TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) have shown impressive performance on multimodal tasks even without specific multimodal training. However, a clear understanding of why this occurs is still lacking, prompting researchers to explore the mechanisms underlying this capability and to develop more effective and efficient large multimodal models (LMMs). Previous hypotheses suggest that perceptual information is translated into textual tokens or that LLMs utilize modality-specific subnetworks.

This research investigates the internal representations of frozen LLMs when processing various multimodal inputs (image, video, audio, and text). The study reveals a novel “implicit multimodal alignment” effect. The findings indicate that while perceptual and textual tokens reside in distinct representation spaces, they activate similar LLM weights and become implicitly aligned during both training and inference. This alignment, linked to the LLM’s architecture, is shown to correlate with task performance and is inversely related to hallucinations. These discoveries lead to practical improvements in LMM efficiency and model evaluation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on large multimodal models because it provides a deeper understanding of how frozen LLMs generalize to multimodal inputs. This knowledge is essential for developing more efficient and effective LMMs, advancing current trends in AI research.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure summarizes the key findings and implications of the research paper. The leftmost panel shows the analysis of multimodal tokens within Large Language Models (LLMs), revealing that these tokens reside in distinct, multimodal ‘cones’ in the embedding space, despite being implicitly aligned. The central panel illustrates the LLM architecture as a residual stream with ‘steering blocks’ that facilitate this implicit multimodal alignment (IMA). The rightmost panel highlights the practical implications of this alignment, categorized into performance, safety, and efficiency aspects. The performance and safety implications are connected to the implicit alignment score (IMA) and the model’s accuracy and tendency to hallucinate. The computational efficiency implications include LLM compression and methods to reduce computational costs by skipping calculations for specific parts of the model.

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

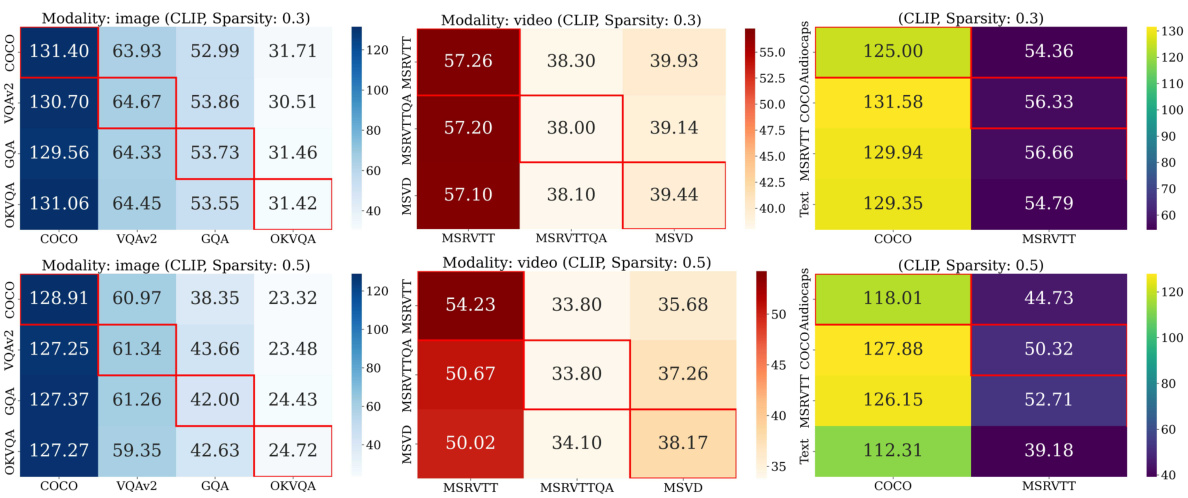

🔼 This table shows the Implicit Multimodal Alignment (IMA) score and the performance of different image encoders on various tasks using the OPT model with a single-task setup. The higher the IMA score, the better the performance, indicating a strong positive correlation between alignment and task performance. The CLIP-ViT-L encoder shows the highest IMA score and the best overall performance.

read the caption

Table 1: IMA score across different encoders. We report the IMA score and the task performance with the ST setup (OPT). A positive correlation exists between IMA score and the performance; the most aligned encdoers (CLIP) have the best accuracy/CIDEr on VQA and captioning tasks.

In-depth insights#

Frozen LLM Power#

The concept of “Frozen LLM Power” highlights the surprising effectiveness of large language models (LLMs) when their weights are frozen and only a small, trainable adapter module is used to interface them with other modalities. This approach demonstrates significant efficiency gains, requiring far fewer parameters and training data than full fine-tuning. The success suggests that LLMs possess a strong inherent inductive bias, capable of generalizing to multimodal tasks despite never having been explicitly trained on them. Further research into the internal mechanisms of this generalization, specifically how different modalities interact and are implicitly aligned within the LLM’s architecture, could reveal valuable insights into LLM design, ultimately leading to more efficient and effective multimodal models. Understanding the “Frozen LLM Power” phenomenon could revolutionize LMM development, particularly for resource-constrained applications.

Multimodal Alignment#

The concept of “Multimodal Alignment” in the context of large language models (LLMs) and their generalization to multimodal inputs is a crucial area of research. The paper investigates how LLMs, primarily designed for text, manage to handle image, audio, and video data effectively. A key finding is the existence of implicit multimodal alignment (IMA), where despite perceptual tokens residing in distinct representational spaces compared to textual tokens, they activate similar LLM weights. This suggests that the LLM’s architecture, potentially through residual streams and steering blocks, plays a significant role in enabling generalization. IMA’s strength correlates positively with task performance, acting as a potential proxy metric for model evaluation. Furthermore, the study demonstrates a negative correlation between IMA and the occurrence of hallucinations, implying misalignment as a leading cause of these errors. This multifaceted analysis reveals the complex interplay between unimodal and multimodal representations within LLMs, paving the way for more efficient inference methods and model compression techniques.

IMA as Proxy Metric#

The concept of using the Implicit Multimodal Alignment (IMA) score as a proxy metric offers a compelling approach to evaluating and potentially streamlining multimodal models. The core insight is that a higher IMA score, reflecting stronger alignment between internal representations of textual and perceptual data within a language model, correlates with improved task performance. This suggests IMA could serve as a more efficient and insightful evaluation metric than relying solely on downstream task accuracy. Furthermore, the connection between IMA and performance suggests potential applications in model selection and design, allowing researchers to prioritize models or architectural choices that promote stronger internal alignment. The findings might also contribute to understanding and mitigating issues like hallucinations, where misalignment between modalities is prominent. By focusing on this internal alignment, researchers can move beyond simply evaluating the outcome and gain a deeper understanding of the model’s internal workings, leading to better models and improved efficiency.

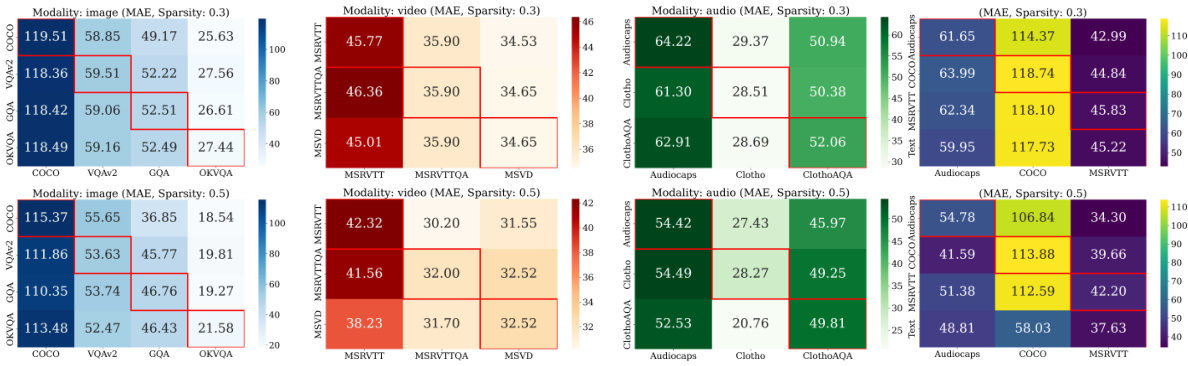

LLM Compression#

LLM compression, in the context of large multimodal models (LMMs), is a crucial area of research focusing on reducing the computational cost and memory footprint of these models. The core idea is to maintain the impressive performance of LLMs on multimodal tasks while significantly reducing the model size. One primary approach involves identifying and leveraging redundancy in the LLM’s weights. The paper’s findings suggest that similar weights are often activated by both textual and perceptual (e.g. visual, audio) inputs. This redundancy allows for compression, where only a subset of the weights (a single ‘a-SubNet’) is needed to perform well across a broad spectrum of multimodal tasks, leading to significant efficiency gains. The success of such compression methods hinges on the implicit multimodal alignment effect (IMA). This suggests that the underlying architectural design of LLMs plays a critical role in facilitating their generalization to multimodal data, which is also leveraged during the compression process. Therefore, architectural choices are key to the success of both LLM generalization to multimodal data and LLM compression. Further research is needed to investigate the scalability of such compression techniques to even larger models and more complex multimodal tasks, while also considering potential trade-offs between model size, computational cost and performance.

Future of LLMs#

The future of LLMs is bright, but multifaceted. Multimodality will be key, with models seamlessly integrating diverse data types (images, video, audio, text) to surpass current limitations. Efficiency gains are crucial; current computational costs prohibit widespread access, necessitating advancements in model compression and more efficient training methods. Safety and alignment concerns demand significant attention, requiring robust techniques to minimize bias, prevent harmful outputs, and ensure human-aligned behavior. Explainability is another pivotal aspect, transitioning from opaque black boxes to more transparent models that provide insights into their decision-making processes. Finally, applications will continue to expand beyond current realms, impacting various fields and necessitating responsible development and deployment strategies. While challenges remain, the potential of LLMs to revolutionize various industries is immense, particularly if these key areas see substantial progress.

More visual insights#

More on figures

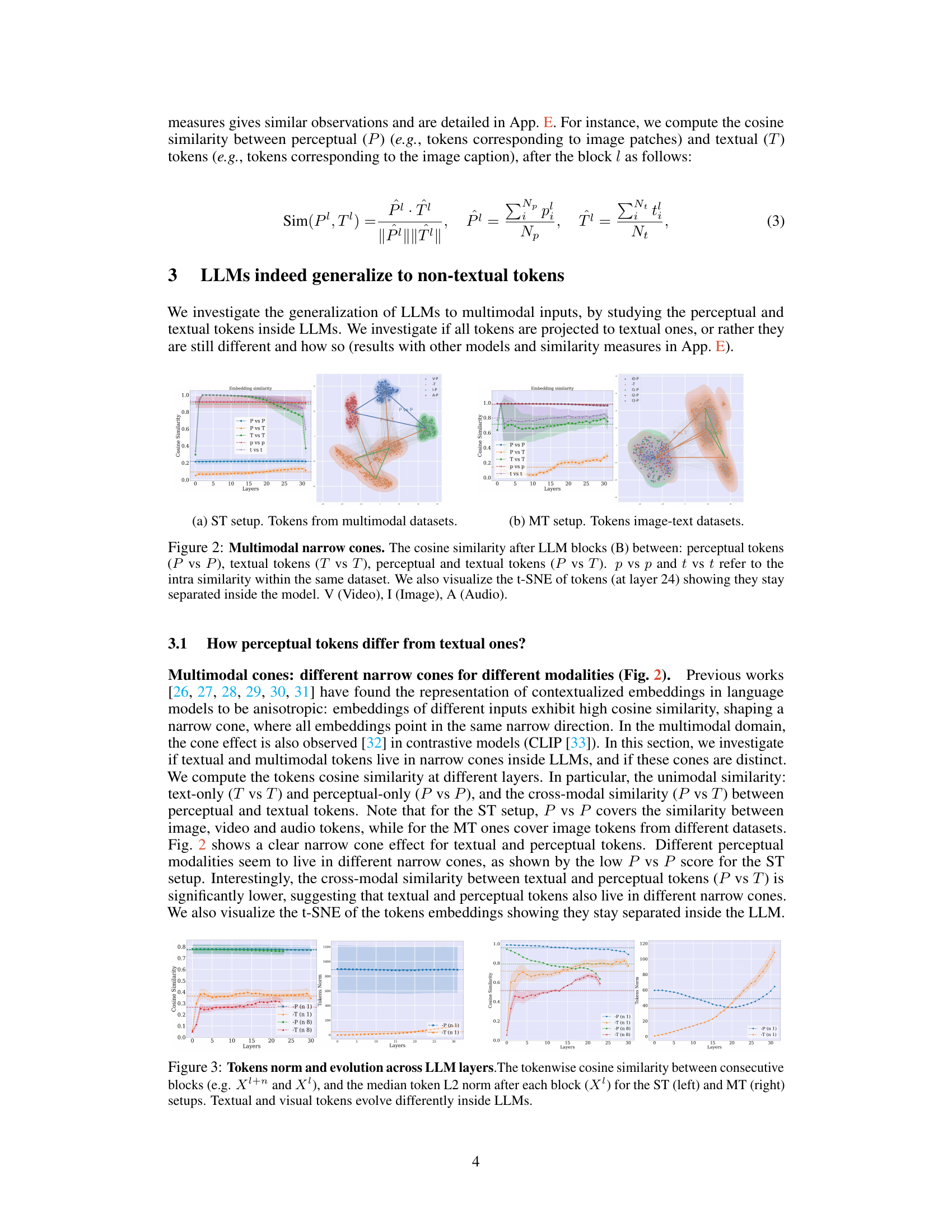

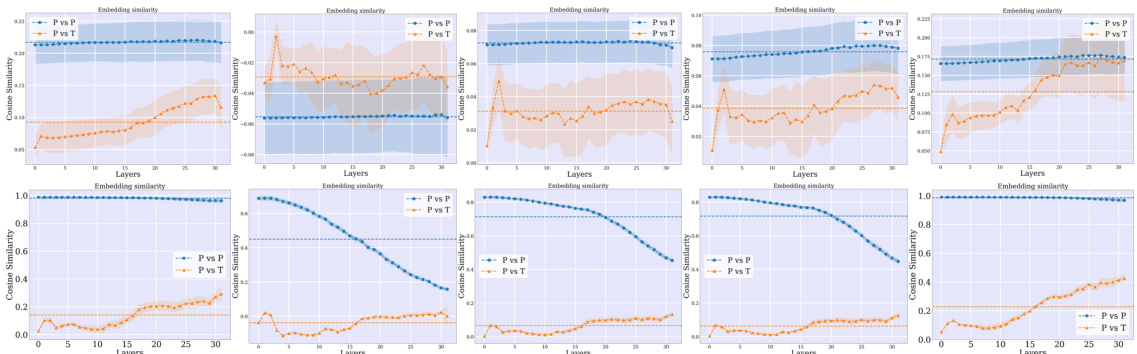

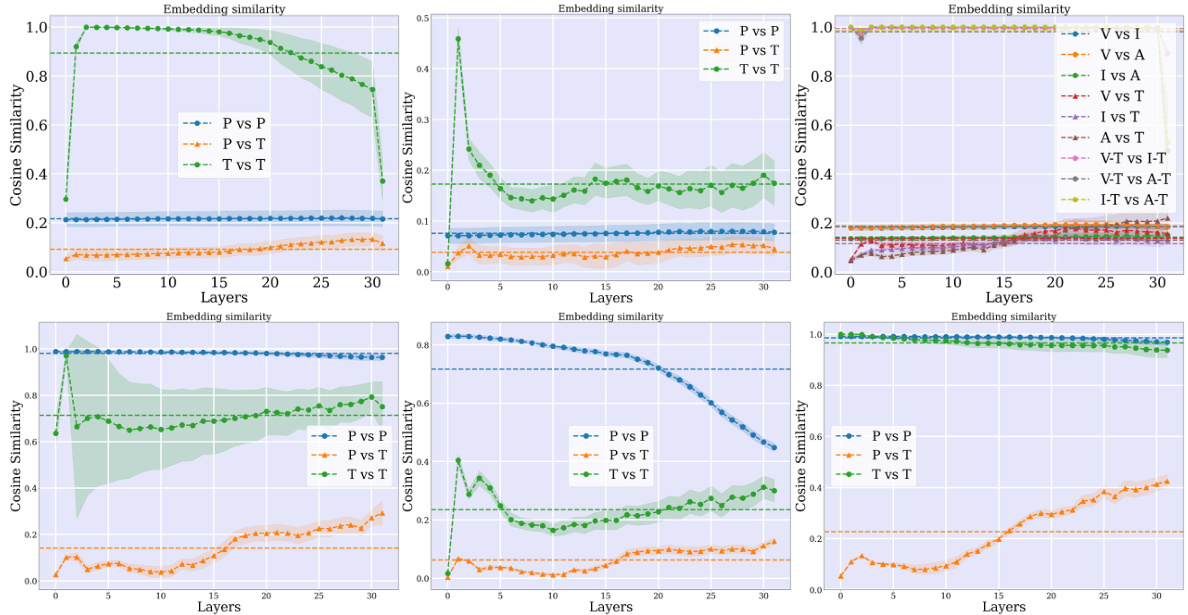

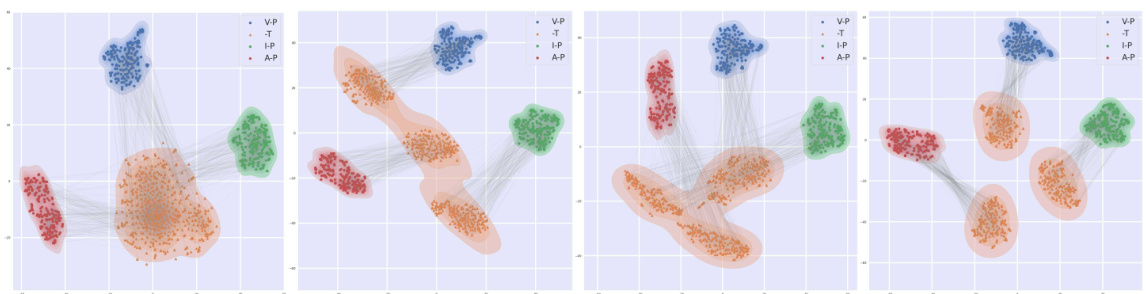

🔼 This figure demonstrates the cosine similarity between different types of tokens (perceptual vs. perceptual, textual vs. textual, and perceptual vs. textual) within a Large Language Model (LLM) across multiple layers. It shows that perceptual tokens from different modalities (image, video, audio) tend to cluster separately, forming distinct ’narrow cones’ in the embedding space. The textual tokens also form their own cluster. The cross-modal similarity (perceptual vs. textual) is noticeably lower than the within-modality similarities, indicating that the representations of perceptual and textual tokens are distinct within the LLM. A t-SNE visualization further confirms this separation of token representations within the model.

read the caption

Figure 2: Multimodal narrow cones. The cosine similarity after LLM blocks (B) between: perceptual tokens (P vs P), textual tokens (T vs T), perceptual and textual tokens (P vs T). p vs p and t vs t refer to the intra similarity within the same dataset. We also visualize the t-SNE of tokens (at layer 24) showing they stay separated inside the model. V (Video), I (Image), A (Audio).

🔼 This figure summarizes the key findings and implications of the research paper. It visually represents the main contributions, starting with the analysis of how multimodal tokens (image, video, audio, and text) are processed within Large Language Models (LLMs). The analysis reveals that these tokens, while existing in distinct representation spaces (illustrated as separate ‘cones’), exhibit an implicit multimodal alignment (IMA). This alignment, driven by the LLM architecture, is visualized as ‘steering blocks’ within a residual stream. The figure then highlights the practical implications of the IMA effect, which include improvements in model performance, enhanced safety (reduction in hallucinations), and increased computational efficiency. These implications are linked to the discovered alignment effect, further strengthening the understanding of how LLMs handle multimodal inputs.

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

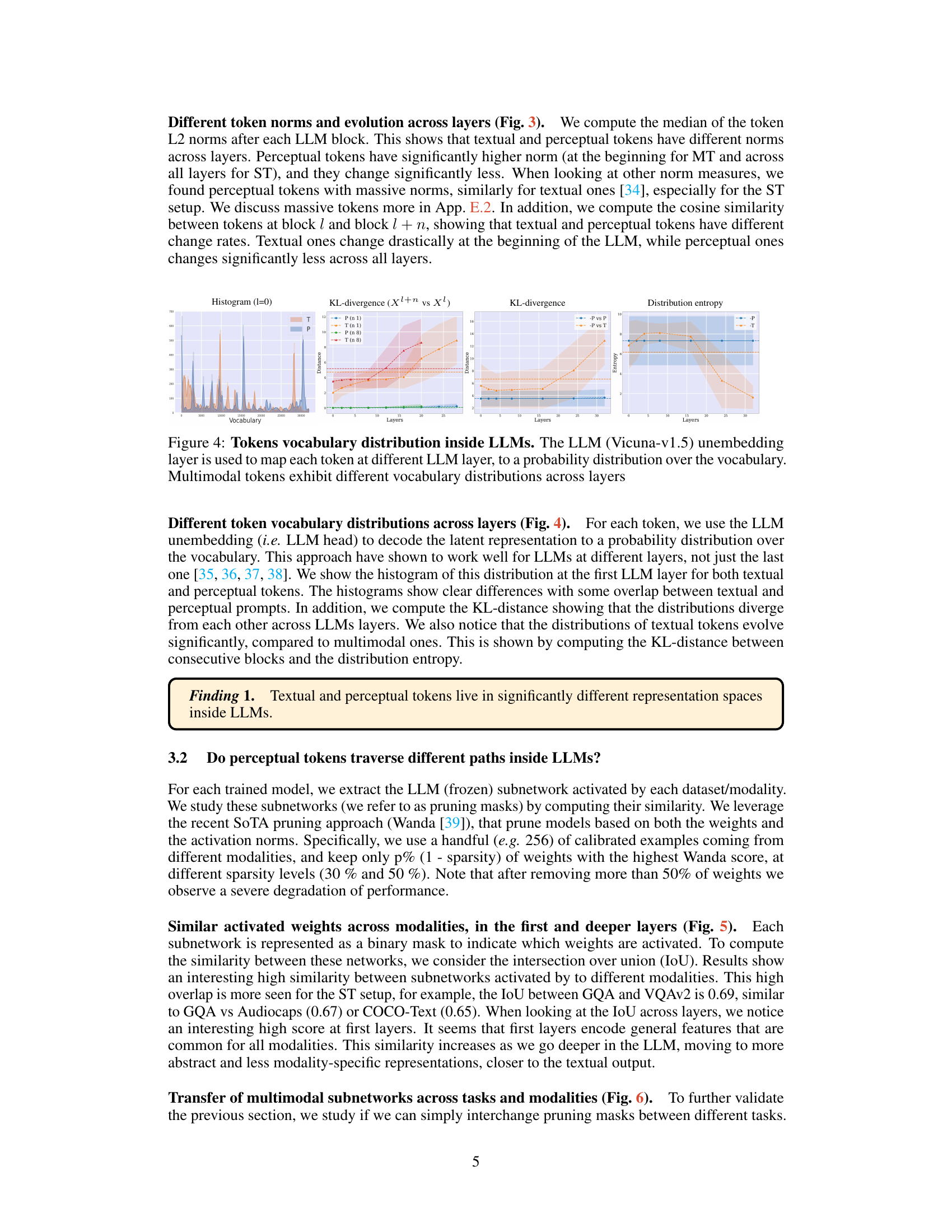

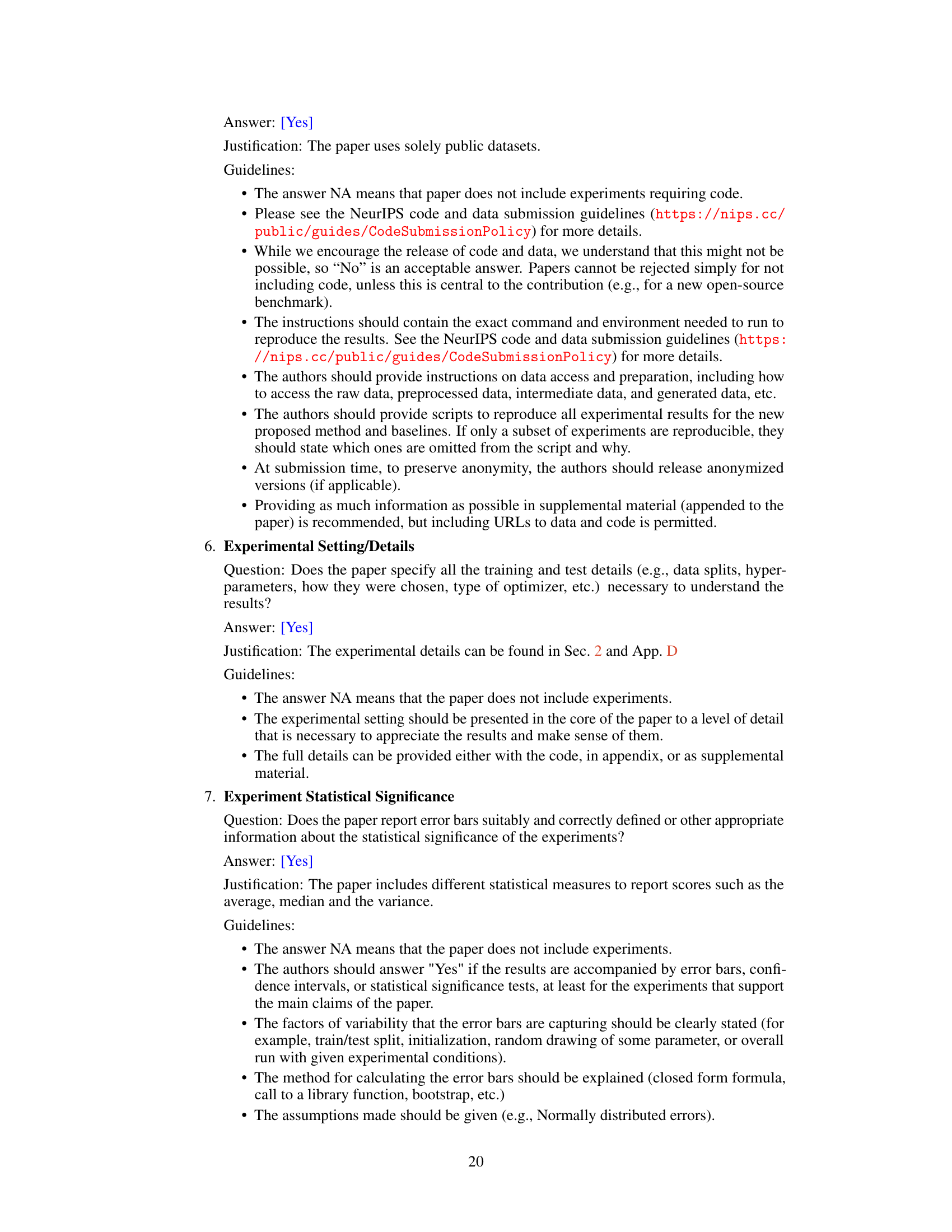

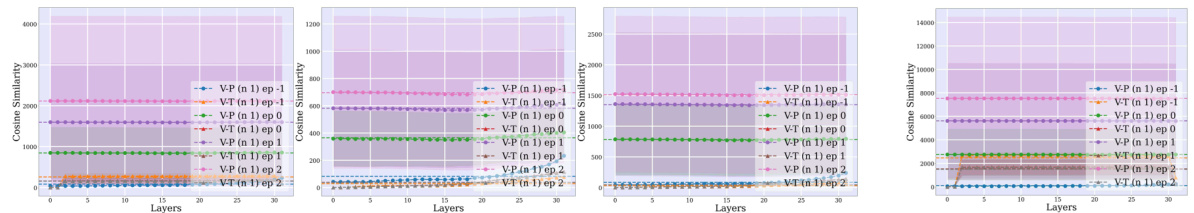

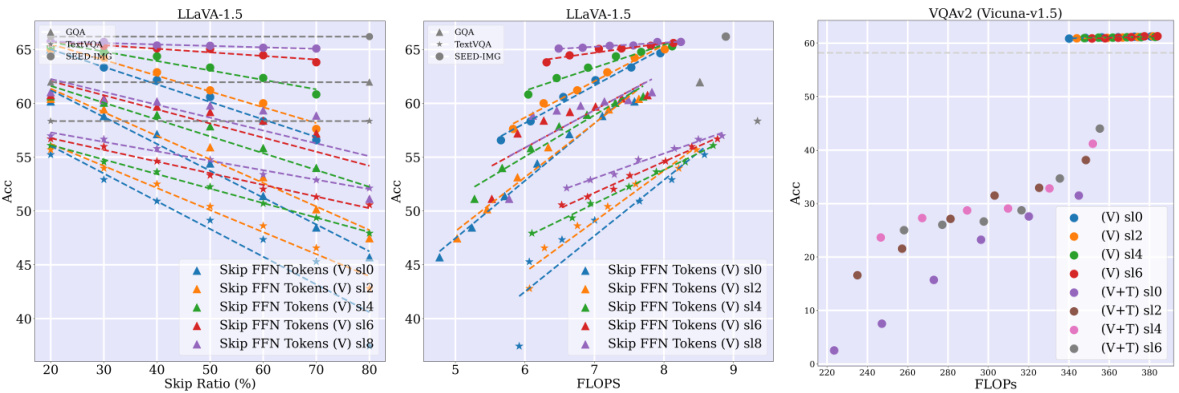

🔼 This figure shows the evolution of token norms and cosine similarity between consecutive layers in a large language model (LLM) for both single-task (ST) and multi-task (MT) setups. The left panel shows the results for the ST setup, while the right panel shows the results for the MT setup. The top row displays the cosine similarity between tokens in consecutive blocks across various layers of the LLM, indicating how similar the token representations are in consecutive blocks. The bottom row displays the median L2 norm of the tokens after each block. The figure demonstrates that textual and visual tokens behave differently within the LLM, showing distinct patterns in their norm and similarity changes.

read the caption

Figure 3: Tokens norm and evolution across LLM layers. The tokenwise cosine similarity between consecutive blocks (e.g., Xl+n and X¹), and the median token L2 norm after each block (X¹) for the ST (left) and MT (right) setups. Textual and visual tokens evolve differently inside LLMs.

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between different types of tokens (perceptual vs. perceptual, textual vs. textual, and perceptual vs. textual) within a Large Language Model (LLM) across different layers. The results indicate that perceptual tokens from various modalities (image, video, and audio) tend to cluster together in distinct regions of the LLM’s embedding space, forming ’narrow cones.’ Textual tokens also form a distinct cone, but there is less overlap between the perceptual and textual token cones, indicating a clear separation in their representations. A t-SNE visualization further supports this separation, showing distinct clusters for different modality tokens. This suggests that the LLM doesn’t simply translate perceptual information directly into textual representations but maintains separate yet aligned spaces for different modalities.

read the caption

Figure 2: Multimodal narrow cones. The cosine similarity after LLM blocks (B) between: perceptual tokens (P vs P), textual tokens (T vs T), perceptual and textual tokens (P vs T). pvspandt vs t refer to the intra similarity within the same dataset. We also visualize the t-SNE of tokens (at layer 24) showing they stay separated inside the model. V (Video), I (Image), A (Audio).

🔼 This figure displays the results of a cosine similarity analysis performed on different types of tokens within a Large Language Model (LLM). Specifically, it compares the similarity between perceptual tokens (from image, video, and audio data), textual tokens, and the similarity between perceptual and textual tokens. The results show that perceptual and textual tokens occupy distinct spaces (’narrow cones’), indicating that the LLM doesn’t simply translate perceptual information directly into text. A t-SNE visualization further supports this, showing clear separation between the different token types within the LLM’s representation space.

read the caption

Figure 2: Multimodal narrow cones. The cosine similarity after LLM blocks (B) between: perceptual tokens (P vs P), textual tokens (T vs T), perceptual and textual tokens (P vs T). p vs p and t vs t refer to the intra similarity within the same dataset. We also visualize the t-SNE of tokens (at layer 24) showing they stay separated inside the model. V (Video), I (Image), A (Audio).

🔼 This figure provides a visual summary of the research paper’s methodology and findings. It shows that although multimodal tokens (image, video, audio, and text) occupy distinct representation spaces within LLMs, they exhibit an implicit multimodal alignment (IMA). The researchers view this alignment as a key factor allowing LLMs to generalize effectively to multimodal inputs. The diagram illustrates how the IMA effect is related to an LLM’s architecture, specifically its structure as a residual stream with steering blocks. Further, the figure highlights the practical implications of this discovery for improving LLM performance, ensuring safety, and enhancing computational efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

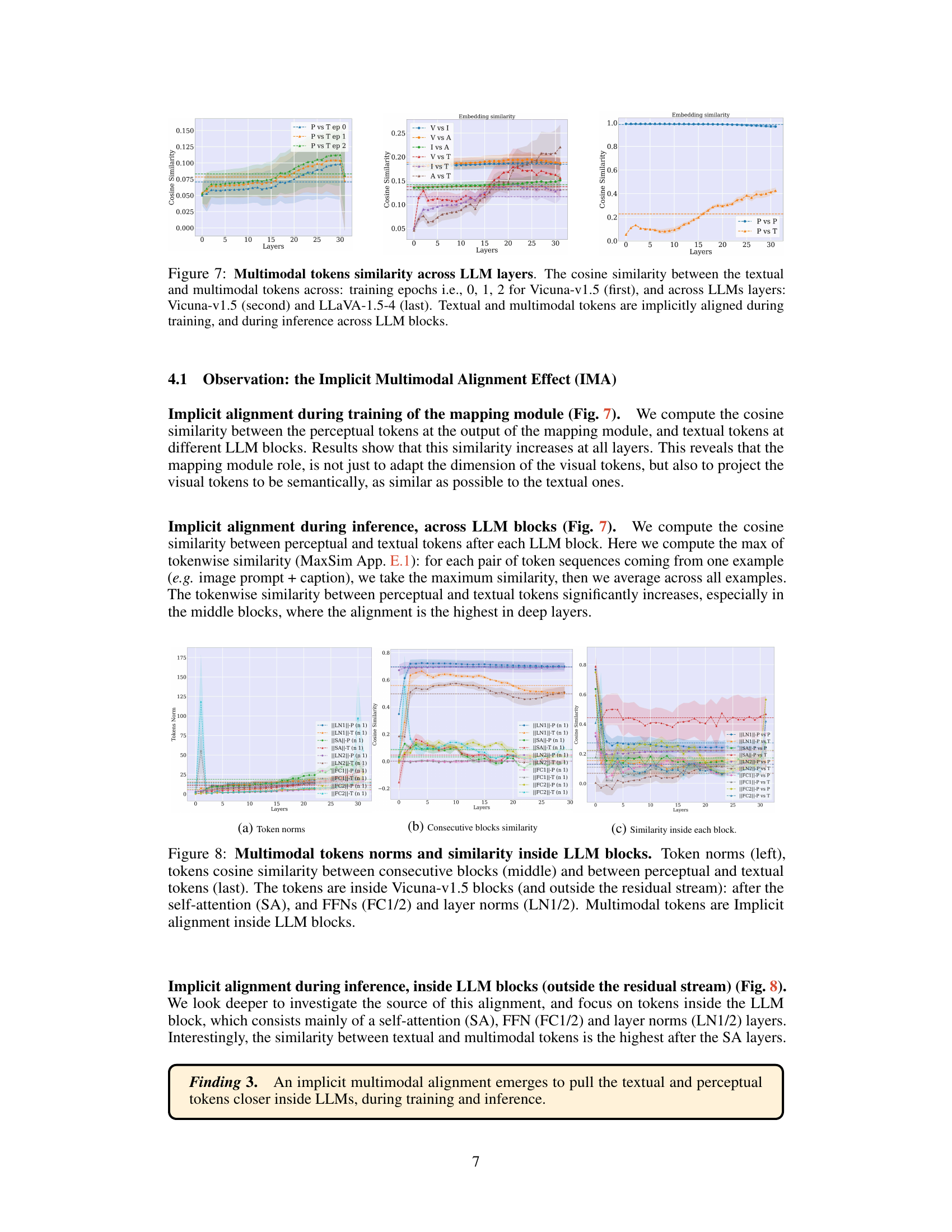

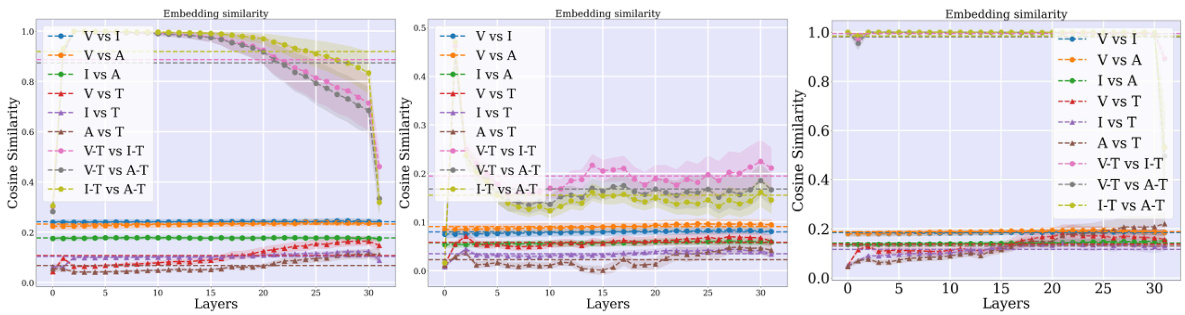

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens at different stages of the LLM processing. The first column represents the similarity during the training process of the mapping module at different epochs. The other two columns show the similarity during inference across the different layers of the Vicuna-v1.5 and LLaVA-1.5-4 models. It demonstrates the implicit multimodal alignment effect (IMA), highlighting that even though textual and multimodal tokens exist in different representation spaces within the LLMs, they gradually become more aligned as processing goes on.

read the caption

Figure 7: Multimodal tokens similarity across LLM layers. The cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across: training epochs i.e., 0, 1, 2 for Vicuna-v1.5 (first), and across LLMs layers: Vicuna-v1.5 (second) and LLaVA-1.5-4 (last). Textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned during training, and during inference across LLM blocks.

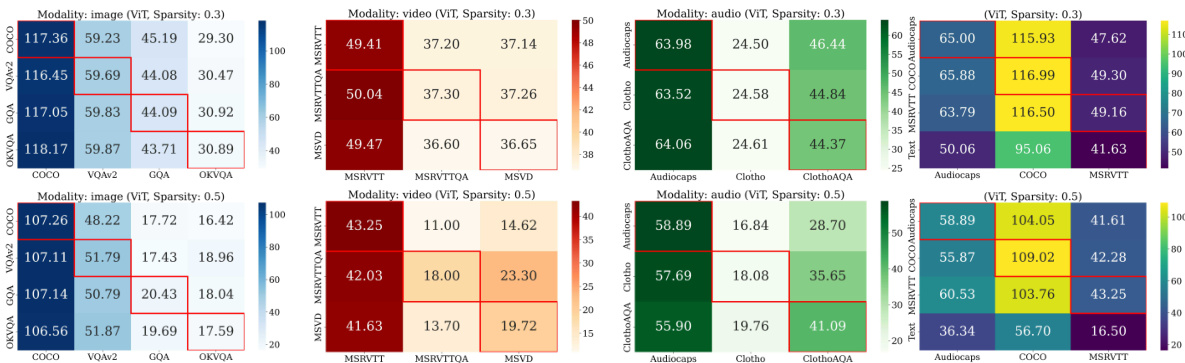

🔼 This figure visualizes the token norms and similarities within the Vicuna-v1.5 LLM blocks. Three subplots are shown: (a) Token Norms: Shows the median L2 norm of tokens after each layer normalization (LN1), self-attention (SA), and feed-forward network (FFN) layers within a block. This illustrates the evolution of token norms in different processing stages. (b) Consecutive Blocks Similarity: Shows the cosine similarity between tokens from consecutive blocks (e.g., the output of one block compared to the input of the next). This demonstrates how the token representation changes between blocks. (c) Similarity inside each Block: Shows the cosine similarity between perceptual and textual tokens within each LLM block, after each processing layer. This highlights the effect of implicit multimodal alignment (IMA) as tokens from different modalities become more similar during processing. The visualization supports the observation that implicit alignment is happening within the Transformer blocks, particularly after the self-attention layer.

read the caption

Figure 8: Multimodal tokens norms and similarity inside LLM blocks. Token norms (left), tokens cosine similarity between consecutive blocks (middle) and between perceptual and textual tokens (last). The tokens are inside Vicuna-v1.5 blocks (and outside the residual stream): after the self-attention (SA), and FFNs (FC1/2) and layer norms (LN1/2). Multimodal tokens are Implicit alignment inside LLM blocks.

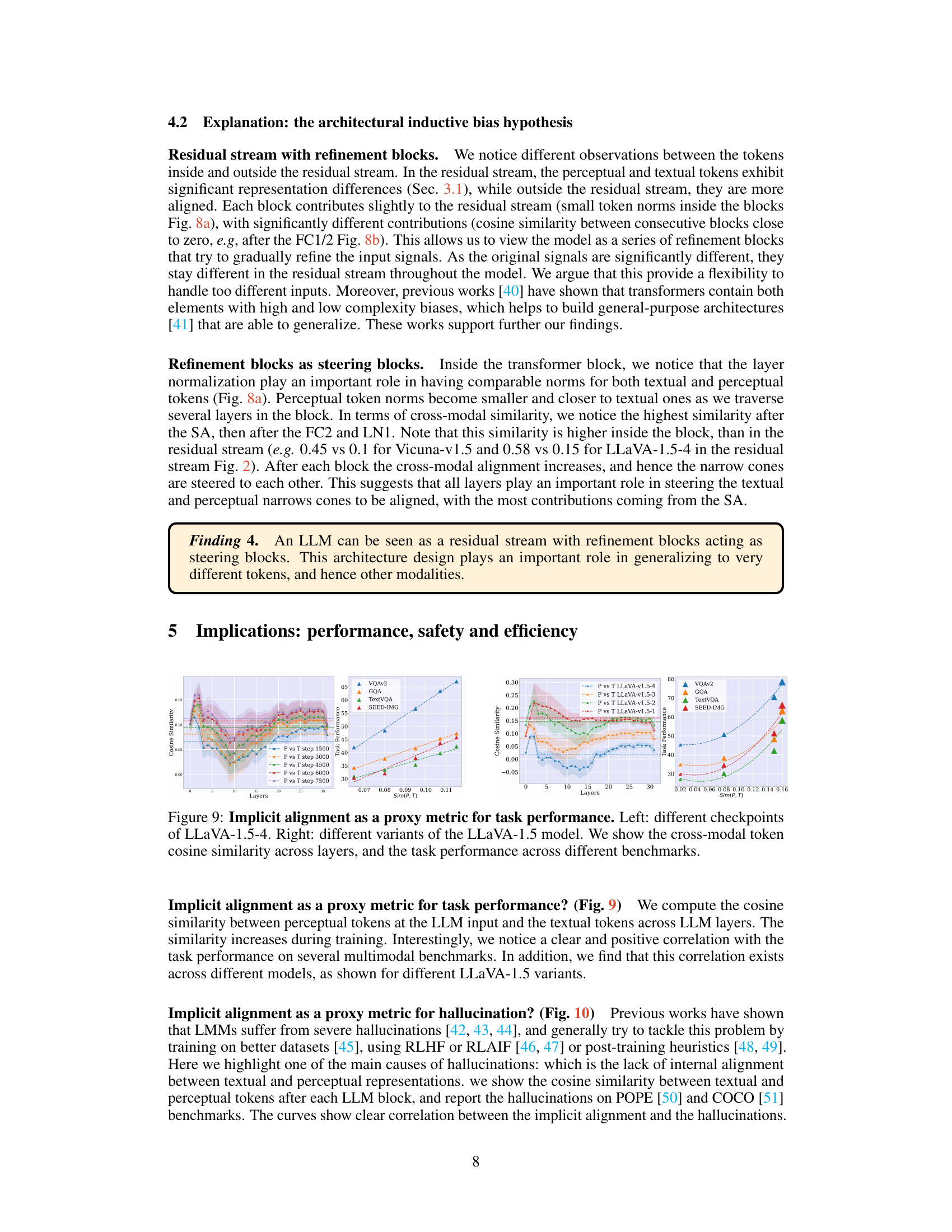

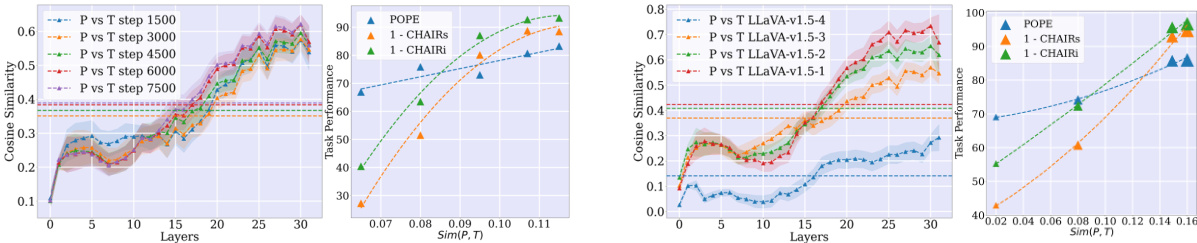

🔼 This figure shows the correlation between implicit multimodal alignment (IMA) score and task performance across different LMMs. The left panel displays the IMA score for various checkpoints of a single LLaVA-1.5-4 model, while the right panel compares IMA scores for different LLaVA-1.5 model variants. The results demonstrate a positive correlation between IMA score (a measure of alignment between perceptual and textual tokens inside the LLM) and the performance on several multimodal benchmarks (VQAv2, GQA, TextVQA, SEED-IMG). This suggests IMA score could potentially serve as a proxy metric for evaluating and selecting LMMs.

read the caption

Figure 9: Implicit alignment as a proxy metric for task performance. Left: different checkpoints of LLaVA-1.5-4. Right: different variants of the LLaVA-1.5 model. We show the cross-modal token cosine similarity across layers, and the task performance across different benchmarks.

🔼 This figure shows the correlation between implicit multimodal alignment and task performance. The left panel displays results from different checkpoints during the training of the LLaVA-1.5-4 model, showing how the cross-modal token cosine similarity between perceptual and textual tokens changes across LLM layers. The right panel shows the same metric for different variants of the LLaVA-1.5 model. For each model, there is a positive correlation between the overall cross-modal similarity (averaged across all layers) and the performance on different downstream benchmarks (VQAv2, GQA, TextVQA, SEED-IMG). This suggests that the implicit multimodal alignment score could serve as a proxy metric for model evaluation.

read the caption

Figure 9: Implicit alignment as a proxy metric for task performance. Left: different checkpoints of LLaVA-1.5-4. Right: different variants of the LLaVA-1.5 model. We show the cross-modal token cosine similarity across layers, and the task performance across different benchmarks.

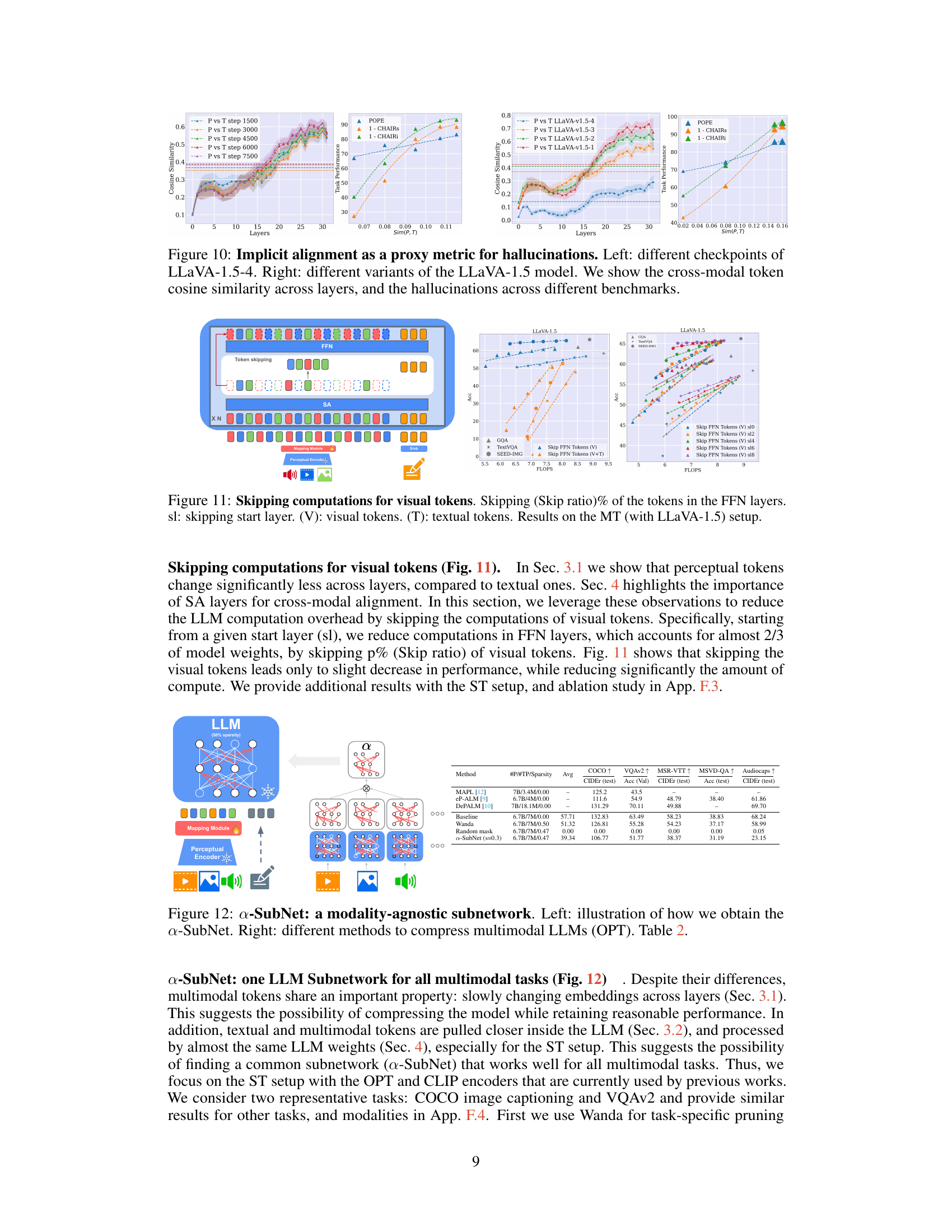

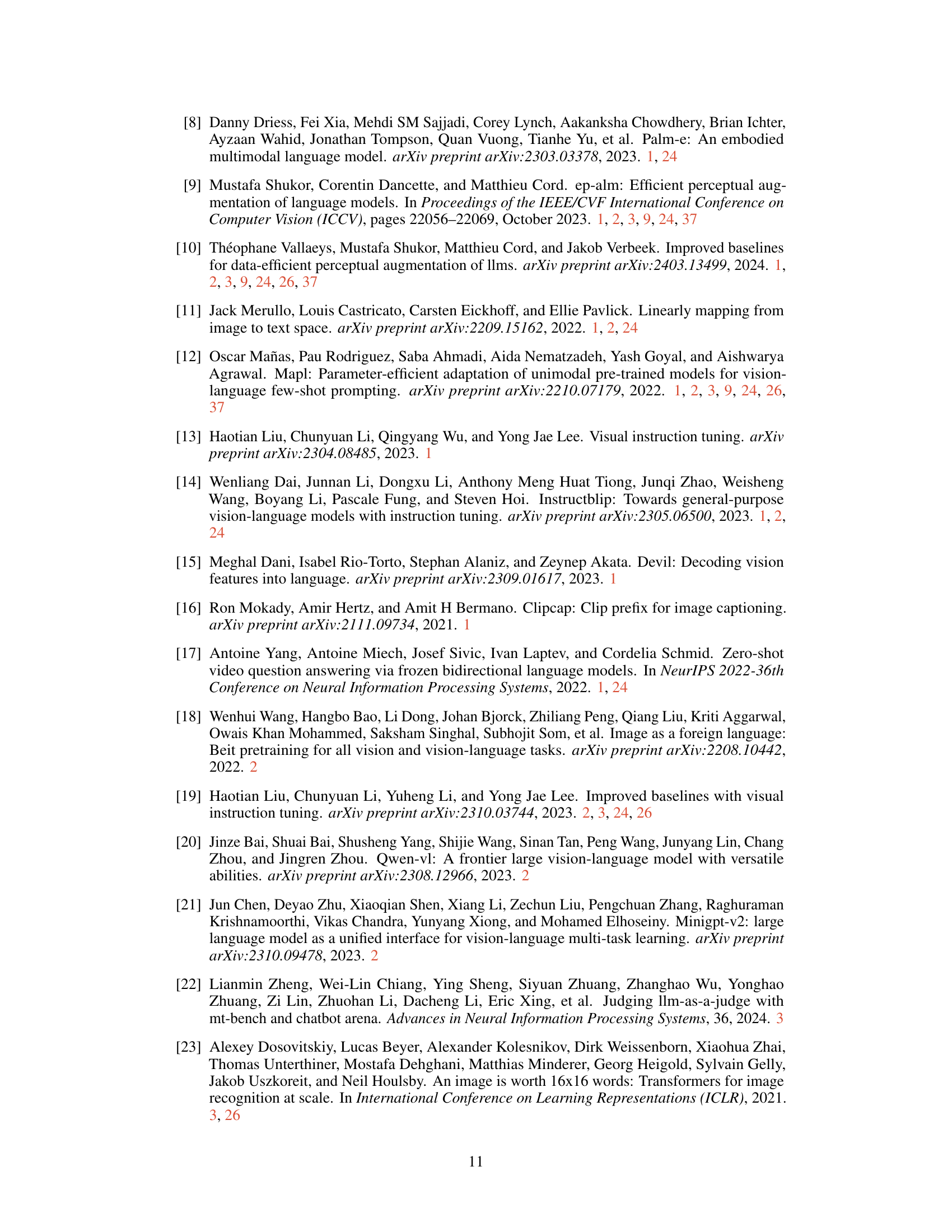

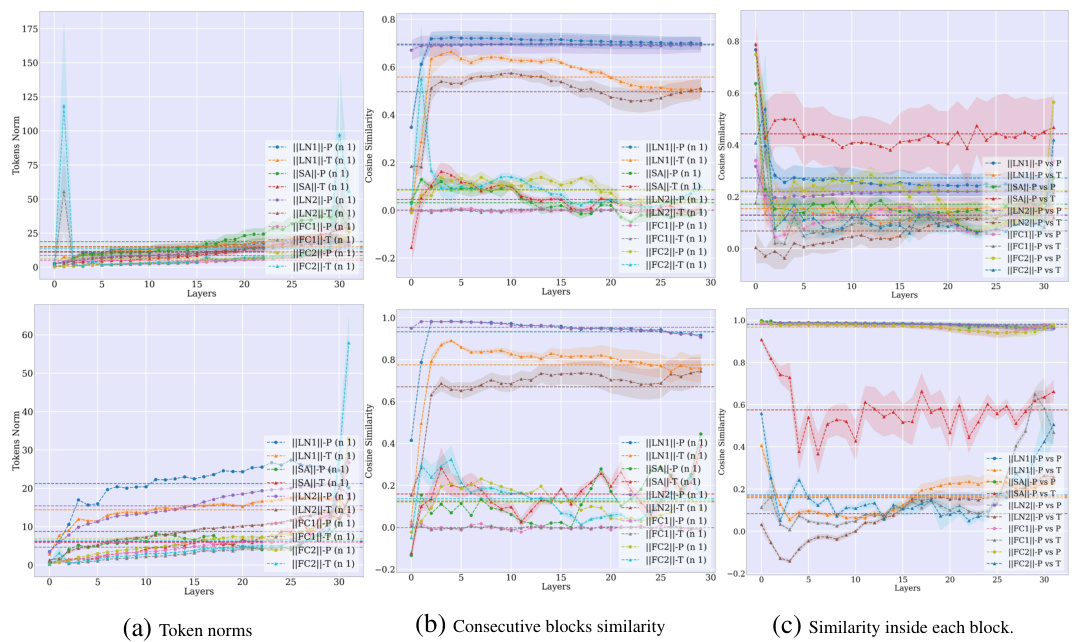

🔼 This figure shows the results of an experiment where the authors skipped computations for visual tokens in the feed-forward network (FFN) layers of a Large Language Model (LLM). The goal was to improve computational efficiency without significantly impacting performance. The x-axis represents the FLOPS (floating point operations per second), a measure of computational cost. The y-axis represents the accuracy of the model on various multimodal tasks. Different lines represent different strategies for skipping computations, varying the skip ratio (percentage of tokens skipped) and the starting layer (sl) at which skipping begins. The results show a trade-off between computation cost reduction and accuracy. The authors demonstrate the ability to skip a significant number of computations in FFN layers without a drastic decrease in model accuracy, suggesting a potential method for enhancing efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 11: Skipping computations for visual tokens. Skipping (Skip ratio)% of the tokens in the FFN layers. sl: skipping start layer. (V): visual tokens. (T): textual tokens. Results on the MT (with LLaVA-1.5) setup.

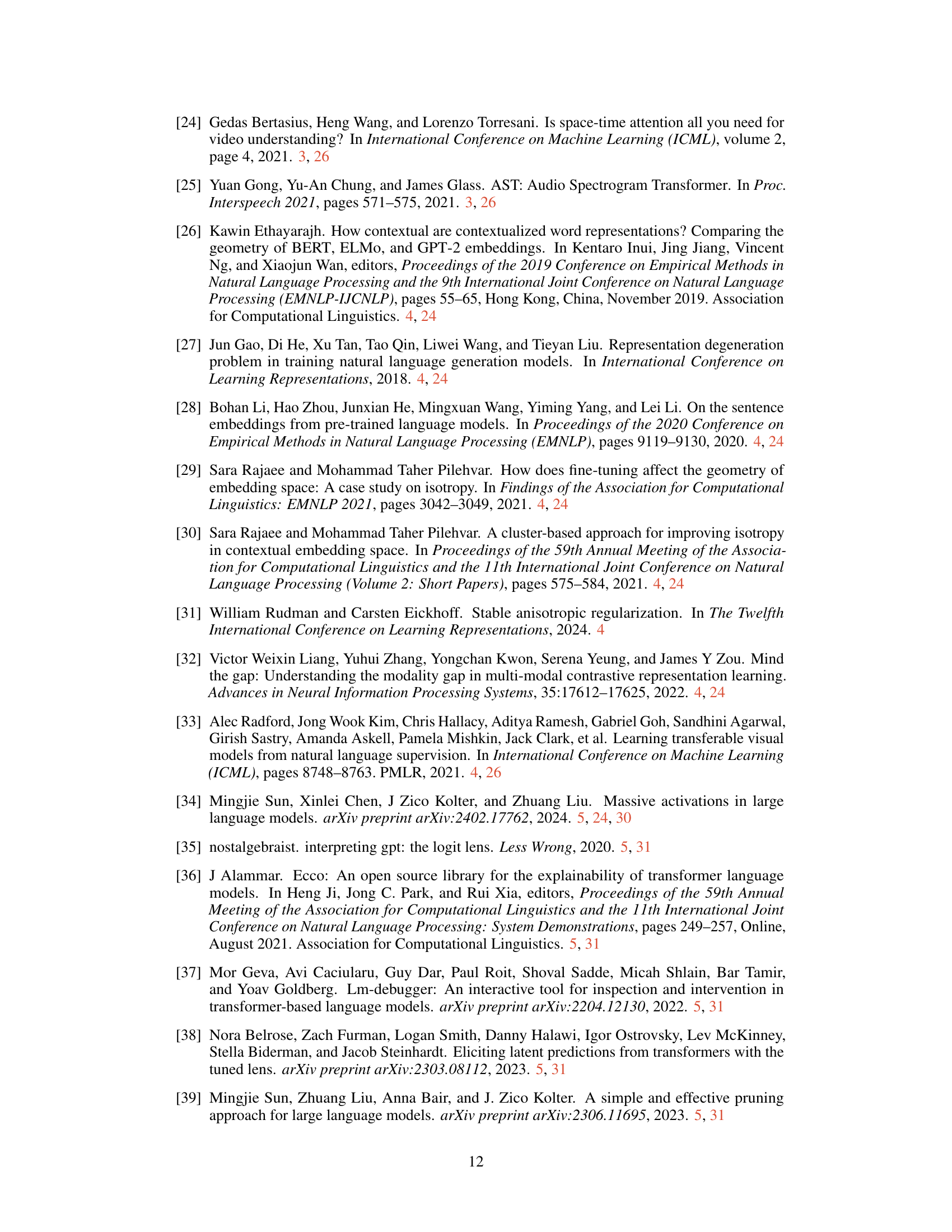

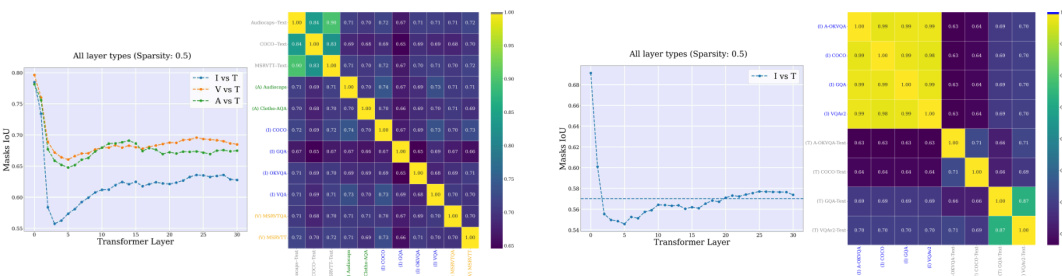

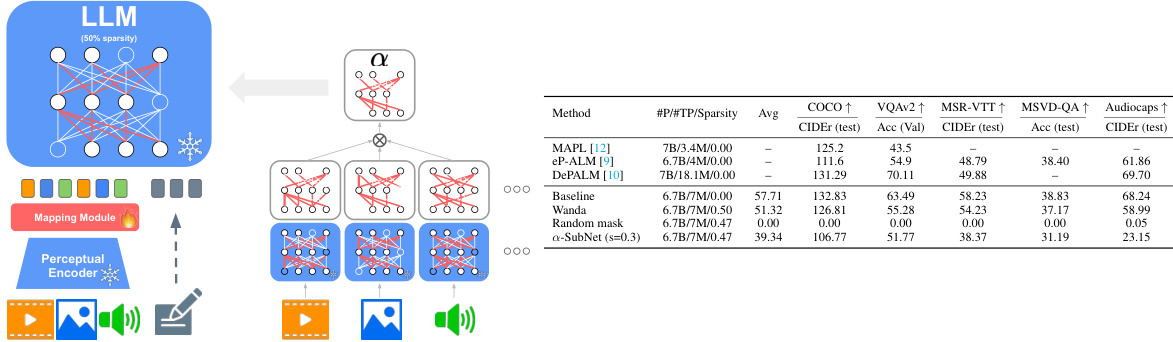

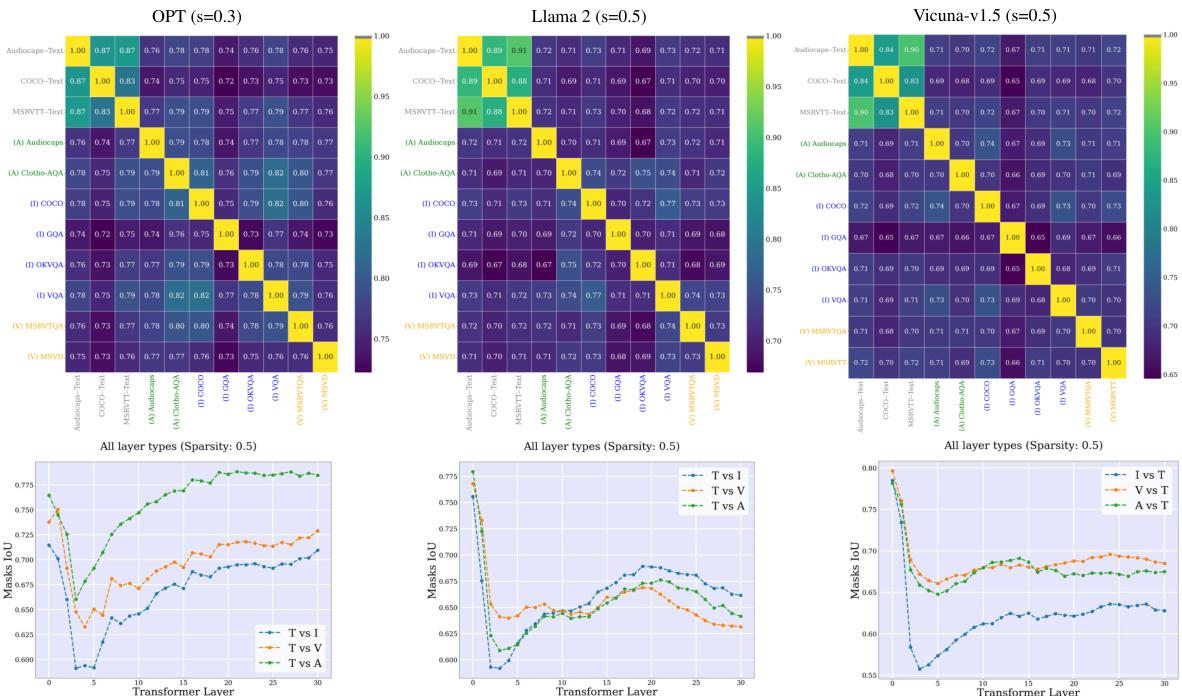

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of a modality-agnostic subnetwork (a-SubNet) for compressing multimodal LLMs. The left panel shows how the a-SubNet is obtained by extracting a common subnetwork from multiple modality-specific subnetworks, while the right panel compares various compression techniques including the proposed a-SubNet method against others such as magnitude pruning and random mask pruning using OPT.

read the caption

Figure 12: a-SubNet: a modality-agnostic subnetwork. Left: illustration of how we obtain the a-SubNet. Right: different methods to compress multimodal LLMs (OPT).

🔼 This figure shows the results of cosine similarity calculations performed on different types of tokens (perceptual vs. perceptual, textual vs. textual, and perceptual vs. textual) within a Large Language Model (LLM) across multiple layers. The results demonstrate that perceptual tokens (from image, video, and audio modalities) reside in distinctly separate representational spaces (narrow cones) from textual tokens. Additionally, a t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) visualization is included, providing a visual representation of the token separation within the LLM.

read the caption

Figure 2: Multimodal narrow cones. The cosine similarity after LLM blocks (B) between: perceptual tokens (P vs P), textual tokens (T vs T), perceptual and textual tokens (P vs T). pvspandt vs t refer to the intra similarity within the same dataset. We also visualize the t-SNE of tokens (at layer 24) showing they stay separated inside the model. V (Video), I (Image), A (Audio).

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens at different stages. The first part shows the evolution of similarity during the training of a mapping module across different epochs. The second and third parts illustrate the evolution of similarity across layers within two different LLMs (Vicuna-v1.5 and LLaVA-1.5-4) during inference. The results demonstrate an implicit multimodal alignment effect, where the similarity between textual and multimodal tokens increases during training and inference, particularly within the LLM blocks. The higher similarity across layers suggests an implicit alignment process that facilitates the generalization of LLMs to multimodal inputs.

read the caption

Figure 7: Multimodal tokens similarity across LLM layers. The cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across: training epochs i.e., 0, 1, 2 for Vicuna-v1.5 (first), and across LLMs layers: Vicuna-v1.5 (second) and LLaVA-1.5-4 (last). Textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned during training, and during inference across LLM blocks.

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens at different stages of the model’s processing. The top row shows the evolution of similarity during training across epochs, while the bottom rows show the similarity across layers in two different LLMs, Vicuna-v1.5 and LLaVA-1.5-4. The results demonstrate that textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned in the LLMs, both during training and during the inference stage. This implicit alignment increases across LLM layers and is linked to the architecture, indicating that LLMs generalize to multimodal inputs because of their architectural design.

read the caption

Figure 7: Multimodal tokens similarity across LLM layers. The cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across: training epochs i.e., 0, 1, 2 for Vicuna-v1.5 (first), and across LLMs layers: Vicuna-v1.5 (second) and LLaVA-1.5-4 (last). Textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned during training, and during inference across LLM blocks.

🔼 This figure displays three sets of graphs showing the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens across various layers and training epochs of LLMs. The first set demonstrates the changes in cosine similarity across different training epochs for the Vicuna-v1.5 model. The second and third sets show the cosine similarity changes across LLM layers for Vicuna-v1.5 and LLaVA-1.5-4, respectively. The graphs illustrate the implicit multimodal alignment, indicating that despite living in different representation spaces, textual and multimodal tokens become increasingly aligned as the model processes information, particularly within LLM blocks.

read the caption

Figure 7: Multimodal tokens similarity across LLM layers. The cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across: training epochs i.e., 0, 1, 2 for Vicuna-v1.5 (first), and across LLMs layers: Vicuna-v1.5 (second) and LLaVA-1.5-4 (last). Textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned during training, and during inference across LLM blocks.

🔼 This figure summarizes the key findings and implications of the research paper. The core finding is the Implicit Multimodal Alignment (IMA) effect, which shows that although perceptual (image, audio, video) tokens and textual tokens live in distinct representation spaces within LLMs, they are implicitly aligned. The researchers interpret this alignment as a result of the LLM’s architecture, specifically its structure as a residual stream with steering blocks. This IMA effect then has implications for model performance (IMA score as a potential proxy metric), safety (connection between alignment and hallucination reduction), and efficiency (methods to compress LLMs and skip computations).

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

🔼 This figure visualizes how the norms and cosine similarity of tokens change across different layers of the Large Language Model (LLM). It compares the behavior of textual and visual (perceptual) tokens separately. The left panel shows the results for a single-task setup, while the right panel displays the findings for a multitask setup. The results reveal that textual and visual tokens have different norms and evolutionary patterns within the LLM, indicating distinct representation spaces.

read the caption

Figure 3: Tokens norm and evolution across LLM layers. The tokenwise cosine similarity between consecutive blocks (e.g., Xl+n and X¹), and the median token L2 norm after each block (X¹) for the ST (left) and MT (right) setups. Textual and visual tokens evolve differently inside LLMs.

🔼 This figure shows the comparison of the median token L2 norm and the tokenwise cosine similarity between consecutive blocks in different layers of LLMs for single-task (ST) and multitask (MT) setups. The left panel displays results for ST, while the right panel shows results for MT. The data reveals that textual and visual tokens have distinct norms and evolve differently across the layers of the LLM. For example, visual tokens exhibit significantly higher norms (especially at the start of the model for MT and across all layers for ST), showing relatively less change across layers compared to textual tokens. The difference between textual and visual token evolution is evident across the layers, indicating varying changes in both norm and similarity measures for each modality.

read the caption

Figure 3: Tokens norm and evolution across LLM layers. The tokenwise cosine similarity between consecutive blocks (e.g., Xl+n and X¹), and the median token L2 norm after each block (X¹) for the ST (left) and MT (right) setups. Textual and visual tokens evolve differently inside LLMs.

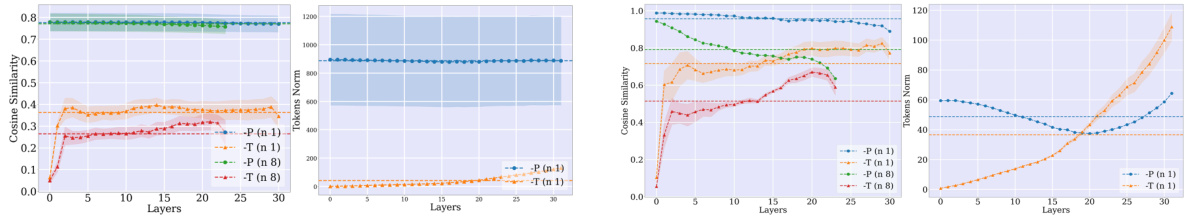

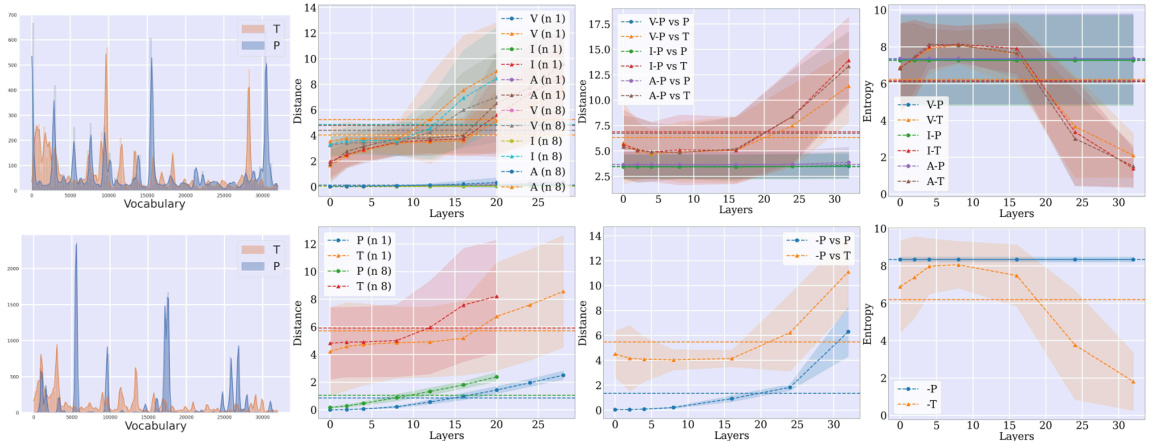

🔼 This figure presents a comprehensive analysis of the interaction between textual and multimodal tokens within different layers of the LLaVA-1.5 model (Multitask setup). It meticulously examines various aspects of token behavior to highlight the differences in the representation of text and multimodality in the model. The top row showcases the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens across LLM blocks (layers of the model), providing insights into the alignment of text and multimodality. The second row visualizes the cosine similarity between consecutive blocks, illuminating the dynamic nature of token representation. The third row demonstrates the evolution of token norms across layers, offering a closer look at the magnitude of token representations. The fourth row employs KL-divergence to quantify the differences between textual and perceptual token vocabulary distributions, and further details the differences across different model variants. Finally, the bottom row illustrates the similarity in vocabulary distributions between consecutive layers, indicating how representations change over the course of processing within the model. Overall, this figure provides a multi-faceted view of the internal workings of the model, revealing how textual and multimodal information interact and evolve across layers, revealing differences between different model configurations (with/without pretraining, use of MLP or Transformer).

read the caption

Figure 13: Textual and multimodal tokens for LLaVA-1.5 variants (MT setup). From top to bottom: (1) the cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across LLM blocks. (2) the cosine similarity between consecutive blocks. (3) token norms, (4) KL-distance between vocabulary distributions decoded from textual and perceptual tokens, (6) cosine similarity between vocabulary distribution at consecutive layers. From left to right: LLaVA-1.5, LLaVA-1.5-2, LLaVA-1.5-3, LLaVA-1.5-4.

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens at different stages of the LLM processing. It demonstrates that the similarity increases during both training (across different training epochs) and inference (across different LLM layers), suggesting an implicit alignment between the two modalities. This implicit alignment is a key finding of the paper, indicating that the LLM’s architecture facilitates generalization to multimodal inputs.

read the caption

Figure 7: Multimodal tokens similarity across LLM layers. The cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across: training epochs i.e., 0, 1, 2 for Vicuna-v1.5 (first), and across LLMs layers: Vicuna-v1.5 (second) and LLaVA-1.5-4 (last). Textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned during training, and during inference across LLM blocks.

🔼 This figure summarizes the key findings and implications of the research paper. It visually represents the workflow, starting with the analysis of multimodal tokens in LLMs. The analysis reveals that these tokens reside in distinct representational spaces (multimodal cones) but exhibit implicit alignment (IMA). This IMA effect allows LLMs to be viewed as residual streams with steering blocks, explaining their ability to generalize across modalities. The figure then illustrates how this understanding leads to practical implications in model performance, safety, and computational efficiency by highlighting potential improvements to these aspects.

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

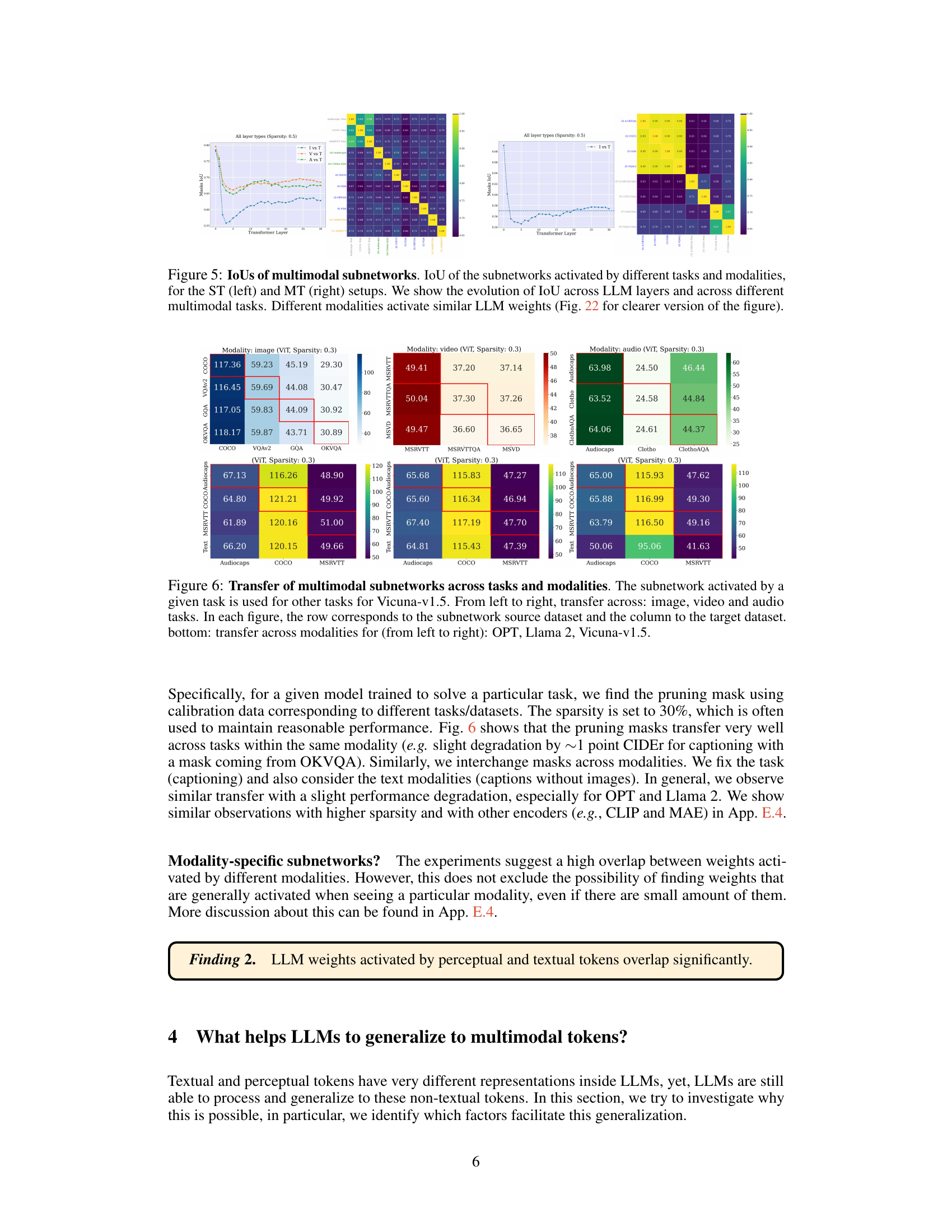

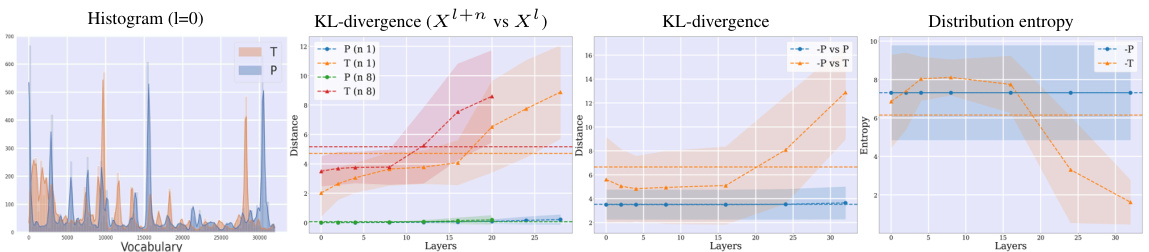

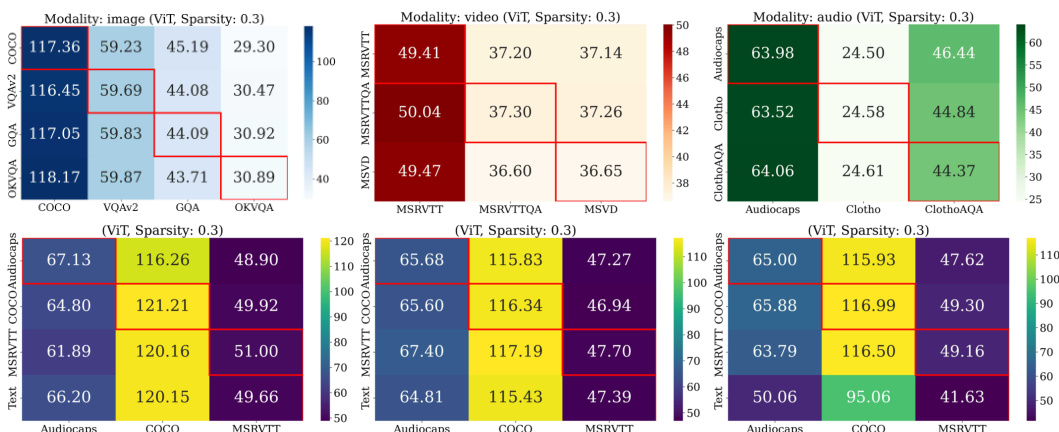

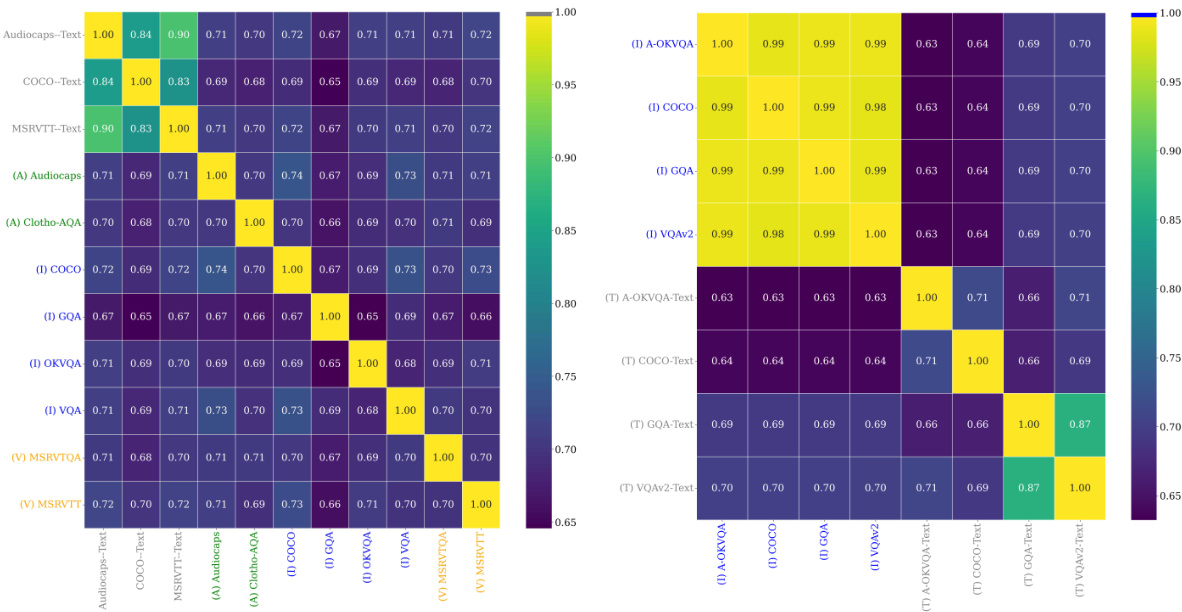

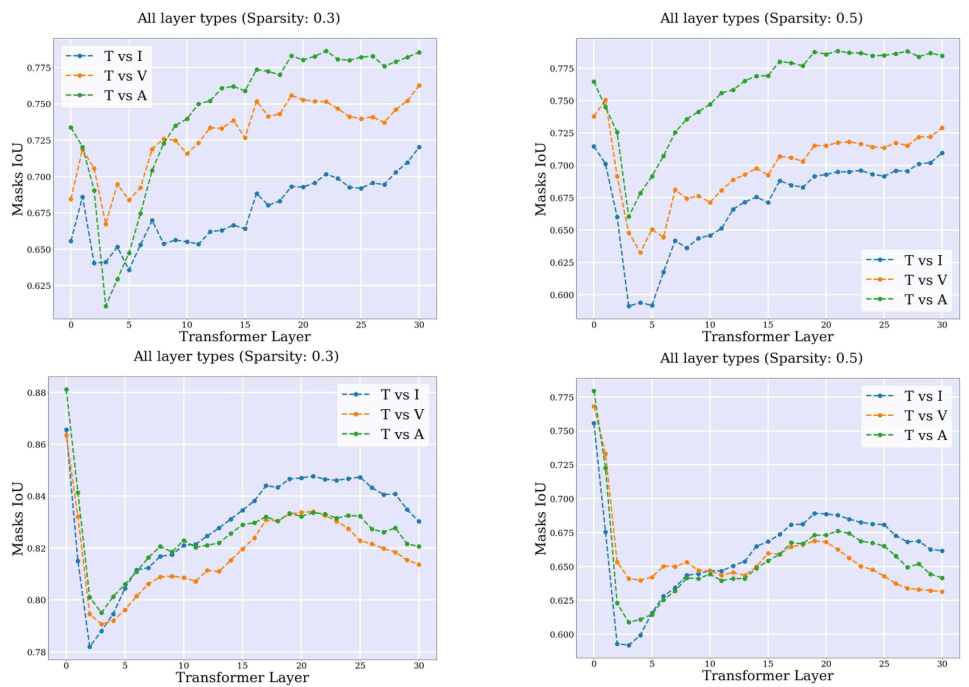

🔼 This figure visualizes the Intersection over Union (IoU) scores of subnetworks activated by different tasks and modalities in both single-task (ST) and multitask (MT) setups. The heatmaps show the overlap in activated weights across different modalities and tasks. Higher IoU values indicate greater similarity and potential for sharing weights between tasks. The figure provides evidence supporting the claim that different modalities activate similar LLM weights, contributing to the model’s ability to generalize across modalities.

read the caption

Figure 22: IoUs of multimodal subnetworks. IoU of the subnetworks activated by different tasks and modalities, for the ST (left) and MT (right) setups. Different modalities activate similar LLM weights.

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens at different stages. The top row shows the similarity changing across training epochs (0,1,2) for Vicuna-v1.5. The middle and bottom rows show how that similarity changes across the layers of Vicuna-v1.5 and LLaVA-1.5-4 respectively. The key observation is that textual and multimodal tokens show increasing similarity across layers during both training and inference, which is referred to as Implicit Multimodal Alignment.

read the caption

Figure 7: Multimodal tokens similarity across LLM layers. The cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across: training epochs i.e., 0, 1, 2 for Vicuna-v1.5 (first), and across LLMs layers: Vicuna-v1.5 (second) and LLaVA-1.5-4 (last). Textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned during training, and during inference across LLM blocks.

🔼 This figure compares textual and visual tokens across different layers of LLMs. It shows that textual and perceptual tokens have different norms and rates of change across the layers of LLMs. The left panel shows the single-task (ST) setup while the right panel shows the multi-task (MT) setup. The cosine similarity between consecutive blocks indicates textual tokens change drastically at the beginning of the model while perceptual tokens change less drastically. The median L2 norm demonstrates that perceptual tokens have significantly higher norms than textual ones, and change less drastically.

read the caption

Figure 3: Tokens norm and evolution across LLM layers. The tokenwise cosine similarity between consecutive blocks (e.g., Xl+n and X¹), and the median token L2 norm after each block (X¹) for the ST (left) and MT (right) setups. Textual and visual tokens evolve differently inside LLMs.

🔼 This figure shows the correlation between the implicit multimodal alignment score and task performance across different models and datasets. The left panel displays results from different checkpoints of the LLaVA-1.5-4 model, demonstrating that as the alignment score increases during training, so does task performance. The right panel presents results across various LLaVA-1.5 model variants, showing that this positive correlation persists across different model configurations. This suggests that the implicit alignment score could serve as a proxy metric for model evaluation and selection.

read the caption

Figure 9: Implicit alignment as a proxy metric for task performance. Left: different checkpoints of LLaVA-1.5-4. Right: different variants of the LLaVA-1.5 model. We show the cross-modal token cosine similarity across layers, and the task performance across different benchmarks.

🔼 This figure summarizes the key findings and contributions of the research paper. It visually depicts the workflow, starting with the analysis of multimodal tokens within Large Language Models (LLMs). The study reveals that these tokens, while residing in distinct representational spaces (multimodal cones), exhibit implicit alignment (IMA). This IMA effect is interpreted as a crucial factor enabling the generalization of LLMs to multimodal inputs. The figure further illustrates how this understanding of LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks leads to several practical implications across performance, safety, and efficiency aspects of multimodal models.

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

🔼 This figure displays the correlation between implicit multimodal alignment and task performance. The left panel shows the cross-modal token cosine similarity across layers for different checkpoints of the LLaVA-1.5-4 model, while the right panel shows the same metric for different variants of the LLaVA-1.5 model. Both panels also illustrate the performance on various multimodal benchmarks. A positive correlation suggests that the implicit multimodal alignment score can act as a proxy for predicting model performance.

read the caption

Figure 9: Implicit alignment as a proxy metric for task performance. Left: different checkpoints of LLaVA-1.5-4. Right: different variants of the LLaVA-1.5 model. We show the cross-modal token cosine similarity across layers, and the task performance across different benchmarks.

🔼 This figure visualizes the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens across different layers of LLMs during both training and inference. It shows that the similarity between these two types of tokens increases as the model processes the input, which supports the paper’s claim of implicit multimodal alignment. The results are presented for different models (Vicuna-v1.5 and LLaVA-1.5-4) and training epochs to illustrate the robustness of this phenomenon.

read the caption

Figure 7: Multimodal tokens similarity across LLM layers. The cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across: training epochs i.e., 0, 1, 2 for Vicuna-v1.5 (first), and across LLMs layers: Vicuna-v1.5 (second) and LLaVA-1.5-4 (last). Textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned during training, and during inference across LLM blocks.

🔼 This figure summarizes the key findings and implications of the research paper. The analysis begins by examining how multimodal tokens (image, video, audio, and text) are represented within Large Language Models (LLMs). The study reveals that these tokens reside in distinct representational spaces, forming what are described as ‘multimodal cones’. Despite their differences, these tokens show an ‘implicit multimodal alignment’ (IMA). This IMA effect suggests that the architecture of LLMs facilitates their ability to generalize to multimodal inputs. The figure highlights three main implications stemming from these findings: 1. The IMA score serves as a potential proxy metric for assessing model performance and identifying instances of hallucinations; 2. Hallucinations appear to be primarily caused by misalignments between the internal representations of perceptual and textual inputs; and 3. The architectural design allows for computational efficiency improvements through skipping computations and LLM compression techniques.

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

🔼 This figure shows the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens across different layers of LLMs during both training and inference. It demonstrates the Implicit Multimodal Alignment (IMA) effect, where the similarity between these different types of tokens increases across layers. Three different experimental setups are presented. The first shows the alignment across training epochs (0, 1, 2). The second and third show layer-wise alignment for two different LLMs: Vicuna-v1.5 and LLaVA-1.5-4. This visualization provides evidence for the IMA effect across various LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 7: Multimodal tokens similarity across LLM layers. The cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across: training epochs i.e., 0, 1, 2 for Vicuna-v1.5 (first), and across LLMs layers: Vicuna-v1.5 (second) and LLaVA-1.5-4 (last). Textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned during training, and during inference across LLM blocks.

🔼 This figure summarizes the key findings and implications of the research. It shows that while multimodal tokens (image, video, audio, text) exist in distinct representation spaces within LLMs, they exhibit an implicit multimodal alignment (IMA). This IMA is attributed to the LLM’s architecture, specifically its structure as a residual stream with steering blocks. The figure highlights the implications of this discovery for improving LLM performance, ensuring safety, and enhancing computational efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the implicit multimodal alignment (IMA) effect across different layers of LLMs during both training and inference. The top row shows the cosine similarity between textual and multimodal tokens across training epochs, highlighting the alignment during the mapping module training phase. The bottom two rows illustrate how the cosine similarity changes across the layers of Vicuna-v1.5 and LLaVA-1.5-4 models during inference, with a clear increase in similarity across layers. This indicates the implicit alignment of perceptual and textual tokens within the LLMs, even without explicit training.

read the caption

Figure 7: Multimodal tokens similarity across LLM layers. The cosine similarity between the textual and multimodal tokens across: training epochs i.e., 0, 1, 2 for Vicuna-v1.5 (first), and across LLMs layers: Vicuna-v1.5 (second) and LLaVA-1.5-4 (last). Textual and multimodal tokens are implicitly aligned during training, and during inference across LLM blocks.

🔼 This figure compares the implicit multimodal alignment score across different layers for various encoders in LLMs (Large Language Models). The comparison highlights that CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) models show the highest alignment between perceptual (image) and textual tokens across all layers of the LLM. In contrast, self-supervised models like MAE (Masked Autoencoder) exhibit the lowest alignment, indicating a greater distinction between the representations of the two modalities. Despite the differences, the relatively low cosine similarity scores suggest that a substantial modality gap persists in LLMs, even in cases where the encoder is designed to align features with text.

read the caption

Figure 34: Comparison of implicit multimodal alignment score across layers for different encoders. CLIP models produce features that are most aligned to textual tokens across LLM layers. On the other hand, self-supervised encoders (e.g. MAE) produce the least text-aligned features. However, the relatively low cosine similarity score (closer to 0), reveals that the modality gap (e.g. Narrow cones) still exists in LLMs, even for text-aligned encoders.

🔼 This figure shows the correlation between the implicit multimodal alignment score and the task performance. The left panel displays results for different checkpoints of the LLaVA-1.5-4 model, while the right panel shows results for different variants of the LLaVA-1.5 model. The x-axis represents the cross-modal token cosine similarity (a measure of alignment between textual and perceptual representations) across different layers of the LLM, and the y-axis represents the performance on various multimodal benchmarks (e.g. VQAv2, GQA, TextVQA, SEED-IMG). A positive correlation indicates that better alignment corresponds to better performance. This finding suggests that the implicit multimodal alignment score can act as a proxy for model performance.

read the caption

Figure 9: Implicit alignment as a proxy metric for task performance. Left: different checkpoints of LLaVA-1.5-4. Right: different variants of the LLaVA-1.5 model. We show the cross-modal token cosine similarity across layers, and the task performance across different benchmarks.

🔼 This figure summarizes the key findings and implications of the research paper. It visually represents the multimodal token analysis within LLMs, revealing that while these tokens occupy distinct representation spaces (multimodal cones), they exhibit an implicit multimodal alignment (IMA). This IMA effect is linked to the architectural design of LLMs, specifically their functionality as residual streams with ‘steering blocks.’ The figure further highlights the implications of this discovery across three areas: improved model performance, enhanced safety by reducing hallucination, and increased computational efficiency through techniques like computation skipping and model compression.

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

🔼 This figure summarizes the main findings and contributions of the research paper. It visually depicts the process of analyzing multimodal tokens within Large Language Models (LLMs), highlighting the discovery of implicit multimodal alignment (IMA). The figure shows that while different modalities (image, video, audio, text) have distinct internal representations (multimodal cones), they exhibit an implicit alignment effect. This alignment is explained through the model’s architecture, visualized as residual streams with steering blocks. This architecture allows LLMs to generalize to multimodal inputs. The figure further indicates the implications of these findings in three major areas: performance, safety, and efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 1: Summary of the work. We start by analysing multimodal tokens inside LLMs, and find that they live in different spaces (e.g., multimodal cones). Yet they are implicitly aligned (i.e., IMA), allowing us to see LLMs as residual streams with steering blocks. This lead to implications on performance, safety and efficiency.

Full paper#