TL;DR#

Goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (GCRL) faces challenges in efficiently exploring unfamiliar environments. Existing methods often struggle to reach goals at the frontier of explored areas, hindering effective exploration. Rare or hard-to-reach goals at the frontier are often overlooked, limiting exploration and slowing down the training process.

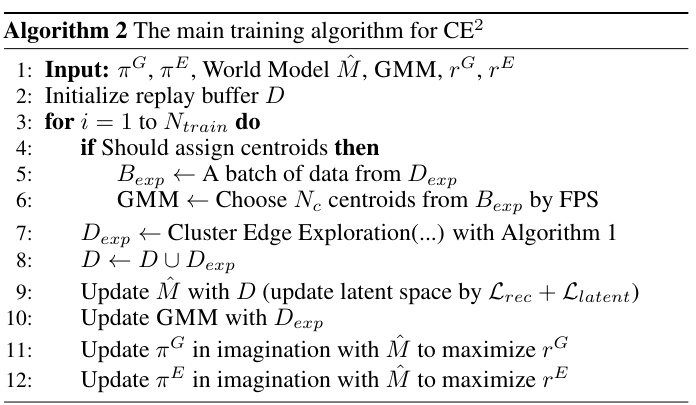

The paper introduces ‘Cluster Edge Exploration’ (CE2), a novel algorithm that addresses this issue. CE2 clusters easily reachable states in a latent space and prioritizes goals located at the boundaries of these clusters. This ensures that chosen goals are within the agent’s reach, promoting more effective exploration. Experiments in robotics environments (maze navigation, object manipulation) demonstrate CE2’s superiority over existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to exploration in goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (GCRL), a crucial aspect of many AI systems. The proposed method, CE2, addresses the challenge of efficiently exploring unknown environments by prioritizing accessible goal states at the edges of latent state clusters. This work has the potential to significantly improve the efficiency and effectiveness of GCRL algorithms, leading to faster training and better performance in various applications.

Visual Insights#

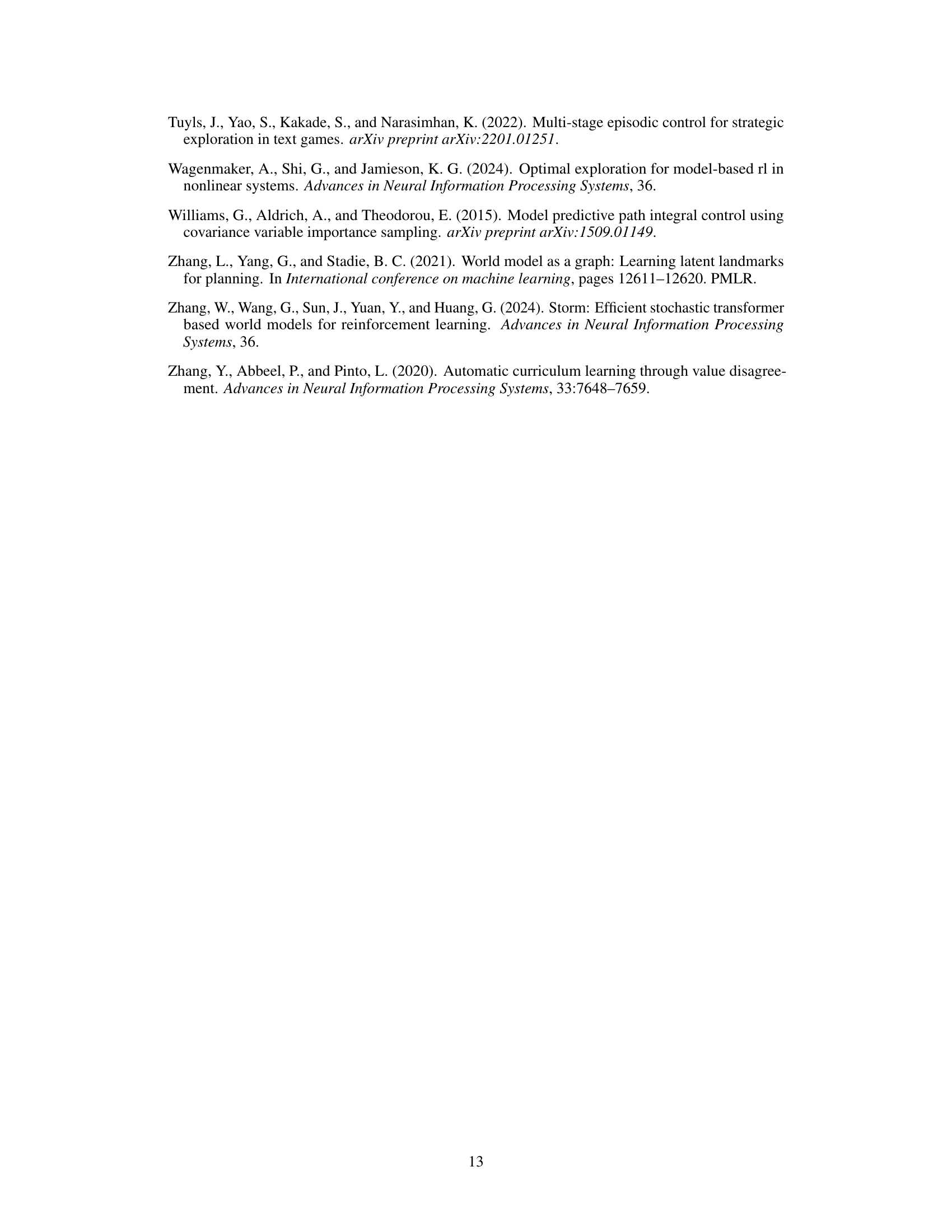

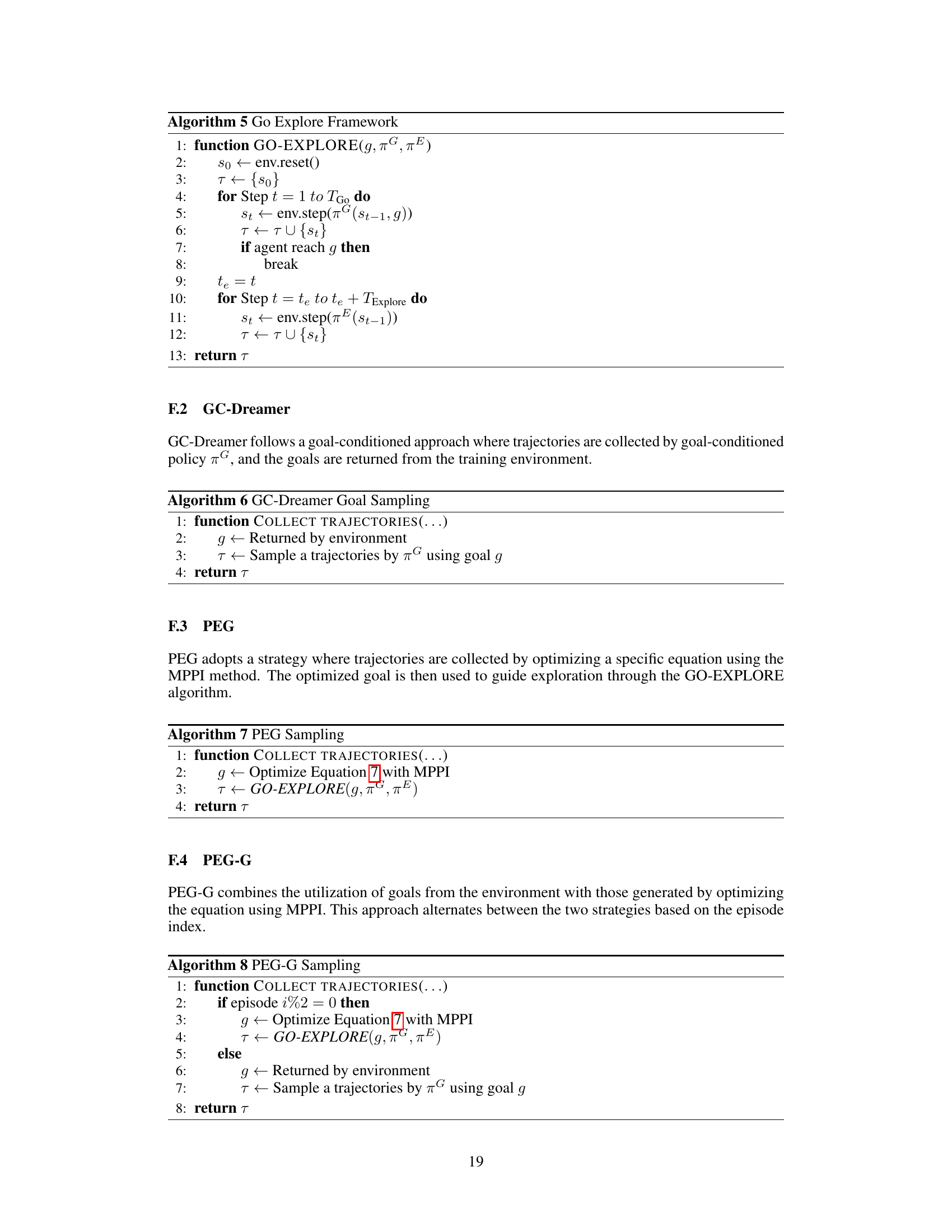

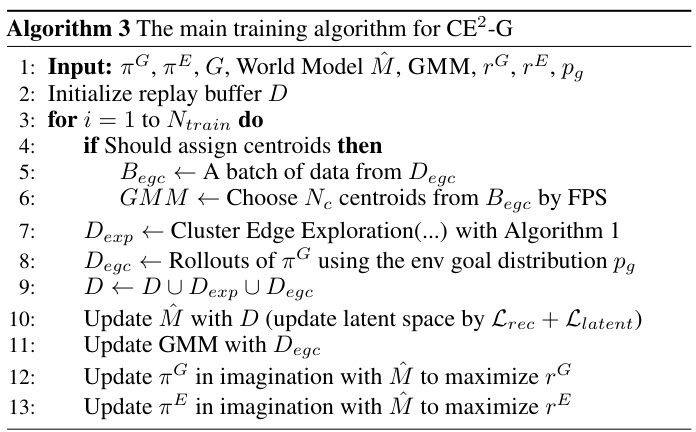

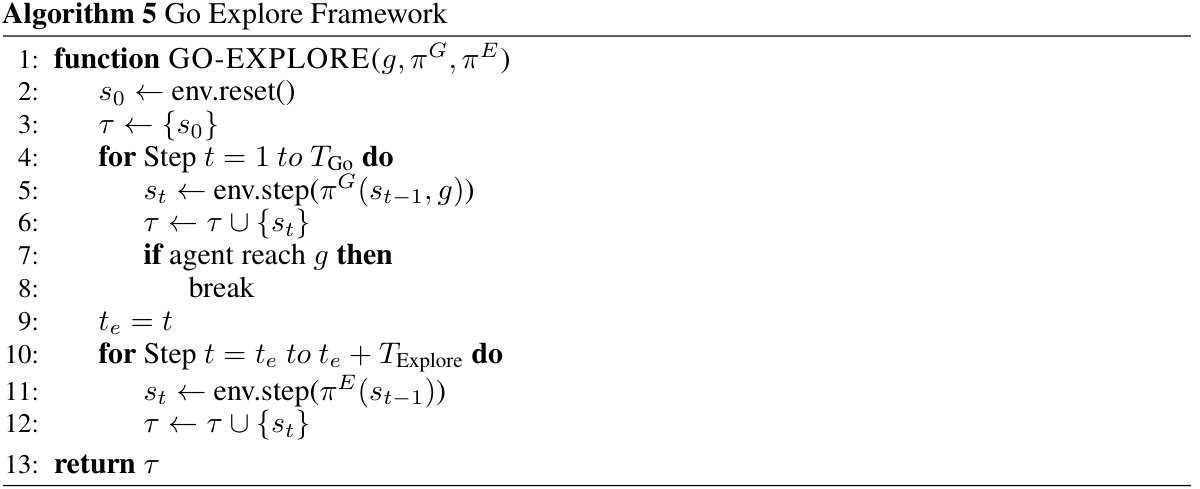

🔼 This figure illustrates the framework of Model-based Goal-Conditioned Reinforcement Learning (GCRL). It shows how a world model learns the environment’s dynamics from real-world interactions. The learned world model is then used to train both a goal-conditioned policy (πG(a|s,g)) for reaching specific goals and an exploration policy (πE(a|st)) for discovering new areas of the state space. The trajectories collected are stored in a replay buffer and used to further improve the world model and policies. This iterative process allows the agent to effectively explore the environment and learn to achieve diverse tasks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Model-based GCRL Framework

🔼 This table shows the runtime statistics for each experiment conducted in the paper. The metrics reported include total runtime in hours, total number of steps, episode length, and seconds per episode. The experiments covered include 3-Block Stacking, Walker, Ant Maze, Point Maze, Block Rotation, and Pen Rotation. These results provide insights into the computational cost of each task and can be used to compare the efficiency of the proposed method (CE2) with other methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

In-depth insights#

Cluster Edge Exploration#

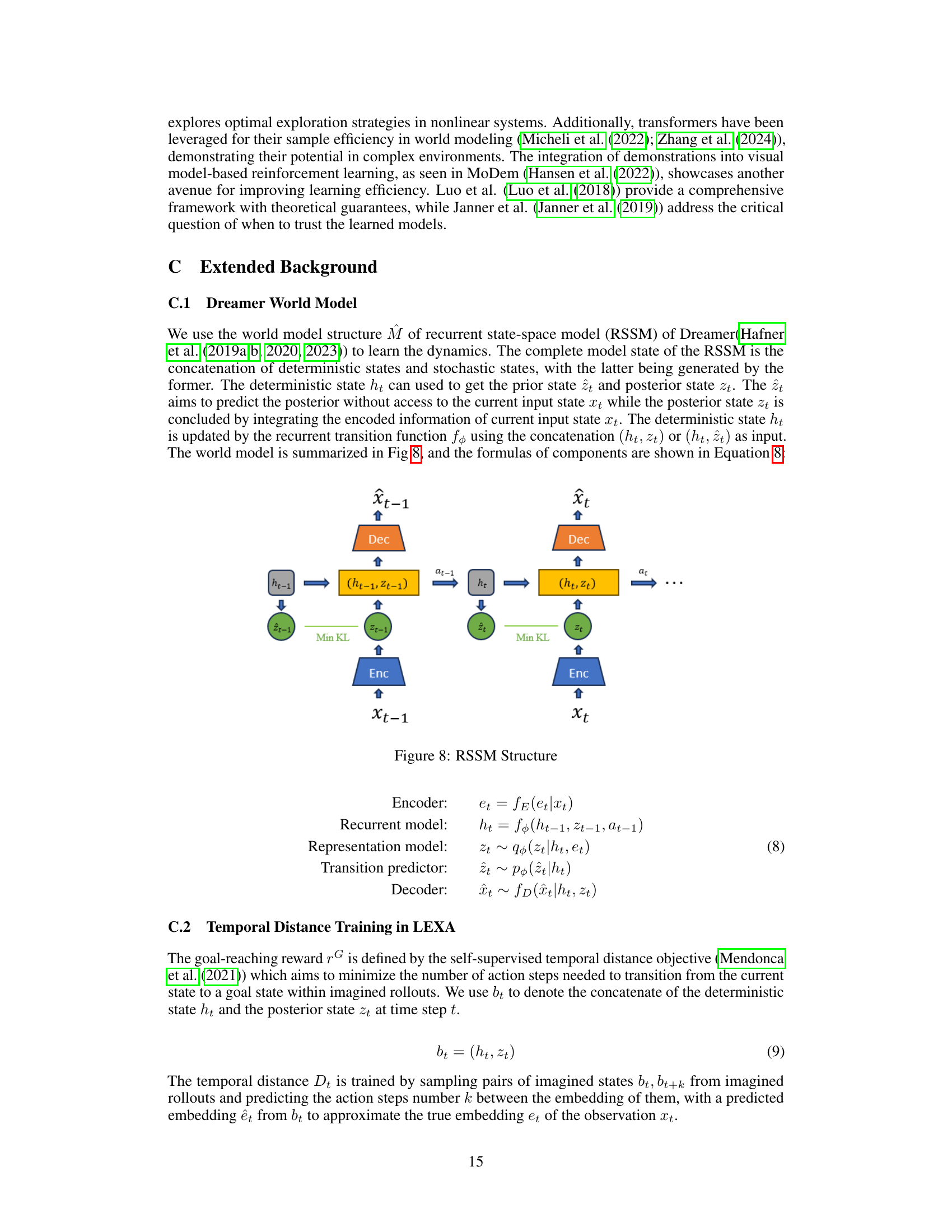

The proposed “Cluster Edge Exploration” method tackles the challenge of efficient exploration in goal-conditioned reinforcement learning by prioritizing goal states on the boundaries of easily reachable state clusters. This approach cleverly combines clustering states in a latent space based on their reachability with the current policy and then strategically selecting goals at cluster edges. This addresses the limitation of existing methods that often select goals that are difficult for the current policy to reach, thus hindering exploration. By focusing on accessible frontier states, CE2 enhances the agent’s ability to explore novel areas systematically, improving exploration efficiency and ultimately leading to faster learning. The method’s effectiveness is demonstrated through experiments in challenging robotics environments, highlighting the importance of combining reachability with exploration potential for efficient, goal-directed exploration strategies. The use of latent space clustering provides a robust and scalable solution that can be applied to a wider range of exploration problems in reinforcement learning.

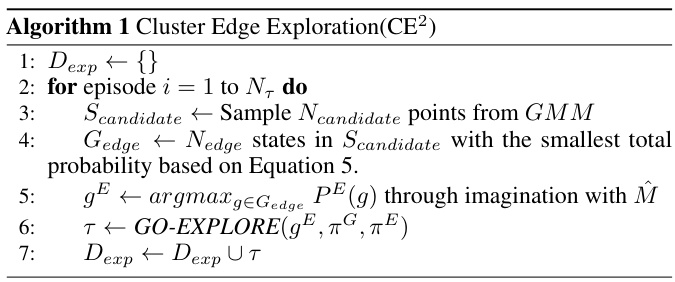

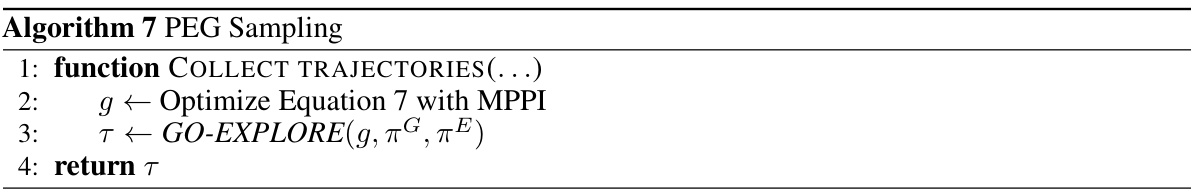

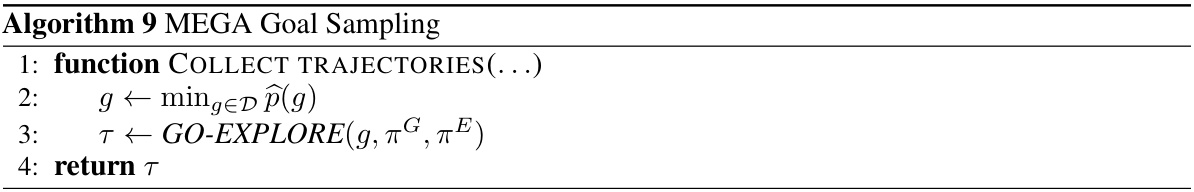

Go-Explore enhanced#

Go-Explore is a popular exploration strategy in reinforcement learning, particularly effective in goal-conditioned settings. However, a key challenge is selecting truly useful exploration goals. Go-Explore enhanced approaches focus on improving goal selection, often by incorporating learned world models or using heuristics based on state density or novelty. These enhancements aim to guide the agent towards states with high exploration value, mitigating the limitations of randomly selecting frontier goals, which might be inaccessible to the current policy. The effectiveness of enhanced Go-Explore methods hinges on the accuracy of its goal selection process. Clever heuristics are needed to balance exploration potential against the agent’s ability to reach the proposed goal. World models can be particularly helpful in this regard by simulating trajectories and evaluating the potential exploration reward from different goals. However, model-based methods introduce computational overhead; the trade-off between better goal selection and increased computational complexity needs careful consideration when choosing the best Go-Explore variant.

Latent Space Learning#

The concept of ‘Latent Space Learning’ within the context of unsupervised goal-conditioned reinforcement learning is crucial for effective exploration. The core idea is to encode high-dimensional observations into a lower-dimensional latent space, where the distances between points meaningfully reflect the agent’s ability to reach them. This encoding must capture both the structure of the environment and the agent’s current policy. A key innovation is using a loss function that combines reconstruction error with temporal distance, ensuring the latent space reflects reachability under the learned policy. This allows for clustering of easily reachable states, enabling the identification of exploration goals at the edges of these clusters. By focusing on the boundaries of these clusters, the algorithm prioritizes exploration in areas that are both promising and accessible to the agent, thus increasing the efficiency of exploration. The careful design of the latent space is therefore key to the algorithm’s success.

Robotics Experiments#

A hypothetical “Robotics Experiments” section would likely detail the experimental setup, methodologies, and results of applying the proposed algorithm (e.g., Cluster Edge Exploration) to robotic tasks. This would involve describing the specific robotic platforms used (ant robot, robotic arm, anthropomorphic hand), the environments designed to test exploration capabilities (maze, cluttered tabletop, object manipulation), and metrics used to evaluate performance (success rate, exploration efficiency, training time). A thorough analysis would compare the novel algorithm’s performance against established baselines in each robotic scenario, emphasizing quantitative and possibly qualitative results. Key aspects to highlight would be the algorithm’s ability to efficiently explore sparse reward environments by prioritizing accessible goal states, as well as any observed limitations or challenges encountered during the experiments. The discussion should also analyze the influence of the algorithm’s components on the overall effectiveness. Finally, the results would ideally include visualizations such as plots showcasing the exploration progress and goal achievement over time across different robotic environments.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section hints at several crucial areas needing further investigation. Extending CE2 to model-free settings is vital for broader applicability, as model-based approaches often have high computational demands. Addressing the algorithm’s current reliance on a well-trained latent space is also critical; improvements to latent space learning robustness could significantly improve performance. Tackling more challenging robotics tasks involving fine manipulation or complex dynamics (like inserting a peg or fluid manipulation) will rigorously test CE2’s capabilities and highlight its limitations. Finally, exploring alternative methods for sampling goal commands is crucial for optimizing exploration efficiency; investigating different state cluster generation or exploration strategy combinations could offer substantial improvements over the current approach. The ultimate goal is to make CE2 a more practical and broadly applicable tool for complex real-world exploration tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

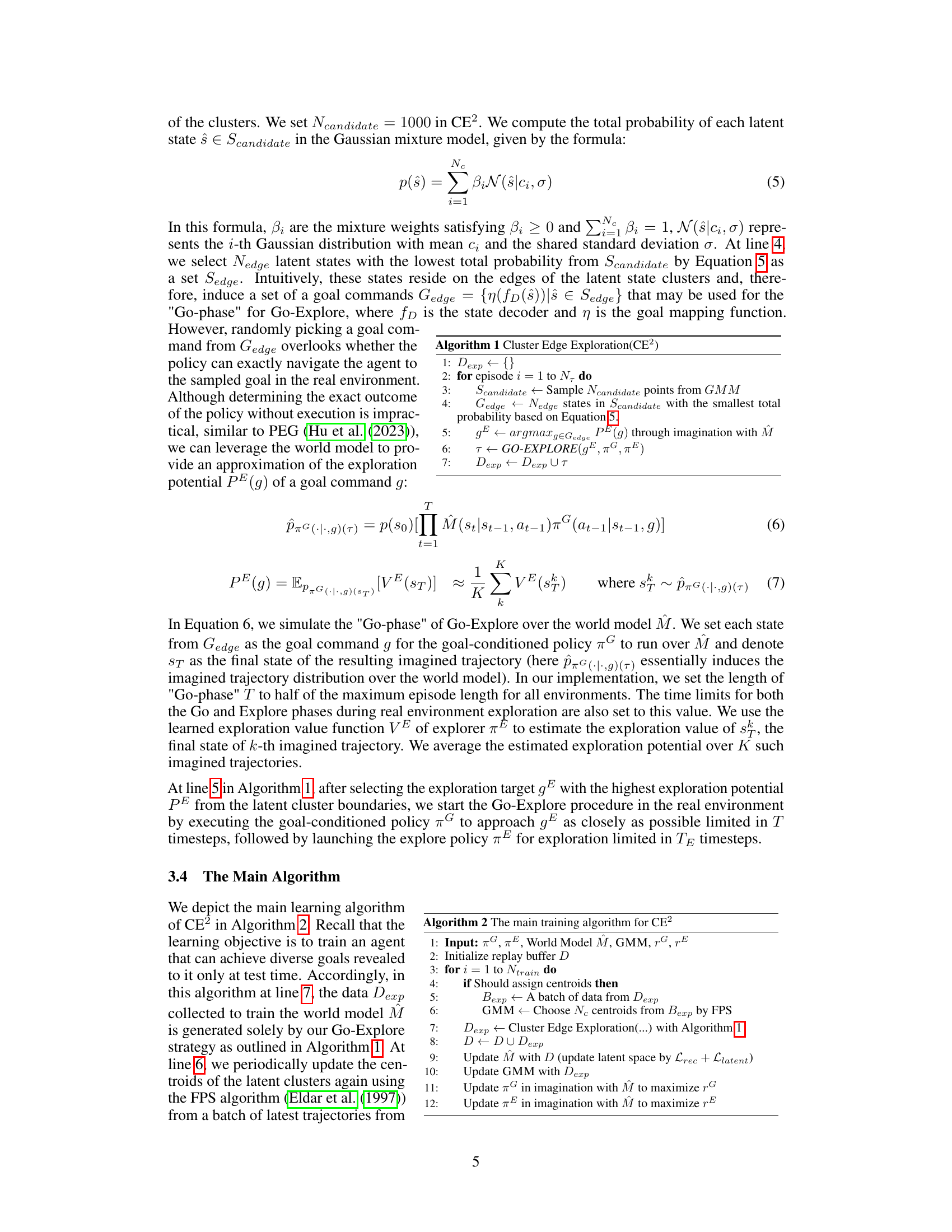

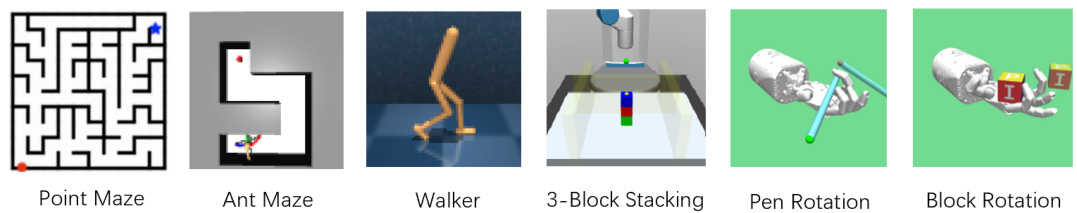

🔼 This figure shows six different simulated robotic environments used to evaluate the performance of the proposed Cluster Edge Exploration (CE2) algorithm. These diverse environments test the algorithm’s ability to explore effectively in various scenarios, ranging from simple navigation (Point Maze) to complex manipulation tasks (3-Block Stacking). Each environment presents unique challenges in terms of state space complexity, action space dimensionality, and reward sparsity, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of the algorithm’s generalization capabilities.

read the caption

Figure 2: We conduct experiments on 6 environments: Point Maze, Ant Maze, Walker, 3-Block Stacking, Block Rotation, Pen Rotation.

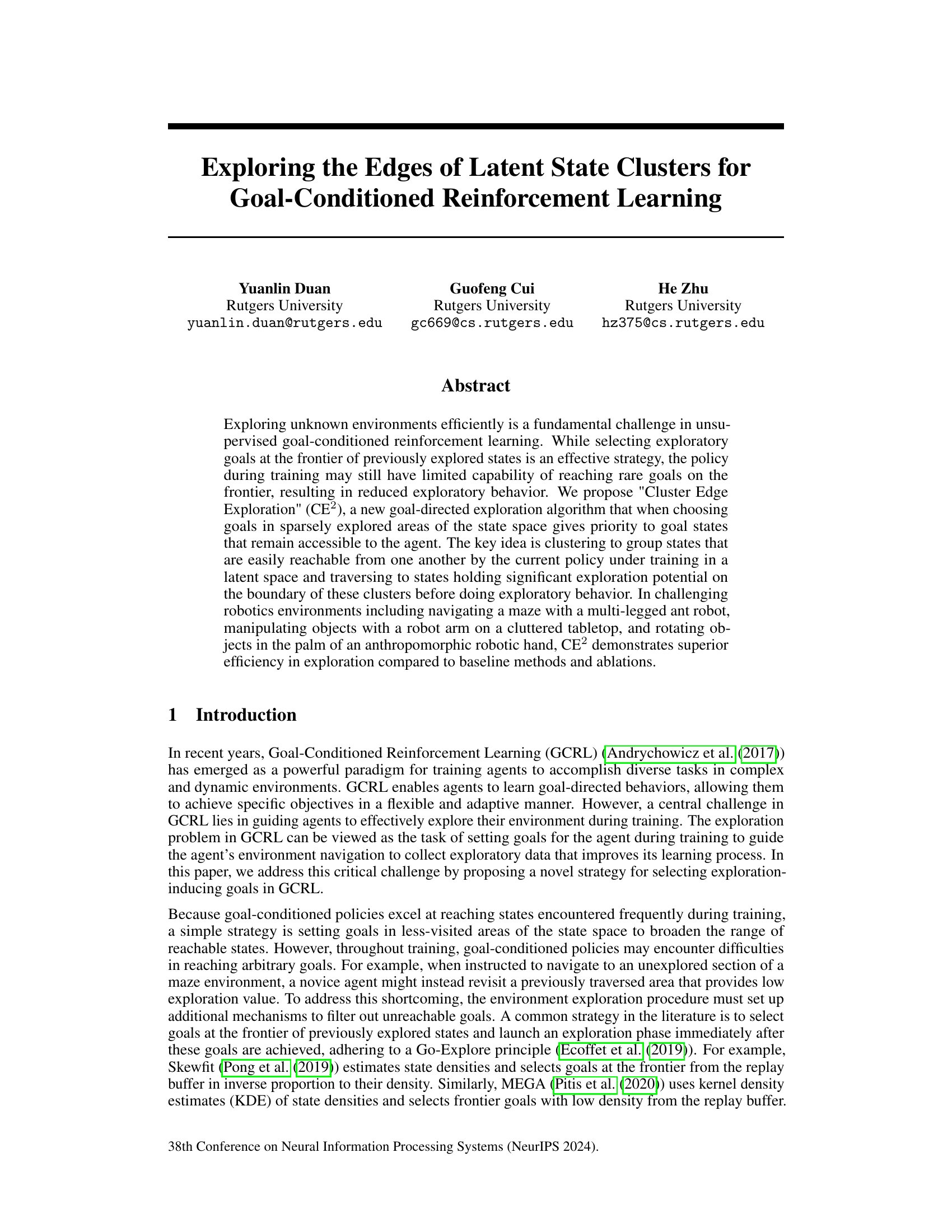

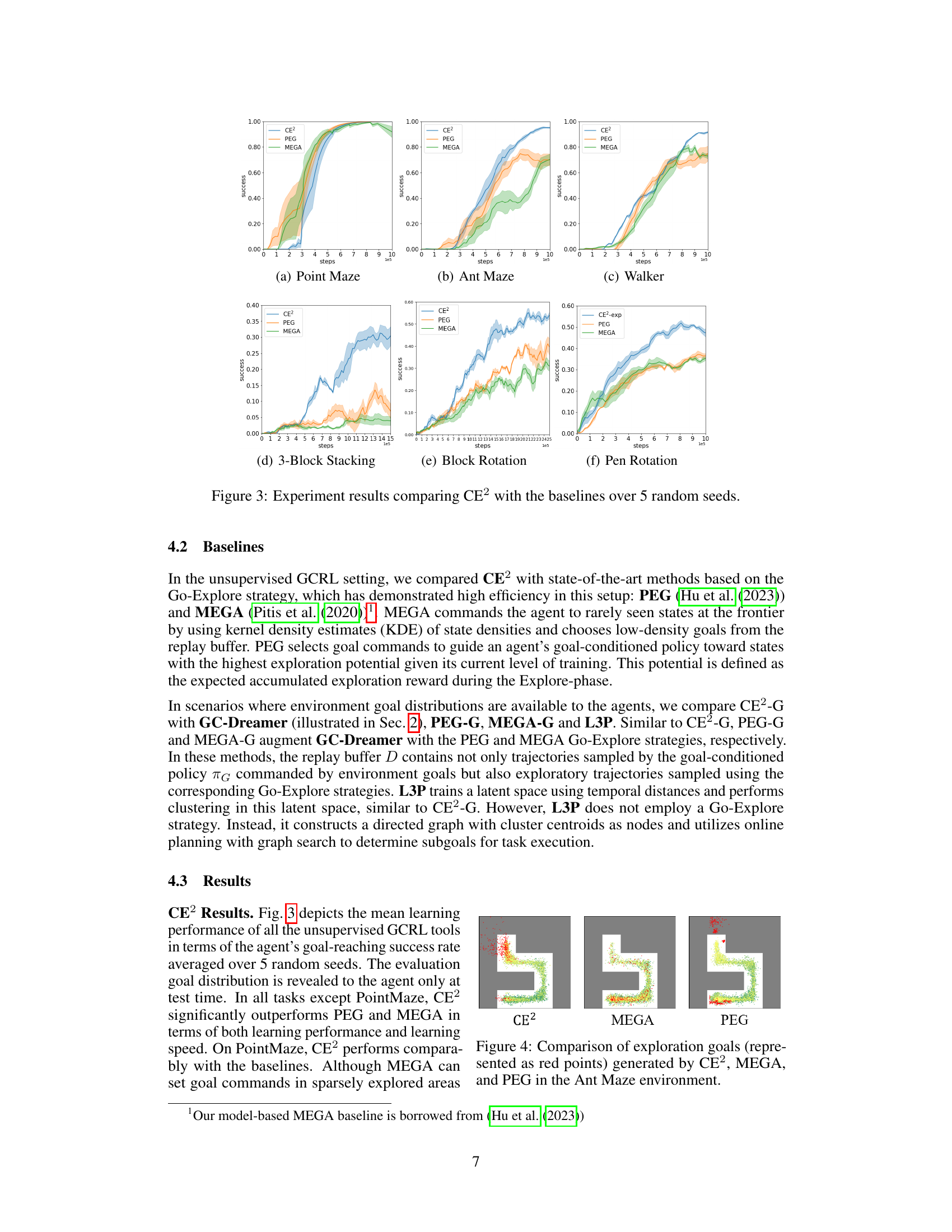

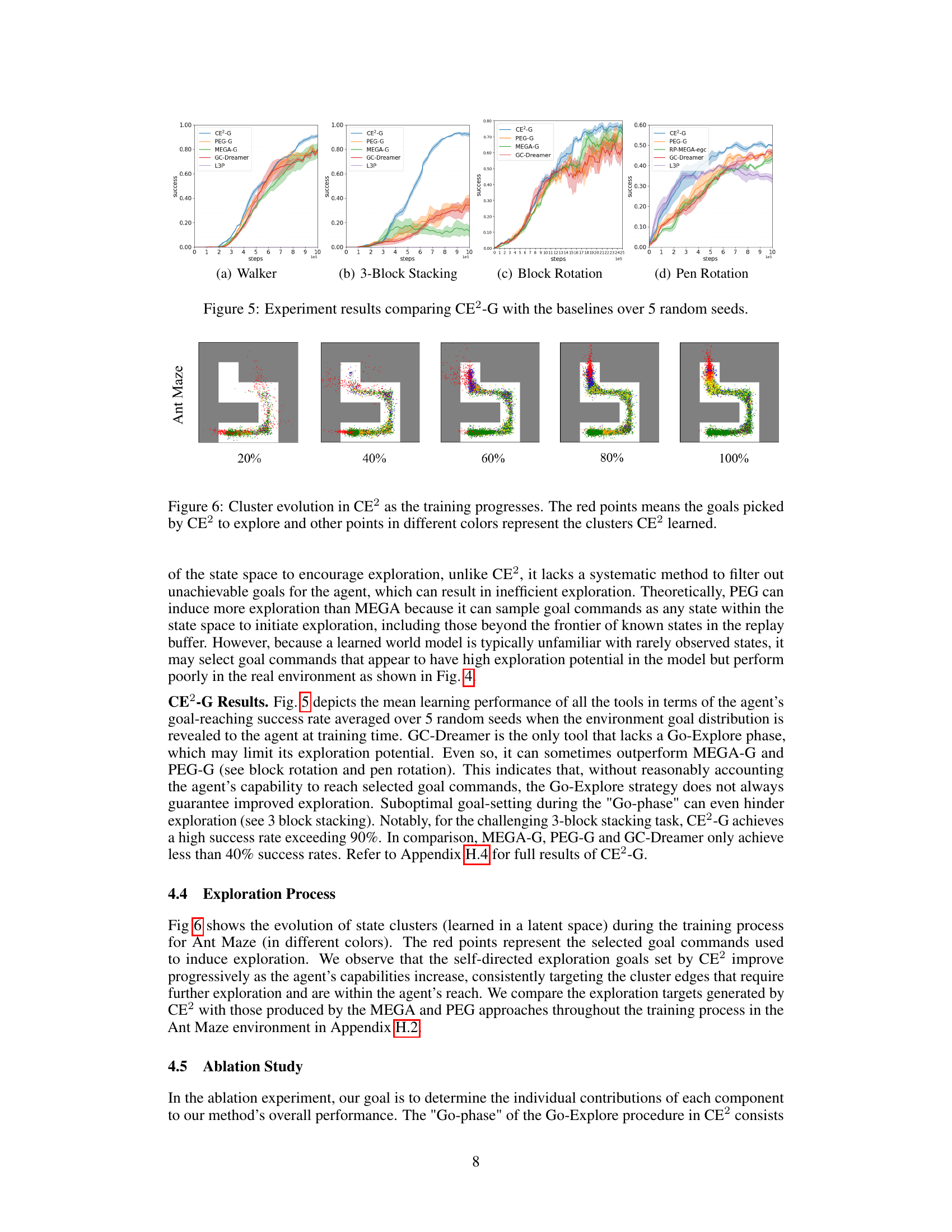

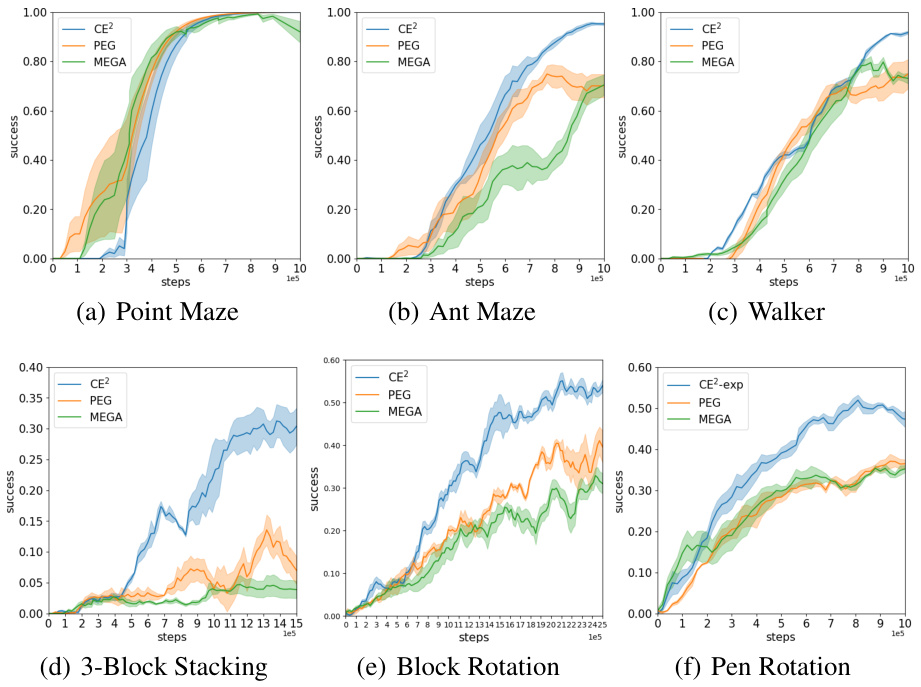

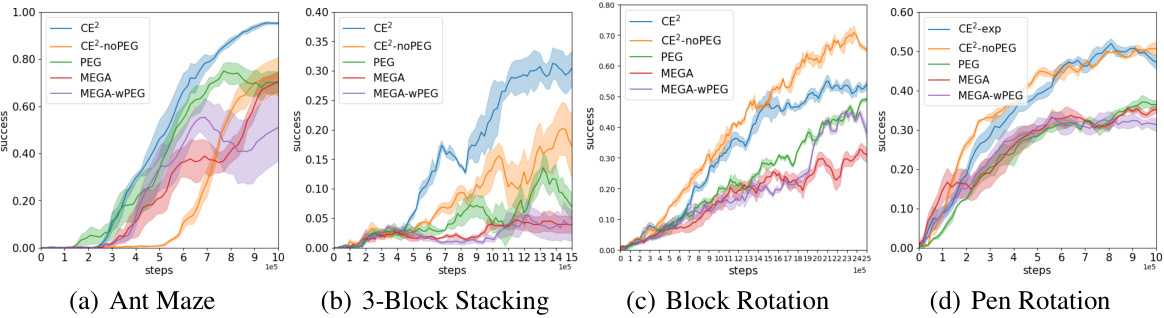

🔼 This figure displays the mean learning performance of CE2 and three baseline methods (PEG, MEGA, and a variant of CE2) across six different goal-conditioned reinforcement learning tasks. The x-axis represents the number of steps, and the y-axis represents the success rate (averaged over 5 random seeds). The shaded regions indicate standard deviations. The figure demonstrates CE2’s superior performance in most tasks compared to the baselines, particularly in terms of speed and success rate.

read the caption

Figure 3: Experiment results comparing CE2 with the baselines over 5 random seeds.

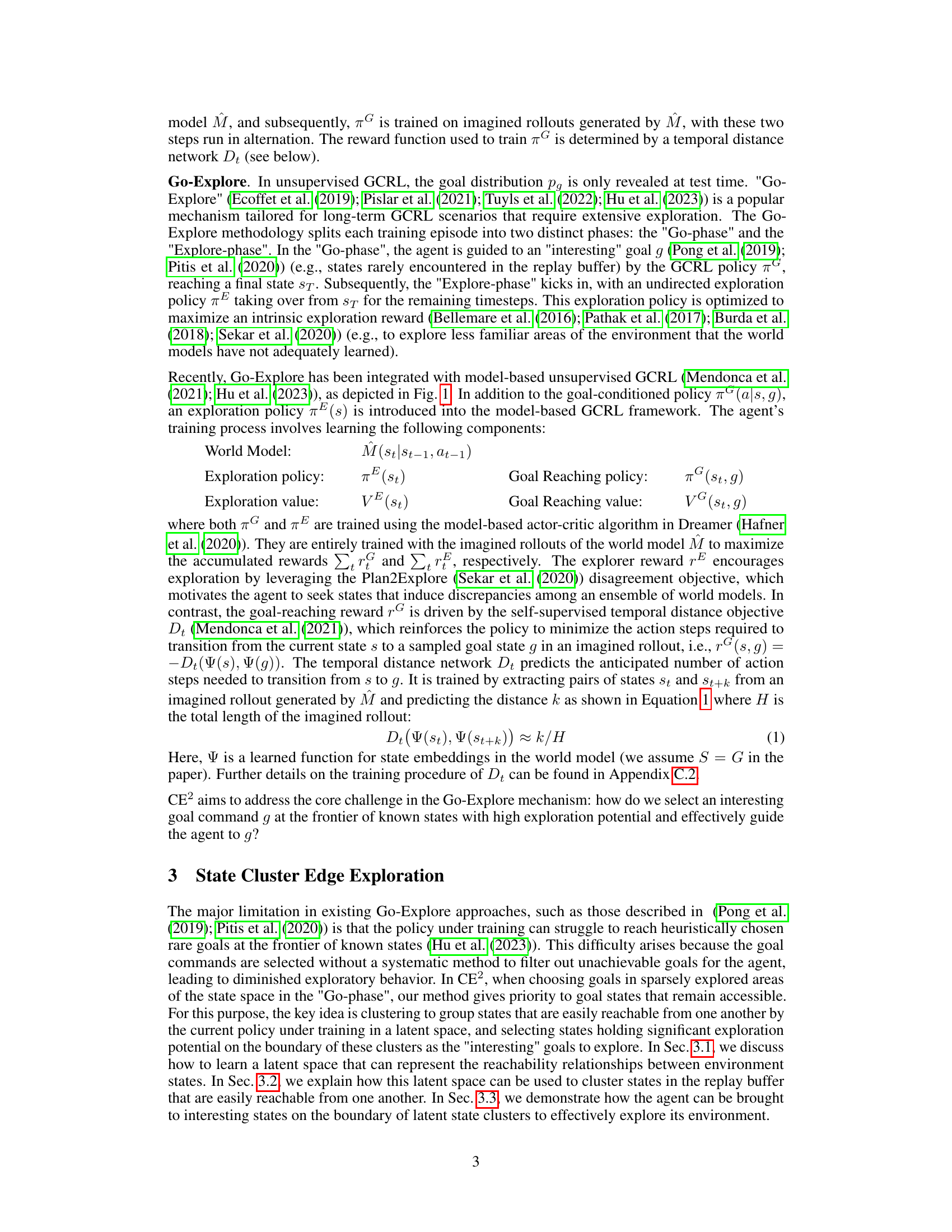

🔼 This figure compares the exploration strategies of three different algorithms: CE², MEGA, and PEG, within the Ant Maze environment. Each algorithm selects goals to guide the agent’s exploration, with the goals represented by red points on the maze map. The color gradient indicates the order in which states are visited during exploration, going from green (visited earlier) to yellow (visited later). The figure visually demonstrates how each algorithm approaches exploration differently, showing the distribution and selection of exploration goals.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison of exploration goals (represented as red points) generated by CE², MEGA, and PEG in the Ant Maze environment.

🔼 This figure presents the learning performance of CE2 and three baseline methods (PEG, MEGA, and MEGA-wPEG) across six different goal-conditioned reinforcement learning tasks. The y-axis represents the success rate (probability of the agent successfully reaching a goal), and the x-axis represents the number of steps taken. The shaded regions around the lines indicate the standard deviation across five runs with different random seeds. This visualization shows the comparative performance of the proposed CE2 algorithm and its baseline counterparts. Note that all six environments are for unsupervised GCRL settings.

read the caption

Figure 3: Experiment results comparing CE2 with the baselines over 5 random seeds.

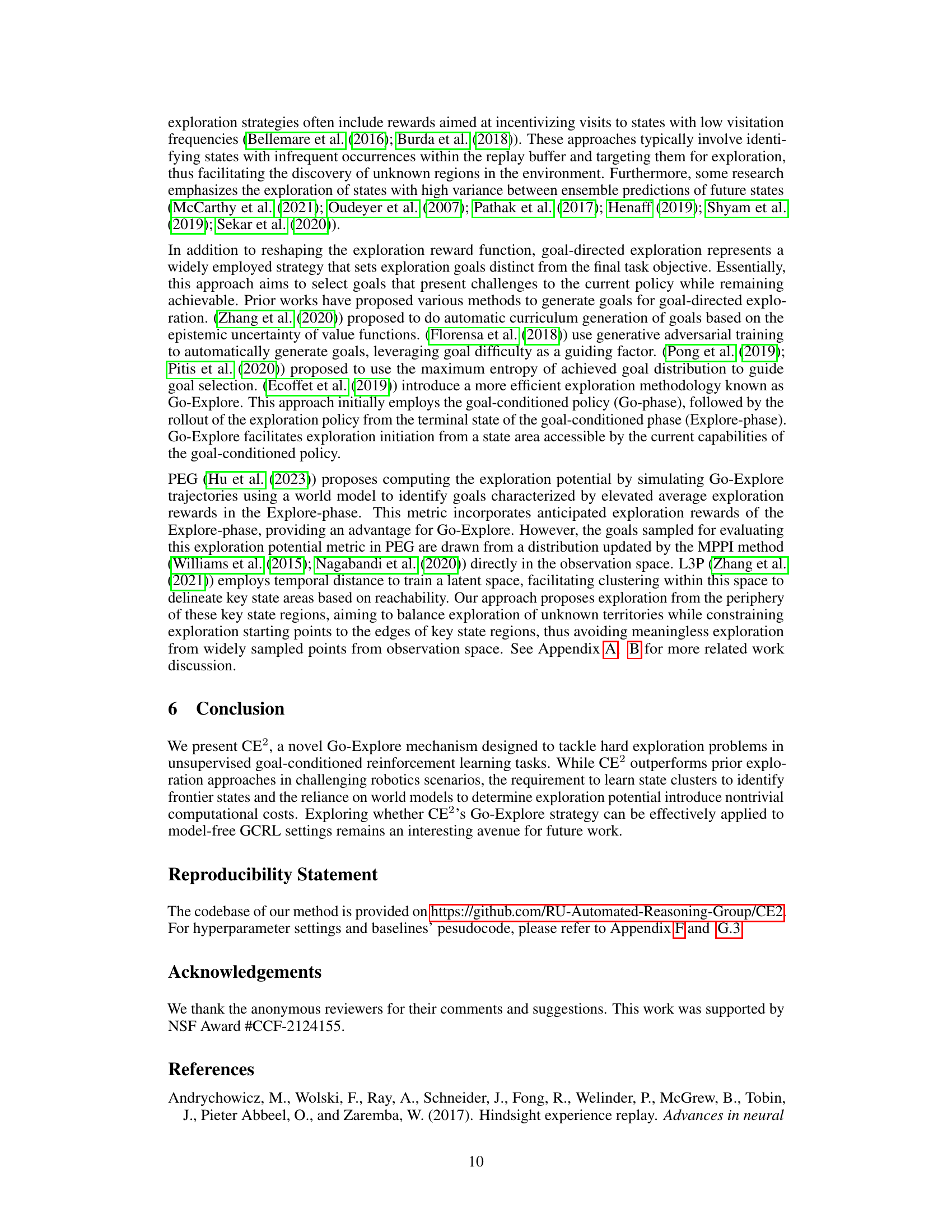

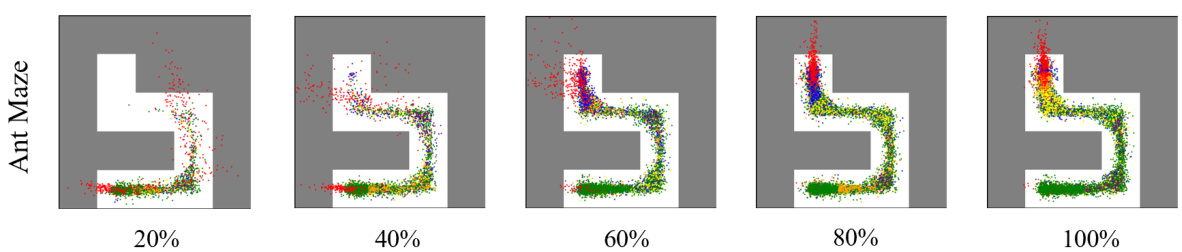

🔼 This figure visualizes how the state clusters learned by the CE2 algorithm evolve during the training process. Each color represents a different cluster, grouping states easily reachable from one another by the current policy. Red points represent the goals (states) selected by CE2 for exploration. The figure shows that the exploration goals selected by CE2 are located at the boundaries of state clusters. The visualization helps to understand how the method effectively explores previously unseen state regions in the environment by moving to the boundaries of already-explored regions and building up the clusters over time.

read the caption

Figure 6: Cluster evolution in CE2 as the training progresses. The red points means the goals picked by CE2 to explore and other points in different colors represent the clusters CE2 learned.

🔼 This figure displays the mean learning performance of different unsupervised GCRL methods (CE2, PEG, and MEGA) across six challenging robotics tasks. The y-axis represents the success rate in achieving goals, averaged over five different random seeds. The x-axis shows the number of steps in the training process. The figure showcases CE2’s superior performance compared to the baselines in most tasks, indicating its effectiveness in improving goal-reaching efficiency by prioritizing accessible goals for exploration.

read the caption

Figure 3: Experiment results comparing CE2 with the baselines over 5 random seeds.

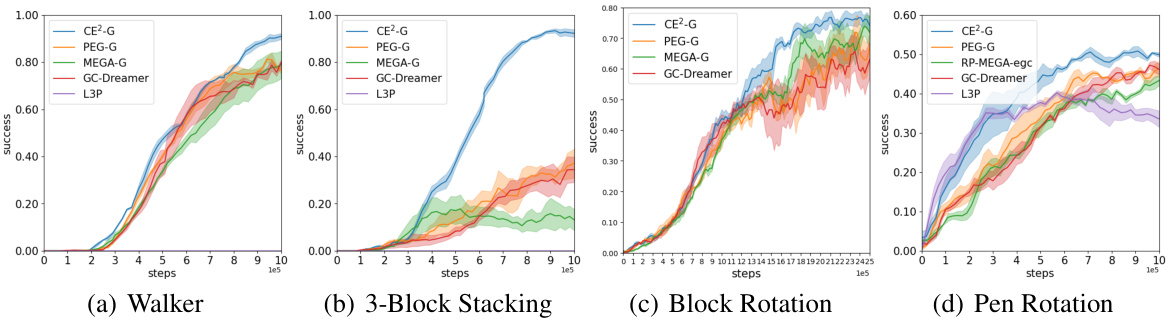

🔼 This figure illustrates the key difference between the proposed CE2-G method and other conventional exploration methods. In CE2-G, the agent explores by targeting goal states located at the boundaries of latent state clusters. The clusters represent regions where the agent’s current policy is familiar. In contrast, other exploration methods may select goal states randomly in less-explored areas of the state space, even if those states are not easily reachable by the current agent’s policy. The figure shows how CE2-G strategically selects goals along the boundaries of known regions, leading to more efficient and targeted exploration.

read the caption

Figure 9: Illustration of differences between our mothod CE2-G and other exploration methods.

🔼 This figure compares the exploration performance of CE2 and PEG in the 3-Block Stacking environment after 1 million steps. The x-axis represents the sum of the lengths of the sides of a triangle formed by connecting the centers of the three blocks, projected onto the x-y plane. The y-axis represents the sum of the z-coordinates (heights) of the three blocks. The plot shows the distribution of visited states, with the color gradient indicating the recency of visits (green for older, yellow for more recent). Red points represent the evaluation goals. The figure highlights that CE2 explores more effectively around the target goal region, while PEG’s exploration is more dispersed.

read the caption

Figure 10: Space explored by CE2 and PEG in the 3-Block Stacking environment at 1M steps. X-axis: the sum of the three sides of the triangle projected on the x-y plane by the three block-connected triangles. Y-axis: sum of heights (z-coordinates) of the three blocks. Red points: evaluation goals. Other points: observations of trajectories sampled in real environment. Color from green to yellow means to be sampled more recent.

🔼 This figure compares the exploration goals generated by three different algorithms: CE2, MEGA, and PEG, across various stages (10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 60%) of the training process in the Ant Maze environment. Each subplot shows the maze layout and the locations of the exploration goals (red points) generated by each algorithm at a specific training percentage. The figure visually demonstrates the differences in exploration strategies, highlighting CE2’s tendency to select goals near the frontiers of explored areas compared to MEGA and PEG, which often select goals further away from the currently known areas.

read the caption

Figure 11: Comparison of exploration goals generated by CE2, MEGA and PEG

🔼 This figure presents the learning performance comparison of CE2 against other unsupervised GCRL methods (PEG and MEGA) across six different challenging robotics environments. The success rate (y-axis) is plotted against the number of steps (x-axis). The plots show the mean success rate with shaded regions representing the standard deviation across five random seeds for each method. The results highlight CE2’s superior performance in most environments, demonstrating its improved exploration and goal-reaching capabilities.

read the caption

Figure 3: Experiment results comparing CE2 with the baselines over 5 random seeds.

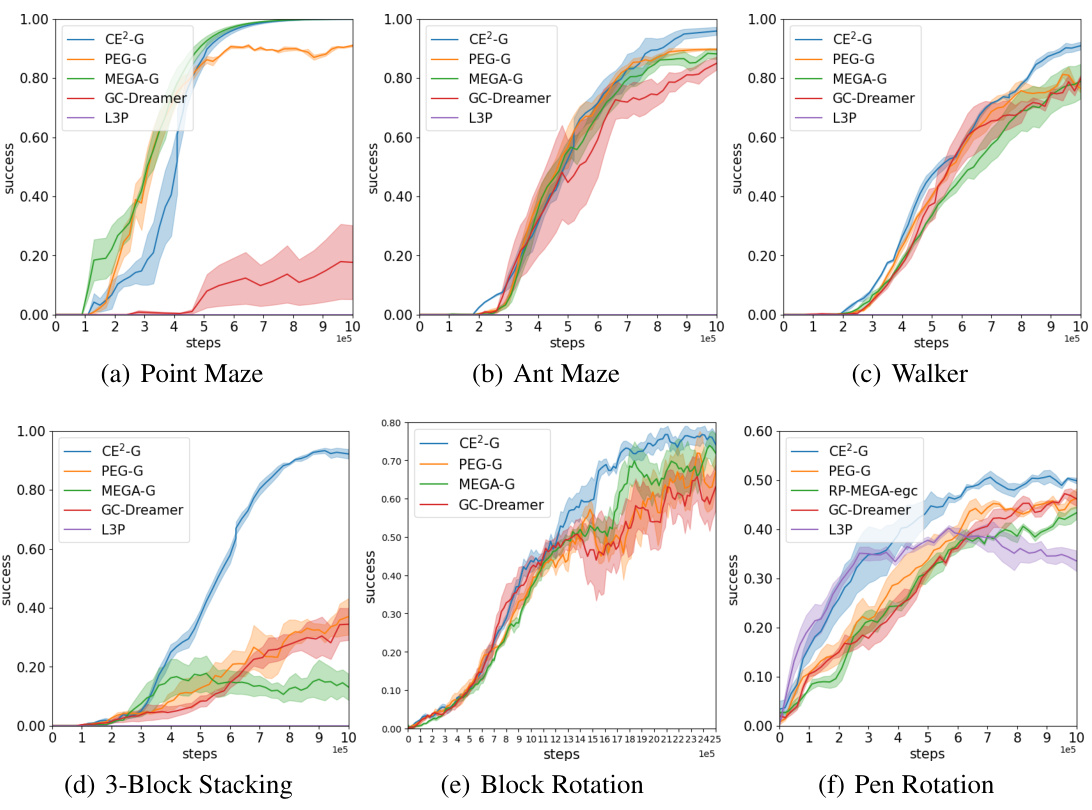

🔼 This figure presents the experimental results comparing the performance of CE2 with several baseline methods across six different robotic tasks. Each subplot represents a specific task (Point Maze, Ant Maze, Walker, 3-Block Stacking, Block Rotation, Pen Rotation). The x-axis represents the number of steps, and the y-axis shows the success rate. The lines represent the average success rate over five different random seeds for each algorithm, while the shaded area depicts the standard deviation, showcasing the robustness of each method’s performance. The figure visually demonstrates that CE2 generally outperforms the baseline methods (PEG and MEGA) in terms of both speed and success rate, particularly in more complex tasks such as 3-Block Stacking, Block Rotation and Pen Rotation.

read the caption

Figure 3: Experiment results comparing CE2 with the baselines over 5 random seeds.

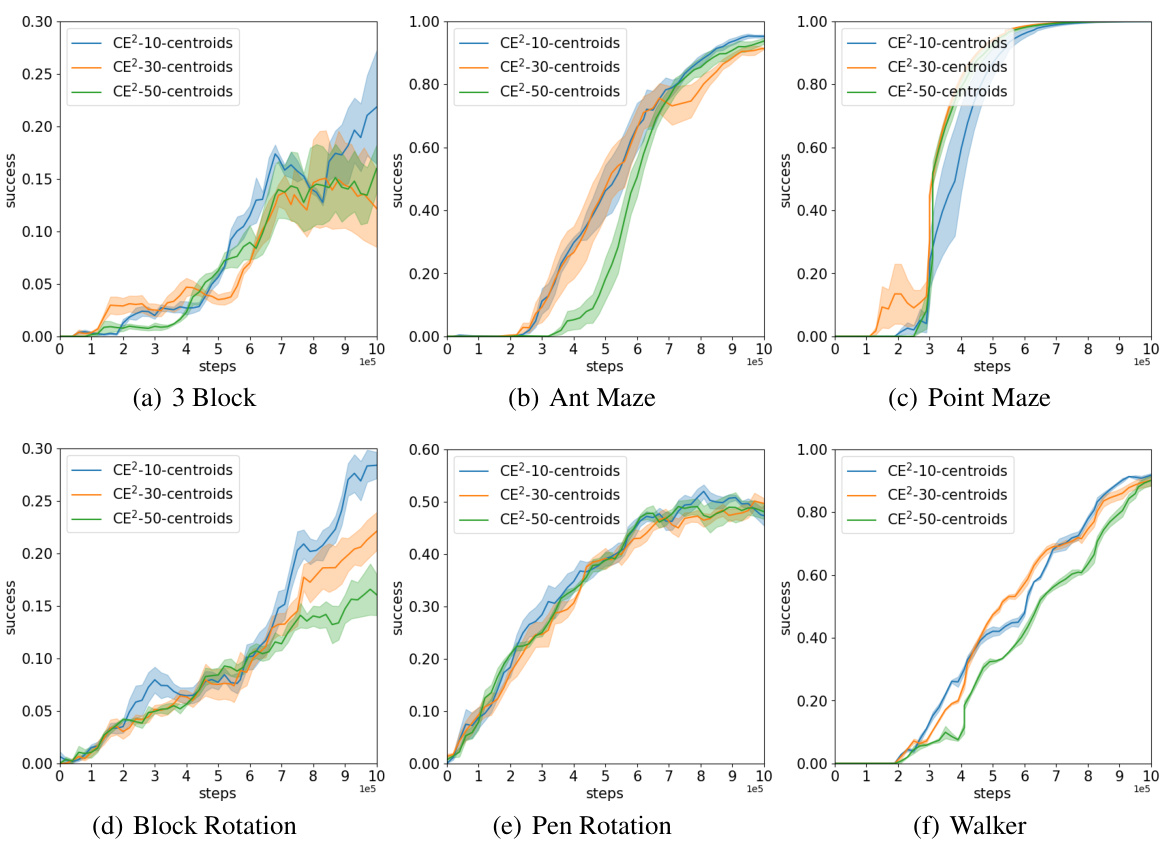

🔼 This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted to assess the impact of varying the number of clusters (10, 30, 50) used in the CE2 algorithm on the success rate of goal-reaching tasks across different environments. Each subfigure corresponds to a specific environment: (a) 3-Block Stacking, (b) Ant Maze, (c) Point Maze, (d) Block Rotation, (e) Pen Rotation, and (f) Walker. The x-axis represents the number of steps taken, while the y-axis shows the success rate. The results indicate that CE2’s performance is relatively insensitive to the choice of cluster number within the tested range, suggesting robustness of the approach.

read the caption

Figure 14: Ablation Study with Different Cluster Number.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the runtime statistics for each experiment conducted in the study. The experiments were performed on an Nvidia A100 GPU with approximately 5GB of memory. The table shows the total runtime in hours, total number of steps, episode length, and seconds per episode for six different environments: 3-Block Stacking, Walker, Ant Maze, Point Maze, Block Rotation, and Pen Rotation. The table highlights the computational cost associated with each experiment, illustrating the time efficiency (or inefficiency) of the different experimental settings.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table presents the computational cost of the proposed CE2 algorithm and baselines across six different reinforcement learning environments. It shows the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps taken, the length of each episode in steps, and the average time spent per episode in seconds. The table provides insights into the computational efficiency of the different methods, enabling a comparison of their resource requirements.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table presents the runtime statistics for each experiment conducted in the paper. It breaks down the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps taken, the episode length (number of steps per episode), and the time taken per episode in seconds. The experiments covered include 3-Block Stacking, Walker, Ant Maze, Point Maze, Block Rotation, and Pen Rotation. The data provides insights into the computational cost and efficiency of each experimental task.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table shows the runtime statistics for each of the six experiments conducted in the paper. It provides the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps taken during the experiment, the episode length, and the average number of seconds it took to complete a single episode for each experiment. The experiments are: 3-Block Stacking, Walker, Ant Maze, Point Maze, Block Rotation, and Pen Rotation.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table presents the runtime statistics for each experiment conducted in the study. It shows the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps taken, the episode length, and the number of seconds per episode for six different environments: 3-Block Stacking, Walker, Ant Maze, Point Maze, Block Rotation, and Pen Rotation. These statistics provide insights into the computational cost and efficiency of the experiments.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table shows the runtime statistics for each experiment conducted in the paper, broken down by environment. It includes the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps taken, the episode length, and the average number of seconds per episode. This data provides insights into the computational cost and efficiency of the proposed CE2 algorithm compared to baseline methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table presents the runtime statistics for each experiment conducted in the paper. It details the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps taken during each experiment, the length of each episode, and the average number of seconds required per episode for six different environments: 3-Block Stacking, Walker, Ant Maze, Point Maze, Block Rotation, and Pen Rotation. This information allows readers to gauge the computational cost and efficiency of the experiments performed.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table presents the runtime statistics for each experiment conducted in the paper, broken down by environment. It shows the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps simulated, the episode length, and the average seconds per episode. The data provides insights into the computational cost of the proposed method and baselines across different task complexities.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table presents the runtime statistics for each experiment conducted in the paper, broken down by environment. It shows the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps, the episode length, and the average seconds per episode. These metrics provide a quantitative assessment of the computational demands of the different experimental tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table presents the computational cost of the proposed CE2 algorithm and its variants across different robotic environments. It shows the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps, the length of each episode, and the average time (in seconds) spent per episode for each environment. This provides a measure of the computational efficiency of the algorithm across various tasks of varying complexity.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table shows the runtime statistics for each experiment conducted in the paper. The experiments were performed on an Nvidia A100 GPU with approximately 5GB of memory. The table lists the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps, the episode length (in timesteps), and the average time (in seconds) required to complete a single episode for each of the six environments (3-Block Stacking, Walker, Ant Maze, Point Maze, Block Rotation, Pen Rotation). The runtime data provides insights into the computational cost and efficiency of the different experiments.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

🔼 This table presents the computational cost of the experiments conducted in the paper. For each of the six environments (3-Block Stacking, Walker, Ant Maze, Point Maze, Block Rotation, Pen Rotation), it shows the total runtime in hours, the total number of steps taken, the episode length in steps, and the time taken per episode in seconds. This helps to give an understanding of the resource requirements of the experiments and to compare the relative computational costs of the different environments.

read the caption

Table 1: Runtimes per experiment.

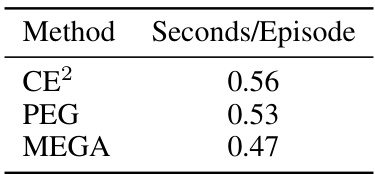

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the computation time required by three different methods (CE², PEG, and MEGA) to optimize goal states for launching the Go-Explore procedure in the 3-Block Stacking environment. The time is measured in seconds per episode.

read the caption

Table 2: Computation time needed to optimize goal states

Full paper#