↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fairly allocating indivisible goods among self-interested agents is a long-standing challenge. Existing truthful mechanisms offer poor approximations, especially when dealing with private valuations. The Maximin Share (MMS) value, representing the minimum value an agent can guarantee themselves, serves as a fairness benchmark. However, achieving both truthfulness and good MMS approximation is computationally hard, especially with private valuations.

This paper introduces the Plant-and-Steal framework, a learning-augmented approach that uses predictions to improve truthful MMS allocation. For two agents, this method provides a 2-approximation with accurate predictions and a near-optimal approximation even with errors. The framework’s performance gracefully degrades with prediction errors, interpolating between the best-case and worst-case scenarios. The approach also extends to multiple agents, achieving a 2-approximation under accurate predictions while guaranteeing relaxed fallback robustness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in fair allocation and mechanism design. It bridges the gap between theoretical results with public information and incentive-compatible algorithms with private information, opening avenues for designing truthful mechanisms using predictions in various application scenarios. The learning-augmented framework presented offers a new paradigm for tackling the inherent difficulties in achieving both fairness and truthfulness simultaneously.

Visual Insights#

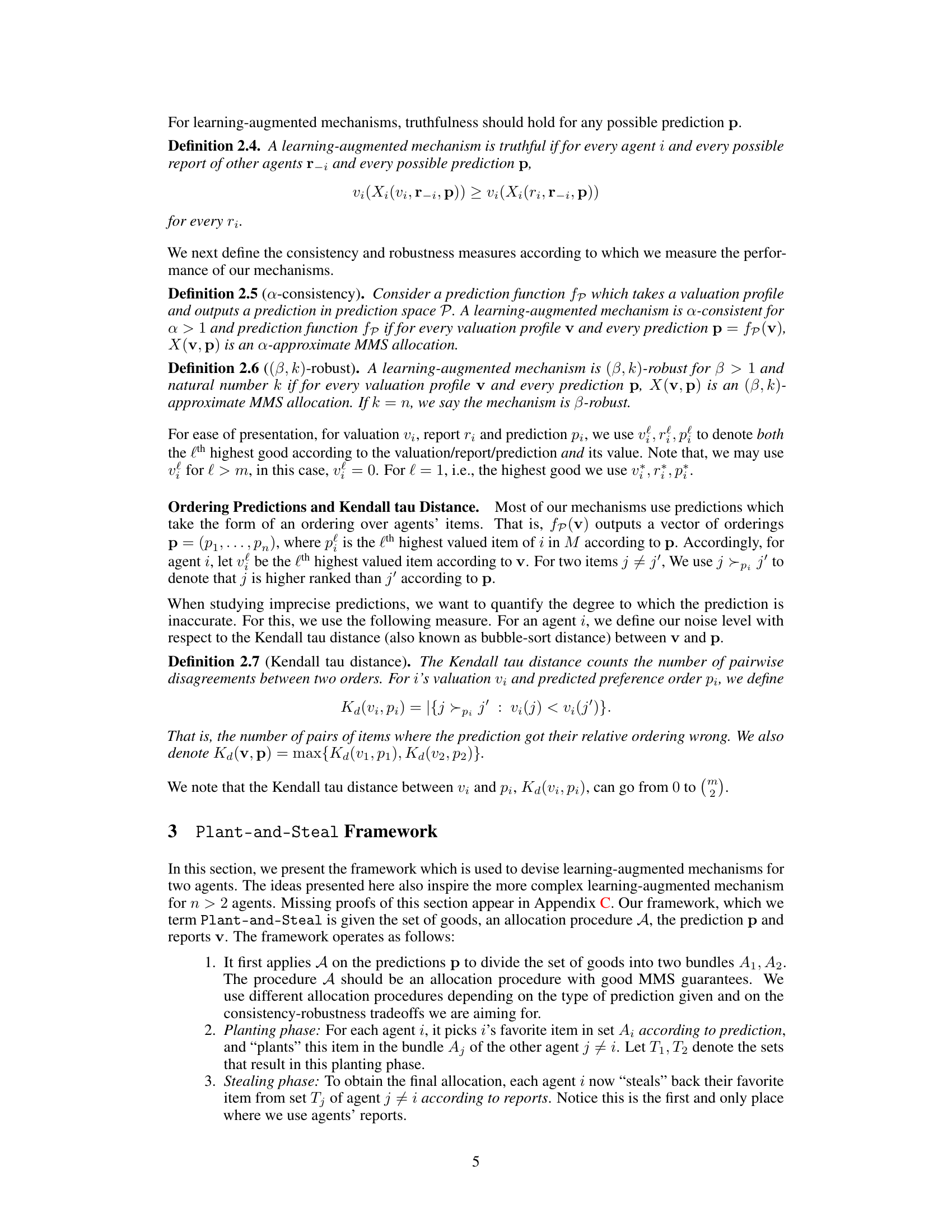

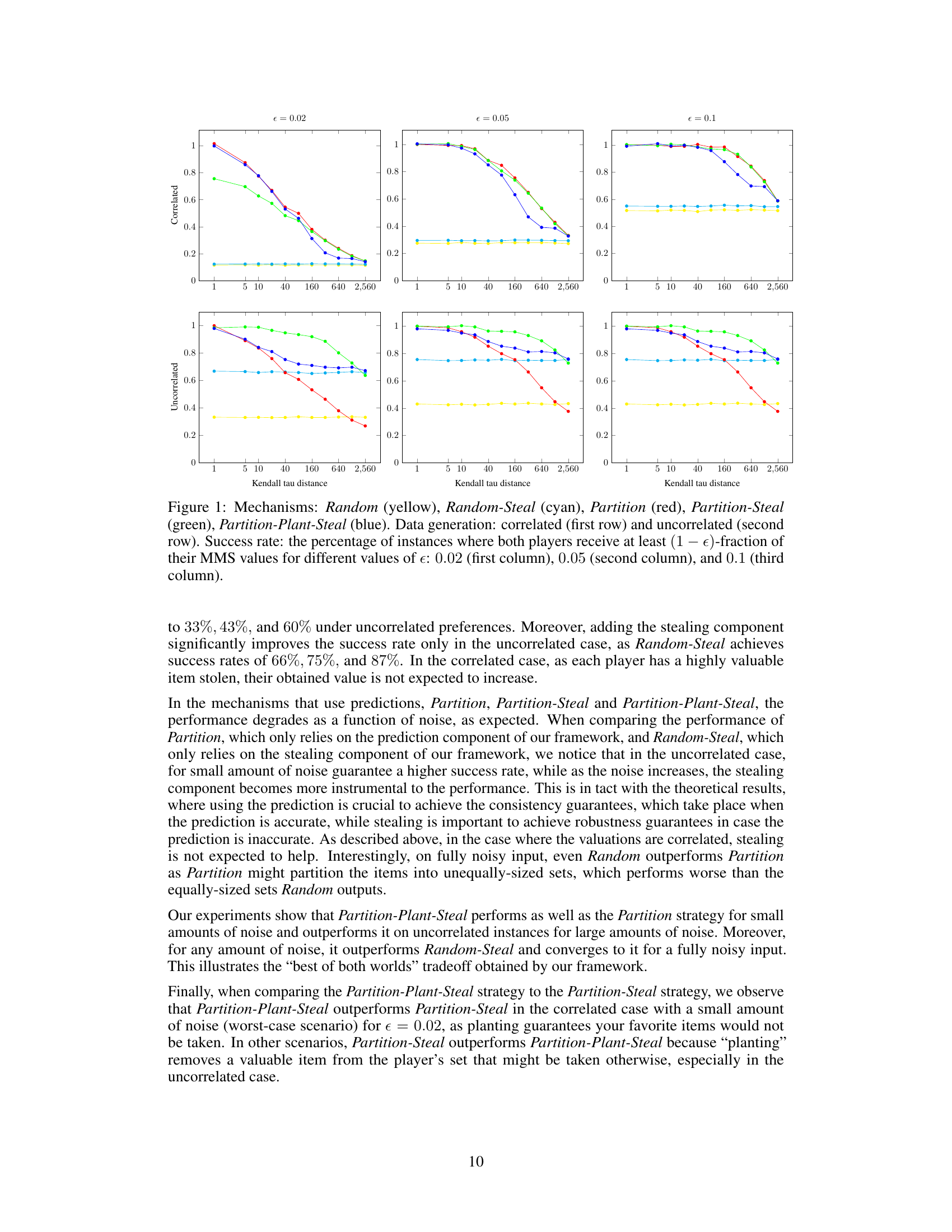

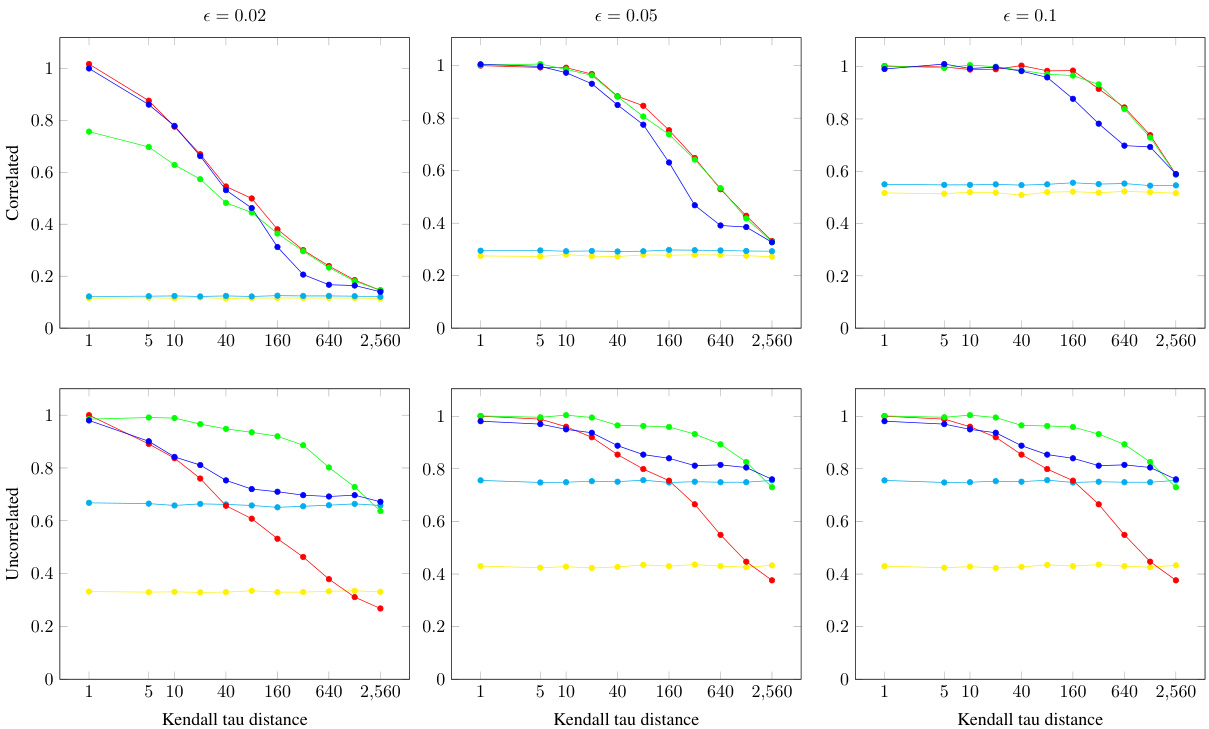

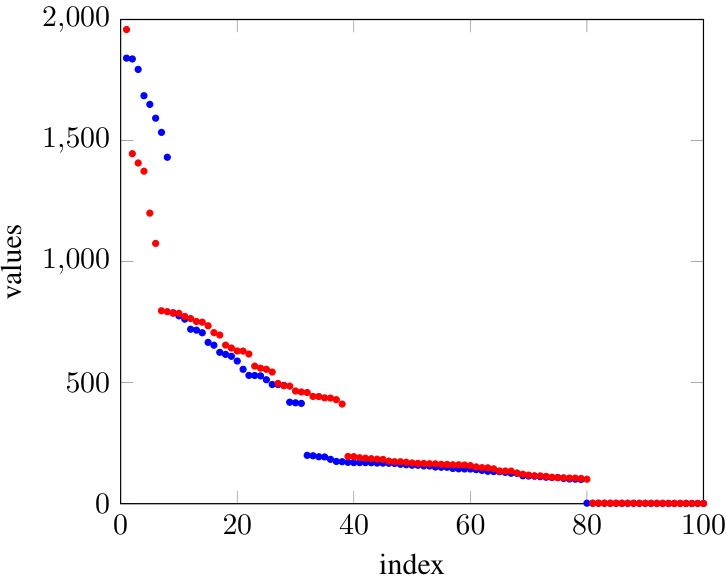

This figure compares the performance of five different mechanisms for two-player fair allocation problems under correlated and uncorrelated data, for different noise levels. Each mechanism employs a different combination of prediction, planting, and stealing strategies. The x-axis represents the Kendall tau distance (a measure of prediction accuracy), and the y-axis shows the success rate (percentage of instances where both players achieve at least (1-ε) of their MMS values) for three different values of ε (error tolerance). The plot shows how the success rates of the mechanisms vary with increasing prediction noise and how the inclusion of prediction and stealing components affects the robustness and consistency of these algorithms under different noise levels.

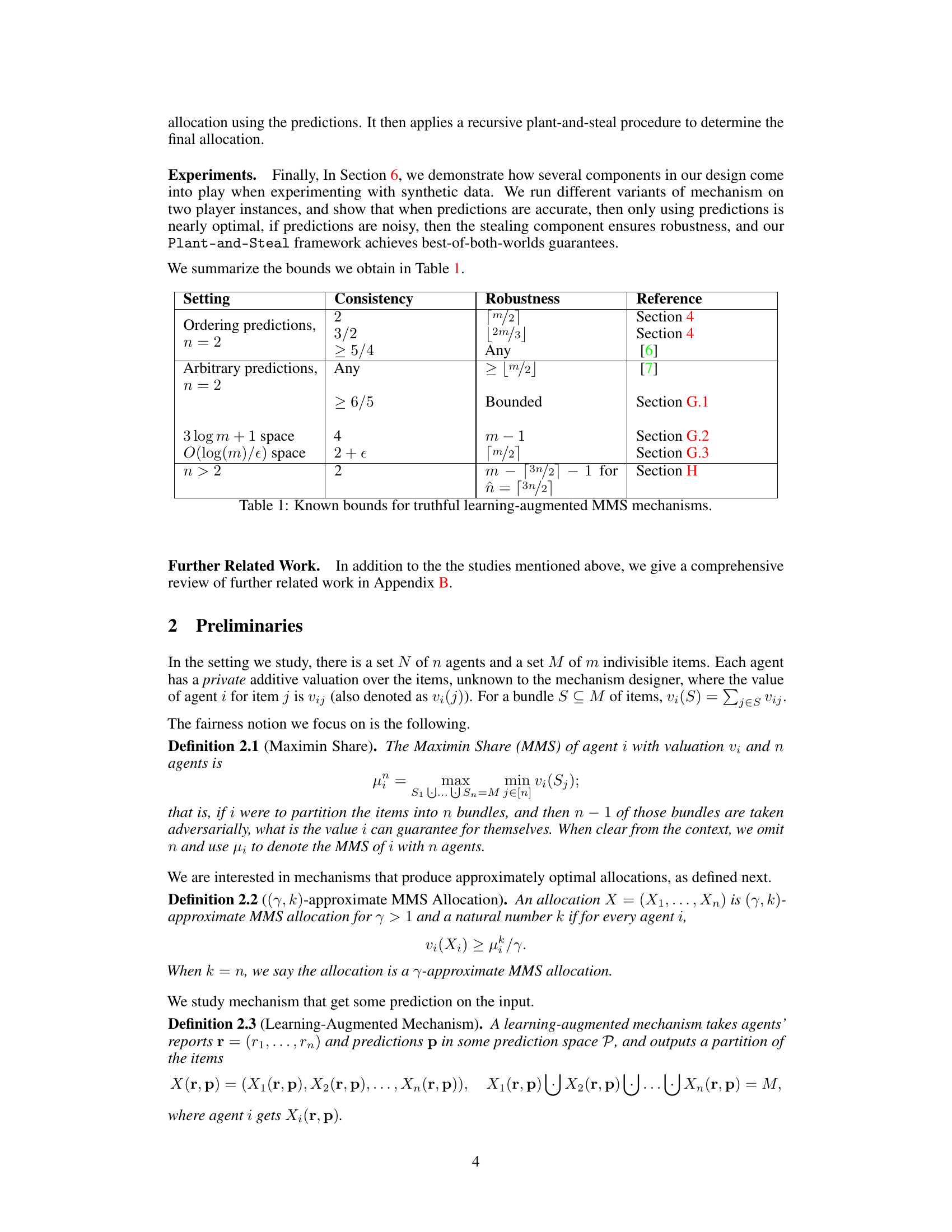

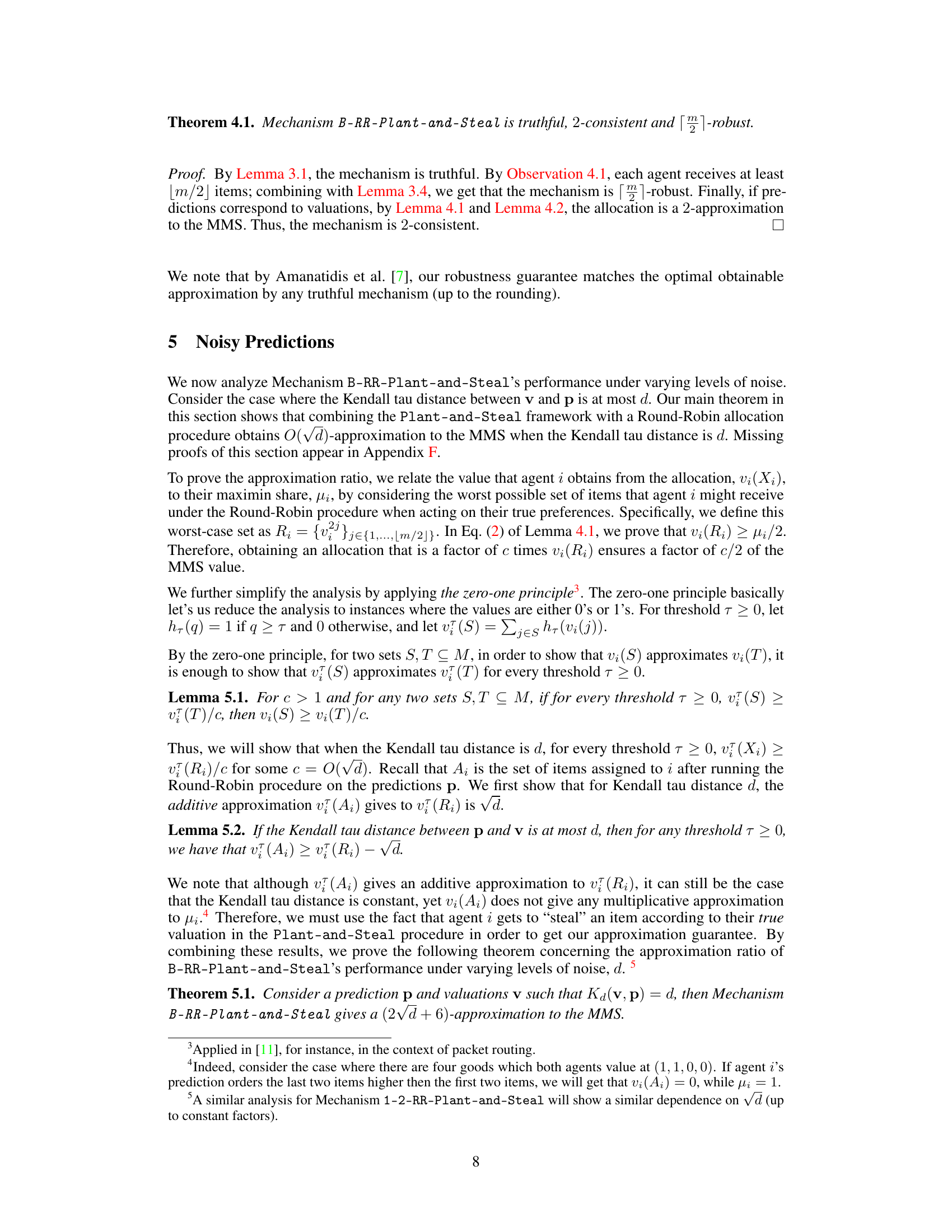

This table summarizes the known bounds for truthful learning-augmented MMS mechanisms, showing the consistency and robustness guarantees achieved under different settings. Consistency refers to the approximation ratio achieved when predictions are accurate, while robustness indicates the approximation ratio when predictions are inaccurate. The table considers various prediction types (ordering predictions, arbitrary predictions) and prediction space sizes (3 log m + 1 space, O(log m/ε) space) for both the two-agent (n=2) and general (n>2) cases. It also provides references to sections in the paper where each result is discussed.

In-depth insights#

Truthful Fair Division#

Truthful fair division mechanisms are crucial for resource allocation scenarios where agents have private valuations and incentives to misreport. The challenge lies in designing mechanisms that both incentivize truthful reporting (truthfulness) and guarantee fair outcomes (fairness). Approximating the maximin share (MMS) value is a common approach to defining fairness, but achieving both truthfulness and a good MMS approximation is computationally hard. Research in this area focuses on developing mechanisms that provide approximate MMS allocations while maintaining truthfulness, often exploring the tradeoff between the quality of approximation and the robustness of the mechanism to inaccurate predictions or noisy inputs. Learning-augmented mechanisms, which incorporate predictions about agent valuations, show promise in improving both truthfulness and approximation guarantees. The core of these mechanisms is often a combination of a prediction component to handle the computational complexity and an incentive-compatible allocation component to enforce truthfulness. However, designing these mechanisms requires careful consideration of the trade-off between consistency (performance with accurate predictions) and robustness (performance with inaccurate predictions). Many studies investigate the theoretical limits of truthfulness and approximation in fair division, often demonstrating impossibility results under certain conditions, highlighting the importance of finding practically feasible mechanisms.

MMS Approximation#

The concept of Maximin Share (MMS) approximation is central to fair division problems, aiming to guarantee each agent a certain minimum share of the goods. Approximating the MMS is challenging due to the inherent complexity of ensuring fairness among agents with diverse valuations for indivisible items. The research explores various algorithmic approaches to find allocations that provide a good approximation of the MMS value. Truthfulness is another key consideration; agents may strategically misreport their preferences. Therefore, the research investigates mechanisms that incentivize truthful reporting while still providing a reasonable MMS approximation. Learning-augmented approaches, where algorithms leverage predictions about agents’ preferences, are explored to improve the efficiency and accuracy of the MMS approximation. This involves striking a balance between consistency (high accuracy when predictions are correct) and robustness (acceptable performance when predictions are inaccurate). Overall, the research highlights the trade-offs between algorithmic guarantees, incentive compatibility, and the use of prediction, creating a framework for evaluating different fairness mechanisms.

Learning-Augmented#

The concept of ‘Learning-Augmented’ mechanisms in the context of fair allocation is a significant contribution to the field. It bridges the gap between theoretical optimality and practical implementation by incorporating predictive models. Instead of relying solely on agents’ declared valuations (which can be manipulated), these mechanisms use external predictions to inform the allocation process. This leads to improved fairness guarantees, especially when predictions are accurate. The strength of this approach lies in its robustness, as it can still provide reasonable fairness even when predictions are imperfect or noisy. The framework provides mechanisms with guaranteed consistency (good performance with accurate predictions) and robustness (acceptable performance with inaccurate predictions), thus making the approach more practical. The framework’s modularity allows flexibility in choosing components to trade off consistency and robustness, catering to various application needs and prediction qualities. This approach could prove to be particularly useful in settings with limited computational resources or where perfect valuation information is unavailable.

Plant-and-Steal#

The proposed mechanism, Plant-and-Steal, cleverly addresses the challenge of achieving truthful and approximately fair allocations of indivisible goods. Its modular design allows for flexibility in prediction accuracy, using an initial allocation phase (planting) guided by predictions, followed by a stealing phase incorporating agent reports to ensure robustness. The framework’s strength lies in its graceful degradation in performance as prediction accuracy varies, interpolating between optimal consistency and near-optimal robustness. The mechanism’s truthfulness is a crucial feature, ensuring agents truthfully report preferences. By combining predictions with strategic stealing, Plant-and-Steal offers a practical solution for approximating the maximin share value, especially valuable in scenarios with imperfect prediction of agent preferences.

Empirical Evaluation#

An Empirical Evaluation section in a research paper would typically present experimental results to validate the claims made. A thoughtful analysis would examine the design of the experiments, including the metrics used, the choice of datasets, and the experimental setup. It would also scrutinize the statistical significance of the results, considering whether error bars or p-values were reported and whether they support the conclusions drawn. Moreover, a comprehensive evaluation should assess the reproducibility of the results by evaluating whether enough information is provided to replicate the study. Finally, discussion about the limitations of the experiments, such as dataset biases or generalizability, is important for a complete and nuanced assessment of the paper’s findings. Strengths might include a rigorous methodology, diverse datasets, and clear presentation of results. Weaknesses, on the other hand, might encompass limited scope, insufficient controls, or uninterpretable results. Overall, the quality of the empirical evaluation significantly influences the credibility and impact of the research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the success rate of five different mechanisms (Random, Random-Steal, Partition, Partition-Steal, and Partition-Plant-Steal) in achieving approximate maximin share (MMS) allocations for two players. The success rate is defined as the percentage of instances where both players receive at least (1-ε) of their MMS value for different values of ε (0.02, 0.05, and 0.1). The data is generated under two conditions: correlated preferences (where both players have similar rankings of items) and uncorrelated preferences (where preferences are randomly generated). The figure illustrates how the different mechanisms perform under various levels of noise in the predictions and the relative importance of the different components of the proposed Plant-and-Steal framework.

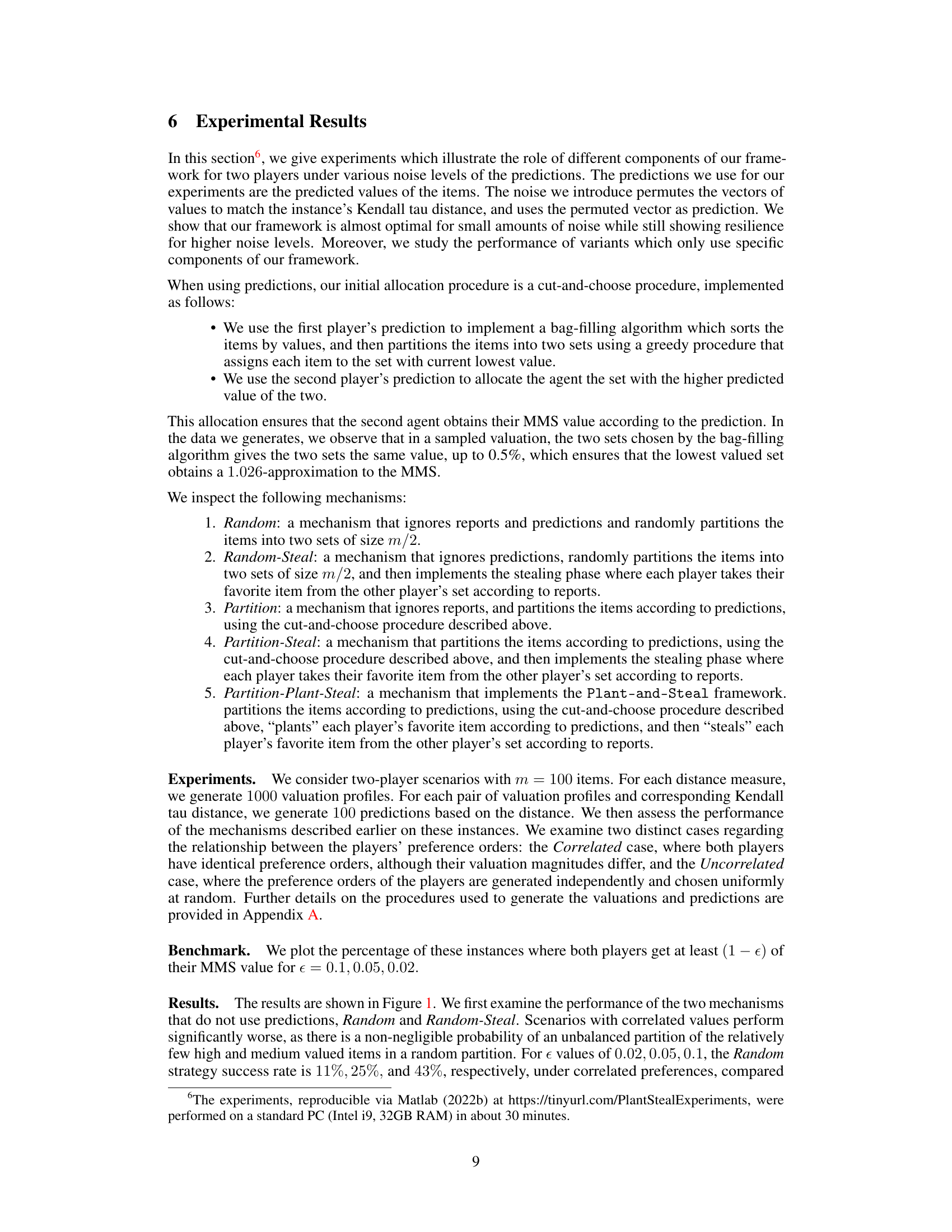

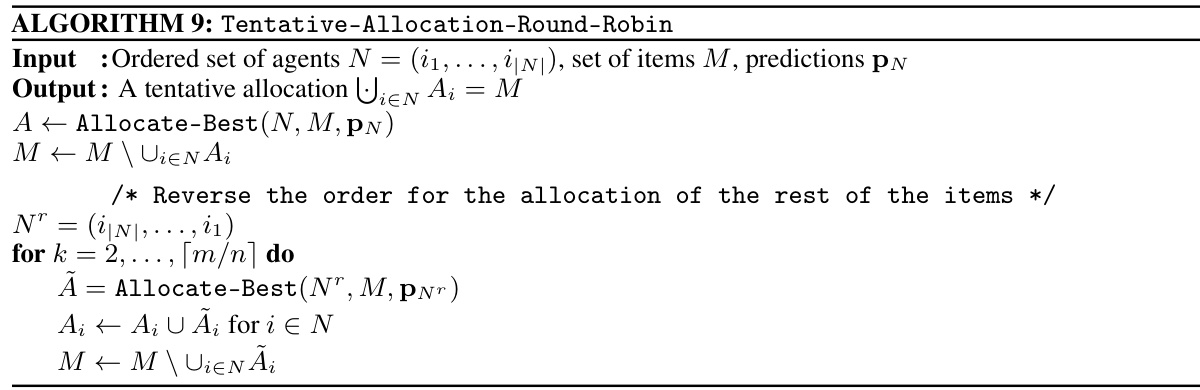

This figure illustrates a single round of the recursive planting and stealing phase of Algorithm 10 from the paper. It shows how, given accurate predictions, agents initially plant their highest-valued predicted items into the tentative allocation of the opposite group. Subsequently, a stealing phase occurs, where each agent selects their highest-valued remaining item (according to their true valuations), resulting in a partial allocation. The process repeats recursively until a final allocation is reached.

More on tables

This table summarizes the known bounds for truthful learning-augmented MMS mechanisms, categorized by the type of predictions used (ordering predictions, arbitrary predictions, and predictions using limited space), the number of agents (n=2 or n>2), and the achieved consistency and robustness guarantees. It shows the trade-offs between consistency (performance with accurate predictions) and robustness (performance with inaccurate predictions). The reference column indicates the section of the paper where each result is presented.

This table summarizes the known bounds for truthful learning-augmented MMS mechanisms, comparing consistency and robustness results for different prediction types (ordering predictions, arbitrary predictions, and predictions using limited space) and number of agents (n=2 and n>2). It provides a concise overview of the performance guarantees obtained in various parts of the paper. The ‘Consistency’ column represents the approximation ratio achieved when predictions are accurate, and the ‘Robustness’ column indicates the approximation ratio when predictions are inaccurate. Reference sections of the paper are included for further detail.

The table summarizes the known bounds for truthful learning-augmented MMS mechanisms, categorized by the type of predictions used (ordering predictions, arbitrary predictions, and space-constrained predictions), the number of agents (n=2 and n>2), and the achieved consistency and robustness guarantees. It provides a reference to the section in the paper where each result is discussed.

This table summarizes the known bounds for truthful learning-augmented MMS mechanisms, showing the consistency and robustness guarantees achieved by different mechanisms under various prediction settings (ordering predictions, arbitrary predictions, and limited-space predictions). The table also references the sections of the paper where the results are presented.

This table summarizes the known bounds for truthful learning-augmented MMS mechanisms, comparing consistency and robustness guarantees for different prediction settings (ordering predictions, arbitrary predictions, and space-limited predictions) and number of agents (n=2 and n>2). It shows the trade-offs between consistency (performance when predictions are accurate) and robustness (performance when predictions are inaccurate) achievable by truthful mechanisms in different scenarios. The reference column indicates the section of the paper where the corresponding result is presented.

Full paper#