TL;DR#

Self-attention, while powerful, suffers from high computational costs, especially in handling high-dimensional data like images and videos. Neighborhood attention offers a solution by limiting each token’s attention to its nearest neighbors, thereby reducing the quadratic complexity. However, existing neighborhood attention implementations have been hampered by limitations in infrastructure and performance, particularly in higher-rank spaces (2-D and 3-D). This has made it challenging to fully leverage its potential benefits.

This paper addresses these limitations by presenting two novel methods for implementing neighborhood attention. First, it demonstrates that neighborhood attention can be efficiently represented as a batched GEMM problem, leading to significant performance improvements (895% and 272% for 1-D and 2-D, respectively) compared to naive CUDA implementations. Secondly, by adapting fused dot-product attention kernels, they develop fused neighborhood attention, allowing for fine-grained control over attention across spatial axes. This reduces both the quadratic time and constant memory footprint associated with self-attention. The fused implementation shows dramatic speedups in half-precision (1759% and 958% for 1-D and 2-D, respectively) and improvements in model inference and training.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with attention mechanisms, especially in computer vision. It provides significantly faster and more memory-efficient implementations of neighborhood attention, a crucial technique for handling large inputs while maintaining efficiency. This opens avenues for scaling up vision models and applying attention to higher-dimensional data.

Visual Insights#

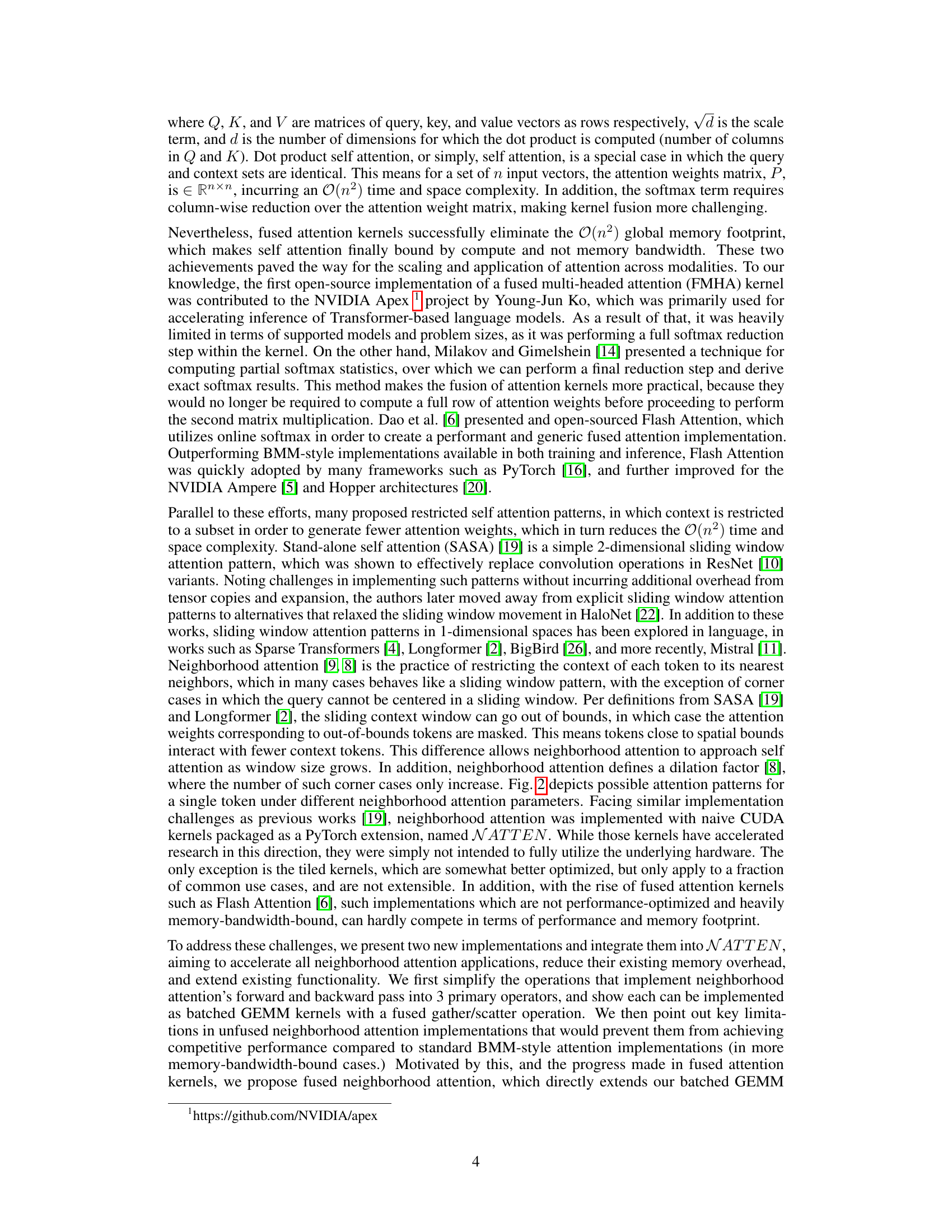

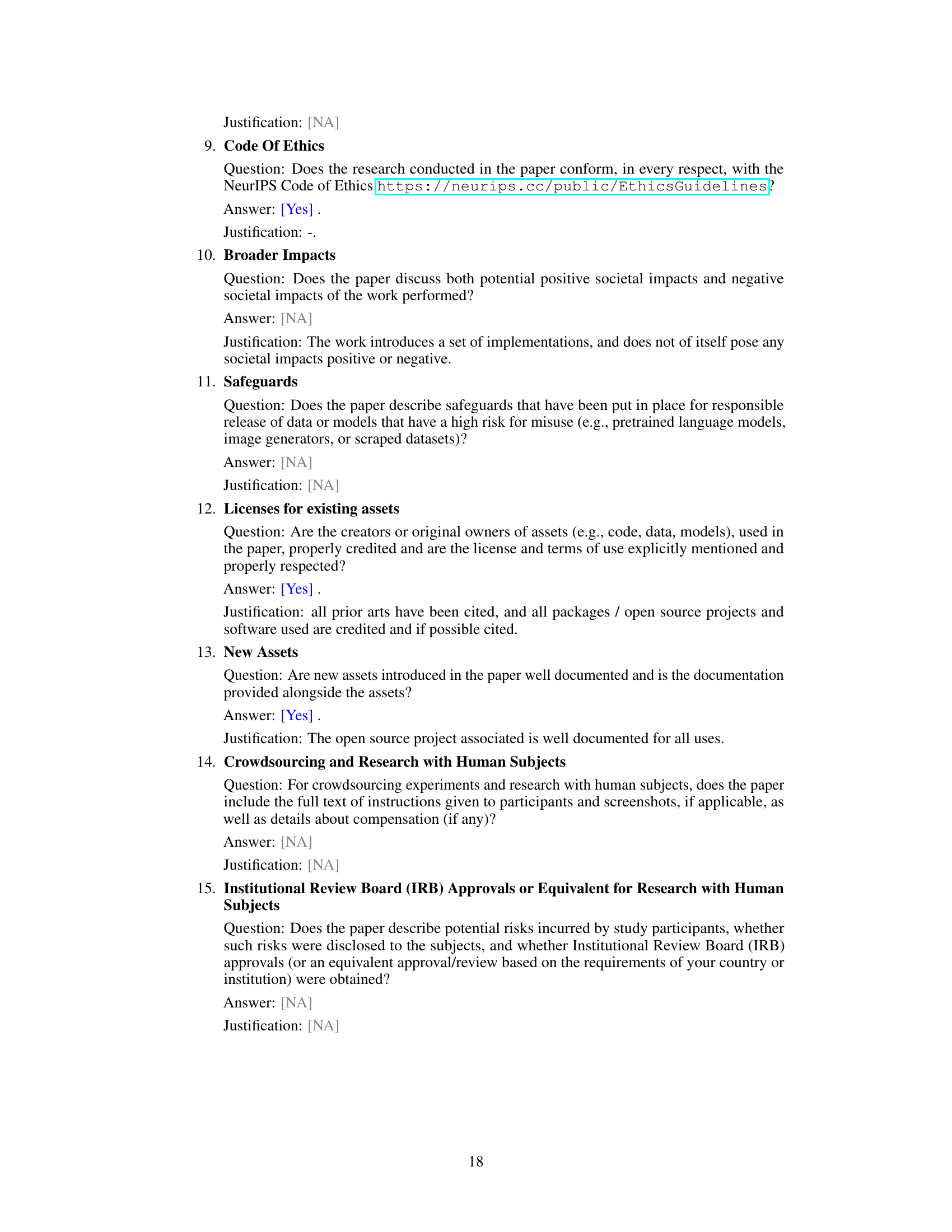

🔼 This figure shows the speedup achieved by the proposed GEMM-based and fused neighborhood attention methods compared to naive CUDA kernels on NVIDIA A100 GPUs. It presents the average speedup for 1D, 2D, and 3D problems, separated into forward pass only and forward plus backward pass scenarios. The results demonstrate significant performance gains for both methods, particularly in fused neighborhood attention.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of average improvement in speed on A100 from our proposed implementation. Baseline is the set of naive CUDA kernels introduced in Neighborhood Attention Transformer [9]. GEMM-based NA improves 1-D problems by an average of 548% (forward pass) and 502% (forward + backward), and 2-D problems by an average of 193% (forward pass) and 92% (forward + backward). GEMM-based NA does not implement 3-D problems yet. Fused NA boosts performance further and improves 1-D problems by an average of 1759% (forward pass) and 844% (forward + backward), and 2-D problems by an average of 958% (forward pass) and 385% (forward + backward), and 3-D problems by an average of 1135% (forward pass) and 447% (forward + backward).

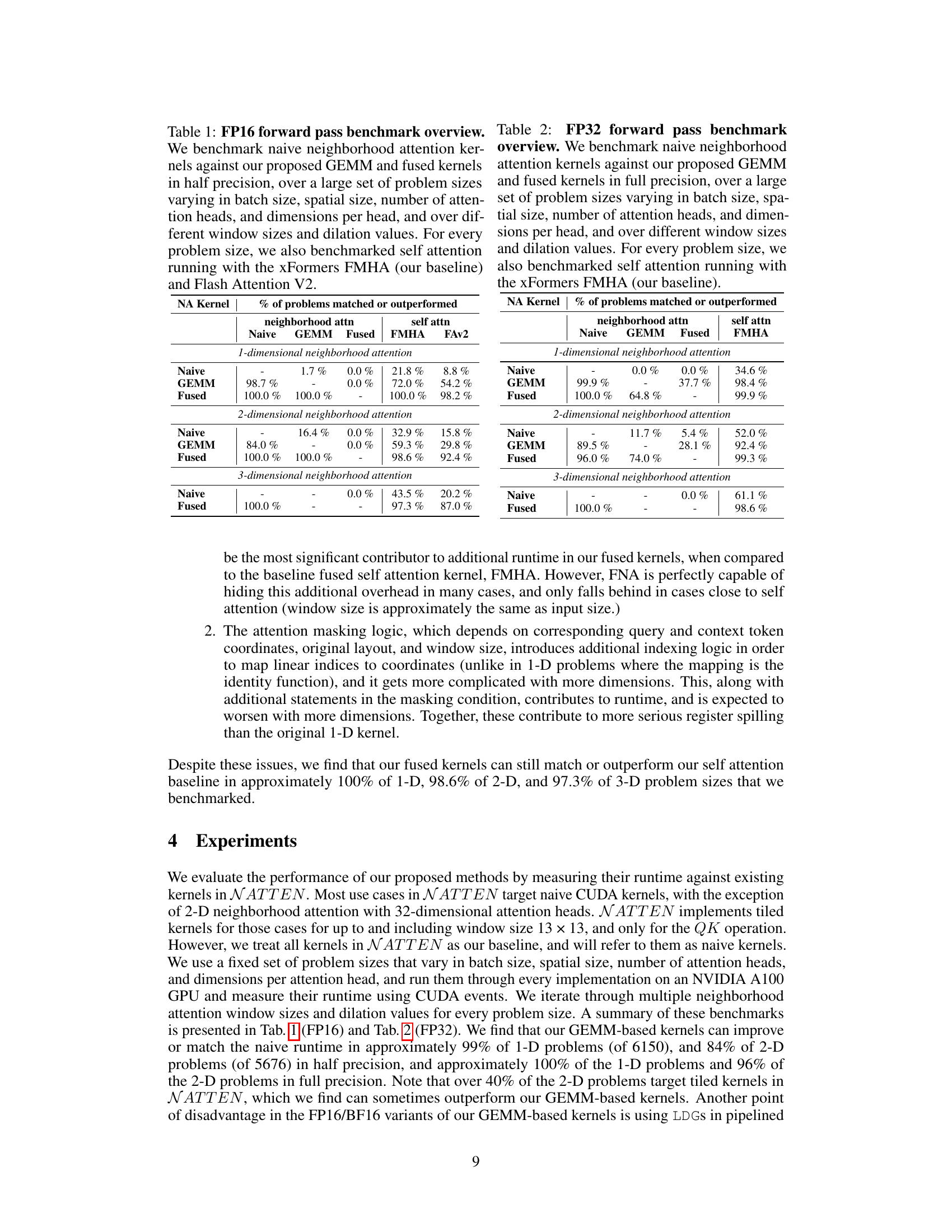

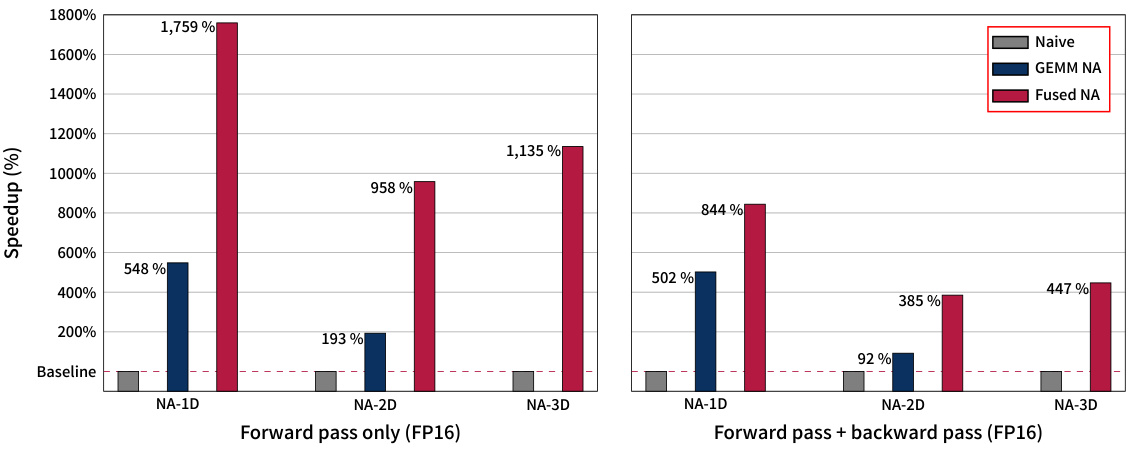

🔼 This table presents the results of a benchmark comparing the performance of naive, GEMM-based, and fused neighborhood attention kernels against standard self-attention methods (FMHA and FlashAttention V2) using FP16 precision. The benchmark considers various problem sizes with different parameters (batch size, spatial size, number of heads, dimensions per head, window size, and dilation). The table shows the percentage of benchmark problems where each neighborhood attention approach matched or outperformed the others.

read the caption

Table 1: FP16 forward pass benchmark overview. We benchmark naive neighborhood attention kernels against our proposed GEMM and fused kernels in half precision, over a large set of problem sizes varying in batch size, spatial size, number of attention heads, and dimensions per head, and over different window sizes and dilation values. For every problem size, we also benchmarked self attention running with the xFormers FMHA (our baseline) and Flash Attention V2.

In-depth insights#

GEMM-based Attention#

GEMM-based attention represents a significant advancement in the efficient computation of attention mechanisms. By framing the attention operation as a general matrix-matrix multiplication (GEMM) problem, it leverages highly optimized and hardware-accelerated GEMM libraries. This approach offers several key advantages. First, it leads to considerable speed improvements compared to naive implementations. Second, it improves memory efficiency by reducing the number of memory transactions. This is particularly crucial for larger models and sequences where memory access becomes a major bottleneck. Third, GEMM-based attention offers better scalability as it readily maps to parallel processing architectures. However, the reliance on GEMM introduces some challenges. One limitation is the need for explicit data reshaping and transformations, potentially affecting performance and adding complexity. The efficiency gain is also contingent on the efficient implementation of the scatter/gather operations required to handle the spatial layout of attention patterns. Despite these considerations, GEMM-based attention provides a compelling and effective approach for enhancing the performance and scalability of attention-based models.

Fused Kernel Boost#

A hypothetical “Fused Kernel Boost” section in a research paper would likely detail improvements achieved by fusing multiple kernel operations. This fusion optimizes performance by reducing memory access, improving data locality, and enabling parallel processing. The core idea is to combine previously separate kernels into a single, unified kernel; this minimizes data transfers between different computational units, leading to significant speedups, especially crucial for computationally intensive tasks such as deep learning. Specific techniques employed might include loop fusion, data reuse strategies, or specialized hardware instructions designed for parallel computations. The results section would demonstrate speedups and efficiency gains over non-fused methods, quantifying the impact of fusion through benchmarks, highlighting the effectiveness of the fused kernel approach. A key aspect would be the discussion of trade-offs: While fusion typically improves performance, it may increase kernel complexity, making debugging and maintenance more challenging. The analysis of these trade-offs is crucial for establishing the overall effectiveness and applicability of the “Fused Kernel Boost” technique.

Neighborhood Scope#

The concept of ‘Neighborhood Scope’ in the context of attention mechanisms is crucial for computational efficiency. It refers to the size and shape of the local context considered when computing attention weights for a given token. A smaller neighborhood implies less computation, but might sacrifice some information capture. Larger neighborhoods, on the other hand, approach the full attention mechanism’s expressiveness, but at a steep computational cost. The tradeoff between accuracy and efficiency is central to the design of efficient attention models. The choice of neighborhood scope directly impacts the model’s ability to capture long-range dependencies, as smaller neighborhoods limit the context each token can attend to. Various techniques like dilation and causal masking allow for flexible control over this scope, leading to a spectrum of attention patterns between local and global attention. Finding the optimal neighborhood scope balances model performance and computational feasibility, making it a critical design parameter in modern deep learning architectures.

Limitations of NA#

Neighborhood Attention (NA) methods, while offering significant speedups over standard self-attention, suffer from inherent limitations. The primary constraint stems from the inherent nature of NA’s localized attention mechanism. While reducing quadratic complexity, this locality restricts the model’s capacity to capture long-range dependencies crucial for many tasks. The efficiency gains from reduced computation are often offset by implementation challenges, particularly in higher-dimensional spaces (2D and 3D), where the inherent complexities of handling irregular data structures and efficient memory access can negate the theoretical advantages. Furthermore, unfused implementations struggle with memory bandwidth bottlenecks, as demonstrated in the paper. Though the proposed GEMM-based and fused implementations aim to mitigate these issues, they themselves introduce trade-offs, particularly regarding the complexity of implementation and the potential for reduced performance in specific scenarios, underscoring the need for continued research in optimizing NA’s performance and scalability.

Future Directions#

The paper’s exploration of neighborhood attention opens exciting avenues. Future work could focus on enhancing the auto-tuning process, enabling broader applicability across diverse hardware and distributed training environments. Addressing the limitations of unfused implementations, particularly the scatter/gather operations, is crucial for improving performance, especially in lower precision. Developing more sophisticated methods for handling multi-dimensional tensor layouts and optimizing for specific hardware architectures like Hopper and beyond would also significantly benefit performance. Investigating the interplay between neighborhood attention and other attention mechanisms could lead to novel hybrid approaches. Finally, exploring the theoretical limits of neighborhood attention’s efficiency and comparing it to other subquadratic attention mechanisms warrants further research. Addressing these points will pave the way for wider adoption and impact within the deep learning community.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows how neighborhood attention patterns vary based on window size and dilation, illustrating the spectrum between linear projection and self-attention. It highlights the flexibility of neighborhood attention in controlling the attention span and sparsity.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of the spectrum of possible attention patterns provided by neighborhood attention. Neighborhood attention only attempts to center the query token (red) within the context window (blue), unlike sliding window attention [19] which forces it. Neighborhood attention with window size 1 is equivalent to linear projection (“no attention”). Neighborhood attention approaches self attention as window size grows, and matches it when equal to input size. Dilation introduces sparse global context, and causal masking prevents interaction between query tokens that have a smaller coordinate than neighboring context tokens along the corresponding mode. Window size, dilation, and whether or not causally masked, can be defined per mode/axis.

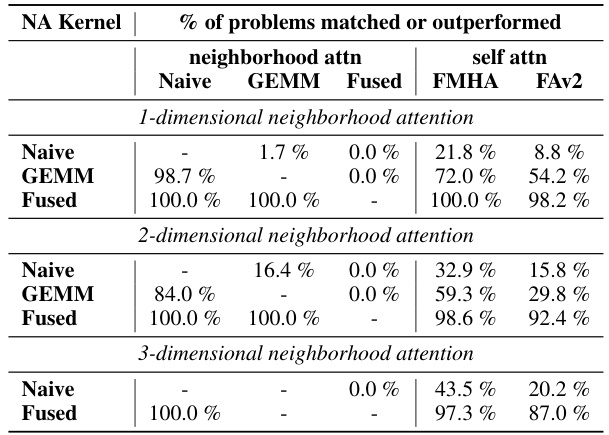

🔼 This figure illustrates the GEMM-based implementation of the 2D Pointwise-Neighborhood (PN) operation in neighborhood attention. It shows how input tensors Q and K are tiled spatially, with K having a halo to accommodate the attention window. These tiles are then processed using a GEMM operation, and the resulting dot products are scattered to form the attention weights.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of our GEMM-based implementation of the 2-D PN operation. Input tensors Q and K are tiled according to their 2-D spatial layout. Q is tiled with a static tile shape, Th × Tw. K is tiled with a haloed shape of the Q tile, Th × Tu, which is a function of the attention window size (kh × kw) and the Q tile coordinates. Once tiles are moved into local memory, they are viewed in matrix layout, and a ThTw × TT × d shaped GEMM is computed (d is embedding dim). Once done, the tile of dot products with shape ThTw × ThTw is scattered into valid attention weights of shape Th × Tw × khkw.

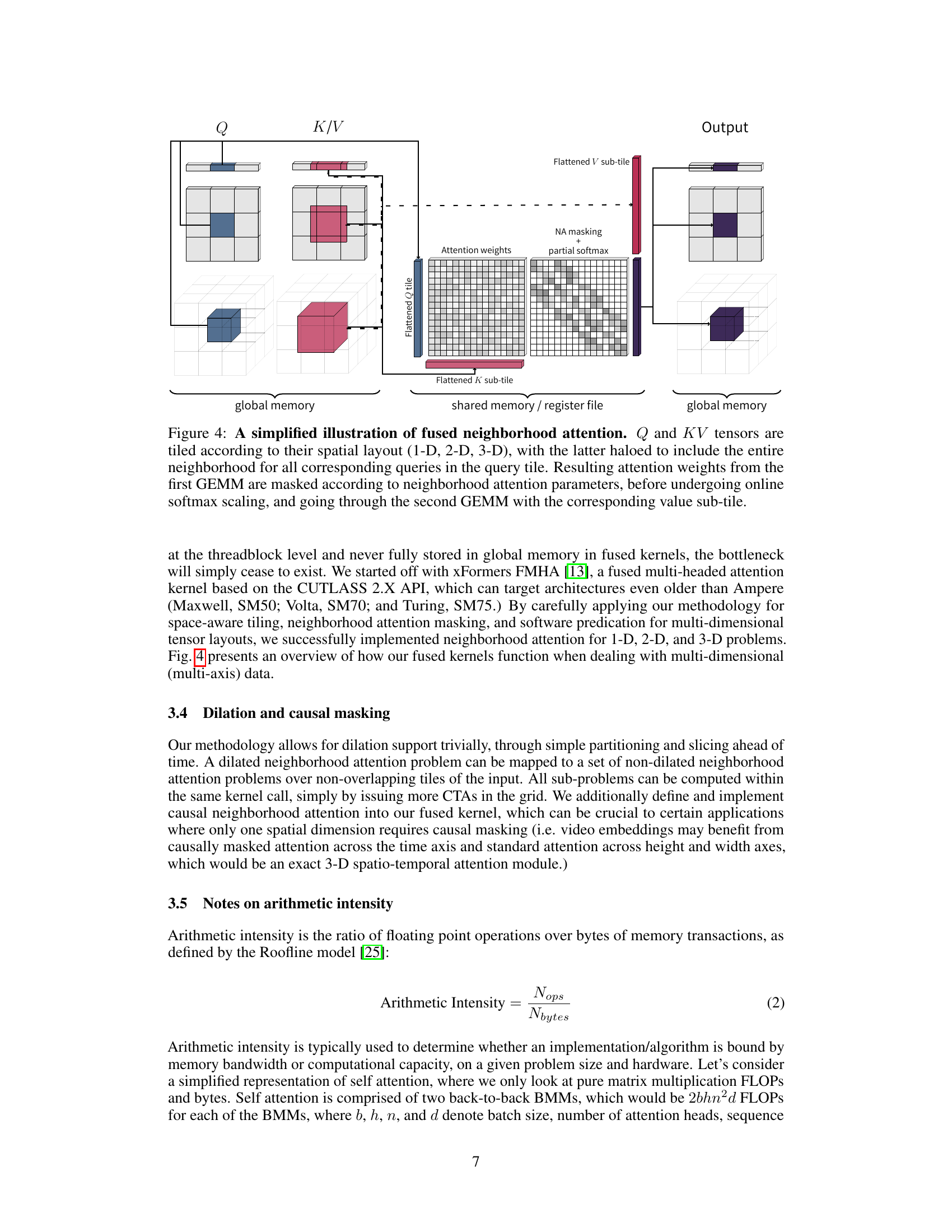

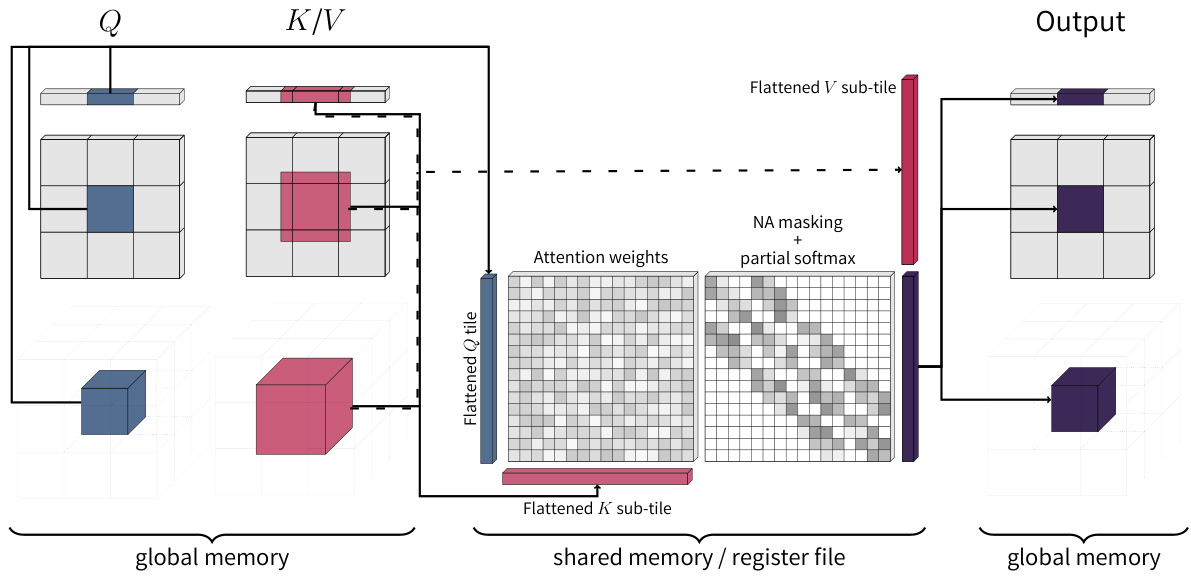

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of fused neighborhood attention. Query (Q) and Key/Value (K/V) tensors are tiled based on their spatial dimensions (1D, 2D, or 3D). The K/V tiles are expanded to include the neighborhood context. The first GEMM operation produces attention weights, which are then masked according to the neighborhood attention parameters and undergo online softmax. A second GEMM operation combines these weights with the Value (V) sub-tiles to produce the final output.

read the caption

Figure 4: A simplified illustration of fused neighborhood attention. Q and KV tensors are tiled according to their spatial layout (1-D, 2-D, 3-D), with the latter haloed to include the entire neighborhood for all corresponding queries in the query tile. Resulting attention weights from the first GEMM are masked according to neighborhood attention parameters, before undergoing online softmax scaling, and going through the second GEMM with the corresponding value sub-tile.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a benchmark comparing the performance of naive, GEMM-based, and fused neighborhood attention kernels against standard self-attention methods (FMHA and FlashAttention V2) using FP16 precision. The benchmark covers a wide range of problem sizes and parameters (batch size, spatial dimensions, number of heads, window size, dilation). The results show the percentage of problems where each neighborhood attention method outperforms or matches the performance of naive kernels and self-attention baselines.

read the caption

Table 1: FP16 forward pass benchmark overview. We benchmark naive neighborhood attention kernels against our proposed GEMM and fused kernels in half precision, over a large set of problem sizes varying in batch size, spatial size, number of attention heads, and dimensions per head, and over different window sizes and dilation values. For every problem size, we also benchmarked self attention running with the xFormers FMHA (our baseline) and Flash Attention V2.

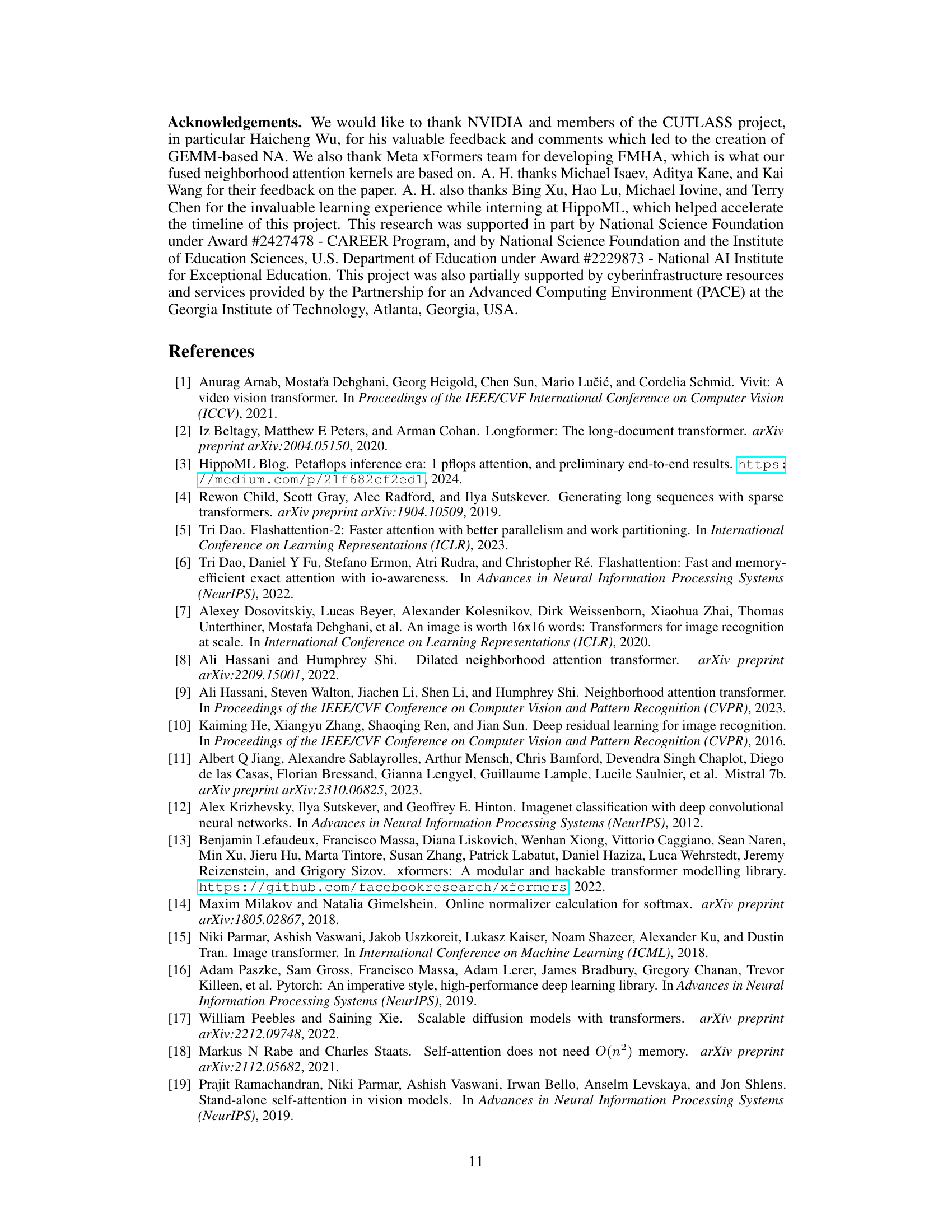

🔼 This table presents a breakdown of the forward pass benchmark results, comparing the performance of GEMM-based and fused neighborhood attention (NA) kernels against naive kernels. It shows the average, minimum, and maximum percentage improvement achieved by GEMM-based and fused NA kernels over naive kernels in both FP16 and FP32 precision. The table also highlights cases where naive kernels might outperform GEMM-based kernels.

read the caption

Table 3: Forward pass benchmark breakdown. Both GEMM-based and fused NA improve the baseline naive kernels on average. However, there exist cases in which naive kernels may be preferable to GEMM-based in both FP16 and FP32, but naive is rarely a good choice in half precision where both naive and GEMM are more memory bandwidth bound than fused.

🔼 This table shows the performance improvement of GEMM-based and fused neighborhood attention kernels compared to naive kernels for both forward and backward passes in half-precision. It provides average, minimum, and maximum improvements for 1D, 2D, and 3D problems. The results highlight that while fused kernels generally offer the best performance, there are some cases where naive or GEMM-based kernels might perform better, particularly in the backward pass.

read the caption

Table 4: Forward + backward pass benchmark breakdown. Improvements over naive, while not as significant as in the forward pass, are still significant. We report benchmark the full forward and backward pass in half precision only, because most training is done in lower precision.

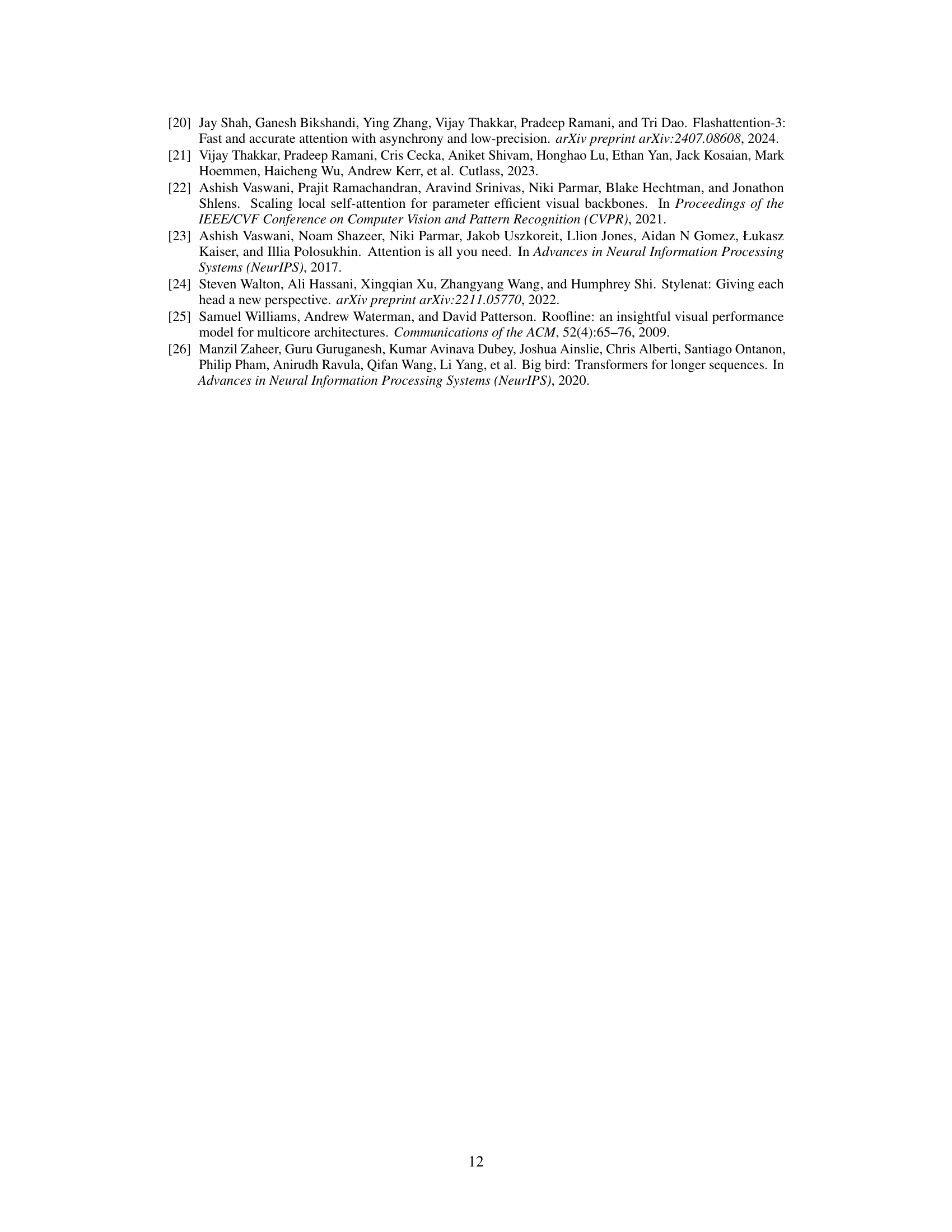

🔼 This table presents the results of applying GEMM-based and fused neighborhood attention kernels to several ImageNet classification models (NAT and DiNAT variants). It shows the throughput improvements (in imgs/sec) and top-1 accuracy for various model sizes and configurations, comparing the naive, GEMM-based, and fused kernel implementations. The table highlights significant improvements in FP16 throughput for the fused kernels, particularly in larger models. It also notes that the half-precision GEMM kernels show less improvement due to memory alignment issues.

read the caption

Table 5: Model-level throughput changes when using our proposed GEMM-based and fused kernels in ImageNet classification. Hierarchical vision transformers NAT and DiNAT can see between 26% to 104% improvement in FP16 throughput on an A100 (batch size 128) with our proposed fused kernel. Suffering from the memory alignment issue, our half precision GEMM kernels usually result in a much smaller improvement over naive kernels, particularly the tiled variants. The same measurements with FP32 precision are presented in Tab. 6.

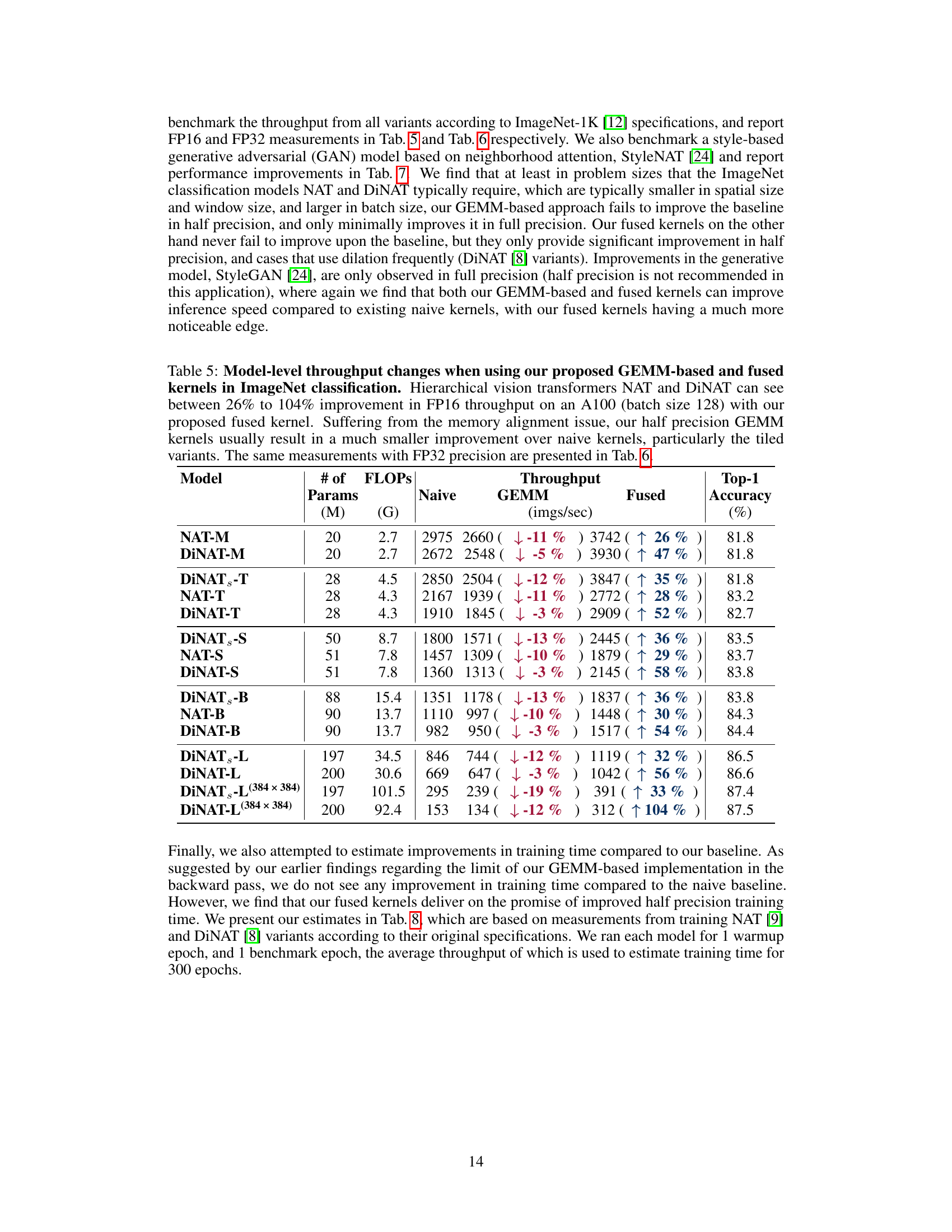

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the performance of GEMM-based and fused neighborhood attention kernels in ImageNet classification using full precision (FP32). It compares the throughput (images per second) and top-1 accuracy of different models (NAT and DiNAT variants with varying sizes) using naive, GEMM-based, and fused kernels. The table highlights the performance gains achieved by the proposed kernels, particularly in scenarios where memory alignment issues are mitigated.

read the caption

Table 6: Model-level throughput changes when using our proposed GEMM-based and fused kernels in ImageNet classification (full precision). While fused attention kernels are not expected to have as large of an edge over BMM-style attention kernels in FP32, our fused kernels still happen to outperform naive kernels in full precision. It is also visible that our GEMM kernels can outperform naive kernels when we eliminate the memory alignment issue. That said, our FP32 GEMM kernels still impose a maximum alignment of 1 element on the attention weights tensor, which limits its ability to compete with other BMM-style attention kernels.

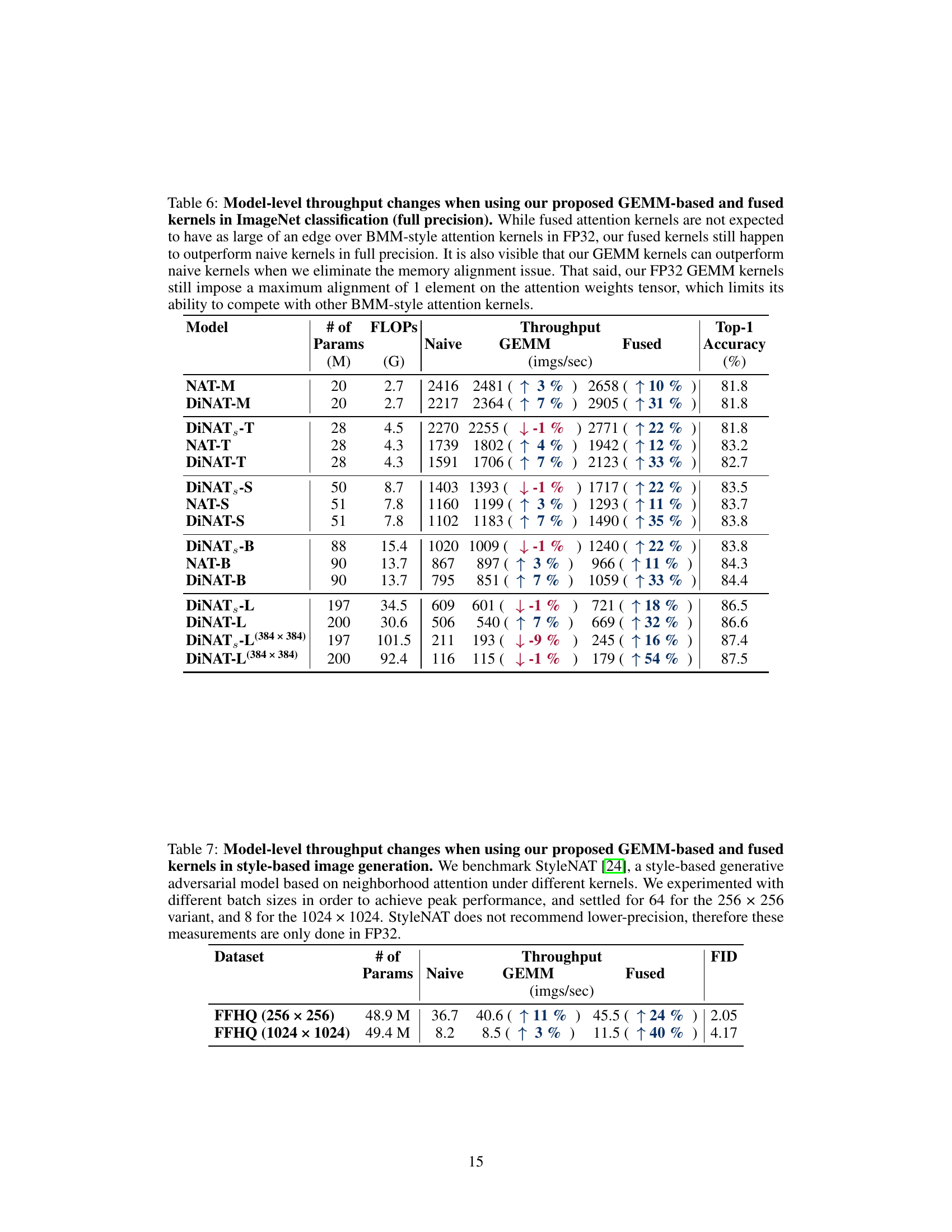

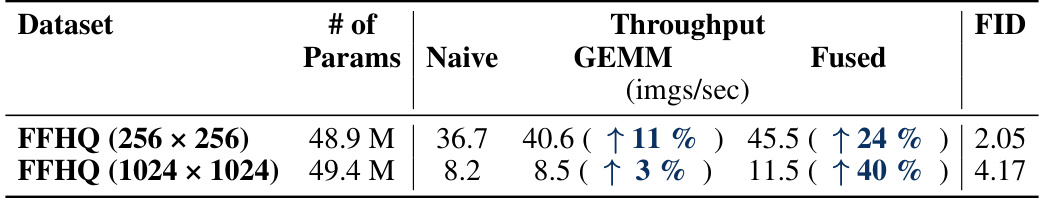

🔼 This table shows the performance improvement of the StyleNAT model using different attention kernel implementations (Naive, GEMM, Fused). It highlights the throughput (images per second) and FID (Fréchet Inception Distance) scores for two different resolutions (256x256 and 1024x1024) of the FFHQ dataset. The improvements are shown as percentage increases compared to the naive kernel.

read the caption

Table 7: Model-level throughput changes when using our proposed GEMM-based and fused kernels in style-based image generation. We benchmark StyleNAT [24], a style-based generative adversarial model based on neighborhood attention under different kernels. We experimented with different batch sizes in order to achieve peak performance, and settled for 64 for the 256 × 256 variant, and 8 for the 1024 × 1024. StyleNAT does not recommend lower-precision, therefore these measurements are only done in FP32.

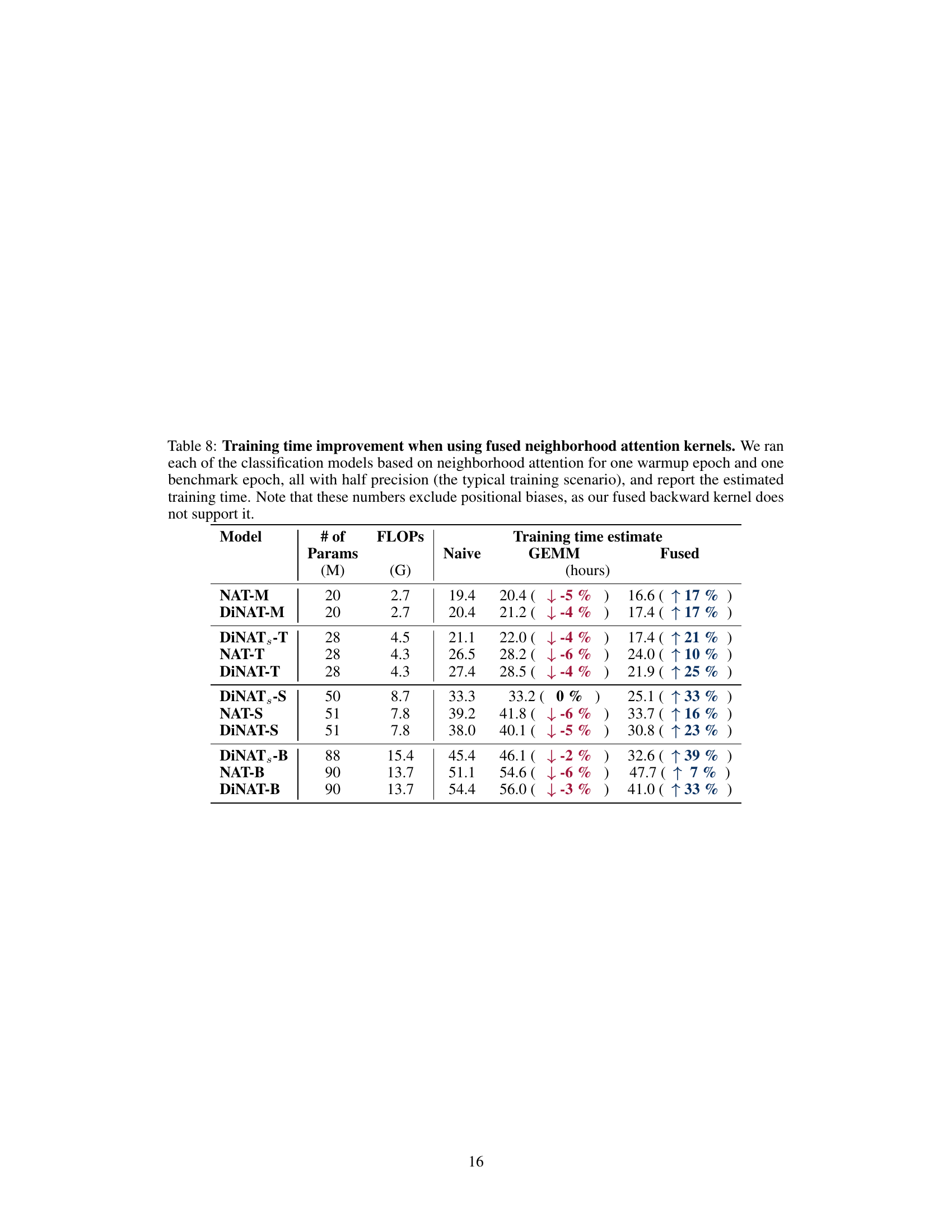

🔼 This table presents the training time improvements observed when using fused neighborhood attention kernels compared to naive and GEMM-based kernels. The results are shown for various models (NAT-M, DINAT-M, etc.) with different numbers of parameters and FLOPs. Training time is estimated based on one warmup and one benchmark epoch, using half precision. The table indicates percentage changes in training time for each kernel type (Naive, GEMM, and Fused) relative to the naive approach. Note that positional biases are excluded as the fused backward kernel doesn’t support them.

read the caption

Table 8: Training time improvement when using fused neighborhood attention kernels. We ran each of the classification models based on neighborhood attention for one warmup epoch and one benchmark epoch, all with half precision (the typical training scenario), and report the estimated training time. Note that these numbers exclude positional biases, as our fused backward kernel does not support it.

Full paper#