TL;DR#

Current neural network methods for processing surfaces often ignore or use overly complex surface representations. This can lead to inefficient processing and limit the ability to capture essential surface features. The paper addresses these challenges by proposing a new approach.

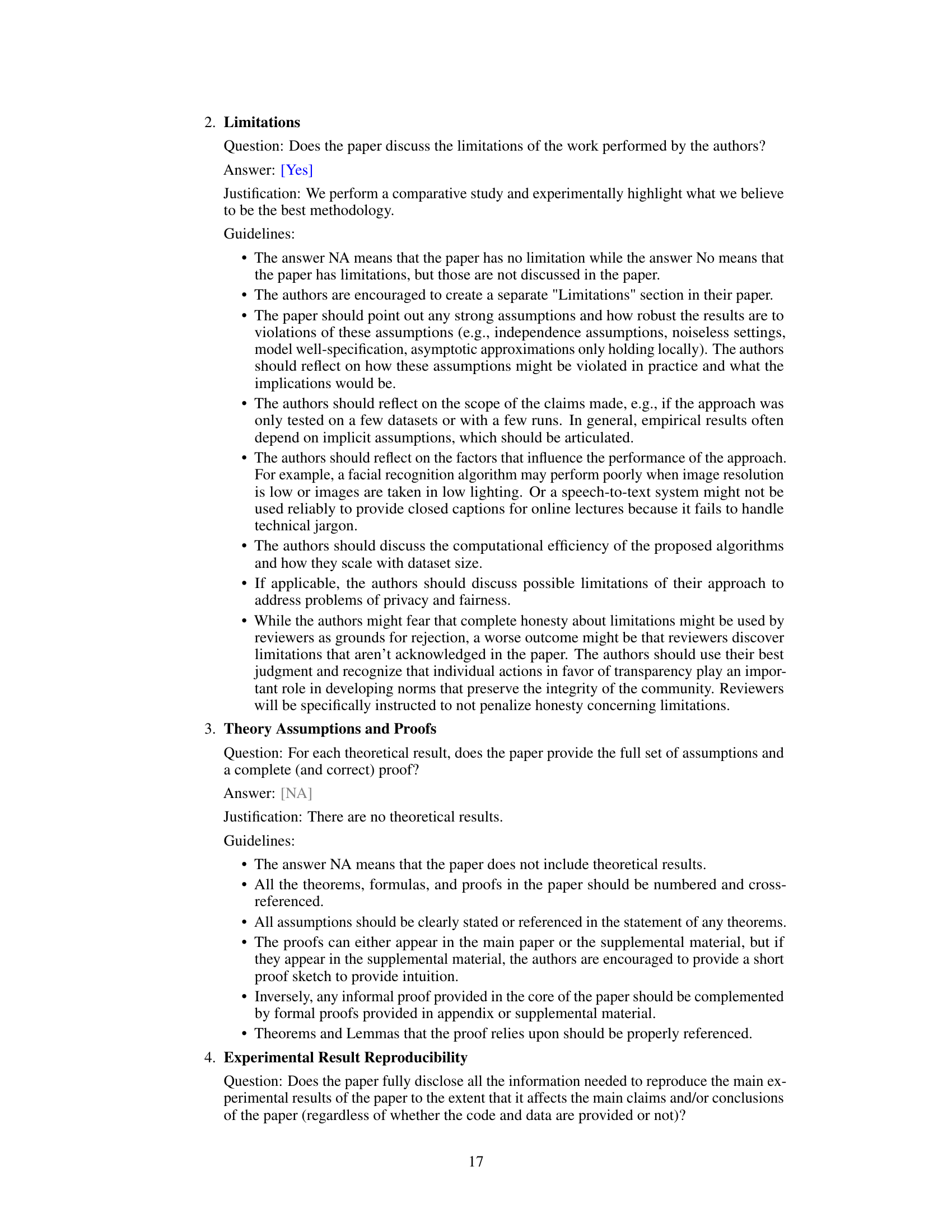

The paper proposes using principal curvatures – inherent geometric properties of surfaces – as direct input to neural networks for surface processing. Experiments using the shape operator demonstrate substantial performance improvements on segmentation and classification tasks, while achieving far greater computational efficiency than current state-of-the-art methods. The approach significantly enhances neural network processing of surfaces by providing concise, informative input that allows networks to leverage intrinsic geometric features.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel and efficient method for neural network surface processing. Principal curvatures, as opposed to computationally expensive methods, are used as input, leading to significant performance gains in segmentation and classification tasks. This work has implications for various fields relying on surface processing, including medical imaging and computer graphics, opening new avenues for research in efficient and expressive surface representations.

Visual Insights#

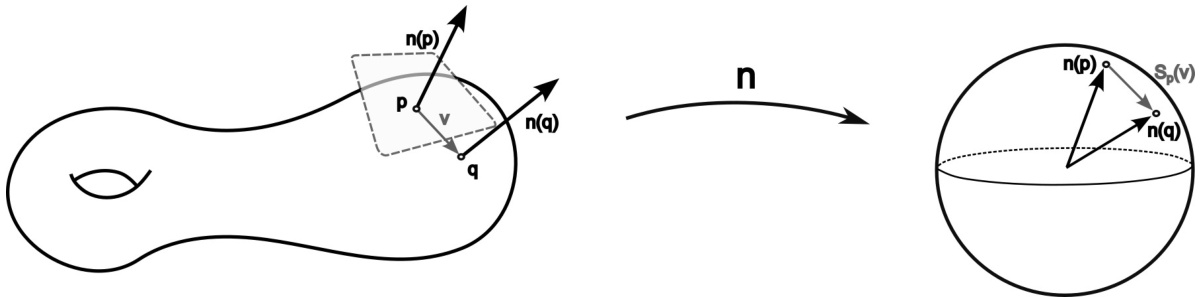

🔼 The figure illustrates how the shape operator can be visualized using the Gauss map. The left panel shows a point p on a surface, with a tangent vector v and the surface normals at nearby points p and q. The middle panel shows a mapping from the surface to the unit sphere (Gauss map), where each point on the surface is mapped to its corresponding normal vector. The right panel depicts this mapping on the sphere, with the tangent vector v mapped to the vector Sp(v) which represents how the normal vector changes with respect to the tangent vector v at point p. The length and orientation of Sp(v) provide information about the curvature of the surface at point p.

read the caption

Figure 1: The shape operator may be visualised via the Gauss map.

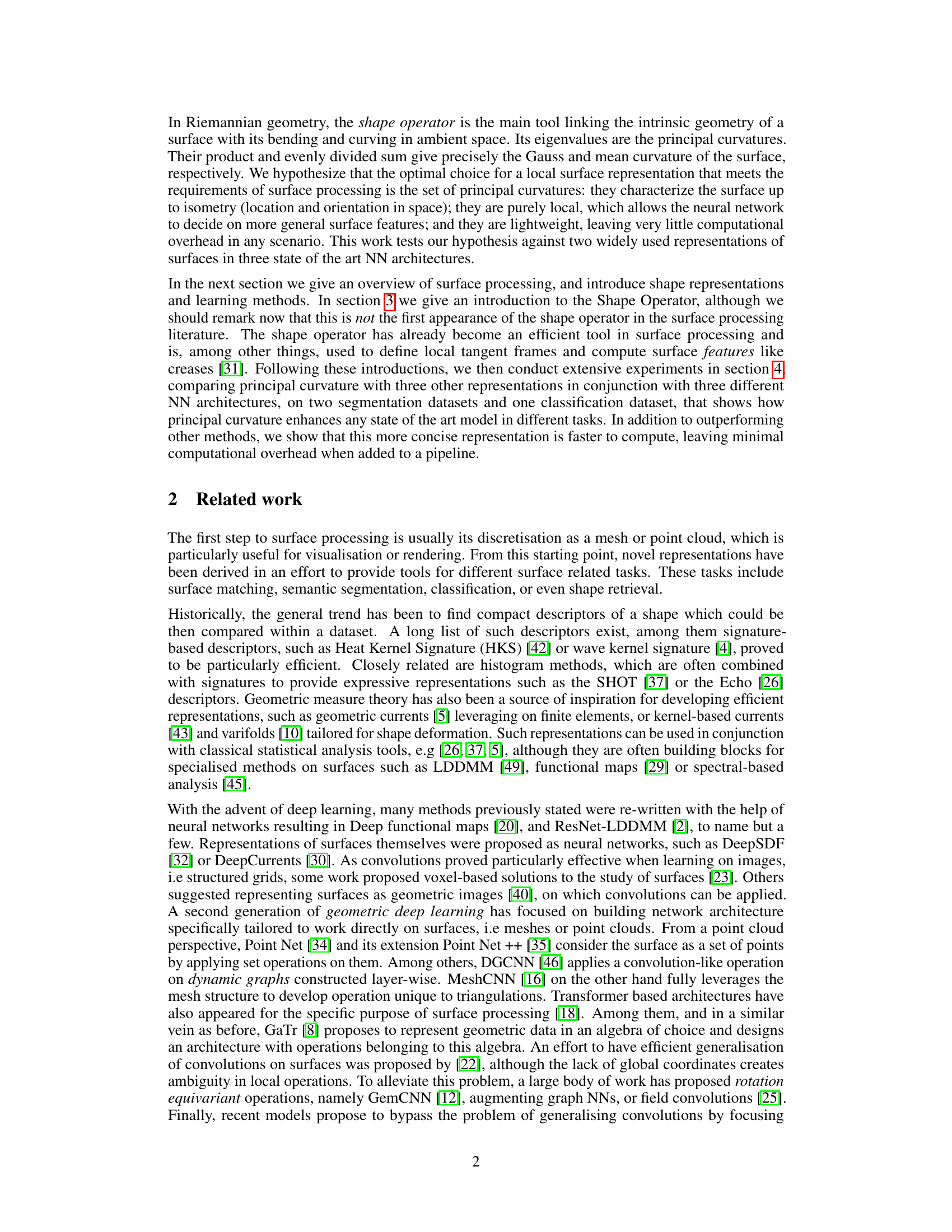

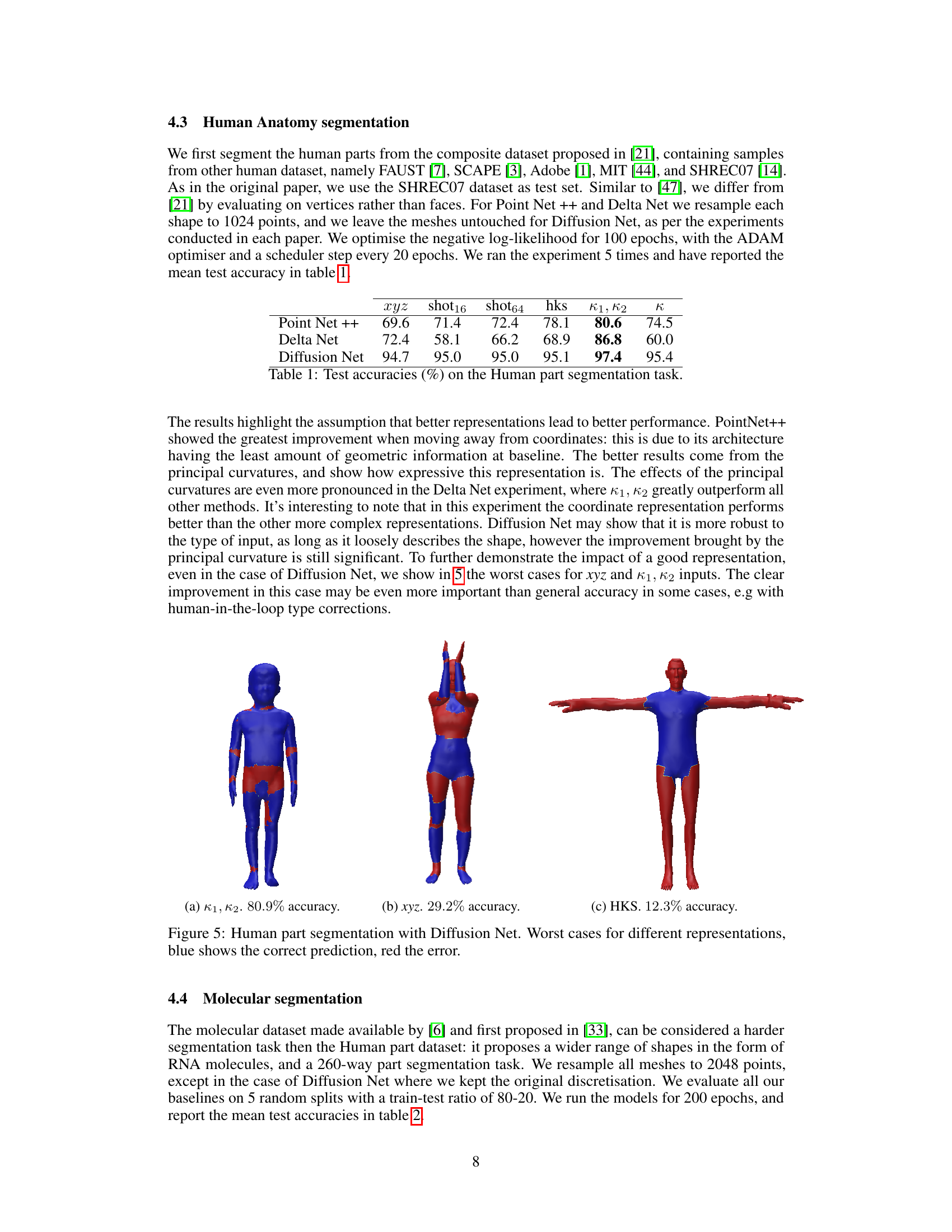

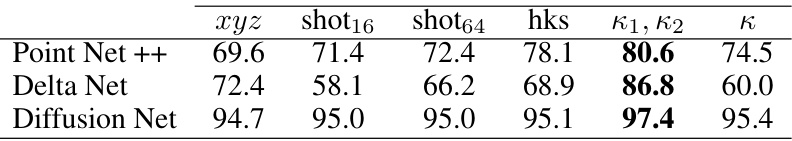

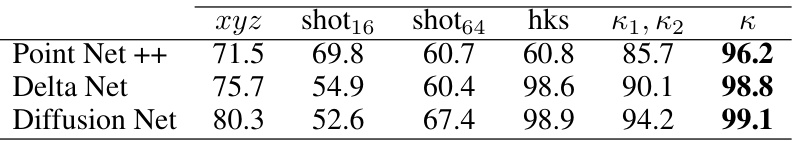

🔼 This table presents the results of human part segmentation task using different input representations (xyz, shot16, shot64, hks, k1,k2, k) and three different neural network architectures (PointNet++, DeltaNet, DiffusionNet). The accuracies are presented as percentages and are averaged over five runs.

read the caption

Table 1: Test accuracies (%) on the Human part segmentation task.

In-depth insights#

Curvature’s Power#

A hypothetical section titled “Curvature’s Power” in a research paper on neural network surface processing would likely explore how leveraging surface curvature, specifically principal curvatures, significantly enhances the performance and efficiency of neural network architectures. The core argument would center on curvature’s inherent geometric properties, emphasizing its invariance to surface position and orientation, unlike raw coordinate data. This invariance makes curvature an ideal feature for tasks like shape classification and segmentation, as it focuses on intrinsic properties rather than extrinsic ones. The paper would likely present experimental evidence demonstrating that using principal curvatures as input, possibly through the shape operator, leads to substantial performance gains compared to methods using extrinsic coordinates or other, less informative surface descriptors. Furthermore, the discussion would likely highlight the computational advantages of using curvature, as it’s computationally less expensive than many alternative methods, while still capturing essential shape information. The section could also discuss the choice of representation (e.g., Gaussian curvature versus principal curvatures) and its impact on network performance, perhaps showing the strengths and limitations of each approach. Overall, the “Curvature’s Power” section would argue that adopting a curvature-based representation revolutionizes neural network surface processing by improving both accuracy and efficiency.

Shape Operator#

The shape operator is a crucial concept in differential geometry, providing a powerful tool to analyze the intrinsic and extrinsic properties of surfaces. Its eigenvalues directly correspond to the principal curvatures, which quantify the bending of the surface along principal directions. These curvatures are fundamental descriptors of shape, invariant to rigid transformations (translations and rotations), thereby capturing inherent geometric properties. The shape operator’s matrix representation reveals essential geometric information, with its determinant yielding the Gaussian curvature (relating to surface’s overall bending) and its trace giving the mean curvature (relating to average bending). The efficacy of the shape operator lies in its ability to connect the surface’s intrinsic geometry to its embedding in ambient space, simplifying analysis by expressing curvature properties in a clear, concise manner. By utilizing the shape operator, the research explores the effectiveness of employing principal curvatures as neural network input, significantly improving surface processing tasks. This choice is motivated by the shape operator’s concise yet expressive representation, proving computationally efficient while capturing key geometric details crucial for efficient surface analysis within neural network architectures.

Neural Nets#

The application of neural networks to surface processing is a rapidly evolving field. Early approaches often neglected surface representation, using simple coordinate inputs. More sophisticated methods began incorporating curvature information, recognizing its inherent geometric significance. However, these methods sometimes employed excessively complex representations, hindering efficiency. This paper advocates for a more focused approach: using principal curvatures as direct input to neural networks. This offers a balance of expressive power and computational efficiency. Principal curvatures encode intrinsic surface geometry, offering invariance to transformations like rotation and translation. The authors demonstrate improved performance across various tasks and network architectures, suggesting the superiority of curvature-based inputs over extrinsic coordinate methods and other less concise feature representations such as Heat Kernel Signatures. This streamlined representation leads to faster processing and reduces computational overhead. Future work could explore the optimal integration of curvature with more advanced network architectures and investigate the performance across a wider range of datasets.

Benchmarking#

A robust benchmarking section is crucial for validating the claims of a research paper. It should involve comparing the proposed method against existing state-of-the-art techniques using multiple metrics and datasets. Careful selection of benchmarks is key; they must be relevant to the problem being addressed and representative of real-world scenarios. The benchmarking process should be meticulously documented to ensure reproducibility. Transparency in methodology is paramount; any limitations or challenges encountered during the benchmarking process must be openly discussed. Furthermore, statistical significance should be assessed, providing confidence that the observed improvements aren’t due to chance. Finally, a thoughtful analysis of the results, considering potential reasons for success or failure, leads to more valuable insights and a stronger overall contribution.

Noisy Data#

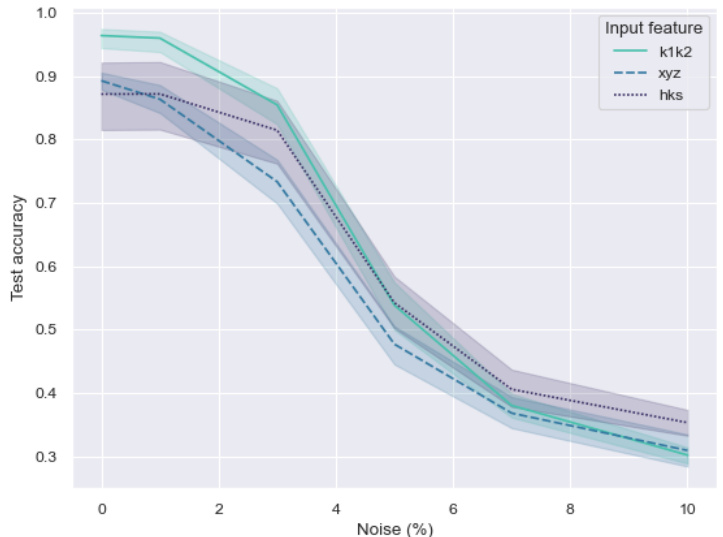

The section on “Noisy Data” would ideally assess the robustness of the proposed principal curvature representation against noise, a critical factor in real-world applications where data is often imperfect. A thorough analysis would involve adding varying levels of noise (e.g., Gaussian noise with different standard deviations) to the input surface data and measuring the resulting performance drop in segmentation and classification tasks. Comparing the performance degradation of principal curvatures to that of other representations (e.g., HKS, extrinsic coordinates) under various noise levels is essential for demonstrating its advantages and limitations. The results could reveal whether principal curvatures offer improved robustness over alternative methods or if they are particularly sensitive to noise in certain regimes. Visualizations showing the effect of noise on the input data and the corresponding changes in principal curvatures are valuable. The impact of noise levels on computational efficiency should also be examined. In summary, this section should provide a quantitative and qualitative assessment of the algorithm’s resilience to noisy input data, contributing valuable insights into its practical applicability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

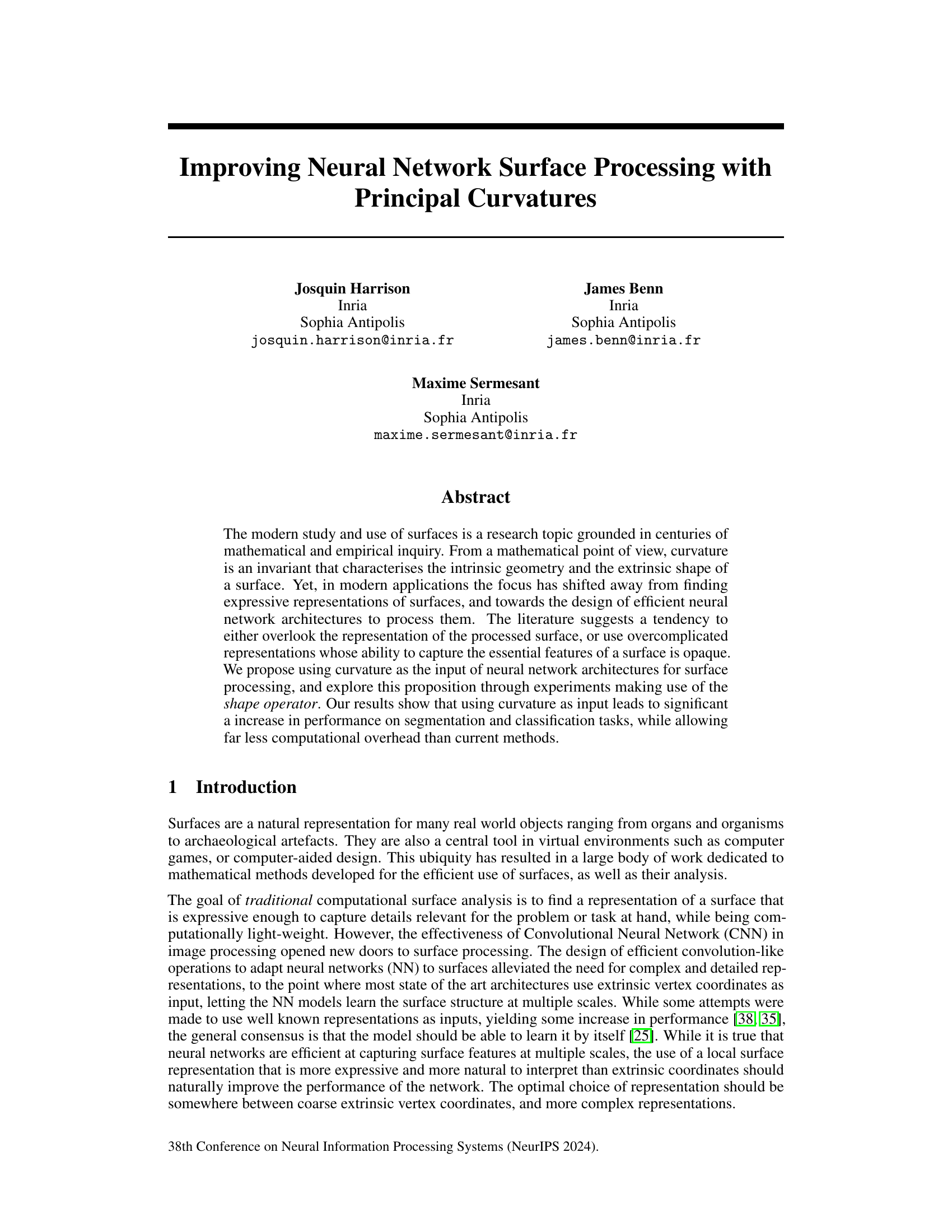

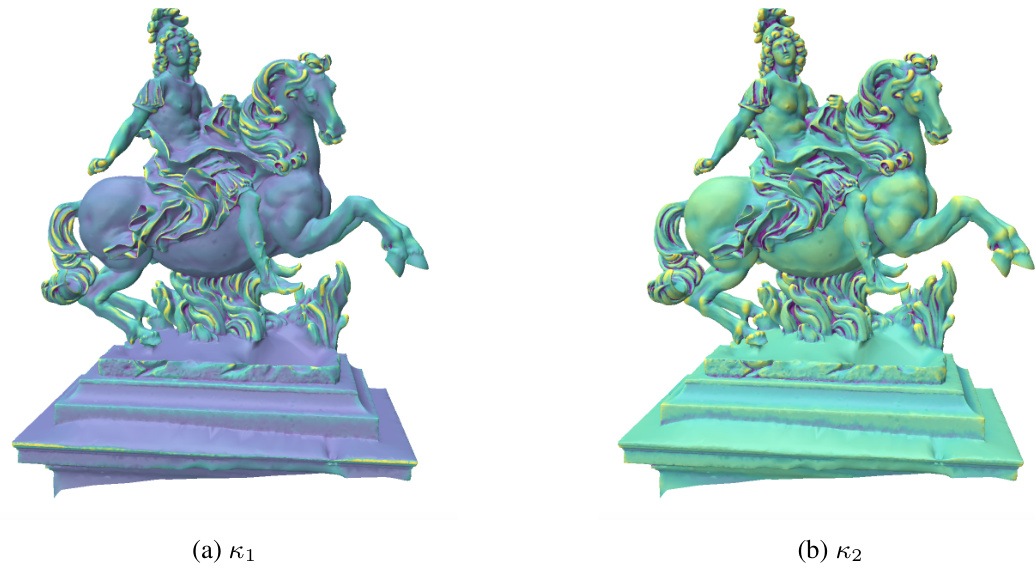

🔼 This figure shows a 3D model of a Louis XIV statue. It visualizes the principal curvatures (κ1 and κ2) of the statue’s surface. The color-coding likely represents the magnitude or direction of curvature, with different colors indicating variations in the surface’s bending and shape. The image likely serves to illustrate the use of principal curvatures as a representation for surface processing in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 2: Principal curvature visualisation of a Louis XIV statue.

🔼 This figure shows examples from three different datasets used in the experiments described in the paper. (a) shows examples of human poses from a human pose dataset. (b) shows examples of molecules from a molecular dataset. (c) shows examples of shapes from the SHREC'11 dataset, which is used for shape classification.

read the caption

Figure 3: Samples of the segmentation and classification datasets used for experiments.

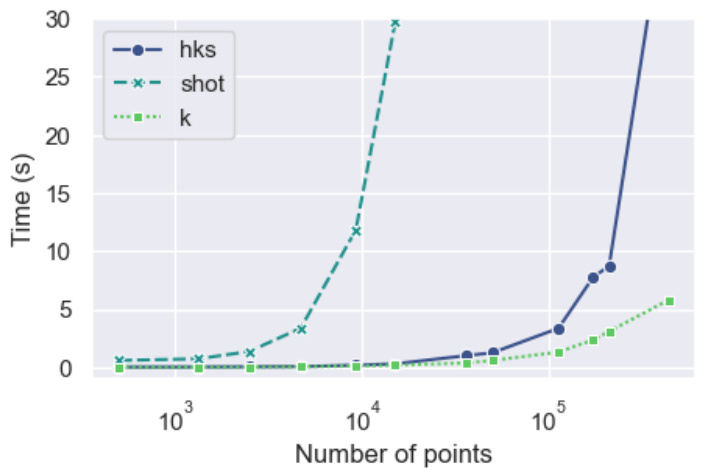

🔼 This figure shows the computation time for three different surface representations (HKS, SHOT, and curvature) and extrinsic coordinates as a function of the number of points in the mesh. It demonstrates the computational efficiency of curvature compared to other representations, particularly as the mesh size increases. Curvature consistently shows faster computation times, highlighting its computational advantages for surface processing tasks.

read the caption

Figure 4: Time of computation for each representation with respect to the number of points in a mesh.

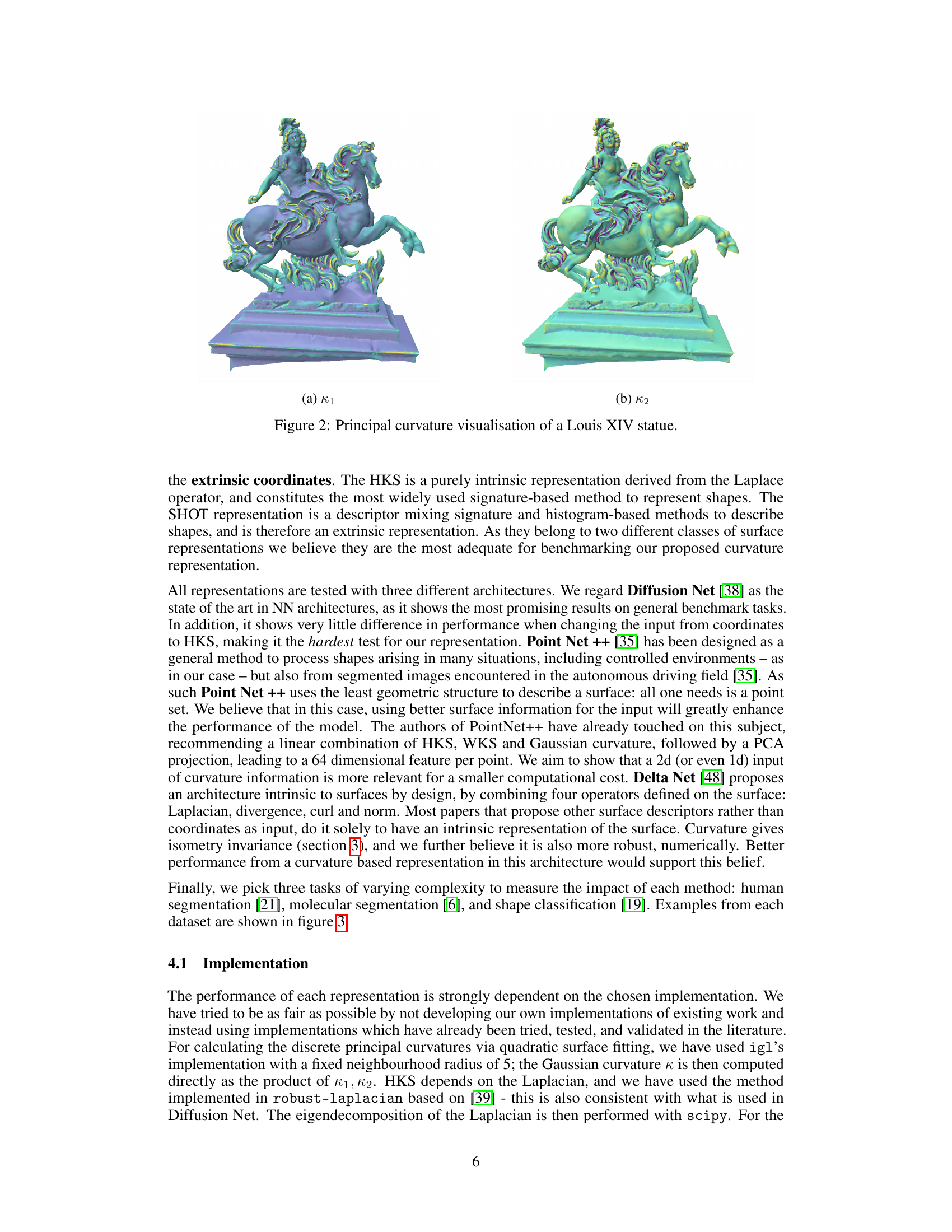

🔼 This figure shows the worst-case scenarios for human part segmentation using three different input representations: principal curvatures (κ1, κ2), extrinsic coordinates (xyz), and Heat Kernel Signatures (HKS). The images illustrate the segmentation results, where blue indicates correctly segmented parts and red represents errors. The figure highlights the significant improvement achieved using principal curvatures, showcasing a far higher accuracy (80.9%) compared to extrinsic coordinates (29.2%) and HKS (12.3%).

read the caption

Figure 5: Human part segmentation with Diffusion Net. Worst cases for different representations, blue shows the correct prediction, red the error.

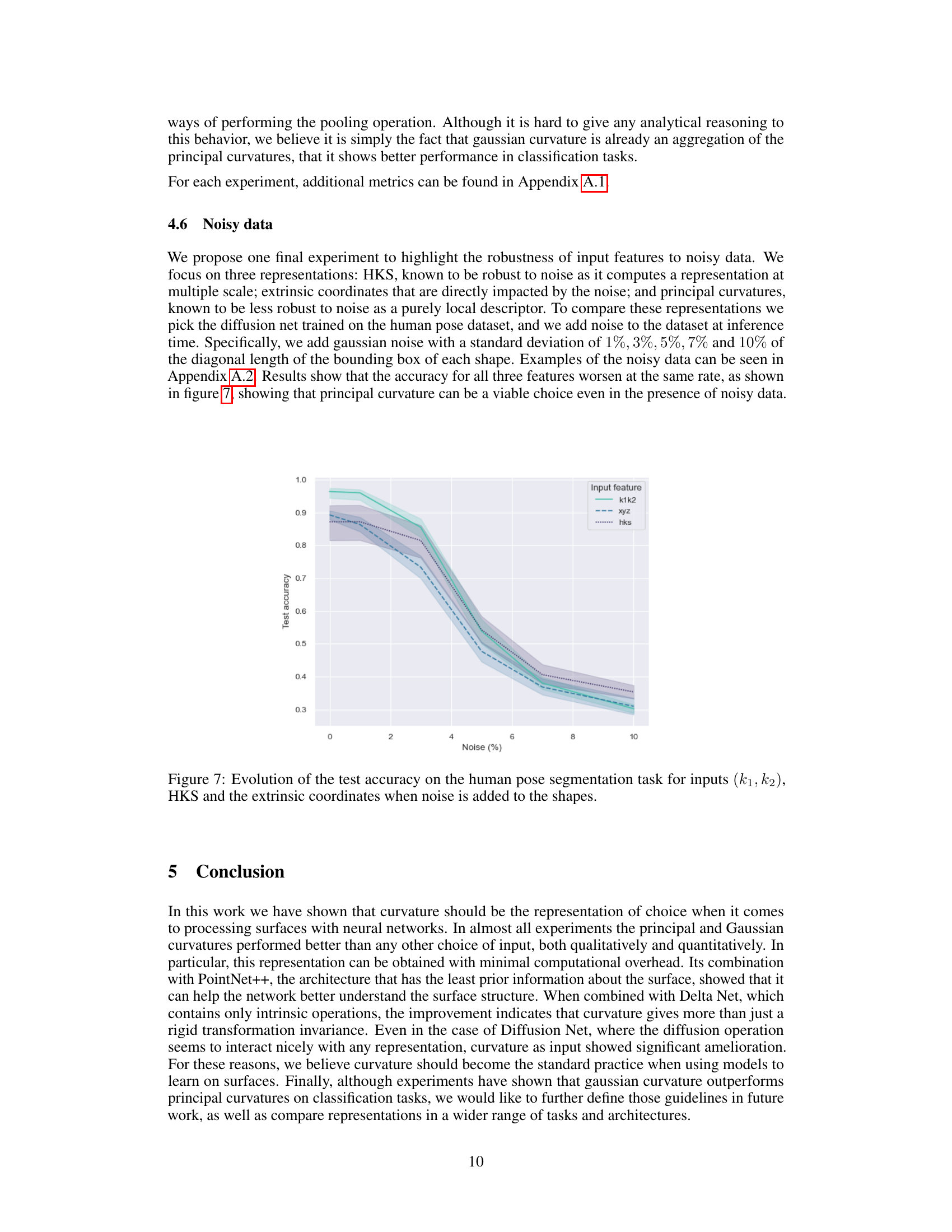

🔼 This figure shows the evolution of test accuracy with 95% confidence intervals for different surface representations (κ, k1k2, hks, xyz, shot16, shot) across multiple folds using the Diffusion Net architecture on the SHREC'07 dataset. The x-axis represents the epoch number, and the y-axis represents the test accuracy. The plot helps visualize the convergence speed and stability of different representations during the training process. It demonstrates the performance of various methods for representing surfaces, showing their accuracy and variability over epochs.

read the caption

Figure 6: Evolution of the test accuracy with 95% confidence interval by epochs per representations across folds, for the Shrec07 dataset using Diffusion Net.

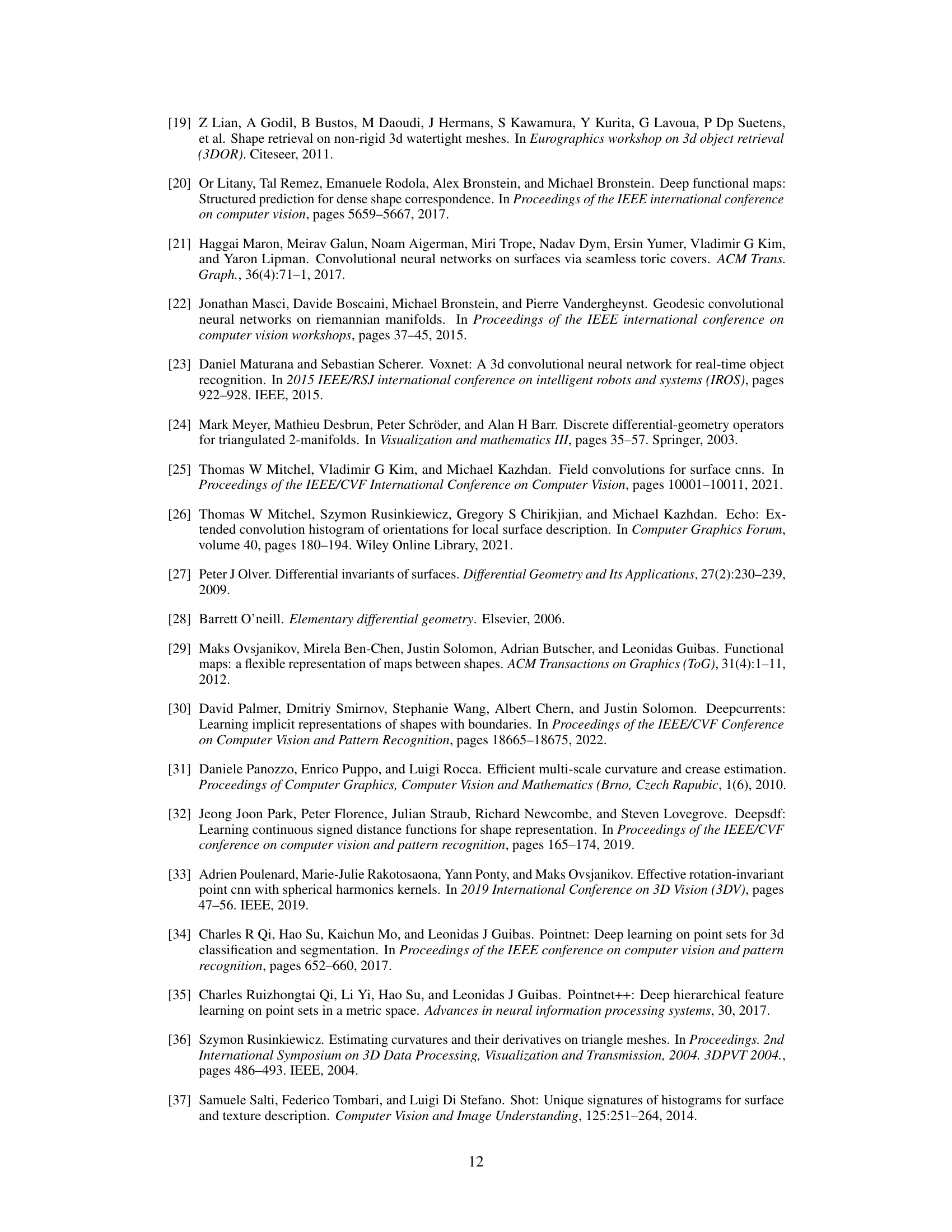

🔼 This figure shows how the test accuracy of three different input representations (principal curvatures (k1,k2), Heat Kernel Signature (HKS), and extrinsic coordinates (xyz)) changes when different levels of Gaussian noise are added to the shapes in the human pose segmentation task. The x-axis represents the percentage of noise added, while the y-axis represents the test accuracy. The shaded areas represent the confidence intervals. The plot shows that, as expected, the extrinsic coordinates are most affected by noise, while the HKS is quite robust. The principal curvatures demonstrate a sensitivity to noise that’s intermediate between HKS and the extrinsic coordinates, showing that they may not be as resilient to noisy data but still maintain a reasonable level of performance.

read the caption

Figure 7: Evolution of the test accuracy on the human pose segmentation task for inputs (k1,k2), HKS and the extrinsic coordinates when noise is added to the shapes.

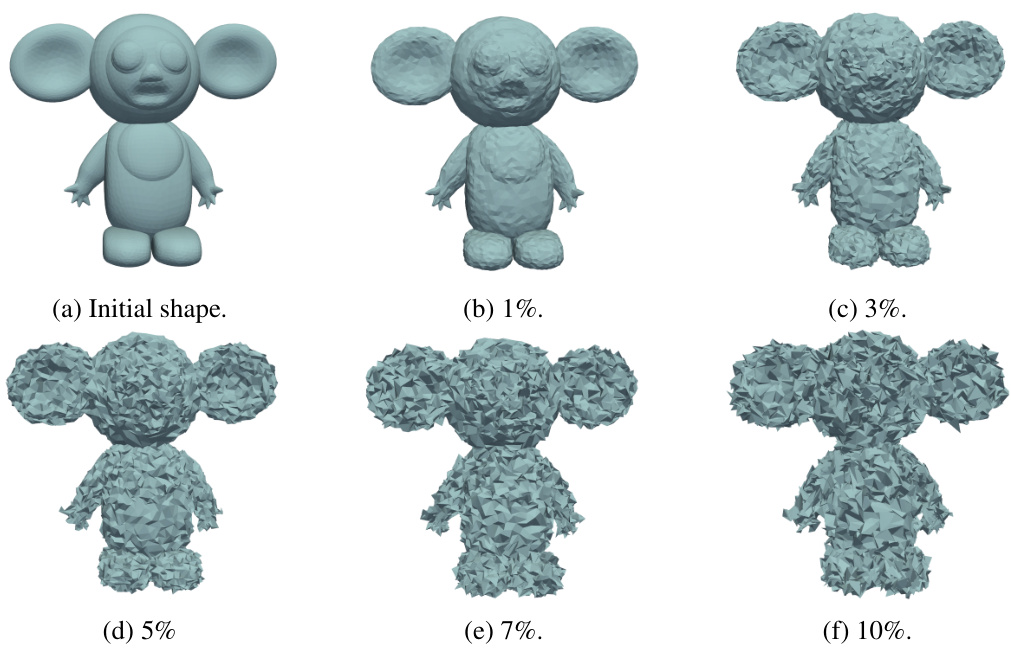

🔼 This figure shows five examples of a human pose mesh from the dataset used in the paper, with increasing levels of added Gaussian noise. The noise level is expressed as a percentage of the diagonal of the bounding box of the mesh. The noise is added to the vertex coordinates, affecting the overall shape and appearance of the mesh. This figure is used to visualize the effect of noise on the input data and to evaluate the robustness of different surface representations to noise.

read the caption

Figure 8: Different quantity of noise added to a shape from the human pose dataset, from 1% to 10% of the diagonal of the bounding box of the shape.

🔼 This figure shows six models of a human-shaped model with different levels of added noise. The first image (a) is the original clean model. The following images (b) through (f) show the same model with different Gaussian noise added. The percentage in the caption refers to the standard deviation of this noise in relation to the length of the longest diagonal of the shape’s bounding box.

read the caption

Figure 8: Different quantity of noise added to a shape from the human pose dataset, from 1% to 10% of the diagonal of the bounding box of the shape.

More on tables

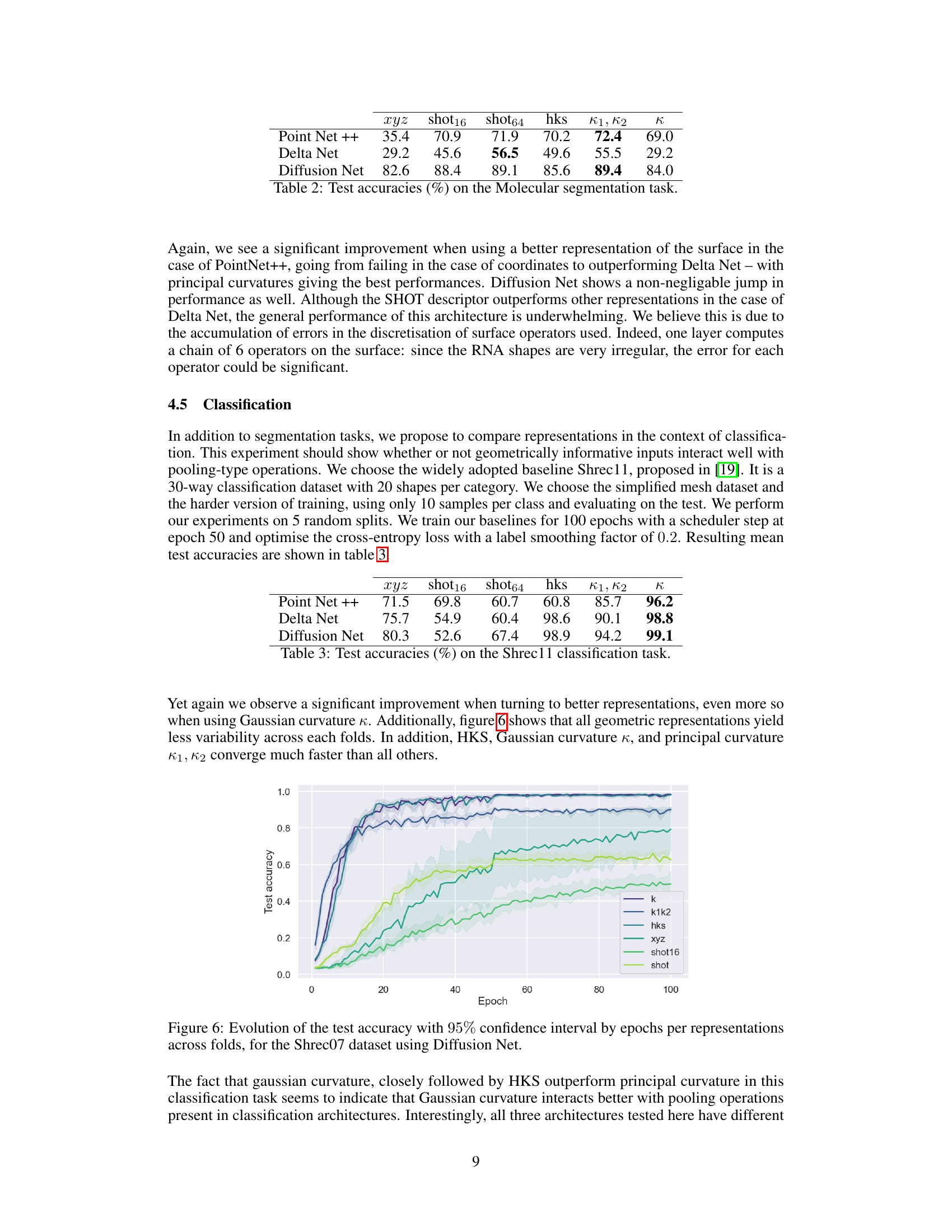

🔼 This table presents the results of molecular segmentation task using six different input representations (xyz, shot16, shot64, hks, k1,k2, k) and three different neural network architectures (PointNet++, DeltaNet, DiffusionNet). The accuracy (%) for each combination of input representation and architecture is shown. This allows for a comparison of the performance of different input representations on a challenging segmentation task.

read the caption

Table 2: Test accuracies (%) on the Molecular segmentation task.

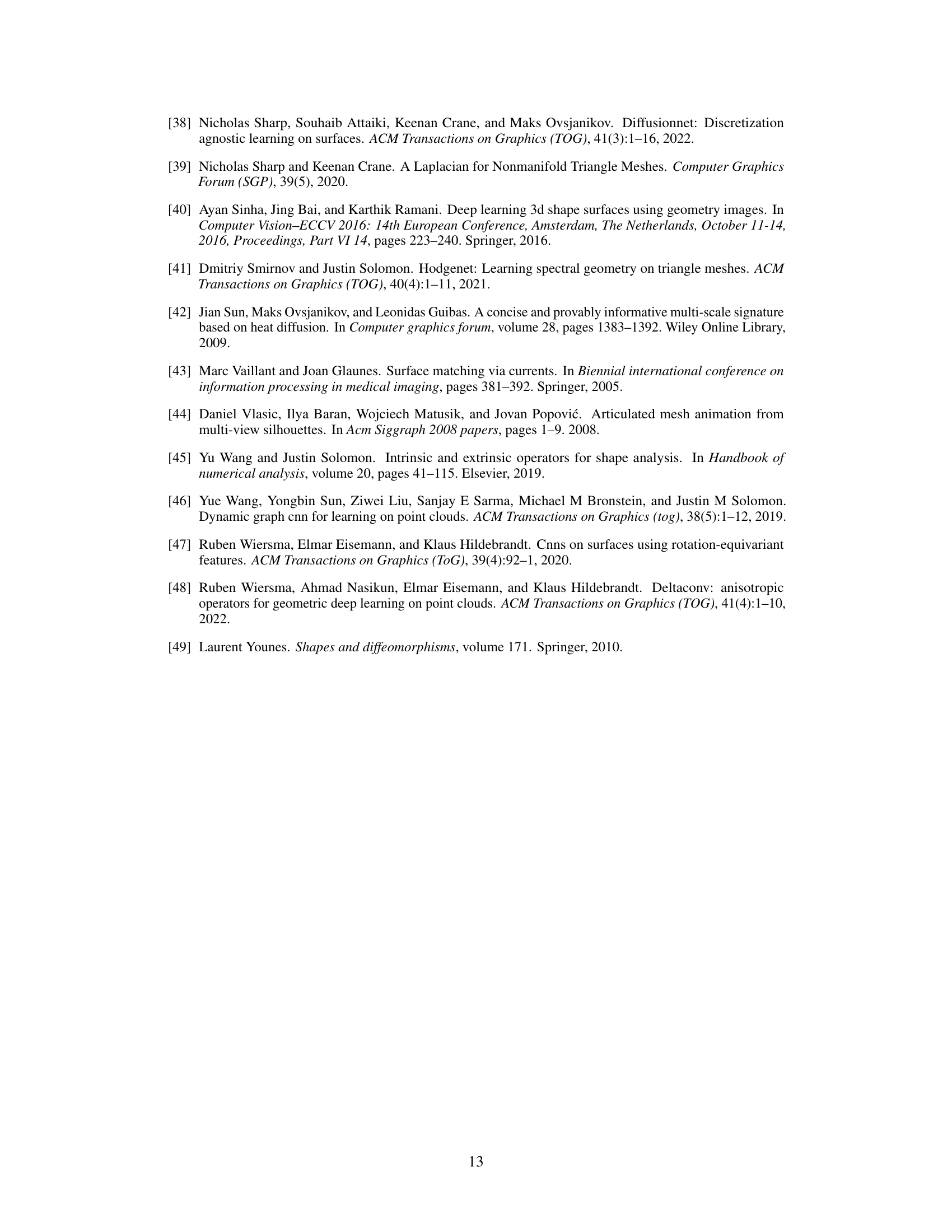

🔼 This table presents the results of a classification task using the Shrec11 dataset. It compares the performance of three different neural network architectures (PointNet++, DeltaNet, and DiffusionNet) across six different input representations of surfaces: xyz coordinates, SHOT descriptors (with 16 and 64 features), Heat Kernel Signatures (HKS), principal curvatures (κ₁, κ₂), and Gaussian curvature (κ). The accuracies are calculated using 5-fold cross validation.

read the caption

Table 3: Test accuracies (%) on the Shrec11 classification task.

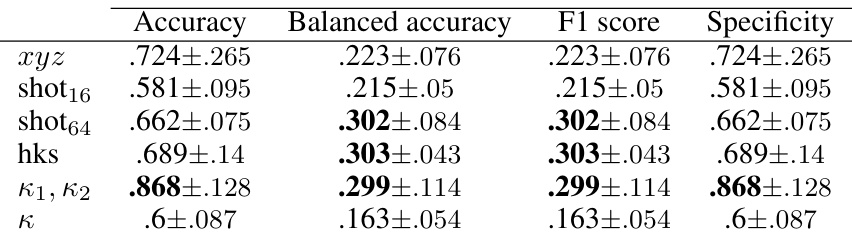

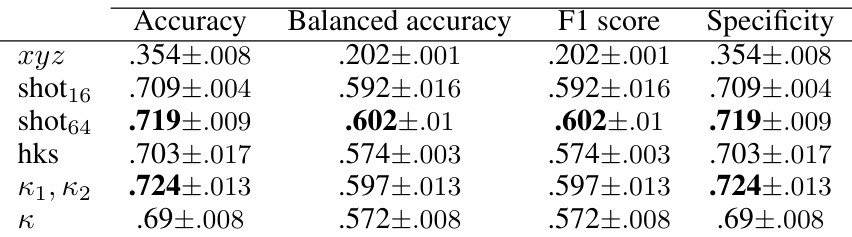

🔼 This table presents the results of human pose segmentation using the PointNet++ neural network architecture. It compares the performance of different surface representations (xyz coordinates, SHOT16, SHOT64, HKS, principal curvatures (κ₁, κ₂), and Gaussian curvature (κ)) in terms of accuracy, balanced accuracy, F1 score, and specificity. The results are based on a 5-fold cross-validation procedure, and the mean and standard deviation are reported for each metric.

read the caption

Table 4: Human pose segmentation - Point Net ++ results.

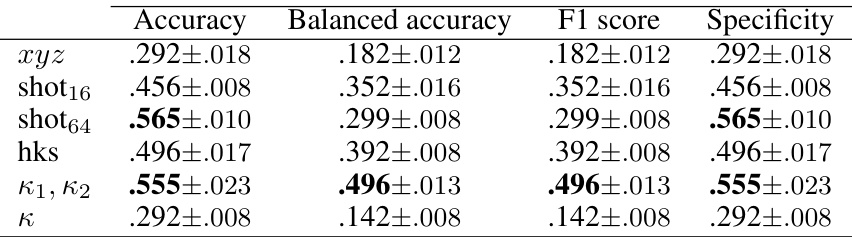

🔼 This table presents the results of human pose segmentation using the Delta Net architecture. It compares the performance of different surface representations (xyz coordinates, SHOT16, SHOT64, HKS, principal curvatures (κ1, κ2), and Gaussian curvature (κ)) in terms of accuracy, balanced accuracy, F1 score, and specificity. The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation across five test sets.

read the caption

Table 5: Human pose segmentation - Delta Net results.

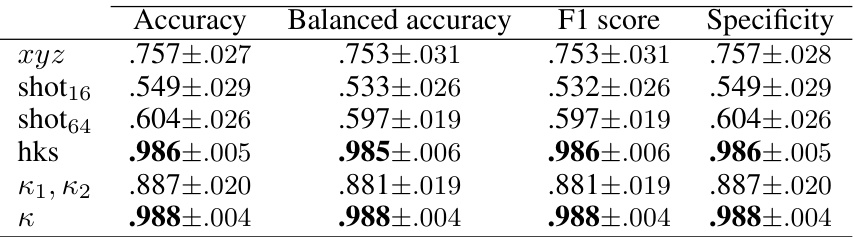

🔼 This table presents the results of human pose segmentation using Diffusion Net. It compares the performance of different surface representations (xyz coordinates, SHOT16, SHOT64, HKS, principal curvatures (κ₁ κ₂), and Gaussian curvature (κ)) in terms of Accuracy, Balanced Accuracy, F1 score, and Specificity. The results are averages from five-fold cross-validation, expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

read the caption

Table 6: Human pose segmentation - Diffusion Net results.

🔼 This table presents the results of the RNA molecules segmentation task using the PointNet++ neural network architecture. It compares the performance of different surface representations (xyz coordinates, SHOT16, SHOT64, HKS, principal curvatures (κ₁, κ₂), and Gaussian curvature (κ)) in terms of Accuracy, Balanced Accuracy, F1 score, and Specificity. The metrics were calculated using 5-fold cross-validation on the test set.

read the caption

Table 7: RNA molecules segmentation - PointNet++ results.

🔼 This table presents the results of RNA molecules segmentation using the Delta Net neural network architecture. Different surface representations (xyz coordinates, SHOT16, SHOT64, HKS, principal curvatures (κ₁, κ₂), and Gaussian curvature (κ)) were tested. The table shows the mean ± standard deviation for Accuracy, Balanced accuracy, F1 score, and Specificity, all calculated using 5-fold cross-validation on test sets.

read the caption

Table 8: RNA molecules segmentation - Delta Net results.

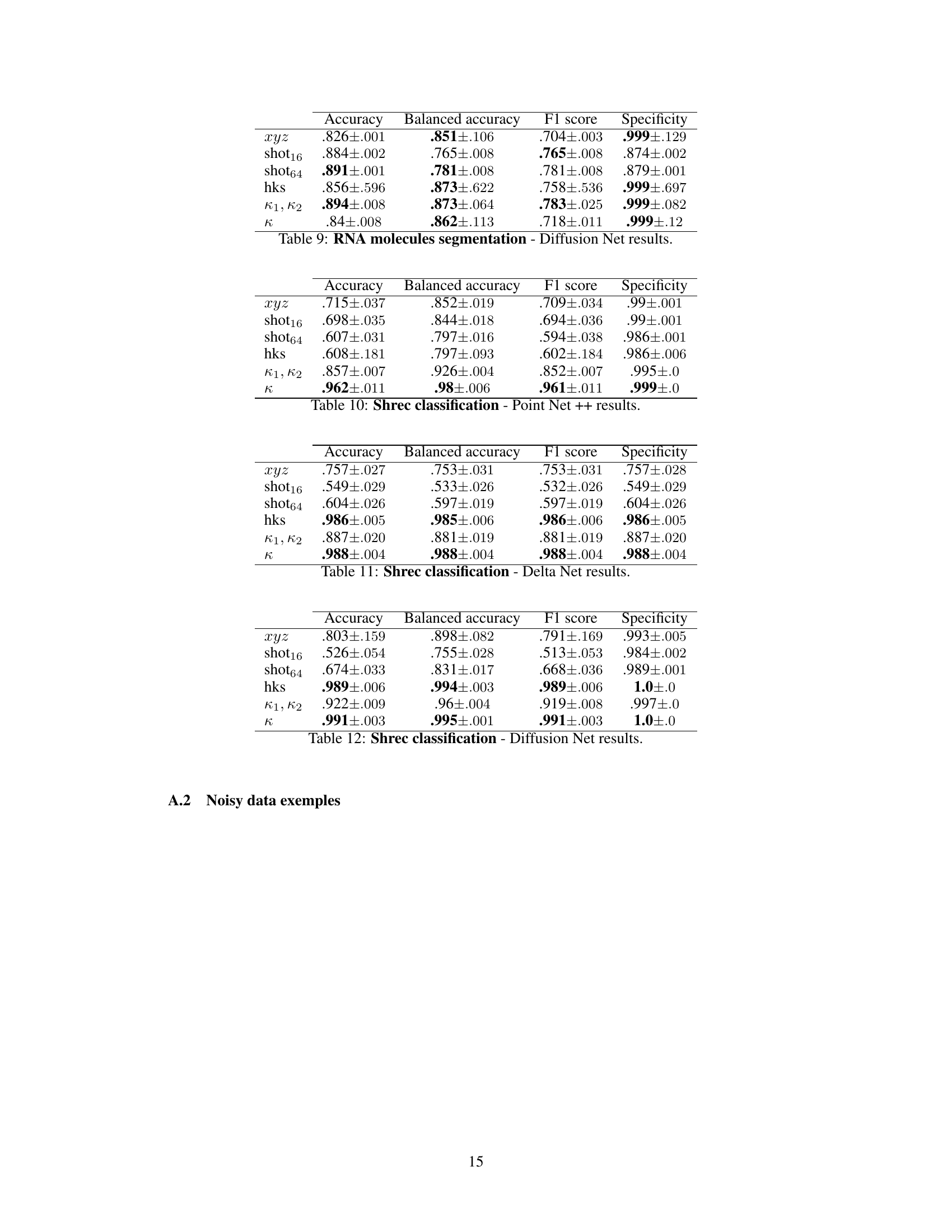

🔼 This table presents the detailed results of the RNA molecules segmentation task using the Diffusion Net architecture. It shows the performance metrics (Accuracy, Balanced Accuracy, F1 score, Specificity) for each of the six different input representations (xyz, shot16, shot64, hks, k1, k2, k) using 5-fold cross-validation. The values presented are the mean ± standard deviation across the five folds.

read the caption

Table 9: RNA molecules segmentation - Diffusion Net results.

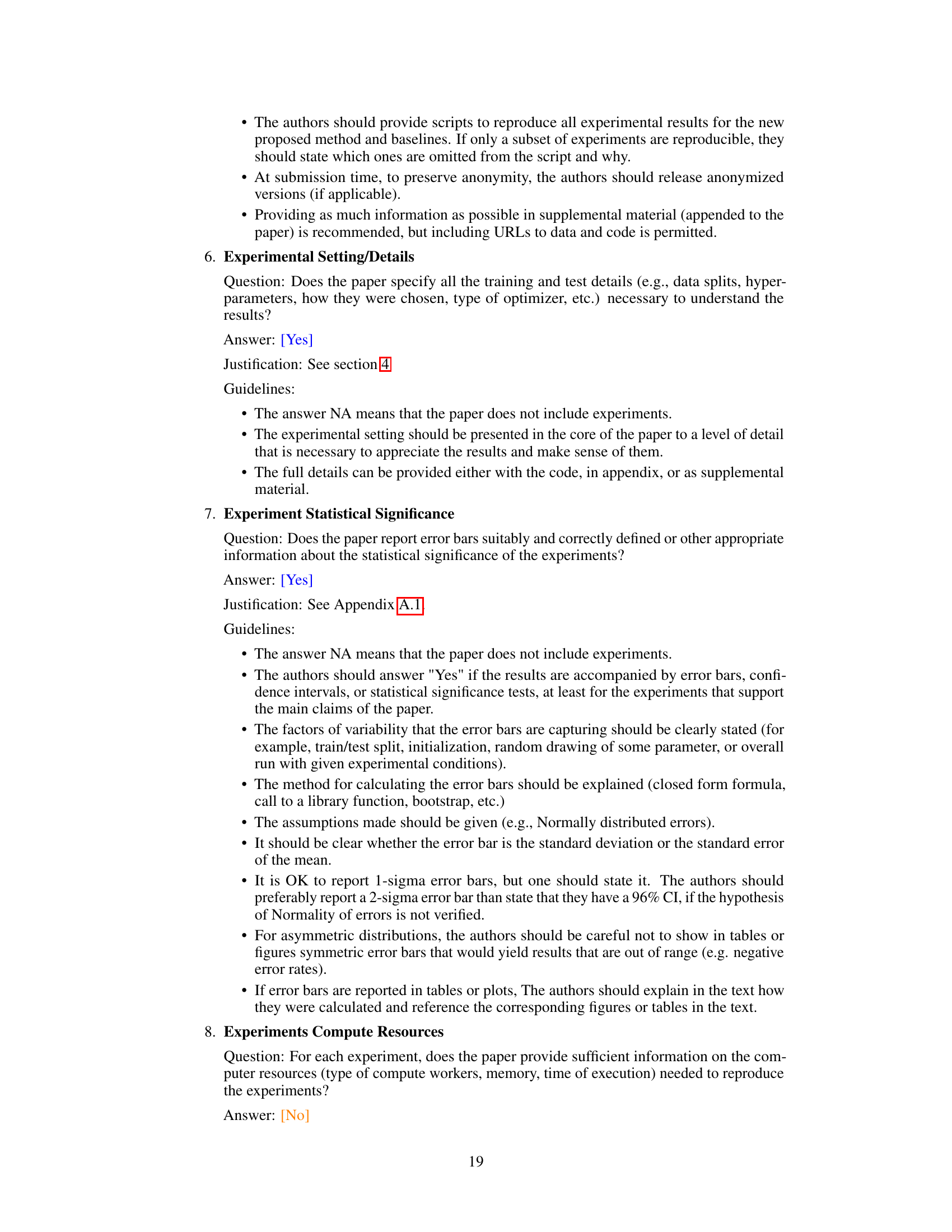

🔼 This table presents the results of the Shrec11 classification task using the Delta Net architecture. It compares the performance of different surface representations (xyz coordinates, SHOT16, SHOT64, HKS, principal curvatures (κ₁, κ₂), and Gaussian curvature (κ)) in terms of Accuracy, Balanced Accuracy, F1 score, and Specificity. The results are based on 5 random splits, with a train-test ratio of 80-20, and the models are trained for 100 epochs with a scheduler step at epoch 50. The metrics presented are the mean values over these 5 runs. This allows us to compare the efficacy of different input representations for surface classification with the chosen neural network architecture.

read the caption

Table 11: Shrec classification - Delta Net results.

🔼 This table presents the results of the Shrec11 classification task using the Delta Net architecture. It compares the performance of different surface representations (xyz coordinates, SHOT16, SHOT64, HKS, principal curvatures (κ₁, κ₂), and Gaussian curvature (κ)) in terms of Accuracy, Balanced Accuracy, F1 score, and Specificity. The results are averages across 5 random splits, showcasing the impact of the chosen surface representation on the model’s classification accuracy.

read the caption

Table 11: Shrec classification - Delta Net results.

🔼 This table presents the results of the Shrec11 classification task using the Delta Net architecture. It compares the performance of different surface representations (xyz coordinates, SHOT16, SHOT64, HKS, principal curvatures (k1, k2), and Gaussian curvature (k)) in terms of accuracy, balanced accuracy, F1 score, and specificity. The results are averages across 5 random train-test splits.

read the caption

Table 11: Shrec classification - Delta Net results.

Full paper#