TL;DR#

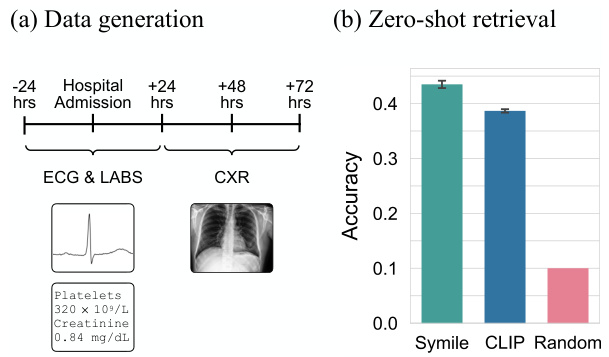

Current contrastive learning methods like CLIP struggle with data containing multiple modalities, limiting the quality of learned representations because they only capture pairwise information, ignoring higher-order relationships. This is especially problematic in complex domains like healthcare and robotics where many data types must be integrated. The pairwise application of CLIP fails to capture sufficient information between modalities.

Symile addresses this issue by capturing higher-order information between any number of modalities. It provides a flexible, architecture-agnostic objective based on a lower bound of total correlation, enabling the learning of modality-specific representations that are sufficient statistics for predicting missing modalities. Experiments show Symile outperforms pairwise CLIP in cross-modal classification and retrieval, even with missing data, across various datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces Symile, a novel contrastive learning approach that overcomes limitations of existing methods by capturing higher-order information across multiple modalities. This significantly improves representation learning in diverse fields like robotics and healthcare, where multimodal data is prevalent. Symile’s flexibility and model-agnostic nature make it broadly applicable, opening new research avenues in multimodal learning and zero-shot transfer.

Visual Insights#

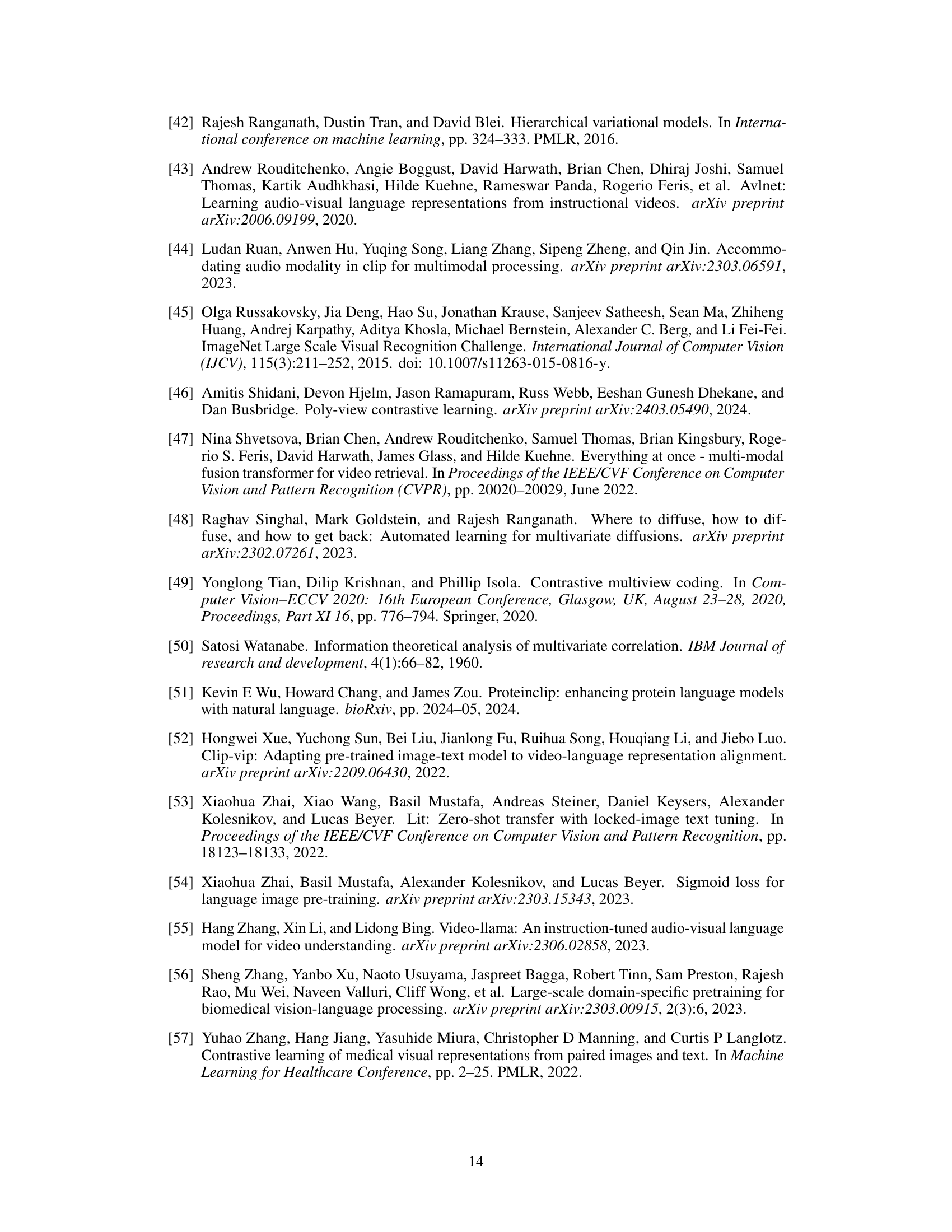

🔼 This figure illustrates the difference between how CLIP and Symile capture information from multiple modalities. CLIP, using a pairwise approach, only captures pairwise relationships between modalities (a and b, b and c, a and c). Symile, on the other hand, captures both pairwise and higher-order relationships (such as the relationship between a and b given c). The figure uses a Venn diagram analogy to represent this difference, visually showing how Symile incorporates more information compared to CLIP.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustrative comparison of the information captured by CLIP (only pairwise) and Symile (both pairwise and higher-order).

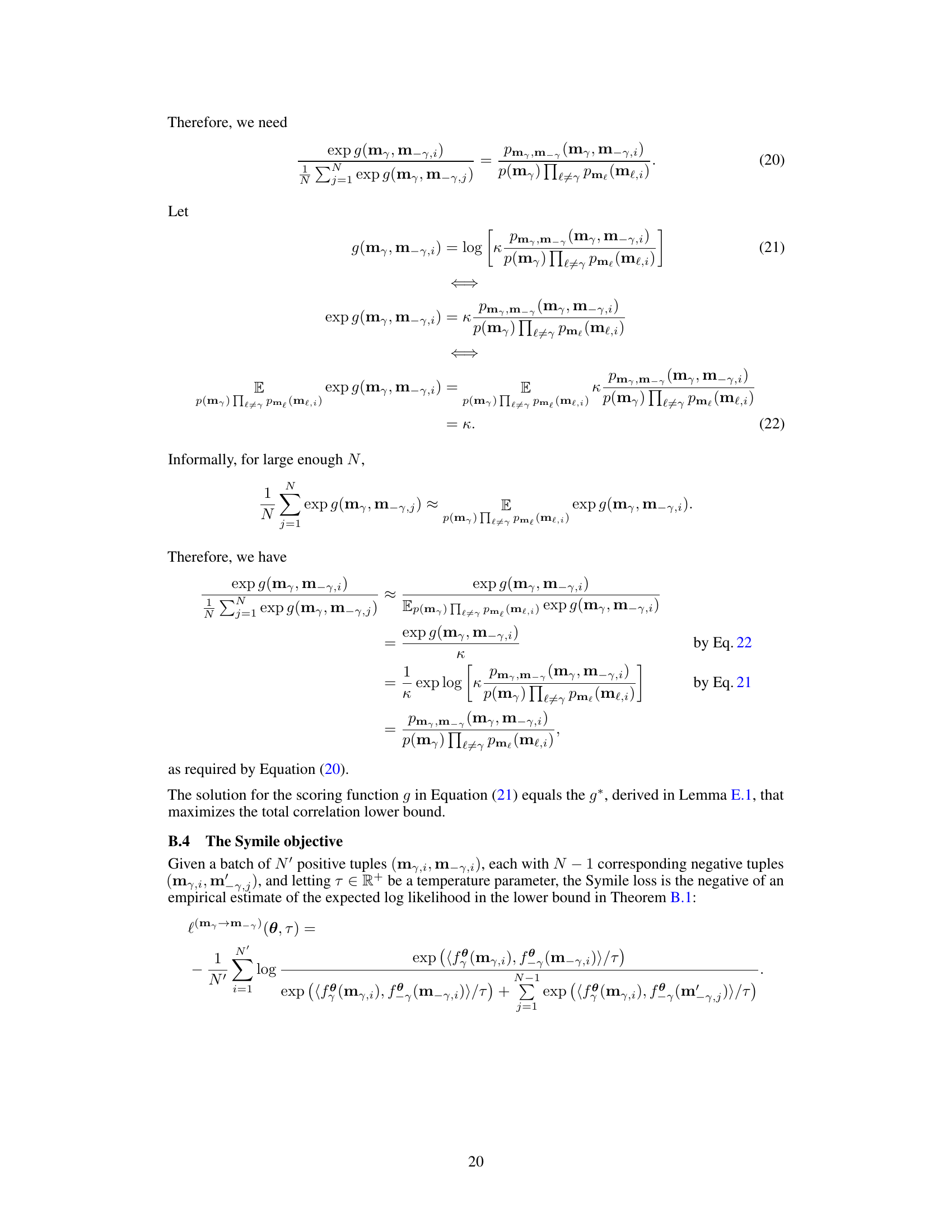

🔼 This table shows a joint probability distribution for two variables, y (disease) and t (temperature). The probabilities are shown for different combinations of disease (a or b) and temperature (99, 100, 101, or 102). The marginal probabilities for each variable are also shown.

read the caption

Table 1: The values these two variables can take are outlined in the following joint distribution table.

In-depth insights#

Symile’s Novelty#

Symile’s novelty lies in its simple yet effective approach to contrastive learning for multiple modalities. Unlike existing methods that treat modalities pairwise, potentially missing crucial higher-order relationships, Symile directly targets total correlation, a measure capturing all interdependencies. This architecture-agnostic objective is derived from a lower bound on total correlation, ensuring the learned representations are sufficient statistics for predicting any modality given others. Furthermore, Symile handles missing data gracefully unlike pairwise approaches, preserving its performance advantage even with incomplete observations. Its efficiency is also enhanced through the adoption of efficient negative sampling techniques. These combined innovations represent a significant advancement in multimodal representation learning, providing a more comprehensive and robust solution than previous pairwise methods.

Multimodal Contrast#

Multimodal contrast, in the context of machine learning, focuses on learning effective representations from diverse data types. The core idea is to leverage the relationships between different modalities (e.g., image, text, audio) to improve the quality of learned features. This contrasts with unimodal approaches that process each data type in isolation. A key challenge lies in effectively capturing the inter-modal dependencies, as different modalities often have vastly different structures and characteristics. Successful multimodal contrast techniques often involve contrastive learning, maximizing similarity between paired representations from different modalities that share semantic meaning, and minimizing similarity between those that don’t. This requires careful design of loss functions, data augmentation strategies, and encoder architectures tailored to each modality. Effective multimodal contrast often outperforms unimodal approaches on downstream tasks such as cross-modal retrieval and classification. It also presents opportunities for zero-shot learning and generalization to unseen data, making it a powerful technique for building robust and versatile AI systems.

Empirical Findings#

An Empirical Findings section would delve into the experimental results, presenting quantitative evidence supporting the paper’s claims. It would likely include detailed descriptions of datasets used, methodologies employed (including model architectures and training parameters), and a comparison of the proposed method’s performance against existing state-of-the-art approaches. Key metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score would be reported, along with statistical significance tests to assess the reliability of the observed differences. The discussion would analyze the results’ implications, highlighting both successes and limitations. Visualizations (charts and tables) would be crucial for clearly presenting the data and facilitating comprehension. For example, the visualization of accuracy scores across different modalities and datasets would provide key insights into the robustness and generalizability of the model. Furthermore, the results for tasks such as cross-modal retrieval or classification would be thoroughly analyzed to demonstrate the effectiveness of capturing higher-order information. The section should conclude with a synthesis of the findings, emphasizing the extent to which the empirical evidence supports or refutes the paper’s hypotheses. Attention should be paid to clearly explaining any unexpected outcomes and potential reasons for variations in performance across different experimental settings.

Missing Modality#

The concept of handling ‘missing modalities’ is crucial in multimodal learning. The paper investigates how well a model can generalize when some data types are absent during training. This is vital for real-world applications where complete data is rarely available. Symile’s strength lies in its ability to learn sufficient statistics; even with missing modalities, the model retains much of its predictive power because it captures higher-order information, not just pairwise relationships. This contrasts with pairwise CLIP, which suffers significantly when data is incomplete. The empirical results show Symile outperforming pairwise CLIP even when many modalities are missing, demonstrating its robustness. This suggests that Symile’s architecture-agnostic approach and focus on total correlation makes it more adaptive and reliable for various real-world scenarios with incomplete or inconsistent data. This robustness makes Symile a promising method for applications involving heterogeneous data sources where data might be missing or noisy.

Future Extensions#

The paper’s core contribution is Symile, a novel contrastive learning method. Future extensions could significantly broaden its impact. One avenue is exploring its synergy with larger language models (LLMs) by integrating Symile representations. This integration could enhance LLMs’ ability to understand multimodal data and improve their performance in tasks requiring cross-modal understanding. Another direction involves refining the negative sampling strategy. While O(N) and O(N^2) strategies are discussed, exploring more sophisticated sampling approaches, perhaps using techniques like noise contrastive estimation or curriculum learning, could enhance efficiency and performance. Additionally, applying Symile to more diverse datasets and modalities would showcase its versatility. Research on its performance across various data types—medical imaging, sensor data from robotics, etc.—would be valuable. Finally, investigating Symile’s theoretical properties more deeply, particularly concerning its sample efficiency and the tightness of its lower bound on total correlation, could provide crucial insights and potentially lead to further improvements in the algorithm.

More visual insights#

More on figures

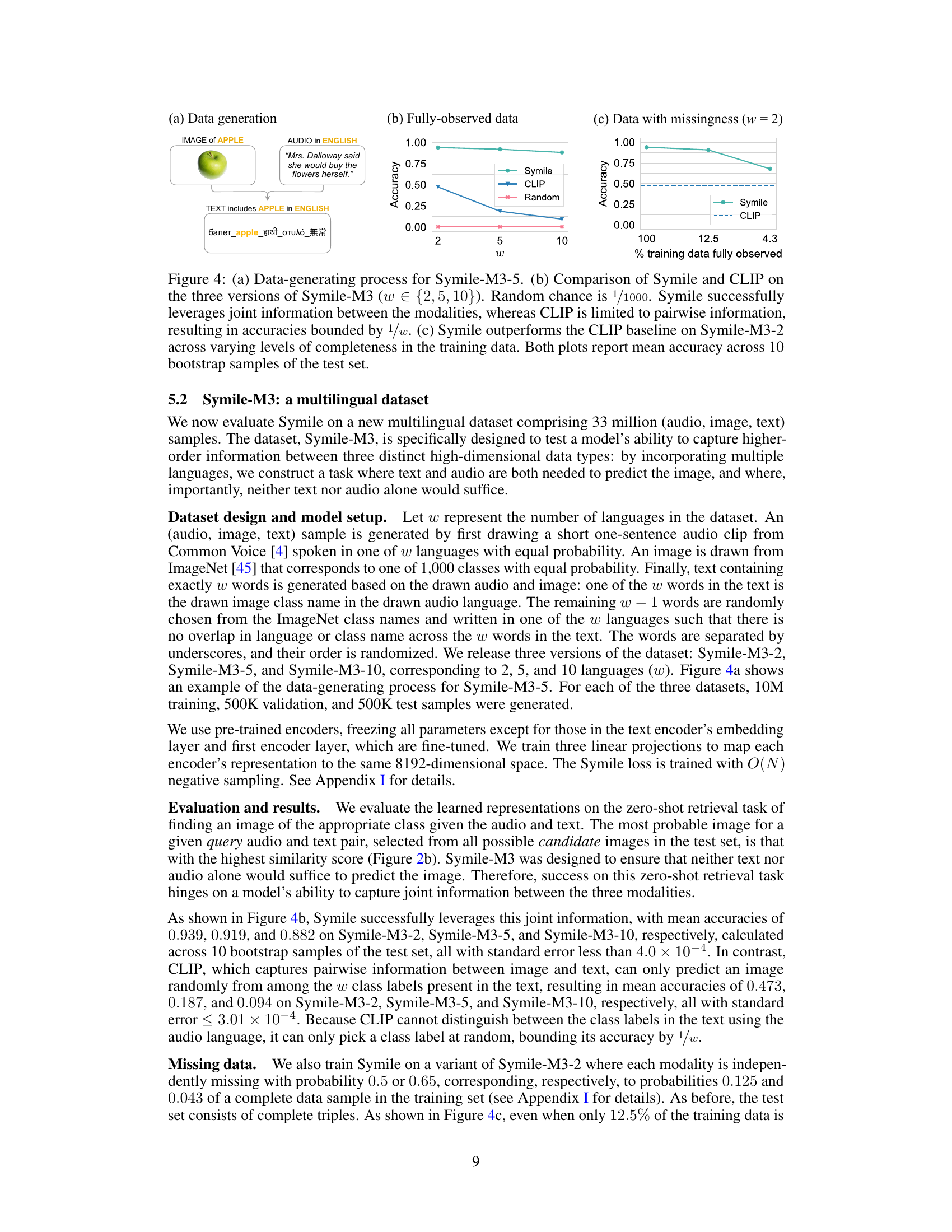

🔼 This figure illustrates the Symile model’s pre-training and zero-shot prediction processes. (a) shows the pre-training stage where Symile learns representations by maximizing the similarity between the positive triples (audio, image, text in the same language) and minimizing the similarity between negative triples. The positive triples are highlighted in yellow along the cube’s diagonal. (b) shows the zero-shot prediction process where, given a query (audio and text), the model retrieves the most similar image from a set of candidates.

read the caption

Figure 2: Symile pre-training and zero-shot prediction on the Symile-M3 multilingual dataset. (a) Given a batch of triples, Symile maximizes the multilinear inner product (MIP) of positive triples (in yellow along the diagonal of the cube) and minimizes the MIP of negative triples. (b) The model selects the candidate image with the highest similarity to the query audio and text.

🔼 This figure illustrates the Symile model’s architecture and workflow. Panel (a) shows the pre-training process, where Symile learns to maximize the multilinear inner product (MIP) of correctly paired (positive) samples across three modalities (image, text, audio) and minimize the MIP of incorrectly paired (negative) samples. The positive samples are represented in yellow along the diagonal of the cube. Panel (b) demonstrates zero-shot prediction, where the model predicts a modality (image in this case) based on two other modalities (audio and text).

read the caption

Figure 2: Symile pre-training and zero-shot prediction on the Symile-M3 multilingual dataset. (a) Given a batch of triples, Symile maximizes the multilinear inner product (MIP) of positive triples (in yellow along the diagonal of the cube) and minimizes the MIP of negative triples. (b) The model selects the candidate image with the highest similarity to the query audio and text.

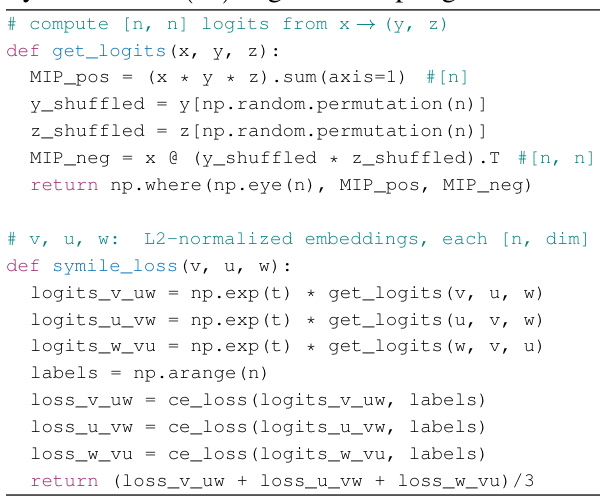

🔼 This figure demonstrates the performance difference between Symile and CLIP in a controlled setting with binary synthetic data. The left panel shows that Symile’s accuracy increases as the parameter ‘p’ increases, reaching perfect accuracy at p=1, unlike CLIP, which performs no better than random chance. The right panel explains this difference by plotting the mutual information between the variables. As ‘p’ increases, the higher-order conditional mutual information (I(a; b | c) = I(b; c | a)) also increases, which Symile leverages. Conversely, the pairwise mutual information remains zero for all values of ‘p’, which explains CLIP’s poor performance.

read the caption

Figure 3: The performance gap between Symile and CLIP on binary synthetic data (left) is a consequence of the changing information dynamics between the variables as p moves from 0 to 1 (right). Mean accuracy is reported across 10 bootstrap samples of the test set.

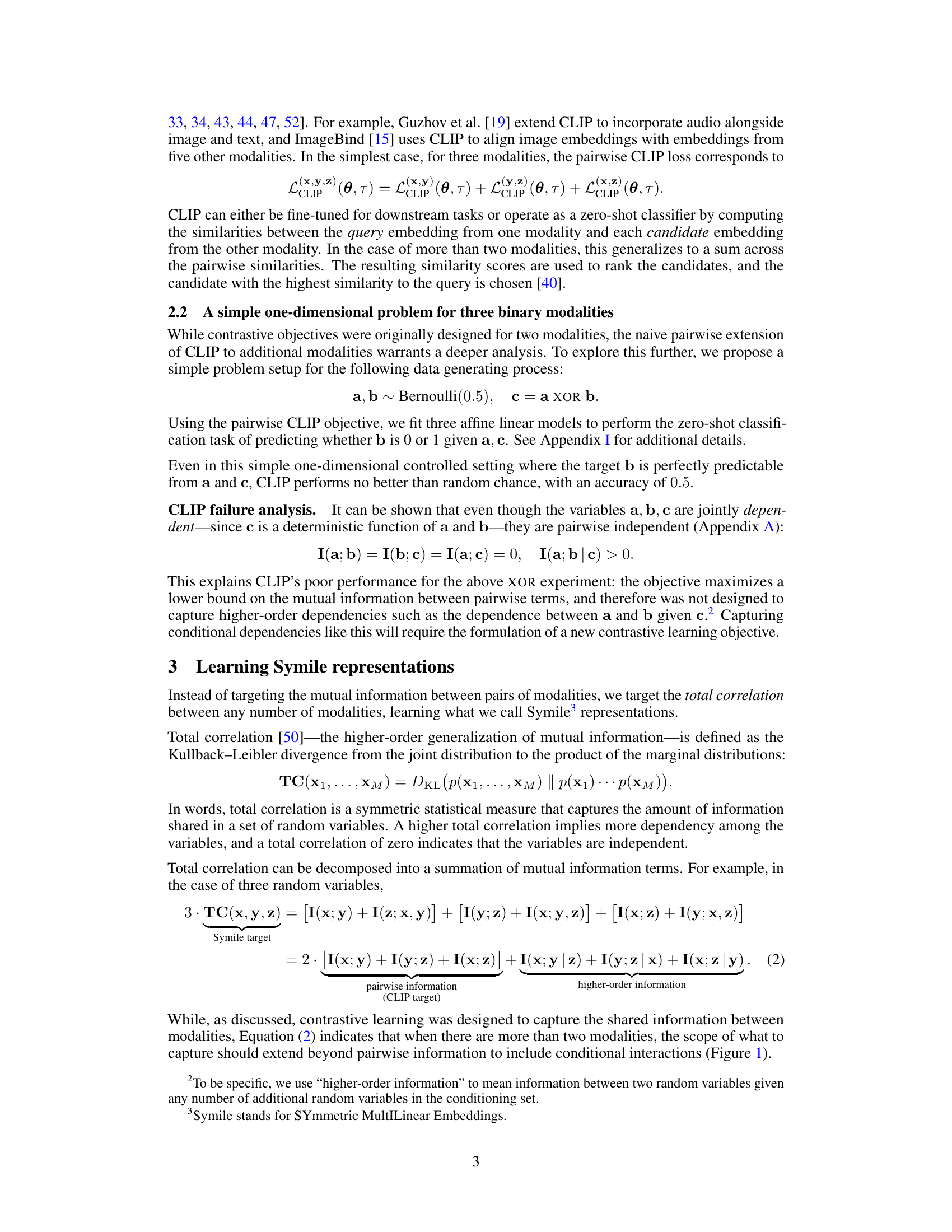

🔼 This figure shows the performance of Symile and CLIP on the Symile-M3 multilingual dataset under different conditions. (a) illustrates the data generation process. (b) compares the accuracy of Symile and CLIP on three versions of Symile-M3 with varying numbers of languages (w), showing Symile’s superior ability to leverage joint information between modalities. (c) demonstrates Symile’s robustness to missing data in the training dataset, consistently outperforming CLIP even with limited data.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) Data-generating process for Symile-M3-5. (b) Comparison of Symile and CLIP on the three versions of Symile-M3 (w ∈ {2,5,10}). Random chance is 1/1000. Symile successfully leverages joint information between the modalities, whereas CLIP is limited to pairwise information, resulting in accuracies bounded by 1/w. (c) Symile outperforms the CLIP baseline on Symile-M3-2 across varying levels of completeness in the training data. Both plots report mean accuracy across 10 bootstrap samples of the test set.

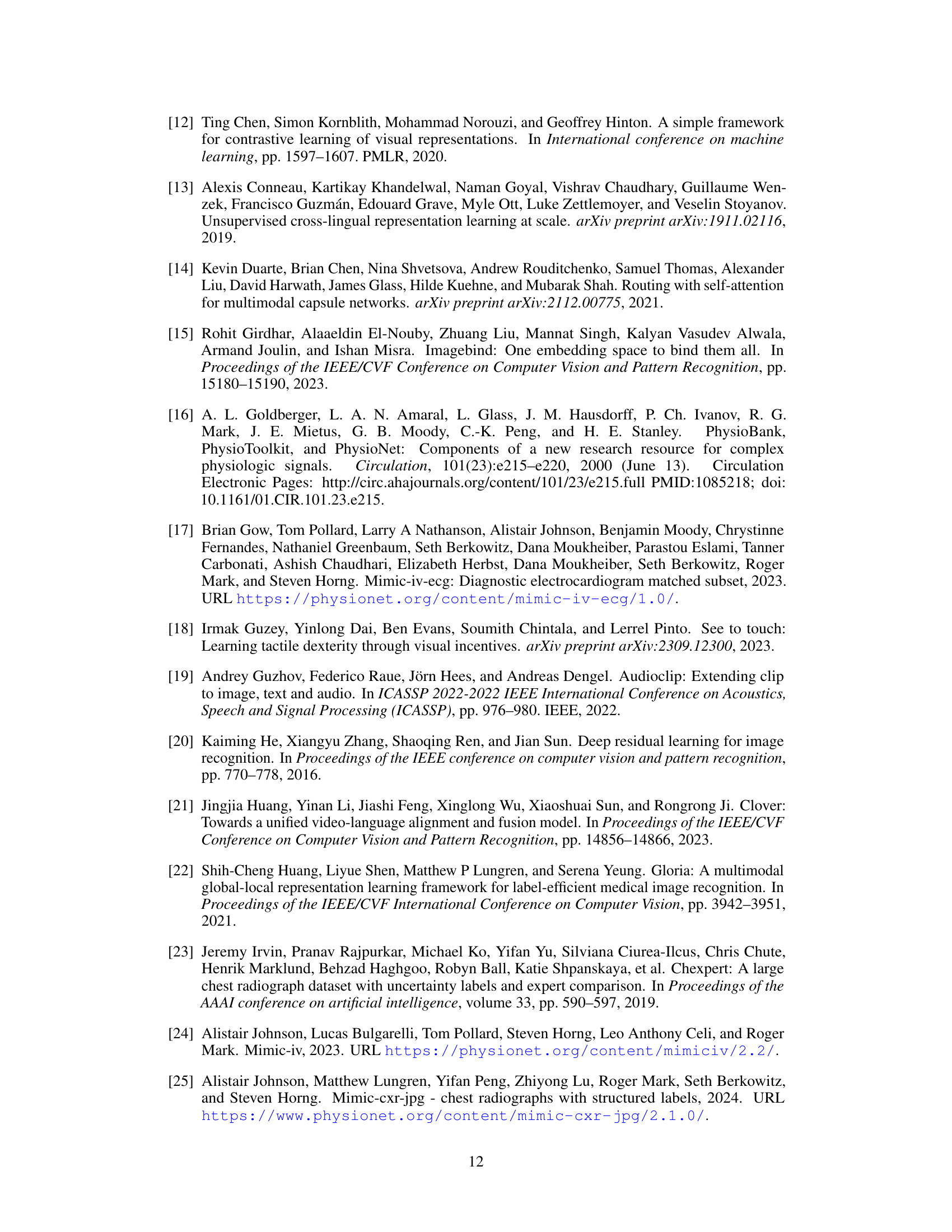

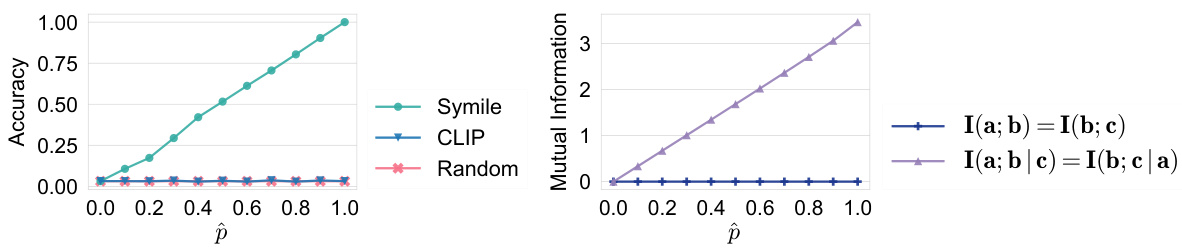

🔼 This figure shows the data generation process for the Symile-MIMIC dataset and the zero-shot retrieval results. The dataset consists of ECGs, blood labs, and chest X-rays (CXR) taken from patients within a specific timeframe around hospital admission. The results show Symile outperforming pairwise CLIP in accurately identifying the correct CXR given the ECG and lab data, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method in this clinical context.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a) Each sample of Symile-MIMIC includes an ECG and blood labs taken within 24 hours of the patient's admission to the hospital, and a CXR taken in the 24- to 72-hour period post-admission. (b) Retrieval accuracy for identifying the CXR corresponding to a given ECG and labs pair. Results are averaged over 10 bootstrap samples, with error bars indicating standard error.

Full paper#