↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Disentangled Representation Learning (DRL) aims to decompose underlying factors behind observations. However, current DRL methods often assume statistical independence between factors, ignoring real-world correlations. This assumption limits the practical applications and robustness of DRL models. Existing approaches also often lack interpretability and struggle with complex real-world data.

This paper introduces GEM, a graph-based framework that addresses these limitations. GEM uses a bidirectional weighted graph to represent attributes and their relationships, using a Beta-Variational Autoencoder (β-VAE) to extract initial attributes and a Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM) to discover and rank correlations. This approach achieves fine-grained, practical, unsupervised disentanglement, outperforming state-of-the-art methods in both disentanglement and reconstruction. The integration of MLLMs also enhances interpretability and generalizability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in disentangled representation learning (DRL) as it tackles the limitations of existing methods by incorporating multimodal large language models (MLLMs) to improve disentanglement and interpretability. It introduces a novel approach to DRL that addresses the challenging problem of correlated factors by leveraging the power of MLLMs, thus opening new avenues for practical and robust DRL models.

Visual Insights#

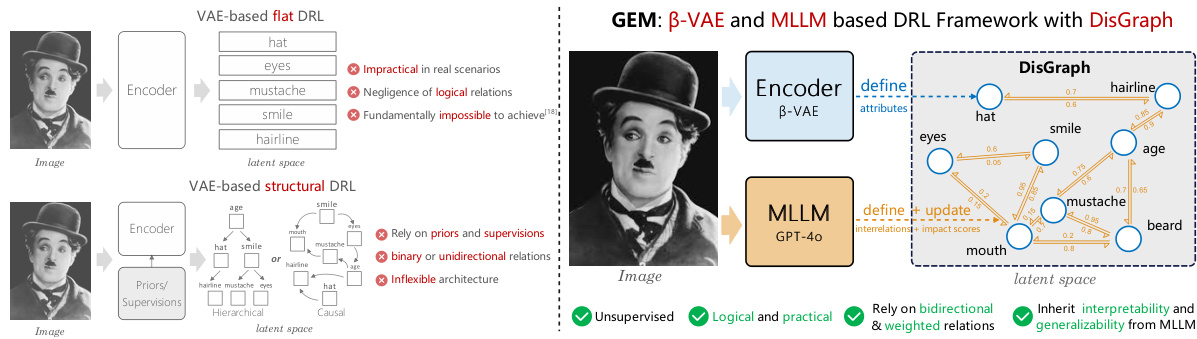

This figure compares traditional disentangled representation learning (DRL) frameworks with the proposed GEM framework. The left side shows limitations of conventional methods, such as being impractical for real-world scenarios due to the neglect of logical relations between factors. The right side highlights GEM’s advantages, including its unsupervised nature, logical and practical approach using bidirectional and weighted relations, and improved interpretability and generalizability by integrating a bidirectional weighted graph and Multimodal Large Language Model (MLLM).

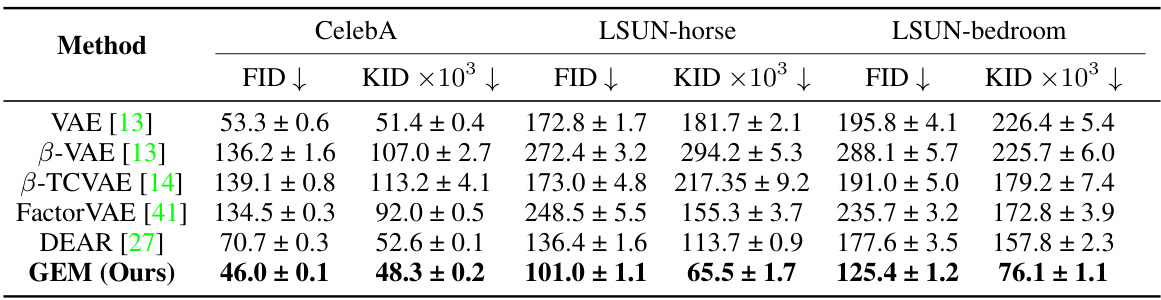

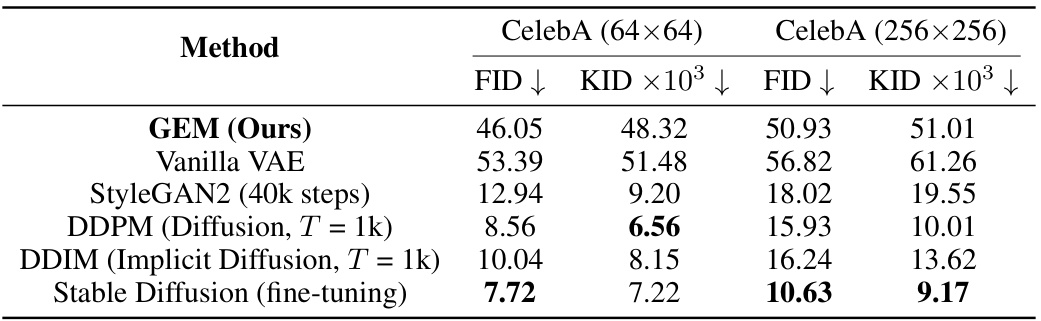

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed GEM model against several state-of-the-art DRL methods. The comparison is based on two metrics: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Kernel Inception Distance (KID). Lower scores indicate better performance in terms of image reconstruction quality. The results show that GEM outperforms other methods on three datasets: CelebA, LSUN-horse, and LSUN-bedroom.

In-depth insights#

Disentangled DRL#

Disentangled representation learning (DRL) aims to decompose complex data into independent, interpretable factors. Traditional approaches often struggle with real-world data where factors are correlated, leading to incomplete or inaccurate disentanglement. Advanced methods address this by incorporating structural information, such as hierarchical relationships or causal dependencies between factors. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of the data and improved disentanglement performance. However, these methods frequently rely on strong assumptions or prior knowledge, limiting their applicability to fully unsupervised scenarios. Future research should focus on developing more robust and flexible DRL techniques capable of handling complex correlations and high-dimensional data in a completely unsupervised manner, while maintaining interpretability and generalizability.

Multimodal MLLMs#

The concept of “Multimodal MLLMs” points towards a significant advancement in artificial intelligence, combining the strengths of large language models (LLMs) with the capacity to process multiple modalities of data. Multimodality allows these models to understand and generate information from various sources like text, images, audio, and video, surpassing the limitations of unimodal LLMs. This opens up exciting possibilities for applications requiring complex interactions between different data types. The power of MLLMs stems from their ability to capture contextual information and relationships, allowing them to excel in tasks requiring nuanced understanding and generation. Combining this capability with the richness of multimodal data creates a powerful tool capable of tackling previously impossible tasks. However, it’s crucial to address the challenges associated with multimodal LLMs, including the increased computational cost and the need for large, high-quality datasets across various modalities. Furthermore, ethical implications surrounding the responsible development and use of these models, particularly regarding bias, fairness and potential misuse, warrant careful consideration and mitigation strategies.

Graph-based GEM#

The proposed Graph-based GEM framework presents a novel approach to disentangled representation learning (DRL). It leverages a bidirectional weighted graph to capture both the individual attributes and their interrelations. The framework integrates two complementary modules: a B-VAE module extracts initial attributes as graph nodes, and a multimodal large language model (MLLM) module discovers and ranks correlations between attributes, updating the graph’s weighted edges. This approach addresses the limitations of conventional DRL methods, which often assume statistical independence between factors. By incorporating the MLLM, GEM enhances interpretability and generalizability, moving beyond the limitations of purely data-driven approaches. The use of a weighted, bidirectional graph allows for a more nuanced representation of the complex dependencies between different attributes, making it suitable for real-world scenarios. The framework’s ability to learn both fine-grained attributes and their high-level relationships suggests its potential for improved performance in various applications requiring disentangled representations, particularly those involving rich, multimodal data.

Interpretability & Limits#

The concept of “Interpretability & Limits” in a research paper would delve into the explainability of the model’s internal mechanisms and its inherent boundaries. It would explore how well the model’s predictions can be understood and the factors limiting its performance. For example, model architecture plays a significant role; simpler architectures may be easier to interpret but lack the power of complex, less interpretable ones. Similarly, data limitations restrict the model’s ability to generalize beyond the training data, highlighting the importance of data quality and diversity. Algorithmic constraints, like reliance on specific assumptions or limitations in the chosen optimization method, would also be discussed. The section would likely feature an analysis of the model’s generalizability across different datasets or scenarios, and a discussion of its failure points. Finally, it would likely address the ethical implications of utilizing a model with limited transparency or potentially biased results.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the robustness and scalability of GEM is crucial, especially when dealing with extremely large datasets or high-dimensional data. This may involve exploring more efficient graph neural network architectures and novel optimization techniques for handling the computational complexities of large graphs. Additionally, investigating alternative methods for capturing and modeling inter-attribute relationships beyond the current MLLM-based approach could significantly enhance the model’s performance and generalizability. Exploring different graph representations, such as causal graphs or knowledge graphs, might reveal more intricate relationships between factors. Finally, applying GEM to a broader range of tasks and modalities is a key area for future research. This includes extending GEM to handle video data, 3D data, or other complex data structures that pose significant challenges for disentanglement. Furthermore, evaluating GEM on diverse downstream tasks (e.g., image generation, manipulation, and style transfer) would provide crucial insights into its practical applications and effectiveness in different contexts. Incorporating additional regularization techniques or inductive biases during training might further improve the model’s ability to learn truly disentangled representations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure compares traditional disentangled representation learning (DRL) frameworks with the proposed GEM framework. The left side highlights limitations of existing methods, such as their impracticality in real scenarios, negligence of logical relations between attributes, and reliance on priors and supervisions. In contrast, the right side showcases GEM’s advantages: unsupervised learning, consideration of bidirectional and weighted relations between attributes, and enhanced interpretability and generalizability due to the integration of β-VAE and multimodal large language models (MLLMs).

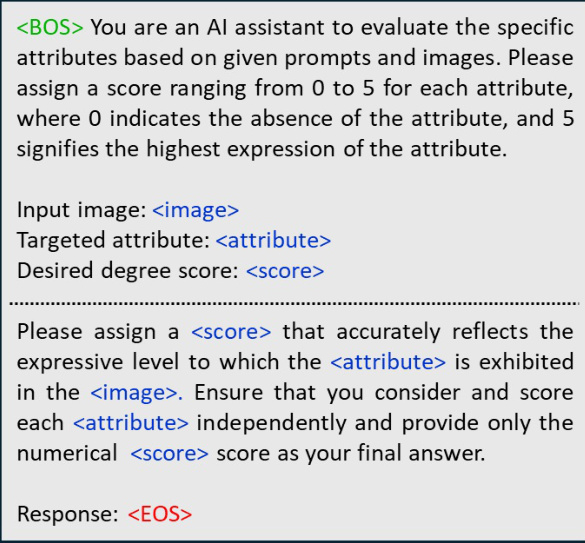

This figure illustrates the concept of using MLLMs (large language models) to learn the statistical relationships between attributes, rather than the absolute scores themselves. The example shows scores from MLLMs for ‘age’ and ‘baldness’ fluctuating across different images. The authors emphasize that this fluctuation is acceptable because their proposed GEM model focuses on learning the relationships, not the exact numerical scores provided by the MLLM.

This figure illustrates the GEM framework’s architecture. It shows two main branches: a B-VAE branch for disentangling factors and a MLLM branch for discovering and ranking inter-factor relations. The output of both branches feeds into a DisGraph (a bidirectional weighted graph) which is dynamically updated by a GNN (Graph Neural Network).

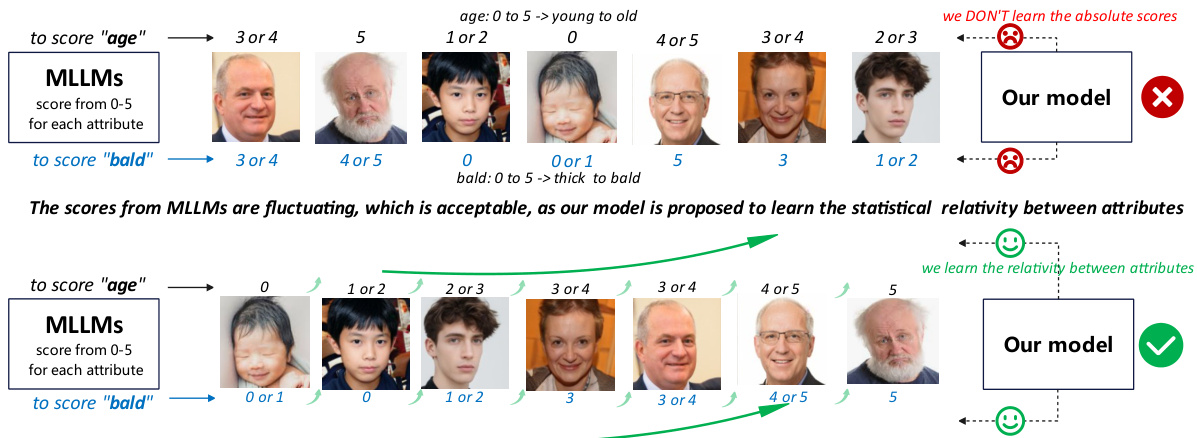

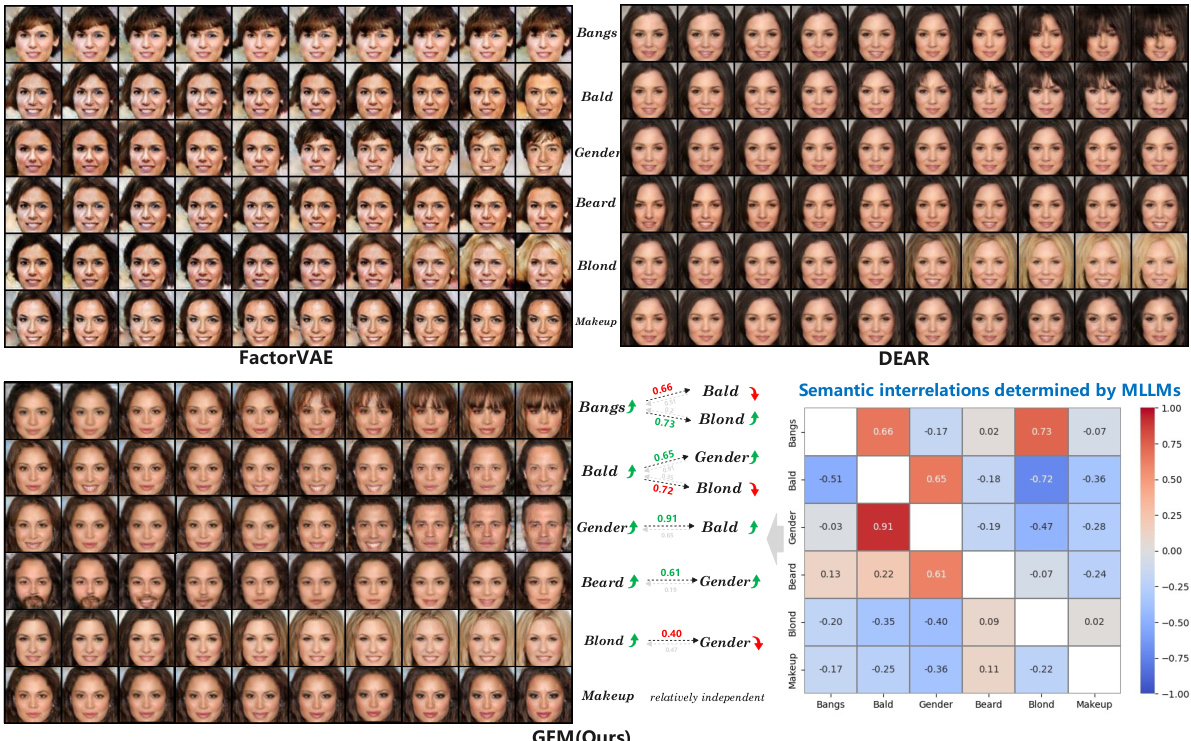

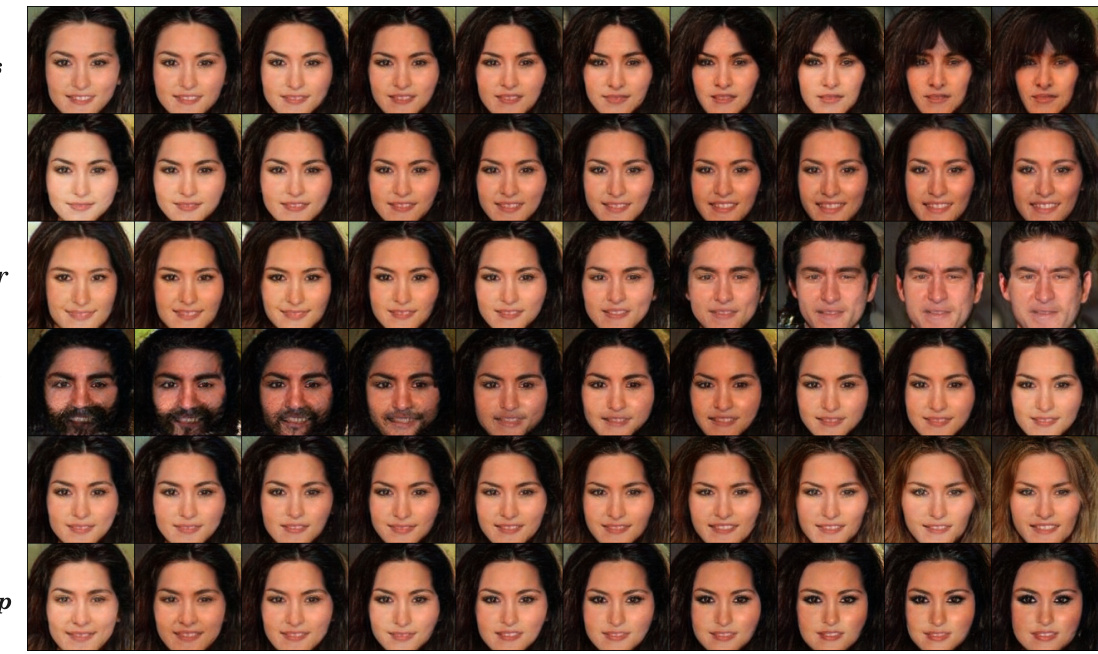

This figure compares the performance of GEM against FactorVAE and DEAR in terms of disentanglement quality for six fine-grained facial attributes (Bangs, Bald, Gender, Beard, Blond, and Makeup). It shows traversals across the latent dimensions for each method. The heatmap illustrates the bidirectional relationships between attributes, as determined by the MLLM in GEM, demonstrating GEM’s ability to capture fine-grained details and practical interrelations.

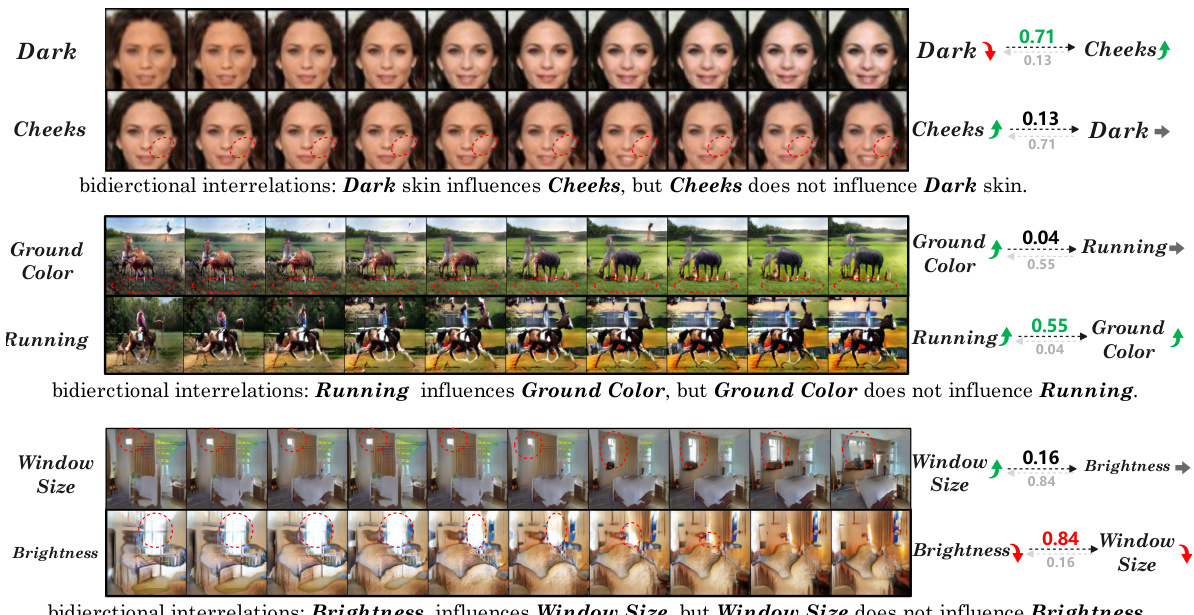

This figure shows qualitative results demonstrating GEM’s ability to perform relation-aware disentanglement on complex scenes from the LSUN dataset (bedroom and horse). It showcases examples of fine-grained attributes with inconsistent bidirectional relations, highlighting GEM’s capacity to capture complex inter-attribute relationships, even those that are not strictly causal or symmetric.

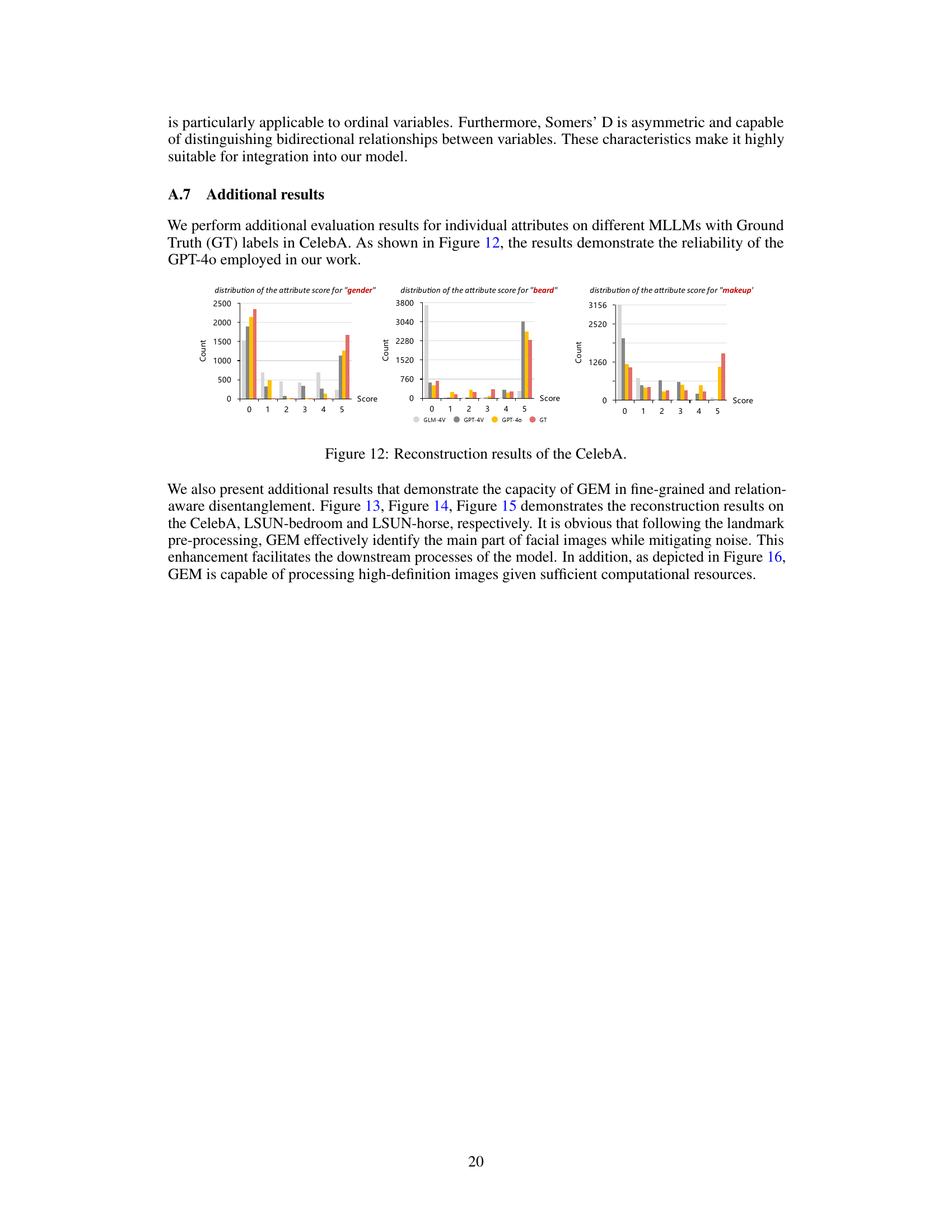

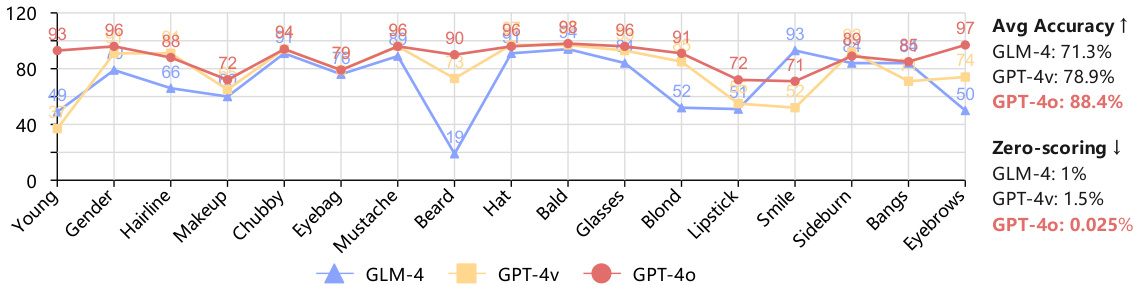

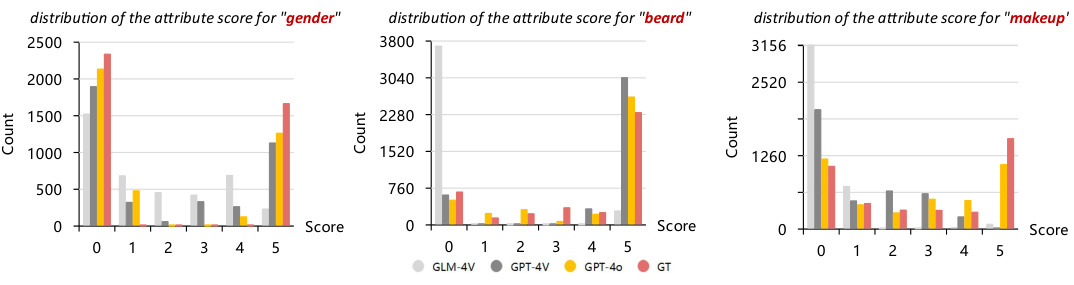

This figure shows the evaluation results of different MLLMs (GLM-4, GPT-4V, GPT-40) on attribute scoring accuracy for various attributes (Young, Gender, Hairline, Makeup, Chubby, Eyebag, Mustache, Beard, Hat, Bald, Glasses, Blond, Lipstick, Sideburn, Bangs, Eyebrows). The average accuracy and zero-scoring rate (percentage of attributes with zero scores) are shown for each MLLM, indicating their performance in attribute scoring. GPT-40 shows the best performance in terms of both average accuracy (88.4%) and a minimal zero-scoring rate (0.025%).

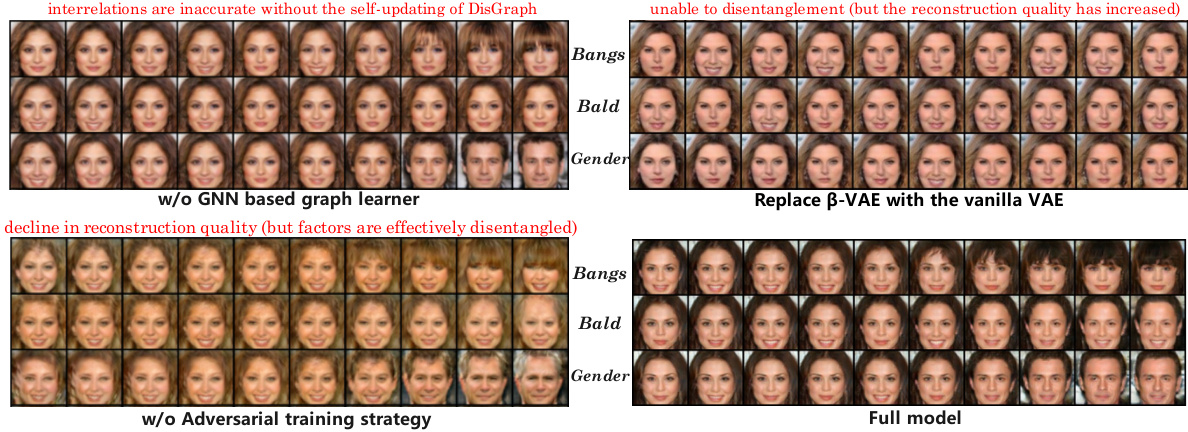

This ablation study investigates the effects of removing or replacing key components in the GEM model. The top two rows demonstrate the impact of removing the GNN-based graph learner and replacing the B-VAE with the vanilla VAE. The bottom two rows compare the full GEM model with a version that excludes the adversarial training strategy. The results illustrate the contributions of each component in achieving fine-grained and relation-aware disentanglement.

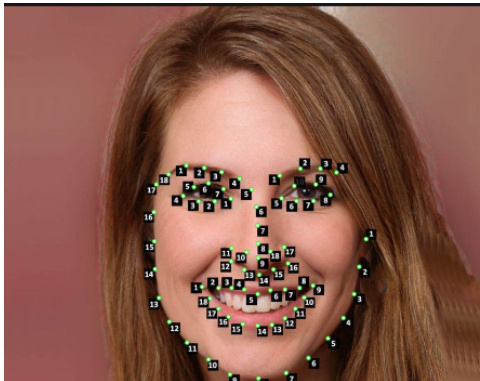

This figure shows an example of the 68-point landmark detection pre-processing step used in the GEM model. The image displays a face with 68 key points identified and numbered, marking locations such as jawline, eyebrows, nose, eyes, and lips. This pre-processing step helps to refine and crop the input image before feeding it into the B-VAE based attribute determining branch.

This figure compares traditional disentangled representation learning (DRL) frameworks with the proposed GEM framework. The left side highlights limitations of conventional methods, such as ignoring logical relations between factors and relying on unrealistic assumptions. The right side showcases GEM’s advantages, particularly its use of bidirectional weighted graphs and multimodal large language models (MLLMs) to capture complex data relationships and improve interpretability.

This figure compares the qualitative disentanglement results of GEM with FactorVAE and DEAR on the CelebA dataset. It shows traversals across different latent dimensions for six facial attributes (Bangs, Bald, Gender, Beard, Blond, Makeup), visualizing how changes in each latent dimension affect the corresponding attribute. The heatmap illustrates the bidirectional relations between attributes discovered by GEM using MLLMs, highlighting GEM’s superior performance in fine-grained disentanglement and capturing practical inter-attribute relationships.

This figure compares the qualitative results of GEM with FactorVAE and DEAR on the CelebA dataset. It shows traversals across various latent dimensions for six fine-grained facial attributes (Bangs, Bald, Gender, Beard, Blond, Makeup). Each row represents a traversal along a specific attribute’s latent dimension. The results illustrate GEM’s superior ability to achieve fine-grained disentanglement and capture practical bidirectional relations between attributes, as visualized in the heatmap showing correlation coefficients.

This figure shows the reconstruction results of the LSUN-bedroom dataset using the GEM model. It visually demonstrates the model’s ability to reconstruct images from the LSUN-bedroom dataset, showcasing its performance on a real-world, complex dataset with diverse and varied bedroom scenes. The image grid displays a selection of the input images alongside their corresponding reconstructions generated by GEM.

This figure shows the reconstruction results of the LSUN-horse dataset using the GEM model. It visually demonstrates the model’s ability to reconstruct images from the LSUN-horse dataset, showcasing its performance on a different dataset than CelebA, highlighting its generalizability. The images are arranged in a grid, allowing for a visual comparison of the original and reconstructed images.

This figure compares the qualitative results of GEM with FactorVAE and DEAR on CelebA dataset. It shows traversals across different latent dimensions for six facial attributes: bangs, bald, gender, beard, blond, and makeup. The results demonstrate GEM’s superior ability to achieve fine-grained disentanglement, capturing both the individual attributes and their bidirectional relationships (shown in the heatmap). FactorVAE and DEAR show limitations in capturing fine-grained detail and relationships.

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of the computational efficiency of four different models: FactorVAE, DEAR, GEM (Single), and GEM (Full). The comparison is made across four metrics: the number of parameters (Params), the number of floating-point operations (GFLOPS), the memory cost (Mem), and the training time (TT). GEM (Single) refers to the GEM model without the relation discovery module. GEM (Full) represents the full GEM model including the relation discovery module. The results show the relative computational efficiency of each model, offering insights into their practical applicability based on resource constraints.

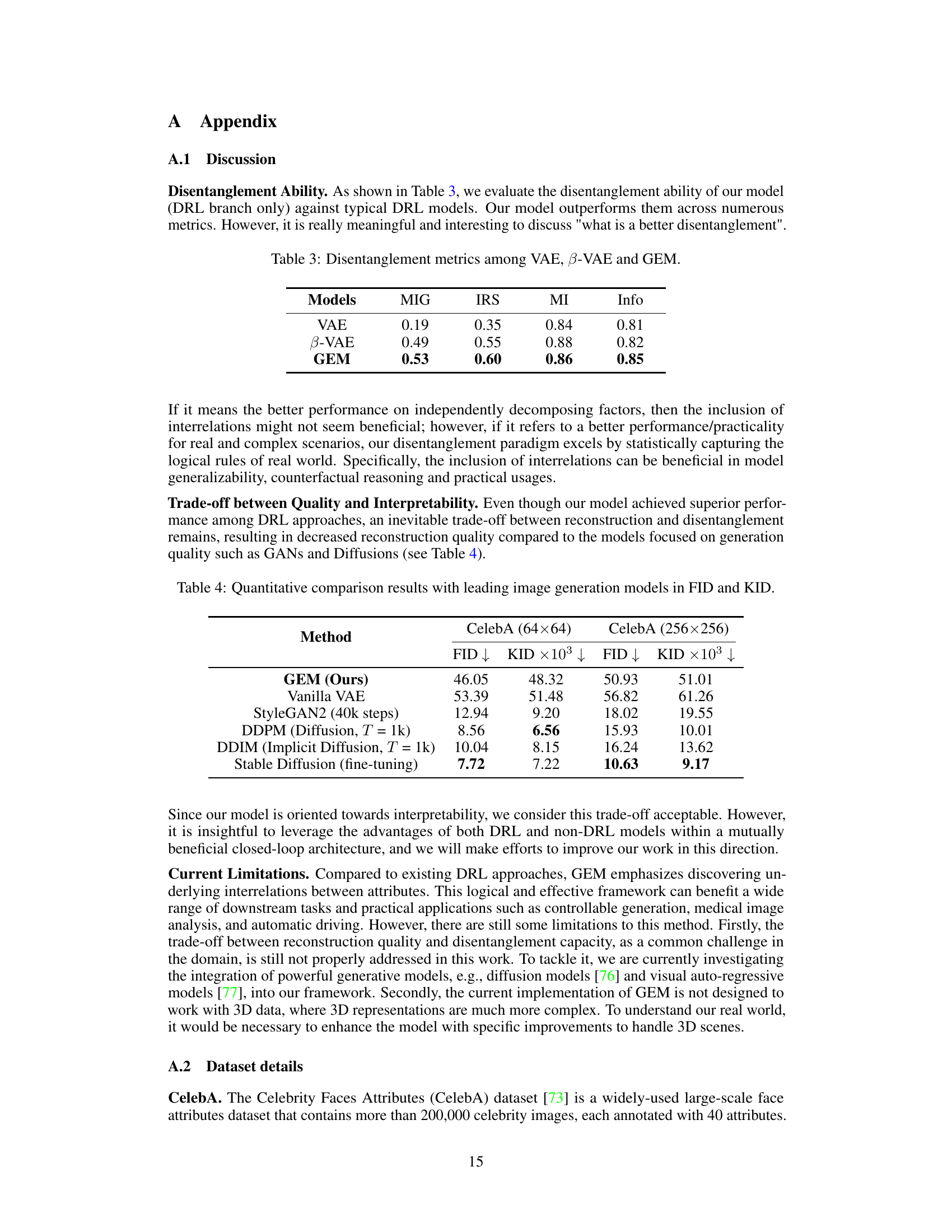

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the disentanglement performance of three different models: VAE, β-VAE, and the proposed GEM model. Four metrics are used to evaluate disentanglement: Mutual Information Gap (MIG), Inter-representation Similarity (IRS), Mutual Information (MI), and total Information (Info). Higher scores generally indicate better disentanglement. The results show that GEM outperforms both VAE and β-VAE across all four metrics.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the GEM model’s performance against several state-of-the-art Deep Representation Learning (DRL) approaches. The comparison is based on two metrics: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Kernel Inception Distance (KID). Lower FID and KID scores indicate better reconstruction quality. The table includes results for three datasets: CelebA, LSUN-horse, and LSUN-bedroom, providing a comprehensive evaluation across different image types and complexities.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed GEM model with several other state-of-the-art DRL approaches, using two metrics: Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Kernel Inception Distance (KID). Lower FID and KID scores indicate better reconstruction quality. The results are shown for three datasets: CelebA, LSUN-horse, and LSUN-bedroom.

Full paper#