TL;DR#

Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) are powerful tools for solving partial differential equations (PDEs), but they often struggle with high-order or high-dimensional PDEs due to convergence issues. This difficulty arises because PINNs incorporate the PDE directly into the loss function, requiring the computation of derivatives up to the order of the PDE. This becomes increasingly complex and computationally expensive as the order and dimensionality increase. Existing solutions offer limited theoretical understanding of these pathological behaviors.

This paper addresses these limitations by providing a comprehensive theoretical analysis of the convergence behavior of PINNs, focusing on the inverse relationship between PDE order and convergence probability. The researchers demonstrate that higher-order PDEs hinder convergence due to the increased difficulty in optimization. To overcome this, they propose a novel method called variable splitting, which decomposes a high-order PDE into a system of lower-order PDEs. This effectively reduces the complexity of derivative calculation, resulting in improved convergence. Through rigorous mathematical proofs and numerical experiments, the study validates the efficacy of variable splitting and enhances our understanding of PINN behavior.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the critical issue of convergence difficulties in physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), especially when handling high-order or high-dimensional partial differential equations (PDEs). By offering theoretical insights and a practical solution (variable splitting), it directly impacts the applicability and reliability of PINNs in various scientific and engineering fields. This work also opens avenues for developing improved training strategies and more efficient network architectures for PINNs.

Visual Insights#

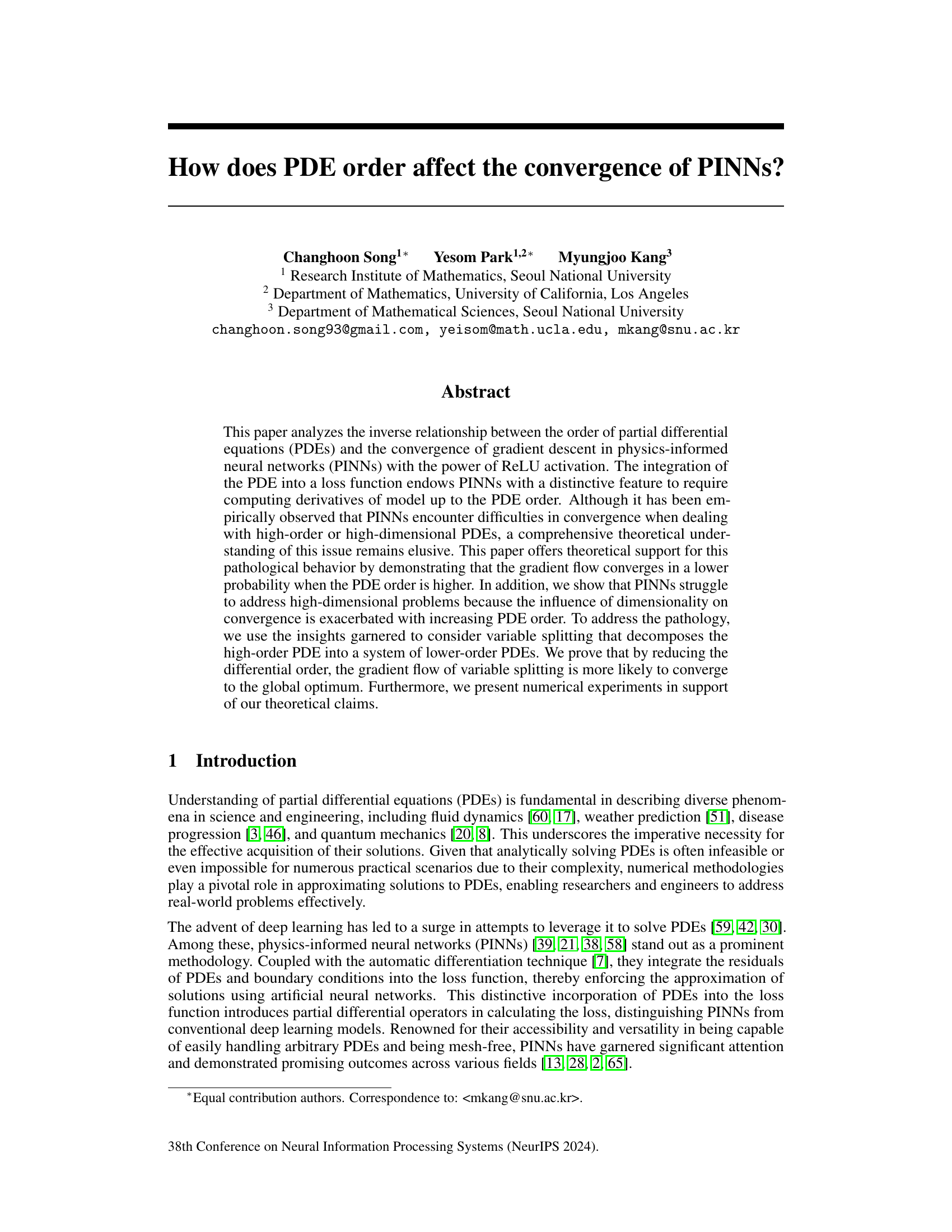

🔼 This figure shows the training losses for PINNs solving the bi-harmonic and Poisson equations. The plots illustrate how the training loss changes over epochs for different network widths (m) and different powers (p) of the ReLU activation function. It visually demonstrates the relationship between the PDE order, network width, activation power, and convergence. Each subplot represents a different value of p (the power of ReLU), and within each subplot are multiple lines showing the training loss for various network widths m. The results support the authors’ theoretical findings about the impact of these parameters on the convergence of PINNs.

read the caption

Figure 1: Training losses of PINNs solving (a) bi-harmonic equation and (b) Poisson equation.

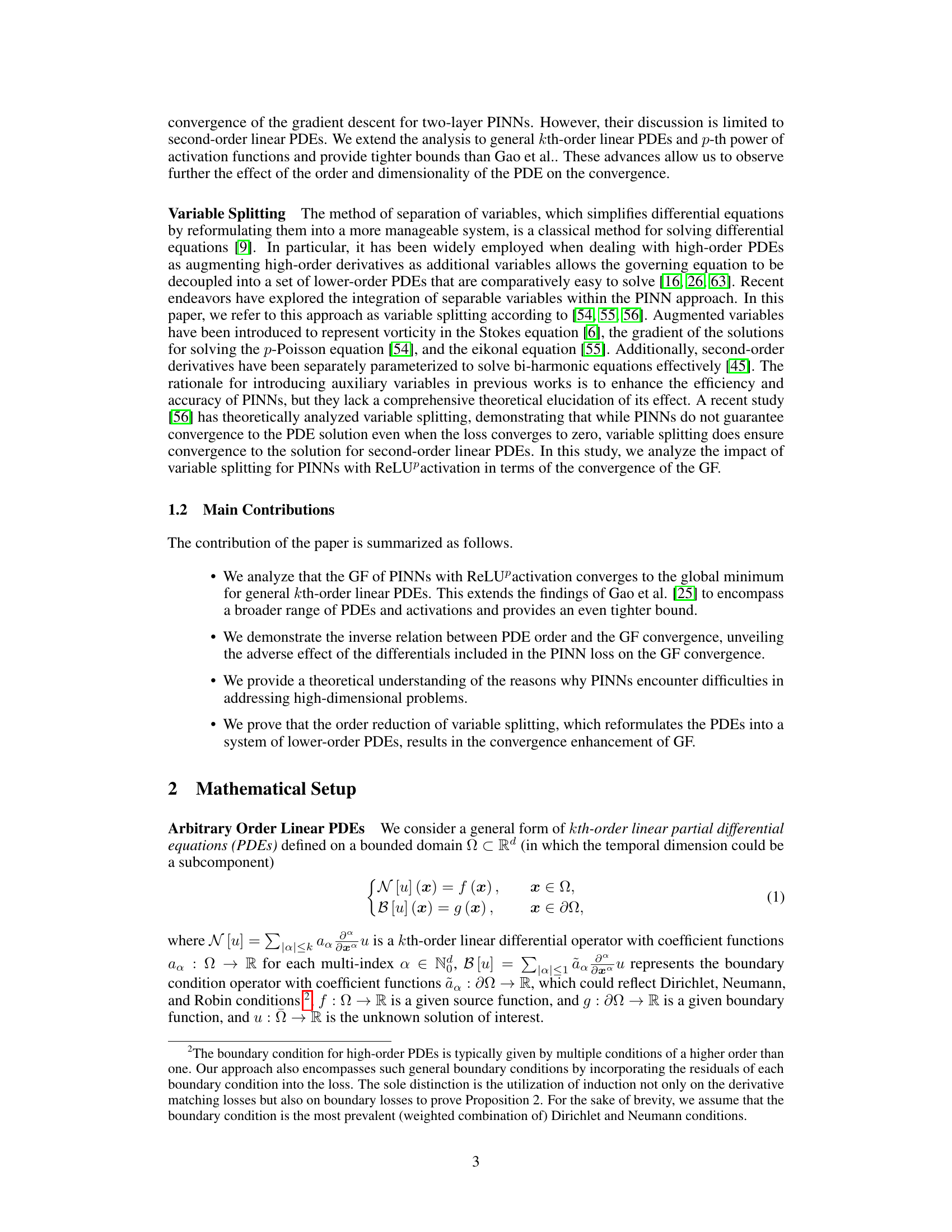

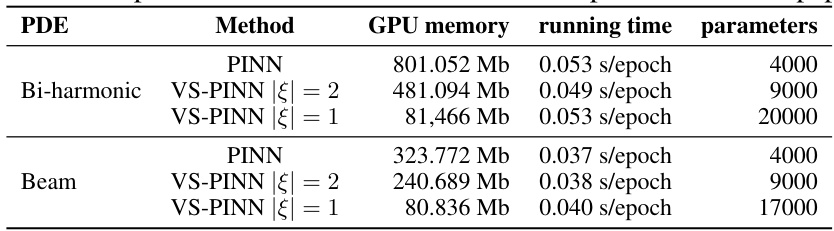

🔼 This table presents the GPU memory usage, running time, and the number of model parameters for the experiments conducted in the paper. It compares PINNs and VS-PINNs (with different splitting levels) for the Bi-harmonic and Beam equations, highlighting the computational efficiency of VS-PINNs, particularly the finer splitting approaches, in terms of reduced memory and parameters.

read the caption

Table 3: Computation costs with width=1000 for experiments on the paper.

In-depth insights#

PINN Convergence#

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) demonstrate promise in solving partial differential equations (PDEs), yet their convergence behavior remains a significant challenge, especially with high-order PDEs. The relationship between PDE order and PINN convergence is inverse: higher-order PDEs hinder convergence. This is due to the increased complexity of calculating higher-order derivatives within the loss function, demanding greater network capacity for accurate approximation. Dimensionality further exacerbates this issue, compounding the difficulty. Variable splitting, a technique that decomposes a high-order PDE into a system of lower-order PDEs, offers a potential solution. By reducing the derivative order in the loss function, it improves convergence likelihood. Theoretical analysis supports this claim and numerical experiments validate its effectiveness. The power of the activation function (e.g., ReLU) also influences convergence, with lower powers generally facilitating better results. Further research could focus on refining the variable splitting approach for optimal performance and exploring the interplay between different activation functions and PDE characteristics.

PDE Order Impact#

The section on “PDE Order Impact” would delve into the crucial relationship between the order of the partial differential equation (PDE) being solved and the convergence properties of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs). A higher-order PDE translates to needing to compute higher-order derivatives of the neural network’s output, significantly increasing the complexity of the optimization problem. The analysis would likely show that higher-order PDEs lead to slower convergence and potentially worse generalization performance. This is because higher-order derivatives are harder to approximate accurately with neural networks, especially with limited training data. The authors would investigate different network architectures, activation functions, and optimization techniques to determine their impact on convergence rates for varying PDE orders. Theoretical analysis, possibly including error bounds, and numerical experiments would be crucial to support the claims. The investigation would likely highlight challenges in optimizing PINNs for high-order PDEs and suggest potential solutions or strategies, such as variable splitting methods to decompose the original PDE into a set of lower-order ones, making the problem more tractable.

Variable Splitting#

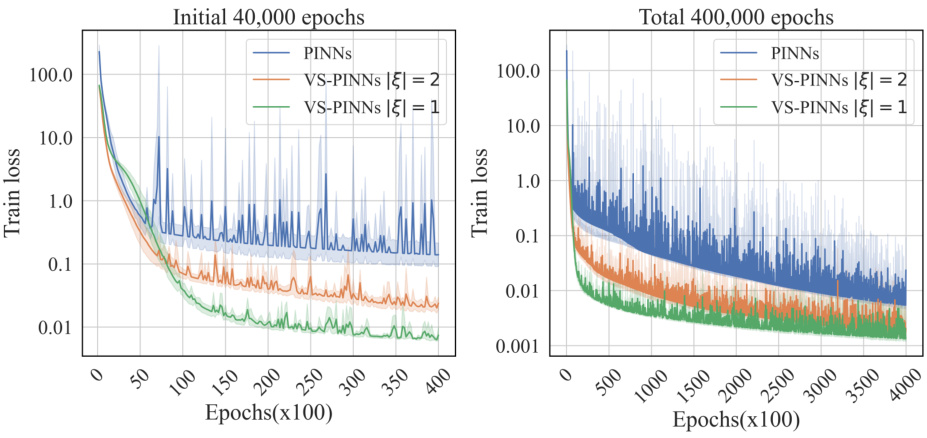

The variable splitting technique, applied within the context of Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), presents a powerful strategy to overcome the limitations imposed by high-order Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). By decomposing a high-order PDE into a system of lower-order PDEs, variable splitting effectively reduces the complexity of the problem. This simplification reduces the computational burden of calculating higher-order derivatives, which is a significant challenge in PINNs. This method enhances convergence of gradient descent, improving the accuracy and efficiency of the neural network’s approximation. The theoretical analysis suggests that variable splitting’s effectiveness increases as the order of the original PDE or the dimensionality of the problem increases, thereby mitigating the effects of the curse of dimensionality. The numerical experiments further support these findings, demonstrating the practical benefits of this approach. However, while variable splitting offers significant advantages, it also increases the number of parameters and thus the model complexity, which is a trade-off that needs to be considered.

High-Dim. Effects#

The section on “High-Dimensional Effects” in this research paper would likely delve into the challenges posed by high-dimensionality when applying Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) to solve partial differential equations (PDEs). A key insight would be that the curse of dimensionality is exacerbated by the order of the PDE. Higher-order PDEs necessitate a wider neural network to guarantee convergence, meaning the computational cost escalates dramatically with increasing dimensions. The paper likely demonstrates this through theoretical analysis, revealing how the width of the network needed for convergence increases exponentially with both dimensionality and PDE order. Incorporating high-order differential operators into the loss function of PINNs further amplifies this sensitivity to dimensionality. This is in contrast to standard deep learning models which don’t incorporate such operators in the loss function. The analysis would likely provide valuable insights into why PINNs often struggle with high-dimensional problems and offer a theoretical underpinning for this empirically observed behavior. Variable splitting, a technique to decompose high-order PDEs into systems of lower-order PDEs, may be presented as a potential solution to mitigate these high-dimensional challenges.

Future Research#

The “Future Research” section of this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to nonlinear PDEs would be a significant advancement, moving beyond the current focus on linear equations and broadening the applicability of the findings. Investigating alternative activation functions beyond ReLU, and their effect on convergence, could reveal superior optimization strategies. A deeper exploration of variable splitting strategies, perhaps optimizing the splitting method itself or examining different splitting approaches, could lead to even more efficient solutions to high-order PDEs. Furthermore, empirical validation on a broader range of complex, real-world problems is needed to fully demonstrate the robustness and generalizability of the proposed variable splitting technique. Finally, research into the inherent limitations of PINNs, such as their sensitivity to dimensionality and the challenge of ensuring global convergence, should continue to refine this important field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

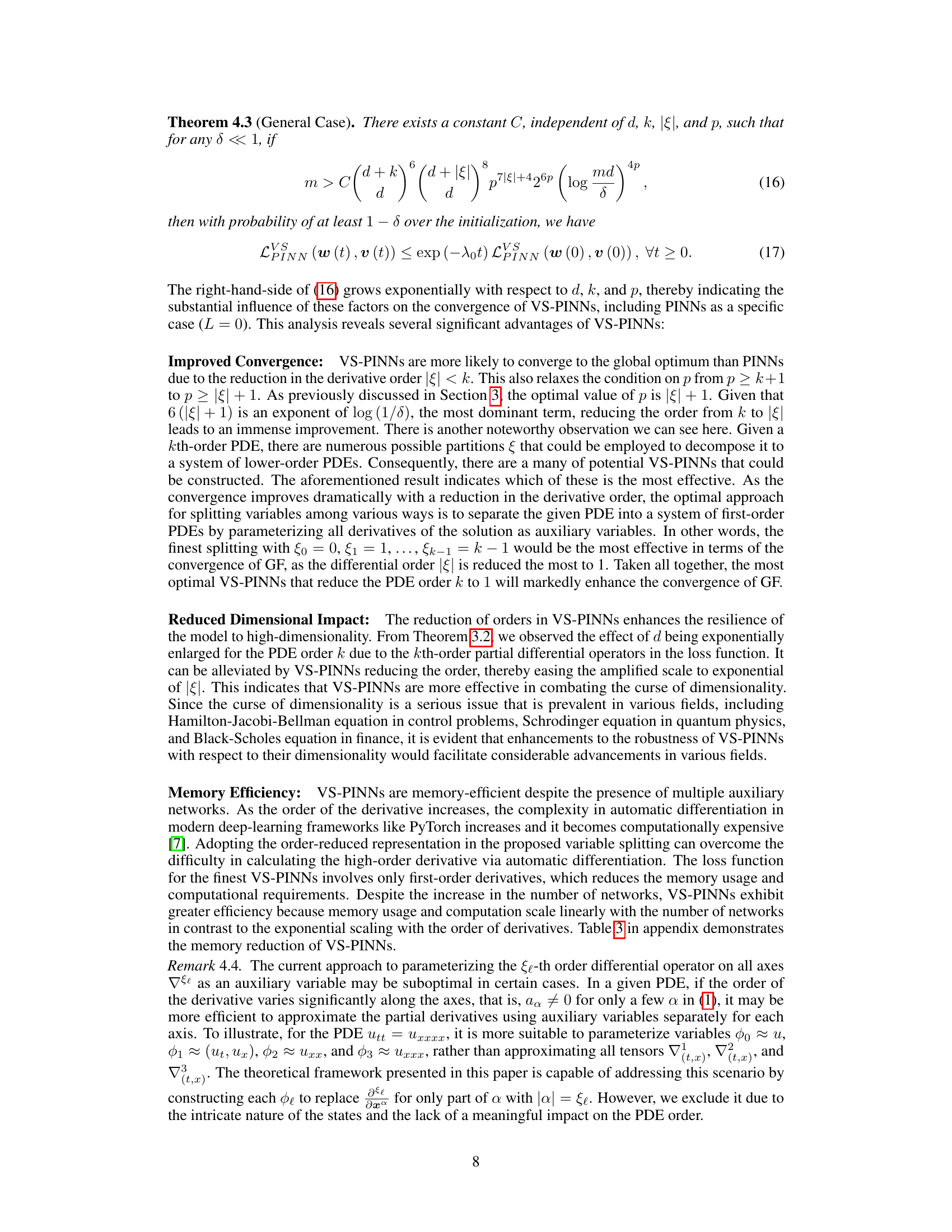

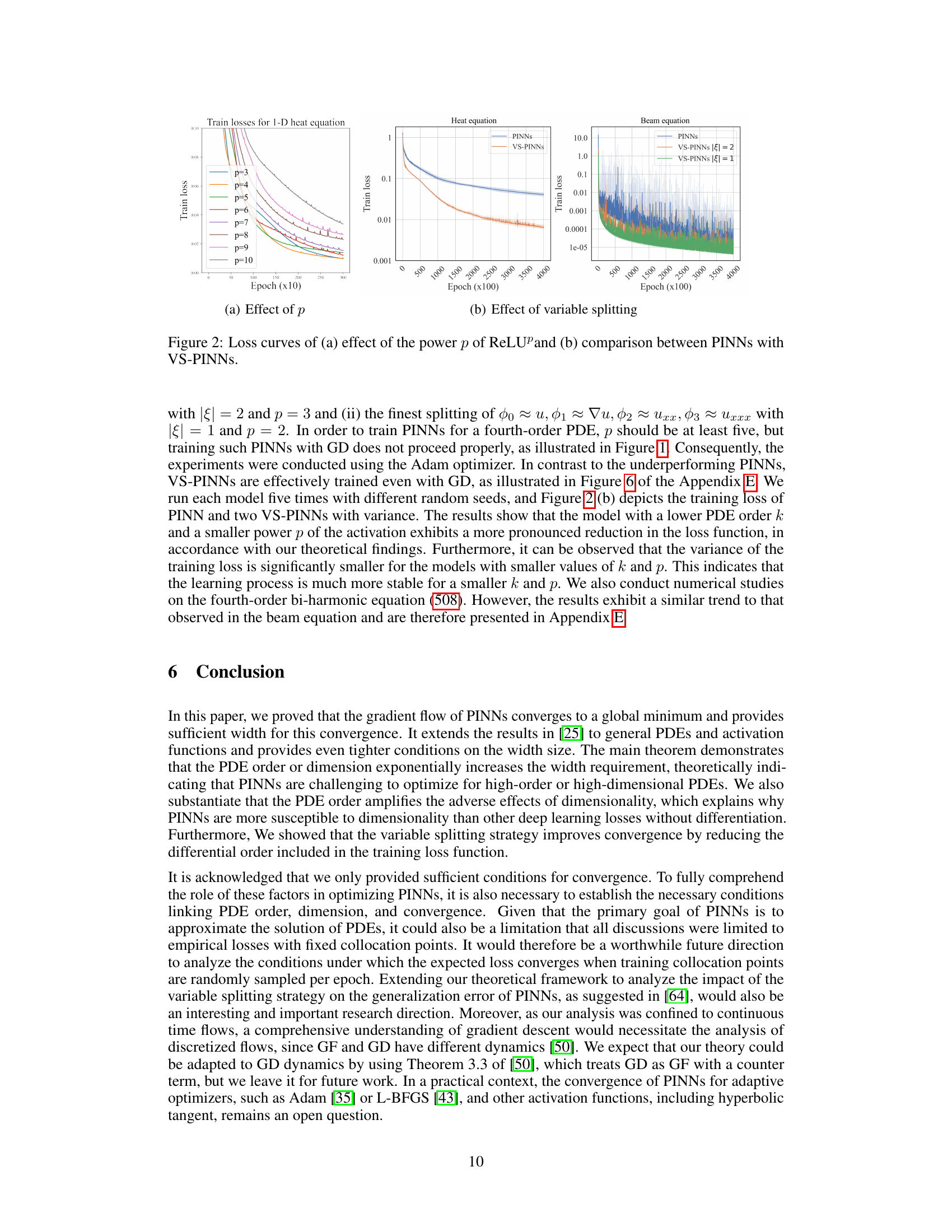

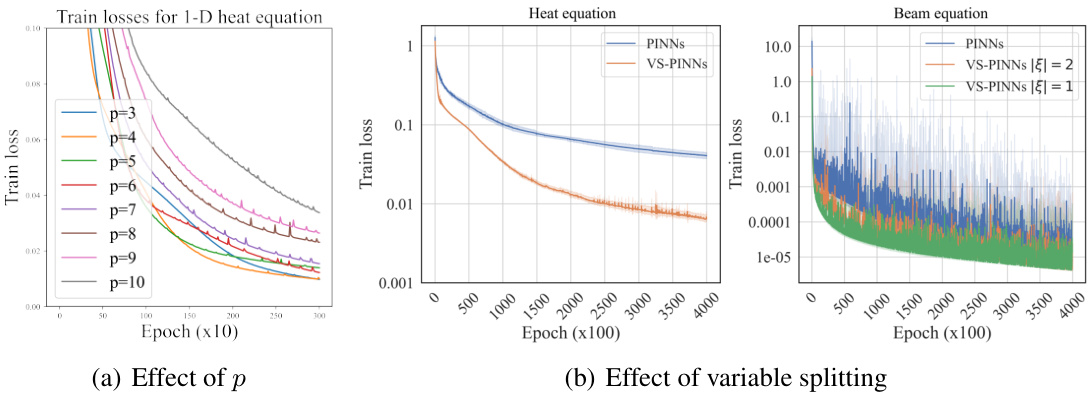

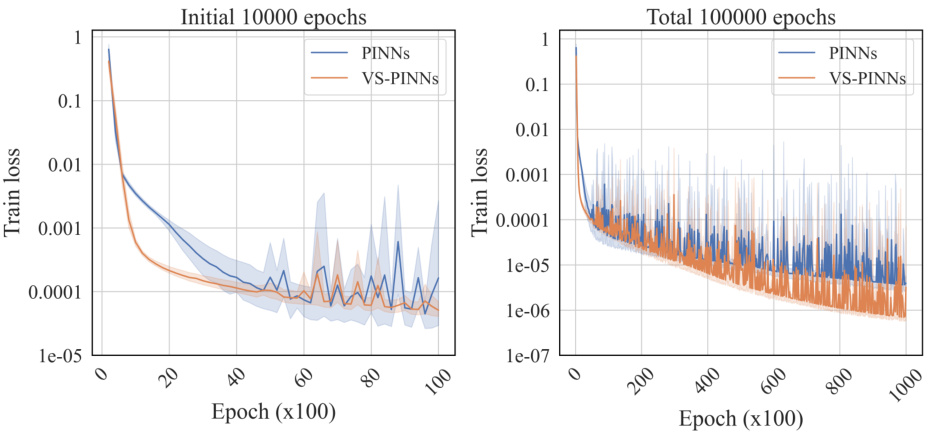

🔼 This figure presents the experimental results that validate the theory. The figure is composed of two subfigures. Subfigure (a) shows the effect of the power p of the ReLU activation function on the training loss of PINNs. The results show that the convergence of loss is enhanced as p decreases, which supports the theoretical finding that the smaller p is, the more likely the gradient descent will converge. Subfigure (b) shows a comparison between PINNs and VS-PINNs for the second-order heat equation. The results show that the training loss for VS-PINNs converges more effectively than that of PINNs, which indicates that VS-PINNs, which optimize a loss function incorporating lower-order derivatives using networks with smaller p, facilitate convergence of GD.

read the caption

Figure 2: Loss curves of (a) effect of the power p of ReLUp and (b) comparison between PINNs with VS-PINNS.

🔼 This figure displays two subfigures. Subfigure (a) shows the impact of the power (p) of the ReLU activation function on the training loss of PINNs for a second-order heat equation. It demonstrates that lower p values lead to faster convergence and better stability. Subfigure (b) compares the training loss curves of PINNs and VS-PINNs (Variable Splitting PINNs) for the same second-order heat equation. It illustrates that VS-PINNs converge significantly faster than standard PINNs, highlighting the effectiveness of the variable splitting technique in improving convergence.

read the caption

Figure 3: Loss curves of (a) effect of the power p of ReLUp and (b) comparison between PINNs with VS-PINNS.

🔼 This figure displays the training loss curves for PINNs trained on the bi-harmonic and Poisson equations. The plots show how the training loss decreases with epochs (iterations) of training for different network widths (m) and different powers of the ReLU activation function (p). Each subplot shows results for a given PDE (bi-harmonic or Poisson) with different activation functions and network widths. The shaded regions around the curves represent the variance observed over multiple runs. The figure aims to illustrate the impact of network width and the power of the ReLU activation function on the convergence behavior of PINNs, particularly as the order of the PDE increases.

read the caption

Figure 1: Training losses of PINNs solving (a) bi-harmonic equation and (b) Poisson equation.

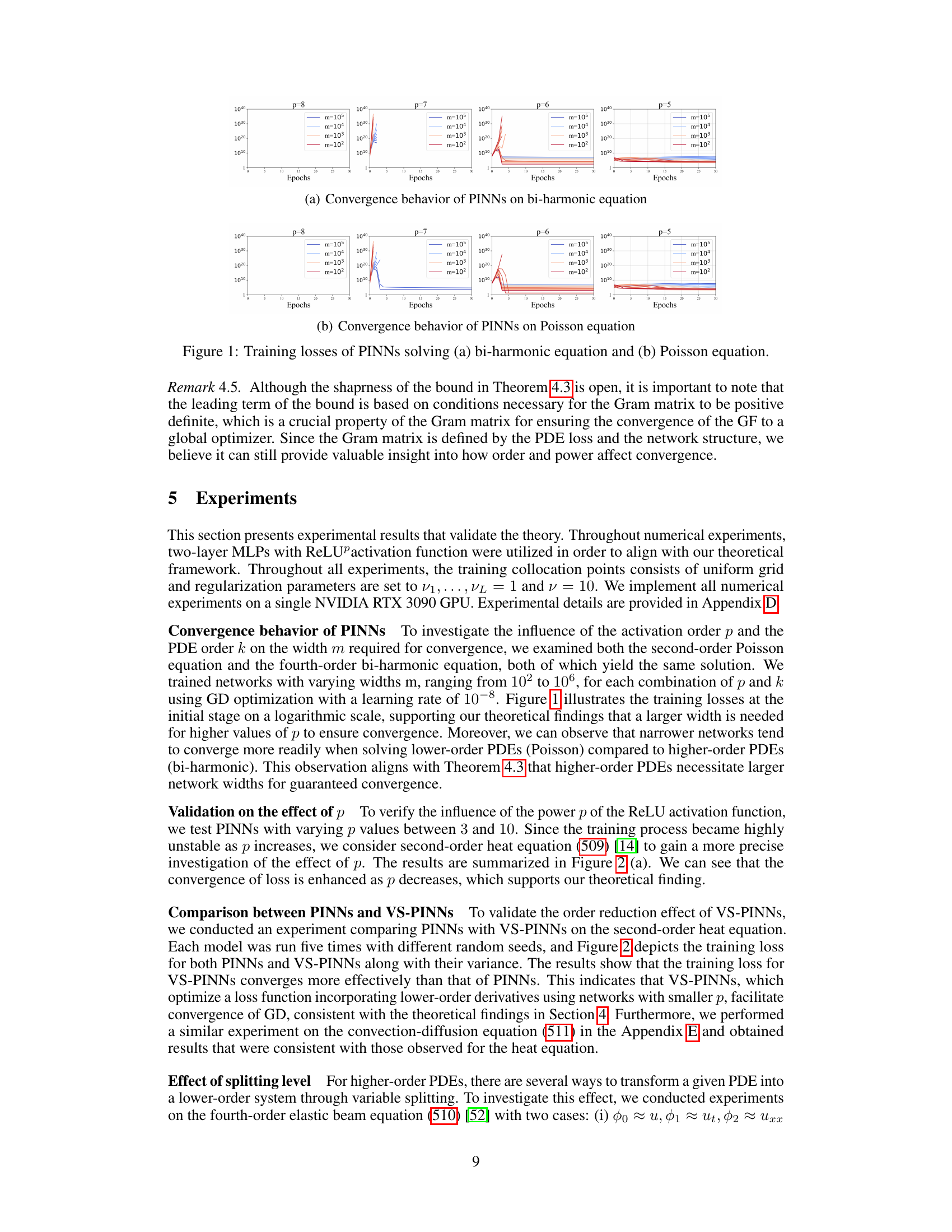

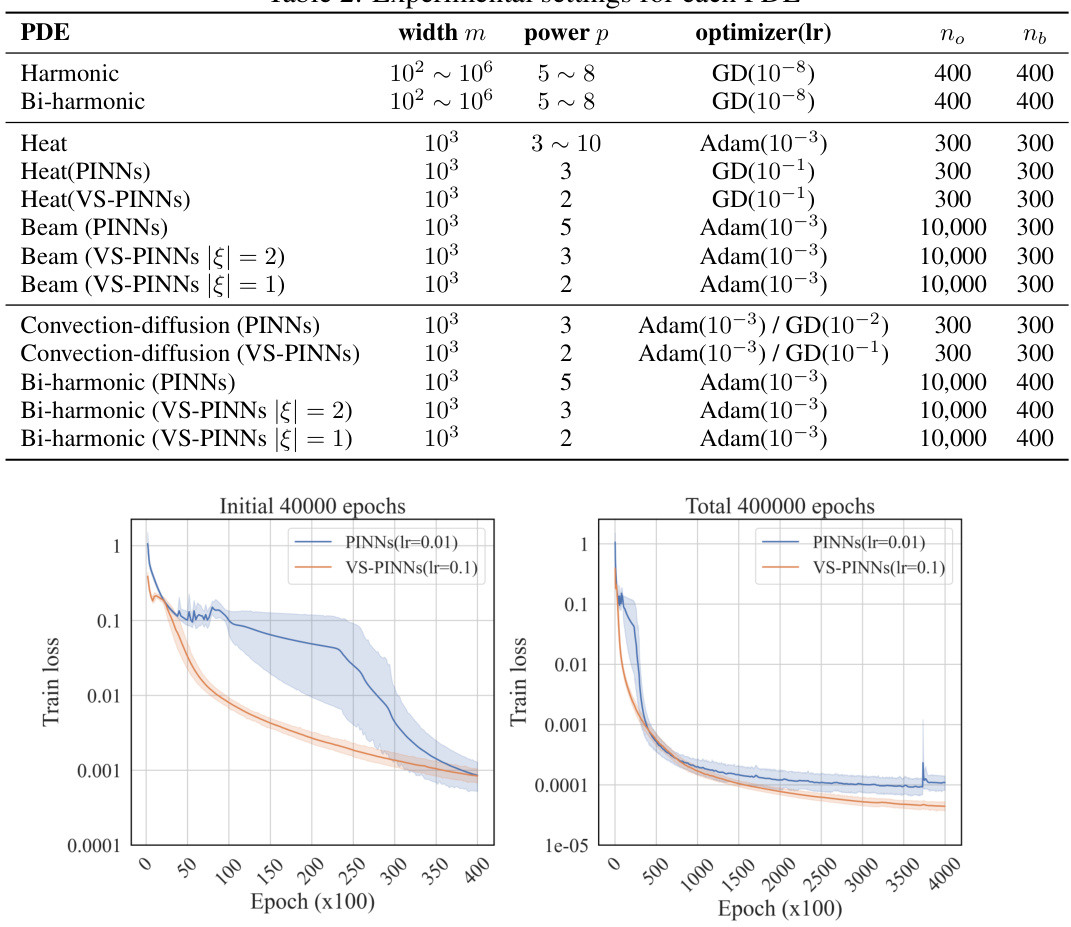

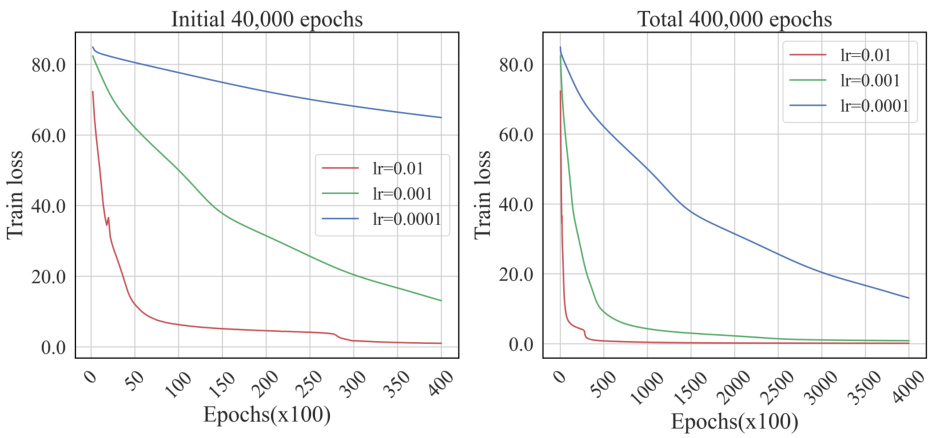

🔼 This figure shows the training loss curves of VS-PINNs trained using gradient descent with different learning rates for the elastic beam equation. The results demonstrate the impact of varying learning rates on the convergence behavior, illustrating how optimal selection of the learning rate affects the speed and stability of convergence towards lower loss values. Multiple runs with different random seeds are included to show the variation in results.

read the caption

Figure 6: Loss of VS-PINNs trained by gradient descent with variant learning rates.

🔼 This figure displays the training loss curves of VS-PINNs (Variable Splitting Physics-Informed Neural Networks) trained using gradient descent with different learning rates. Two plots are shown: one for the initial 40,000 epochs of training and one for the total 400,000 epochs. Each plot shows three curves, representing different learning rates (lr = 0.01, lr = 0.001, lr = 0.0001). The figure illustrates how the learning rate affects the convergence speed and stability of the VS-PINN training process. The results demonstrate the impact of the learning rate on the training loss, highlighting the need for careful selection of the learning rate to ensure efficient and stable convergence in VS-PINNs.

read the caption

Figure 6: Loss of VS-PINNs trained by gradient descent with variant learning rates.

More on tables

🔼 This table shows the number of nonzero elements present in different blocks of the Gram matrix G. The Gram matrix is a key component in the convergence analysis of the gradient flow. Each block represents interactions between different parts of the loss function: residuals of the PDE, boundary conditions, and gradient matching terms. The number of nonzero elements reflects the complexity of these interactions, which is directly related to the convergence behavior of the PINNs.

read the caption

Table 1: The number of nonzero elements in blocks in G.

🔼 This table presents the GPU memory usage, running time per epoch, and the number of model parameters for different PINN models (standard PINN and VS-PINNs with different splitting levels) used in the experiments of the paper. It highlights the computational resource requirements of various models to solve PDEs of varying orders and complexities.

read the caption

Table 3: Computation costs with width=1000 for experiments on the paper.

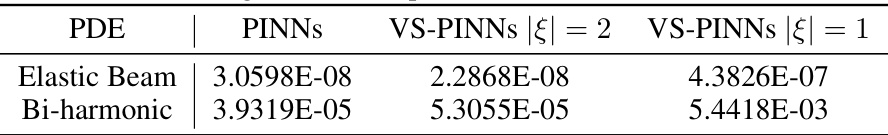

🔼 This table presents the average Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the predicted solutions and the exact solutions for the elastic beam and bi-harmonic equations. Three different methods are compared: PINNs (vanilla Physics-Informed Neural Networks) and two variations of VS-PINNs (Variable Splitting PINNs) with different splitting levels (|ξ| = 2 and |ξ| = 1). The results show the MSE values obtained for each method and equation.

read the caption

Table 4: The average of Mean Square Error (MSE) with exact solution.

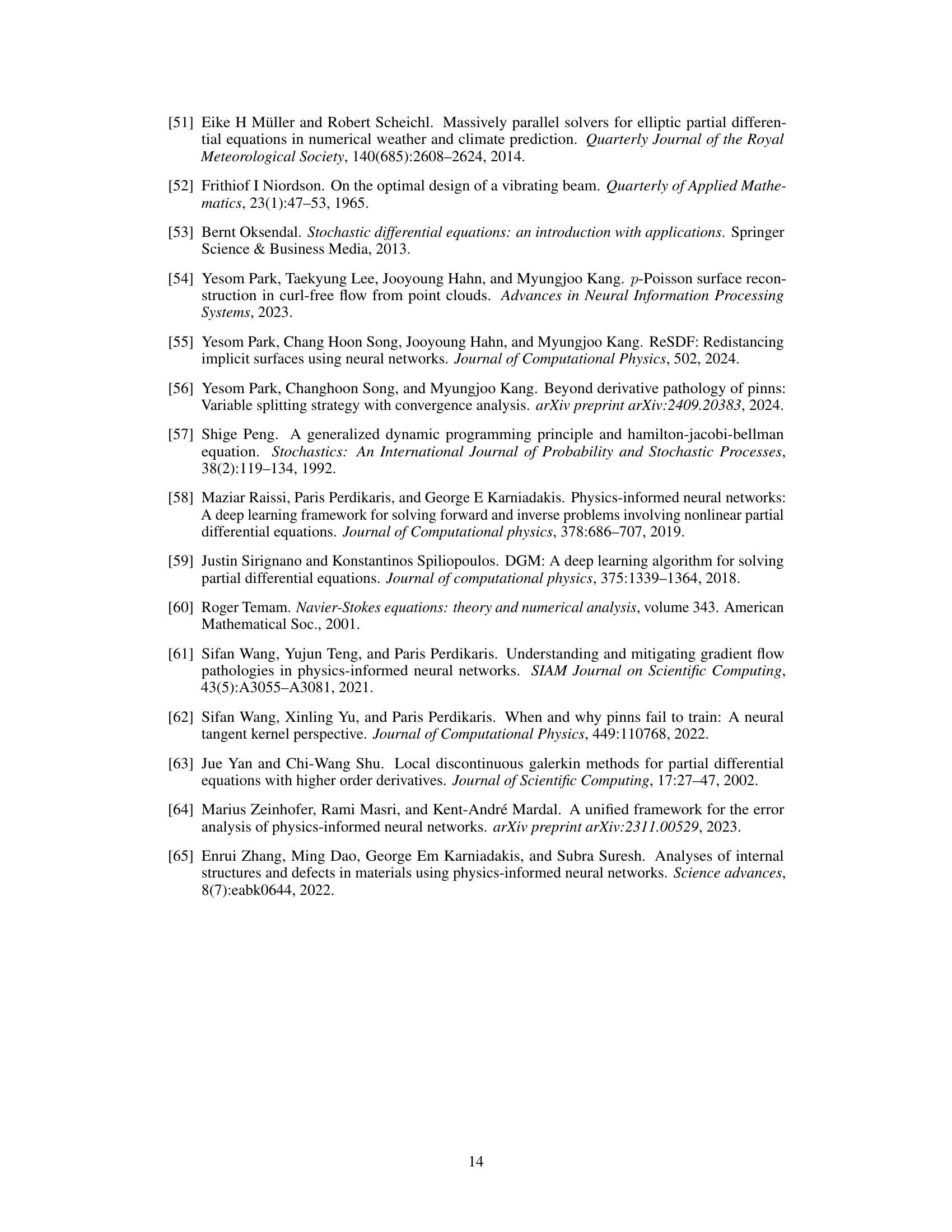

Full paper#