TL;DR#

Optimizing graph diffusion models for specific objectives is challenging, especially when those objectives are non-differentiable. Existing methods struggle with this because they either approximate reward signals or rely on earlier graph generative models. This limitation hinders progress in various domains that heavily rely on graphs such as drug discovery.

The researchers introduce GDPO to address these challenges. GDPO uses reinforcement learning and a specially designed “eager policy gradient” to optimize graph diffusion models directly. Experiments show GDPO achieves state-of-the-art performance and high sample efficiency on various tasks, significantly outperforming existing methods. This work makes significant contributions by bridging the gap between graph diffusion models and reinforcement learning, opening exciting possibilities for optimizing graph generation in diverse application areas.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in graph generation and reinforcement learning. It bridges the gap between graph diffusion models and reinforcement learning, offering a novel and efficient approach to optimize graph generation for complex, non-differentiable objectives. This opens new avenues for research in drug discovery, materials science, and other fields relying on graph-based data, leading to significant advancements in these areas.

Visual Insights#

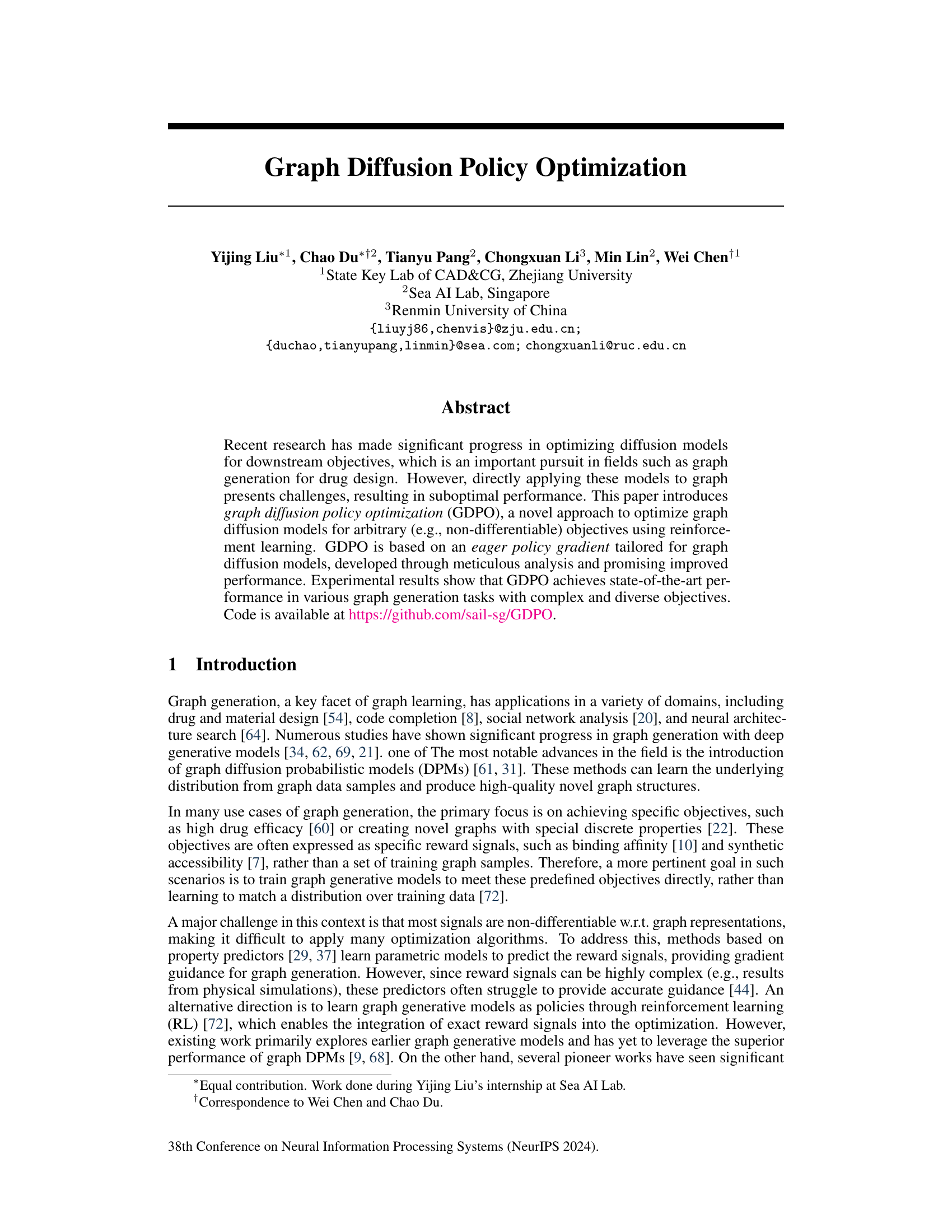

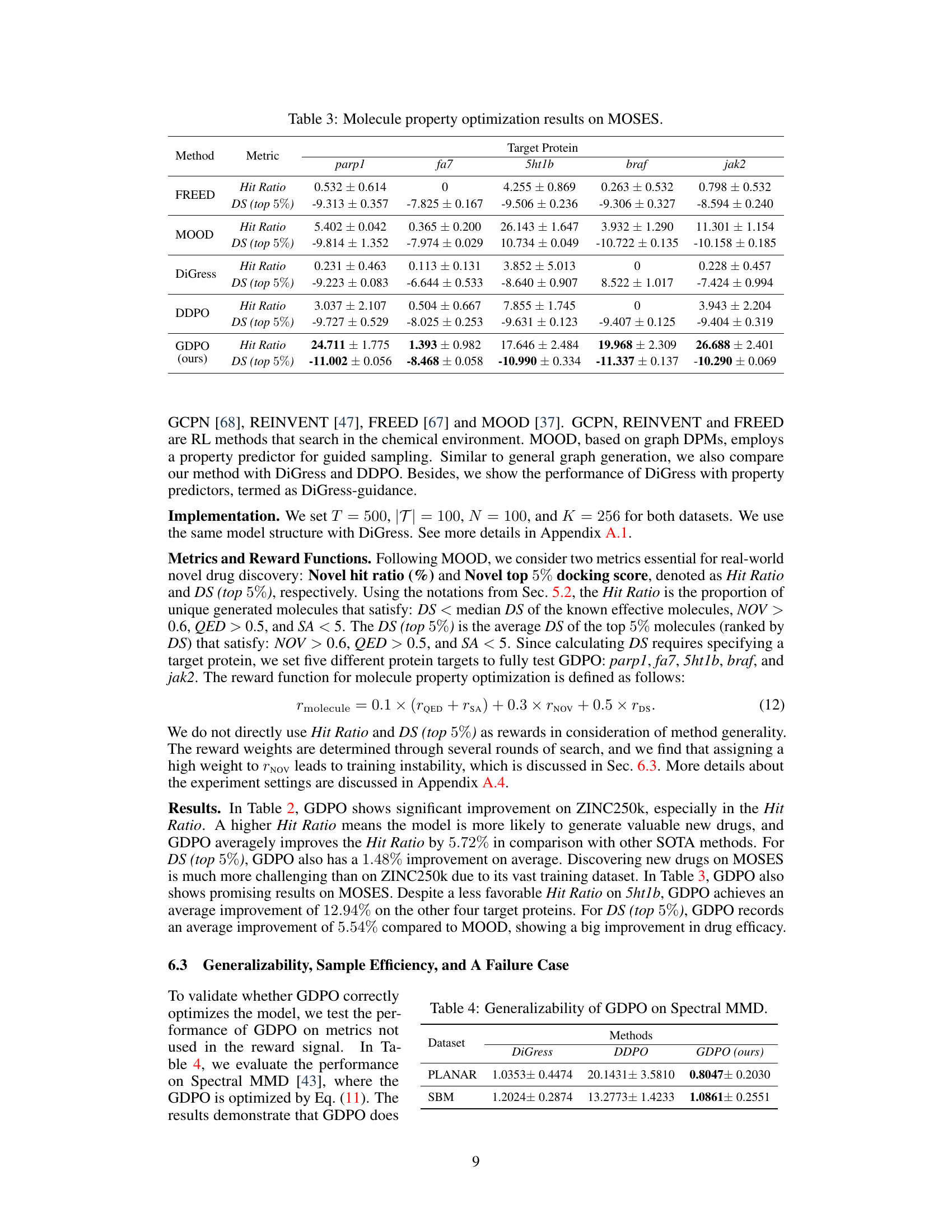

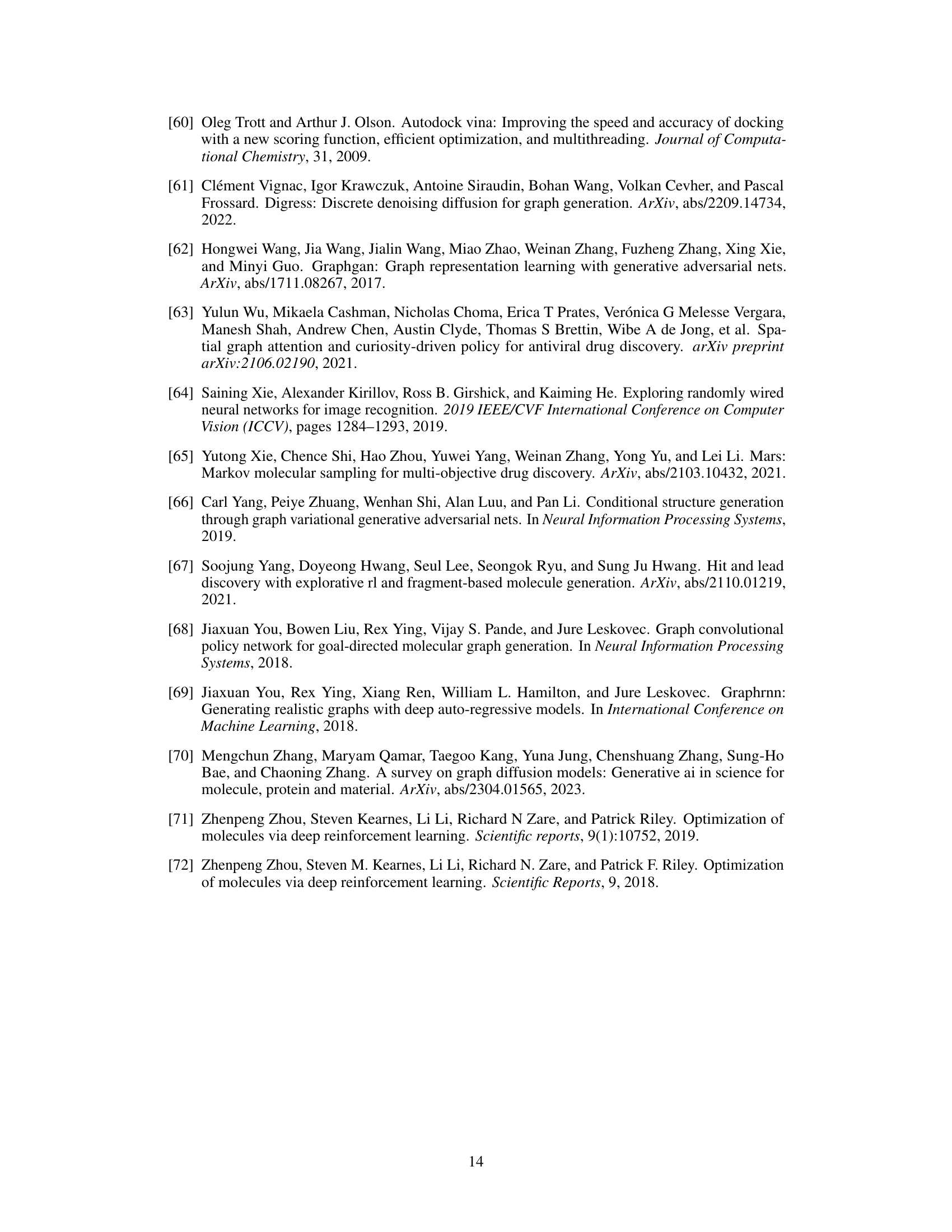

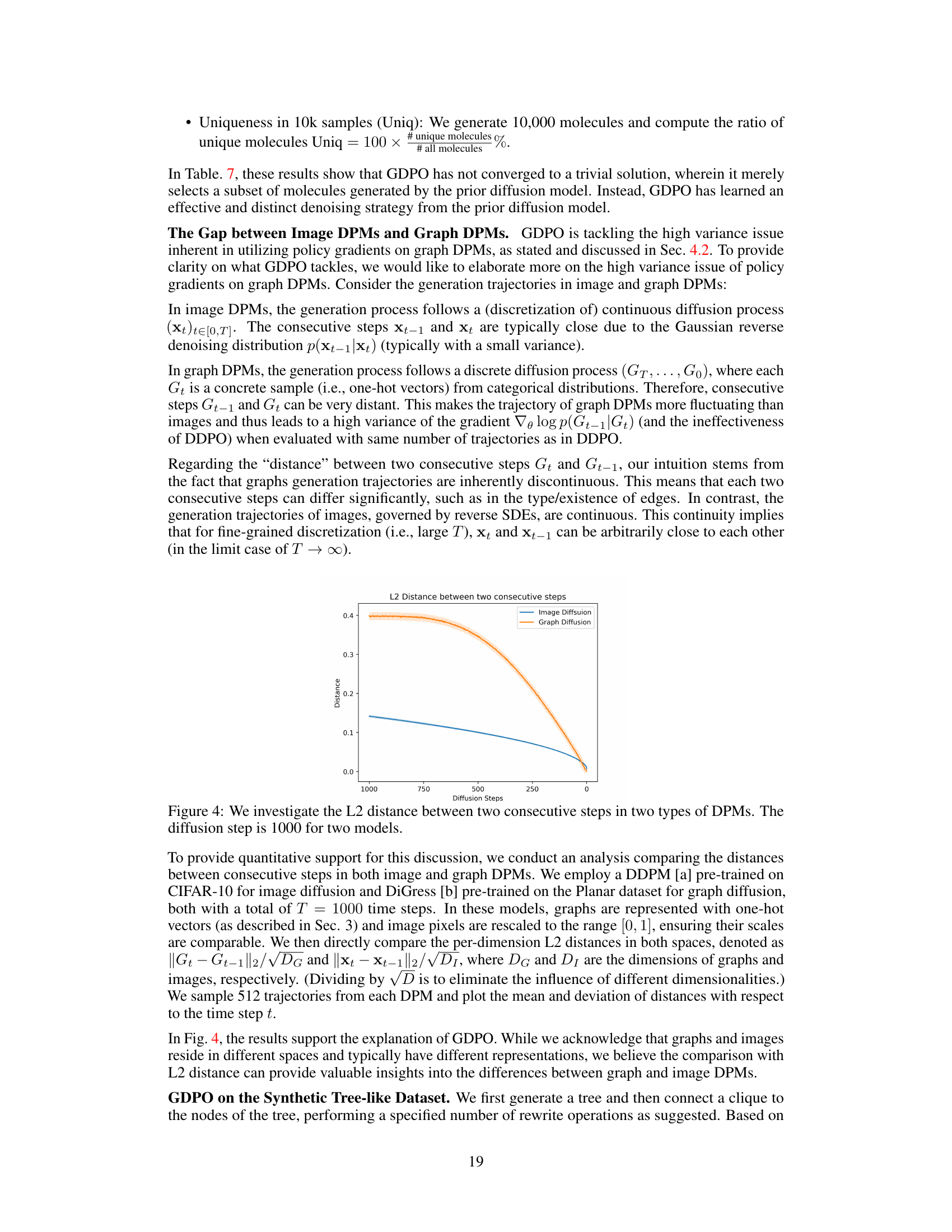

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main steps of the Graph Diffusion Policy Optimization (GDPO) algorithm. The first step involves sampling multiple generation trajectories from a graph diffusion probabilistic model (DPM). Each trajectory represents a sequence of graph states, starting from a noisy graph (Gt) and progressing towards a cleaner graph (G0). The reward function is then queried for each generated graph (G0) to obtain a reward signal reflecting the quality of the generated graph based on the defined objective. The second step uses these reward signals and gradients of the log probability of the generated graph given the noisy graph to estimate the policy gradient, which is then used to update the DPM parameters, ultimately optimizing the model to generate higher-quality graphs based on the specified objective function.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of GDPO. (1) In each optimization step, GDPO samples multiple generation trajectories from the current Graph DPM and queries the reward function with different Go. (2) For each trajectory, GDPO accumulates the gradient ∇log pθ(G0|Gt) of each (G0, Gt) pair and assigns a weight to the aggregated gradient based on the corresponding reward signal. Finally, GDPO estimates the eager policy gradient by averaging the aggregated gradient from all trajectories.

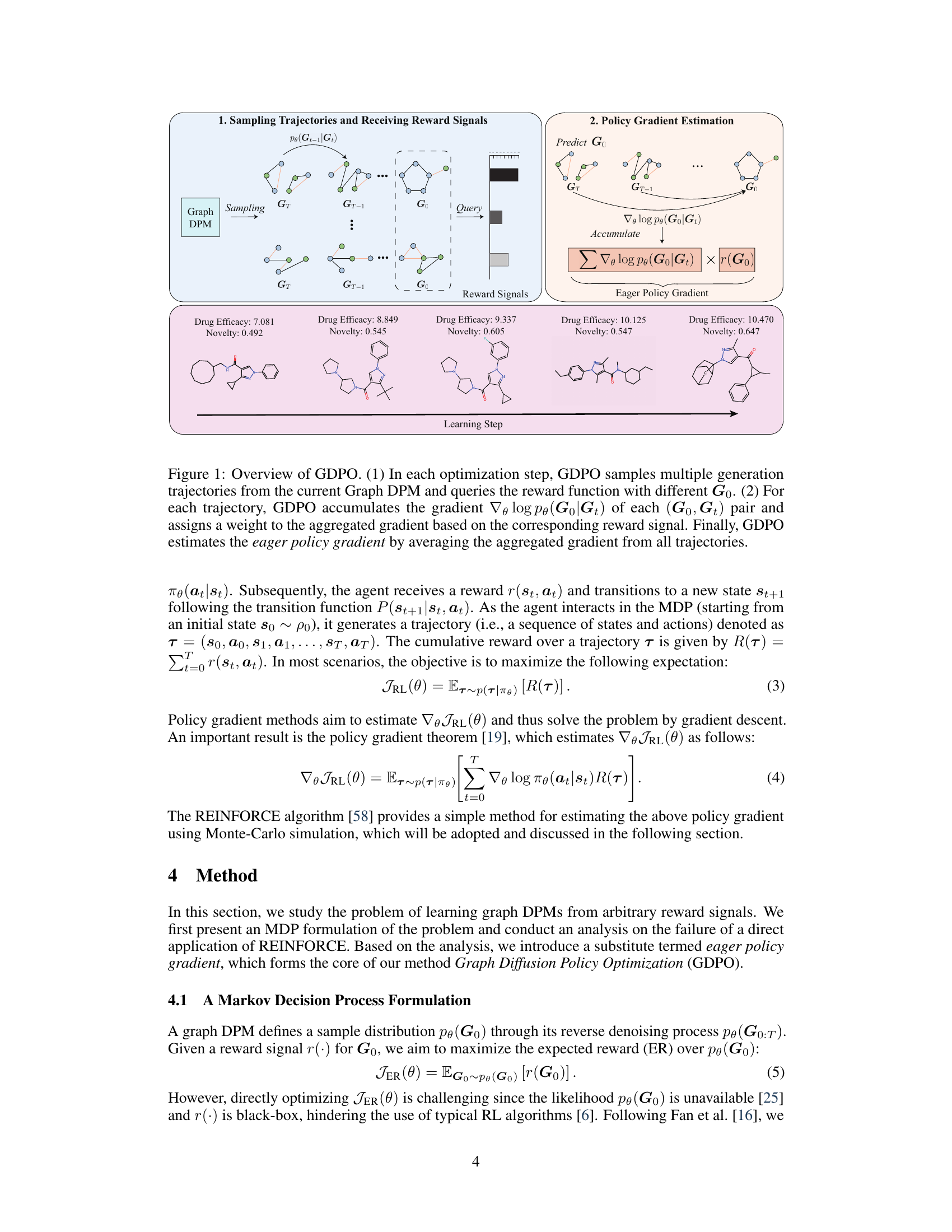

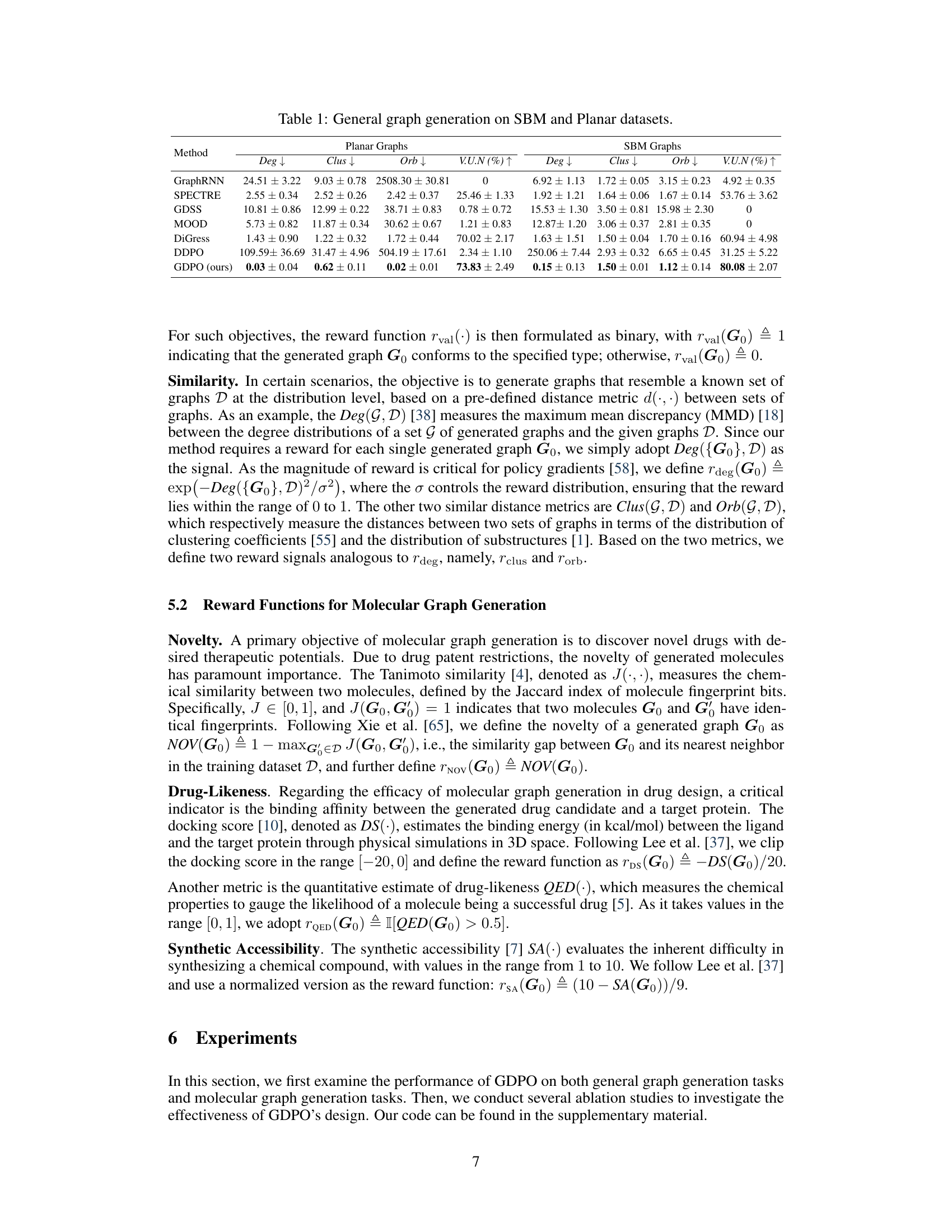

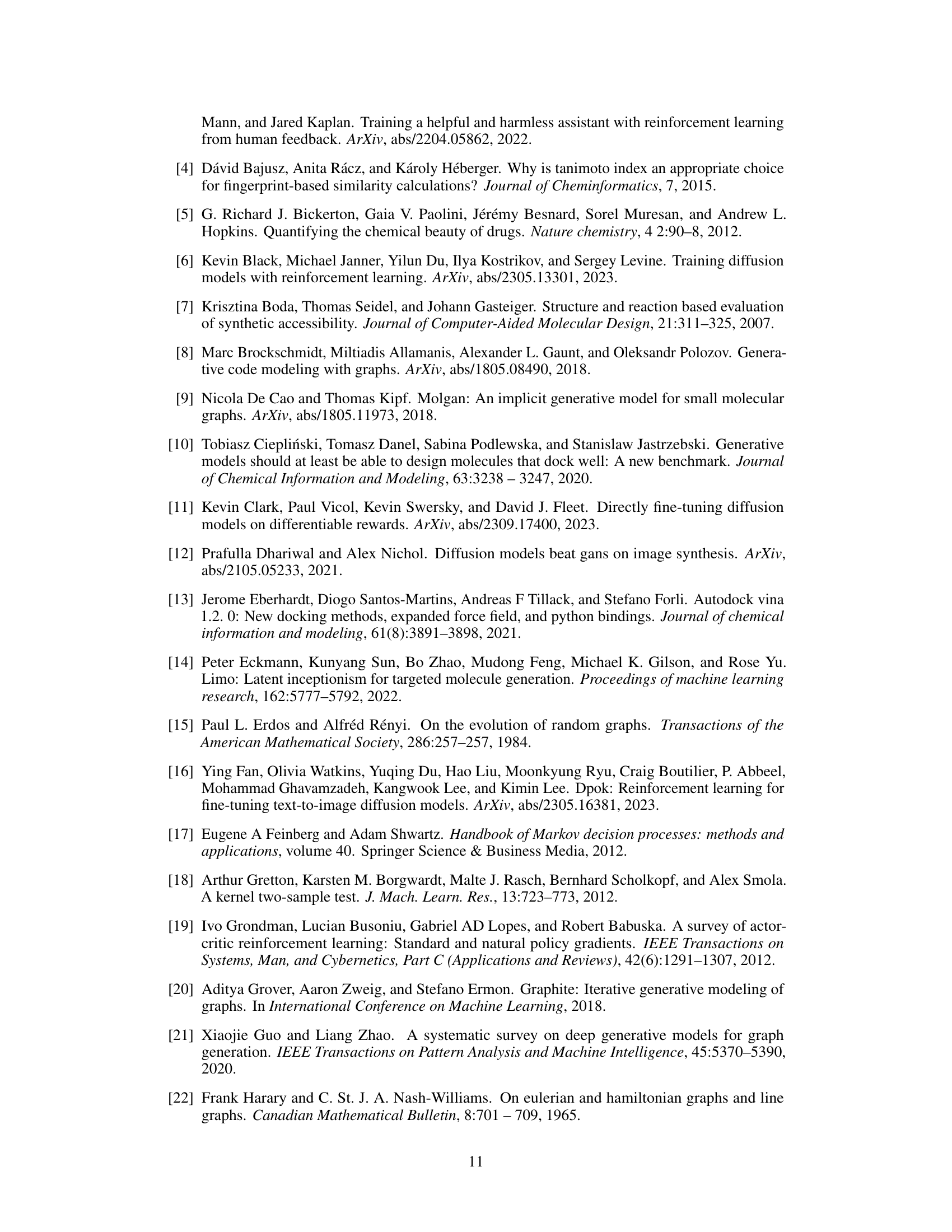

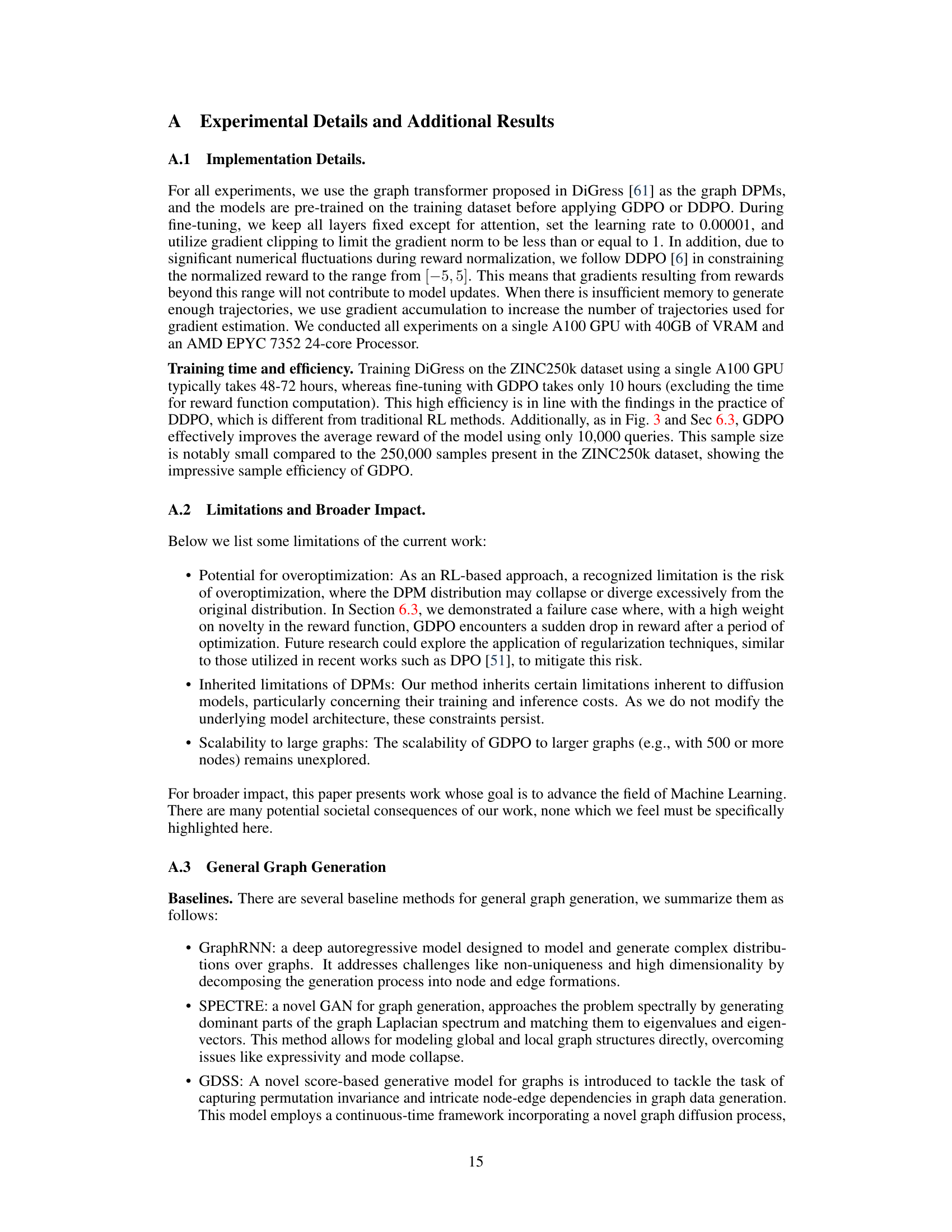

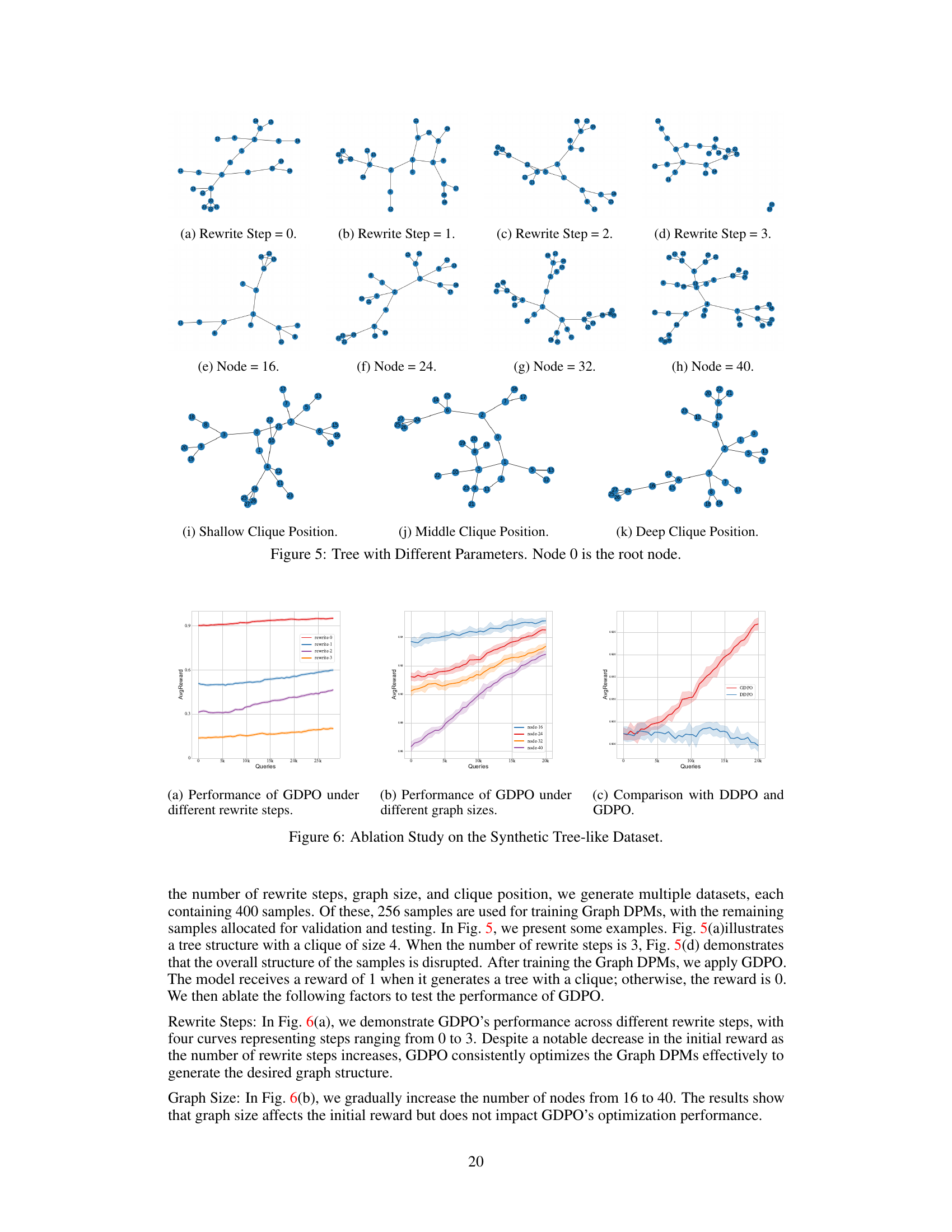

🔼 This table presents the results of general graph generation experiments on two benchmark datasets: the Stochastic Block Model (SBM) and Planar graphs. Several different graph generation methods are compared, including GraphRNN, SPECTRE, GDSS, MOOD, DiGress, DDPO, and the proposed GDPO method. The table shows the performance of each method across four metrics: Deg (degree distribution), Clus (clustering coefficient distribution), Orb (orbit count distribution), and VUN (percentage of generated graphs that are valid, unique, and novel). Lower values for Deg, Clus, and Orb indicate better performance (i.e., closer agreement with the test dataset distribution). Higher VUN indicates better performance. The results demonstrate GDPO’s superiority over other state-of-the-art methods.

read the caption

Table 1: General graph generation on SBM and Planar datasets.

In-depth insights#

GDPO: Policy Gradient#

The heading ‘GDPO: Policy Gradient’ suggests a section detailing the core algorithm of Graph Diffusion Policy Optimization. It likely describes how GDPO uses policy gradients, a reinforcement learning technique, to optimize graph diffusion models. The discussion probably involves formulating the graph generation process as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), defining states, actions, and rewards based on graph properties and objectives. The core of this section would likely focus on the specific policy gradient update rule used by GDPO, emphasizing how it addresses challenges unique to discrete graph domains. A key aspect may be GDPO’s modification to standard REINFORCE, potentially involving an ’eager’ approach to improve sample efficiency and reduce variance. The explanation would also likely cover the algorithm’s hyperparameters and their impact on performance, along with implementation details. Finally, the section might include theoretical justifications for the algorithm’s design choices and possibly present experimental results demonstrating its effectiveness compared to baseline methods. The use of reinforcement learning to guide the graph generation process, in contrast to standard supervised learning approaches is a significant contribution of this method.

Graph DPMs: RL#

The hypothetical heading ‘Graph DPMs: RL’ suggests a research area focusing on the intersection of graph-based diffusion probabilistic models (DPMs) and reinforcement learning (RL). This implies using RL techniques to optimize or control the generation process of graph DPMs. A key challenge would be handling the discrete nature of graph data, which contrasts with the continuous data often used in traditional RL applications. The research might explore how to define reward functions appropriate for graph generation tasks and how to efficiently learn policies that maximize these rewards. Potential applications could include controllable generation of graphs with specific properties, or optimizing DPMs for downstream tasks where the reward signal is non-differentiable. The combination of graph DPMs, known for their high-quality sample generation, and RL’s ability to handle complex objectives, presents exciting possibilities but also significant methodological hurdles, particularly regarding efficient gradient estimation in discrete spaces. Novel approaches for policy gradient estimation or alternative RL methods might be crucial. The overall focus would likely be on developing new algorithms that address these challenges and showcase compelling applications in diverse graph-related fields.

Reward Function Design#

Effective reward function design is crucial for the success of reinforcement learning (RL) based graph generation. A poorly designed reward function can lead to suboptimal or even nonsensical results. The choice of reward function directly shapes the learning process and the ultimate properties of the generated graphs. The paper highlights this by exploring various reward functions for both general and molecular graph generation. For general graphs, the reward function might incentivize specific graph properties like connectedness, degree distribution, or clustering coefficient. The complexity of the reward function needs to be carefully balanced against the computational cost of evaluating it. In molecular graph generation, the reward function could incorporate properties like drug-likeness, synthetic accessibility, or binding affinity. The challenge is to design reward functions that accurately capture the desired properties while remaining computationally feasible, particularly considering the potentially large search space and high computational cost of graph generation and property evaluation. Furthermore, the chosen reward should encourage diversity and avoid overfitting or premature convergence to a limited set of high-reward solutions. The careful tuning and selection of reward function weights is another critical aspect of this task to balance multiple competing objectives.

GDPO Limitations#

The Graph Diffusion Policy Optimization (GDPO) method, while demonstrating state-of-the-art performance in various graph generation tasks, is not without limitations. Overoptimization, a common issue with reinforcement learning-based approaches, presents a risk of the model’s distribution collapsing or diverging significantly from the original data distribution. The method also inherits the computational costs associated with diffusion models, particularly regarding training and inference, especially when dealing with large graphs. Furthermore, the scalability to extremely large graphs remains an open challenge. While GDPO exhibits improved sample efficiency compared to other methods, the dependence on effective reward signals is a crucial factor. Inaccuracies or biases in the reward function could severely hinder performance. Finally, the eager policy gradient, though effective, is a biased estimator, potentially introducing systematic error. Future research should explore methods to mitigate overoptimization, improve scalability, and enhance the robustness of the method to imperfect reward functions.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending GDPO to handle larger, more complex graphs is crucial for real-world applicability. This might involve investigating more efficient sampling techniques or developing novel architectures better suited for massive graphs. Improving the scalability and efficiency of the reward function evaluation is also vital; current methods can be computationally expensive, hindering the use of GDPO in high-throughput settings. Furthermore, research into more sophisticated reward function designs that better capture nuanced objectives is necessary. The current binary reward functions are simplistic and may not fully reflect the complexity of many real-world applications. Finally, exploring the theoretical underpinnings of GDPO could reveal deeper insights into its effectiveness and limitations. This includes a rigorous analysis of the bias-variance trade-off and a comparison to other policy optimization methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

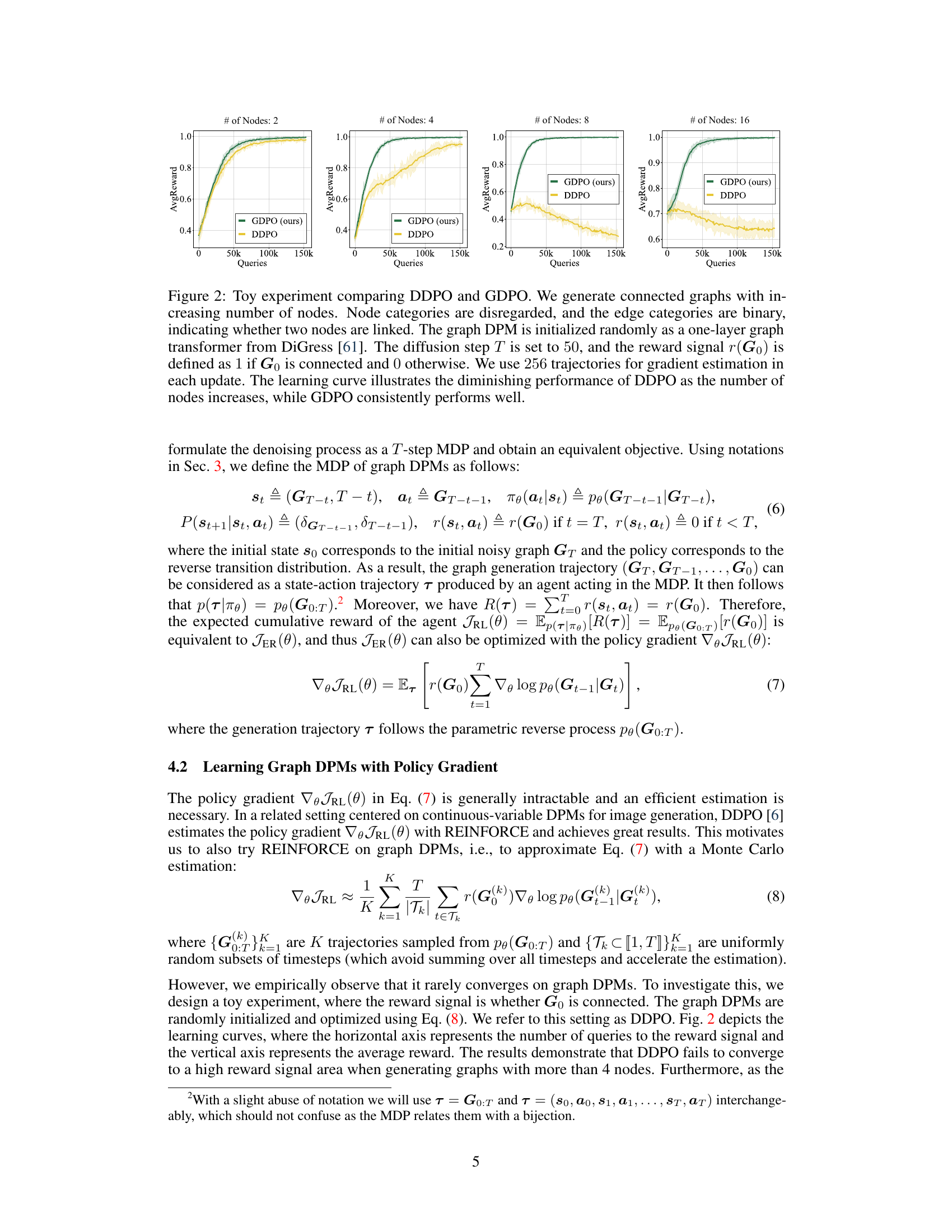

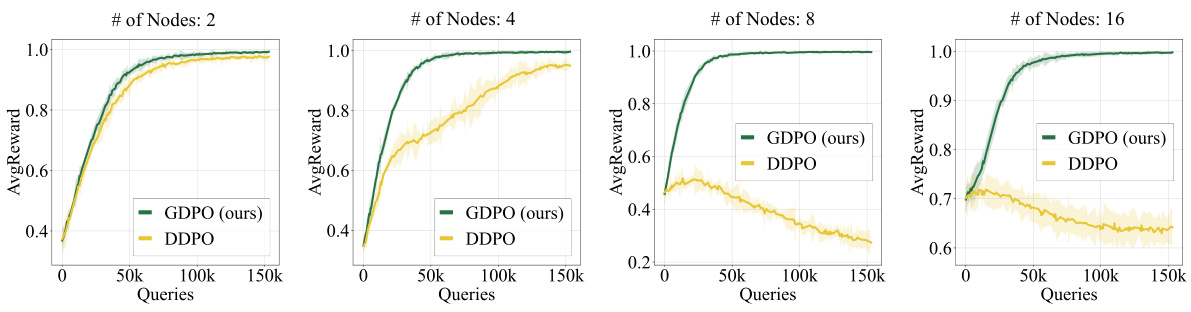

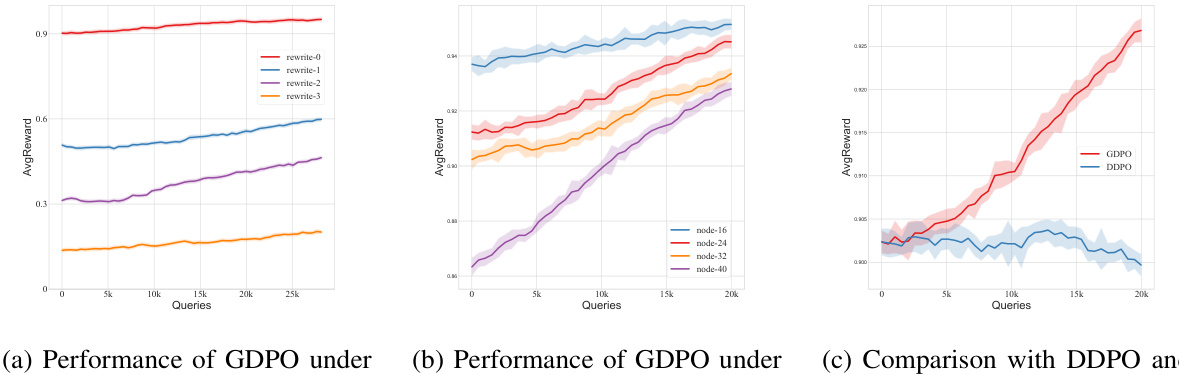

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of DDPO and GDPO’s performance on a toy experiment involving generating connected graphs with varying numbers of nodes. The results demonstrate that GDPO maintains its performance as graph complexity increases, unlike DDPO, highlighting GDPO’s robustness in handling complex graphs.

read the caption

Figure 2: Toy experiment comparing DDPO and GDPO. We generate connected graphs with increasing number of nodes. Node categories are disregarded, and the edge categories are binary, indicating whether two nodes are linked. The graph DPM is initialized randomly as a one-layer graph transformer from DiGress [61]. The diffusion step T is set to 50, and the reward signal r(Go) is defined as 1 if Go is connected and 0 otherwise. We use 256 trajectories for gradient estimation in each update. The learning curve illustrates the diminishing performance of DDPO as the number of nodes increases, while GDPO consistently performs well.

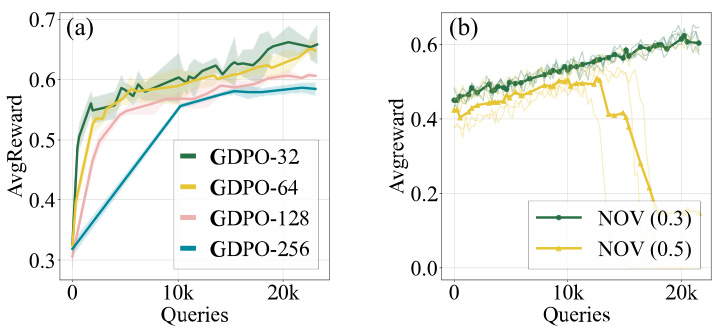

🔼 This figure analyzes the impact of two key hyperparameters on the performance of GDPO: the number of trajectories used for gradient estimation and the weight assigned to the novelty reward signal (rNOV). In (a), it shows that GDPO achieves good sample efficiency, reaching a significant improvement in average reward with relatively few queries (around 10k) even with fewer trajectories. In (b), it demonstrates that assigning too high a weight to novelty can lead to training instability and reduced performance. It highlights the need for a balance between exploring novel molecules and optimizing overall drug efficacy.

read the caption

Figure 3: We investigate two key factors of GDPO on ZINC250k, with the target protein being 5ht1b. Similarly, the vertical axis represents the total queries, while the horizontal axis represents the average reward.(a) We vary the number of trajectories for gradient estimation. (b) We fix the weight of rdeg and rsa, and change the weight of rNOV while ensuring the total weight is 1.

🔼 This figure provides a visual overview of the Graph Diffusion Policy Optimization (GDPO) process. It illustrates the two main steps involved: 1) Sampling multiple generation trajectories using a graph diffusion probabilistic model (DPM) and querying a reward function for each generated graph (Go). 2) Estimating the eager policy gradient by calculating the gradient of the log probability of each trajectory (from Go to Gt), weighting them according to their reward signals, and averaging the results. The figure uses a diagrammatic representation to show the flow of the process and the relationships between the different components.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of GDPO. (1) In each optimization step, GDPO samples multiple generation trajectories from the current Graph DPM and queries the reward function with different Go. (2) For each trajectory, GDPO accumulates the gradient ∇elog po(Go|Gt) of each (Go, Gt) pair and assigns a weight to the aggregated gradient based on the corresponding reward signal. Finally, GDPO estimates the eager policy gradient by averaging the aggregated gradient from all trajectories.

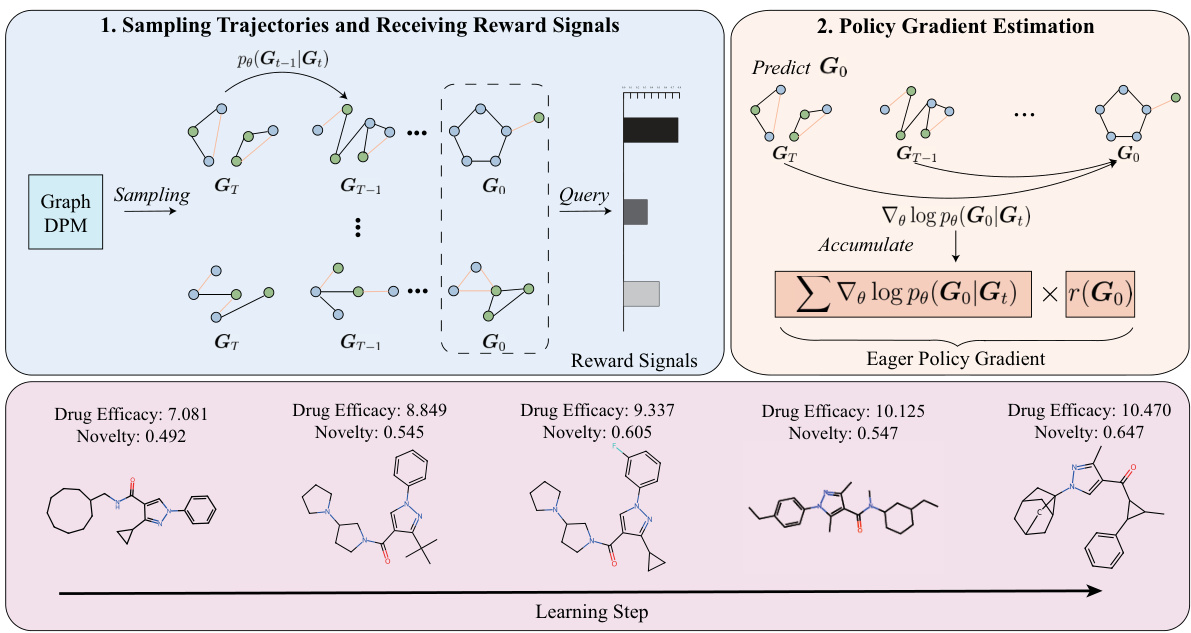

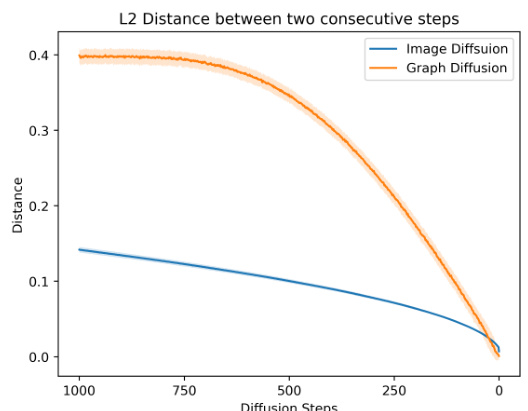

🔼 This figure compares the L2 distance between consecutive steps in image diffusion models and graph diffusion models. The x-axis represents the diffusion steps, and the y-axis represents the L2 distance. The image diffusion model shows a consistently low and relatively stable L2 distance across all steps. In contrast, the graph diffusion model exhibits a much higher and more variable L2 distance, especially at the later steps. This illustrates the discontinuous and more erratic nature of graph diffusion processes compared to the continuous nature of image diffusion processes.

read the caption

Figure 4: We investigate the L2 distance between two consecutive steps in two types of DPMs. The diffusion step is 1000 for two models.

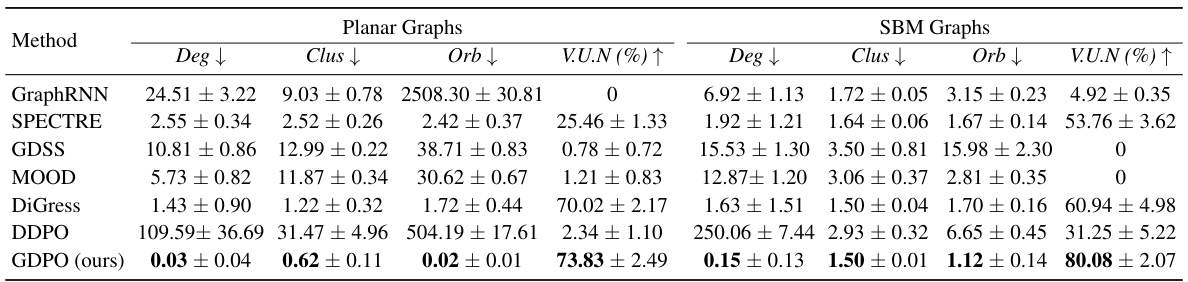

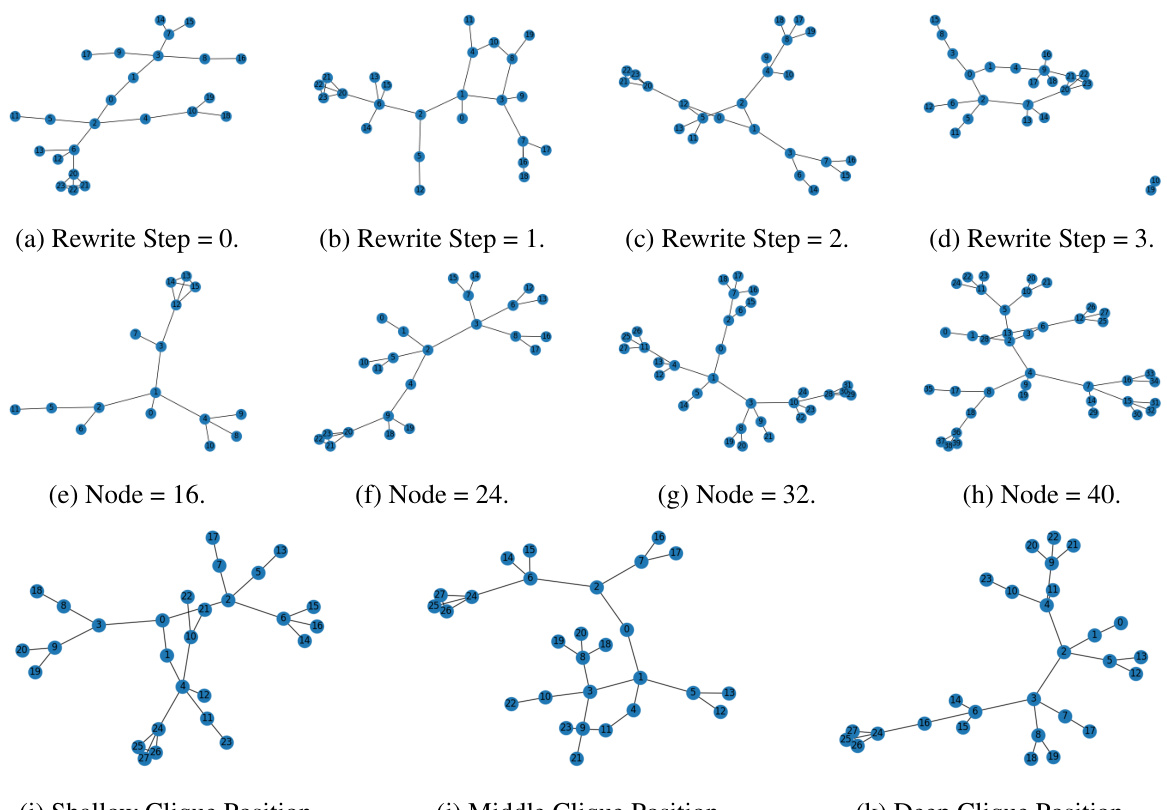

🔼 This figure shows examples of graphs generated using a tree-like structure with varying parameters. The parameters varied are the number of rewrite steps applied to the initial tree structure (affecting its complexity), and the size of the graph (number of nodes). Also shown are three variations in clique position, demonstrating placement at the shallow, middle, and deep levels of the tree structure. These graphs demonstrate the diversity possible when manipulating the initial tree structure and the addition of a clique.

read the caption

Figure 5: Tree with Different Parameters. Node 0 is the root node.

🔼 This figure presents an ablation study on a synthetic tree-like dataset, where the performance of GDPO is evaluated under different parameters. Specifically, it demonstrates how the model performs under varying numbers of rewrite steps, graph sizes, and clique positions. The results show the robustness of GDPO to these changes, showcasing its ability to consistently optimize the graph DPMs across a range of conditions. It also includes a comparison between GDPO and DDPO, highlighting GDPO’s superior performance in handling challenging data generation tasks.

read the caption

Figure 6: Ablation Study on the Synthetic Tree-like Dataset.

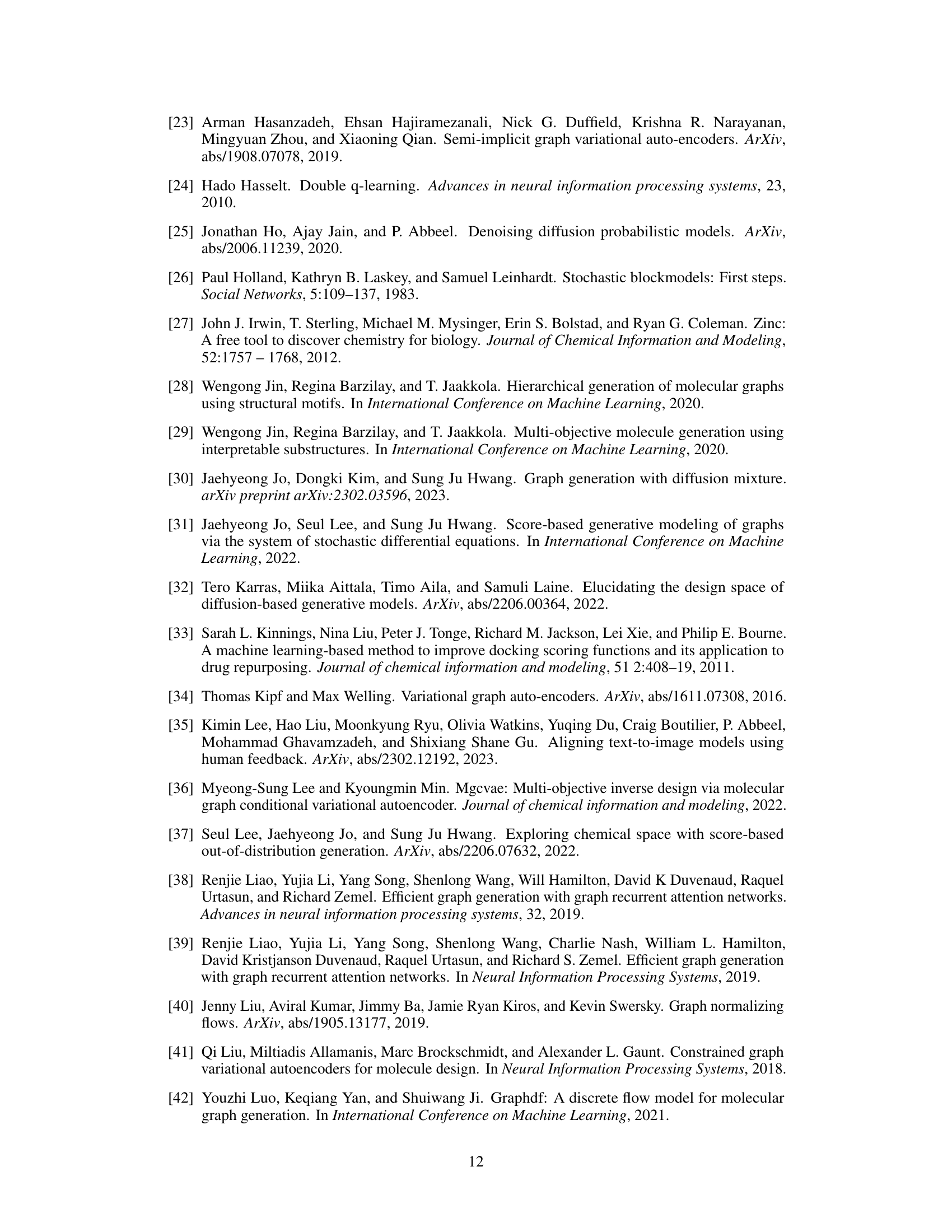

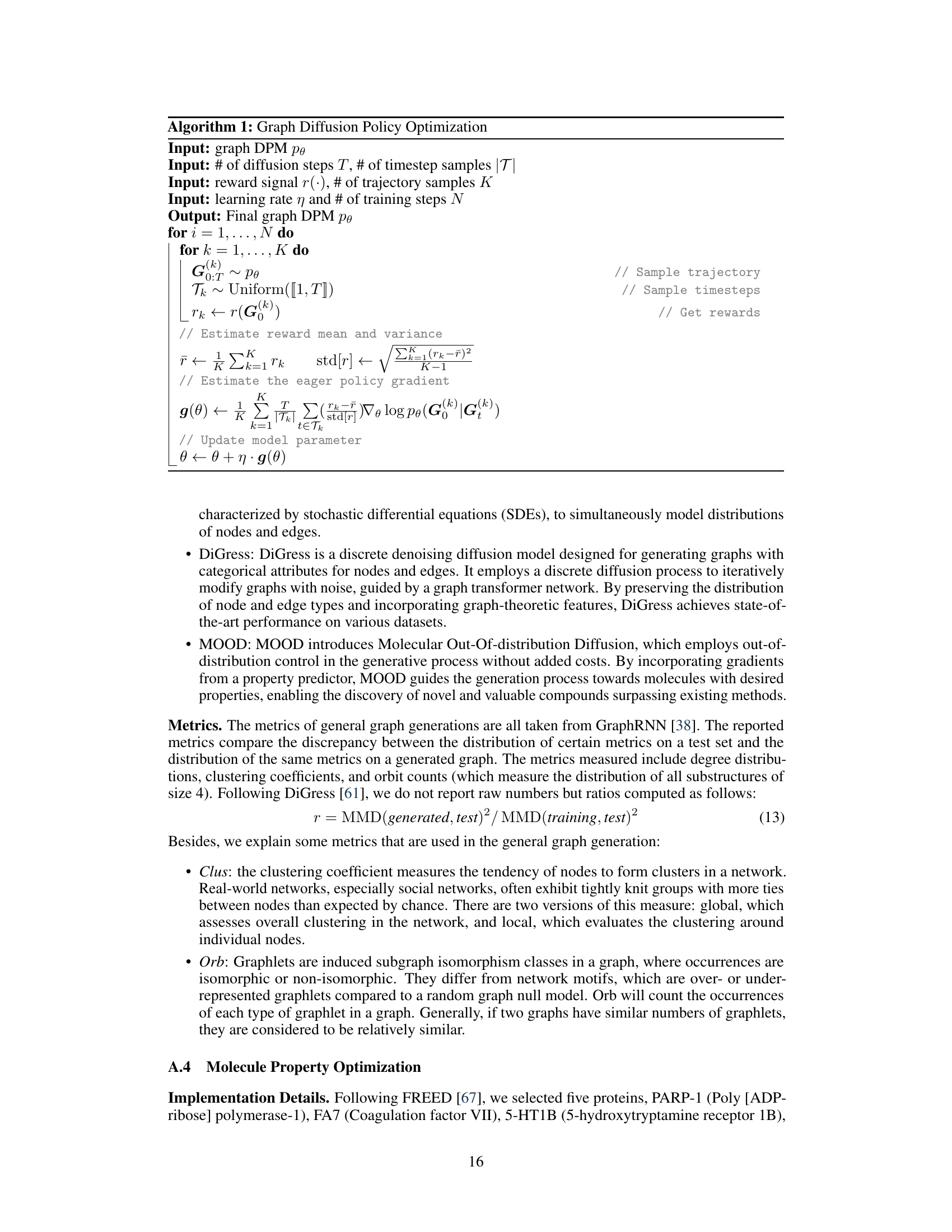

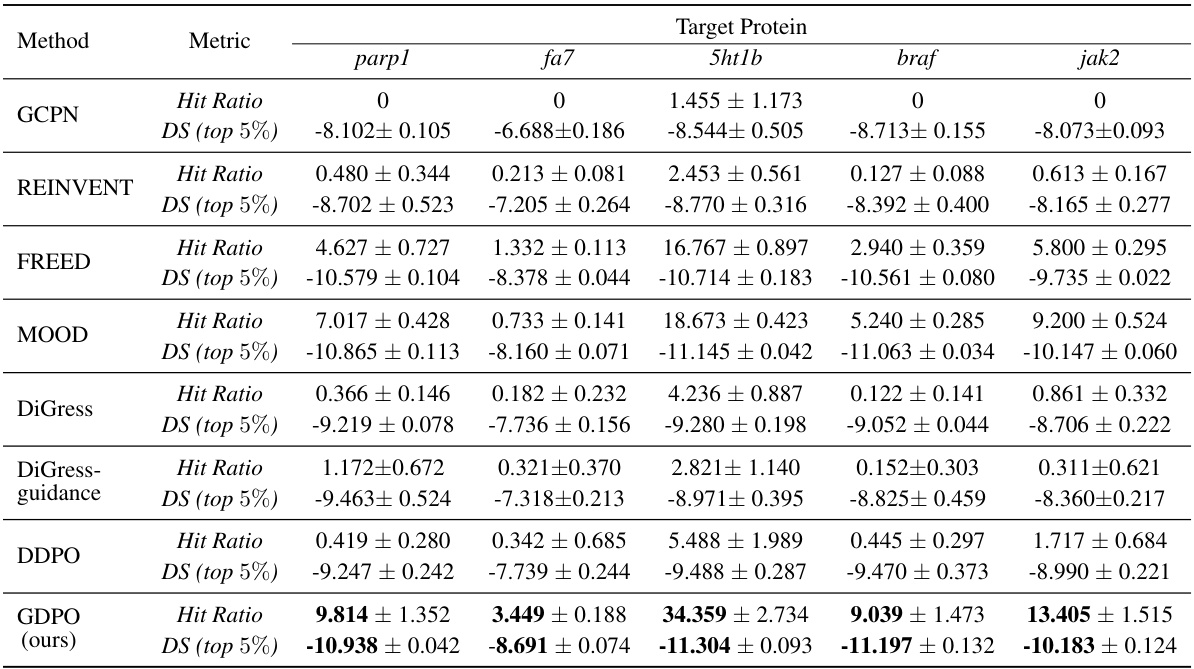

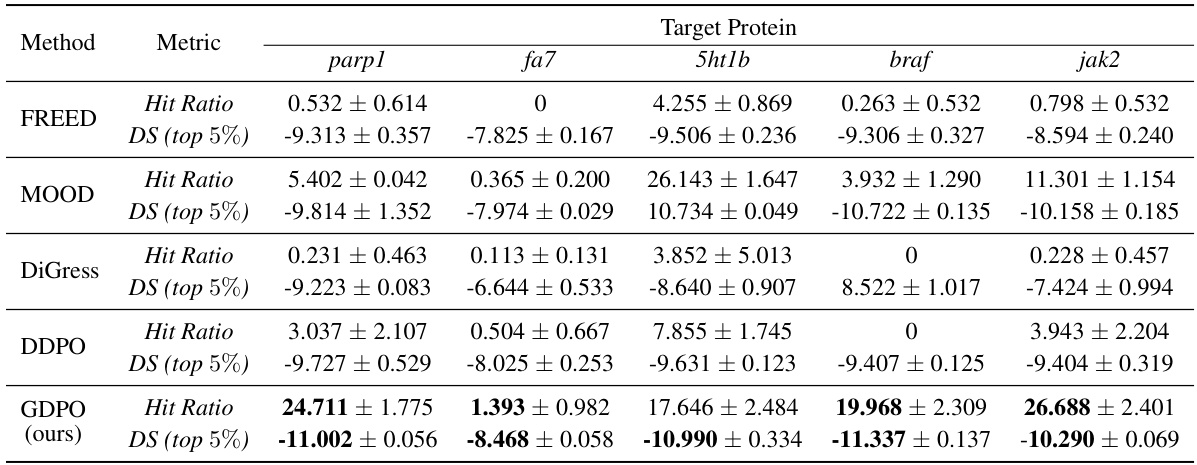

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of molecule property optimization on the ZINC250k dataset. Several methods, including GCPN, REINVENT, FREED, MOOD, DiGress, DiGress with guidance, DDPO, and GDPO (the proposed method), are compared based on two metrics: Hit Ratio and DS (top 5%). The Hit Ratio indicates the proportion of unique generated molecules satisfying specific criteria (docking score, novelty, drug-likeness, and synthetic accessibility), while DS (top 5%) represents the average docking score of the top 5% of molecules based on these criteria. Results are shown for five different target proteins (parp1, fa7, 5ht1b, braf, and jak2). GDPO shows improvement over other methods in most cases.

read the caption

Table 2: Molecule property optimization results on ZINC250k.

🔼 This table presents the results of molecule property optimization experiments conducted on the ZINC250k dataset. Several methods, including GCPN, REINVENT, FREED, MOOD, DiGress, DDPO, and the proposed GDPO, are compared based on their performance in achieving specific target protein objectives. The metrics used for comparison are Hit Ratio and the top 5% docking scores (DS). The Hit Ratio represents the percentage of generated molecules meeting specific criteria of novelty, drug-likeness, and synthetic accessibility, while the DS (top 5%) metric reflects the average docking score of the top 5% of molecules based on these same criteria.

read the caption

Table 2: Molecule property optimization results on ZINC250k.

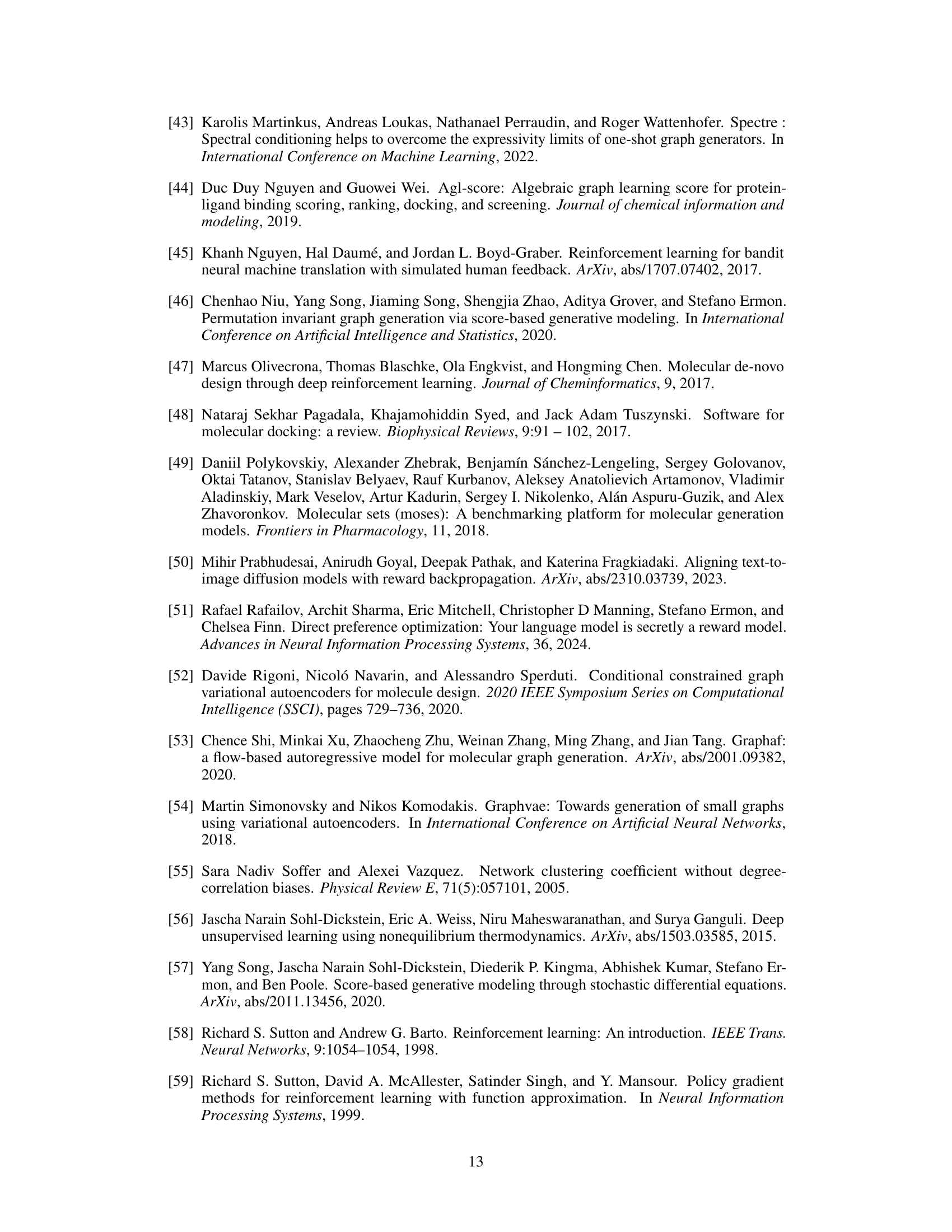

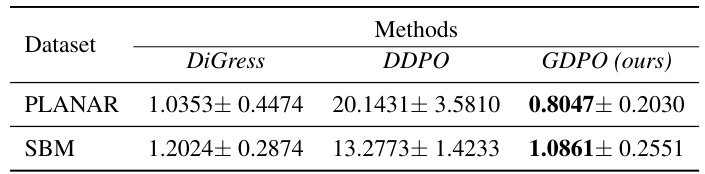

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating the generalizability of the GDPO model by assessing its performance on the Spectral MMD metric, a measure not directly included in the reward signal used during training. The results, for both the PLANAR and SBM datasets, compare the performance of DiGress, DDPO (a baseline method), and GDPO. Lower values indicate better performance. GDPO shows better generalization capabilities than the other methods.

read the caption

Table 4: Generalizability of GDPO on Spectral MMD.

🔼 This table presents the results of general graph generation experiments on two benchmark datasets: SBM and Planar. Several different methods are compared, including GraphRNN, SPECTRE, GDSS, MOOD, and DiGress, as well as the proposed GDPO method and its variant DDPO. The results are evaluated using four key metrics: Deg, Clus, Orb, and V.U.N. Deg, Clus, and Orb measure the discrepancy between the generated graphs’ degree, clustering coefficient, and orbit distributions compared to the test set. V.U.N measures the proportion of generated graphs that are valid, unique, and novel. Lower values for Deg, Clus, and Orb indicate better performance, while a higher value for V.U.N signifies better results. The table demonstrates the superior performance of GDPO across both datasets compared to other baselines.

read the caption

Table 1: General graph generation on SBM and Planar datasets.

🔼 This table presents the results of molecule property optimization on the ZINC250k dataset. It compares the performance of GDPO against several leading methods across five different target proteins (parp1, fa7, 5ht1b, braf, and jak2). The metrics used for evaluation are Hit Ratio (the proportion of generated molecules meeting specific criteria) and DS (top 5%) (the average docking score of the top 5% molecules). The table showcases the effectiveness of GDPO in optimizing for specific molecule properties.

read the caption

Table 2: Molecule property optimization results on ZINC250k.

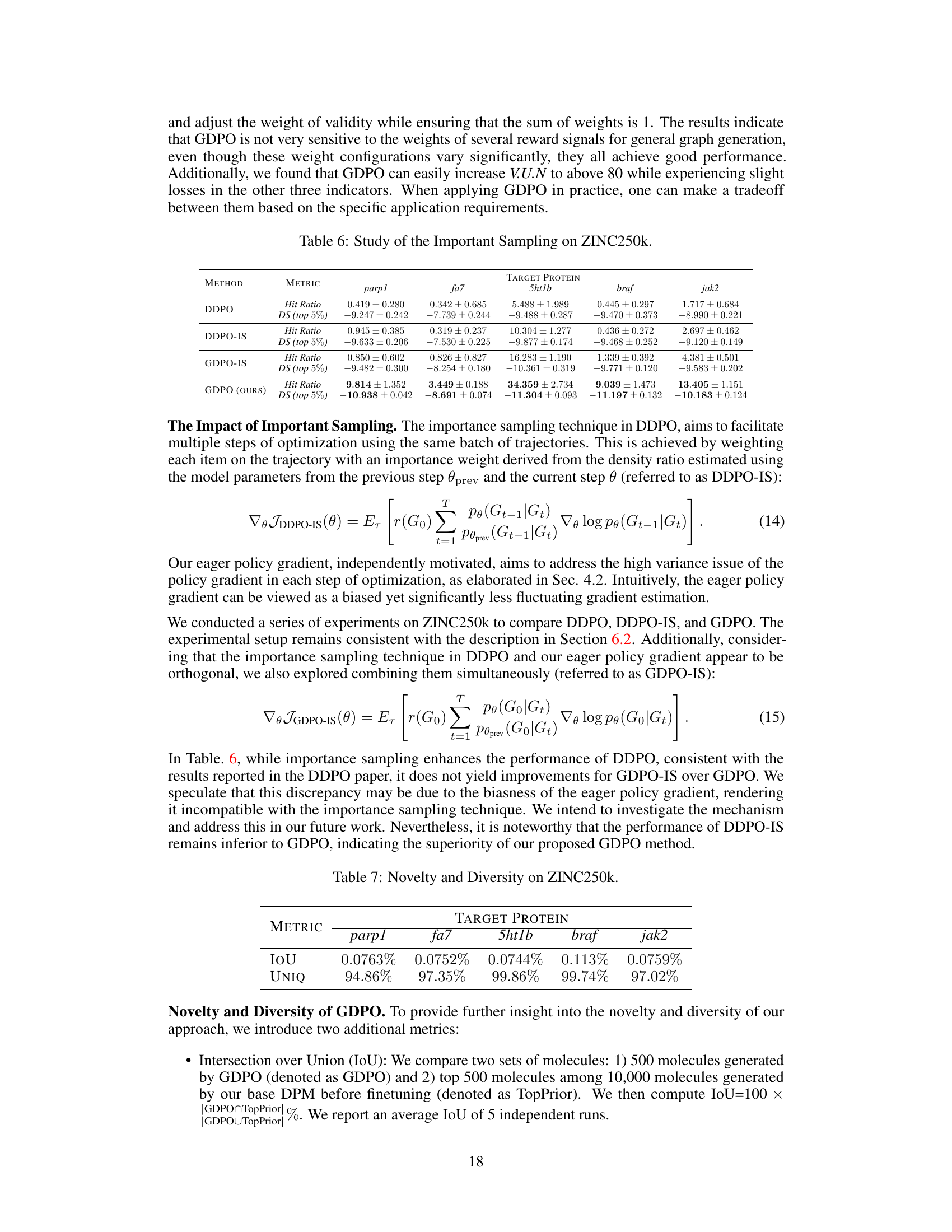

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating the novelty and diversity of molecules generated by GDPO on the ZINC250k dataset. Two metrics are used: Intersection over Union (IoU), which measures the overlap between molecules generated by GDPO and a set of top-performing molecules from a base model; and Uniqueness (UNIQ), which measures the percentage of unique molecules among a larger sample generated by GDPO. The results show that GDPO generates novel and diverse molecules, indicating that it hasn’t simply memorized or reproduced existing molecules from the training data.

read the caption

Table 7: Novelty and Diversity on ZINC250k.

Full paper#