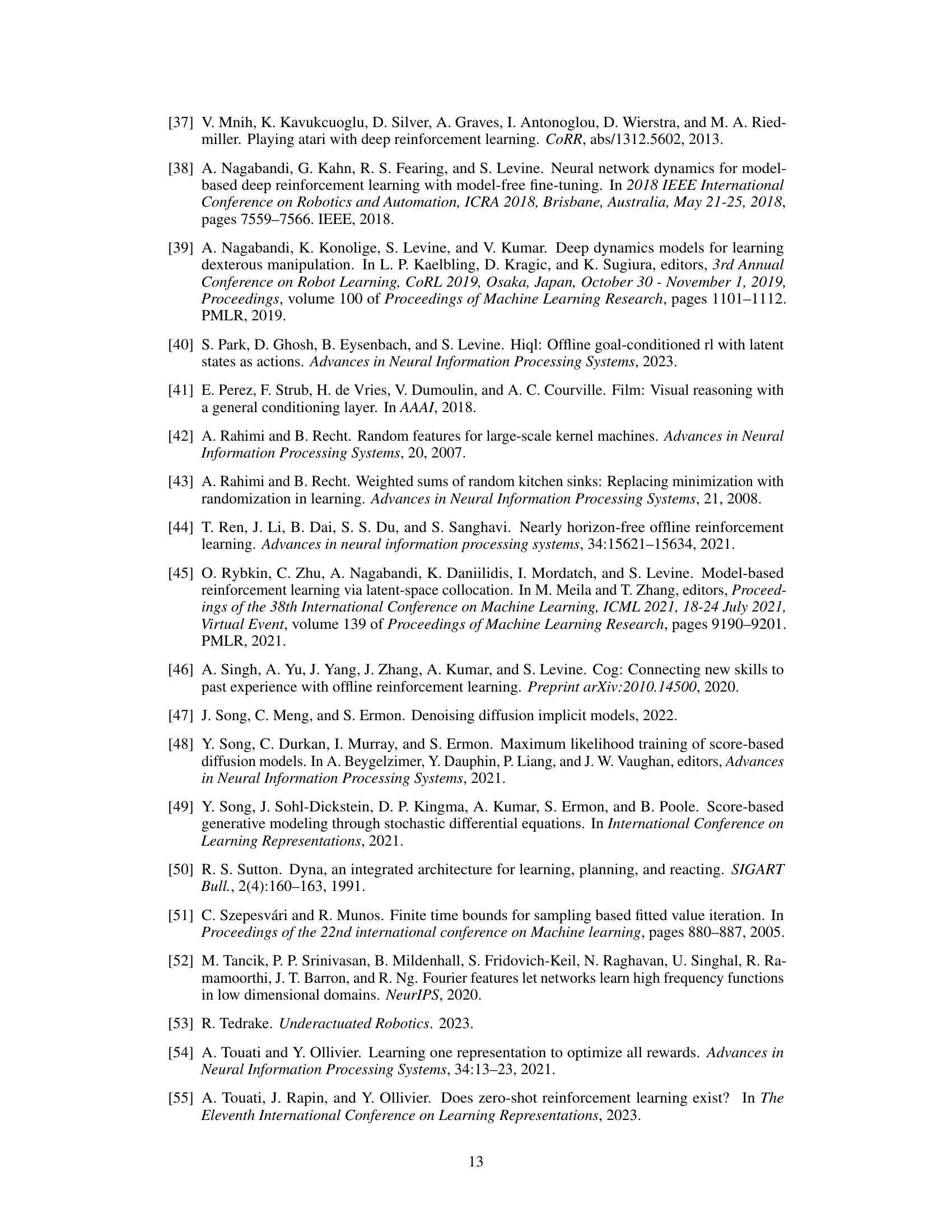

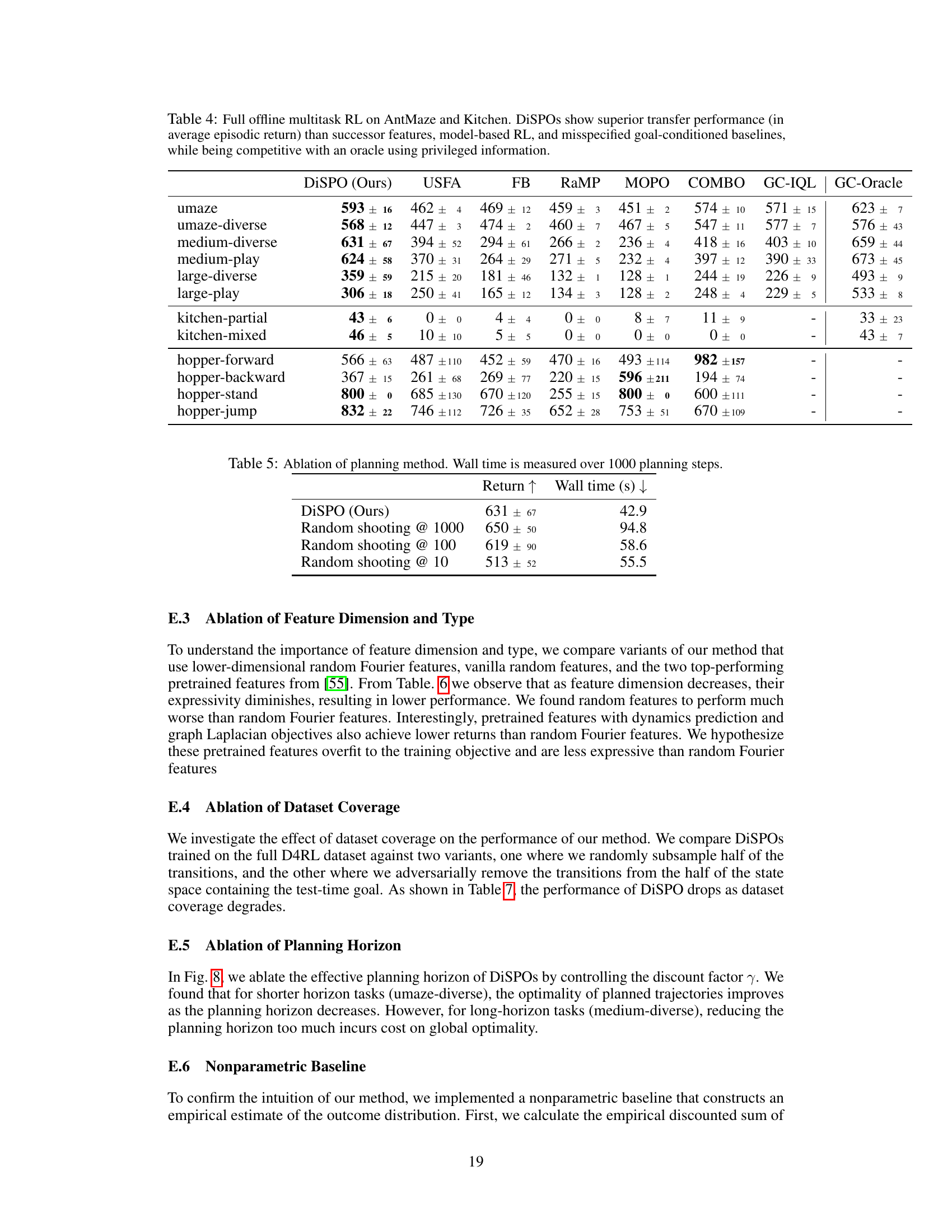

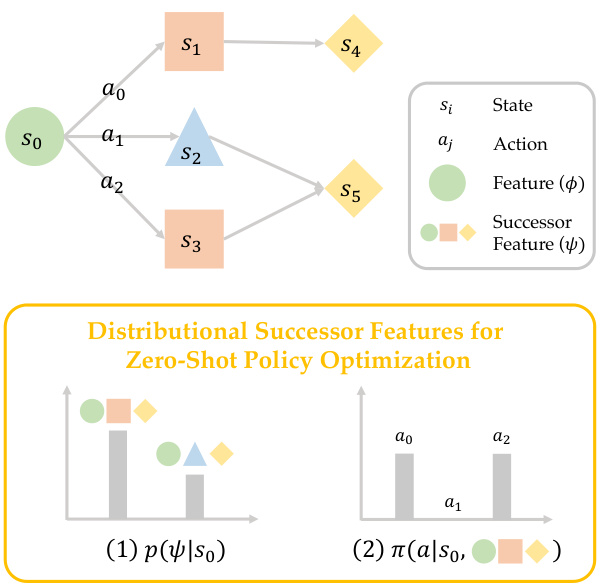

🔼 This figure illustrates the two-stage process of DiSPOs. First, an offline dataset is used to train the model to predict the distribution of possible long-term outcomes (successor features) in the environment, represented as p(ψ|s), and a policy π(a|s, ψ) that selects an action a to achieve a particular outcome ψ given a current state s. Second, this trained model is used to quickly adapt to new downstream tasks without requiring any further training or online policy optimization. New tasks are simply specified by providing a new reward function or a set of (s, r) samples.

read the caption

Figure 1: The transfer setting for DiSPOs. Given an unlabeled offline dataset, DiSPOs model both 'what can happen?' p(s) and 'how can we achieve a particular outcome?' p(a|s, ψ). This is used for quick adaptation to new downstream tasks without test-time policy optimization.

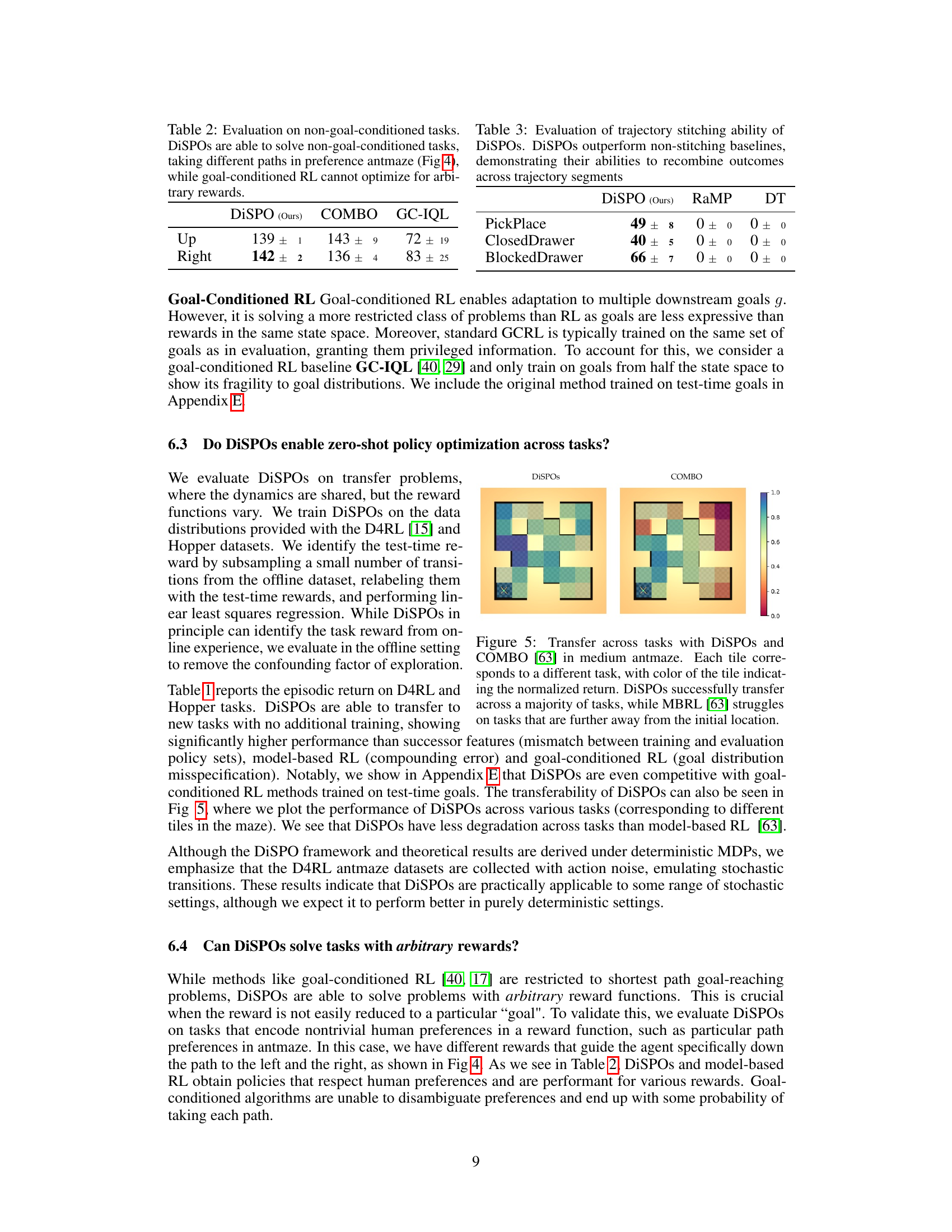

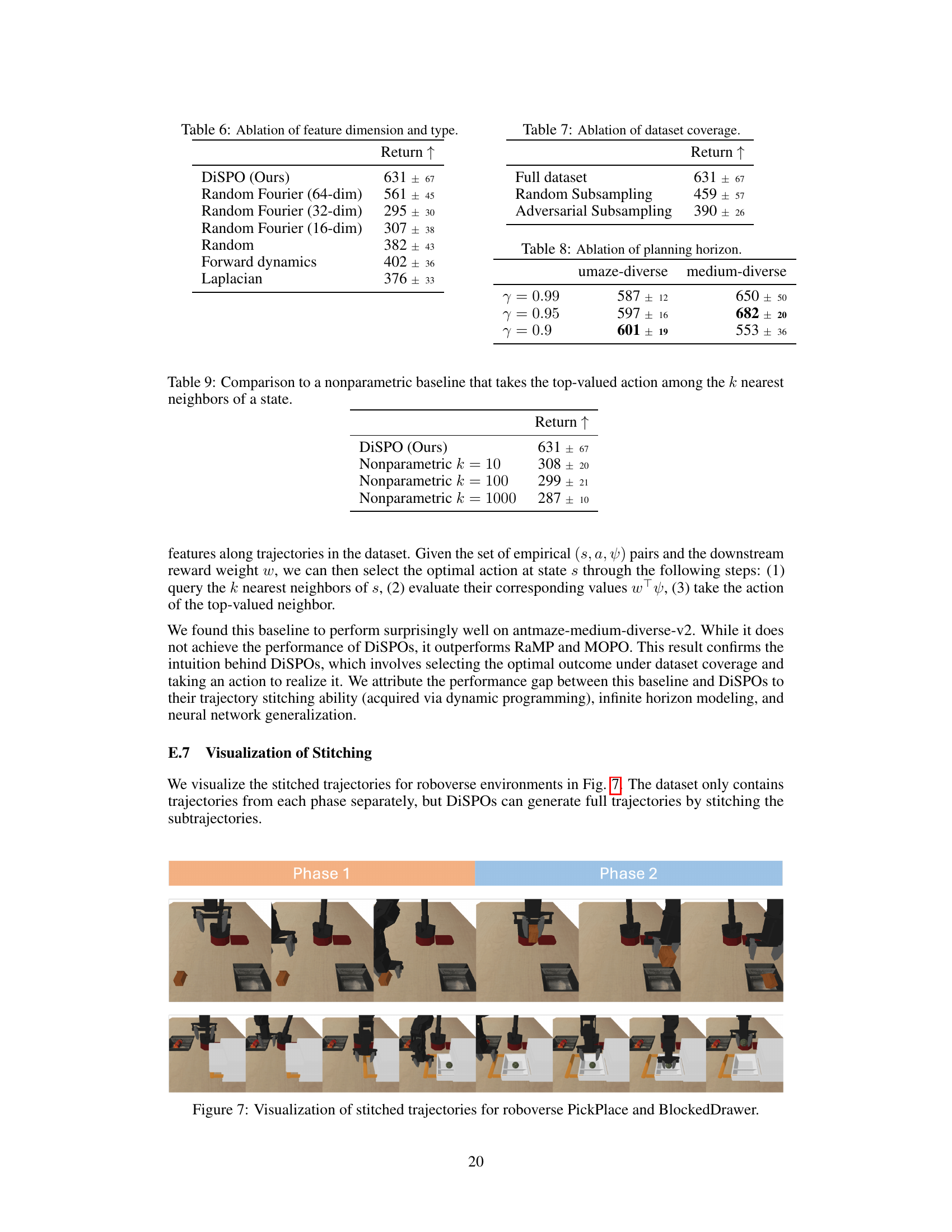

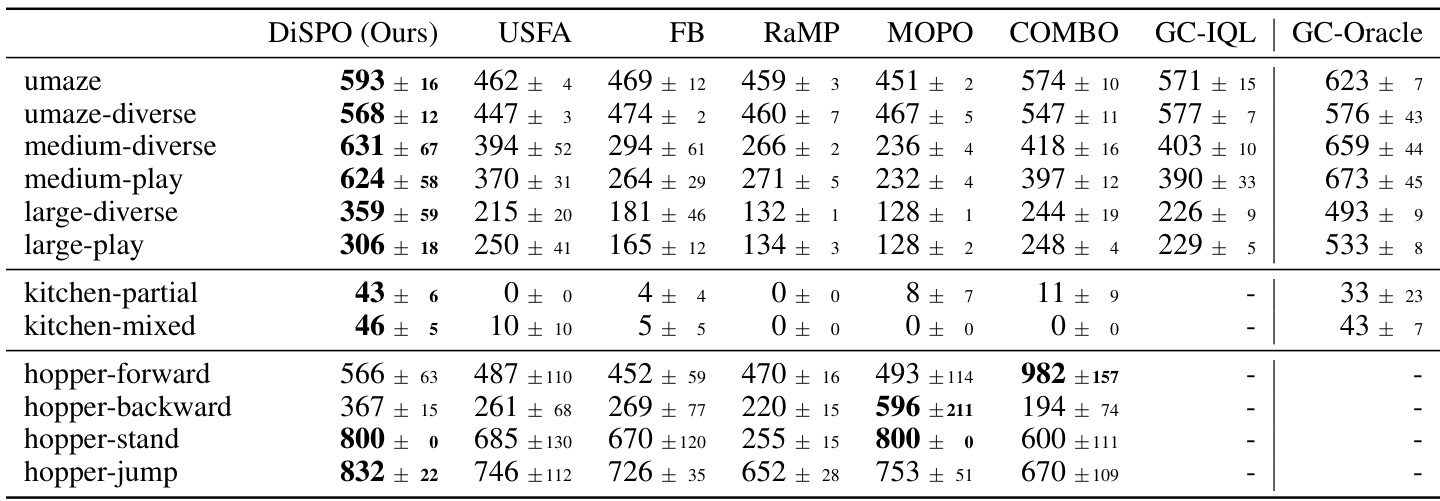

🔼 This table presents the average episodic return achieved by DiSPOs and several baseline methods across various AntMaze and Kitchen environments. DiSPOs consistently outperforms the baselines (USFA, FB, RaMP, MOPO, COMBO, GC-IQL) demonstrating its superior transfer learning capabilities in multitask reinforcement learning settings. The results highlight DiSPOs’ ability to generalize to unseen tasks without requiring further training.

read the caption

Table 1: Offline multitask RL on AntMaze and Kitchen. DiSPOs show superior transfer performance (in average episodic return) than successor features, model-based RL, and misspecified goal-conditioned baselines.

In-depth insights#

DiSPOs: Zero-Shot RL#

Distributional Successor Features for Zero-Shot Policy Optimization (DiSPOs) offers a novel approach to tackling the challenge of zero-shot reinforcement learning. The core idea revolves around learning a distribution of successor features from an offline dataset, rather than relying on a single policy. This distributional approach allows DiSPOs to avoid the compounding errors inherent in model-based RL methods that utilize autoregressive rollouts. By modeling the distribution of possible long-term outcomes, DiSPOs can efficiently adapt to new reward functions without requiring extensive test-time optimization. Zero-shot adaptation is achieved by combining the learned outcome distribution with a readout policy that determines actions to achieve desired outcomes. The framework is theoretically grounded, showing convergence to optimal policies under specific conditions. Empirical results demonstrate DiSPOs’ efficacy across various simulated robotic tasks, significantly outperforming existing methods in zero-shot transfer settings. A key strength lies in its ability to perform trajectory stitching, effectively combining parts of different trajectories in the offline dataset to reach optimal outcomes, which is crucial for data efficiency. Although limited to deterministic MDPs in its theoretical analysis, its practical application showcases promising results in more complex scenarios, hinting at the potential of DiSPOs in achieving robust and generalizable reinforcement learning.

Diffusion Model Use#

The utilization of diffusion models in the paper presents a novel approach to policy optimization in reinforcement learning. By modeling the distribution of successor features using diffusion models, the approach elegantly sidesteps the compounding error often associated with autoregressive methods. This is a significant advantage, enabling effective planning and policy evaluation over long horizons. The method’s ability to sample from the distribution of outcomes, rather than relying on point estimates, provides robustness and improved generalization across diverse tasks. The integration with guided diffusion further streamlines the policy optimization process, transforming it into a form of guided sampling, accelerating both training and inference. This fusion of diffusion models with the successor feature framework represents a powerful innovation, offering a practical and theoretically grounded method for transfer learning in reinforcement learning. The empirical results demonstrate that this approach offers significant performance improvements across various simulated robotics domains, validating the practical efficacy of the proposed method. However, further investigation into the scalability and generalization abilities to more complex, real-world scenarios would provide valuable insight and broaden the understanding of the method’s capabilities.

Offline RL Transfer#

Offline reinforcement learning (RL) transfer tackles the challenge of adapting RL agents trained on offline datasets to new, unseen tasks. A core issue is the inherent policy dependence of many offline RL methods, meaning that policies optimized for one task may not generalize well to another. This necessitates approaches that learn transferable representations of the environment’s dynamics, enabling adaptation without extensive retraining or online interaction. Successor features, which encode long-term state occupancy, and distributional methods, which model the distribution of possible outcomes, are two promising avenues for improving transferability. Effective offline RL transfer requires addressing the compounding error that arises from sequential modeling, and methods that directly model long-term outcomes offer a promising advantage. The use of generative models, such as diffusion models, allows for the efficient sampling of potential future outcomes, enabling rapid policy adaptation for new tasks. Ultimately, successful offline RL transfer depends on the ability to disentangle task-specific reward functions from generalizable environment dynamics within a limited offline dataset.

Trajectory Stitching#

Trajectory stitching, in the context of offline reinforcement learning, addresses the challenge of learning optimal policies from datasets that may contain incomplete or fragmented trajectories. Standard offline RL methods often struggle with such data, as they rely on complete sequences of state-action-reward transitions to estimate value functions and optimize policies. Trajectory stitching aims to overcome this limitation by intelligently combining shorter, disconnected trajectory segments to construct more complete representations of the agent’s behavior and the environment’s dynamics. This is crucial because it allows learning from data that might otherwise be unusable, effectively increasing the amount of useful information extracted from the dataset. The success of trajectory stitching hinges on the ability of the model to identify and appropriately connect relevant trajectory segments, often by leveraging features or representations that capture meaningful relationships between states across time. This ability depends on the expressiveness of the models used and often requires advanced techniques such as distributional representations or generative models capable of capturing the inherent uncertainty in the offline data. Successfully stitching trajectories can significantly improve sample efficiency and lead to better policy performance in offline RL. However, it introduces new challenges related to choosing appropriate stitching criteria and preventing the creation of artificial or implausible trajectories. The careful selection of features, the design of stitching algorithms, and the incorporation of uncertainty estimation are all critical factors determining the effectiveness of this powerful technique.

Future Work: Online RL#

Extending DiSPOs to the online reinforcement learning (RL) setting presents a significant and exciting avenue for future research. The current offline nature of DiSPOs, while demonstrating impressive zero-shot transfer capabilities, limits its applicability to dynamic environments where the reward function is not known beforehand and may change over time. Adapting the distributional successor feature learning to an online setting requires careful consideration of exploration-exploitation trade-offs. The agent needs to balance exploring the state-action space to update the outcome distribution and exploiting the currently learned distribution to maximize the immediate reward. Efficient online update mechanisms for the outcome and policy models are crucial. Methods based on incremental learning or recursive updates would minimize computational overhead and ensure that the model adapts promptly to changes in the environment. Furthermore, the challenge of handling non-stationarity in the online setting needs careful consideration. Novel approaches like online adaptation of the diffusion model, robust optimization methods against distribution shifts or incorporating techniques from continual learning could help handle the ever-evolving nature of the environment. Finally, rigorous theoretical analysis is needed to guarantee the convergence and performance of the online DiSPOs algorithm, establishing bounds on the regret or suboptimality compared to an oracle with full knowledge of the environment dynamics and reward function.

More visual insights#

More on figures

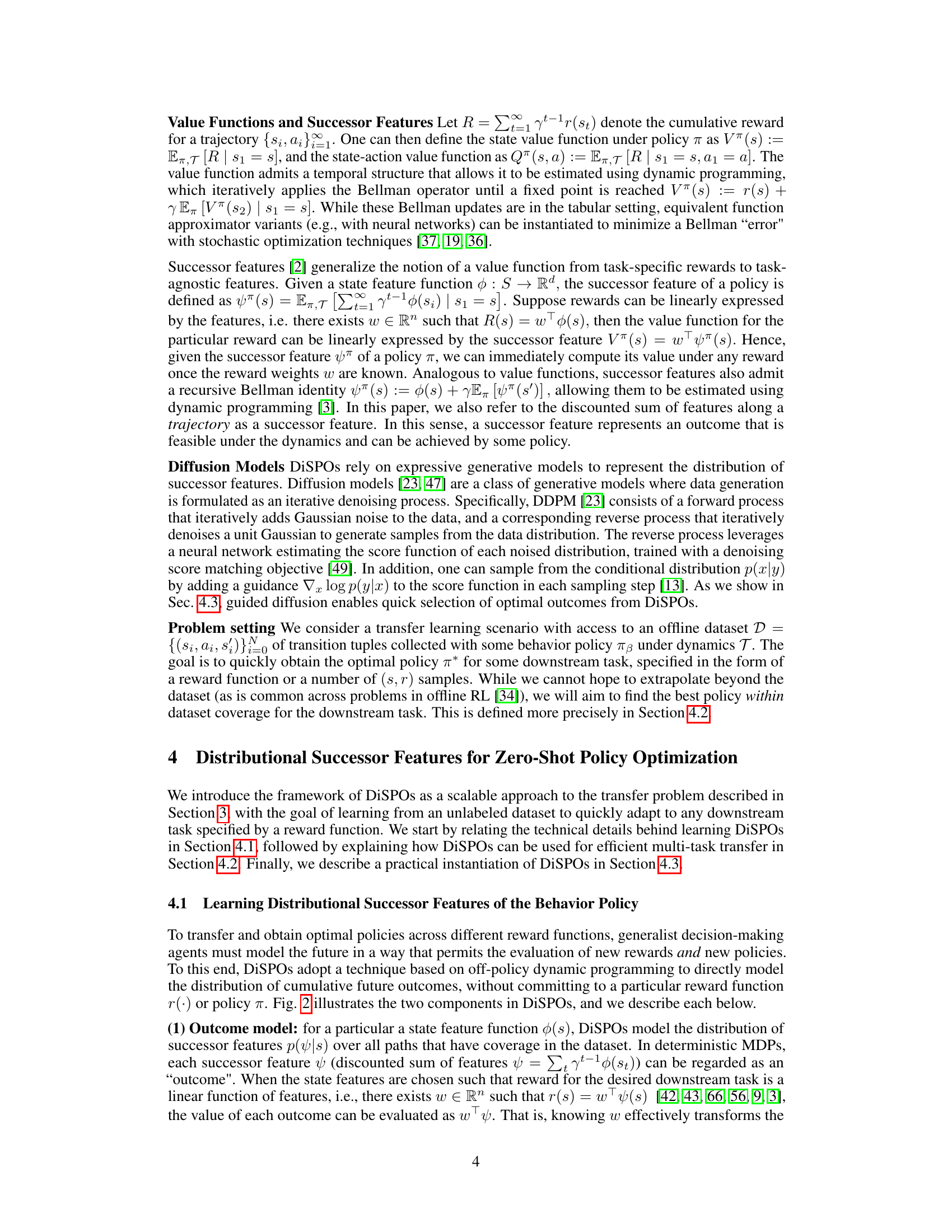

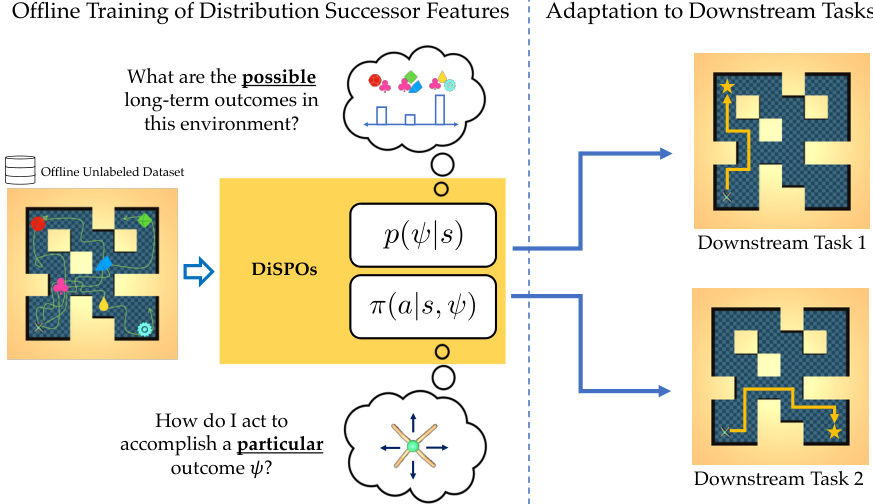

🔼 This figure illustrates a simple environment with states and actions. DiSPOs models the distribution of successor features p(ψ|s) for each state. It also learns a policy π(a|s,ψ) that maps states and successor features to actions. The goal is to predict and take actions to achieve specific desired long-term outcomes (successor features).

read the caption

Figure 2: DiSPOs for a simple environment. Given a state feature function '', DiSPOs learn a distribution of all possible long-term outcomes (successor features ψ) in the dataset p(ψ|s), along with a readout policy π(a|s, ψ) that takes an action a to realise ψ starting at state s.

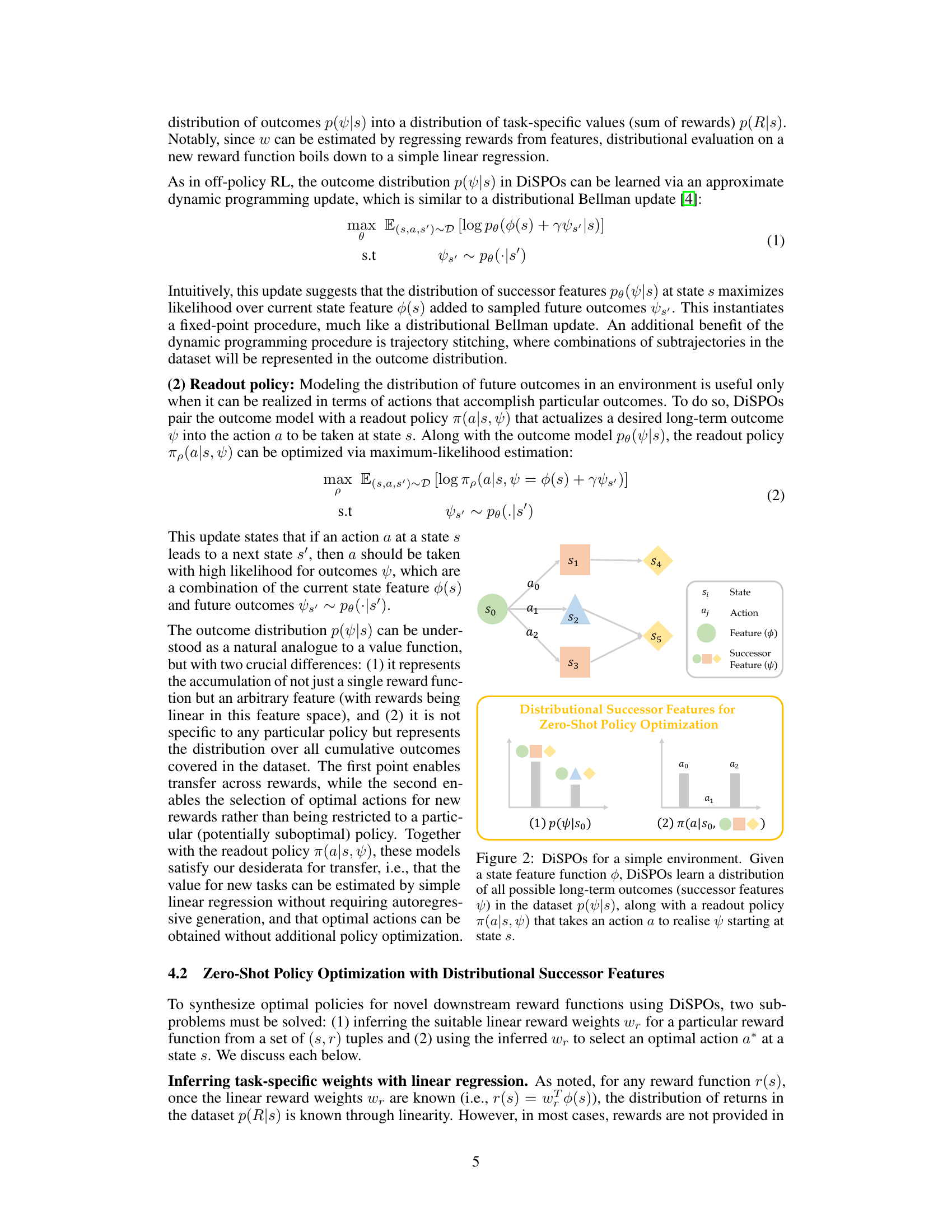

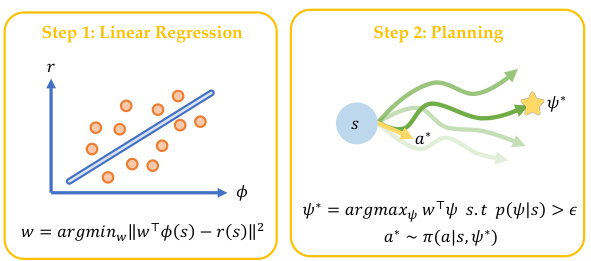

🔼 This figure illustrates the two-step process of zero-shot policy optimization using DiSPOs. First, linear regression is performed to infer the task-specific reward weights from the observed rewards and features in the dataset. Then, planning is conducted by searching for the optimal outcome (successor feature) with the highest expected reward, satisfying a data support constraint. Finally, the readout policy is used to determine the optimal action corresponding to that outcome.

read the caption

Figure 3: Zero-shot policy optimization with DiSPOs. Once a DiSPO is learned, the optimal action can be obtained by performing reward regression and searching for the optimal outcome under the dynamics to decode via the policy.

🔼 The figure illustrates the offline training process for DiSPOs. DiSPOs takes an offline dataset and learns both the possible long-term outcomes and the policies to achieve those outcomes. During testing, this model allows for quick adaptation to new downstream tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: The transfer setting for DiSPOs. Given an unlabeled offline dataset, DiSPOs model both 'what can happen?' p(s) and 'how can we achieve a particular outcome?' p(a|s, ψ). This is used for quick adaptation to new downstream tasks without test-time policy optimization.

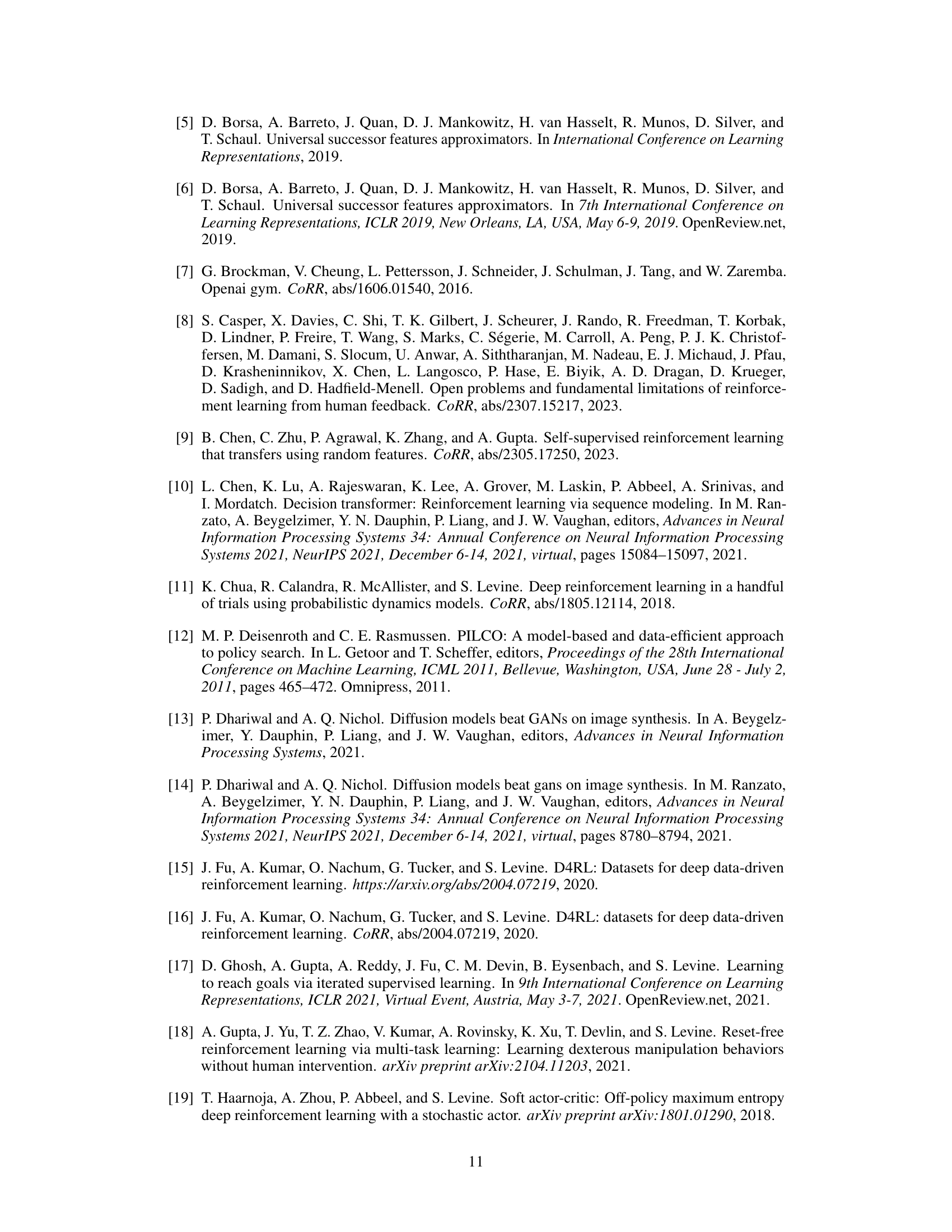

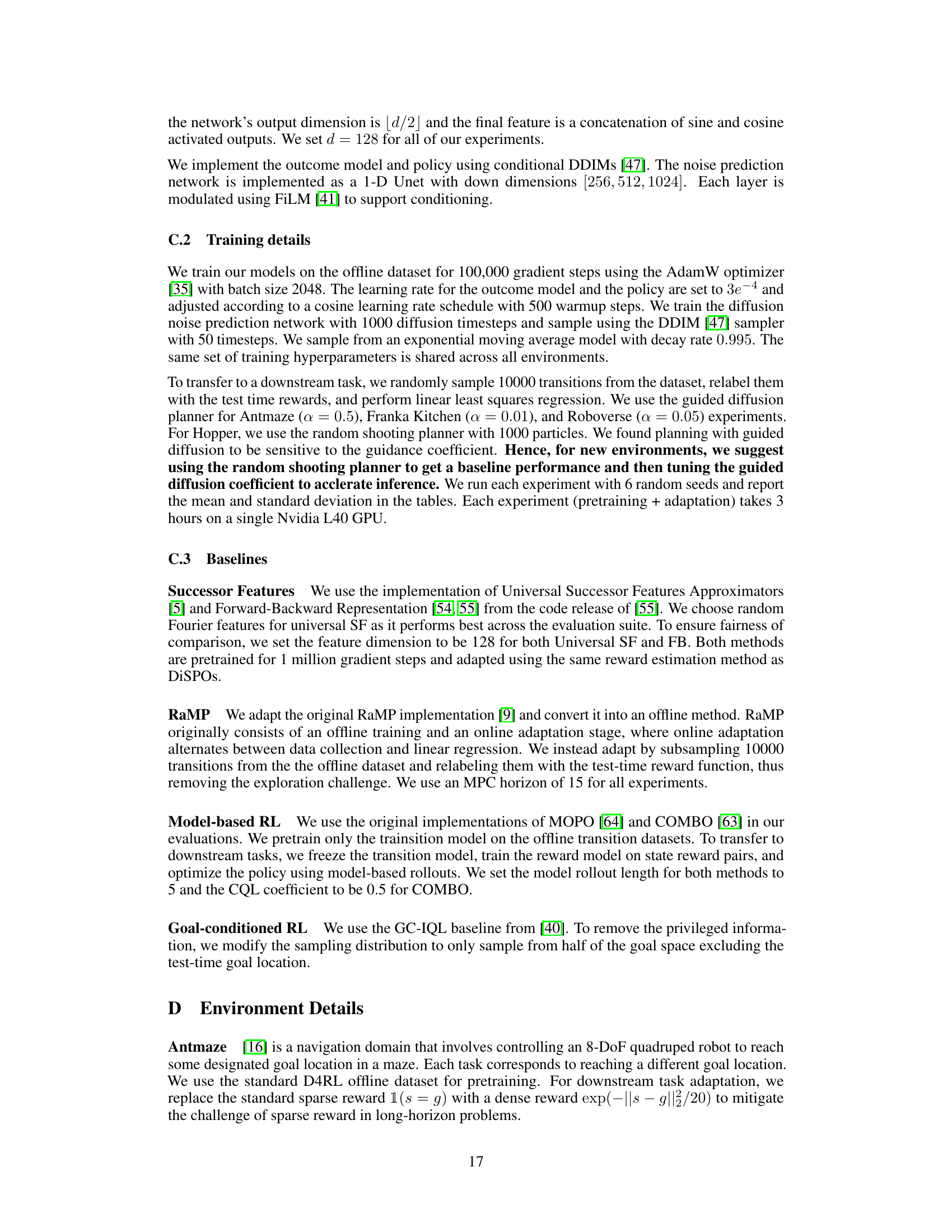

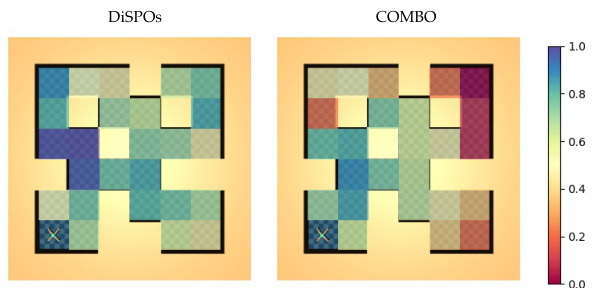

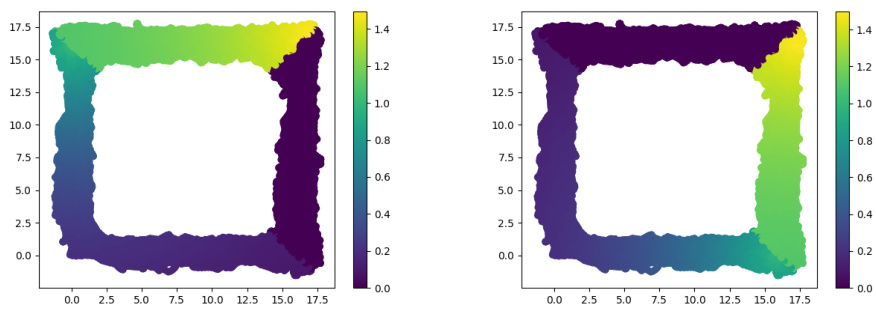

🔼 This figure compares the performance of DiSPOs and COMBO on various tasks in the AntMaze environment. Each colored tile represents a different task, with the color intensity reflecting the normalized return achieved by each method. DiSPOs demonstrates better transferability across diverse tasks compared to COMBO, especially those far from the starting location.

read the caption

Figure 5: Transfer across tasks with DiSPOs and COMBO [63] in medium antmaze. Each tile corresponds to a different task, with color of the tile indicating the normalized return. DiSPOs successfully transfer across a majority of tasks, while MBRL [63] struggles on tasks that are further away from the initial location.

🔼 This figure illustrates the components of DiSPOs in a simple environment. It shows how DiSPOs model the distribution of successor features (representing possible long-term outcomes) from a given state, alongside a policy that selects actions to achieve specific successor features. This dual modeling allows DiSPOs to efficiently adapt to new tasks by selecting the best outcome and corresponding action, avoiding computationally expensive test-time policy optimization.

read the caption

Figure 2: DiSPOs for a simple environment. Given a state feature function φ, DiSPOs learn a distribution of all possible long-term outcomes (successor features ψ) in the dataset p(ψ|s), along with a readout policy π(a|s, ψ) that takes an action a to realise ψ starting at state s.

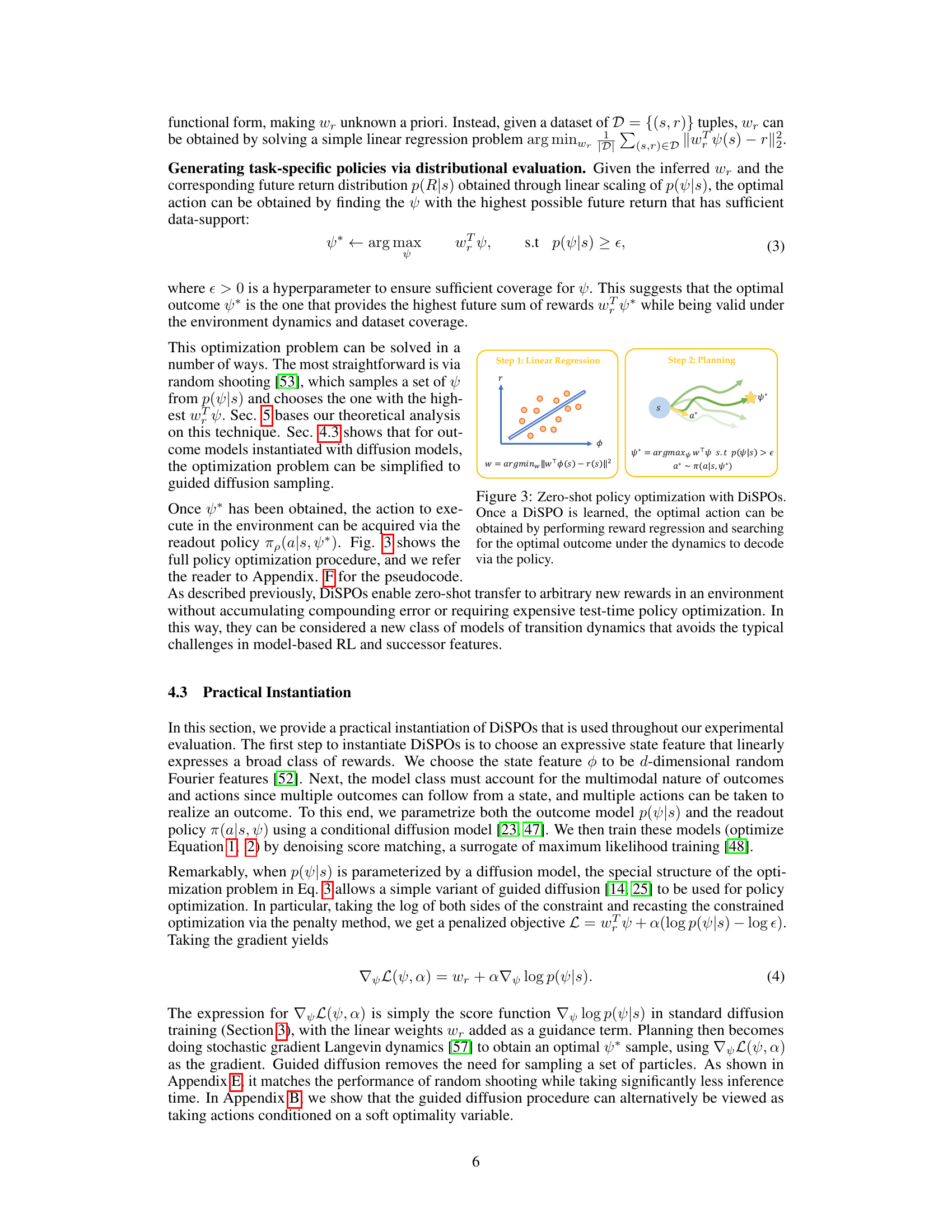

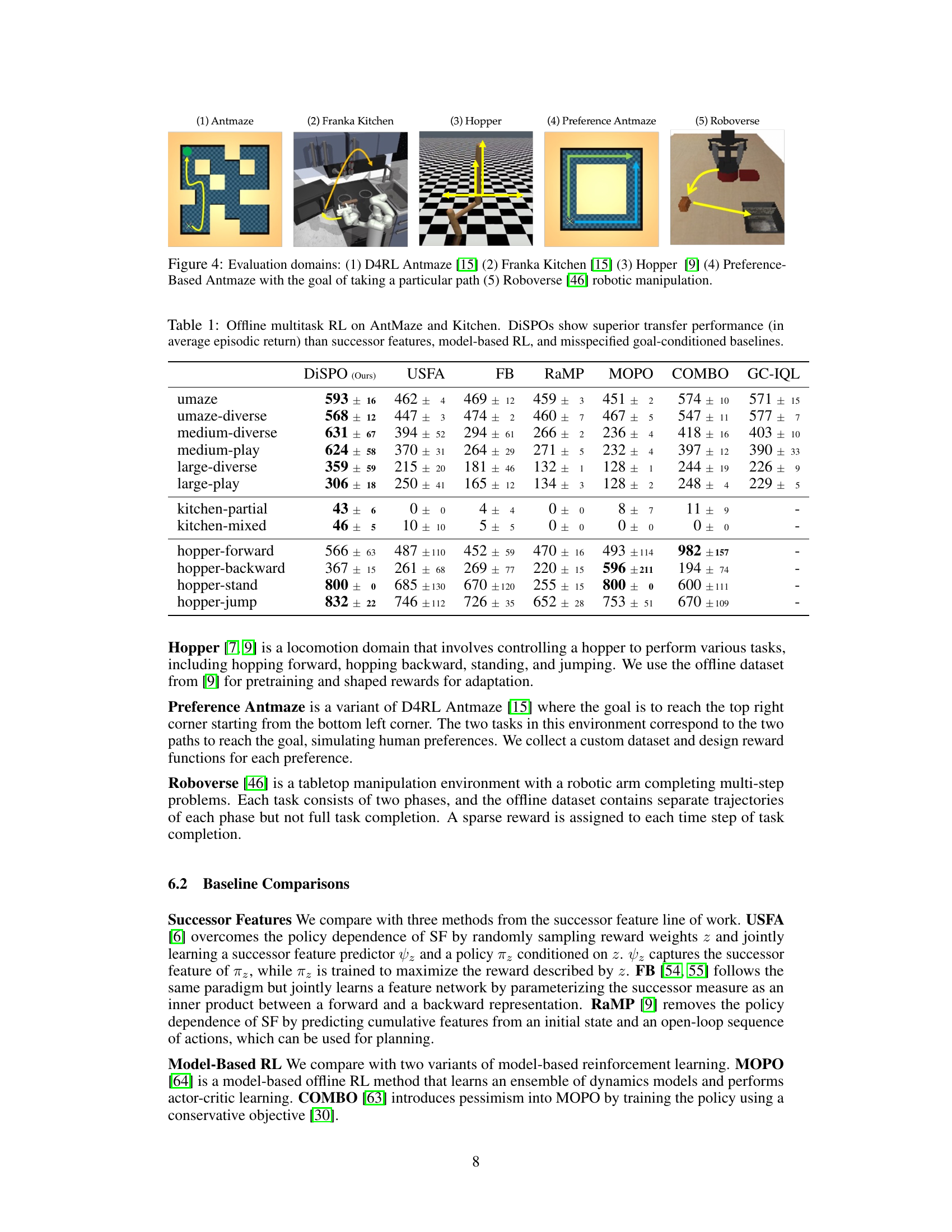

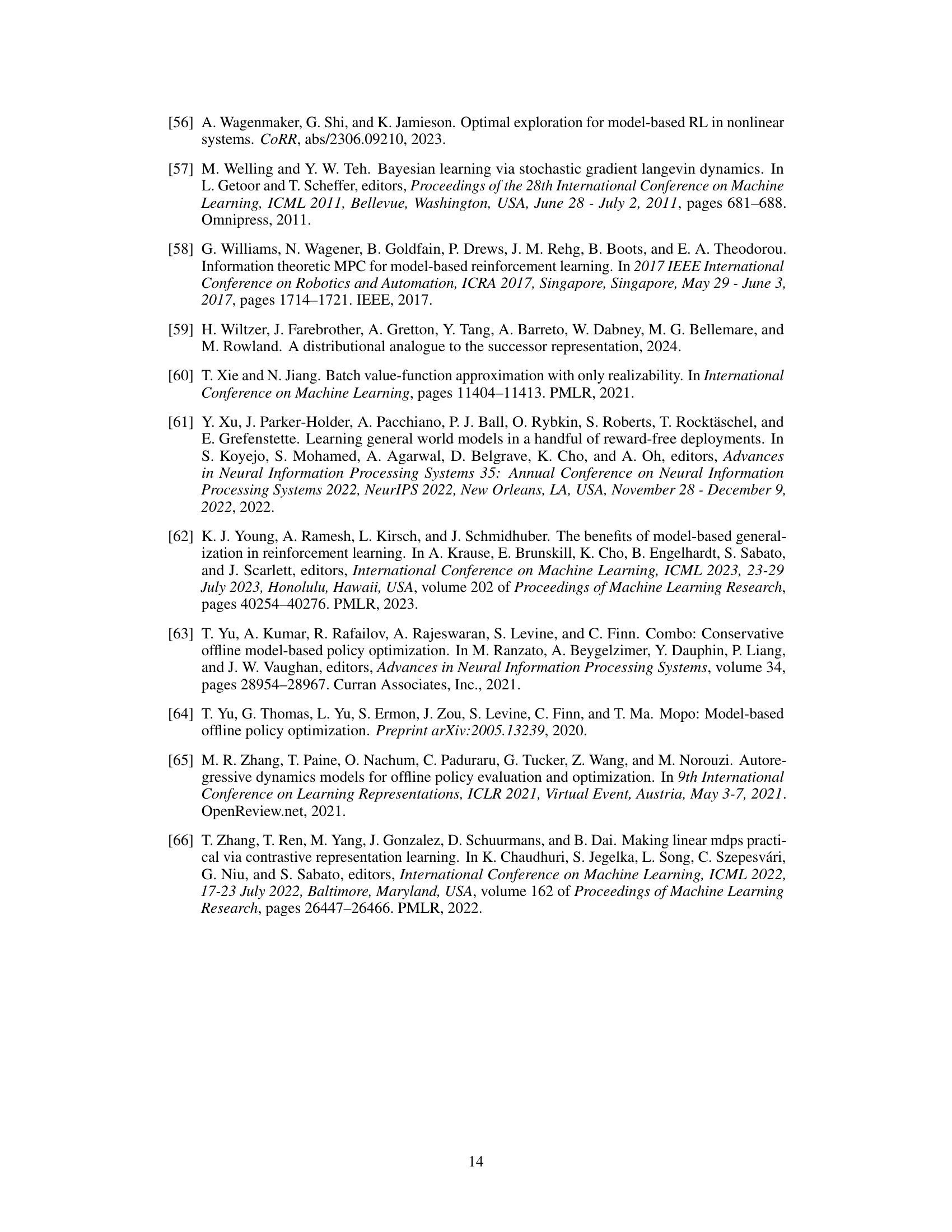

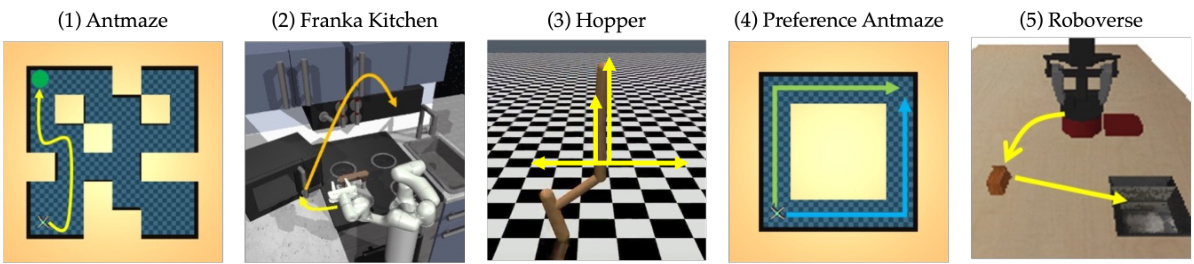

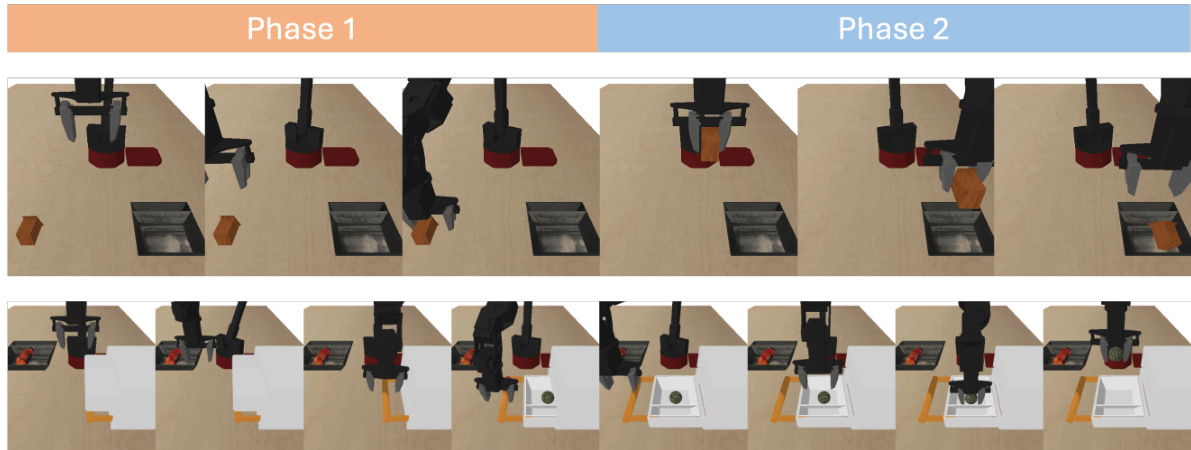

🔼 This figure showcases five different simulated robotics environments used to evaluate the DiSPOs model. Each environment presents unique challenges for reinforcement learning agents, testing various aspects of robot control and decision-making. These range from navigation tasks (Antmaze, Preference Antmaze) to manipulation tasks (Franka Kitchen, Roboverse) and locomotion (Hopper). The inclusion of a preference-based Antmaze highlights the model’s ability to handle tasks beyond simple goal-reaching.

read the caption

Figure 4: Evaluation domains: (1) D4RL Antmaze [15] (2) Franka Kitchen [15] (3) Hopper [9] (4) Preference-Based Antmaze with the goal of taking a particular path (5) Roboverse [46] robotic manipulation.

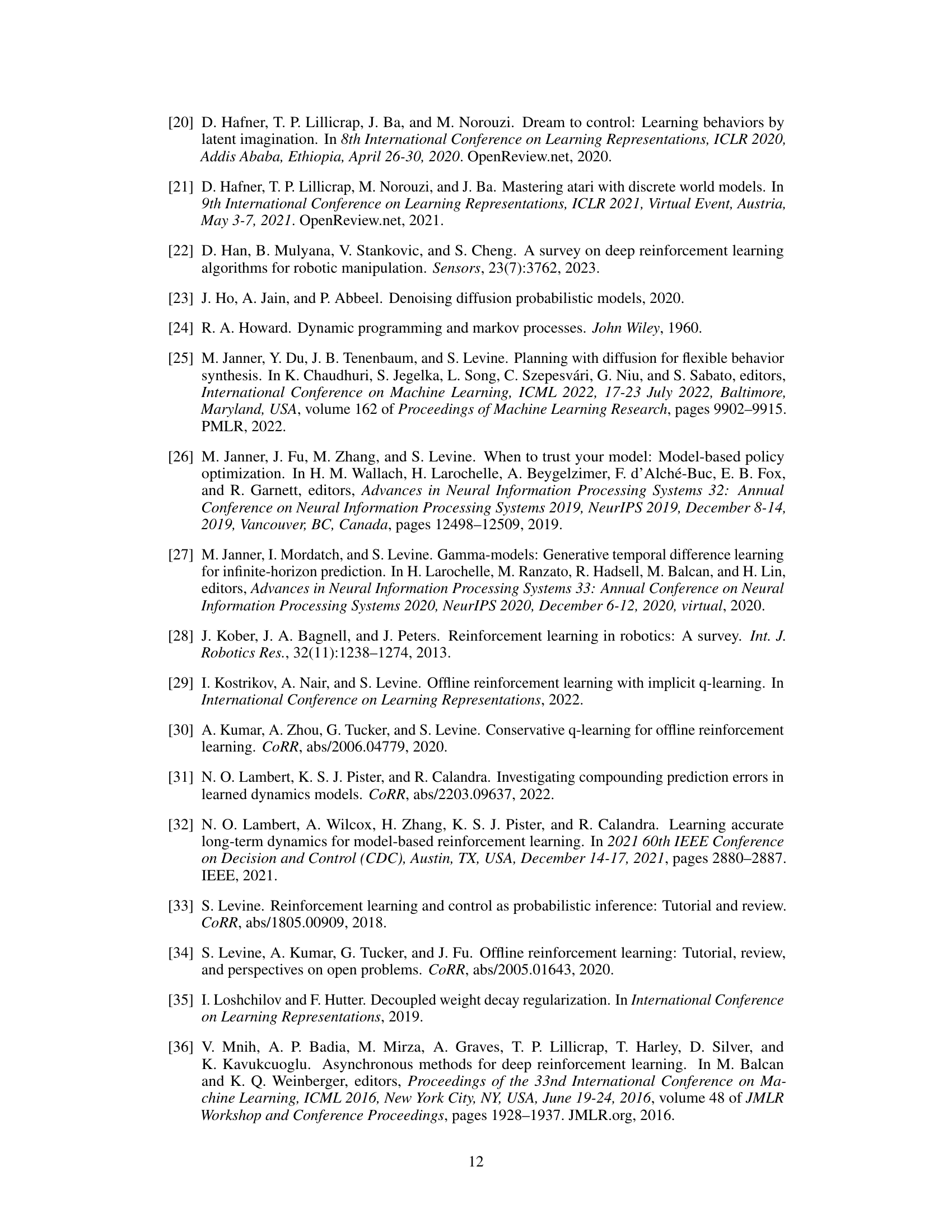

More on tables

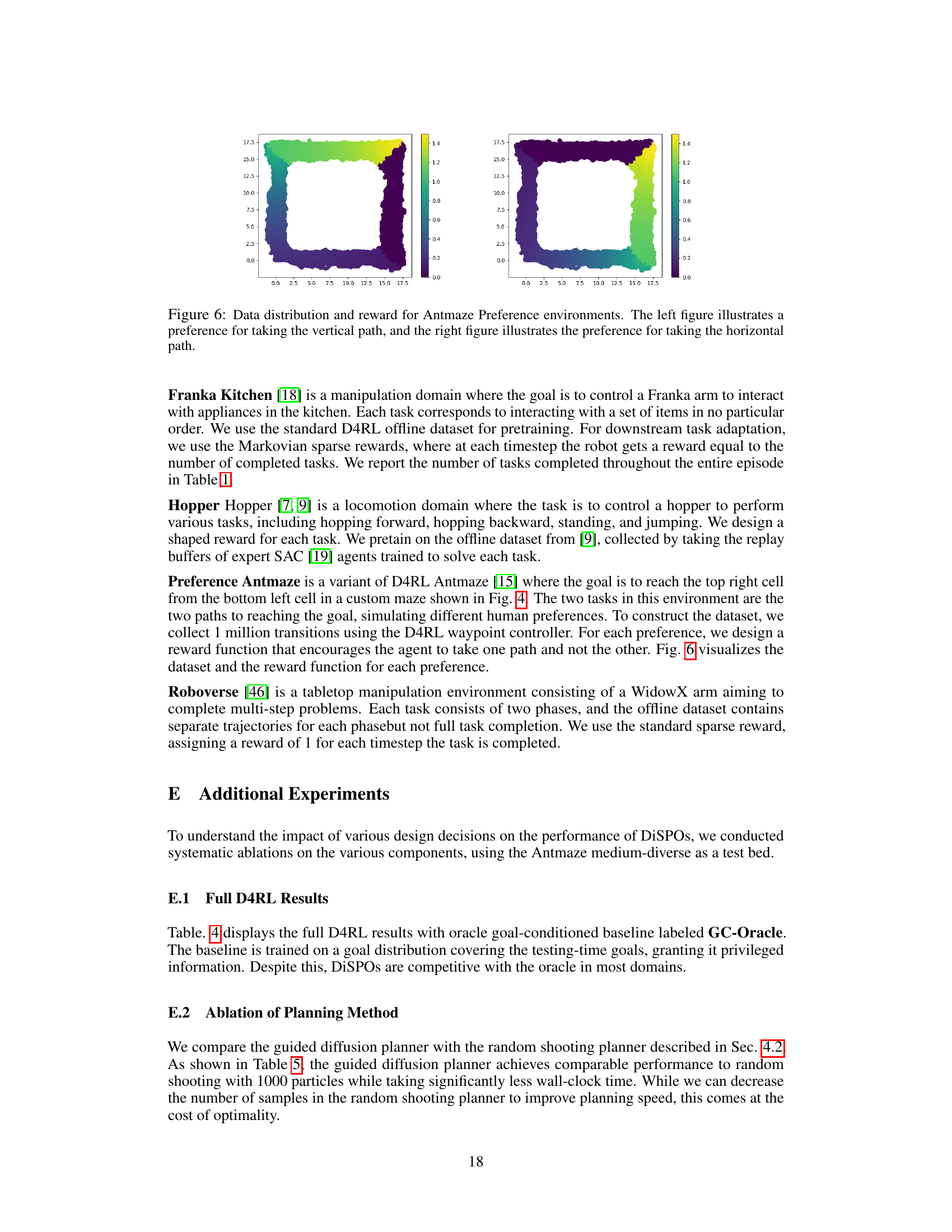

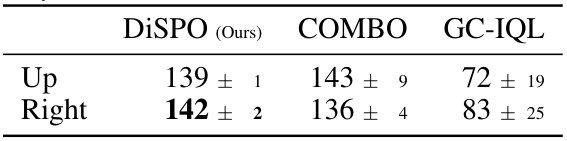

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating DiSPOs and baseline methods on non-goal-conditioned tasks. The results show that DiSPOs can solve these tasks, demonstrating an ability to optimize for arbitrary reward functions, unlike goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (RL) methods which are limited to optimizing for specific goals. The preference Antmaze environment, shown in Figure 4, is used to highlight DiSPOs’ ability to take different paths to achieve a goal. This contrasts with goal-conditioned RL which may only take a single optimal path.

read the caption

Table 2: Evaluation on non-goal-conditioned tasks. DiSPOs are able to solve non-goal-conditioned tasks, taking different paths in preference antmaze (Fig 4), while goal-conditioned RL cannot optimize for arbitrary rewards.

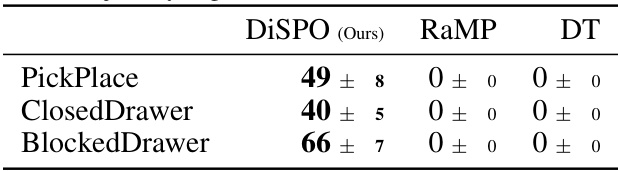

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating the trajectory stitching capabilities of DiSPOs, a novel method for zero-shot policy optimization. The results demonstrate that DiSPOs significantly outperforms other baseline methods (RaMP and Decision Transformer) in three complex robotic manipulation tasks (PickPlace, ClosedDrawer, and BlockedDrawer). This highlights DiSPOs’ ability to effectively combine suboptimal trajectories to achieve optimal behavior.

read the caption

Table 3: Evaluation of trajectory stitching ability of DiSPOs. DiSPOs outperform non-stitching baselines, demonstrating their abilities to recombine outcomes across trajectory segments

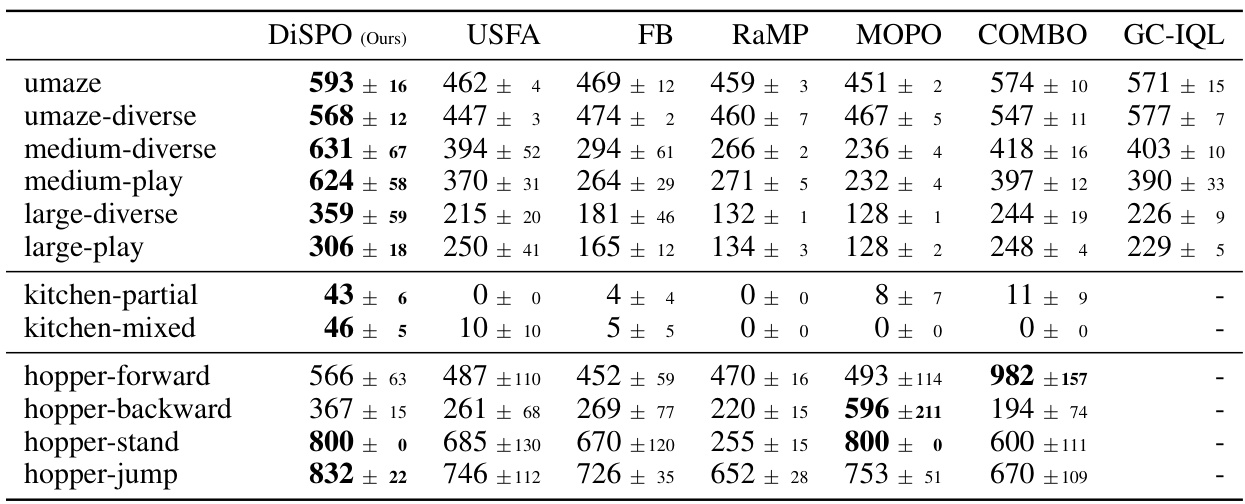

🔼 This table presents a comparison of DiSPOs against several baseline methods on two multi-task reinforcement learning problems, AntMaze and Kitchen. The results demonstrate DiSPOs’ superior performance in terms of average episodic return across various task settings compared to approaches based on successor features, model-based reinforcement learning, and goal-conditioned baselines. The superior performance highlights DiSPOs’ ability to transfer effectively to new tasks without requiring extensive retraining.

read the caption

Table 1: Offline multitask RL on AntMaze and Kitchen. DiSPOs show superior transfer performance (in average episodic return) than successor features, model-based RL, and misspecified goal-conditioned baselines.

🔼 This table presents the results of offline multitask reinforcement learning experiments on AntMaze and Kitchen environments. It compares the performance of DiSPOs (Distributional Successor Features for Zero-Shot Policy Optimization) against several baselines, including other successor feature methods (USFA, FB, RaMP), model-based RL methods (MOPO, COMBO), and a goal-conditioned method (GC-IQL). The key metric is the average episodic return, which demonstrates DiSPOs’ superior transfer learning capabilities across different tasks within each environment.

read the caption

Table 1: Offline multitask RL on AntMaze and Kitchen. DiSPOs show superior transfer performance (in average episodic return) than successor features, model-based RL, and misspecified goal-conditioned baselines.

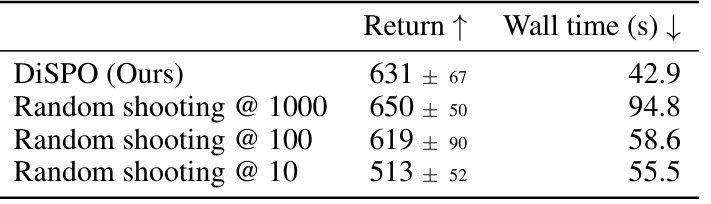

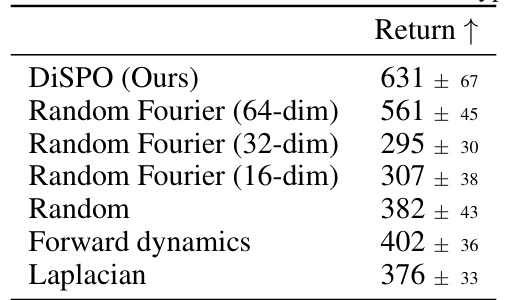

🔼 This table shows the ablation study on feature dimension and type. It compares various versions of the DiSPOs method that use different numbers of dimensions (64, 32, and 16) for random Fourier features, as well as using simpler random features and two top-performing pretrained features from another paper. The results demonstrate the impact of the feature representation on the overall performance of the method. Lower dimensional features have less expressivity resulting in poorer performance. Pretrained features show lower performance compared to randomly initialized Fourier features. This suggests that the random Fourier features strike a better balance between expressivity and the avoidance of overfitting to a specific objective.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation of feature dimension and type.

🔼 This table presents the results of offline multitask reinforcement learning experiments on the AntMaze and Kitchen environments. The table compares the performance of DiSPOs (Distributional Successor Features for Zero-Shot Policy Optimization) against several baseline methods, including various successor feature approaches (USFA, FB, RaMP), model-based RL methods (MOPO, COMBO), and a goal-conditioned method (GC-IQL). The performance metric is the average episodic return, indicating the cumulative reward obtained per episode. The results demonstrate that DiSPOs achieves significantly higher average episodic returns compared to the baseline methods across different variations of the AntMaze and Kitchen tasks, showcasing its superior transfer learning capabilities.

read the caption

Table 1: Offline multitask RL on AntMaze and Kitchen. DiSPOs show superior transfer performance (in average episodic return) than successor features, model-based RL, and misspecified goal-conditioned baselines.

🔼 This table presents the results of offline multitask reinforcement learning experiments on AntMaze and Kitchen environments. It compares the performance of DiSPOs (the proposed method) against several baselines, including successor features (USFA, FB, RaMP), model-based RL (MOPO, COMBO), and goal-conditioned RL (GC-IQL). The metric used is the average episodic return, showing DiSPOs’ superior transfer learning capability across different tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Offline multitask RL on AntMaze and Kitchen. DiSPOs show superior transfer performance (in average episodic return) than successor features, model-based RL, and misspecified goal-conditioned baselines.

Full paper#