↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world networks exhibit unfair biases due to the presence of sensitive attributes in the data. Existing methods for estimating graphical models often exacerbate these biases. This leads to inaccurate and discriminatory models, which is a significant issue for various applications relying on fair and accurate representations of relationships. This lack of fairness in graphical models is problematic because it can perpetuate existing societal biases and lead to unfair or discriminatory outcomes.

The paper introduces Fair GLASSO, a novel method that addresses this issue. Fair GLASSO uses two new bias metrics to quantify the bias present in the data and incorporates them as regularizers in a graphical lasso framework to estimate unbiased precision matrices. The method is demonstrated to be effective on both synthetic and real-world datasets, showcasing its practicality and value. This method presents a key advancement by formally defining fairness for graphical models and provides an efficient way to estimate unbiased graphical models from potentially biased data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with biased graph data, as it provides a novel framework for ensuring fairness in the statistical relationships within the data. It addresses the growing concern of bias in real-world networks and offers a practical solution for building more equitable and accurate graphical models, impacting various fields from social sciences to finance.

Visual Insights#

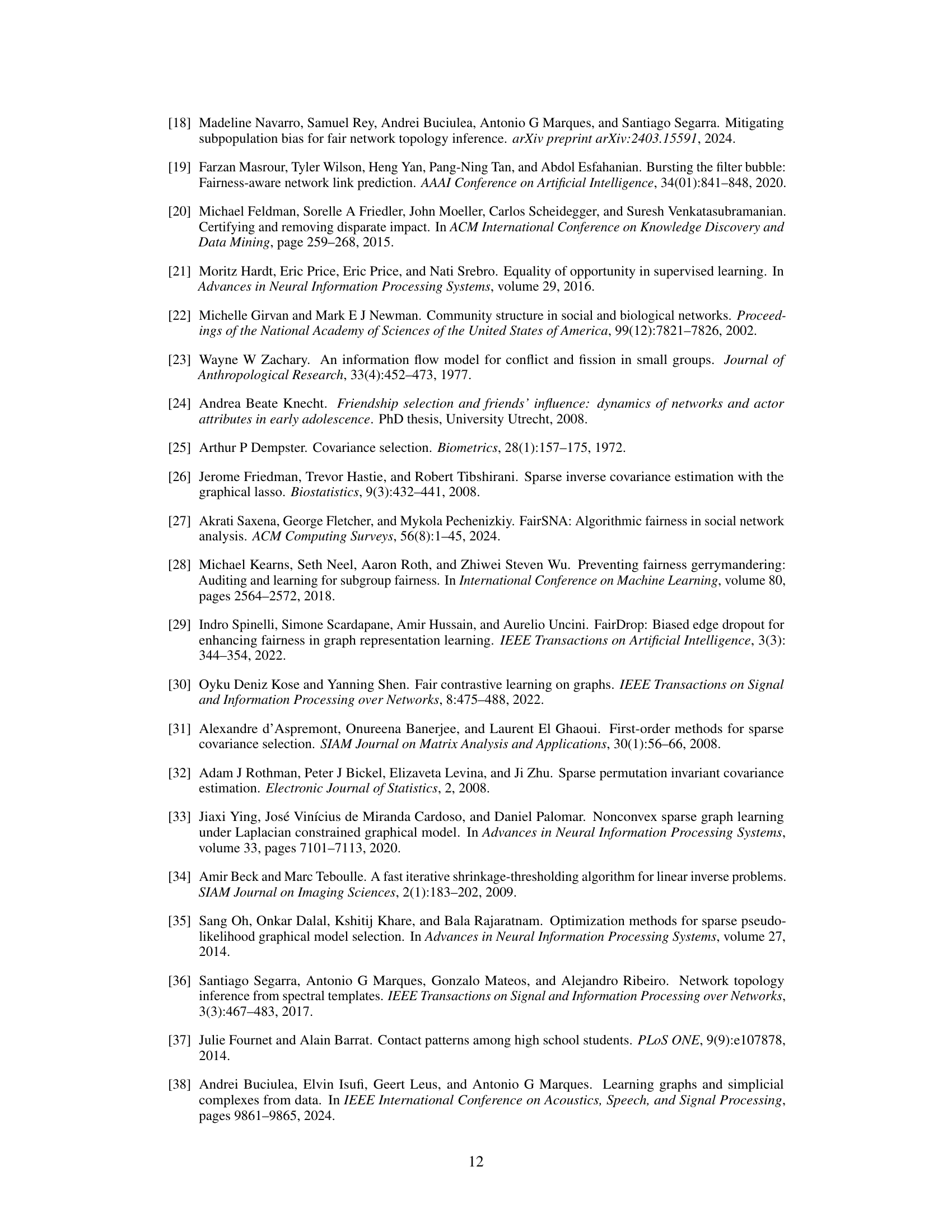

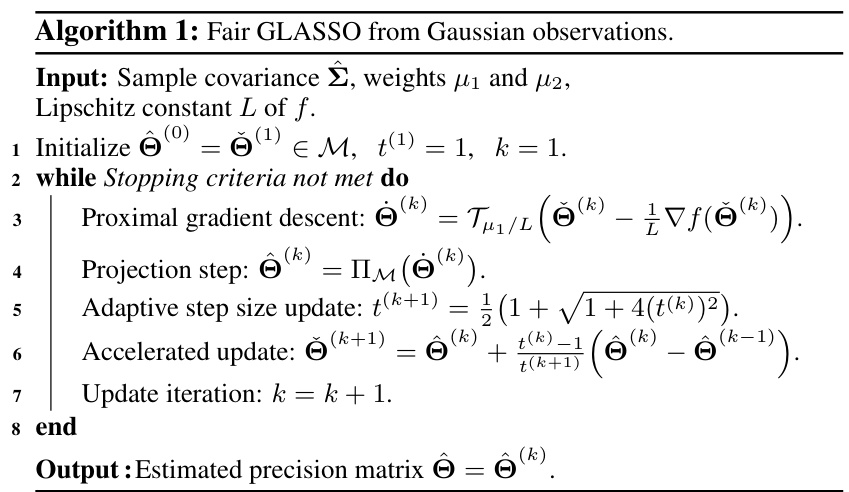

This figure showcases three real-world networks (Karate club, Dutch school, and U.S. Senate) illustrating different group structures and biases in their connections. Node colors represent group memberships. Blue edges connect nodes within groups, red edges connect nodes across groups, and edge thickness represents the magnitude of partial correlation. The figure quantifies each network’s modularity (M) and the ratios of positive to negative partial correlations within (W) and across (A) groups, highlighting varying degrees of group-wise modularity and correlation bias.

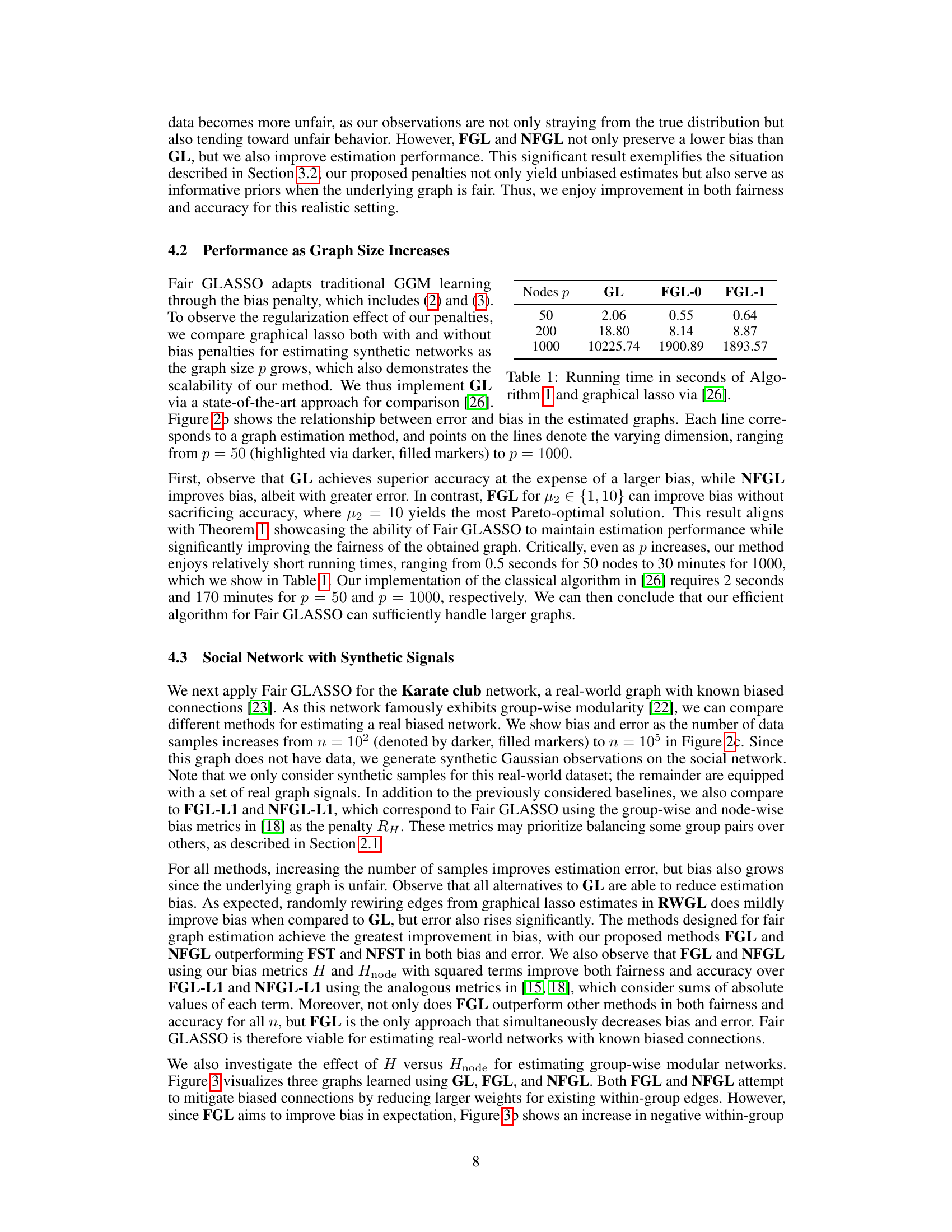

This table presents the bias and error for estimating four real-world networks using different methods. The networks are: Karate Club, School, Co-authorship, and MovieLens. Each method’s performance is evaluated based on two metrics: bias and error. The top row indicates the inherent bias present in the ground truth network for each dataset. Bold values highlight the best results for each network.

In-depth insights#

Fair GGM Estimation#

Fair Gaussian Graphical Model (GGM) estimation tackles the challenge of learning accurate graphical models from data containing biases. The core issue is to mitigate the discriminatory effects stemming from biased data, ensuring that the learned models do not perpetuate or exacerbate existing societal inequities. This involves developing novel metrics to quantify fairness in GGMs, moving beyond simple edge-counting toward more nuanced assessments that capture both connectivity and correlation biases. Fair estimation algorithms then incorporate these fairness metrics as regularizers within optimization problems, achieving a balance between fairness and accuracy. This often entails a trade-off: stricter fairness constraints may reduce accuracy, and vice-versa. The analysis of this trade-off, including theoretical bounds on estimation error as a function of both model bias and fairness constraints, is crucial in evaluating the practical utility of Fair GGM estimation. Furthermore, the development of efficient algorithms for solving these often complex optimization problems is a key element in enabling the widespread adoption of fair GGMs in real-world applications. Finally, the comprehensive evaluation of Fair GGM estimation using both synthetic and real-world data is critical to demonstrate its effectiveness and limitations in varied settings.

Bias Metrics Defined#

The heading ‘Bias Metrics Defined’ suggests a section dedicated to formally defining metrics used to quantify bias within a model, particularly in relation to sensitive attributes. It’s likely that the authors are addressing the challenge of unfairness arising from biased data influencing the model’s behavior. The metrics themselves could take various forms. Simple metrics might calculate the difference in average predicted outcomes or model parameters between different groups, while more sophisticated metrics could incorporate interactions, conditional dependencies, or other nuanced aspects of the data. The paper would likely justify the choice of specific metrics by arguing that they effectively capture relevant types of bias, providing a clear explanation of how they quantify the disparity in model behavior across groups. This would further show how they align with a formal definition of fairness, like demographic parity, equalized odds, or other fairness criteria relevant to the application and data characteristics. Ideally, the discussion should also highlight the limitations of these metrics, acknowledging their potential sensitivity to specific data distributions or the possibility that certain forms of bias may not be fully captured. Overall, a thoughtful definition and evaluation of bias metrics are crucial for establishing trust and accountability in sensitive applications of machine learning.

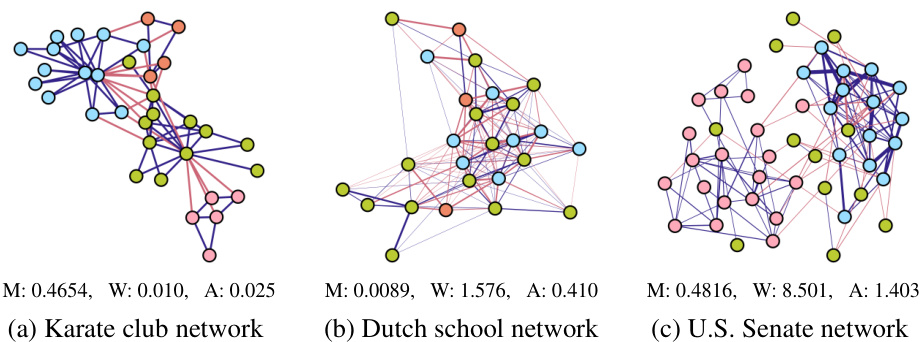

Fair GLASSO Algorithm#

The Fair GLASSO algorithm tackles the critical problem of bias in Gaussian graphical models (GGMs), which often reflect societal biases present in the data they are trained on. It directly addresses this by incorporating fairness constraints into the standard GLASSO (graphical lasso) optimization problem. Instead of simply finding a sparse precision matrix that maximizes likelihood, Fair GLASSO also minimizes a bias metric, promoting balanced statistical relationships across different groups, defined by sensitive attributes (like race or gender). This is achieved by adding a fairness-promoting regularizer to the objective function, creating a trade-off between accuracy and fairness. The algorithm’s design allows for an efficient solution using proximal gradient methods, offering a balance between computational efficiency and the desired fairness properties. A key theoretical contribution is demonstrating the algorithm’s convergence rate and analyzing the trade-off between accuracy and fairness, demonstrating when accuracy is preserved despite the fairness regularizer. The effectiveness of the Fair GLASSO is demonstrated empirically on both synthetic and real-world datasets, showcasing its ability to learn accurate and unbiased graphical models from potentially biased data. This represents a significant advancement in fair machine learning and offers a valuable tool for various applications where unbiased understanding of relationships is crucial.

Fairness-Accuracy Tradeoff#

The fairness-accuracy tradeoff is a central challenge in developing fair machine learning models, particularly when applied to graphical models. Balancing the need for accurate model representation with fairness considerations requires careful consideration of bias metrics and regularization techniques. The paper explores this by introducing two bias metrics to quantify unfairness in graphical models. These metrics are incorporated into a regularized graphical lasso approach called Fair GLASSO, which directly addresses the tradeoff by enabling controlled adjustments between fairness and accuracy. Theoretically, Fair GLASSO demonstrates that accuracy can be maintained even in the presence of fairness constraints, though this depends heavily on the inherent bias in the underlying data. Empirical evaluations on both synthetic and real-world datasets showcase the effectiveness of Fair GLASSO, highlighting scenarios where accuracy can be preserved while achieving significant fairness improvements. The tradeoff, however, is not always favorable, and the results suggest that in cases of severe bias, some accuracy might be sacrificed to ensure fairness. This highlights the crucial need for nuanced approaches that recognize the intricate relationship between fairness and accuracy, emphasizing the importance of Fair GLASSO in achieving a more equitable and robust approach.

Real-World Applications#

A research paper section on “Real-World Applications” would ideally delve into specific examples showcasing the practical utility and impact of the discussed methods or models. It should move beyond theoretical considerations and demonstrate the technology’s effectiveness in addressing real-world challenges. Concrete examples from diverse fields are crucial, highlighting the model’s performance against existing benchmarks or alternative solutions. A strong section would also address the limitations and challenges encountered during real-world implementation, such as data quality issues, computational constraints, or ethical considerations. Qualitative and quantitative analyses should be presented to support the claims of real-world impact. Case studies, with detailed explanations of problem setup, solutions, and results, can significantly enhance the credibility and persuasiveness of the section. Finally, the discussion should extend to future research directions motivated by observed limitations or potential improvements in real-world deployment.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure demonstrates the performance of Fair GLASSO in terms of both error and bias under different conditions. Panel (a) shows how error and bias change as the data becomes increasingly biased. Panel (b) illustrates the scalability of the method by showing the performance as the size of the graph increases. Finally, panel (c) shows how the algorithm performs on a real-world dataset with biased data as the number of observations increases.

This figure compares the results of applying three different methods (graphical lasso, Fair GLASSO with bias penalty H, and Fair GLASSO with bias penalty Hnode) to the karate club network. The node colors represent group membership, the edge thickness represents the magnitude of the edge weight, and the edge color represents the sign of the correlation (blue for positive, red for negative). The figure shows how different methods handle biases in the data and produce different graph structures.

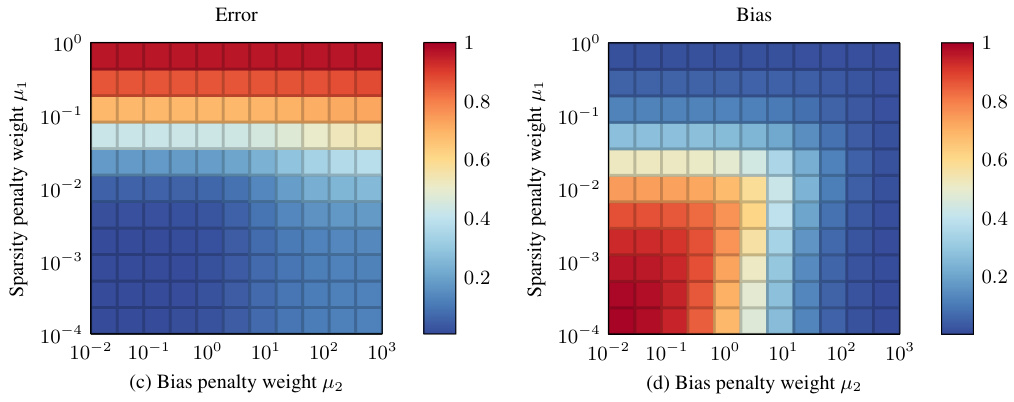

This figure shows the results of an experiment evaluating the performance of Fair GLASSO in terms of error and bias. The experiment varied the values of two hyperparameters: μ₁ (sparsity penalty weight) and μ₂ (bias penalty weight). The heatmaps visualize how changes in these hyperparameters affect the error and bias in estimating a fair precision matrix. Lower values indicate better performance. Subfigure (a) displays error, while (b) shows bias.

This figure shows the performance of Fair GLASSO in terms of error and bias for estimating fair Gaussian graphical models. It demonstrates how the error and bias change as the hyperparameters μ₁ (sparsity penalty weight) and μ₂ (bias penalty weight) are varied. The heatmaps visualize the trade-off between accuracy and fairness, showing that appropriate tuning of the hyperparameters allows for good performance in both areas. The figure suggests that Fair GLASSO can accurately estimate fair graphical models while controlling bias, even with varying degrees of sparsity and fairness constraints.

This figure displays the results of experiments designed to test the robustness of the Fair GLASSO algorithm under violations of the assumptions made in Theorem 1. Panel (a) shows how the estimation error changes as the true precision matrix becomes denser (violating AS1). Panel (b) demonstrates the impact of eigenvalues approaching zero (violating AS2). Panel (c) illustrates how estimation error is affected by increasingly imbalanced group sizes (violating AS4).

More on tables

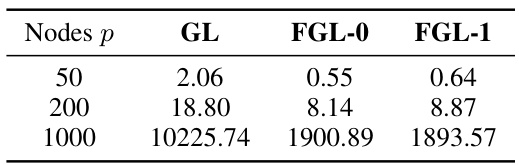

This table shows the running times in seconds for Algorithm 1 (Fair GLASSO) and the graphical lasso algorithm from reference [26]. The running times are compared for three different graph sizes (number of nodes): 50, 200, and 1000. It demonstrates the scalability of the proposed Fair GLASSO algorithm, showing that despite increased graph size, the computation time remains relatively manageable compared to the baseline graphical lasso method.

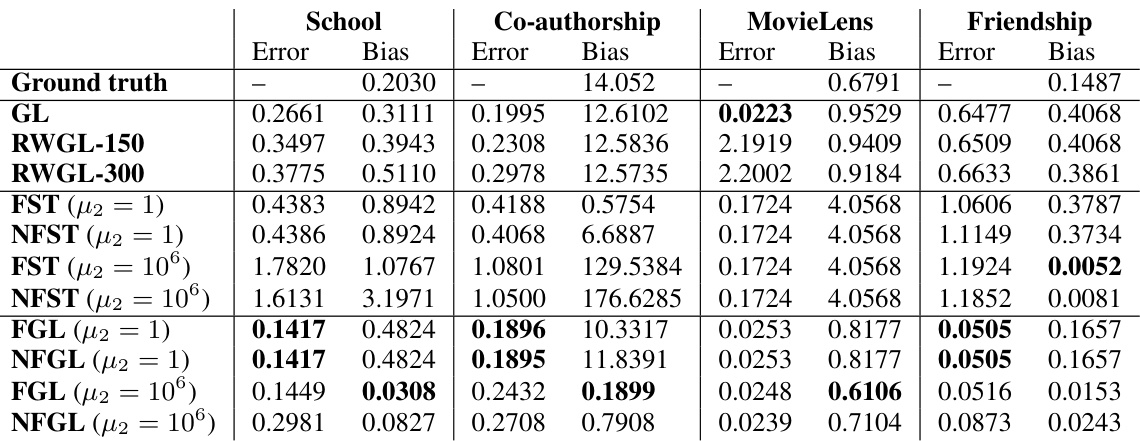

This table presents the results of applying different methods for estimating graphical models on four real-world datasets: School, Co-authorship, MovieLens, and Friendship. Each dataset has a different sensitive attribute (gender, publication type, movie release year, gender respectively). The table shows the bias and error for each method, with the lowest bias and error values highlighted in bold. The ground truth bias (top row) indicates the inherent bias present in each dataset. The methods compared include traditional graphical lasso (GL), graphical lasso with randomly rewired edges (RWGL), Fair GLASSO with group-wise bias (FGL) and node-wise bias (NFGL) penalties, and other fairness-aware baselines (FST, NFST).

This table presents the bias and error for four real-world network datasets (Karate club, School, Co-authorship, and MovieLens) using several methods: GL (Graphical Lasso), RWGL (Randomly Rewired GL), FST (Fair Spectral Templates), NFST (Node-wise Fair Spectral Templates), FGL (Fair GLASSO with H), and NFGL (Fair GLASSO with Hnode). The top row indicates the ground truth bias for each network. The table allows comparison of different methods’ performance in terms of bias and error, highlighting the best performing methods for each dataset.

Full paper#