TL;DR#

Integer programming (IP) is crucial in various fields but solving large-scale IPs remains challenging. Branch-and-cut algorithms are the method of choice; however, selecting effective cutting planes to reduce search space is critical and often heuristic. Recent advances have used data-driven approaches to select good cutting planes from parameterized families. This paper extends this data-driven approach to the selection of the best cut generating function (CGF). CGFs are tools for generating a variety of cutting planes, generalizing well-known Gomory Mixed-Integer (GMI) cutting planes.

The paper provides rigorous sample complexity bounds for the selection of effective CGFs from parameterized families, showing these selected CGFs perform better than GMI cuts in specific distributions. The research also explores the sample complexity of using neural networks for instance-dependent CGF selection, furthering the investigation into instance-specific parameter choices within data-driven algorithm design for branch-and-cut.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it provides rigorous sample complexity bounds for selecting effective cut generating functions in integer programming. It also demonstrates the potential of using machine learning to improve the performance of branch-and-cut algorithms, opening new avenues for research in data-driven algorithm design and optimization. The results have practical implications for solving large-scale integer programming problems.

Visual Insights#

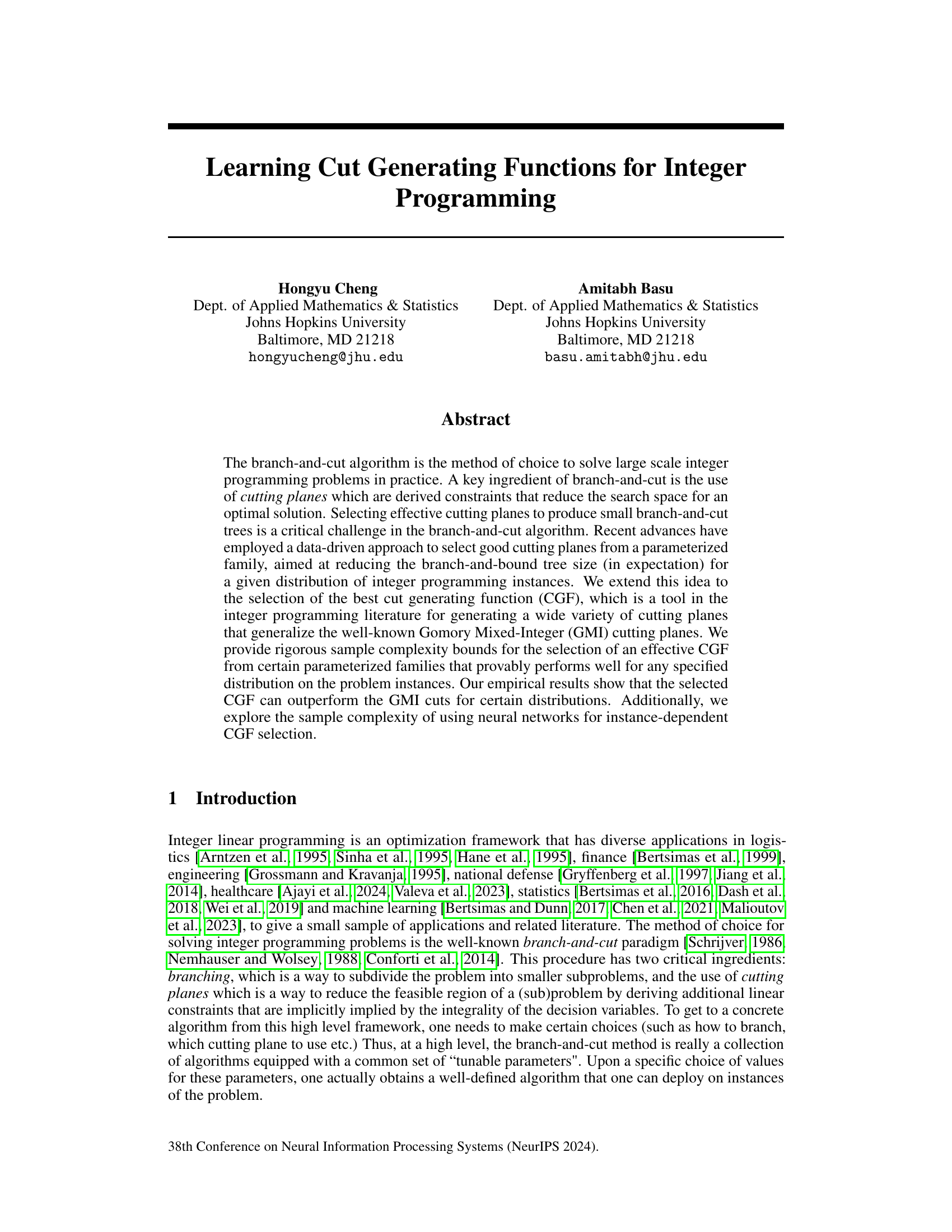

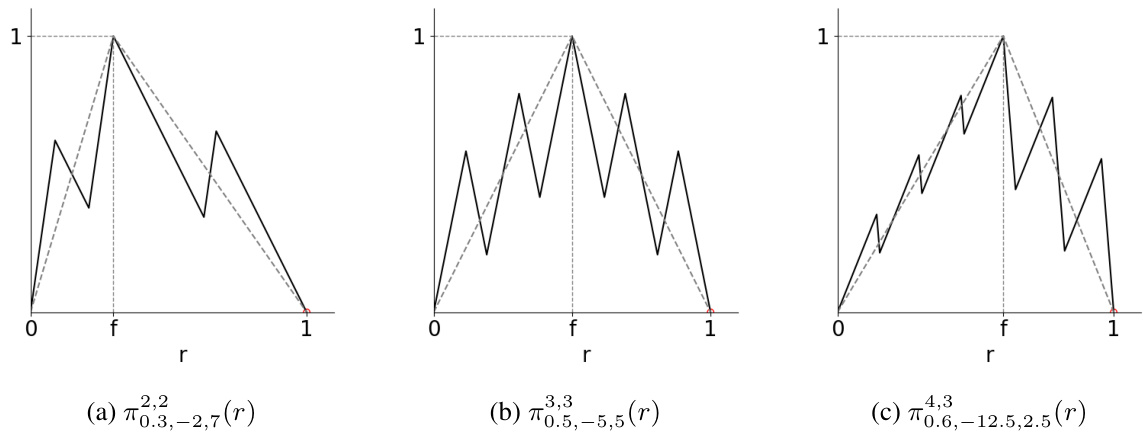

🔼 This figure shows three examples of one-dimensional cut generating functions defined on the interval [0,1). Panel (a) depicts the Gomory fractional cut function (CGf), which is a simple piecewise linear function. Panel (b) illustrates the Gomory mixed-integer cut function (GMIf), another piecewise linear function but with a different structure than the CGf. Panel (c) displays a more complex piecewise linear function (πραf,s1,s2) that generalizes the previous two, demonstrating its greater flexibility in generating cuts for integer programming problems. The parameter f is a fixed real value in (0,1), and s1, s2 are additional parameters that allow for a wider range of cut generation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Three cut generating functions on [0, 1), where πραf,s1,s2 is defined in Section 3.

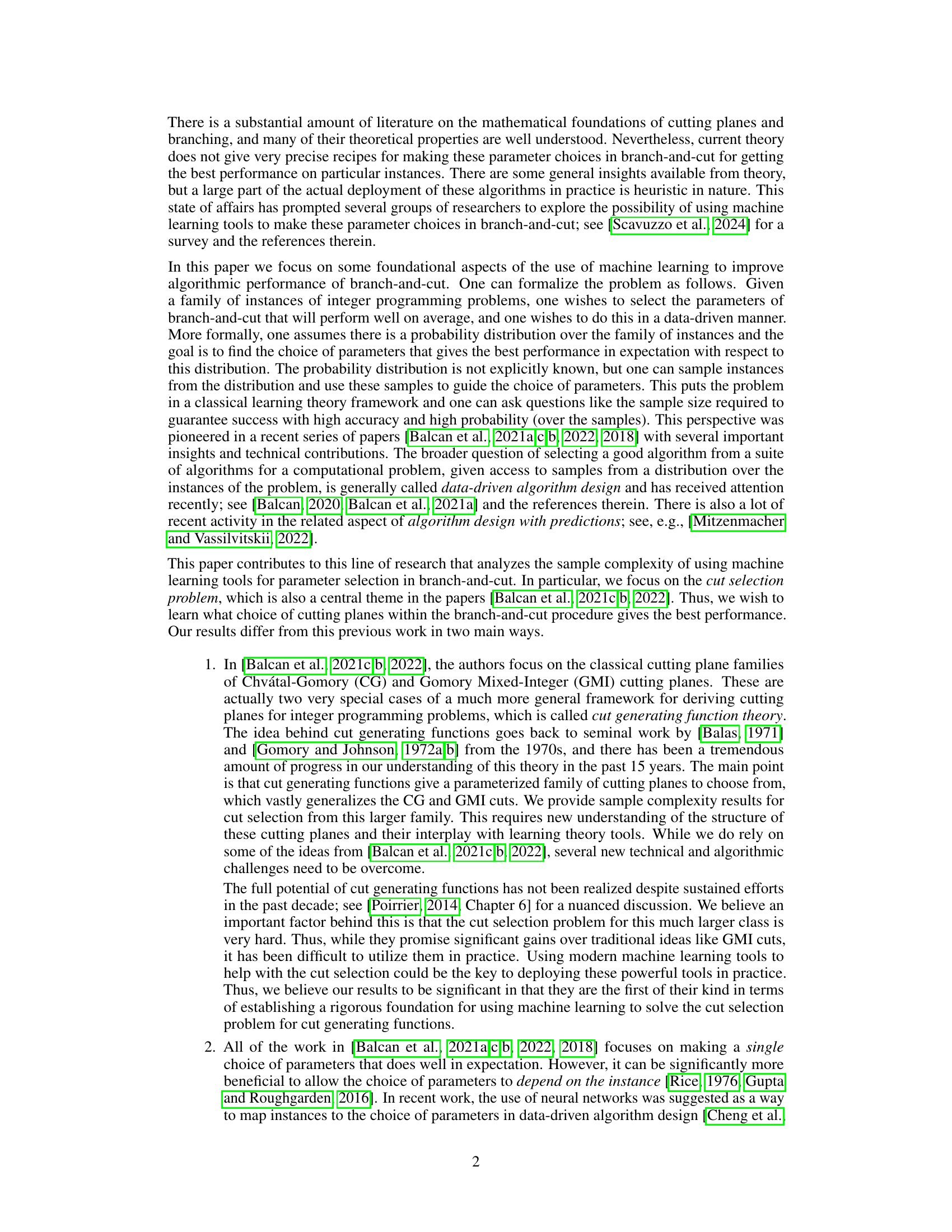

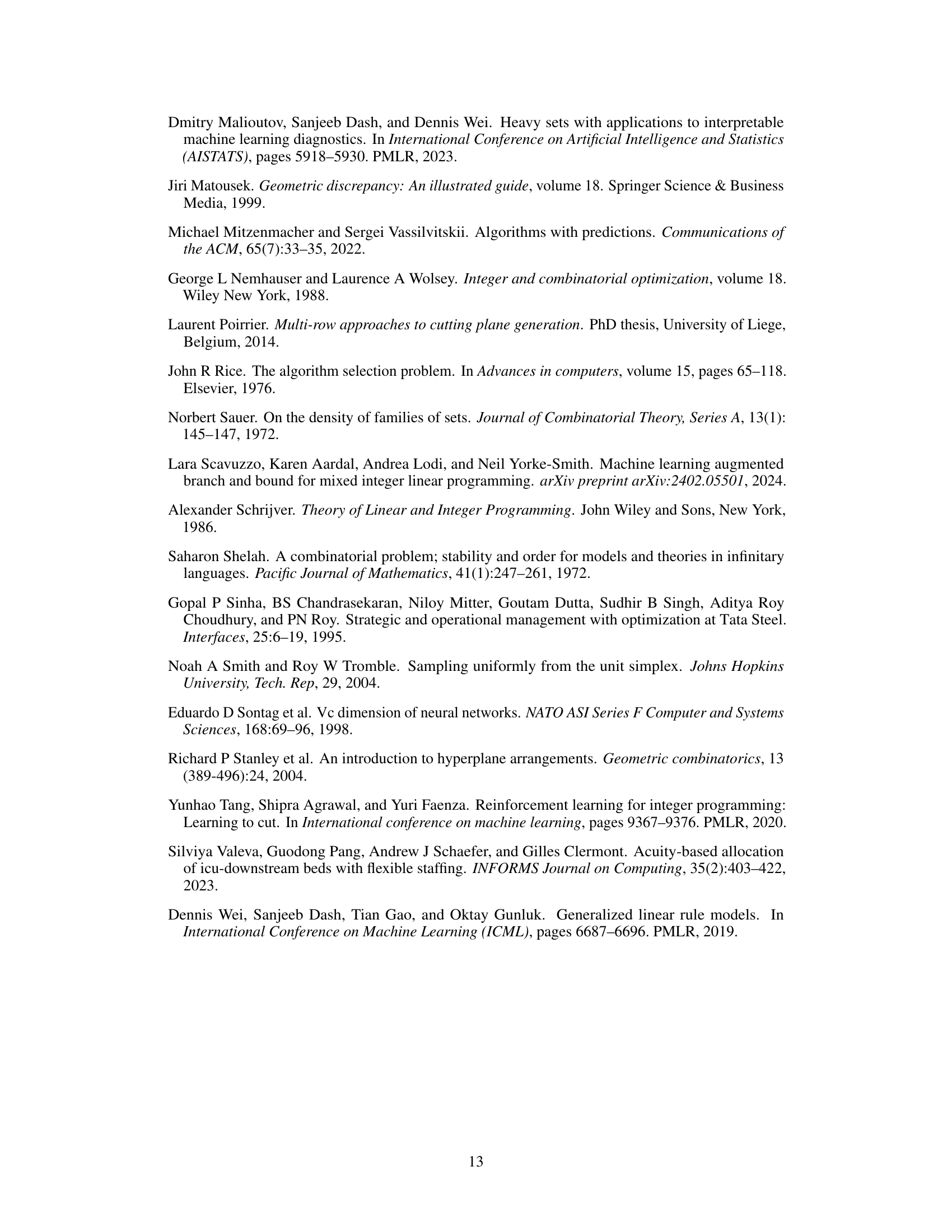

🔼 This table presents the average sizes of branch-and-cut trees for 100 instances of knapsack and packing problems. The tree sizes are shown for different cutting plane strategies: Gomory’s mixed integer cut (GMI), a 1-row cut using a one-dimensional cut generating function, k-row cuts (k=2, 5, 10) using k-dimensional cut generating functions, and the best 1-row cut (representing the optimal performance achievable using this approach). The results compare the effectiveness of the proposed cut generating functions against the traditional GMI cut in reducing the branch-and-cut tree size, which directly correlates to the solution time.

read the caption

Table 1: Average tree sizes on 100 instances, after adding a single type of cut at the root.

In-depth insights#

Cut Selection Learning#

Cut selection learning tackles the challenge of automatically choosing effective cutting planes within branch-and-cut algorithms for integer programming. Instead of relying on heuristics or manually selecting cuts, this approach leverages machine learning to learn patterns from data and predict which cuts will yield the best performance. This is crucial because the choice of cutting planes significantly impacts the efficiency of branch-and-cut, directly affecting the size of the search tree and overall computation time. The core idea is to learn a mapping from problem instance features to optimal cut parameters or even to learn an entirely new family of cuts. This involves gathering data from numerous integer programming instances, extracting relevant features, training a machine learning model, and then using the model to select cuts for new problems. While promising, cut selection learning faces several challenges, such as high computational costs of evaluating different cut options, the need for large datasets to train models effectively, and the potential for overfitting to the training data. Success hinges on careful feature engineering and selecting appropriate machine learning methods, making the choice of model architecture and hyperparameters significant. The effectiveness of this approach compared to existing heuristic techniques represents an open area of research with potential for substantial improvements in solving large-scale integer programming problems.

CGF Sample Complexity#

Analyzing the sample complexity of learning cut generating functions (CGFs) is crucial for the effectiveness of data-driven approaches in integer programming. The core challenge lies in determining how many problem instances need to be sampled to guarantee that a learned CGF generalizes well to unseen instances. The paper likely explores theoretical bounds on the sample complexity, potentially using techniques from statistical learning theory such as VC-dimension or Rademacher complexity. Factors influencing sample complexity could include the richness of the CGF family being considered (its capacity), the desired accuracy and confidence level, and the underlying distribution of problem instances. An in-depth analysis would likely provide valuable insights into the practical feasibility of using machine learning to select CGFs, highlighting trade-offs between computational cost and the accuracy of the learned model. The results may offer guidance on choosing appropriate CGF families and setting sample sizes for reliable performance. Finally, establishing a connection between theoretical sample complexity bounds and the empirical performance observed during experiments is vital for validating the theoretical findings and demonstrating the practicality of the proposed approach.

Neural CGF Selection#

The concept of “Neural CGF Selection” presents a powerful paradigm shift in integer programming. Instead of relying on pre-defined cut generating functions (CGFs), a neural network learns to dynamically select the optimal CGF based on the specific characteristics of each problem instance. This approach leverages the strengths of both data-driven methods and the theoretical foundation of CGFs. The neural network acts as a sophisticated mapping from problem features to the parameter space of CGFs, effectively tailoring the cutting plane generation process for improved efficiency and solution quality. This addresses a key challenge in integer programming, where the optimal choice of CGF often remains elusive. The feasibility and effectiveness of this method will hinge on the design and training of the neural network, including appropriate feature engineering and the choice of network architecture. Sample complexity analysis will be crucial to assess how much data is needed for reliable generalization, and empirical validation on various problem instances is essential to demonstrate performance gains compared to traditional approaches. The potential benefits are significant, as instance-dependent CGF selection could drastically reduce the size of the branch-and-bound tree, leading to faster computation times and solving previously intractable problems.

Instance-Dependent Cuts#

The concept of instance-dependent cuts in integer programming offers a significant advancement over traditional approaches. Instead of selecting a single cut generation function (CGF) that performs well on average across a distribution of problem instances, instance-dependent cuts dynamically choose a CGF tailored to the specific characteristics of each individual problem. This approach acknowledges the inherent variability within integer programming problems, recognizing that what works well for one problem may not be optimal for another. The key advantage lies in the potential for substantial performance improvements. By leveraging machine learning techniques, particularly neural networks, to learn mappings from problem instances to optimal CGFs, the approach can adapt to unseen data and achieve superior results compared to instance-independent methods. This dynamic cut selection has the potential to transform integer programming’s effectiveness for various applications. However, this approach necessitates the investigation of sample complexity to guarantee that the learned mapping generalizes effectively to new instances, and further research into efficient neural network architectures is essential for practical applicability.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical framework to encompass a broader range of cut generating functions is crucial, moving beyond the specific families analyzed in this paper. This would involve investigating the sample complexity bounds for more complex function families and exploring their practical performance. Developing more sophisticated neural network architectures for instance-dependent cut selection is another key area. Current approaches are relatively simple; exploring more powerful neural networks could lead to significant improvements in cut selection accuracy. Furthermore, research should focus on integrating these techniques into a complete branch-and-cut solver, evaluating their overall impact on solution time and tree size for various problem instances. Finally, empirical studies on larger and more diverse datasets are needed to robustly validate the effectiveness of the proposed approaches and compare them against state-of-the-art methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows three examples of one-dimensional cut generating functions on the interval [0,1). These functions, denoted πραf,81,82(r), are parameterized by f (a value between 0 and 1), p and q (integers greater than or equal to 2), and s1 and s2 (real numbers). Each plot illustrates the shape of the function for a specific choice of these parameters. The functions are used to derive cutting planes in integer programming, and their various forms illustrate the range of possible cutting planes that can be generated.

read the caption

Figure 1: Three cut generating functions on [0, 1), where πραf,81,82 is defined in Section 3.

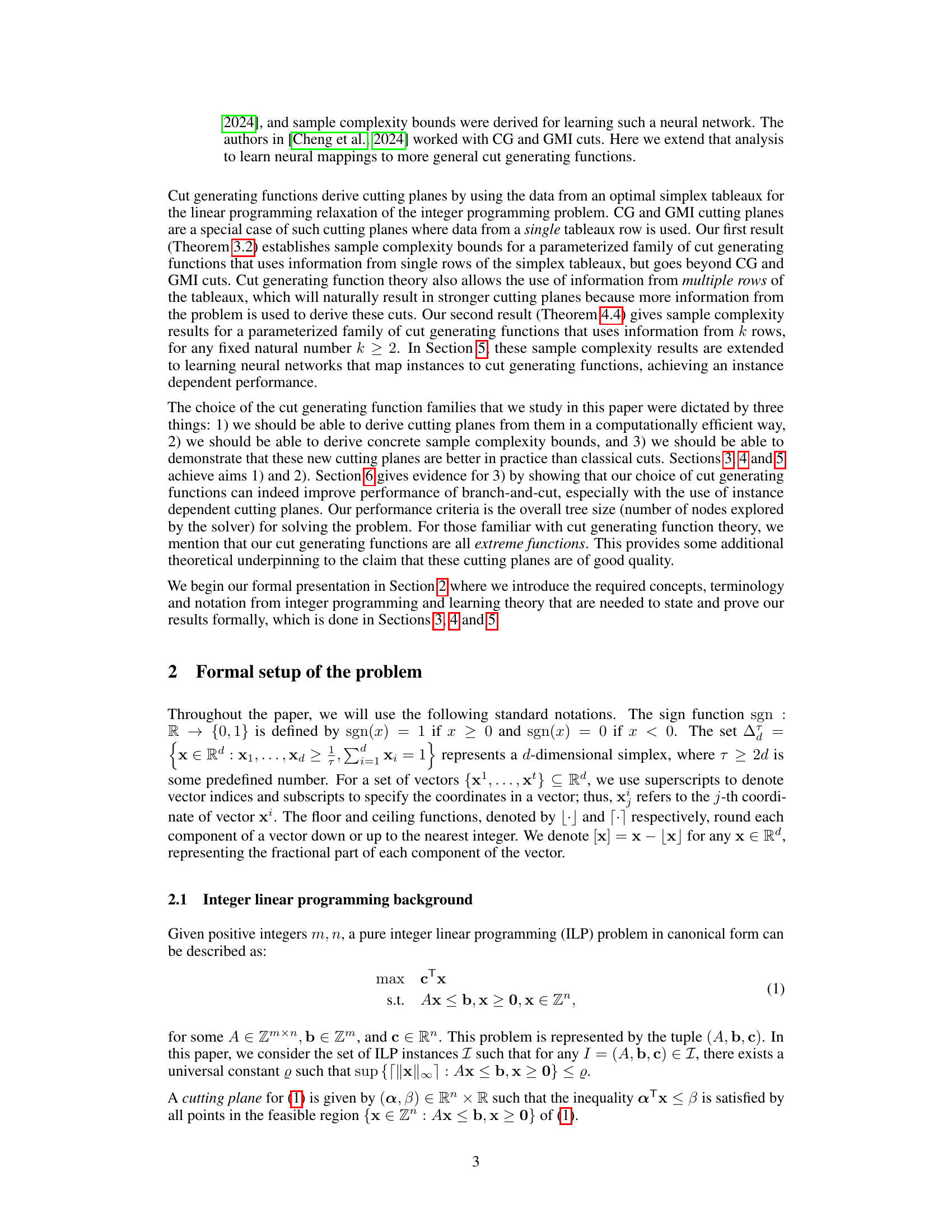

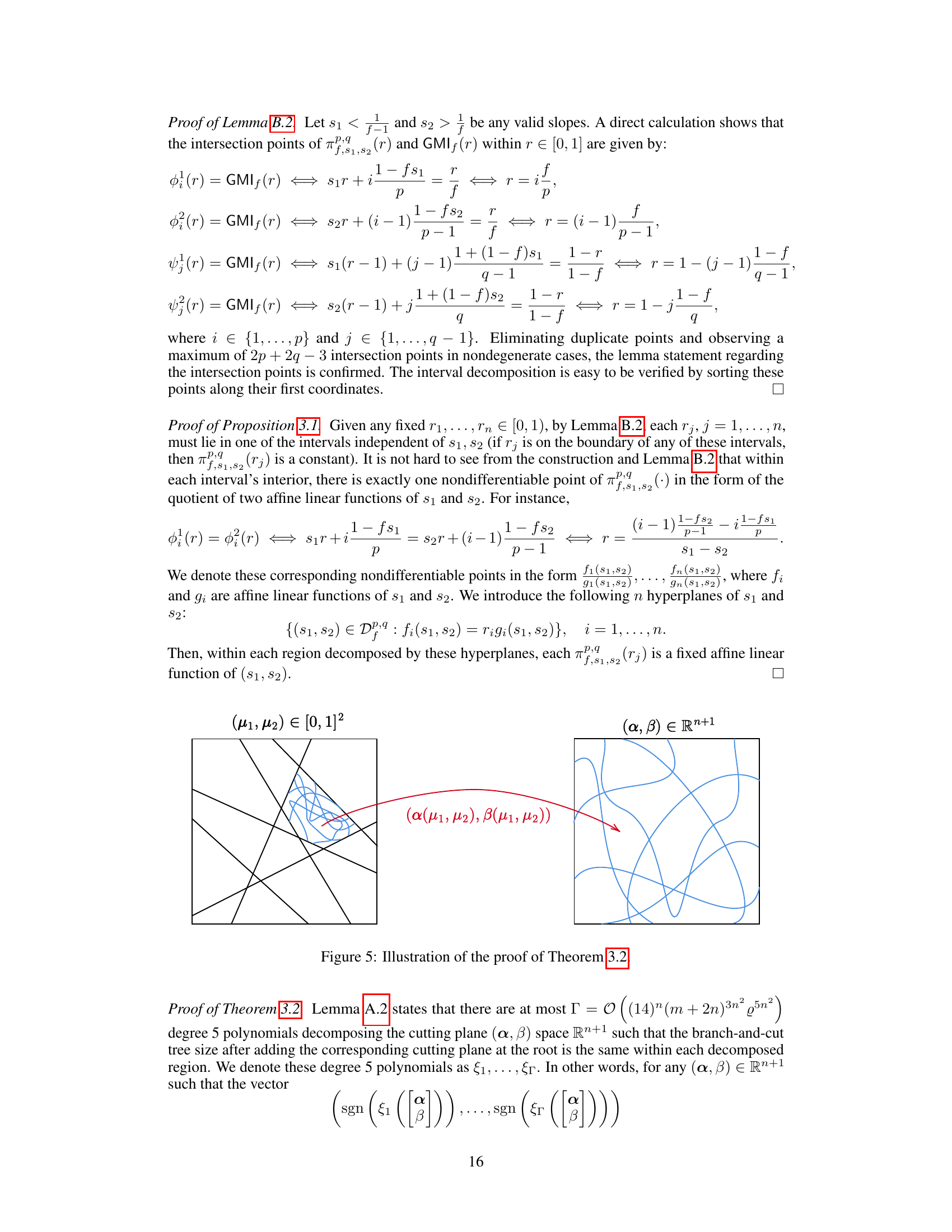

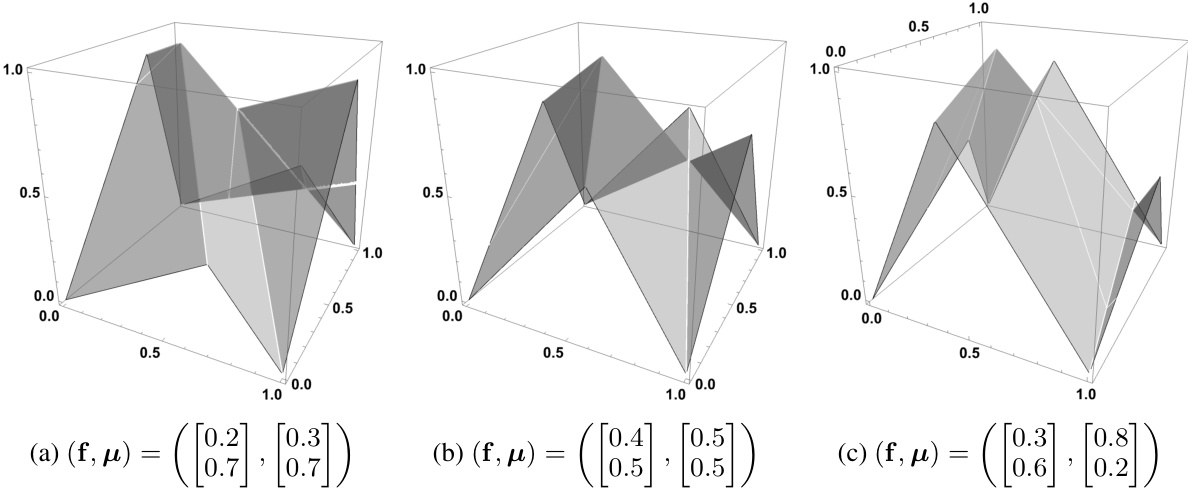

🔼 This figure shows three examples of 2-dimensional cut generating functions. Each plot visualizes the function’s output (z-axis) against two input variables (x-axis and y-axis), which represent parameters of the function. The shape of the surface in each plot shows the complex behavior of these functions, which are used to generate cutting planes in integer programming.

read the caption

Figure 3: Three examples of the 2-dimensional cut generating functions πf,μ on [0, 1)2.

🔼 This figure shows three examples of one-dimensional cut generating functions on the interval [0, 1). These functions, denoted as πραf,s1,s2(r), are used to derive cutting planes in integer programming. The figure visually represents the shape of these functions, highlighting their piecewise linear nature and demonstrating variations based on different parameter choices.

read the caption

Figure 1: Three cut generating functions on [0, 1), where πρα f,s1,s2 is defined in Section 3.

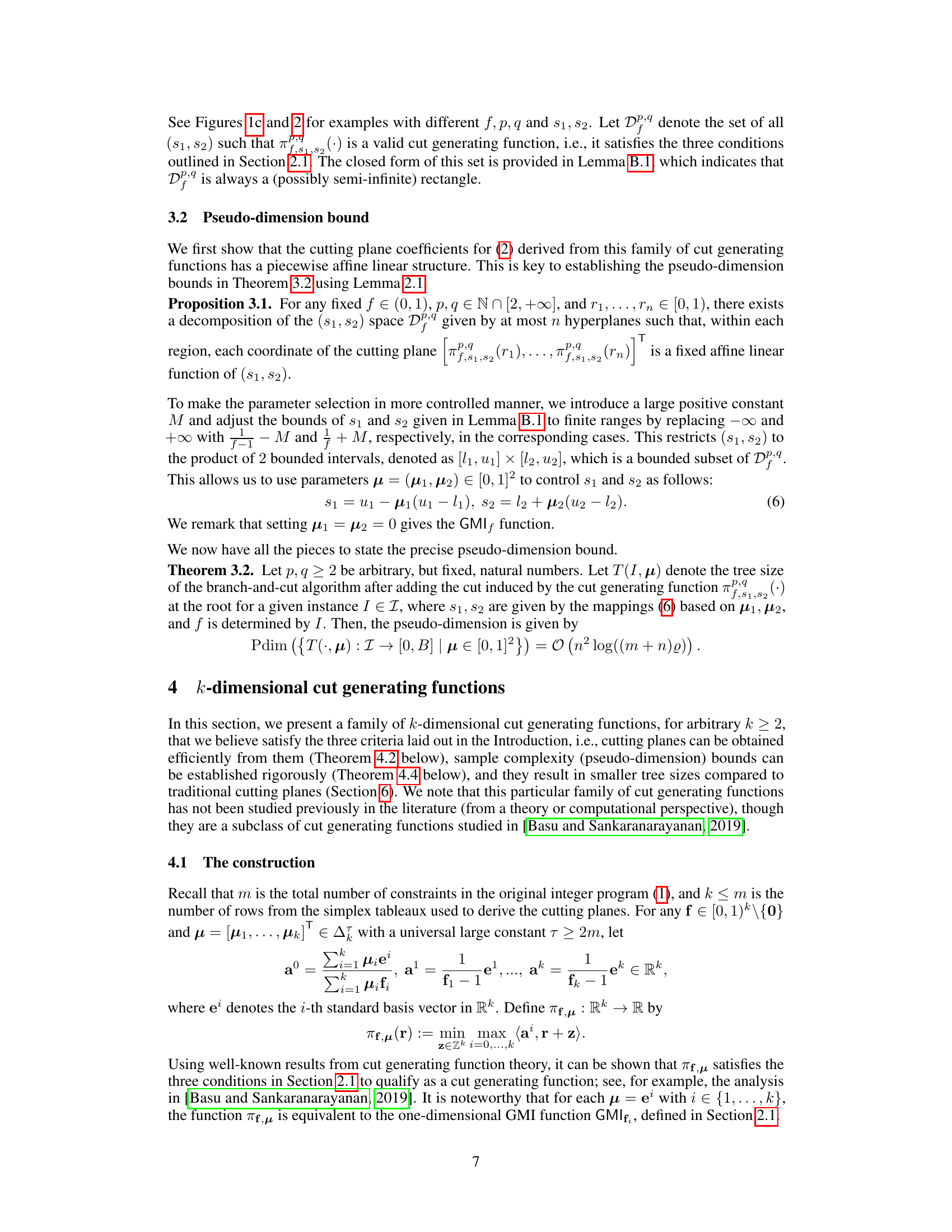

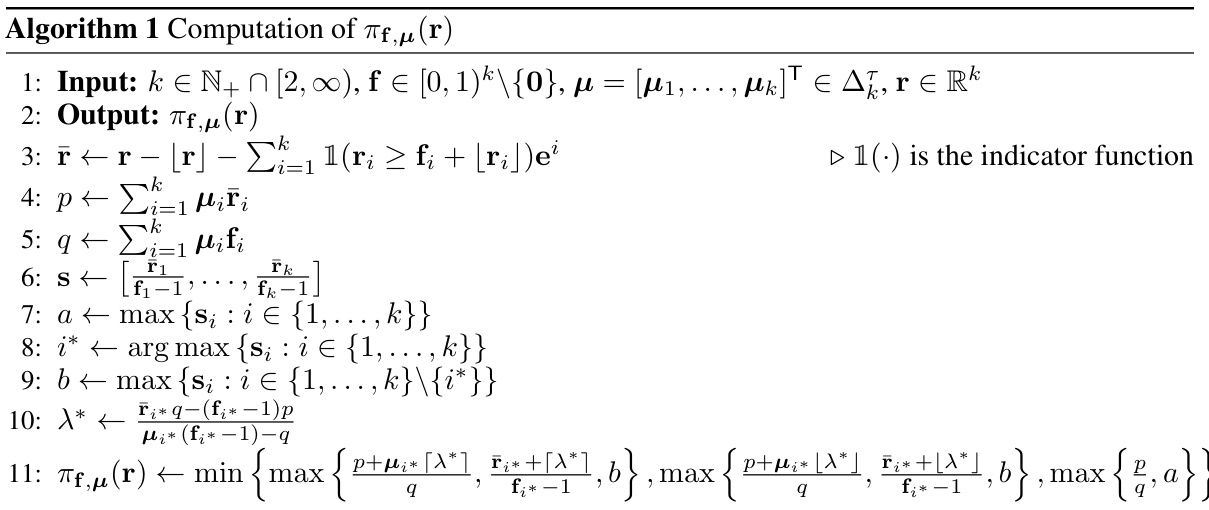

🔼 This figure illustrates the proof of Theorem 3.2 in the paper. The left panel shows a decomposition of the parameter space [0,1]² by hyperplanes. The right panel shows a mapping from the parameter space to the cutting plane space Rn+1. The curved lines in the right panel represent the regions in the parameter space that map to the same cutting plane.

read the caption

Figure 5: Illustration of the proof of Theorem 3.2.

Full paper#