TL;DR#

Software testing is crucial, and automated test generation is increasingly important. However, current research using Large Language Models (LLMs) focuses mainly on code generation, neglecting test generation. This is problematic as tests are vital to ensure reliability and correctness. Moreover, existing test generation datasets are limited in size, diversity, and focus, hindering progress in this area.

This research addresses the gap by introducing SWT-Bench, a benchmark dataset based on real-world GitHub issues, including ground truth bug fixes and tests. The study evaluates various test generation approaches, including LLM-based code agents. The key finding is that LLM-based code agents, designed for code repair, outperform methods specifically designed for test generation. This highlights the potential of using code agents for test generation and validates SWT-Bench as a valuable resource for future research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the critical gap in LLM-based code agent research by focusing on test generation for real-world bug fixes. It introduces a novel benchmark, offers insights into the capabilities of different methods, and demonstrates that generated tests can significantly improve the precision of code repair. This work opens up new avenues for improving software quality and developer productivity.

Visual Insights#

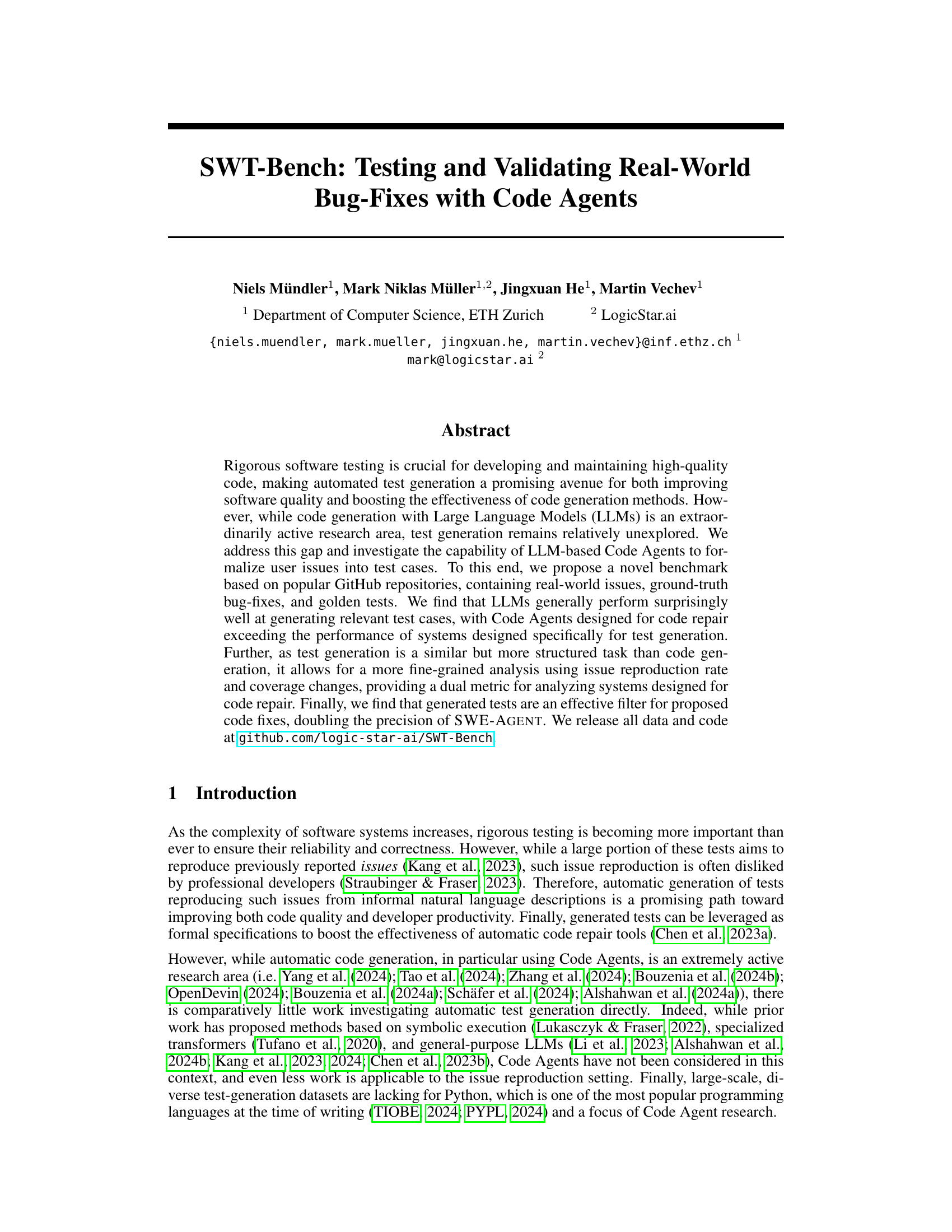

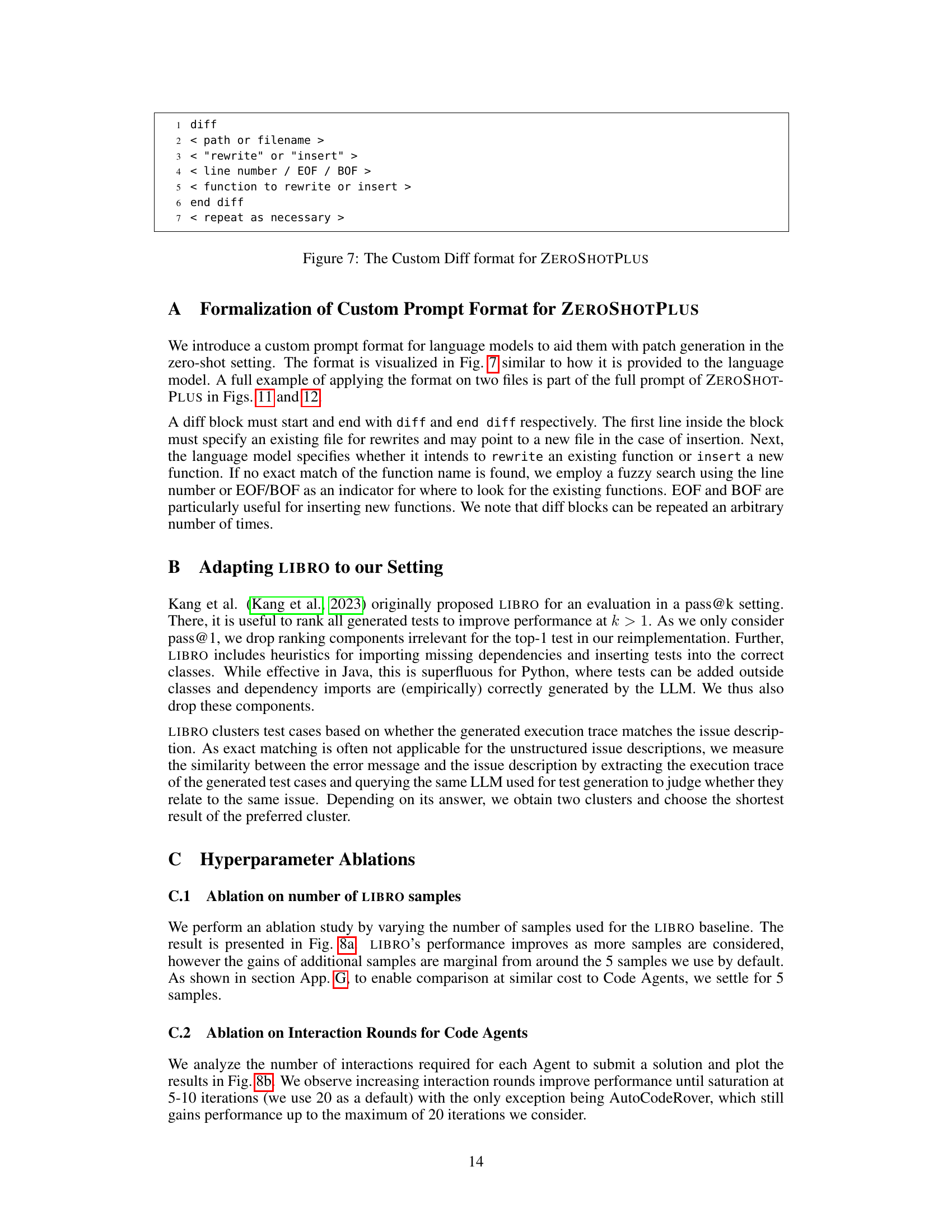

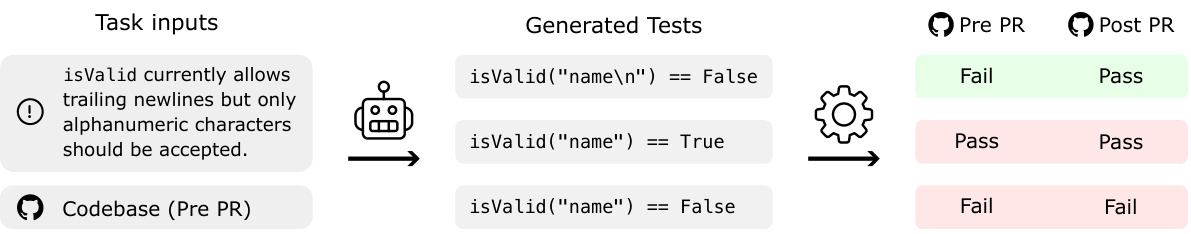

🔼 This figure illustrates how SWT-BENCH evaluates generated tests. An SWT-BENCH instance consists of a natural language description of a bug and the codebase before the bug fix (Pre PR). The goal is to generate tests that will fail on the Pre PR codebase (because they expose the bug), but pass after the bug fix is applied (Post PR). A successful test is labeled ‘F → P’ (fail-to-pass), indicating that it identified the bug.

read the caption

Figure 1: Evaluation of an SWT-BENCH instance. Given an issue description in natural language and the corresponding codebase, the task is to generate tests that reproduce the issue. We considered a test to reproduce the issue if it fails on the codebase before the pull request (PR) is accepted, i.e., before the golden patch is applied, but passes after. We call this a fail-to-pass test (F → P).

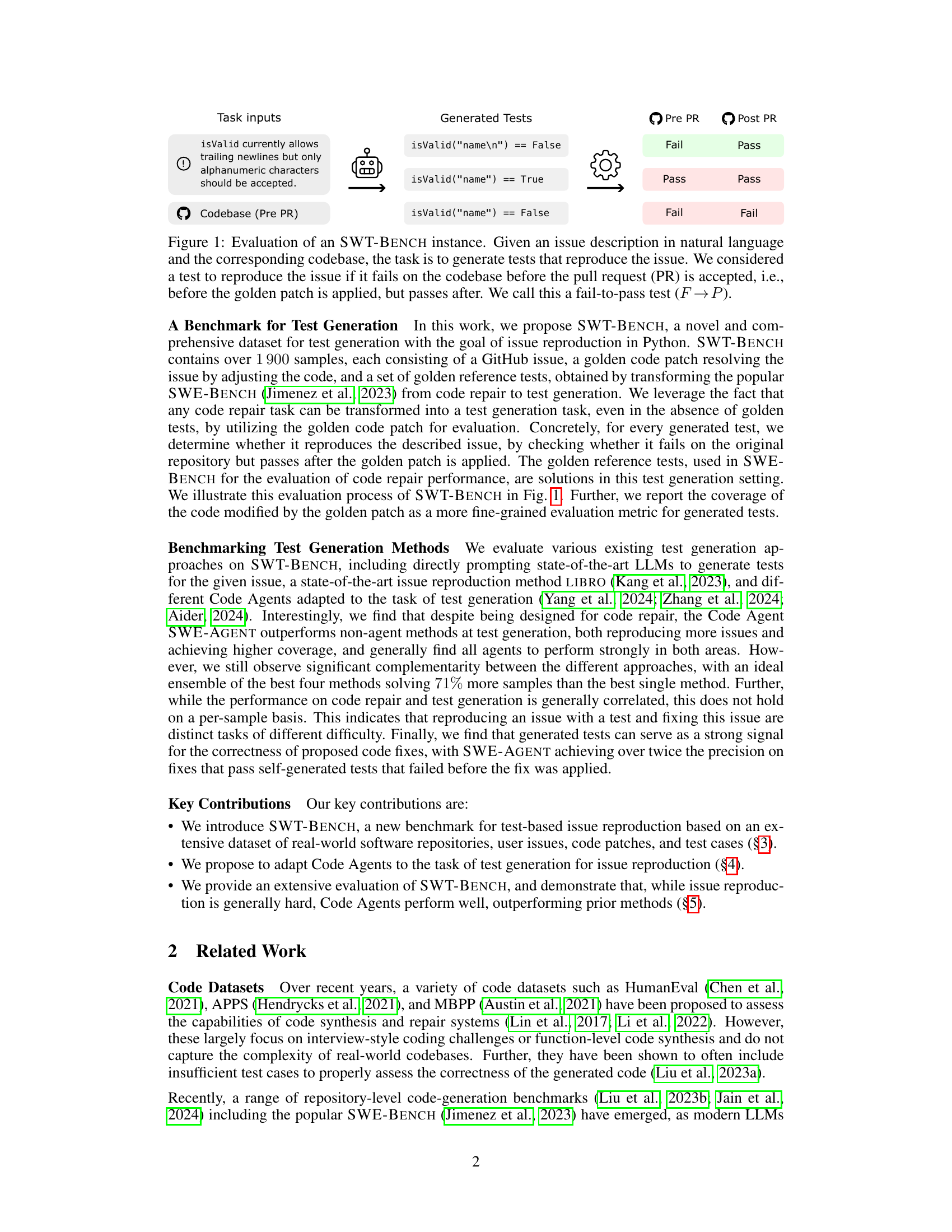

🔼 This table provides a statistical overview of the SWT-BENCH dataset, showing the distribution and range of key characteristics. It includes information about the issue text (number of words), codebase size (number of files and lines of code), existing tests (number of fail-to-pass, fail-to-fail, pass-to-pass, pass-to-fail tests, total number of tests, and code coverage), and golden tests (number of fail-to-pass, pass-to-pass tests added, removed, and number of files and lines of code edited). These statistics help in understanding the complexity and scale of the benchmark dataset and provide context for evaluating the performance of different test generation methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Characterization of different attributes of SWT-BENCH instance.

In-depth insights#

LLM Test Generation#

LLM-based test generation represents a significant advancement in automated software testing. By leveraging the power of large language models, it’s possible to automatically generate test cases from various sources like user stories, issue descriptions, or even existing code. This automation can drastically reduce the time and effort required for test creation, leading to improved software quality and developer productivity. However, several challenges remain. The accuracy and reliability of generated tests vary significantly depending on the LLM’s training data and the complexity of the software. Therefore, validation and refinement of generated tests are crucial to ensure their effectiveness. Furthermore, the approach’s suitability for diverse programming languages and testing methodologies requires further investigation. Benchmarking and evaluation of different LLM-based test generation techniques using robust datasets are essential for advancing the field. Overall, LLM test generation shows substantial promise for streamlining software testing processes, but ongoing research is necessary to address the remaining limitations and fully realize its potential.

SWT-Bench Dataset#

The SWT-Bench dataset is a novel benchmark for test-based issue reproduction in Python. Its creation leverages the structure of SWE-Bench, transforming it from a code repair benchmark into one focused on test generation. This is achieved by including GitHub issues, golden code patches, and sets of golden reference tests. The use of real-world data from popular GitHub repositories makes SWT-Bench particularly valuable for evaluating the efficacy of LLM-based Code Agents. The dataset’s comprehensive nature, including metrics like success rate and change coverage, allows for a fine-grained analysis of various test generation methods. This dual metric approach not only assesses test reproduction but also provides insight into code repair systems. The existence of SWT-Bench significantly advances research in automated test generation, addressing the current lack of large-scale datasets for Python.

Code Agent Methods#

Code agent methods represent a significant advancement in automated software development. They leverage the power of large language models (LLMs) coupled with the ability to interact with and modify the codebase directly. This approach moves beyond simple code generation, enabling more complex tasks such as bug fixing and test generation. The integration of LLMs with an agent interface provides a powerful combination: the LLM’s reasoning abilities are complemented by the agent’s capacity to execute actions within the development environment. This results in higher-quality code modifications, as the agent can iteratively refine its actions based on feedback from the environment. The ability to adapt these agents to different tasks (e.g., code repair vs. test generation) further highlights their flexibility and potential for widespread adoption. However, challenges remain, including ensuring the reliability and robustness of agent actions, and the need for efficient methods to guide the LLM’s decision-making process within the agent framework.

Evaluation Metrics#

Choosing the right evaluation metrics is crucial for assessing the effectiveness of any test generation method. For evaluating test generation, metrics should go beyond simple pass/fail rates and incorporate aspects such as test coverage (measuring how much of the codebase is exercised by the generated tests), and issue reproduction rate (assessing whether the generated tests successfully reveal the targeted bugs). A deeper dive requires considering change coverage, focusing specifically on the lines of code modified by a patch. Furthermore, the precision of the generated tests—that is, the proportion of the generated tests that are actually relevant and effective—is a valuable metric to examine. In addition, metrics like patch well-formedness help evaluate the quality and usability of the generated tests by assessing whether they are syntactically valid and executable. Overall, a multifaceted approach to evaluation, encompassing both quantitative and qualitative aspects, offers a robust assessment of test generation techniques.

Future Work#

The paper’s “Future Work” section implicitly suggests several promising avenues. Expanding SWT-BENCH to other programming languages beyond Python is crucial for broader applicability and impact. Addressing the current limitations of relying on publicly available GitHub repositories, perhaps through creating a private, controlled dataset, would enhance the benchmark’s robustness and mitigate bias. The authors also hint at the need for more sophisticated metrics, moving beyond simple pass/fail rates to encompass a richer understanding of test quality. Finally, integrating more advanced techniques like symbolic execution and exploring the synergy between different test generation methods are vital next steps. In essence, the “Future Work” section highlights the potential for significant improvements and expansions upon the already impressive work presented within the paper.

More visual insights#

More on figures

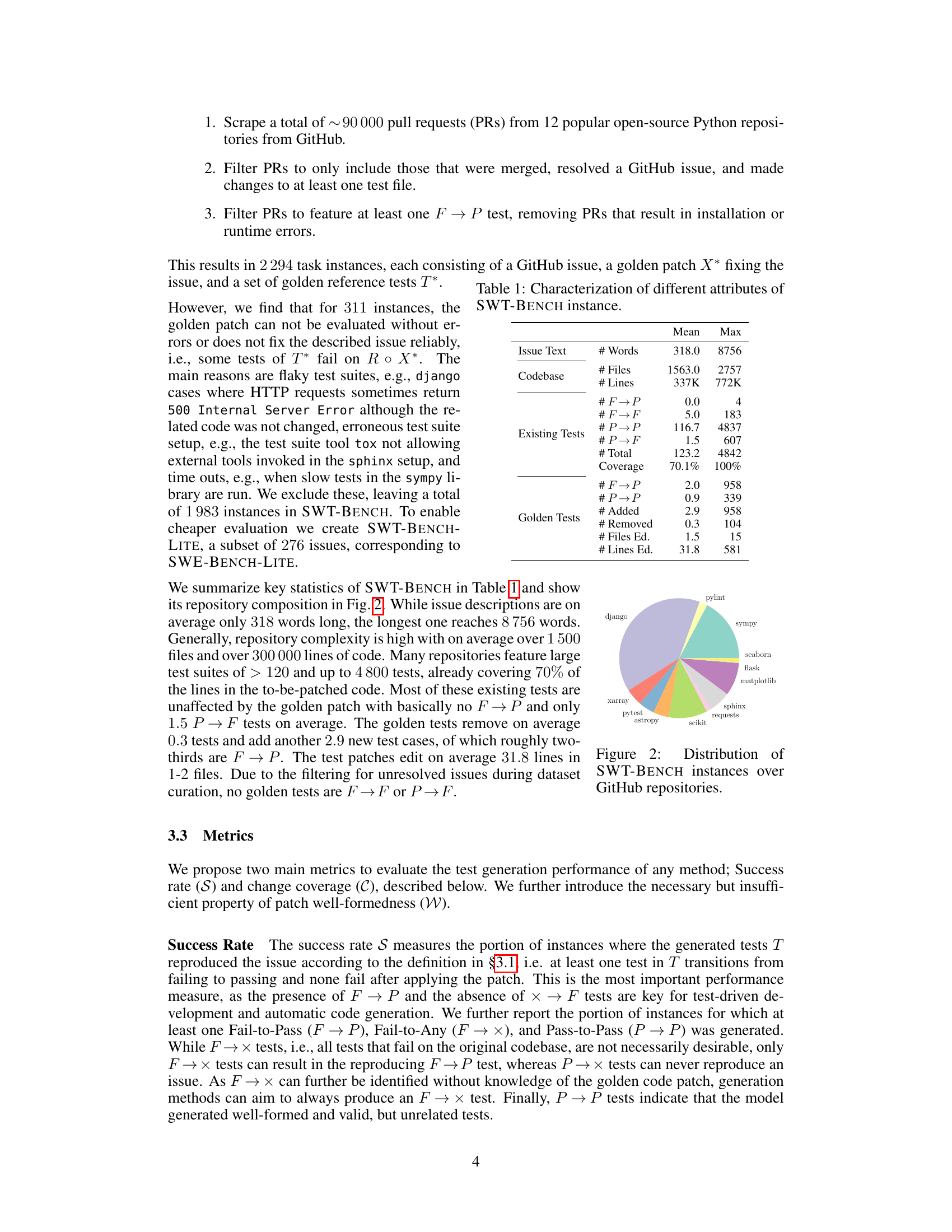

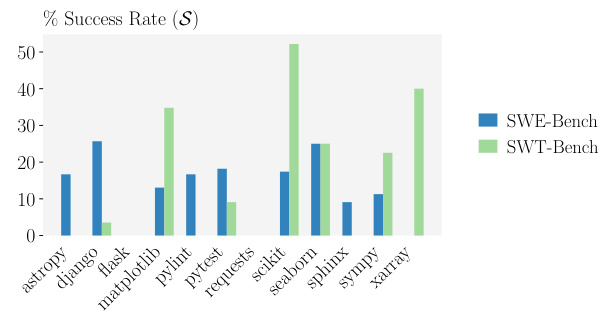

🔼 This pie chart shows the distribution of the 1983 instances of SWT-BENCH across 12 different GitHub repositories. The largest portion belongs to the ‘django’ repository, indicating a higher concentration of Python projects using this framework in the dataset. The other repositories represent a variety of popular Python projects, each contributing a varying number of instances to the benchmark. This visualization helps to understand the diversity of the codebases included in SWT-BENCH and their relative representation in the dataset.

read the caption

Figure 2: Distribution of SWT-BENCH instances over GitHub repositories.

🔼 This figure illustrates how change coverage (AC) is calculated for generated tests. It shows the original codebase (R), the codebase after applying the golden patch (R o X*), and the generated tests (T). The golden tests are represented by T*. The yellow lines indicate lines added by the patch, while the pink lines indicate lines removed or modified. The change coverage (AC) is calculated as the ratio of lines in the patch that are executed by the generated tests to the total number of lines in the patch.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of change coverage AC of the generated tests T, given the original code base R, the golden patch X*, and the golden tests T*.

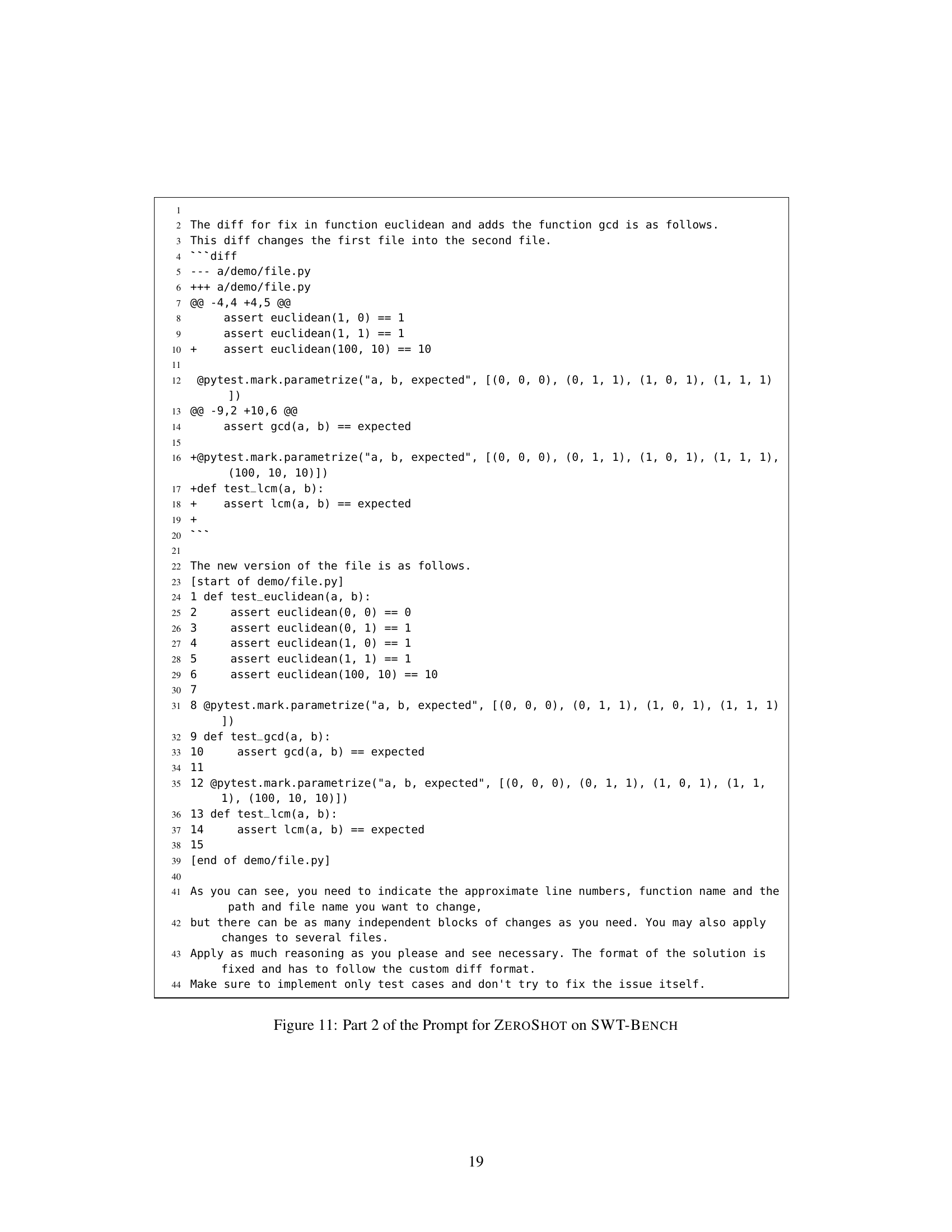

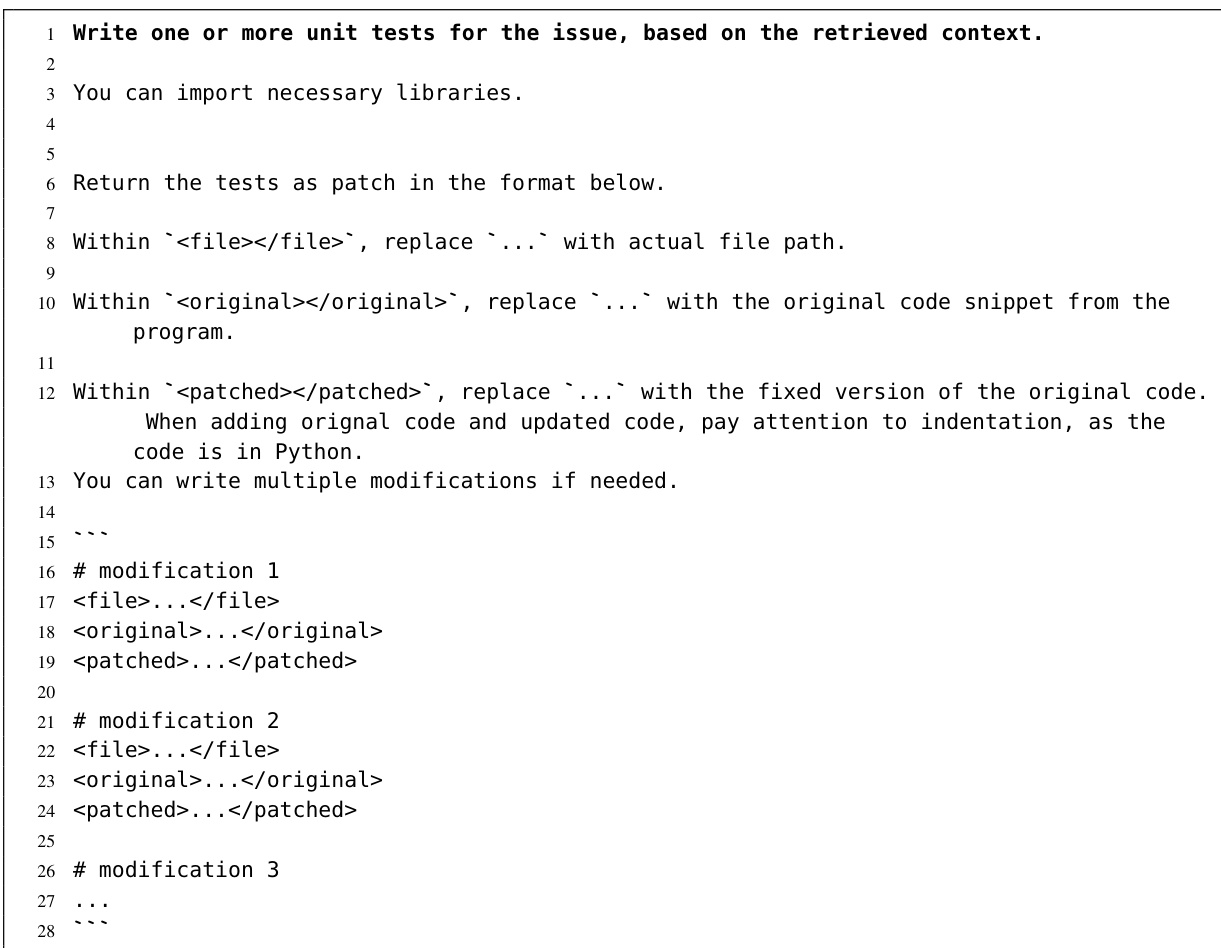

🔼 This figure compares the standard unified diff format used in Git with a fault-tolerant version proposed in the paper. The standard format is very sensitive to small errors and requires precise line numbers and verbatim code snippets. The fault-tolerant format is designed to be more robust to errors introduced by large language models and allows for entire functions or classes to be inserted, replaced, or deleted, making it easier for the models to generate correct patches.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison of the default unified diff format (left) and our fault-tolerant version (right).

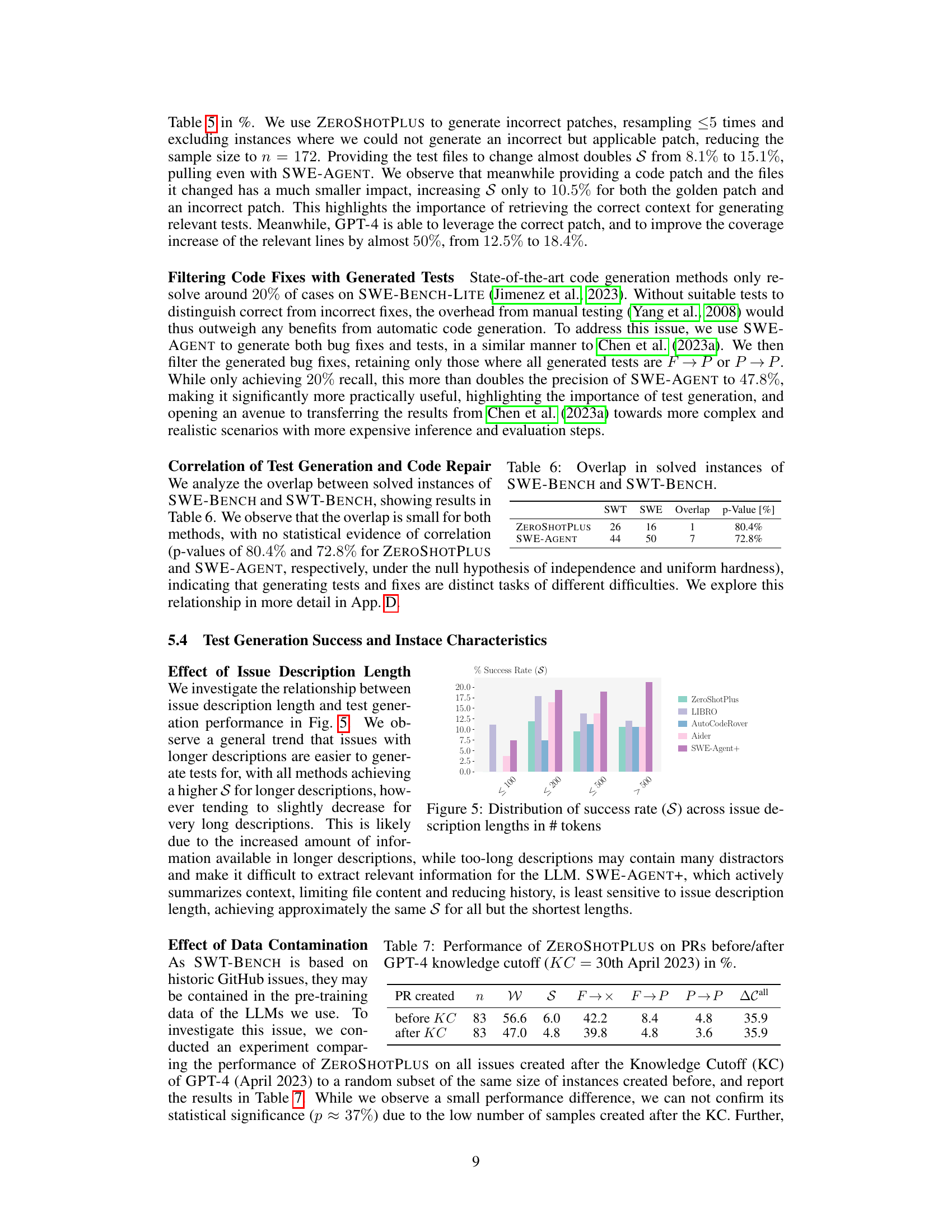

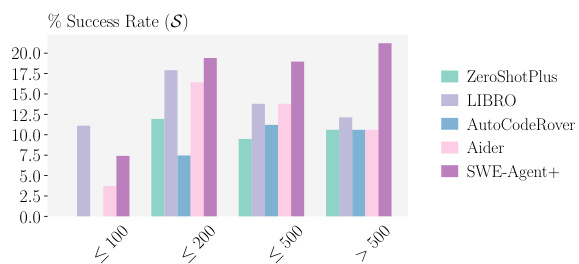

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the length of issue descriptions (measured in the number of tokens) and the success rate (S) of different test generation methods. It reveals a general trend where longer descriptions lead to higher success rates, although the improvement plateaus for very long descriptions. This suggests that more information in longer descriptions aids the test generation process, but excessively long descriptions might contain irrelevant information that hinders performance. The chart highlights the relative performance of different methods across various description length ranges.

read the caption

Figure 5: Distribution of success rate (S) across issue description lengths in # tokens

🔼 This figure shows a Venn diagram illustrating the overlap in the number of instances successfully solved by four different test generation methods: LIBRO, AutoCodeRover, Aider, and SWE-Agent+. It highlights the complementary nature of these methods, demonstrating that combining them results in a higher number of solved instances compared to using any single method alone. The numbers within each section of the Venn diagram indicate the number of instances uniquely or commonly solved by the corresponding methods.

read the caption

Figure 6: Overlap in instances solved by the four best performing methods.

🔼 This figure shows the results of ablation studies on the number of samples and API calls used in the LIBRO and code agent methods for automatic test generation. The left plot shows the effect of varying the number of LIBRO samples on the well-formedness (W) and success rate (S) of generated tests. The right plot illustrates the impact of the number of API calls made by code agents on these metrics. Both plots show that increasing samples and API calls initially improves performance, but this improvement saturates after a certain point. The plots highlight the trade-off between computational cost (number of samples/API calls) and test generation performance.

read the caption

Figure 8: Ablation on the number of samples and API calls for LIBRO and code agents resp.

🔼 This figure shows the ablation study results on the number of samples and API calls for different test generation methods. The left subplot shows the well-formedness (W) and success rate (S) for LIBRO with varying numbers of samples. The right subplot shows W and S for SWE-AGENT, SWE-AGENT+, AUTOCODEROVER, and AIDER with varying numbers of API calls. The plots illustrate the impact of these hyperparameters on the performance of each method. The horizontal dashed lines are reference lines showing the performance at the default hyperparameter values (5 samples for LIBRO and 20 API calls for code agents).

read the caption

Figure 8: Ablation on the number of samples and API calls for LIBRO and code agents resp.

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of the 1983 instances in the SWT-BENCH dataset across different GitHub repositories. The size of each pie slice corresponds to the number of instances from that repository. It illustrates the variety and complexity of real-world projects represented in the benchmark.

read the caption

Figure 2: Distribution of SWT-BENCH instances over GitHub repositories.

🔼 This figure illustrates how change coverage (AC) is calculated. AC measures the portion of the codebase modified by the golden patch that is covered by the generated tests. It shows the original code (R), the golden patch (X*), and the golden tests (T*). It highlights that the coverage calculation includes both lines of code added and lines of code removed (or modified) in the patch, and considers only the lines executed by either the original tests (S) or the golden tests (T*) on both the original and patched codebase.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of change coverage AC of the generated tests T, given the original code base R, the golden patch X*, and the golden tests T*.

More on tables

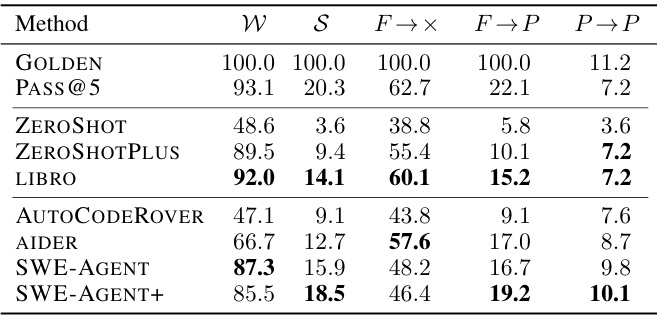

🔼 This table presents the performance of different test generation methods on the SWT-BENCH dataset. The metrics evaluated are: - W (Patch Well-Formedness): Percentage of instances where a well-formed patch was generated. - S (Success Rate): Percentage of instances where the generated tests successfully reproduced the issue. - F→× (Fail-to-Any): Percentage of instances where at least one test failed before the patch and transitioned to any state after the patch was applied. - F→P (Fail-to-Pass): Percentage of instances where at least one test failed before the patch and passed after. - P→P (Pass-to-Pass): Percentage of instances where a test passed both before and after the patch application.

read the caption

Table 2: Rate of well-formed patches (W), successful tests (S), potentially reproducing initially failing tests (F→×), reproducing fail-to-pass tests (F → P), and correct but unhelpful pass-to-pass tests (P → P), in %.

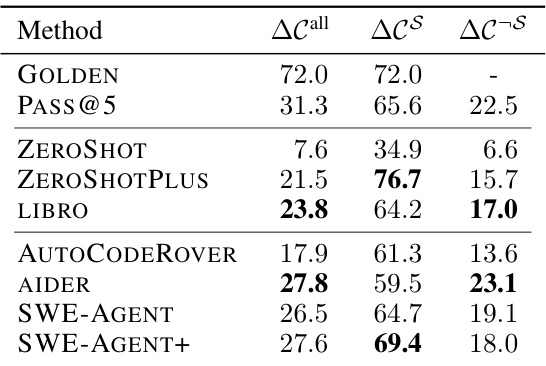

🔼 This table presents the change coverage (AC) of generated tests, categorized by whether the tests successfully reproduced the issue (S) or not (¬S). The change coverage metric measures the proportion of executable lines in the code patch that are covered by the generated tests. The table shows the overall change coverage (ACall), the coverage for successful instances (ACS), and the coverage for unsuccessful instances (AC¬S) for each method.

read the caption

Table 3: Change Coverage AC [%] as defined in §3.3 aggregated over all instances, S instances and non S instances (¬S).

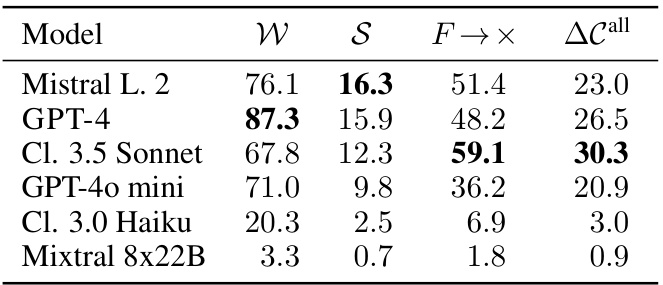

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different Large Language Models (LLMs) when used as the underlying model for SWE-AGENT. It shows the impact of the LLM choice on the success rate (S), well-formedness of the generated patch (W), the rate of potentially reproducing initially failing tests (F→x), and the change coverage (ΔC). The results demonstrate the sensitivity of SWE-AGENT’s performance to the choice of LLM.

read the caption

Table 4: Comparison of different underlying LLMs for SWE-AGENT, all in %.

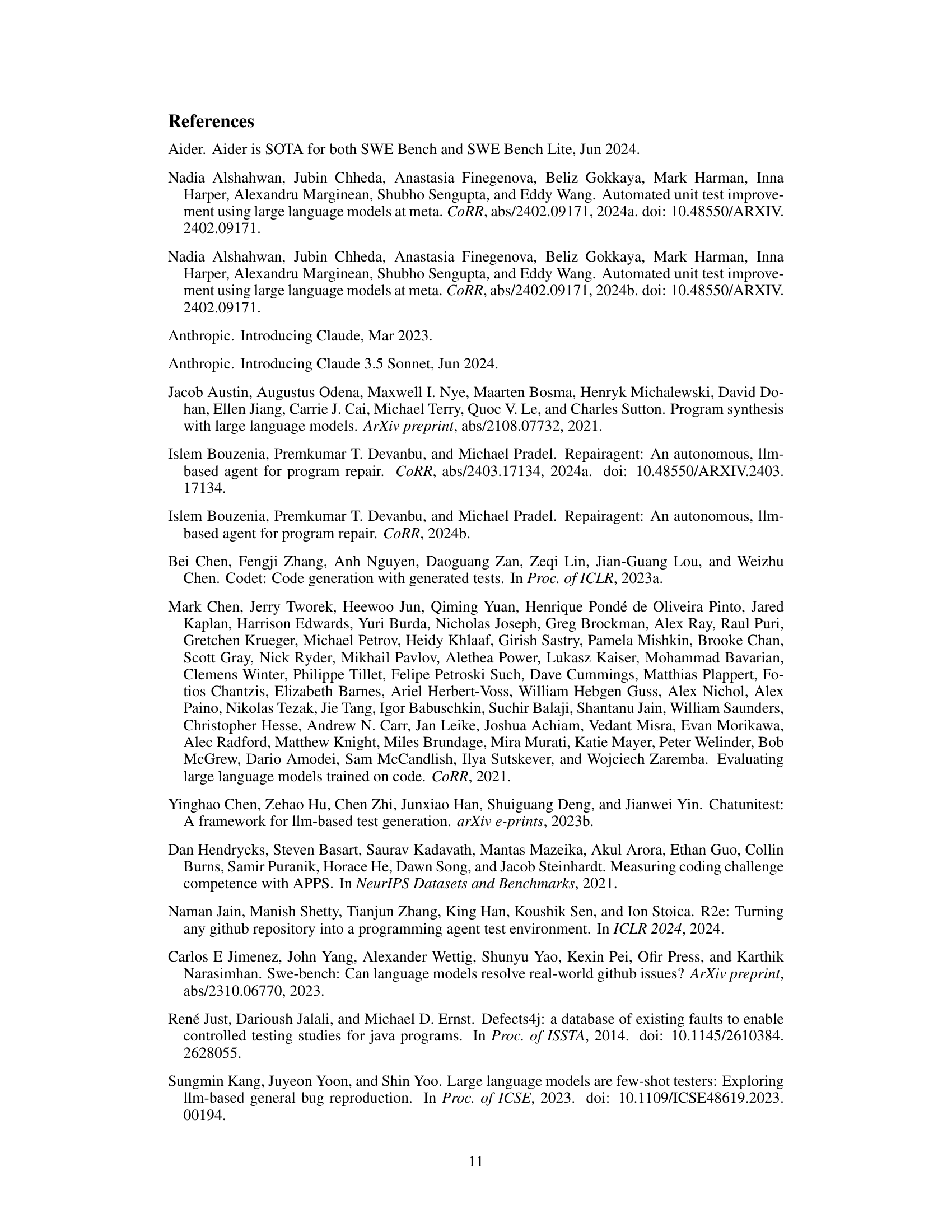

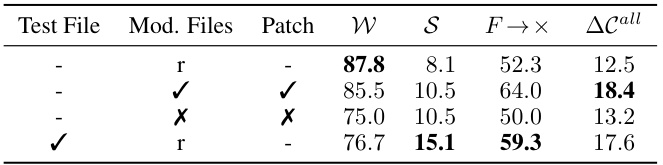

🔼 This table presents the results of the ZEROSHOTPLUS method under different conditions. It shows the impact of providing different information (test files, golden patches, incorrect patches, and files retrieved using BM25) to the model on the success rate (S), well-formedness of the patch (W), the rate of tests that fail on the original codebase but pass after the patch is applied (F→P), and the change coverage (ΔC). The results indicate that providing the test files to change has a significant impact on the performance of the model. Using a golden or incorrect patch with the files changed by the patch improved performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Performance of ZEROSHOTPLUS, given the test file to change, none (-), the golden (✔) or an incorrect (✗) code patch, and the files retrieved via BM-25 (r), or modified by the golden (✔) or incorrect patch (✗).

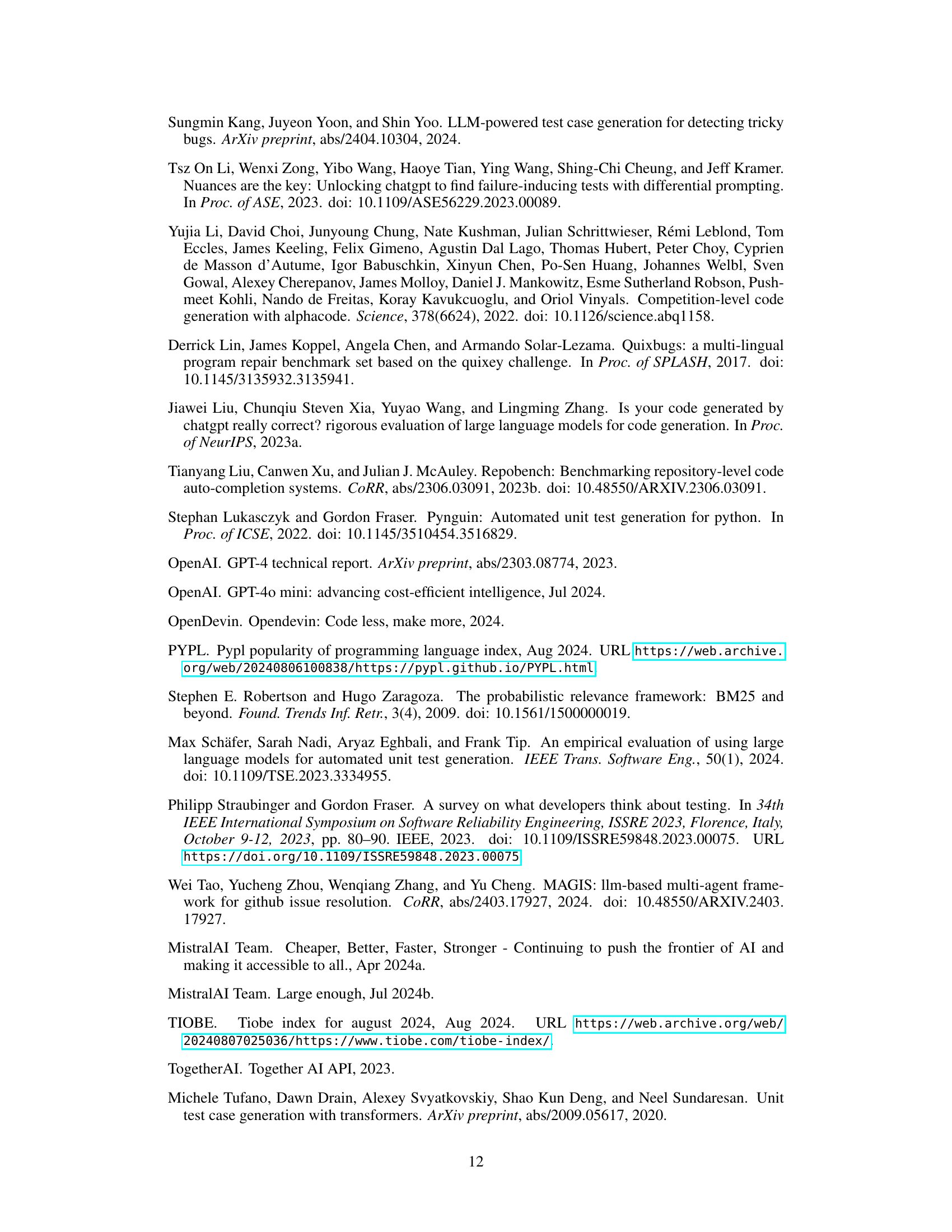

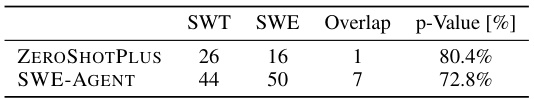

🔼 This table shows the overlap between instances solved by SWE-BENCH and SWT-BENCH for two different methods: ZEROSHOTPLUS and SWE-AGENT. It demonstrates the low correlation between success on the two benchmarks. The p-values indicate there’s no statistical significance in the correlation.

read the caption

Table 6: Overlap in solved instances of SWE-BENCH and SWT-BENCH.

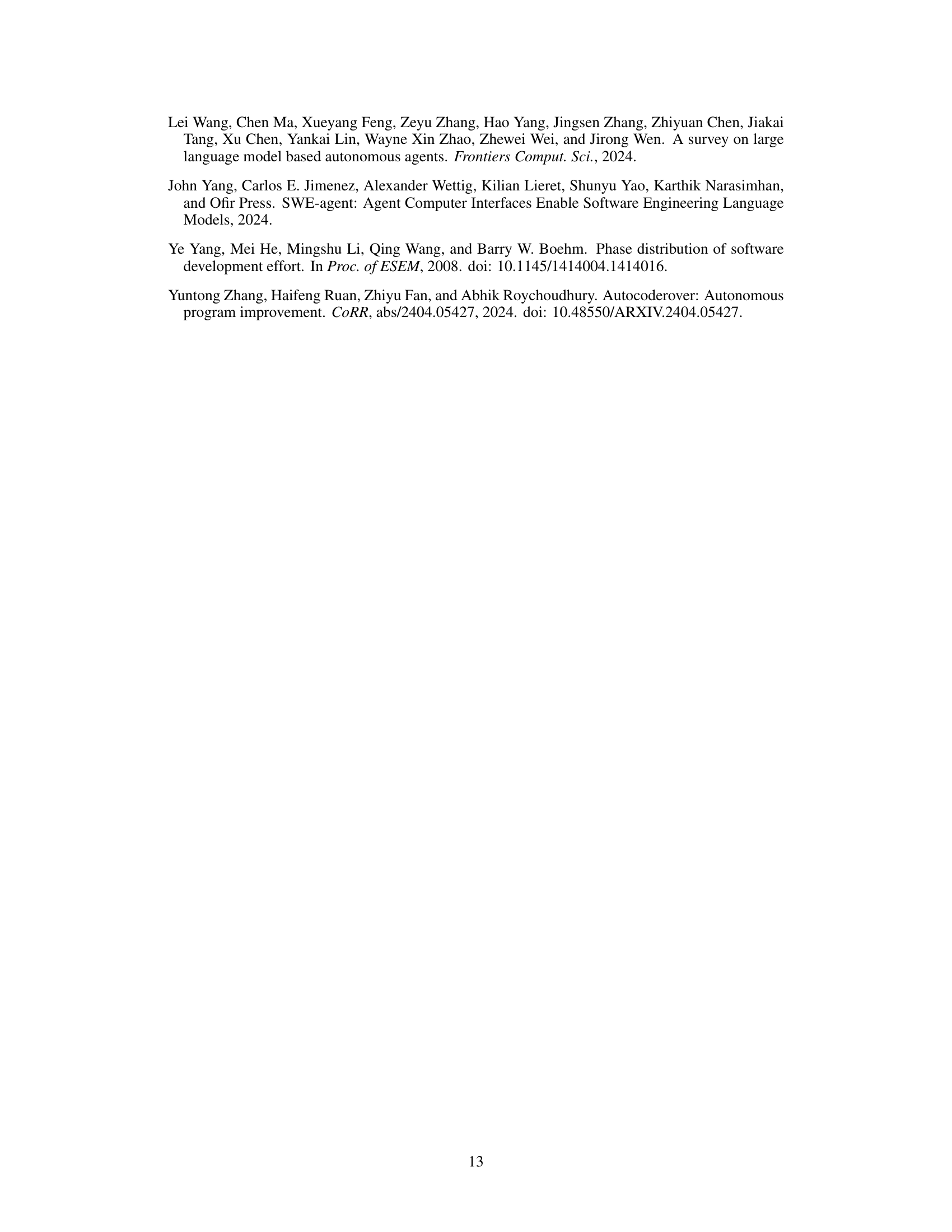

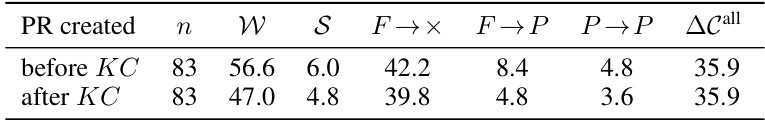

🔼 This table presents the performance of the ZEROSHOTPLUS method on pull requests (PRs) created before and after the GPT-4 knowledge cutoff date (KC). It shows the success rate (S), the proportion of well-formed patches (W), the rate of tests that initially failed and still failed after the patch (F→F), the rate of tests that initially failed and passed after the patch (F→P), the rate of tests that initially passed and still passed after the patch (P→P), and the average number of API calls (ΔCall) for each category. The data is used to investigate the impact of data contamination on the performance of the model.

read the caption

Table 7: Performance of ZEROSHOTPLUS on PRs before/after GPT-4 knowledge cutoff (KC = 30th April 2023) in %.

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the temperature parameter T for the ZEROSHOTPLUS method using GPT-4. It shows the impact of varying the temperature on several key metrics: the rate of well-formed patches (W), the success rate (S), the rate of potentially reproducing initially failing tests (F→×), the rate of reproducing fail-to-pass tests (F→P), the rate of correct but unhelpful pass-to-pass tests (P→P), and the average change coverage (ΔC). The results are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on 25 samples (n=25). The table helps understand the effect of temperature on the model’s performance and stability.

read the caption

Table 8: Comparison of ZEROSHOTPLUS for different T on GPT-4 (95% CI, n = 25).

🔼 This table presents the cost of using different large language models (LLMs) with the SWE-AGENT on the SWT-BENCH Lite dataset. It shows the monetary cost associated with each LLM, providing a comparison of the financial resources required for different model choices in the experimental setup.

read the caption

Table 9: Cost of different LLMs running SWE-AGENT on SWT-BENCH Lite in USD

🔼 This table presents the cost, in USD, of running different test generation methods on the SWT-BENCH Lite benchmark using the GPT-4 language model. The methods compared include various zero-shot prompting techniques (ZEROSHOT, ZEROSHOTPLUS, PASS@5), the state-of-the-art LIBRO method, and three code agent approaches (AIDER, AUTOCODEROVER, SWE-AGENT, SWE-AGENT+). The costs reflect the expenses incurred by using the language model for each method.

read the caption

Table 10: Cost of running different methods on SWT-BENCH Lite using GPT-4 in USD

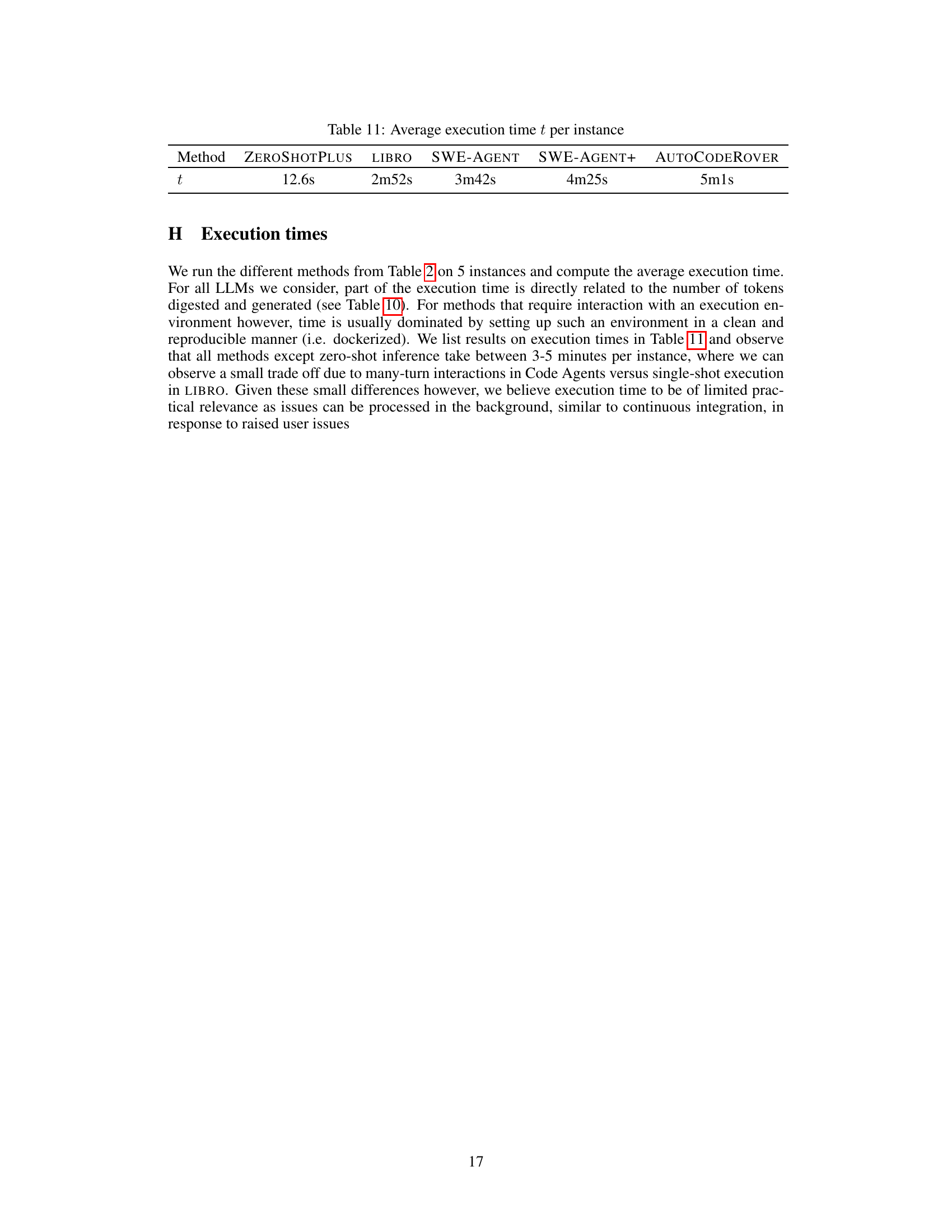

🔼 This table presents the average execution time for different test generation methods. The methods include ZEROSHOTPLUS, LIBRO, SWE-AGENT, SWE-AGENT+, and AUTOCODEROVER. The execution times are measured in seconds (s) and minutes and seconds (m:ss). The table shows that zero-shot methods are much faster than agent-based methods, and that agent-based methods have execution times on the order of several minutes.

read the caption

Table 11: Average execution time t per instance

Full paper#