↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional multi-armed bandit problems assume the learner receives numerical rewards for each action. However, many real-world scenarios provide only partial or ranked feedback, like human preferences in matchmaking. This paper addresses this gap by introducing “bandits with ranking feedback,” where learners receive feedback as a ranking of arms based on previous interactions. This framework raises important theoretical questions on the role of numerical rewards in bandit algorithms and how they affect regret bounds.

The researchers investigate the problem of designing no-regret algorithms for bandits with ranking feedback under both stochastic and adversarial reward settings. They prove that sublinear regret is impossible in adversarial cases. For stochastic settings, they demonstrate the instance-dependent case requires superlogarithmic regret, differing significantly from traditional bandit results. They propose two new algorithms: DREE, guaranteeing a superlogarithmic regret matching a theoretical lower bound, and R-LPE, achieving Õ(√T) regret in instance-independent scenarios with Gaussian rewards. This work provides a comprehensive analysis of a novel bandit setting and contributes new algorithms with theoretically-sound regret bounds.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel bandit problem with ranking feedback, a more realistic scenario in many applications involving human preferences or sensitive data. It challenges the existing assumptions in bandit algorithms by demonstrating that numerical rewards are not always necessary, and it provides new algorithms tailored for stochastic settings. This opens exciting new avenues for research in preference learning, online advertising, and recommendation systems, all of which deal with partial information of user preferences. The algorithms designed could significantly impact real-world applications by handling incomplete data in many crucial settings.

Visual Insights#

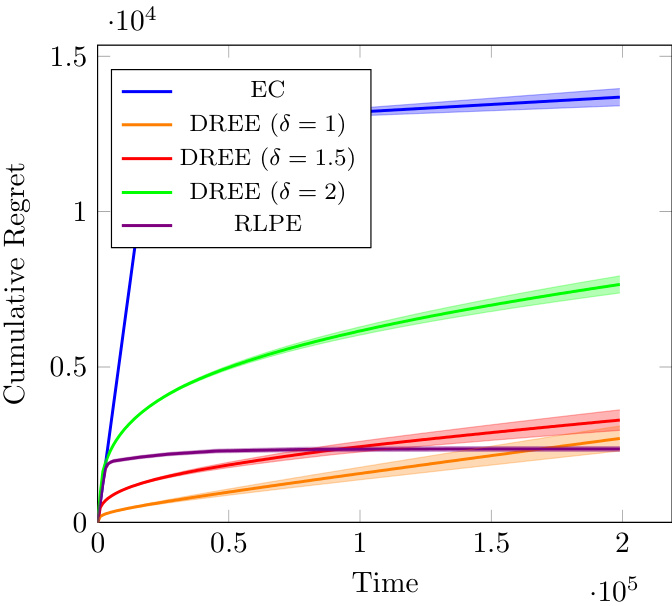

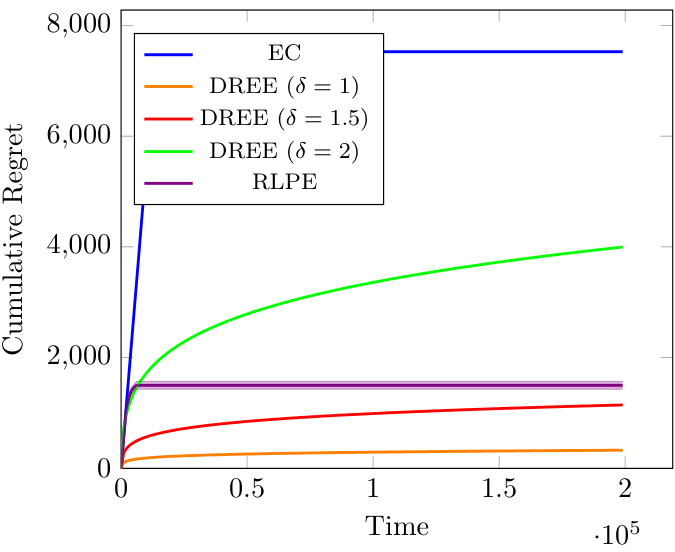

The figure shows the cumulative regret of different algorithms (EC, DREE with different delta values, and RLPE) over time. The instance used has a minimum gap (Amin) of 0.03 between the expected rewards of the arms, and all gaps are relatively small. The shaded areas represent the 95% confidence intervals over 50 runs. The plot demonstrates the performance of these algorithms in a scenario with small reward differences.

The table presents the instance-dependent regret upper bound achieved by the Dynamical Ranking Exploration-Exploitation (DREE) algorithm. It shows that the algorithm’s regret is bounded by a function that depends on the suboptimality gaps (∆i) of the suboptimal arms and a superlogarithmic function f(T). The specific form of the bound highlights a trade-off between exploration (f(T)) and exploitation (∆i).

In-depth insights#

Ranking Bandits#

Ranking bandits, a subfield of multi-armed bandits, presents a unique challenge by focusing on learning from relative feedback, namely rankings, rather than precise numerical rewards. This paradigm shift is particularly relevant in scenarios where quantifying rewards is difficult, expensive, or even impossible. The core problem in ranking bandits is efficiently balancing exploration (sampling different arms to learn their relative positions) and exploitation (selecting the currently perceived best arm based on the rankings). Unlike standard bandits with scalar feedback, algorithms for ranking bandits must cleverly infer underlying preferences from comparative data. The design and analysis of effective algorithms are complicated by the inherent partial observability of the reward structure and the need to manage the combinatorial nature of rankings. Consequently, theoretical guarantees, particularly regarding regret bounds, demand careful considerations of the informational content embedded within the ranking data and the complexities of the exploration-exploitation tradeoff in such settings. Developing practical and efficient algorithms, particularly with scalability in mind, is another critical aspect of this research area, with significant implications for applications involving preferences, comparisons, and pairwise comparisons.

Partial Feedback#

The concept of ‘Partial Feedback’ in machine learning, particularly within the context of multi-armed bandit problems, introduces significant challenges and opportunities. Partial feedback mechanisms deviate from the standard full-information setting, where the learner receives the complete reward associated with each action. Instead, partial feedback provides incomplete or indirect information about the rewards. This incompleteness could stem from various factors, including noisy observations, censored data, or only receiving ordinal information like rankings rather than precise numerical values. The core challenge lies in designing effective learning algorithms that can successfully balance exploration (gathering information) and exploitation (optimizing rewards) with limited feedback. Strategies like exploration-exploitation trade-offs become crucial, requiring careful design to minimize regret (the difference between the rewards obtained and those that would have been obtained with full information). While more complex to handle, partial feedback models are often more realistic, reflecting scenarios in areas like recommendation systems, where users might provide implicit feedback (clicks, ratings) rather than explicit numerical scores. Therefore, research into efficient partial feedback algorithms is pivotal for advancing the applicability of machine learning to real-world problems. It also raises important theoretical questions about the fundamental limits of learning with incomplete data, and new theoretical approaches are needed to understand and address the unique challenges posed by partial feedback.

Regret Bounds#

Regret bounds are a crucial concept in the analysis of online learning algorithms, particularly in the context of multi-armed bandit problems. They quantify the difference between the cumulative reward obtained by an algorithm and that of an optimal strategy that has full knowledge of the reward distributions. Tight regret bounds demonstrate the algorithm’s efficiency, ideally exhibiting logarithmic growth with respect to the time horizon (logarithmic regret). However, the nature of feedback significantly impacts achievable bounds. The paper explores variations where the learner receives rankings rather than numerical rewards, presenting a more challenging scenario. In the stochastic setting, instance-dependent lower bounds show a fundamental limit on regret, exceeding the typical logarithmic regret achievable with numerical rewards. Algorithms are presented that match these lower bounds in specific cases, highlighting the complexity introduced by ranking feedback. In adversarial settings, the paper demonstrates a fundamental impossibility result: no algorithm can achieve sublinear regret, thus providing a strong contrast with the stochastic case and the impact of reward assumptions.

Algorithm Design#

The algorithm design section of a research paper would delve into the specifics of the methods used to address the research problem. This would likely involve a detailed description of any novel algorithms developed, or a justification for the selection of existing algorithms. A strong algorithm design section would highlight the algorithms’ key components, including their computational complexity (time and space efficiency), and their theoretical guarantees (convergence rates, optimality, etc.). Furthermore, a thorough explanation of the algorithm’s parameters and how they were tuned would be included, along with a discussion on the algorithm’s limitations and potential points of failure. Crucially, it must clearly communicate how the algorithms are specifically tailored to the unique characteristics of the problem, demonstrating an understanding of the algorithm’s strengths and weaknesses within that context. Empirical evaluation and comparison to other methods are usually also discussed, providing context for the algorithm’s performance and its relevance to the broader research area.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the ranking feedback model to incorporate richer feedback mechanisms, such as pairwise comparisons or partial rankings, would enhance the algorithm’s learning capabilities. Investigating the impact of different reward distributions beyond Gaussian is crucial to broaden the algorithm’s applicability. Developing more efficient algorithms that achieve optimal regret bounds in both instance-dependent and instance-independent settings simultaneously would be a significant theoretical advancement. Applying these algorithms to real-world applications with ranking feedback, such as recommender systems or human-computer interaction, would provide valuable insights into their practical performance and limitations. Finally, a rigorous empirical analysis on diverse datasets would solidify the algorithms’ robustness and effectiveness across various application domains.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure shows the cumulative regret of different algorithms (EC, DREE with different delta values, and RLPE) over time for a bandit problem instance with a minimum gap (Amin) of 0.03 and all other gaps being small. The shaded area around each line represents the 95% confidence interval across 50 runs. The graph illustrates how the different algorithms perform in terms of cumulative regret.

The figure shows the cumulative regret of different algorithms (EC, DREE with different delta values, and RLPE) for a bandit problem instance with a small minimum gap (Amin = 0.03) between the expected rewards of the arms. The x-axis represents the time horizon (T), and the y-axis shows the cumulative regret. The shaded regions represent the 95% confidence interval over 50 independent runs. This plot illustrates how the algorithms perform when all the gaps between the arms’ expected rewards are relatively small.

The figure shows the cumulative regret for different bandit algorithms over time. The algorithms include EC, DREE with different delta parameters (1, 1.5, 2), and RLPE. The instance used has a minimum gap (Amin) of 0.03, meaning that the difference between the expected rewards of the best and second-best arms is relatively small. This is a stochastic setting with Gaussian noise. The shaded regions represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Full paper#