TL;DR#

Many real-world objects are articulated, meaning they have multiple parts connected by joints allowing movement. Accurately modeling these objects in 3D is crucial for applications like robotics and animation, but existing methods often rely on expensive, manually annotated data. This makes creating large-scale datasets for training very difficult.

This paper introduces “Articulate Your NeRF,” a novel unsupervised method to overcome this limitation. It learns the geometry and movement of an articulated object’s parts using only two sets of images showing the object in different poses. This eliminates the need for manual annotations. By using an implicit neural representation and a clever training strategy, the method achieves state-of-the-art performance and requires fewer images, addressing a key challenge in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel unsupervised method for 3D articulated object modeling, a challenging problem with broad applications in robotics and computer vision. The method’s ability to learn from limited views and generalize to various object types offers significant advantages over existing techniques. It opens new avenues for research in unsupervised learning and 3D scene understanding, potentially leading to more efficient and robust methods for various applications.

Visual Insights#

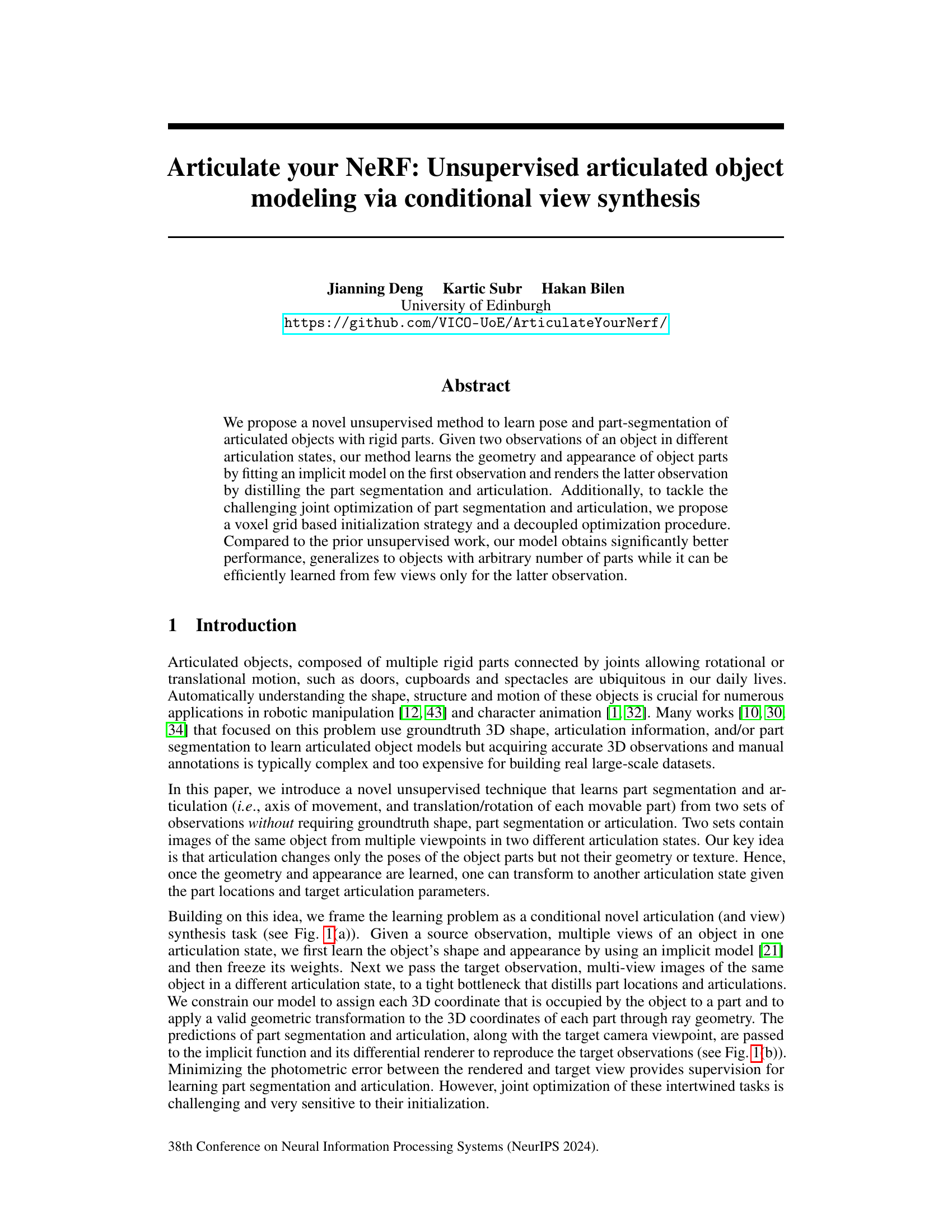

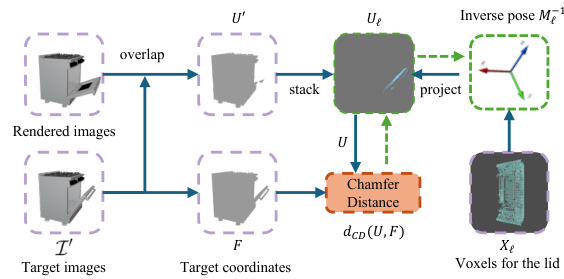

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main stages of the proposed method. (a) shows the pipeline overview. First, a NeRF is trained on images of the object in a single articulation state. Then, using images of the object in a different articulation state, the model learns the part segmentation and articulation parameters. (b) shows the details of the composite rendering process. The model uses the learned part geometry and appearance to render the target images by applying the predicted articulations to the segmented parts. The photometric error between the rendered and target images provides the supervision for learning.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) Our method learns the geometry and appearance of an articulated object by first fitting a NeRF from (source) images of an object in a fixed articulation. Then, from another set of (target) images of the object in another articulation, we distill the relative articulation and part labels. Green lines show the gradient path during this distillation. (b) Using the part geometry and appearance from NeRF, we render the target images by compositing the parts after applying the predicted articulations to the segmented parts. The photometric error provides the required supervision for learning the parts and their articulation without groundtruth labels.

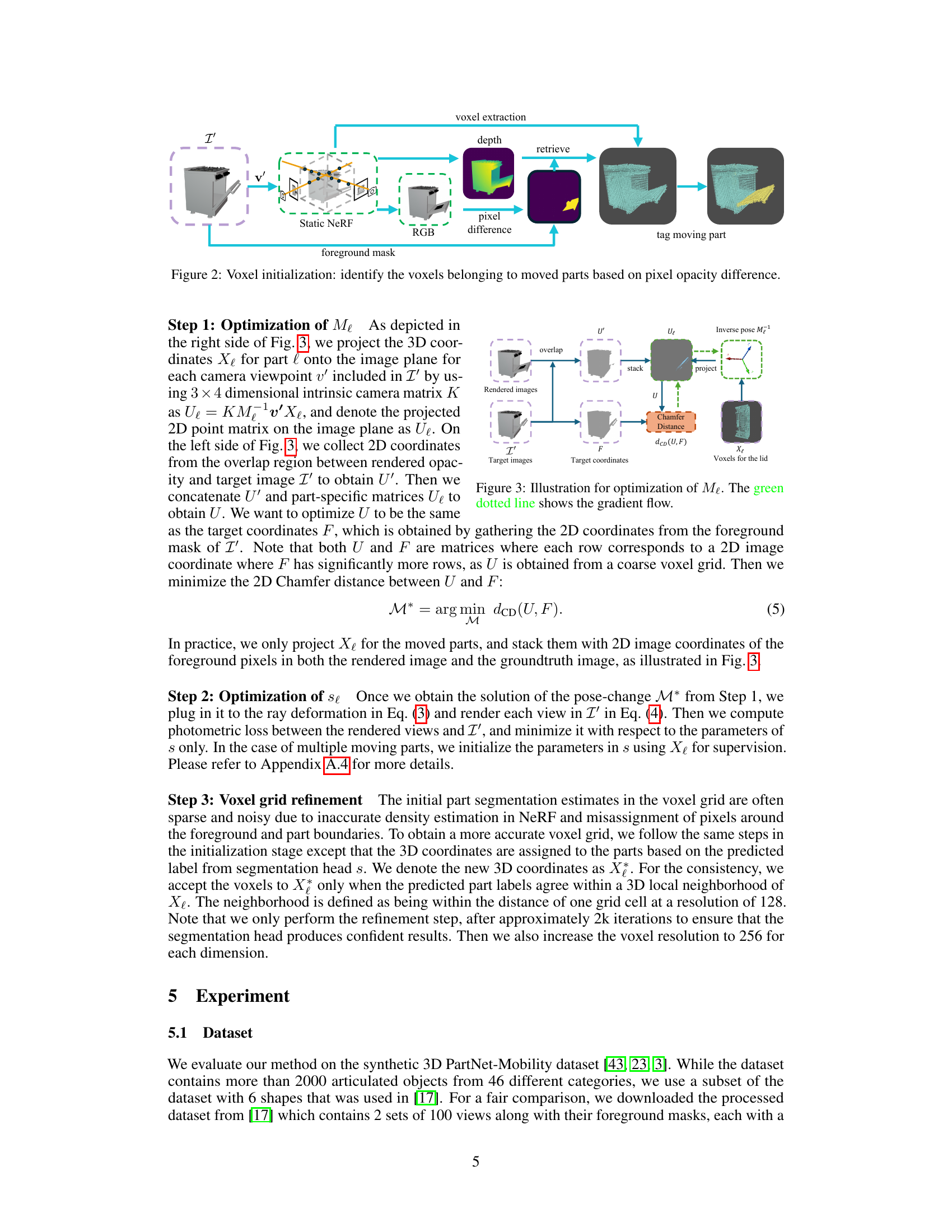

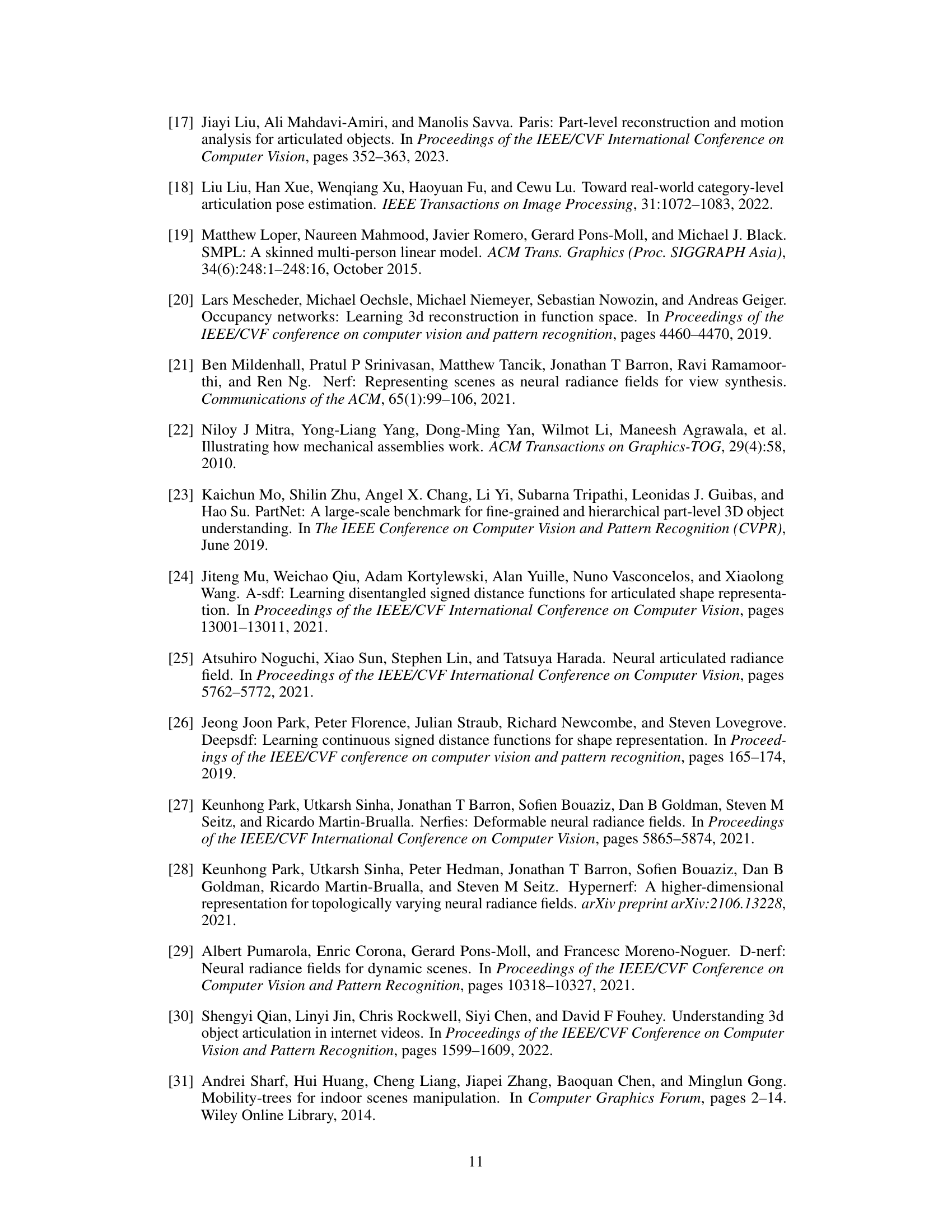

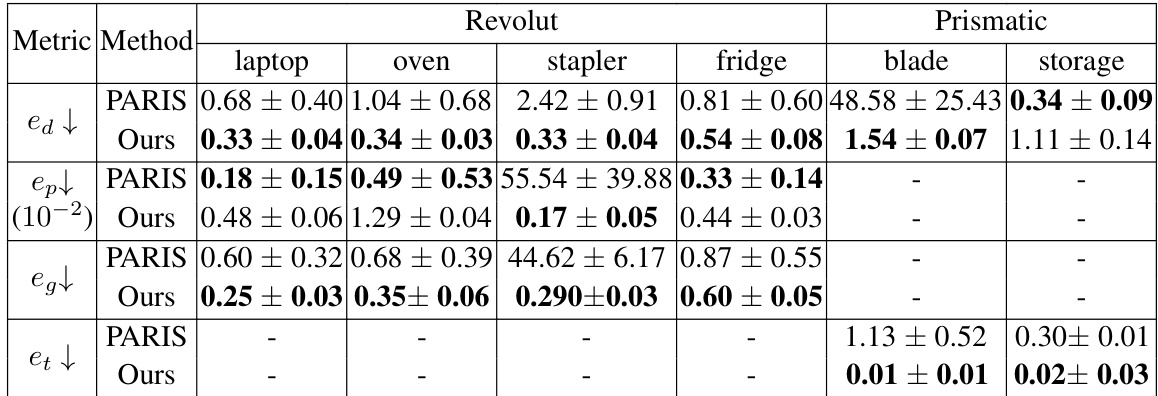

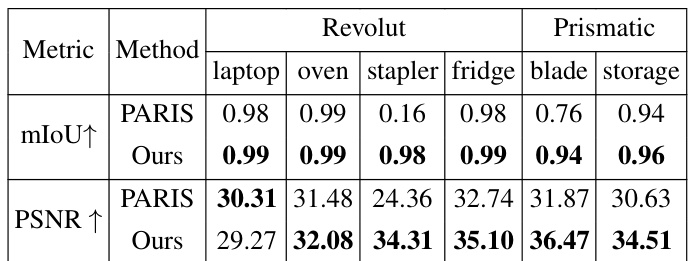

🔼 This table presents a comparison of part-level pose estimation results between the proposed method and the baseline method (PARIS). The metrics used are direction error (e_d), position error (e_pk), geodesic distance (e_g), and translation error (e_t). The results are shown for six different object categories: laptop, oven, stapler, fridge, blade, and storage. Lower values indicate better performance. The table highlights that the proposed method achieves superior accuracy with less variability across multiple runs compared to the PARIS method.

read the caption

Table 1: Part-level pose estimation results. Our method outperforms PARIS in majority of object categories while having lower variation over multiple runs in the performance.

In-depth insights#

NeRF Articulation#

NeRF articulation presents a novel challenge and opportunity in the field of 3D scene representation. By extending the capabilities of Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs), it aims to model and render articulated objects—objects with multiple parts that move relative to each other—in a more realistic and efficient manner. This involves addressing significant technical hurdles: accurately estimating the pose (position and orientation) of each part, effectively segmenting the object into its constituent parts, and seamlessly integrating these elements into a unified NeRF representation. Key innovations often involve disentangling the object’s geometry and appearance from its articulation parameters, potentially utilizing techniques such as conditional view synthesis or dynamic scene modeling to improve accuracy and reduce computational cost. Unsupervised methods are particularly important, as ground-truth articulation data can be expensive and difficult to obtain. The success of NeRF articulation hinges upon the ability to generalize across various object types and articulation patterns, ultimately leading to more robust and versatile 3D scene modeling.

Unsupervised Learning#

Unsupervised learning, in the context of articulated object modeling, presents a significant challenge and opportunity. The absence of labeled data forces the model to learn intricate relationships between object parts, their poses, and visual appearances solely from unlabeled image data. This necessitates innovative approaches to tackle the problem of joint optimization of part segmentation and articulation estimation. Effective initialization strategies, potentially leveraging auxiliary structures like voxel grids, become crucial for guiding the optimization process and preventing the algorithm from converging to suboptimal solutions. Further, the use of conditional view synthesis provides a valuable framework for unsupervised training, allowing the model to learn by rendering consistent views of the object across different articulation states. This approach leverages the inherent constraints of rigid part movement and visual consistency to implicitly guide the learning process. The success of unsupervised learning in this domain hinges on carefully designing an effective loss function and optimization strategy to handle the intertwined nature of the tasks. Successfully accomplishing this would greatly benefit various applications needing efficient object understanding from limited, unlabeled data. Finally, the performance of unsupervised methods should be rigorously assessed and compared to supervised alternatives, emphasizing generalization capabilities and robustness to variations in object shape and articulation.

Part Segmentation#

Part segmentation, within the context of articulated object modeling, presents a significant challenge. The paper tackles this by framing it as a conditional view synthesis task, leveraging the learned geometry and appearance of the object from a source view. A key idea is the distillation of part locations and articulations from a target view, which are then used to condition the rendering process. The method elegantly uses an implicit neural representation, enabling efficient part-level rendering and composition. A voxel-grid initialization strategy addresses the challenge of joint optimization, providing a crucial starting point for iterative refinement. The introduction of a decoupled optimization procedure further enhances stability and performance, separating the optimization of part segmentation from that of articulation parameters. Overall, this approach allows for unsupervised learning of both part segmentation and articulation, with notable performance improvements compared to prior unsupervised methods.

View Synthesis#

View synthesis, in the context of this research paper, is a crucial technique for creating novel views of an articulated object from limited input. The core idea is learning a model that can predict the appearance of the object from unseen viewpoints, based on a small number of initial observations. This is achieved by disentangling the object’s geometry and appearance from the articulation parameters. The learned model efficiently generates realistic novel views by intelligently combining the predicted part segmentation and articulation with the object’s inherent shape and texture. A key challenge lies in accurately predicting both segmentation and pose, which are intertwined and difficult to optimize jointly. This necessitates innovative solutions such as a voxel grid initialization and a decoupled optimization procedure. Ultimately, the success of this method hinges on the effective learning of an implicit function representing the object, allowing the generation of high-quality synthetic views conditioned on target viewpoints and articulation parameters. Unsupervised learning, which requires no ground truth labels for articulation and part segmentation, is a significant contribution, enabling scalability and applicability. The work showcases the capabilities of this method in handling objects with various numbers of parts and different articulation types.

Multi-Part Modeling#

Multi-part modeling presents a significant challenge in computer vision and graphics, demanding robust techniques to handle the complexities of objects composed of multiple interacting parts. Accurate part segmentation is crucial, requiring methods that can reliably distinguish individual parts despite variations in viewpoint, articulation, and appearance. This necessitates sophisticated algorithms that can capture part geometry and relationships accurately. Efficient representation is also vital, balancing detail with computational tractability. Implicit representations like neural radiance fields (NeRFs) offer flexibility but require careful design to manage the increased complexity. Effective training strategies are essential, as jointly optimizing part segmentation and articulation parameters can be computationally expensive and prone to instability. Therefore, techniques such as decoupled optimization are useful for handling the intertwined challenges. Generalization to diverse object categories and articulation types is a key goal. Ultimately, successful multi-part modeling hinges on the capacity to learn robust and efficient representations while addressing the inherent difficulties of segmentation, parameter estimation, and robust generalization.

More visual insights#

More on figures

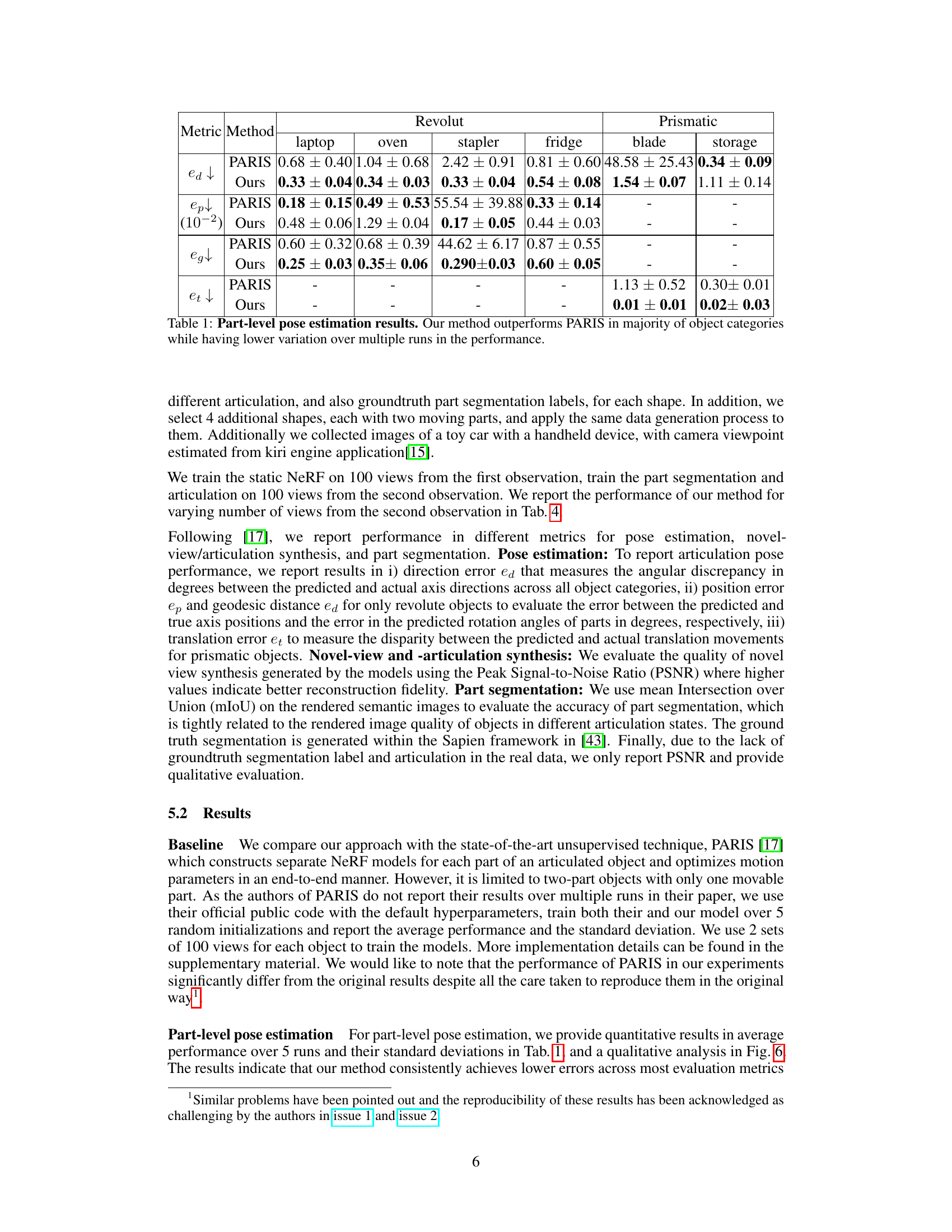

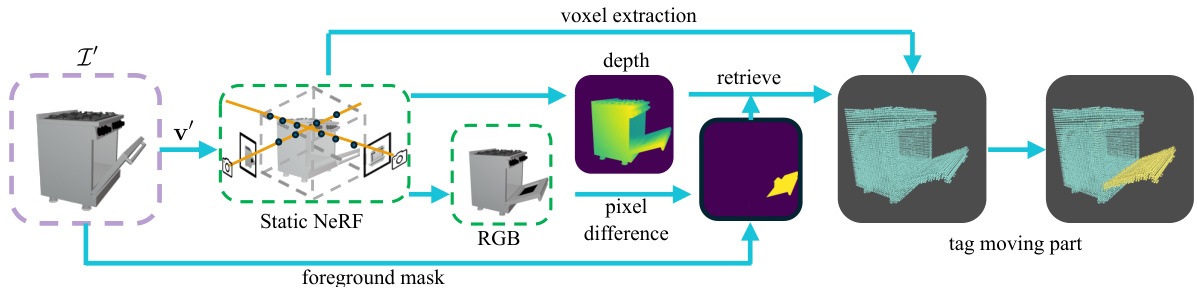

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of initializing a voxel grid to identify the parts of an object that move between two different articulation states. First, the static NeRF renders a view of the object in the second articulation state. The difference between this rendered view and the actual second-state image (target view) highlights the areas of change. These areas are then used to identify voxels corresponding to the moving parts in the 3D space of the object’s NeRF representation. This provides an initial estimate for optimizing the positions of the moving parts during subsequent steps of the articulated object modeling process. The voxel grid’s coordinates are then passed to a process that refines the part segmentation and articulations in later steps.

read the caption

Figure 2: Voxel initialization: identify the voxels belonging to moved parts based on pixel opacity difference.

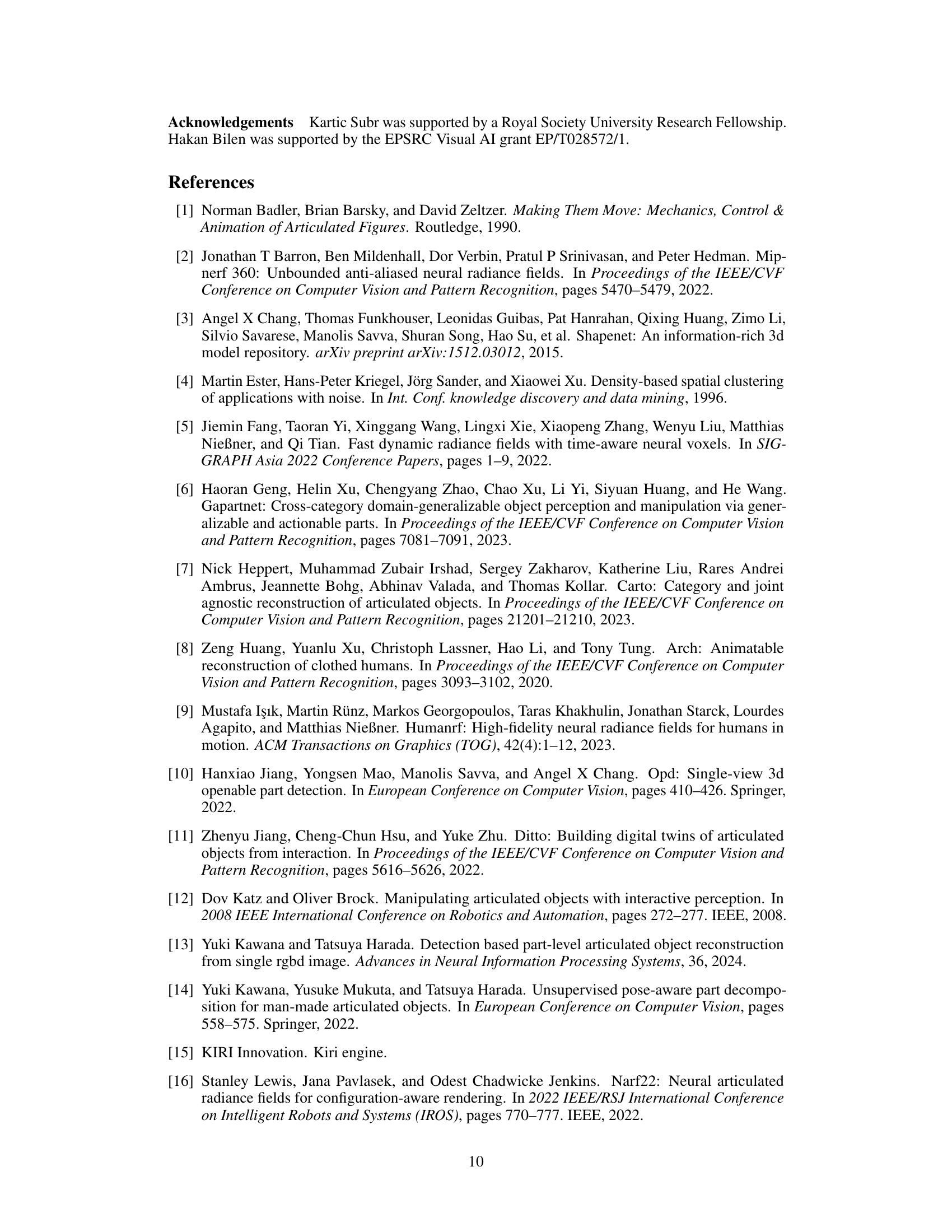

🔼 This figure illustrates the optimization process for the pose-change tensor M. The left side shows the collection of 2D coordinates (U’) from the overlap region between rendered opacity and the target image I’. These are concatenated with the part-specific matrices U_e, resulting in the matrix U. The right side shows the projection of 3D coordinates X_e for part l onto the image plane to get U_e. The goal is to minimize the Chamfer distance between U and the target coordinates F (obtained from I’s foreground mask). The green dotted lines indicate the gradient flow during this optimization.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration for optimization of M. The green dotted line shows the gradient flow.

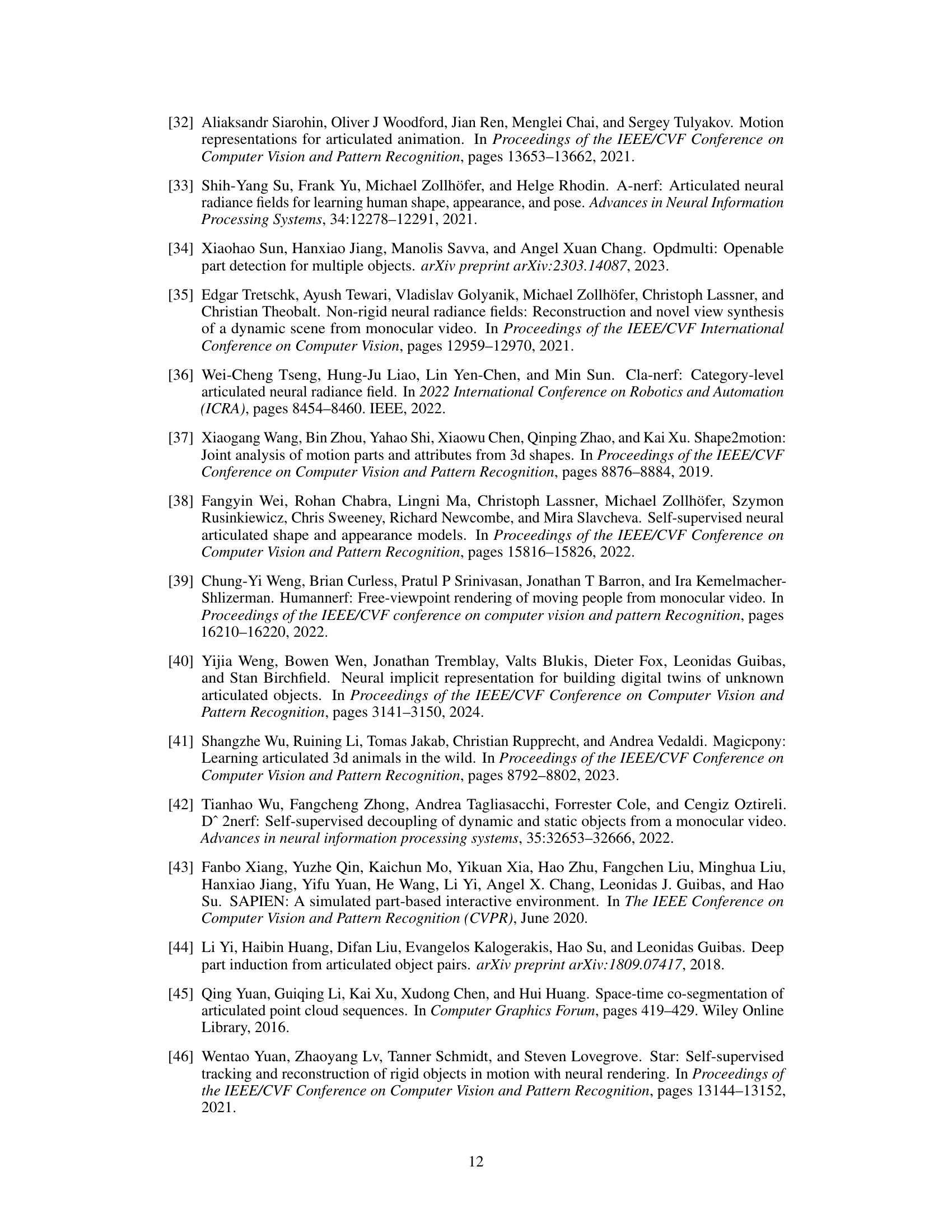

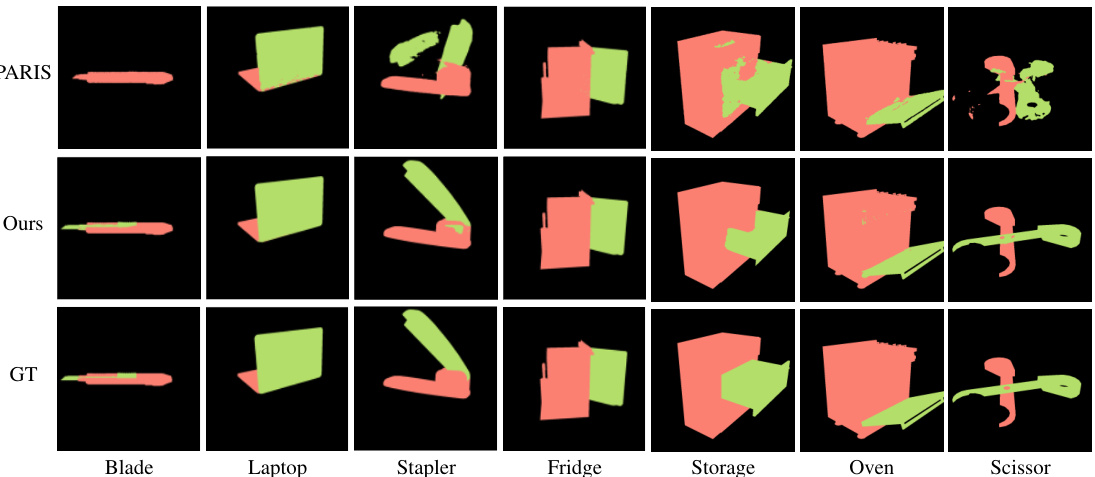

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of 2D part segmentation results between the proposed method and the baseline method (PARIS) on seven different articulated objects. Each object is shown in two articulation states. The green pixels denote movable parts. The results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves consistent performance across various object categories while the PARIS method fails to accurately segment parts for some objects such as the Blade, Laptop, and Scissor.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative 2D part segmentation results. Pixels in green denotes the movable parts. Our method demonstrates consistent performance across all tested objects while PARIS failed for Blade, Laptop and Scissor.

🔼 This figure displays the qualitative results of 2D multi-part segmentation. The ground truth (GT) segmentations are compared to the segmentations produced by the proposed method. Four objects are shown: Box, Glasses, Oven, and Storage. Each object has multiple parts, some static (pink) and some moving (various other colors). The figure visually demonstrates the accuracy of the model’s ability to segment different parts of articulated objects in 2D.

read the caption

Figure 5: Qualitative results for 2D multi-part segmentation. The pink color denotes the static part, while other colors denote the moving parts.

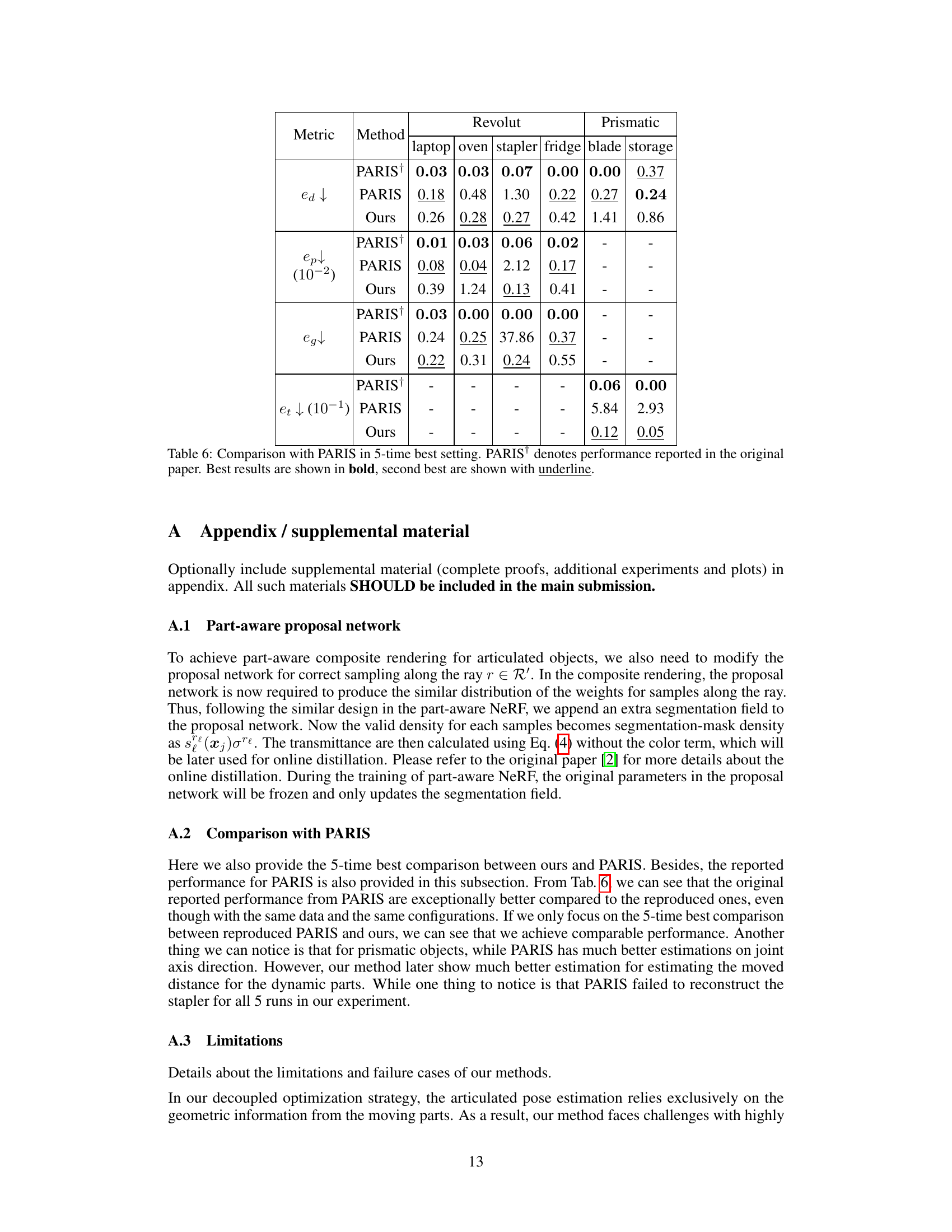

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of novel articulation synthesis results between the proposed method and the baseline method (PARIS). For several objects (blade, stapler, and box), multiple views are displayed, showing the ground truth articulation axis (green) and the predicted articulation axis (red) generated by each method. The results visually demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method in accurately predicting the articulation of objects with various shapes and moving parts. The supplementary materials contain additional visualizations for a more comprehensive evaluation.

read the caption

Figure 6: Qualitative evaluation for novel articulation synthesis. The ground truth axis is denoted in green and the predicted axis is denoted in red. Please refer to the supplementary for more visualizations.

🔼 This figure shows the results of applying the ArticulateYourNeRF method to real-world examples. Specifically, it showcases the model’s ability to estimate the joint axis direction (shown in red) for a toy car with an openable door. The ground truth is shown in green and purple for the door and pink for the car body. Additional qualitative evaluations can be found in Figure 12.

read the caption

Figure 7: Results on real world examples, the red line indicates the estimated joint axis direction. Green and purple color denotes the moving car door, while pink denotes the body of the toy car. Please refer to Fig. 12 for more qualitative evaluation.

🔼 This figure illustrates the voxel grid initialization process. It shows how the system identifies voxels corresponding to moving parts by comparing rendered opacity (from the static NeRF) with the foreground masks from target images. Pixels that appear in the rendered opacity but not in the target foreground mask are identified as part of the moving parts, and their corresponding 3D coordinates are used to initialize the voxel grid. This grid serves as an initial estimate for the locations of moving parts, helping guide the subsequent optimization process.

read the caption

Figure 2: Voxel initialization: identify the voxels belonging to moved parts based on pixel opacity difference.

🔼 This figure shows three images of a folding chair. The leftmost image is the ground truth RGB image. The middle image is the rendered RGB image from the model, showing artifacts and inaccuracies in the rendering. The rightmost image shows the part segmentation produced by the model. The part segmentation highlights areas where the model struggled to accurately separate the parts of the chair, particularly the seat and legs. This serves as an example of a failure case for the method in handling more complex objects.

read the caption

Figure 8: Failure cases for foldchair, from left to right: groundtruth RGB, rendered RGB, part segmentation.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison between the ground truth image and the rendered image of a pair of glasses with thin arms. The ground truth image on the left shows the glasses clearly. The rendered image on the right shows artifacts, particularly around the thin arms of the glasses, indicating challenges in accurately rendering fine details with the proposed method.

read the caption

Figure 8: (c) Artifacts for thin parts, the left one is the groundtruth, the right rendering result.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison between the ground truth image, the rendered image from the model, and the part segmentation. It highlights a limitation of the model where the corner of the laptop screen is missing in the novel articulation rendering, despite the segmentation appearing accurate in the original pose. This suggests a potential issue with the proposal network’s ability to estimate density distributions accurately from specific viewpoints.

read the caption

Figure 9: We can see in the Fig. 9(b) that the corner of the laptop screen is missing in the novel articulation rendering. While it looks perfect when we check the segmentation in the original pose. Thus, we suspect it is the proposal network than failed to estimate the density distribution for the screen from certain viewpoints.

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of novel articulation synthesis between the proposed method and the baseline method (PARIS). For multiple objects with different articulation types, the ground truth and predicted axes of movement are visualized. The green arrows represent the ground truth, and the red arrows show the predicted axes of movement. The figure demonstrates the superior accuracy and robustness of the proposed method in estimating the articulation parameters for different object categories. More detailed visualizations and quantitative results are available in the supplementary materials.

read the caption

Figure 6: Qualitative evaluation for novel articulation synthesis. The ground truth axis is denoted in green and the predicted axis is denoted in red. Please refer to the supplementary for more visualizations.

🔼 This figure displays qualitative results for novel articulation synthesis. It shows several objects in different articulation states (poses). For each object, there are ground truth poses, the predicted poses from the model, and images generated from the model. The green arrows indicate the ground truth axis of rotation, while red arrows represent the predicted axis. The results demonstrate the model’s ability to accurately predict the pose changes of an object’s parts, leading to realistic novel view synthesis. More visualizations can be found in the supplementary material.

read the caption

Figure 6: Qualitative evaluation for novel articulation synthesis. The ground truth axis is denoted in green and the predicted axis is denoted in red. Please refer to the supplementary for more visualizations.

🔼 This figure shows qualitative results of applying the proposed method to real-world objects. The top row displays novel articulation synthesis for a toy car with its door open and closed. The red lines indicate the predicted joint axis. The bottom row shows the corresponding part segmentation results. The colors represent different parts of the car. This demonstrates the method’s ability to handle real-world scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 7: Results on real world examples, the red line indicates the estimated joint axis direction. Green and purple color denotes the moving car door, while pink denotes the body of the toy car. Please refer to Fig. 12 for more qualitative evaluation.

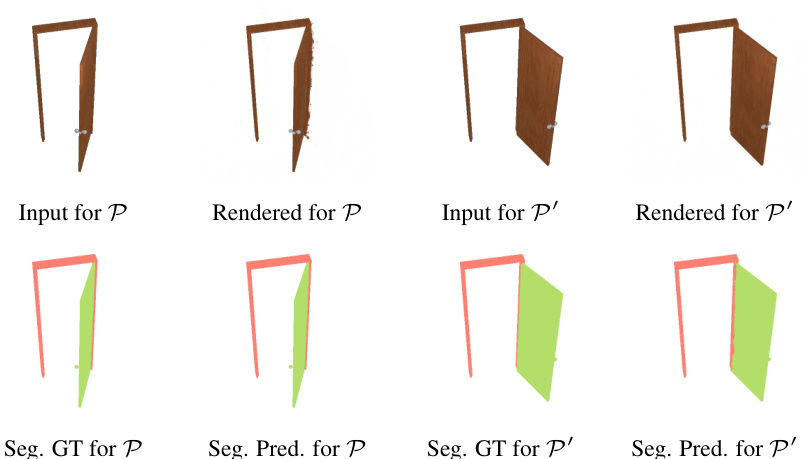

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the proposed method’s performance on a door object. The top row displays the input images and the rendered images for the door in two different articulation states (P and P’). The bottom row shows the ground truth and predicted part segmentations for each state. This visualization demonstrates the model’s ability to accurately render the door’s appearance and segment its parts in different poses.

read the caption

Figure 13: Here we show qualitative results for a ‘door’ instance along with its frame. In contrast to the instances in our submission, the static part (frame) is smaller than the moving part (door). Given two sets of views in the articulation P and P’, we provide the original input images and their rendering in the respective articulations, ground-truth (GT) and predicted part segmentation results. Our method achieves faithful rendering results in different articulations with minor artifacts and accurate part segmentation.

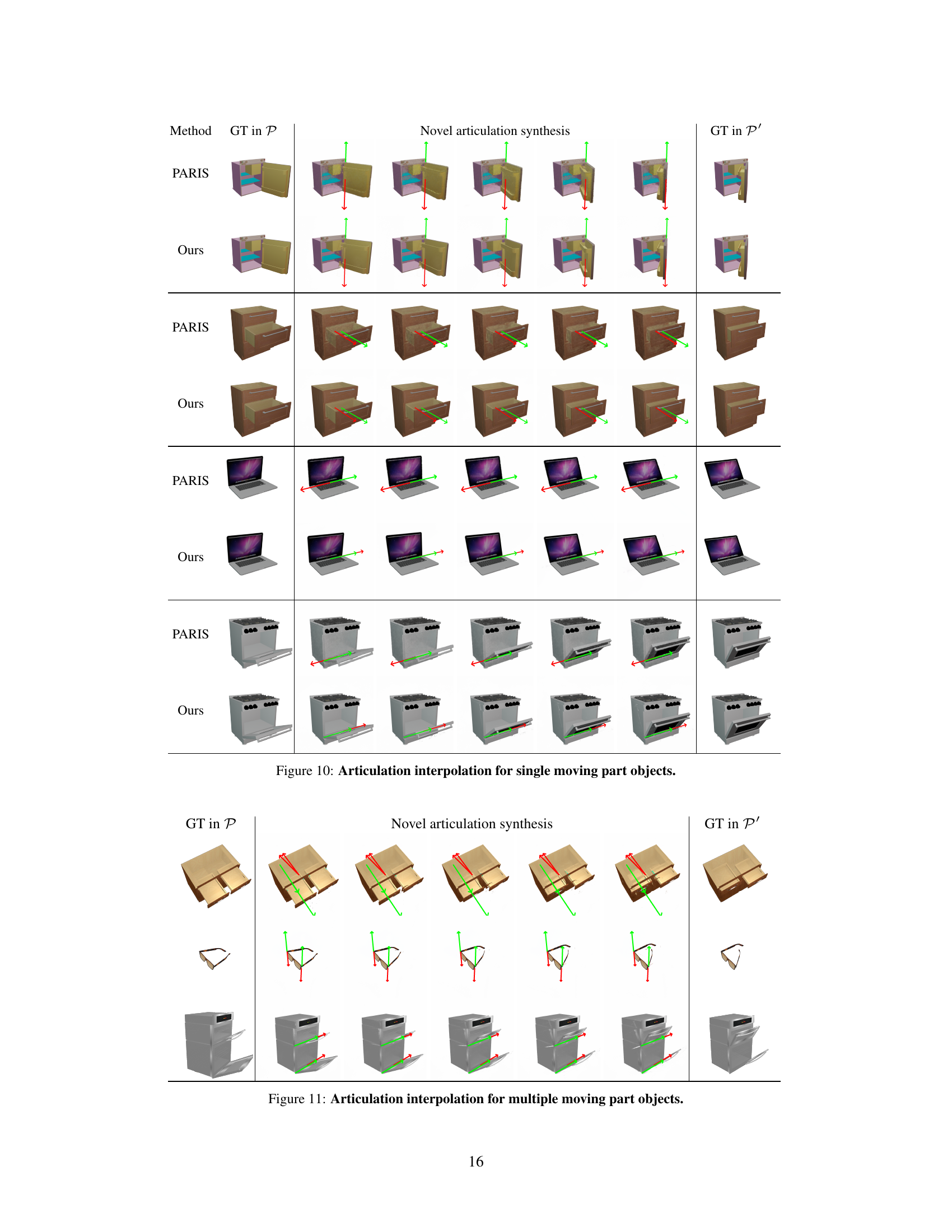

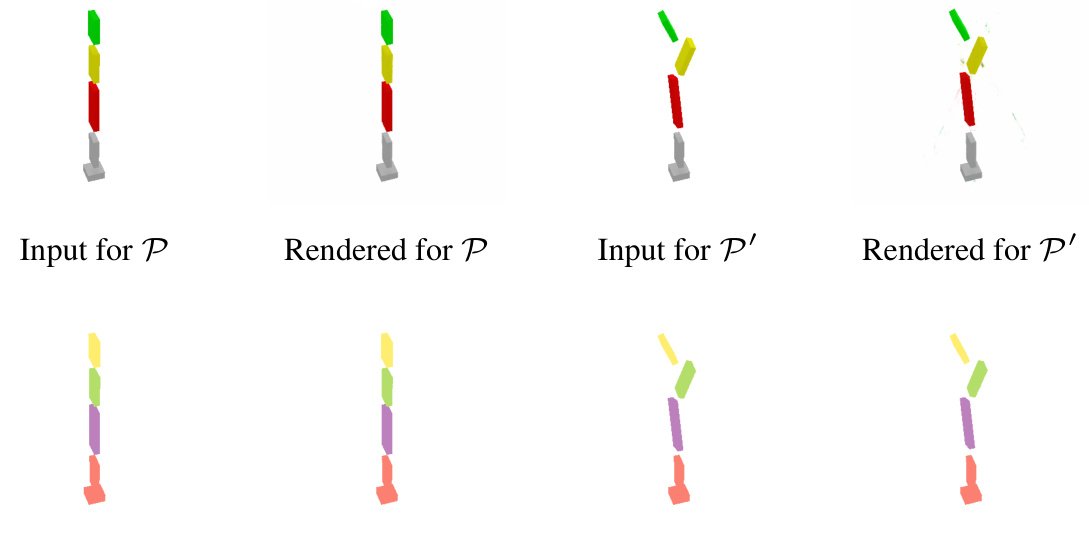

🔼 This figure shows qualitative results for novel articulation synthesis on objects with multiple moving parts. The top row displays a robotic arm with multiple joints. The bottom row shows a different object with multiple moving parts. For each object, the ground truth (GT) poses in articulations P and P’ are shown alongside the rendered images produced by the method in articulations P and P’. Part segmentation results are also displayed for both articulations.

read the caption

Figure 11: Articulation interpolation for multiple moving part objects.

More on tables

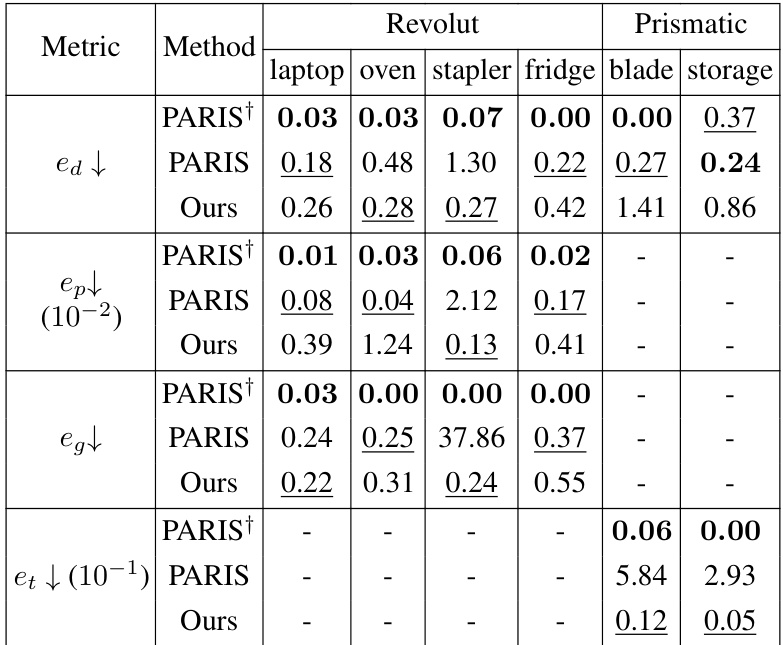

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against the baseline method (PARIS) in terms of articulation synthesis and part segmentation performance. The metrics used for evaluation are Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), which measures the quality of the synthesized images, and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), which measures the accuracy of the part segmentation. The results are averaged over 5 independent runs of each method, and the best results are highlighted in bold. The table provides a detailed breakdown of the results for both revolute and prismatic object categories.

read the caption

Table 2: Articulation synthesis and part segmentation results. Average performance over 5 runs (best results in boldface).

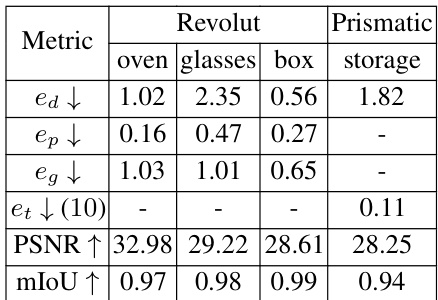

🔼 This table presents the results of the experiment on objects with multiple movable parts. It shows the performance of the proposed method in terms of several metrics: direction error (ed), position error (ep), geodesic distance (eg), translation error (et), Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU). The metrics are calculated for each object category separately, providing a comprehensive evaluation of part-level pose estimation accuracy.

read the caption

Table 3: Objects with multiple parts. Errors using multiple metrics for pose estimation (averaged over all joints).

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results by varying the number of target images used for training the model. The metrics evaluated are direction error (ed), position error (eg), and Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR). The results show that the model’s performance improves significantly with an increasing number of target images, indicating that sufficient data is essential for effective learning.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation studies with different number of target images.

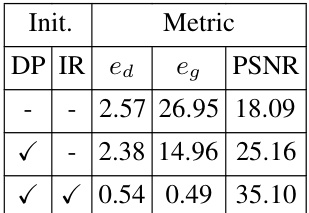

🔼 This table presents the ablation study of the proposed method on the performance of pose estimation and novel view synthesis. The ablation is performed by varying two components: decoupled pose estimation (DP) and iterative refinement of voxel grid (IR). The results show that both DP and IR significantly improve the performance, indicating their importance in the proposed framework. The metrics used are direction error (ed), geodesic distance (eg), and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR).

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study over different initialization strategies.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of part-level pose estimation results between the proposed method and the PARIS method. The metrics used are direction error (ea), position error (ep), geodesic distance (ed), and translation error (et). Results are shown for six object categories (laptop, oven, stapler, fridge, blade, and storage). The table highlights that the proposed method achieves lower errors and less variation across multiple runs compared to PARIS, particularly for certain object categories.

read the caption

Table 1: Part-level pose estimation results. Our method outperforms PARIS in majority of object categories while having lower variation over multiple runs in the performance.

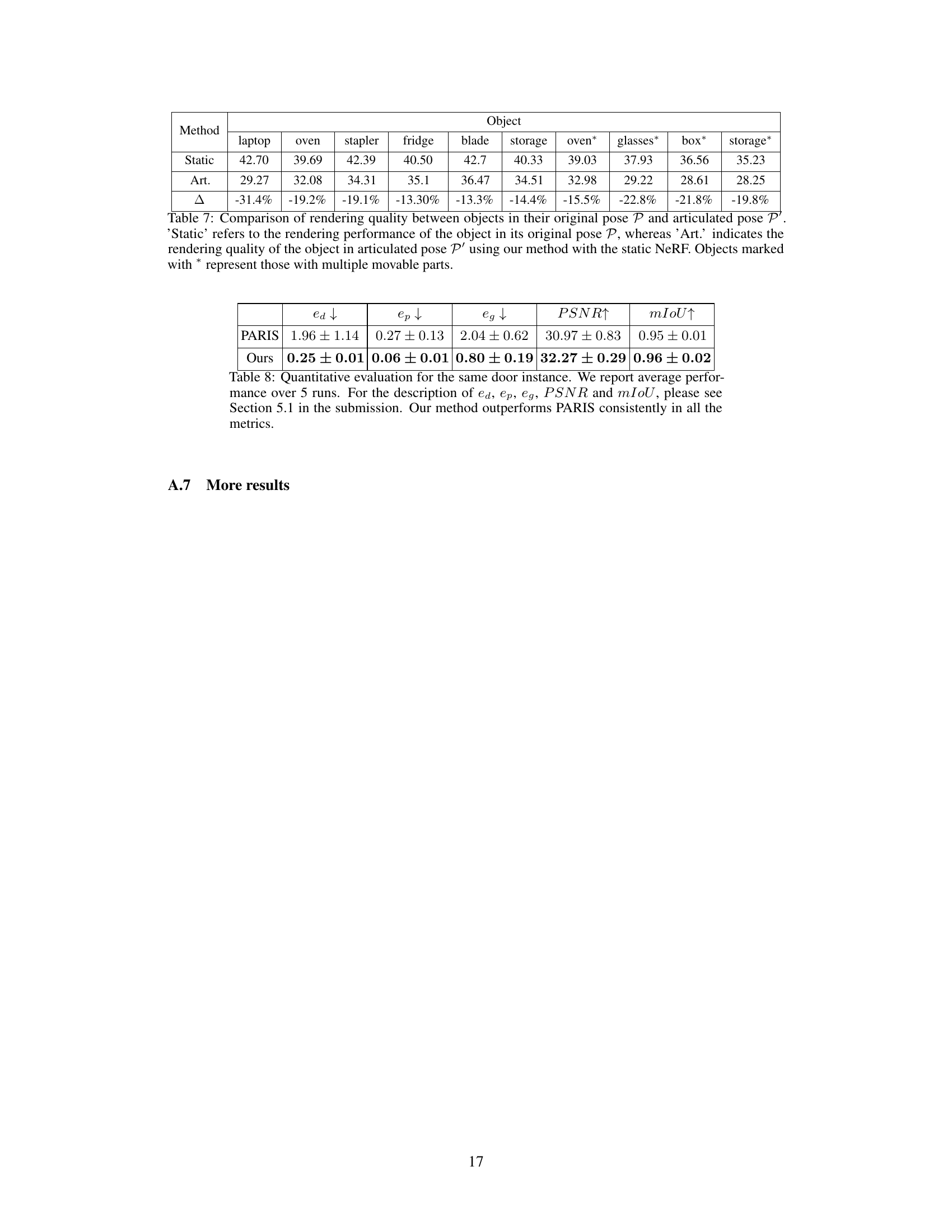

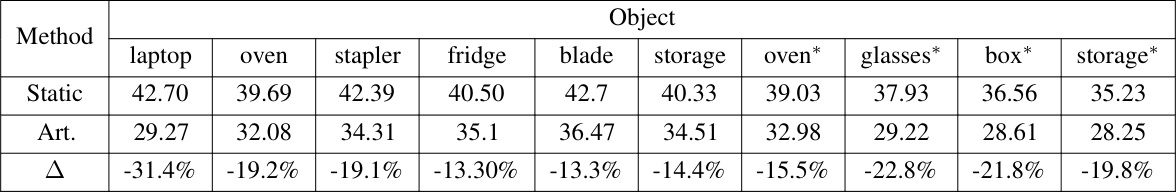

🔼 This table compares the rendering quality (PSNR) of objects in their original pose (Static) versus their articulated pose (Art.) using the proposed method. The difference (Δ) is calculated to show the performance drop in the articulated pose compared to the original pose. Objects with multiple moving parts are marked with an asterisk (*). The results highlight the impact of articulation on rendering quality, indicating that the method maintains good quality even with articulated poses.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison of rendering quality between objects in their original pose P and articulated pose P'. 'Static' refers to the rendering performance of the object in its original pose P, whereas 'Art.' indicates the rendering quality of the object in articulated pose P' using our method with the static NeRF. Objects marked with * represent those with multiple movable parts.

🔼 This table quantitatively evaluates the performance of the proposed method and the baseline method (PARIS) on a door instance. The metrics used include direction error (ed), position error (ep), geodesic distance (eg), Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU). The results show that the proposed method outperforms PARIS consistently across all metrics, indicating its superior performance in pose estimation, novel view synthesis, and part segmentation.

read the caption

Table 8: Quantitative evaluation for the same door instance. We report average performance over 5 runs. For the description of ed, ep, eg, PSNR and mIoU, please see Section 5.1 in the submission. Our method outperforms PARIS consistently in all the metrics.

Full paper#