↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world datasets exhibit inherent symmetries, which can be leveraged to create more efficient and accurate models. However, most existing approaches either require prior knowledge of these symmetries or focus on discriminative settings. This limits their applicability and potential for data-efficient learning. This paper addresses these limitations.

This paper introduces a novel Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) that learns data symmetries directly from the dataset in a generative setting. The model cleverly separates the latent representation into invariant and equivariant components, allowing it to disentangle symmetries from other latent factors. The proposed two-stage learning algorithm first learns the invariant component using a self-supervised method and then estimates the equivariant component. Experiments demonstrate that the SGM successfully captures symmetries under affine and color transformations, leading to better test-log-likelihoods and significantly improved data efficiency compared to standard generative models like VAEs. The SGM provides a robust and interpretable method for data augmentation. The approach offers significant advantages in terms of efficiency and performance, making it a valuable tool for various applications where data augmentation is critical.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on generative models and data augmentation. It introduces a novel approach to incorporate symmetries directly from data, leading to more efficient and robust models with improved data efficiency and higher test log-likelihoods. This opens up exciting avenues for further research in various domains.

Visual Insights#

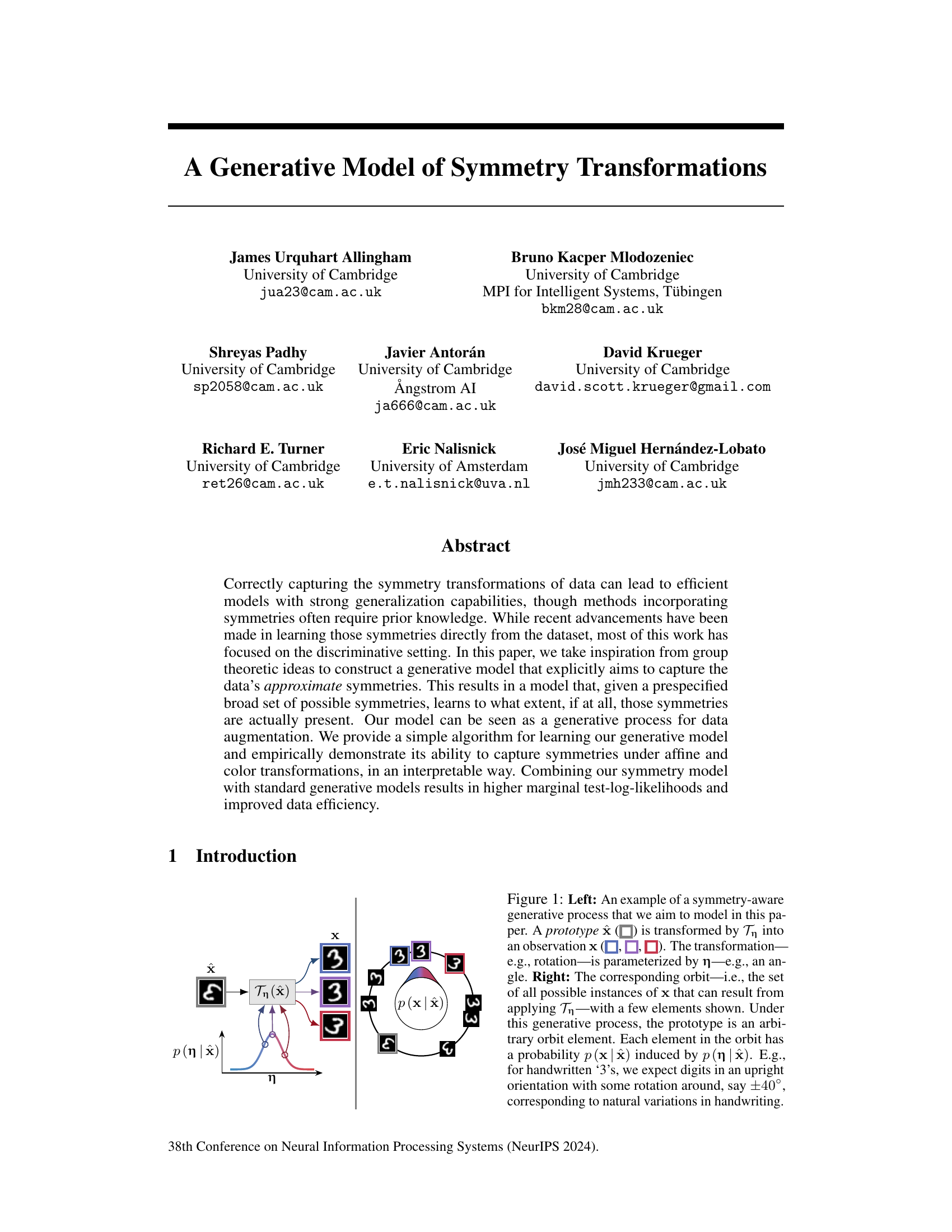

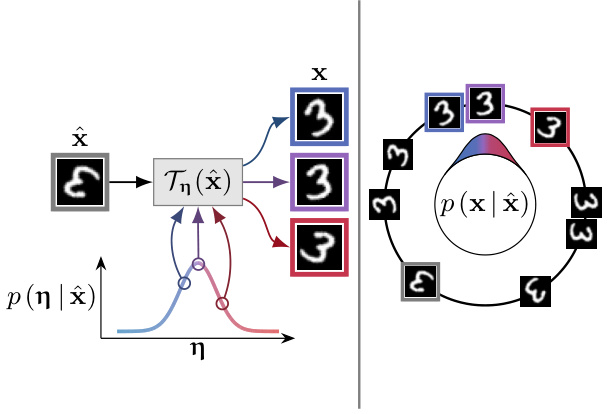

This figure illustrates the symmetry-aware generative model proposed in the paper. The left panel shows a generative process where a prototype x is transformed by a parameterized transformation Tη (where η represents parameters like rotation angle) to produce an observation x. The right panel shows the resulting orbit, which is the set of all possible transformed versions of x. The model learns to what extent these transformations are present in the data, offering a framework for data augmentation.

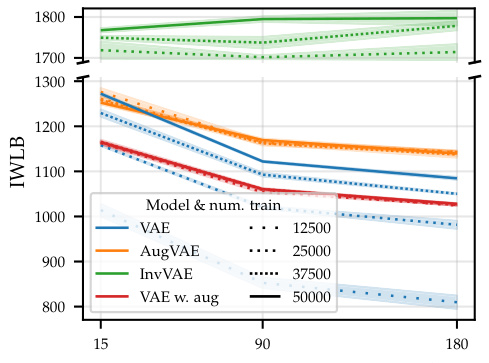

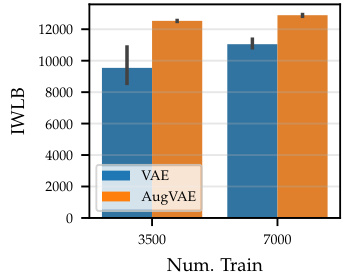

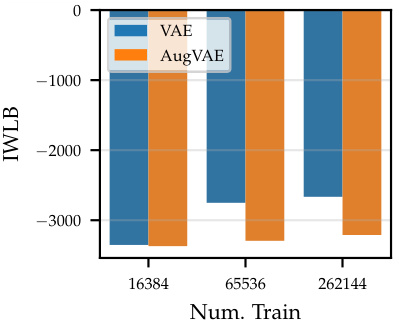

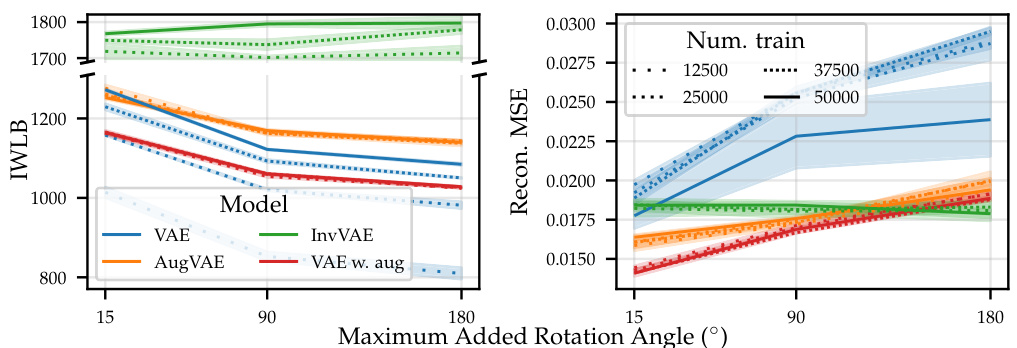

This figure compares the performance of four different models on the rotated MNIST dataset: a standard VAE, a VAE with data augmentation, AugVAE (a VAE that uses the proposed Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) to resample transformed examples), and InvVAE (a VAE that uses the SGM to convert each example to its prototype). The models are evaluated across different amounts of training data and varying degrees of added rotation. The results show that AugVAE demonstrates improved data efficiency, showing little performance degradation when training data is reduced or the amount of added rotation is increased, unlike the standard VAE. InvVAE achieves even higher likelihoods, showing high robustness to both data reduction and added rotation. The results highlight the benefits of incorporating symmetries into generative models for improved efficiency and robustness.

In-depth insights#

Symmetry Modeling#

Symmetry modeling in machine learning aims to incorporate prior knowledge or learn directly from data about inherent symmetries within datasets. This approach offers potential benefits including improved generalization, data efficiency, and interpretability. However, challenges remain in identifying symmetries, handling partially symmetric data, and extending these methods to diverse types of symmetries beyond those easily represented by group theory. Generative models provide a particularly interesting avenue for symmetry modeling, offering advantages in capturing the distribution over natural transformations and improving data augmentation techniques. Self-supervised learning can aid in learning the symmetries directly from data. However, complexities can arise when transformations are not fully invertible in the data space. Future research could explore more robust and efficient methods, especially for high-dimensional or complex datasets, focusing on effectively handling partial symmetries and incorporating broader classes of transformations. The development of methods that automatically discover or learn useful representations of symmetries, rather than relying on predefined transformation groups, would represent significant progress.

Generative SGM#

The concept of a Generative Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) presents a novel approach to incorporating symmetries into generative models. The core idea is to disentangle the invariant features of data (prototype, x) from its symmetry transformations (η). This disentanglement allows for a more efficient and interpretable representation of the data, as symmetries are explicitly modeled rather than implicitly learned. The model’s latent space is structured such that x captures only invariant information while η encapsulates the transformations applied to x to generate observations. The model learns the distribution of natural transformations, P(η|x), allowing for data augmentation by sampling from this distribution. This approach offers several advantages: increased data efficiency by learning compact symmetry representations, enhanced model generalization due to explicit symmetry incorporation, and interpretability through the clear separation of prototype and transformation. A two-stage learning algorithm is proposed: first, self-supervised learning of the prototype inference function and then, maximum likelihood estimation of the transformation distribution. While the model demonstrates promising results in experiments, limitations exist such as the need for a pre-specified set of possible symmetries and potential sensitivity to data characteristics. Future work could address these limitations and explore the broader implications of SGMs for various applications.

VAE-SGM Hybrid#

The VAE-SGM hybrid model cleverly integrates a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) with a Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM). This combination leverages the VAE’s ability to learn complex data distributions while incorporating the SGM’s strength in capturing data symmetries. The result is a model that is more data-efficient, achieving higher marginal log-likelihoods even with reduced datasets. This is a significant improvement over a standard VAE, demonstrating the effectiveness of explicitly modeling symmetries within the generative process. The hybrid model’s robustness is highlighted by its resilience to data deletion, outperforming standard VAEs when faced with missing data. Furthermore, the interpretability of the SGM component aids in understanding the learned symmetries, offering insights into the underlying data structure. Combining the power of VAEs with symmetry modeling creates a robust and efficient framework for generative modeling. The success of this hybrid model underscores the value of incorporating prior knowledge of symmetries into generative models to enhance learning performance and robustness.

Data Efficiency#

The concept of ‘data efficiency’ is central to the paper, focusing on how incorporating symmetry transformations into generative models can reduce the amount of training data needed to achieve high performance. The authors demonstrate that their Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) leads to improved data efficiency compared to standard Variational Autoencoders (VAEs). This is shown through experiments on various datasets where the SGM-enhanced VAE outperforms the standard VAE, particularly when training data is limited or when dealing with transformations such as rotations or color changes. The interpretability of the SGM is highlighted as a key benefit, enabling the model to learn the extent to which various symmetries are present. This allows for robustness to data variations, even demonstrating resilience when a significant portion of the dataset is removed. However, the paper acknowledges limitations, specifically mentioning the need to pre-specify a range of possible symmetries and the potential challenges posed by real-world data with imperfect or complex transformations.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore relaxing the requirement of specifying a complete set of possible symmetries, perhaps by learning a more flexible representation of the symmetry space directly from the data. Investigating the robustness of the model to larger and more complex datasets is crucial. Further work could also focus on developing more efficient inference algorithms to handle high-dimensional data and more computationally intensive transformations. The applicability of the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) to various domains beyond image data, including scientific data analysis, warrants further exploration. Investigating the potential for scientific discovery by identifying underlying symmetries in data represents a promising avenue for future work. Combining the SGM with other advanced generative models, like diffusion models, may also lead to significant improvements in data efficiency and sample quality. Finally, the development of theoretically grounded methods for evaluating and comparing different symmetry-aware models remains an important challenge.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the self-supervised learning process used to make the transformation inference function fw(x) equivariant. Two inputs are processed: the original sample x, and a randomly transformed version x̃rnd. Both are passed through the function fw(x), which outputs transformation parameters that are then used to map the samples to prototypes. A mean squared error (MSE) loss encourages consistency, making the function equivariant to transformations.

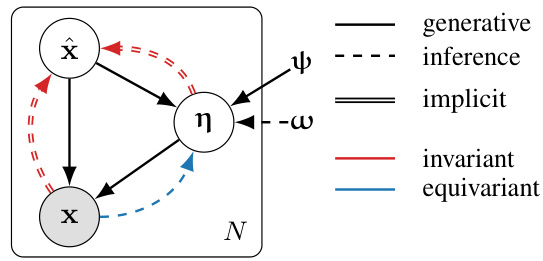

This figure shows a graphical model representation of the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM). The model has three latent variables: x (prototype), η (equivariant component capturing symmetries), and x (observation). The model shows how the prototype x and the transformation parameters η combine to produce the observed data point x. The arrows indicate the direction of the generative process, while dashed lines represent inference steps. The model is designed such that the prototype x is invariant to transformations, while η is equivariant to them.

This figure illustrates the symmetry-aware generative model proposed in the paper. The left panel shows a generative process where a prototype ‘3’ is transformed (e.g., rotated) by a parameter η to produce an observed ‘3’. The right panel displays the set of all possible transformations of the prototype (its orbit). The model aims to learn the distribution of these transformations from data, enabling efficient data augmentation and improved model generalization.

The figure shows an example of symmetry-aware generative process. On the left, a prototype is transformed into an observation via a transformation parameterized by η. On the right, the figure shows the corresponding orbit, which is the set of all possible instances of x that can be produced by applying the transformation. The model assumes each observation is generated by applying a transformation to a latent prototype. The prototype itself is invariant to the transformation, capturing only non-symmetric properties of the data.

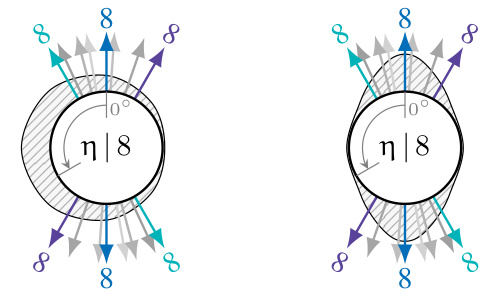

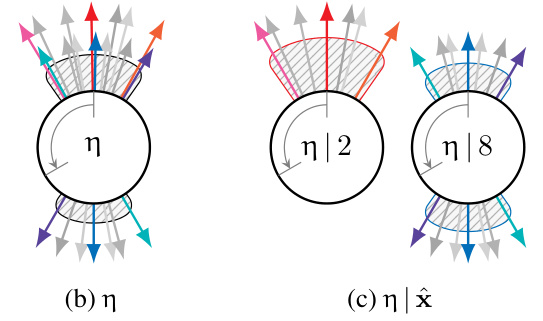

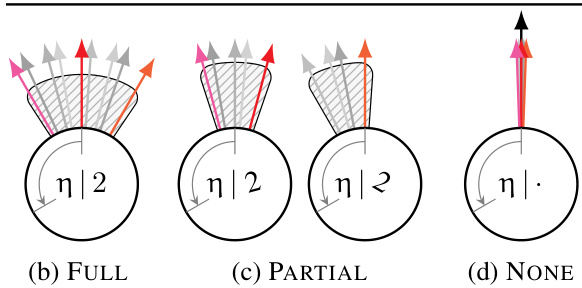

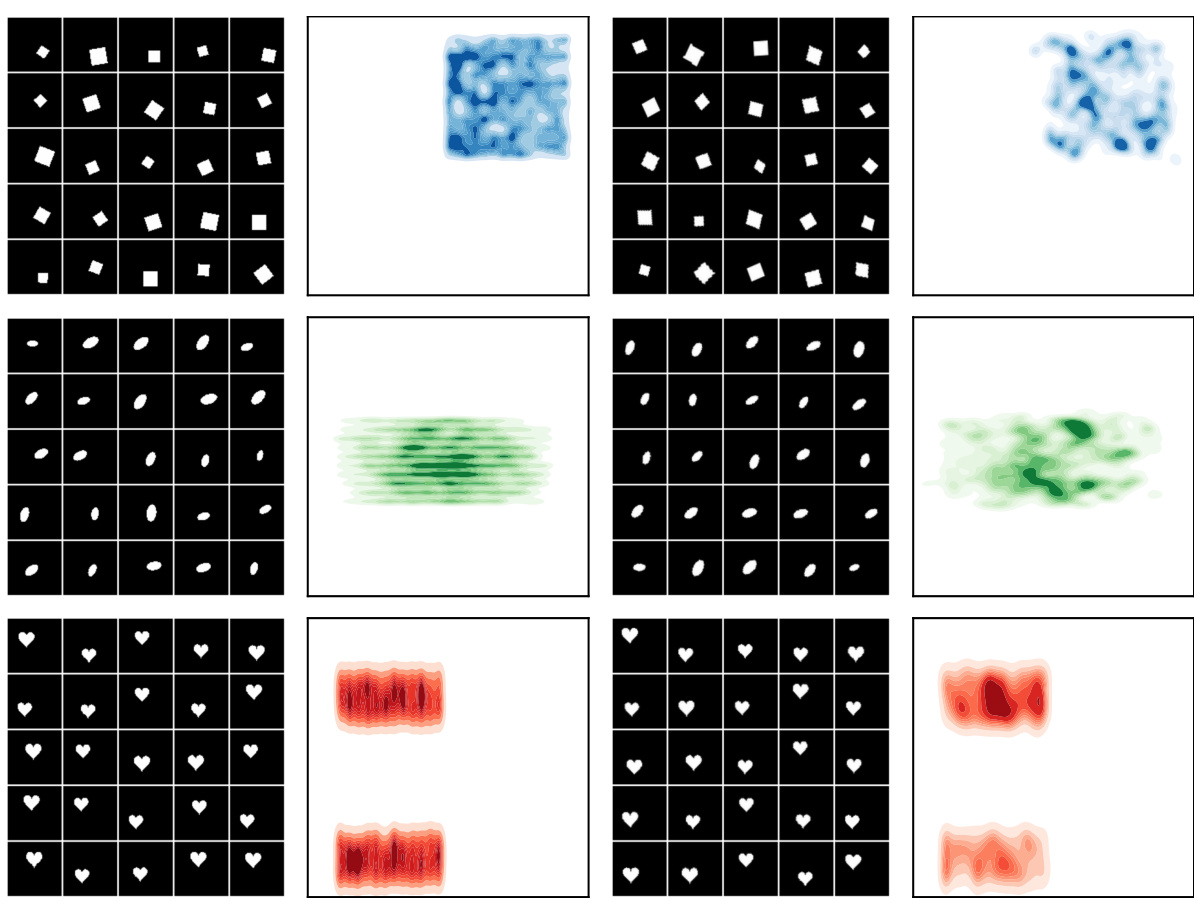

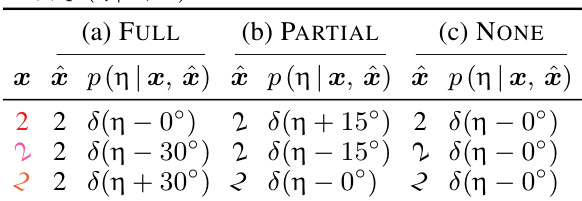

This figure illustrates different scenarios of learned distributions over transformation parameters (η) given a prototype (x) in the context of symmetry-aware generative models. The scenarios are: (a) FULL invariance: A single prototype represents all transformed versions of a data point. (b) PARTIAL invariance: A few prototypes represent transformed versions, reflecting some level of invariance. (c) NONE: Each transformed version has a unique prototype, indicating no learned invariance. The figure showcases how the model’s ability to capture symmetries is reflected in the distribution pψ(η|x), demonstrating varying levels of invariance.

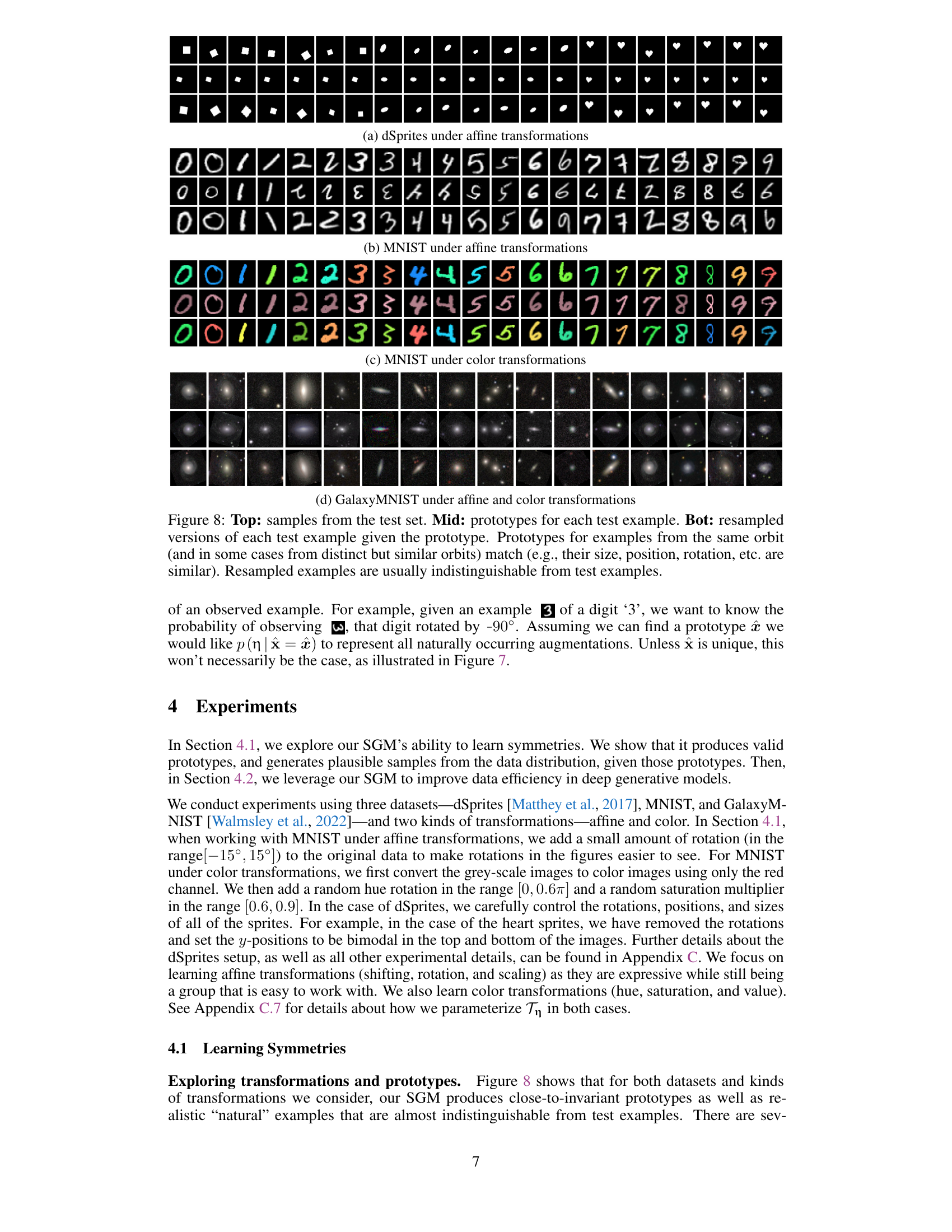

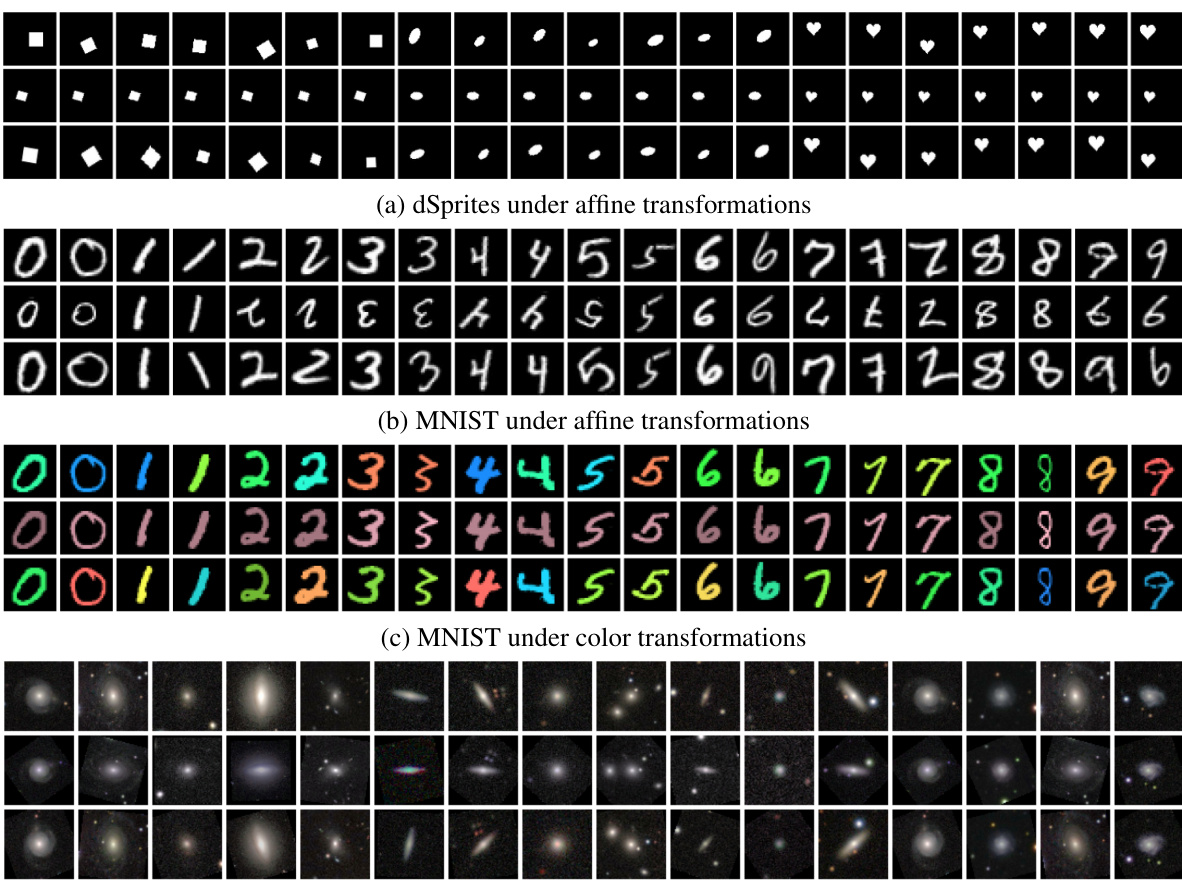

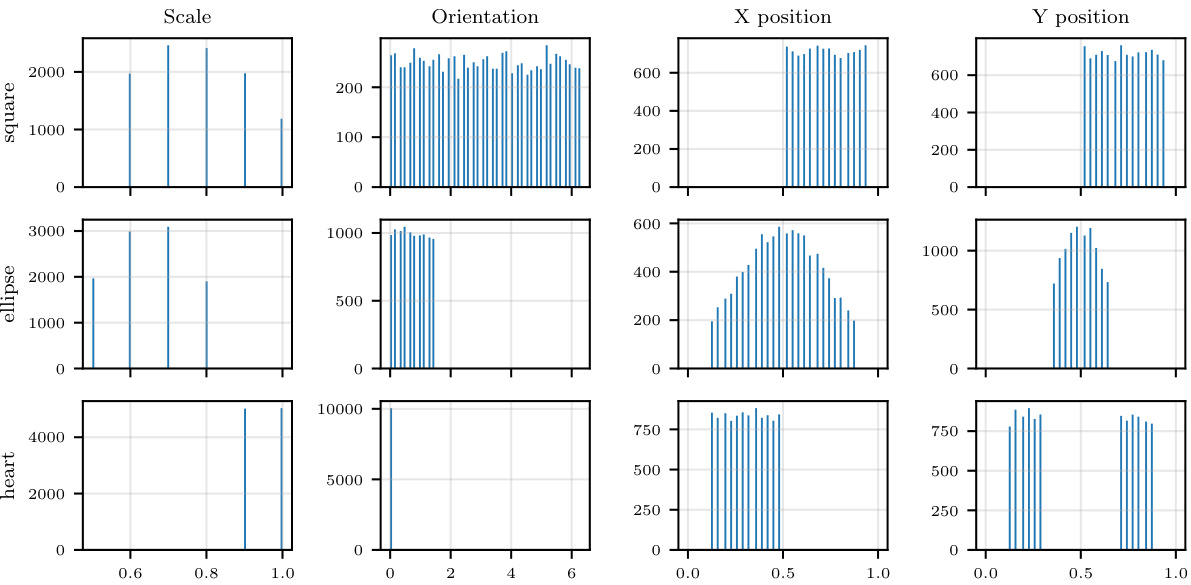

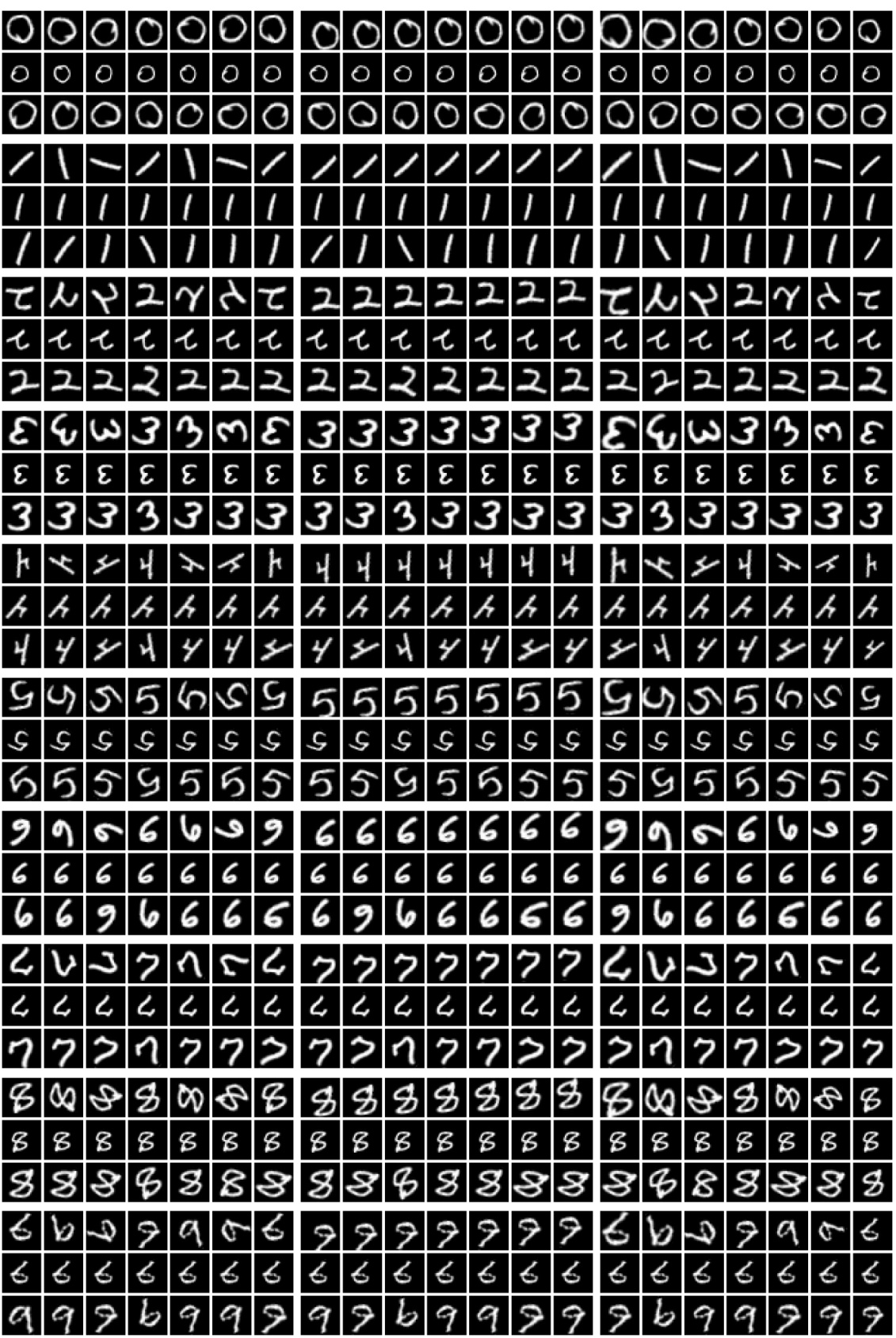

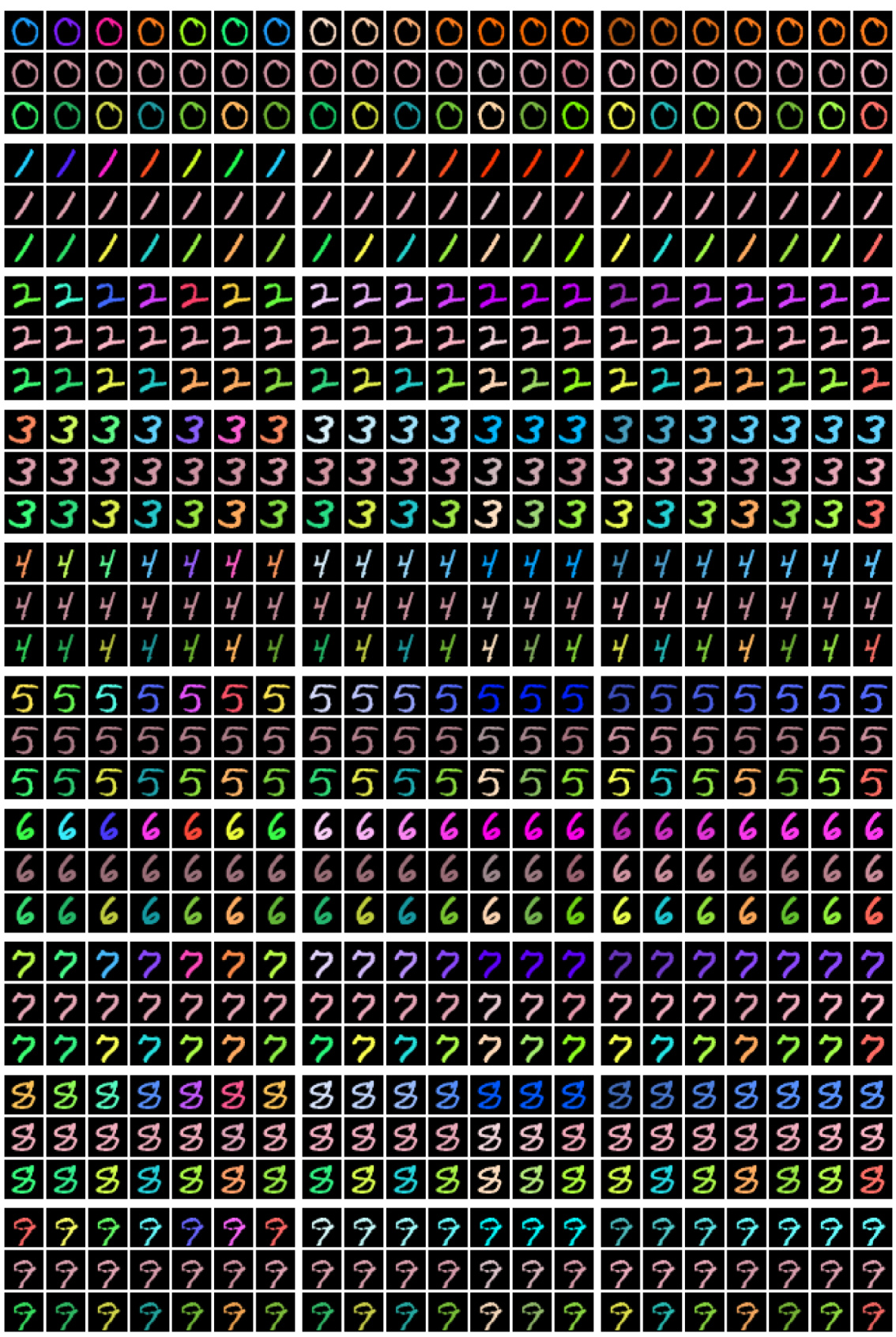

This figure shows the results of applying the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) to four different datasets: dSprites, MNIST (under affine transformations), MNIST (under color transformations), and GalaxyMNIST. The top row displays samples from the test set. The middle row displays the learned prototypes for each test example. The bottom row shows resampled versions of the test examples, generated by applying learned transformations to their corresponding prototypes. The figure demonstrates that the SGM effectively learns prototypes that capture the underlying symmetries present in the data, producing resampled examples nearly indistinguishable from the originals.

This figure shows examples of prototypes and resampled examples generated by the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) on four datasets under affine and color transformations. The top row displays original samples from the test set. The middle row shows the corresponding prototypes learned by the model. The bottom row displays new examples generated by applying learned transformations to the prototype. The results demonstrate that the SGM successfully learns to capture the symmetries in the data by producing prototypes that are nearly invariant to transformations, and by generating new examples that are almost indistinguishable from the originals.

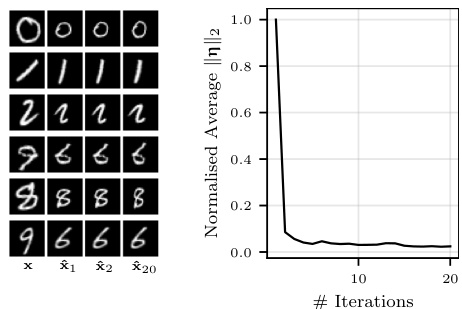

This figure shows the results of an iterative prototype inference process. Starting with a test example, the model infers a prototype. Then, treating this prototype as a new observation, the model infers another prototype and so on. The left panel shows several examples of this process. The right panel displays the average magnitude of the inferred transformation parameters across iterations. This shows how much the prototypes change across the iterations, demonstrating the model’s ability to find an invariant representation. The relatively small magnitude after a few iterations confirms the model’s tendency toward invariant representations.

This figure compares the performance of four different models on the rotated MNIST dataset: a standard VAE, a VAE with standard data augmentation, AugVAE (VAE with our SGM for data augmentation), and InvVAE (VAE with our SGM using only the invariant representation). The models are trained with different amounts of training data (12500, 25000, 37500, and 50000) and different amounts of added rotation (15°, 90°, and 180°). The y-axis shows the IWLB, a metric that measures the performance of a generative model. The figure demonstrates that AugVAE and InvVAE are more data-efficient than the standard VAE, particularly when there is less training data or more rotation. InvVAE shows the best performance in almost every scenario, highlighting the advantages of incorporating the symmetry information directly into the model.

This figure compares the performance of a standard Variational Autoencoder (VAE) model with two variations incorporating the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) proposed in the paper. The variations are AugVAE (data augmentation with SGM) and InvVAE (invariant representation with SGM). The comparison is made across varying amounts of training data and different levels of added rotation to the MNIST digits. The results show that incorporating the SGM improves data efficiency, especially in scenarios with limited training data or increased rotation.

This figure illustrates the core idea of the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM). The left panel shows a generative process where a prototype ‘3’ is transformed by a rotation parameter η (angle) to generate an observed digit. The right panel shows the orbit, which is the set of all possible transformations of the prototype. The probability of each transformed digit is determined by the probability distribution of η given the prototype.

This figure compares the learned augmentation distributions for MNIST data rotated in the range [-45°, 45°] using the proposed SGM and LieGAN. The SGM accurately captures the ranges of rotational invariance, while LieGAN fails to precisely recover these ranges, especially for translations, highlighting the SGM’s superior ability to learn and represent dataset-specific symmetries.

This figure compares the performance of four different models on rotated MNIST dataset: a standard VAE, a VAE with data augmentation, a VAE using the proposed SGM for data augmentation (AugVAE), and a VAE using the SGM to convert each example to its prototype before feeding into VAE (InvVAE). The performance is measured by the importance-weighted lower bound (IWLB), and the results are shown for different amounts of training data and different levels of added rotation. The AugVAE model shows improved data efficiency and robustness to added rotations, highlighting the benefits of incorporating symmetry information into generative models.

This figure shows the results of applying the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) to four different datasets: dSprites, MNIST, and GalaxyMNIST. The top row displays samples from the test sets of each dataset. The middle row shows the prototypes generated by the SGM for each of the test examples, demonstrating that the model identifies invariant features despite variations in the original data. The bottom row shows resampled versions of each test example generated from their corresponding prototype. The similarity between the resampled images and the test images visually demonstrates the SGM’s ability to learn and generate examples that capture the symmetries present in the data.

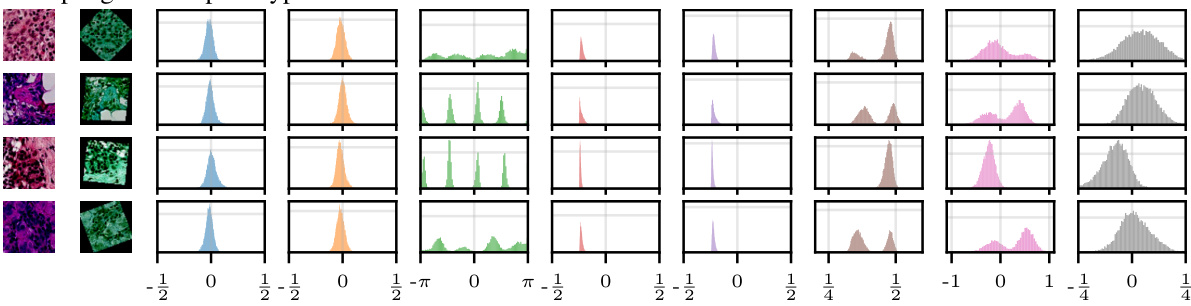

This figure shows the results for the PatchCamelyon dataset. The top row shows samples from the test set. The middle row shows the corresponding prototypes generated by the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM). The bottom row displays the learned distributions over the transformation parameters (translation in x, translation in y, rotation, scaling in x, scaling in y, hue, saturation, and value) for each test example, given its prototype. The figure demonstrates the SGM’s ability to learn the underlying symmetries in the data and generate plausible samples.

This figure shows the results of applying the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) to four different datasets: dSprites, MNIST, and GalaxyMNIST under affine and color transformations. The top row displays samples from the test set. The middle row shows the learned prototypes generated by the SGM for each test example. The bottom row presents resampled versions of each test example, created by the SGM using the learned prototype and applying various transformations. The figure demonstrates that the model learns to generate prototypes that capture the inherent symmetries within the data. Prototypes from the same orbit (meaning they differ only by transformations like rotation or translation) are very similar, and the resampled examples are almost identical to the originals, demonstrating the ability of the SGM to capture and reproduce data symmetries.

This figure shows the results of applying the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) to four different datasets: dSprites, MNIST, and GalaxyMNIST. For each dataset, the top row shows examples from the test set; the middle row shows the prototypes generated by the SGM; and the bottom row shows resampled versions of the test examples, generated by applying transformations to the prototypes. The results demonstrate that the SGM is able to learn the symmetries present in the data and generate realistic samples that are nearly indistinguishable from the original data.

This figure shows the results of applying the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) to three different datasets: dSprites, MNIST, and GalaxyMNIST. The top row displays examples from the test set. The middle row shows the learned prototypes generated by the SGM for each test example. The bottom row shows resampled versions of each test example generated using the corresponding prototype and the learned distribution of transformations. The results demonstrate that the SGM is able to learn accurate and representative prototypes that capture the essential characteristics of the data, generating resampled examples that are very similar to real examples.

This figure shows the results of applying the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) on four different datasets: dSprites, MNIST, and GalaxyMNIST under affine and color transformations. The top row displays samples from the test set. The middle row shows the prototypes generated by the SGM for each test example. The bottom row shows resampled versions of the test examples, generated using the corresponding prototypes. The results demonstrate the SGM’s ability to learn and generate realistic examples that closely resemble the original data, highlighting its capacity to capture underlying symmetries.

This figure shows the results of applying the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) to four different datasets (dSprites, MNIST, and GalaxyMNIST) under affine and color transformations. The top row shows samples from the test set of each dataset. The middle row shows the prototypes generated by the SGM for each test example. The bottom row shows resampled versions of the test examples, generated by applying transformations to the corresponding prototype. The results demonstrate that the SGM is able to generate realistic and plausible samples from the data distribution, and that the prototypes capture the underlying symmetries in the data.

This figure shows the results of applying the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM) to four different datasets (dSprites, MNIST, and GalaxyMNIST) with two different transformations (affine and color). The top row shows examples from the test set; the middle row shows the prototypes generated by the SGM for each test example; and the bottom row shows the resampled examples generated by the SGM, given the corresponding prototype. The figure demonstrates that the SGM is able to learn the symmetries present in the data and generate realistic resampled examples.

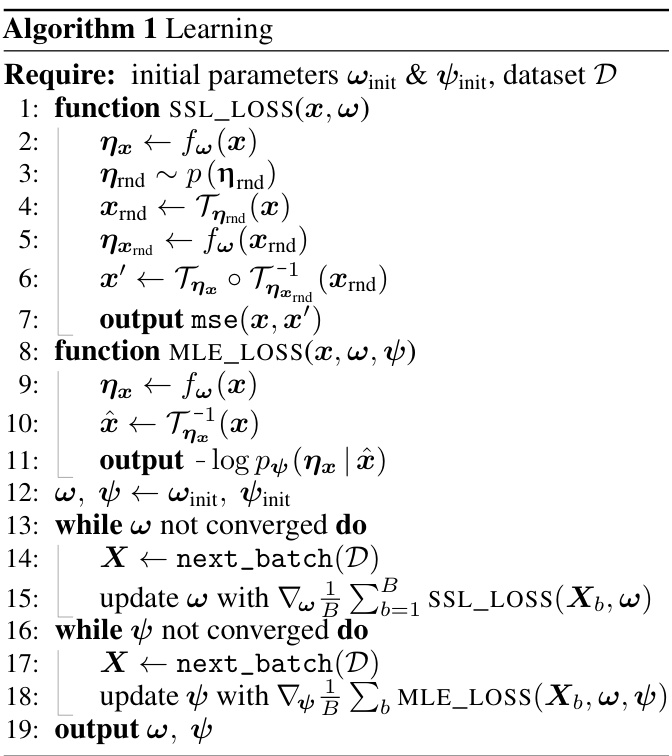

More on tables

This algorithm details the learning process for the Symmetry-aware Generative Model (SGM). It’s a two-stage process: first, self-supervised learning (SSL) is used to learn the transformation inference function (fw), which maps an observation to its prototype. Then, maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is used to learn the distribution over transformations (pψ). The algorithm iteratively updates the parameters of fw and pψ until convergence.

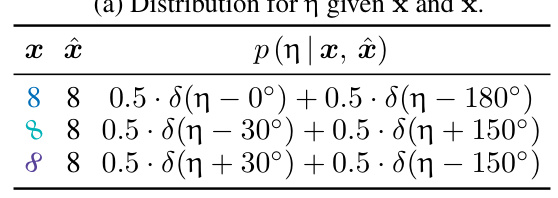

This table shows examples of simple and flexible learned distributions over angles given the true distribution. It illustrates the concept of learning a distribution over transformations that captures symmetries by comparing simple unimodal Gaussian family against a more flexible bimodal mixture-of-Gaussian family.

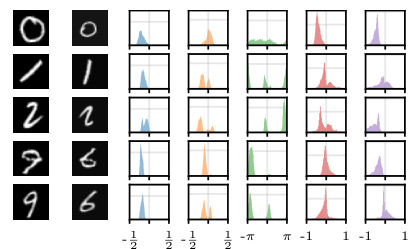

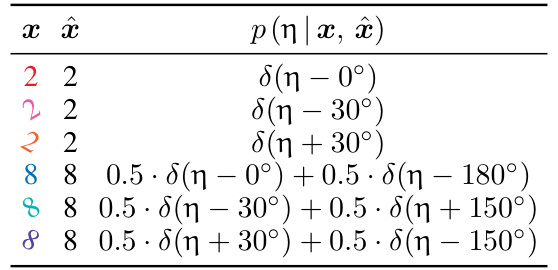

This table shows examples of learned distributions over angles, pψ(η|x), comparing cases with and without dependence on x. It illustrates the impact of considering the prototype x when modeling the distribution of transformations. The true distribution, p(η|x), is a mixture of delta functions reflecting the discrete nature of rotations in the idealized data-generating process. The table demonstrates that modeling the dependence on x leads to a more accurate and flexible representation of the distribution compared to an approach which ignores this dependency.

This table shows three scenarios of learning prototype x with different invariance levels. The first column shows the FULL invariance case where a single prototype x is used for all variations. The PARTIAL invariance case shows that the model learned to use multiple prototypes for the same digit. The NONE invariance shows that the model has learned a different prototype for each example.

This table shows the mean squared error (MSE) for x and η on fully rotated MNIST digits when using either X-space or H-space self-supervised learning (SSL) objectives. The X-space objective measures the distance in the observation space between the original and transformed images. The H-space objective uses a different transformation parameterization. The table also provides the average MSE of both methods.

This table shows the results of an experiment to determine the optimal number of samples to use when averaging the self-supervised learning (SSL) loss. The experiment used a rotation inference net with hidden layers of dimensions [2048, 1024, 512, 256, 128], trained for 2k steps using the AdamW optimizer with a cosine decay learning rate schedule, and a batch size of 256. The table shows the mean x-mse for different numbers of samples (1, 3, 5, 10, and 30). The results show that the x-mse decreases until saturating around 5 samples, indicating that using 5 samples is a good trade-off between improved performance and increased compute time.

Full paper#