TL;DR#

Open-world object detection (OWOD) is a challenging computer vision task, where models must identify both known and previously unseen objects. Existing OWOD methods mainly focus on identifying unknown objects, neglecting to explore the underlying reasons behind the model’s predictions. This lack of understanding hinders the development of more robust and reliable systems. The current approaches often rely on heuristics and lack a deep understanding of the decision-making process within the model.

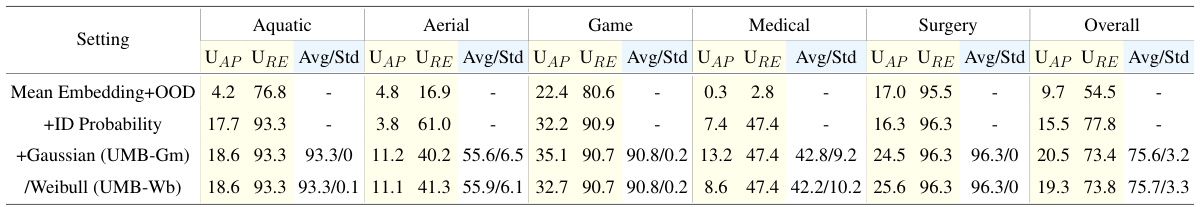

The researchers propose a novel model, UMB, which models textual attributes and positive sample probabilities to improve the understanding of the prediction process, particularly for unknown objects. UMB leverages the power of large language models to generate attributes, and through a probabilistic mixture model, determines whether an object should be classified as unknown based on empirical, in-distribution, and out-of-distribution probabilities. This approach not only identifies unknown objects with higher accuracy than prior art, but also provides additional information about the object’s similarity to known classes, improving the understanding of the model’s predictions and achieving state-of-the-art results on the RWD benchmark.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the limitations of existing open-world object detection methods by focusing on understanding model behavior rather than just detection accuracy. It presents a novel framework, UMB, that not only surpasses the current state-of-the-art but also offers valuable insights into how models handle unknown objects. This understanding can significantly contribute to developing more robust and reliable open-world object detection systems. Furthermore, the open-sourcing of code promotes community collaboration and accelerates further research in this important area. Its findings are valuable for developing more accurate and interpretable models for real-world object detection.

Visual Insights#

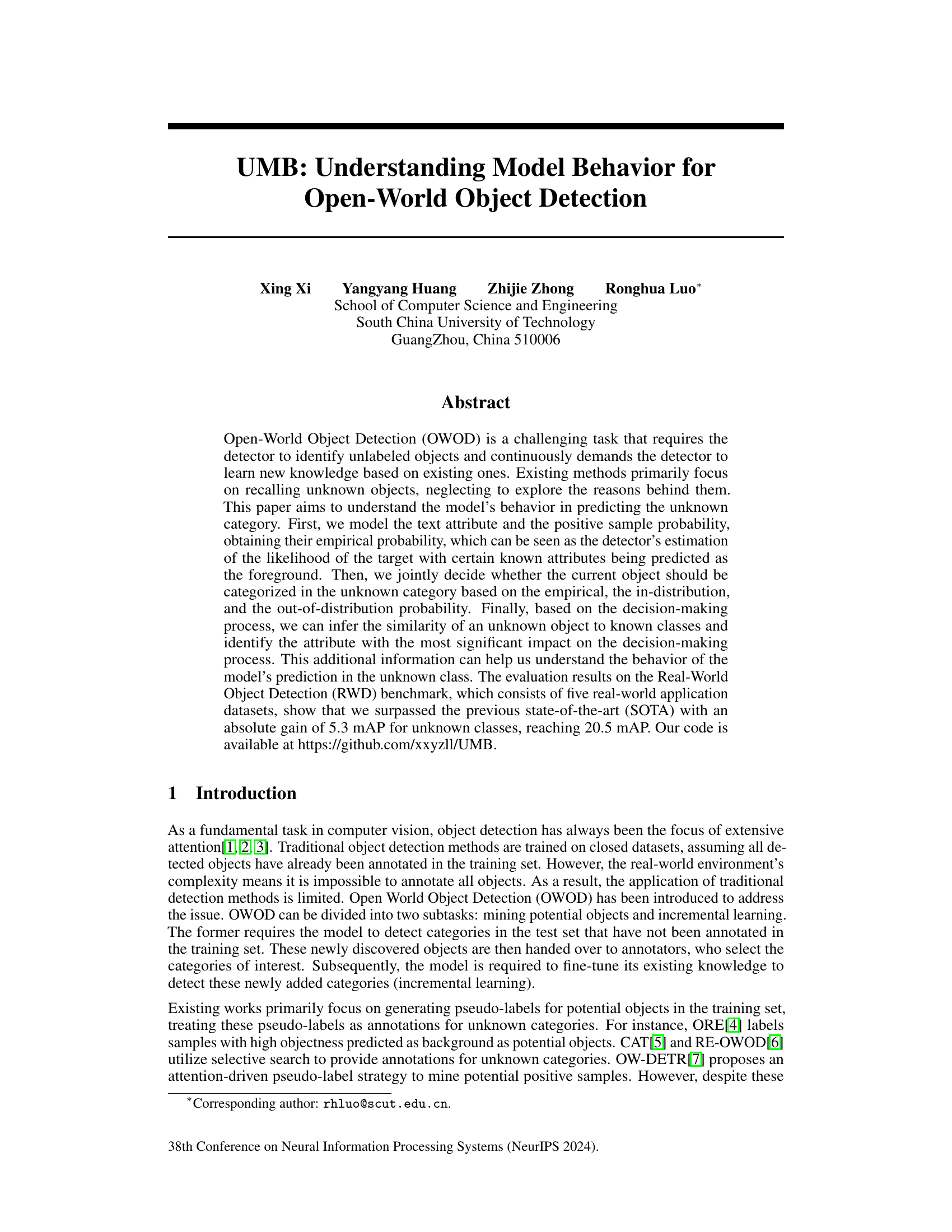

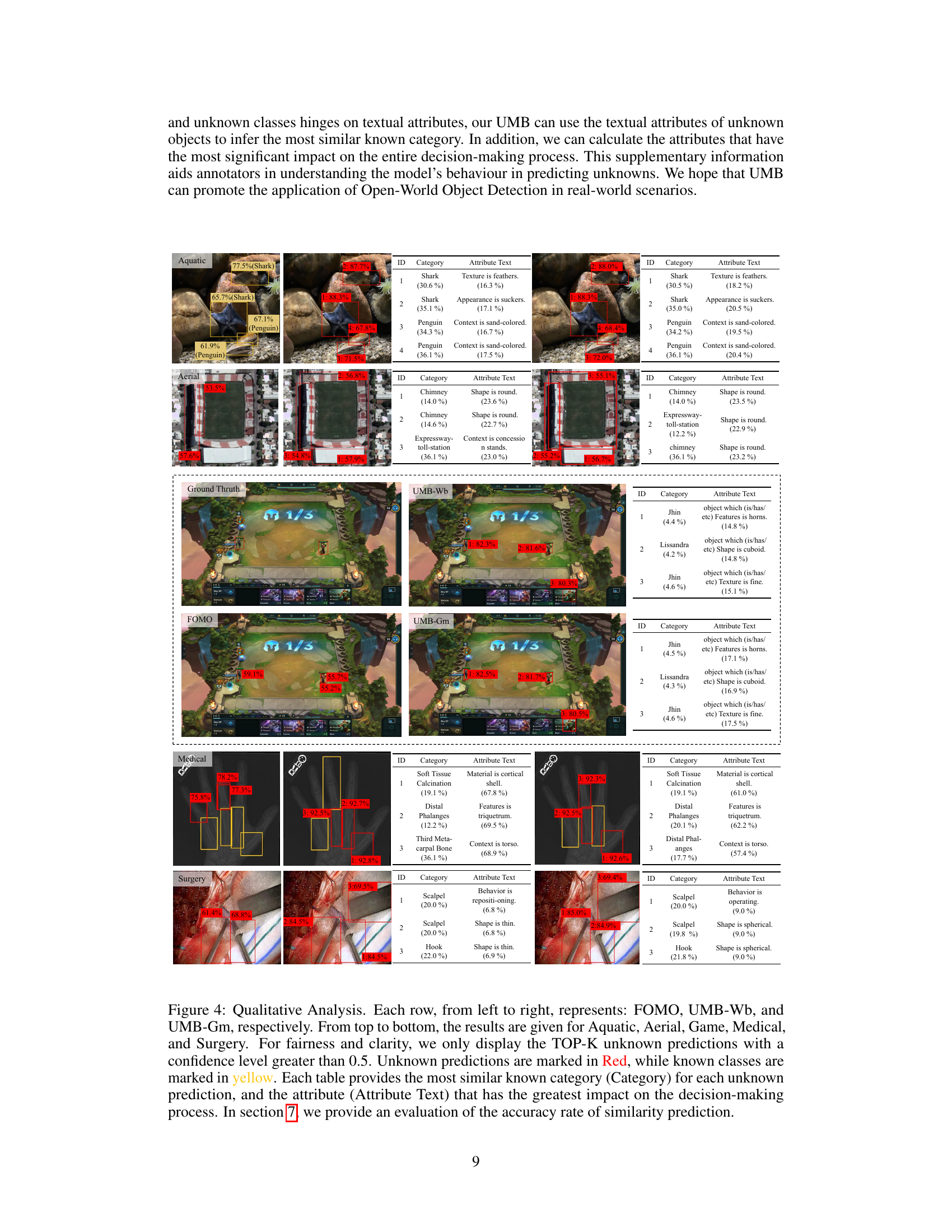

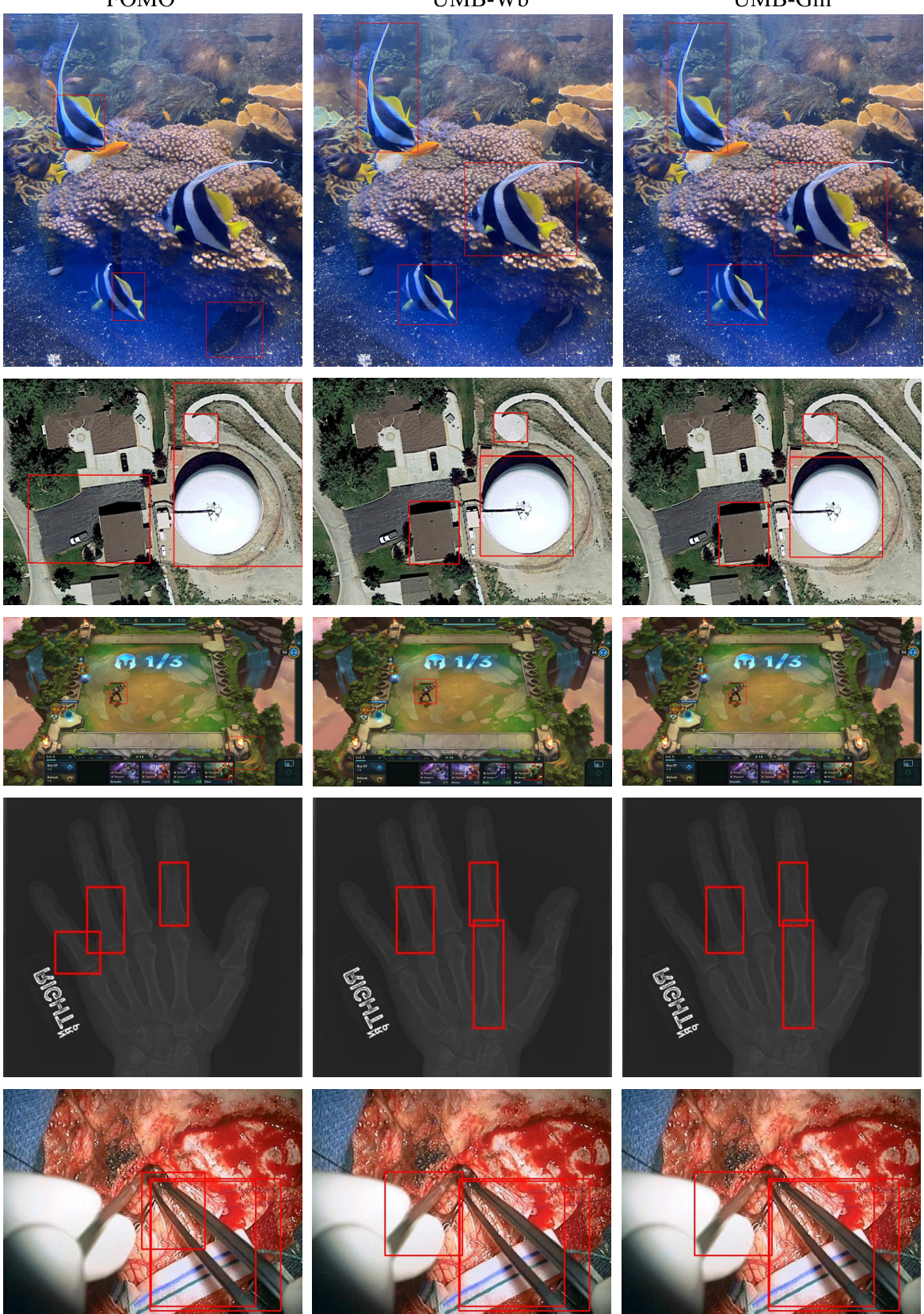

🔼 This figure compares the proposed method UMB with other existing Open-World Object Detection (OWOD) methods. The left side shows that traditional OWOD methods only identify unknown objects without explaining the model’s reasoning behind the classification. The right side illustrates UMB, which not only detects unknown objects but also provides insights into why the model classified them as unknown, showing the model’s decision-making process and connecting the unknown object to known classes based on attribute similarity. This additional information helps annotators understand the model’s predictions better.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustration of our UMB and other methods. Previous OWOD methods only detected unknown objects (left), while our method further understands the model's behaviour (right).

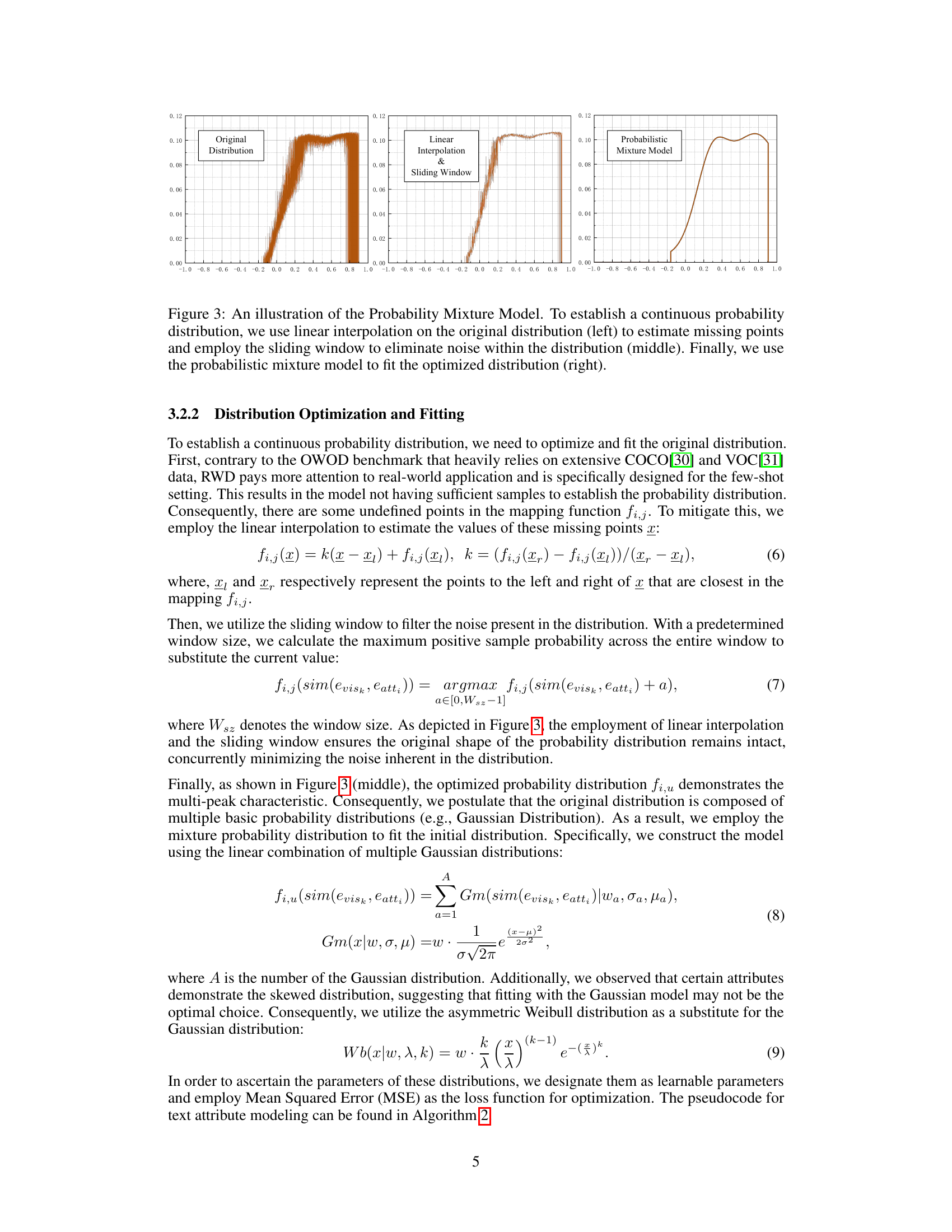

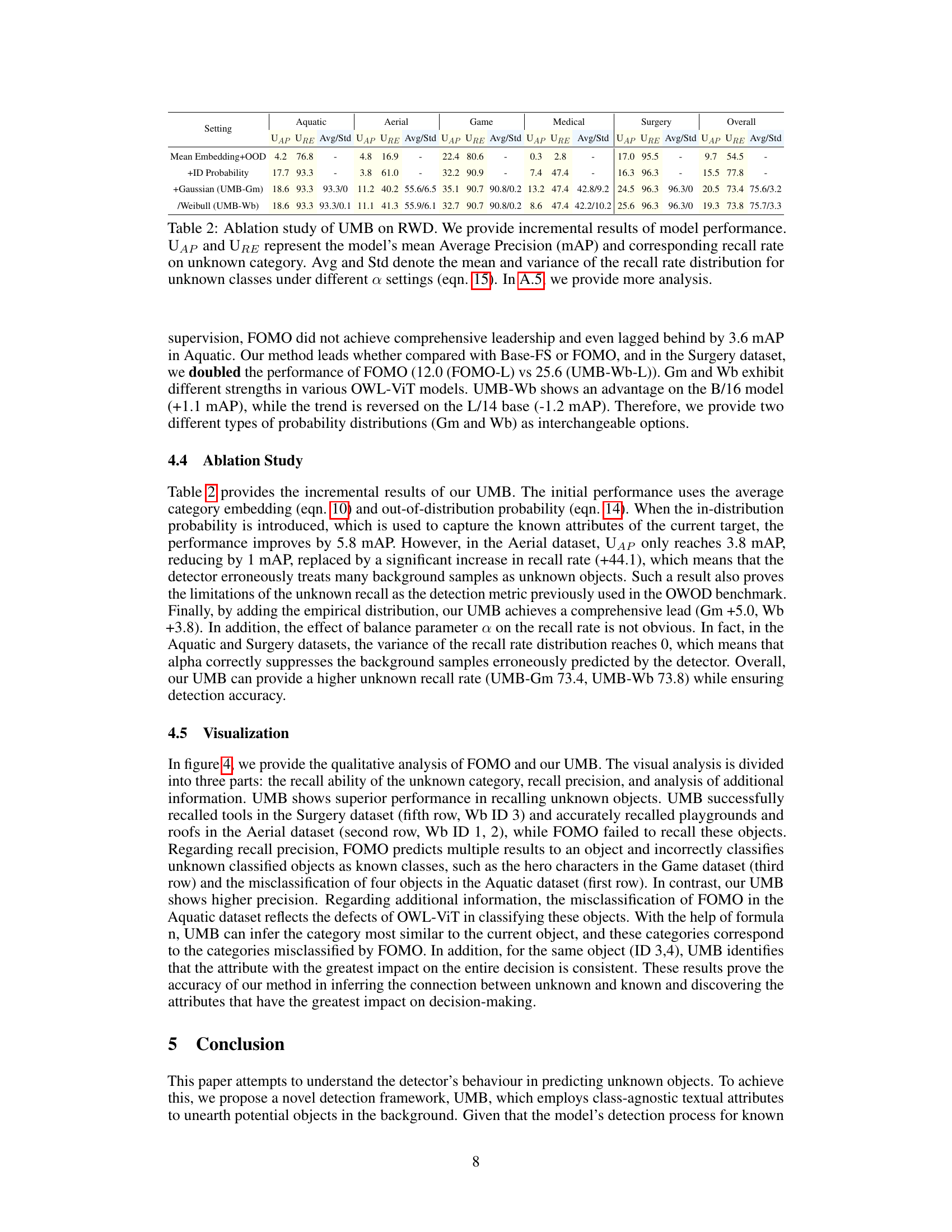

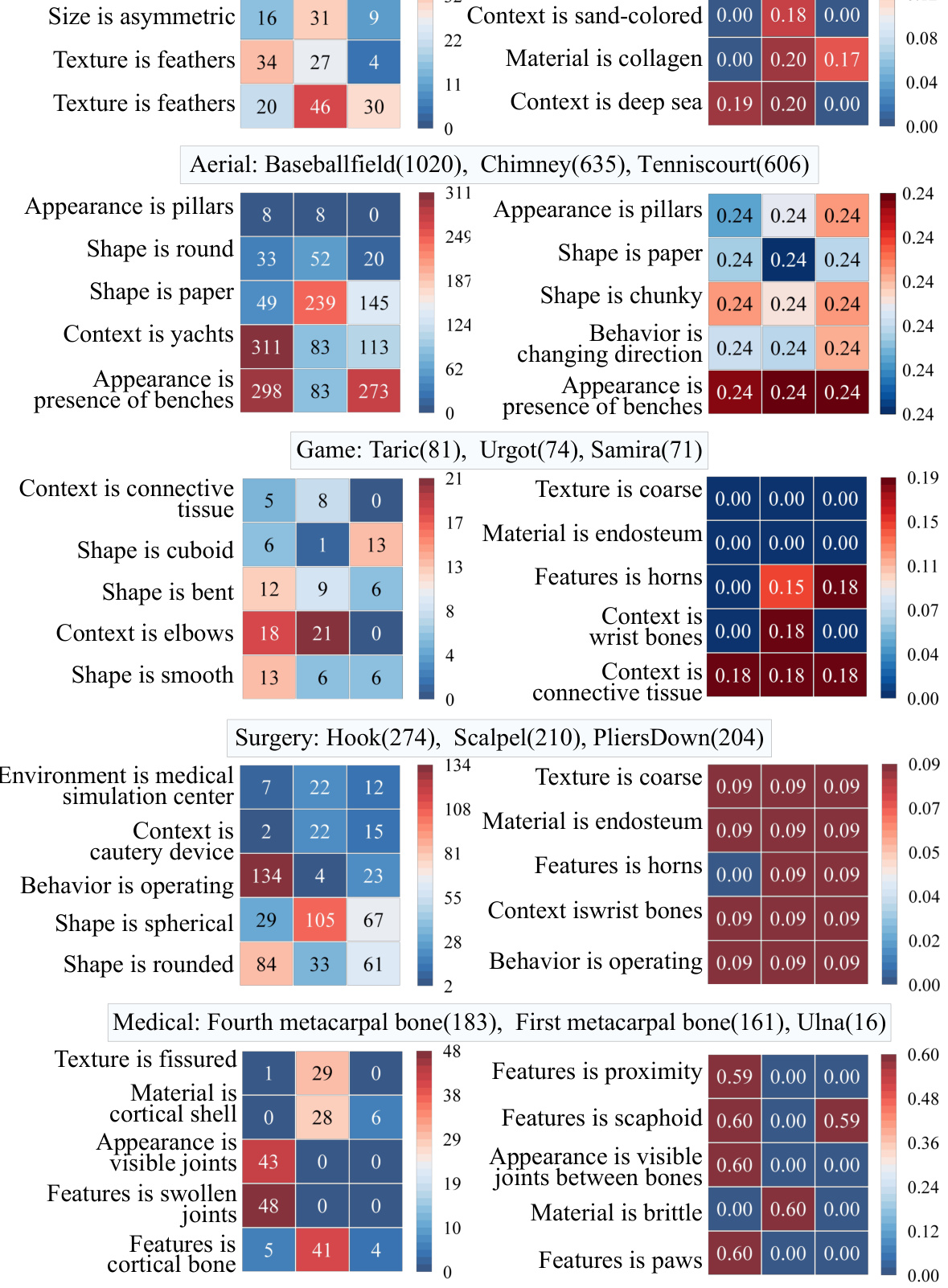

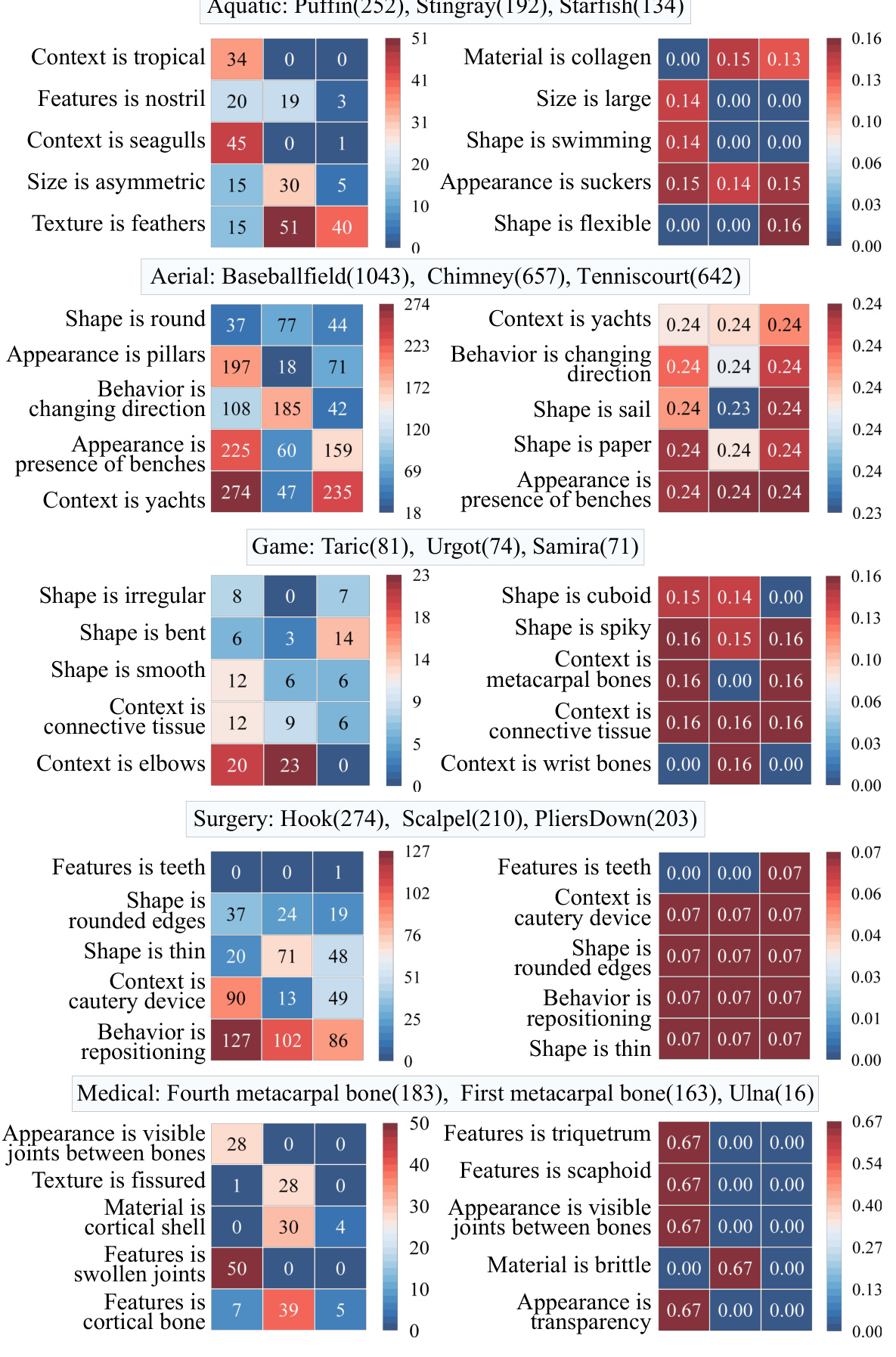

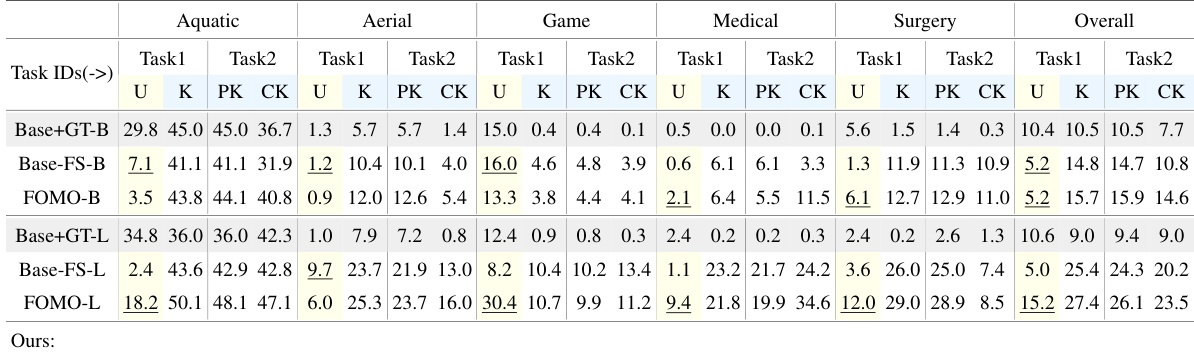

🔼 This table compares the proposed UMB method with state-of-the-art (SOTA) open-vocabulary object detection methods on the Real-World Object Detection (RWD) benchmark. It shows the performance (in terms of mean Average Precision (mAP) and recall rate) for both known and unknown classes on five real-world datasets. Different model sizes (B/14 and L/14) and probability distribution fitting methods (Weibull and Gaussian) are compared, highlighting the superior performance of the proposed UMB method.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with previous SOTA methods on the RWD benchmark. Base+GT represents the standard OVC setting using all class names including unknown label. Base-FS indicates the baseline of fine-tuning the benchmark model with the same supervision received[27]. Band L respectively represent two different sizes of the OWL-ViT model, B/14 and L/14. U, K, PK, and CK respectively represent unknown categories, known categories, previously known categories, and currently introduced categories. Overall indicates the average performance of the model on 5 datasets. Wb and Gm respectively represent use of Weibull and Gaussian distribution during the fitting stage.

In-depth insights#

OWOD Behavior Modeling#

Open-World Object Detection (OWOD) behavior modeling is a crucial area of research focusing on understanding how OWOD models make predictions, especially for unknown objects. Effective OWOD models should not only identify novel objects but also explain their classifications. Current methods often lack this explanatory power, limiting their usability and trustworthiness. A promising approach involves analyzing model internal states (e.g., feature representations, attention weights) to understand the decision-making process. By correlating these internal states with object attributes, researchers can gain insights into what aspects of an object lead to its classification (known or unknown). This would enable improved model design, enhanced transparency, and increased confidence in model predictions. Furthermore, understanding the model’s limitations is critical. Analyzing failure cases and identifying systematic biases can improve model robustness and guide the development of more reliable OWOD systems. Ultimately, behavior modeling in OWOD aims to transition from simple detection to a more profound understanding of the model’s reasoning and its implications for real-world applications.

Attribute-driven OWOD#

Attribute-driven Open World Object Detection (OWOD) presents a novel approach to tackling the challenges of identifying and learning new object categories within open-world scenarios. The core idea revolves around leveraging object attributes, such as shape, color, texture, and context, to model and understand the model’s behavior when encountering unknown objects. This method moves beyond simply identifying unseen objects to delving into the reasoning behind those classifications, enhancing model transparency and interpretability. By incorporating attribute information, the model can establish connections between unknown objects and known categories, even providing additional information (e.g., influential attributes) to aid human annotators. This approach is crucial for building more robust and adaptive OWOD systems, particularly in real-world applications where exhaustive annotation is impractical. The use of attributes offers a more nuanced understanding of the decision-making process compared to solely relying on object detection scores or heuristic methods. Furthermore, an attribute-driven strategy potentially facilitates more efficient incremental learning. However, challenges remain in effectively modeling attribute interactions and handling noisy or ambiguous attribute data. Addressing these challenges could lead to significant advancements in OWOD, improving the model’s ability to generalize to new objects and reducing human annotation burden.

RWD Benchmark Results#

The RWD benchmark results section would ideally present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed UMB model’s performance against existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) open-world object detection methods. It should show the model’s performance across various metrics, including mean Average Precision (mAP) for both known and unknown classes, and potentially recall and precision rates. Crucially, the results need to demonstrate a clear improvement over SOTA, particularly regarding the detection of unknown objects, which is a key challenge in open-world scenarios. The analysis should detail the performance across different datasets within the RWD benchmark, highlighting any variations or strengths/weaknesses. The discussion must go beyond simple metrics; it should provide insights into the model’s behavior and explain why it performs well or poorly in specific datasets. Visualizations, such as tables and graphs, are essential to present the performance effectively. A qualitative analysis of selected results, potentially comparing representative examples with other models, could offer valuable insights into the model’s capabilities and limitations.

UMB Framework Analysis#

An analysis of the UMB framework would delve into its core components: text attribute modeling, which leverages textual descriptions to capture object attributes, and unknown inference, combining empirical, in-distribution, and out-of-distribution probabilities to classify unseen objects. A key aspect is its ability to infer the model’s behavior, identifying the most influential attribute in classifying unknowns and highlighting its connection to known classes. The framework’s evaluation on the RWD benchmark is critical, showcasing its performance compared to state-of-the-art methods, particularly regarding improvements in unknown object detection. Analyzing its use of LLM and its handling of probability distributions would reveal strengths and potential weaknesses, while examining its application to real-world datasets would highlight its practical implications and limitations. Overall, a comprehensive analysis would uncover its novel contributions to open-world object detection and assess its robustness and scalability.

Future OWOD Research#

Future research in Open World Object Detection (OWOD) should prioritize addressing the limitations of current methods in handling unknown objects. This includes improving the accuracy and robustness of pseudo-labeling techniques, exploring more sophisticated methods for understanding and modeling the uncertainty associated with unknown classes, and developing more efficient incremental learning strategies. A key area for investigation is developing more effective ways to integrate textual information to better understand object attributes and relationships between known and unknown categories. The focus should shift from simply detecting unknowns to deeply understanding the model’s decision-making process when encountering unseen objects. This would involve developing explainable AI techniques to provide insights into the model’s reasoning and improving the quality of feedback provided to annotators. Benchmarking and evaluation should move beyond simple metrics like recall, towards comprehensive metrics that capture the performance trade-offs between known and unknown classes. Finally, significant effort should be placed into creating more realistic and challenging OWOD datasets, reflecting the complexity and variability of real-world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

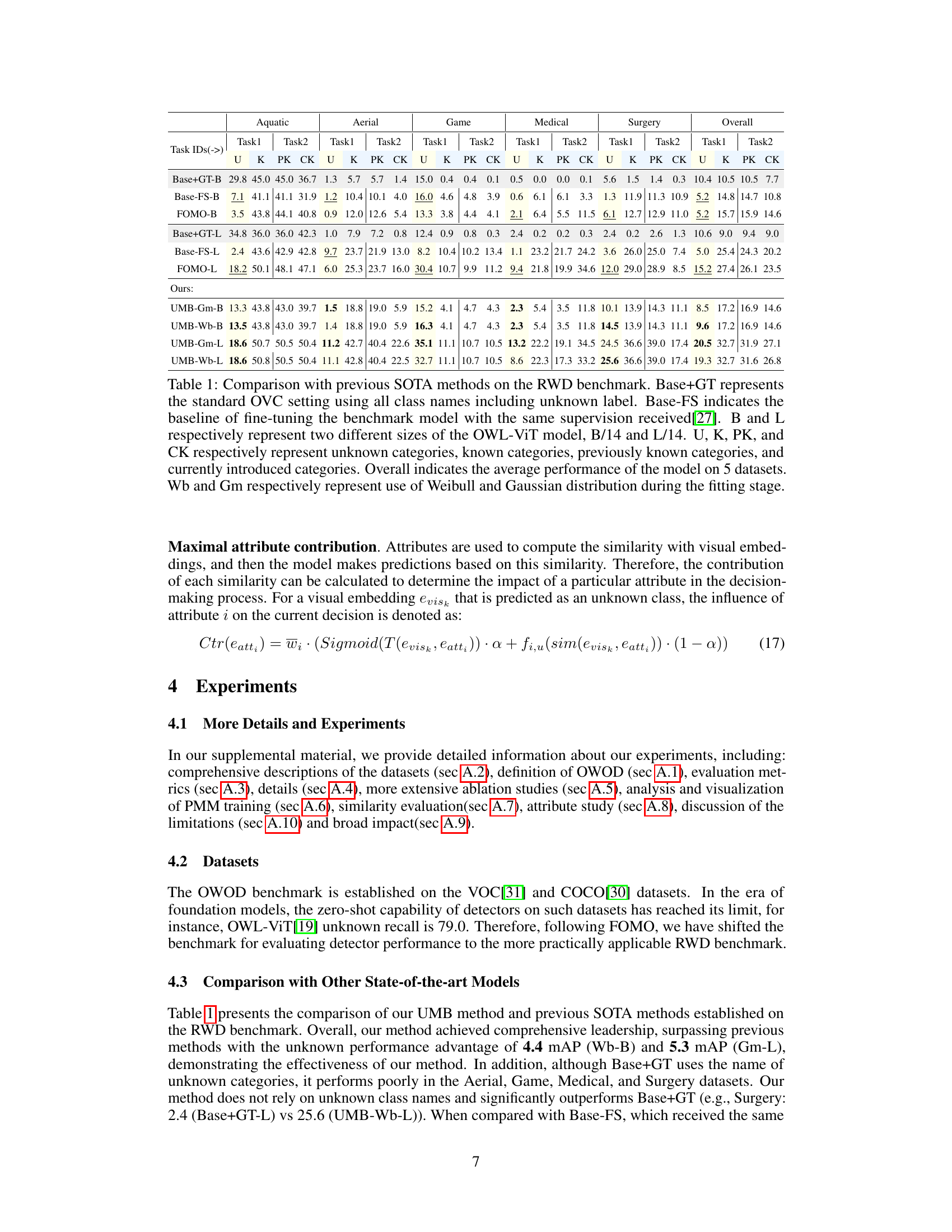

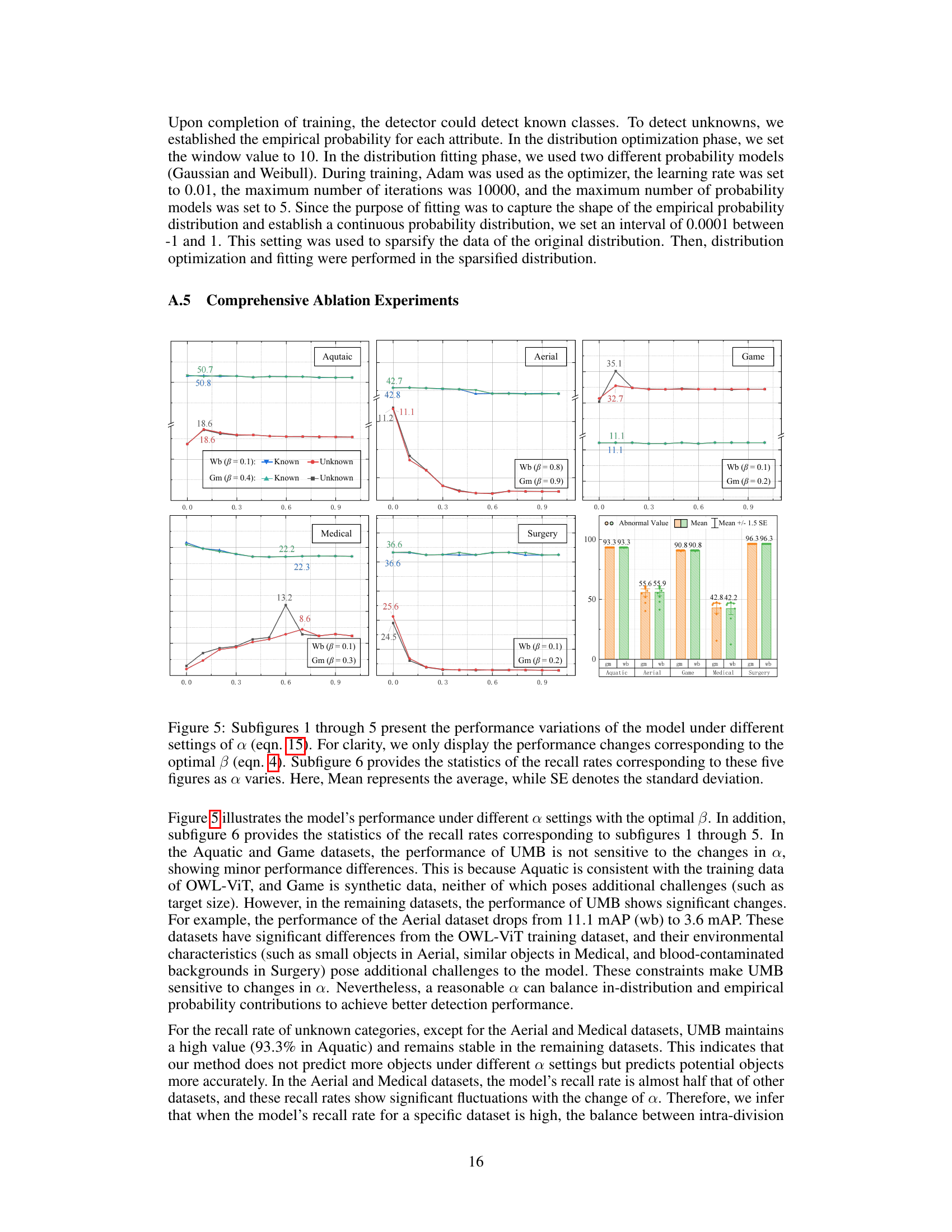

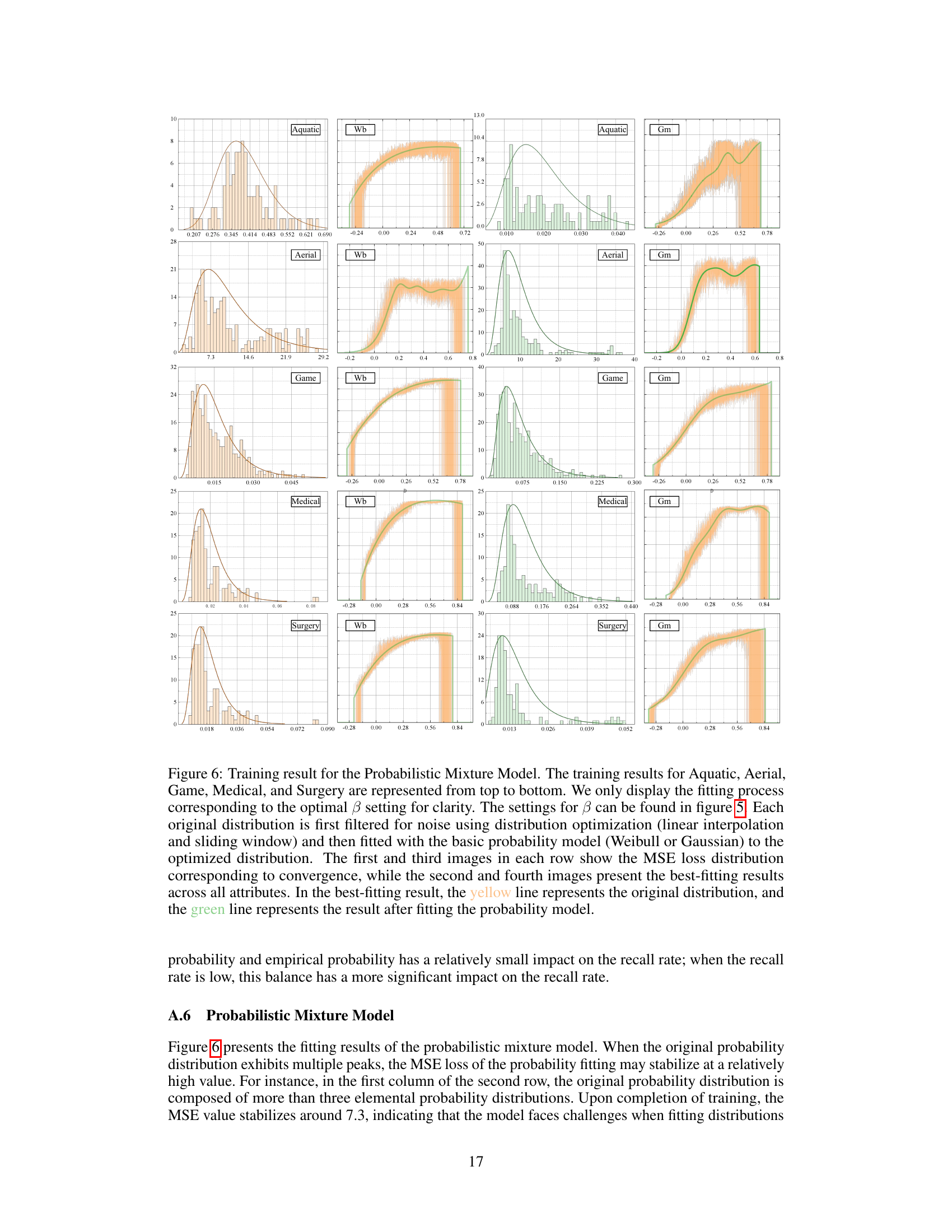

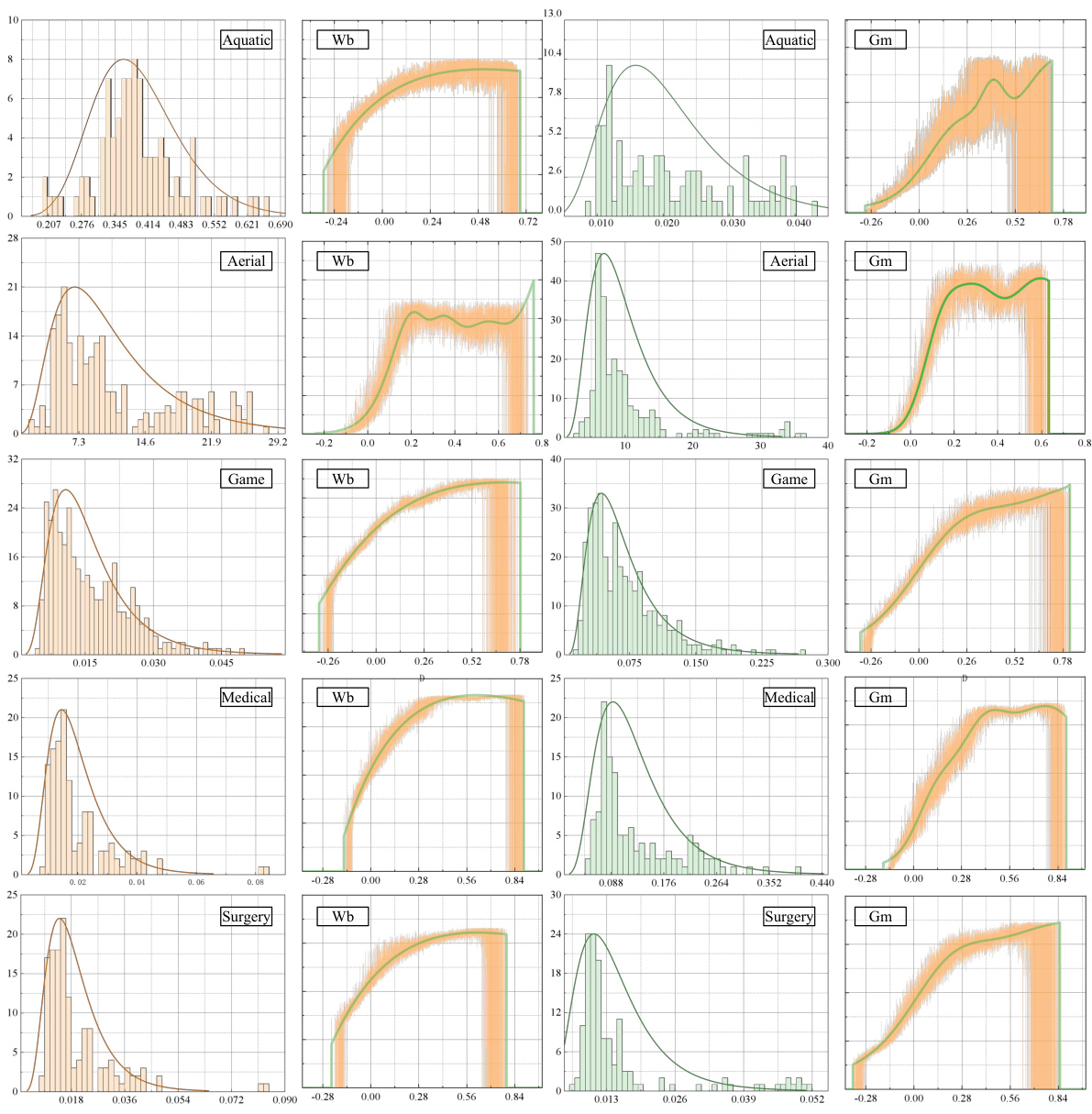

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of creating a continuous probability distribution using three methods: 1. Linear Interpolation on the original distribution to estimate missing points. 2. Sliding window to smooth out noise in the distribution. 3. Probabilistic Mixture Model to fit the optimized distribution. The result is a more accurate and continuous probability distribution, suitable for use in the model.

read the caption

Figure 3: An illustration of the Probability Mixture Model. To establish a continuous probability distribution, we use linear interpolation on the original distribution (left) to estimate missing points and employ the sliding window to eliminate noise within the distribution (middle). Finally, we use the probabilistic mixture model to fit the optimized distribution (right).

🔼 This figure shows the overall architecture of the proposed model, UMB, illustrating the different stages involved in open-world object detection. It starts with generating attributes using an LLM, then building an empirical probability distribution, and finally using a multimodal probabilistic distribution mixture model to infer whether an object belongs to an unknown category or not.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall structure of our UMB. It begins by populating prompt template with known class names and employing large language model (LLM) to generate attributes (Sec. 3.1). These attributes are then filled into template and encoded by text encoder to generate attribute embeddings (Eatt). We model the attributes and their corresponding positive sample probabilities to build empirical probability (Sec. 3.2). We utilize the empirical, in-distribution and out-of-distribution probability to ascertain whether an object pertains to an unknown category (Sec. 3.3).

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed model UMB, highlighting the different stages of processing involved in detecting unknown objects and understanding the model behavior. The process starts with generating textual attributes using an LLM, followed by modeling these attributes and probabilities to identify potential unknown objects. Finally, a decision-making process determines the category of the object.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall structure of our UMB. It begins by populating prompt template with known class names and employing large language model (LLM) to generate attributes (Sec. 3.1). These attributes are then filled into template and encoded by text encoder to generate attribute embeddings (Eatt). We model the attributes and their corresponding positive sample probabilities to build empirical probability (Sec. 3.2). We utilize the empirical, in-distribution and out-of-distribution probability to ascertain whether an object pertains to an unknown category (Sec. 3.3).

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed UMB model. It shows the flow of information, starting with attribute generation using an LLM, through attribute and visual embedding, empirical probability calculation, and finally, the inference process for determining whether an object belongs to a known or unknown category. Each stage is clearly depicted in the diagram, highlighting the model’s key components and their interactions.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall structure of our UMB. It begins by populating prompt template with known class names and employing large language model (LLM) to generate attributes (Sec. 3.1). These attributes are then filled into template and encoded by text encoder to generate attribute embeddings (Eatt). We model the attributes and their corresponding positive sample probabilities to build empirical probability (Sec. 3.2). We utilize the empirical, in-distribution and out-of-distribution probability to ascertain whether an object pertains to an unknown category (Sec. 3.3).

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of creating a continuous probability distribution using three steps: 1. Linear interpolation to estimate missing values; 2. Sliding window to smooth the distribution and remove noise; 3. Probabilistic mixture model to fit the optimized distribution, showing how it starts with an original distribution and through several steps (linear interpolation, sliding window, and mixture model fitting) becomes a continuous and optimized probability distribution.

read the caption

Figure 3: An illustration of the Probability Mixture Model. To establish a continuous probability distribution, we use linear interpolation on the original distribution (left) to estimate missing points and employ the sliding window to eliminate noise within the distribution (middle). Finally, we use the probabilistic mixture model to fit the optimized distribution (right).

🔼 This figure shows the overall architecture of the UMB model proposed in the paper. It illustrates the process of generating attributes using LLM, building empirical probability distribution, and finally inferring unknown objects based on the combined probabilities. The figure shows the flow of information and the different components of the model, including the text and visual encoders, the probabilistic mixture model, and the unknown inference module.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall structure of our UMB. It begins by populating prompt template with known class names and employing large language model (LLM) to generate attributes (Sec. 3.1). These attributes are then filled into template and encoded by text encoder to generate attribute embeddings (Eatt). We model the attributes and their corresponding positive sample probabilities to build empirical probability (Sec. 3.2). We utilize the empirical, in-distribution and out-of-distribution probability to ascertain whether an object pertains to an unknown category (Sec. 3.3).

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed model, UMB, which consists of three main components: Attribute Generation, Text Attribute Modeling (TAM), and Unknown Inference. The Attribute Generation component uses a Large Language Model (LLM) to generate textual attributes for known classes. TAM models these attributes along with their positive sample probabilities to construct an empirical probability distribution. Finally, the Unknown Inference component uses this distribution, along with in-distribution and out-of-distribution probabilities to identify whether an object belongs to an unknown category.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall structure of our UMB. It begins by populating prompt template with known class names and employing large language model (LLM) to generate attributes (Sec. 3.1). These attributes are then filled into template and encoded by text encoder to generate attribute embeddings (Eatt). We model the attributes and their corresponding positive sample probabilities to build empirical probability (Sec. 3.2). We utilize the empirical, in-distribution and out-of-distribution probability to ascertain whether an object pertains to an unknown category (Sec. 3.3).

🔼 This figure presents a detailed overview of the proposed UMB model’s architecture. It illustrates the workflow, starting from attribute generation using an LLM, followed by text and visual encoding, to the final unknown object inference using a multimodal probabilistic distribution mixture model. The model incorporates empirical probability, in-distribution probability, and out-of-distribution probability to make a decision on whether an object belongs to an unknown category.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall structure of our UMB. It begins by populating prompt template with known class names and employing large language model (LLM) to generate attributes (Sec. 3.1). These attributes are then filled into template and encoded by text encoder to generate attribute embeddings (Eatt). We model the attributes and their corresponding positive sample probabilities to build empirical probability (Sec. 3.2). We utilize the empirical, in-distribution and out-of-distribution probability to ascertain whether an object pertains to an unknown category (Sec. 3.3).

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed model UMB. It shows the flow of processing from attribute generation using an LLM to the final prediction of whether an object belongs to a known or unknown category. The key components are attribute modeling, multimodal probabilistic distribution mixture model, and unknown inference.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall structure of our UMB. It begins by populating prompt template with known class names and employing large language model (LLM) to generate attributes (Sec. 3.1). These attributes are then filled into template and encoded by text encoder to generate attribute embeddings (Eatt). We model the attributes and their corresponding positive sample probabilities to build empirical probability (Sec. 3.2). We utilize the empirical, in-distribution and out-of-distribution probability to ascertain whether an object pertains to an unknown category (Sec. 3.3).

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the UMB model. It shows the flow of data through different modules, starting with attribute generation using an LLM, through text and visual encodings, to the final decision of whether an object is known or unknown based on probability distributions. The figure highlights the key components and their interactions in the model.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overall structure of our UMB. It begins by populating prompt template with known class names and employing large language model (LLM) to generate attributes (Sec. 3.1). These attributes are then filled into template and encoded by text encoder to generate attribute embeddings (Eatt). We model the attributes and their corresponding positive sample probabilities to build empirical probability (Sec. 3.2). We utilize the empirical, in-distribution and out-of-distribution probability to ascertain whether an object pertains to an unknown category (Sec. 3.3).

More on tables

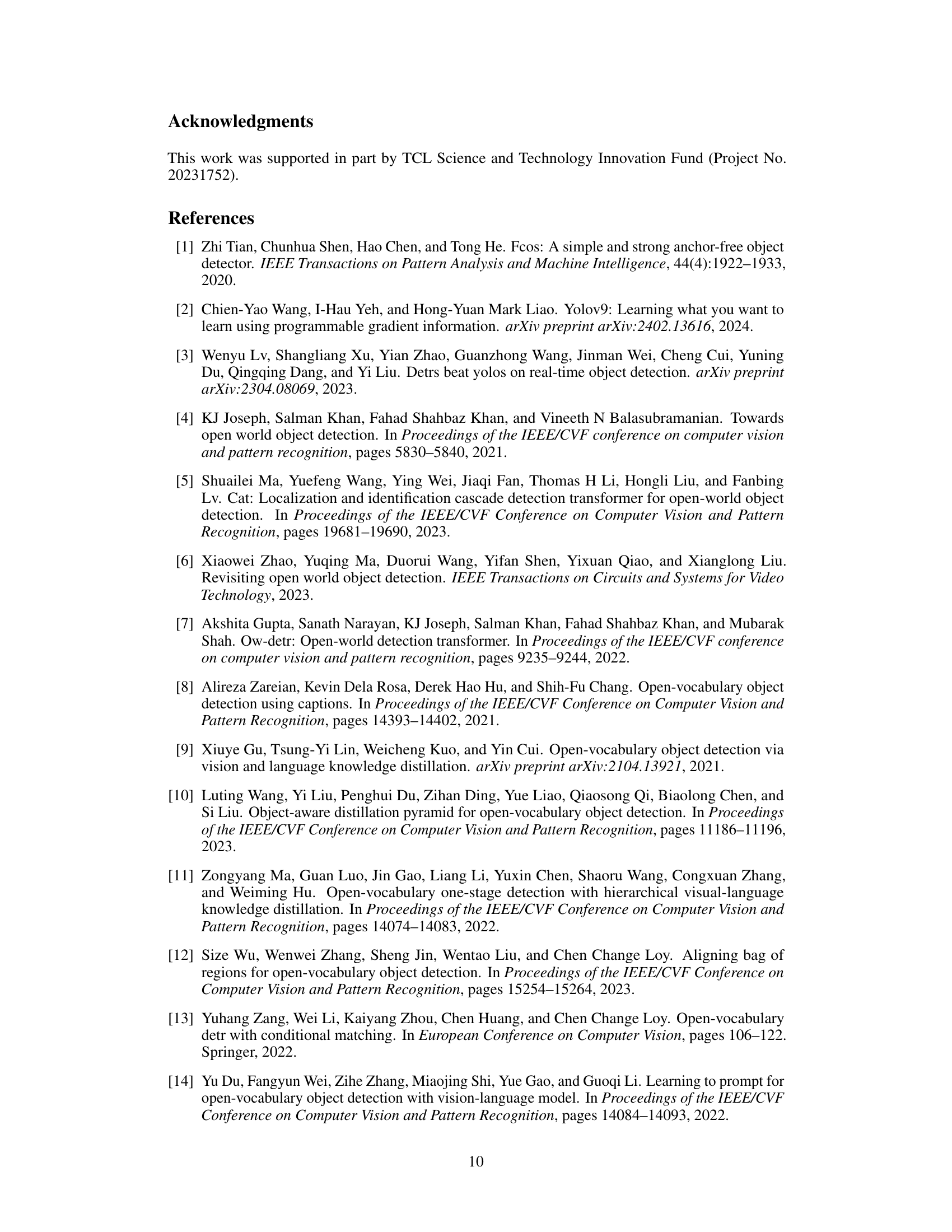

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed UMB model against state-of-the-art (SOTA) open-vocabulary object detection methods on the Real-World Object Detection (RWD) benchmark. It shows the mean Average Precision (mAP) and recall for known and unknown object categories across five datasets, with results broken down by model size and probability distribution fitting method.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with previous SOTA methods on the RWD benchmark. Base+GT represents the standard OVC setting using all class names including unknown label. Base-FS indicates the baseline of fine-tuning the benchmark model with the same supervision received[27]. Band L respectively represent two different sizes of the OWL-ViT model, B/14 and L/14. U, K, PK, and CK respectively represent unknown categories, known categories, previously known categories, and currently introduced categories. Overall indicates the average performance of the model on 5 datasets. Wb and Gm respectively represent use of Weibull and Gaussian distribution during the fitting stage.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed UMB model with other state-of-the-art (SOTA) open-vocabulary object detection (OVD) methods on the Real-World Object Detection (RWD) benchmark. It shows the mean Average Precision (mAP) and recall for known and unknown object categories across five different datasets. The table also breaks down the results by model size (B and L) and the type of probability distribution used during model training (Weibull and Gaussian).

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with previous SOTA methods on the RWD benchmark. Base+GT represents the standard OVC setting using all class names including unknown label. Base-FS indicates the baseline of fine-tuning the benchmark model with the same supervision received[27]. Band L respectively represent two different sizes of the OWL-ViT model, B/14 and L/14. U, K, PK, and CK respectively represent unknown categories, known categories, previously known categories, and currently introduced categories. Overall indicates the average performance of the model on 5 datasets. Wb and Gm respectively represent use of Weibull and Gaussian distribution during the fitting stage.

🔼 This table compares the proposed UMB method against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) open-vocabulary object detection (OVD) methods on the Real-World Object Detection (RWD) benchmark. It shows the performance (in terms of mean Average Precision (mAP) and recall) on both known and unknown object categories, broken down by dataset and model size. Different training scenarios are also considered, highlighting the impact of using different probability distributions (Gaussian and Weibull) within the UMB model.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with previous SOTA methods on the RWD benchmark. Base+GT represents the standard OVC setting using all class names including unknown label. Base-FS indicates the baseline of fine-tuning the benchmark model with the same supervision received[27]. Band L respectively represent two different sizes of the OWL-ViT model, B/14 and L/14. U, K, PK, and CK respectively represent unknown categories, known categories, previously known categories, and currently introduced categories. Overall indicates the average performance of the model on 5 datasets. Wb and Gm respectively represent use of Weibull and Gaussian distribution during the fitting stage.

🔼 This table compares the proposed UMB method with state-of-the-art (SOTA) open-vocabulary object detection (OVD) methods on the Real-World Object Detection (RWD) benchmark. It shows the mean Average Precision (mAP) and recall for known and unknown object categories across five datasets, highlighting the improvement achieved by UMB, especially for unknown classes.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison with previous SOTA methods on the RWD benchmark. Base+GT represents the standard OVC setting using all class names including unknown label. Base-FS indicates the baseline of fine-tuning the benchmark model with the same supervision received[27]. Band L respectively represent two different sizes of the OWL-ViT model, B/14 and L/14. U, K, PK, and CK respectively represent unknown categories, known categories, previously known categories, and currently introduced categories. Overall indicates the average performance of the model on 5 datasets. Wb and Gm respectively represent use of Weibull and Gaussian distribution during the fitting stage.

Full paper#