TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs), despite their impressive performance, surprisingly struggle with simple tasks like counting and copying. This paper investigates why. It reveals a critical issue: information over-squashing. This means that, due to the architecture of LLMs, earlier information in a sequence gets ‘squashed’ and overwhelmed by later input, hindering the model’s ability to handle long sequences or complex operations effectively. Also, limited floating-point precision in LLMs worsens this effect, resulting in inaccurate outputs. The paper provides a detailed theoretical analysis of these issues, backing it up with empirical evidence from existing LLMs.

This paper proposes simple solutions to address the information loss issues. The researchers show that by introducing additional elements (like commas) to break up long sequences of repeated items, they can successfully improve LLM accuracy on tasks they originally struggled with. The paper presents these findings as a stepping stone for improving future LLM designs. The theoretical analysis helps researchers to understand the limitations of LLMs, leading to improvements in LLM architecture and training methods. The suggested simple solutions, while effective, still highlight the need for more sophisticated solutions to fully resolve information over-squashing in large language models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals fundamental limitations in the architecture of large language models (LLMs). It challenges the assumption of their limitless capacity and proposes actionable solutions. Understanding these limitations is vital for improving future LLM design and preventing unexpected failures in real-world applications. The insights regarding information over-squashing and representational collapse offer new avenues for research and will likely impact the design of future LLMs.

Visual Insights#

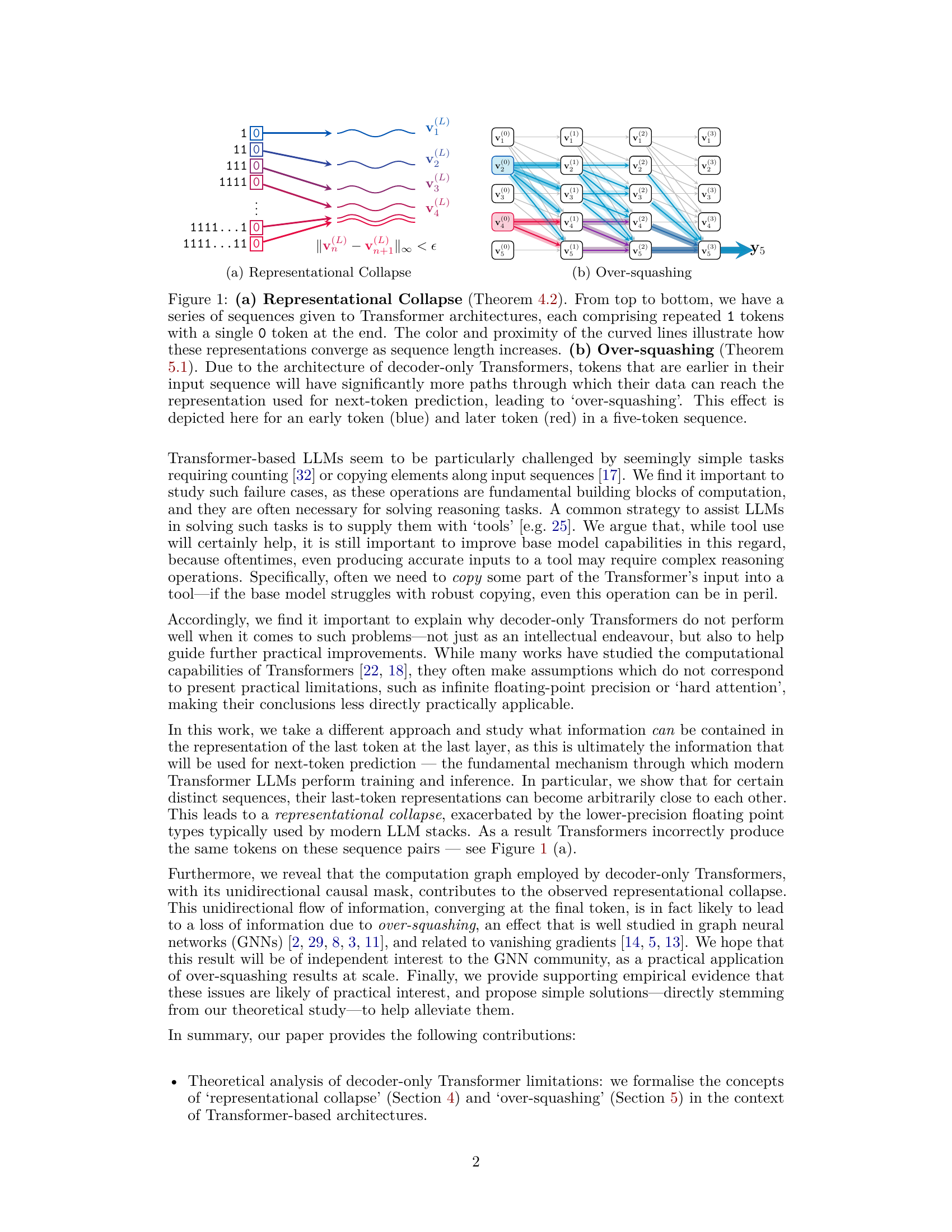

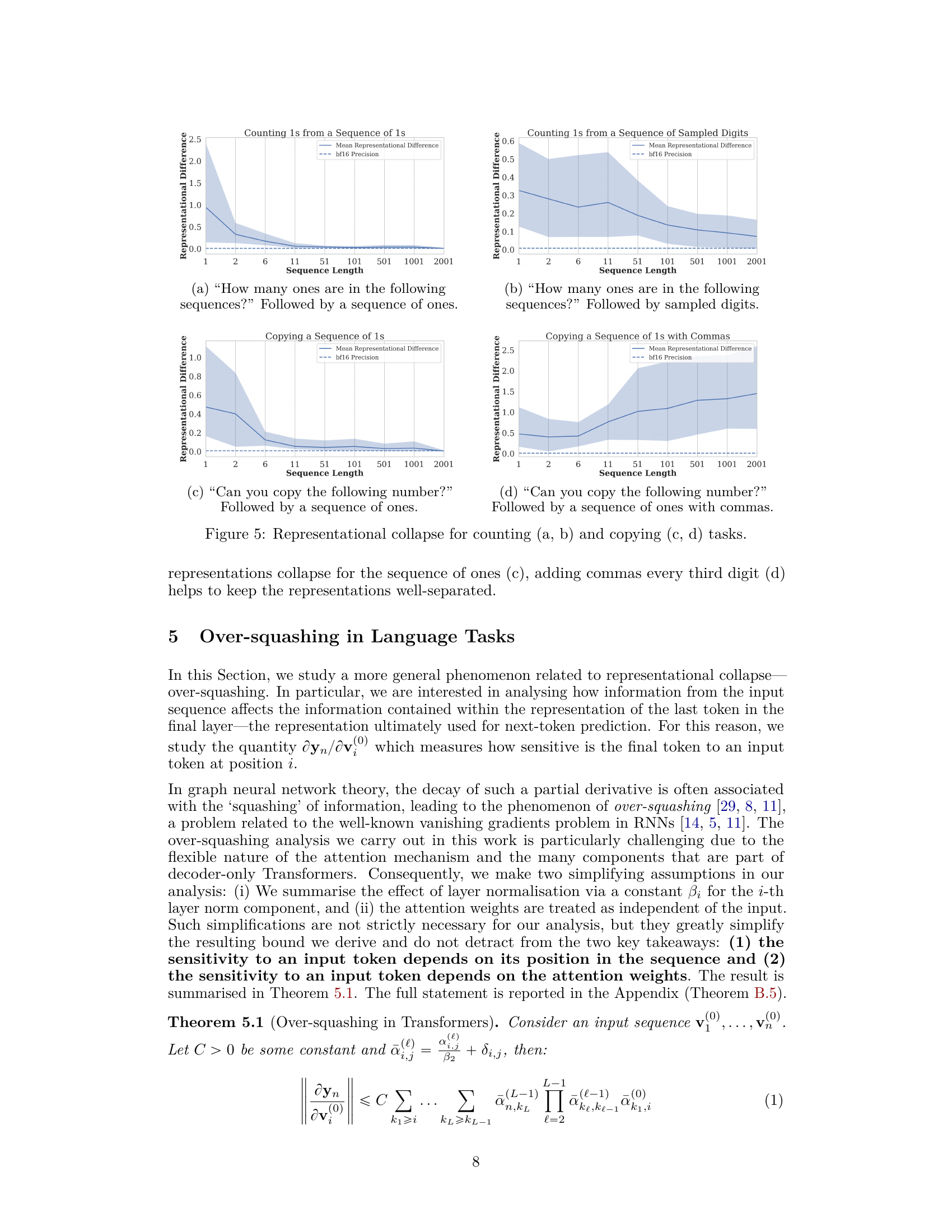

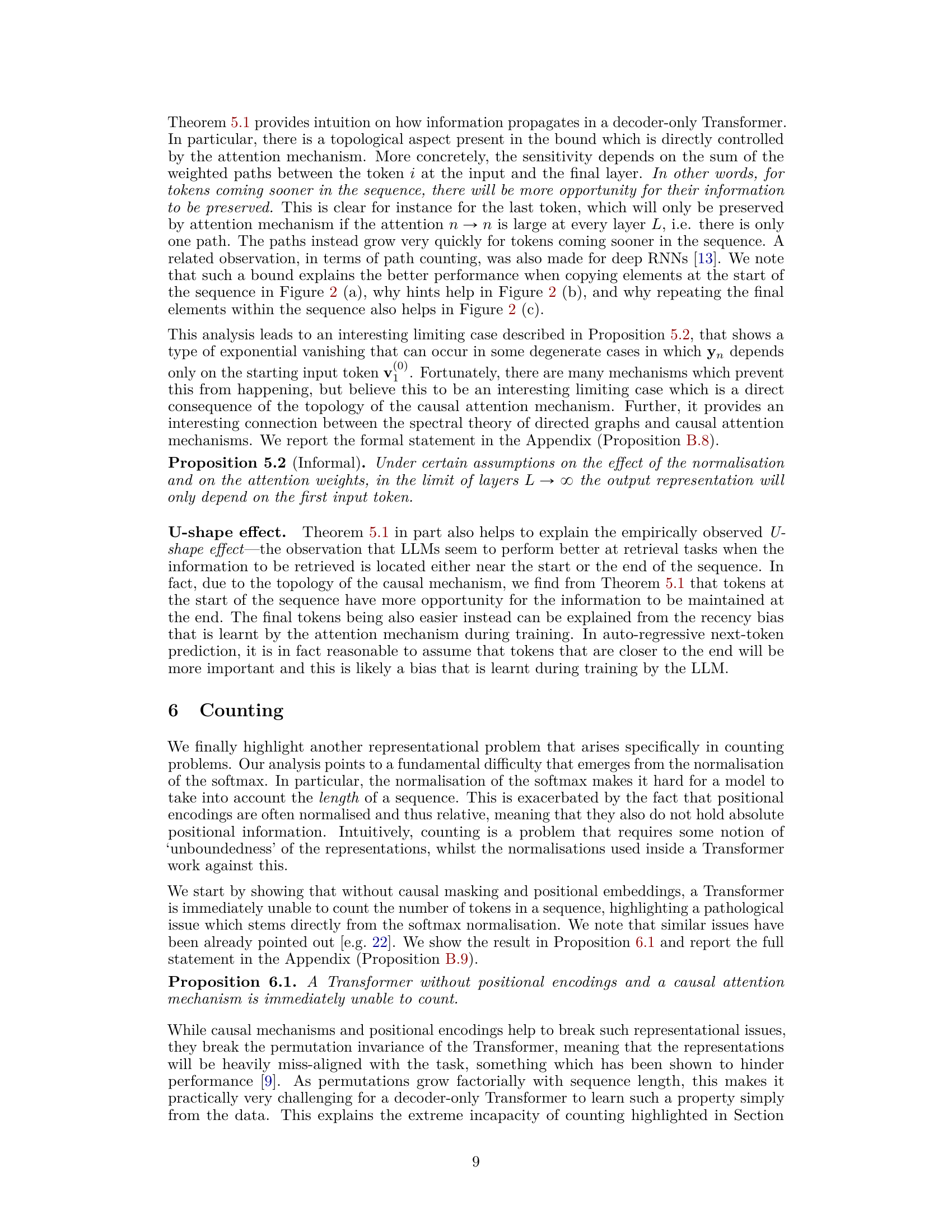

🔼 This figure illustrates two key concepts discussed in the paper: representational collapse and over-squashing. (a) shows how the representations of sequences with increasing numbers of repeated ‘1’ tokens, followed by a single ‘0’, converge in the final layer of a Transformer model. This convergence is problematic because it means that the model cannot distinguish between these sequences, resulting in errors when performing tasks like counting. (b) depicts over-squashing, where earlier tokens in a sequence have more influence on the final token’s representation because of the unidirectional nature of the Transformer architecture. The figure highlights how this uneven distribution of influence can affect the model’s performance.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) Representational Collapse (Theorem 4.2). From top to bottom, we have a series of sequences given to Transformer architectures, each comprising repeated 1 tokens with a single 0 token at the end. The color and proximity of the curved lines illustrate how these representations converge as sequence length increases. (b) Over-squashing (Theorem 5.1). Due to the architecture of decoder-only Transformers, tokens that are earlier in their input sequence will have significantly more paths through which their data can reach the representation used for next-token prediction, leading to 'over-squashing'. This effect is depicted here for an early token (blue) and later token (red) in a five-token sequence.

In-depth insights#

Repr. Collapse#

The concept of “Repr. Collapse,” or representational collapse, as discussed in the research paper, centers on a critical information loss phenomenon within Transformer models. The core idea is that distinct input sequences can converge to nearly identical final representations, especially under the constraints of low-precision arithmetic commonly used in large language models (LLMs). This collapse happens because of how information propagates through the Transformer’s architecture and is exacerbated by the low-precision numerical formats. This means the model loses the ability to distinguish between these sequences, leading to errors in tasks requiring fine-grained distinctions, such as counting or sequence copying. The theoretical analysis reveals that this collapse is not simply a practical limitation but a fundamental representational constraint stemming from the model’s architecture and precision limitations. The authors propose theoretical solutions to mitigate this representational collapse, emphasizing the need for higher precision and strategies to ensure diverse representations for similar inputs.

Over-squashing#

The concept of ‘over-squashing’ in the context of the research paper refers to a phenomenon where the sensitivity of the final token’s representation to earlier tokens in a sequence diminishes drastically. This is a critical issue, especially in decoder-only transformer models which process information sequentially. The unidirectional nature of these models, combined with the inherent challenges of propagating information across long sequences, exacerbates this phenomenon. The theoretical analysis likely highlights the role of attention mechanisms and the specific architectural design in contributing to over-squashing. It’s probable that the analysis demonstrates how information from early tokens gets ‘squashed’ or lost as it propagates through the layers, leading to a reduced ability of the model to distinguish between sequences that differ only in their earlier positions. The authors likely provide evidence illustrating the impact of this over-squashing on downstream tasks and suggest potential mitigation strategies to alleviate this information loss, such as incorporating mechanisms to enhance information flow or adjusting the architectural design.

LLM Copying Limits#

The heading “LLM Copying Limits” suggests an exploration into the boundaries of large language models’ (LLMs) ability to accurately replicate input sequences. This is a crucial area of research because copying is a fundamental building block of more complex reasoning tasks. The study likely investigates why seemingly simple copying tasks pose significant challenges for LLMs. This could involve analyzing the impact of factors such as sequence length, the presence of distractor elements, and the model’s internal attention mechanisms. A key insight might be the revelation of information loss or over-squashing within the transformer architecture, hindering the precise propagation of information needed for accurate replication. The research likely provides empirical evidence demonstrating these limitations through experiments on contemporary LLMs, highlighting the practical implications of these “copying limits.” Ultimately, the findings could contribute to a deeper understanding of LLM capabilities and inspire the development of strategies to mitigate these limitations, potentially through architectural modifications or improved training techniques. The research would likely propose methods or improvements to address the identified copying limits, perhaps focusing on enhancing the model’s memory capacity or refining its attention mechanisms to better preserve information throughout processing.

Counting Failures#

The hypothetical heading ‘Counting Failures’ in a research paper likely explores the shortcomings of large language models (LLMs) in performing tasks involving counting operations. A thoughtful analysis would examine various aspects: the limitations of existing transformer architectures, which may struggle with precise numerical reasoning; the impact of low-precision floating-point arithmetic, potentially leading to inaccurate calculations and error propagation; the influence of tokenization, where the representation of numbers can affect the ability of an LLM to count correctly; and the effects of attention mechanisms, as the model might fail to appropriately weigh all the input tokens relevant for the counting task. The paper could further investigate the relative difficulty of counting different types of numbers (e.g., whole numbers versus decimals, small versus large numbers); and the ways in which external knowledge or prompting strategies could improve the LLMs’ counting accuracy. Overall, this section would provide crucial insight into the robustness and limitations of current LLMs, pointing to directions for future research in enhancing their numerical reasoning capabilities.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for extending the current findings on representational collapse and over-squashing in transformer-based LLMs. A crucial next step is a more rigorous mathematical treatment of RoPE (Rotary Positional Embeddings), particularly examining its impact on representational collapse under various conditions. This requires a deeper dive into the complex interactions between positional embeddings and the attention mechanism. Further investigation into the practical implications of low floating-point precision is vital, focusing on the development of mitigation strategies that can alleviate representational collapse without sacrificing computational efficiency. The study could also explore the effects of tokenization on representational collapse and over-squashing, examining how different tokenization schemes impact the flow of information. Investigating the impact of different architectures, such as those employing local attention mechanisms or alternative architectures entirely, would be particularly insightful. This would reveal whether the observed phenomena are inherent limitations of the transformer architecture or artifacts of specific design choices. Finally, extending the theoretical analysis and empirical evaluation to a wider range of LLMs and tasks is essential for solidifying the generalizability of the current findings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure shows the results of three different copying tasks performed using the Gemini language model. The first task involves copying either the first or last token from a sequence of 1s and 0s of varying lengths. The second task is similar to the first, but includes hints to aid the model. The third task uses sequences with interleaved 1s and 0s. The results highlight the challenges faced by the model in these tasks, particularly with longer sequences and when attempting to copy the last token.

read the caption

Figure 2: Results on simple copying tasks. (a). Gemini was prompted to predict the last token (diamond) of a sequence ‘1...10’ or the first token (square) of a sequence ‘01...1’. (b). Same as (a) but with hints (see 3.2 for details) (c). Same as (a) but the sequences have interleaved 0s and 1s. See C.1 for extra details

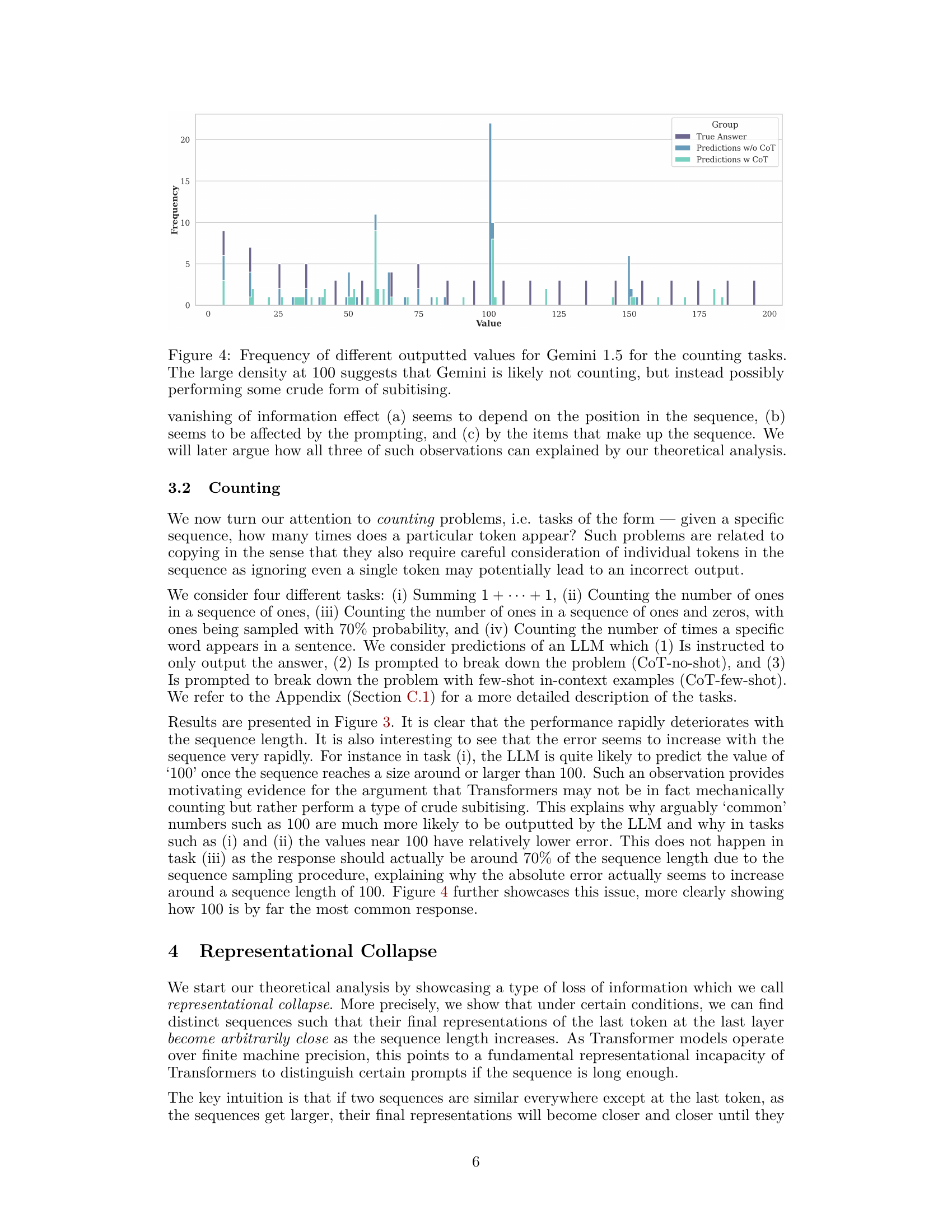

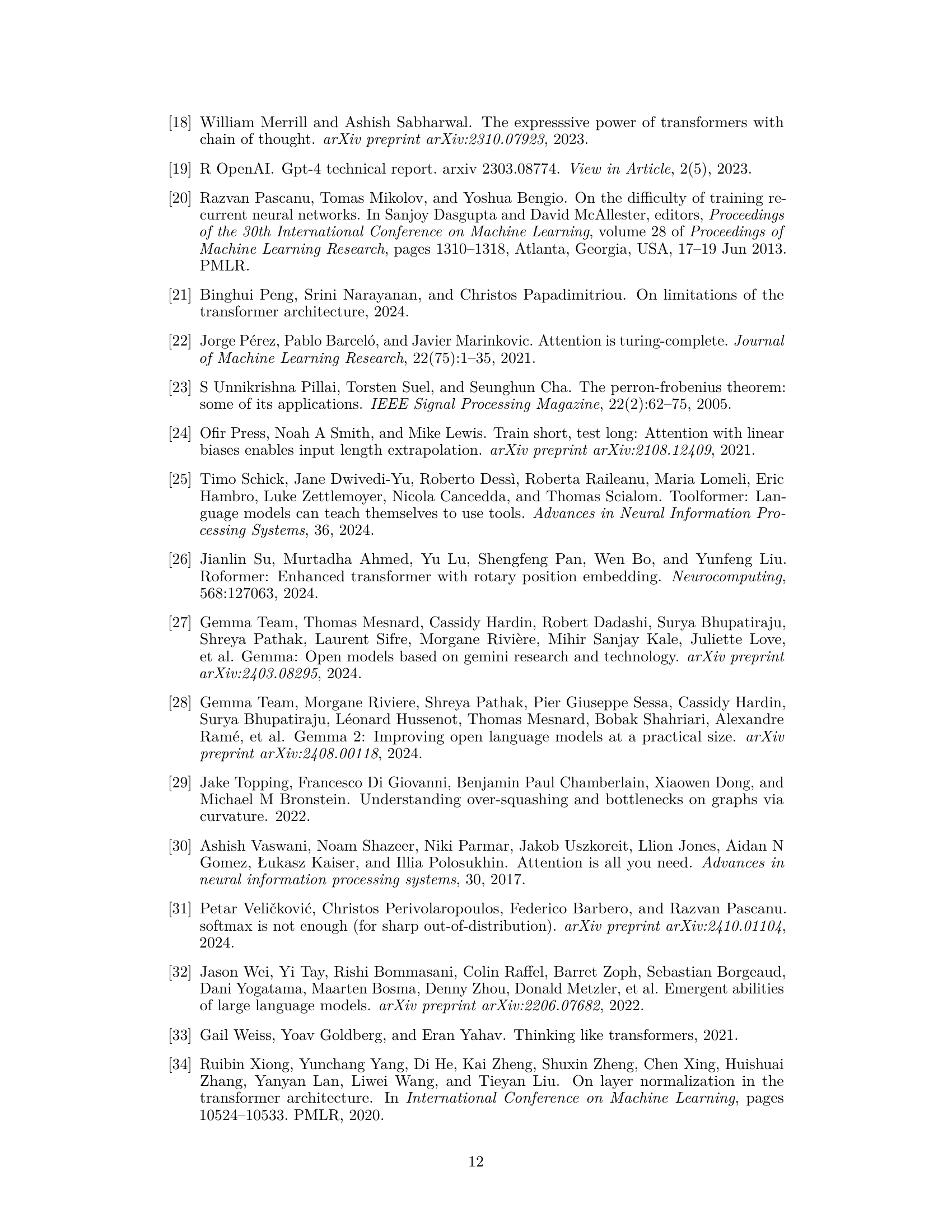

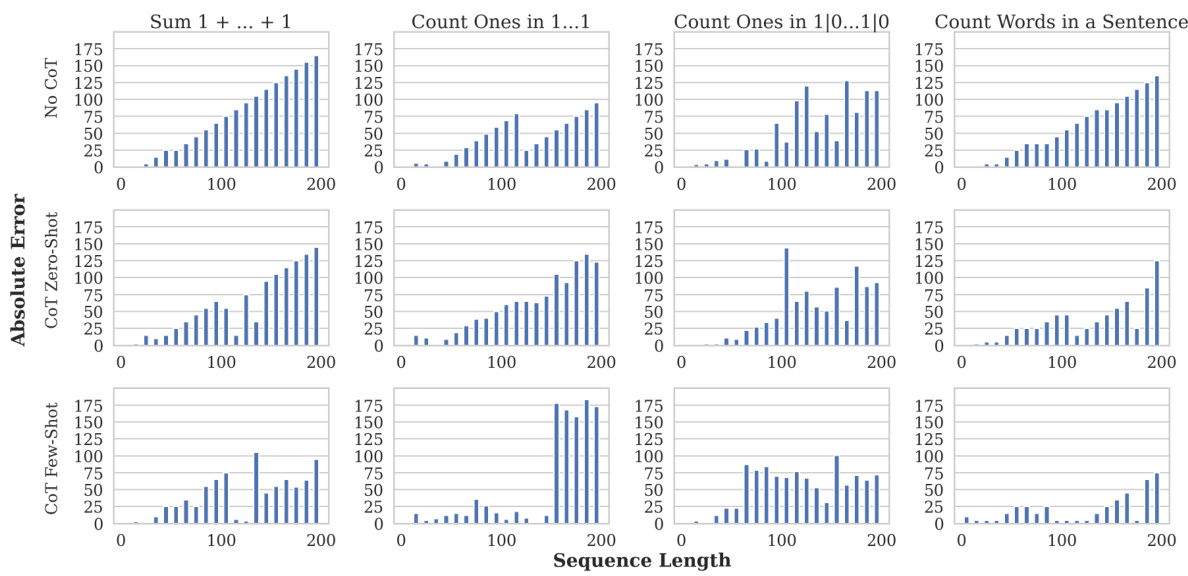

🔼 The figure displays the results of four counting tasks performed by the Gemini 1.5 language model. Each task involves counting something different, ranging from summing consecutive ones to counting word occurrences in sentences. The x-axis represents the length of the sequence or sentence, while the y-axis shows the absolute error. The figure shows how the model’s accuracy decreases as the sequence length increases in all four tasks. The different colored bars in each column represent different prompting strategies.

read the caption

Figure 3: Gemini 1.5 being prompted to sum 1 + … + 1 (Column 1), Count the number of ones in a sequence of 1s (Column 2), Count the number of ones in a sequence of ones and zeroes (the sequence is a Bernoulli sequence with probability of sampling a one being 0.7) (Column 3), and to counter the number of times a word appears in a sentence (Column 4).

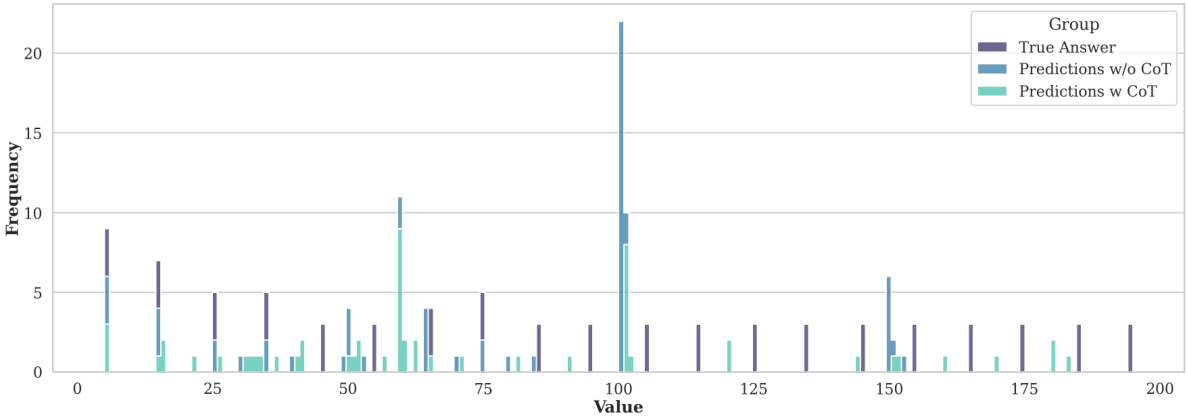

🔼 This figure shows the frequency of different outputs generated by the Gemma 7B language model for three counting tasks: summing a sequence of 1s, counting ones in a sequence of 1s, and counting ones in a sequence of 1s and 0s. The results highlight the model’s tendency to produce incorrect answers, especially for longer sequences, and demonstrate the phenomenon of representational collapse discussed in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 7: Frequency of different outputs for Gemma 7B

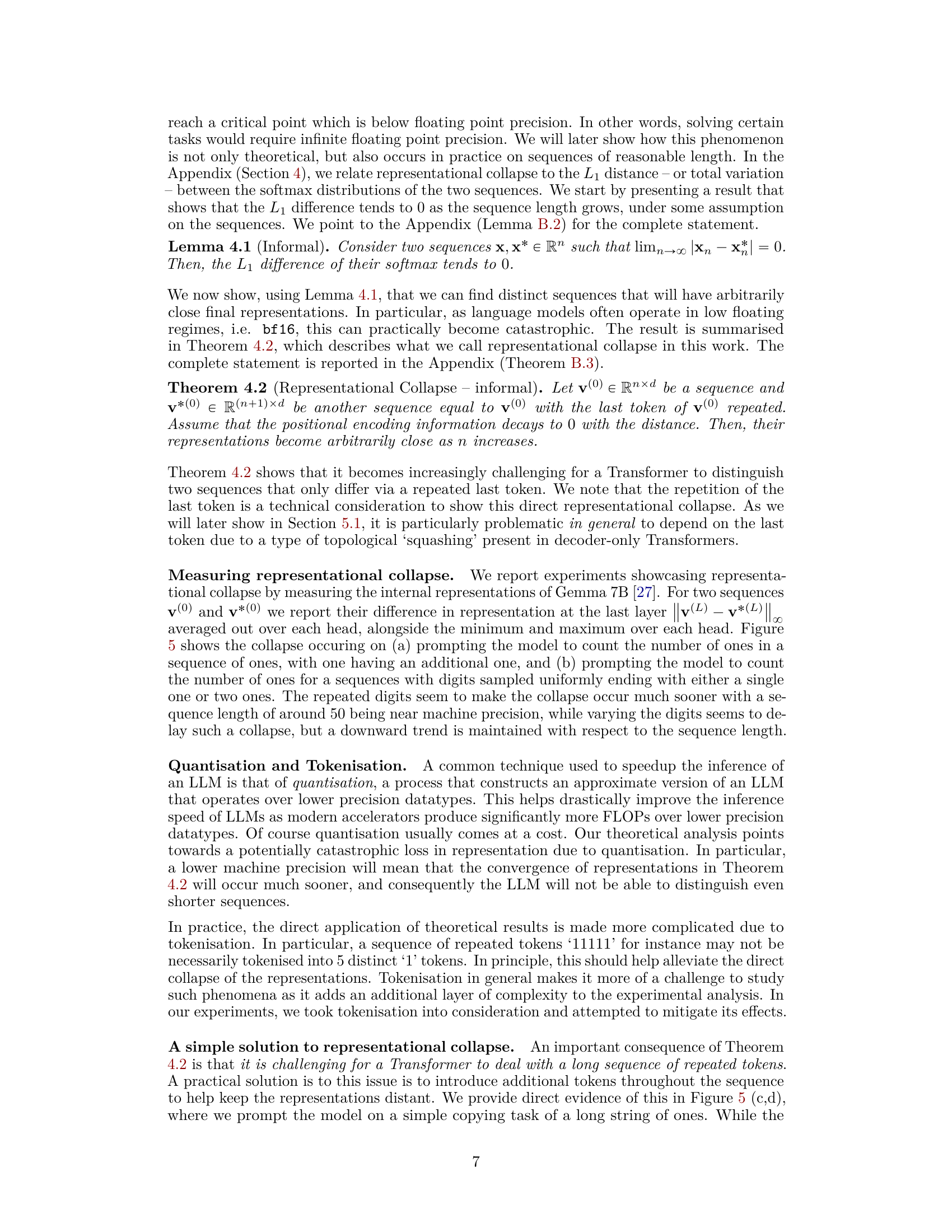

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments that measure the representational collapse phenomenon in a transformer model for counting and copying tasks. The plots show the mean representational difference (with error bars) between the final token representations of pairs of similar sequences, as a function of sequence length. The pairs of sequences differ only in the last token (or one of the last tokens). For counting, two types of experiments are conducted: counting 1s in a sequence of 1s, and counting 1s in sequences of randomly sampled 0s and 1s. The copying tasks involve copying a sequence of 1s, and copying a sequence of 1s with commas inserted every third digit. The results show that for longer sequences, the representational difference decreases significantly, approaching machine precision. The addition of commas in the copying task mitigates this representational collapse.

read the caption

Figure 5: Representational collapse for counting (a, b) and copying (c, d) tasks. representations collapse for the sequence of ones (c), adding commas every third digit (d) helps to keep the representations well-separated.

🔼 This figure displays the results of experiments conducted using Gemini 1.5, a large language model (LLM), on four different counting tasks. The tasks involved adding a sequence of ones, counting the number of ones in sequences of ones, counting the number of ones in a mixed sequence of ones and zeros (Bernoulli sequence with p=0.7), and counting the occurrences of a specific word in a sentence. The x-axis represents sequence length, while the y-axis represents the absolute error in the predictions. The figure shows the results for three different prompting strategies: no Chain-of-Thought (CoT), CoT zero-shot, and CoT few-shot. The results highlight the limitations of LLMs in handling simple counting tasks, particularly as sequence length increases.

read the caption

Figure 3: Gemini 1.5 being prompted to sum 1 + … + 1 (Column 1), Count the number of ones in a sequence of 1s (Column 2), Count the number of ones in a sequence of ones and zeroes (the sequence is a Bernoulli sequence with probability of sampling a one being 0.7) (Column 3), and to counter the number of times a word appears in a sentence (Column 4).

🔼 This figure shows the frequency distribution of different outputs generated by the Gemma 7B language model for three counting tasks: summing 1+…+1, counting ones in a sequence of 1s, and counting ones in a sequence of ones and zeros. The figure visually demonstrates the model’s tendency to produce inaccurate counts, especially as sequence length increases, highlighting a key failure mode discussed in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 7: Frequency of different outputs for Gemma 7B

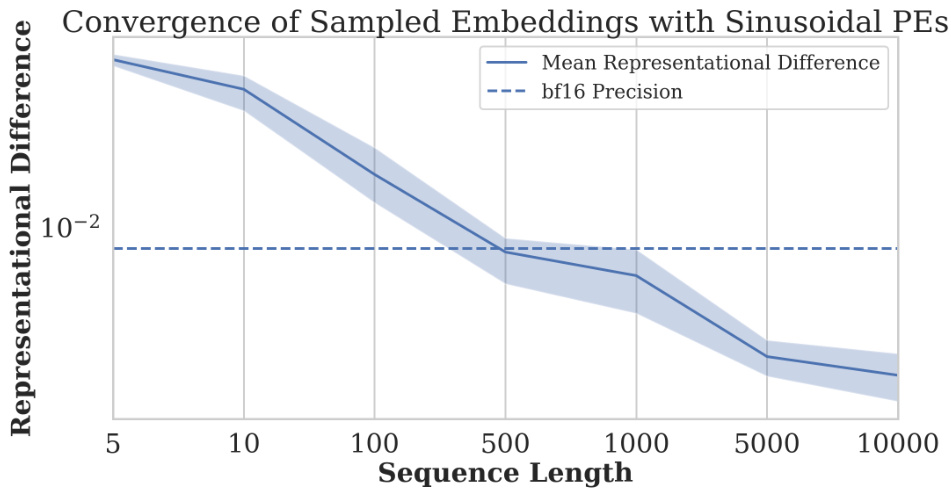

🔼 This figure shows the results of a synthetic experiment to demonstrate representational collapse using sinusoidal positional encodings. Key, query, and value vectors were sampled from a Gaussian distribution, and the standard sinusoidal positional embeddings from the original Transformer paper were applied. The plot shows the mean representational difference between the final token representations of sequences of length n and n+1 (where the n+1 sequence is identical to the n sequence except for a repeated final token), as the sequence length n increases. The y-axis uses a logarithmic scale.

read the caption

Figure 8: Convergence behaviour with a synthetic Transformer experiment. We sample the key, query, and values from a Gaussian distribution and apply the traditional sinusoidal PEs from [30]. We apply a logarithmic scale on the y-axis.

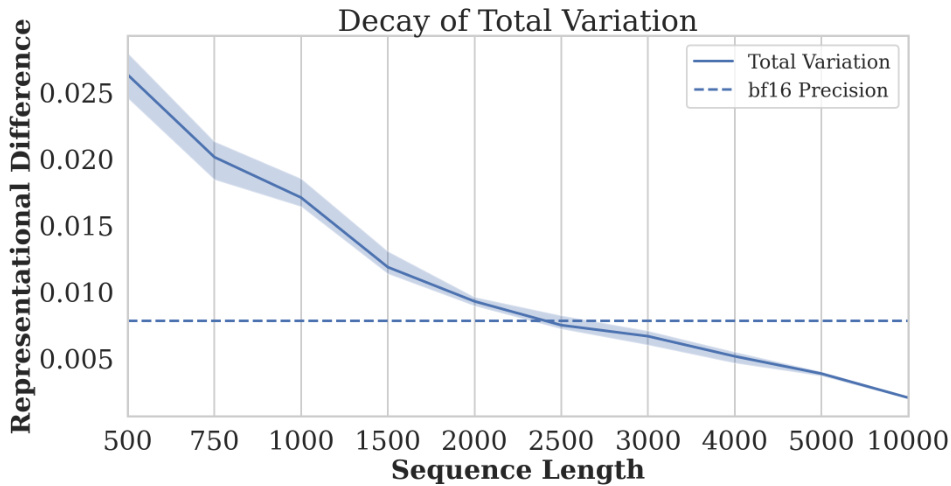

🔼 This figure shows the decay of total variation between softmax distributions of two sequences as the sequence length increases. One sequence is sampled uniformly from [0,1], and the other sequence is created by adding noise to the first 200 elements of the first sequence. The plot demonstrates that the total variation decreases as the sequence length increases, supporting Lemma B.2 in the paper which shows that the total variation between two softmax distributions tends to zero as the length of the sequences increases.

read the caption

Figure 9: Total variation decay of softmax distributions with growing sequence length. We sample n elements uniformly from [0, 1] and then create a related sequence by taking its first k = 200 and adding to these elements noise sampled uniformly from [0,0.1]. We measure the total variation between their softmax distributions. It is clear how the total variation decays with length, in accordance with Lemma B.2. Error bars show minimum and maximum over 5 seeds.

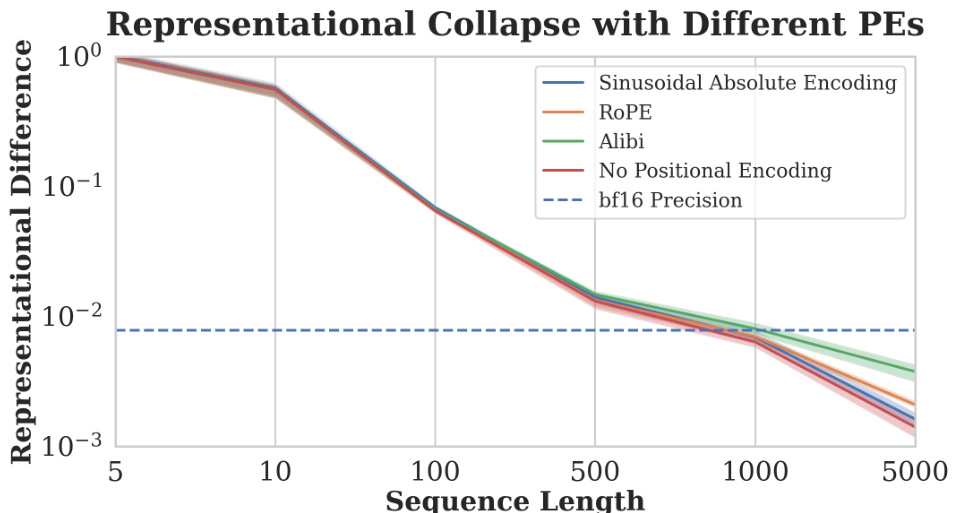

🔼 This figure shows the results of an experiment designed to test the impact of different positional encodings on the representational collapse phenomenon in Transformer models. The experiment uses a simplified Transformer architecture with a single attention head and layer normalization. The x-axis represents the sequence length, and the y-axis represents the L₁ distance between the final token representations of two sequences: one of length n, and the other of length n+1 (where the last token is repeated). The different lines represent the results obtained with different positional encodings (Sinusoidal Absolute Encoding, ROPE, Alibi, No Positional Encoding), as well as the effect of bf16 precision.

read the caption

Figure 10: We sample n queries, keys, and values independently from a standard Gaussian, applying different positional encodings. We then construct sequences of length n + 1, by repeating the n-th token. We report the L₁ distance between the last tokens of the sequences of length n and n + 1 after one decoder-only Transformer layer. We set the hidden dimension to 64, use a single attention head, and normalise appropriately to simulate the effects of LayerNorm. The y-axis is shown in log-scale.

🔼 This figure illustrates two phenomena in decoder-only Transformers: representational collapse and over-squashing. (a) shows how the final representation of sequences of repeated ‘1’s ending in a ‘0’ converges as the sequence length increases, demonstrating representational collapse. The different colored lines represent distinct sequences becoming indistinguishably close in representation. (b) depicts over-squashing, where tokens earlier in the sequence have a disproportionately large influence on the final token’s representation due to the unidirectional information flow in decoder-only architectures.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) Representational Collapse (Theorem 4.2). From top to bottom, we have a series of sequences given to Transformer architectures, each comprising repeated 1 tokens with a single 0 token at the end. The color and proximity of the curved lines illustrate how these representations converge as sequence length increases. (b) Over-squashing (Theorem 5.1). Due to the architecture of decoder-only Transformers, tokens that are earlier in their input sequence will have significantly more paths through which their data can reach the representation used for next-token prediction, leading to 'over-squashing'. This effect is depicted here for an early token (blue) and later token (red) in a five-token sequence.

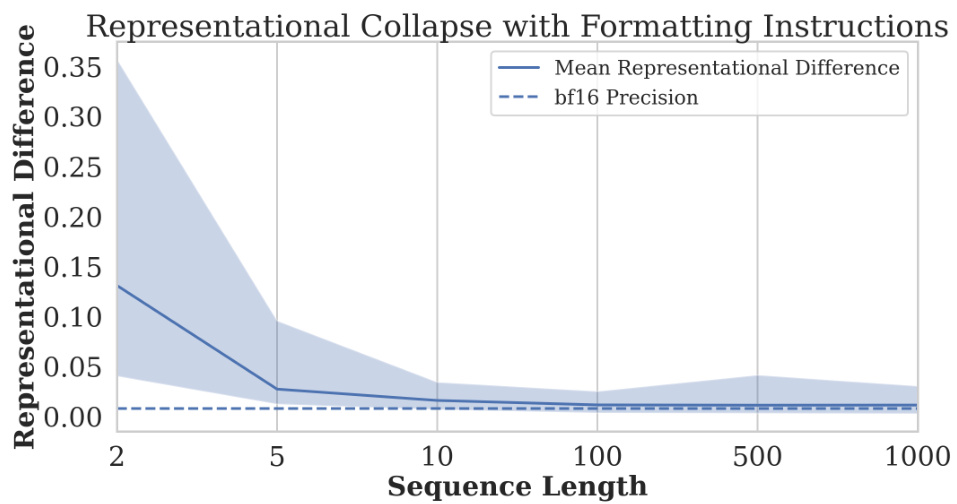

🔼 This figure shows the representational collapse phenomenon in the Gemma language model using two different prompt types. Type 1 requests the last digit directly, while Type 2 requests it indirectly. The y-axis represents the representational difference between sequences of different lengths but with similar structures. The x-axis shows the sequence length. As the length increases, the representational difference decreases, demonstrating representational collapse. The horizontal dashed line indicates the bf16 precision limit.

read the caption

Figure 12: Representational collapse in Gemma for the prompt: 'What is the last digit of the following sequence? Please answer exactly as ‘The answer to your question is:''. Here is the sequence: {seq} and (Type 2)

Full paper#