↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Accurately reconstructing the 3D shape of garments, especially when they are folded or crumpled (not worn), is a significant challenge in computer vision. Existing methods often assume garments are worn, limiting their applicability to a wider range of scenarios. This constraint significantly reduces the possible shapes and makes reconstruction more difficult. The presence of self-occlusions further complicates the process.

This work introduces a novel method that overcomes these limitations. By combining implicit sewing patterns (ISP) with diffusion-based deformation priors and employing a UV mapping technique, this method accurately reconstructs 3D garment shapes from incomplete 3D point clouds. The method demonstrates superior performance compared to existing approaches, particularly when dealing with highly deformed garments. This is achieved without requiring prior knowledge of the garment geometry, improving its applicability to real-world scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the challenge of 3D garment reconstruction when garments are manipulated, a problem that existing methods struggle with. The novel approach uses diffusion models and implicit sewing patterns, offering superior accuracy, especially for complex deformations. This opens new avenues for research in virtual try-on, VR/AR, and robotic manipulation.

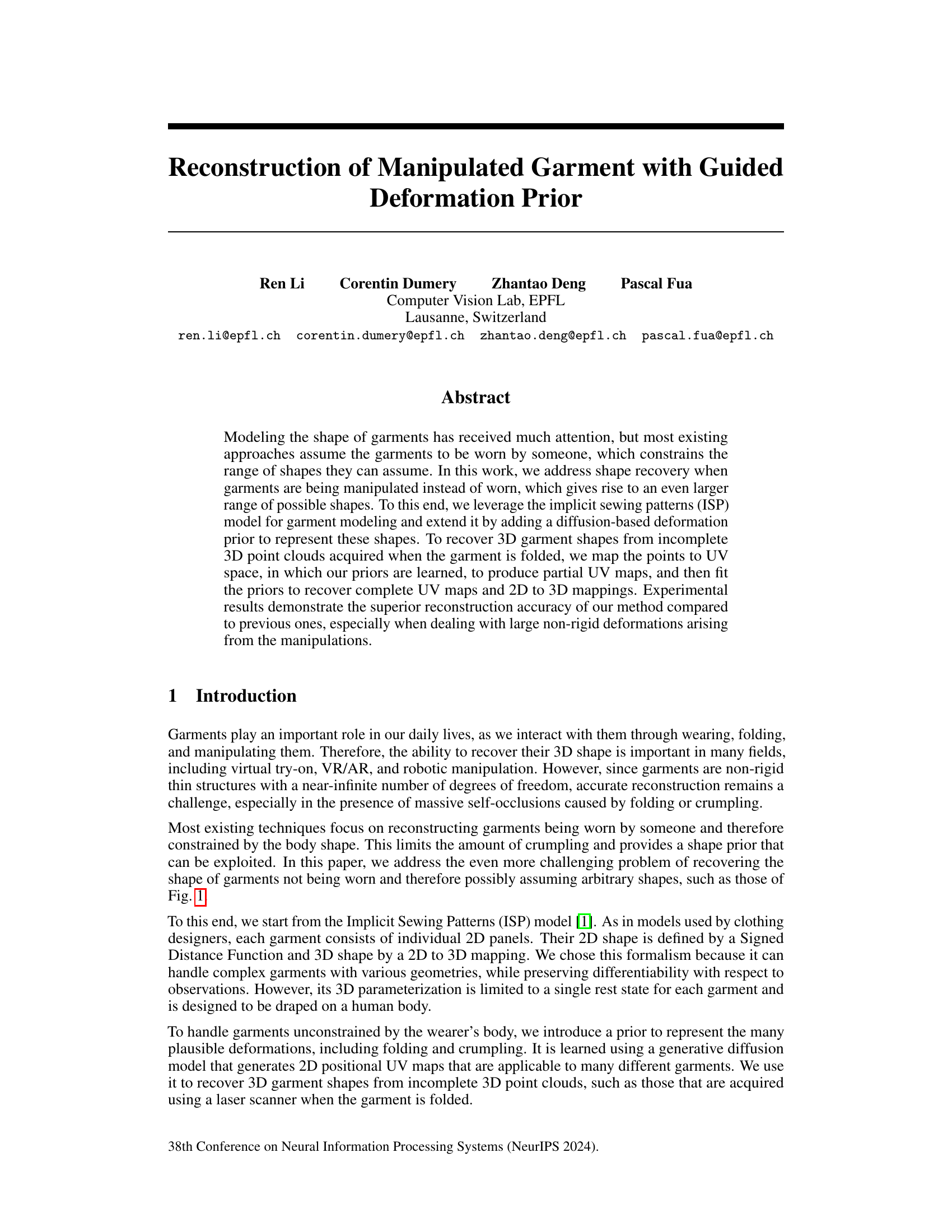

Visual Insights#

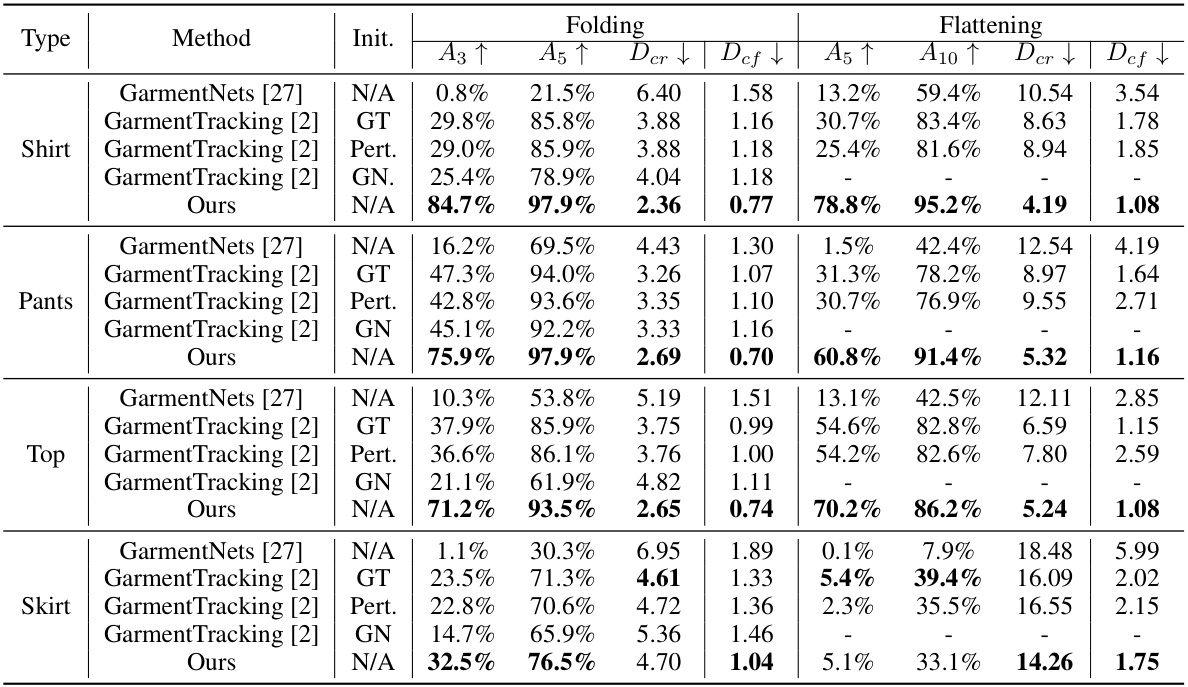

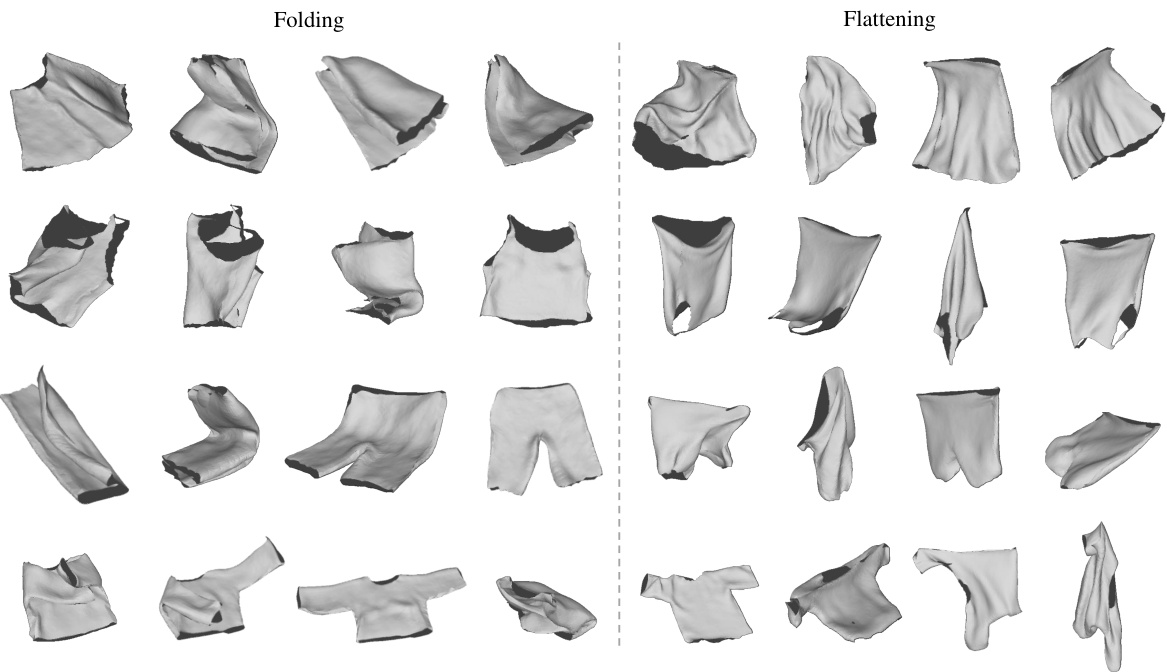

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the proposed method against the GarmentTracking method. GarmentTracking uses the ground truth mesh as initialization. The figure displays the results for sequences of garment folding and flattening operations, illustrating the superior reconstruction accuracy and detail preservation of the proposed method compared to GarmentTracking across various manipulation stages. The top row showcases the input point clouds (green) overlaid on the ground truth meshes (gray). The bottom row presents the reconstruction results from the proposed method. The visual comparison highlights the ability of the novel approach to faithfully recover garment meshes from incomplete point cloud data, accurately capturing complex shape deformations and self-occlusions that are not well-represented by GarmentTracking.

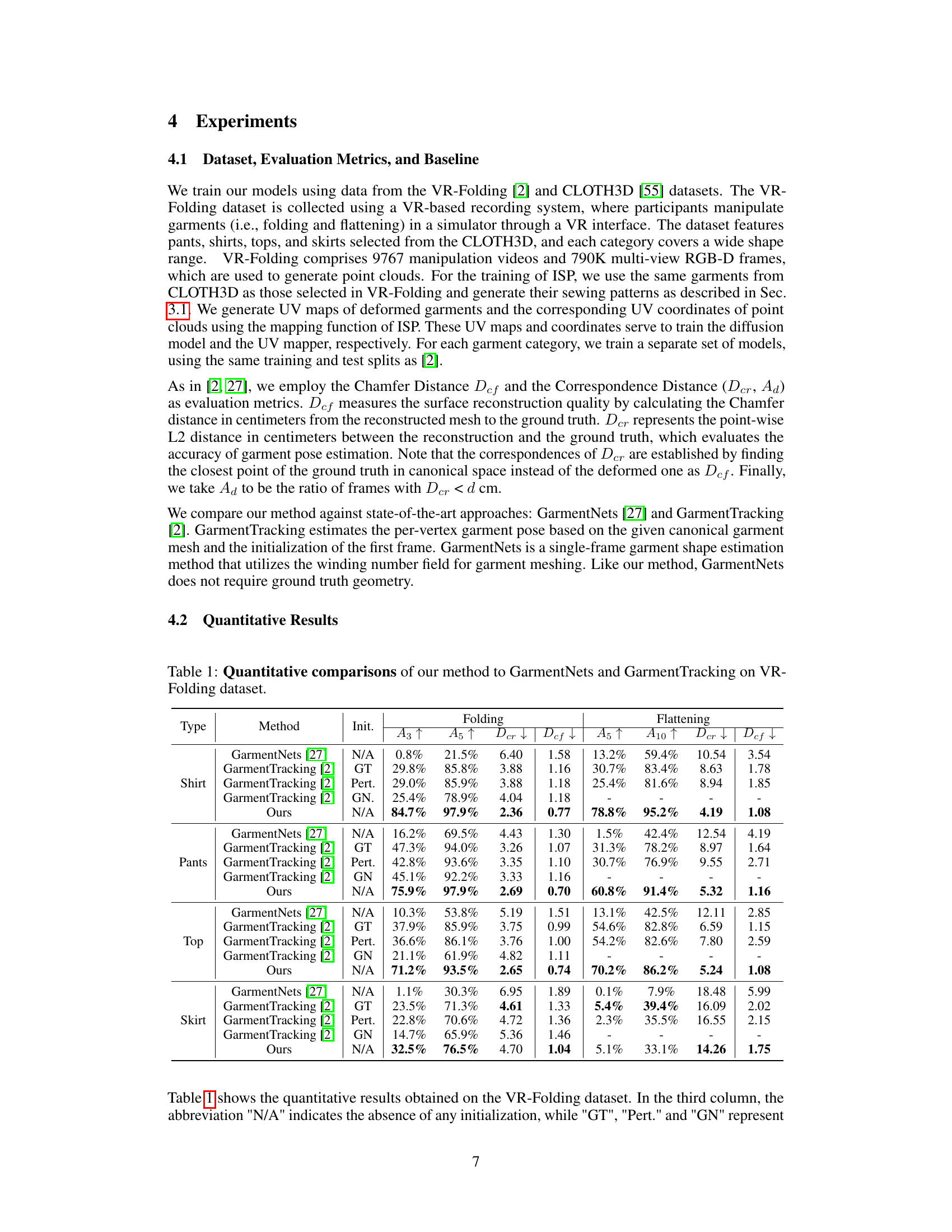

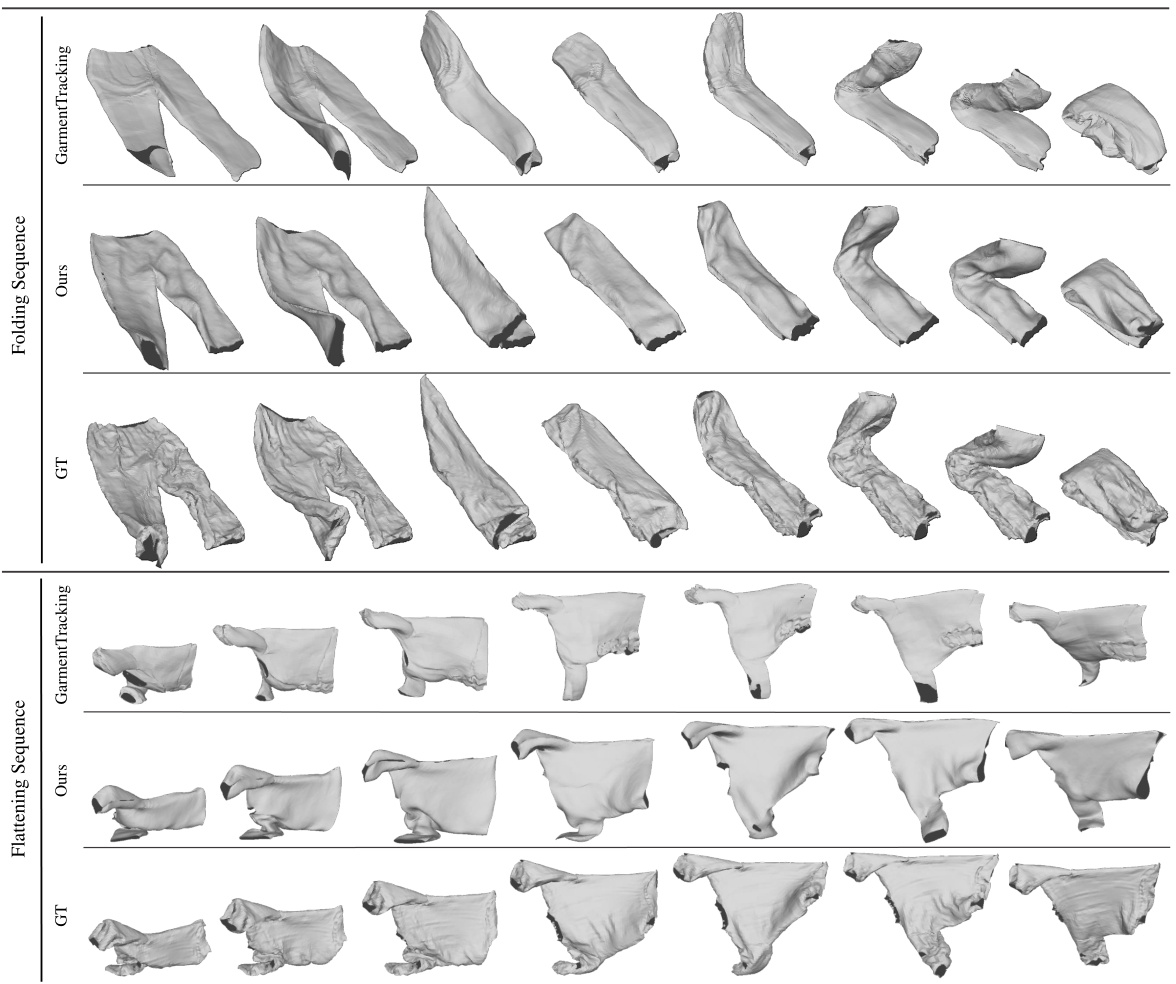

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against two state-of-the-art approaches, GarmentNets and GarmentTracking, using the VR-Folding dataset. The comparison is done across different garment types (Shirt, Pants, Top, Skirt) and manipulation types (Folding, Flattening). Metrics used include Chamfer Distance (Def), Correspondence Distance (Der), and the percentage of frames where Der is below a certain threshold (A5 and A10). The ‘Init.’ column indicates the type of initialization used for the comparison methods. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method in terms of reconstruction accuracy and pose estimation.

In-depth insights#

Deformation Priors#

Deformation priors are crucial for accurate garment reconstruction, especially when dealing with manipulated garments exhibiting complex folds and wrinkles. Existing methods often rely on body shape constraints, limiting their applicability to freely manipulated clothes. This paper addresses this limitation by introducing a diffusion-based deformation prior trained on a diverse range of garment shapes, enabling the model to handle arbitrary deformations. The effectiveness of this approach lies in its ability to capture the complex distribution of plausible deformations, representing the variety of shapes a garment can assume when not worn on a body. This technique extends the Implicit Sewing Pattern model, leading to significantly improved reconstruction accuracy, particularly in scenarios with severe self-occlusions and large deformations. The use of a learned prior, as opposed to physics simulation or relying on templates, makes the approach more adaptable and robust, paving the way for more versatile garment reconstruction systems.

Diffusion Models#

Diffusion models are a class of generative models that have shown impressive results in image generation. They work by iteratively adding noise to data until it becomes pure noise, then learning to reverse this process to generate new data samples. This approach is powerful because it avoids the need for adversarial training, often leading to improved sample quality and stability. Diffusion models excel at capturing complex data distributions, making them well-suited for tasks involving intricate details or diverse data modalities. However, they often require substantial computational resources, especially during training. The key innovation is the ability to reverse a diffusion process, thereby transforming random noise into structured data. This makes them very flexible and suitable for various applications like image generation, 3D model creation, and even language modeling.

ISP Garment Model#

The Implicit Sewing Patterns (ISP) garment model offers a novel approach to 3D garment modeling, drawing inspiration from traditional sewing patterns. Its core innovation lies in representing garments using a unified 2D UV space, where individual panels are defined. This allows for a more intuitive and flexible representation of complex garment shapes compared to traditional methods. The model uses a signed distance function (SDF) to define panel boundaries and a label field to encode stitching information, enabling seamless transitions between panels. The differentiability of the ISP model is a crucial advantage, facilitating the integration of this model with other differentiable components in the pipeline, such as a diffusion-based deformation prior. The training process, which involves flattening and unfolding garments to obtain 2D sewing patterns, while ensuring local area preservation, is another key aspect of the ISP model. This process enables the effective training of the model, despite the scarcity of readily available 2D sewing patterns. By leveraging both the 2D representation and 3D mapping functions, the ISP model provides a powerful framework for reconstructing and manipulating garments in 3D space, especially useful in situations where conventional methods struggle.

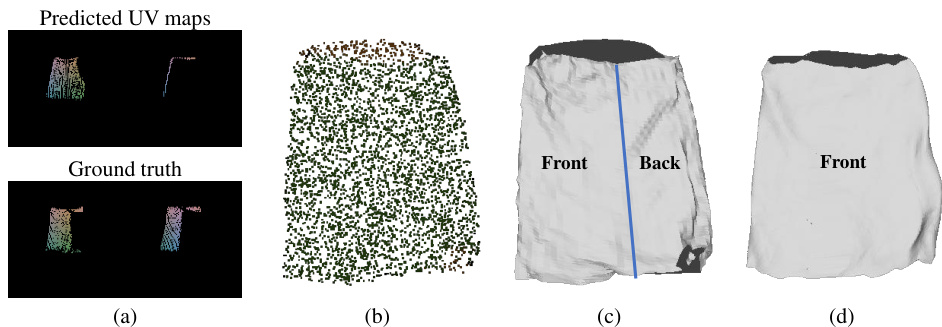

UV Mapping#

In 3D garment reconstruction, UV mapping is a crucial preprocessing step that transforms 3D point cloud data into a 2D parameter space. This transformation is essential because many garment modeling techniques, particularly those based on implicit sewing patterns, operate more effectively in 2D. By flattening the 3D garment representation into a 2D UV map, the model simplifies the complex 3D geometry, enabling more efficient processing and manipulation. A successful UV mapping approach must accurately map the 3D points to their corresponding UV coordinates, preserving geometric consistency and handling potential challenges like self-occlusions and non-uniform sampling. The accuracy of the UV mapping directly impacts the quality of the subsequent reconstruction and deformation modeling steps. Learning-based methods can be employed to effectively map point clouds to UV space, especially when dealing with large non-rigid deformations or incomplete point cloud data. The effectiveness of the UV mapper has a direct impact on the final accuracy and detail in the reconstructed garment model, thus making UV mapping a crucial part of the proposed method.

Real-world Tests#

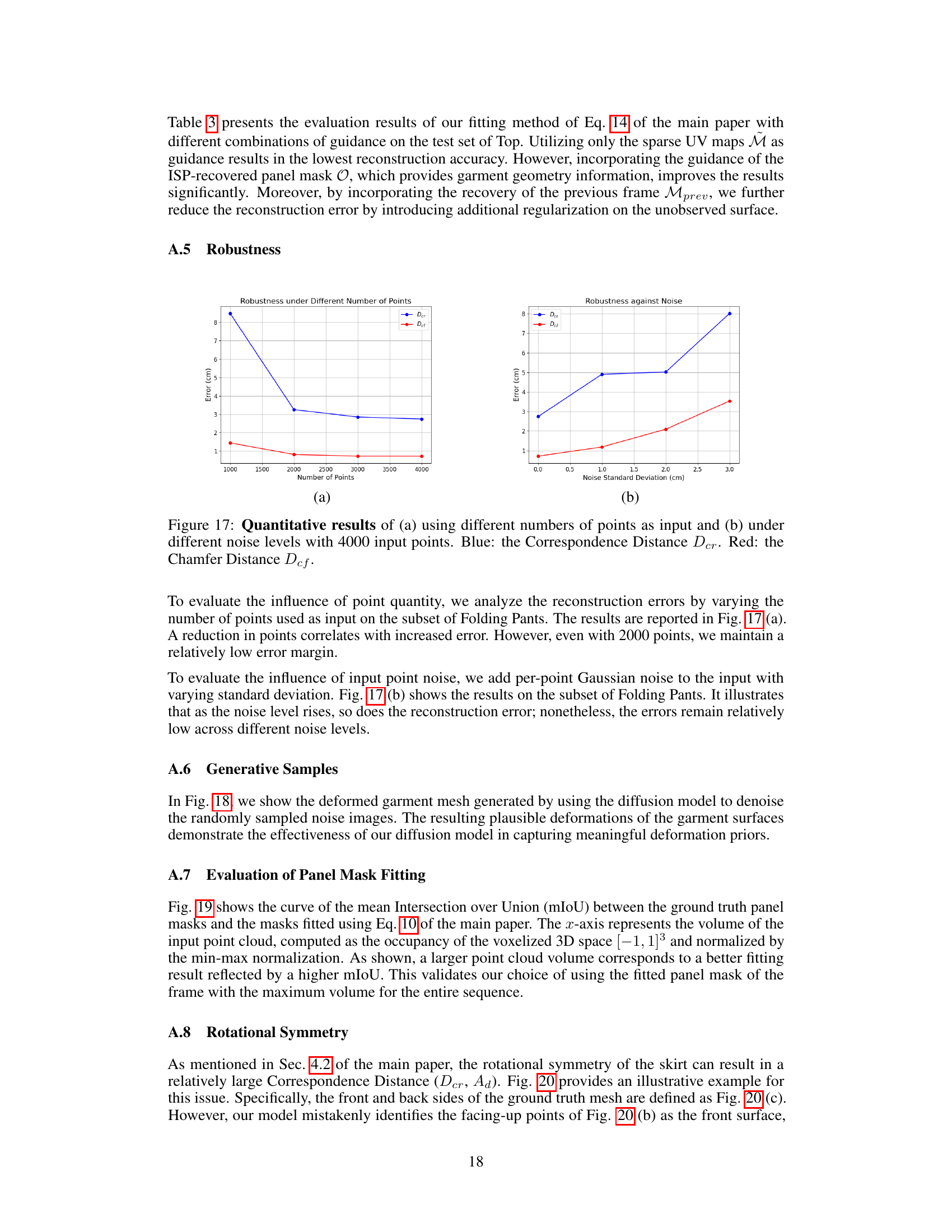

A dedicated ‘Real-world Tests’ section in a research paper would strengthen its impact significantly. It should go beyond simple demonstrations and delve into the practical applicability of the method. This section would ideally include results from diverse, unconstrained environments. Comparisons to existing methods on this data would be crucial, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed approach under real-world conditions. Discussion of challenges encountered during real-world testing – such as noise, occlusions, or variations in lighting – should be transparently addressed, showcasing the robustness of the method. Qualitative analysis of results, accompanied by visualizations, would make the findings more accessible and compelling. It’s vital to analyze whether the algorithm’s performance degrades significantly, and to discuss any unexpected behavior observed in real-world scenarios. Finally, a critical discussion of the algorithm’s limitations in real-world settings, and its potential for further improvement, is crucial for a complete and convincing evaluation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

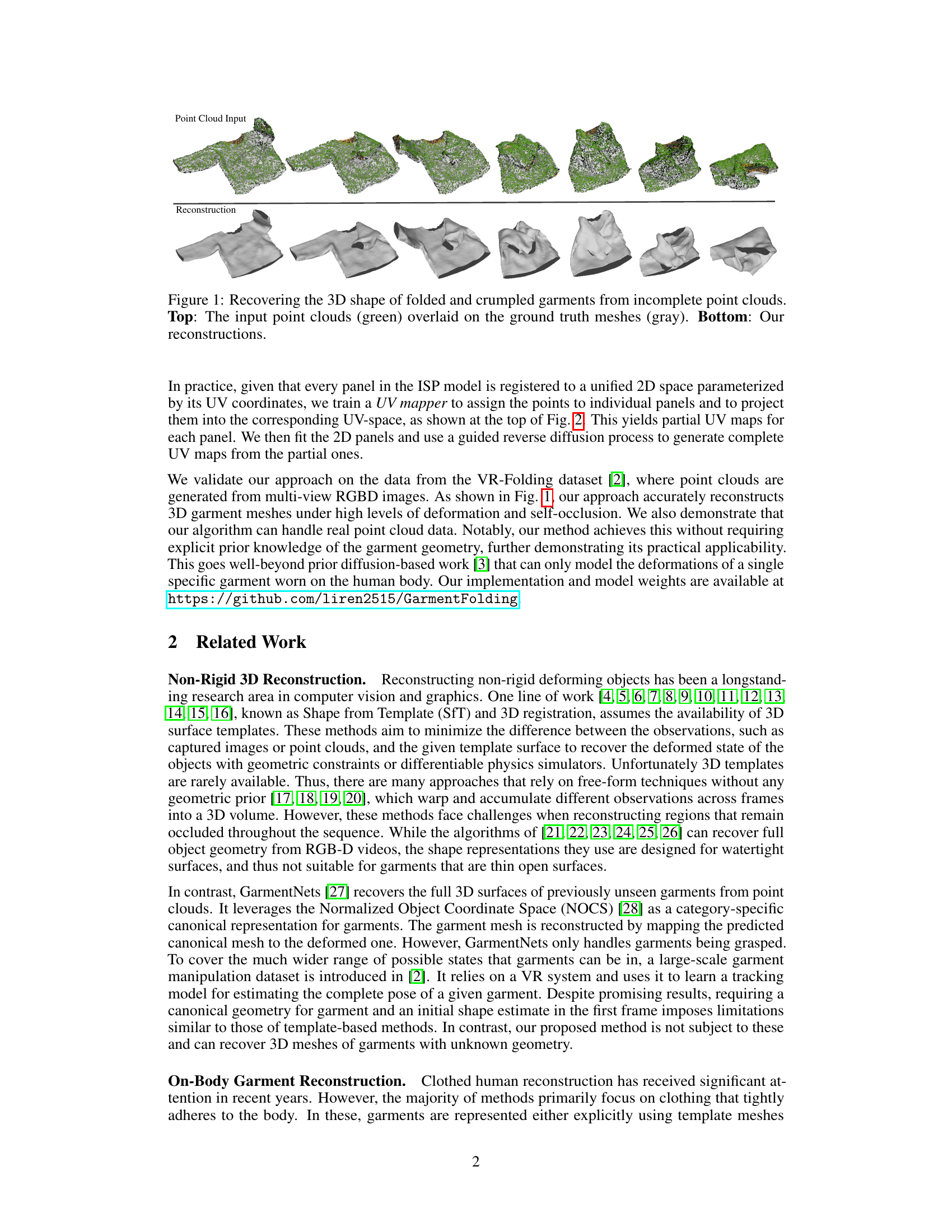

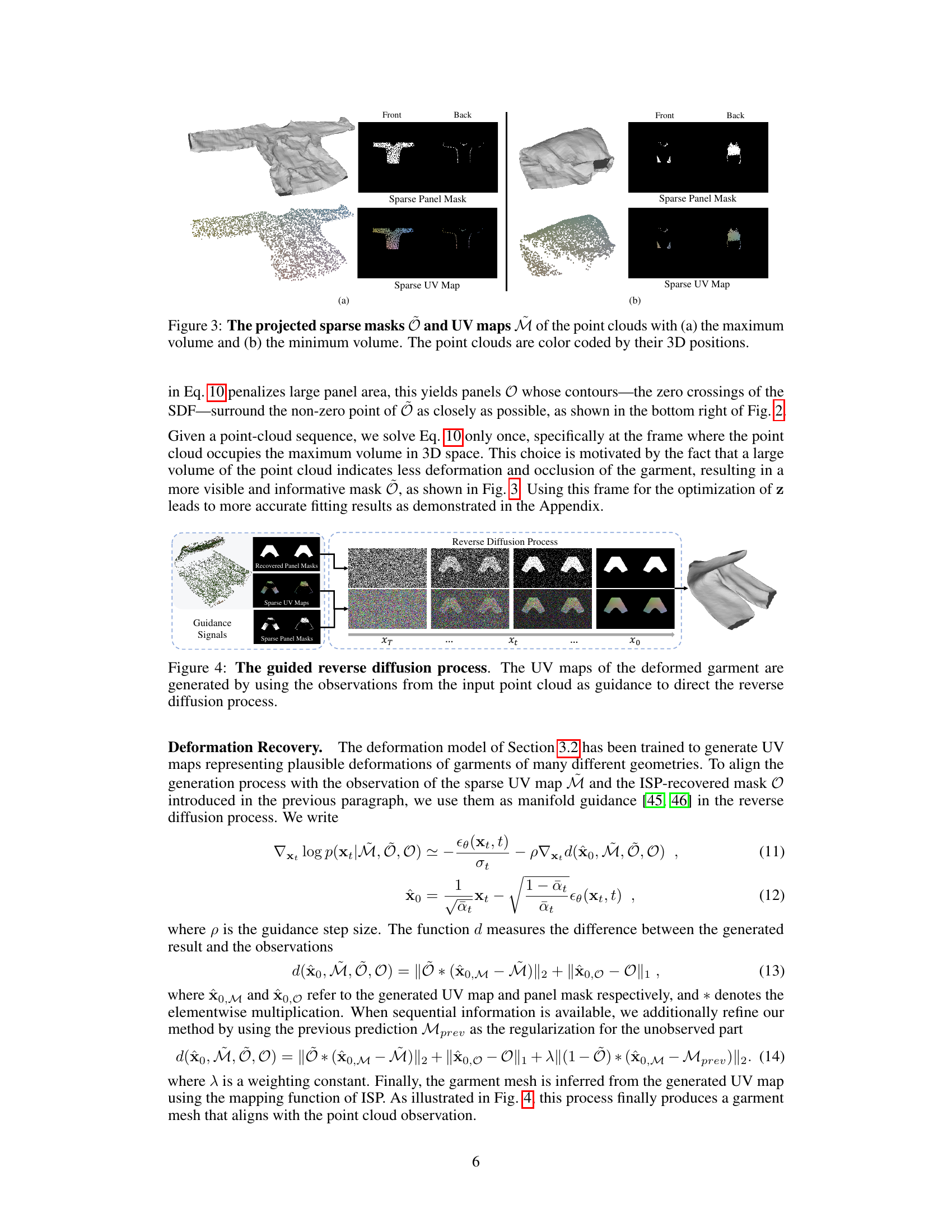

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the proposed method. It starts by mapping a partial point cloud of a garment to UV space using a trained UV mapper. This results in sparse UV maps and panel masks. Then, it recovers complete UV maps and panel masks by fitting the Implicit Sewing Patterns (ISP) model and incorporating a learned deformation prior (a diffusion model). Finally, it reconstructs the complete 3D mesh of the garment using the recovered UV maps and panel masks. The deformation prior is crucial for handling garments that are not worn and can assume arbitrary shapes.

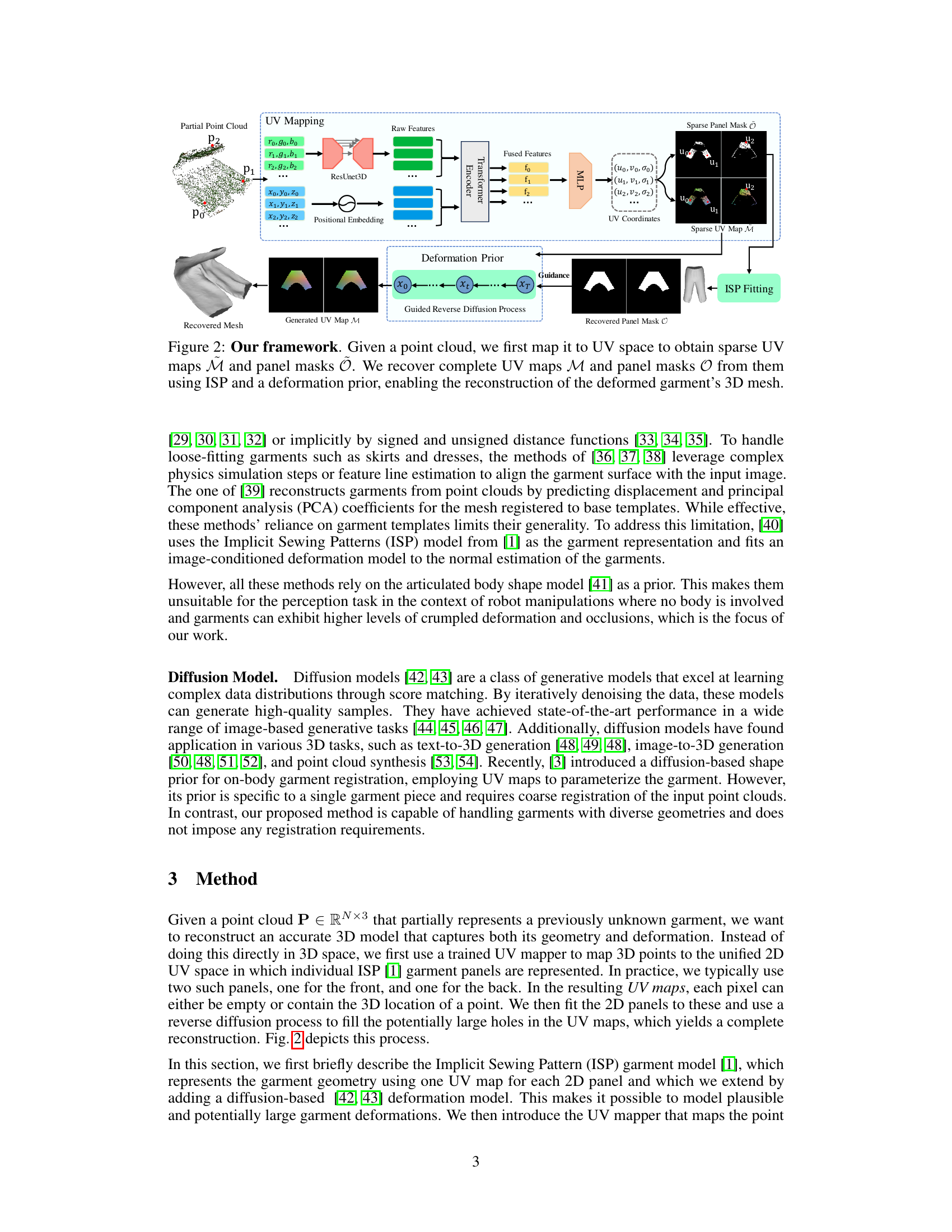

This figure shows the sparse masks and UV maps generated from point clouds with maximum and minimum volumes. The point clouds are color-coded to indicate their 3D positions, providing visual context for the sparsity and distribution of the projected data in UV space. It illustrates the input data to the reconstruction pipeline, highlighting the challenges of working with incomplete point cloud data.

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the proposed method. It starts with a point cloud of a garment. The point cloud is then mapped into UV space using a trained UV mapper, resulting in sparse UV maps and panel masks. These sparse representations are then used as input to a reverse diffusion process guided by the learned deformation prior and Implicit Sewing Patterns (ISP) model. This process generates complete UV maps and panel masks. Finally, a 3D mesh of the garment is reconstructed using the ISP model.

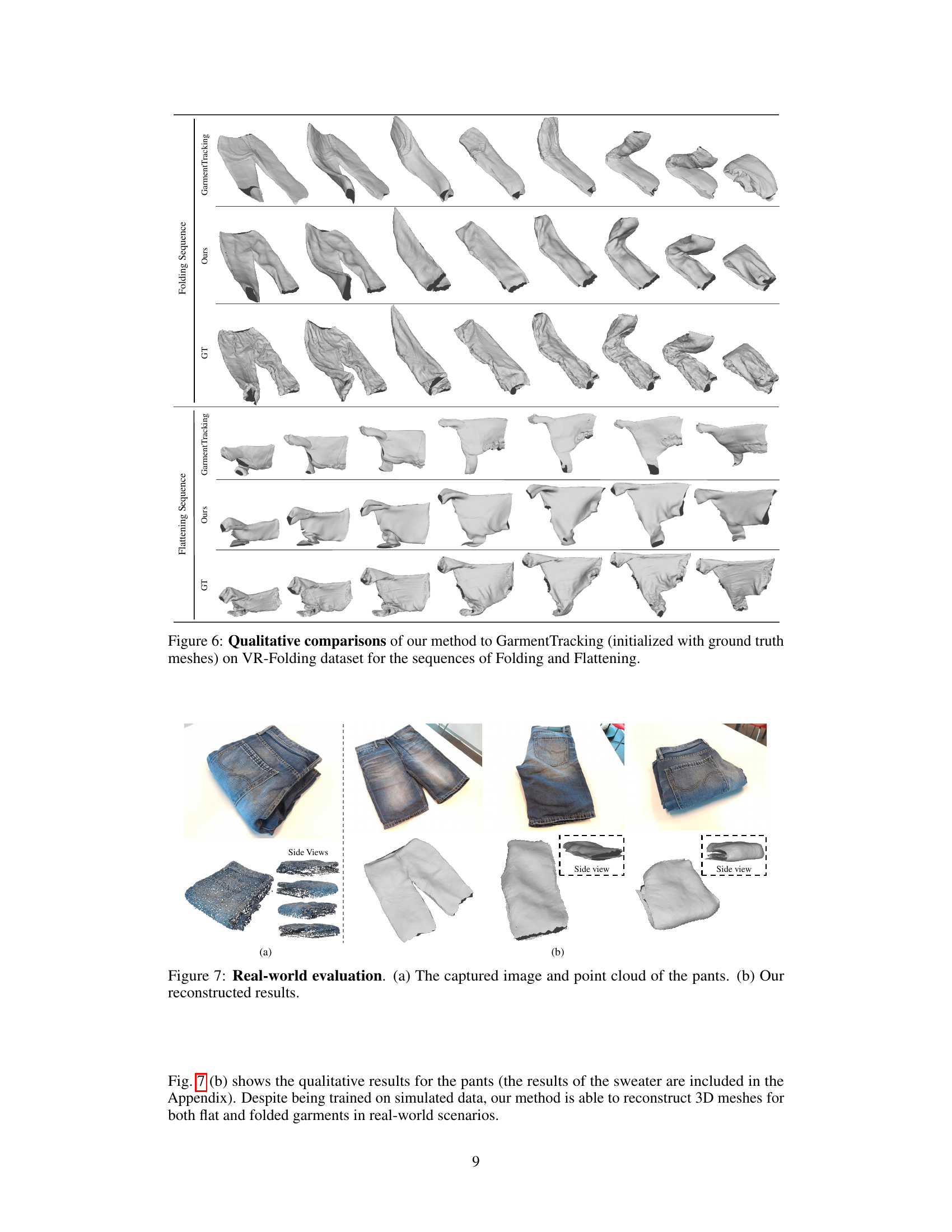

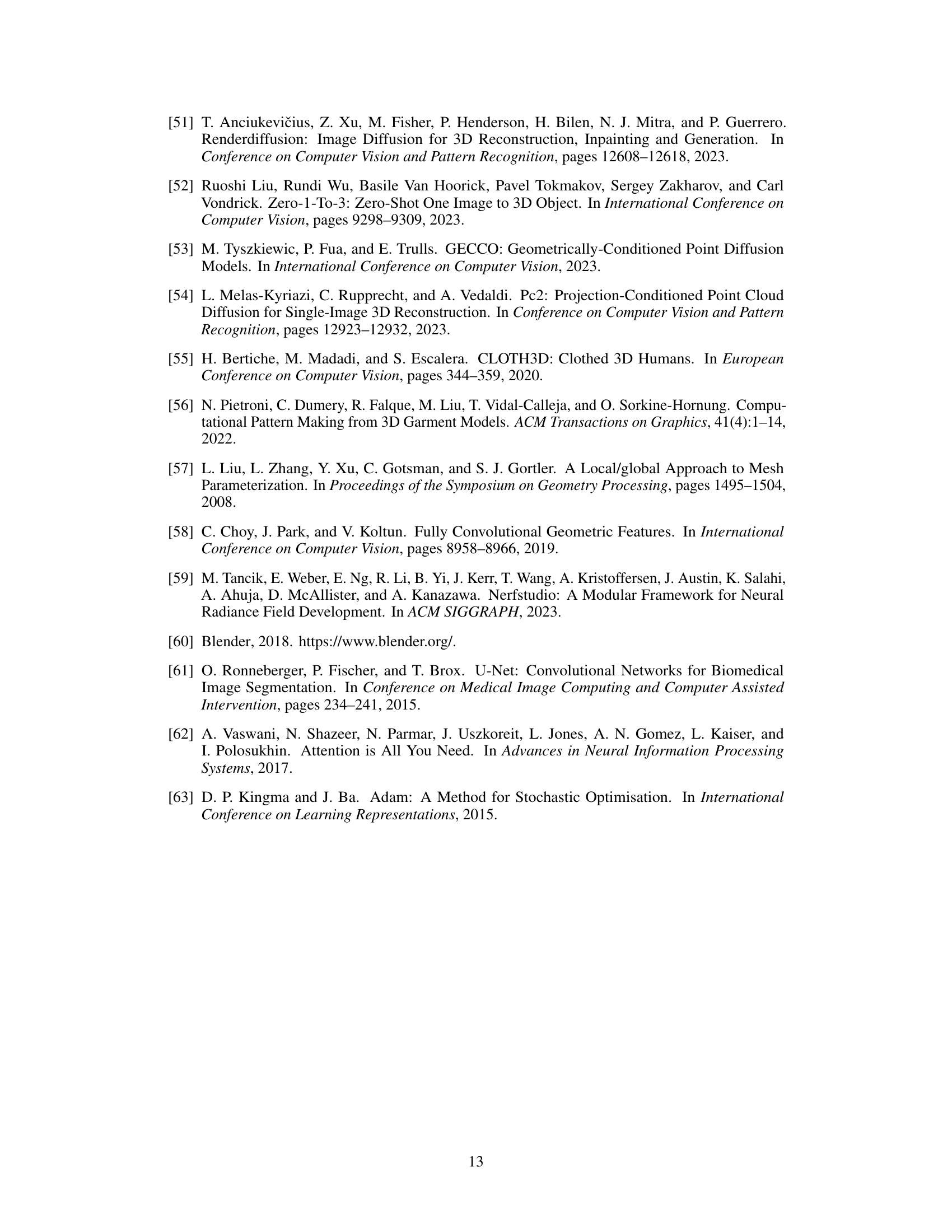

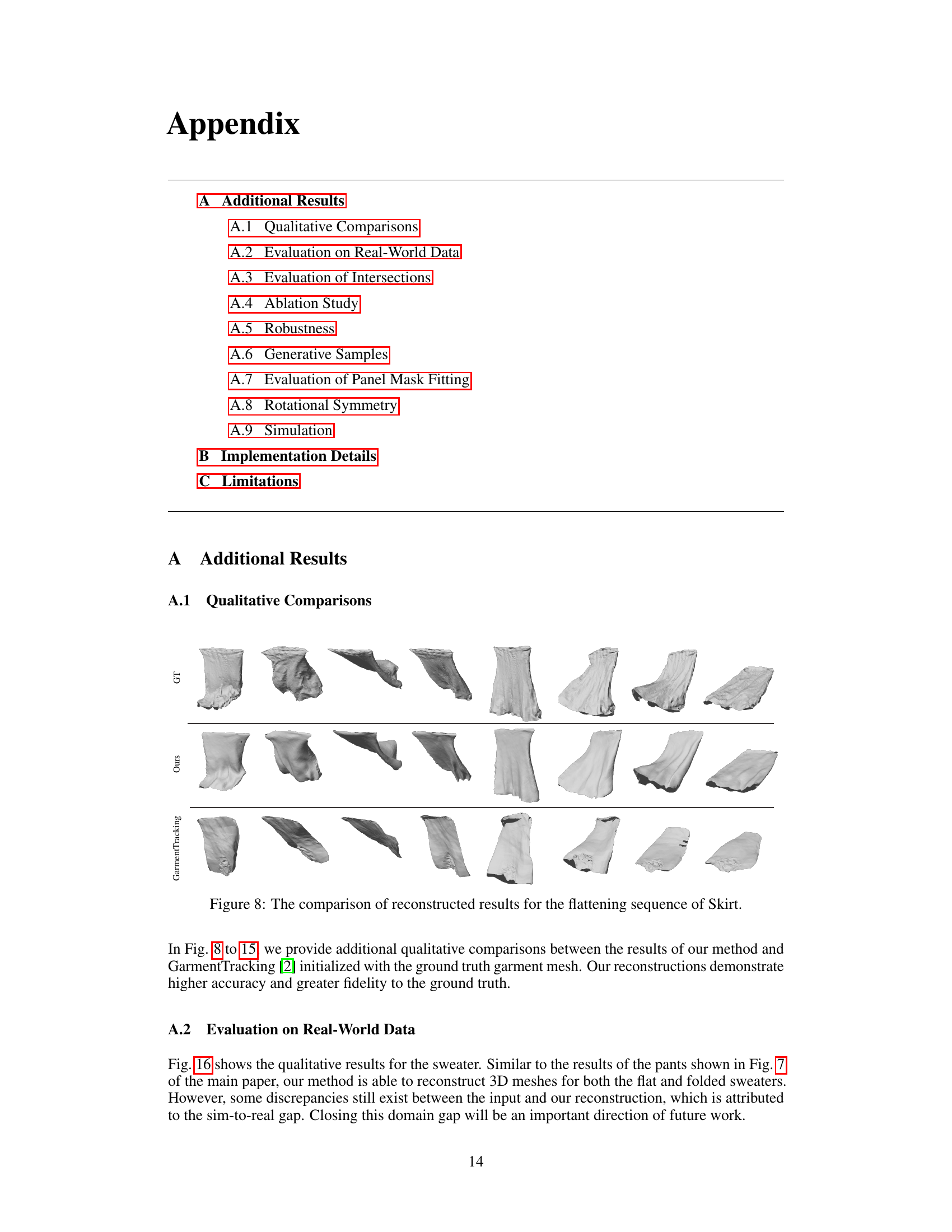

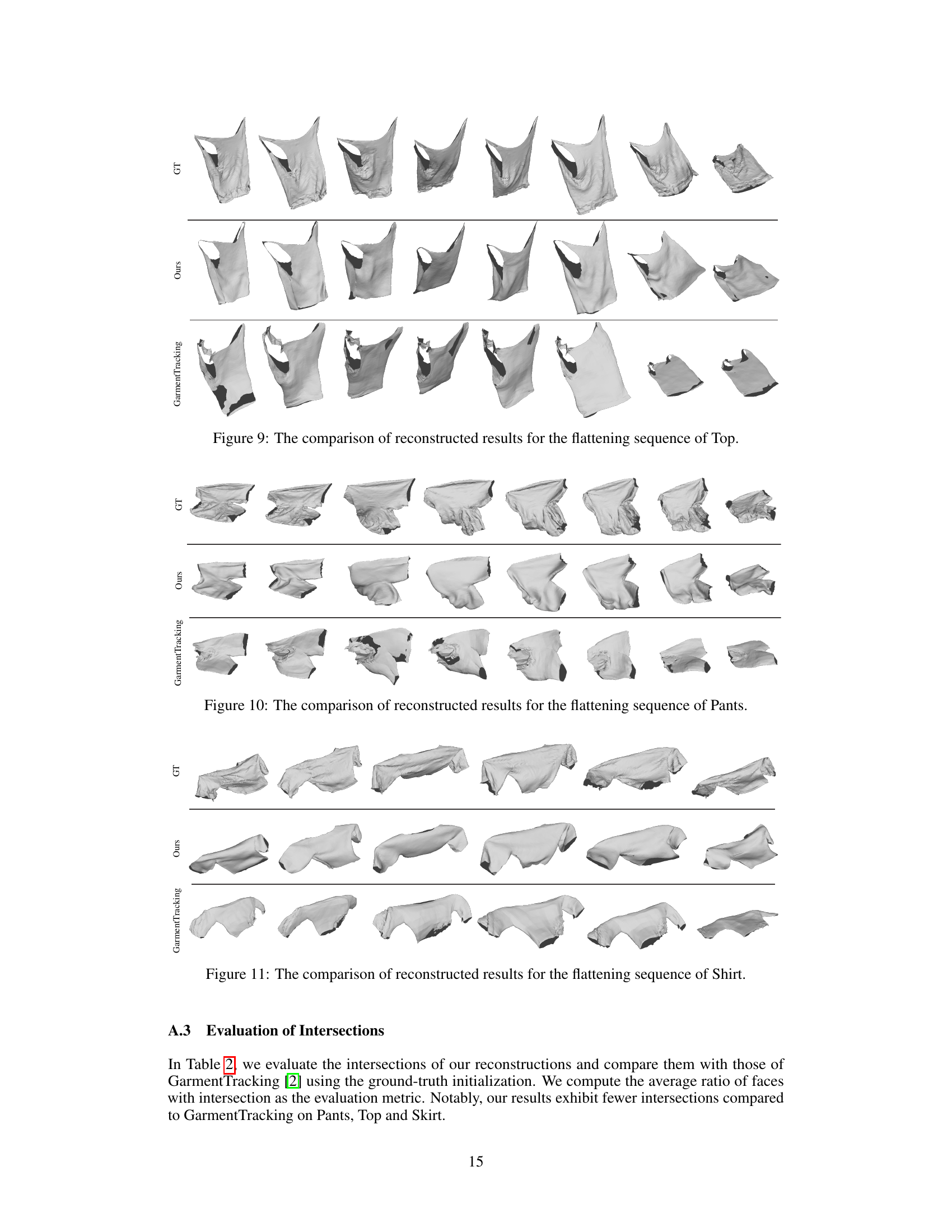

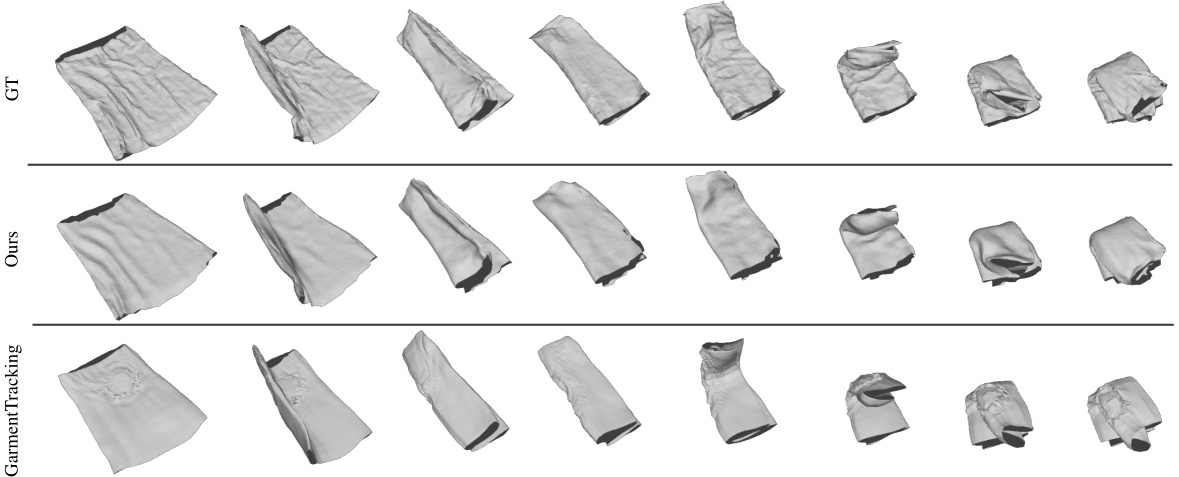

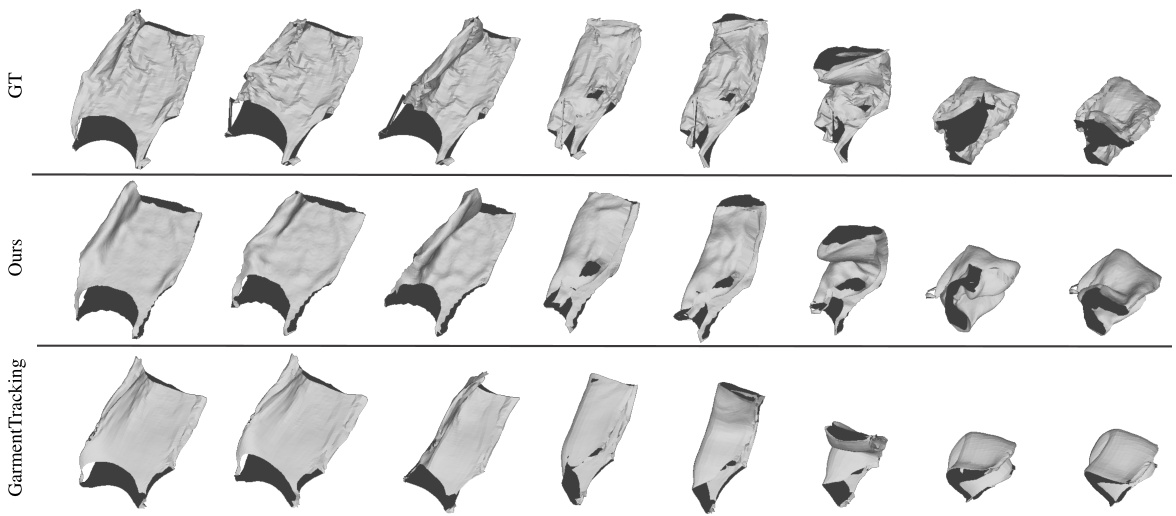

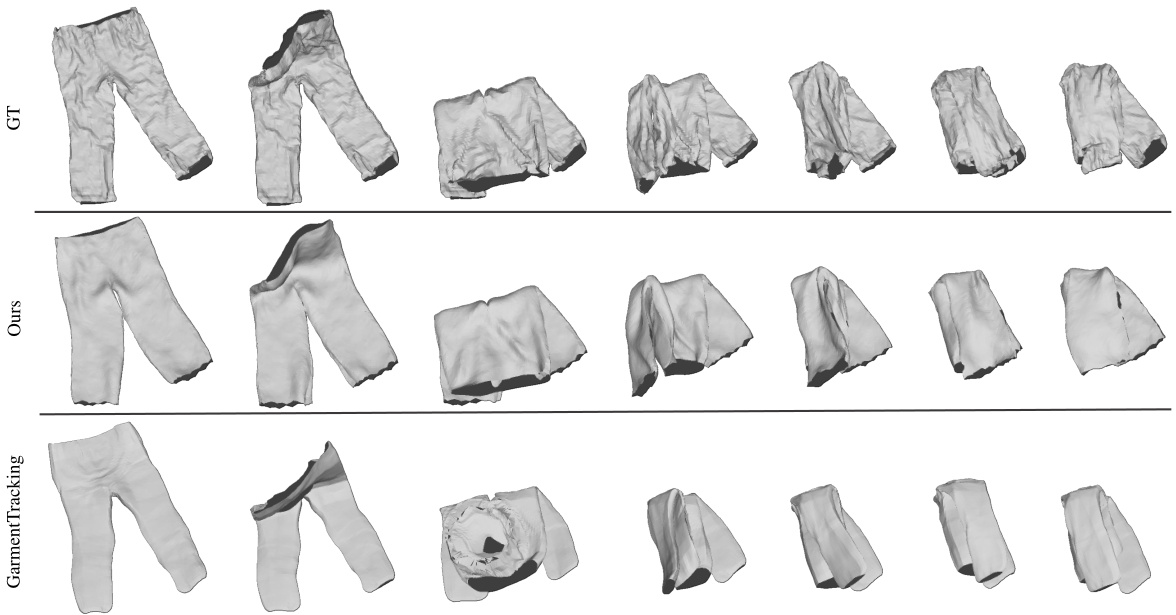

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the proposed method’s garment reconstruction results against those from GarmentTracking, a state-of-the-art method that leverages the ground truth garment mesh as initialization. The comparison is presented for both folding and flattening sequences across four garment categories: pants, tops, shirts, and skirts. For each category and sequence type, input point clouds, ground truth meshes, results from the proposed method, and results from GarmentTracking are displayed. This allows for a visual assessment of the accuracy and detail captured by the different methods in handling various levels of deformation and self-occlusion. The visual comparison supplements the quantitative results presented in the paper, providing further insights into the method’s strengths and limitations.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison between the results of the proposed method and GarmentTracking [2] (initialized with ground truth meshes). The top two rows display results for the ‘Folding’ sequence, and the bottom two rows display results for the ‘Flattening’ sequence. Each row shows results for a specific garment type. The results of GarmentTracking, the proposed method, and the ground truth are shown for comparison.

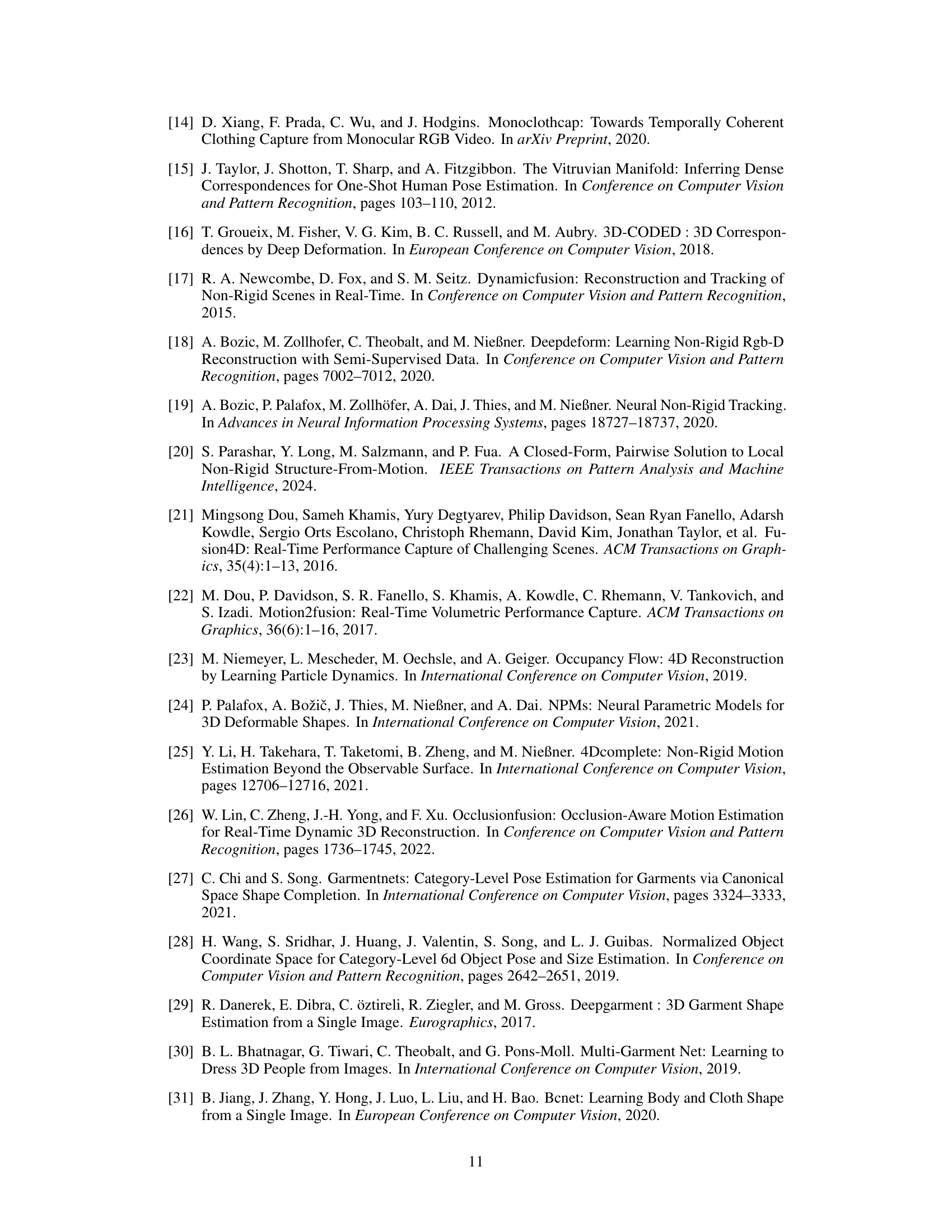

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed method to real-world data. Part (a) displays the input: a captured image and the corresponding point cloud of a pair of pants in different folded configurations. Part (b) presents the 3D reconstruction results generated by the algorithm, demonstrating its ability to reconstruct the shape of real-world garments from captured point clouds. The results visualize the model’s performance in reconstructing the geometry and folds of the pants, even with real-world challenges such as varying lighting and complex folds.

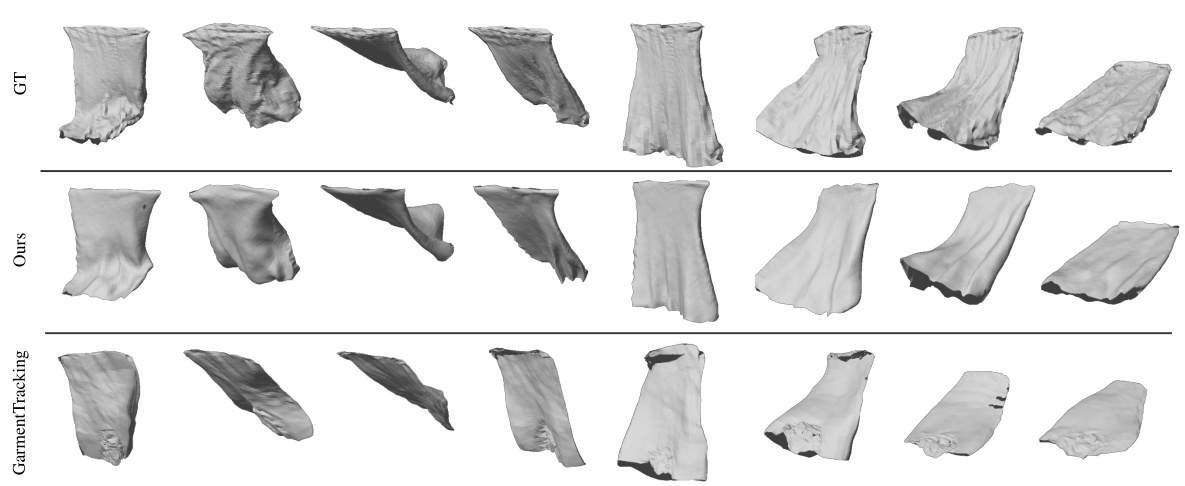

This figure displays a qualitative comparison of the 3D garment reconstruction results for a skirt undergoing a folding sequence. It shows the ground truth model (GT), the results obtained using the proposed method (Ours), and the results obtained using the GarmentTracking method (GarmentTracking). By visually comparing the three sets of reconstructed skirt models, the differences in accuracy and detail between the methods can be observed. The figure illustrates the ability of the proposed approach to accurately reconstruct the complex shapes and folds of a manipulated garment compared to an existing method.

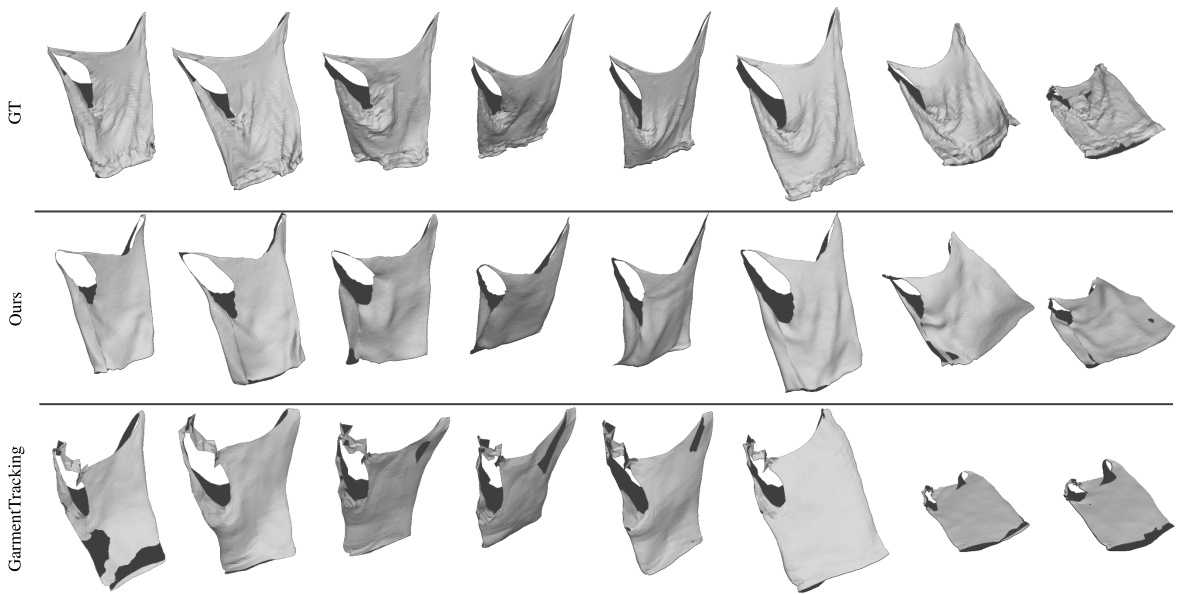

This figure displays a qualitative comparison of the 3D garment reconstruction results obtained using three different methods: the proposed method, GarmentTracking (initialized with ground truth), and the ground truth itself. The comparison is shown for both ‘Folding’ and ‘Flattening’ sequences of garment manipulations, visualizing the accuracy and realism of the different approaches in handling complex deformations and self-occlusions. The results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed method in capturing accurate shapes and deformations compared to GarmentTracking.

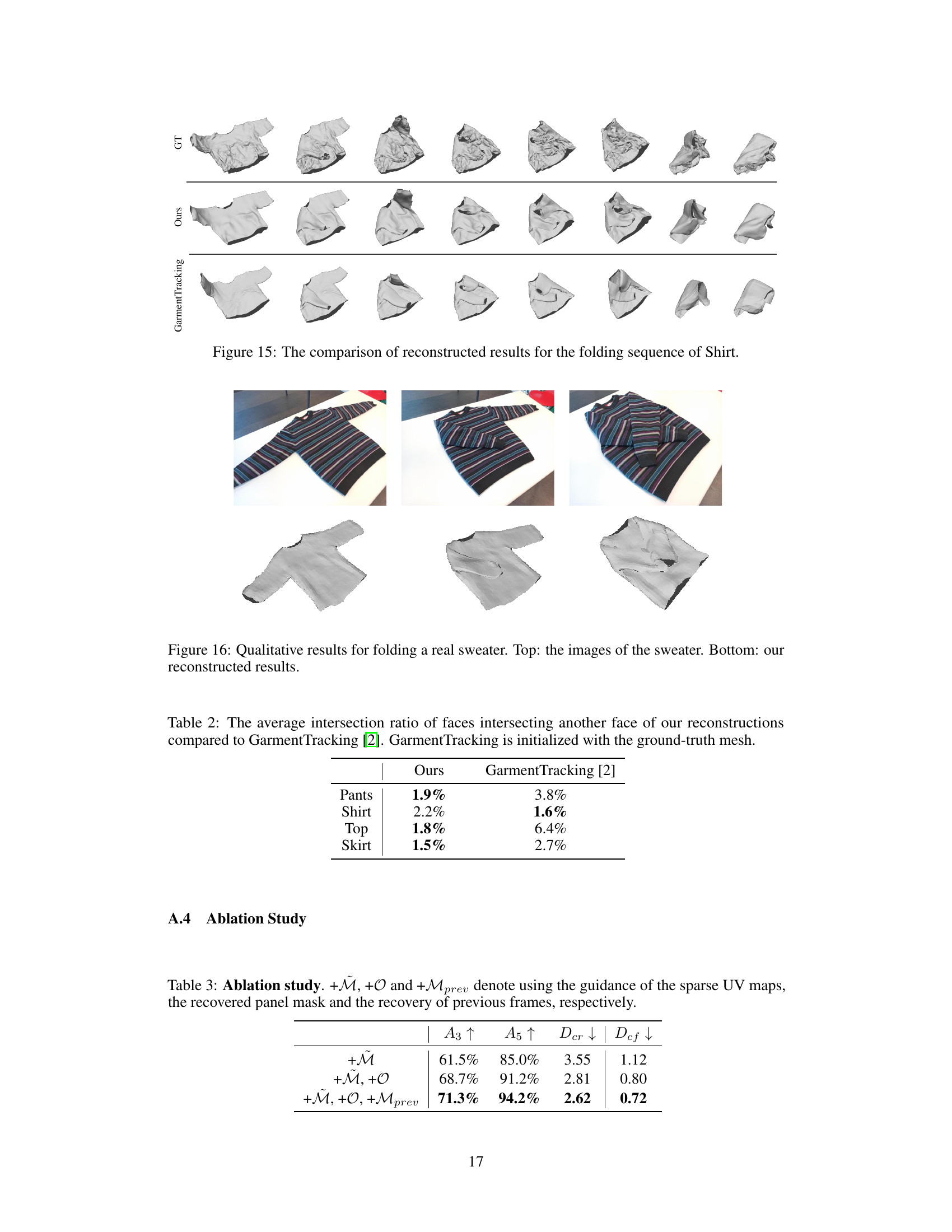

This figure compares the 3D garment reconstruction results of the proposed method with those of the GarmentTracking method, using ground truth meshes as initialization. The comparison is shown for both ‘Folding’ and ‘Flattening’ sequences of garment manipulation. The top row shows the ground truth (GT) reconstructions, while the middle row presents the results from the proposed method, and the bottom row illustrates the results obtained using GarmentTracking. By visually comparing the three rows for each sequence, one can assess the accuracy and detail preserved in the 3D garment reconstruction by each approach.

This figure displays a qualitative comparison of the proposed method’s garment reconstruction results against the GarmentTracking method (using ground truth initialization) on the VR-Folding dataset, specifically focusing on the ‘Folding’ and ‘Flattening’ sequences. The comparison showcases the differences in reconstructed garment shapes, demonstrating the accuracy and detail preserved by the proposed method in comparison to the baseline, highlighting the superior ability to handle complex deformations and occlusions.

This figure displays a qualitative comparison of the 3D garment reconstruction results obtained using the proposed method and the GarmentTracking method (initialized with ground truth meshes) on the VR-Folding dataset. The comparison is shown for both folding and flattening sequences of the garments. The figure aims to visually demonstrate the superior accuracy and detail preservation of the proposed method compared to the GarmentTracking method.

This figure displays a qualitative comparison between the proposed method and the GarmentTracking method. The results for both folding and flattening sequences are shown. GarmentTracking uses the ground truth mesh as initialization, while the proposed method is shown to recover garment meshes more accurately and faithfully reflect the actual shape and deformation, even in complex scenarios.

This figure compares the qualitative results of the proposed method against the GarmentTracking method for both folding and flattening sequences. The top row shows the ground truth results. The middle row shows the results obtained using the proposed method, and the bottom row presents the results from the GarmentTracking method, which uses the ground truth mesh as initialization. The comparison highlights the superior accuracy and fidelity of the proposed method in reconstructing garment meshes in various states of deformation.

This figure provides a visual comparison of the 3D garment reconstruction results obtained using three different methods: the proposed method, GarmentTracking initialized with ground truth meshes, and ground truth. It showcases multiple frames from both the folding and flattening sequences for several garments (pants, shirt, top, skirt). The visual comparison highlights the superior accuracy and detail preservation of the proposed method compared to GarmentTracking, particularly in capturing intricate folds and deformations.

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed method to real-world data. Part (a) displays the original captured image of a pair of pants and the corresponding point cloud generated from it. Part (b) presents the 3D reconstructions of the pants obtained using the proposed method, demonstrating its ability to handle real-world scenarios, including both flat and folded garments.

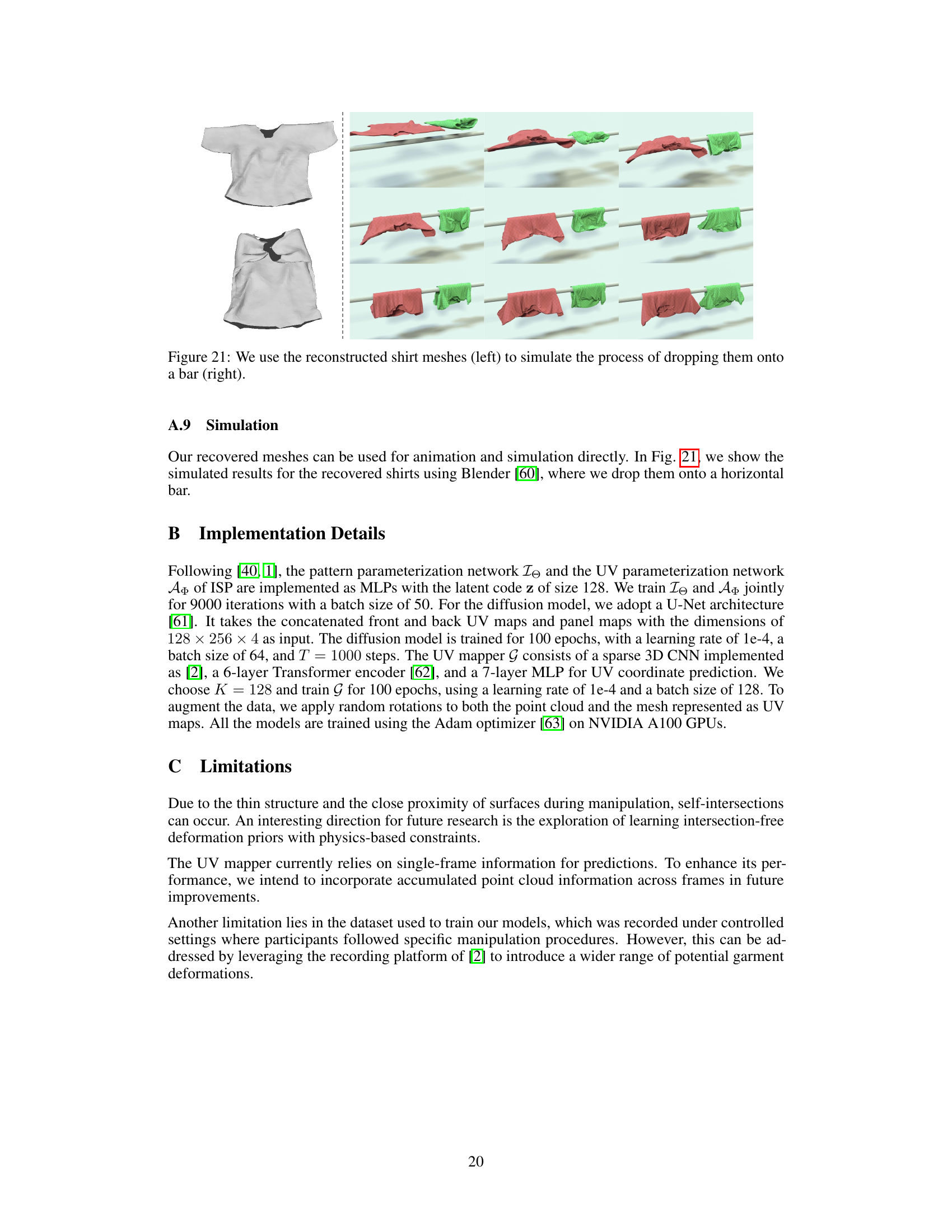

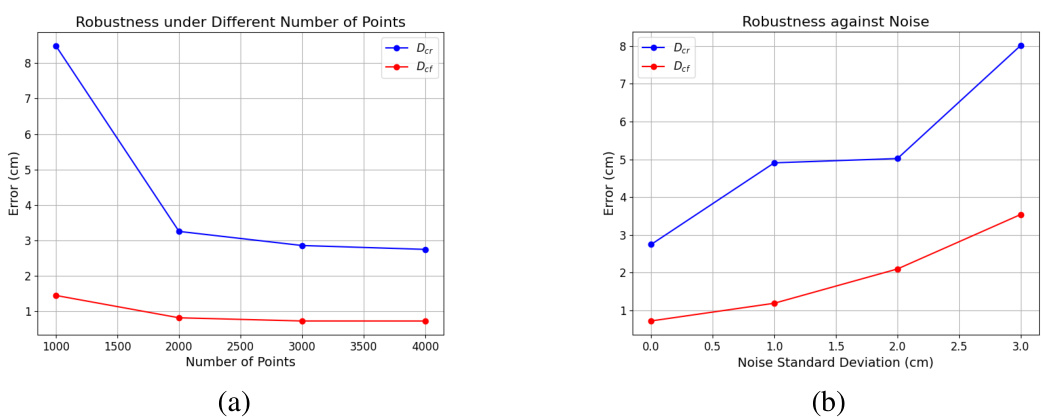

This figure shows the robustness of the proposed method. (a) tests the influence of the number of input points on reconstruction accuracy, showing that even with fewer points, the accuracy remains relatively high. (b) evaluates the effect of adding Gaussian noise to the input points, demonstrating that the method remains relatively accurate even with considerable noise.

This figure presents a qualitative comparison of the 3D garment reconstruction results obtained using the proposed method and the GarmentTracking method (initialized with ground truth meshes) for both folding and flattening sequences. The comparison highlights the superior accuracy and detail preservation of the proposed method in reconstructing the complex shapes and deformations of garments under various manipulation conditions.

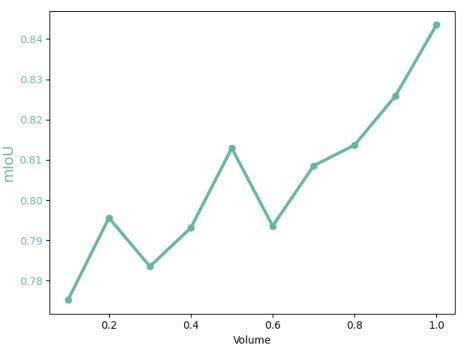

The figure shows the relationship between the volume of the input point cloud and the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) between the ground truth panel masks and the masks fitted using equation 10 from the paper. The x-axis represents the normalized volume of the point cloud, and the y-axis shows the mIoU. It demonstrates that a larger point cloud volume generally leads to better fitting results, as indicated by higher mIoU values.

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the proposed method for 3D garment reconstruction. It starts with a point cloud as input, maps the 3D points to the 2D UV space using a UV mapper to get sparse UV maps and panel masks. Then, it recovers complete UV maps and panel masks using ISP (Implicit Sewing Patterns) and a deformation prior. Finally, it reconstructs the 3D mesh of the deformed garment.

This figure illustrates the workflow of the proposed method for 3D garment reconstruction from a point cloud. The process starts by mapping the input point cloud to the UV space of the garment’s panels using a UV mapper, resulting in sparse UV maps and panel masks. Then, using the Implicit Sewing Patterns (ISP) model and a learned deformation prior, the method recovers complete UV maps and panel masks. Finally, these complete maps are used to reconstruct the 3D mesh of the deformed garment.

More on tables

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method’s performance against two state-of-the-art methods, GarmentNets and GarmentTracking, using the VR-Folding dataset. The metrics used for comparison include Chamfer Distance (Def), Correspondence Distance (Der), and the percentage of frames where Der < 3cm (A3) and Der < 5cm (A5). The results are shown separately for the ‘Folding’ and ‘Flattening’ tasks and for different garment types (Shirt, Pants, Top, Skirt). The table also indicates whether the compared methods used ground truth initialization (‘GT’), perturbed ground truth initialization (‘Pert.’), or GarmentNet’s initialization (‘GN’). This allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed method’s accuracy and robustness compared to existing approaches.

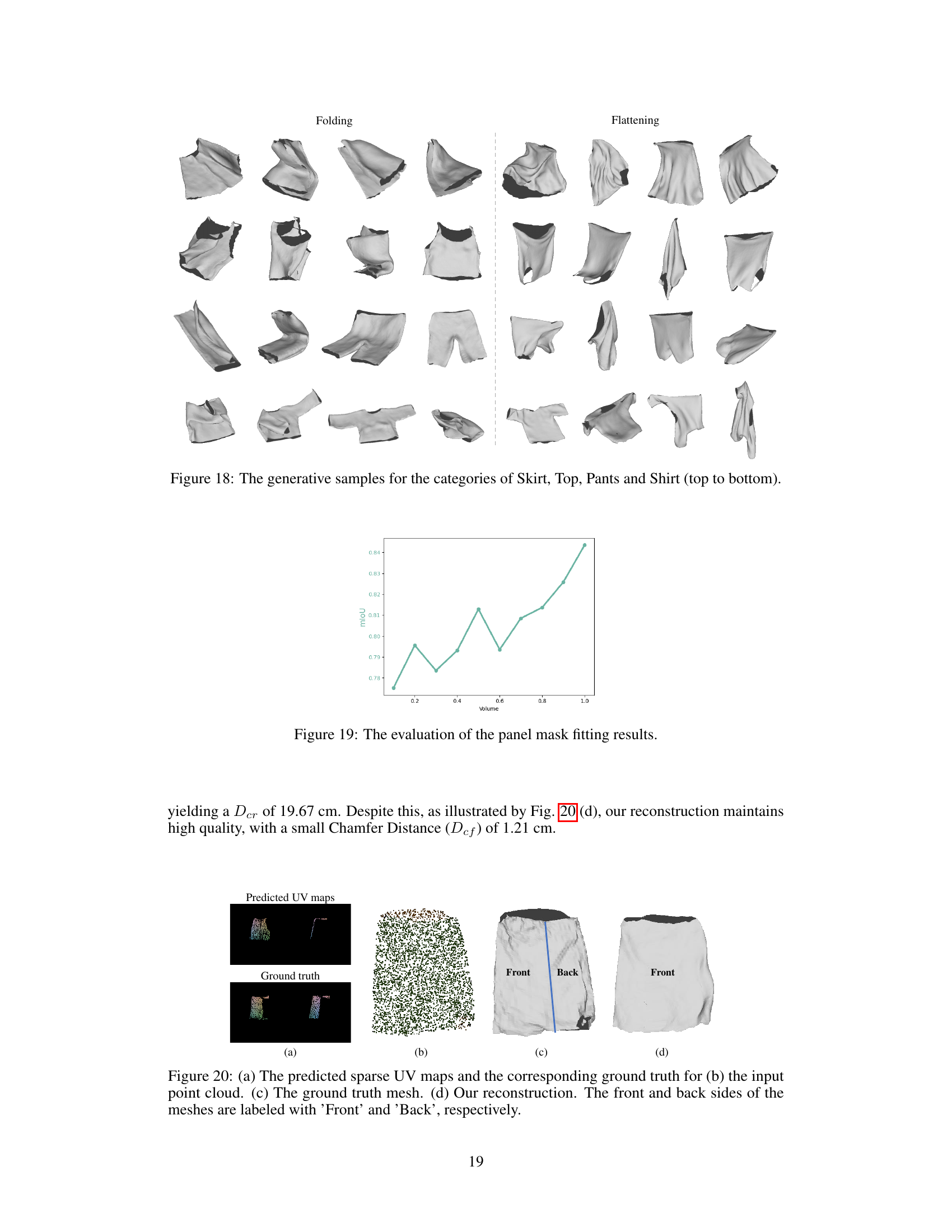

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the proposed method. It shows the impact of using different combinations of guidance signals (sparse UV maps, recovered panel masks, and previous frame’s recovery) on the reconstruction accuracy, measured by A3, A5, Dcr, and Dcf. The results demonstrate that using all three guidance signals leads to the best performance.

Full paper#