↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Text-to-image diffusion models, while powerful, lack transparency, making bias detection and control difficult. Understanding how these models process visual-semantic relationships is crucial for improvement. Existing methods offer limited insight into the complex interplay between individual words and their combined effect on image generation.

DiffusionPID addresses this by applying partial information decomposition, breaking down prompts into their unique, redundant, and synergistic components. This novel technique helps pinpoint how individual tokens and their interactions influence the final image, revealing biases, ambiguity, and synergy within the model. It provides a fine-grained analysis of model characteristics and enables effective prompt intervention, leading to more reliable and controllable image generation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with text-to-image diffusion models because it introduces DiffusionPID, a novel technique for interpreting these models’ inner workings. This method enhances our understanding of how these models handle complex prompts, visualize biases, and improve model control, paving the way for building more robust and interpretable AI systems. Its information-theoretic approach offers a novel perspective for analyzing model dynamics, which is highly relevant to current interpretability research.

Visual Insights#

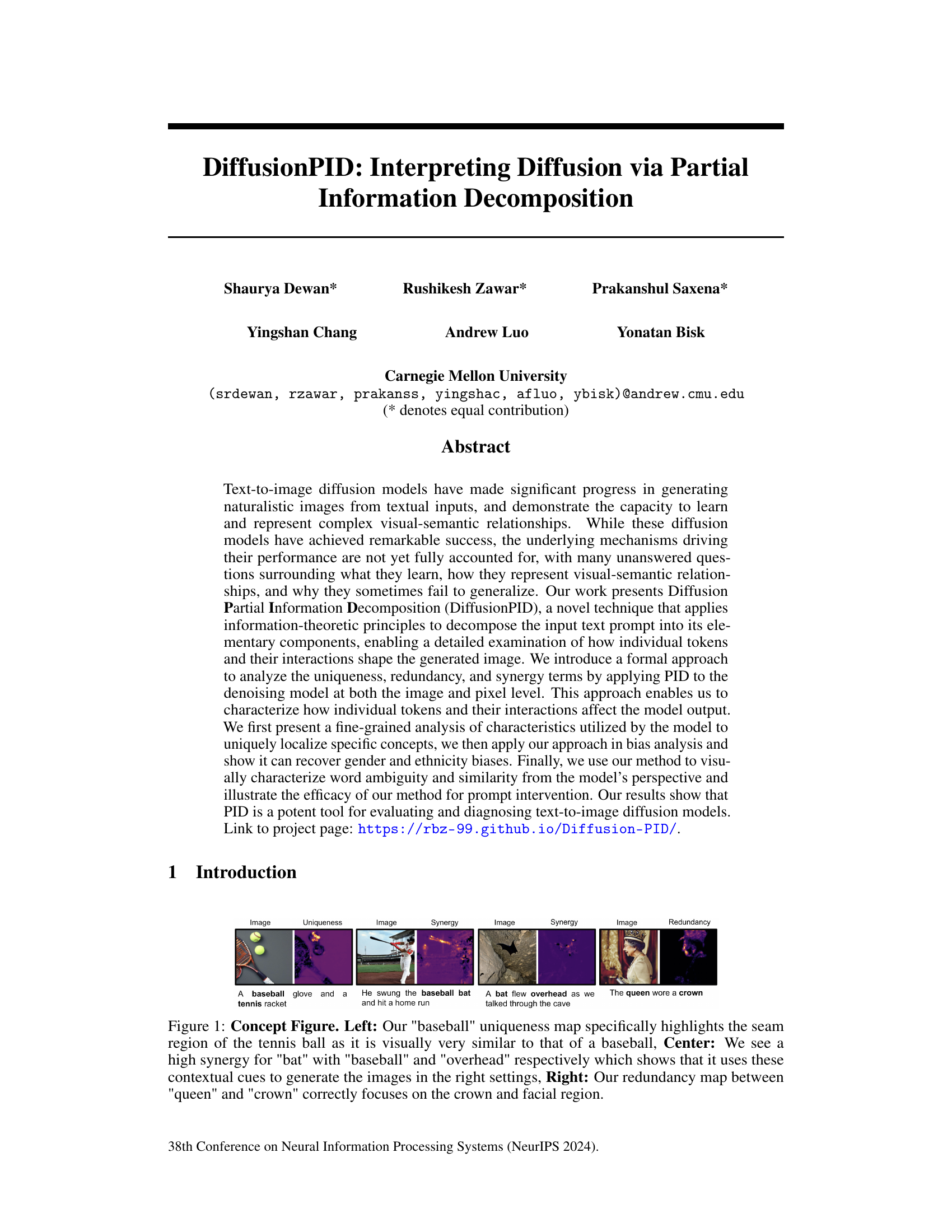

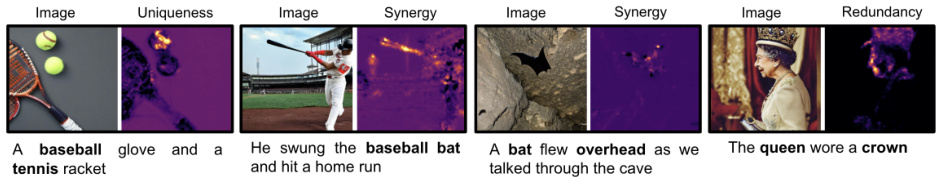

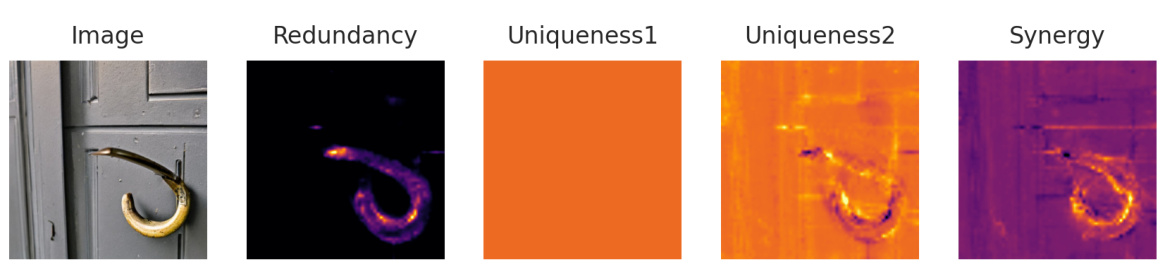

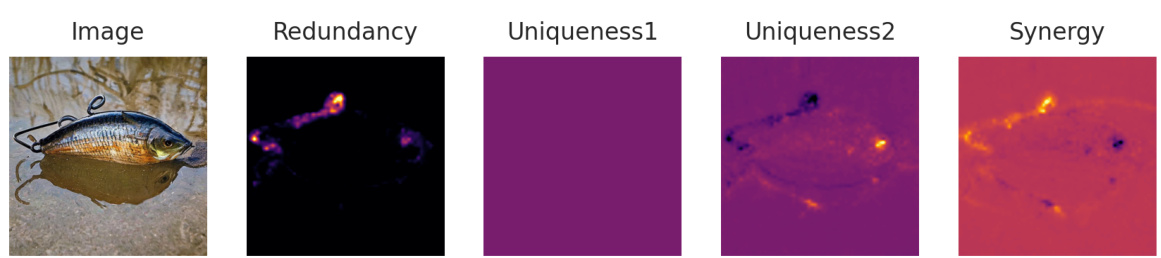

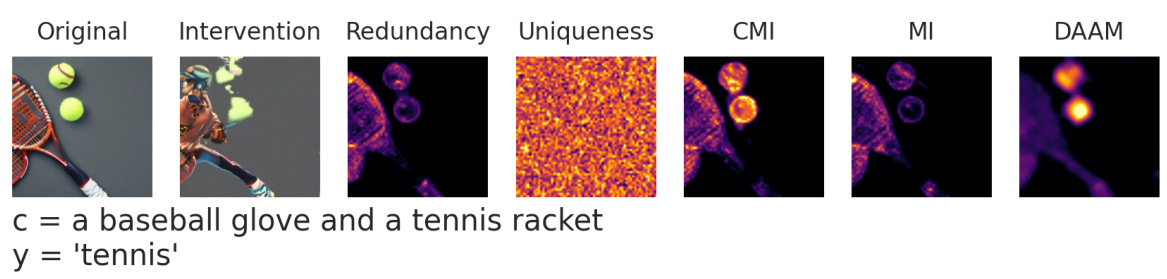

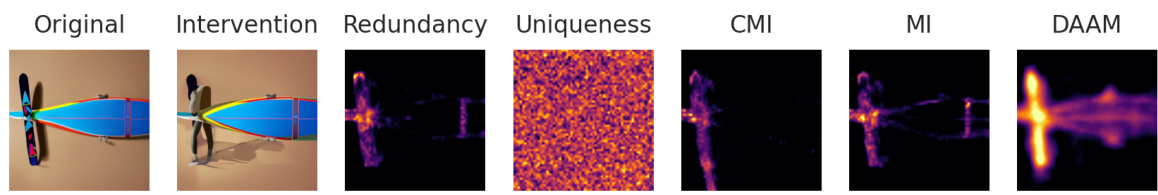

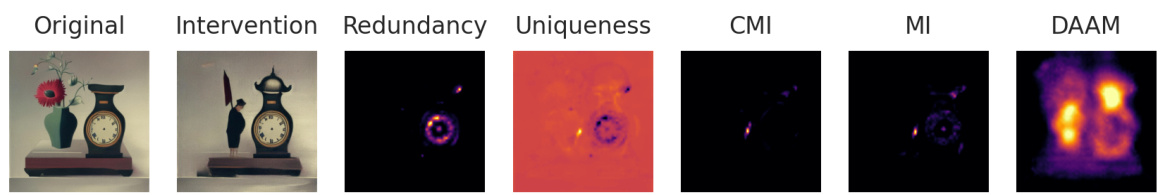

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the DiffusionPID method in interpreting the relationships between different components of text prompts and the resulting images. It shows that DiffusionPID successfully identifies visual similarities, such as the seam of a tennis ball being similar to that of a baseball (Uniqueness), the contextual relationships between words (Synergy), and redundant information (Redundancy) within a prompt, providing insights into how the diffusion model processes the information to generate the final image.

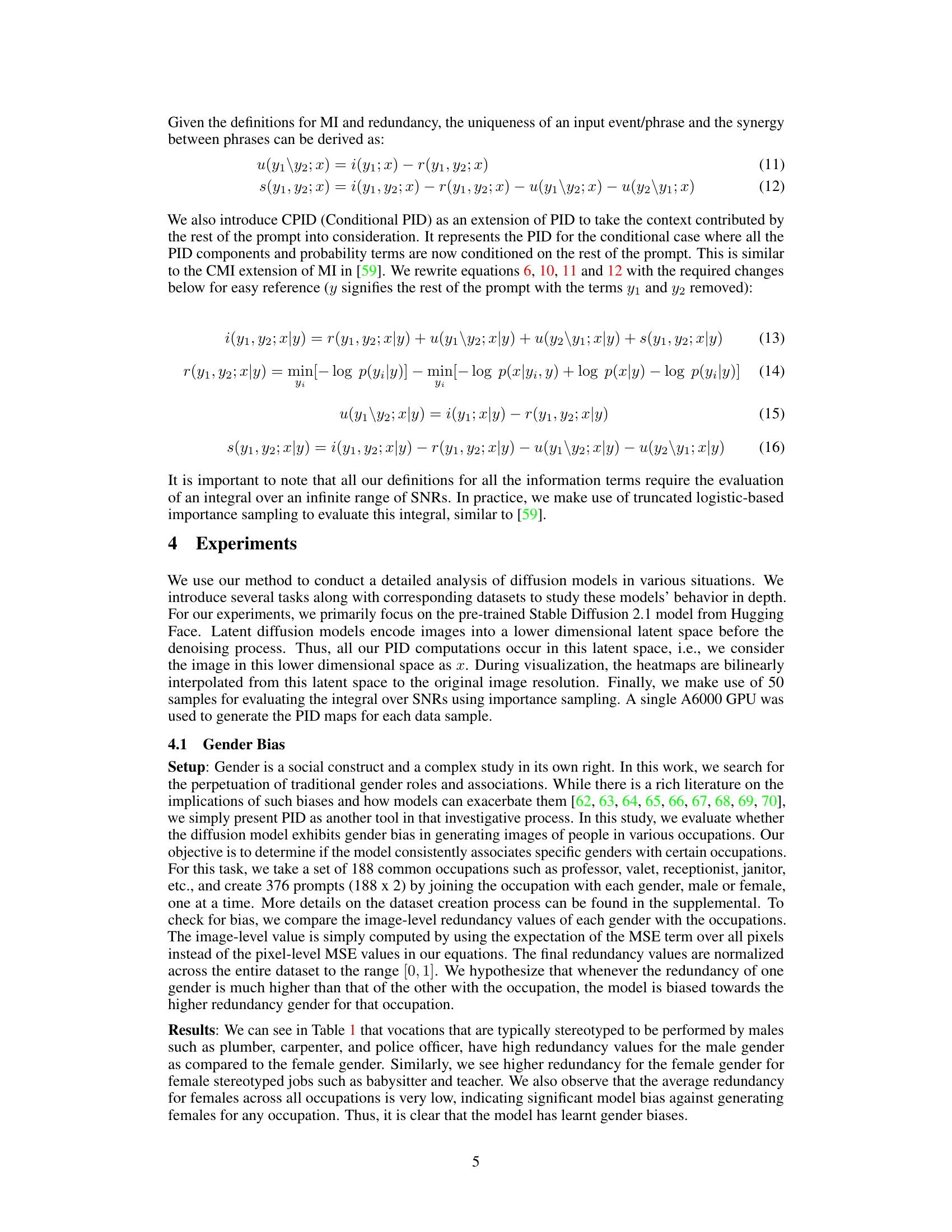

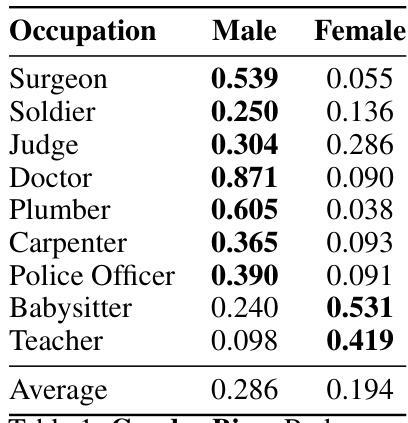

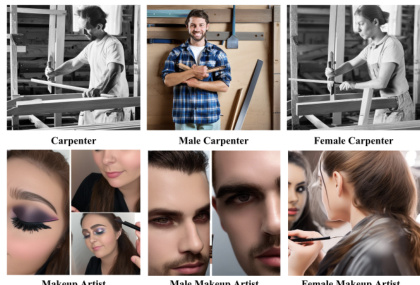

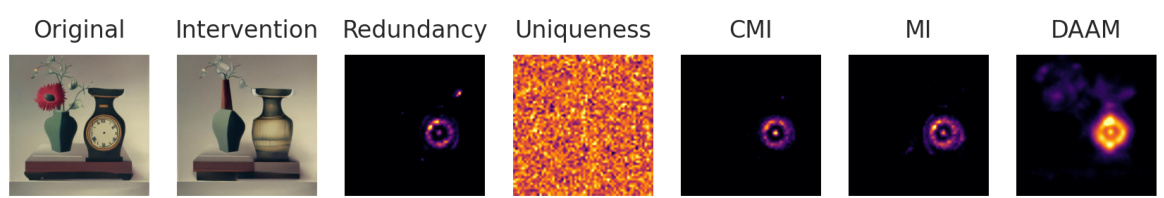

This table presents the results of an experiment investigating gender bias in a diffusion model. For a set of 188 common occupations, the model generated images using prompts that included the occupation paired with either ‘male’ or ‘female.’ The table shows the redundancy values, which are normalized across the entire dataset to the range [0, 1], for each gender and occupation. High redundancy indicates that the model strongly associates a particular gender with a given occupation, suggesting gender bias. Lower redundancy suggests less association.

In-depth insights#

DiffusionPID Intro#

The hypothetical “DiffusionPID Intro” section would likely introduce the core concept of DiffusionPID, a novel technique for interpreting the inner workings of text-to-image diffusion models. It would emphasize the lack of transparency in these models, highlighting the need for methods to understand their decision-making processes. The introduction would then position DiffusionPID as a solution, emphasizing its use of partial information decomposition (PID) from information theory. This section would likely also briefly describe how DiffusionPID analyzes the input text prompt, decomposing it into its constituent parts to reveal the individual and combined contributions of different tokens to the generation of the image. Uniqueness, redundancy, and synergy between tokens would be mentioned as key aspects of the analysis. Finally, a high-level overview of the paper’s structure and the benefits of using DiffusionPID, such as improved model evaluation and bias detection, would likely be presented, piquing the reader’s interest and setting the stage for the detailed methodology and experimental results to come.

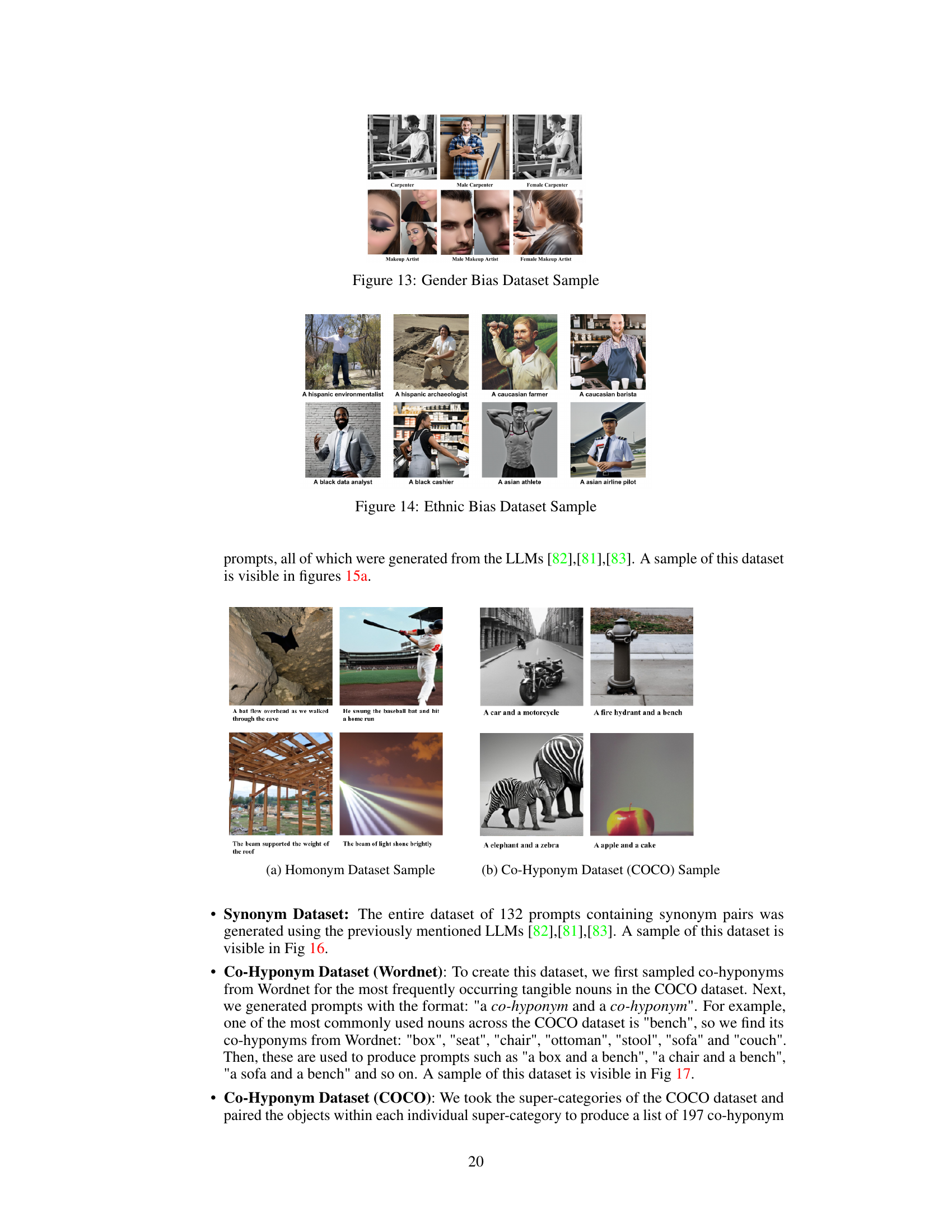

PID Methodology#

A PID (Partial Information Decomposition) methodology for interpreting diffusion models would involve using PID to analyze the informational relationships between input text prompts and generated images. This would go beyond simply measuring mutual information, offering a nuanced understanding of how individual words, phrases, and their interactions contribute to the final output. The core of the method would likely involve decomposing the mutual information into unique, redundant, and synergistic components at both the image and pixel levels. Unique information would highlight aspects of the image uniquely explained by specific text elements, redundancy would identify overlapping information across different parts of the prompt, and synergy would reveal how interactions between prompt elements generate novel visual information. By visualizing these components, one can gain crucial insights into the model’s internal reasoning process and identify potential sources of bias or ambiguity. A crucial aspect would be considering context; how the presence or absence of certain words in the prompt affects the contributions of other words. This technique could offer valuable insights into the model’s behavior, aiding in its evaluation, diagnosis, and improvement. It also has the potential to guide prompt engineering by identifying redundant or underutilized elements.

Bias Experiments#

The section on bias experiments in this research paper is crucial for evaluating the fairness and trustworthiness of the studied diffusion models. The experiments likely involve analyzing the model’s output for systematic biases related to gender and ethnicity. Careful selection of prompts and occupations associated with stereotypical gender roles would be critical. Quantitative measures like redundancy, uniqueness, and synergy (derived using Partial Information Decomposition - PID) will likely be used to assess how strongly the model associates certain attributes with specific genders or ethnicities. The results might reveal imbalances, highlighting the extent to which the models perpetuate societal biases. This evaluation should not only identify the presence of bias but also investigate its magnitude and its effect on image generation. Visualizations of PID components (heatmaps) might be included to illustrate the model’s biases in a more intuitive way. Furthermore, the study might also assess whether prompt engineering techniques are able to mitigate or exacerbate these biases.

Future of PID#

The future of Partial Information Decomposition (PID) is bright, promising deeper insights into complex systems. Methodological advancements are crucial; refining existing PID measures to handle high-dimensional data and non-linear relationships will unlock applications in diverse fields. Expanding beyond pairwise interactions to analyze the information dynamics of larger ensembles of variables is vital, requiring new theoretical frameworks and computational techniques. Developing efficient algorithms is paramount to enable large-scale applications of PID. Bridging PID with other information-theoretic tools such as causal inference and network analysis will provide a holistic perspective on system behavior, enabling more comprehensive understanding. Interdisciplinary collaborations will be essential for successfully applying PID across various scientific domains, from neuroscience and ecology to economics and climate science. Focus on interpretability will enhance PID’s adoption and impact, translating complex information-theoretic results into actionable knowledge.

Limitations#

A critical analysis of the ‘Limitations’ section in a research paper necessitates a nuanced understanding of its role. This section isn’t merely a list of shortcomings; it’s a demonstration of intellectual honesty and rigor. A well-written limitations section acknowledges methodological constraints, such as sample size or data biases. It also addresses potential limitations in generalizability, acknowledging that the findings might not apply universally across all contexts or populations. Furthermore, a strong limitations section preemptively addresses potential criticisms by acknowledging the study’s scope, and the boundaries of its claims. Transparency regarding limitations builds trust with the reader. A thoughtful analysis also assesses whether the limitations are acknowledged appropriately (i.e., are they appropriately contextualized and weighted relative to the paper’s contributions?) and whether the authors demonstrate awareness of how these limitations might impact the interpretation of their results and guide future research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure demonstrates the DiffusionPID method’s ability to highlight different aspects of semantic relationships between words in image generation. The left panel shows the uniqueness map for ‘baseball,’ emphasizing the visual similarity between a baseball and a tennis ball. The center panel displays the synergy map between ‘bat,’ ‘baseball,’ and ‘overhead,’ illustrating how the model uses contextual information for image generation. The right panel shows the redundancy map for ‘queen’ and ‘crown,’ highlighting the overlapping regions where both concepts are represented.

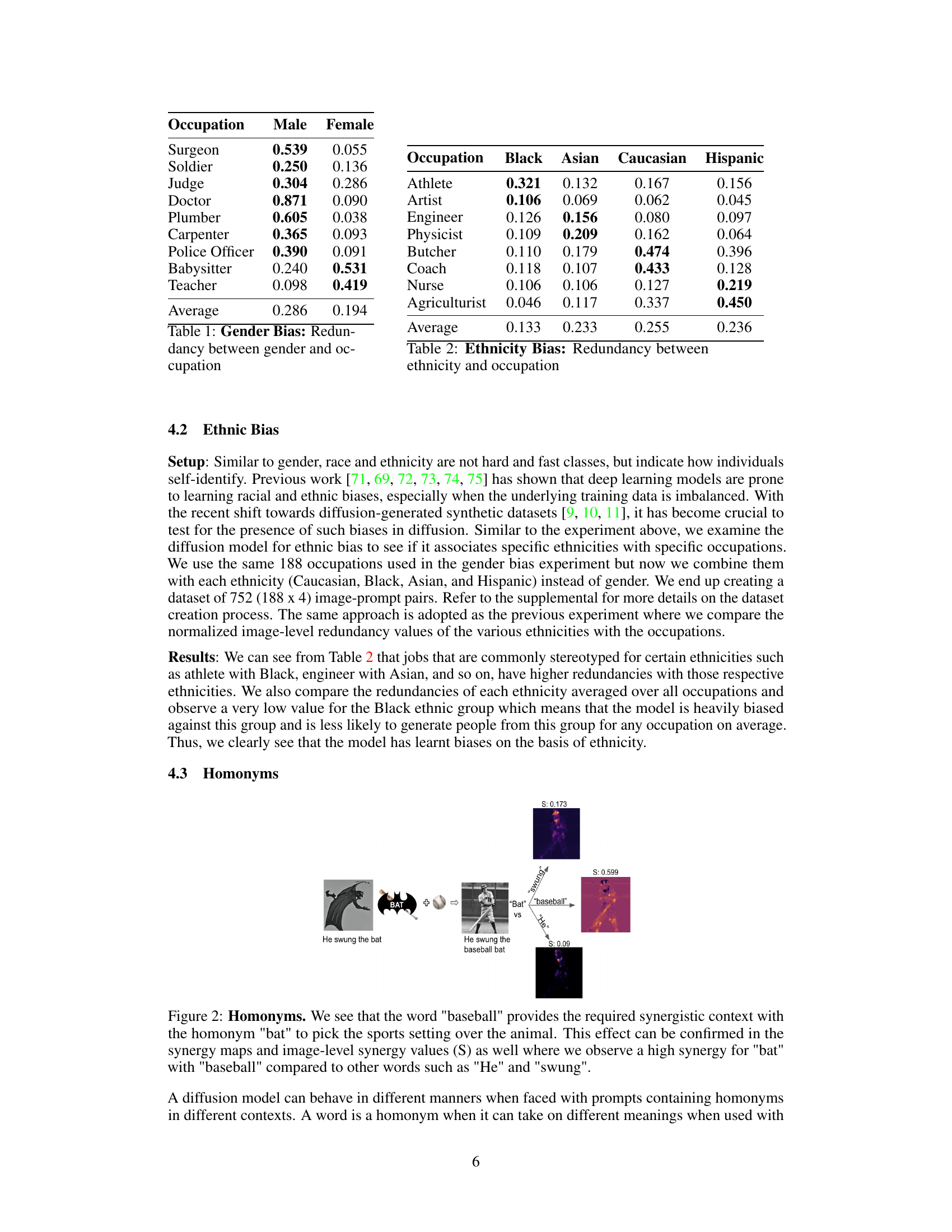

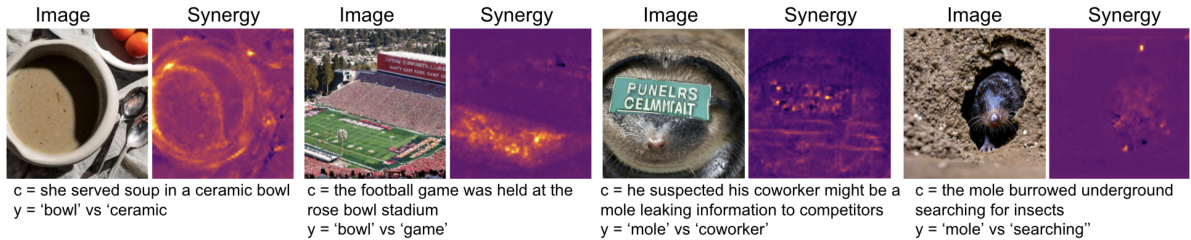

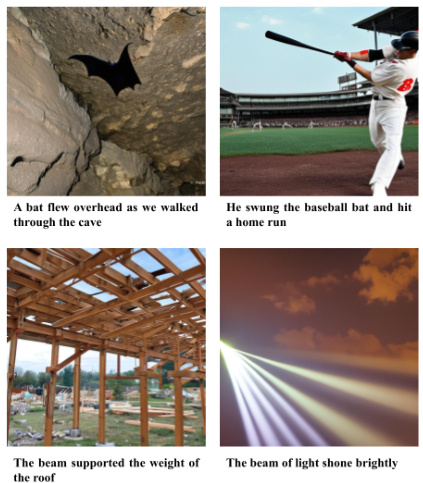

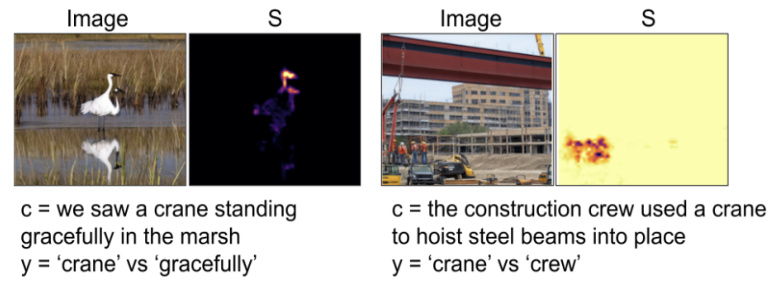

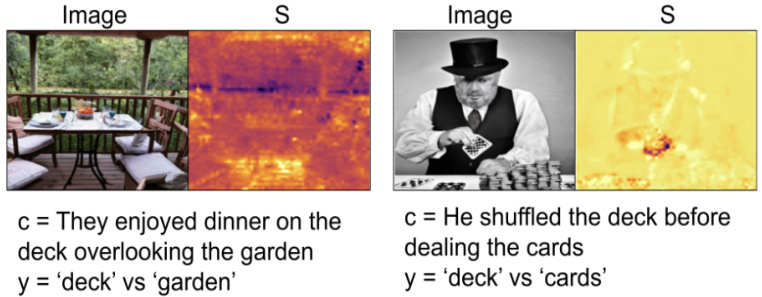

This figure demonstrates the application of the DiffusionPID method to analyze homonyms (words with multiple meanings) in text-to-image generation. The left panel shows a successful case where the model correctly interprets the context of the word ‘bowl’ (in ‘ceramic bowl’ and ‘rose bowl stadium’) based on its synergy with other words, leading to appropriate image generation. The right panel showcases a failure case where the model fails to distinguish between the different meanings of ‘mole’, generating an image of an animal (‘mole’ as a creature) instead of a person (‘mole’ as an undercover agent) due to lack of contextual synergy with words like ‘coworker’. The synergy maps visually highlight the model’s interpretation of word relationships.

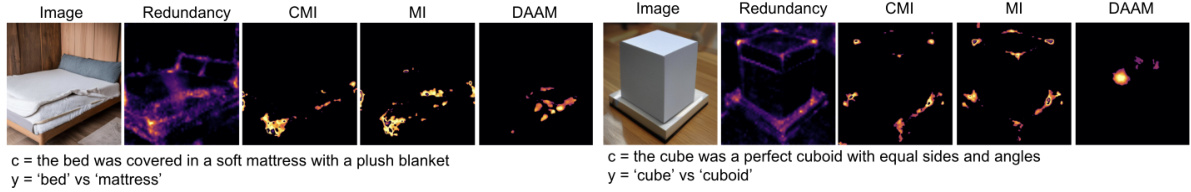

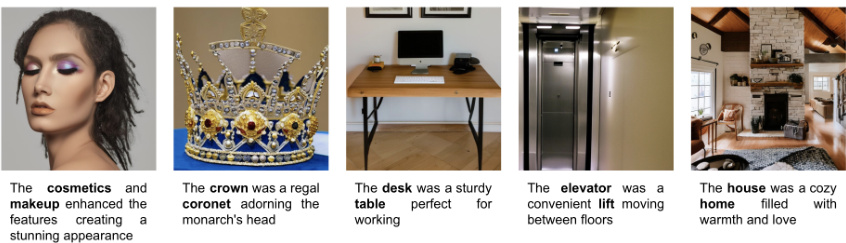

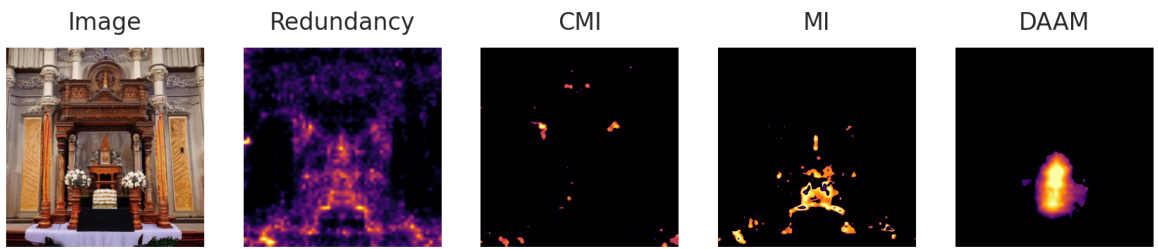

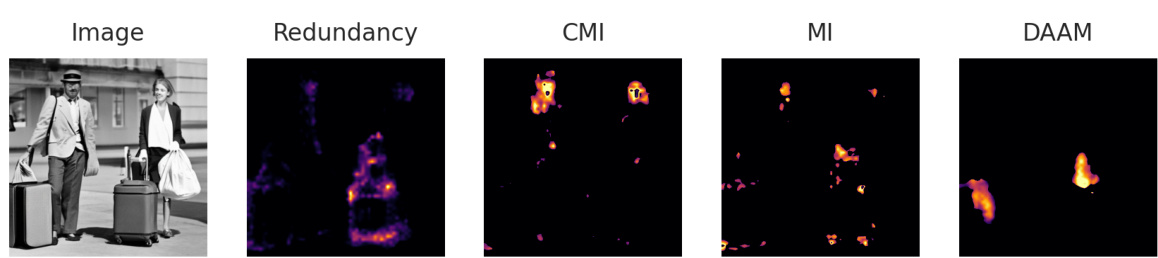

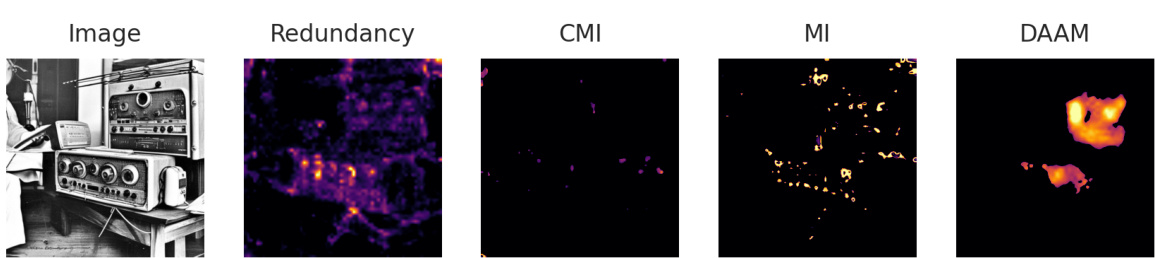

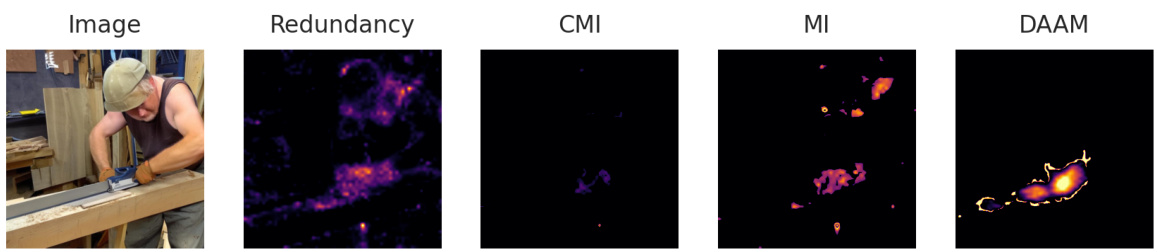

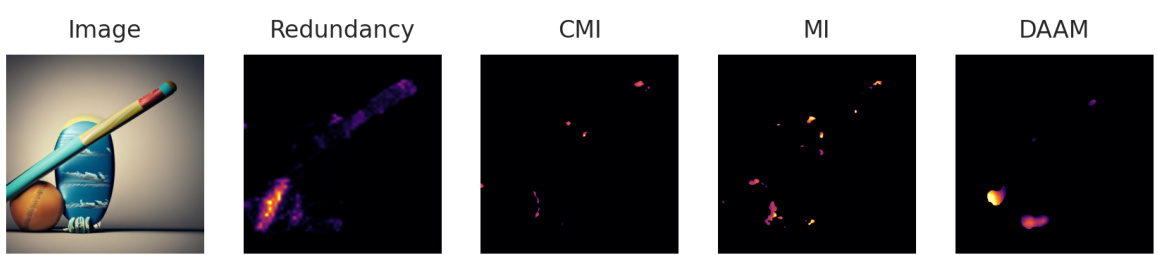

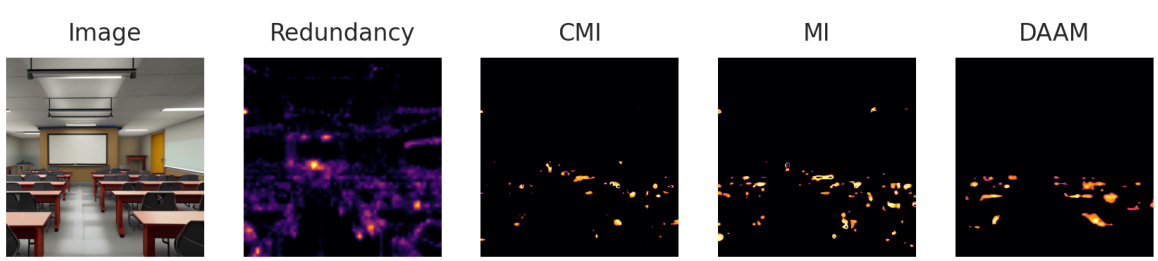

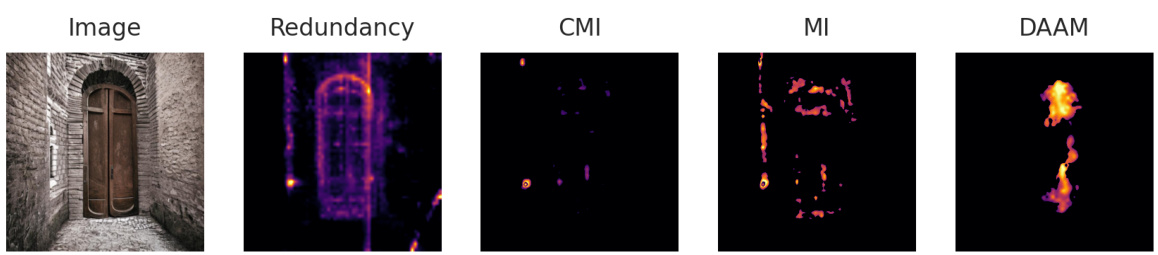

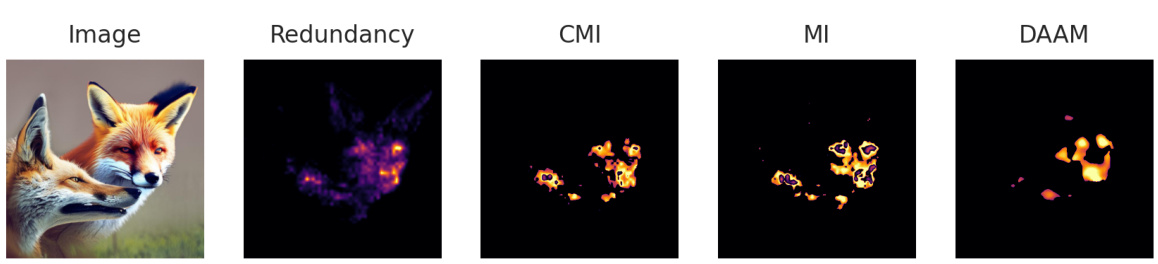

This figure showcases the results of applying the proposed DiffusionPID method to analyze the semantic similarity between synonym pairs: ‘bed’ and ‘mattress’, and ‘cube’ and ‘cuboid’. The redundancy map, a key output of DiffusionPID, highlights the regions in the generated images where the model associates both words strongly. For ‘bed’ and ‘mattress’, the redundancy is concentrated on the bed region, indicating the model’s understanding of their semantic overlap. Similarly, for ‘cube’ and ‘cuboid’, the redundancy map strongly activates around the cuboid, highlighting the shared semantic space. The visualization is compared against mutual information (MI), conditional mutual information (CMI), and Discriminator Attention Maps (DAAM) methods. The figure demonstrates the superior performance of DiffusionPID’s redundancy map in precisely highlighting the semantically similar regions compared to the other methods.

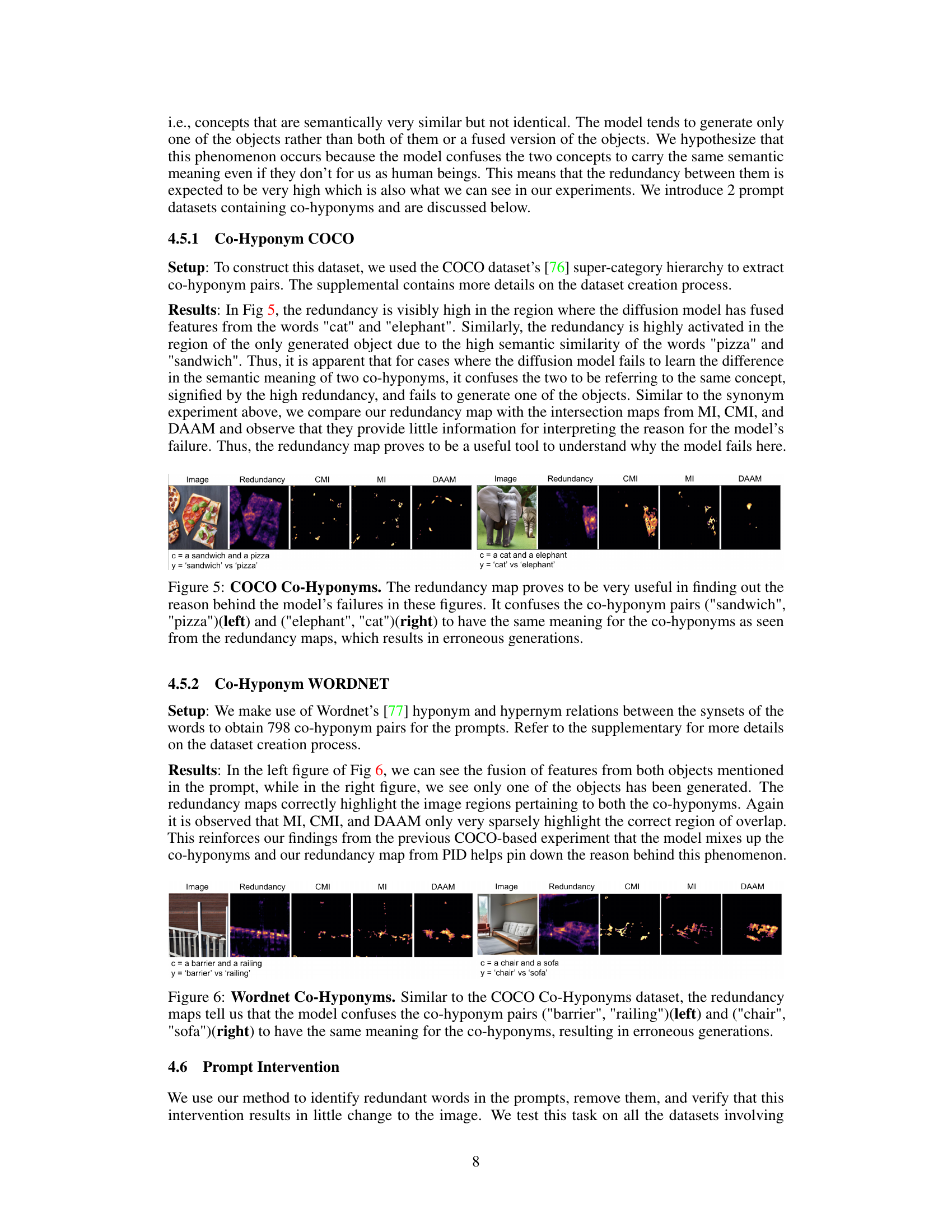

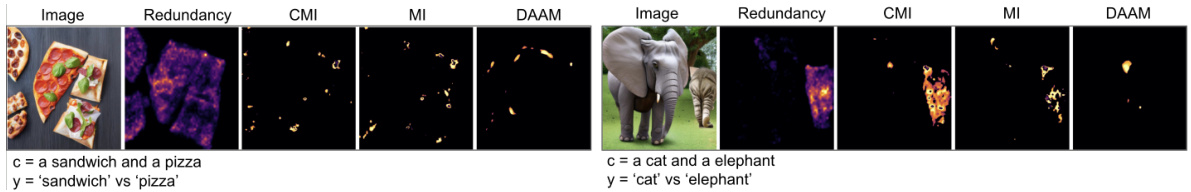

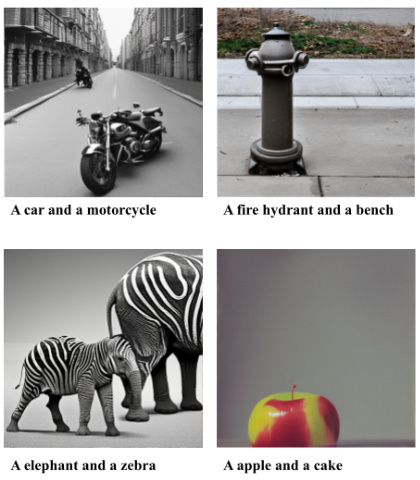

This figure shows the results of applying the DiffusionPID method to analyze the redundancy between co-hyponym pairs from the COCO dataset. The left image shows a generated image of both a sandwich and a pizza. This indicates that the model fails to distinguish between the two and treat them as redundant rather than distinct concepts. The right shows a similar situation with a generated image of both an elephant and a cat, despite them being co-hyponyms. The redundancy maps highlight the regions of the image where the model conflates the meanings of the two words. This supports the hypothesis that the model struggles with co-hyponyms due to associating them with the same semantic meaning.

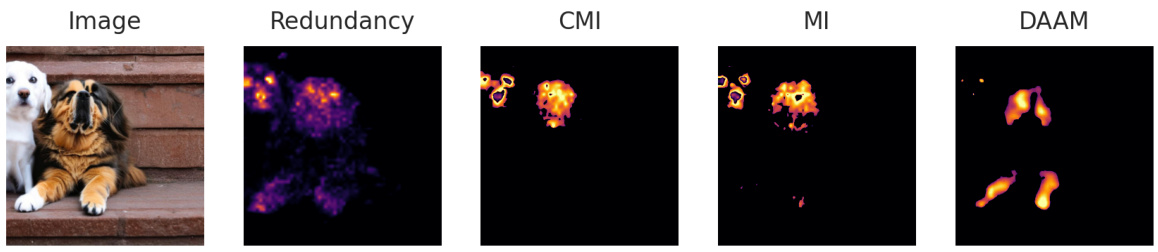

This figure shows the redundancy maps produced by the DiffusionPID method for two pairs of co-hyponyms (words with similar meanings but not identical) from the Wordnet dataset. The left panel shows the results for the pair ‘barrier’ and ‘railing’, while the right panel shows the results for the pair ‘chair’ and ‘sofa’. The redundancy maps highlight the regions where the model confuses the two co-hyponyms, resulting in images that fuse features from both objects or generate only one of the objects. This confusion is because the model does not adequately differentiate between the co-hyponyms’ semantic meaning, treating them as if they were synonyms.

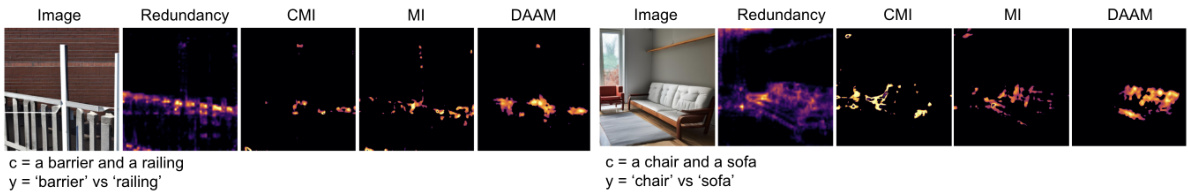

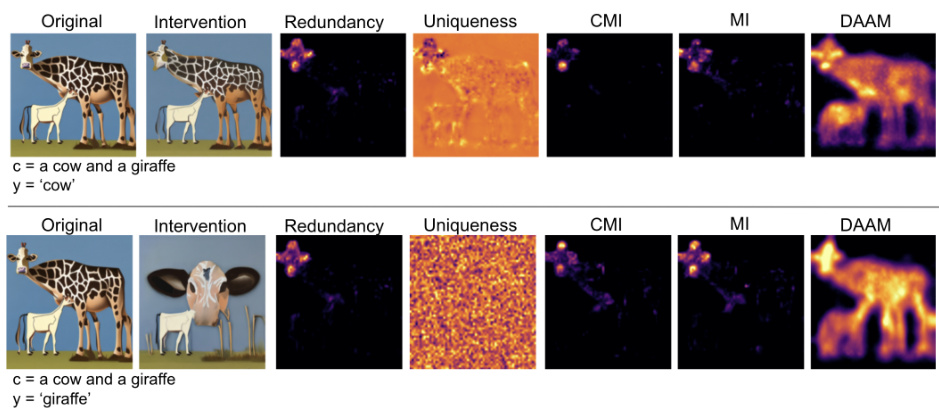

This figure shows the results of a prompt intervention experiment. The top row shows the original image generated with the prompt ‘a cow and a giraffe’, along with the generated image after removing the word ‘cow’ from the prompt, and several information maps (redundancy, uniqueness, CMI, MI, DAAM). The bottom row shows the same analysis but removing the word ‘giraffe’ instead. The results demonstrate that removing the word ‘cow’ (redundant word) has minimal effect on the generated image, because its information is already captured by the presence of the word ‘giraffe’. This experiment highlights the effectiveness of DiffusionPID in identifying and removing redundant words in prompts, which allows for more concise prompts with minimal impact on the generated image.

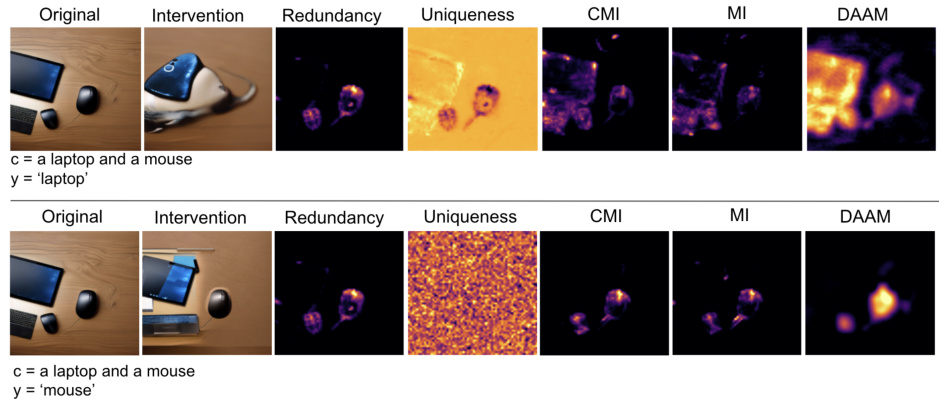

This figure shows the result of prompt intervention experiments. By removing the word ‘mouse’ from the prompt, the generated image remains almost the same. The redundancy map highlights the mouse area, indicating that the word ‘mouse’ is redundant in the prompt. The uniqueness map for the mouse is low and spread out, further supporting this. This experiment validates that removing redundant words from prompts has minimal impact on the generated image.

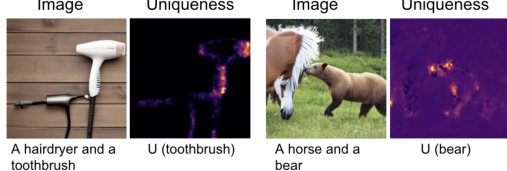

This figure visualizes the uniqueness maps generated by the DiffusionPID method for two different prompts: ‘A hairdryer and a toothbrush’ and ‘A horse and a bear’. The uniqueness map highlights the regions of the image that are most uniquely associated with a specific concept in the prompt. In the left panel, the uniqueness map for ’toothbrush’ strongly emphasizes the bristles, showing that these are the most distinctive characteristics of the toothbrush as perceived by the model. Similarly, in the right panel, the uniqueness map for ‘bear’ focuses on the bear’s face, indicating the model’s recognition of the facial features as the key identifier for the bear.

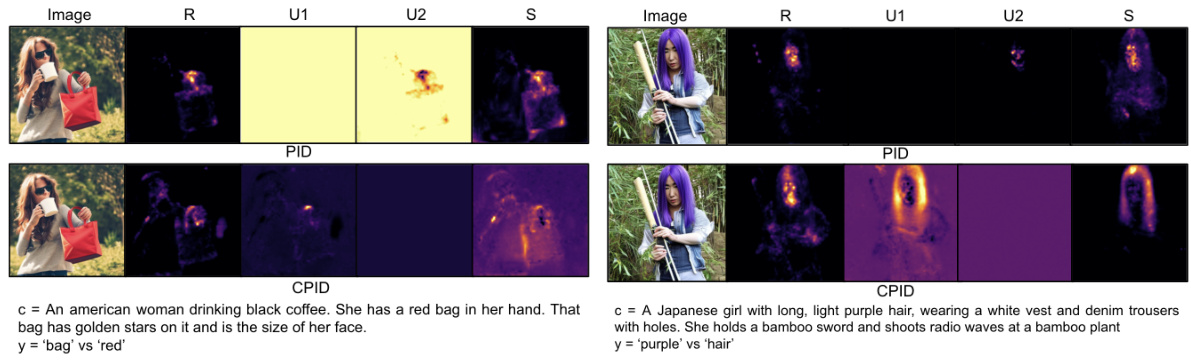

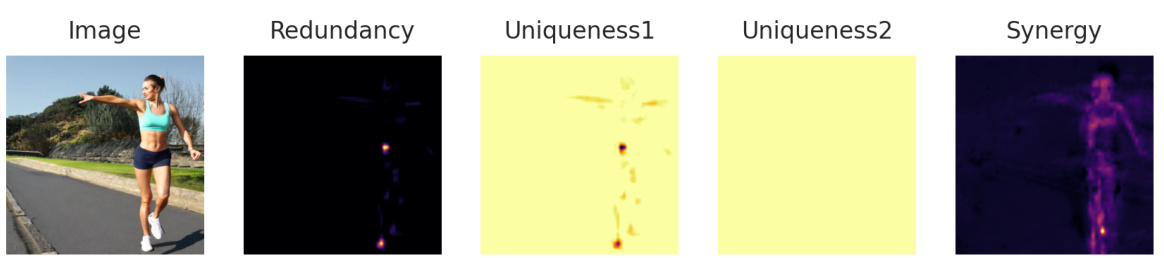

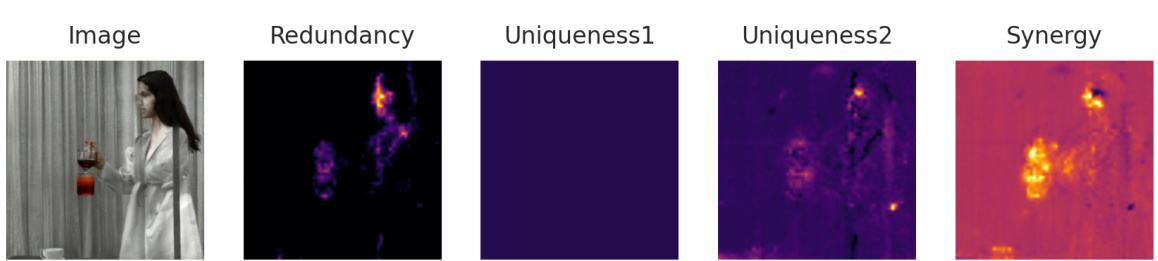

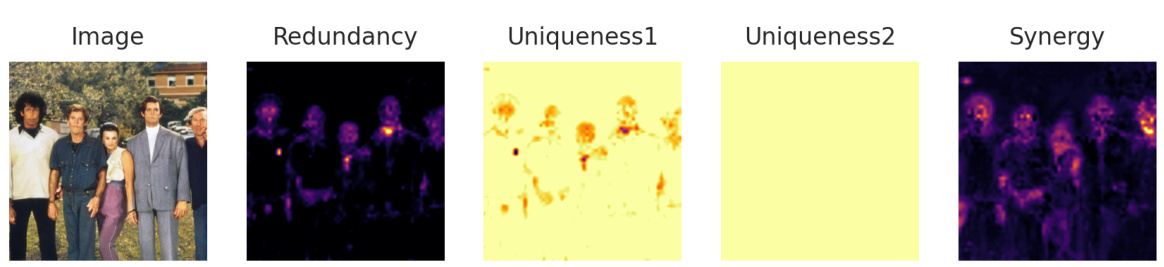

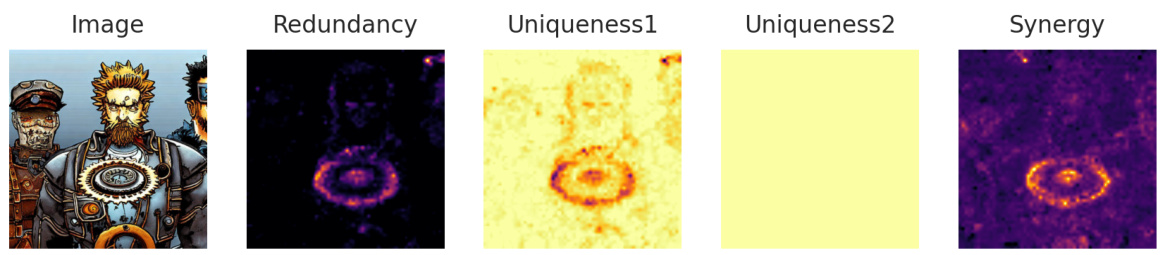

This figure shows the results of applying Partial Information Decomposition (PID) and Conditional PID (CPID) to complex prompts. The prompts describe scenes with multiple objects and attributes, such as ‘An American woman drinking black coffee. She has a red bag in her hand. That bag has golden stars on it and is the size of her face.’ and ‘A Japanese girl with long, light purple hair, wearing a white vest and denim trousers with holes. She holds a bamboo sword and shoots radio waves at a bamboo plant.’. The figure displays the image, redundancy (R), uniqueness for the first word (U1), uniqueness for the second word (U2), and synergy (S) for both PID and CPID analyses. This visualization helps understand how individual words and their interactions contribute to the generated image by the diffusion model. The difference in results between PID and CPID highlights the impact of context on the model’s interpretation.

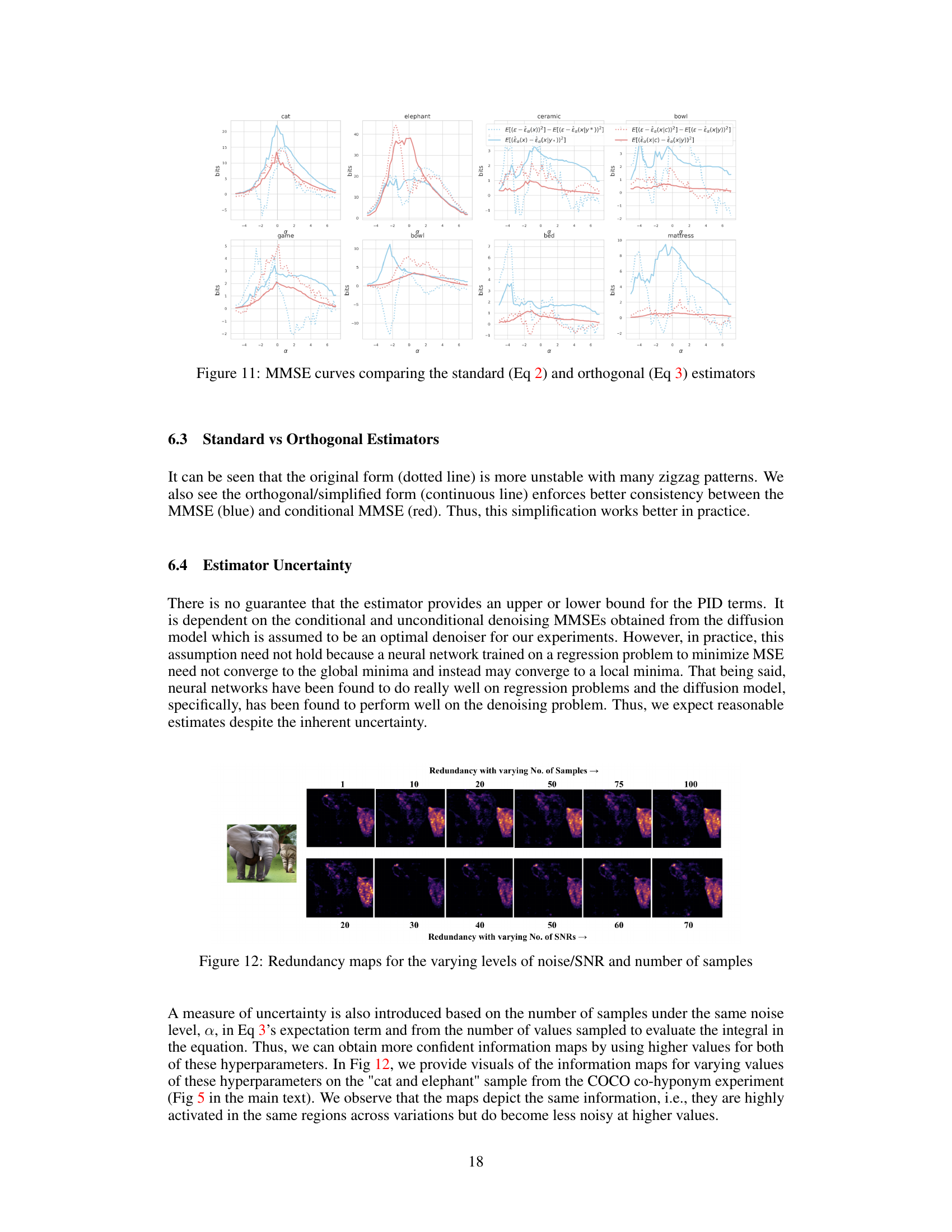

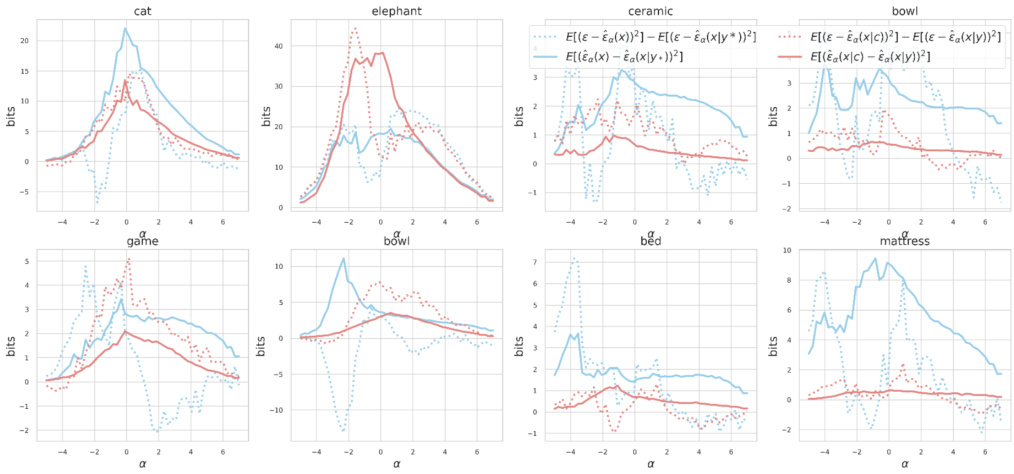

This figure presents a comparison of MMSE curves obtained using two different estimators for mutual information: the standard estimator (Equation 2) and the orthogonal estimator (Equation 3). The x-axis represents the noise level (α), while the y-axis represents the value of the MMSE (Mean Squared Error). The figure shows that the orthogonal estimator provides more stable and consistent results compared to the standard estimator, which exhibits significant zigzag patterns, particularly at lower noise levels. This comparison highlights the advantage of using the simplified orthogonal estimator for practical applications. The comparison is shown for several words from the dataset: cat, elephant, ceramic, bowl, game, bowl, bed, and mattress.

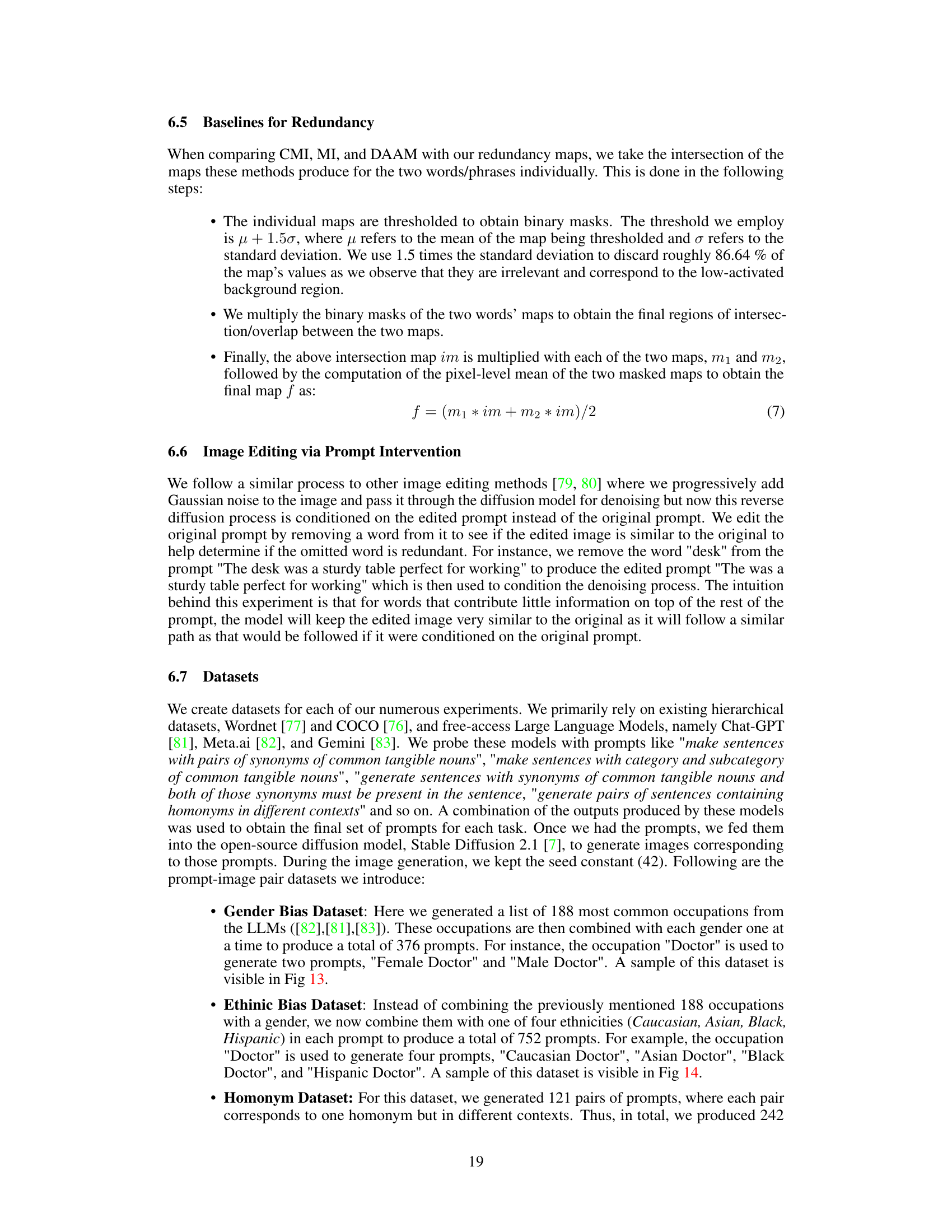

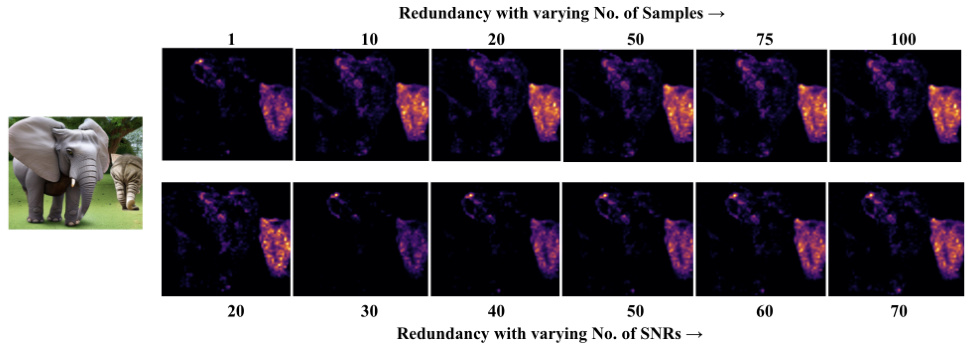

This figure displays redundancy maps generated at different noise levels (SNR) and with varying numbers of samples. The maps illustrate how the redundancy estimations change as more samples and varying SNRs are incorporated into the calculation. This helps to understand the uncertainty and stability of the redundancy measure.

This figure demonstrates the DiffusionPID method’s ability to analyze text-to-image diffusion models. The left panel shows how the model identifies visual similarities (uniqueness) between a tennis ball and baseball, highlighting the seam region as a shared feature. The center panel illustrates how the model uses contextual cues (synergy) to generate images, showing a strong relationship between ‘bat,’ ‘baseball,’ and ‘overhead.’ The right panel showcases how the model identifies redundancy between ‘queen’ and ‘crown,’ correctly focusing on the crown and facial area.

This figure demonstrates the DiffusionPID method’s ability to analyze the contribution of individual words and their interactions in generating images from text prompts. The left panel shows how the model associates visual similarities (seam of tennis ball and baseball), the middle panel displays how the model uses contextual information (bat, baseball, overhead) for appropriate image generation, and the right panel illustrates the redundancy between related concepts (queen, crown).

This figure demonstrates the DiffusionPID method’s ability to analyze text-to-image diffusion models. The left panel shows a uniqueness map highlighting the visual similarity between a tennis ball and a baseball, indicating that the model uses shared visual features. The center panel demonstrates synergy, showing how the model leverages contextual cues (‘bat,’ ‘baseball,’ ‘overhead’) to generate appropriate imagery. The right panel showcases redundancy, with the model appropriately focusing on the crown and facial region when provided the prompt words ‘queen’ and ‘crown.’

This figure demonstrates the DiffusionPID method’s ability to interpret text prompts in image generation. The left panel shows a uniqueness map for the word ‘baseball,’ highlighting the similarity between a baseball and a tennis ball. The center panel illustrates synergy between ‘bat,’ ‘baseball,’ and ‘overhead,’ indicating how contextual cues influence image generation. The right panel shows a redundancy map for ‘queen’ and ‘crown,’ accurately focusing on the relevant image regions.

This figure demonstrates the DiffusionPID method’s ability to highlight specific visual-semantic relationships within generated images. The left panel shows how the model recognizes visual similarity (uniqueness) between a baseball and a tennis ball, focusing on their seam. The center panel illustrates how contextual cues, such as the words ‘bat,’ ‘baseball,’ and ‘overhead,’ synergistically contribute to the generation of a coherent scene. Finally, the right panel showcases the redundancy detected by the model between the words ‘queen’ and ‘crown,’ correctly highlighting the relevant image regions.

This figure demonstrates the DiffusionPID method’s ability to analyze the information contribution of different text tokens in generating images from text prompts using three examples. The left panel shows a uniqueness map for the word ‘baseball,’ highlighting the tennis ball’s seam, which is visually similar to a baseball. This indicates that the model identifies this visual feature as unique to the concept of a baseball. The center panel illustrates a synergy map between the words ‘bat,’ ‘baseball,’ and ‘overhead,’ demonstrating the model’s use of contextual cues to correctly generate a bat in the appropriate setting. The right panel displays a redundancy map for ‘queen’ and ‘crown,’ correctly focusing on the overlapping visual aspects of the crown and the queen’s face.

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the DiffusionPID method in identifying unique, redundant, and synergistic information within text prompts used for image generation. The left panel shows the uniqueness of the word ‘baseball’, highlighting similarities between a baseball and a tennis ball. The center panel illustrates synergy between ‘bat’, ‘baseball’, and ‘overhead’, showcasing how these words work together to generate a coherent image. The right panel shows the redundancy between ‘queen’ and ‘crown’, accurately highlighting the overlapping visual features.

This figure shows two examples of how diffusion models handle homonyms, which are words with multiple meanings. The left side demonstrates a successful generation where the model uses contextual cues to select the appropriate meaning of the homonym ‘bowl’ (a container or a stadium). The synergy map shows high synergy between ‘bowl’ and the modifiers ‘ceramic’ and ‘game,’ indicating that the model leveraged these contextual cues effectively. The right side shows a failure case, where the model fails to differentiate between the meanings of the homonym ‘mole’ (a spy or a small animal), generating the animal instead of the intended meaning of a spy. The synergy map shows low synergy between ‘mole’ and the contextual cues ‘coworker’ and ‘searching,’ explaining the model’s failure to utilize the contextual information.

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the DiffusionPID method in identifying visual-semantic relationships in images generated by text-to-image diffusion models. The three subfigures illustrate the three core concepts of the PID framework: Uniqueness, Synergy, and Redundancy. The left panel shows that the model identifies similar visual features (the seams of a baseball and tennis ball) as unique aspects of the ‘baseball’ prompt. The center panel highlights the synergistic relationship between prompts (‘bat’, ‘baseball’, ‘overhead’), demonstrating the model’s ability to combine contextual cues to generate coherent scenes. Finally, the right panel illustrates redundancy between the prompts (‘queen’ and ‘crown’), showing how the model focuses on overlapping regions (the crown and queen’s face) in the generated image. This visual representation highlights the capacity of DiffusionPID to unpack the complex interplay between textual prompts and image generation.

This figure shows the results of applying both Partial Information Decomposition (PID) and Conditional PID (CPID) to analyze complex image generation prompts. Two examples are provided, demonstrating how the methods decompose the prompt into uniqueness, redundancy, and synergy components and highlighting the differences between PID and CPID in capturing contextual information.

This figure demonstrates the DiffusionPID method’s ability to highlight specific visual-semantic relationships within generated images. The left panel shows the uniqueness of the word ‘baseball,’ emphasizing a tennis ball’s seam, which is similar to a baseball. The center panel shows the synergy between ‘bat,’ ‘baseball,’ and ‘overhead,’ illustrating how contextual cues influence generation. The right panel showcases the redundancy of ‘queen’ and ‘crown,’ focusing on overlapping features.

This figure demonstrates the DiffusionPID method’s ability to analyze the uniqueness, synergy, and redundancy of different words in a text prompt. The left panel shows the uniqueness map for ‘baseball,’ highlighting similar features between a baseball and a tennis ball. The center panel illustrates the synergy between ‘bat,’ ‘baseball,’ and ‘overhead,’ showcasing the model’s contextual understanding. Finally, the right panel depicts the redundancy map between ‘queen’ and ‘crown,’ accurately identifying overlapping semantic information.

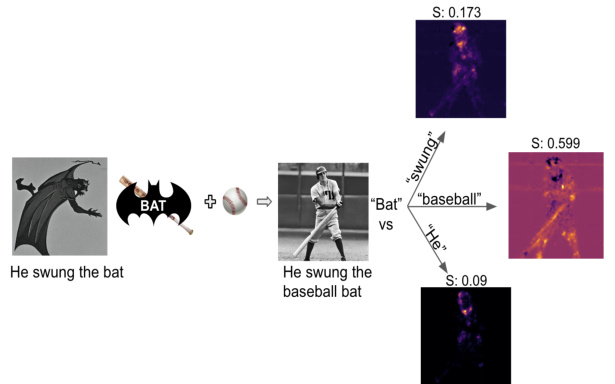

This figure shows how the model uses context to disambiguate homonyms. In the first example, the word ‘bat’ is successfully identified as a baseball bat because of the synergistic context provided by the words ‘baseball’ and ‘swing’. However, in the second example, without sufficient context, the model fails to correctly interpret the meaning of ‘bat’, leading to an incorrect generation.

This figure shows two examples of the model’s performance when dealing with homonyms (words with multiple meanings). The left shows that with the proper contextual modifiers, the model generates the correct image, while the right side shows failure where despite proper modifiers, the model fails to generate the correct image and maintains the default meaning of the homonym.

This figure shows the synergy maps for two homonyms, ‘bowl’ and ‘mole’, used in different contexts. The left panel shows that the model successfully generates the correct image for the ‘bowl’ homonym, indicating the ability to utilize context. The right panel demonstrates the model’s failure with the ‘mole’ homonym, showing the inability to use contextual information to correctly generate the image. This highlights how the model sometimes fails to capture the nuances of meaning in context.

This figure demonstrates the application of the DiffusionPID method to analyze how diffusion models handle homonyms (words with multiple meanings) in different contexts. The left panel shows a successful case where the model correctly generates different visuals for the homonym ‘bowl’ based on the provided context (‘ceramic bowl’ vs. ‘rose bowl stadium’), evidenced by the high synergy between the homonym and the modifiers. The right panel, however, illustrates a failure case. Despite providing context (‘coworker’ and ‘searching’), the model fails to correctly disambiguate the homonym ‘mole’, generating an image of an animal instead of a person who might be secretly leaking information. This failure is highlighted by the low synergy scores observed in the corresponding synergy map. The results show that the synergistic relationship between the homonym and the modifiers is critical for the correct interpretation of homonyms.

This figure shows the results of applying both Partial Information Decomposition (PID) and Conditional PID (CPID) to complex prompts. The two example prompts are shown above the images, illustrating how the methods decompose the semantic information within the prompts in order to provide insight into how the diffusion model processes them. Each sub-figure shows the image generated from the prompt, along with the Redundancy, Uniqueness for each term in the prompt, and Synergy maps from both the PID and CPID methods. This allows for a comparison of the two methods for analyzing the information contribution of the different elements within the prompts to the final image. By comparing the visualizations from PID and CPID, it’s possible to understand the difference that the context of the rest of the prompt makes on the individual terms within the prompt.

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the DiffusionPID method in interpreting text-to-image diffusion models by visualizing uniqueness, synergy, and redundancy between different words in a prompt. The left image shows how the model recognizes the visual similarity between a baseball and a tennis ball, highlighting the seam region as unique to ‘baseball’. The center image illustrates the synergistic relationship between ‘bat’, ‘baseball’, and ‘overhead’, demonstrating how the model utilizes these contextual cues. The right image shows redundancy between ‘queen’ and ‘crown’, focusing on the crown and facial region as overlapping concepts.

This figure shows the results of applying the DiffusionPID method to analyze the semantic similarity of synonym pairs. The redundancy maps, generated by DiffusionPID, highlight the regions in the generated images that are semantically related to both synonyms. For example, in the left image the redundancy map highlights the bed region for both the words ‘bed’ and ‘mattress’, indicating a high degree of semantic overlap. This suggests that the model correctly identifies the semantic similarity between the synonym pairs.

This figure visualizes redundancy maps generated using different numbers of samples and signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs). It aims to demonstrate the impact of these parameters on the accuracy and consistency of the redundancy maps, highlighting the trade-off between computational cost and the precision of the results. The consistency of highlighted regions across varying parameters suggests robustness of the method.

This figure shows the results of applying Partial Information Decomposition (PID) and Conditional PID (CPID) to complex prompts containing multiple objects and their attributes. The image shows that CPID provides slightly better localized results than PID, likely due to its consideration of the contextual contribution of the rest of the prompt in the image generation process.

This figure shows three examples of how the DiffusionPID method highlights different aspects of visual-semantic relationships learned by diffusion models. The left panel illustrates the uniqueness of the word ‘baseball’ by focusing on the seam of a tennis ball, which visually resembles a baseball. The center panel demonstrates the synergy between words like ‘bat,’ ‘baseball,’ and ‘overhead,’ showing how the model uses contextual clues to generate appropriate images. The right panel showcases the redundancy between ‘queen’ and ‘crown,’ correctly identifying the overlapping visual features.

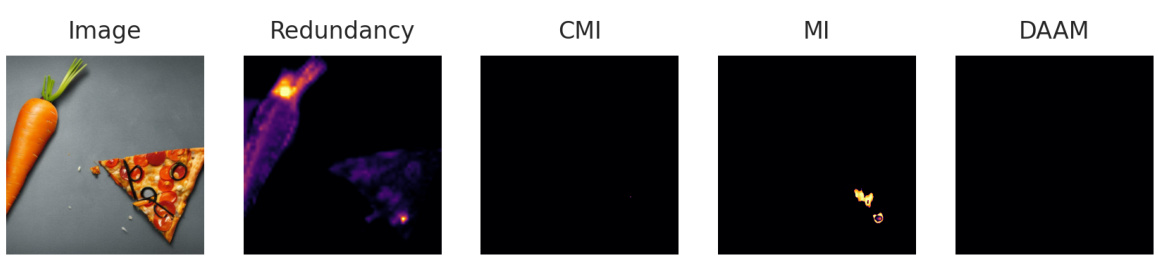

This figure shows the results of applying the DiffusionPID method to analyze the generation of images from prompts containing co-hyponyms (words with similar meanings) from the COCO dataset. The left panel shows a prompt with ‘sandwich’ and ‘pizza’, and the right panel shows a prompt with ’elephant’ and ‘cat’. In both cases, the redundancy map (a visualization of the redundancy term in PID) highlights that the model treats the co-hyponyms as highly similar. This similarity leads to the model’s failure to generate both objects in the image, instead generating a fused version or just one of the objects. This finding indicates that the model may have difficulties distinguishing between closely related concepts, highlighting a limitation in its ability to handle subtle semantic differences.

This figure visualizes redundancy maps generated using different numbers of samples and signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs). It demonstrates how the quality of the redundancy maps improves with increasing sample size and higher SNRs, suggesting better reliability of the method with improved data quality.

This figure shows the results of applying both PID and CPID to complex prompts. Two example prompts are used, each with associated images and heatmaps illustrating redundancy, uniqueness (for two terms in each prompt), and synergy. The heatmaps visually represent the information theoretic concepts calculated by PID and CPID at the pixel level, showcasing how different parts of the prompt contribute to the final image generation. CPID, an extension of PID that accounts for context, is compared to standard PID to demonstrate its potential advantages in interpreting complex prompts.

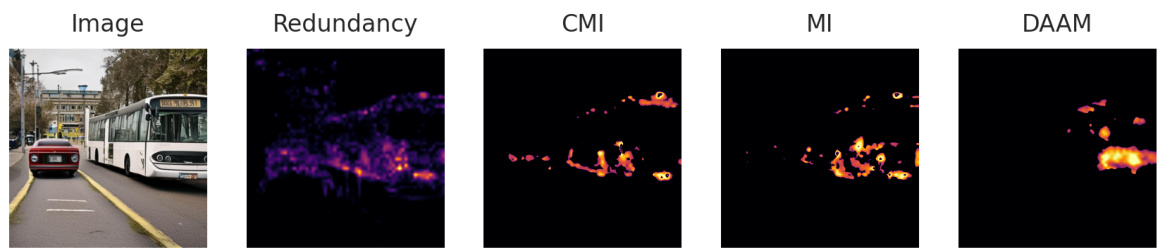

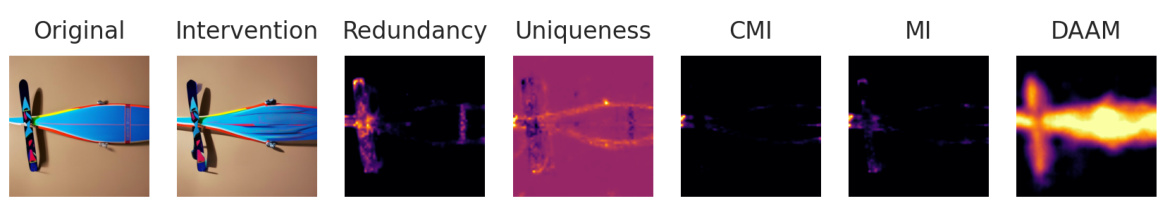

This figure shows the results of applying the proposed method, DiffusionPID, to analyze co-hyponyms from the Wordnet dataset. Co-hyponyms are words with similar but not identical meanings. The redundancy maps highlight regions where the model conflates the meanings of the co-hyponyms, leading to errors in the generated images. The figure compares the redundancy map produced by DiffusionPID with maps produced by other methods (CMI, MI, and DAAM) which don’t show as much relevant information.

This figure shows a comparison of redundancy maps generated using the proposed DiffusionPID method and three other methods (CMI, MI, and DAAM) for two sets of co-hyponyms from WordNet: (‘barrier’, ‘railing’) and (‘chair’, ‘sofa’). The redundancy maps highlight regions where the model confuses the two concepts in each pair, indicating that the model does not fully differentiate them semantically. The other methods show far less localized results, suggesting that DiffusionPID is better suited to capture this type of semantic confusion.

This figure demonstrates the use of uniqueness maps generated by the DiffusionPID method to highlight the most representative features of objects from the model’s perspective. The left panel shows a generated image of a hairdryer and a toothbrush, with the uniqueness map focusing strongly on the bristles of the toothbrush, indicating that the model considers the bristles to be the most distinctive characteristic. The right panel shows a generated image of a horse and a bear, with the uniqueness map clearly highlighting the bear’s face as its most defining feature. This illustrates how DiffusionPID can help identify uniquely defining characteristics of objects, separating them from potentially redundant visual information.

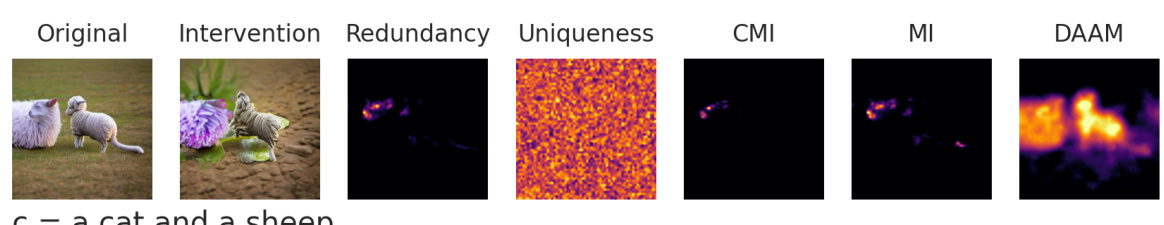

This figure shows an example of prompt intervention using the DiffusionPID method. The original prompt was ‘a cat and a sheep’. The image generated by Stable Diffusion shows a sheep whose face appears to be that of a cow. The redundancy map highlights the face region, indicating redundancy between ‘cow’ and ‘sheep’. After removing the word ‘cow’ from the prompt (intervention), the generated image is almost identical, confirming that ‘cow’ is a redundant word in this context. The uniqueness, CMI, MI, and DAAM maps are also shown for comparison.

This figure shows an example of prompt intervention. The original prompt was ‘a cat and a sheep.’ The image generated shows a sheep with a cat’s face. The redundancy map highlights the cat’s facial features, suggesting that ‘cat’ is redundant to the model’s generation process. An intervention was performed by removing the word ‘cat’ from the prompt resulting in a much more accurate image of only a sheep. This demonstrates how PID can highlight redundancy and help correct model outputs via prompt engineering.

This figure shows the results of a prompt intervention experiment. The original prompt included the objects ’laptop’ and ‘mouse’. The researchers removed the word ‘mouse’ from the prompt and generated a new image. The redundancy map (showing shared information between the two concepts) shows high activation in the mouse region indicating that the information about the mouse is redundant with the laptop in this case. The uniqueness map (showing unique information for each concept) shows low activation for ‘mouse’, confirming that the mouse is not a unique element for the model. The overall visual similarity between the original and the intervention images supports that removing the word ‘mouse’ had little effect on the image generated by the model, thus confirming its redundancy.

This figure shows an example of prompt intervention using the DiffusionPID method. The original prompt contained the phrase ‘a cow and a giraffe.’ The redundancy map highlights a significant overlap between the cow and giraffe features, particularly focusing on the giraffe’s face, which is actually a cow’s face. When the word ‘cow’ was removed from the prompt, the generated image showed little change. This demonstrates that ‘cow’ is a redundant element in this specific context because the model already uses its features to represent the giraffe (the cow’s face features being mistaken for a giraffe’s features).

This figure shows an example of prompt intervention. The original image contains a cow and a giraffe. The word ‘cow’ is identified as redundant based on the redundancy map (which is highly activated in the giraffe’s face, showing cow-like features). Removing ‘cow’ from the prompt results in only a minor change to the generated image, confirming the redundancy of this word.

This figure shows an example of prompt intervention using the DiffusionPID method. The original prompt includes the words ‘cow’ and ‘giraffe’. The redundancy map highlights the face region of the generated giraffe image, indicating that the model considers the ‘cow’ aspect to be redundant in this context. The intervention removes the word ‘cow’ from the prompt, resulting in only a slight change in the generated image, confirming that ‘cow’ was redundant to the model.

This figure shows an example of prompt intervention using the DiffusionPID method. The original image contains a cow and a giraffe. The redundancy map highlights the face of the giraffe, which visually resembles a cow. When the word ‘cow’ is removed from the prompt, the generated image remains largely unchanged, confirming the redundancy of the term ‘cow’. This demonstrates that DiffusionPID can identify and remove redundant words in prompts, leading to minimal changes in the generated images. The other maps (Uniqueness, CMI, MI, DAAM) are provided for comparison and illustrate that DiffusionPID provides more targeted insights into the impact of specific words on the image generation process.

This figure shows an example of prompt intervention using the DiffusionPID method. The original prompt included the words ‘cow’ and ‘giraffe’. The resulting image shows a giraffe whose face resembles a cow, indicating that the word ‘cow’ was redundant in the prompt. When the word ‘cow’ is removed from the prompt, the generated image is nearly identical to the original, confirming the redundancy analysis. The figure also displays the redundancy, uniqueness, CMI, MI, and DAAM maps which support this observation.

Full paper#