TL;DR#

Traditional views of grid cells in spatial navigation focus on their highly symmetrical hexagonal firing patterns. Recent studies, however, demonstrate that these patterns can be distorted by salient spatial landmarks, such as rewarded locations. This distortion challenges the existing understanding and necessitates a more comprehensive framework for studying the interactions between spatial representations and environmental cues. The paper addresses this by introducing a novel framework to quantify and explain the observed distortions in grid cell activity.

The researchers trained path-integrating recurrent neural networks (piRNNs) on a spatial navigation task that involved predicting the agent’s position with emphasis on rewarded locations. Notably, the piRNNs exhibited grid-like neural activity which was then analyzed in terms of their firing patterns and the corresponding neural manifolds. The key finding was that while the geometry of the grid cell code was distorted, the topology remained unchanged. This suggests that grid cells retain their fundamental navigational function, but also dynamically adapt to changing environments by encoding salient features as global distortions in their firing patterns.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in neuroscience and computational modeling because it bridges the gap between theoretical models and biological observations of spatial navigation. By demonstrating the global impact of local reward changes on grid cell activity, it opens new avenues for investigating the brain’s flexible mechanisms for adapting to dynamic environments and paves the way for more sophisticated computational models of spatial cognition.

Visual Insights#

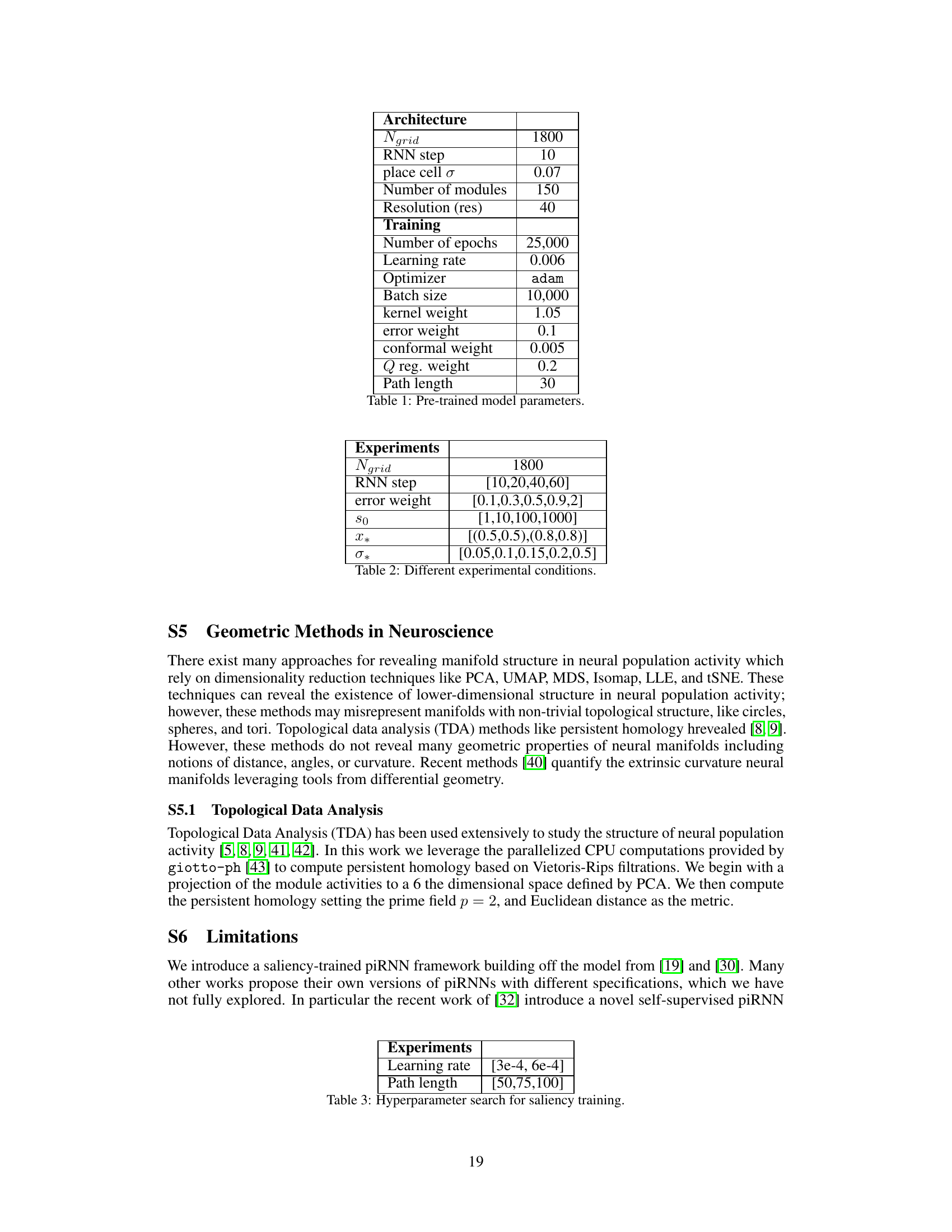

🔼 This figure illustrates the path integration process in neural systems. The left panel shows an agent moving in a 2D environment, with its real path and inferred path indicated. The middle panel depicts a piRNN or grid cells receiving velocity input and outputting inferred positions. The right panel visualizes the firing field of a grid cell and the neural manifold formed by the grid cell module.

read the caption

Figure 1: Path integrating Neural Systems. Left: an artificial agent explores its 2D environment traveling along the path xt shown in black. Middle: the agent's velocity vt is given as input to neurons in a path-integrating recurrent neural network (piRNN) or grid cells in the mammalian brain [13]. The agent maintains a representation of its movement across multiple grid cell modules. This representation is linearly decoded onto place cells, providing an estimate of the agent's new position 2t+1. Right: Each grid cell has a firing field that is a hexagonal lattice. Together, grid cells' activity within a grid cell module forms a 2D torus [9, 20].

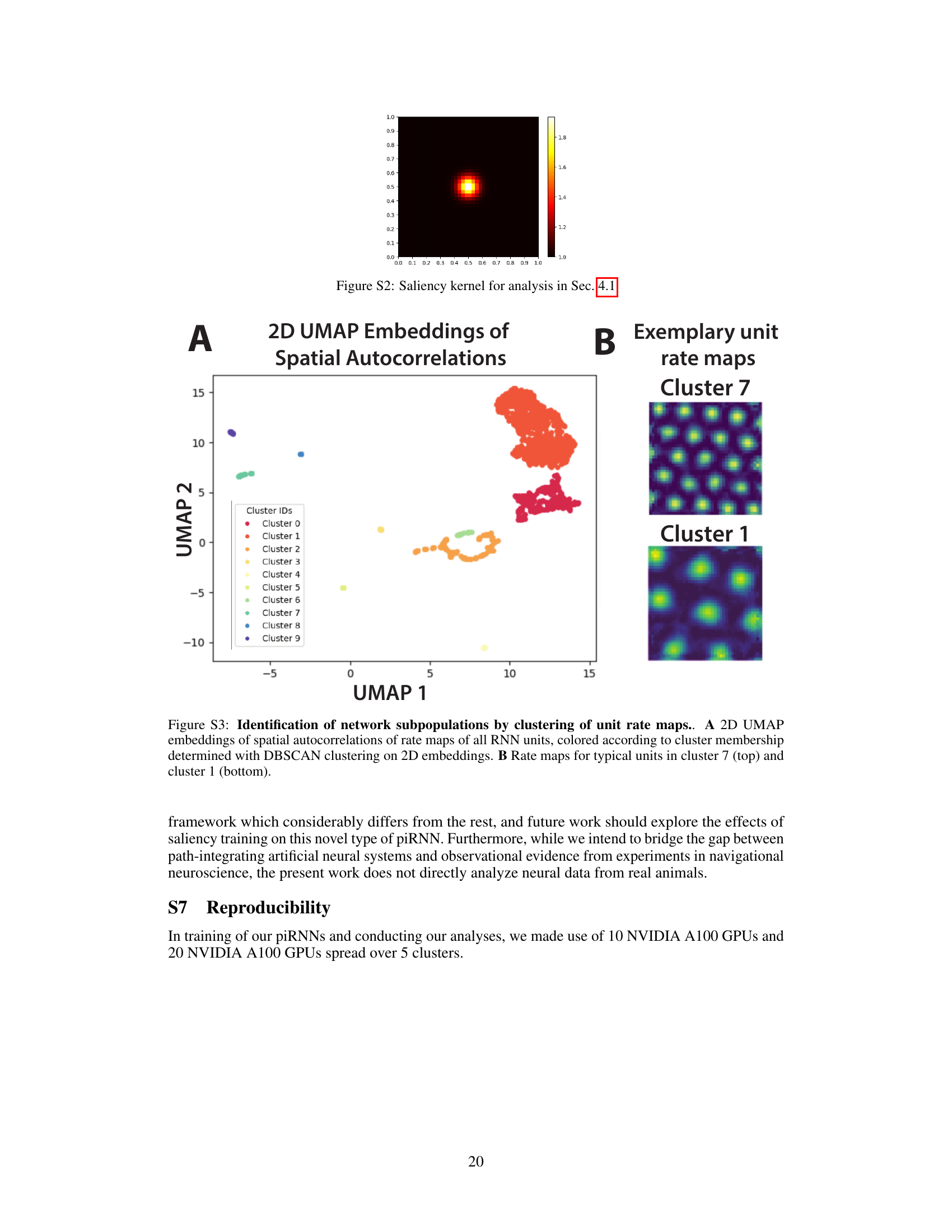

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used for pre-training the piRNN model before introducing the reward. It includes architecture details such as the number of grid cells, RNN steps, and place cell sigma; training details like the number of epochs, learning rate, optimizer, batch size, and various weight parameters; and details about the path length used during training.

read the caption

Table 1: Pre-trained model parameters.

In-depth insights#

Grid Cell Deform#

The concept of “Grid Cell Deform” in the context of spatial navigation research is fascinating and suggests a significant departure from traditional models. Classically, grid cells’ hexagonal firing patterns were seen as a stable, inherent feature for path integration. However, the observed distortions or deformations challenge this view, indicating a dynamic interplay between grid cell activity and environmental context. The presence of rewards, landmarks, or salient cues causes measurable deviations from the perfect hexagonal lattice, implying that these cells are not solely responsible for objective spatial mapping, but also reflect subjective, action-relevant spatial representation. The nature of the deformation is crucial; if only the geometry is impacted, but not the underlying topology of the grid field, it suggests a flexible neural coding strategy. The preserved topology ensures path integration remains intact despite adaptation to environmental cues. This dual nature of grid cell responses, integrating both global spatial information and local, reward-related information, opens exciting avenues for understanding how brains prioritize and encode information in dynamically changing environments. This also necessitates a recalibration of computational models of path integration to incorporate flexible, reward-modulated grid cell responses for a more comprehensive understanding of spatial navigation.

piRNN Reward Int#

The heading ‘piRNN Reward Int’ likely refers to a section detailing the integration of reward mechanisms within a path-integrating recurrent neural network (piRNN). This is a crucial aspect of the research because it explores how the piRNN model adapts its spatial navigation strategy in response to environmental cues, specifically rewards. The analysis likely involves examining changes in the network’s internal representation (e.g., grid cell activity) as a result of reward. Key insights might include how reward influences the topology and geometry of the grid cell representations, revealing whether the network preserves the fundamental hexagonal lattice structure or undergoes distortions, and if so, how those distortions affect path integration performance. The research may investigate the trade-off between maintaining accurate global spatial representation and incorporating local reward information. It is important to consider whether the introduction of reward leads to local or global changes in the piRNN’s behavior. The exploration of the impact of reward on the network’s behavior is likely to yield valuable insights into the mechanisms by which the brain integrates spatial information and reward signals for efficient navigation and decision-making, offering a potential bridge between computational models and biological neural systems.

Manifold Topology#

The concept of ‘Manifold Topology’ in the context of neural systems, specifically regarding grid cells, offers a powerful framework for understanding spatial representation. The topological structure of the grid cell module, often described as a 2D torus, is fundamental to its function in path integration. Distortions introduced by reward or other salient environmental cues, however, raise critical questions. Do these distortions affect the underlying topology, or are they primarily geometric transformations? The paper suggests that the topology remains preserved even when geometric distortions are observed in the individual grid cell firing fields. This preservation of topology implies that the fundamental spatial map, encoded by the connectedness of the grid cell representations, remains intact. The global nature of the distortions, despite local changes in reward, further supports this idea. These global distortions, the paper suggests, may reflect the dynamic encoding of environmental cues, enabling the system to prioritize relevant information while still maintaining reliable path integration capabilities. Understanding how topology and geometry interact in the context of these distortions is key to gaining a complete understanding of grid cell function. Future research should focus on investigating other types of environmental changes and exploring the implications of the dynamic interplay between topological stability and geometric flexibility in the neural manifold.

Global vs. Local#

The concept of ‘Global vs. Local’ in the context of spatial navigation within the brain involves understanding how the brain integrates local environmental cues with global spatial representations. Traditional models often emphasized a purely global, metric-based representation, such as grid cells forming a hexagonal lattice. However, recent research suggests that these representations are dynamic and influenced by local factors, like the presence of rewards or landmarks. The paper investigates this dichotomy by training recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to perform path integration in environments with and without reward cues. The core finding suggests that rewards introduce global distortions in the grid cell firing patterns, even though the reward itself is localized. This is a significant departure from simpler models which assumed that local cues impact grid cell firing locally. Instead, this global distortion maintains the global topological structure crucial for path integration, but the heterogeneity within individual responses reflects and incorporates the environmental cues, hinting at a mechanism for dynamically updating spatial maps based on experience and behavioral relevance.

Continual Learning#

The concept of continual learning, while not explicitly a heading in the provided research paper, is central to the paper’s core findings. The study demonstrates that grid cells, crucial for spatial navigation, exhibit a remarkable ability to adapt to changing environmental cues, specifically the introduction of rewards. This adaptability is not achieved by completely restructuring the existing spatial representation, but rather through dynamic adjustments that prioritize environmental landmarks. The paper highlights the preservation of the underlying topological structure of grid cell activity, supporting the idea of continual learning through a dual representation. This dual representation allows the grid cells to maintain their foundational navigation capabilities (topology) while simultaneously encoding dynamically changing environmental information (geometry). This implies the existence of neural mechanisms that facilitate gradual adaptation to new information without catastrophic forgetting, suggesting a form of implicit regularization at play within the brain’s spatial navigation system. Global distortions in grid cell activity, despite local changes in reward placement, further support this conclusion. The study’s findings suggest that continual learning in spatial navigation relies not on drastic remodeling, but rather on flexible mechanisms that integrate new information without disrupting the system’s fundamental functionality.

More visual insights#

More on figures

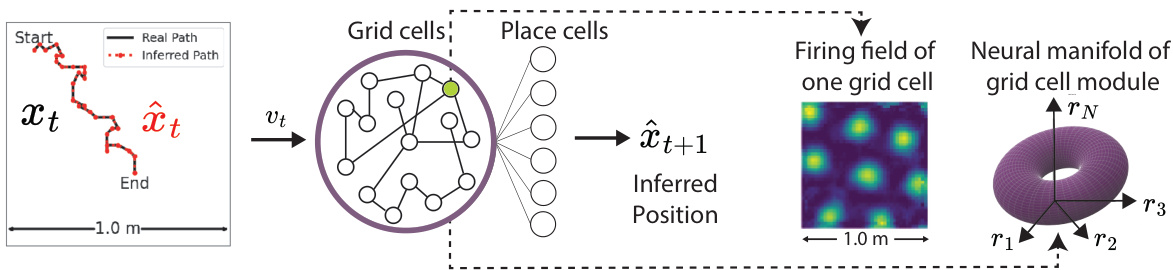

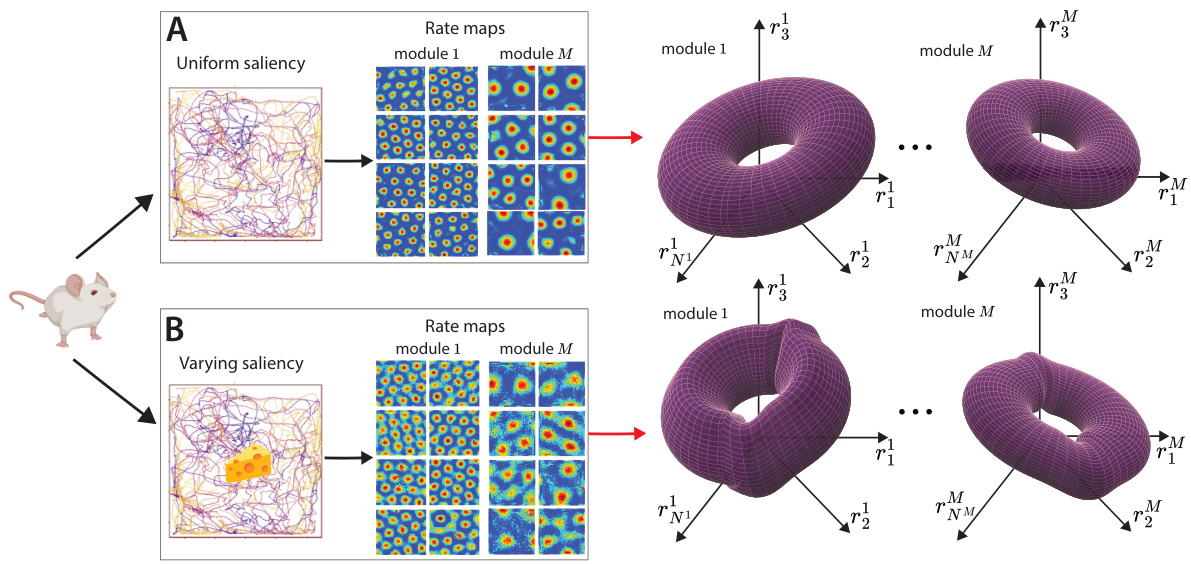

🔼 This figure shows how the geometry of grid cell module tori changes in the presence of salient features in the environment. Panel A depicts a scenario with uniform spatial saliency, where canonical grid cells exhibit hexagonal lattice responses. The population activity of a grid cell module forms a torus in neural state space. Panel B illustrates a scenario with varying saliency (due to rewards), where the grid cells adjust their responses, leading to geometric deformations of the neural tori.

read the caption

Figure 2: Geometry of grid cell module tori is changed by presence of salient features in the environment. A. An agent (for us, a piRNN) is trained to perform path integration in its 2D environment with uniform spatial saliency. Canonical grid cells develop hexagonal lattice responses (rate maps) across M modules. The population activity of a single grid cell module forms a torus in neural state space. B. The same agent undergoes a second phase of training, with its environment now containing rewards (areas of high importance, or saliency). We model this saliency by modifying the loss of our piRNN to prioritize accurate position decoding near rewards. Its grid cells adjust their individual responses, which we link to geometric deformations of the neural tori.

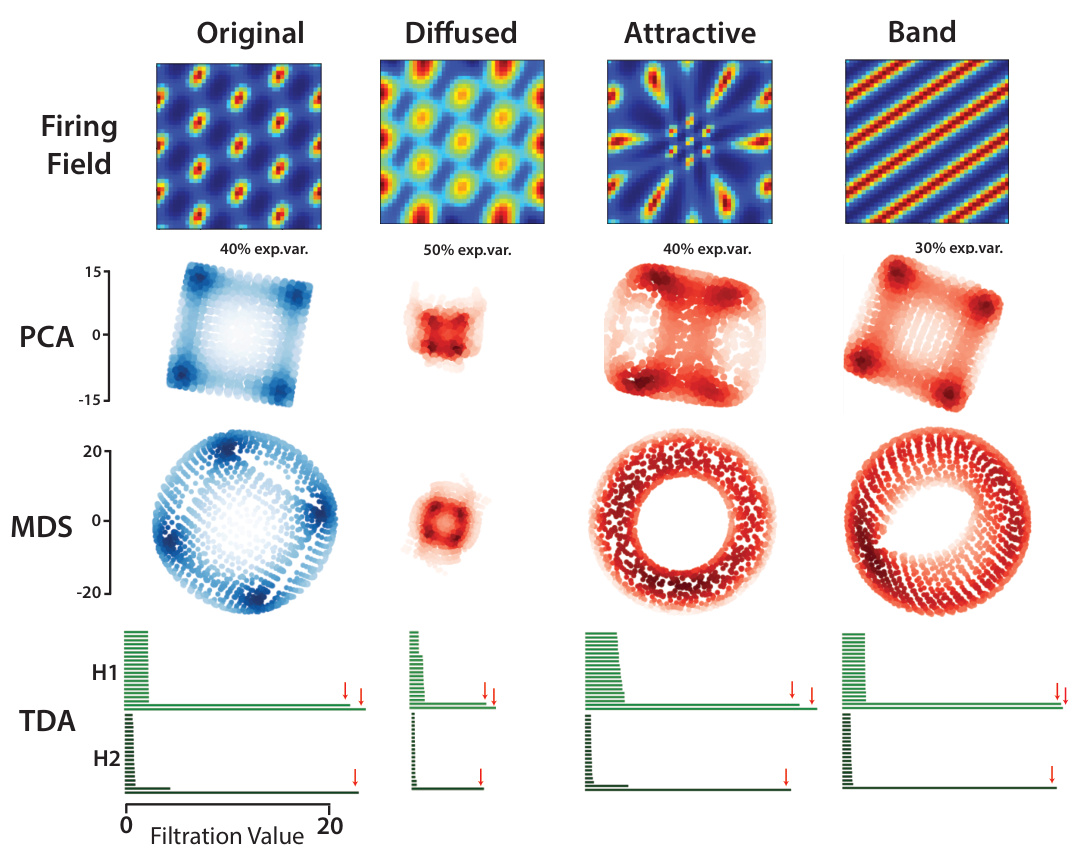

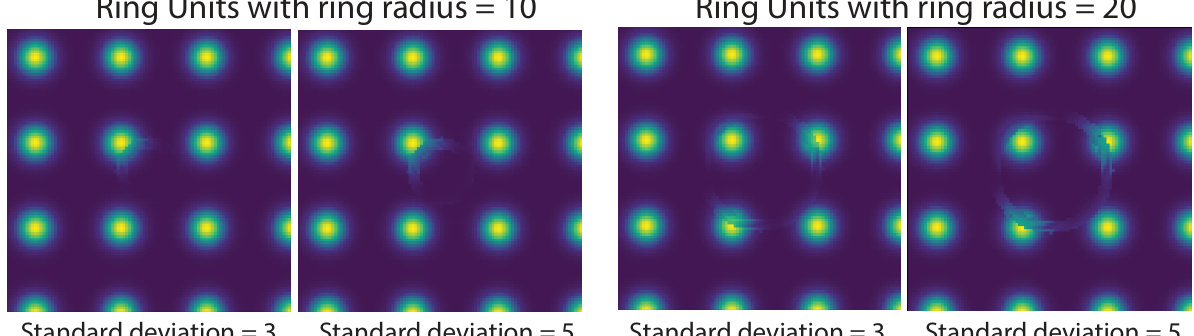

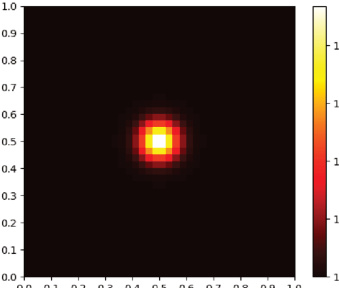

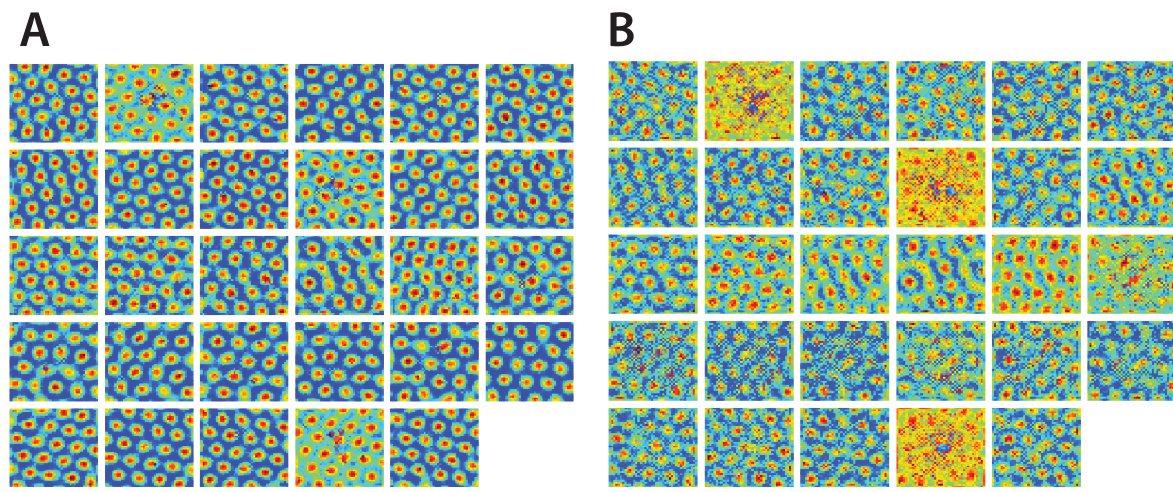

🔼 This figure shows the effects of different types of firing field deformations on the resulting neural manifold topology, using synthetic grid cells as examples. It demonstrates that while geometry can change (size and curvature), the topology (toroidal shape) remains largely consistent, supporting the key argument regarding the robustness of the topological structure in grid cell representations.

read the caption

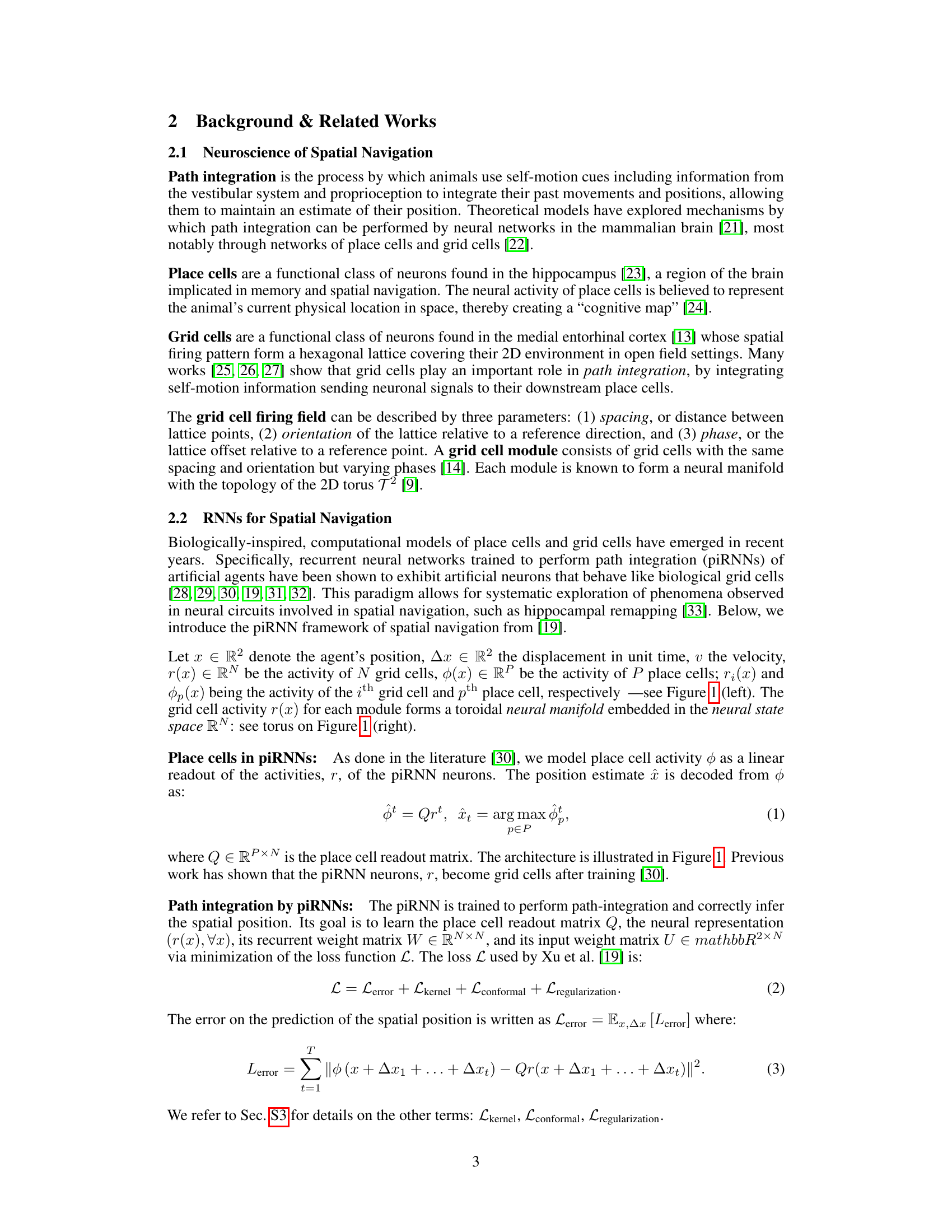

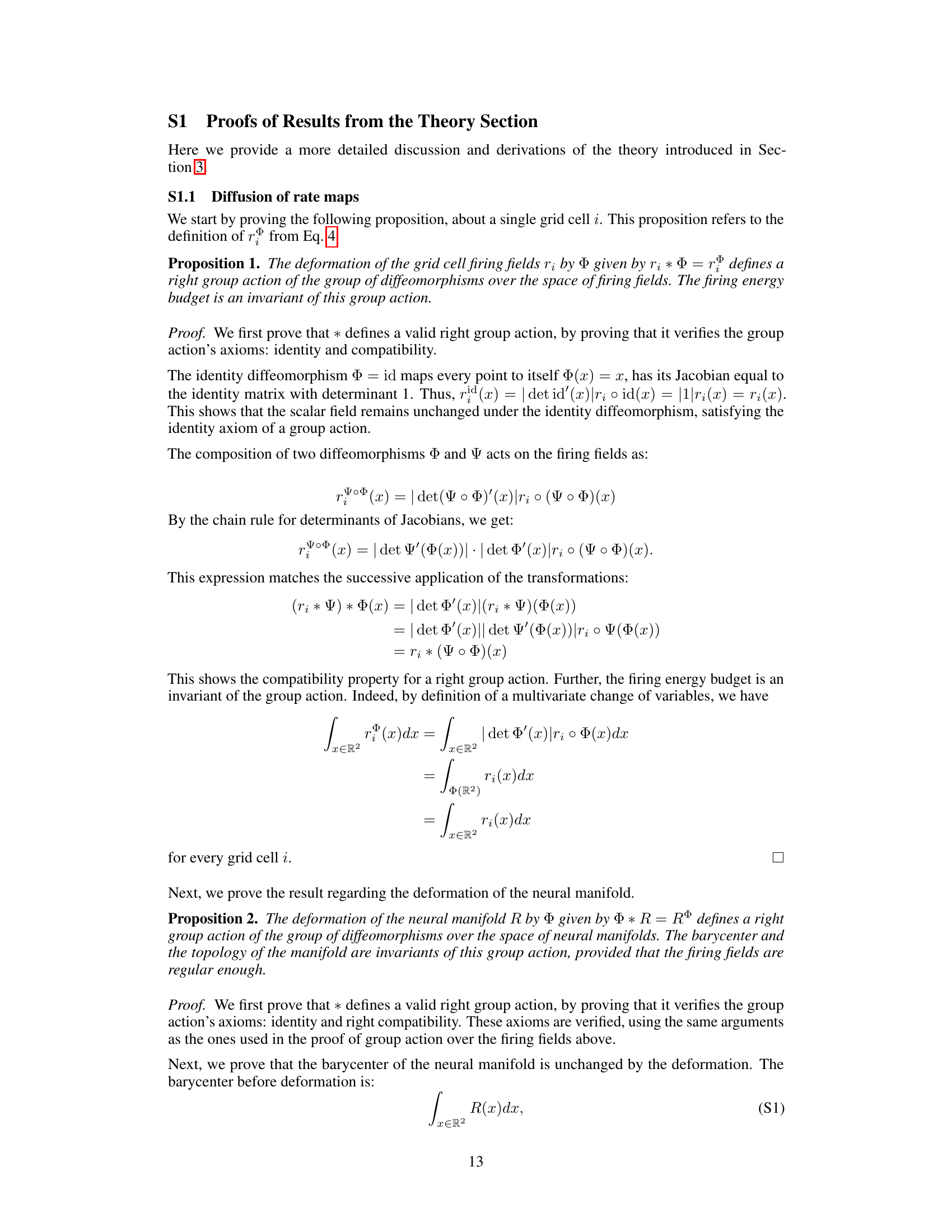

Figure 3: Relating firing fields to neural manifolds across deformations in synthetic grid cells. We investigate how deformations away from perfect hexagonal symmetry in the firing fields of synthetic grid cells affects the geometry of the toroidal neural manifold. From left to right. Original units. The original hexagonal grid cells show clear signatures of toroidal topology, as indicated by the presence of 2 loops in the first homology group (H1) and 1 void in the second homology group (H2). We show 2D projections using principal components analysis (PCA) and multidimensional scaling (MDS) to serve as baselines against which to compare the manifolds of deformed grid cells. PCA projections are consistent with a “flat” torus geometry. Diffused units. Diffused units created from convolution of the original grid cells with a Gaussian kernel maintain toroidal topology, but PCA and MDS show that the size of the neural manifold is reduced as predicted by theory. Attracted units. Inspired by experimental evidence from [15] we created attracted units from synthetic grid cells by applying a diffeomorphism to the 2D environment. While manifold size is unchanged, PCA projections suggest the torus becomes more curved in neural state space. Toroidal topology is preserved. Band units. We created a synthetic module with 17% of original grid units replaced with band units of same spatial scale, with uniformly distributed orientations. The geometry and topology of the resulting manifold are largely unchanged.

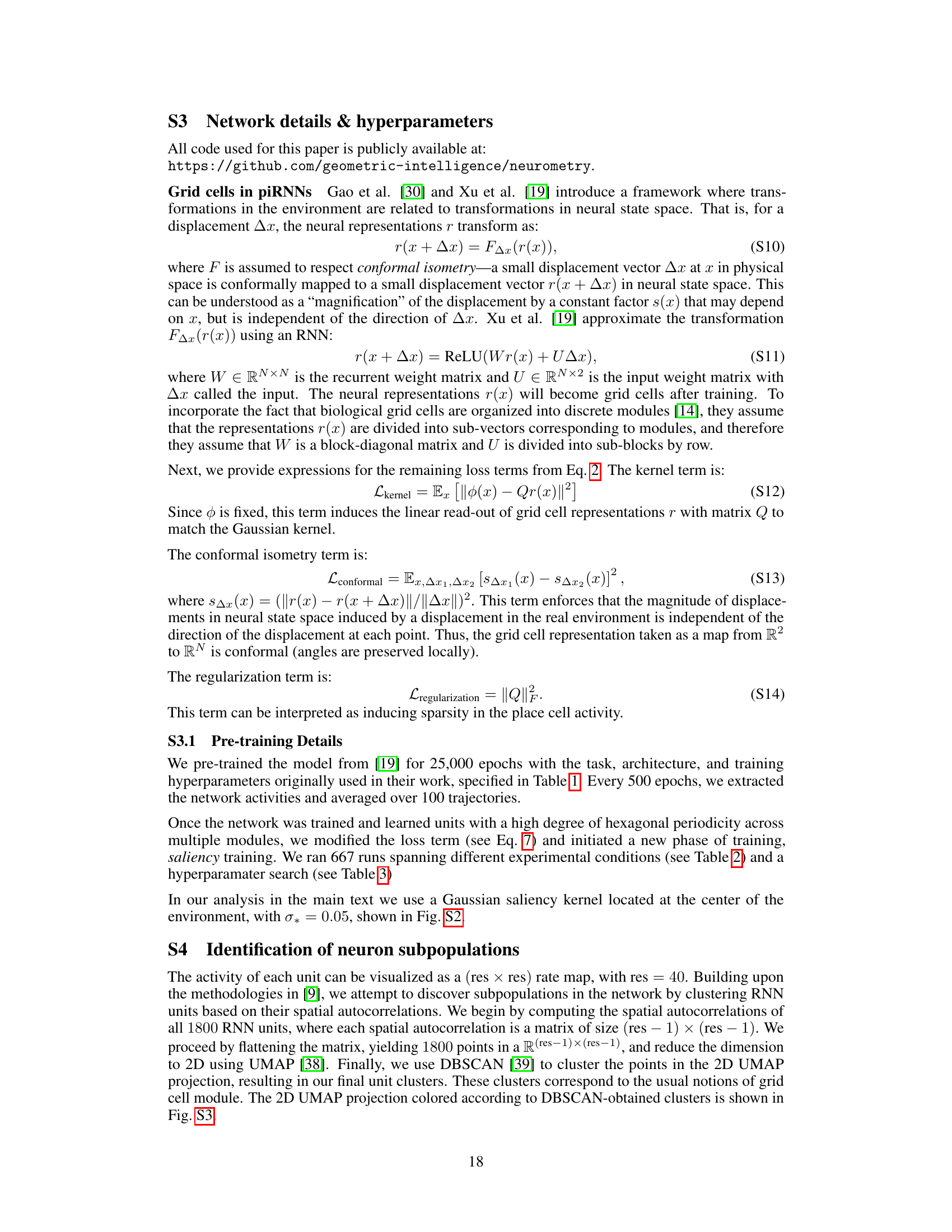

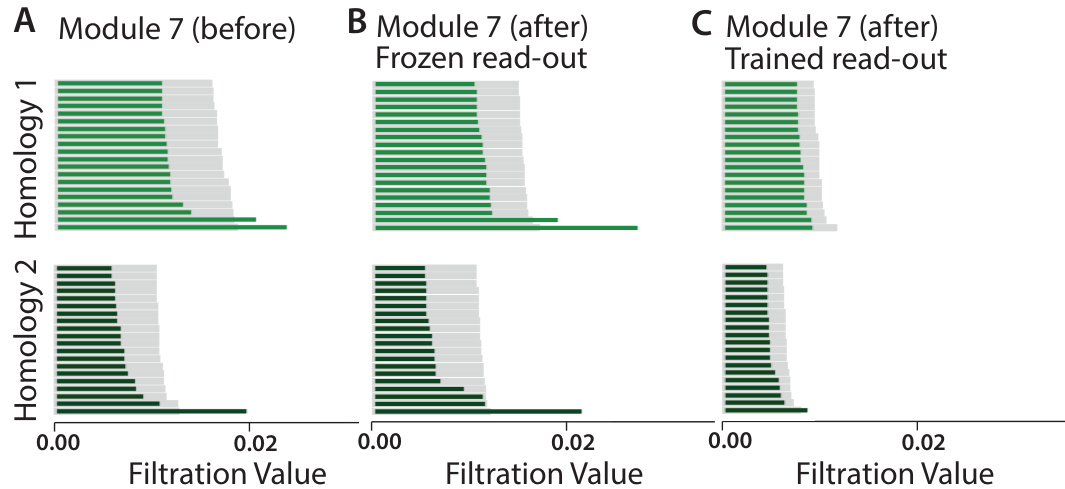

🔼 This figure shows the effects of saliency training on the toroidal topology of a grid cell module. Persistent homology is used to analyze the topology of the neural manifold before and after training. The results demonstrate that freezing the place cell read-out during saliency training preserves the toroidal topology, while allowing the read-out to change leads to its destruction.

read the caption

Figure 4: Toroidal topology is preserved after saliency training when place cell read-out is frozen. For grid cell module 7, we project the neural activity to 6 dimensions using PCA, and perform persistent homology. We show the 20 most persistent features for homology dimension 1 (loops) and homology dimension 2 (voids). Gray bars are 20 most persistent features from 10 random shuffles of the data. A. The population activity of module 7 of the pretrained RNN (before saliency training) has Betti numbers (1,2,1), consistent with toroidal topology. B. The population activity of module 7 of the RNN after saliency training retains toroidal topology, if place cell read-out is frozen (only grid representations are allowed to change). C. The toroidal topology is destroyed after saliency training if place cell read-out is allowed to change.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying a Gaussian filter to the firing fields of grid cells. The left column shows the results before applying the filter, and the right column shows the results after. The top two rows show 2D projections of the neural manifold using PCA and MDS. The bottom two rows show the persistent homology of the neural manifold. The results show that applying the Gaussian filter reduces the size of the neural manifold while preserving its topology.

read the caption

Figure 6: Diffused units lead to reduction in the manifold size. When we analyzed a module with many emergent diffused units after the saliency training, we observed that the topology of the module was preserved. However, the size of the manifold was reduced in line with our Conjecture 1.

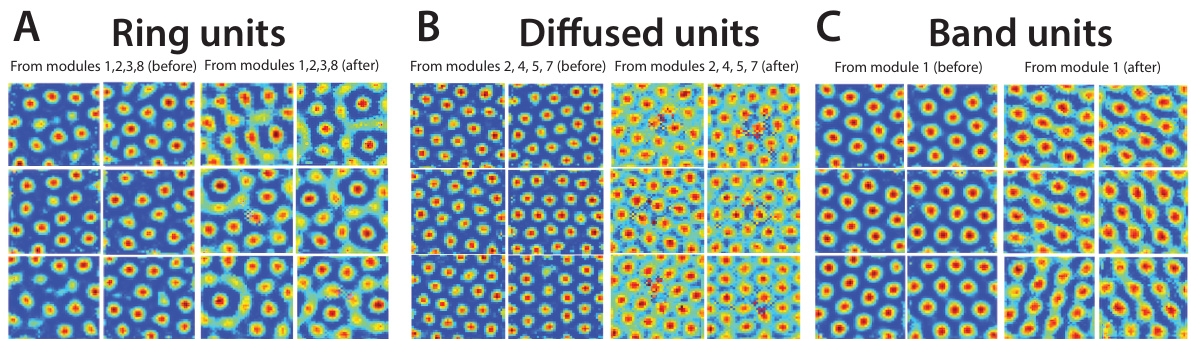

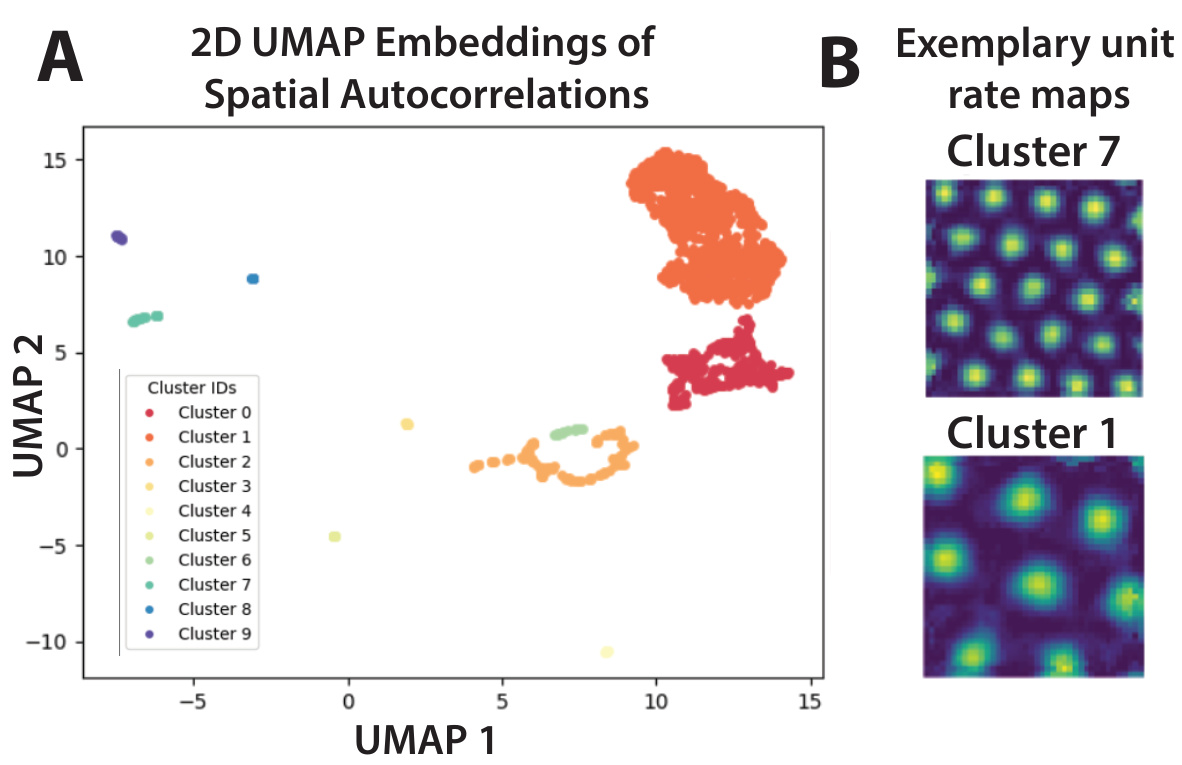

🔼 Figure 5 shows three different types of distorted grid cell tuning features that emerged in the piRNNs after training with non-uniform spatial saliency. The figure is divided into three panels (A, B, and C). Panel A shows the emergence of units with ring-like patterns; Panel B shows units with diffused activity; Panel C shows units with band-like patterns. Each panel shows example units before and after saliency training.

read the caption

Figure 5: Saliency-tuned piRNNs develop diverse set of tuning features observed in neuroscience. A. Across multiple modules, we observe the emergence of many units characterized by rings of high activity. B. We also observe the emergence of diffused units which are active almost everywhere. C. Finally, we find many units develop band structures.

🔼 This figure shows how different types of distortions in synthetic grid cell firing fields affect the geometry of the corresponding neural manifolds. It demonstrates that while the topology (toroidal shape) is generally preserved, geometric properties such as size and curvature can change. The four types of distortions illustrated are: original (undistorted) units, diffused units, attracted units, and band units.

read the caption

Figure 3: Relating firing fields to neural manifolds across deformations in synthetic grid cells. We investigate how deformations away from perfect hexagonal symmetry in the firing fields of synthetic grid cells affects the geometry of the toroidal neural manifold. From left to right. Original units. The original hexagonal grid cells show clear signatures of toroidal topology, as indicated by the presence of 2 loops in the first homology group (H1) and 1 void in the second homology group (H2). We show 2D projections using principal components analysis (PCA) and multidimensional scaling (MDS) to serve as baselines against which to compare the manifolds of deformed grid cells. PCA projections are consistent with a 'flat' torus geometry. Diffused units. Diffused units created from convolution of the original grid cells with a Gaussian kernel maintain toroidal topology, but PCA and MDS show that the size of the neural manifold is reduced as predicted by theory. Attracted units. Inspired by experimental evidence from [15] we created attracted units from synthetic grid cells by applying a diffeomorphism to the 2D environment. While manifold size is unchanged, PCA projections suggest the torus becomes more curved in neural state space. Toroidal topology is preserved. Band units. We created a synthetic module with 17% of original grid units replaced with band units of same spatial scale, with uniformly distributed orientations. The geometry and topology of the resulting manifold are largely unchanged.

🔼 This figure shows how the geometry of grid cell module tori changes in the presence of salient features (rewards) in the environment. Panel A illustrates a scenario with uniform saliency, resulting in canonical grid cells with hexagonal lattice responses. Panel B demonstrates the changes when rewards are introduced. The introduction of reward changes the individual responses of grid cells, leading to geometric deformations of the neural tori. The figure highlights the link between the introduction of reward in the environment and the geometric changes in the neural representations of the grid cells.

read the caption

Figure 2: Geometry of grid cell module tori is changed by presence of salient features in the environment. A. An agent (for us, a piRNN) is trained to perform path integration in its 2D environment with uniform spatial saliency. Canonical grid cells develop hexagonal lattice responses (rate maps) across M modules. The population activity of a single grid cell module forms a torus in neural state space. B. The same agent undergoes a second phase of training, with its environment now containing rewards (areas of high importance, or saliency). We model this saliency by modifying the loss of our piRNN to prioritize accurate position decoding near rewards. Its grid cells adjust their individual responses, which we link to geometric deformations of the neural tori.

🔼 This figure shows how different types of deformations in synthetic grid cell firing fields affect the geometry and topology of their corresponding neural manifolds (tori). It compares original, diffused, attracted, and band units, illustrating how these changes impact the manifold’s shape, size, and topology using PCA, MDS, and TDA.

read the caption

Figure 3: Relating firing fields to neural manifolds across deformations in synthetic grid cells. We investigate how deformations away from perfect hexagonal symmetry in the firing fields of synthetic grid cells affects the geometry of the toroidal neural manifold. From left to right. Original units. The original hexagonal grid cells show clear signatures of toroidal topology, as indicated by the presence of 2 loops in the first homology group (H1) and 1 void in the second homology group (H2). We show 2D projections using principal components analysis (PCA) and multidimensional scaling (MDS) to serve as baselines against which to compare the manifolds of deformed grid cells. PCA projections are consistent with a 'flat' torus geometry. Diffused units. Diffused units created from convolution of the original grid cells with a Gaussian kernel maintain toroidal topology, but PCA and MDS show that the size of the neural manifold is reduced as predicted by theory. Attracted units. Inspired by experimental evidence from [15] we created attracted units from synthetic grid cells by applying a diffeomorphism to the 2D environment. While manifold size is unchanged, PCA projections suggest the torus becomes more curved in neural state space. Toroidal topology is preserved. Band units. We created a synthetic module with 17% of original grid units replaced with band units of same spatial scale, with uniformly distributed orientations. The geometry and topology of the resulting manifold are largely unchanged.

🔼 This figure shows how the geometry of grid cell module tori changes in the presence of salient features in the environment. Panel A illustrates a scenario with uniform saliency, where canonical grid cells develop hexagonal lattice responses, and the population activity forms a torus in neural state space. Panel B demonstrates the impact of rewards (high saliency areas) on the grid cell responses. The introduction of rewards leads to geometric deformations of the neural tori.

read the caption

Figure 2: Geometry of grid cell module tori is changed by presence of salient features in the environment. A. An agent (for us, a piRNN) is trained to perform path integration in its 2D environment with uniform spatial saliency. Canonical grid cells develop hexagonal lattice responses (rate maps) across M modules. The population activity of a single grid cell module forms a torus in neural state space. B. The same agent undergoes a second phase of training, with its environment now containing rewards (areas of high importance, or saliency). We model this saliency by modifying the loss of our piRNN to prioritize accurate position decoding near rewards. Its grid cells adjust their individual responses, which we link to geometric deformations of the neural tori.

More on tables

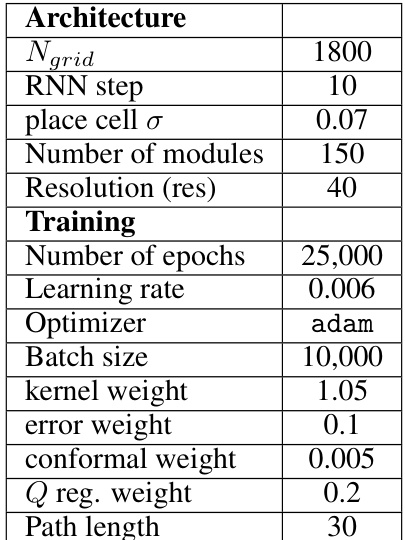

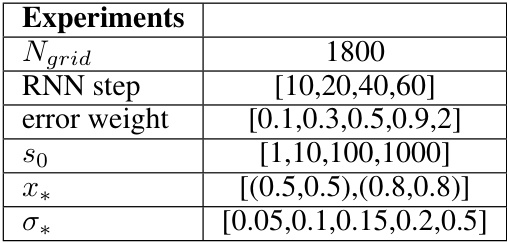

🔼 This table lists the different hyperparameters used in the experiments. These parameters were varied systematically to explore their effect on the model’s behavior. The parameters include the number of grid cells (Ngrid), RNN step size, the error weight in the loss function, the initial saliency (s0), the location of the reward (x*), and the standard deviation of the saliency Gaussian (σ*).

read the caption

Table 2: Different experimental conditions.

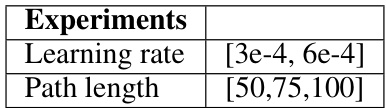

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters that were tested for saliency training in the experiments. The hyperparameters explored include the learning rate and the path length. Various values for each hyperparameter were used to determine optimal settings for the training process.

read the caption

Table 3: Hyperparameter search for saliency training.

Full paper#