↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Designing new molecules is challenging due to the vastness of chemical space. Existing deep generative models struggle with efficient exploration and comprehensive understanding of this space. Current methods for navigating this space, such as optimization or linear traversal, have limitations.

ChemFlow addresses these issues by formulating molecule exploration as a dynamical system problem. It uses flows to learn nonlinear transformations for navigating the latent space of molecule generative models, thereby unifying and improving upon existing approaches. ChemFlow shows promising results across several molecule manipulation and optimization tasks in both supervised and unsupervised settings, proving its flexibility and effectiveness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in chemistry and materials science because it presents a novel framework for efficiently navigating the vast chemical space. ChemFlow unifies existing approaches, offering flexibility and potentially accelerating the discovery of new molecules with desired properties. Its impact extends to drug design and materials discovery, opening exciting new avenues for research.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the ChemFlow framework, which consists of a pre-trained encoder and decoder to map between molecules and their latent representations. A property predictor or Jacobian control guides the learning of a vector field that navigates the latent space, maximizing changes in desired molecular properties or structures. Dynamical regularization ensures smooth transitions, and the process is shown manipulating a molecule towards a drug-like structure (caffeine).

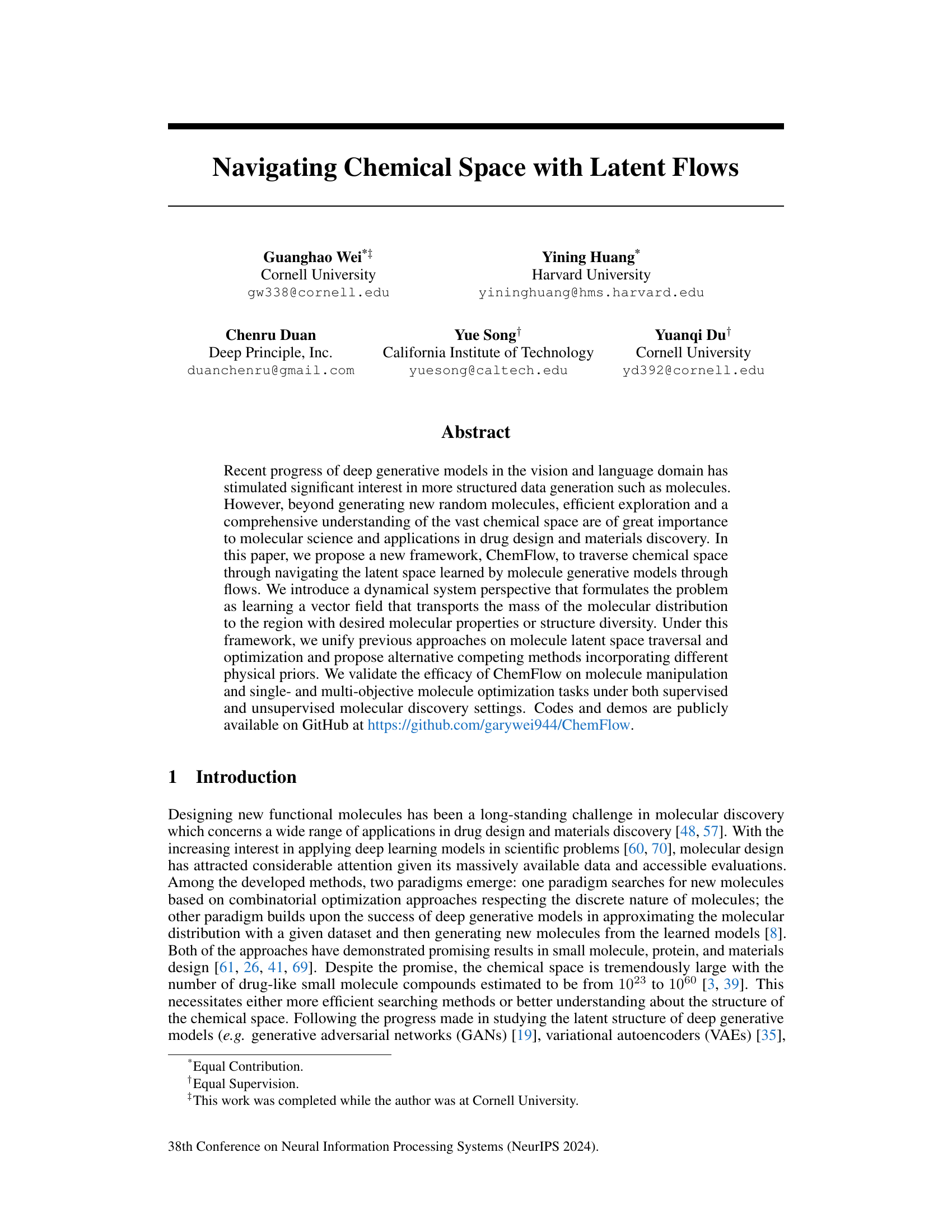

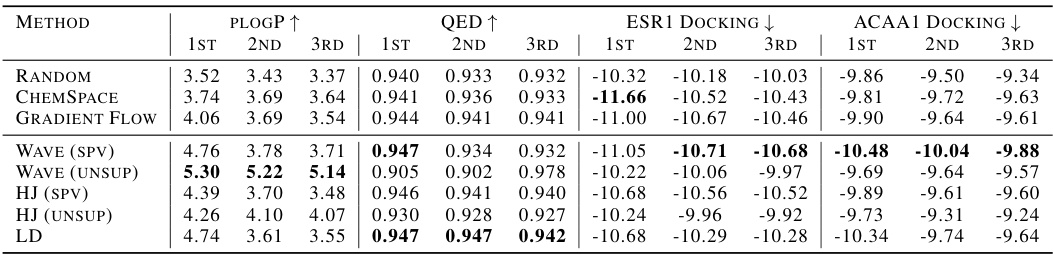

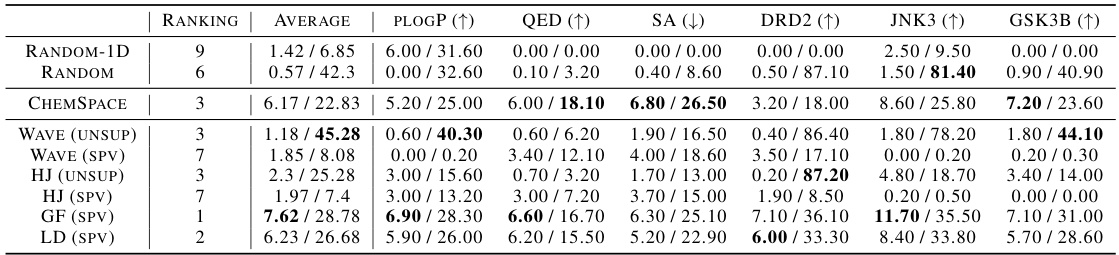

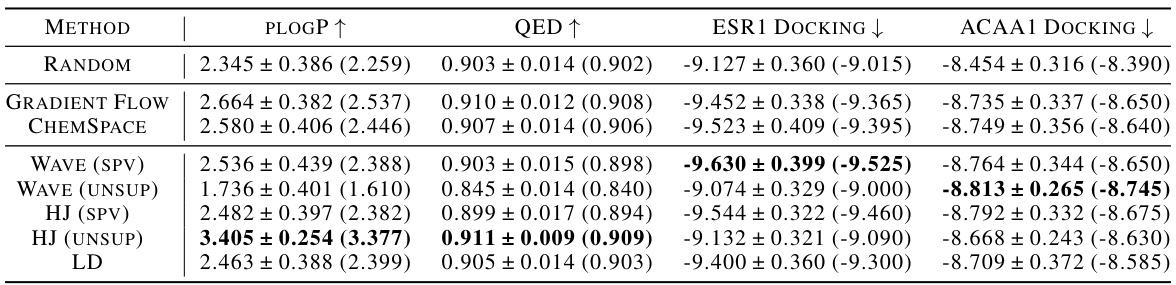

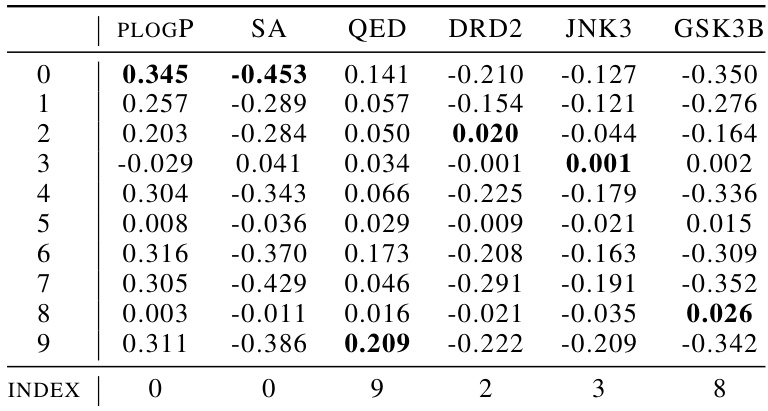

This table presents the results of unconstrained optimization experiments for three molecular properties: plogP (maximization), QED (maximization), and docking scores for two targets (minimization). Different methods, including baselines and the proposed ChemFlow with various configurations, are compared. The best results for each property are highlighted in bold. The table shows the performance of each method across three optimization iterations (1st, 2nd, and 3rd).

In-depth insights#

ChemFlow Framework#

The ChemFlow framework presents a novel approach to navigating chemical space using latent flows. It unifies existing methods for latent space traversal, such as gradient-based optimization and linear traversal, under a single dynamical systems perspective. This unification allows for the incorporation of diverse physical priors, leading to more flexible and effective exploration of chemical space. A key innovation is the formulation of the problem as learning a vector field that transports the mass of a molecular distribution to regions with desired properties or structural diversity. The framework’s adaptability enables its application in both supervised and unsupervised molecular discovery settings, further expanding its potential for diverse applications. ChemFlow demonstrates efficacy in various molecule manipulation and optimization tasks, showcasing its versatility and power as a valuable tool for drug design and materials discovery.

Latent Space Flows#

The concept of ‘Latent Space Flows’ in the context of a research paper likely refers to methods for navigating and manipulating the latent representations of data, especially in complex domains like molecular design. These flows are essentially vector fields that act on latent vectors (points in the latent space) to guide a smooth and controlled transformation. The power of latent space flows lies in their ability to unify various approaches for latent space exploration: gradient-based optimization is naturally seen as a flow, as is linear traversal, while disentangled traversal can be viewed as a special case with constrained flows. By expressing the problem as a dynamical system, this framework offers a unified theoretical basis for understanding and developing new methods. Physical priors can be incorporated (e.g., incorporating partial differential equations), leading to flows with desirable characteristics for specific applications. This framework is highly flexible; it can be applied in both supervised (with explicit guidance) and unsupervised (driving structure diversity) molecular discovery settings. ChemFlow, for example, is a likely implementation of this approach.

Mol Optimization#

The heading ‘Mol Optimization’ likely refers to the computational methods used to optimize molecular properties within the paper. The authors probably explore various optimization strategies in the latent space of pre-trained generative models to discover molecules with enhanced properties. This might involve gradient-based optimization, where gradients from a learned proxy function guide the search, or potentially more sophisticated methods like evolutionary algorithms. A key aspect would be the comparison of these approaches under both supervised and unsupervised learning scenarios. Supervised learning would involve using labelled data to guide the optimization, whereas unsupervised methods would explore the latent space without explicit labels. The overall goal is to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of molecular design, potentially focusing on specific objectives such as drug-likeness, potency, or other desired characteristics. The results section would likely demonstrate the relative performance of each strategy, highlighting strengths and weaknesses for different tasks or molecule types. Finally, this analysis would likely discuss the limitations of each method, such as the computational cost or the potential for getting stuck in local optima. A key focus would be on how well the methods generalize to unseen molecules and diverse chemical spaces.

Unsupervised Gen#

In the realm of unsupervised generative modeling, the absence of labeled data presents both a challenge and an opportunity. The core idea is to learn the underlying structure of the data without explicit guidance, relying instead on inherent patterns and relationships. This approach is particularly relevant for domains like molecular design where obtaining comprehensive labeled datasets can be extremely expensive and time-consuming. An unsupervised generative model for molecules might learn to capture the distribution of various molecular properties, enabling the generation of novel molecules with potentially desirable characteristics. A key challenge lies in evaluating the quality and novelty of the generated molecules, as the lack of labels prevents direct comparison to known, desired properties. Therefore, evaluation often focuses on metrics that assess the diversity, validity (e.g., adherence to chemical rules), and similarity to existing molecules in the learned distribution. Advanced techniques like variational autoencoders (VAEs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) are commonly employed, but their use in an unsupervised setting requires careful consideration of training strategies and evaluation metrics to ensure that the learned representation is meaningful and useful for downstream tasks such as optimization and property prediction.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore ChemFlow’s application to larger molecules and diverse chemical systems, such as polymers and proteins, moving beyond the small-molecule scope of the current study. The framework’s effectiveness in handling multi-objective optimization tasks could be further investigated, especially in complex scenarios with competing or conflicting objectives. A crucial area for future development is the integration of ChemFlow with advanced molecular simulation techniques. This combined approach could lead to highly accurate and efficient prediction of molecular properties and design of novel molecules with desired characteristics. Additionally, expanding ChemFlow to accommodate different data modalities beyond molecules, such as language or images, would significantly broaden its applicability and potential impact across diverse scientific domains. Finally, a deeper investigation into the underlying mathematical structure of ChemFlow’s dynamics would provide valuable theoretical insights and guide the design of even more efficient and powerful algorithms for chemical space exploration.

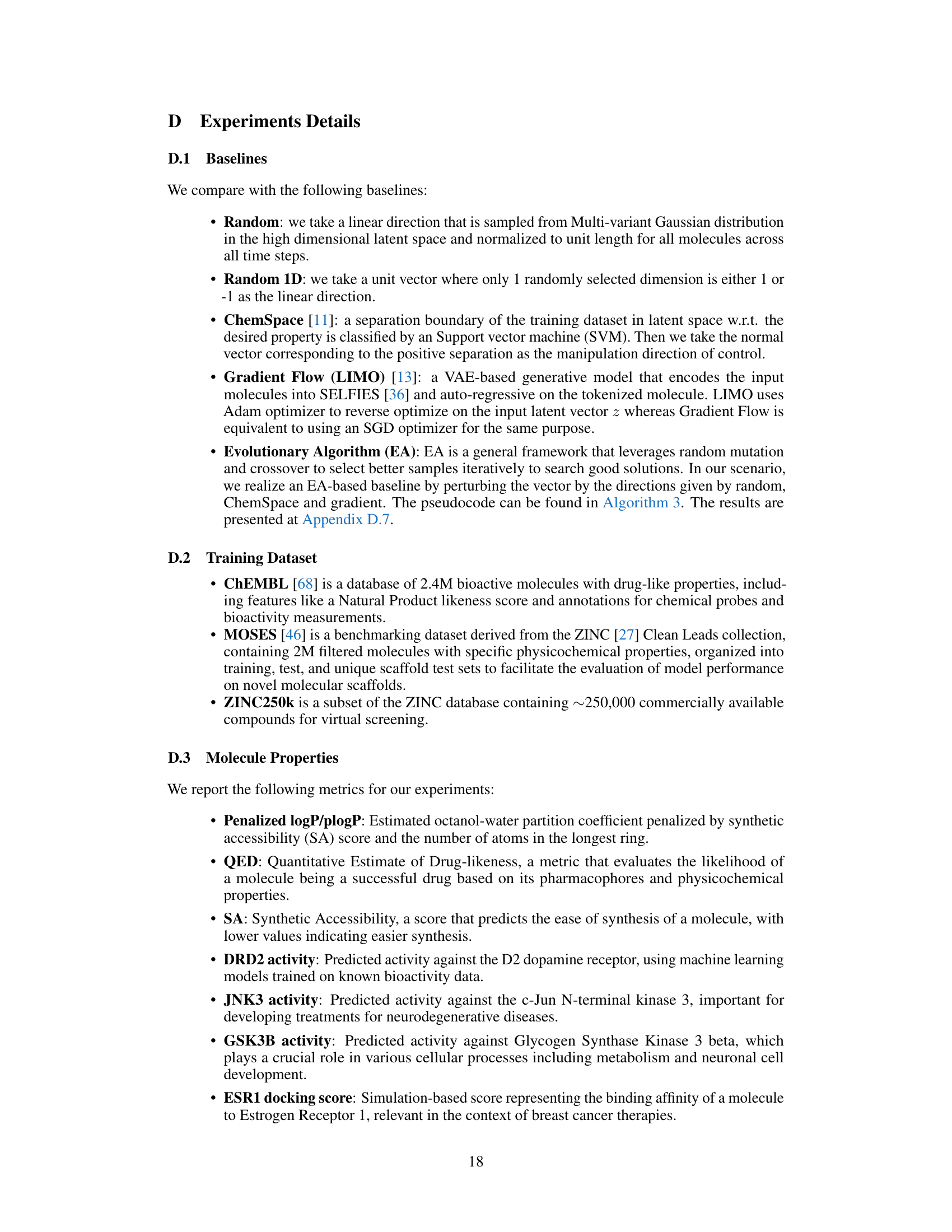

More visual insights#

More on figures

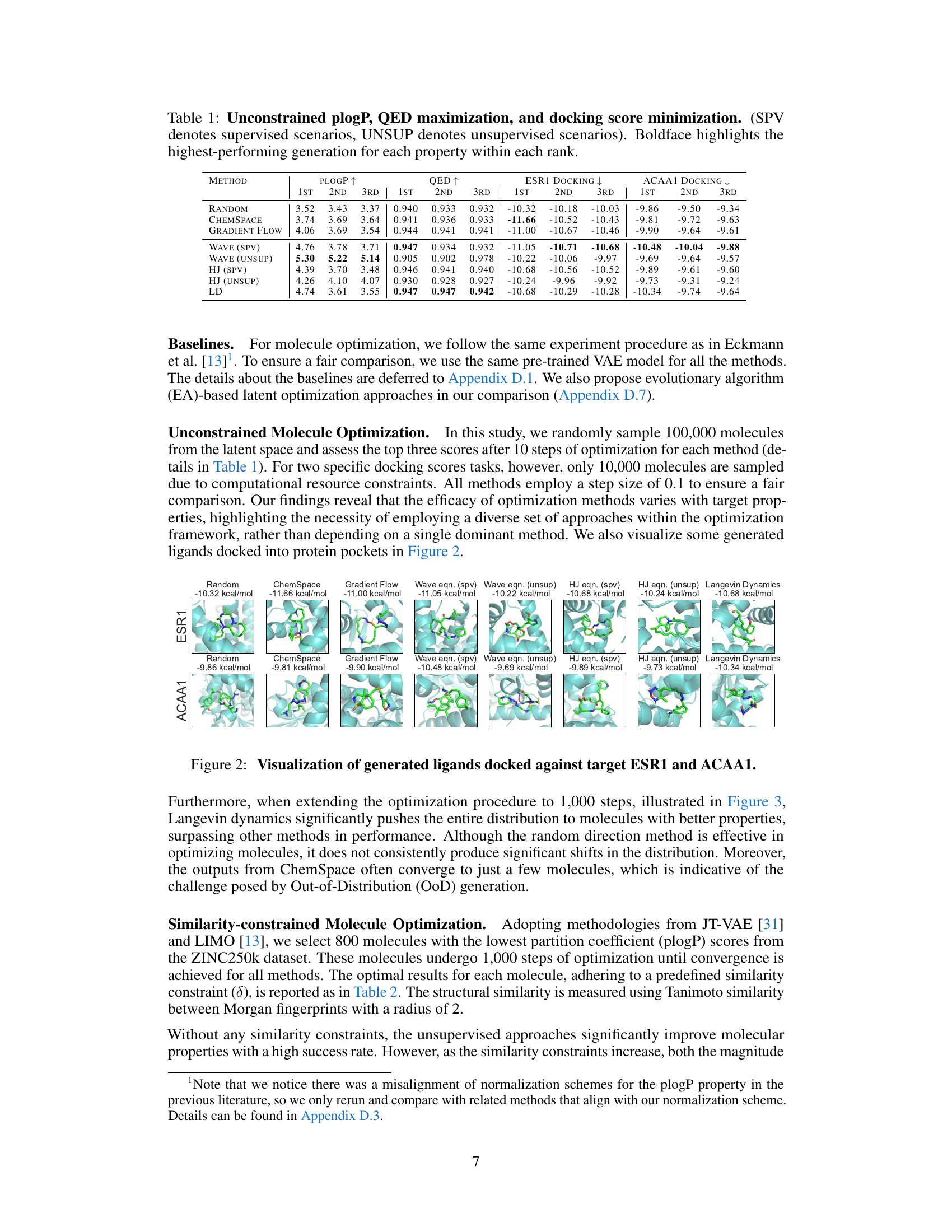

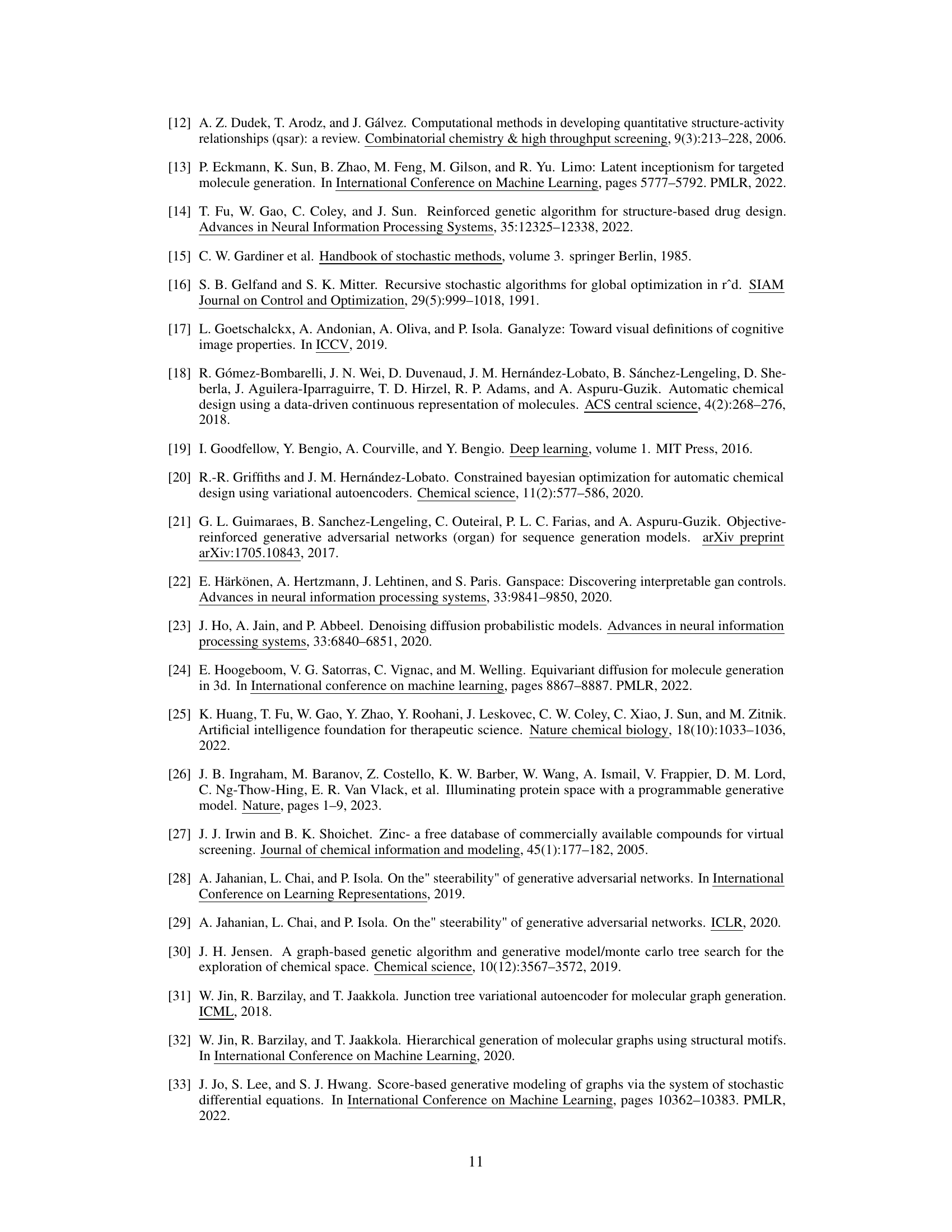

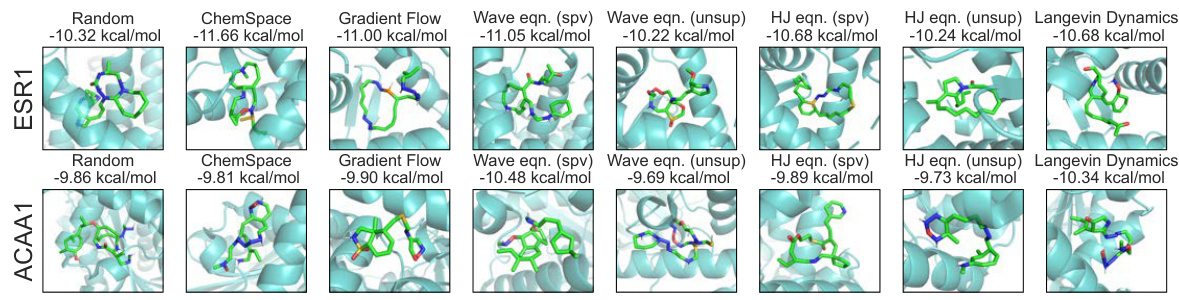

This figure visualizes the generated ligands docked against the target proteins ESR1 and ACAA1. Each column represents a different method used for molecule generation (Random, ChemSpace, Gradient Flow, Wave equation (supervised and unsupervised), Hamilton-Jacobi equation (supervised and unsupervised), and Langevin Dynamics). The images show the generated ligands (in green) docked into the binding pocket of the respective target proteins (in cyan/light blue). The docking scores (in kcal/mol) for each generated ligand are displayed above each image, illustrating the binding affinity achieved by each generation method. Lower scores indicate stronger binding.

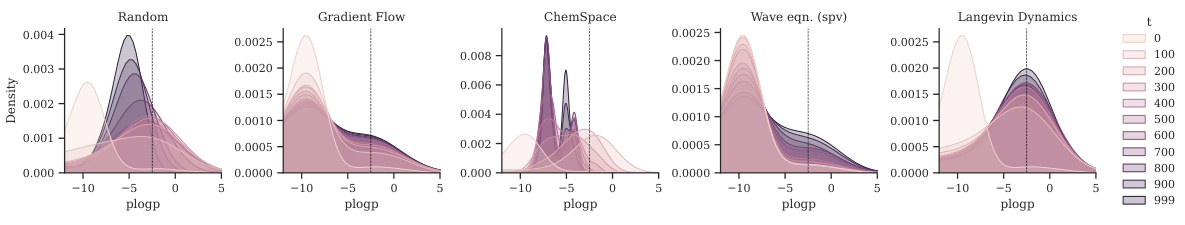

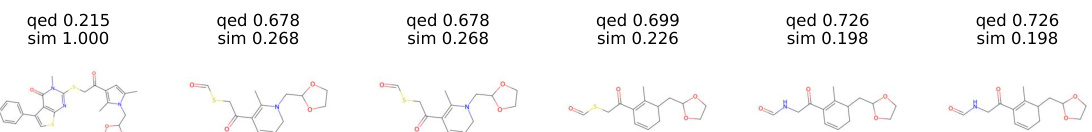

This figure visualizes the distribution shift of the plogP property during the optimization process using different methods. Each subfigure represents a method (Random, Gradient Flow, ChemSpace, Wave equation (supervised), Langevin Dynamics). Within each subfigure, the curves represent different time steps during the optimization, showing how the distribution of plogP values changes over time for each method. The figure demonstrates the varying effectiveness of each method in shifting the distribution of plogP towards molecules with desired properties.

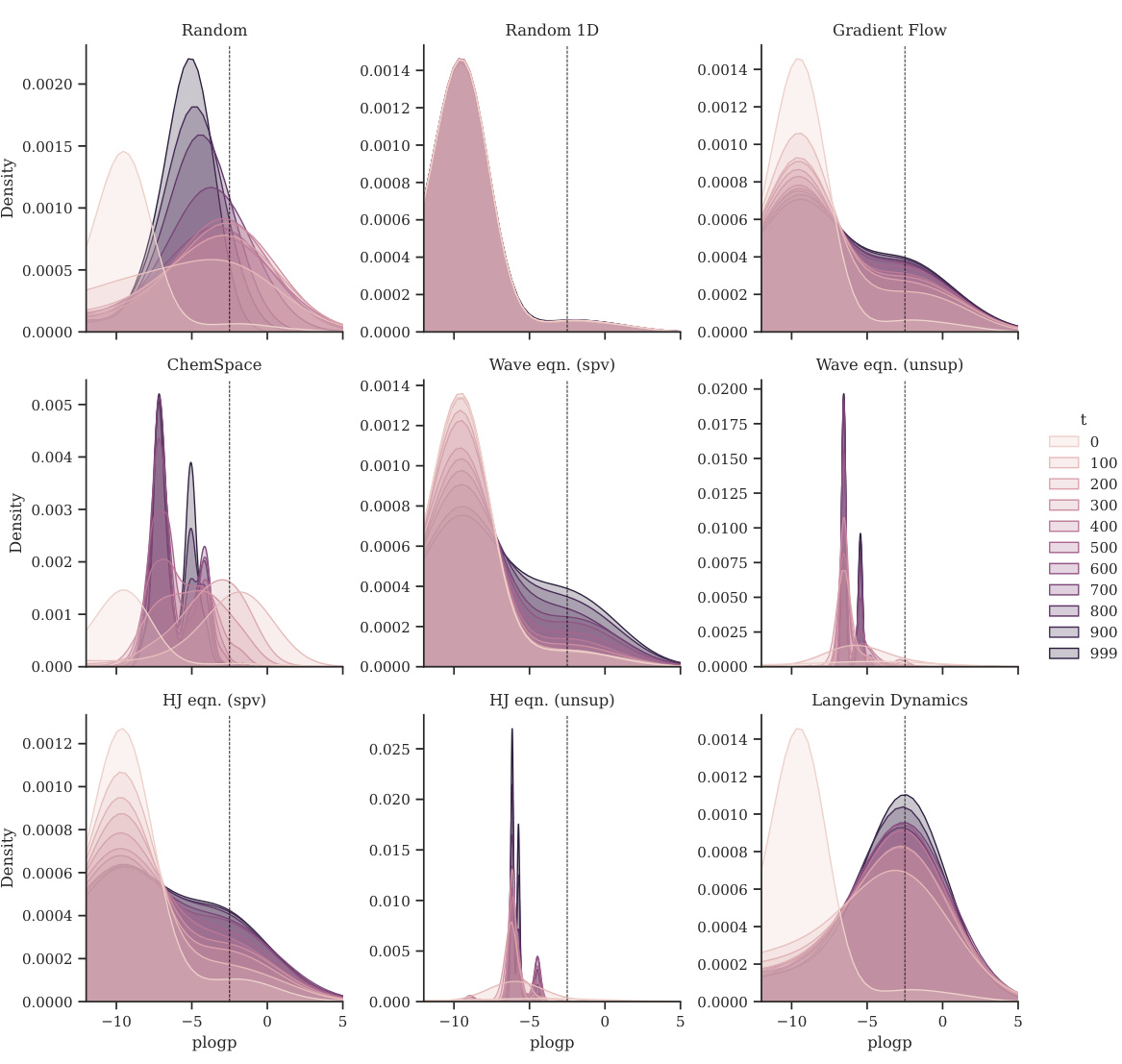

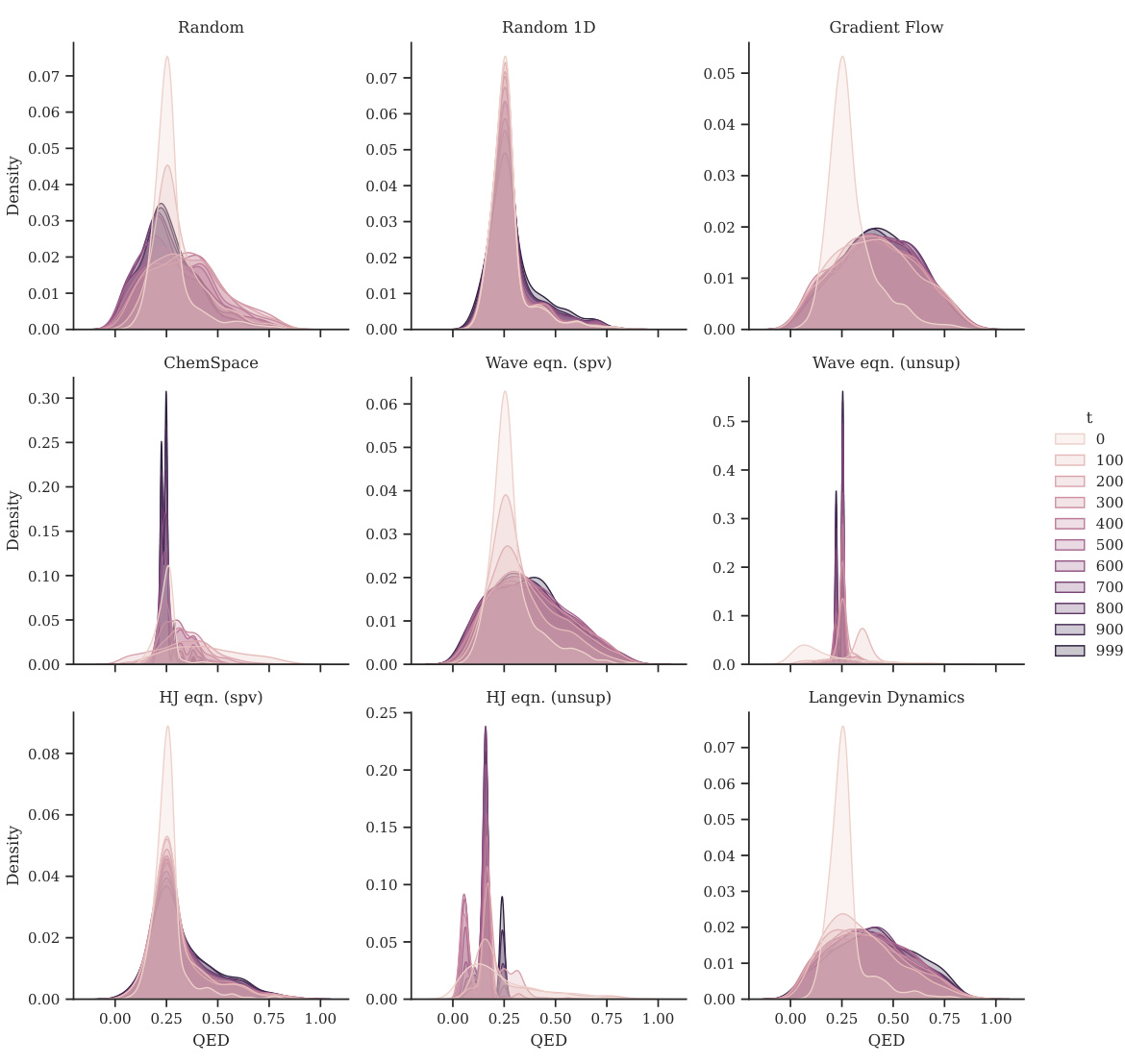

This figure shows the distribution shift of plogP for different optimization methods. Each panel represents a different method (Random, Random 1D, Gradient Flow, ChemSpace, Wave equation (supervised), Wave equation (unsupervised), Hamilton-Jacobi equation (supervised), Hamilton-Jacobi equation (unsupervised), and Langevin Dynamics). Within each panel, multiple density curves show the evolution of the plogP distribution over time (at various steps 0, 100, 200…999). The figure demonstrates how each method affects the distribution of plogP during the optimization process.

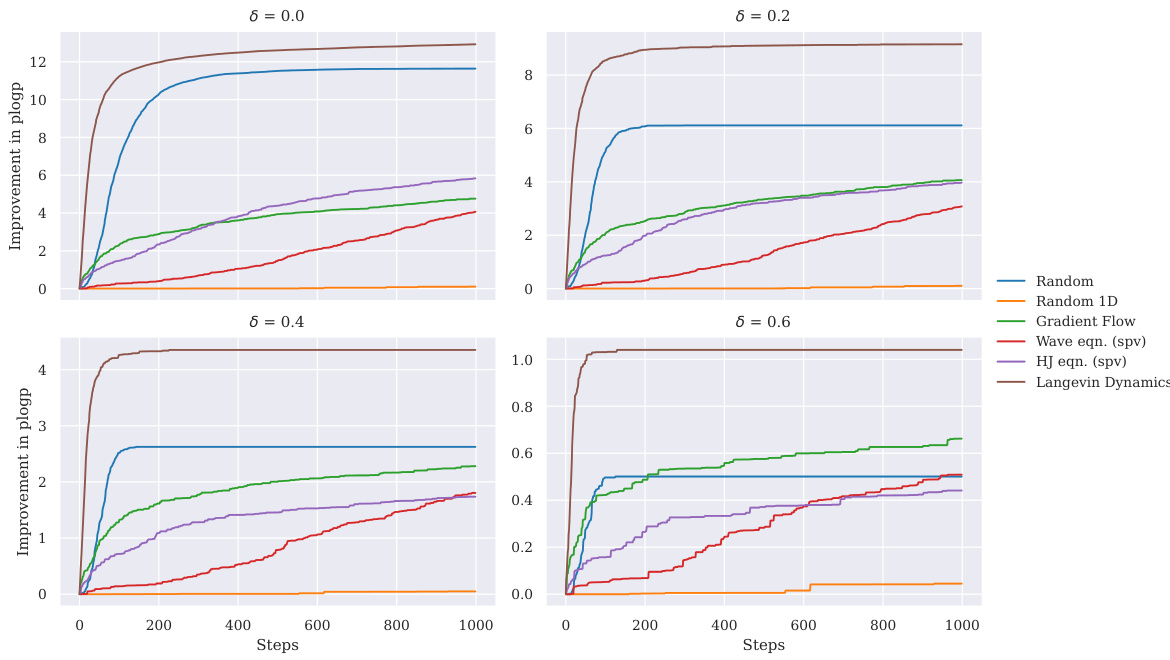

This figure displays the convergence speed of different optimization methods across various similarity constraints. The y-axis represents the improvement in plogP (a molecular property) over steps, and the x-axis represents the number of optimization steps. The plot demonstrates that Langevin Dynamics consistently outperforms other methods in achieving faster convergence and greater improvement in plogP, especially at higher similarity constraints.

This figure shows the distribution shift of plogP for different optimization methods at various time steps. It illustrates how the distribution of the plogP values changes as each optimization method progresses. The plots visualize the distributions of plogP at different time points for each method, allowing for a visual comparison of their effectiveness and convergence behavior. The x-axis represents the value of plogP and the y-axis represents the density.

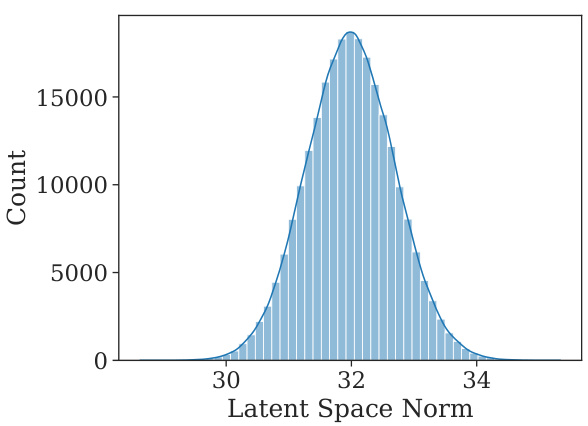

This figure shows the distribution of the norms of the latent vectors obtained by projecting the molecules from the training dataset into the learned latent space. The distribution closely resembles a normal distribution centered around 32, which is approximately the square root of the latent space dimension (1024). This observation suggests that the learned latent space exhibits a structure that allows for smooth traversal and manipulation of molecules through simple linear combinations of latent vectors.

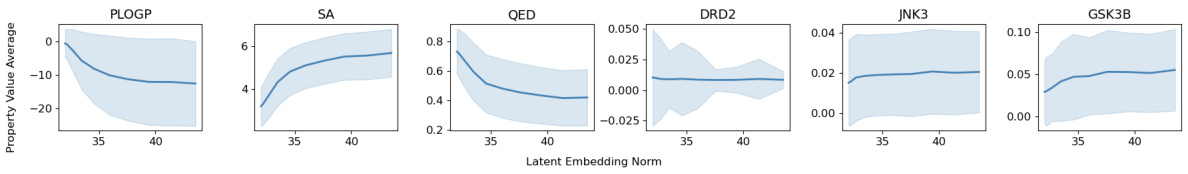

This figure shows the relationship between the latent vector norm and molecular properties along the trajectory of latent traversal. Each line represents a different trajectory obtained by traversing along a random direction in the latent space. The shaded area indicates the standard deviation of the property values for each norm, showing the variability of the properties at a given norm. The middle curve shows the average values of the property and latent vector norm for all trajectories.

This figure shows the relationship between the norm of the latent vector and the property values along a random traversal path. Each point represents a molecule along the path, and the plot shows the average property value and latent embedding norm, with the shaded area representing the standard deviation. The figure helps to illustrate how changes in latent space relate to changes in molecular properties.

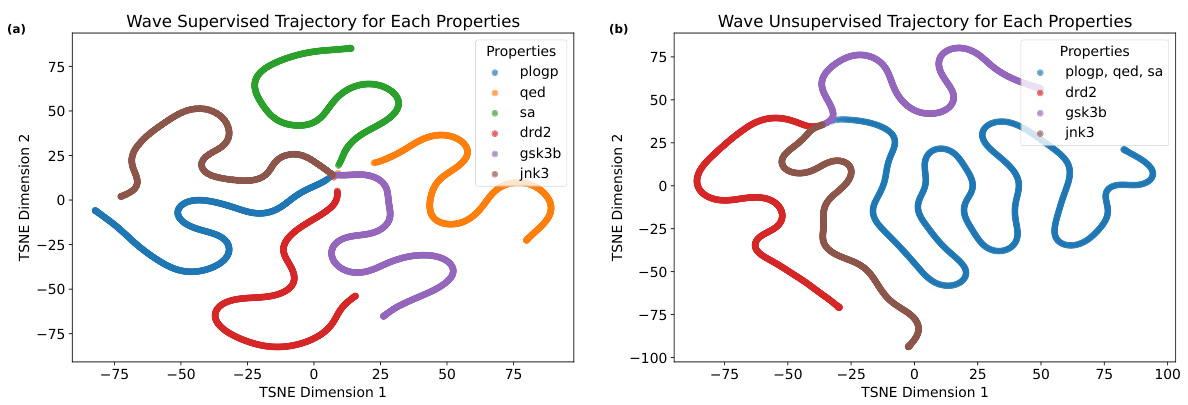

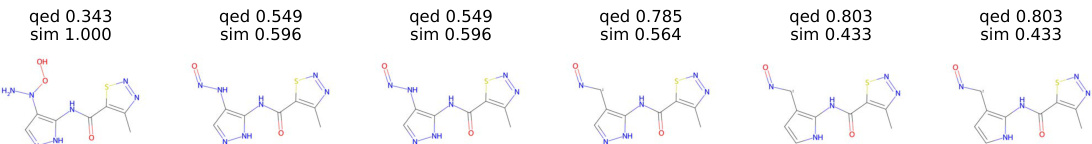

This figure visualizes the optimization trajectories in the latent space using t-SNE for both supervised and unsupervised wave flows. Each line represents the trajectory for a different molecular property (plogP, QED, SA, DRD2, JNK3, GSK3B). The supervised trajectories show a more focused and directed optimization towards the target property, while the unsupervised trajectories exhibit more exploration and variation in the latent space.

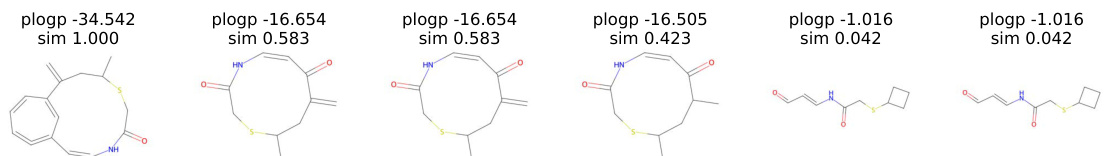

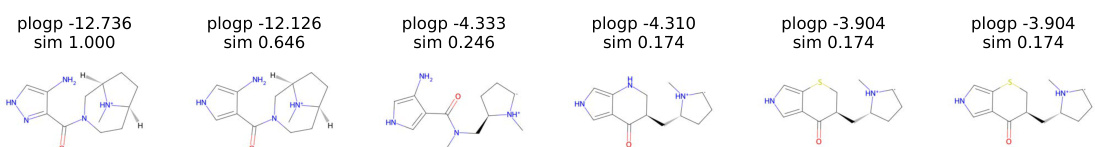

This figure shows the results of a molecule manipulation experiment using the ChemSpace method to optimize the plogP property. It displays a series of six molecules, showing how the structure changes over six steps, while maintaining a decreasing level of similarity to the original molecule (sim). The plogP values illustrate the improvement in the property during the manipulation process.

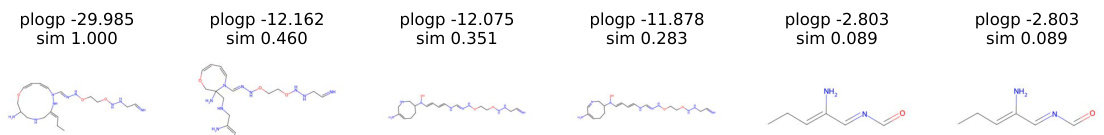

This figure displays the trajectory of molecular manipulation using gradient flow to optimize plogP. It shows a series of molecules generated during the manipulation process. Each molecule shows the changes in structure from the original molecule to the final molecule, with the plogP value and similarity score calculated for each step.

This figure visualizes the optimization trajectories obtained using both supervised and unsupervised wave flows. The trajectories are plotted in a 2D t-SNE embedding space, allowing for the visualization of the path taken during optimization. It shows how the optimization progresses through the latent space, potentially revealing insights into the process and the relationship between the latent space and molecular properties.

This figure visualizes the optimization trajectory of molecules using random direction in the latent space to maximize plogP. It shows a series of molecules generated during the optimization process. Each molecule is annotated with its plogP value and similarity to the starting molecule. The trajectory illustrates how the random direction method explores the chemical space to find molecules with improved plogP values.

This figure visualizes the optimization trajectories in the t-SNE reduced latent space for both supervised and unsupervised settings using the wave flow. Each line represents the trajectory of molecules optimized for a specific property, offering a visual comparison of how the different approaches navigate the latent space during the optimization process.

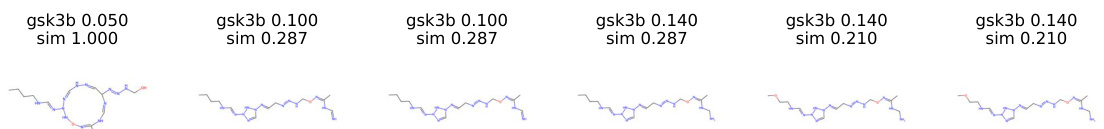

This figure shows the optimization trajectory of six molecules when optimizing the QED property using the supervised Hamilton-Jacobi flow. Each molecule in the trajectory represents a snapshot of the optimization process at a specific time step, showing the gradual evolution of the molecule’s structure. The QED values of each molecule are provided above its structure, illustrating the improvement in QED over time.The similarity between consecutive molecules is indicated by ‘sim’ values. The values decrease as molecules evolve, suggesting structural diversity.

More on tables

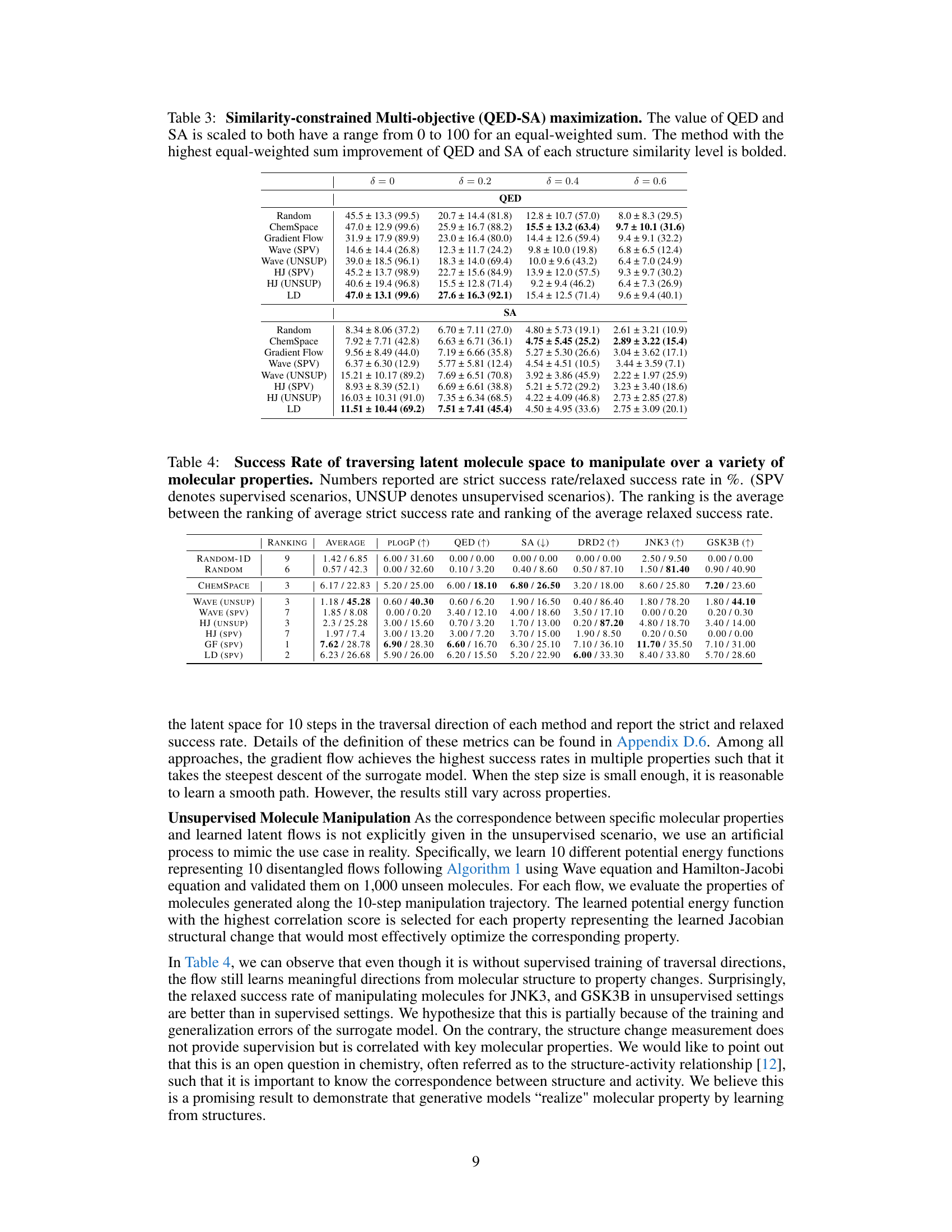

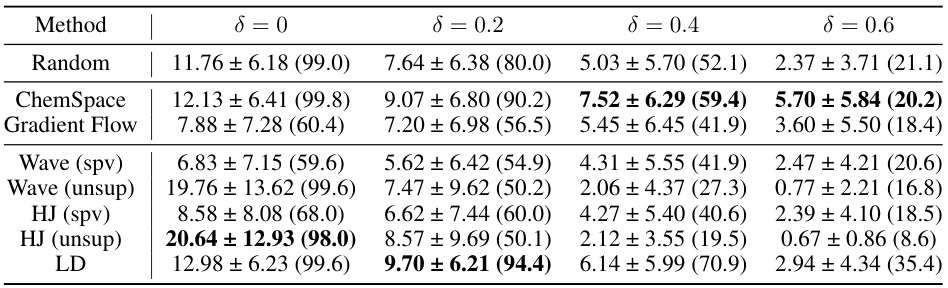

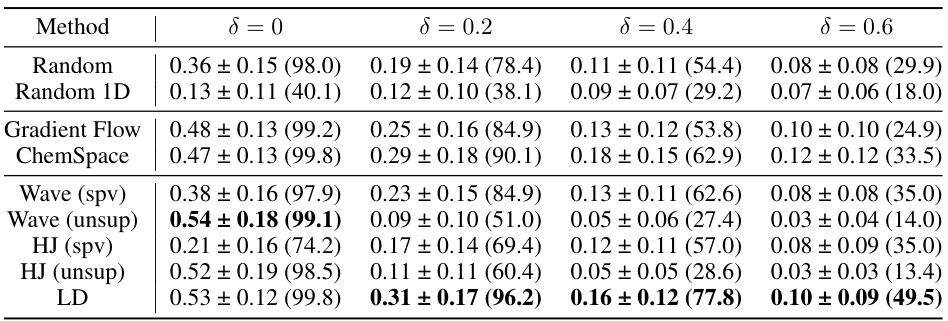

This table presents the results of similarity-constrained plogP maximization experiments. For various similarity constraints (δ = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6), it shows the mean and standard deviation of the absolute improvement in plogP achieved by each method, along with the success rate (percentage of molecules satisfying the similarity constraint). The table compares the performance of different molecule optimization methods.

This table presents the results of unconstrained molecule optimization experiments for various molecular properties (plogP, QED, and docking scores for ESR1 and ACAA1). It compares the performance of different methods including Random, ChemSpace, Gradient Flow, Wave (supervised and unsupervised), HJ (supervised and unsupervised), and Langevin Dynamics. The table shows the top three scores (1st, 2nd, 3rd) achieved by each method after 10 optimization steps. Boldfaced values indicate the best performance for each property.

This table presents the results of unconstrained molecule optimization experiments for various molecular properties (plogP, QED, and docking scores for ESR1 and ACAA1). The table compares several methods, including baselines and the proposed ChemFlow framework with different variants. Results are shown for the top 3 scores, indicating the performance of each method in maximizing or minimizing the target properties. The ‘best’ results are highlighted in bold.

This table shows the results of single-objective maximization experiments using the PDE-regularized latent space learning method. It compares the performance of different methods (WAVE (UNSUP), HJ (UNSUP), WAVE (UNSUP FT)) for maximizing plogP and QED, showing the top 3 scores obtained for each metric. The number of energy networks (K) used in unsupervised training is also specified.

This table presents the results of unconstrained molecule optimization experiments for various molecular properties. It compares several methods (including baselines like Random and ChemSpace, and the proposed ChemFlow method with different flow types and supervision levels) by showing the top three scores achieved after 10 steps of optimization for each method. The properties optimized include plogP (maximization), QED (maximization), and docking scores for ESR1 and ACAA1 (minimization). The best performing method for each property is highlighted in bold.

This table presents the results of unconstrained optimization experiments for three molecular properties: plogP (maximization), QED (maximization), and docking scores for ESR1 and ACAA1 (minimization). It compares the performance of several methods, including ChemSpace, Gradient Flow, and different variations of the ChemFlow approach (with supervised and unsupervised guidance, using various flow types). The results show the best (1st, 2nd, 3rd) scores achieved by each method across 100,000 randomly sampled molecules (10,000 for docking scores). Boldface highlights the best result achieved within each rank for each property.

This table presents the results of unconstrained molecule optimization experiments. Several methods (Random, ChemSpace, Gradient Flow, Wave, HJ, LD) are compared across three objectives: maximizing plogP and QED, and minimizing docking scores for ESR1 and ACAA1. The table shows the top three scores (1st, 2nd, 3rd) for each property achieved by each method. Boldface numbers highlight the best result achieved for each property within each ranking. The results show varying performance across different methods and objectives.

This table presents the results of unconstrained molecule optimization for plogP and QED maximization, and docking score minimization using different methods. It shows the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd best scores obtained for each property using various methods including Random, ChemSpace, Gradient Flow, and different versions of ChemFlow (with supervised and unsupervised settings). The best performing method for each property and rank is highlighted in bold.

This table presents the results of unconstrained molecule optimization for various molecular properties (plogP, QED, and docking scores for ESR1 and ACAA1). It compares different methods, including baselines (Random, ChemSpace), and ChemFlow variants (Gradient Flow, Wave, HJ, Langevin Dynamics), under both supervised (SPV) and unsupervised (UNSUP) settings. The best-performing method for each property is highlighted in bold for each ranking position (1st, 2nd, 3rd).

This table presents the results of unconstrained optimization experiments for three molecular properties: plogP (maximized), QED (maximized), and docking scores for ESR1 and ACAA1 (minimized). Different methods, including baselines (Random, ChemSpace, Gradient Flow) and the proposed ChemFlow with various configurations (Wave, HJ, LD, with both supervised and unsupervised settings), are compared. The table shows the top three scores (1st, 2nd, 3rd) achieved by each method for each property, highlighting the best-performing method in boldface.

Full paper#