TL;DR#

Bayesian persuasion, while offering powerful tools for influencing agents, often relies on idealized assumptions of perfectly rational agents. This paper challenges the limitations of existing Bayesian persuasion models by considering scenarios where the agent’s response might deviate from perfect rationality. The authors find that existing methods and techniques, which are mainly based on the principle of revelation, are inadequate for this problem. Specifically, it can significantly reduce the effectiveness of the sender’s strategy if the receiver’s responses are not perfectly aligned with the sender’s goals.

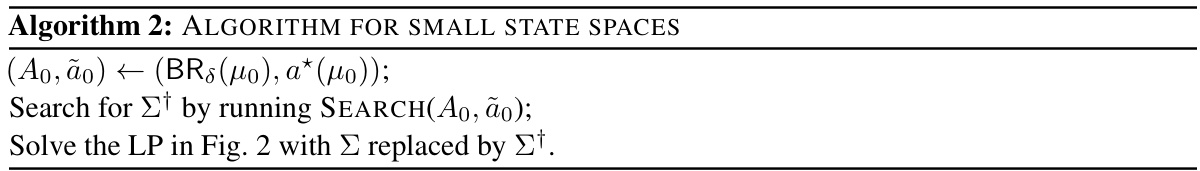

This research introduces novel algorithmic approaches to address the challenges posed by approximate best responses in Bayesian persuasion. The key methods proposed include a linear program (LP) formulation that enables calculating optimal strategies, efficient algorithms tailored for instances with small state or action spaces, and a quasi-polynomial-time approximation scheme (QPTAS) for handling general cases. The authors also prove the NP-hardness of the general problem, offering a theoretical understanding of its complexity. These contributions advance the field by providing both practical algorithms and theoretical insights, enhancing the usability and applicability of Bayesian persuasion in realistic settings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it tackles the challenge of designing robust strategies in Bayesian persuasion when the receiver’s response is not perfectly rational. This is a significant advancement in the field, as it moves beyond the idealized assumptions of the classical model and provides more practical solutions for real-world applications. The computational algorithms and hardness results presented will be of great use to computer scientists working on the implementation and application of Bayesian persuasion, while the new algorithmic ideas can lead to broader impact on other principal-agent problems where robustness is desired.

Visual Insights#

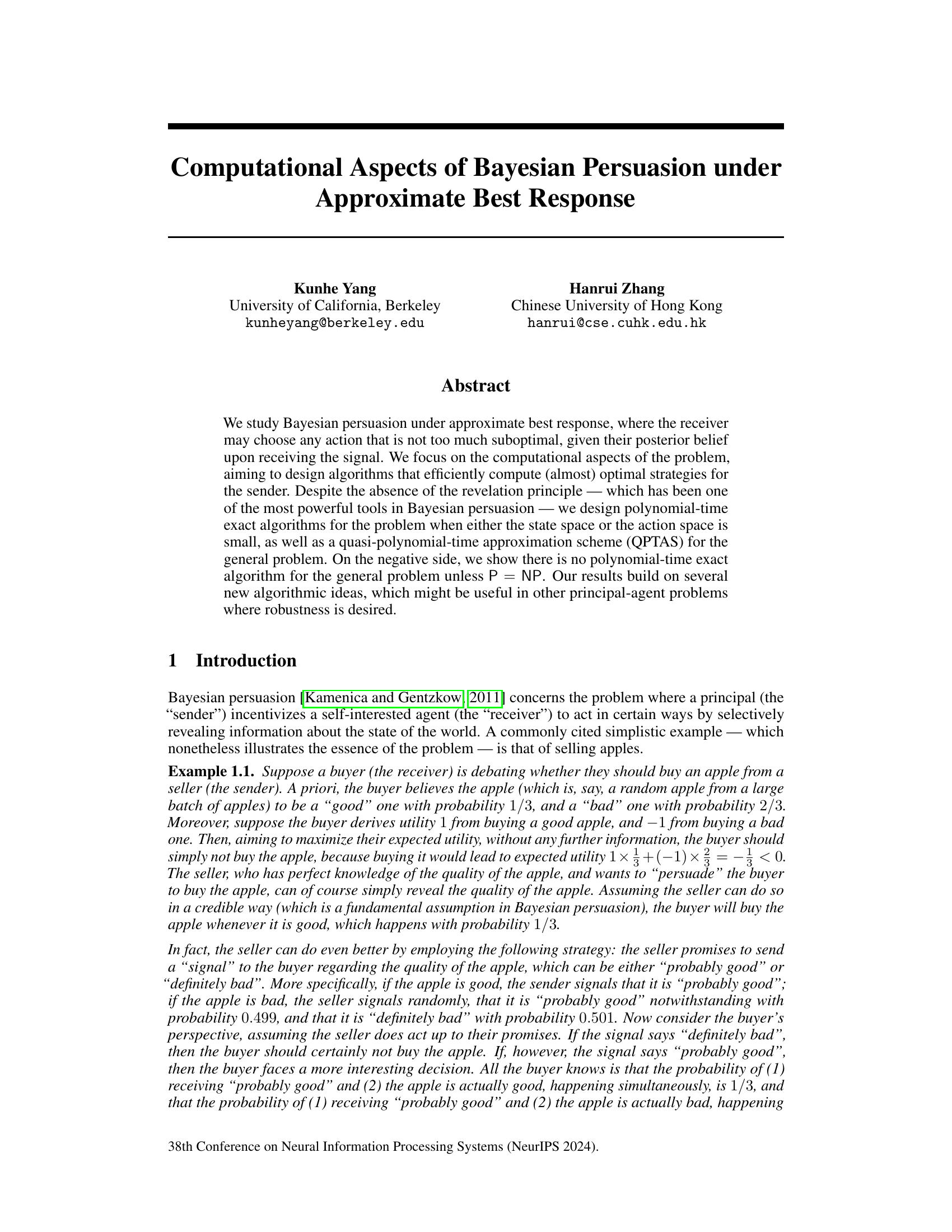

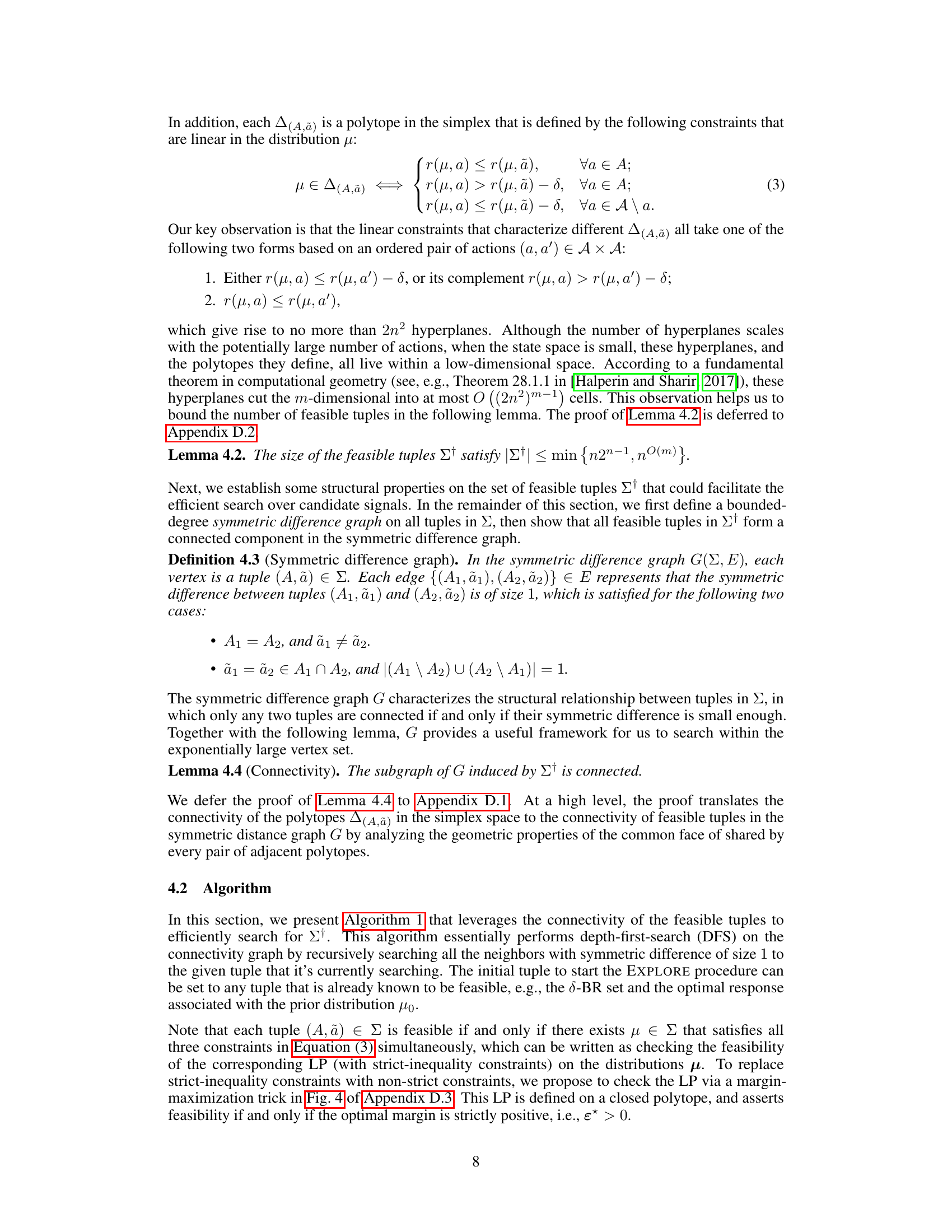

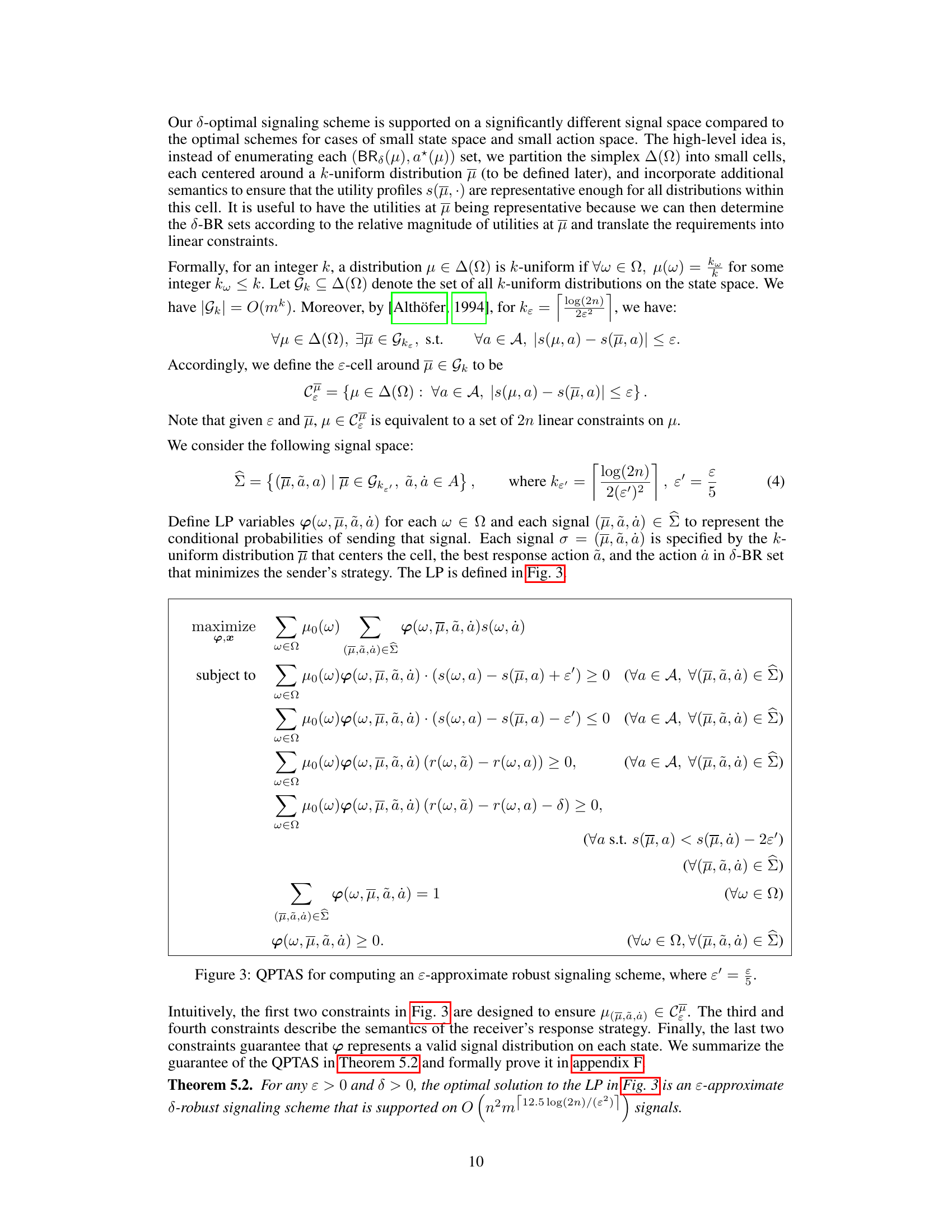

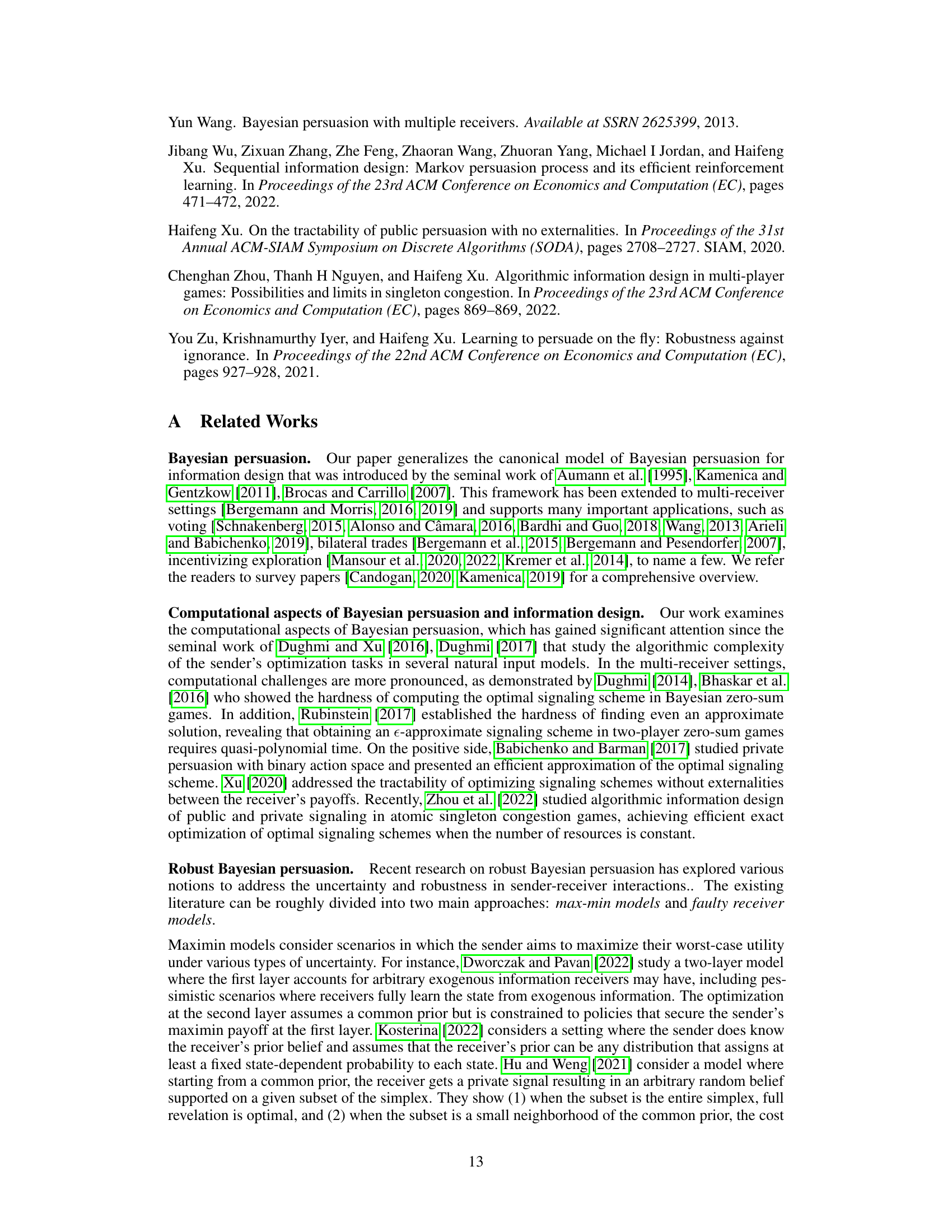

🔼 This figure shows a relaxed linear program (LP) formulation used to compute the optimal robust signaling scheme. The relaxation simplifies the original, more complex program by removing strict inequality constraints, making it easier to solve. While a relaxation, the optimal objective value of this relaxed LP still provides an upper bound for the sender’s optimal robust utility. Importantly, this relaxed LP’s solution also helps precisely characterize the optimal robust signaling scheme.

read the caption

Figure 2: Relaxed LP for the optimal robust signaling scheme

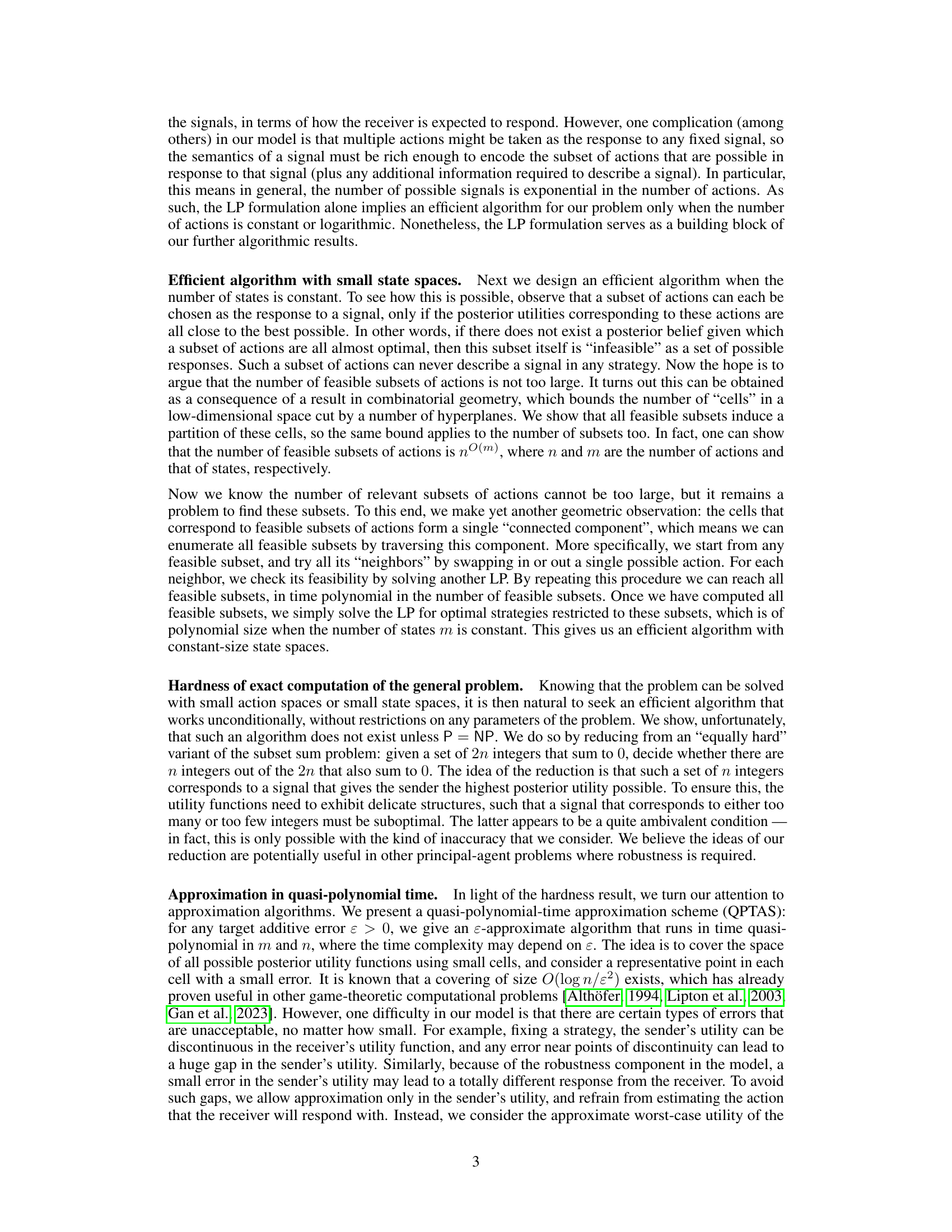

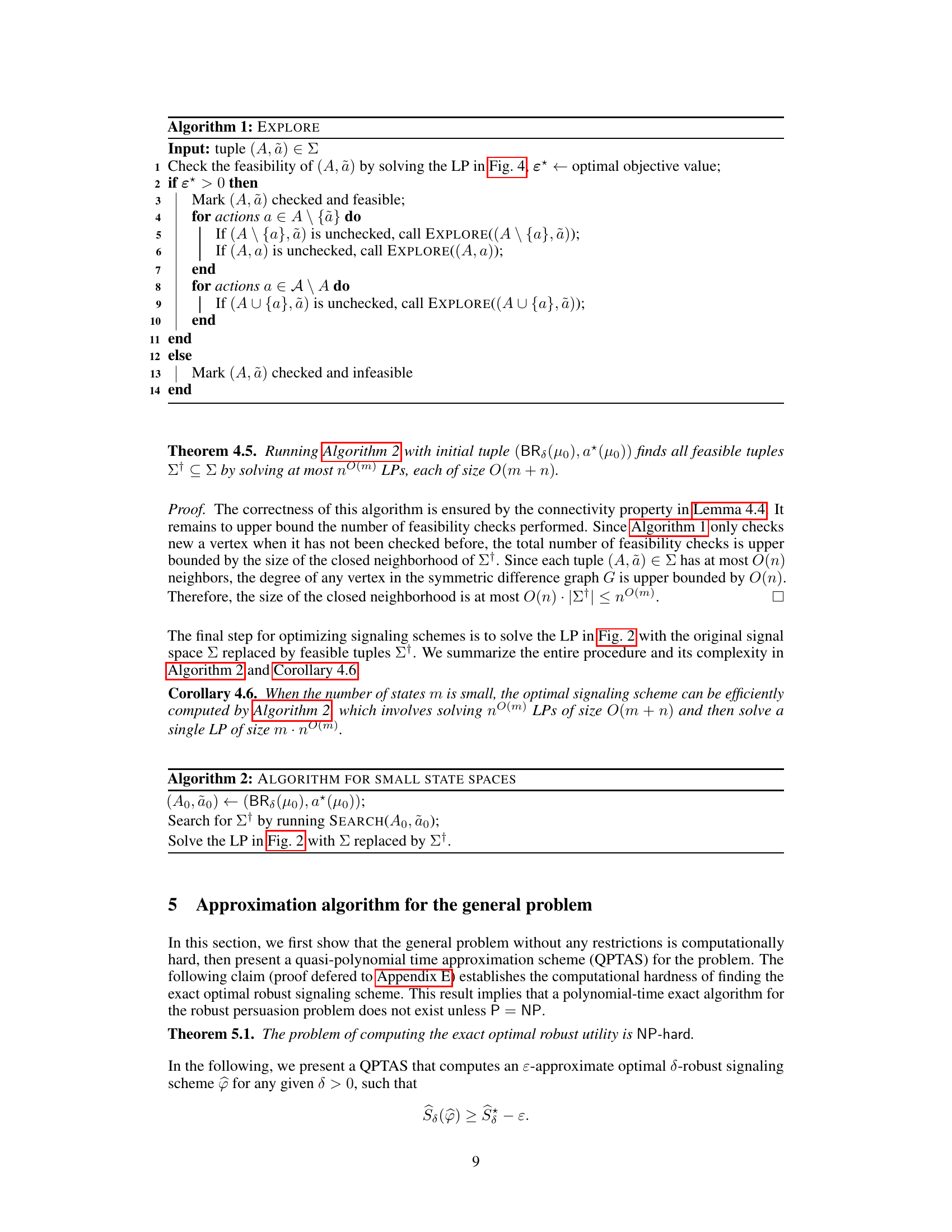

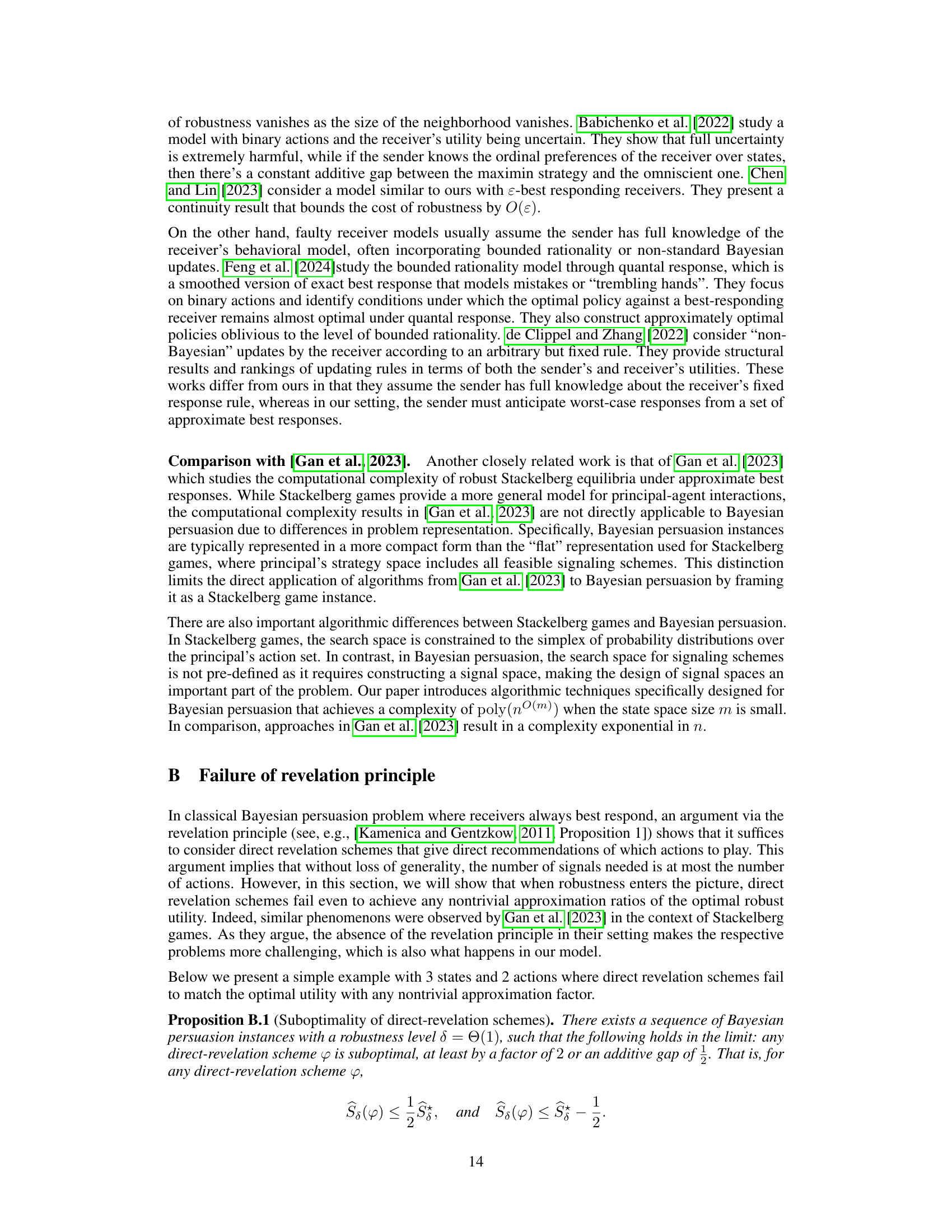

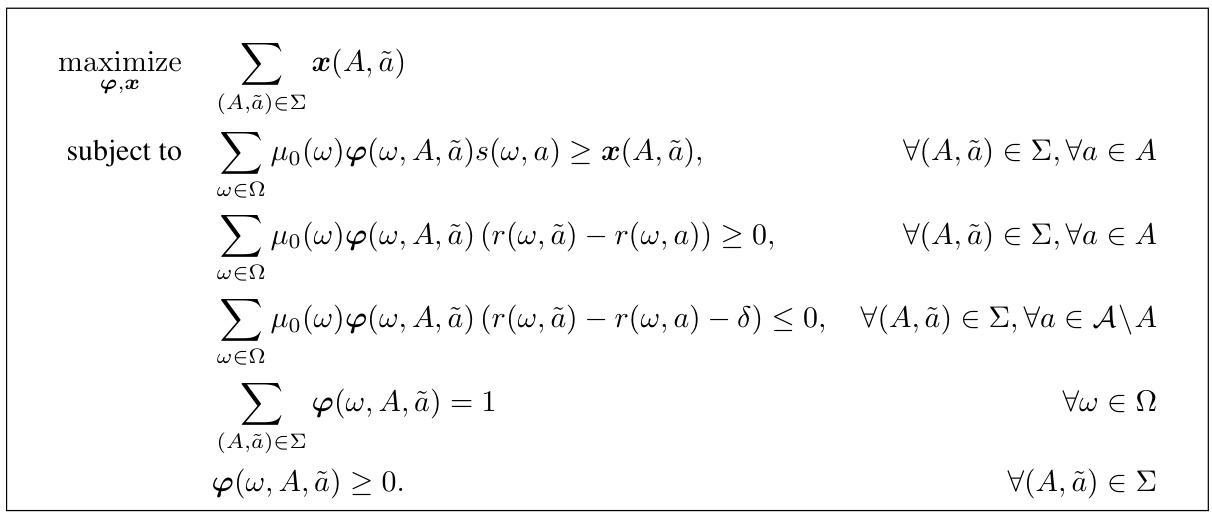

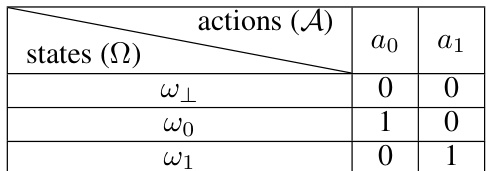

🔼 This table shows the utility values for both the sender and the receiver in a Bayesian persuasion game. The sender and receiver both receive a utility of 1 if the receiver’s action matches the true state (ω₀ or ω₁), and 0 otherwise. If the state is ω₁, then both players receive 0 utility, regardless of the action taken. This payoff structure is designed to analyze the efficacy of the proposed persuasion techniques under approximate best response conditions.

read the caption

Table 1: The utility function for both the sender and the receiver. If the state is w₁, then both players have 0 utility. Otherwise, both players get utility 1 if and only if the receiver's action matches the true state.

In-depth insights#

Approx. Best Response#

The concept of ‘Approximate Best Response’ in the context of Bayesian persuasion offers a crucial relaxation of the idealistic assumption that the receiver will always choose the action that precisely maximizes their expected utility. This real-world consideration acknowledges that agents might not be perfectly rational or might face computational limitations. By introducing a tolerance parameter (δ), the model permits the receiver to select any action within a certain threshold of optimality. This approach makes the model more robust and applicable to practical scenarios, where minor deviations from perfect rationality are expected. The computational implications of this relaxation are significant, altering the structure of the optimization problem and necessitating the development of new algorithms to handle the increased complexity. The effectiveness and efficiency of these algorithms become critical considerations in determining the overall practicality of incorporating approximate best responses into Bayesian persuasion models.

Algorithmic Challenges#

The heading ‘Algorithmic Challenges’ in a research paper would likely discuss computational hurdles in solving the problem. This could involve analyzing the complexity of finding optimal strategies, perhaps showing it’s NP-hard, therefore computationally intractable for large instances. The paper might then explore approximation algorithms or heuristics offering trade-offs between solution quality and computational cost. The discussion would ideally pinpoint bottlenecks, such as the exponential growth of the search space in Bayesian persuasion, and propose innovative algorithmic techniques to overcome these issues. This could include linear programming relaxations, dynamic programming approaches, or advanced combinatorial optimization methods. A strong section would quantify the efficiency of proposed algorithms, showing polynomial or quasi-polynomial time complexity, and comparing their performance against existing approaches. It might also address the robustness of the algorithms, assessing how well they perform under noise or uncertainty in the input data.

Small Space Efficiency#

The concept of ‘Small Space Efficiency’ in the context of a research paper likely refers to algorithmic optimizations designed to handle problems where either the state space or the action space is limited. The core idea is to leverage the inherent constraints of small spaces to achieve computational efficiency, avoiding brute-force approaches that become intractable as the dimensions grow. This could involve specialized data structures or algorithms that exploit the compact representation afforded by limited state and action options. A key aspect of this approach may involve the design of efficient search strategies. Rather than exploring the entirety of a potentially exponentially large solution space, algorithms focusing on small space efficiency might incorporate heuristics or pruning techniques to concentrate on a reduced set of promising solutions. The success of small space efficiency hinges on clever problem decomposition and the ability to bound the computational cost through analysis of the small space’s properties. Such analysis could reveal structural characteristics that permit the design of efficient algorithms with polynomial-time or even sub-polynomial-time complexity, where traditional approaches might incur an exponential cost. Therefore, the key challenge is to develop algorithms that exploit the limited size of the spaces in novel ways to achieve dramatic improvements in computational speed and resource usage.

Hardness Results#

The section on ‘Hardness Results’ would likely demonstrate the computational intractability of finding optimal solutions for the general Bayesian persuasion problem under approximate best response. This would be a crucial contribution, suggesting that efficient, exact algorithms are unlikely to exist unless P=NP. The authors would likely support this claim using a reduction from a known NP-hard problem, carefully constructing an instance of the Bayesian persuasion problem that mirrors the structure of the NP-hard problem. This reduction would likely be highly technical, mapping components of the original problem to elements of the persuasion problem (e.g. states, actions, utilities). The proof’s complexity would stem from demonstrating that a solution to the Bayesian persuasion problem provides a solution to the NP-hard problem, and vice versa. This establishes the equivalence in computational difficulty, thereby proving the claimed hardness. Successfully demonstrating this would be a significant contribution, highlighting the limitations of computationally efficient exact solutions for the robust Bayesian persuasion setting and motivating the need for approximation algorithms. The results would underscore the challenge of designing robust, principled algorithms for practical scenarios where the idealized assumptions of standard Bayesian persuasion often do not hold.

Robustness Limits#

The concept of ‘Robustness Limits’ in the context of a research paper likely explores the boundaries of an algorithm or model’s resilience to deviations from ideal conditions. This could involve investigating how well a Bayesian persuasion model performs when the receiver’s behavior deviates from perfectly rational best-response strategies. The analysis might reveal critical thresholds, beyond which the model’s predictive power or efficacy degrades significantly. Key factors influencing robustness limits would likely include the magnitude of receiver suboptimality (e.g., epsilon-best response), the uncertainty in the receiver’s prior beliefs, and imperfections in the signaling process. Understanding these limits is crucial for practical applications, highlighting the need for more robust and adaptable models that remain effective under real-world conditions. The research may quantify these limits, revealing the extent to which seemingly minor deviations can severely impact outcomes, thus informing the design of more resilient systems.

More visual insights#

More on tables

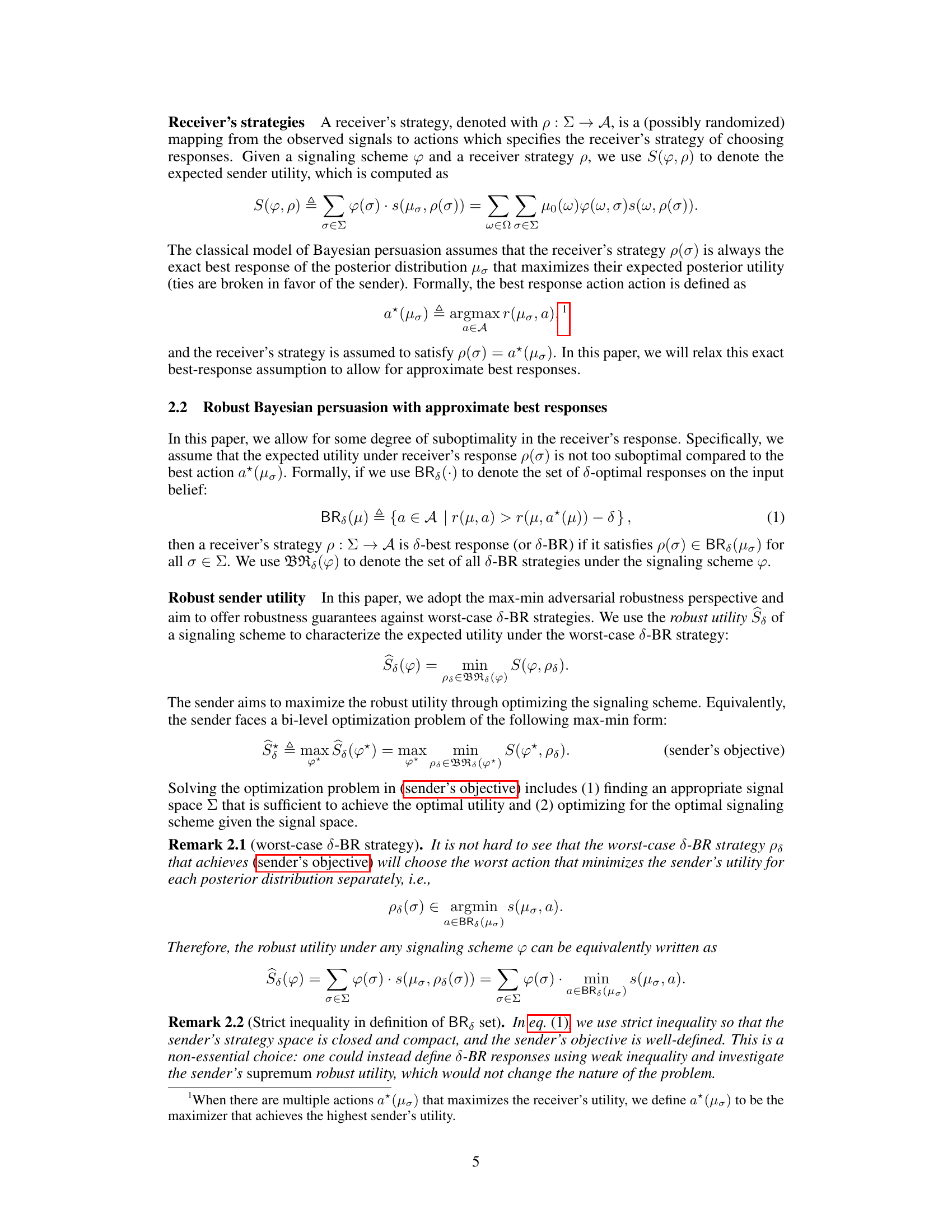

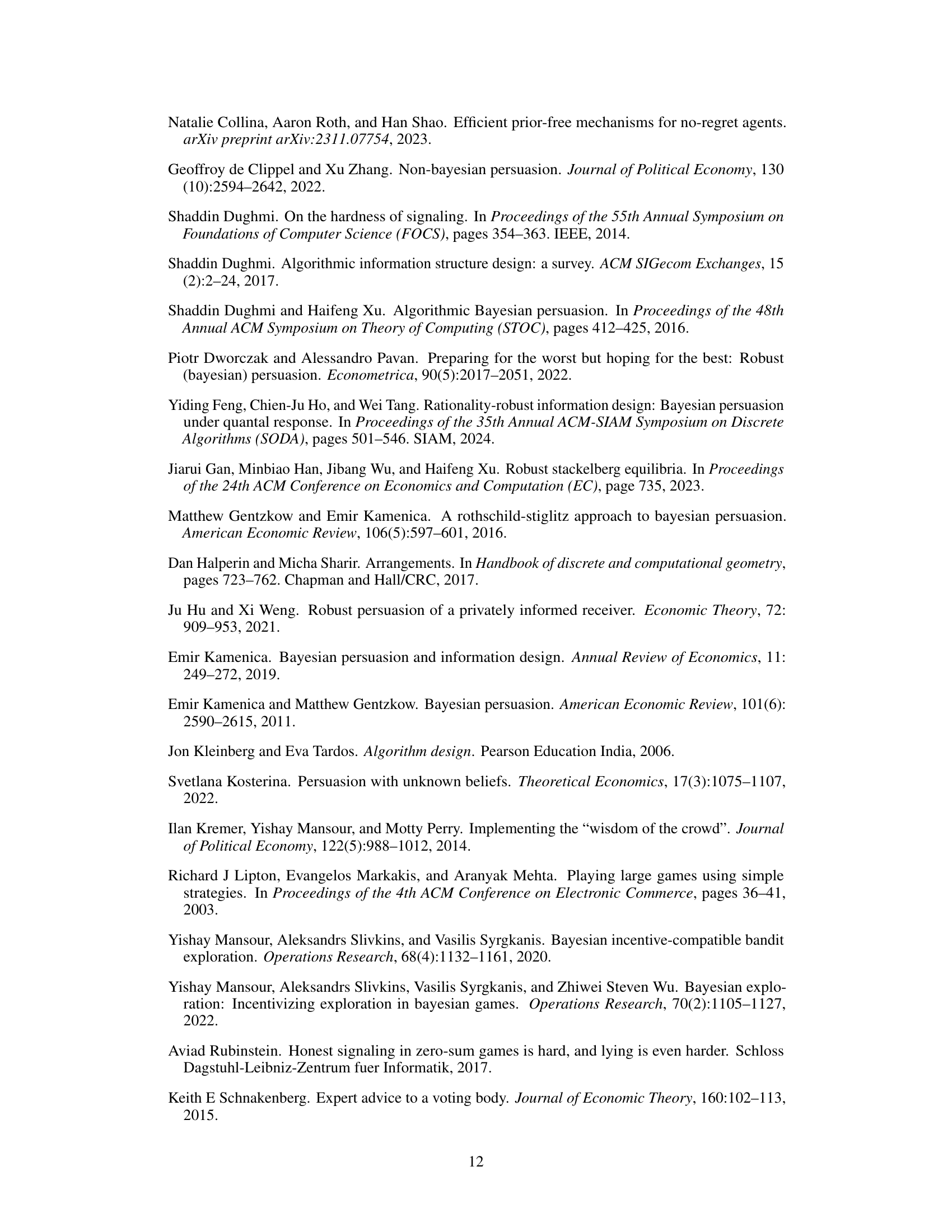

🔼 This table shows the utility values for both the sender and the receiver in a Bayesian persuasion game. The receiver’s utility is 1 if their action matches the state (w0, a0) or (w1, a1) and 0 otherwise. The sender’s utility mirrors this.

read the caption

Table 1: The utility function for both the sender and the receiver. If the state is w₁, then both players have 0 utility. Otherwise, both players get utility 1 if and only if the receiver's action matches the true state.

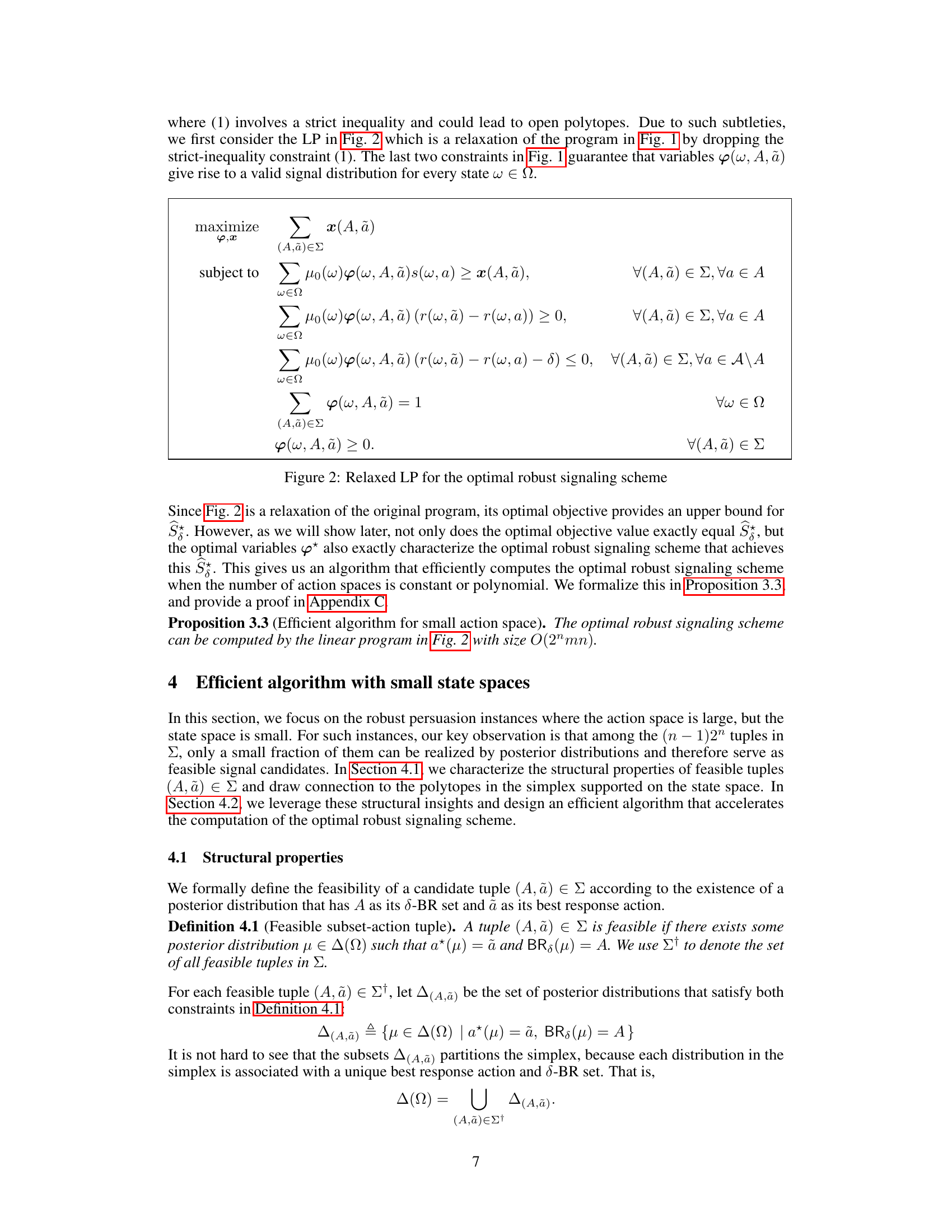

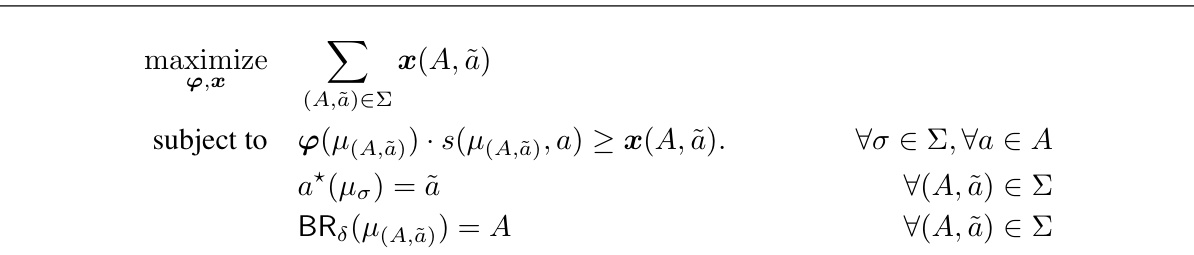

🔼 This table shows the utility values for both the sender and the receiver depending on the true state (ω₁, ω₀, ω₁) and the action taken (a₀, a₁). The receiver gets a utility of 1 only when their action matches the true state, otherwise 0. The sender’s utility mirrors this.

read the caption

Table 1: The utility function for both the sender and the receiver. If the state is ω₁, then both players have 0 utility. Otherwise, both players get utility 1 if and only if the receiver's action matches the true state.

Full paper#