TL;DR#

Implicit Neural Representations (INRs) are powerful but struggle with transferability; they’re highly tuned to the specific signal they’re trained on, limiting their use for similar signals. This paper addresses this issue by exploring the transferability of learned INR features. Existing methods are limited by computational expense and often require considerable amounts of data for training.

The paper introduces STRAINER, a new INR training method. STRAINER shares the initial encoder layers across multiple INRs, learning transferable features and uses them to initialize new INRs at test time. Experiments show that STRAINER leads to significantly faster convergence and higher reconstruction quality. The method efficiently encodes data-driven priors into INRs. Its success on both in-domain and out-of-domain tasks showcases the wide applicability and transferability of the learned features.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it introduces STRAINER, a novel framework that improves the transferability of features in Implicit Neural Representations (INRs). This addresses a key limitation of INRs, enabling faster and higher-quality fitting of new signals. The findings are relevant to various applications using INRs, opening avenues for research in efficient INR training and transfer learning across diverse domains, particularly beneficial for resource-constrained applications.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the STRAINER framework for learning transferable features in Implicit Neural Representations (INRs). Panel (a) shows the training phase where multiple INRs are trained simultaneously, sharing the encoder layers but having independent decoder layers. This shared encoder learns generalizable features from a set of similar input signals. Panel (b) demonstrates the test phase where the learned encoder from training is used to initialize a new INR for a previously unseen signal, significantly improving performance. Panel (c) presents a qualitative comparison of reconstruction results, showcasing that INRs initialized using STRAINER achieve faster convergence and superior quality compared to a standard SIREN model.

read the caption

Figure 1: STRAINER - Learning Transferable Features for Implicit Neural Representations. During training time (a), STRAINER divides an INR into encoder and decoder layers. STRAINER fits similar signals while sharing the encoder layers, capturing a rich set of transferrable features. At test-time, STRAINER serves as powerful initialization for fitting a new signal (b). An INR initialized with STRAINER's learned encoder features achieves (c) faster convergence and better quality reconstruction compared to baseline SIREN models.

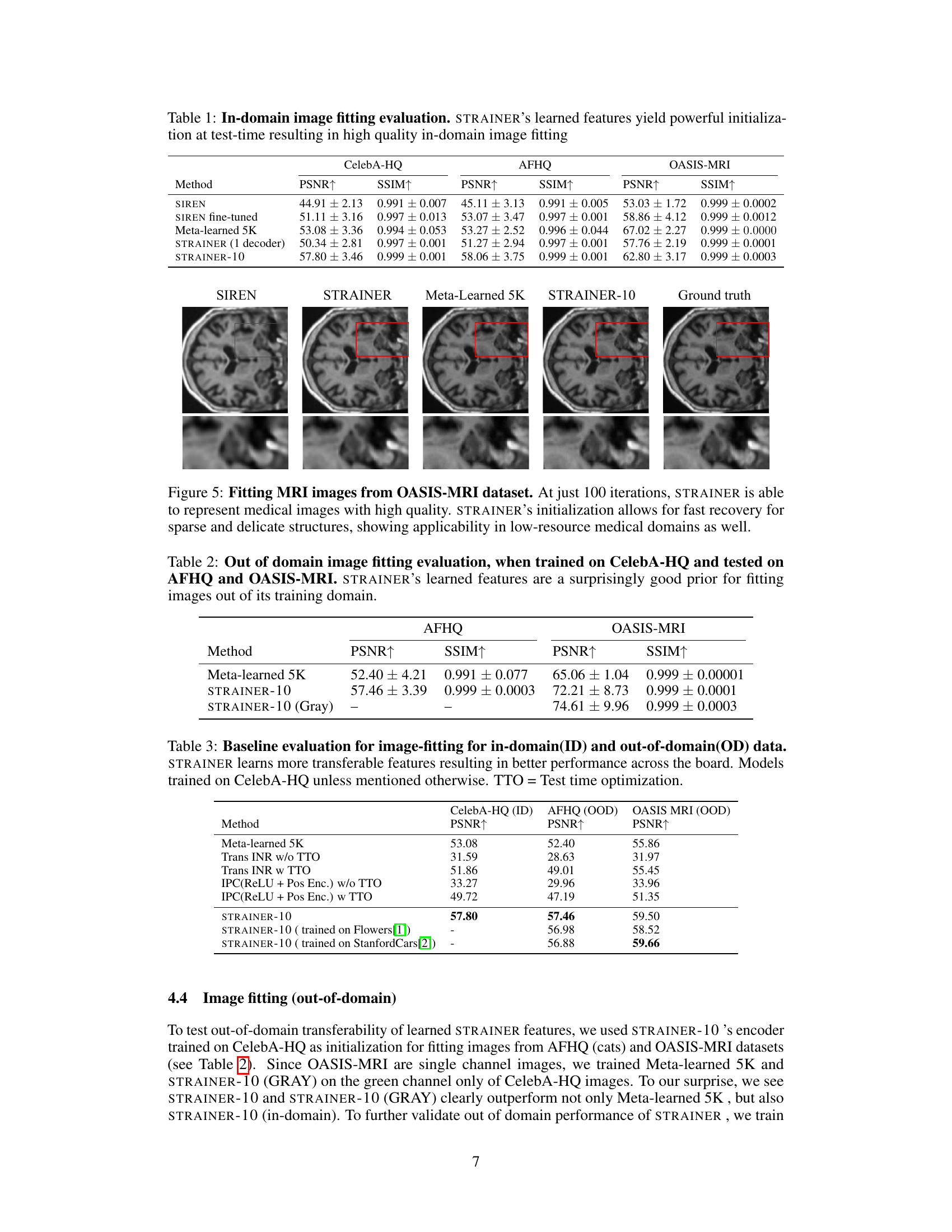

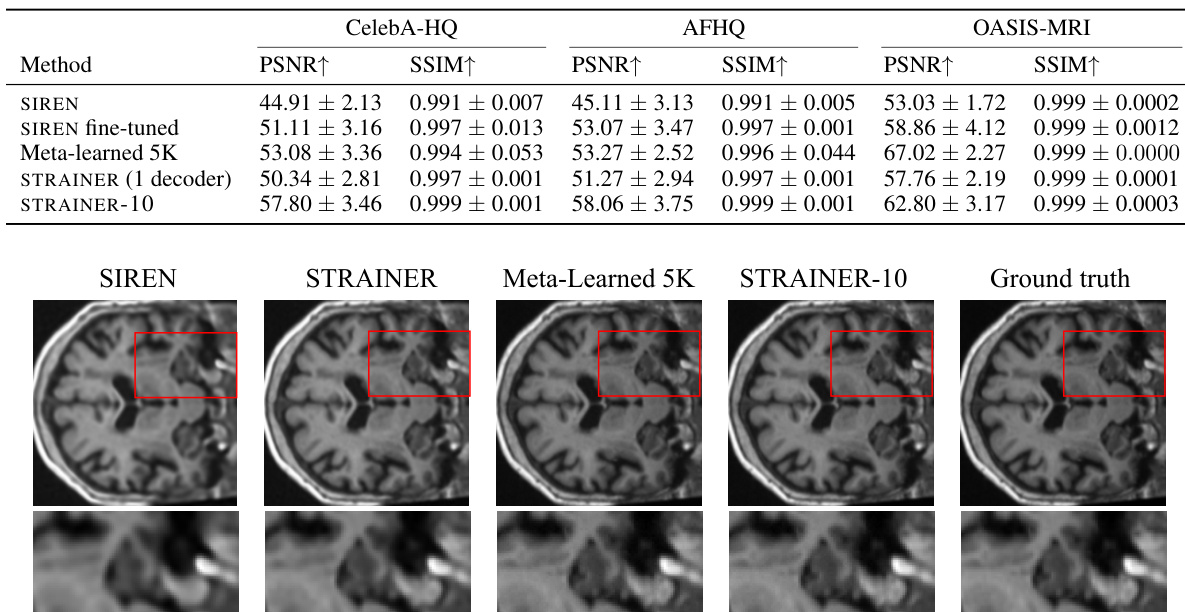

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of in-domain image fitting experiments. Several methods, including SIREN (baseline), SIREN fine-tuned, Meta-learned 5K, STRAINER (1 decoder), and STRAINER-10, are compared across three datasets: CelebA-HQ, AFHQ, and OASIS-MRI. The metrics used for evaluation are Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM). Higher PSNR and SSIM values indicate better image quality. The results demonstrate that STRAINER, particularly STRAINER-10, achieves superior performance compared to other methods, showcasing the effectiveness of its learned transferable features for fast and high-quality image reconstruction.

read the caption

Table 1: In-domain image fitting evaluation. STRAINER's learned features yield powerful initialization at test-time resulting in high quality in-domain image fitting

In-depth insights#

INR Transferability#

The concept of “INR Transferability” explores the extent to which features learned by an Implicit Neural Representation (INR) for a specific signal can be transferred and reused effectively for fitting similar, yet unseen signals. A key challenge is that INRs are typically trained individually for each signal, leading to features highly specialized to that signal and not easily generalizable. The paper introduces a novel framework, STRAINER, to address this by sharing initial encoder layers across multiple INRs trained on similar signals, thus learning transferable features. This shared encoder, once trained, is then used to initialize new INRs, leading to significant improvements in fitting speed and reconstruction quality, demonstrating the potential of transfer learning in INRs. The results suggest that lower-level features in INRs are more transferable than higher-level features, indicating a potential hierarchical structure to feature learning. The effectiveness of STRAINER on in-domain and out-of-domain tasks showcases the significant value of learned, transferable features for improving both the speed and quality of INR fitting. Further research could explore the precise nature of these transferable features and optimize the architecture of STRAINER for maximum transferability and generalization.

STRAINER Framework#

The STRAINER framework introduces a novel approach to training Implicit Neural Representations (INRs) by focusing on transferability. It cleverly separates the INR into encoder and decoder layers, training multiple INRs simultaneously while sharing encoder weights across similar signals. This shared encoder learns generalizable features, capturing common underlying structures. At test time, this pre-trained encoder acts as a powerful initialization for fitting new signals, significantly accelerating convergence and improving reconstruction quality compared to training INRs from scratch. STRAINER’s success highlights the potential of leveraging shared representations within INRs to achieve greater efficiency and generalization, especially valuable in resource-constrained settings or when dealing with limited data. The framework’s modularity allows for easy integration of data-driven priors, furthering its flexibility and impact.

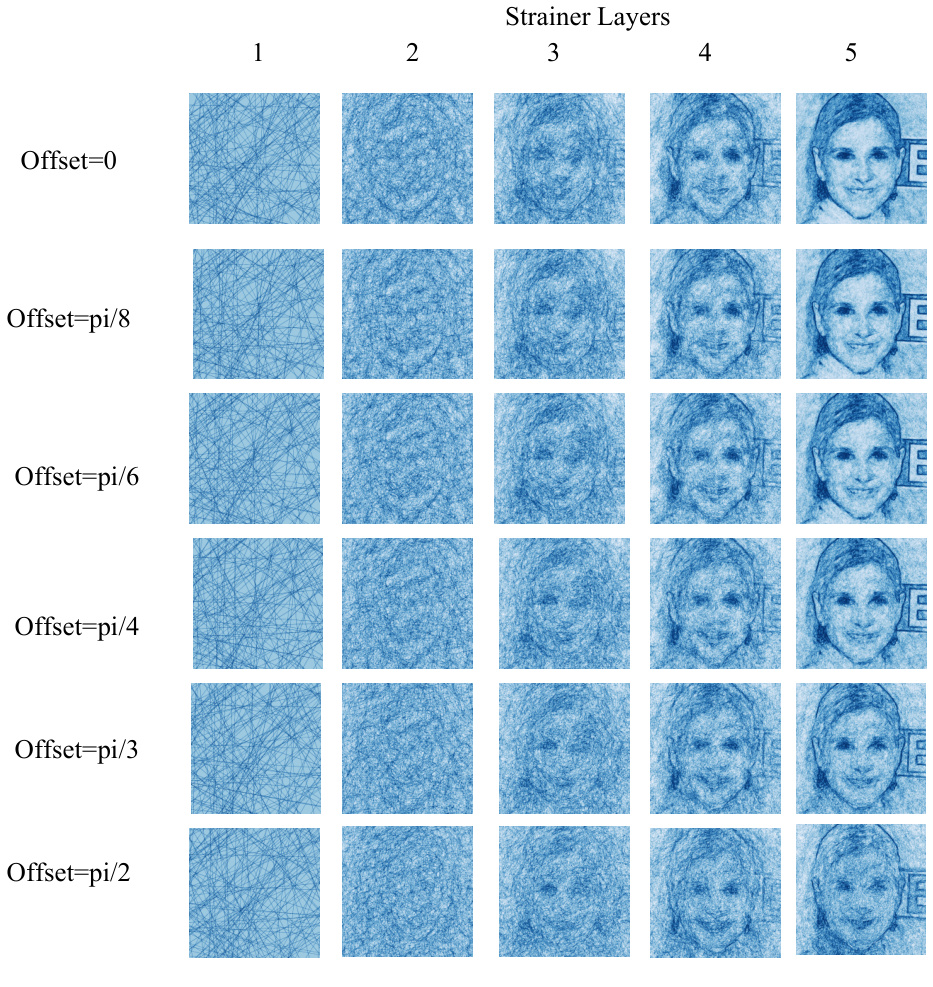

Feature Visualization#

Feature visualization in implicit neural representations (INRs) is crucial for understanding their internal workings and the nature of learned features. The paper likely explores techniques to visualize the features learned by the encoder layers of STRAINER, possibly using dimensionality reduction methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to project high-dimensional feature vectors into lower dimensions for easier interpretation. The visualization might reveal how the shared encoder layers learn transferable representations capturing common characteristics across multiple images. It would be insightful to see how these representations compare to features learned by individually trained INRs or other architectures like CNNs. The analysis should reveal whether the shared encoder learns a more general, abstract representation or a specific set of features finely tuned to the training data’s specifics. Furthermore, comparing the feature visualizations across different iterations of training would illuminate how the representations evolve and refine over time. The visualization may demonstrate the model’s ability to learn low-frequency features early on and then progressively capturing higher-frequency details. The contrast between STRAINER’s visualizations and the baselines would solidify the claims regarding faster convergence and improved reconstruction quality. Ideally, the paper presents a compelling narrative supported by clear and insightful visualizations.

Inverse Problem#

The research paper explores the application of Implicit Neural Representations (INRs) to inverse problems. INRs’ ability to learn continuous functions makes them well-suited for tasks like image reconstruction and denoising, which are often ill-posed in nature. The paper likely investigates how pre-training INRs on similar datasets enables effective transfer learning, improving performance in solving inverse problems. A key aspect is evaluating if the shared encoder layers in STRAINER lead to faster convergence and higher quality reconstructions compared to traditional methods. The results should demonstrate improved signal quality (e.g., higher PSNR) and faster convergence on various inverse problems. The work also probably highlights the potential of INRs, especially when coupled with transfer learning approaches, to tackle challenging inverse problems across different domains and modalities. Data-driven priors encoded via STRAINER can further enhance the INR’s ability to solve inverse problems effectively. Finally, the paper likely discusses the limitations of the proposed approach and suggests directions for future work, such as exploring other types of inverse problems or improving the robustness of the transfer learning process.

Limitations#

The authors acknowledge that STRAINER’s occasional instability during test-time fitting, manifesting as PSNR drops, requires further investigation. While recovery is typically swift, this issue highlights a need for more robust methods to ensure reliable performance across diverse signals. Another key limitation is the lack of a complete understanding of precisely which features transfer between signals and the degree to which this transfer compares to more established techniques like CNNs or transformers. Further research is needed to completely characterize the transferred features and their behavior under different conditions. Finally, the study primarily focuses on in-domain and related out-of-domain transfers, leaving a gap in understanding its generalization ability to drastically different signal types. Future work should investigate the broader applicability and robustness of STRAINER in truly out-of-domain scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

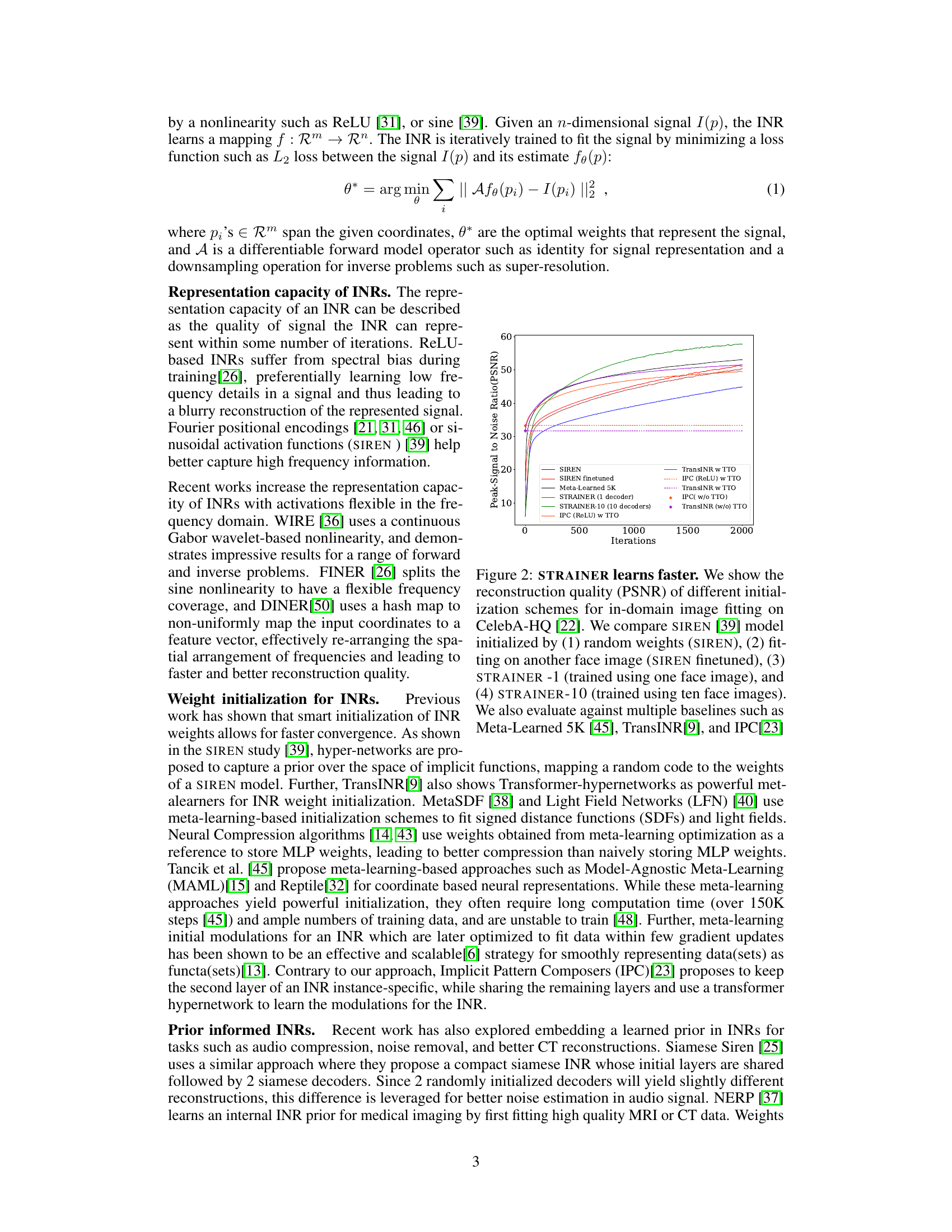

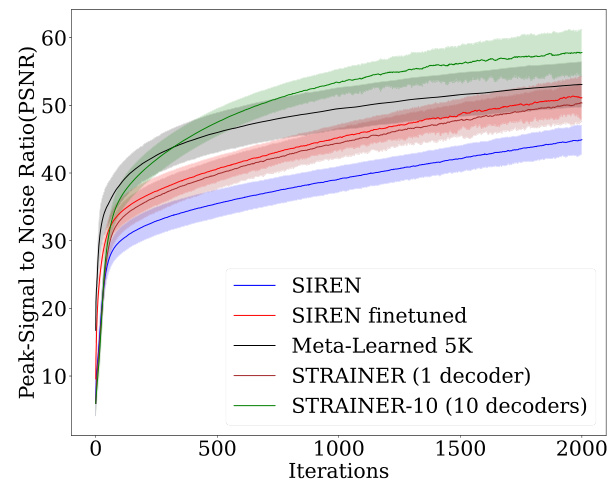

🔼 The figure compares the performance of different INR initialization methods for image fitting on the CelebA-HQ dataset. It demonstrates that STRAINER, particularly STRAINER-10 (trained on 10 images), significantly outperforms other methods, including SIREN (random initialization), SIREN finetuned (initialized using another image), and meta-learning based methods like Meta-Learned 5K, TransINR, and IPC in terms of PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) at different numbers of iterations, showcasing STRAINER’s faster convergence and improved reconstruction quality.

read the caption

Figure 2: STRAINER learns faster. We show the reconstruction quality (PSNR) of different initialization schemes for in-domain image fitting on CelebA-HQ [22]. We compare SIREN [39] model initialized by (1) random weights (SIREN), (2) fitting on another face image (SIREN finetuned), (3) STRAINER -1 (trained using one face image), and (4) STRAINER-10 (trained using ten face images). We also evaluate against multiple baselines such as Meta-Learned 5K [45], TransINR[9], and IPC[23]

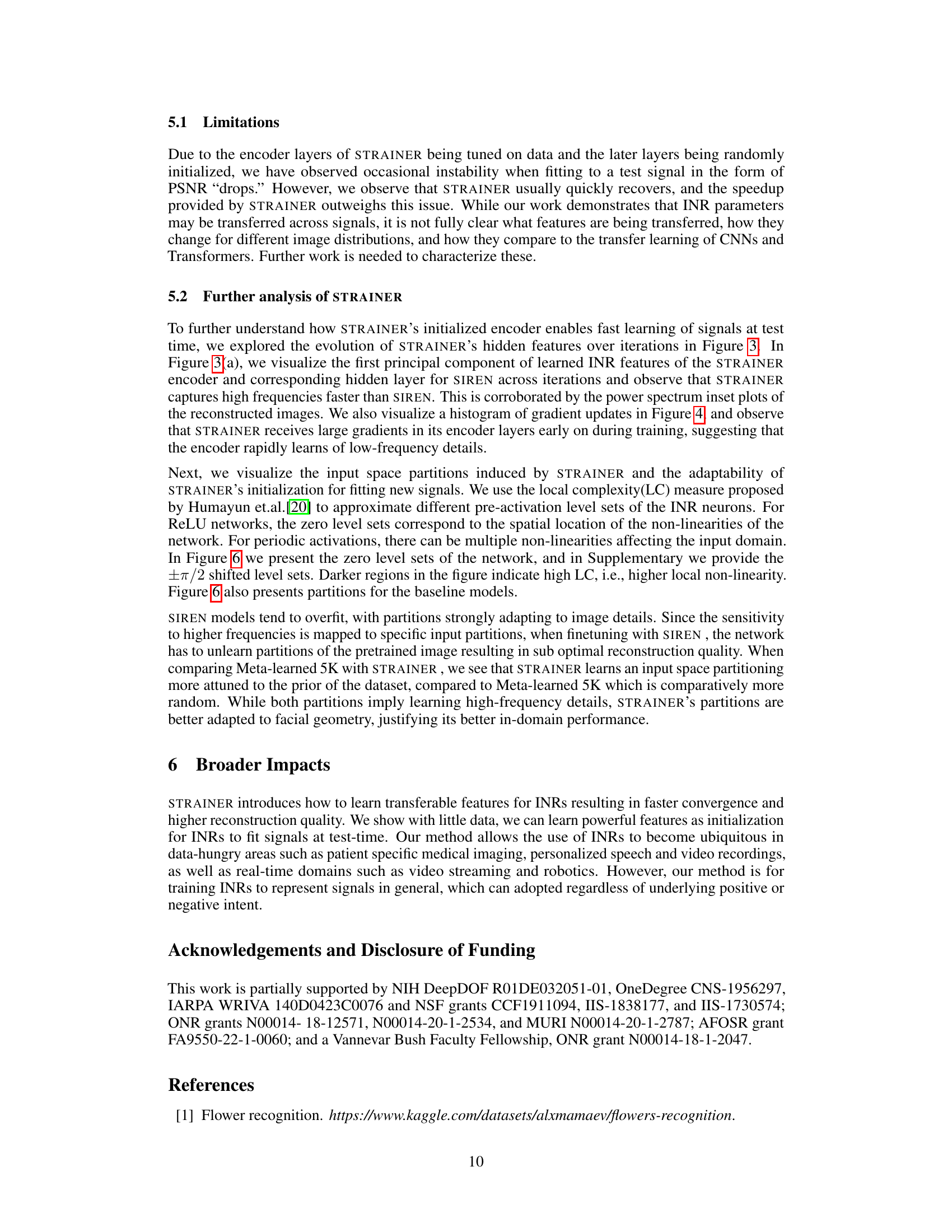

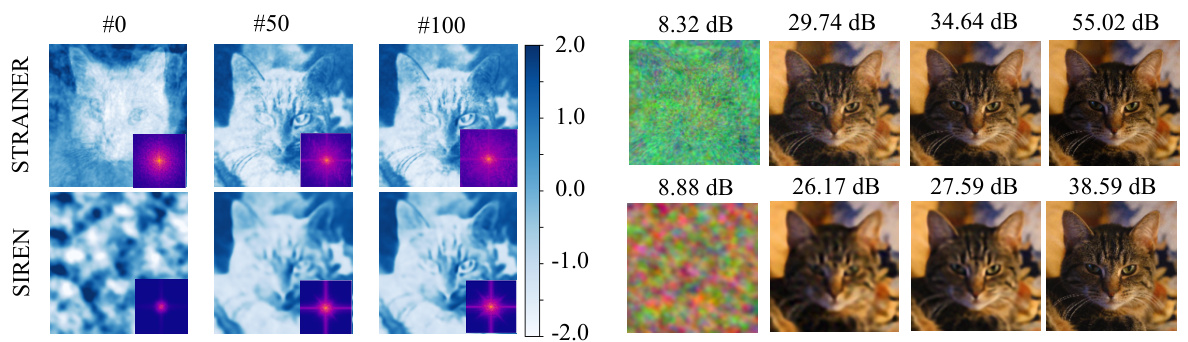

🔼 This figure compares the learned features of STRAINER and SIREN models at different iterations (0, 50, 100). It shows that STRAINER learns low-dimensional structures quickly and captures high-frequency details faster than SIREN, as evidenced by the principal component analysis (PCA) of learned features and the power spectra of reconstructed images. The reconstructed images further illustrate STRAINER’s superior performance in fitting high frequencies.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visualization of learned features in STRAINER and baseline SIREN model. We visualize (a) the first principal component of the learned encoder features for STRAINER and corresponding layer for SIREN. At iteration 0, STRAINER's features already capture a low dimensional structure allowing it to quickly adapt to the cat image. High frequency detail emerges in STRAINER's learned features by iteration 50, whereas SIREN is lacking at iteration 100. The inset showing the power spectrum of the reconstructed image further confirms that STRAINER learns high frequency faster. We also show the (b) reconstructed images and remark that STRAINER fits high frequencies faster.

🔼 This figure compares the convergence speed of STRAINER and SIREN models when fitting an unseen signal. The histograms of absolute gradients for three different layers (1, 5, and the last layer) are plotted over 1000 iterations. STRAINER shows faster convergence to both low and high frequencies than SIREN, highlighting its superior initialization.

read the caption

Figure 4: STRAINER converges to low and high frequencies fast. We plot the histogram of absolute gradients of layers 1, 5 and last over 1000 iterations while fitting an unseen signal. At test time, STRAINER’s initialization quickly learns low frequency, receiving large gradients update at the start in its initial layers and reaching convergence. The Decoder layer in STRAINER also fits high frequency faster. Large gradients from corresponding SIREN layers show it learning significant features as late as 1000 iterations.

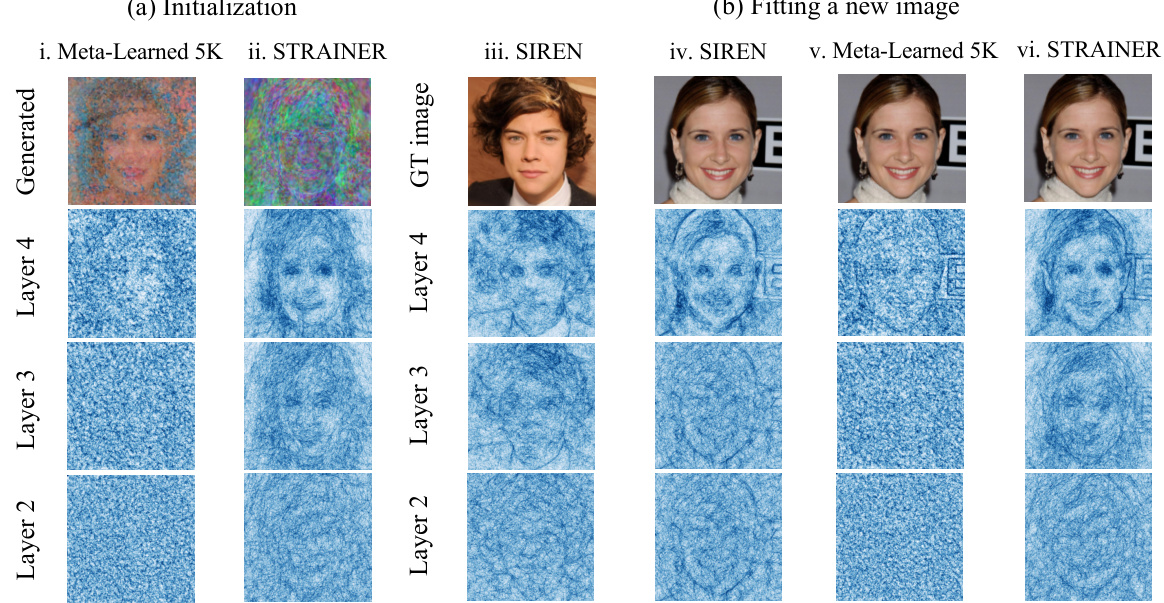

🔼 This figure visualizes how different methods partition the input space when learning INRs. Panel (a) shows the initial partitioning of the input space for Meta-Learned 5K, STRAINER, and SIREN. Panel (b) shows how these partitions change after fitting a new image. STRAINER demonstrates a more structured and data-driven partitioning compared to the other methods, improving transferability to new signals.

read the caption

Figure 6: Visualizing density of partitions in input space of learned models. We use the method introduced in [20] to approximate the input space partition of the INR. We present the input space partitions for layers 2,3,4 across (a) Meta-learned 5K and STRAINER initialization and (b) at test time optimization. STRAINER learns an input space partitioning which is more attuned to the prior of the dataset, compared to meta learned which is comparatively more random. We also observe that SIREN (iii) learns an input space partitioning highly specific to the image leading to inefficient transferability for fitting a new image (iv) with significantly different underlying partitioned input space. This explains the better in-domain performance of STRAINER compared to Meta-learned 5K, as the shallower layers after pre-training provide a better input space subdivision to the deeper layers to further subdivide.

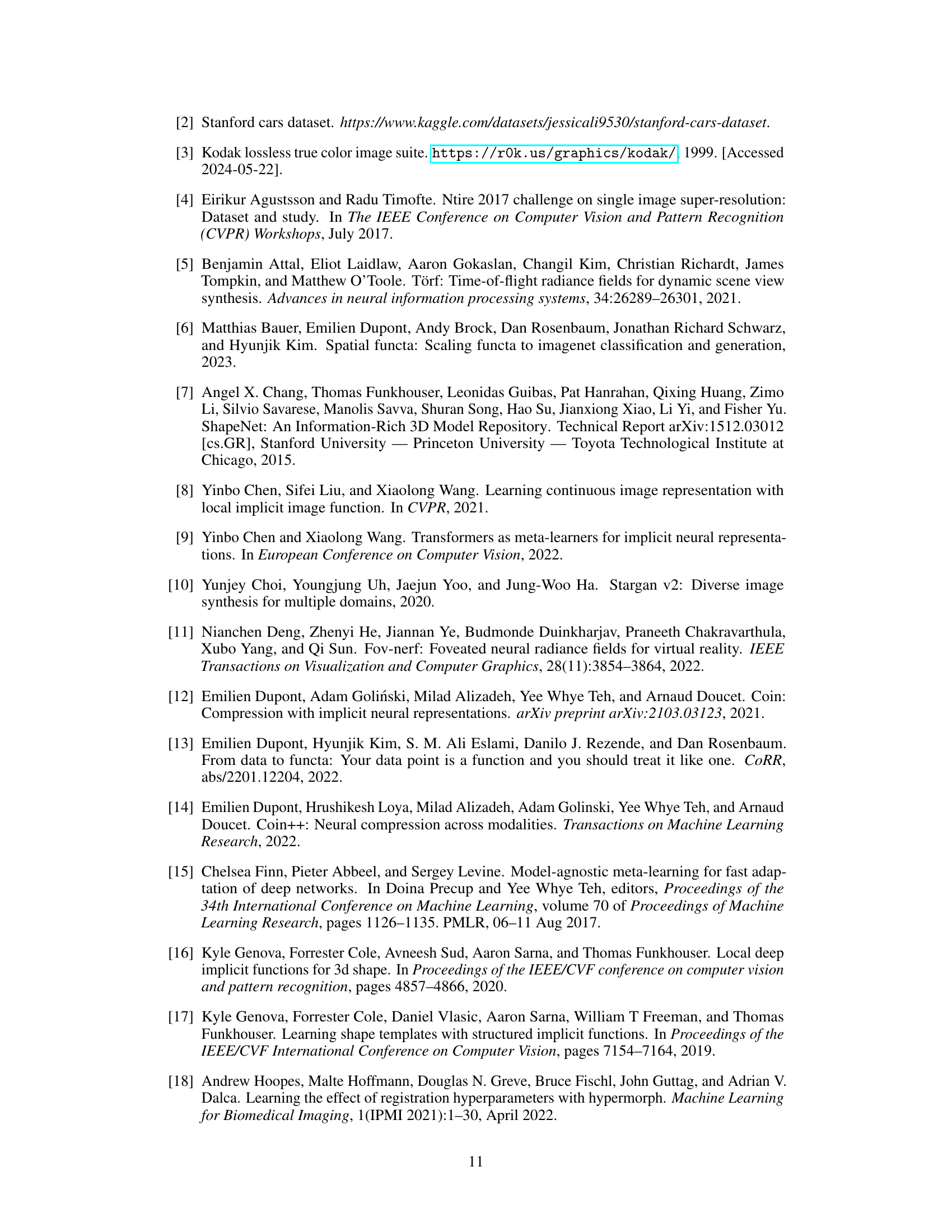

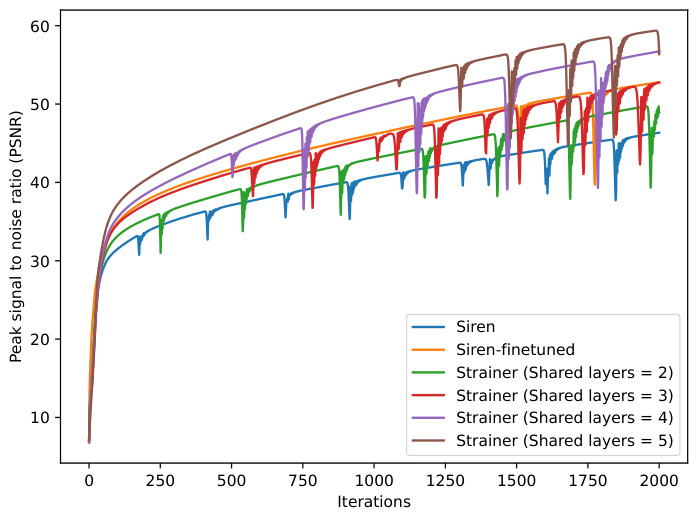

🔼 This figure shows the impact of varying the number of shared layers in the STRAINER model on the reconstruction quality (PSNR). The experiment uses a 5-layered SIREN model, fitting one image. It compares a baseline SIREN model, a fine-tuned SIREN, and different versions of STRAINER, where STRAINER is modified to share an increasing number of initial layers (2, 3, 4, 5) while fitting an image. The results clearly demonstrate that increasing the number of shared layers leads to better reconstruction quality, as measured by PSNR. This highlights the importance of shared encoder layers in STRAINER’s ability to learn transferable features and achieve faster and better signal reconstruction.

read the caption

Figure 7: Sharing different number of layers in STRAINER's encoder. We see that by increasing the number of shared layers, STRAINER's ability to recover the signal also improves.

🔼 This figure illustrates the STRAINER framework for learning transferable features in Implicit Neural Representations (INRs). Panel (a) shows the training process where multiple INRs are trained simultaneously, sharing encoder layers while having separate decoder layers. This allows STRAINER to learn generalizable features from similar signals. Panel (b) demonstrates the testing phase where the pre-trained encoder is used to initialize a new INR for a previously unseen signal. Panel (c) compares the reconstruction quality of an INR initialized with STRAINER’s encoder against a baseline SIREN model, showcasing STRAINER’s improved speed and accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 1: STRAINER - Learning Transferable Features for Implicit Neural Representations. During training time (a), STRAINER divides an INR into encoder and decoder layers. STRAINER fits similar signals while sharing the encoder layers, capturing a rich set of transferrable features. At test-time, STRAINER serves as powerful initialization for fitting a new signal (b). An INR initialized with STRAINER's learned encoder features achieves (c) faster convergence and better quality reconstruction compared to baseline SIREN models.

🔼 The figure compares the performance of different INR initialization methods on a face image fitting task using PSNR metric. STRAINER, which uses a shared encoder trained on multiple images, shows significant improvement in reconstruction quality and convergence speed over baselines like SIREN (random initialization), SIREN finetuned (fine-tuned on a single image), and Meta-Learned 5K.

read the caption

Figure 2: STRAINER learns faster. We show the reconstruction quality (PSNR) of different initialization schemes for in-domain image fitting on CelebA-HQ [22]. We compare SIREN [39] model initialized by (1) random weights (SIREN), (2) fitting on another face image (SIREN finetuned), (3) STRAINER -1 (trained using one face image), and (4) STRAINER-10 (trained using ten face images). We also evaluate against multiple baselines such as Meta-Learned 5K [45], TransINR[9], and IPC[23]

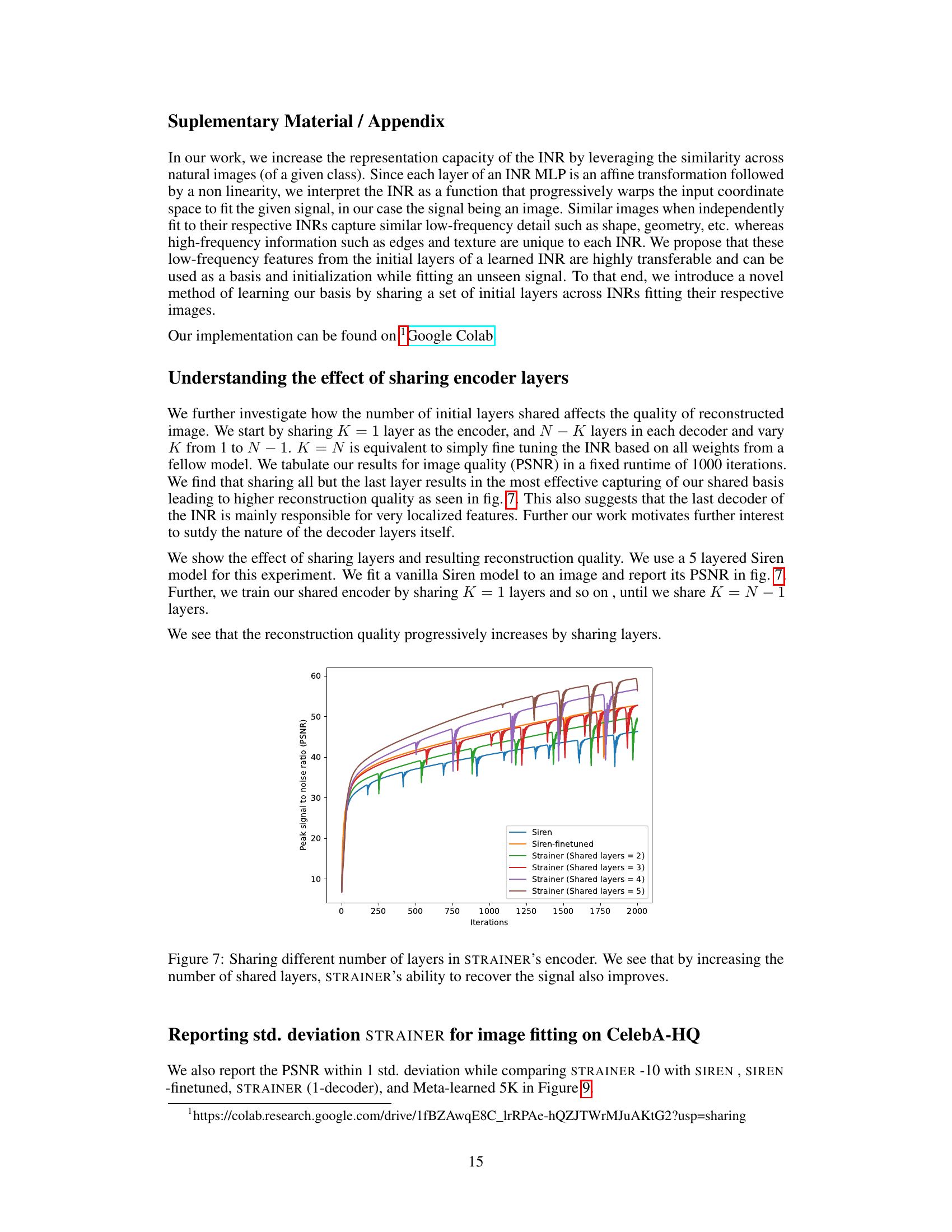

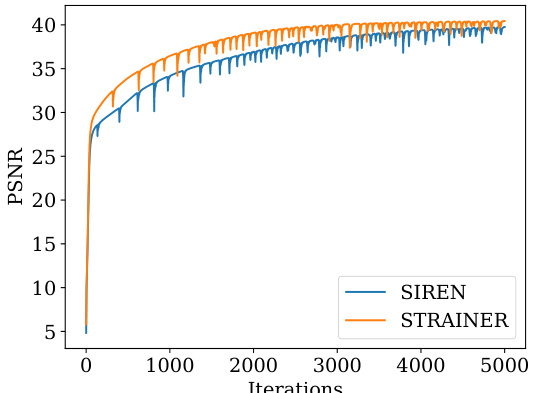

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of the super-resolution results achieved by SIREN and STRAINER. The left side displays visual results of super-resolution on a sample image using both methods. The right side presents a plot showing how the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) changes over iterations. The plot illustrates that STRAINER-10(Fast) achieves similar performance to SIREN but requires significantly fewer iterations to reach the same PSNR value, showing its faster convergence for super-resolution tasks. The HQ version of STRAINER-10 is also included for further comparison.

read the caption

Figure 10: Super Resolution using STRAINER. We show the reconstructed results (a) on the left using SIREN and STRAINER. We also plot (b) the trajectory of PSNR with iterations. STRAINER-10 (Fast) achieves comparable PSNR to SIREN in approximately a third of the runtime.

🔼 The figure shows the PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) of different INR (Implicit Neural Representation) initialization methods over training iterations for fitting in-domain face images from the CelebA-HQ dataset. It compares the performance of a standard SIREN model, a fine-tuned SIREN model, STRAINER with 1 decoder, STRAINER with 10 decoders, and other meta-learning baselines (Meta-Learned 5K, TransINR, IPC). STRAINER, which shares encoder layers across multiple INRs during training, demonstrates faster convergence and superior PSNR compared to the other methods, highlighting the effectiveness of its transfer learning approach.

read the caption

Figure 2: STRAINER learns faster. We show the reconstruction quality (PSNR) of different initialization schemes for in-domain image fitting on CelebA-HQ [22]. We compare SIREN [39] model initialized by (1) random weights (SIREN), (2) fitting on another face image (SIREN finetuned), (3) STRAINER -1 (trained using one face image), and (4) STRAINER-10 (trained using ten face images). We also evaluate against multiple baselines such as Meta-Learned 5K [45], TransINR[9], and IPC[23]

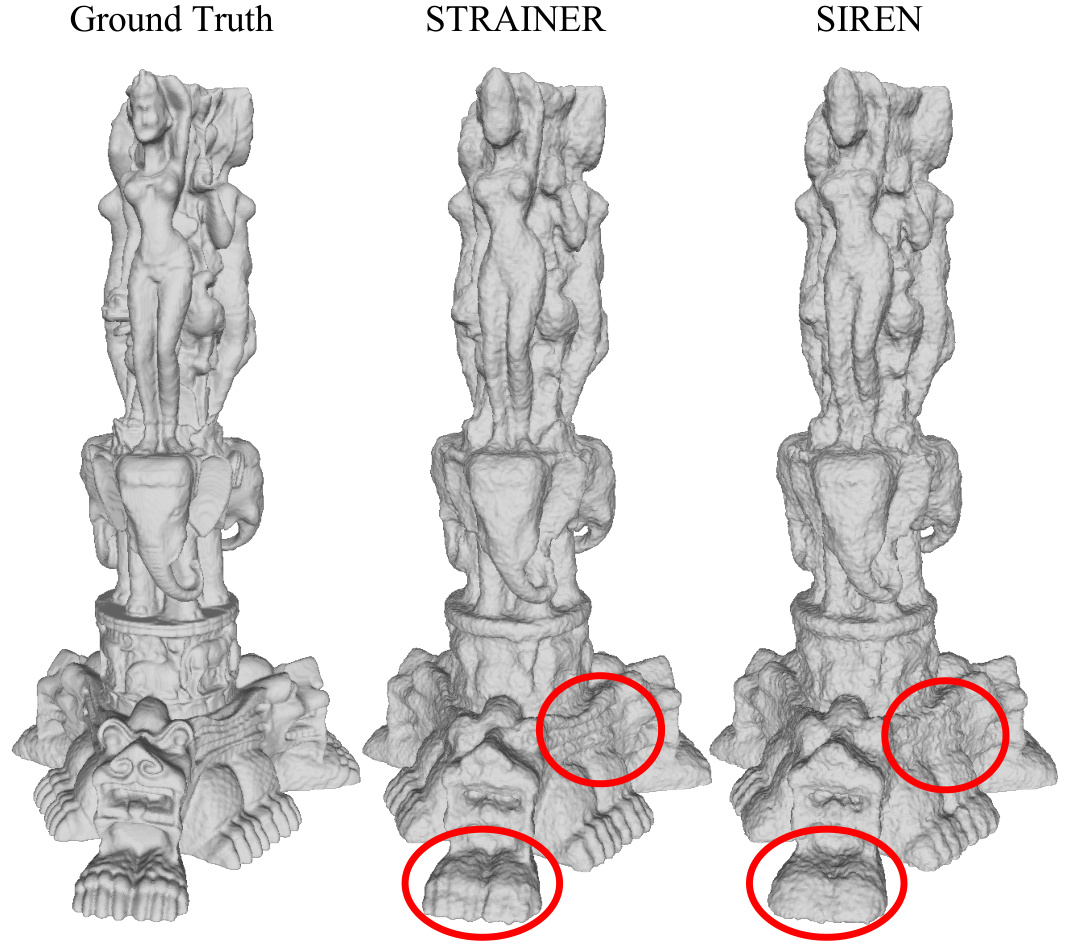

🔼 This figure compares the performance of STRAINER and SIREN in reconstructing a complex 3D model (Thai statue) after being trained on a simpler dataset (chair shapes from ShapeNet). The ground truth, STRAINER reconstruction, and SIREN reconstruction are shown. Red circles highlight areas where STRAINER shows superior detail and faster convergence to high-frequency information, demonstrating the effectiveness of STRAINER’s transferable features.

read the caption

Figure 12: We use ten shapes from the chair category of ShapeNet[7] to train STRAINER, and use that initialization to fit a much more complex volume (the Thai statue[35]). We compare the intermediate outputs for both STRAINER and SIREN for 150 iterations to highlight STRAINER’s ability to learn ridges and high frequency information faster.

🔼 This figure visualizes the learned features of STRAINER and compares them to a baseline SIREN model. The PCA of learned features highlights how STRAINER captures low-dimensional structure early in training, enabling quicker adaptation to new signals. The power spectrum of reconstructed images confirms that STRAINER learns high frequencies faster than SIREN. Reconstructed images further illustrate STRAINER’s superior performance.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visualization of learned features in STRAINER and baseline SIREN model. We visualize (a) the first principal component of the learned encoder features for STRAINER and corresponding layer for SIREN. At iteration 0, STRAINER's features already capture a low dimensional structure allowing it to quickly adapt to the cat image. High frequency detail emerges in STRAINER's learned features by iteration 50, whereas SIREN is lacking at iteration 100. The inset showing the power spectrum of the reconstructed image further confirms that STRAINER learns high frequency faster. We also show the (b) reconstructed images and remark that STRAINER fits high frequencies faster.

🔼 This figure illustrates the STRAINER framework for learning transferable features in Implicit Neural Representations (INRs). Panel (a) shows the training phase where multiple INRs share encoder layers while having independent decoder layers. This shared encoder learns transferable features across signals. Panel (b) demonstrates the test phase where the learned encoder from (a) is used to initialize a new INR for a new signal, resulting in faster convergence. Panel (c) shows the result of the improved reconstruction quality achieved by using STRAINER compared to a baseline method (SIREN).

read the caption

Figure 1: STRAINER - Learning Transferable Features for Implicit Neural Representations. During training time (a), STRAINER divides an INR into encoder and decoder layers. STRAINER fits similar signals while sharing the encoder layers, capturing a rich set of transferrable features. At test-time, STRAINER serves as powerful initialization for fitting a new signal (b). An INR initialized with STRAINER's learned encoder features achieves (c) faster convergence and better quality reconstruction compared to baseline SIREN models.

🔼 This figure visualizes how different models partition the input space at initialization and after fitting an image. STRAINER shows a more structured and data-driven partitioning compared to Meta-Learned 5K and SIREN. This structured partitioning explains its better transferability and faster convergence.

read the caption

Figure 6: Visualizing density of partitions in input space of learned models. We use the method introduced in [20] to approximate the input space partition of the INR. We present the input space partitions for layers 2,3,4 across (a) Meta-learned 5K and STRAINER initialization and (b) at test time optimization. STRAINER learns an input space partitioning which is more attuned to the prior of the dataset, compared to meta learned which is comparatively more random. We also observe that SIREN (iii) learns an input space partitioning highly specific to the image leading to inefficient transferability for fitting a new image (iv) with significantly different underlying partitioned input space. This explains the better in-domain performance of STRAINER compared to Meta-learned 5K, as the shallower layers after pre-training provide a better input space subdivision to the deeper layers to further subdivide.

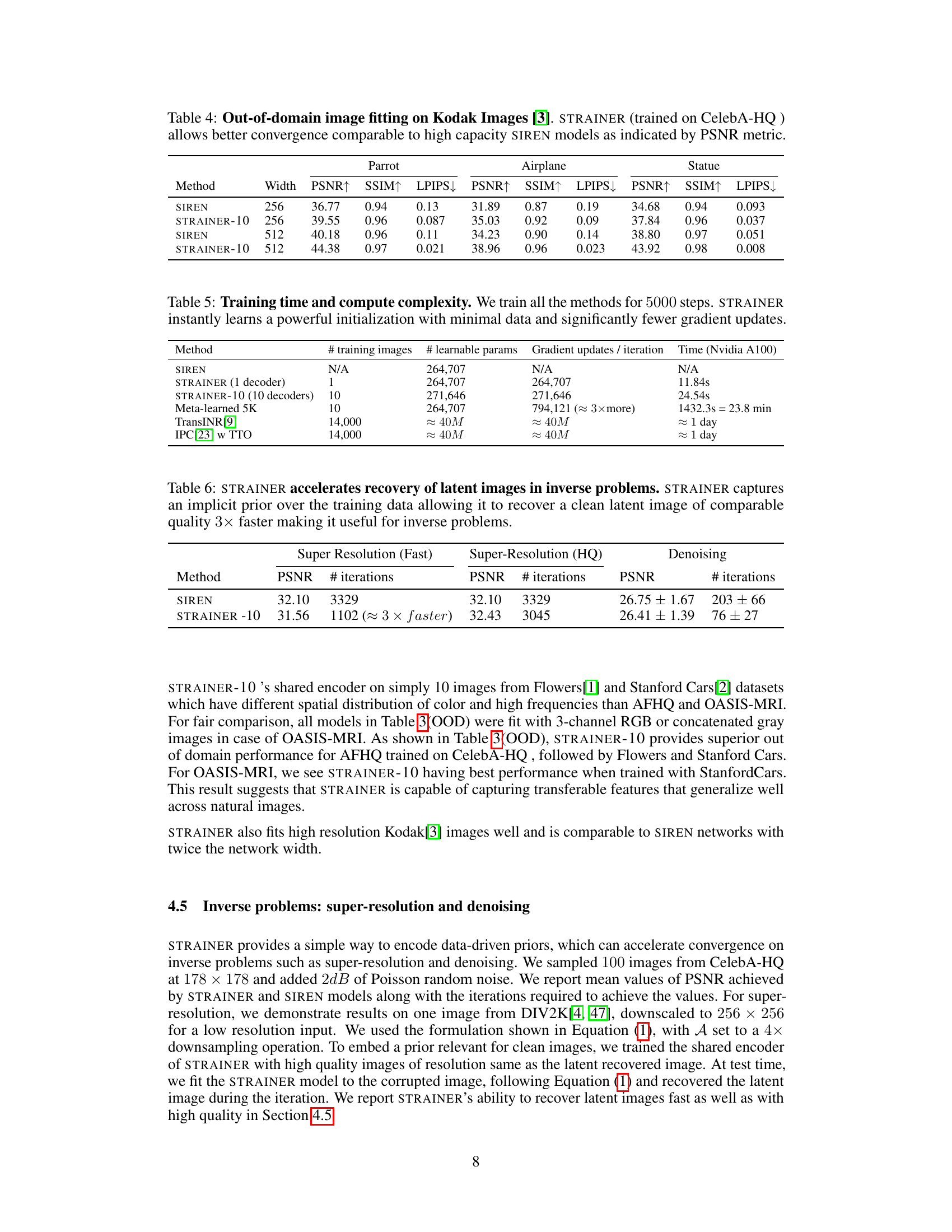

More on tables

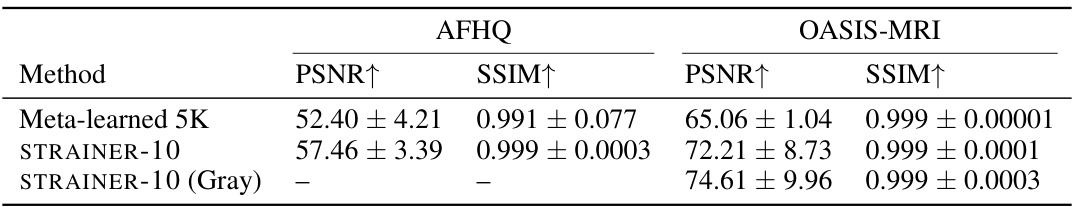

🔼 This table presents the results of out-of-domain image fitting experiments. The model was initially trained on CelebA-HQ images (faces) and then tested on images from two different datasets: AFHQ (animal faces, specifically cats) and OASIS-MRI (medical images). The table compares the performance of Meta-learned 5K and two versions of STRAINER (STRAINER-10 and STRAINER-10 (Gray), where the latter uses a grayscale version of the data). The metrics used for comparison are Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM). The results show that STRAINER outperforms Meta-learned 5K in all cases, demonstrating that the features learned during training on one dataset generalize effectively to other datasets.

read the caption

Table 2: Out of domain image fitting evaluation, when trained on CelebA-HQ and tested on AFHQ and OASIS-MRI. STRAINER's learned features are a surprisingly good prior for fitting images out of its training domain.

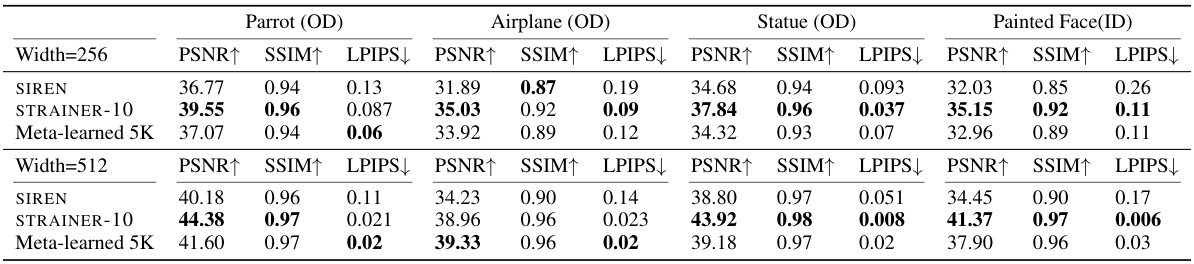

🔼 This table compares the performance of STRAINER with several baselines on image fitting tasks, both within the same domain (in-domain) and across different domains (out-of-domain). It shows that STRAINER consistently outperforms the baselines in terms of PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), demonstrating the effectiveness of its transferable feature learning approach. The results highlight STRAINER’s ability to generalize to unseen data, even when the data is from a different domain than the training data. The table also includes results for models with and without test-time optimization (TTO), further showcasing STRAINER’s advantage.

read the caption

Table 3: Baseline evaluation for image-fitting for in-domain(ID) and out-of-domain(OD) data. STRAINER learns more transferable features resulting in better performance across the board. Models trained on CelebA-HQ unless mentioned otherwise. TTO = Test time optimization.

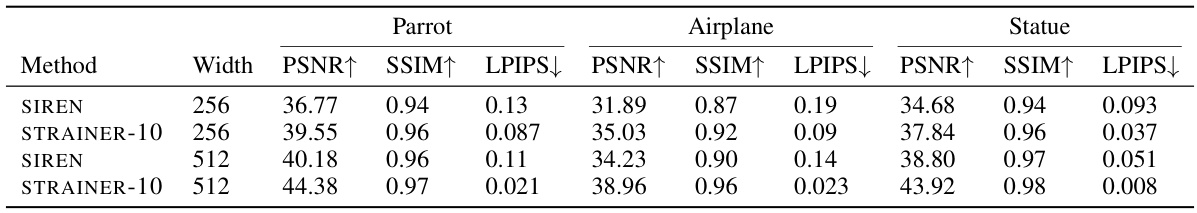

🔼 This table shows the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural SIMilarity index (SSIM), and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) for out-of-domain image fitting on Kodak images. The results compare the performance of STRAINER-10 (trained on the CelebA-HQ dataset) against standard SIREN models with different network widths (256 and 512). The metric values show that STRAINER-10 achieves better PSNR, SSIM, and lower LPIPS, indicating higher-quality image reconstruction and better perceptual similarity, especially for the wider network (512).

read the caption

Table 4: Out-of-domain image fitting on Kodak Images [3]. STRAINER (trained on CelebA-HQ) allows better convergence comparable to high capacity SIREN models as indicated by PSNR metric.

🔼 This table compares the training time and computational complexity of STRAINER with other methods. It shows that STRAINER requires significantly less training time and fewer gradient updates than other methods, even when trained on a smaller dataset. This highlights STRAINER’s efficiency and its ability to leverage a powerful initialization.

read the caption

Table 5: Training time and compute complexity. We train all the methods for 5000 steps. STRAINER instantly learns a powerful initialization with minimal data and significantly fewer gradient updates.

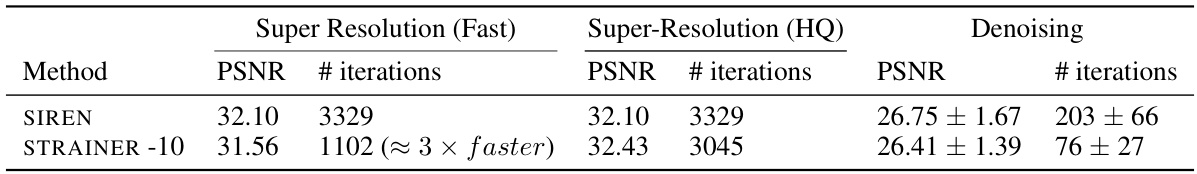

🔼 This table presents the results of applying the STRAINER method to inverse problems, specifically super-resolution and denoising. It shows that STRAINER achieves comparable or better PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) than the baseline SIREN method in significantly fewer iterations, highlighting its efficiency and effectiveness for these tasks.

read the caption

Table 6: STRAINER accelerates recovery of latent images in inverse problems. STRAINER captures an implicit prior over the training data allowing it to recover a clean latent image of comparable quality 3x faster making it useful for inverse problems.

🔼 This table presents the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) values achieved by different methods for in-domain image fitting tasks on three datasets: CelebA-HQ, AFHQ, and OASIS-MRI. It compares the performance of SIREN (a baseline implicit neural representation model), a fine-tuned SIREN model, Meta-learned 5K (a meta-learning based initialization method), STRAINER (with one decoder), and STRAINER-10 (with ten decoders). The results demonstrate that STRAINER, particularly STRAINER-10, achieves significantly better PSNR and SSIM values compared to the baselines, indicating its effectiveness in leveraging learned transferable features for faster and higher-quality in-domain image fitting.

read the caption

Table 1: In-domain image fitting evaluation. STRAINER's learned features yield powerful initialization at test-time resulting in high quality in-domain image fitting

Full paper#