TL;DR#

Channel simulation, crucial in areas like lossy compression, faces scalability challenges with existing methods. These struggle to handle many simultaneous channel uses, limiting performance. The methods used are usually either rate-optimal or computationally efficient, but not both. This paper explores the potential of coding theory to address this issue.

The researchers introduce PolarSim, leveraging the properties of polar codes to achieve both scalability and near-optimal rates. By cleverly mapping the original channel simulation problem into a set of simpler sub-problems, they harness the power of channel polarization. Their experimental results demonstrate significant improvements over state-of-the-art techniques, showcasing the effectiveness of their approach for various binary output channels. The method’s low computational complexity is a key advantage for large-scale applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel and efficient approach to channel simulation using techniques from coding theory. This addresses a critical limitation of existing methods, which struggle to scale with the number of channel uses. The proposed method, PolarSim, achieves near-optimal performance with only pseudo-linear complexity, opening up new avenues for research in areas such as lossy compression and generative modeling. The paper’s emphasis on scalability over perfect optimality at fixed dimensions offers a valuable lesson for other domains facing similar computational challenges.

Visual Insights#

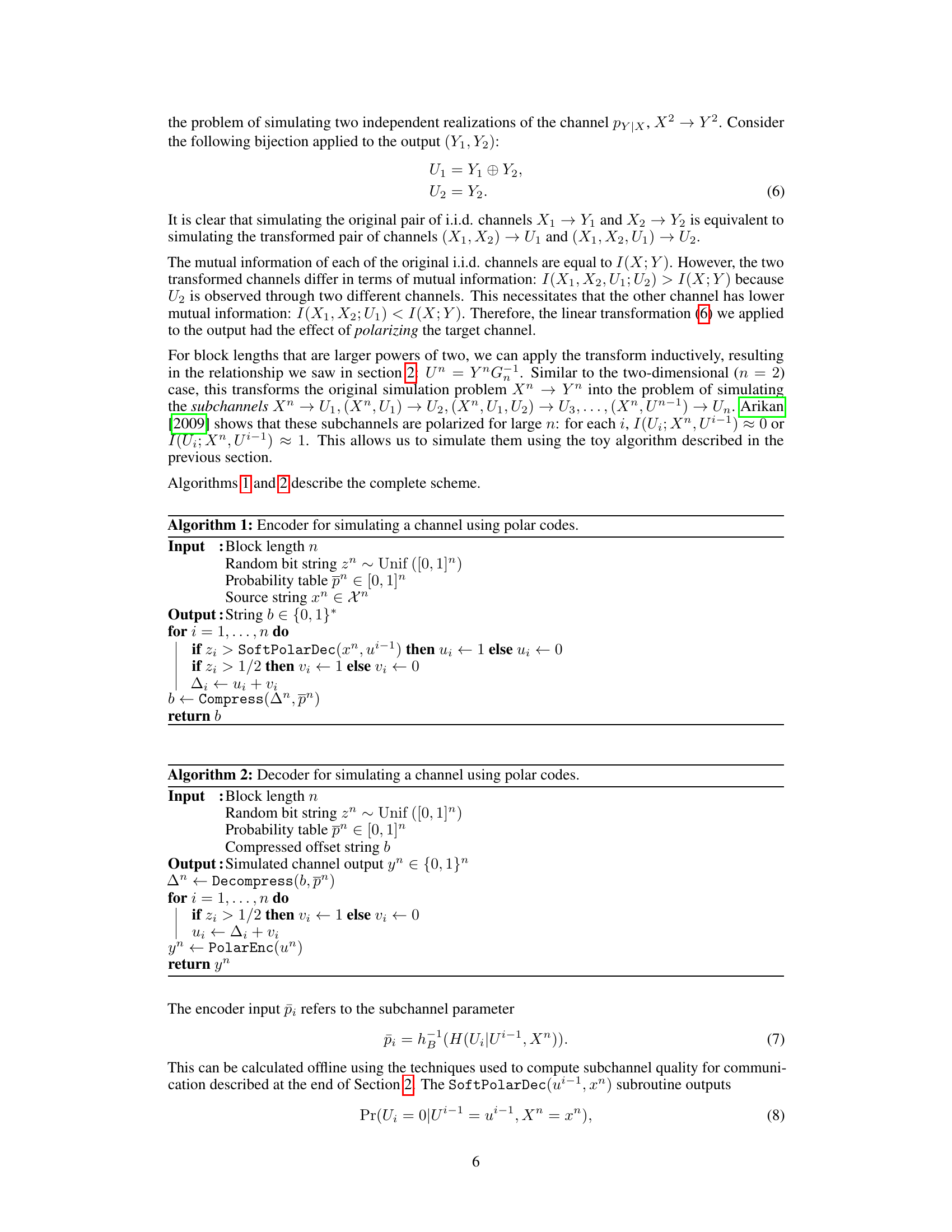

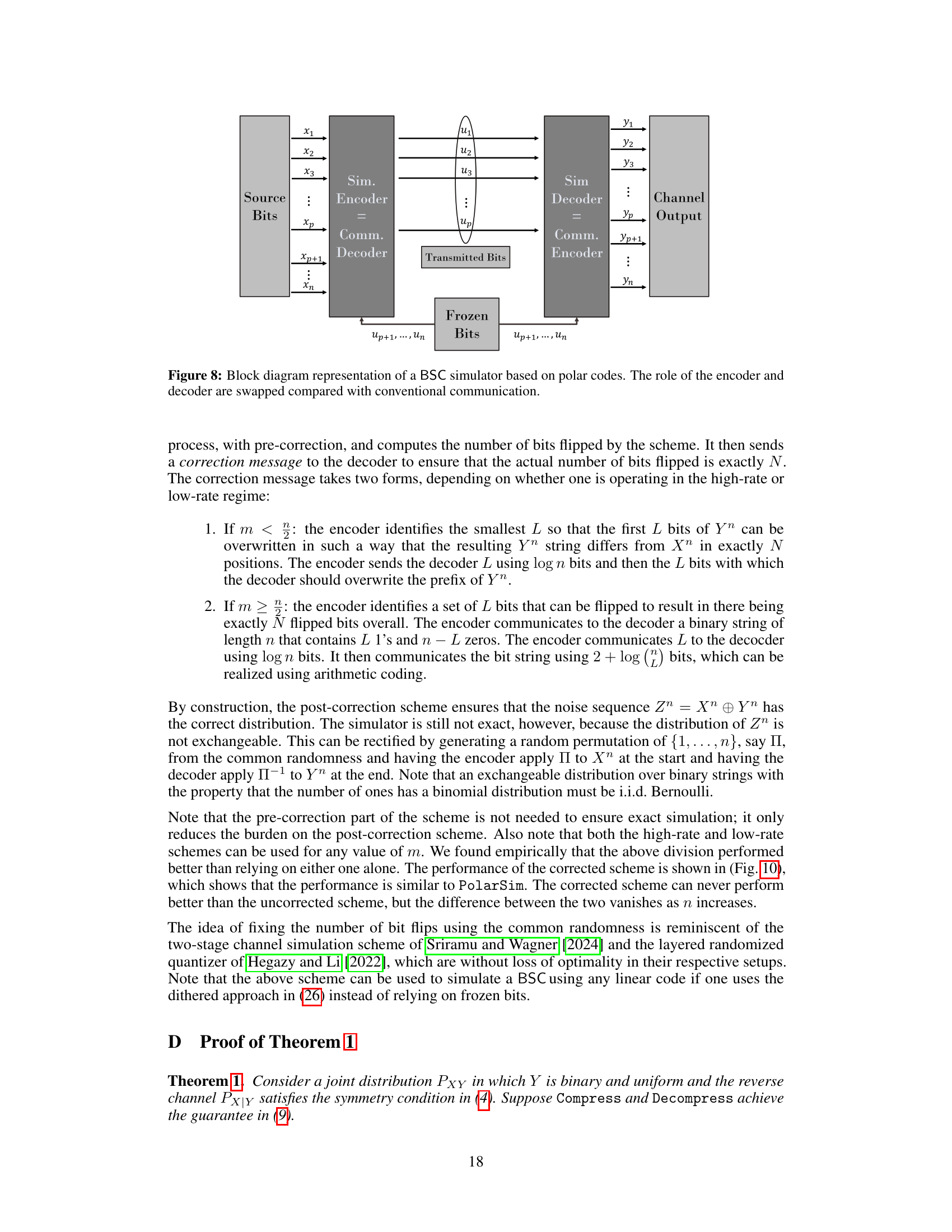

🔼 This figure shows the channel polarization phenomenon for a Binary Symmetric Channel (BSC) with crossover probability 0.2. It demonstrates how, as the block length (n) increases, the subchannels polarize, meaning their mutual information I(Ui; Xn, Ui−1) approaches either 0 or 1. The plots illustrate this polarization for n = 212 and n = 215, showing the convergence towards ideal polarization as n grows. The figure also includes theoretical upper bounds on the rate of the proposed PolarSim scheme, highlighting its near-optimal rate performance for large n.

read the caption

Figure 1: Channel polarization for a BSC with crossover probability 0.2 and block lengths n = 212 (top) and n = 215 (bottom). The scatter plots on the left show the subchannel capacities I(Ui; Xn, Ui−1) for each index i. In the curves (●) on the right, these indices are sorted in the increasing order of their subchannel capacities for better visualization. The area under these curves is the mutual information lower bounds at their respective block length. The vertical dotted line marks the ideal polarized channel, i.e., the fraction of indices to its right is equal to the mutual information of the channel. We see that the sorted subchannel capacity curve approaches this line as the block length is increased. Finally, we also plot the theoretical upper bound (see (38)) on the rate of our proposed scheme, PolarSim, for block lengths n = 212 and n = 215. The area under these curves is an upper bound on the rate of PolarSim. The shaded area in between is therefore an upper bound on the redundancy of PolarSim, which vanishes as n→∞ due to the polarization phenomenon.

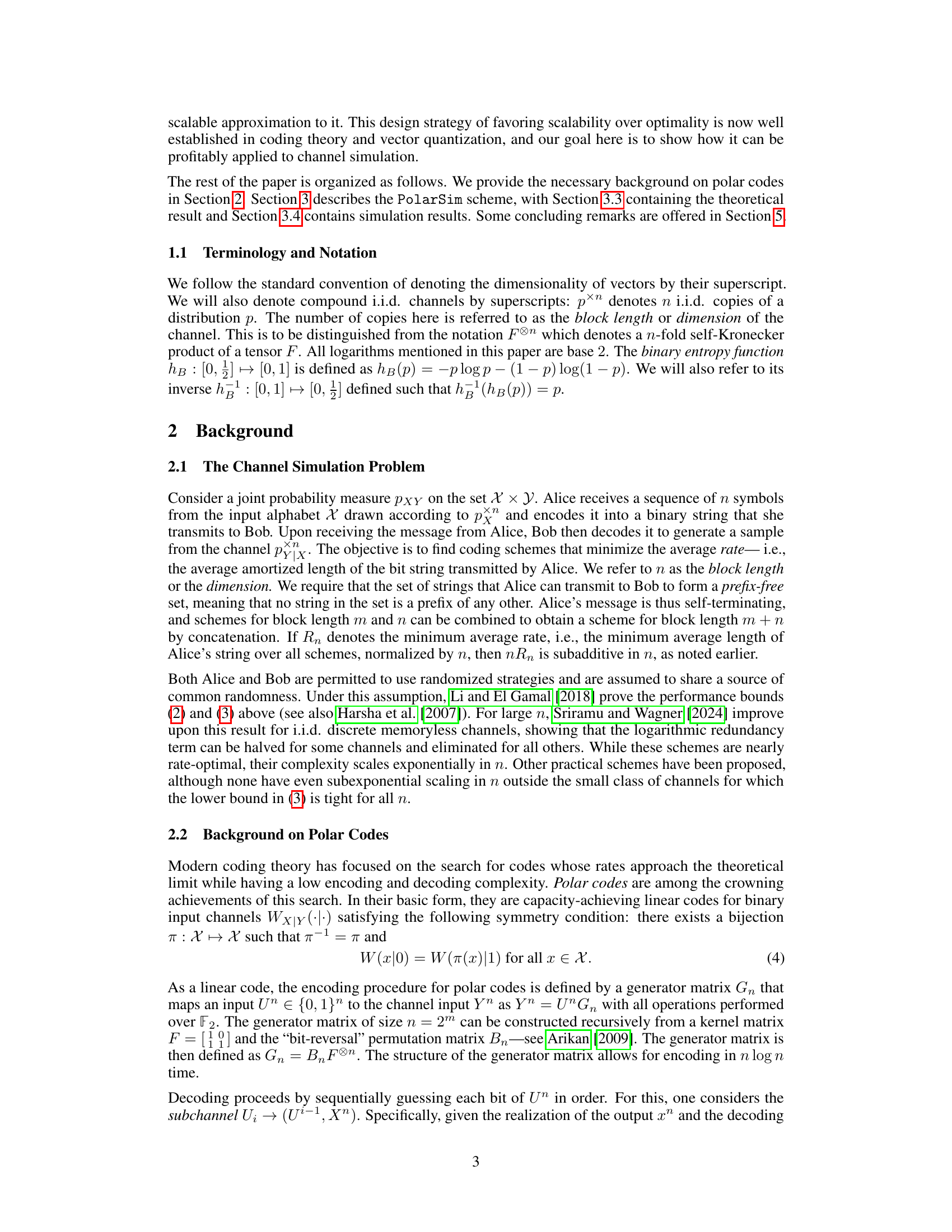

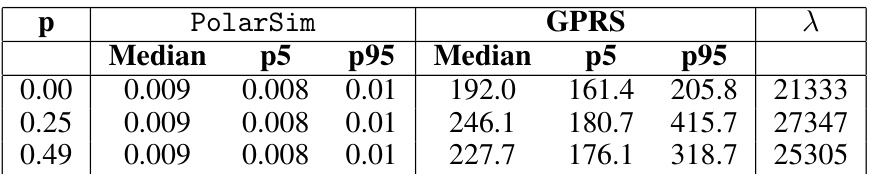

🔼 This table compares the execution time of PolarSim and GPRS for simulating binary symmetric channels (BSCs) with block length n=212. It highlights PolarSim’s significantly faster performance (over four orders of magnitude) compared to GPRS, especially at larger block lengths where GPRS struggles due to its exponential scaling in n. The table also shows that PolarSim’s runtime remains consistent across varying crossover probabilities (p).

read the caption

Table 1: Execution time comparison between PolarSim and GPRS, for simulating BSC's with block length n = 212. The reported statistics are computed over 1000 trials for each value of the crossover probability p. GPRS cannot directly simulate such large block lengths. Therefore, the GPRS runtimes are obtained by scaling up the runtime for n = 8 blocks. This is justified by subadditivity (see (1)). The column λ computes the ratio between the medians of the two schemes. For our chosen block length, PolarSim performs over four orders of magnitude faster than GPRS.

In-depth insights#

Polar Codes for Sim#

The heading ‘Polar Codes for Sim’ suggests a research direction applying polar codes to simulation tasks. This is a novel approach, potentially leveraging polar codes’ capacity-achieving properties and efficient encoding/decoding algorithms to improve simulation efficiency and scalability, especially for high-dimensional problems. The use of polar codes could lead to significant improvements in rate and complexity compared to traditional methods. Practical implementation would likely involve mapping the simulation problem onto a channel coding framework. A key challenge could be handling non-binary or non-symmetric simulation scenarios, requiring modifications or extensions to standard polar code techniques. Success would significantly advance simulation capabilities, particularly in areas needing high-throughput or limited resources. The ‘Sim’ aspect remains open to interpretation, possibly referring to systems simulation, channel simulation, or another area benefiting from efficient coding techniques.

Toy Scheme Analysis#

A ‘Toy Scheme Analysis’ section would critically evaluate a simplified approach to channel simulation, likely preceding a more sophisticated method. It would demonstrate the fundamental concepts before introducing complexities. The analysis would likely involve deriving rate expressions, calculating the mutual information, and comparing these metrics to theoretical limits. A key aspect would be identifying the scheme’s limitations, such as its suboptimality for high-dimensional scenarios or specific channel types. This section might also include numerical simulations to visualize rate performance, error behavior, and convergence properties. The goal is to build intuition, justifying the need for a more advanced approach and providing a baseline for comparison.

Scalable Simulation#

Scalable simulation is a crucial challenge in various fields, demanding efficient methods to handle increasing data volumes and complexities. The core idea revolves around designing algorithms and techniques capable of simulating systems with growing sizes and dimensions without a corresponding exponential increase in computational costs. This often involves clever use of mathematical structures like error-correcting codes, enabling the simulation to leverage amortization and parallelization to achieve scalability. The success of such an approach hinges on a careful balance between accuracy and efficiency, often requiring approximations or suboptimal solutions that still yield significant speedups in simulation times, especially for high-dimensional problems. Polar codes, for example, offer a compelling avenue for efficient simulation of specific channel types, with their pseudolinear time complexity promising substantial performance gains compared to conventional methods. However, limitations may exist, like restrictions to certain channel types (e.g., binary output) or the need for approximations that impact simulation accuracy. The overall success of scalable simulation lies in identifying computationally efficient structures to maintain a reasonable trade-off between scalability and the desired accuracy of the simulation.

Rate Optimality#

Rate optimality in channel simulation focuses on minimizing the number of bits needed to represent the simulated channel output while maintaining fidelity to the true channel’s statistical properties. Achieving rate optimality is crucial for efficient simulation, especially when dealing with high-dimensional or complex channels. The paper investigates how coding theory techniques, particularly using polar codes, can be used to improve the rate efficiency. The theoretical analysis provides guarantees that, under specific conditions (like symmetric binary-output channels), the proposed scheme (PolarSim) asymptotically achieves the optimal rate, meaning the simulation requires a minimum number of bits per channel use. However, practical limitations exist, as the optimality holds in the large-n limit and may not be realized for smaller block sizes. Furthermore, the symmetric binary-output channel constraint limits applicability. The comparison with existing methods highlights the significant rate improvement offered by this coding theory approach, showcasing its potential in scenarios where efficient channel simulation is vital. The authors’ focus on scalability further emphasizes the practical significance of their work.

Future Extensions#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore extending PolarSim to non-binary channels and investigating the use of other advanced coding techniques beyond polar codes, such as turbo codes or LDPC codes. A key area for further investigation is developing efficient methods for simulating continuous channels, such as the Gaussian channel, which are prevalent in various applications. Exploring the interplay between channel simulation and practical compression applications like learned image compression would yield valuable insights. Finally, a rigorous investigation into achieving the optimal trade-off between computational efficiency and rate optimality, especially for higher-dimensional channels, remains an important area for future study. Addressing the challenge of simulating complex, non-i.i.d. channels represents a significant frontier in this field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

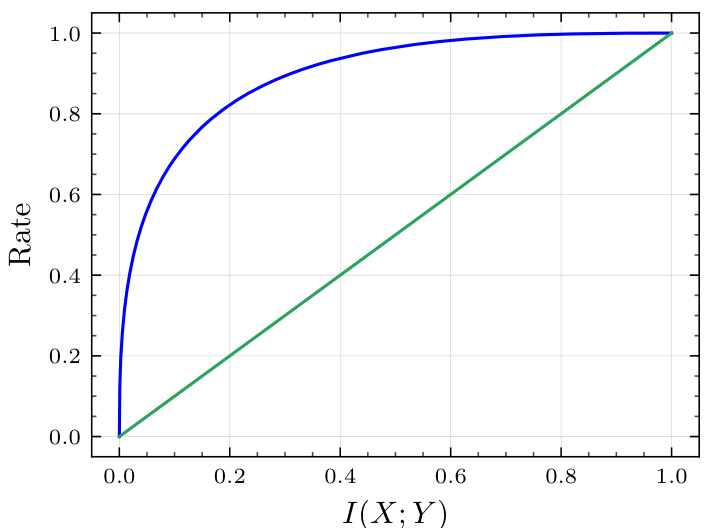

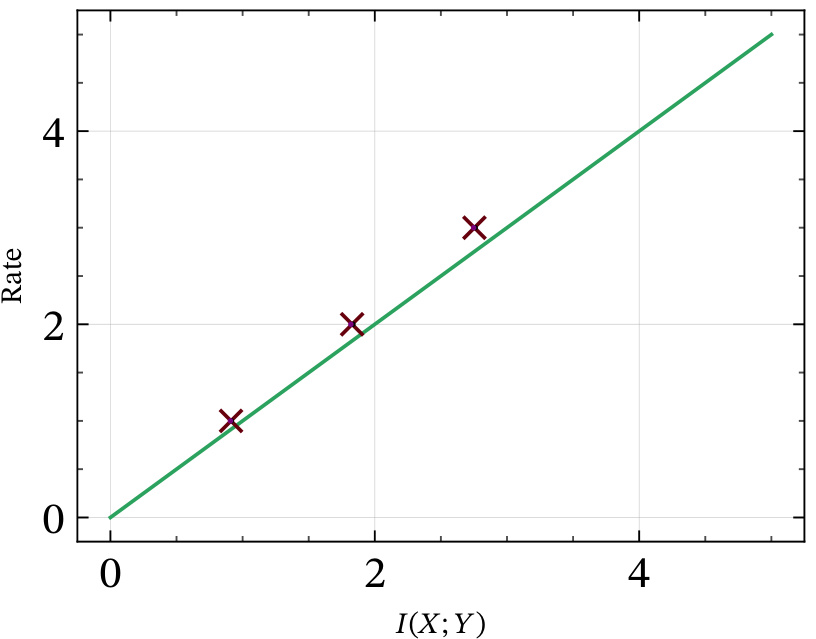

🔼 This figure compares the upper bound on the rate of the toy scheme (described in Section 3.1 of the paper) against the mutual information lower bound. The x-axis represents the mutual information I(X;Y), and the y-axis represents the rate. The blue curve represents the upper bound, showing that the rate increases as mutual information increases but not linearly. The green line represents the lower bound, showing a linear relationship between rate and mutual information.

read the caption

Figure 2: The upper bound on the rate of the toy scheme described in section 3.1 is plotted against the mutual information lower bound ().

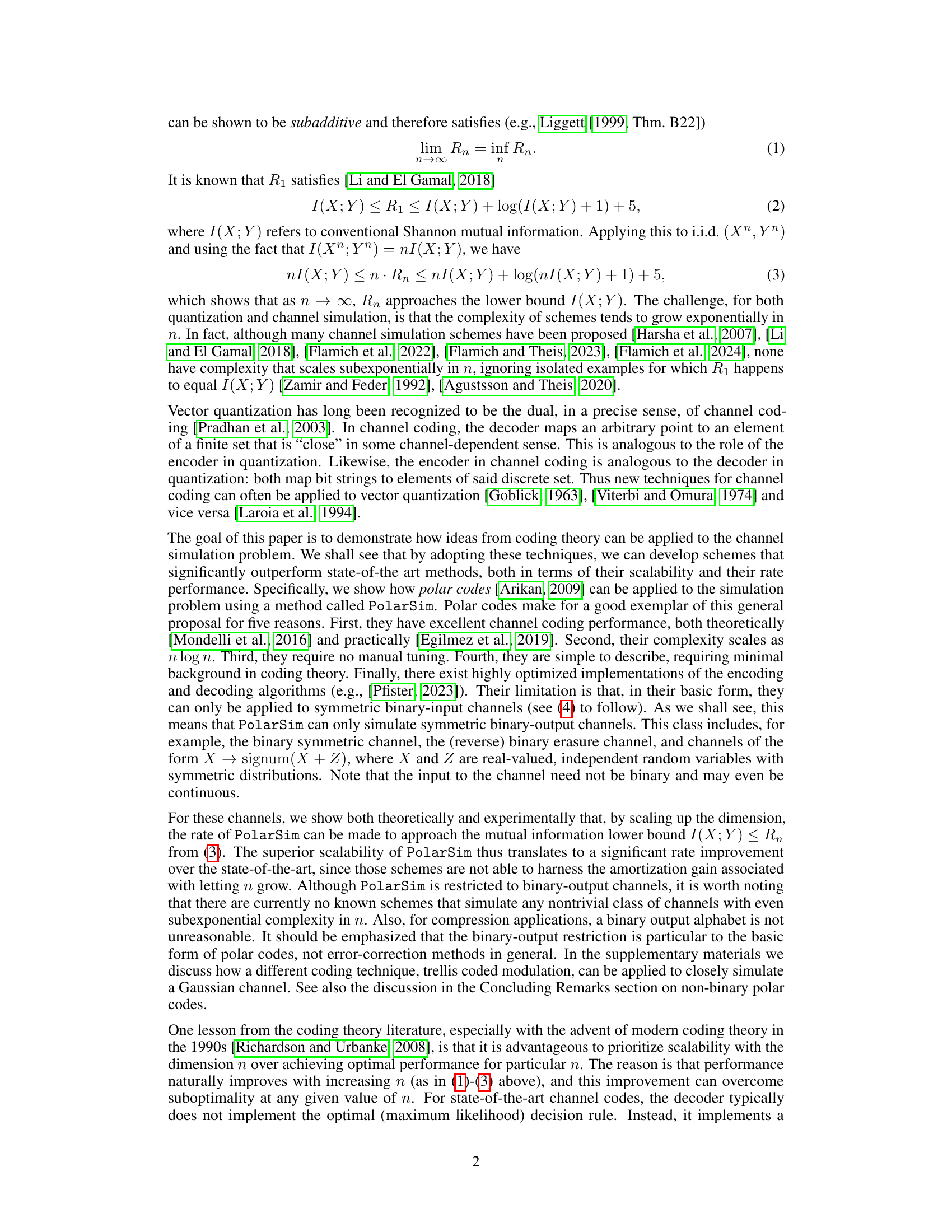

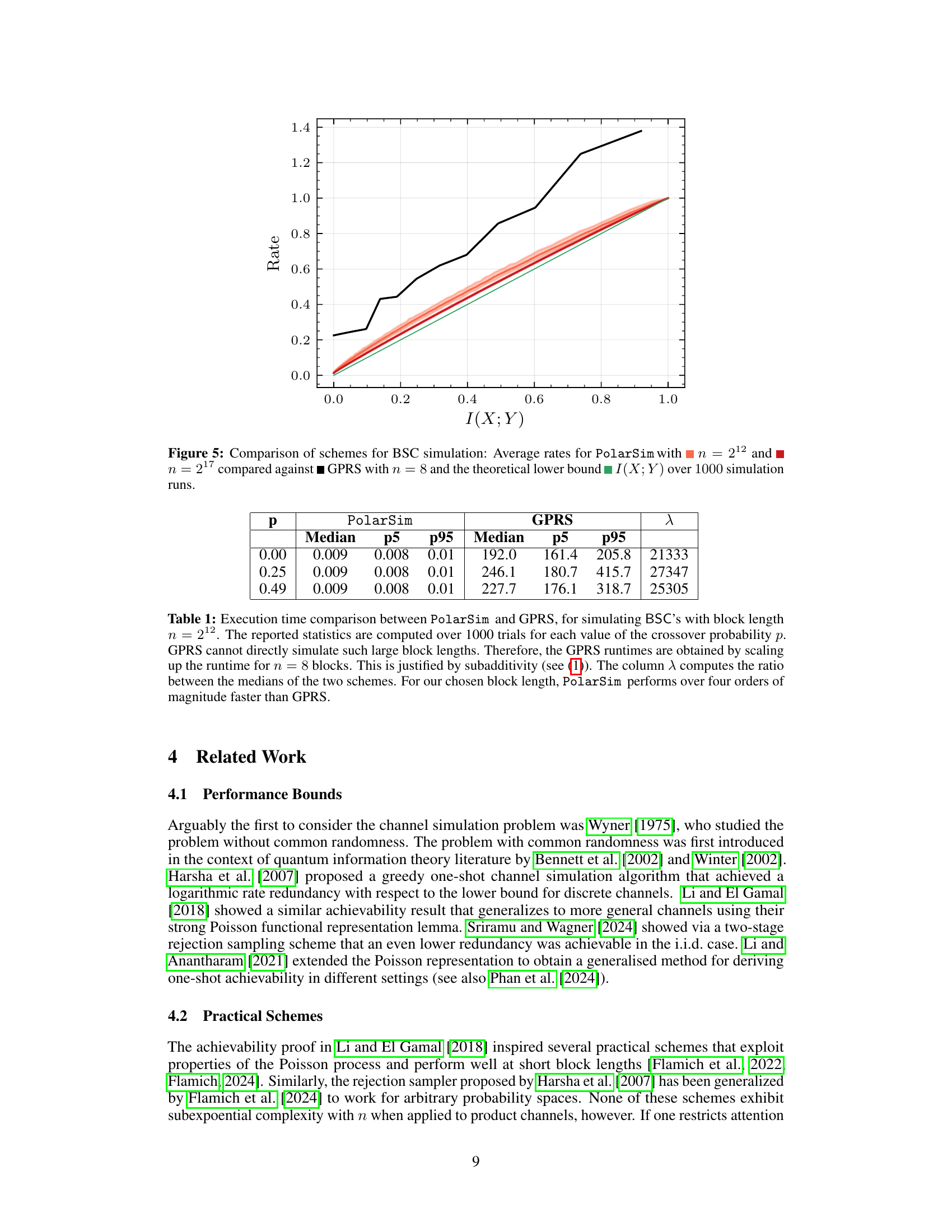

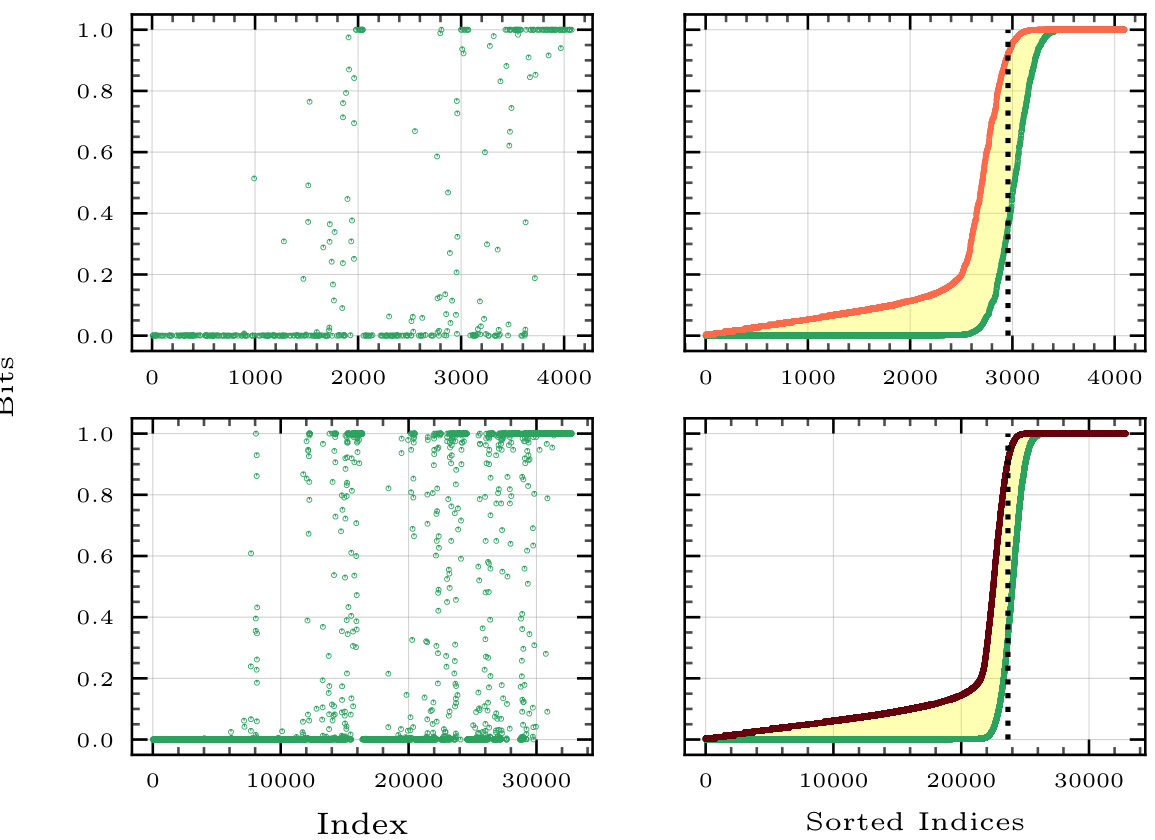

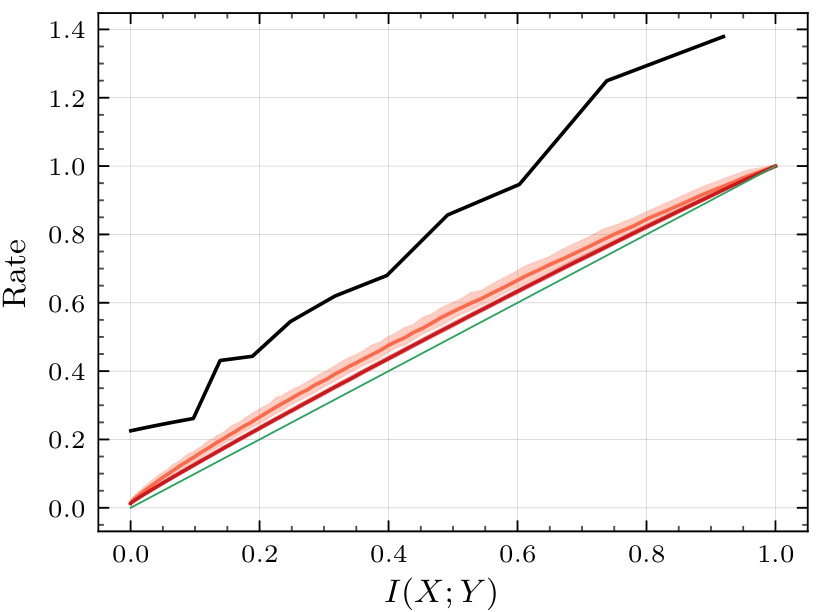

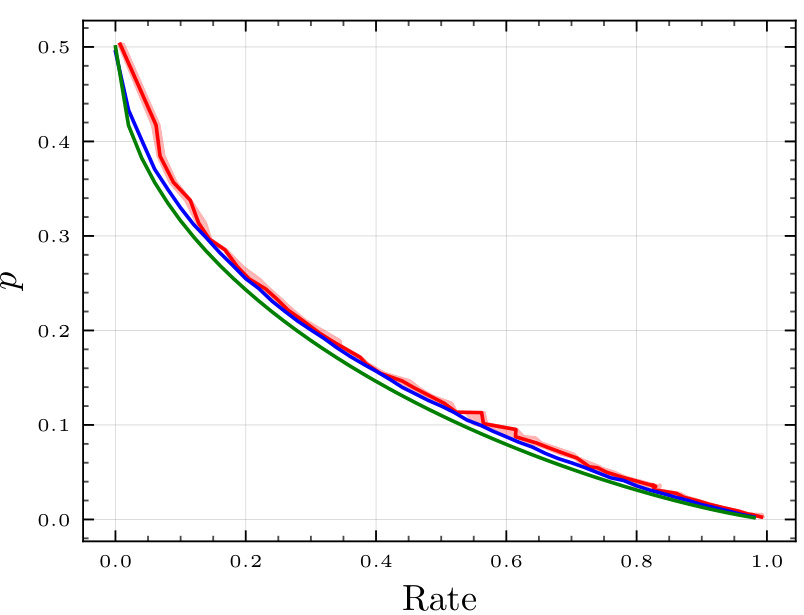

🔼 This figure compares the rates achieved by the PolarSim algorithm against the theoretical lower bound for different block lengths (n = 212, 214, 217) and noise levels across three types of channels: Binary Symmetric Channel (BSC), Gaussian, and Erasure. The plots show median rates and 5th to 95th percentile ranges from 200 simulation runs, highlighting the algorithm’s performance and the impact of increasing block length.

read the caption

Figure 3: Rates achieved by PolarSim at different block lengths — n = 212 (left), n = 217 (top-right and middle-right), n = 214 (bottom-right) for different noise levels across different channels, compared against the theoretical lower bound I(X; Y) . Top: BSCp for p ∈ (0,5), Middle: Gaussian for σ∈ (0,3), Bottom: Erasure for € ∈ (0, 1). The lines represent the median values, and the boundaries of shaded regions represent the 5th to 95th percentile rates over 200 simulation runs.

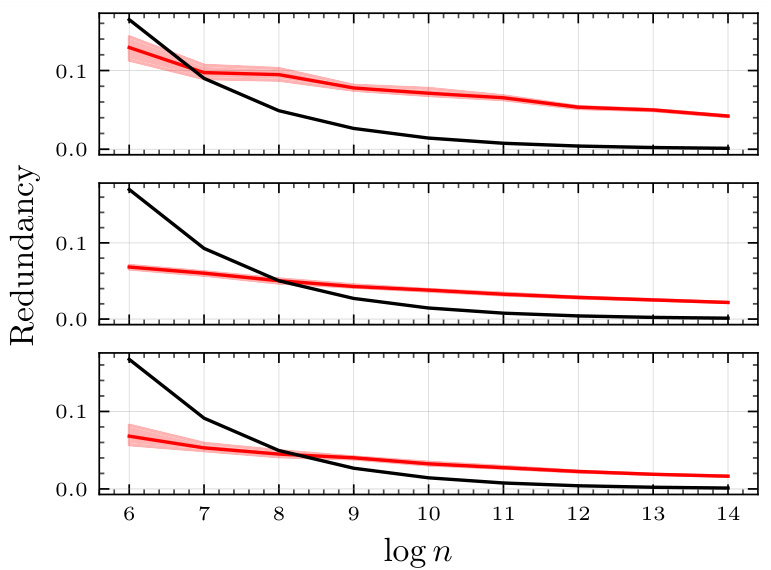

🔼 This figure shows the redundancy of the PolarSim scheme for three different channels (BSC, Reverse Binary Gaussian, and Reverse Binary Erasure) as a function of block length. The median redundancy and 95% confidence intervals are shown. The plot compares PolarSim’s performance to the theoretical maximum redundancy of PFRL, highlighting that PolarSim’s redundancy decreases as block length increases, consistent with known channel coding results.

read the caption

Figure 4: The redundancy of PolarSim is plotted for certain fixed channels (Top: BSC with p = 0.05, Middle: Reverse binary Gaussian channel with σ = 0.5, Bottom: Reverse binary erasure channel with ε = 0.2) as the block length n is varied. The plotted curve (■) is the median redundancy over 200 simulations, with the boundaries of the shaded region showing the bootstrapped 95% confidence interval around the sample median. The redundancy is defined as the gap between the achieved rate and the mutual information lower bound. For comparison, the theoretical maximum redundancy of PFRL (■) is also plotted for the respective channels (see (3)). We see that for large block lengths, PolarSim has a higher redundancy, which is consistent with known results from channel coding [Mondelli et al., 2016].

🔼 This figure compares the upper bound on the rate of the toy scheme (described in section 3.1 of the paper) against the mutual information lower bound. It visually demonstrates the suboptimality of the toy scheme, especially when the mutual information is not close to 0 or 1. This motivates the need for a more efficient approach like PolarSim, which is introduced later in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 2: The upper bound on the rate of the toy scheme described in section 3.1 is plotted against the mutual information lower bound ()

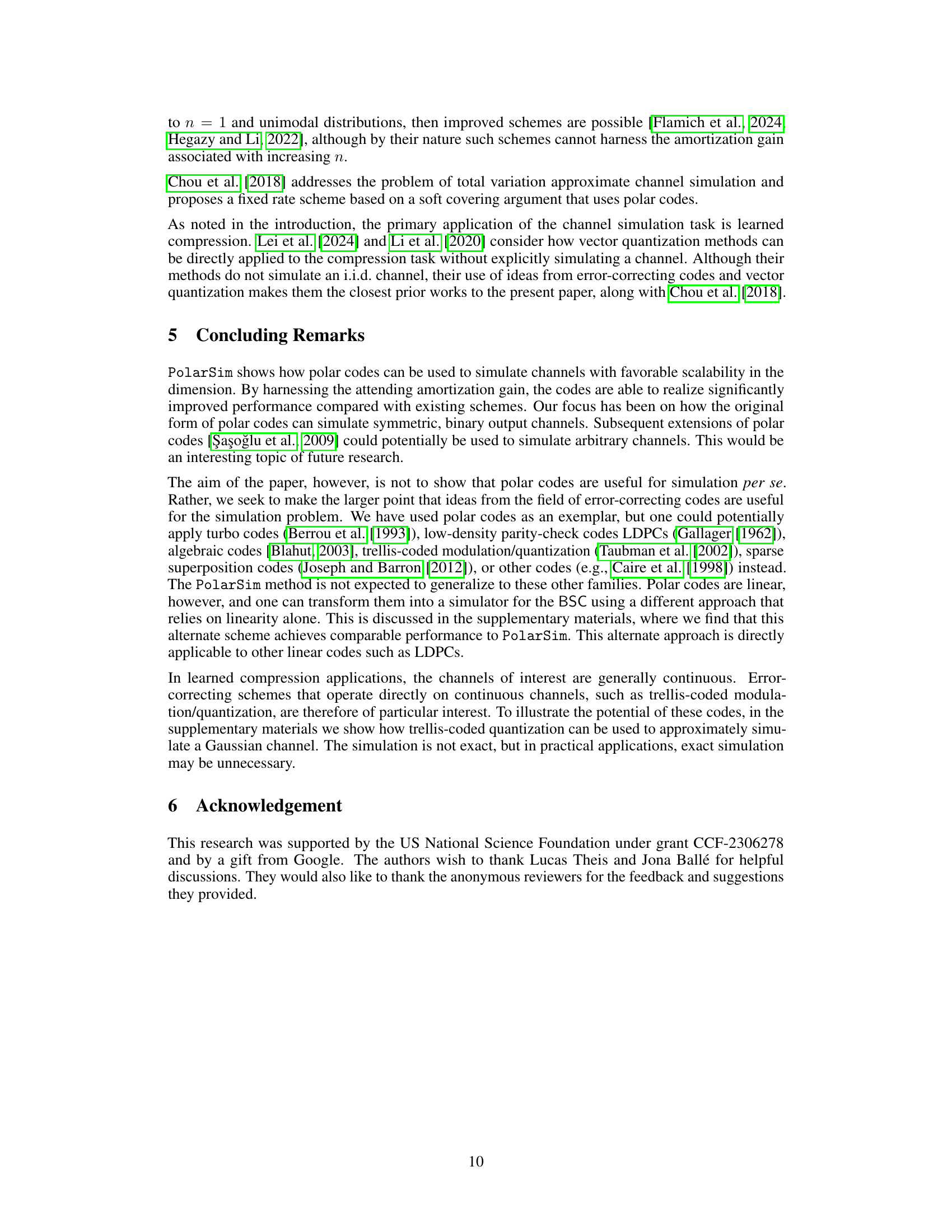

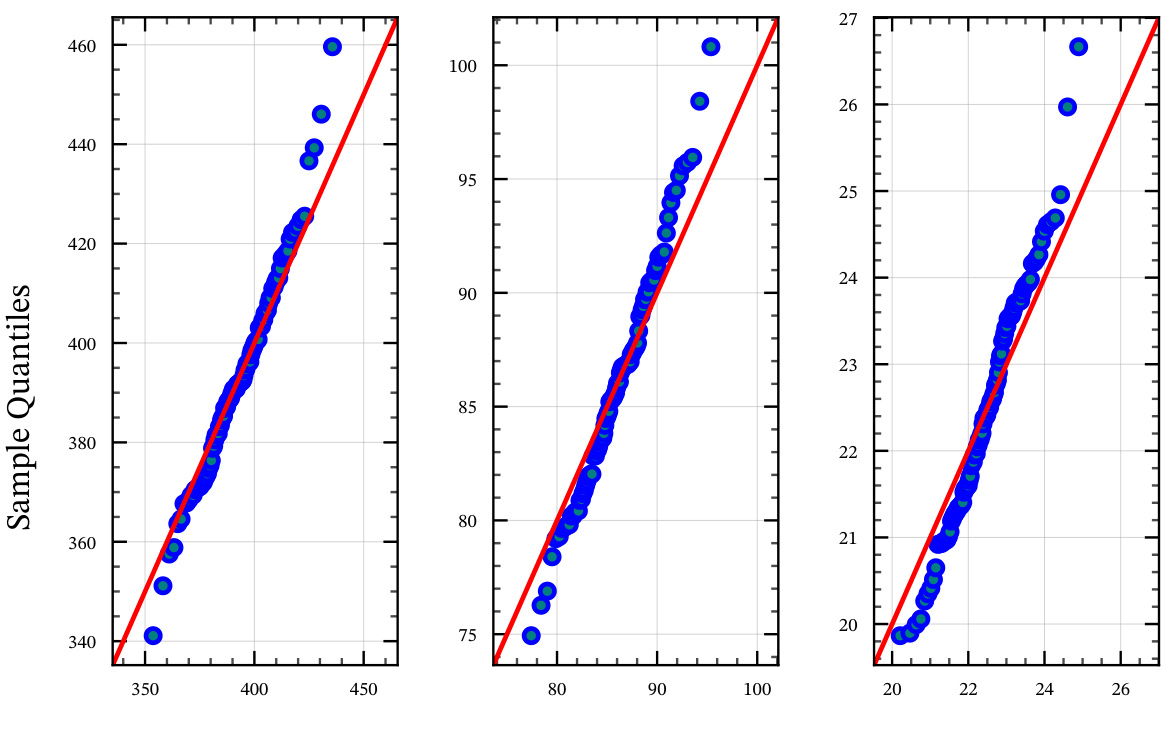

🔼 This figure displays quantile-quantile plots to compare the distribution of the sample noise from a trellis-coded quantizer against a theoretical AWGN (Additive White Gaussian Noise) distribution. Three plots are shown, each corresponding to a different rate (R=1, R=2, R=3) of the trellis-coded quantizer. The closeness of the points to the diagonal line indicates how well the sample noise matches the theoretical AWGN distribution.

read the caption

Figure 6: For trellis coded quantizers with rates R = 1 (Left), R = 2 (Middle) and R = 3 (Right), the quantiles for M = 100 realizations of the sample noise D = ||Yn – X™ ||² are plotted against the theoretical quantiles obtained from an AWGN with noise power E[D]. We use the sample mean to estimate E[D].

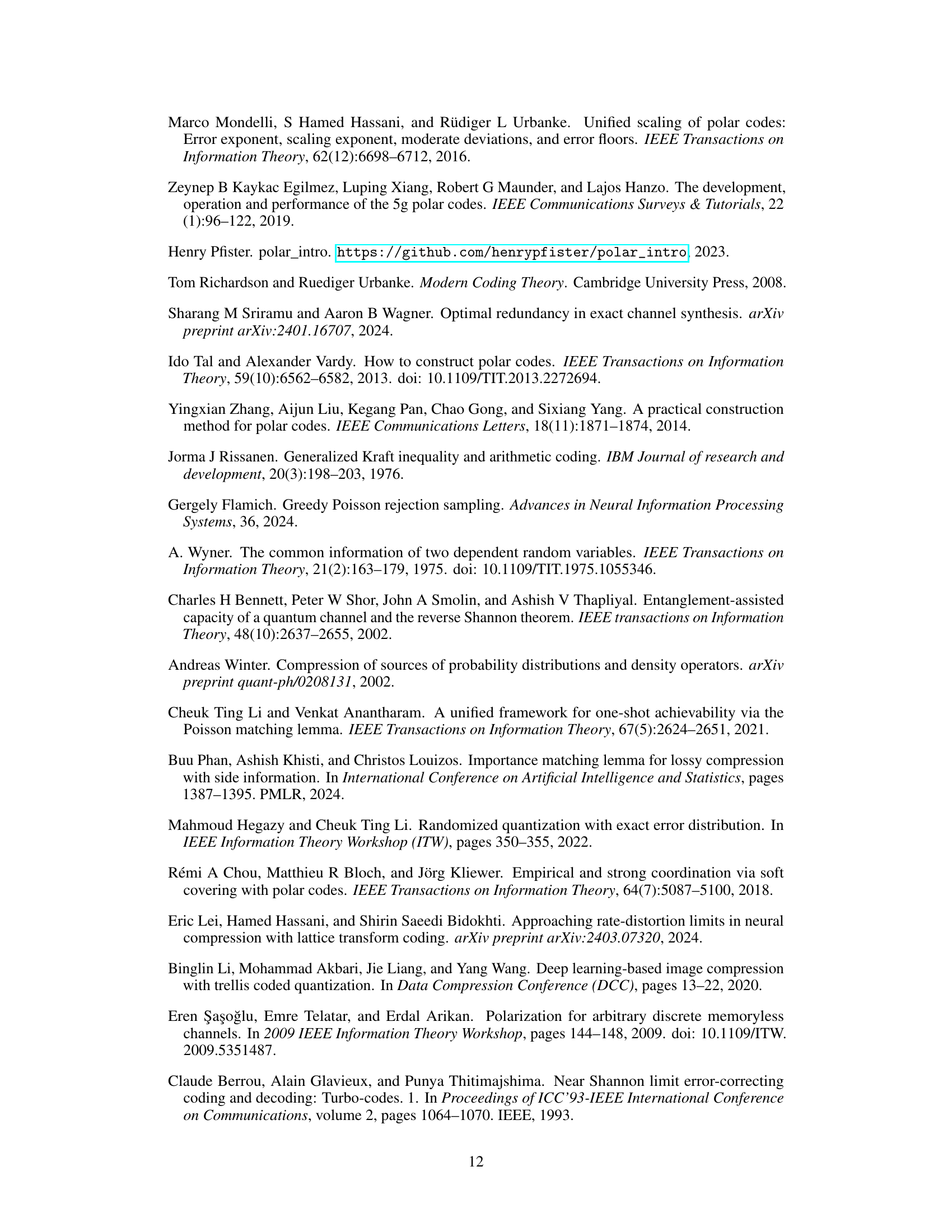

🔼 This figure shows the rate of the trellis-coded quantizer used in the approximate AWGN channel simulation scheme plotted against the mutual information of the simulated channel. The error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals of the mutual information, accounting for the estimation error in the noise power.

read the caption

Figure 7: The rate of the trellis quantizer is plotted against the mutual information of the simulated channel. Bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals are plotted for the noise mean estimate.

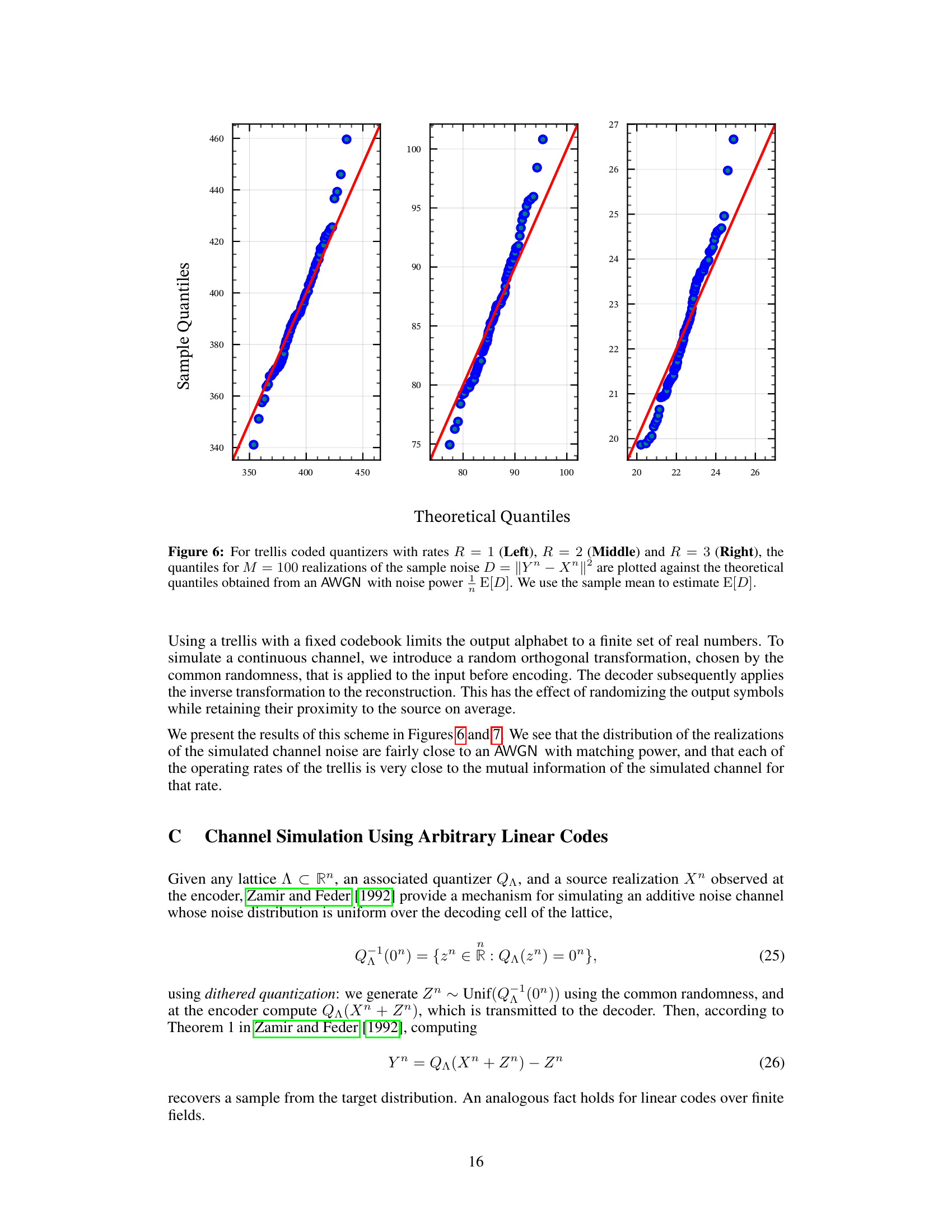

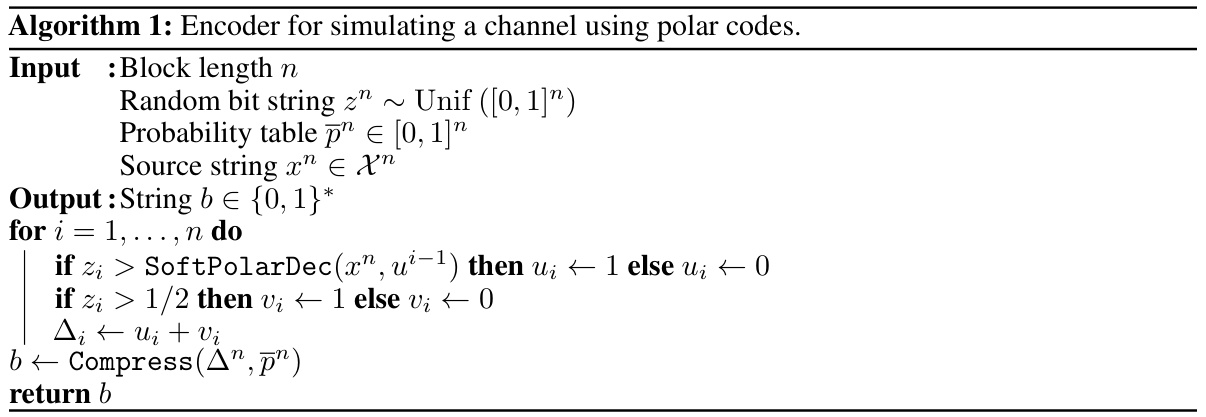

🔼 This figure shows a block diagram of a Binary Symmetric Channel (BSC) simulator using polar codes. The roles of the encoder and decoder are reversed compared to a standard communication system. The source bits are processed by a simulation encoder that uses common randomness (shared with the decoder) and frozen bits to generate transmitted bits. These bits are then compressed and sent to the decoder. The decoder uses common randomness, the received bits, and frozen bits to generate a simulated channel output. This illustrates the duality between channel coding and channel simulation that is exploited by the proposed PolarSim algorithm.

read the caption

Figure 8: Block diagram representation of a BSC simulator based on polar codes. The role of the encoder and decoder are swapped compared with conventional communication.

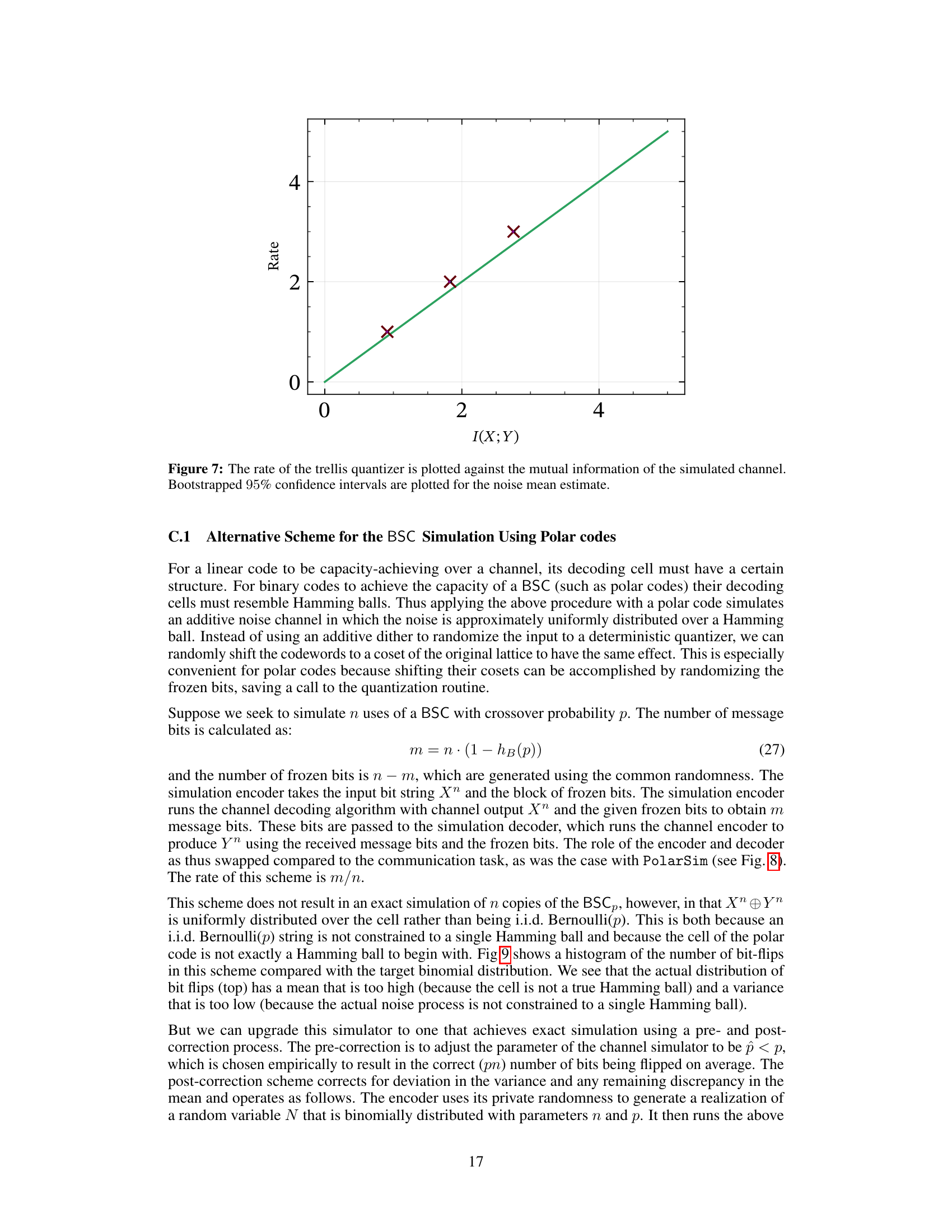

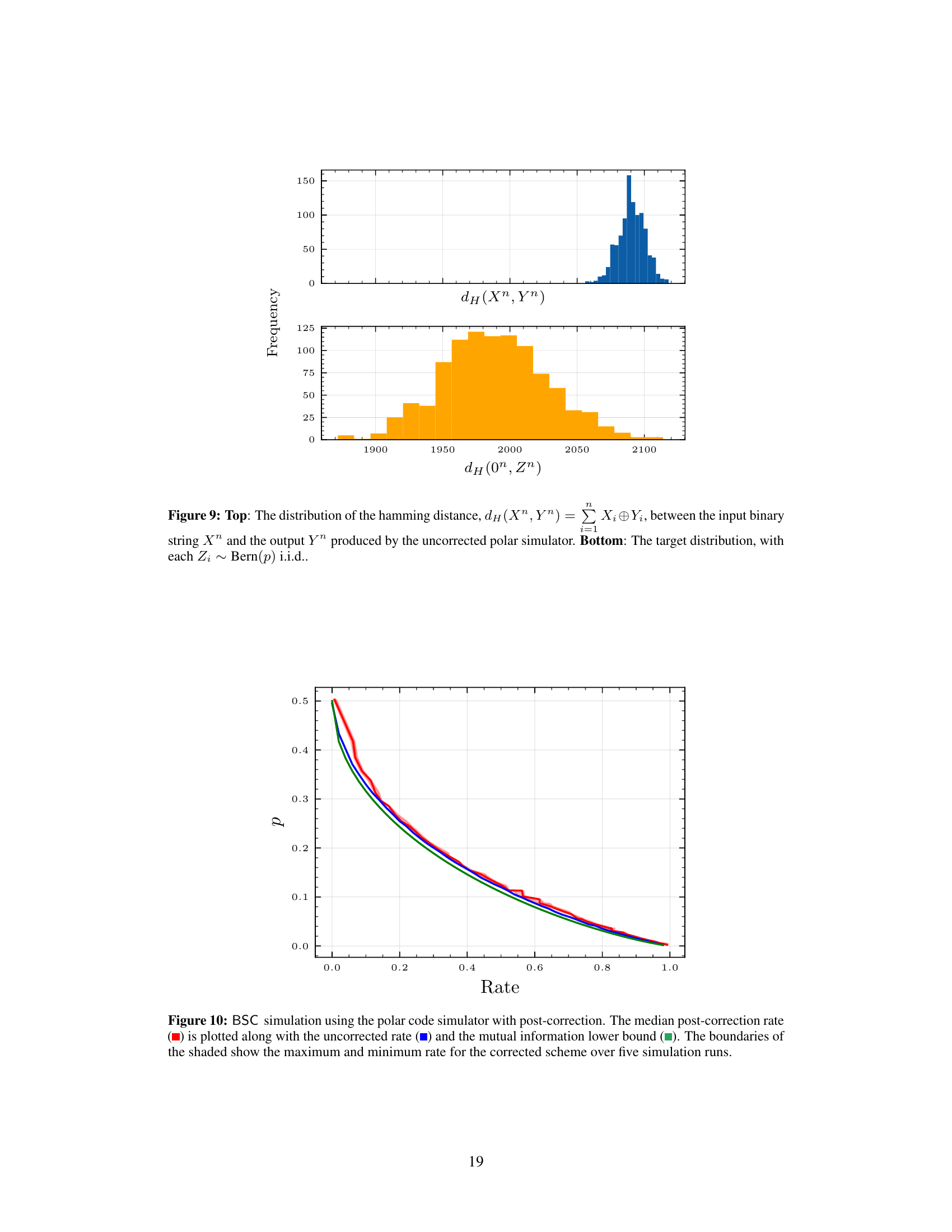

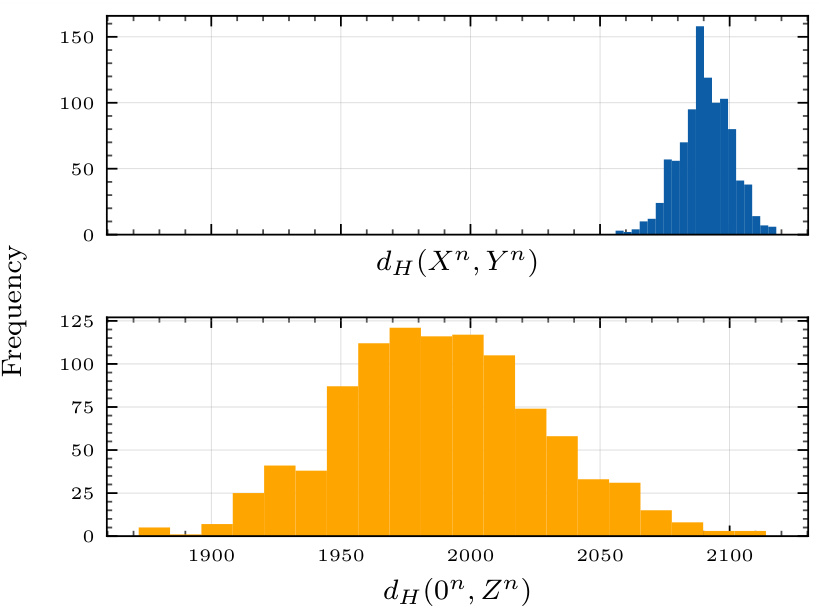

🔼 This figure compares the distribution of Hamming distances between input and output sequences generated by the uncorrected polar code simulator (top) against the target binomial distribution (bottom). The uncorrected simulator produces a distribution with a higher mean and lower variance compared to the desired binomial distribution.

read the caption

Figure 9: Top: The distribution of the hamming distance, dH(Xn, Yn) = Σni=1 Xi⊕Yi, between the input binary string Xn and the output Yn produced by the uncorrected polar simulator. Bottom: The target distribution, with each Zi ~ Bern(p) i.i.d.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison between the upper bound on the rate of a toy scheme for binary output channel simulation and the mutual information lower bound. The toy scheme is not rate-efficient in itself, but it serves as a basis for the PolarSim method which improves upon the toy scheme. The plot demonstrates the suboptimality of the toy scheme, particularly at lower mutual information values, highlighting the need for a more efficient method like PolarSim. The x-axis represents the mutual information I(X;Y), and the y-axis represents the rate.

read the caption

Figure 2: The upper bound on the rate of the toy scheme described in section 3.1 is plotted against the mutual information lower bound ().

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the execution times of PolarSim and GPRS for simulating Binary Symmetric Channels (BSCs) with a block length of 2¹². It highlights PolarSim’s significantly faster performance (orders of magnitude) compared to GPRS, particularly at larger block lengths where GPRS becomes computationally infeasible.

read the caption

Table 1: Execution time comparison between PolarSim and GPRS, for simulating BSC's with block length n = 2¹². The reported statistics are computed over 1000 trials for each value of the crossover probability p. GPRS cannot directly simulate such large block lengths. Therefore, the GPRS runtimes are obtained by scaling up the runtime for n = 8 blocks. This is justified by subadditivity (see (1)). The column λ computes the ratio between the medians of the two schemes. For our chosen block length, PolarSim performs over four orders of magnitude faster than GPRS.

🔼 This table compares the execution times of PolarSim and GPRS for simulating Binary Symmetric Channels (BSCs) with a block length of 4096. PolarSim significantly outperforms GPRS in terms of computational speed (by a factor of over 10,000). GPRS’s runtimes are extrapolated from smaller block length simulations (n=8) due to its inability to directly handle larger block sizes. The λ column shows the ratio of median runtimes, highlighting PolarSim’s superior efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Execution time comparison between PolarSim and GPRS, for simulating BSC's with block length n = 212. The reported statistics are computed over 1000 trials for each value of the crossover probability p. GPRS cannot directly simulate such large block lengths. Therefore, the GPRS runtimes are obtained by scaling up the runtime for n = 8 blocks. This is justified by subadditivity (see (1)). The column λ computes the ratio between the medians of the two schemes. For our chosen block length, PolarSim performs over four orders of magnitude faster than GPRS.

Full paper#