TL;DR#

Current latent video models often rely on computationally expensive training, hampered by latent space incompatibility between image and video VAEs. This results in low-quality videos, especially concerning temporal smoothness. The uniform frame sampling used for temporal compression further exacerbates this issue.

The paper introduces CV-VAE, a new video VAE addressing these challenges. CV-VAE achieves compatibility with existing image VAEs by utilizing a novel latent space regularization technique. It incorporates an efficient architecture that enhances training speed and reconstruction quality. Experiments demonstrate that CV-VAE allows video generation models to produce four times more frames compared to existing models, with minimal additional training.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in video generation due to its introduction of CV-VAE, a novel video VAE compatible with existing image VAEs. This compatibility significantly reduces the computational cost and training time associated with latent video models. The proposed latent space regularization and efficient architecture further enhance the model’s efficiency and effectiveness, opening new avenues for developing high-quality, temporally consistent video generation models. The results demonstrate improved video reconstruction and compatibility with state-of-the-art models, providing a valuable resource for the research community.

Visual Insights#

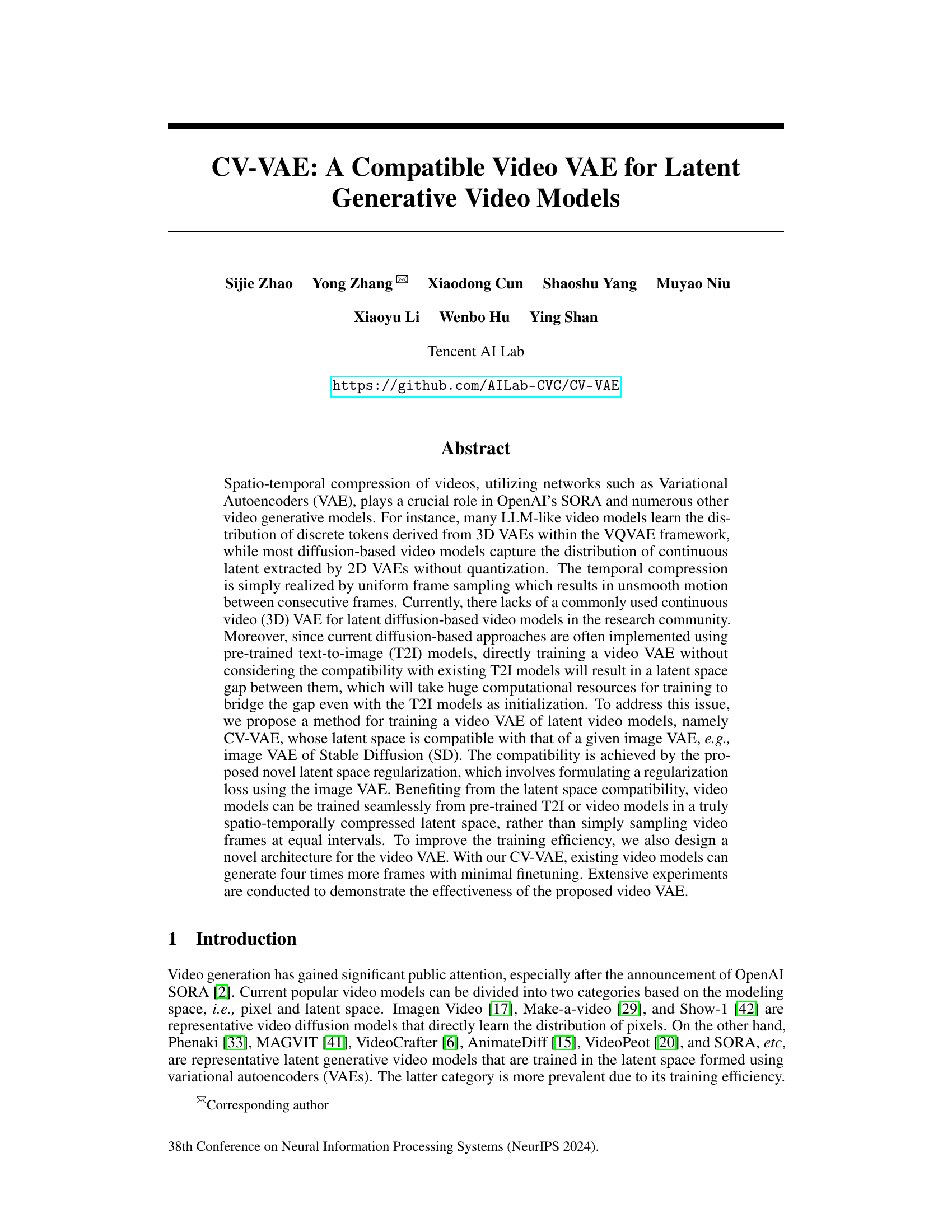

🔼 This figure compares two different methods of temporal compression in video processing. (a) shows the traditional method of uniform frame sampling, where frames are selected at equal intervals, resulting in jerky or uneven motion between frames. (b) demonstrates the proposed method using 3D convolutions for temporal compression, where the model processes the video data in its entirety, better capturing motion and temporal relationships between frames resulting in a smoother video.

read the caption

Figure 1: Temporal compression difference between an image VAE and our video one.

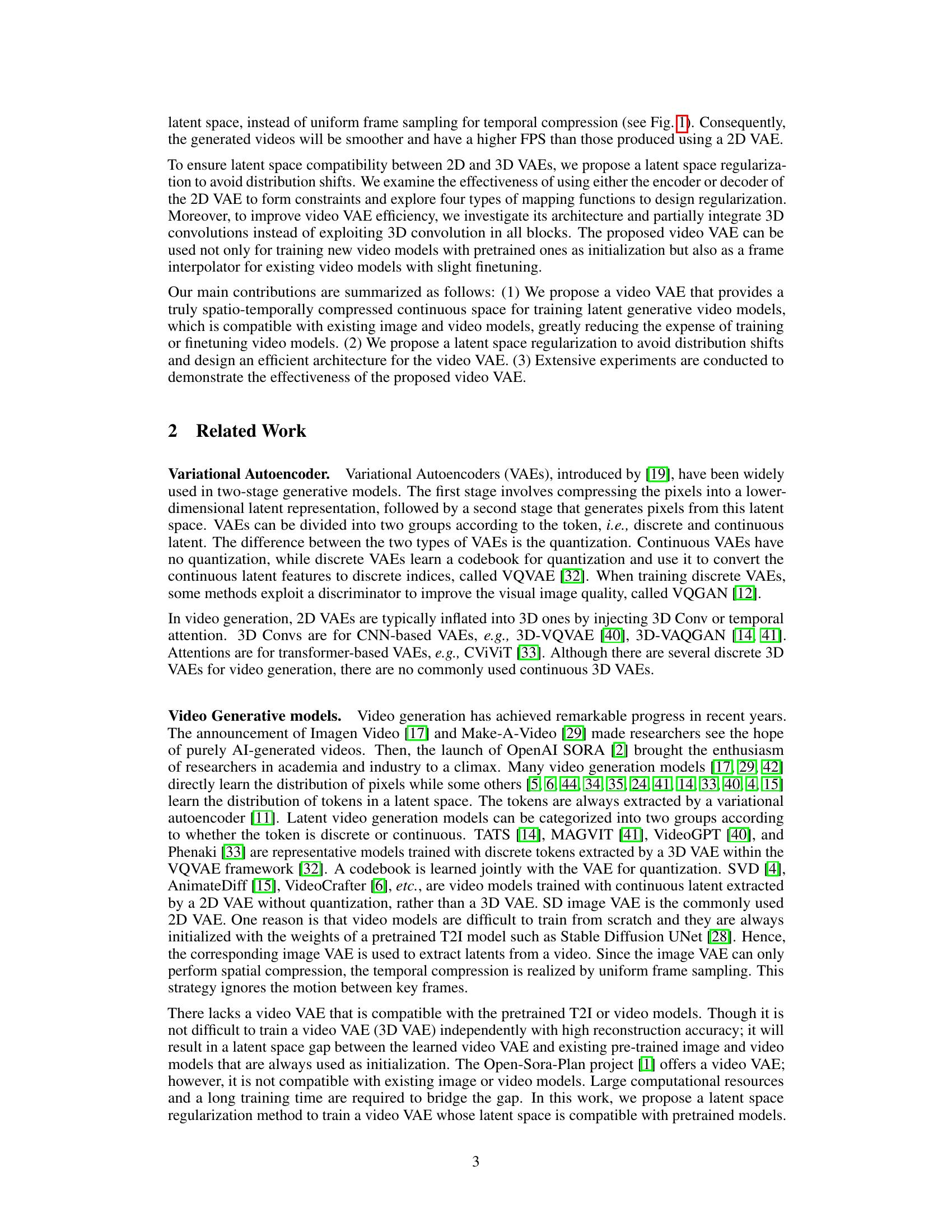

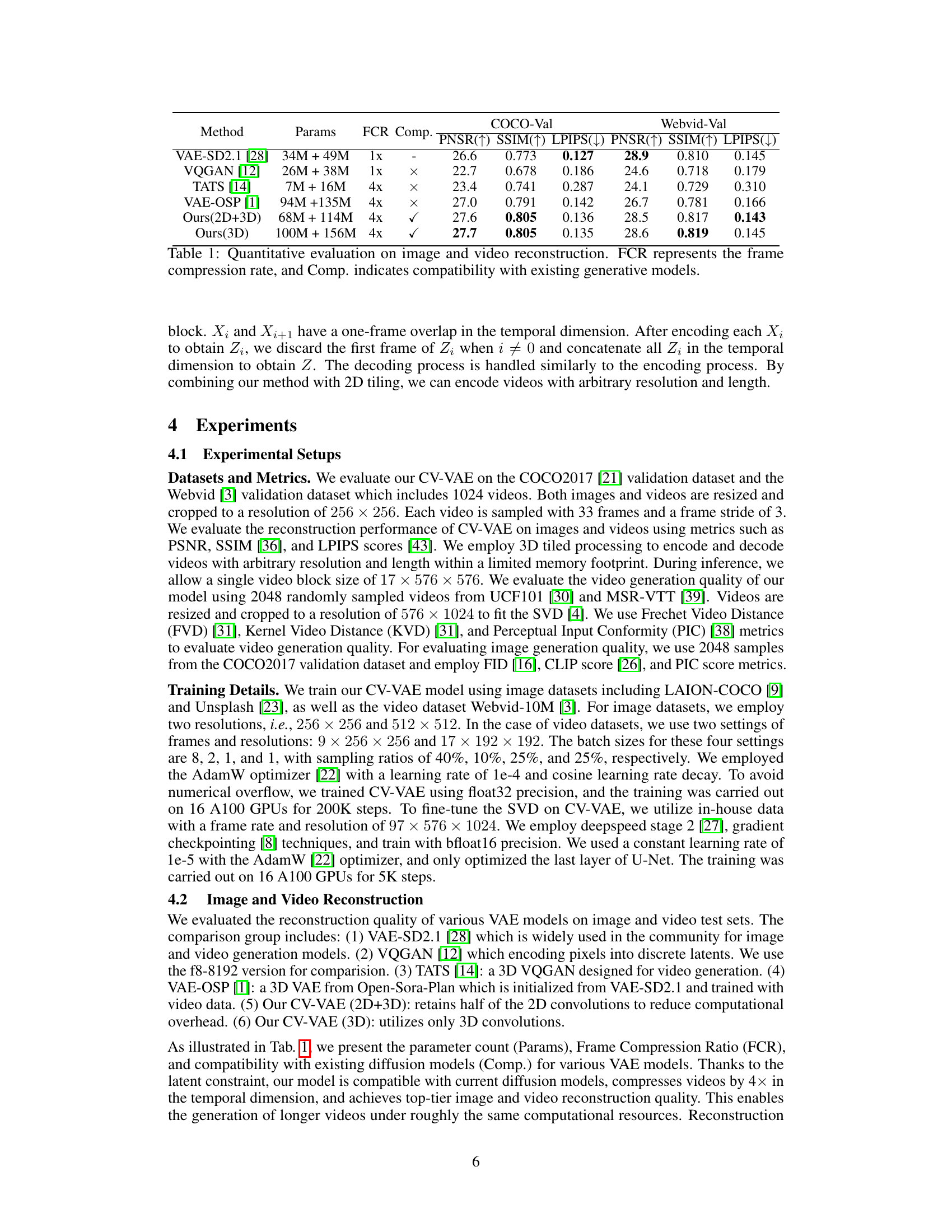

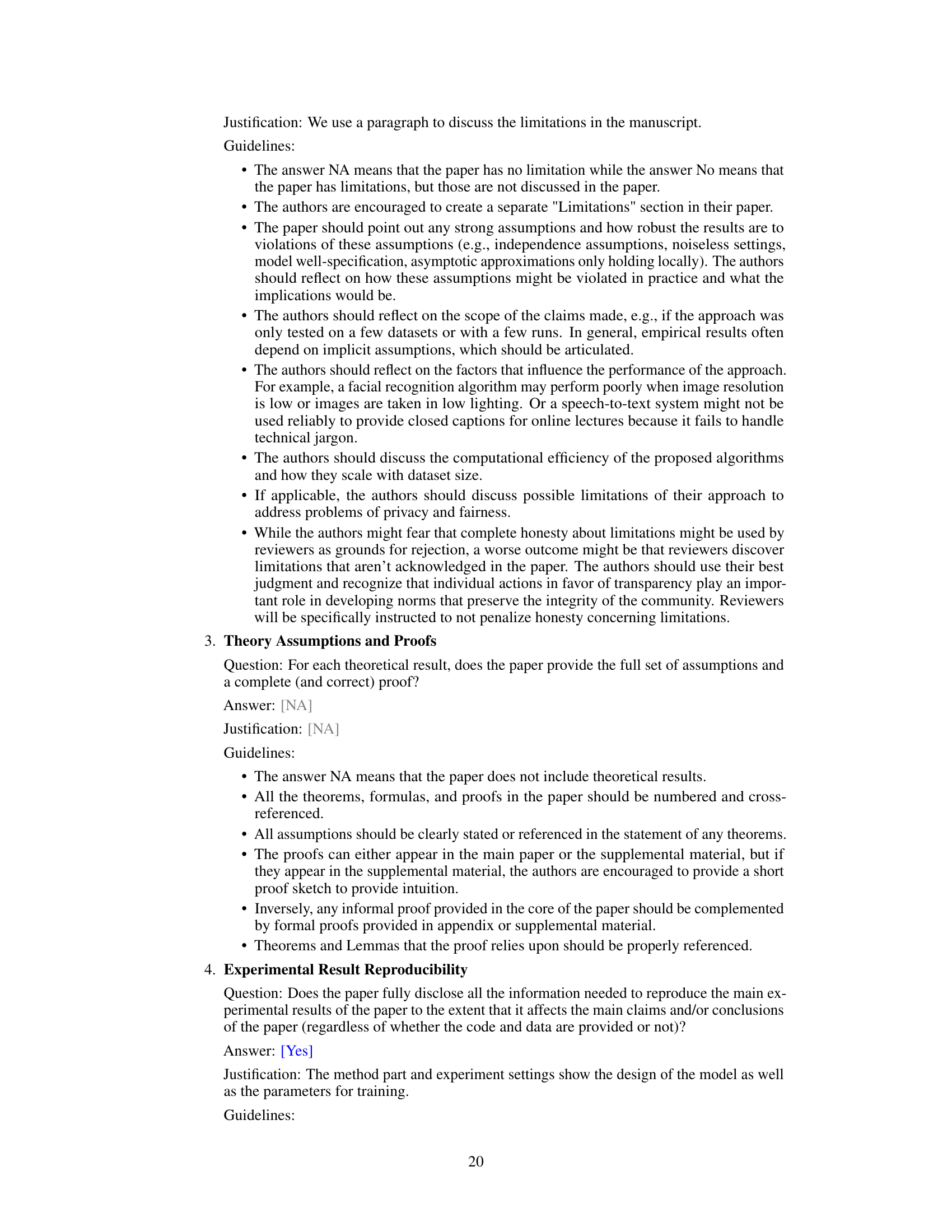

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different Variational Autoencoder (VAE) models for image and video reconstruction. The models are evaluated using Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS), and Frame Compression Rate (FCR). The ‘Comp.’ column indicates whether each model is compatible with existing generative models. The table shows that the proposed CV-VAE models achieve comparable or better performance than other VAEs, especially in video reconstruction, while maintaining compatibility with existing models.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluation on image and video reconstruction. FCR represents the frame compression rate, and Comp. indicates compatibility with existing generative models.

In-depth insights#

Latent Space Harmony#

The concept of “Latent Space Harmony” in a video generation model refers to the alignment and compatibility of latent spaces between different components of the system, particularly between a pre-trained image VAE and a newly trained video VAE. Achieving this harmony is crucial for effective and efficient training. Without it, the video model would struggle to leverage the pre-trained knowledge, requiring extensive retraining and potentially leading to sub-optimal results. Methods to achieve latent space harmony might involve regularization techniques that encourage the latent representations from both VAEs to exhibit similar statistical properties or use architectural designs that explicitly bridge the latent spaces. Successful latent space harmony translates to improved performance in video generation, allowing for a more seamless integration of pre-trained models and potentially requiring less computational resources for training. The resulting videos should also exhibit better quality and higher temporal consistency, owing to the smoother transfer of information between the different stages of the model. This approach is a significant factor in the efficient and effective training of advanced video generation models.

3D-VAE Architecture#

A 3D-VAE architecture would fundamentally differ from its 2D counterpart by incorporating temporal modeling capabilities. Instead of processing only spatial dimensions (width and height), a 3D-VAE would also process the temporal dimension (time/frames), allowing it to understand and represent the temporal evolution of visual information within a video. This is typically achieved using 3D convolutional layers which learn spatiotemporal features. The architecture would likely consist of an encoder that compresses the video into a lower-dimensional latent space, and a decoder that reconstructs the video from this latent representation. Designing the network architecture involves critical choices. The number and arrangement of 3D convolutional layers would impact computational complexity and the model’s capacity to learn intricate temporal dependencies. Careful consideration must be given to the input video’s temporal resolution (frames per second) to prevent loss of crucial motion information. Furthermore, strategies to handle variable video lengths efficiently, such as temporal tiling or recurrent mechanisms, would be vital. Finally, the choice of loss function (e.g., reconstruction loss, KL divergence) is critical in optimizing the model’s performance and ensuring meaningful latent space representations.

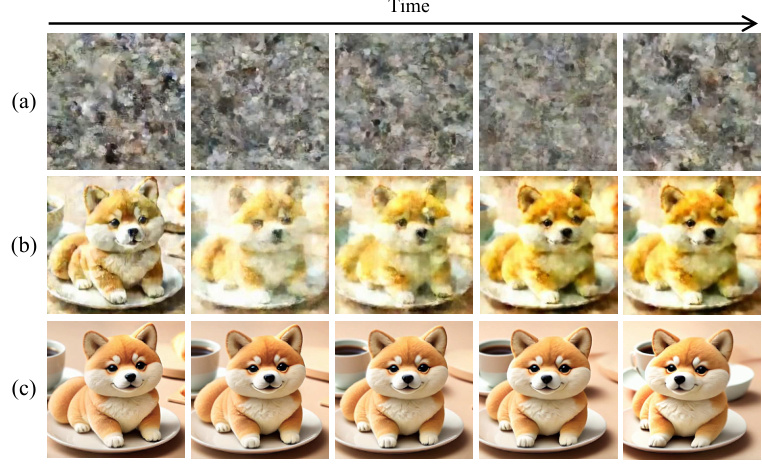

Regularization Strategies#

Regularization strategies in the context of training a video Variational Autoencoder (VAE) are crucial for ensuring latent space compatibility between the video VAE and pretrained image VAEs. The core idea is to bridge the latent space gap that would otherwise hinder seamless integration of the trained video VAE with existing models, such as those used in Stable Diffusion. The authors explore different regularization methods focusing on the encoder or decoder of the pretrained image VAE, experimenting with various mapping functions to minimize the distribution shift between the latent spaces. Key strategies involve formulating a regularization loss to constrain the latent representations. This is achieved by applying the image VAE’s encoder to the video data and using its decoder to reconstruct the video; the difference is minimized as part of the regularization. By using this regularization, the video VAE can be trained efficiently from pretrained models and produce smoother, higher-frame-rate videos. Choosing the optimal mapping function and regularization type (encoder- or decoder-based) are key to balancing reconstruction quality and latent space alignment. The exploration of these different strategies demonstrates a thoughtful approach to addressing the unique challenges of video VAE training.

Video Model Enhancements#

Enhancing video models involves multifaceted strategies. Improving temporal resolution is crucial, often tackled by techniques like frame interpolation or employing 3D convolutional architectures to directly capture spatiotemporal information. Latent space manipulation offers another avenue, with methods focusing on designing more efficient and compatible variational autoencoders (VAEs) for latent compression. This often involves regularization techniques to ensure compatibility across different models and datasets, preventing distribution shifts and improving training stability. Architectural innovations are also key, such as introducing attention mechanisms or transformers to better model long-range dependencies in video sequences, enhancing both temporal and spatial understanding. Ultimately, the success of these enhancements hinges on the trade-off between computational cost and improved video quality, calling for a careful assessment of resource usage in the context of the desired enhancement outcome. The goal remains to generate more realistic, higher-resolution, and temporally consistent videos, bridging the gap between current state-of-the-art methods and the ultimate goal of achieving photorealistic video generation.

Future Directions#

The research paper’s ‘Future Directions’ section would ideally explore several key areas. Improving the efficiency of the video VAE is crucial, perhaps through exploring more efficient architectures or training strategies. The current approach relies on latent space regularization to ensure compatibility, which introduces complexity and computational cost. Investigating alternative methods for achieving this compatibility is warranted. Another direction would involve expanding the capabilities of the video VAE to handle longer videos and higher resolutions. Currently, the architecture is restricted in its temporal handling; addressing this limitation is important for broader applications. Further exploration of the compatibility with various existing image and video models is needed, verifying that the improvements observed generalize well across different model architectures. It is also important to consider new loss functions and regularization methods to improve reconstruction quality and latent space alignment and to further enhance training efficiency. Finally, exploring diverse applications of CV-VAE beyond its initial focus on latent generative video models would demonstrate its versatility, especially in tasks like video editing, interpolation, and video restoration.

More visual insights#

More on figures

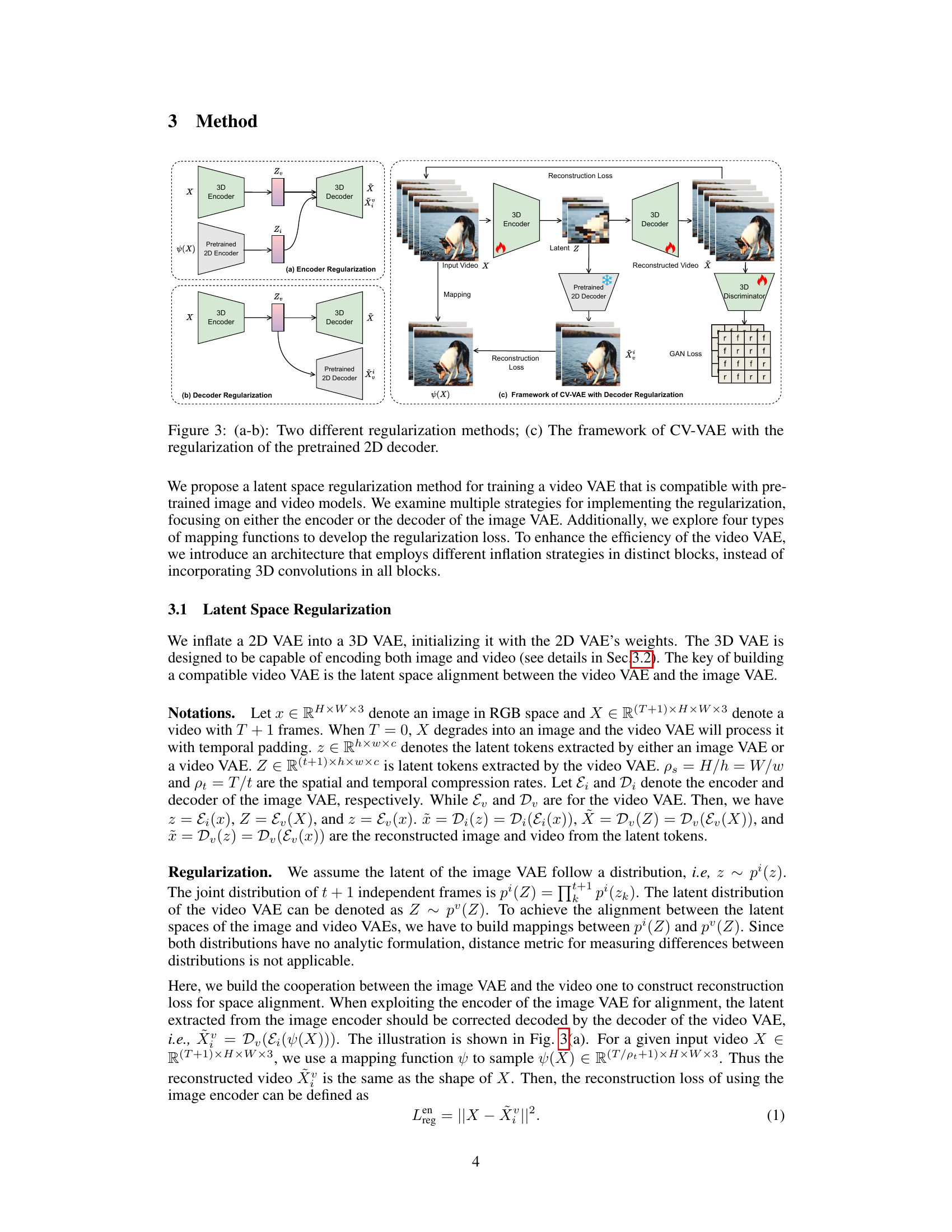

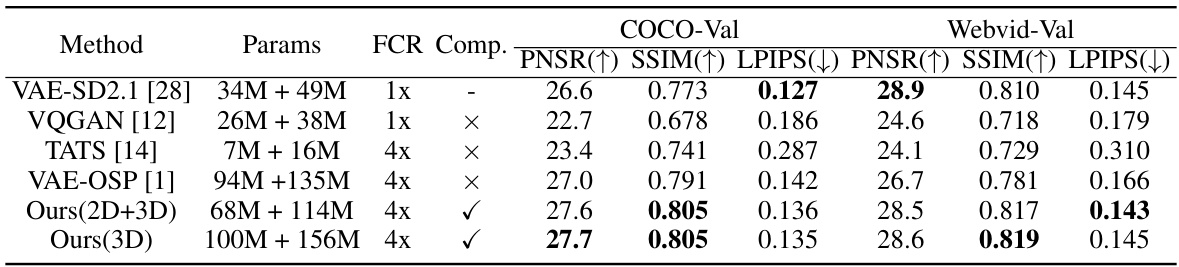

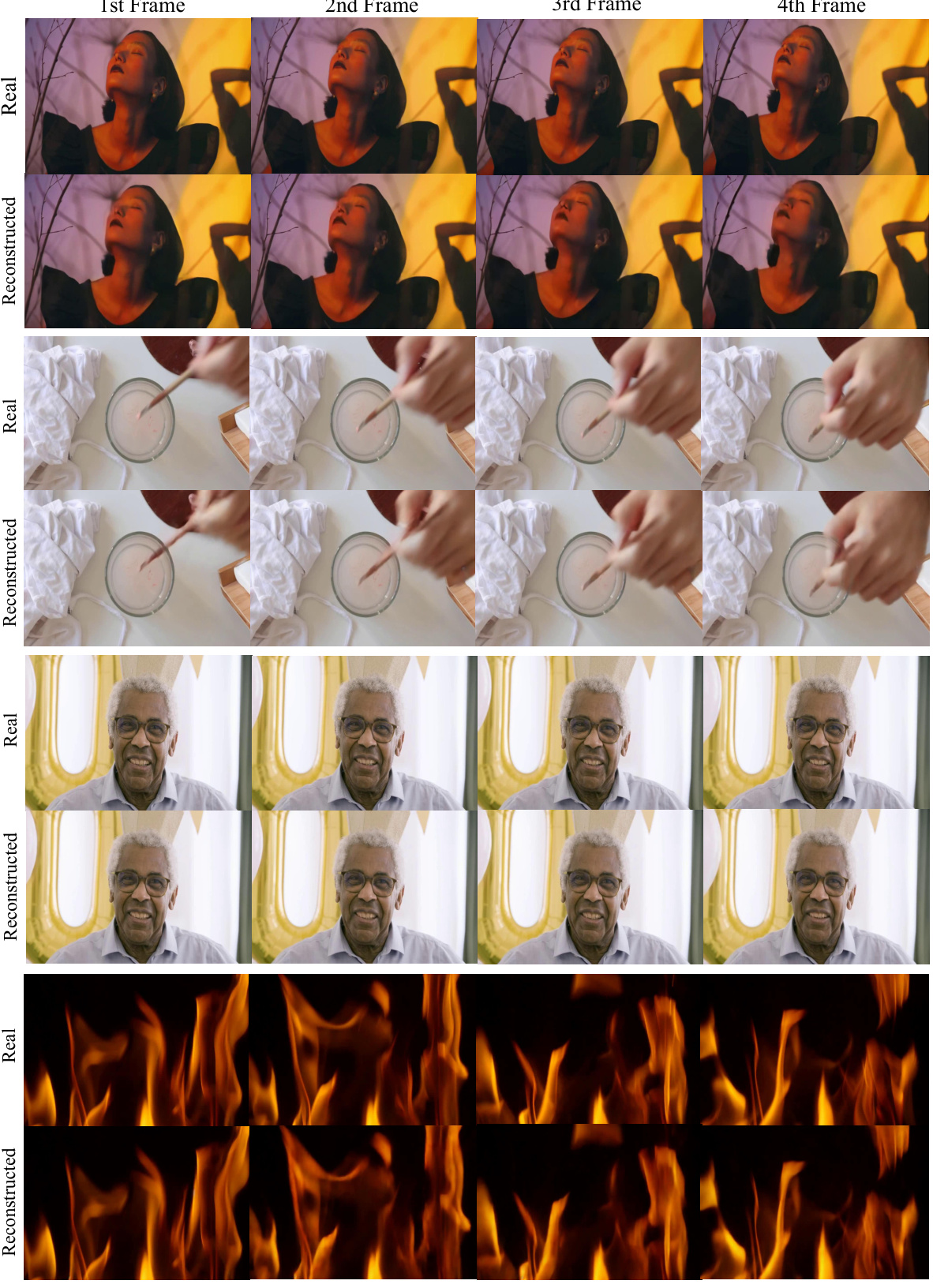

🔼 This figure shows the reconstruction results of consecutive frames from three different video clips using the proposed CV-VAE model. Each row presents a video clip, with the ‘Real’ column displaying the original frames and the ‘Reconstructed’ column showing the frames reconstructed by CV-VAE. The results demonstrate the model’s ability to reconstruct video frames with high fidelity, maintaining consistency in color, structure, and motion, even across multiple frames.

read the caption

Figure 9: Reconstruction results of consecutive frames using CV-VAE.

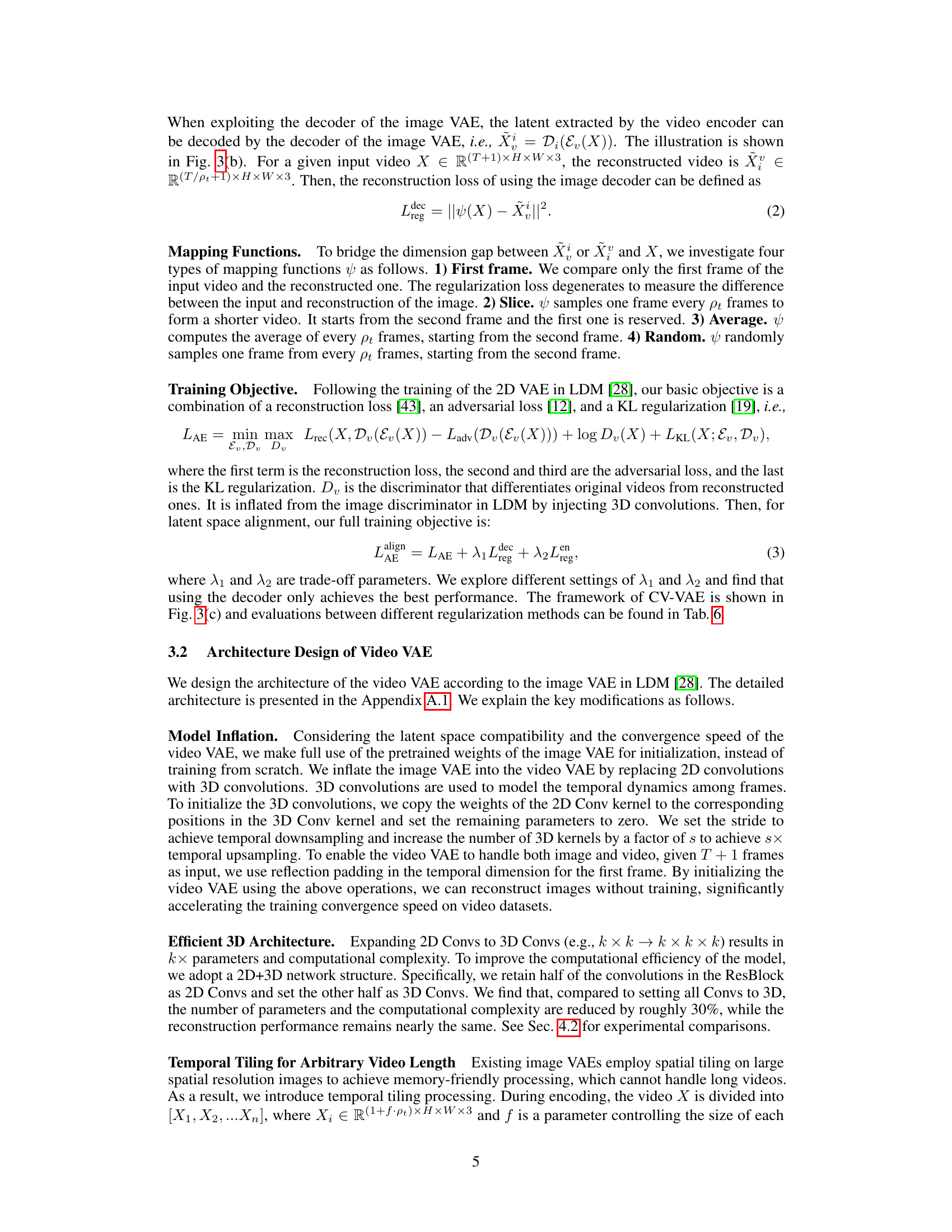

🔼 This figure illustrates two different regularization methods used in the CV-VAE model for latent space alignment between the video VAE and the image VAE. (a) shows encoder regularization where latent space from the pretrained 2D encoder is used to regularize the 3D encoder’s output. (b) shows decoder regularization where the output of the 3D decoder is passed through the pretrained 2D decoder to create a regularization loss. Finally, (c) shows the overall framework of the CV-VAE model using decoder regularization, incorporating the pretrained 2D decoder, a 3D discriminator, and a mapping function to align latents.

read the caption

Figure 3: (a-b): Two different regularization methods; (c) The framework of CV-VAE with the regularization of the pretrained 2D decoder.

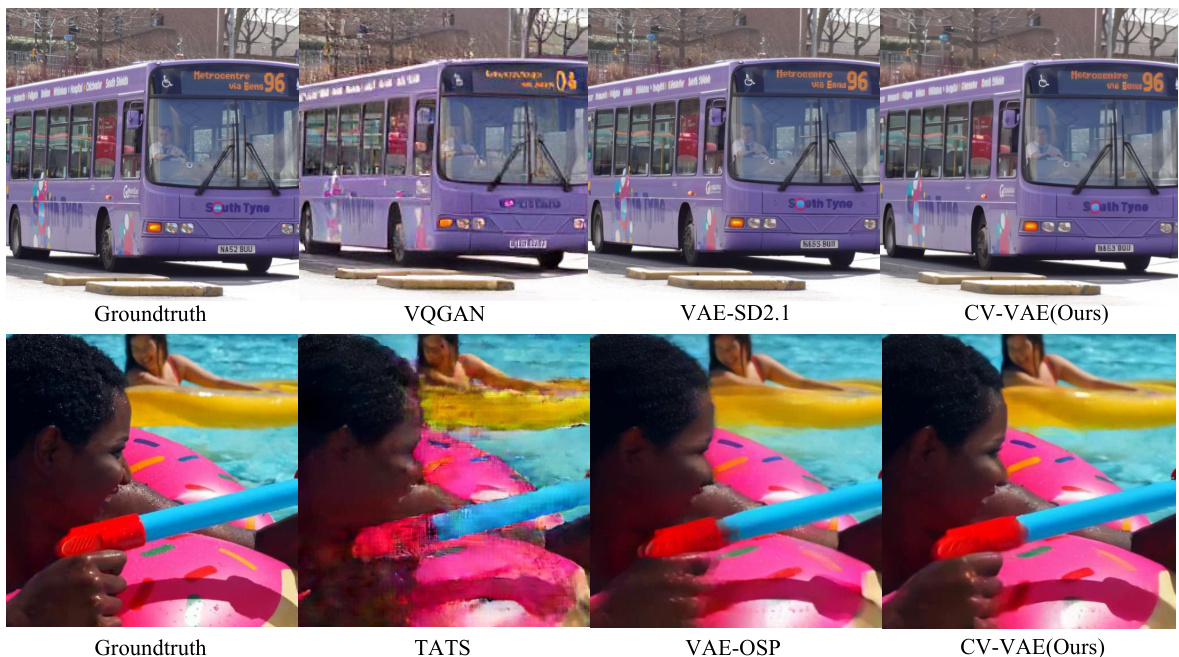

🔼 This figure compares the image and video reconstruction quality of different Variational Autoencoders (VAEs). The top row shows the reconstruction of images using VQGAN and VAE-SD2.1, while the bottom row shows the reconstruction of video frames using TATS and VAE-OSP. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed CV-VAE in both image and video reconstruction.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative comparison of image and video reconstruction. Top: Reconstruction with different Image VAE models (i.e., VQGAN [12] and VAE-SD2.1 [28]) on images; Bottom: Reconstruction with different Video VAE models (i.e., TATS [14] and VAE-OSP [1]) on video frames.

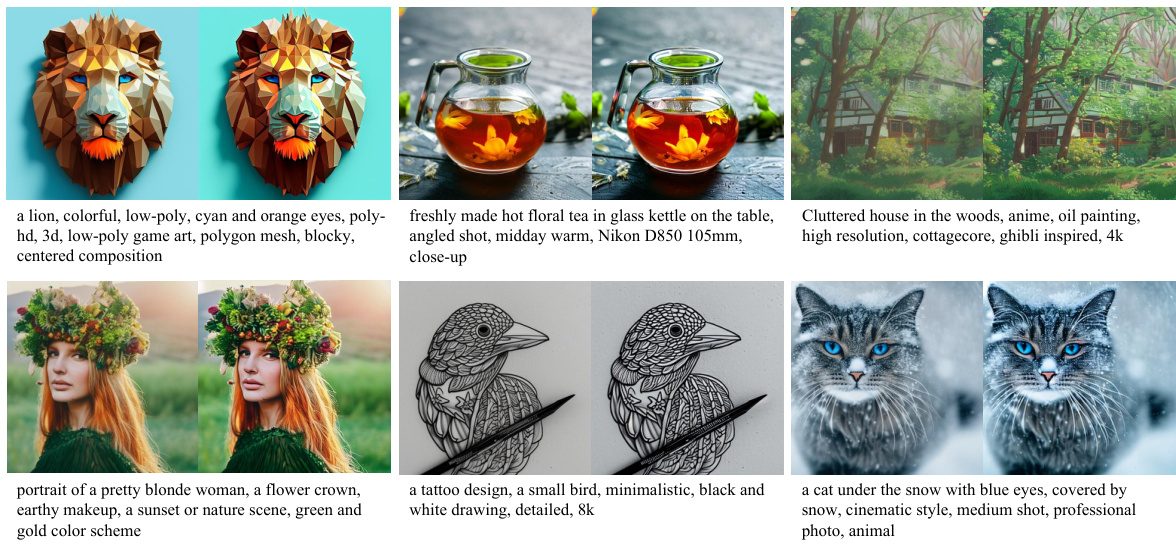

🔼 This figure compares the image generation results of Stable Diffusion 2.1 (SD2.1) using its original image VAE and using the proposed CV-VAE. Each row shows a different text prompt used to generate the images. The left column presents images generated by SD2.1 with its original image VAE, and the right column presents images generated by SD2.1 but with the authors’ proposed CV-VAE replacing the original VAE. This comparison showcases how the CV-VAE affects image generation results compared to the original SD2.1 method.

read the caption

Figure 5: Text-to-image generation comparison. In each pair, the left is generated by the SD2.1 [28] with the image VAE while the right is generated by the SD2.1 with our video VAE.

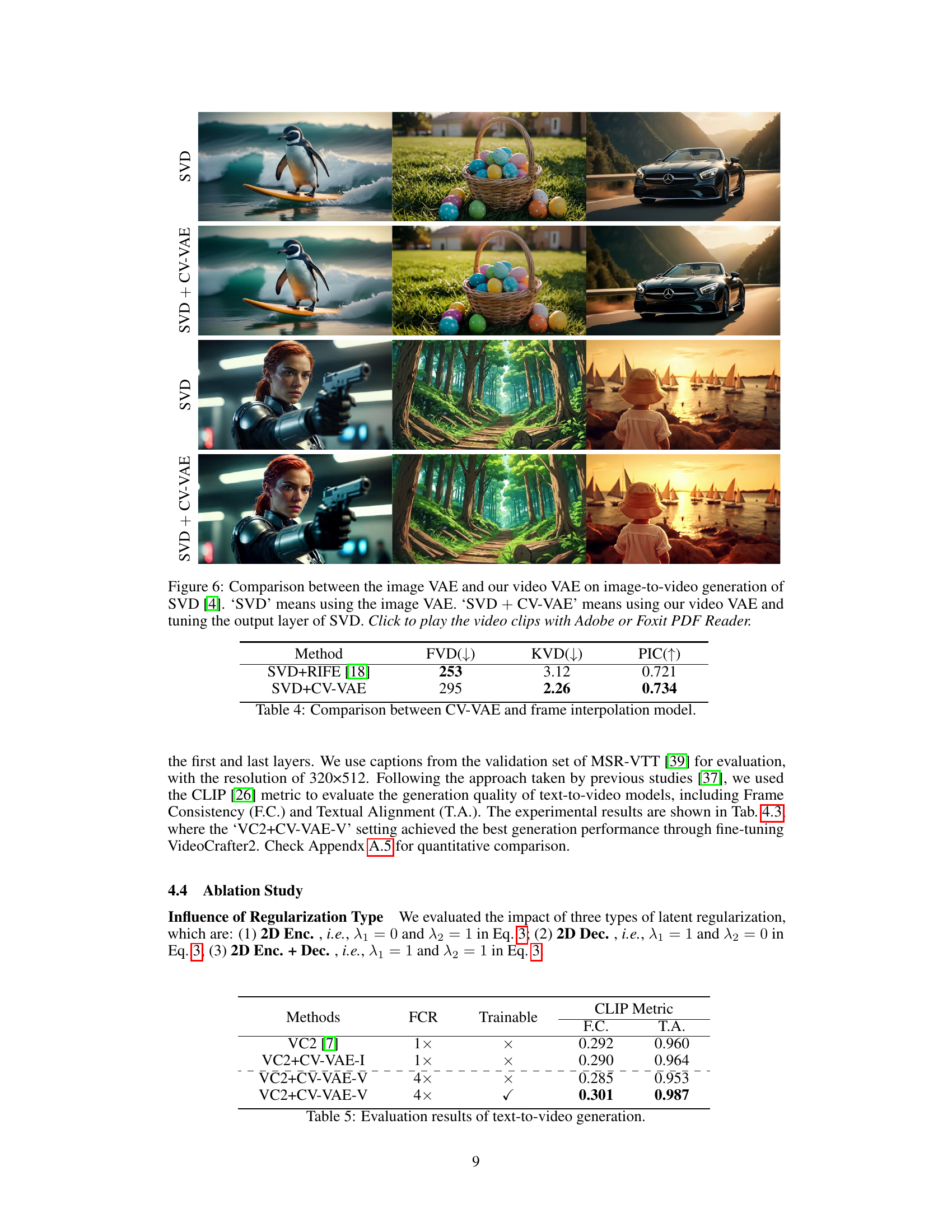

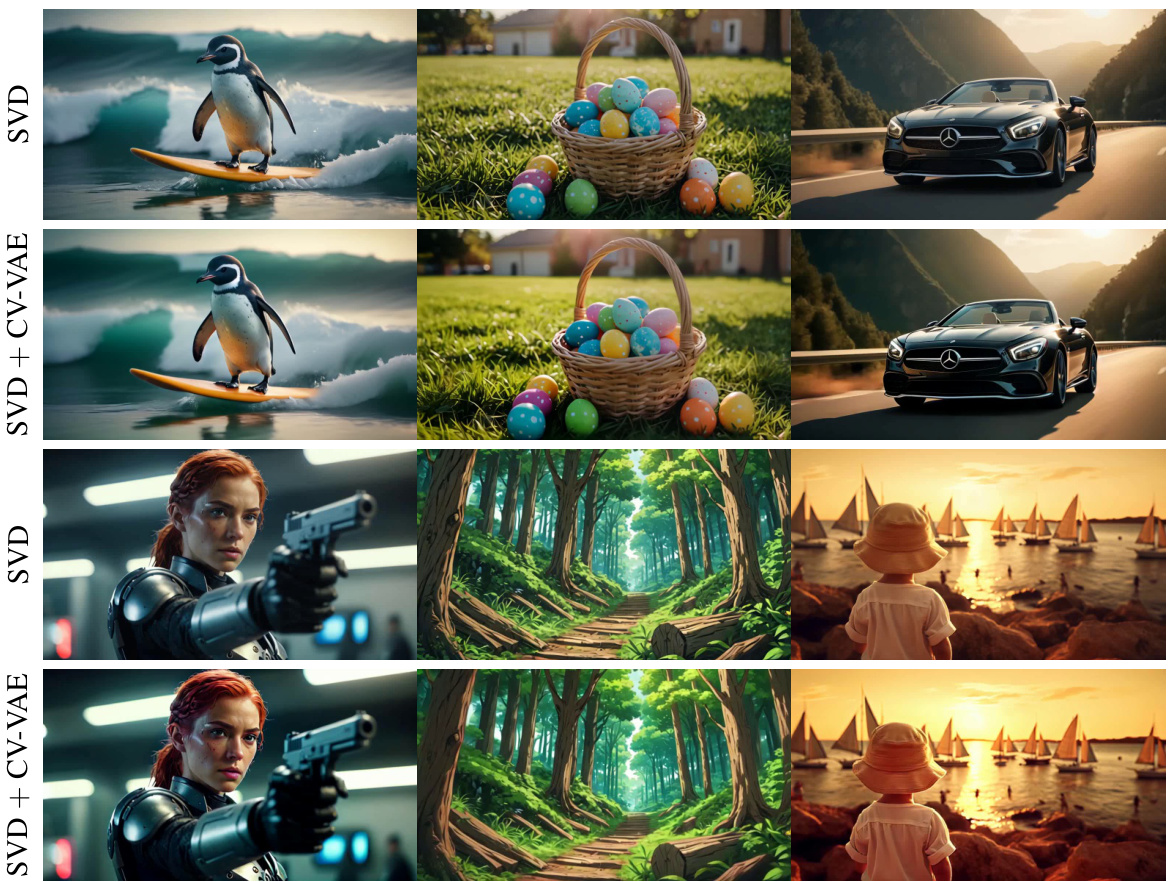

🔼 This figure compares the image-to-video generation results using SVD with the original image VAE (SVD) and with the proposed CV-VAE (SVD + CV-VAE). The top row shows the results generated by SVD, while the bottom row shows the results generated after integrating CV-VAE into SVD and fine-tuning the output layer. The videos are generated using the first frame as a condition and the same random seed. CV-VAE significantly improves the smoothness and length of the generated videos. The reader is directed to click to play the video clips.

read the caption

Figure 6: Comparison between the image VAE and our video VAE on image-to-video generation of SVD [4]. ‘SVD’ means using the image VAE. ‘SVD + CV-VAE’ means using our video VAE and tuning the output layer of SVD. Click to play the video clips with Adobe or Foxit PDF Reader.

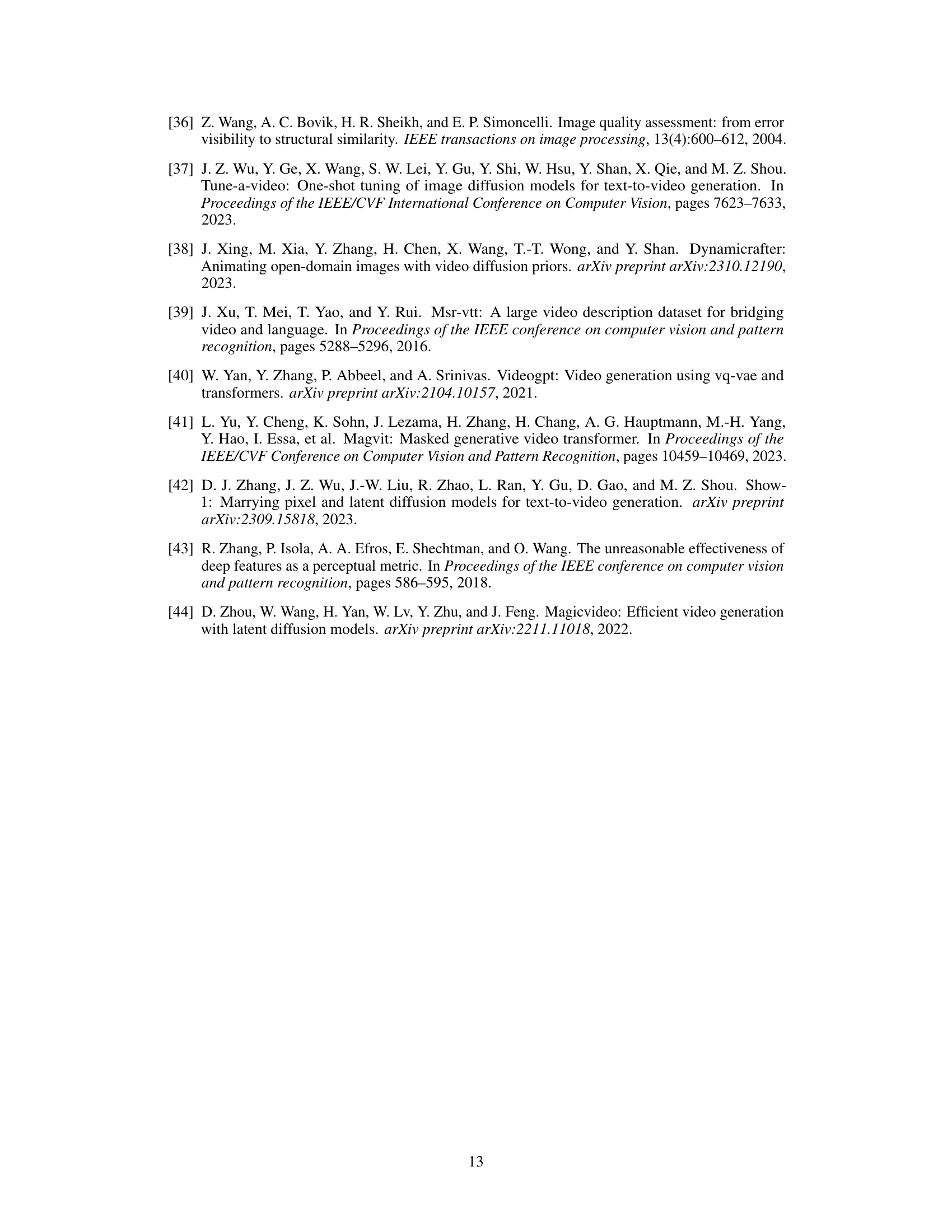

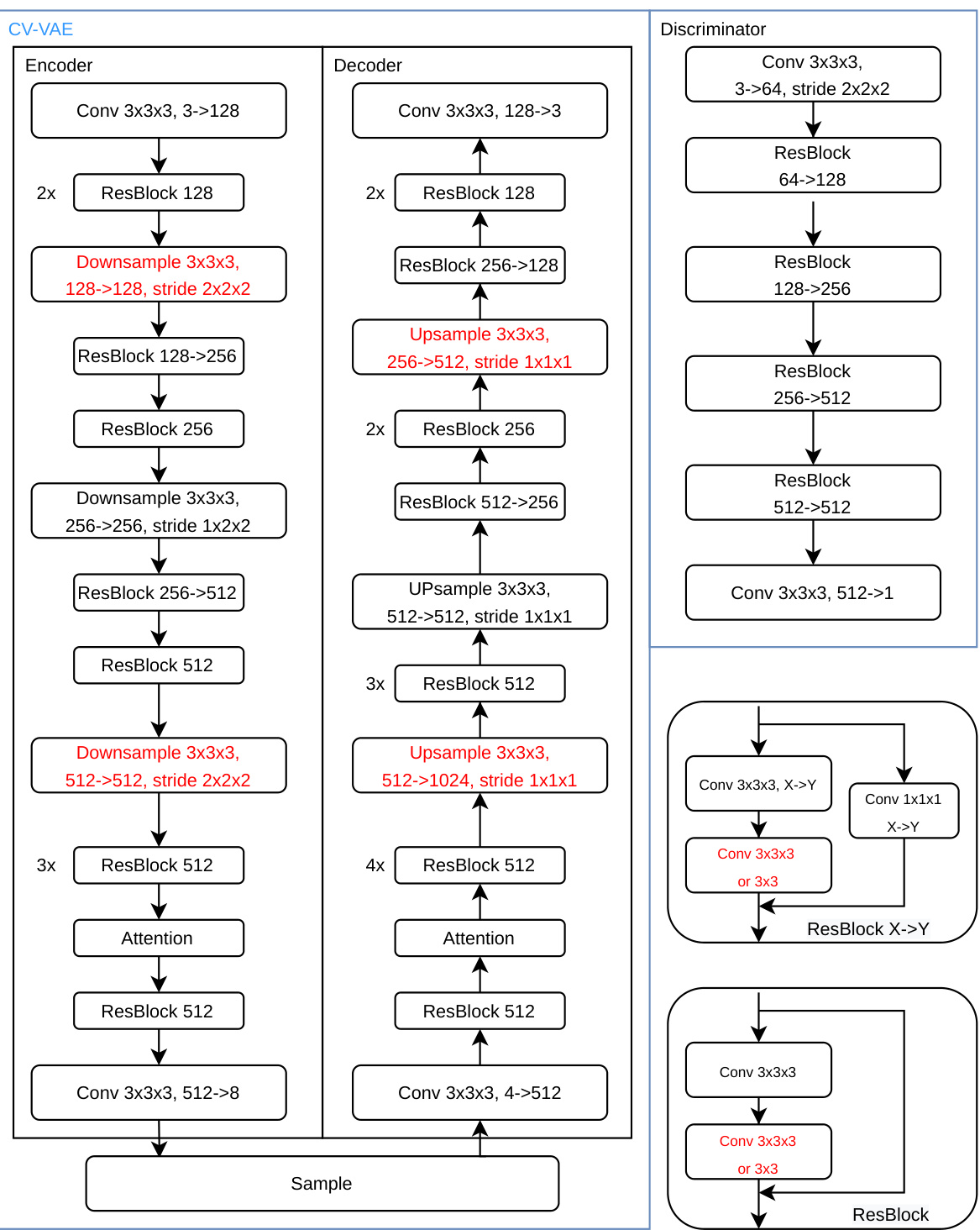

🔼 This figure shows the detailed architecture of the CV-VAE model, including the encoder, decoder, and discriminator. The encoder and decoder are both composed of multiple ResBlock layers, downsampling and upsampling layers, and attention mechanisms. The 3D convolutional layers are highlighted in red, showcasing the key difference from a standard 2D VAE and the method used to inflate it into a 3D version. The discriminator is similarly constructed with convolutional and ResBlock layers. The architecture is designed to efficiently handle both image and video data by employing different inflation strategies in distinct blocks, allowing for truly spatio-temporal compression.

read the caption

Figure 7: Architecture of CV-VAE.

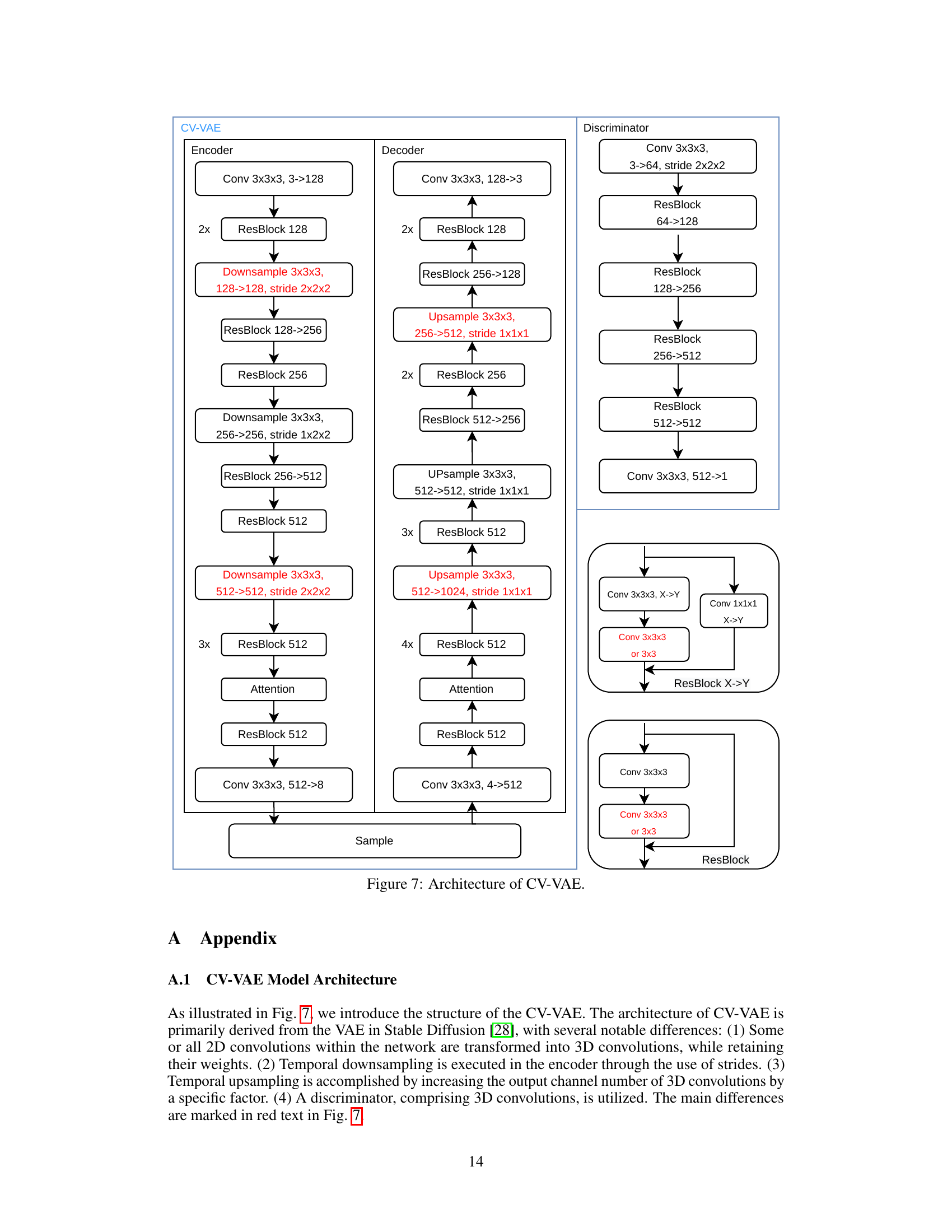

🔼 This figure shows several pairs of images. Each pair consists of an original image on the left and a reconstructed version of that image on the right. The reconstructed images were generated by the authors’ CV-VAE model. The figure aims to demonstrate the high-fidelity reconstruction capability of their model, indicating that the model can effectively encode and decode images while preserving details and textures.

read the caption

Figure 8: Our CV-VAE is capable of encoding and reconstructing images with high fidelity.

🔼 This figure shows the reconstruction results of four consecutive frames from different video clips using the proposed CV-VAE model. Each row represents a different video clip, with the ‘Real’ column showing the original frames and the ‘Reconstructed’ column showing the frames generated by CV-VAE. The results demonstrate the ability of CV-VAE to reconstruct videos with high fidelity, preserving color, structure, and motion information.

read the caption

Figure 9: Reconstruction results of consecutive frames using CV-VAE.

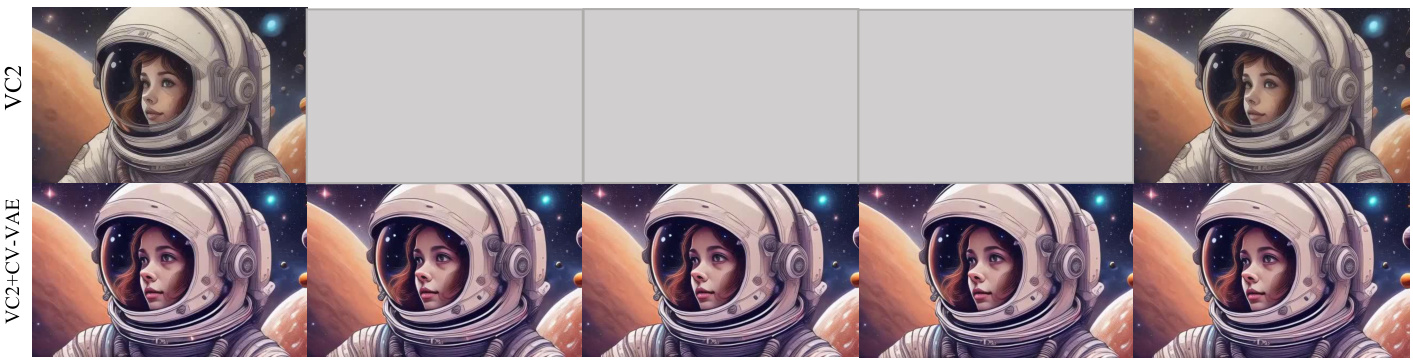

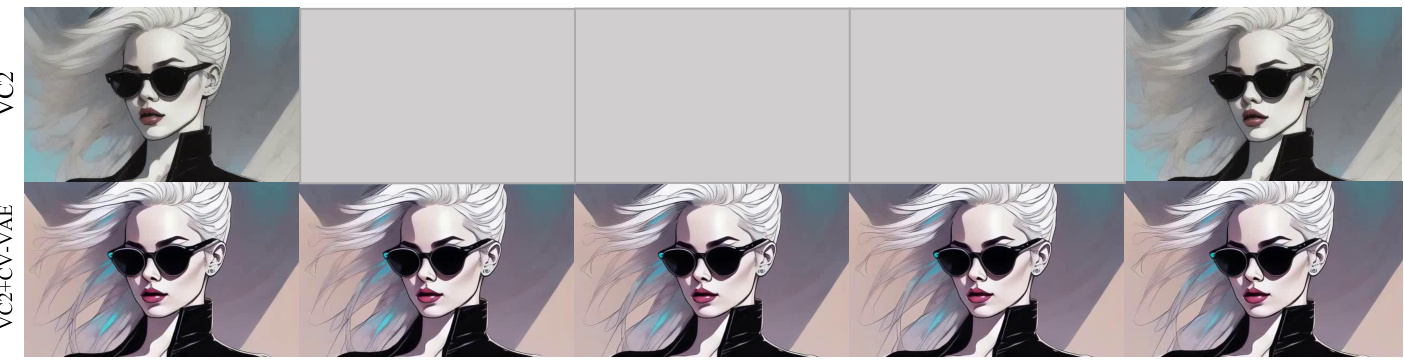

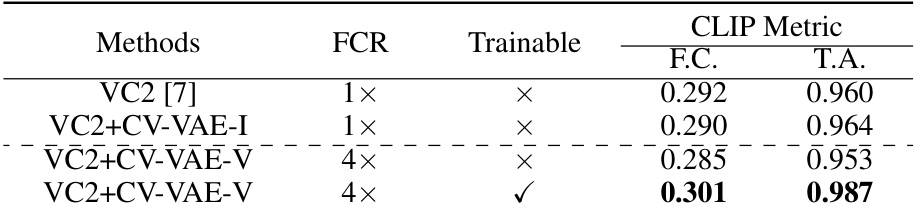

🔼 This figure compares the video generation capabilities of the original VideoCrafter2 model (VC2) with a modified version that uses the proposed CV-VAE. The prompt used is ‘pianist playing somber music, abstract style, non-representational, colors and shapes, expression of feelings, highly detailed’. The comparison shows that integrating CV-VAE into VC2 allows for the generation of significantly longer videos (61 frames vs 16 frames) with smoother transitions, while maintaining comparable computational cost. The missing frames in the original VC2 output are highlighted in gray.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison between the image VAE and our video VAE on text-to-video generation of VC2 [7]. We fine-tuned the last layer of U-Net in VC2 to adapt it to CV-VAE. VC2 generates videos with a resolution of 16 × 320 × 512, while the ‘VC2 + CV-VAE’ produces videos of 61 × 320 × 512 resolution under the same computation. The missing frames in the VC2 results are marked in gray.

🔼 This figure compares the video generation results of Videocrafter2 (VC2) using a standard 2D image VAE versus using the proposed CV-VAE. The CV-VAE, when integrated into VC2, produces significantly more frames (61 vs 16) while maintaining similar computational costs, resulting in smoother and more fluid videos. The grayed-out areas in the VC2 results highlight the missing frames due to the lower frame rate.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison between the image VAE and our video VAE on text-to-video generation of VC2 [7]. We fine-tuned the last layer of U-Net in VC2 to adapt it to CV-VAE. VC2 generates videos with a resolution of 16 × 320 × 512, while the ‘VC2 + CV-VAE’ produces videos of 61 × 320 × 512 resolution under the same computation. The missing frames in the VC2 results are marked in gray.

🔼 This figure compares the video generation results of the original Videocrafter2 model (VC2) with those obtained after integrating the proposed CV-VAE. By fine-tuning only a small portion of the VC2 model (last layer of U-Net), the CV-VAE significantly increases the number of generated frames (from 16 to 61) while maintaining comparable computational resources. The grayed-out frames in the VC2 results highlight the increased frame count provided by CV-VAE, showcasing smoother and more comprehensive video generation.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison between the image VAE and our video VAE on text-to-video generation of VC2 [7]. We fine-tuned the last layer of U-Net in VC2 to adapt it to CV-VAE. VC2 generates videos with a resolution of 16 × 320 × 512, while the ‘VC2 + CV-VAE’ produces videos of 61 × 320 × 512 resolution under the same computation. The missing frames in the VC2 results are marked in gray.

🔼 This figure compares the video generation capabilities of the original VideoCrafter2 (VC2) model with a 2D VAE and a modified version of VC2 that incorporates the authors’ proposed CV-VAE (a 3D video VAE). The comparison highlights the increased frame count achieved by using the CV-VAE, resulting in smoother and more detailed videos with the same computational cost. The gray areas in the top row indicate missing frames generated by VC2, which are filled by CV-VAE in the bottom row.

read the caption

Figure 10: Comparison between the image VAE and our video VAE on text-to-video generation of VC2 [7]. We fine-tuned the last layer of U-Net in VC2 to adapt it to CV-VAE. VC2 generates videos with a resolution of 16 × 320 × 512, while the ‘VC2 + CV-VAE’ produces videos of 61 × 320 × 512 resolution under the same computation. The missing frames in the VC2 results are marked in gray.

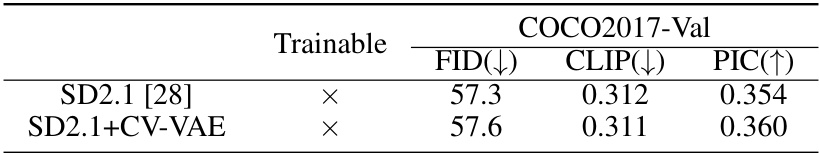

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of text-to-image generation performance between the original Stable Diffusion 2.1 (SD2.1) model and the SD2.1 model integrated with the proposed CV-VAE. The comparison uses three metrics: FID (Fréchet Inception Distance), CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training) score, and PIC (Perceptual Input Conformity). Lower FID and CLIP scores indicate better performance, while a higher PIC score suggests improved perceptual quality. The results show that integrating CV-VAE into SD2.1 does not significantly affect the performance in this specific task.

read the caption

Table 2: Quantitative results of text-to-image generation.

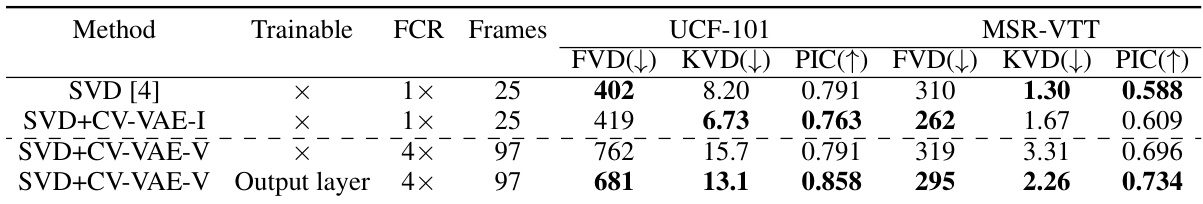

🔼 This table shows the results of image-to-video generation experiments using different configurations of the proposed CV-VAE model. It compares the performance of the SVD model alone against versions incorporating the CV-VAE, both with and without fine-tuning of the output layer. Metrics include Frechet Video Distance (FVD), Kernel Video Distance (KVD), and Perceptual Input Conformity (PIC). The table also indicates whether the model was trainable, the frame compression rate (FCR), and the number of frames generated.

read the caption

Table 3: Evaluation results of image-to-video generation. FCR denotes the frame compression rate.

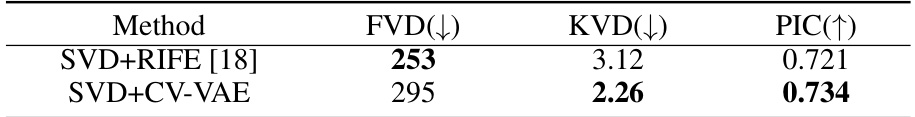

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed CV-VAE method against the RIFE frame interpolation method on image-to-video generation. The evaluation metrics include FVD (Frechet Video Distance), KVD (Kernel Video Distance), and PIC (Perceptual Input Conformity). Lower FVD and KVD values indicate better quality, while a higher PIC value is preferred. The results show that, while both methods generate video, CV-VAE has better performance on KVD and PIC scores.

read the caption

Table 4: Comparison between CV-VAE and frame interpolation model.

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of image-to-video generation using different methods. It compares the performance of the original SVD model against versions integrated with the proposed CV-VAE model, both with and without fine-tuning. The metrics used to evaluate performance are FVD (Fréchet Video Distance), KVD (Kernel Video Distance), and PIC (Perceptual Input Conformity). The table also shows the frame compression rate (FCR) achieved by each method, indicating the level of temporal compression.

read the caption

Table 3: Evaluation results of image-to-video generation. FCR denotes the frame compression rate.

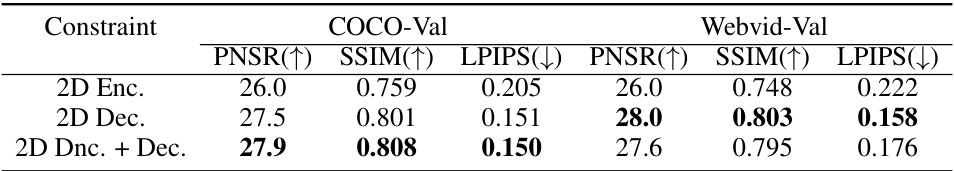

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing different latent space regularization methods used in training the video VAE. The methods compared are using the 2D encoder only, the 2D decoder only, and both the 2D encoder and decoder. The table shows the performance (PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS) on the COCO-Val and Webvid-Val datasets for each method. This helps determine which regularization strategy is most effective for the task.

read the caption

Table 6: Comparison of different regularization types.

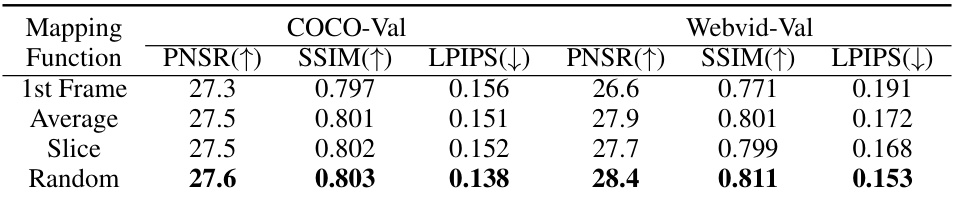

🔼 This table presents a comparison of four different mapping functions used in the latent space regularization method of the CV-VAE model. Each function aims to bridge the dimensional gap between the input video (X) and the reconstructed video (X^r). The table shows the results of using each mapping function on both COCO-Val and Webvid-Val datasets, evaluating the performance using Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS). Higher PSNR and SSIM values indicate better image quality, while lower LPIPS values indicate better perceptual similarity. The comparison helps to determine which mapping function yields the best reconstruction results for the video VAE.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison of different mapping functions.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of image and video reconstruction performance between the VAE-SD3 and CVVAE-SD3 models. It shows the parameter count (Params), frame compression rate (FCR), compatibility with existing generative models (Comp.), and reconstruction metrics (PSNR, SSIM, LPIPS) for both COCO-Val and Webvid-Val datasets. The results demonstrate the trade-off between increased model size and improved reconstruction quality.

read the caption

Table 8: Quantitative evaluation on image and video reconstruction between. FCR represents the frame compression rate, and Comp. indicates compatibility with existing generative models.

Full paper#