TL;DR#

Many real-world applications demand machine learning models that protect user privacy while maintaining accuracy. Differential Privacy (DP) is a gold standard for privacy, but traditional DP mechanisms often significantly reduce model performance. This is especially true in high-stakes applications where large datasets are unavailable. This paper addresses these issues.

The researchers propose a novel solution: the DPConvCNP model, which uses a convolutional conditional neural process combined with an enhanced functional DP mechanism. This model leverages meta-learning to learn how to map private data to accurate DP predictions. It is trained on simulated datasets to learn how to generate accurate predictions from noisy, clipped data under DP. Evaluations demonstrate DPConvCNP outperforms a DP Gaussian Process baseline, particularly in non-Gaussian settings, while also being faster and requiring less tuning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in differential privacy and machine learning. It presents a novel meta-learning model, DPConvCNP, that significantly improves the accuracy and calibration of differentially private regression, especially in small-data scenarios. The work also advances the theoretical understanding of functional DP mechanisms. This opens new avenues for research in privacy-preserving machine learning and offers practical solutions for high-stakes applications.

Visual Insights#

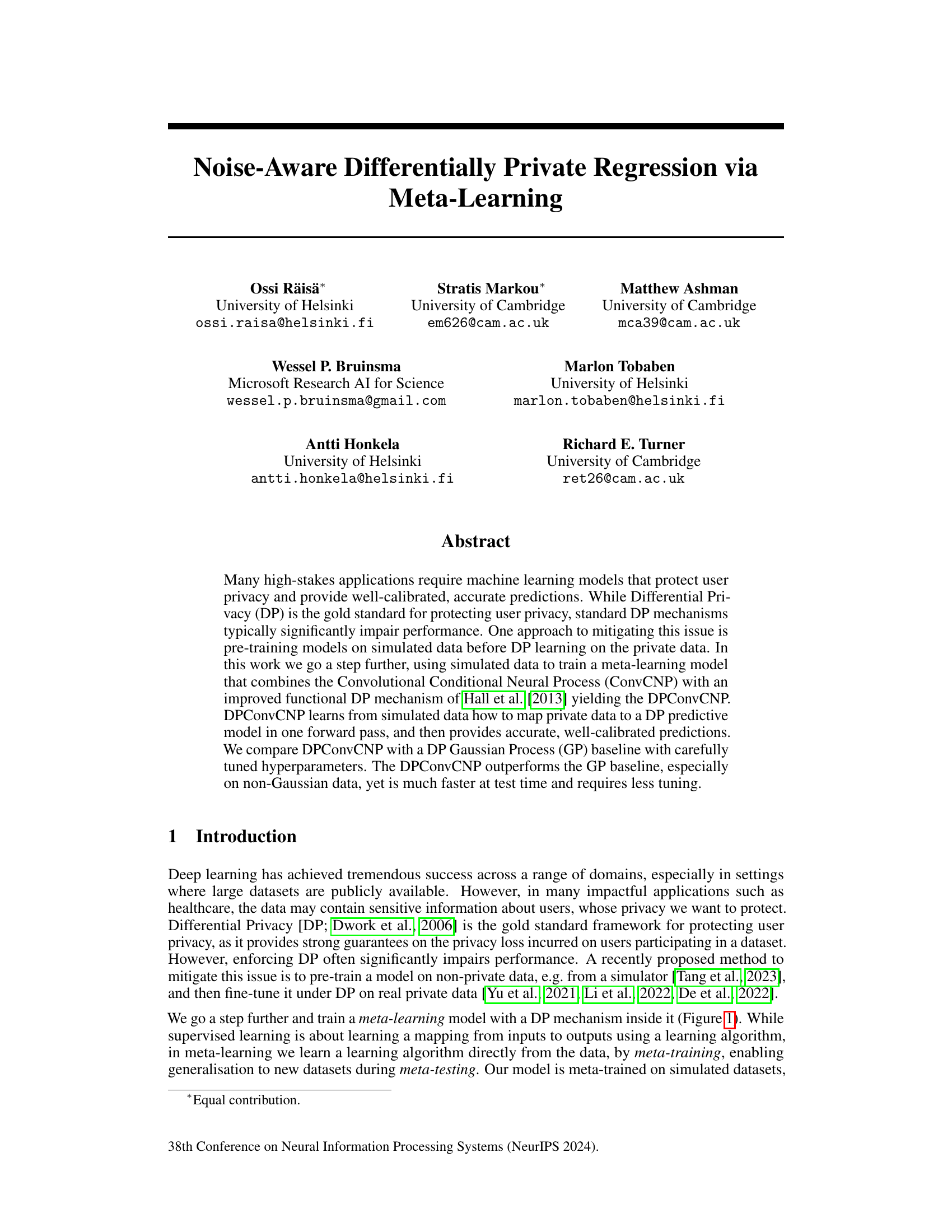

🔼 This figure illustrates the meta-learning process of the proposed DPConvCNP model. The left panel shows the training phase using simulated or proxy data. The model learns to map context points to predictions, with a differential privacy (DP) mechanism (clipping and adding noise) integrated into the training loop. This ensures the model learns to handle noisy data and makes well-calibrated predictions even under DP constraints. The right panel shows the testing phase, applying the trained model to real sensitive data with the same DP mechanism protecting the context set before prediction, guaranteeing privacy.

read the caption

Figure 1: Meta-training (left) and meta-testing (right) using our method. We train a model on multiple tasks with non-private (simulated or proxy) data to predict on target (t) points using the context (c) points. Crucially, by including a DP mechanism, which clips and adds noise to the data during training, the parameter updates (dashed arrow) teach the model to make well-calibrated and accurate predictions in the presence of DP noise. At test time, we deploy the model on real data using the same mechanism, which protects the context set with DP guarantees.

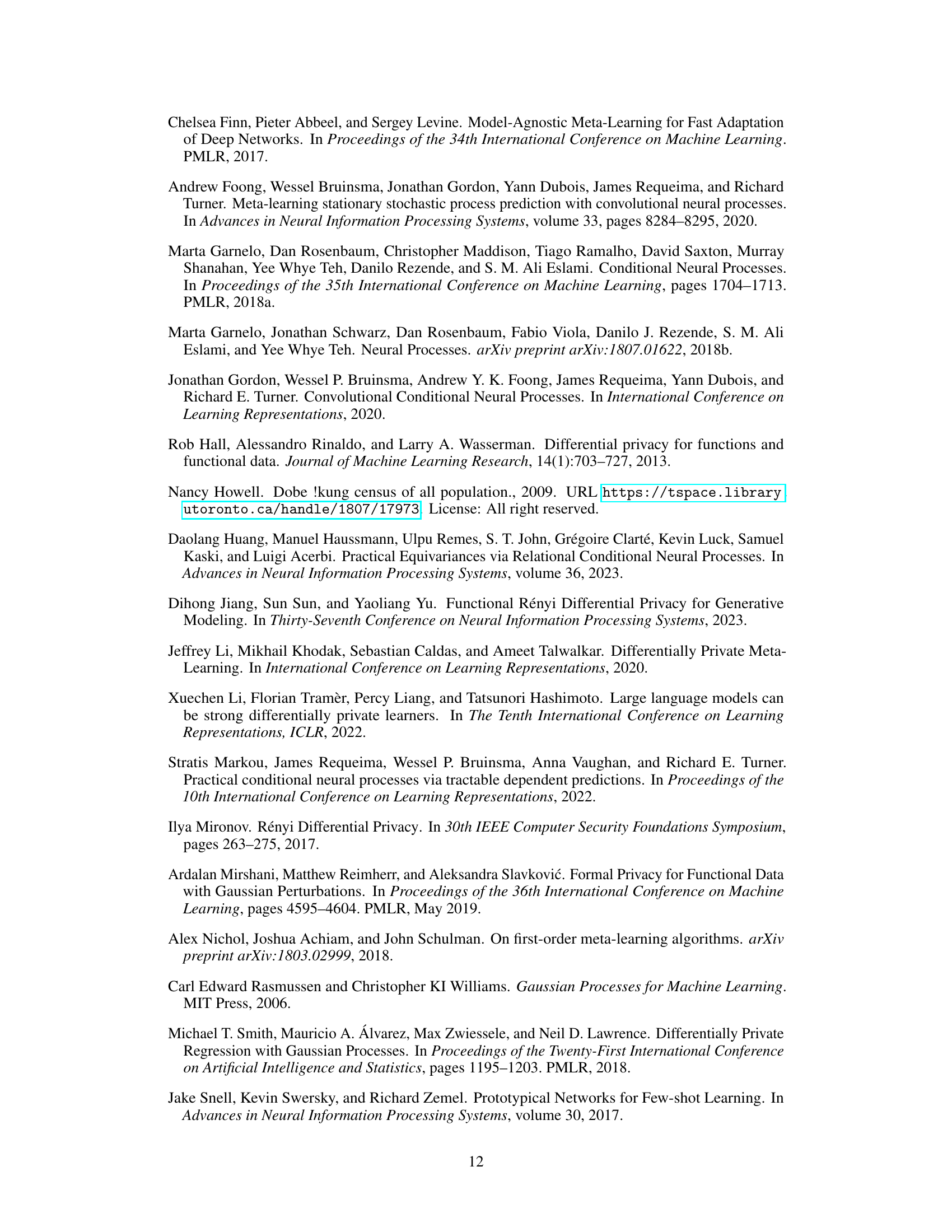

🔼 This table shows the ranges of hyperparameters used for Bayesian optimization in the DP-SVGP baseline model. The hyperparameters are categorized into DP-SGD parameters (for the differentially private optimization process) and initial model parameters (including kernel hyperparameters and likelihood parameters). Minimum and maximum values for each hyperparameter are specified, showing the search space explored during the optimization process.

read the caption

Table S1: The ranges of DP-SGD hyperparameter settings (upper half) and initial model hyperparameters (lower half) over which Bayesian optimisation is performed for the DP-SVGP baseline.

In-depth insights#

DPConvCNP Model#

The DPConvCNP model is a novel meta-learning approach designed for differentially private regression tasks. It leverages the strength of Convolutional Conditional Neural Processes (ConvCNP) and incorporates a refined functional differential privacy mechanism. Meta-training on simulated data allows the model to learn how to map private data to a differentially private predictive model in a single forward pass during inference. A key advantage is its efficiency; it surpasses Gaussian process baselines in speed and requires less hyperparameter tuning, particularly beneficial in resource-constrained settings. The model’s well-calibrated predictions, even with limited data and modest privacy budgets, showcase its robustness and effectiveness for high-stakes applications requiring both accuracy and privacy. The integration of the improved functional DP mechanism ensures the protection of user privacy while maintaining prediction quality.

Meta-Learning DP#

Meta-learning applied to differentially private (DP) mechanisms offers a powerful approach to improve DP model accuracy and calibration. Instead of directly training a DP model on private data, which often leads to poor performance due to noise addition, meta-learning leverages pre-training on simulated or proxy datasets. This allows the model to learn how to map noisy private data to accurate predictions. The key is to incorporate the DP mechanism (noise addition, clipping) into the meta-training loop. By doing so, the model learns the underlying data distribution and how to make well-calibrated predictions in the presence of the DP noise. This contrasts with approaches where DP is applied solely at test time, creating a training-test mismatch and poor calibration. Meta-learning enables adaptation to various privacy budgets (epsilon, delta) and data characteristics, improving generalization to new datasets and avoiding computationally expensive hyperparameter tuning at test time. However, limitations exist regarding the model’s ability to capture dependencies between target variables and the sensitivity of the meta-learning model to the quality of the simulated datasets. Despite these limitations, meta-learning offers a promising direction for enhancing the applicability and performance of DP in scenarios with limited data and strict privacy requirements.

Improved DP Mech#

The heading ‘Improved DP Mech’ likely refers to advancements in the core mechanism of Differential Privacy (DP). Standard DP methods often suffer from a significant performance trade-off due to the addition of noise to protect privacy. An ‘Improved DP Mech’ would focus on mitigating this issue. This could involve refining existing mechanisms like the Gaussian or Laplace mechanisms to reduce the amount of noise required while maintaining privacy guarantees. New theoretical frameworks or advanced techniques might be introduced to better control the noise addition process, perhaps by tailoring the noise to the specific data characteristics or utilizing adaptive noise scaling strategies. Advanced composition theorems are another potential area of improvement, as they determine the privacy loss when applying multiple DP mechanisms. Improvements here would lead to more flexible and efficient use of DP in complex machine learning pipelines. Ultimately, the improvements aim to make DP more practical for real-world applications by reducing the utility cost associated with privacy protection.

Sim-to-Real Tasks#

The ‘Sim-to-Real Tasks’ section likely evaluates the model’s generalization ability by bridging the gap between simulated and real-world data. This is crucial because models trained solely on simulated data often fail to perform well on real data due to domain mismatch. The experiment likely involves training the model on synthetic data generated from a known process (e.g., a Gaussian process), then testing its performance on a real-world dataset. Key aspects to analyze here would be the model’s accuracy, calibration (how well its uncertainty estimates reflect true uncertainty), and robustness to noise and variations between the simulated and real datasets. The choice of the real-world dataset and the metrics used are important indicators of the problem’s difficulty and practical relevance. Successful performance on the sim-to-real tasks would strongly suggest that the model has learned generalizable features, rather than merely memorizing patterns specific to the simulated data. A comparative analysis against established baselines (e.g., a carefully tuned Gaussian process) is important for assessing the model’s effectiveness in the context of the problem, especially concerning the runtime and computational costs involved.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work are abundant. Extending the DPConvCNP to handle dependencies between target outputs is crucial for many real-world applications, perhaps through incorporating latent variable neural processes or other architectures better suited for structured data. Investigating the impact of simulator diversity on sim-to-real generalization is key—balancing the need for diverse training data against the potential for increased uncertainty in predictions. A deeper exploration of the trade-offs between privacy parameters (ε, δ) and model performance, along with developing more sophisticated methods for selecting optimal privacy hyperparameters would improve practical applicability. Finally, rigorous theoretical analysis of the improved functional DP mechanism under broader conditions than currently explored is needed, to solidify the theoretical foundations and guide further advancements.

More visual insights#

More on figures

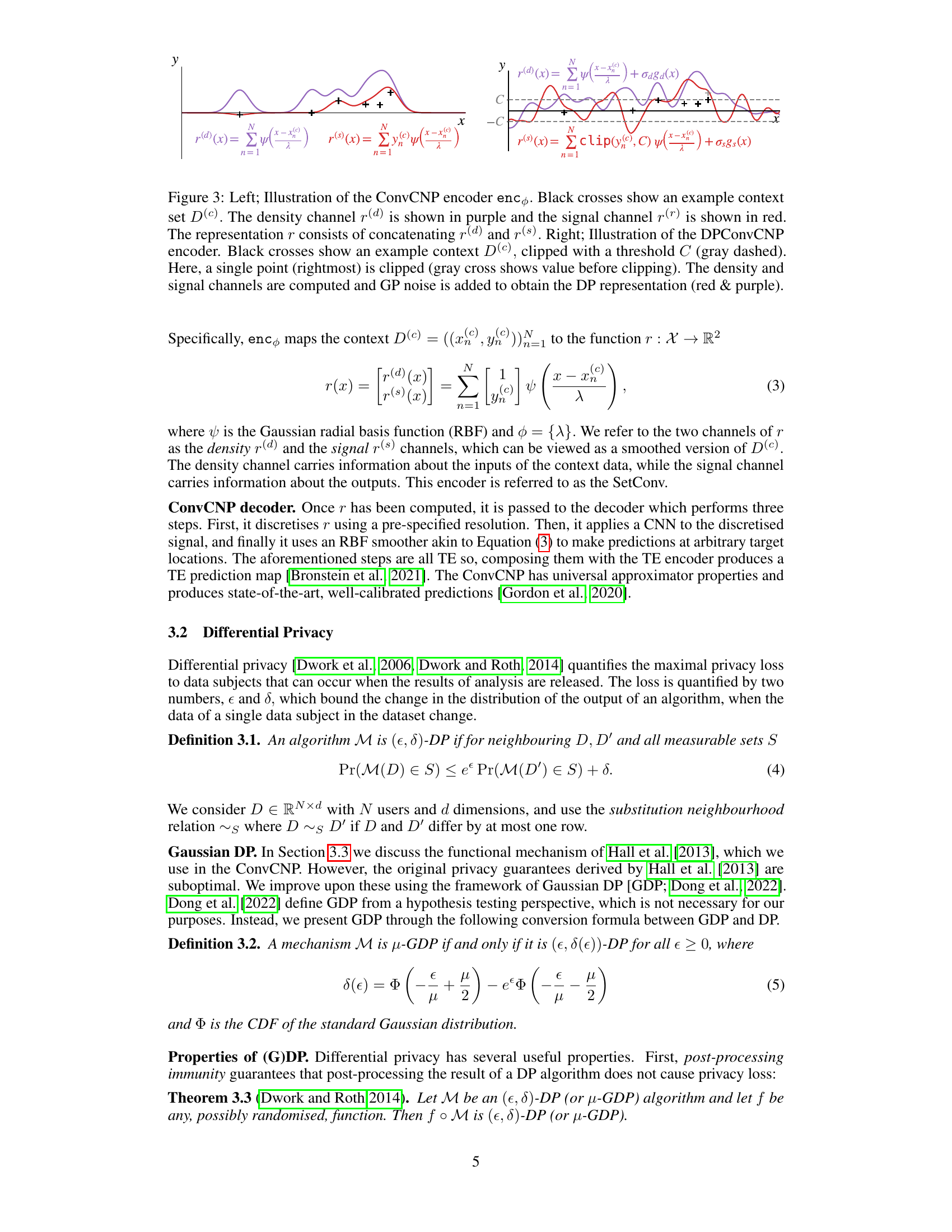

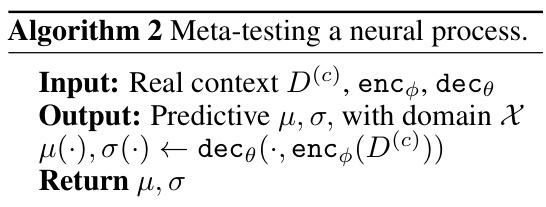

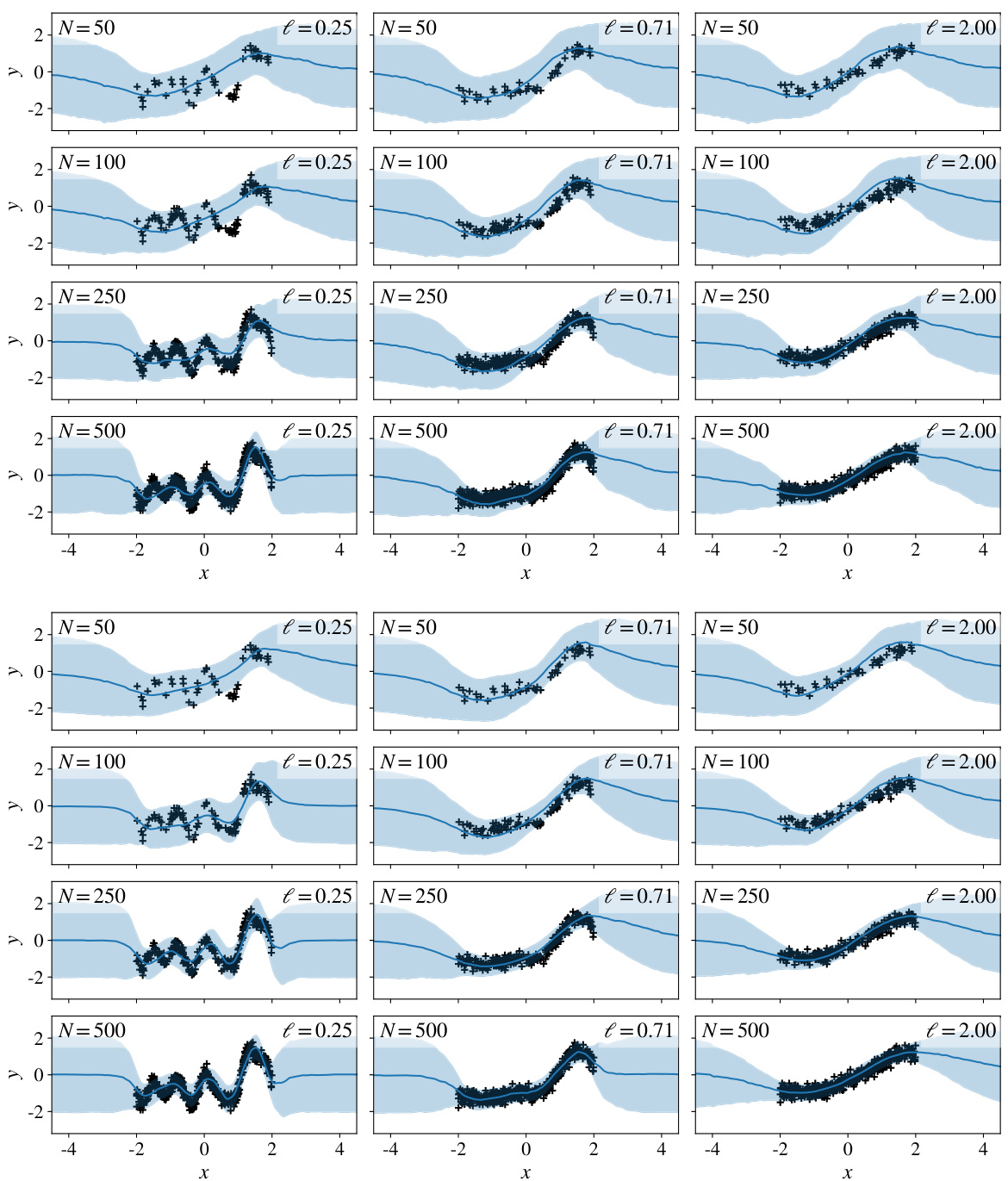

🔼 The figure shows the results of training a model with a differential privacy (DP) mechanism. The model is trained on data where the context points are protected using DP. Despite the noise added for privacy, the model produces predictions that are very close to the optimal predictions achievable without DP, demonstrating the effectiveness of the DP mechanism and the model’s ability to learn from noisy data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Training our proposed model with a DP mechanism inside it, enables the model to make accurate well-calibrated predictions, even for modest privacy budgets and dataset sizes. Here, the context data (black) are protected with different (€, δ) DP budgets as indicated. The model makes predictions (blue) that are remarkably close to the optimal (non-private) Bayes predictor.

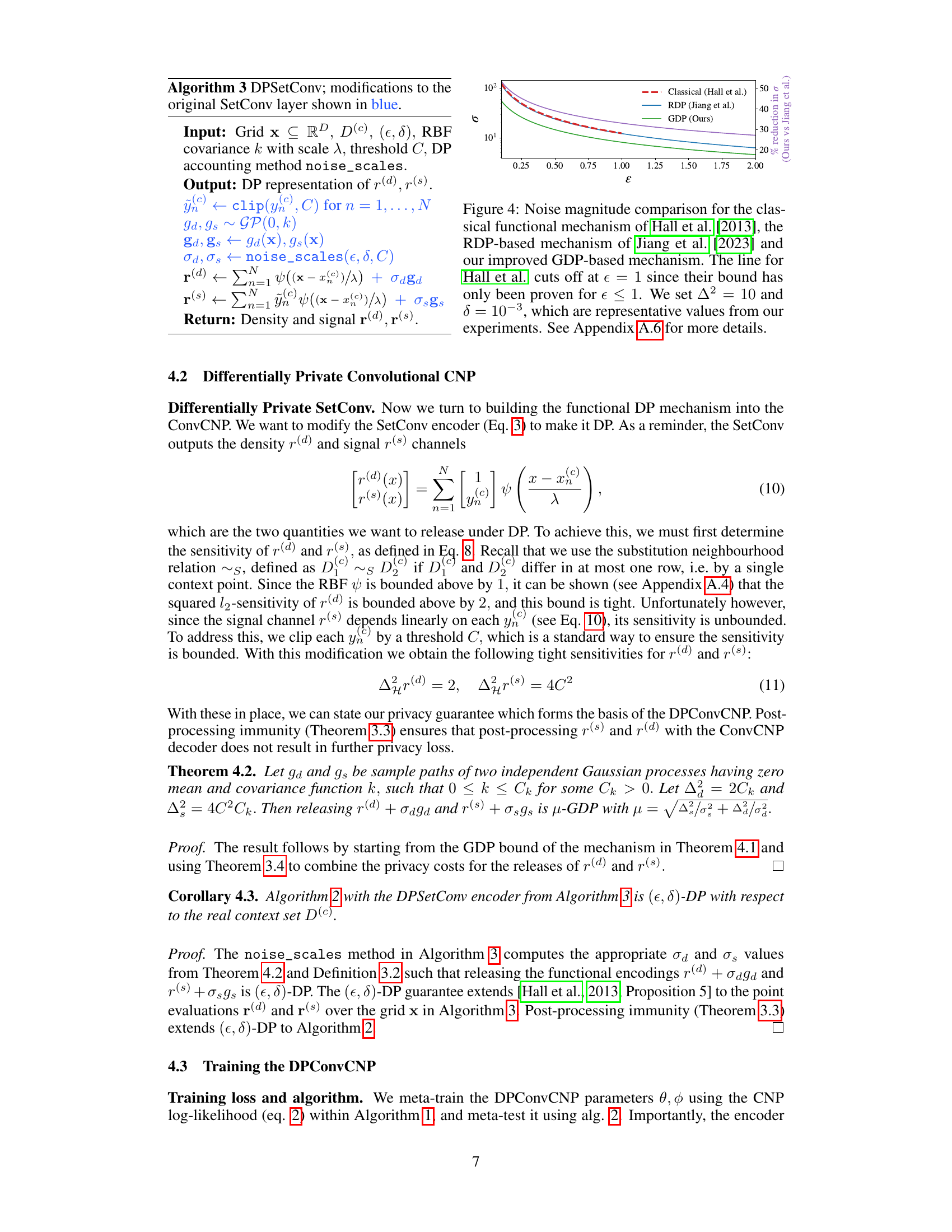

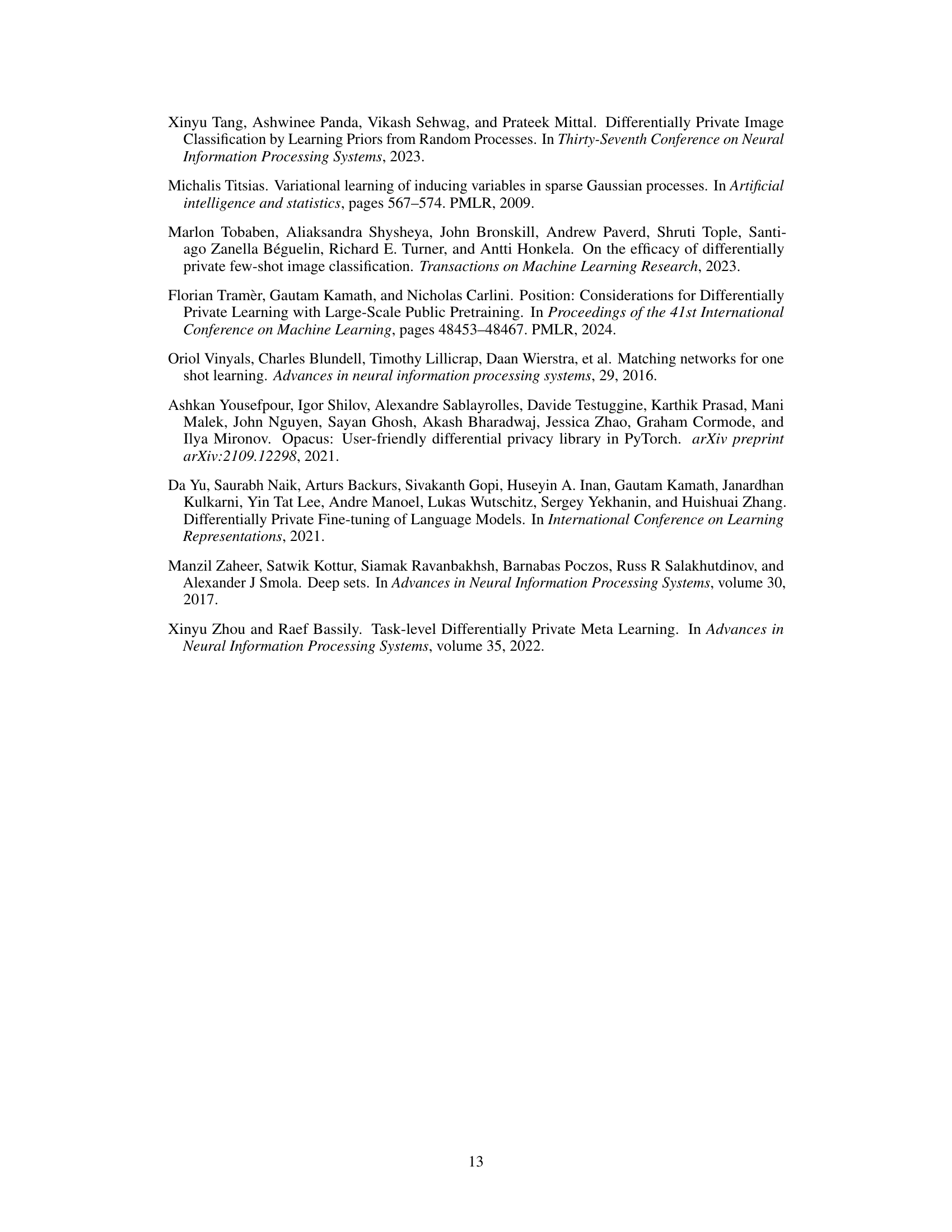

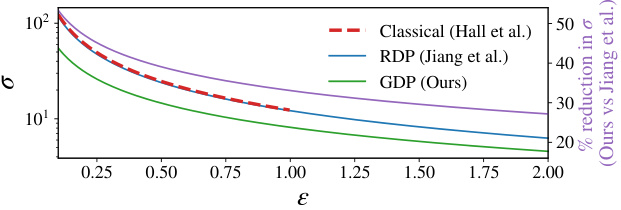

🔼 This figure compares noise magnitudes (σ) required to achieve the same privacy guarantees (ε,δ) using three different DP mechanisms: the classical functional mechanism, the RDP mechanism, and the proposed GDP mechanism. The GDP mechanism consistently requires significantly less noise than the other two methods, particularly at higher epsilon values. The plot illustrates the improvement in noise reduction achieved by using the GDP mechanism compared to the RDP mechanism.

read the caption

Figure 4: Noise magnitude comparison for the classical functional mechanism of Hall et al. [2013], the RDP-based mechanism of Jiang et al. [2023] and our improved GDP-based mechanism. The line for Hall et al. cuts off at ε = 1 since their bound has only been proven for ε ≤ 1. We set Δ² = 10 and δ = 10⁻³, which are representative values from our experiments. See Appendix A.6 for more details.

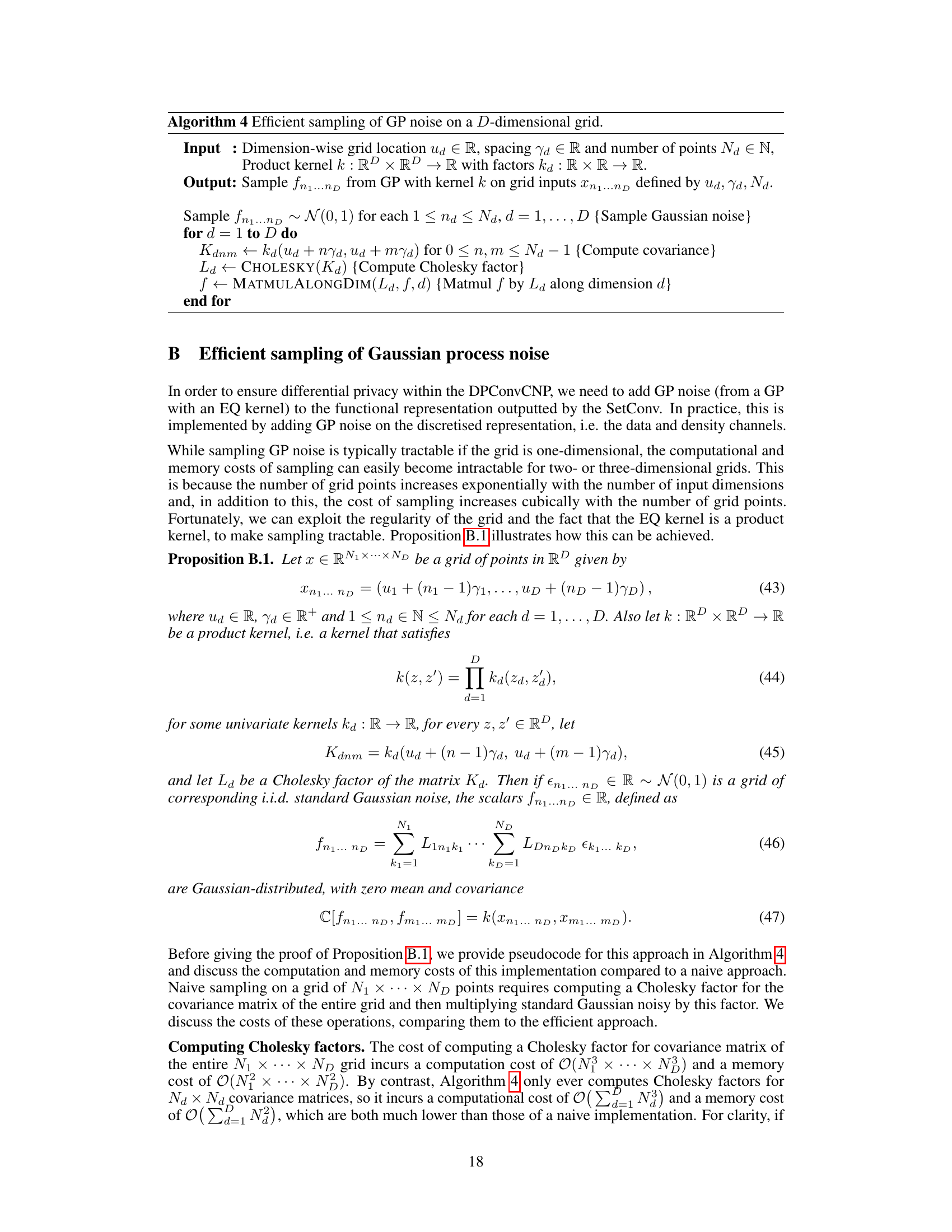

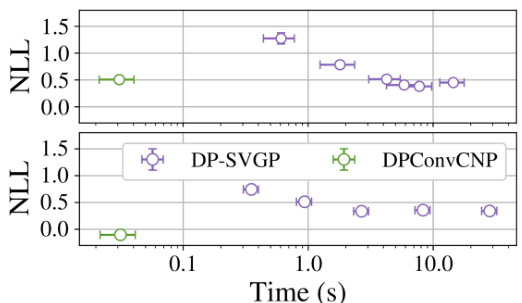

🔼 The figure compares the inference time of DPConvCNP and DP-SVGP models on Gaussian and non-Gaussian data. The DP-SVGP’s inference time is significantly longer than that of DPConvCNP, especially for larger datasets. The DP-SVGP time increases as the number of DP-SGD steps increases, representing a quality/speed trade-off.

read the caption

Figure 5: Deployment-time comparison on Gaussian (top) and non-Gaussian (bottom) data. We ran the DP-SVGP for different numbers of DP-SGD steps to determine a speed versus quality-of-fit tradeoff. Reporting 95% confidence intervals.

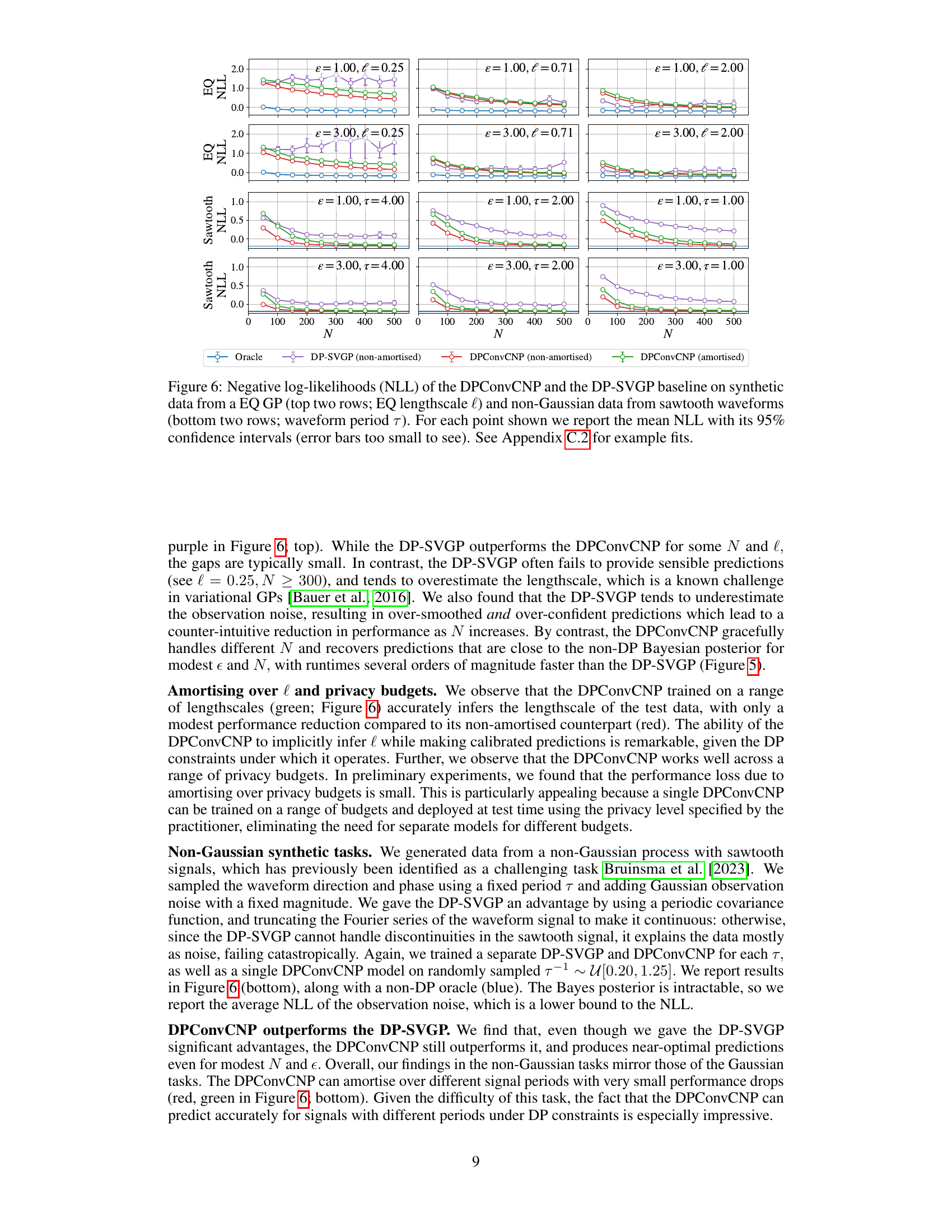

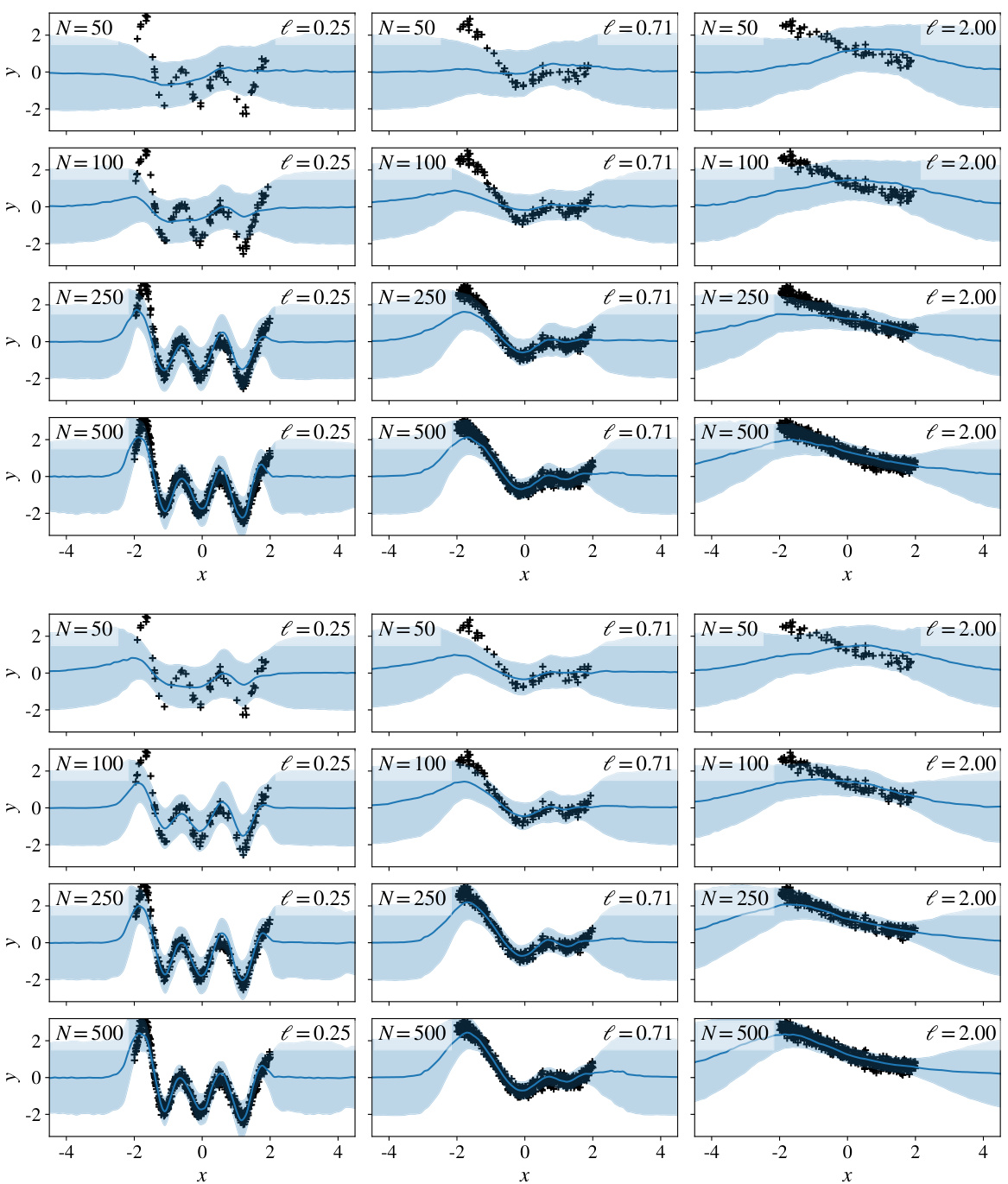

🔼 This figure displays the negative log-likelihood (NLL) performance comparison between DPConvCNP and DP-SVGP on synthetic datasets generated from both Gaussian (EQ GP) and non-Gaussian (sawtooth waveforms) processes. The top two rows show results for the Gaussian process, varying the lengthscale (l) of the EQ kernel, while the bottom two rows show results for the sawtooth process, varying the period (τ). Different privacy budgets (ε) and dataset sizes (N) are evaluated. The plots illustrate how both models perform under different conditions and highlight the DPConvCNP’s ability to handle non-Gaussian data effectively.

read the caption

Figure 6: Negative log-likelihoods (NLL) of the DPConvCNP and the DP-SVGP baseline on synthetic data from a EQ GP (top two rows; EQ lengthscale l) and non-Gaussian data from sawtooth waveforms (bottom two rows; waveform period τ). For each point shown we report the mean NLL with its 95% confidence intervals (error bars too small to see). See Appendix C.2 for example fits.

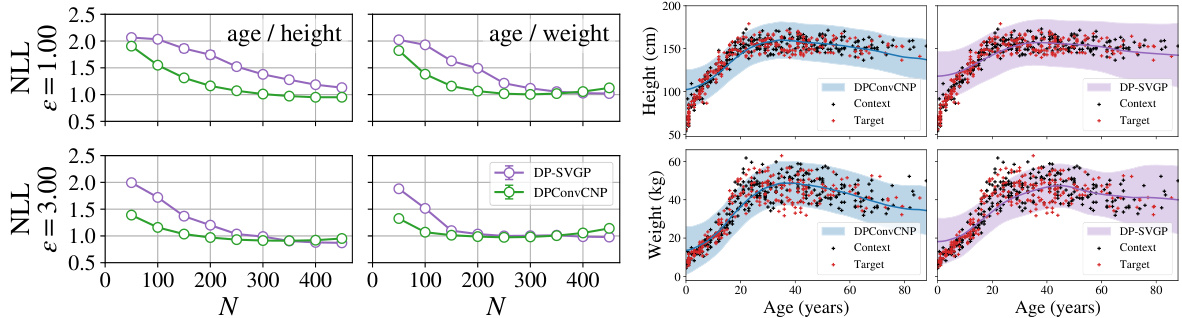

🔼 This figure compares the performance of DPConvCNP and DP-SVGP on a sim-to-real task using the !Kung dataset. The left panels show negative log-likelihood (NLL) results for predicting height and weight from age, demonstrating DPConvCNP’s superior performance, especially with smaller datasets. The right panels visualize example predictions with confidence intervals, highlighting DPConvCNP’s better calibration.

read the caption

Figure 7: Left; Negative log-likelihoods of the DPConvCNP and the DP-SVGP baseline on the sim to real task with the !Kung dataset, predicting individuals' height from their age (left col.) or their weight from their age (right col.). For each point shown here, we partition each dataset into a context and target at random, make predictions, and repeat this procedure 512 times. We report mean NLL with its 95% confidence intervals. Error bars are to small to see here. Right; Example predictions for the DPConvCNP and the DP-SVGP, showing the mean and 95% confidence intervals, with N = 300, € = 1.00, δ = 10-3. The DPConvCNP is visibly better-calibrated than the DP-SVGP.

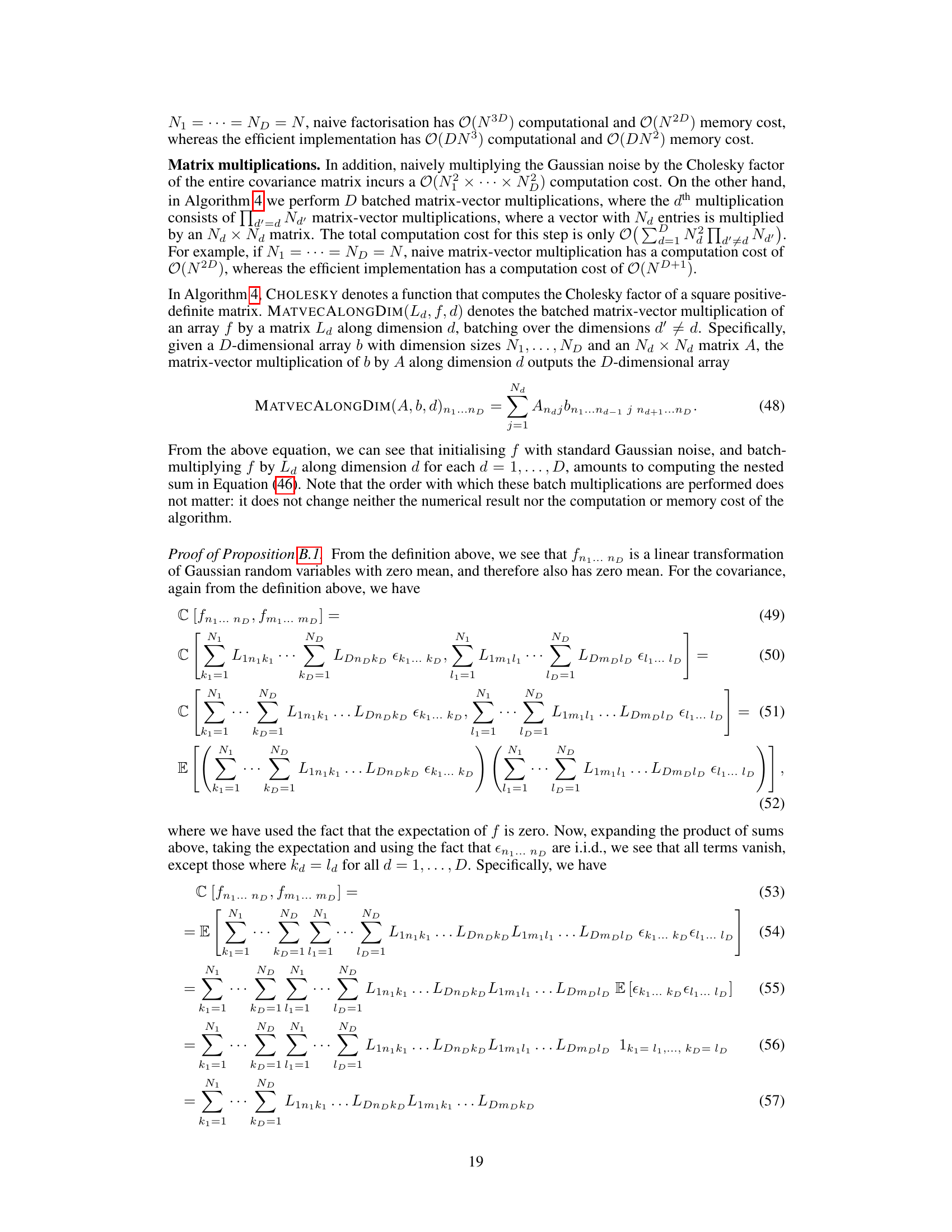

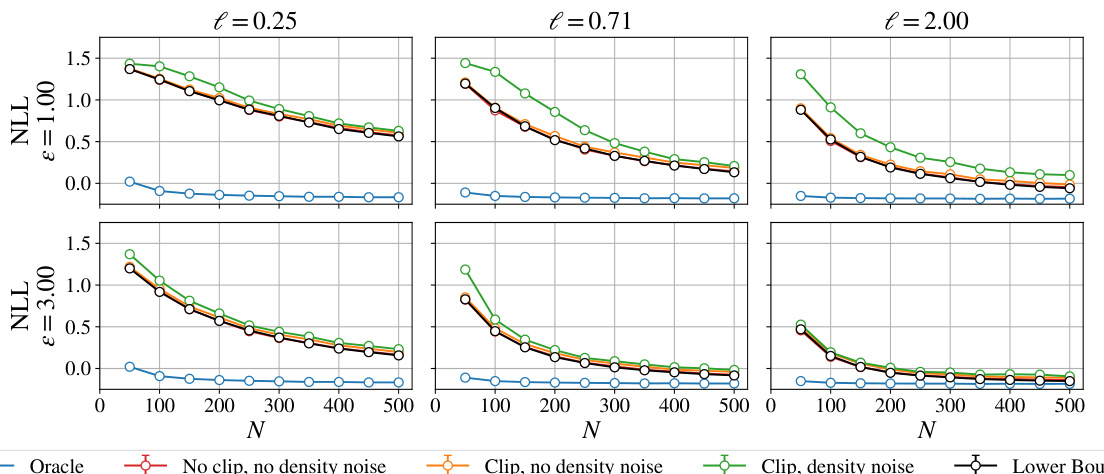

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different DPConvCNP models with varying levels of noise and clipping on a Gaussian process regression task. It shows how the negative log-likelihood (NLL) changes with the number of data points (N) for different privacy budgets (epsilon). The results are compared to the optimal Bayesian posterior (oracle) and a lower bound based on the functional mechanism.

read the caption

Figure S1: DPConvCNP performance on the GP modelling task, where the data are generated using an EQ GP with lengthscale l. We train three models per e, l combination, keeping d = 10−3 fixed as well as the clipping threshold C = 2.00 and noise weight t = 0.50 fixed. Specifically, we train one model where only noise to the signal channel (red; no clip, no density), one model where noise and clipping are applied to the signal channel (orange; clip, no density noise) and another model where noise and clipping to the signal channel as well as noise to the density channel are applied (green; clip, density noise). We also show the NLL of the oracle, non-DP, Bayesian posterior, which is the best average NLL that can be obtained on this task (blue). Lastly, we show a bound to the functional mechanism (black), which is a lower bound on the NLL that can be obtained with the functional mechanism with C = 2.00, t = 0.50 on this task. We used 512 evaluation tasks for each N, l, e combination, and report mean NLLs together with their 95% confidence intervals. Note that the error bars are plotted but are too small to see in the plot.

🔼 The figure shows the well-calibrated predictions of the proposed model (DPConvCNP) even with modest privacy budgets and dataset sizes. The context data (black) is protected with different (ε, δ) DP budgets. The model makes predictions (blue) which are very close to the optimal (non-private) Bayes predictor.

read the caption

Figure 2: Training our proposed model with a DP mechanism inside it, enables the model to make accurate well-calibrated predictions, even for modest privacy budgets and dataset sizes. Here, the context data (black) are protected with different (€, δ) DP budgets as indicated. The model makes predictions (blue) that are remarkably close to the optimal (non-private) Bayes predictor.

🔼 The figure shows the well-calibrated predictions of the DPConvCNP model trained with the differential privacy mechanism. Even with small datasets and modest privacy budgets, the model’s predictions are very close to the optimal non-private Bayes predictor. This demonstrates that the model effectively learns to produce accurate and calibrated predictions in the presence of differential privacy noise.

read the caption

Figure 2: Training our proposed model with a DP mechanism inside it, enables the model to make accurate well-calibrated predictions, even for modest privacy budgets and dataset sizes. Here, the context data (black) are protected with different (€, δ) DP budgets as indicated. The model makes predictions (blue) that are remarkably close to the optimal (non-private) Bayes predictor.

🔼 The figure shows the well-calibrated predictions of the proposed DPConvCNP model compared to the optimal Bayes predictor (non-private). The context data is protected using Differential Privacy (DP) with varying privacy budgets (epsilon and delta). Even with modest privacy budgets and dataset sizes, the model makes accurate predictions, demonstrating the effectiveness of incorporating the DP mechanism into the meta-learning process.

read the caption

Figure 2: Training our proposed model with a DP mechanism inside it, enables the model to make accurate well-calibrated predictions, even for modest privacy budgets and dataset sizes. Here, the context data (black) are protected with different (€, δ) DP budgets as indicated. The model makes predictions (blue) that are remarkably close to the optimal (non-private) Bayes predictor.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of DPConvCNP and DP-SVGP on synthetic datasets generated from both Gaussian (EQ GP) and non-Gaussian (sawtooth waveforms) processes. The top two rows show results for Gaussian data with varying lengthscales (l), while the bottom two rows show results for non-Gaussian data with varying periods (τ). Different privacy budgets (ε) and dataset sizes (N) are also tested. The plot displays the negative log-likelihood (NLL), a measure of predictive accuracy, with 95% confidence intervals represented by error bars (though they are too small to be visible in the figure). Appendix C.2 provides detailed example fits for further analysis.

read the caption

Figure 6: Negative log-likelihoods (NLL) of the DPConvCNP and the DP-SVGP baseline on synthetic data from a EQ GP (top two rows; EQ lengthscale l) and non-Gaussian data from sawtooth waveforms (bottom two rows; waveform period τ). For each point shown we report the mean NLL with its 95% confidence intervals (error bars too small to see). See Appendix C.2 for example fits.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of DPConvCNP and DP-SVGP on synthetic datasets generated from both Gaussian (EQ) and non-Gaussian (sawtooth) processes. The top two rows show results for Gaussian processes with varying lengthscales (l), while the bottom two rows show results for non-Gaussian sawtooth waveforms with varying periods (τ). For each combination of data type, lengthscale/period, privacy budget (ε), and dataset size (N), the negative log-likelihood (NLL) and its 95% confidence interval are reported. The figure demonstrates that DPConvCNP is competitive with DP-SVGP in Gaussian settings, and outperforms it significantly in non-Gaussian settings.

read the caption

Figure 6: Negative log-likelihoods (NLL) of the DPConvCNP and the DP-SVGP baseline on synthetic data from a EQ GP (top two rows; EQ lengthscale l) and non-Gaussian data from sawtooth waveforms (bottom two rows; waveform period τ). For each point shown we report the mean NLL with its 95% confidence intervals (error bars too small to see). See Appendix C.2 for example fits.

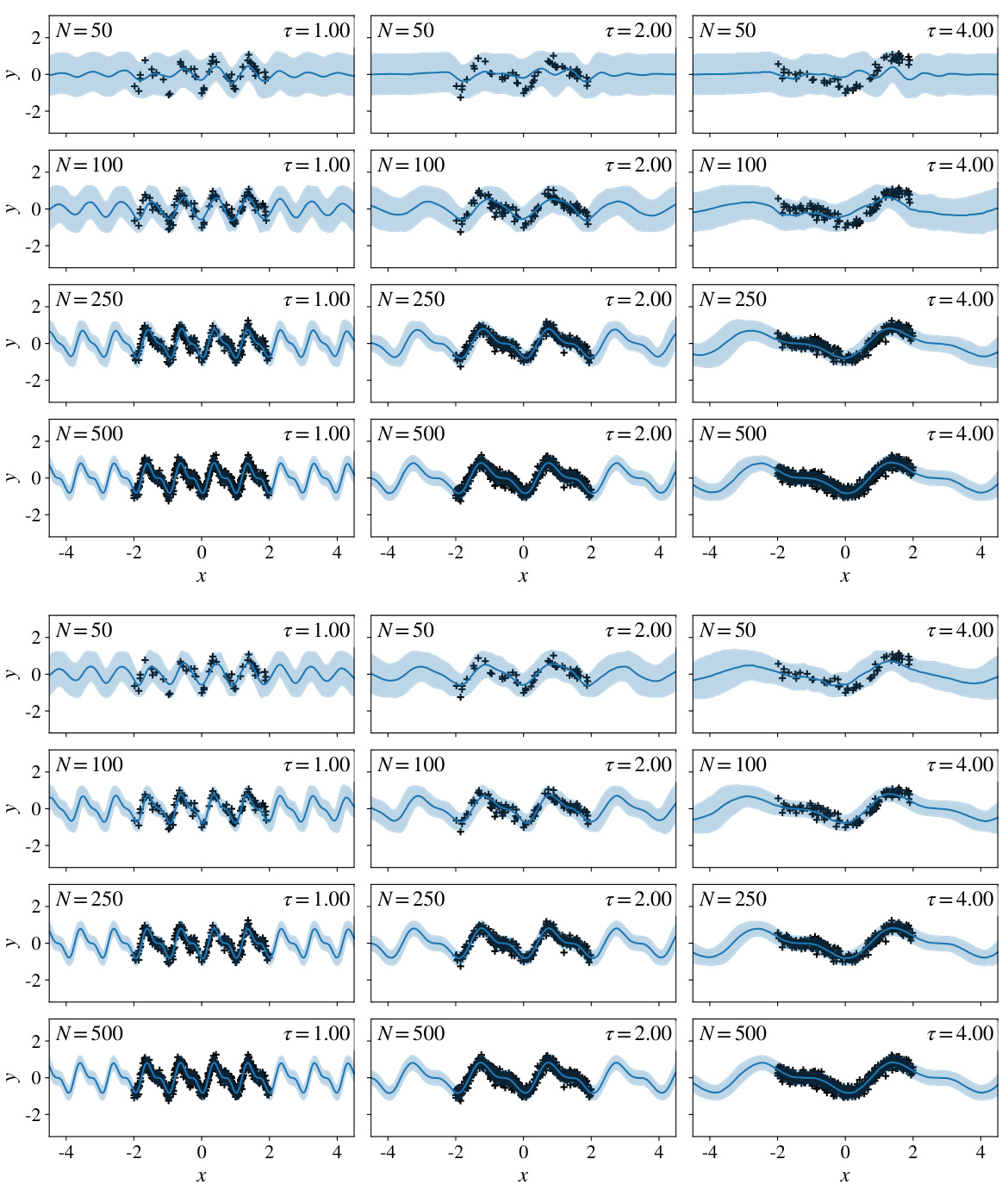

🔼 The figure displays negative log-likelihood (NLL) results for both the EQ and sawtooth synthetic tasks. Two privacy budgets (∈ = 0.33 and ∈ = 1.00) and two delta values (δ = 10⁻⁵ and δ = 10⁻³) are compared for both amortised and non-amortised models, illustrating the performance of the DPConvCNP across various privacy settings and numbers of context points (N). The results are juxtaposed against an oracle (non-private) model’s performance.

read the caption

Figure S6: Additional results using the DPConvCNP on the EQ and sawtooth synthetic tasks with stricter DP parameters, namely all combinations of ∈ = {1/3, 1} and δ = {10−5,10-3}. The overall setup in this figure is identical to that in Figure 6, except the amortised DPConvCNP is trained on randomly chosen ∈ ~ U[1/3, 1] and fixed δ = 10−5 or 10−3, and the non-amortised DPConvCNP models are trained on ∈ and δ values as indicated on the plots. Then, both amortised and non-amortised models are evaluated with the parameters shown on the plots. The DP-SVGP baseline was not run due to time constraints in the rebuttal period: it is significantly slower and more challenging to optimise than the DPConvCNP. We note that the amortisation gap, due to training a model to handle a continuous range of ∈ values, is negligible. We also note that as the number of context points N increases, the performance of the DPConvCNP approaches that of the oracle predictors.

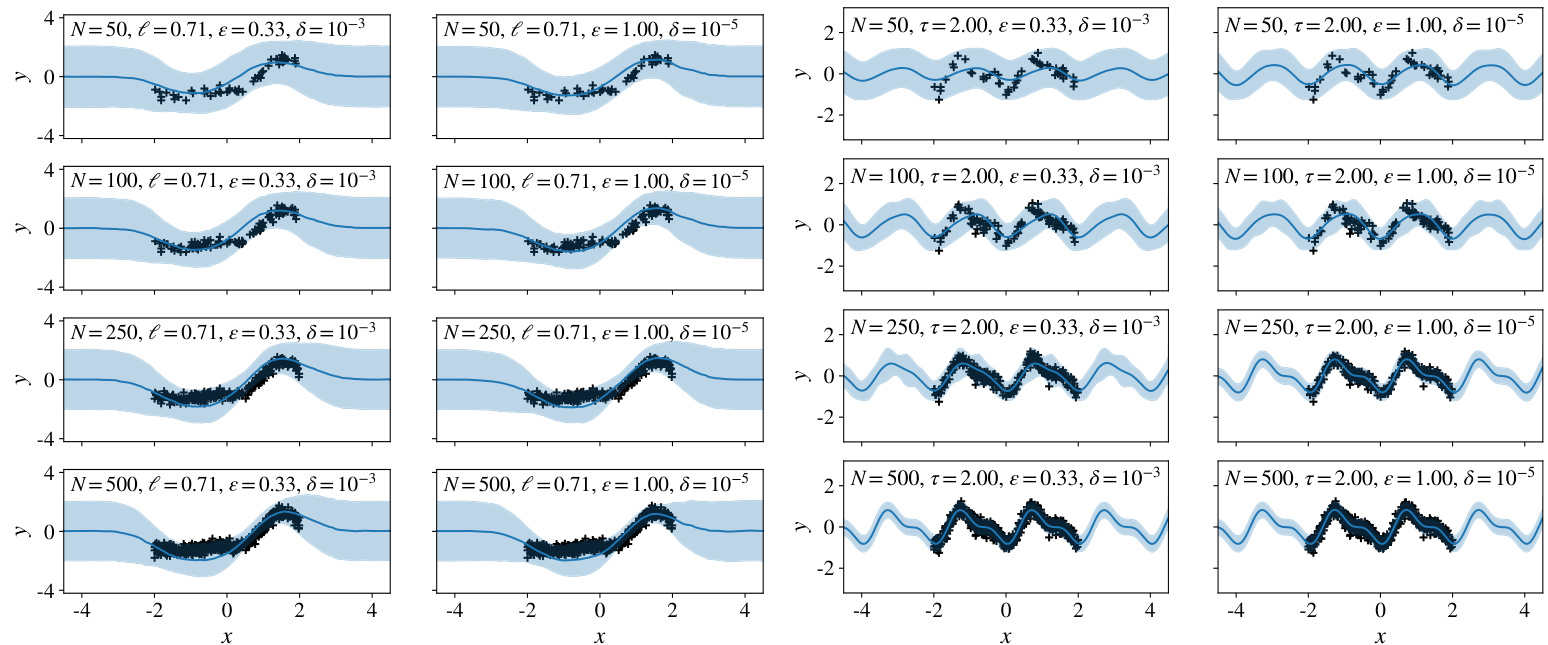

🔼 This figure shows example model fits from the DPConvCNP on synthetic EQ and sawtooth data with stricter DP parameters. The left panel displays fits for the EQ data (amortized DPConvCNP), while the right panel shows fits for sawtooth data. The results demonstrate that the model generates sensible predictions even with stringent privacy constraints.

read the caption

Figure S7: Illustrations of model fits on the synthetic EQ and sawtooth tasks, using stricter DP paramters, for different context sizes N. Left: model fits of amortised DPConvCNPs trained on EQ data using ∈ ~ U[1/3, 1] and fixed δ = 10-3 (first column) or δ = 10-5 (second column) and evaluated on the DP parameters shown in the plots. Right: same as the left plot, except the data generating process is the sawtooth waveform rather than an EQ Gaussian process. We observe that the DPConvCNP produces sensible predictions even under strict privacy settings.

Full paper#