↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional clustering often overlooks fairness, particularly in non-centroid scenarios where the loss of an agent is determined by other agents in the same cluster, rather than the distance to a central point (centroid). This poses challenges for ensuring equitable cluster assignments, especially for groups that are large and cohesive. The paper addresses this issue by expanding the proportionally fair clustering framework to non-centroid clustering.

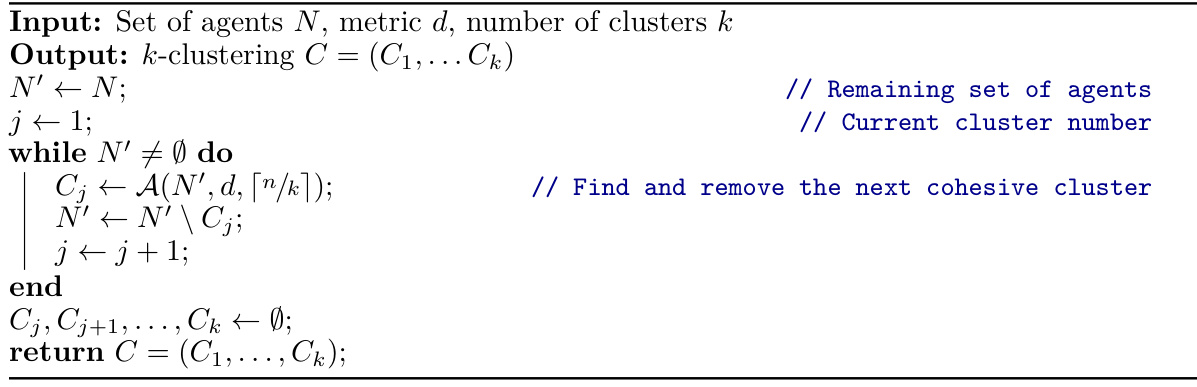

This paper proposes two proportional fairness criteria: the core and its relaxation, fully justified representation (FJR). They develop a novel algorithm (GREEDYCOHESIVECLUSTERING) that achieves FJR exactly under various loss functions. Another efficient algorithm, GREEDYCAPTURE, provides a constant-factor approximation. Furthermore, an efficient auditing algorithm is designed to estimate the FJR approximation of any given clustering solution. Experiments show GREEDYCAPTURE outperforms traditional methods in fairness while maintaining acceptable performance in standard clustering objectives.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in fairness-aware clustering and related fields. It expands the proportionally fair clustering framework to non-centroid settings, addressing limitations of existing work. This opens new avenues for research in fairer clustering algorithms and auditing tools for diverse applications.

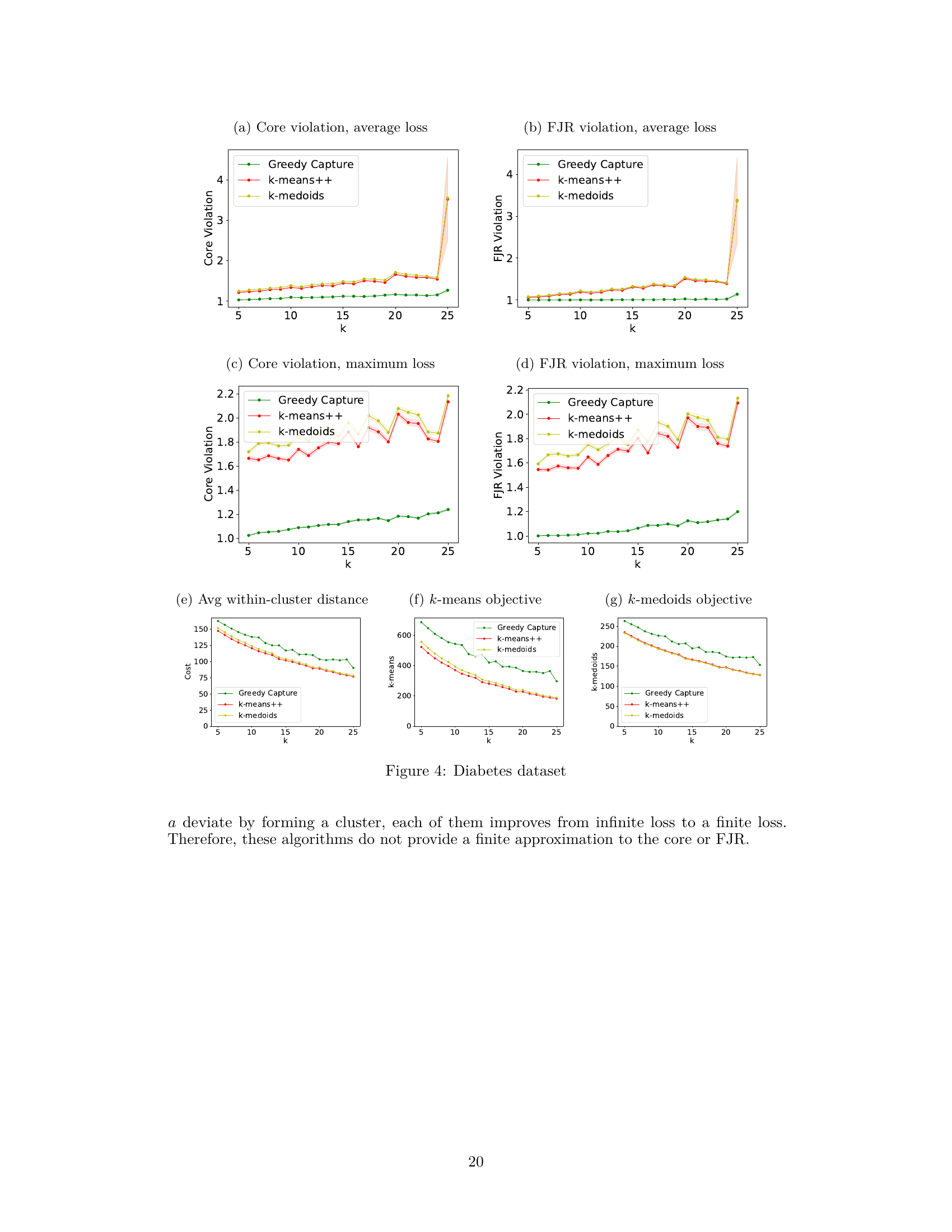

Visual Insights#

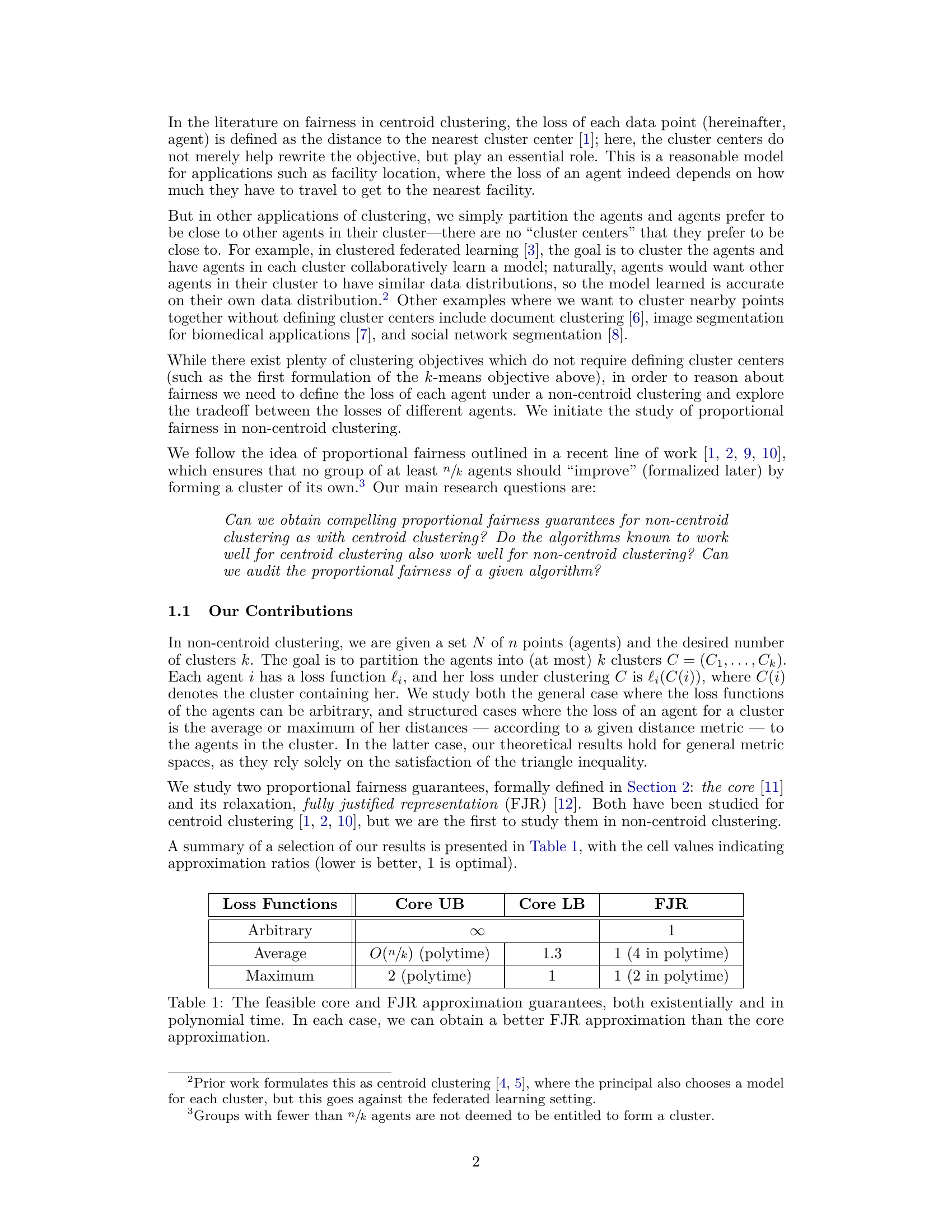

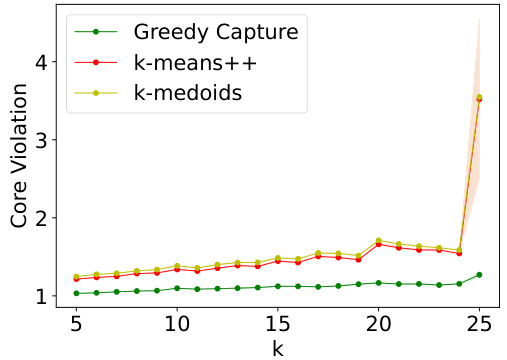

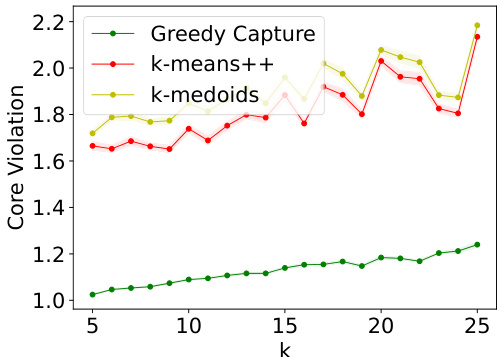

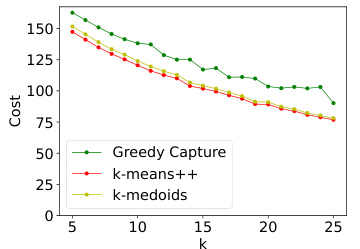

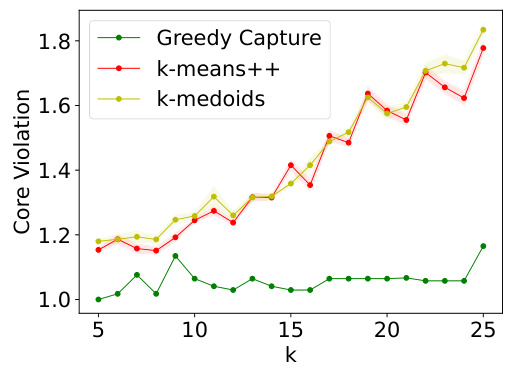

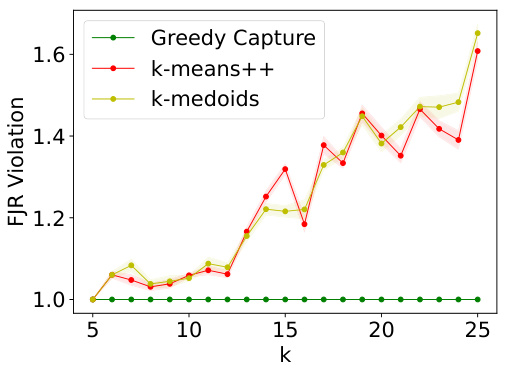

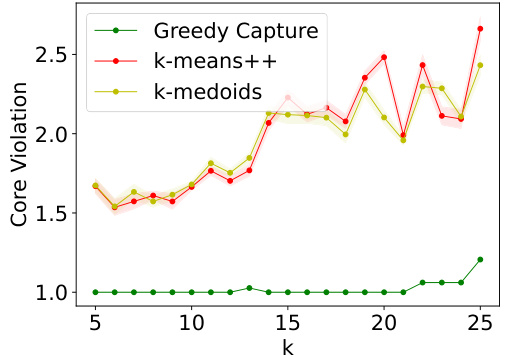

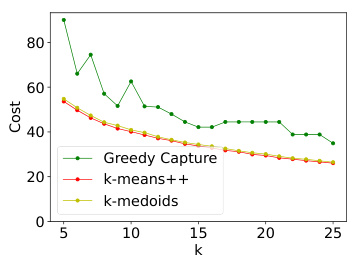

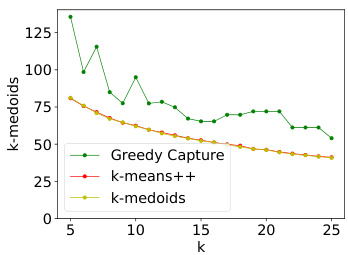

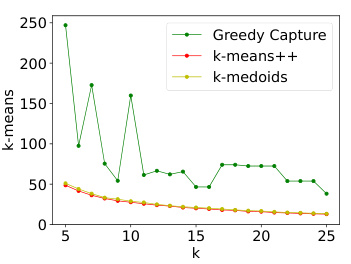

The figure presents the results of comparing GREEDYCAPTURE to k-means++ and k-medoids clustering algorithms across different values of k (number of clusters) using four fairness metrics (core violation, FJR violation, both for average and maximum loss) and three traditional clustering objectives (average within-cluster distance, k-means objective, k-medoids objective). The results reveal that GREEDYCAPTURE provides significantly better fairness approximations than k-means++ and k-medoids across all four fairness metrics. This advantage comes at a modest cost in accuracy as measured by the three clustering objectives.

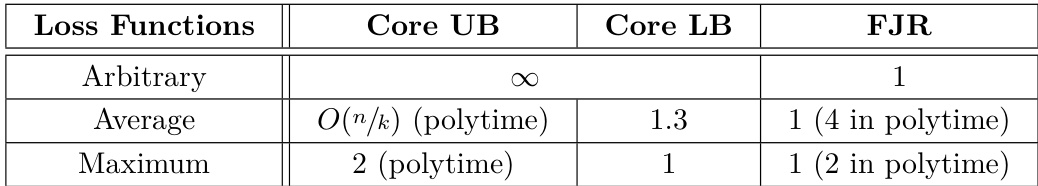

This table summarizes the approximation ratios achieved for the core and FJR (Fully Justified Representation) fairness criteria in non-centroid clustering, categorized by the type of loss function used (arbitrary, average, maximum). Lower approximation ratios indicate better fairness guarantees. The table shows that FJR is always achievable (approximation ratio of 1), while core approximation is more challenging, with ratios varying according to the loss function. The table also notes the time complexity of achieving the approximation bounds (polytime denotes polynomial time).

In-depth insights#

Fair Clustering Intro#

A hypothetical ‘Fair Clustering Intro’ section would likely begin by establishing the context of clustering as a fundamental task in machine learning, emphasizing its widespread applications across various domains. It would then highlight the growing awareness of bias and unfairness in standard clustering algorithms, potentially illustrating this with real-world examples where biased outcomes can have significant negative societal consequences. The introduction should then clearly articulate the core problem: traditional clustering methods often disproportionately affect certain groups, thus failing to provide equitable representations. The section would then smoothly transition into the paper’s main contribution by introducing the concept of fair clustering as a solution to this problem, possibly mentioning different fairness criteria that can be used to assess and ensure fairness. Finally, it should briefly outline the paper’s approach to achieving fair clustering, such as introducing novel algorithms or adapting existing ones, and its contribution to the field of fair machine learning.

Non-Centroid Loss#

In non-centroid clustering, the concept of ‘Non-Centroid Loss’ is crucial because it diverges from traditional centroid-based approaches. Instead of measuring an agent’s loss as its distance to a cluster center, the focus shifts to the relationships within a cluster. This means loss functions are defined based on interactions between data points. The paper likely explores various loss functions, including those based on average or maximum distances within a cluster, reflecting diverse applications like collaborative learning. The choice of loss function significantly impacts the overall fairness guarantees and the algorithm’s ability to find cohesive and balanced clusters. Analyzing the properties of different loss functions—arbitrary, average, maximum—is critical to understanding when proportional fairness criteria can be met and which algorithms best approximate them. The efficiency and scalability of algorithms designed for non-centroid loss functions are also major concerns for this approach. The results show that while centroid algorithms can be modified for this new concept, non-centroid clustering requires dedicated and possibly inefficient algorithms to guarantee proportional fairness.

Core & FJR#

The concepts of “Core” and “Fully Justified Representation” (FJR) are central to the paper’s exploration of proportional fairness in non-centroid clustering. The Core, a strong fairness guarantee, ensures no substantial group of agents would benefit from forming its own cluster. However, the Core’s existence isn’t guaranteed under arbitrary loss functions, limiting its applicability. FJR offers a relaxation of the Core, ensuring no group improves upon the minimum individual loss of any other agent before deviation. This relaxation enhances the theoretical guarantees, making FJR achievable even under unstructured loss functions and often more practical. The paper investigates the approximation properties of both Core and FJR under different loss scenarios. The algorithms proposed, particularly GREEDYCAPTURE, focus on achieving FJR, highlighting a tradeoff between computational efficiency and the strength of fairness guarantees. Ultimately, the analysis of Core and FJR reveals a nuanced understanding of fairness, suggesting that FJR might be a more useful metric than the stronger, but less achievable, Core for real-world non-centroid clustering problems.

Approx. Algos#

The heading ‘Approx. Algos’ likely refers to a section detailing approximation algorithms. These algorithms don’t find the optimal solution but offer a close enough solution within a reasonable timeframe, especially crucial when dealing with computationally hard problems. The paper likely explores the trade-offs between solution accuracy and computational cost. Key aspects to consider in this section would be the approximation guarantees: Does it offer a bounded approximation ratio or a probabilistic guarantee? The algorithm’s efficiency is another critical element: What is the algorithm’s time and space complexity? The section would also likely discuss the practical performance of the approximation algorithms: How do they perform on real-world datasets compared to other methods? The analysis might also cover the impact of approximation on the core fairness metrics studied in the paper. Does the approximation significantly affect the fairness guarantees? Finally, a discussion of the choices made in designing the specific approximation algorithms, comparing and contrasting different approaches, would provide valuable insights.

Empirical Results#

An ‘Empirical Results’ section in a research paper would present data obtained from experiments designed to test the paper’s hypotheses. A strong section would clearly present the datasets used, including their characteristics and limitations. The methodology for conducting the experiments should be meticulously described, enabling reproducibility. The results themselves should be presented in clear and concise tables or figures, with appropriate error bars or other statistical significance measures. Key findings should be prominently highlighted, and their alignment with the study’s core claims should be explicitly stated. A critical analysis of the results, addressing any unexpected outcomes or inconsistencies, is crucial. Furthermore, comparisons with baselines or existing approaches should be included, contextualizing the obtained results and demonstrating their novelty. Finally, limitations of the empirical study itself – such as sample size, the generalizability of the findings, or potential biases – need to be acknowledged to promote transparency and honest self-assessment.

More visual insights#

More on figures

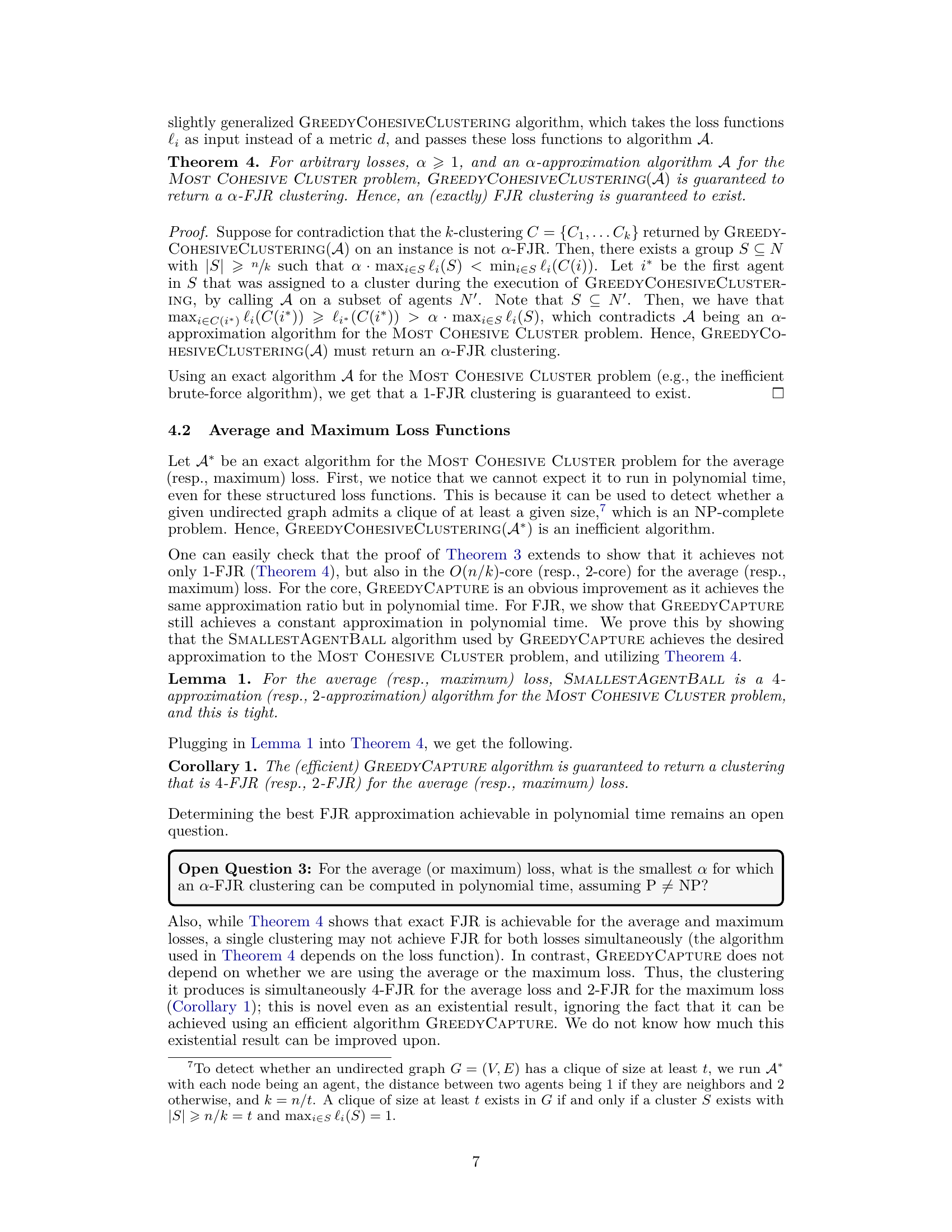

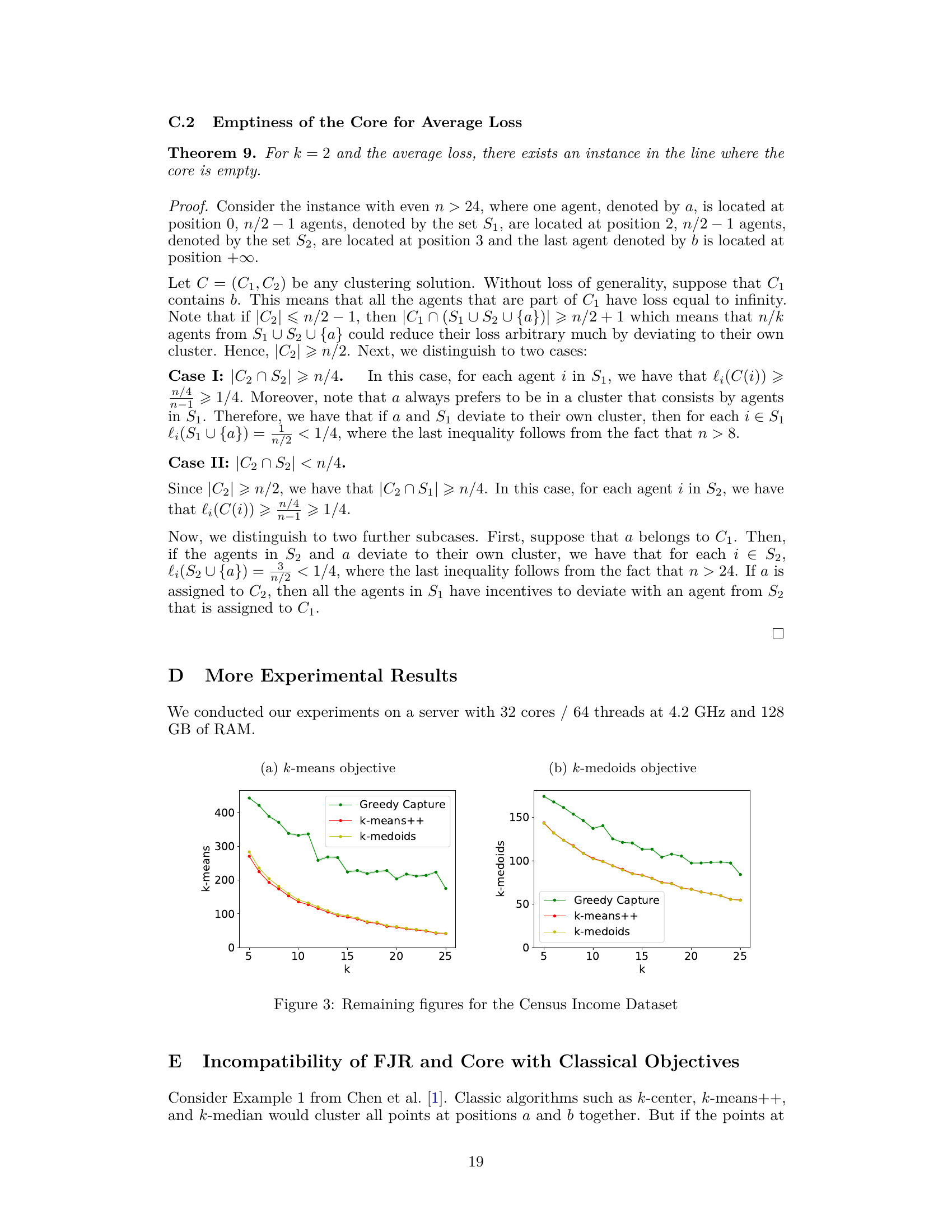

The figure presents the results of experiments on the Census Income dataset. It shows the core violation, FJR violation, and average within-cluster distance for three different clustering algorithms: GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids. The results are shown for different values of k (the number of clusters). The figure demonstrates that GREEDYCAPTURE significantly outperforms k-means++ and k-medoids in terms of fairness (core violation and FJR violation) with a modest loss in accuracy (average within-cluster distance).

The figure compares the performance of three clustering algorithms (Greedy Capture, k-means++, and k-medoids) on the Census Income dataset across different values of k (number of clusters). It shows core violation, FJR violation, and average within-cluster distance for both average and maximum loss functions. Greedy Capture consistently shows lower core and FJR violations across all k, demonstrating its improved fairness compared to traditional algorithms. While Greedy Capture’s accuracy (as measured by the average within-cluster distance) is slightly lower than the other two, the differences are not substantial, suggesting a reasonable trade-off between fairness and accuracy.

This figure presents the results of experiments on the Census Income Dataset, comparing the performance of GREEDYCAPTURE with k-means++ and k-medoids. It shows how these algorithms perform across various metrics, including core violation (both average and maximum loss), FJR violation (both average and maximum loss), and average within-cluster distance. The graphs illustrate that GREEDYCAPTURE achieves a considerably better approximation of both core and FJR compared to the other clustering algorithms. While there is a slight cost to accuracy, as measured by the within-cluster distance, GREEDYCAPTURE significantly improves fairness.

This figure presents the results of the Census Income dataset experiment, comparing the performance of GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids across different values of k (number of clusters). It displays four plots related to fairness metrics: core violation and FJR (Fully Justified Representation) violation, both for average and maximum losses. An additional plot shows average within-cluster distance, a common clustering accuracy metric. The results show GREEDYCAPTURE to be significantly fairer than the other two algorithms, achieving values closer to the ideal of 1 for FJR violation, while maintaining reasonably good accuracy in terms of average within-cluster distance.

This figure presents a comparison of the fairness and accuracy of three clustering algorithms: GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids, on the Census Income dataset. Fairness is measured using core violation and FJR violation, with respect to both average and maximum loss. Accuracy is measured using average within-cluster distance. The results reveal that GREEDYCAPTURE offers significantly better fairness guarantees than the other two algorithms across various values of k (number of clusters), with a modest cost in accuracy. This empirically demonstrates GREEDYCAPTURE’s superior fairness performance.

The figure shows the results of the Census Income dataset, comparing the performance of GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids across different values of k (number of clusters). Four fairness metrics (core violation and FJR violation for both average and maximum losses) and three accuracy metrics (average within-cluster distance, k-means objective, and k-medoids objective) are shown. The results highlight that GREEDYCAPTURE achieves significantly better fairness than the other two algorithms, at a relatively modest cost in accuracy.

This figure shows the performance of three clustering algorithms (GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids) on the Census Income dataset across different numbers of clusters (k). It presents four fairness metrics (core violation and FJR violation for both average and maximum loss) and one accuracy metric (average within-cluster distance). The results demonstrate that GREEDYCAPTURE consistently achieves significantly better fairness compared to the other two algorithms, while incurring only a modest loss in accuracy.

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on the Census Income Dataset. It compares the performance of three clustering algorithms: GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids. The comparison is done using four fairness metrics: core violation (average loss), FJR violation (average loss), core violation (maximum loss), and FJR violation (maximum loss). Additionally, it shows the average within-cluster distance for each algorithm as a measure of clustering accuracy. The x-axis represents the number of clusters (k), and the y-axis represents the values of the metrics. The results indicate that GREEDYCAPTURE achieves significantly better fairness compared to the other two algorithms, with a relatively modest cost in terms of accuracy.

This figure presents the results of an empirical comparison of three clustering algorithms (Greedy Capture, k-means++, and k-medoids) on the Census Income dataset. The comparison is done using four fairness metrics (core violation with average loss, FJR violation with average loss, core violation with maximum loss, FJR violation with maximum loss) and a common clustering objective (average within-cluster distance). The results show that Greedy Capture achieves significantly better fairness than the other two algorithms across different numbers of clusters (k), while incurring only a modest cost in accuracy.

This figure presents the results of the comparison of three clustering algorithms (GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids) on the Census Income dataset. The plots show the core violation and FJR violation for both average and maximum loss, as well as the average within-cluster distance. The results indicate that GREEDYCAPTURE achieves significantly better fairness (lower core and FJR violations) compared to k-means++ and k-medoids, while incurring only a modest loss in terms of traditional clustering objectives.

The figure shows the results of the core violation and FJR violation for three different clustering algorithms (GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids) on the Census Income dataset. It compares the performance of these algorithms in terms of average loss and maximum loss for different numbers of clusters (k). Subplots (a) and (b) show average loss, (c) and (d) show maximum loss, and (e) shows the average within-cluster distance. The results indicate GREEDYCAPTURE consistently outperforms the others in terms of fairness (lower core and FJR violations) while having a modest loss in terms of common clustering objectives (average within-cluster distance).

This figure presents the results of the experiments performed on the Census Income dataset. It compares the performance of three clustering algorithms: GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids, across different values of k (the number of clusters). The figure displays four fairness metrics (core violation and FJR violation for both average and maximum loss), and three common clustering objectives (average within-cluster distance, k-means objective, and k-medoids objective). The results show that GREEDYCAPTURE provides better fairness guarantees, achieving FJR values close to 1, in comparison to the other methods while incurring only a modest loss in accuracy (as measured by the other objectives).

This figure presents a comparison of four fairness metrics (core violation with average loss, FJR violation with average loss, core violation with maximum loss, and FJR violation with maximum loss) and one accuracy metric (average within-cluster distance) across three algorithms (Greedy Capture, k-means++, and k-medoids) on the Census Income dataset for varying numbers of clusters (k). The results show that Greedy Capture consistently outperforms the other two algorithms in terms of fairness, although there is a small increase in average within-cluster distance. This demonstrates that Greedy Capture achieves better fairness properties without incurring a significant cost in terms of the common clustering objective.

This figure shows the performance of three clustering algorithms (Greedy Capture, k-means++, and k-medoids) on the Census Income dataset across different values of k (number of clusters). It presents core and FJR (Fully Justified Representation) violations for both average and maximum loss functions. It also shows the average within-cluster distance (a common clustering objective). The results demonstrate that GREEDYCAPTURE achieves significantly better fairness than the other algorithms while incurring only a modest loss in the standard clustering objective.

This figure displays the results of an experiment comparing three clustering algorithms (Greedy Capture, k-means++, and k-medoids) on the Census Income dataset. The plots show core violation and FJR violation for both average and maximum loss functions, as well as the average within-cluster distance across different numbers of clusters (k). The results highlight the superior fairness of the Greedy Capture algorithm compared to the traditional methods, while showing a modest compromise in terms of common clustering objectives.

The figure presents a comparison of different clustering algorithms (Greedy Capture, k-means++, and k-medoids) across various fairness metrics (core violation, FJR violation) and a common clustering objective (average within-cluster distance). It visualizes how the fairness and accuracy of these algorithms vary as the number of clusters (k) changes. The results are based on the Census Income dataset, illustrating the relative performance of these algorithms in terms of both fairness guarantees and standard clustering quality.

This figure presents the results of comparing GREEDYCAPTURE, k-means++, and k-medoids clustering algorithms on the Census Income dataset. It shows the core and FJR violations for both average and maximum loss functions across varying numbers of clusters (k). Additionally, it displays the average within-cluster distance, k-means objective, and k-medoids objective, to assess the trade-off between fairness and standard clustering performance metrics. The results demonstrate that GREEDYCAPTURE achieves significantly better fairness guarantees compared to the other algorithms, with a modest compromise on traditional clustering objectives.

The figure presents a comparison of four fairness metrics (core violation, average loss; FJR violation, average loss; core violation, maximum loss; FJR violation, maximum loss) and one accuracy metric (average within-cluster distance) across three clustering algorithms (Greedy Capture, k-means++, k-medoids). The x-axis represents the number of clusters (k), and the y-axis represents the value of each metric. The results show that Greedy Capture consistently outperforms k-means++ and k-medoids in terms of fairness, while incurring only a modest loss in terms of accuracy.

Full paper#