TL;DR#

Generating realistic 3D models of molecules is crucial for drug discovery and materials science. However, current methods face challenges in scalability and computational efficiency, particularly for large molecules. Many existing approaches rely on discrete representations (point clouds or voxel grids), limiting their expressiveness and hindering their ability to handle complex structures. The message passing mechanism of graph neural networks (GNNs) used in some approaches also limits their expressiveness and scalability.

This paper introduces FuncMol, a novel generative model that uses continuous neural fields to represent 3D molecules. FuncMol uses a conditional neural field to encode molecular fields into latent codes. It then employs a score-based neural empirical Bayes approach and Langevin MCMC to generate new molecules. The method outperforms existing techniques in terms of speed and scalability, particularly with large molecules. FuncMol achieves competitive results on drug-like molecules and easily scales to macrocyclic peptides, demonstrating its potential for various applications in life science research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in cheminformatics and machine learning due to its novel approach to 3D molecule generation using neural fields. It addresses the limitations of existing methods by offering improved scalability and efficiency, opening exciting avenues for drug discovery and materials science. The faster sampling and improved performance on larger molecules make this research highly relevant to current trends in generative modeling.

Visual Insights#

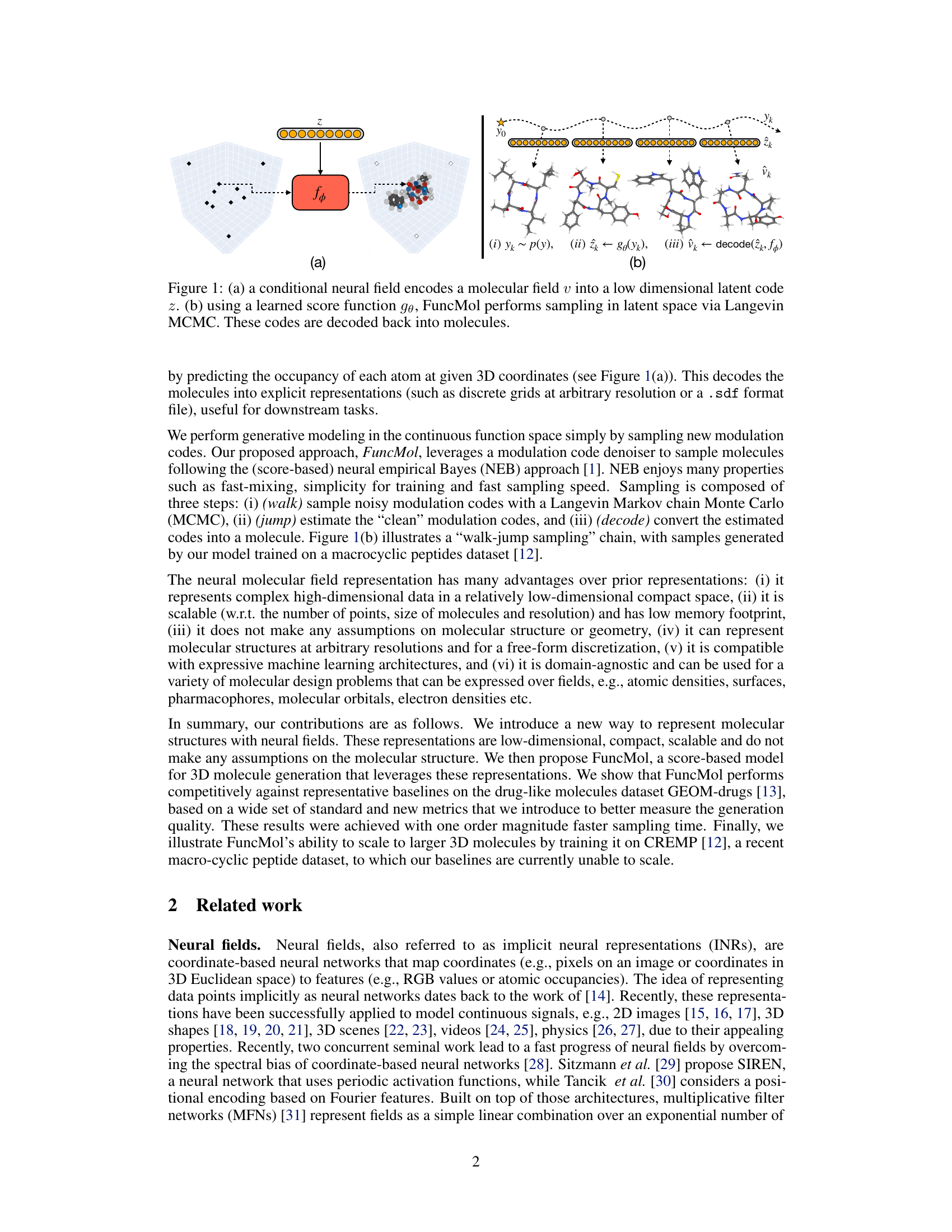

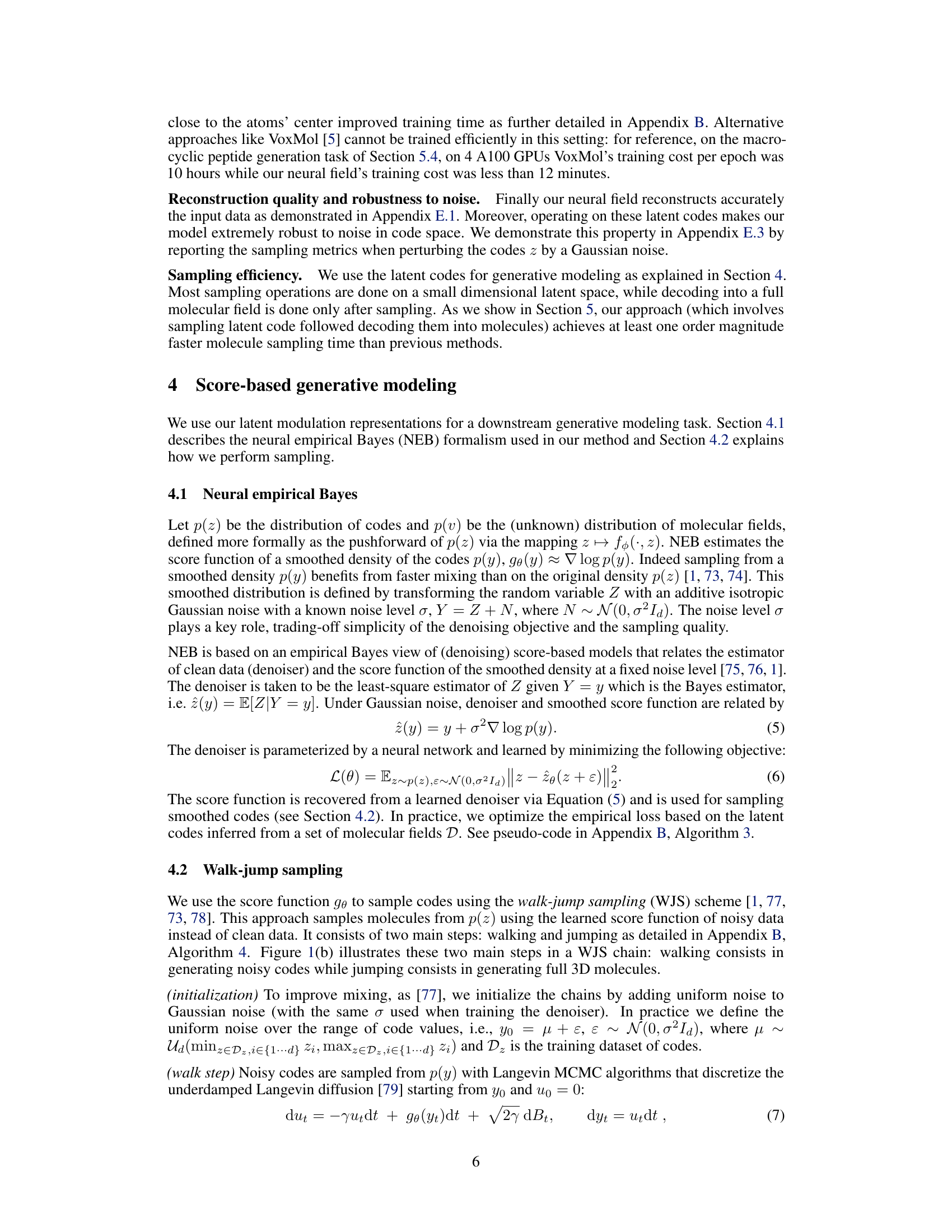

🔼 This figure shows the overall architecture of the FuncMol model. Panel (a) illustrates how a conditional neural field encodes a 3D molecular field representation (atomic density) into a lower-dimensional latent code. Panel (b) depicts the generative process. It uses a learned score function and Langevin Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) to sample noisy codes from a Gaussian-smoothed distribution, denoises them, and decodes these into a final molecular field representation. The process is shown as a walk-jump sampling chain, progressing from noisy samples to more refined samples and finally a complete molecule.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) a conditional neural field encodes a molecular field v into a low dimensional latent code z. (b) using a learned score function ge, FuncMol performs sampling in latent space via Langevin MCMC. These codes are decoded back into molecules.

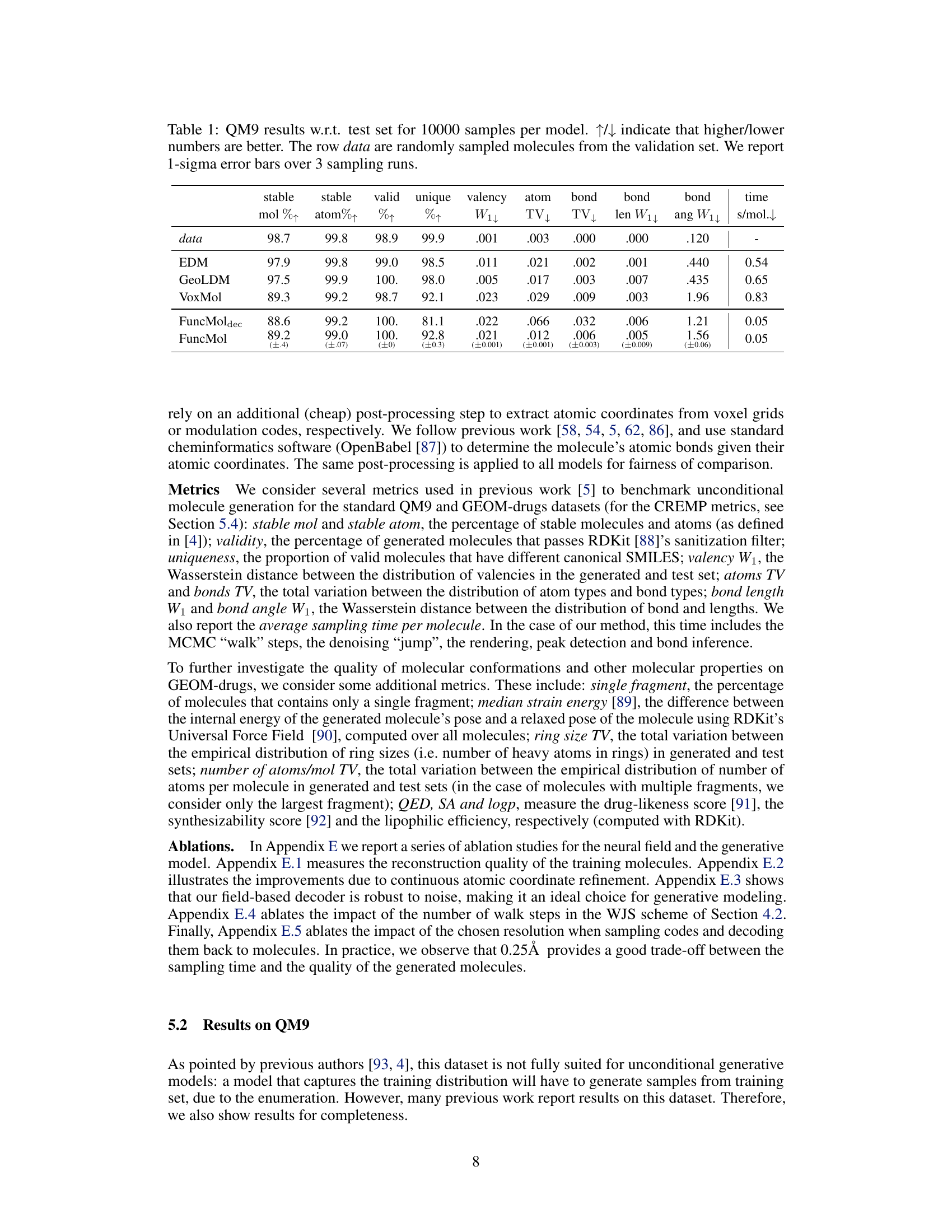

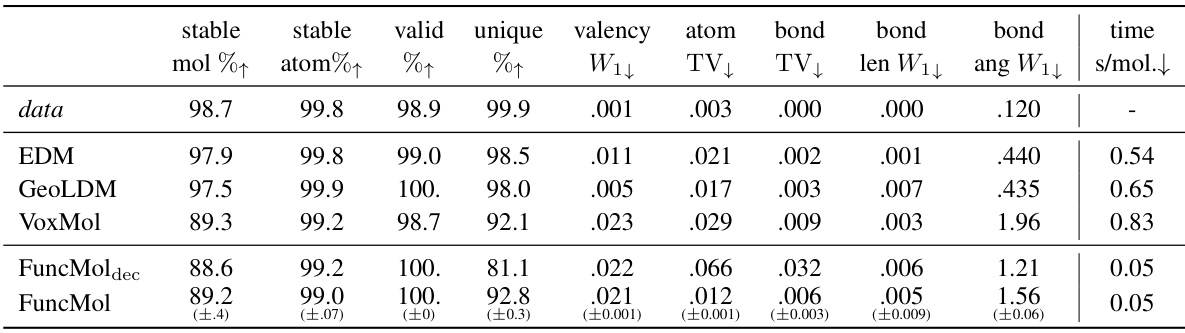

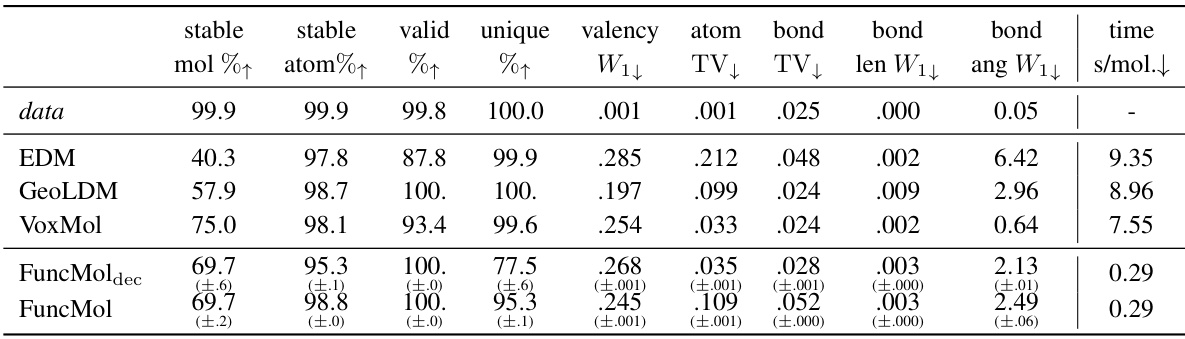

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of the proposed FuncMol model and three baseline models on the QM9 dataset. The models are evaluated based on several metrics including the percentage of stable molecules and atoms, validity, uniqueness, valency, atom and bond distributions, bond length and angle distributions, and sampling time. The metrics show FuncMol’s performance compared to other models and provide a detailed analysis of the generated molecule quality on this small molecule dataset.

read the caption

Table 1: QM9 results w.r.t. test set for 10000 samples per model. ↑↓ indicate that higher/lower numbers are better. The row data are randomly sampled molecules from the validation set. We report 1-sigma error bars over 3 sampling runs.

In-depth insights#

Neural Field Encoding#

Neural field encoding in 3D molecular generation offers a powerful alternative to traditional methods. By representing molecules as continuous atomic density fields, this approach avoids the limitations of discrete representations like point clouds or voxel grids. This continuous representation allows for greater flexibility and scalability, handling molecules of varying sizes and complexities more efficiently. The encoding process itself likely involves mapping these continuous fields into a lower-dimensional latent space using neural networks, capturing essential structural and chemical information in a compact manner. This latent representation then becomes the basis for downstream tasks, such as molecule generation or property prediction. The success of neural field encoding relies heavily on the expressiveness and efficiency of the underlying neural network architecture. The choice of network, the type of activation functions, and the training methodology significantly impact the quality and speed of the encoding and subsequent generation processes. Moreover, careful consideration needs to be given to the method for decoding these latent representations back into explicit 3D molecular structures.

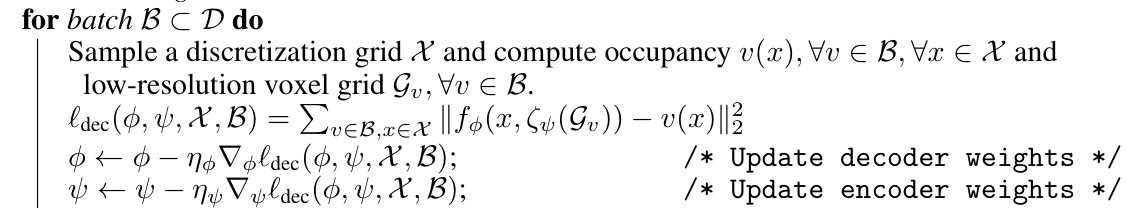

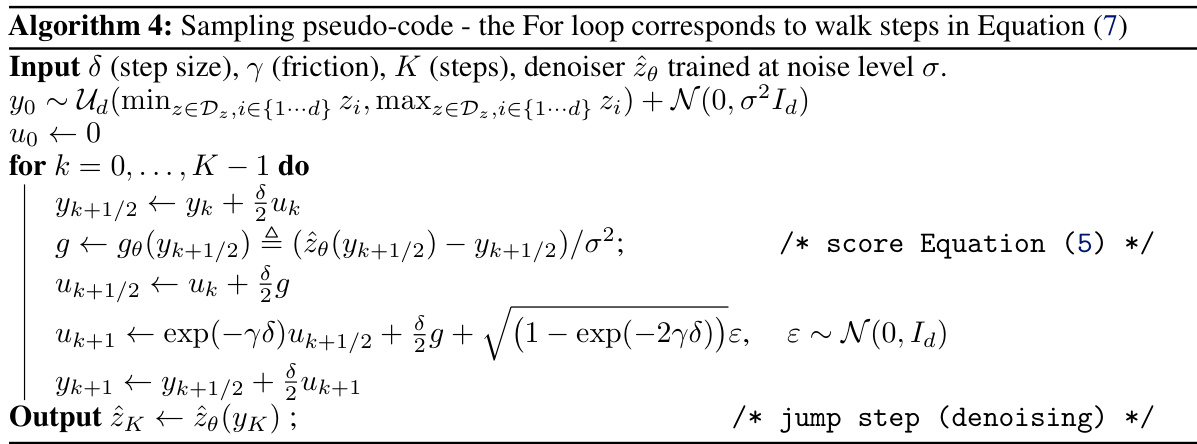

Score-Based Sampling#

Score-based sampling methods offer a powerful approach to generative modeling, particularly for complex data distributions like those encountered in 3D molecular generation. These methods leverage the score function, the gradient of the log-probability density, to guide a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling process. By iteratively adding noise and then denoising based on the score, the process efficiently explores the data distribution, generating high-quality samples. The effectiveness of score-based methods stems from their ability to bypass the need to explicitly model the probability density function, which can be intractable for high-dimensional data such as molecular conformations. The ‘walk’ and ‘jump’ sampling strategies are particularly efficient, with the ‘walk’ phase allowing for efficient exploration of the probability landscape and the ‘jump’ phase offering a mechanism to quickly escape local modes. This technique is particularly advantageous in high-dimensional spaces where traditional sampling approaches often struggle. However, challenges remain; accurate score estimation is crucial, requiring careful model design and training, and the computational cost can still be high for extremely complex molecules.

Macrocycle Scaling#

The ability to effectively model and generate macrocyclic molecules presents a significant challenge in the field of generative modeling for 3D molecules. Standard approaches often struggle with the increased complexity and conformational flexibility inherent in these larger ring systems. A successful macrocycle scaling method must address several key issues. Computational efficiency is critical, as the scaling of computational cost with increasing molecular size can quickly become prohibitive. Therefore, efficient representations and algorithms are necessary. Expressiveness of the model is also vital; it must be able to capture the intricate conformational space explored by macrocycles. The model should be able to generate diverse and realistic macrocycle structures with high accuracy. Finally, robustness to noise is important during the generation process, as the generation task for macrocycles is already complex and prone to failure. A successful method must also be able to handle noise effectively to ensure reliable sampling. Therefore, a thoughtful macrocycle scaling strategy requires a carefully considered combination of novel representations, algorithms, and model architectures to simultaneously achieve high efficiency, expressiveness, and robustness.

Gabor Filter Basis#

Employing Gabor filter basis functions within the context of neural fields for 3D molecular representation offers several compelling advantages. Gabor filters’ inherent multi-scale and orientation selectivity make them well-suited to capture the rich structural details of molecules, which exhibit variations in both size and spatial arrangement of atoms. Unlike simpler basis functions, Gabor filters can effectively encode local features such as bonds, angles, and functional groups, leading to a more expressive and nuanced representation. This characteristic is particularly crucial when dealing with complex and diverse molecular structures. However, using Gabor filters also introduces increased computational complexity compared to other simpler basis sets. The trade-off between computational cost and enhanced representational power needs to be carefully evaluated for specific applications and datasets. The choice of Gabor filters highlights a commitment to capturing the multifaceted nature of molecules beyond simple spatial occupancy, reflecting a thoughtful approach to representation that likely leads to improved generative modeling performance.

Future Directions#

The paper’s ‘Future Directions’ section could explore several promising avenues. Extending FuncMol to handle larger biomolecules is crucial, requiring efficient handling of exponentially increasing conformational space. Incorporating bond information directly into the neural field representation, rather than relying on post-processing, could significantly improve generated molecule quality and validity. The current unconditional approach could be expanded to conditional generation, allowing for targeted molecule design given specific constraints (e.g., desired properties, pharmacophores). Furthermore, investigating alternative neural field architectures beyond MFNs could unlock further improvements in efficiency and expressiveness. Finally, a detailed exploration of FuncMol’s limitations — such as potential biases stemming from the training data — and strategies for mitigation is important to ensure responsible development and application of this powerful technology.

More visual insights#

More on figures

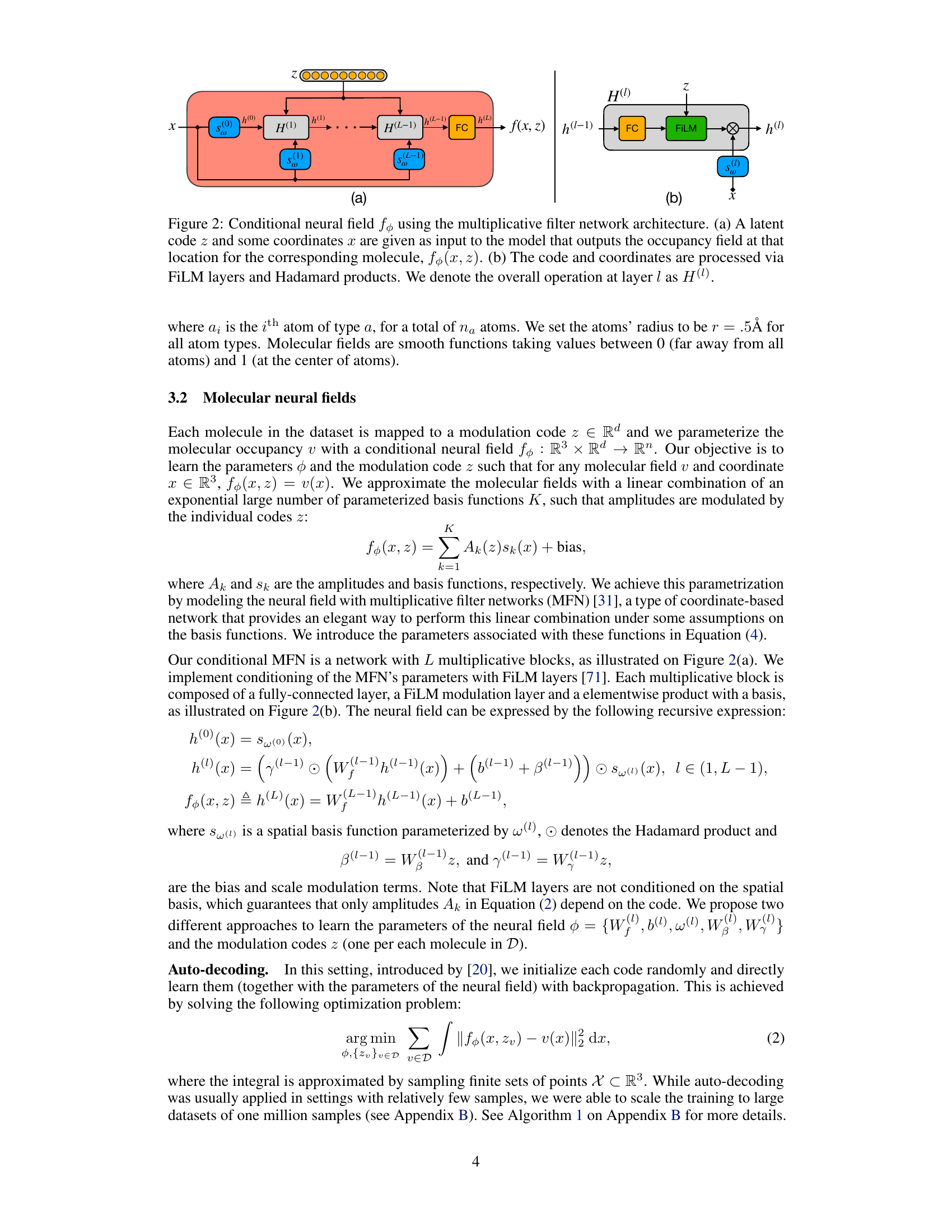

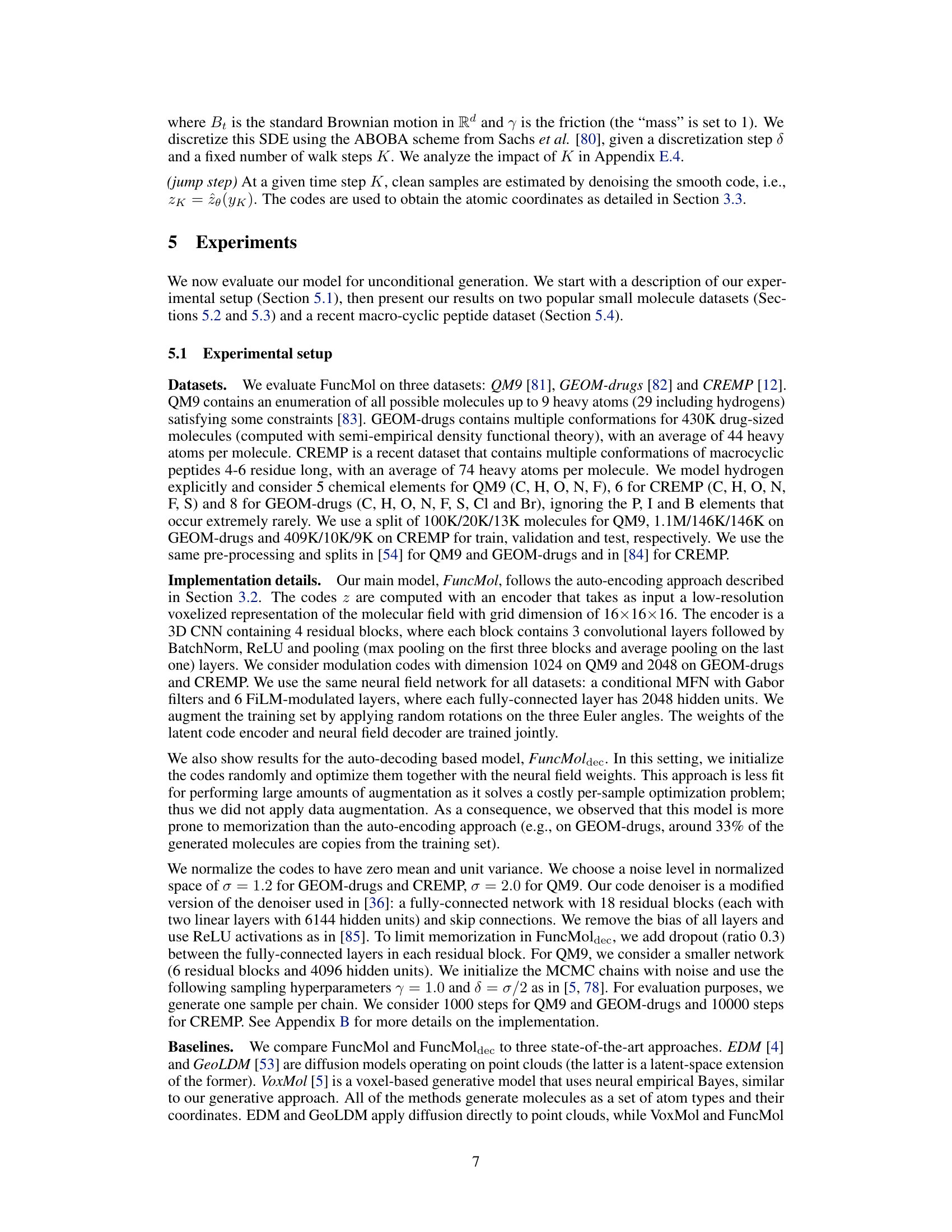

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of the conditional neural field used in FuncMol. Panel (a) depicts the overall flow, where a latent code z and 3D coordinates x are input, and the occupancy field at x is output. Panel (b) zooms in on a single multiplicative block, showing the processing steps involving FiLM (FiLM layers) and elementwise multiplication (Hadamard product) within each layer.

read the caption

Figure 2: Conditional neural field fθ using the multiplicative filter network architecture. (a) A latent code z and some coordinates x are given as input to the model that outputs the occupancy field at that location for the corresponding molecule, fθ(x, z). (b) The code and coordinates are processed via FiLM layers and Hadamard products. We denote the overall operation at layer l as H(l).

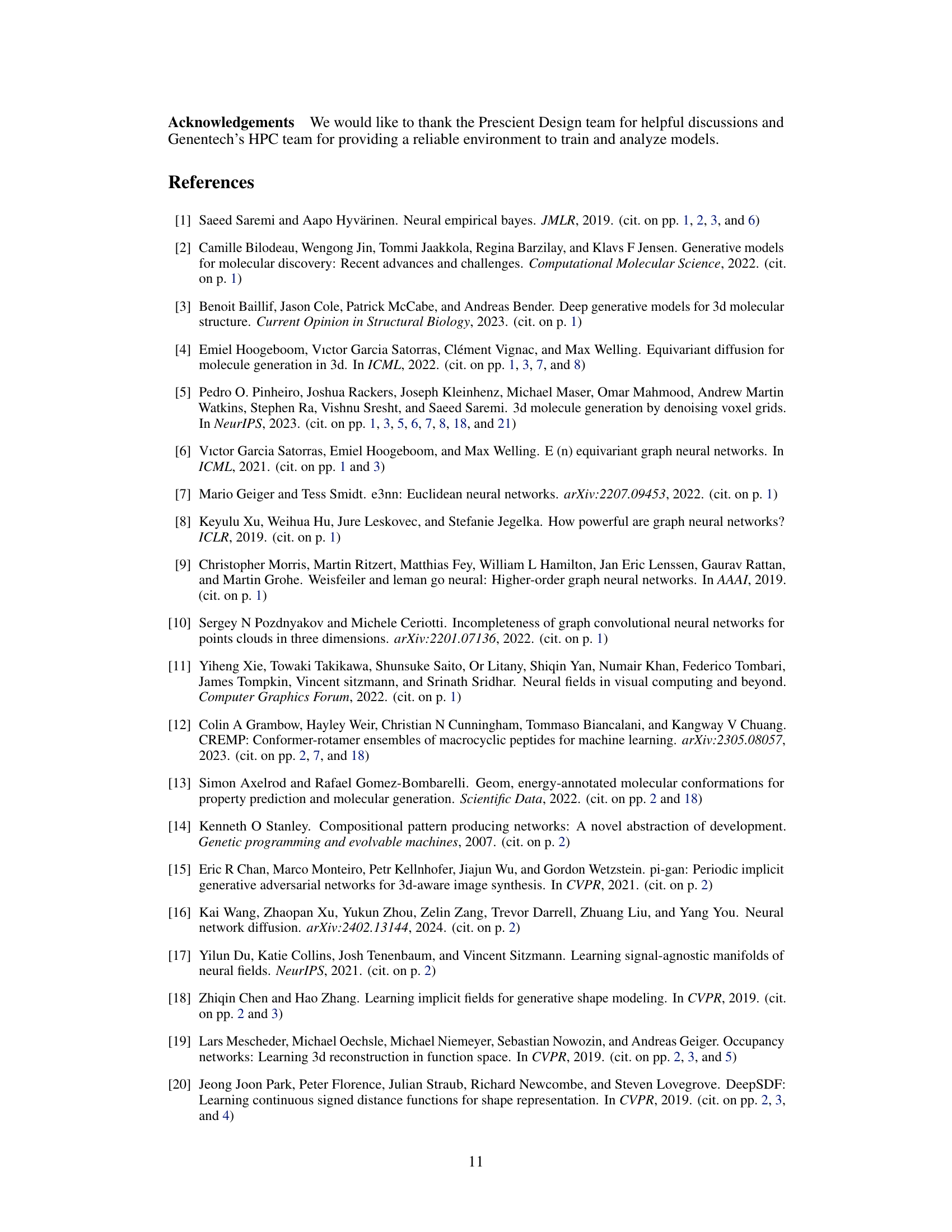

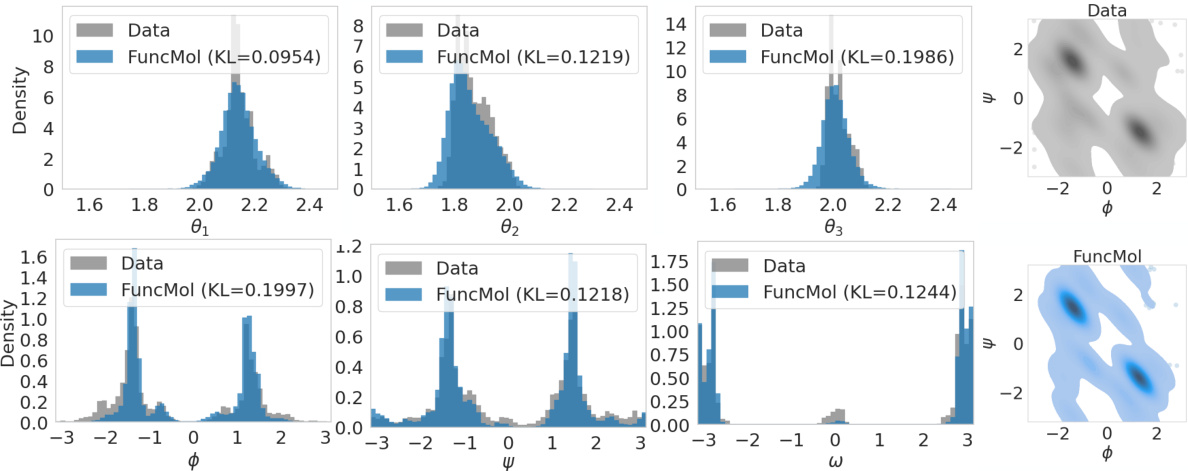

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of generated molecules from the FuncMol model against the ground truth CREMP dataset. The left side displays the comparison of bond angles (θ₁, θ₂, θ₃) and dihedral angle distributions (φ, ψ, ω) for each amino acid residue. The right side shows Ramachandran plots which represent the distribution of dihedral angles (φ, ψ) in proteins, where darker areas indicate higher densities.

read the caption

Figure 3: Qualitative evaluation on CREMP following [84]. Left: Comparison of the bond angles (θ₁, θ₂, θ₃) in each amino acid residue and dihedral distributions (φ, ψ, ω) for each residue from the reference test set (gray) and the generated samples (blue). KL divergence is calculated as KL(test || sampled). Right: Ramachandran plots [94] (colored by density where darker tones represent high density regions).

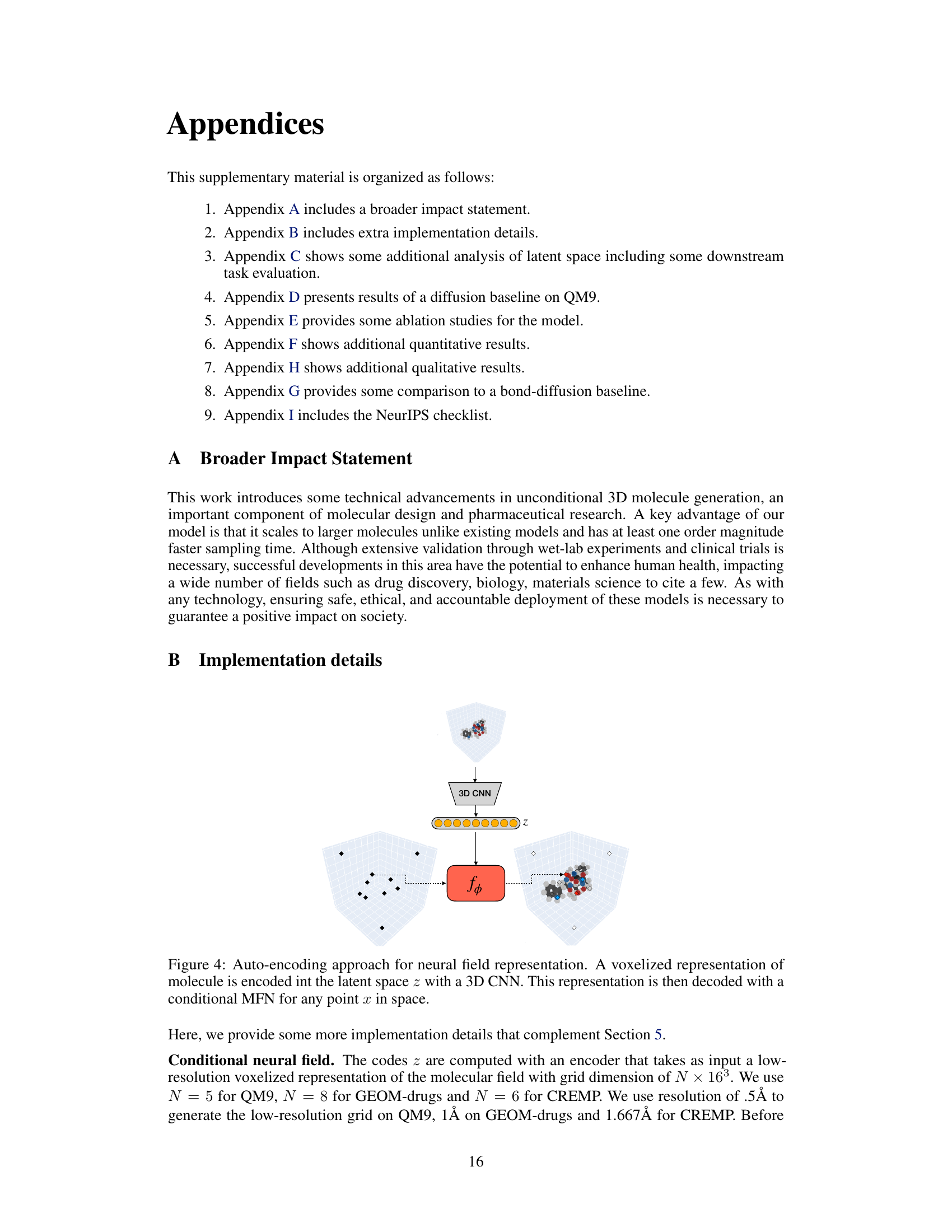

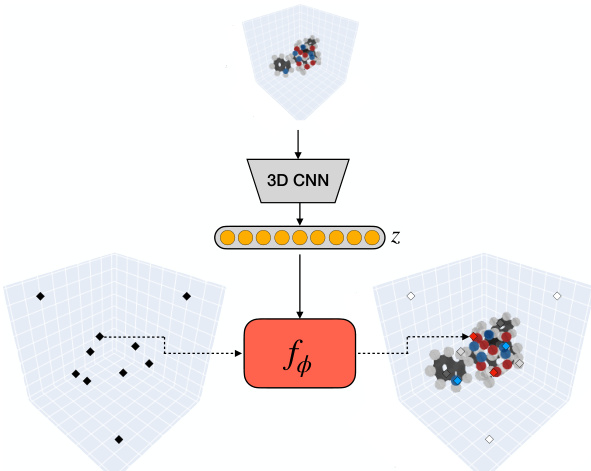

🔼 This figure illustrates the auto-encoding approach used in the FuncMol model. A 3D convolutional neural network (CNN) encodes a voxelized representation of a molecule into a low-dimensional latent code z. This code is then used as input to a conditional multiplicative filter network (MFN), which decodes the latent code back into a continuous occupancy field representing the 3D structure of the molecule. The process involves mapping 3D coordinates to atomic densities, allowing for a continuous representation of the molecule, and overcoming the limitations of discrete grid-based representations.

read the caption

Figure 4: Auto-encoding approach for neural field representation. A voxelized representation of molecule is encoded int the latent space z with a 3D CNN. This representation is then decoded with a conditional MFN for any point x in space.

🔼 This figure shows six interpolation trajectories in the latent space of molecules. Each trajectory starts and ends with a molecule from the GEOM-drugs dataset. Intermediate points along the trajectory represent interpolated latent codes, which are then decoded back into molecules using the FuncMol model’s denoising process. The figure demonstrates that nearby points in latent space correspond to molecules with similar structures, showcasing the model’s ability to learn a meaningful representation of molecular similarity.

read the caption

Figure 5: Interpolation in the latent modulation space for different pairs of molecules from GEOM-drugs. Each interpolated codes is protected back to the learned manifold of molecules via a noise/denoise operation. FuncMol produces semantically meaningful patterns in the interpolated space and we observe that molecules close in latent space share similar structure.

🔼 This figure shows six interpolation trajectories in the latent modulation space of the FuncMol model. Each trajectory connects two molecules from the GEOM-drugs dataset. Intermediate points along each trajectory represent interpolated modulation codes. These codes are then decoded back into molecular structures using the model’s denoising process. The figure demonstrates that nearby molecules in the latent space tend to have similar structures, suggesting the latent space encodes meaningful chemical information.

read the caption

Figure 5: Interpolation in the latent modulation space for different pairs of molecules from GEOM-drugs. Each interpolated codes is protected back to the learned manifold of molecules via a noise/denoise operation. FuncMol produces semantically meaningful patterns in the interpolated space and we observe that molecules close in latent space share similar structure.

🔼 This figure shows the t-SNE plots of the latent modulation codes for QM9 molecules. For each of four molecular properties (heat capacity, internal energy, isotropic polarization, and dipole moment), 200 molecules with high values and 200 molecules with low values were selected from the validation set. The t-SNE visualization aims to reveal clusters of molecules with similar property values in the latent space, demonstrating that the latent codes effectively capture these properties.

read the caption

Figure 6: t-SNE plots of latent modulations codes of QM9 molecules for different molecular properties. For each plot, we pick 200 molecules from validation set with high value of a property (blue) and 200 with low value (red). We show results for four properties: (a) heat capacity (Cv), (b) internal energy (U0), (c) isotropic polarization (α) and (d) dipole moment (µ).

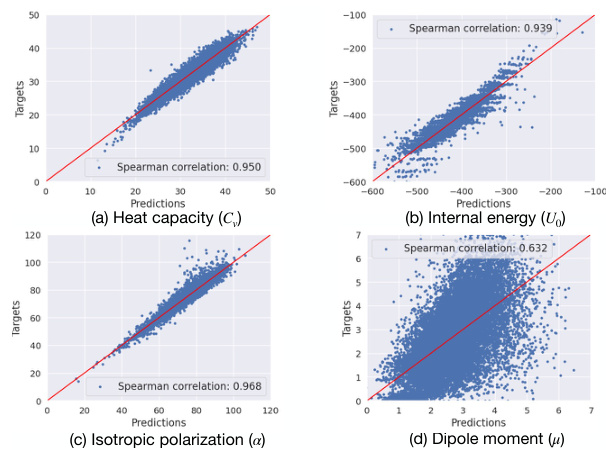

🔼 This figure demonstrates the performance of a linear regression model trained using only the learned modulation codes (latent codes) to predict four different molecular properties of the QM9 dataset. The results indicate high Spearman correlations, suggesting a strong relationship between the latent codes and these properties, despite the unsupervised nature of the code learning process.

read the caption

Figure 7: Performance of linear regression model (a.k.a linear probing) trained on modulation codes to predict molecular properties on QM9. We show the scatter plots and Spearman correlation for four different properties: (a) heat capacity (Cv), (b) internal energy (Uo), (c) isotropic polarization (a) and (d) dipole moment (μ).

🔼 This figure shows the impact of adding Gaussian noise to the latent codes on the quality of the generated molecules. The plots display the average stable molecule percentage and bond angle Wasserstein distance (W1) for different noise levels (σ) on both the GEOM-drugs and QM9 datasets. The results demonstrate the robustness of the model’s latent code representation to noise.

read the caption

Figure 8: Ablation: code robustness to noise on GEOM-drugs (blue) and QM9 (red). Stable molecule (a) and bond angle distance (b) metrics as we increasingly add noise to the codes. Metrics are computed with 4000 generated samples on validation reference set.

🔼 This figure shows the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the strain energy for molecules generated by different models on the GEOM-drugs dataset. The strain energy, calculated using the Universal Force Field (UFF), measures the difference between the energy of a generated molecule’s pose and its relaxed pose. A lower strain energy indicates a more stable and realistic conformation. The CDF plots allow comparison of the models’ ability to generate molecules with realistic strain energy distributions, reflecting their ability to produce stable, chemically plausible structures. The reference line represents the true distribution of strain energies from the dataset, while the other lines represent the distributions of strain energies for molecules generated by each model (EDM, GeoLDM, VoxMol, FuncMol).

read the caption

Figure 9: Cumulative distribution function of strain energy of generated molecules on GEOM-drugs based on 10000 molecules.

🔼 This figure compares the distributions of the number of fragments, ring size, and number of atoms per molecule between generated molecules from different models and a reference dataset. It provides a visual representation of how well each generative model is able to capture the structural properties of real-world molecules, in terms of their size and complexity.

read the caption

Figure 10: Histograms (over 10000 samples) showing (first row) distribution of number of fragments, (second) distribution of ring size, and (third) distribution of number of atoms per molecule.

🔼 The figure shows the process of FuncMol. First, a conditional neural field encodes a molecular field into a low-dimensional latent code. Second, FuncMol performs sampling in the latent space using Langevin MCMC with a learned score function. Finally, the sampled codes are decoded back into molecules.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) a conditional neural field encodes a molecular field v into a low dimensional latent code z. (b) using a learned score function ge, FuncMol performs sampling in latent space via Langevin MCMC. These codes are decoded back into molecules.

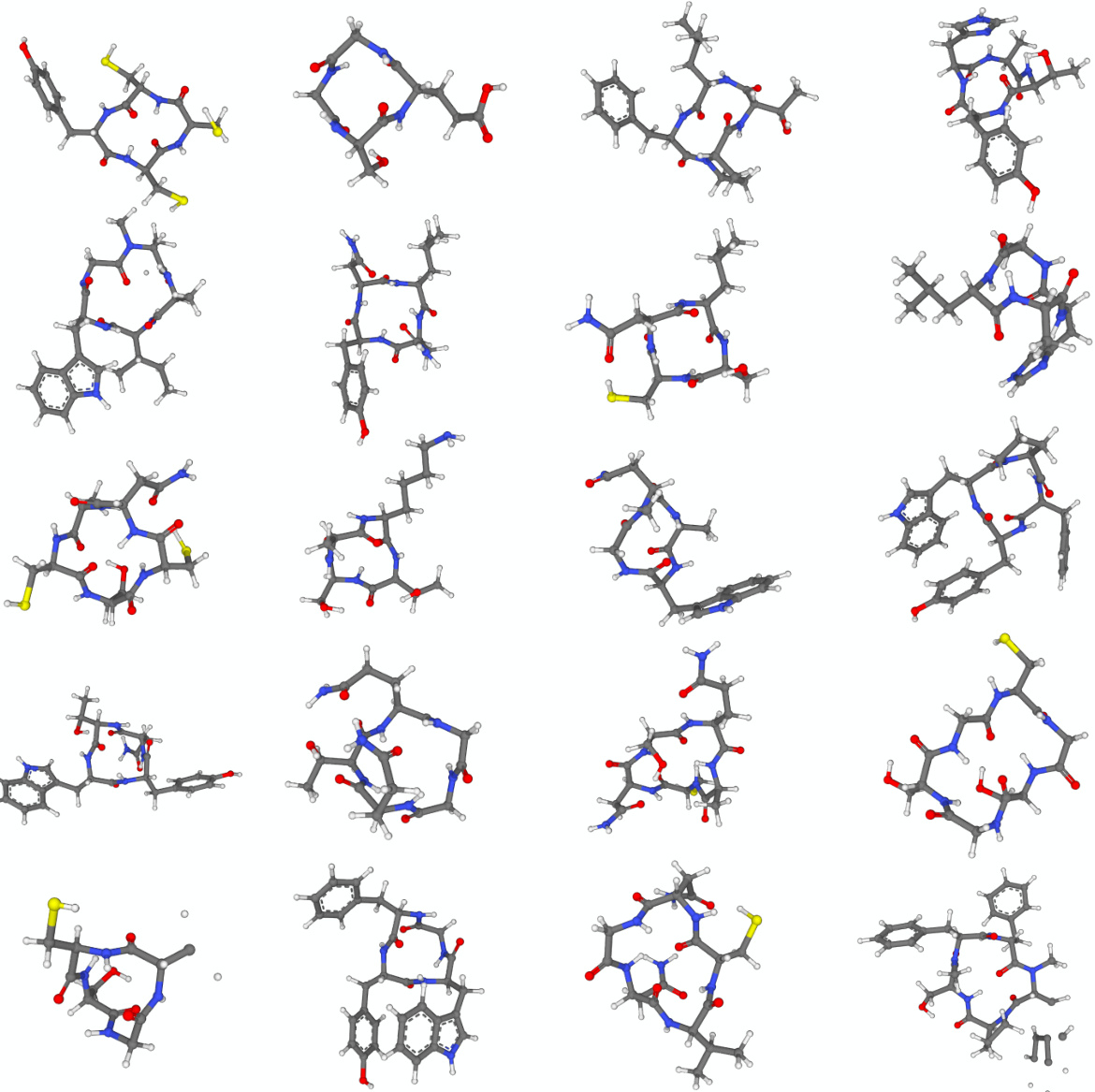

🔼 This figure displays 16 examples of molecules generated by the FuncMol model, which was trained on the GEOM-drugs dataset. Each molecule is depicted in 3D, showcasing its spatial structure. The variety in molecular structures highlights the model’s ability to generate diverse drug-like molecules. The figure serves as a qualitative assessment of FuncMol’s performance, illustrating its capacity to produce chemically plausible and structurally varied molecules.

read the caption

Figure 12: Generated samples from FuncMol trained on GEOM-drugs.

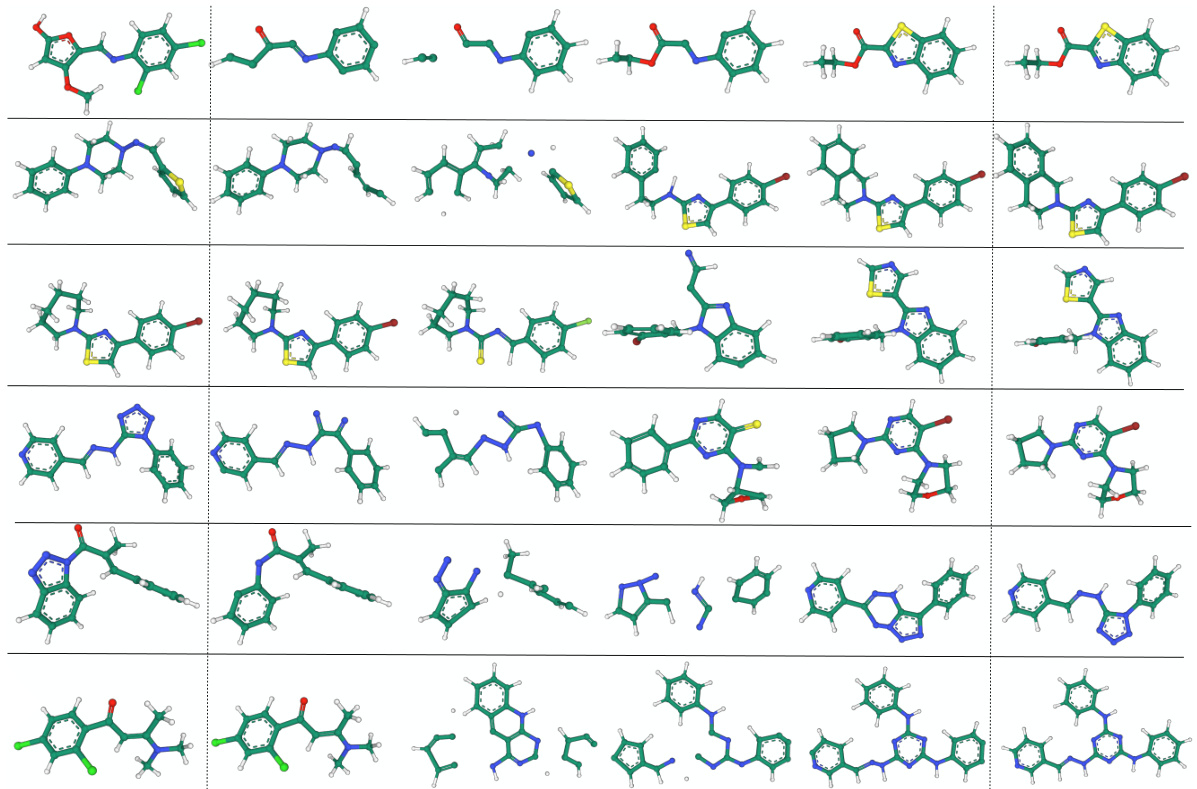

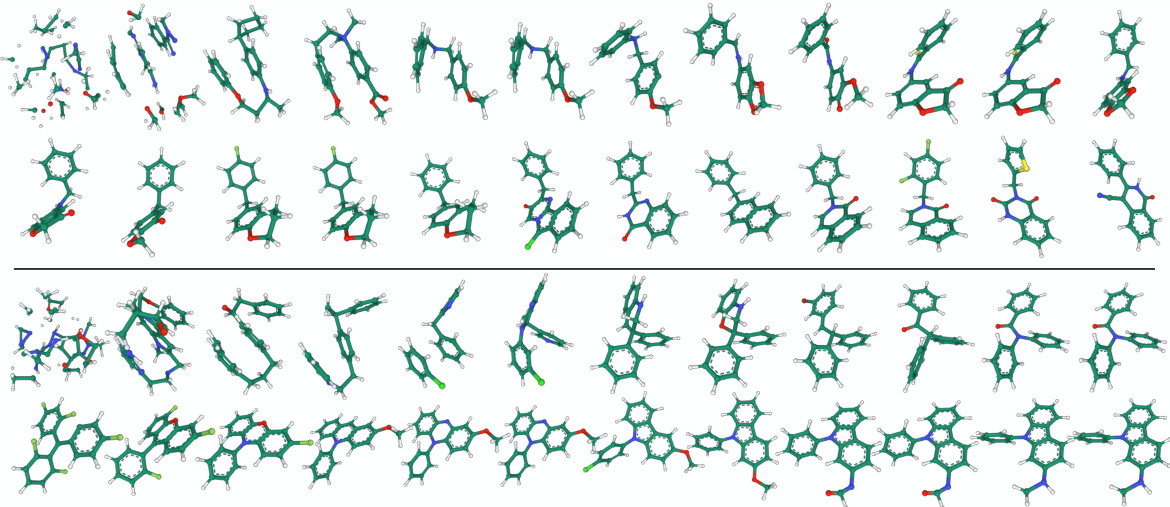

🔼 This figure shows 16 example molecules generated by the FuncMol model trained on the CREMP dataset. CREMP is a dataset of macrocyclic peptides which are larger and more complex than the molecules in other datasets used in the paper. The figure demonstrates the ability of FuncMol to generate diverse and complex molecules.

read the caption

Figure 13: Generated samples from FuncMol trained on CREMP.

🔼 This figure shows the overall process of FuncMol. (a) shows that a conditional neural field takes a molecular field as input and encodes it into a low-dimensional latent code z. (b) illustrates how FuncMol uses a learned score function and Langevin MCMC sampling in the latent space to generate new molecules. These latent codes are then decoded back into 3D molecular structures.

read the caption

Figure 1: (a) a conditional neural field encodes a molecular field v into a low dimensional latent code z. (b) using a learned score function ge, FuncMol performs sampling in latent space via Langevin MCMC. These codes are decoded back into molecules.

More on tables

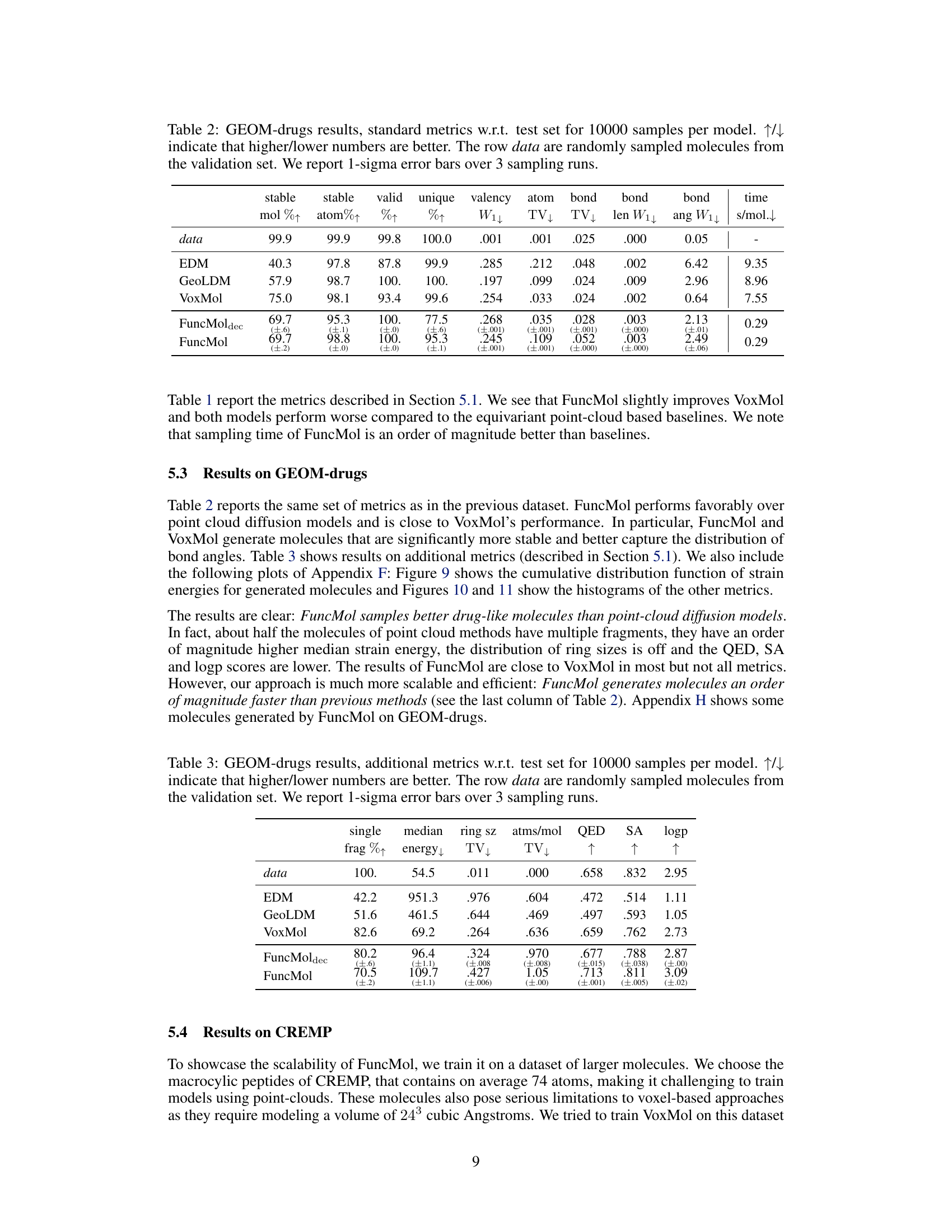

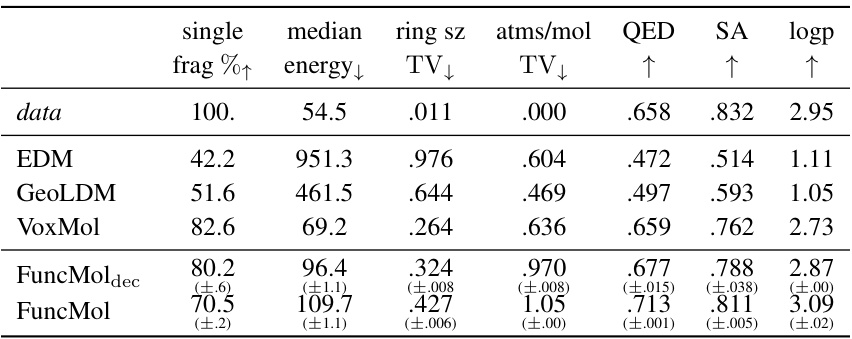

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of the GEOM-drugs dataset using various metrics. It compares the performance of FuncMol and FuncMoldec against three other state-of-the-art baselines (EDM, GeoLDM, VoxMol) in terms of generating realistic and stable molecules. The metrics assess aspects like molecule stability, validity, uniqueness, valency, atom and bond distribution, bond length and angle distributions, and sampling time. Higher/lower values indicate better performance depending on the metric.

read the caption

Table 2: GEOM-drugs results, standard metrics w.r.t. test set for 10000 samples per model. ↑↓ indicate that higher/lower numbers are better. The row data are randomly sampled molecules from the validation set. We report 1-sigma error bars over 3 sampling runs.

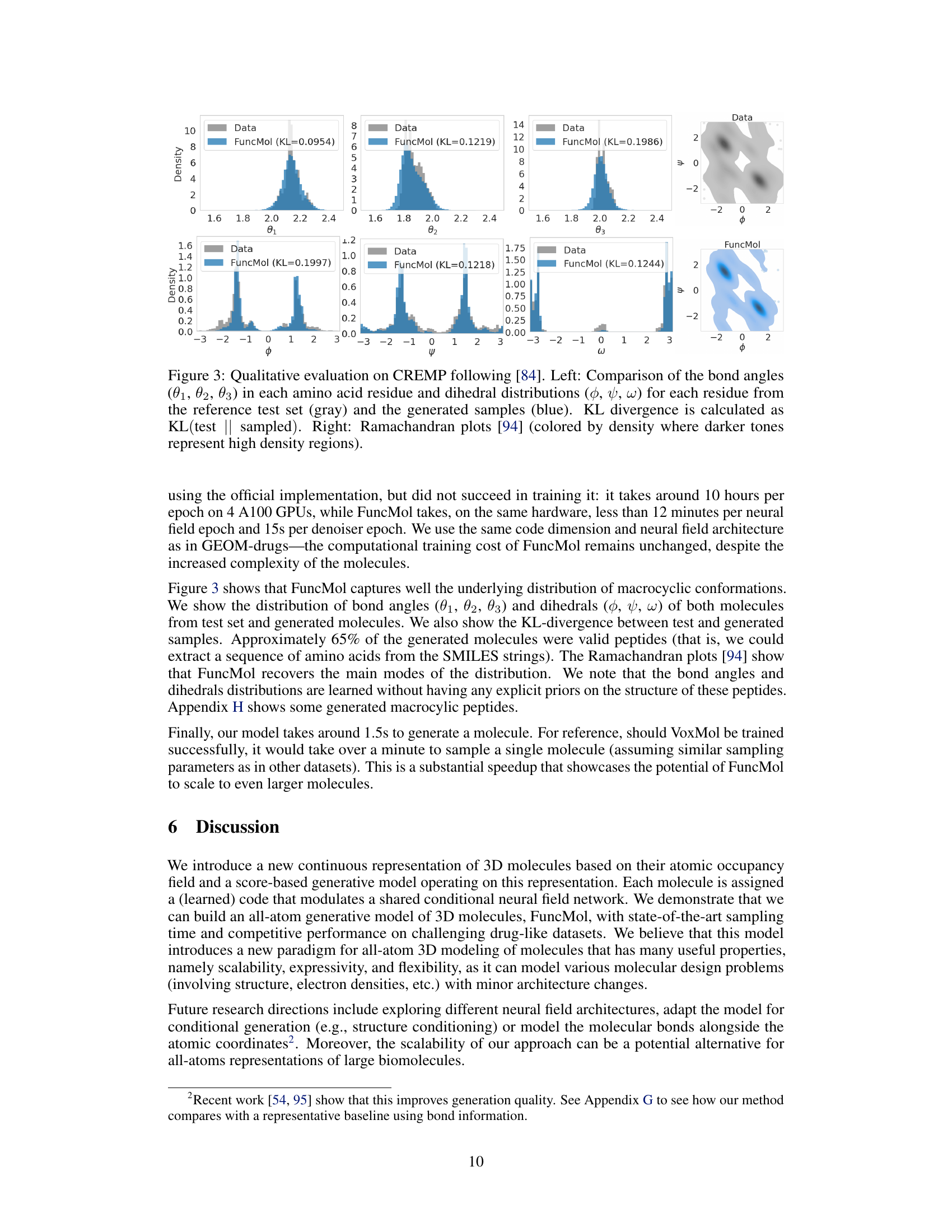

🔼 This table presents the results of additional metrics used to evaluate the quality of generated molecules on the GEOM-drugs dataset. These metrics assess various aspects of molecular properties, including stability, drug-likeness, and structural features. The table compares the performance of FuncMol against other state-of-the-art methods, indicating which model performs better based on higher or lower values for each metric. One-sigma error bars are included, showing the variability across three separate sampling runs.

read the caption

Table 3: GEOM-drugs results, additional metrics w.r.t. test set for 10000 samples per model. ↑↓ indicate that higher/lower numbers are better. The row data are randomly sampled molecules from the validation set. We report 1-sigma error bars over 3 sampling runs.

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of the GEOM-drugs dataset using various metrics to evaluate the performance of different molecule generation models. The metrics assess various aspects of the generated molecules, including stability, validity, uniqueness, valency, atom and bond distributions, and sampling time. Higher values are generally better for most metrics, indicated by the upward-pointing arrows; exceptions are noted with downward-pointing arrows. The standard deviation is also included for better comparison.

read the caption

Table 2: GEOM-drugs results, standard metrics w.r.t. test set for 10000 samples per model. ↑↓ indicate that higher/lower numbers are better. The row data are randomly sampled molecules from the validation set. We report 1-sigma error bars over 3 sampling runs.

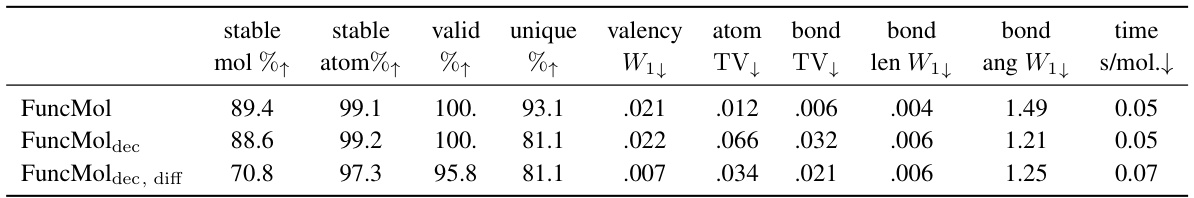

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of the QM9 dataset for different models, including the proposed FuncMol model and several baselines. The metrics used assess various aspects of molecular generation quality, such as the stability of generated molecules (stable mol%, stable atom%), their validity according to cheminformatics standards (valid %), uniqueness (unique %), adherence to valency rules (valency), and the distribution of atom types (atom TV), bond types (bond TV), bond lengths (len W11), and bond angles (ang W11). Sampling time per molecule is also reported. Higher/lower numbers are better depending on the metric (indicated by ↑↓). Error bars represent one standard deviation across three independent sampling runs.

read the caption

Table 1: QM9 results w.r.t. test set for 10000 samples per model. ↑↓ indicate that higher/lower numbers are better. The row data are randomly sampled molecules from the validation set. We report 1-sigma error bars over 3 sampling runs.

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of the QM9 dataset for four different models: EDM, GeoLDM, VoxMol, and FuncMol. Each model generated 10,000 molecules, and several metrics were used to evaluate the quality of these generated molecules. The metrics assess various aspects of the molecules’ validity, such as stability (of both molecules and atoms), uniqueness, adherence to valency rules, and the distribution of atom and bond types. Additionally, the table includes the average time taken to generate each molecule. The results show FuncMol achieving competitive performance, although not superior to all baselines.

read the caption

Table 1: QM9 results w.r.t. test set for 10000 samples per model. ↑↓ indicate that higher/lower numbers are better. The row data are randomly sampled molecules from the validation set. We report 1-sigma error bars over 3 sampling runs.

🔼 This table shows the mean squared error (MSE) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) for the reconstruction of molecular fields using a conditional multiplicative filter network (MFN) architecture and learned codes. Lower MSE indicates better reconstruction quality, while higher PSNR indicates better reconstruction quality. The results are shown for three different datasets: GEOM-drugs, CREMP, and QM9.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation: field reconstruction (whole training set).

🔼 This table shows the results of molecule reconstruction experiments on a subset of 4000 molecules from the GEOM-drugs and QM9 datasets. It compares the performance of molecule reconstruction from the original data, from latent codes (the model’s compressed representation), and from a voxelized representation of the atomic density field. The metrics evaluated include the percentage of stable molecules and atoms, the percentage of valid molecules, uniqueness, and Wasserstein distances for various molecular properties (valency, atom types, bond lengths, bond angles). The results demonstrate that the model’s latent code representation produces significantly better reconstructions than the voxelized representation.

read the caption

Table 6: Ablation: molecule reconstruction (sample of 4k).

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the effect of continuous coordinate refinement on the reconstruction performance of the model. It compares the results of using continuous refinement against the discrete refinement method from prior work. The metrics evaluated include the percentage of stable molecules and atoms, validity, valency, atom bond length and angle Wasserstein distances, and atom and bond type total variation distances. The results demonstrate that the continuous refinement significantly improves the quality of the reconstructed molecules.

read the caption

Table 7: Ablation: continuous refinement improvement on code reconstruction performance. Metrics computed with 4000 generated samples on validation reference set.

🔼 This table presents an ablation study on the impact of the number of walk steps (K) in the walk-jump sampling algorithm of the FuncMol model. The study was conducted on the GEOM-drugs dataset using 2000 generated samples. The table shows how various metrics related to molecule generation quality change with increasing values of K. These metrics include the percentage of stable molecules and atoms, uniqueness, valency, and bond statistics.

read the caption

Table 8: Ablation on the number of walk steps K on GEOM-drugs. Metrics computed with 2000 generated samples on test reference set.

🔼 This table shows the ablation study on the impact of resolution on sampling quality for the GEOM-drugs dataset. The metrics (stable molecule percentage, stable atom percentage, valid molecule percentage, unique molecule percentage, valency Wasserstein distance, atom type total variation, bond type total variation, bond length Wasserstein distance, bond angle Wasserstein distance, and average sampling time per molecule) are computed using 2000 generated samples on the test set for three different resolutions: 0.167 Å, 0.25 Å, and 0.5 Å. The results demonstrate the trade-off between sampling time and quality at different resolutions.

read the caption

Table 9: Ablation on the impact of resolution on sampling quality on GEOM-drugs. Metrics computed with 2000 generated samples on test reference set.

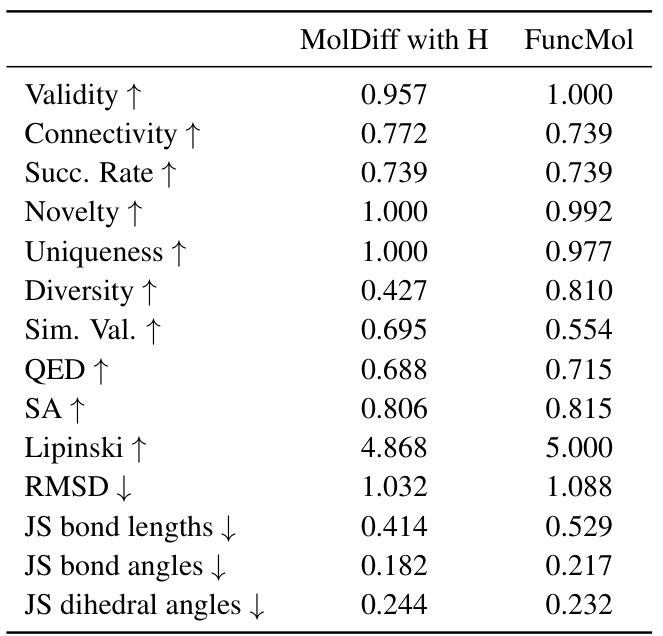

🔼 This table compares the performance of FuncMol with MolDiff, a bond-diffusion model. The comparison focuses on various metrics assessing the quality of generated molecules, including validity, connectivity, novelty, uniqueness, diversity, similarity to training set molecules, drug-likeness scores (QED, SA, Lipinski), root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), and Jensen-Shannon divergence of bond lengths, angles, and dihedral angles. It highlights the competitive performance of FuncMol despite not explicitly using bond information during training.

read the caption

Table 10: Comparison of MolDiff with H and FuncMol

Full paper#