↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs) are effective for solving PDEs, but their large number of parameters becomes computationally expensive for high-dimensional problems. Existing workarounds, like frequency truncation, limit accuracy and make it hard to find the optimal parameters. This is a significant limitation for many important applications.

This paper proposes AM-FNOs, a novel approach that uses an amortized neural parameterization to handle many frequency modes with a fixed number of parameters. They provide two versions of AM-FNOs, one using the Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN) and one using Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs). The method shows improved accuracy on diverse PDE benchmark datasets, reaching up to a 31% improvement over existing methods. The authors also demonstrate the AM-FNO’s ability to perform well on zero-shot super-resolution tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with neural operators and partial differential equations (PDEs). It offers significant improvements in efficiency and accuracy, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional problems. The introduction of amortized parameterization using neural networks opens up new avenues for research into more efficient and scalable solutions for PDEs. The improved performance on various benchmark PDEs makes the proposed methods immediately applicable to many scientific computing applications.

Visual Insights#

This figure compares the frequency-specific parameterization used in traditional Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs) with the amortized neural parameterization introduced in the proposed AM-FNO. FNOs use a separate parameter for each discretized frequency, leading to a large number of parameters, especially for high-dimensional problems. The truncation of high frequencies further limits the representation capability of FNOs. In contrast, AM-FNO uses either a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) or a Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN) to learn a mapping between frequencies and kernel function values. This allows AM-FNO to handle arbitrarily many frequency modes using a fixed number of parameters, while also leveraging orthogonal embedding to improve the representation of frequency information by MLPs.

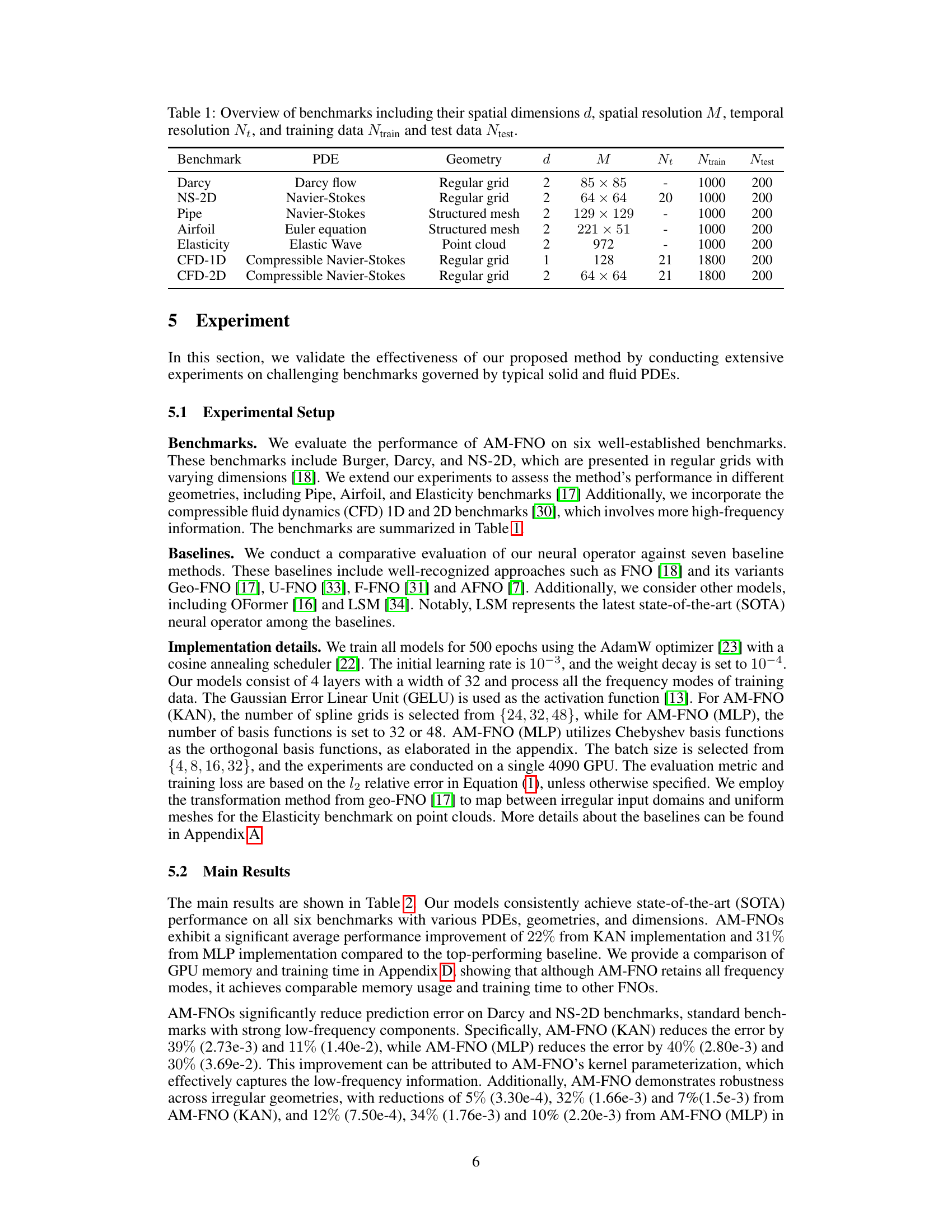

This table presents an overview of the six benchmark datasets used in the paper to evaluate the performance of the proposed AM-FNO model and its comparison with baseline models. For each dataset, it lists the partial differential equation (PDE) being modeled, the geometry of the problem domain, the spatial dimensions (d), the spatial resolution (M), the temporal resolution (Nt), the number of training samples (Ntrain), and the number of test samples (Ntest). These details are crucial for understanding the experimental setup and reproducing the results.

In-depth insights#

Amortized FNO#

Amortized Fourier Neural Operators (AM-FNOs) represent a significant advancement in addressing the limitations of traditional Fourier Neural Operators (FNOs). Standard FNOs utilize separate parameters for each frequency mode, leading to an excessive number of parameters, especially when handling high-dimensional PDEs. AM-FNOs cleverly circumvent this parameter explosion by employing an amortized neural network to parameterize the kernel function, mapping frequencies to values. This allows for handling arbitrarily many frequencies while keeping the total number of parameters fixed. Two key implementations of AM-FNO are explored, using Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs) and Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) coupled with orthogonal embedding functions. While KANs show promise in function approximation, MLPs offer a better balance of accuracy and efficiency. The core advantage lies in significantly improved efficiency and scalability, surpassing existing methods in resolving high-dimensional PDEs and facilitating zero-shot super-resolution. The approach tackles limitations inherent in frequency truncation, inherent in traditional FNOs, which limits the representation of high-frequency details. Ultimately, AM-FNOs demonstrate a promising future for solving complex PDEs.

KAN & MLP#

The authors explore two distinct neural network architectures, Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs) and Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), for use in their Amortized Fourier Neural Operator (AM-FNO). While KANs offer superior accuracy in function approximation, they are computationally expensive. Conversely, MLPs, while faster, exhibit a spectral bias that could limit their ability to capture high-frequency information crucial for some PDEs. To overcome the MLP limitation, the authors employ an orthogonal embedding (e.g., using Chebyshev basis functions) to improve their ability to represent high-frequency details. This highlights a key trade-off in choosing between these models: KANs provide high accuracy but at the cost of speed, whereas MLPs, when enhanced with orthogonal embedding, provide a faster, efficient solution with potentially only slightly reduced accuracy. The paper’s results indicate that despite the computational advantage of MLPs, KANs still offer comparable performance in some scenarios, making the choice of architecture a nuanced decision that should consider the specific demands of the PDE problem being addressed and the available computational resources.

High-Dim PDEs#

Addressing high-dimensional partial differential equations (PDEs) presents a significant challenge in scientific computing. Standard numerical methods often become computationally intractable due to the exponential increase in complexity with dimensionality. The core difficulty stems from the curse of dimensionality, impacting both memory requirements and computational time. This necessitates the exploration of alternative approaches like machine learning, specifically neural operators. These models offer a promising avenue for approximating solutions efficiently, even in high dimensions. However, challenges remain in ensuring accuracy and generalizability, particularly when dealing with complex PDEs exhibiting high-frequency components or irregular geometries. Further research should focus on developing more robust and efficient neural operator architectures, capable of handling the inherent complexities of high-dimensional PDEs while maintaining computational feasibility. This includes exploring advanced architectures, improved regularization techniques, and effective handling of high-frequency information, which are crucial to obtaining accurate and reliable solutions.

Super-Resolution#

The concept of ‘super-resolution’ in the context of this research paper likely refers to the model’s ability to generalize to higher resolutions than those seen during training. This is a crucial aspect of neural operators, which aim to learn the underlying operator governing a PDE rather than memorizing specific solutions at particular resolutions. The successful demonstration of zero-shot super-resolution, where the model accurately predicts solutions at higher resolutions without explicit training at those resolutions, is a significant finding. This capability highlights the model’s ability to extrapolate, an important feature lacking in methods reliant on specific discretization levels. The results section likely details quantitative improvements in accuracy at higher resolutions compared to other models, showcasing the efficiency and generalization power of the proposed approach. Further analysis might involve comparing performance across different frequency components of the solution to understand how well the model captures both low and high-frequency details at increased resolutions. The success in super-resolution indicates the potential of the method for applications requiring high-resolution outputs without extensive training data, signifying a major advancement in computational efficiency and model generalization.

Limitations#

A thoughtful analysis of the limitations section of a research paper would explore several key aspects. First, it would examine whether the limitations are clearly and explicitly stated, acknowledging any assumptions made during the research process. This would include evaluating the scope of the claims presented by assessing the generalizability of the study’s findings to other contexts. For instance, limitations regarding the sample size, data collection methods, or the specific experimental setting should be transparently discussed, particularly when they could affect the reliability and validity of the results. A thorough analysis will also address potential methodological shortcomings, exploring whether the chosen approach or employed models might constrain the interpretations and conclusions drawn from the study. Furthermore, it should assess the impact of limitations on the results’ broader applicability by exploring the external validity of the findings. Addressing these aspects will help assess the robustness of the research and unveil avenues for future investigations, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the paper’s contributions and constraints.

More visual insights#

More on figures

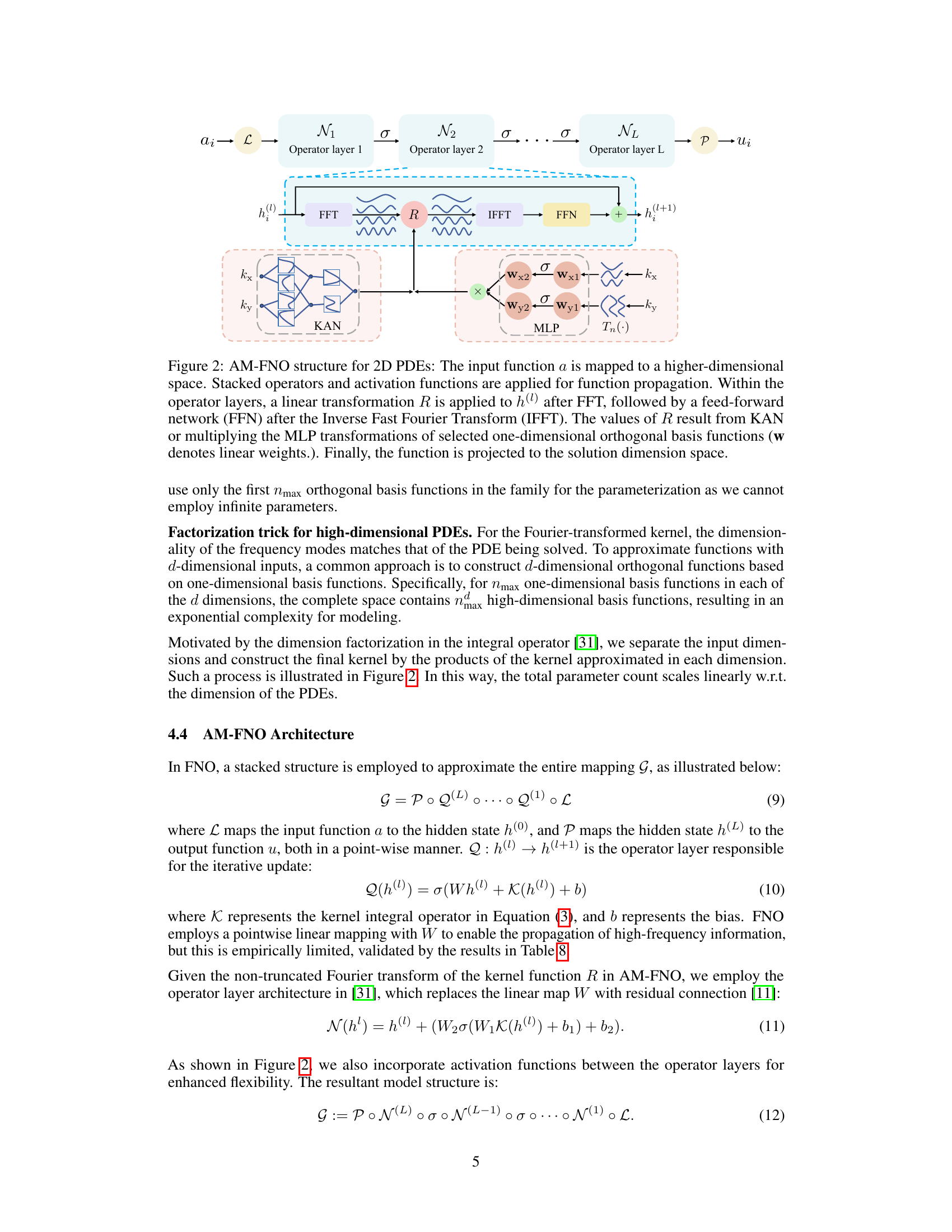

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Amortized Fourier Neural Operator (AM-FNO) for solving 2D Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). It shows how the input function is processed through multiple operator layers, each involving a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), a kernel transformation (R), an Inverse FFT (IFFT), and a feed-forward network (FFN). The kernel transformation R is implemented using either a Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN) or a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) with orthogonal basis functions to efficiently handle various frequencies. This allows the model to learn the mapping between input functions and output solutions without explicitly parameterizing each frequency mode, leading to a more efficient and generalizable model.

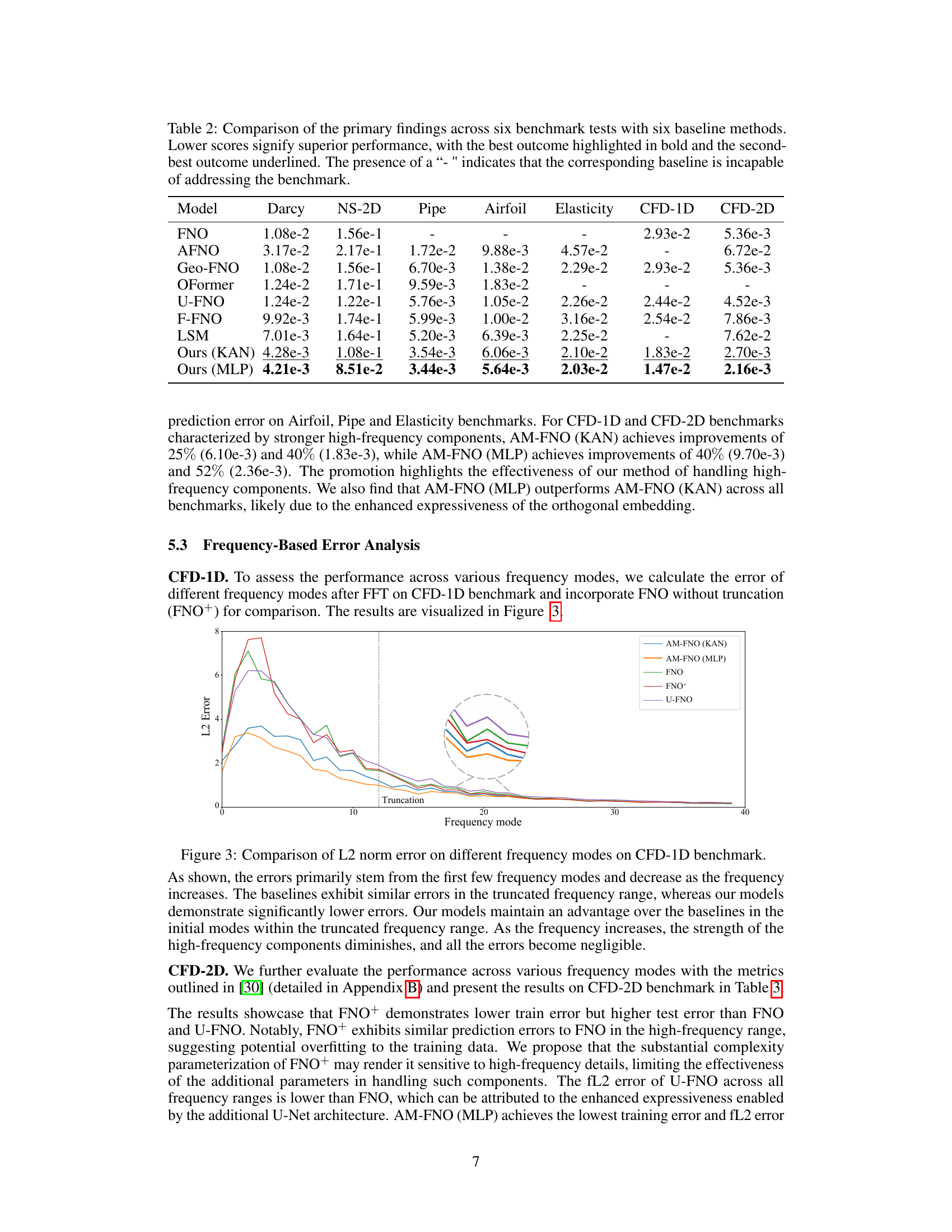

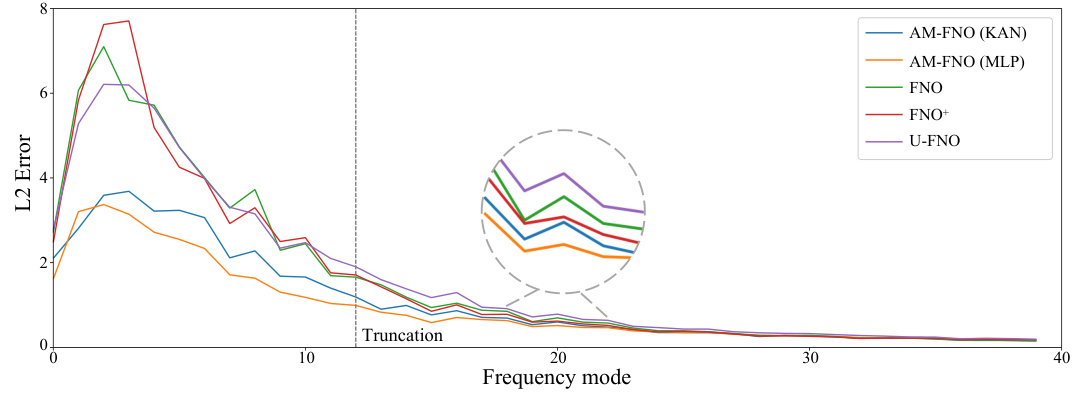

This figure compares the L2 norm error across different frequency modes for the CFD-1D benchmark. It shows the performance of AM-FNO (KAN), AM-FNO (MLP), FNO, FNO+ (FNO without truncation), and U-FNO. The x-axis represents the frequency mode, and the y-axis shows the L2 error. The figure highlights that AM-FNO models consistently outperform the baseline methods across all frequency ranges, especially in the lower frequencies. The figure also indicates that the errors decrease as the frequency increases, and that the error from the truncated frequencies becomes negligible.

This figure shows ablation study results on the impact of hyperparameters of the Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs) used in AM-FNO. Three subplots show how the L2 relative error changes with respect to the number of basis functions, the hidden layer size of the KAN, and the grid size of the KAN, respectively. Results are shown for both the Darcy and Airfoil benchmarks.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Amortized Fourier Neural Operator (AM-FNO) for solving 2D Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). It shows how the input function is processed through multiple operator layers, each involving a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), a learned kernel transformation (R), an Inverse Fast Fourier Transform (IFFT), and a feed-forward network (FFN). The kernel transformation R is either learned by a Kolmogorov-Arnold Network (KAN) or by an MLP that takes in orthogonalized frequency embeddings. The process repeats for multiple layers, finally projecting to the solution space.

More on tables

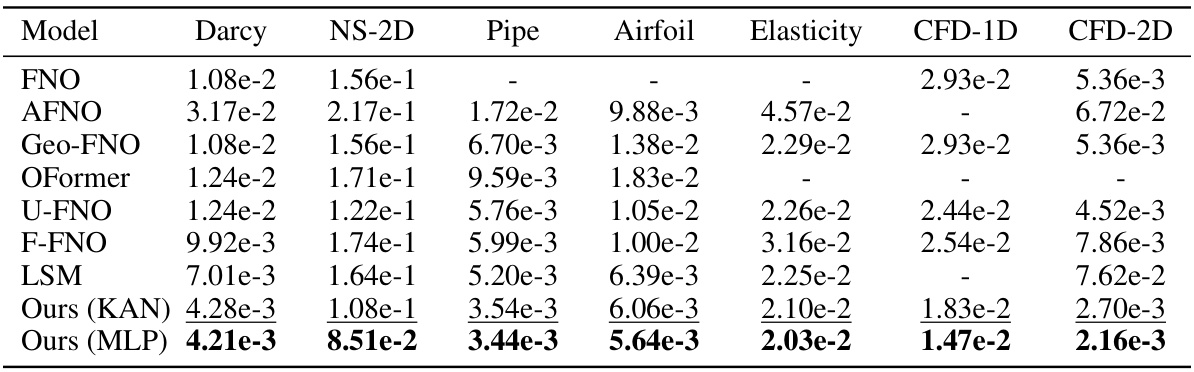

This table compares the performance of the proposed AM-FNO model (with KAN and MLP implementations) against six baseline neural operator methods across six different PDE benchmarks. The benchmarks vary in geometry, dimensionality, and the nature of the PDEs involved, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance. Lower values indicate better performance. The best result for each benchmark is shown in bold, while the second-best is underlined. The ‘-’ symbol indicates that a particular baseline method was not applicable to that benchmark.

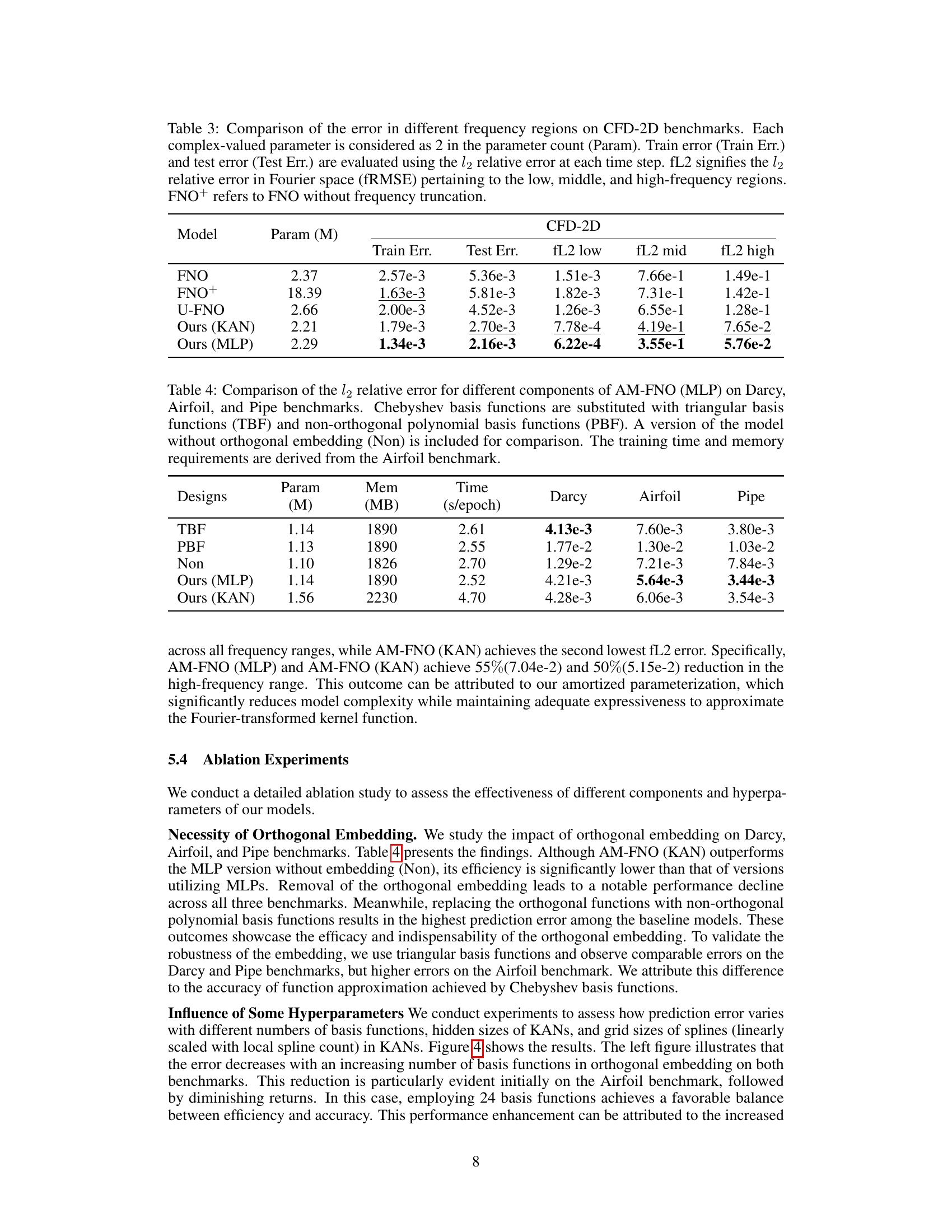

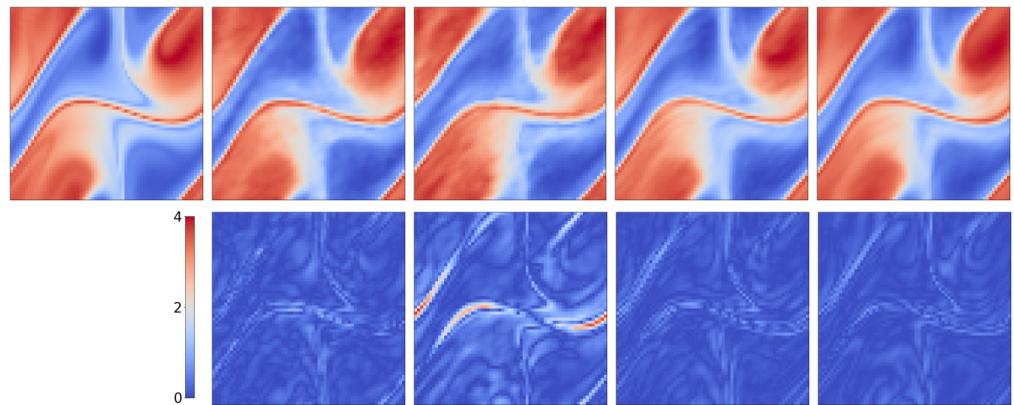

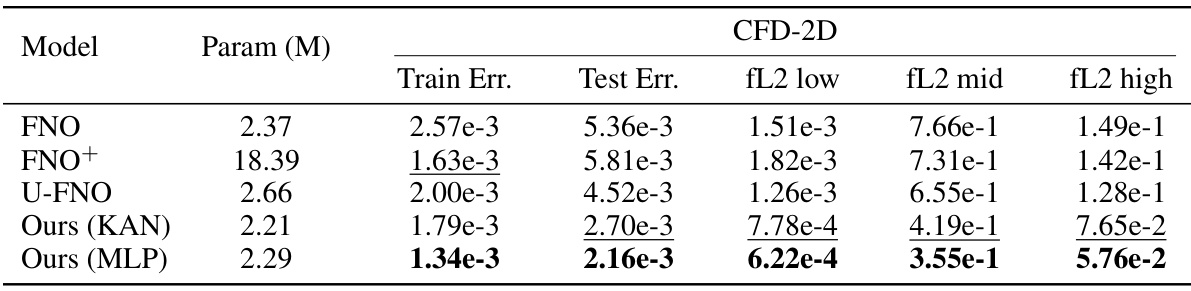

This table compares the performance of different neural operator models on the CFD-2D benchmark across different frequency ranges. It shows the training and test errors, as well as the error specifically in low, middle, and high-frequency components of the Fourier transform of the solution. FNO+ represents a version of the FNO model without frequency truncation for comparison.

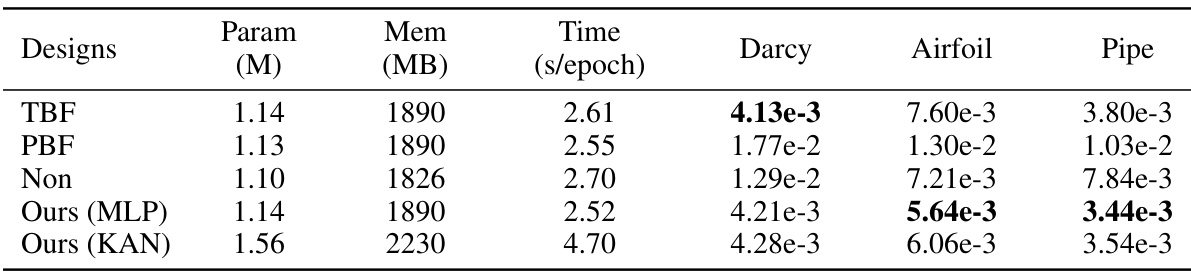

This table presents an ablation study comparing the performance of AM-FNO (MLP) using different orthogonal basis functions (Chebyshev, triangular, and non-orthogonal polynomials). It shows the l2 relative error for each configuration on three benchmarks (Darcy, Airfoil, and Pipe), along with training time and memory usage (based on Airfoil). The results highlight the importance of using orthogonal embedding functions for optimal performance.

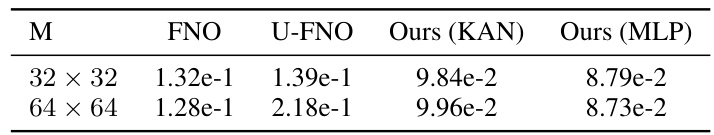

This table presents the results of a zero-shot super-resolution experiment on the NS-2D benchmark. Models were trained on lower-resolution data (32x32) and then evaluated on both the training resolution and a higher resolution (64x64). The table shows the l2 relative error for each model at each resolution. This demonstrates the models’ ability to generalize to unseen resolutions.

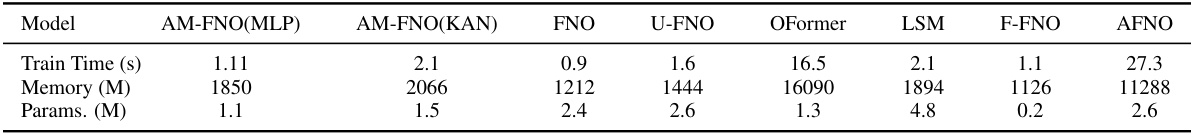

This table compares the GPU memory usage, training time per epoch, and the number of parameters for different neural operator models on the Darcy benchmark. The models compared include AM-FNO(MLP), AM-FNO(KAN), FNO, U-FNO, OFormer, LSM, F-FNO, and AFNO. The results show the computational resource requirements of each model.

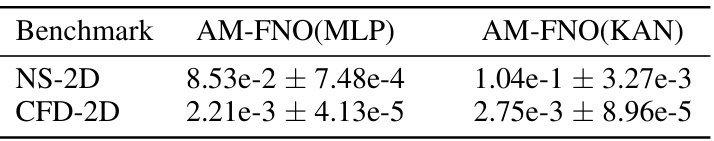

This table presents a comparison of the L2 relative error achieved by AM-FNO(MLP) and AM-FNO(KAN) on two benchmark problems: NS-2D (Navier-Stokes 2D) and CFD-2D (compressible fluid dynamics 2D). The results show the mean error and standard deviation, indicating the performance variability across multiple runs (although the paper mentions only one run was performed due to computational constraints). Lower values indicate better performance.

This table presents an ablation study comparing different components of the AM-FNO (MLP) model on three benchmarks: Darcy, Airfoil, and Pipe. It investigates the impact of using different basis functions (Chebyshev, Triangular, and Non-orthogonal Polynomial) and the necessity of orthogonal embedding. The table shows the relative ℓ2 error, model parameters, memory usage, and training time per epoch for each configuration.

This table compares the l2 relative error achieved by AM-FNO (MLP), AM-FNO (KAN), and other baseline methods (Geo-FNO, U-FNO, OFormer, LSM, and F-FNO) on the Darcy benchmark. Lower scores indicate better performance.

Full paper#